Abstract

Purpose:

In low and middle-income countries, about 80% of those who need mental health services do not receive them. Reasons for this have not been systematically studied. In this qualitative study, we explored this issue in a rural community of South India among schizophrenia patients.

Materials and Methods:

Patients who had never sought psychiatric treatment despite long-standing psychotic illnesses were identified as part of a community intervention program. In-depth interviews were conducted with patients’ caregivers to understand factors preventing them seeking psychiatric treatment. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Reasons cited by family members were listed and grouped into factors based on themes. Interview process was iteratively followed till no new factor emerged. Sixteen caregivers were thus interviewed.

Results:

Content analysis brought out 75 reasons, which were further grouped under the following 15 factors [n (%)]: Lack of awareness about the illness: 15 (93.75%); lack of family support: Nine (56.25%); religious attributions: Nine (56.25%); financial constraints: Six (37.5%); family dynamics: Seven (43.75%); family's tolerance: Seven (43.75%); lack of insight: Five (31.25%); families resilience: Four (25.0%); community beliefs regarding mental illnesses: Four (25%), and others. In each patient, a complex interplay of several of these factors precluded the family from seeking psychiatric treatment.

Conclusions:

In addition to the well-known factors, many hitherto less-understood factors (e.g., families’ conflicts, dynamics, resilience and acceptance, and community support, etc.) were identified which prevented patients and their families from seeking treatment. These findings have important policy implications.

Keywords: Factors, qualitative study, rural community, schizophrenia, treatment access

INTRODUCTION

To achieve the goal of providing treatment to all those with schizophrenia, it is imperative that we understand the reasons as to why patients and families do not receive medical treatment.[1] Such a study would bring to the fore lacunae in the healthcare system, which in turn would help identify solutions through social advocacy and policy changes.

Studies that have assessed factors that influence access to mental health care have emphasized the following barriers: Stigma and discrimination[2] inherent belief that nothing could help, seeking help being a sign of weakness, denial, embarrassment to seek help, poor awareness, economic policies,[3] lack of resources, unequal distribution of resources, insufficient facilities, poor allocation of funds,[4] lack of availability and accessibility of treatment,[5] lower socio-economic status, low education, poorly developed services and beliefs in supernatural powers.[6] A study from India has highlighted the limited access, inadequate knowledge, lack of family support, and continued dependence by the family on the service provider.[7]

Most Indian studies have used checklists[8,9,10] to assess reasons for not accessing treatment. Uses of these (and interviewer directed questionnaires) have limitations: They may fail to capture many patient/family-related factors. Further, these checklists/interviews may not be standardized to our populations. Qualitative studies are ideally suited to inform these issues.

As part of developing a comprehensive tool to assess this problem in rural communities, we conducted qualitative interviews to explore factors that preclude patients and their families’ access to psychiatric treatment. This paper describes the results of this interview.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample

The sample came from a community intervention program titled ‘Treating Untreated Psychosis in Rural Community: Variation in the Experience of Care (TURUVECARE).’ entailing identification treatment and follow-up of all schizophrenia patients in Turuvekere, a south Indian taluk (an administrative block). The taluk has a population of 174,297 according to census 2001.[11]

Identification of patients

We trained 12 primary care doctors and 361 health workers (from all cadres) in applying a simple tool titled ‘Symptoms in others’.[12] This is a validated instrument of identifying psychiatric disorders in the community, which can be used by grass-root level health staff. They were asked to refer all such patients to the study team. In addition, the research social workers visited each village with the purpose of case finding. They interviewed key informants in the community. After identifying patients, enquiries were made about similar persons that they may have come across. After complete description of the study to the participants/family members, written informed consent was obtained. The data was collected between December 2009 and April 2010.

Assessments

Recruitment and diagnosis

Diagnosis was made by psychiatrists using the Mini - International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).[13] Their psychopathology and disability were assessed using the positive and negative syndrome scale[14] and the Indian Disability Evaluation and Assessment Scale (IDEAS),[15] respectively. Consecutive patients with history of having never received psychiatric treatment were recruited till we achieved ‘saturation’ of factors (see below; n = 16). We recruited one patient on any given day; if two patients were identified on the same day, then we assessed only the first patient, as interviewing two patients and their families posed practical challenges in terms of time. ‘Psychiatric treatment’ was defined as evaluation and treatment by doctors trained in modern allopathic treatment.

A total of 716 individuals were referred to or identified by the study team. Among these, 137 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; 27 suspected patients were not assessed because patients were too symptomatic to provide valid consent and the research team could not trace their family members. Among the 137, 40 (29.2%) were never treated, 63 (46%) were not on treatment presently but had received psychiatric treatment at least once in the past and 34 (24.8%) were on continuous treatment.

Interviews

We interviewed only family members as severe symptomatology of patients made their interviews impossible. “Family members” were defined as caregivers above 18 years, living under the same roof as that of the patient at least during the past year and being responsible for the patient's overall care. Interviews were conducted in the following four phases.

Phase I (10-15 minutes)

In this phase, they were asked about the following: Possible reasons for not providing psychiatric treatment for their ill relative; how they were managing patient's altered behavior. This phase was conducted using open-ended questions and family members were encouraged to provide as much details as possible using facilitating questions like, “what else?”, “then what?”, “is there anything else?” etc.

Phase II

In this phase, semi-directive questions were used to obtain further elaboration on each of the reasons listed above. Examples and illustrations were provided. Discrepancies and contradictions were reflected back.

Phase III

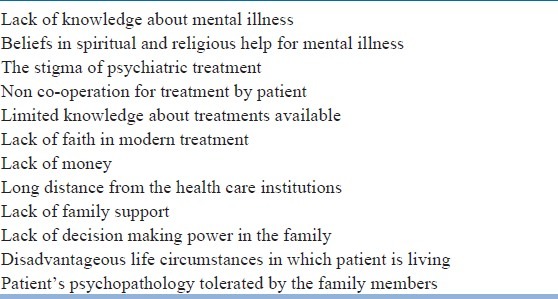

In this phase, a more directive questioning was conducted using a list of reasons obtained from the existing literature [Table 1] focusing on such reasons not covered so far. Phase-II techniques were used to get elaboration and clarification.

Table 1.

List of factors enlisted from review of literature on barriers to access psychiatric care in patients with severe mental disorders (used in phase III of interview)

Phase IV

In this phase, the family members were asked to cite the most and the least important reason (from among the reasons they had already listed), which prevented them from seeing psychiatric treatment.

Data management and analysis

All interviews were transcribed. Color coding was done to synthesize factors. Representative quotes were selected for each of these factors. The quotes and the color codes were reviewed by authors independently to reduce biases.

Saturation of factors

Data collection and interpretation took place iteratively. Whenever a new reason emerged, it was added to the existing list (that was used in Phase-III). From the 13th patient onwards, no new reason emerged. Three more families were interviewed to ensure that there was no additional reason. Thus, families of 16 patients were interviewed.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS). Participants were included only after the provision of the written informed consent.

RESULTS

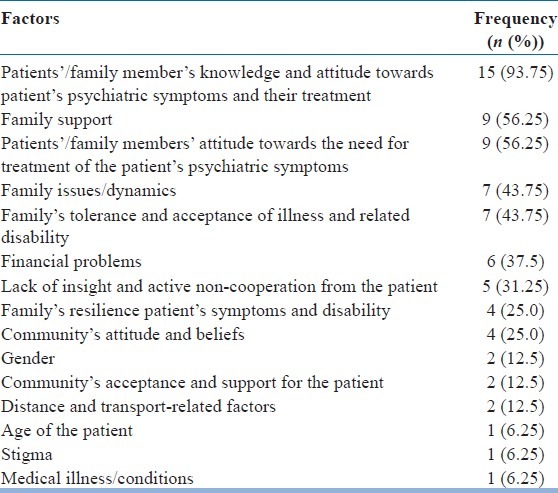

Mean age of the patients was 40.06 (SD = 1.45) years. Out of the 16 patients, nine (56.2%) were males, 15 (93.8%) were Hindus, and five (31.2%) had high school education. Mean duration of illness was 61.75 (SD = 49.03) months. Mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score was 93.62 (SD = 19.41) and mean disability score was 11.19 (SD = 3.41) on Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEAs). Sixteen families came up with 75 reasons (average = 4.69) that prevented them from seeking psychiatric treatment. Table 2 shows the details.

Table 2.

Frequency of each factor that prevented patients/families from seeking psychiatric treatment

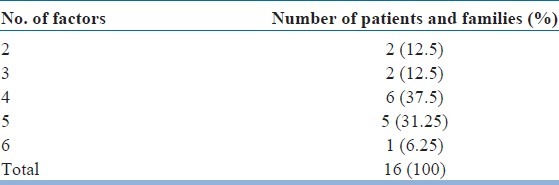

We listed the factors (along with their frequency) that precluded families from seeking psychiatric treatment in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of factors (and their frequency) that precluded families from accessing psychiatric treatment

Patients’/family member's knowledge and attitude towards patient's psychiatric symptoms and their treatment [15 (93.75%)]

Most Families had never heard or seen anyone with a similar problem. They had no idea about its causes/treatment. They had attributed the symptoms to patients’ personality.

E.g.: Husband told that “We did not regard her behavior as mental illness; I didn’t know that there is treatment for these behaviors and we felt that these symptoms were common or normal”.

Family support [Nine (56.25%)]

Complex family dynamics had created lack of family support for some patients. Certain family members did not want patients to become better, as by doing so, they would have had to share the ancestral property; in some cases, family members ignored patients’ symptoms and treatment because other issues assumed greater priority (marriage) than the treatment of the patient.

E.g.: Son told that “If anybody tried to help us in taking my mother to the hospital, my uncle would threaten them, as she would recover and claim the land”.

Patients’/family members’ attitude towards the need for treatment of the patient's psychiatric symptoms [Nine (56.25%)]

Patients/family members may have never felt that the patient's symptoms were unusual, and hence, would not have sought any form of treatment including magico-religious/AYUSH (Indian System of Medicine) treatments.

E.g.: Patient's daughter-in-law told that “My family members firmly believed that the illness was due to God's curse or a spell of black magic and he quarreled with someone in the village; then he became fearful and suspicious towards others”.

Family issues/dynamics [Seven (43.75%)]

In some cases, complex dynamic issues were present in the family. These included direct threats related to enmity, alternative priorities, sense of revenge, and court cases for divorce, etc.

E.g., Daughter told that “After marriage, her brothers did not show any concern about their sister and they neglected her treatment”.

Family's tolerance and acceptance of illness and related disability [Seven (43.75%)]

Many family members did not perceive significant disruption because patients had less florid symptoms. Consequently, productivity also was partially preserved.

E.g., Daughter told that “My family members thought that illness characteristics were inherited from ancestors and that she would recover spontaneously in the near future or due course and she was productive and not much disturbing the family functioning”.

Financial problems [Six (37.5%)]

Reasons for financial difficulties varied: Family members (e.g. parents) being too old and unable to earn; being retired and sustaining on meager pension etc.

E.g.: Father told that “We were unable to travel far and obtain treatment due to financial constraints and there was no money to spare on treatment”.

Lack of insight and active non-cooperation from the patient [Five (31.25%)]

Some patients actively opposed any treatment attempts of any form. They would become aggressive or would run away. In some instances, the patient would do something to embarrass the family members or even hurt him/herself when attempts to get him/her to treatment were initiated.

E.g.: Mother told that “Her daughter was unwilling to travel to hospital; when she was called, she refused stating that she was alright and needed no treatment.”

Family's resilience patient's symptoms and disability [Four (25.0%)]

Some of the primary care givers reported that they were able to somehow carry on with their family functioning. Though patient's behavior disturbed their family life, they were able to manage or compensate.

E.g., Father told that “Her behavior was disturbing the daily family life but we were able to manage or compensate and symptoms of the illness did not affect family functioning”.

Community's attitude and beliefs [Four (25%)]

Some family members were influenced by the words of other villagers and neighbors that the illness is incurable.

E.g., Brother told about his sister that “Villagers and neighbors were of the opinion that the illness is incurable and the neighbors were saying that she was timid and “weak-minded”, and hence, we did not think that her behavior was an illness”.

Gender [Two (12.5%)]

Two issues were identified. In one case, the family was not serious about treatment because the patient was a female and in another, opinion of the female members was ignored by the dominant male members.

E.g., Mother of a patient said “I wanted to take her to hospital but the decision was not agreed upon by her father and I became helpless”.

Community's acceptance and support for the patient [Two (12.5%)]

In two instances, villagers had shown caring attitude towards the patients and this had reduced the felt need of the family for getting the patient treated.

E.g.: Daughter-in-law reported that “Villagers have been caring towards him; whenever he wandered away from home, the villagers would inform us or bring him home and when patient misbehaved, villagers would be tolerant or accommodative”.

Distance and transport-related factors [Two (6.25%)]

Having to travel long distances and difficulty in traveling to a psychiatrist may be causes for not seeking treatment.

E.g.: Father reported that “We were unable to go for treatment due to difficulties involved in travelling-the hospital is far and we don’t have good roads”.

Age of the patient [One (6.25%)]

The family may be tolerant to symptoms and disability in patients who have crossed middle age. Alternatively, if the patient is teenager/young adult, the families may get concerned that treatment may have adverse influence on their development.

E.g., Son told that “My father becomes aged and unable to travel and he has gradually last the important family decisions.”

Stigma [One (6.25%)]

Stigma of having a mental illness or having a mentally ill person in the family may have a role in preventing the patient/family seeking psychiatric treatment.

E.g.: Brother told that “If we visit the Govt hospital for treatment, our prestige will decrease in the village and the people will came to know that my brother has the illness”.

Medical illness/conditions [One (6.25%)]

Patient's comorbid medical condition (deaf-mutism) prevented family members in understanding the manifestations of psychiatric disorder.

E.g.: Sister told that “My sister was deaf and mute since birth; we had difficulty in understanding that her altered behavior was due to mental disorder”.

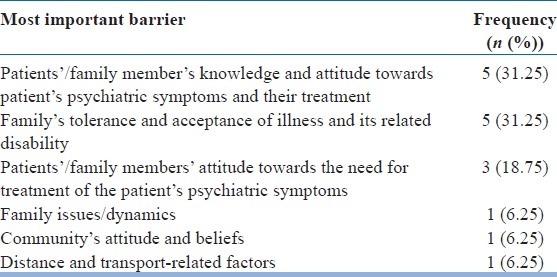

Each of the families had more than one factor. Moreover, a complex interplay of these factors precluded them from accessing treatment. Table 4 shows the frequencies of the most important factors.

Table 4.

Frequencies of most important factor that prevented each family from seeking psychiatric treatment

DISCUSSION

In this study, we used a qualitative approach to understand factors which prevented schizophrenia patients from accessing psychiatric treatment in a rural community. Patients were quite severely ill and had remained untreated for several months (mean 61.75 SD = 49.026 months).

A diverse set of factors that prevented access to treatment were identified. On an average, each patient and family had about four to five factors. Thus, a complex and dynamic interplay of several factors rather than any single factor determined non-access to psychiatric care.

In addition to the well-known factors, we identified many hitherto less-understood factors such as gender related issues, families' resilience, community's acceptance and support for the patient, family conflicts, and dynamic issues. This was possible because of the qualitative narrative-based approach. From the narratives of many families, it was evident that these newly identified factors played a crucial role in preventing them from accessing treatment. Thus, in some families, despite awareness and comfortable financial situation, patients remained untreated.

In contrast, many factors such as belief that nothing could help, seeking help being a sign of weakness, denial of problems, embarrassment to seek help,[4] etc., did not emerge as factors in our study. Evidently, most of these are patient's perspectives; as we could not interview patients, we were unable to obtain their perspective in our study.

Another interesting finding was that, some factors that prevented patients and families from seeking treatment were actually positive ones (albeit from a different perspective). For example, in some cases, the community had a fairly positive attitude towards patients-they had accepted the patient's altered behavior and even actively supported their lives. This had reduced the distress to the patients’ families and the community thereby reducing the felt need for medical treatment. Efforts to bring such patients under the umbrella of treatment should concentrate on treating patients while carefully preserving and harnessing these positive factors.

This study has many important lessons from a public health perspective

The commonest reason for not accessing treatment was lack of awareness of a biomedical disorder and the beneficial effects of psychiatric treatment. This underscores the need to enhance community awareness regarding severe mental disorders. These include intensive information, education and communication (IEC) activities and inclusion of psychiatric issues in school curricula.

Though severe mental disorders could be identified easily even by the non-medical healthcare workers, we noticed that the personnel were woefully ignorant about the nature of psychiatric disorders. With the successful implementation of the District Mental Health Program (DMHP, as part of the NMHP), which includes sensitization of healthcare personnel, there is hope that this barrier could be overcome.

Logistic factors like distance, transport facilities, and financial problems were other important factors that prevented access to treatment.

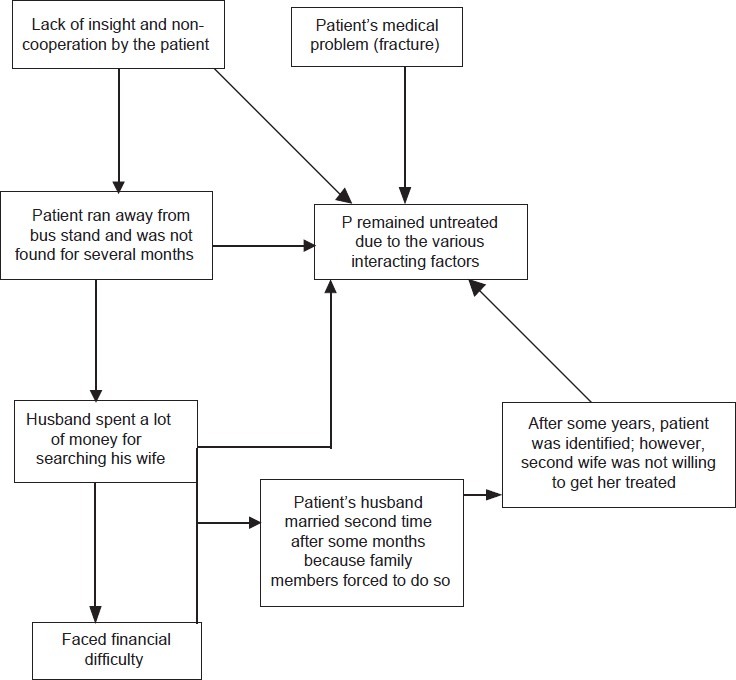

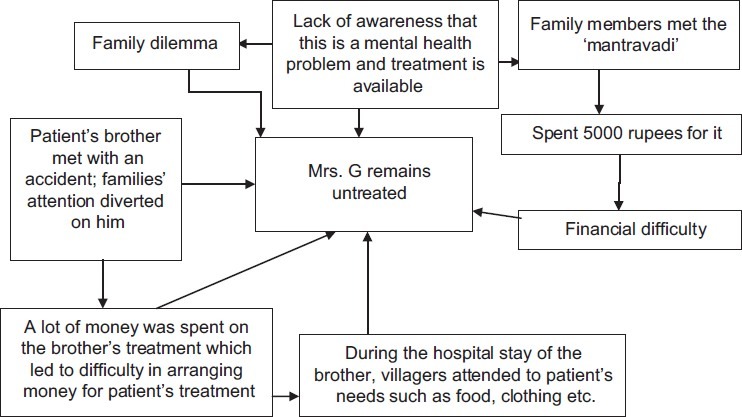

Multiple factors preventing each patient's access to treatment should be considered while planning programs that attempt to bring all patients with psychoses under treatment. For instance, making treatment available locally may address the issue about distance and transport factors, but would do little to overcome the reasons posed by lack of awareness, family dynamics, family support, etc., This may result in many patients remaining untreated even if treatment is made available in primary health centers as is envisaged by the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) [Figures 1 and 2 has explained].

Figure 1.

Shows the complex interplay of reasons/factors that led to non-treatment of Mrs. P

Figure 2.

Complex interplay of reasons for Mrs. G to remain untreated

This has been highlighted in earlier studies too, which showed that several patients would not receive any treatment for many years even in and around large towns, despite easy availability of health services.[9] In addition to the adequate allocation of finances, many other issues such as constant monitoring of the service activities, proper on-going training of the service providers, continued Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) activities, adequate follow-up services involving grass-root level workers in such programs, etc., are required for successful implementation of public health programs. Hopefully, the upcoming versions of the NMHP, these issues would be addressed.

At this stage, we wish to highlight a few strengths of our study

Proactive steps were taken to include community dwelling patients who had long durations of untreated illnesses. Any hospital-based study would have missed such patients. Our study thus is a unique one. Because of the qualitative open approach, we were able to identify a number of novel factors.

The results of our study should be interpreted with certain caveats

We were not able to interview patients who had no families. As they too have rights to optimal treatment, it is important to understand factors that prevent them from accessing treatment. Because of the ethical issues related to consent, we were unable to recruit them. However, it should be noted that the social worker had sensitized the gram panchayat members regarding their duties in helping such patients get humane treatment as per the directive principle of the state; article 243G in Constitution of India.[16]

CONCLUSIONS

This qualitative study to understand factors that prevented schizophrenia patients and their families living in a rural community from seeking psychiatric treatment has highlighted a number of issues. A complex dynamic interplay of multiple factors precludes such patients from accessing psychiatric treatment. The results have significant public health importance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors acknowledge the help of Dr. Choudhuri Nagesh and Dr. Jai Prakash, for helping us identify persons with schizophrenia in the community.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was conducted with the help of research grants from the Government of Karnataka and American Psychiatric Association as part of ‘Young Minds in Psychiatry’ award (year 2009) to Drs Jagadisha Thirthalli and Naveen Kumar C respectively

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kare M, Thirthalli J, Varghese, Reddy KS, Jagannath A, Gangadhar BN, et al. Reducing the delay in treatment of psychosis. Where do we intervene? A study of first. contact patients in NIMHANS. Best Poster Award at the Richmond Fellowship Asia-Pacific Conference, NIMHANS; Bangalore, India. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, Collins PY. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:511–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michelle A, Moskos, Olson L, Sarah R, Halbern, Gray D. Youth suicide study: Barriers to mental health treatment for adolescents. New York: Guilford Publications; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David M. Removing barriers to care among persons with psychiatric symptoms: A well-functioning managed care approach can provide an acceptable level of care and cost. J Health Aff. 2002;21:137–47. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharra H. Barriers to treatment for individuals with schizophrenia and manic depression. vol. 5. Paradigm Magazine; 2001. p. 2.2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohaeri JU, Fido AA. The opinion of caregivers on aspects of schizophrenia and major affective disorders in a Nigerian setting. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001;36:493–9. doi: 10.1007/s001270170014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thara R, Padmavati R, Aynkran JR, John S. Community mental health in India: A rethink. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasa Murthy R, Kishore Kumar KV, Chisholm D, Thomas T, Sekar K, Chandrashekari CR. Community outreach for untreated schizophrenia in rural India: A follow-up study of symptoms, disability, family burden and costs. Psychol Med. 2005;35:341–51. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naik AN, Parthasarathy R, Isaac MK. Brief report: Families of rural mentally ill and treatment adherence in district mental health programme. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1996;42:68–72. doi: 10.1177/002076409604200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padmavathi R, Rajkumar S, Srinivasan TN. Schizophrenic patients who were never treated: A study in an Indian urban community. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1113–7. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Last accessed date on 20th January 2013]. Available from: http://www.censusindia.net/

- 12.Kapur RL. Factors affecting the reporting of mental disorder in others. J Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1975;10:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bul. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehabilitation Committee of Indian Psychiatric Society. Indian Disability Evaluation and Assessment Scale: Assessment scale: A scale for measuring and quantifying disability in mental disorders; Indian Psychiatric Society, Kolkata. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajashekar HM. Indian Government and Politics. Karnataka: Kiran Publications; 2009. pp. 289–90. [Google Scholar]