Abstract

Background

Peer education for HIV prevention has been widely implemented in developing countries, yet the effectiveness of this intervention has not been systematically evaluated.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of peer education interventions in developing countries published between January 1990 and November 2006. Standardized methods of searching and data abstraction were utilized. Merged effect sizes were calculated using random effects models.

Results

Thirty studies were identified. In meta-analysis, peer education interventions were significantly associated with increased HIV knowledge (OR:2.28; 95% CI:1.88, 2.75), reduced equipment sharing among injection drug users (OR:0.37; 95% CI:0.20, 0.67), and increased condom use (OR:1.92; 95% CI:1.59, 2.33). Peer education programs had a non-significant effect on STI infection (OR: 1.22; 95% CI:0.88, 1.71).

Conclusions

Meta-analysis indicates that peer education programs in developing countries are moderately effective at improving behavioral outcomes, but show no significant impact on biological outcomes. Further research is needed to determine factors that maximize the likelihood of program success.

Keywords: HIV prevention, peer education, developing countries, systematic review, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Peer education interventions are a frequently utilized strategy for preventing HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide. Such interventions select individuals who share demographic characteristics (e.g. age or gender) or risk behaviors with a target group (e.g. commercial sex work or intravenous drug use) and train them to increase awareness, impart knowledge and encourage behavior change among members of that same group. Peer education can be delivered formally in highly structured settings (such as classrooms) or informally during the course of everyday interactions.

Peer education programs are based on the rationale that peers have a strong influence on individual behavior (Population Council, 2000). As members of the target group, peer educators are assumed to have a level of trust and comfort with their peers that allows for more open discussions of sensitive topics (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002). Similarly, peer educators are thought to have good access to hidden populations that may have limited interaction with more traditional health programs (Sergeyev et al., 1999). Peer education programs may be empowering to both the educator (Milburn, 1995; Strange, Forrest & Oakley, 2002) and to the target group by creating a sense of solidarity and collective action (Population Council, 2000; Campbell & Mzaidume, 2001). Interventions using peers can also be more cost-effective than interventions that rely on highly trained professional staff (Hutton, Wyss & N’Diekhor, 2003; Pinkerton, Holtgrave, DiFranceisco, Stevenson & Kelly, 1998; Tao & Remafedi, 1998), although the costs of these interventions are often underestimated (Population Council, 2000).

Peer education interventions have been used with a number of target populations in developing countries, including youth (Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Brieger, Delano, Lane, Oladepo & Oyediran, 2001; Merati, Ekstrand, Hudes, Suarmiartha & Mandel, 1997), commercial sex workers (Ford, Wirawan, Suastina, Reed & Muliawan, 2000; Basu et al., 2003; Morisky, Stein & Chaio, 2006), and injection drug users (Broadhead et al., 2006; Hammett et al., 2006; Li, Luo & Yang, 2001). Yet to date, there has been no systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of these interventions in changing HIV related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in these settings. To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effect of peer education interventions on HIV knowledge, injection drug equipment sharing, condom use, and STI infection in developing country settings.

METHODS

This review is part of a larger series of systematic reviews of HIV behavioral interventions in developing countries conducted jointly by the Medical University of South Carolina and the World Health Organization. Other interventions that have been systematically reviewed under this project include mass media (Bertrand, O'Reilly, Denison, Anhang & Sweat, 2006), psychosocial support (Sweat, O'Reilly, Kennedy & Medley, 2007), treatment as prevention (Kennedy, O'Reilly, Medley, & Sweat, 2007), and voluntary counseling and testing (Denison, O’Reilly, Schmid, Kennedy, & Sweat, 2008). We use standardized methods across all reviews. In this review, we sought to answer the question, what is the impact of peer education on HIV/AIDS-related outcomes? We utilized methods consistent with the “Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology” (MOOSE) guidelines (Stroup et al., 2007).

Definition of peer education

We defined peer education interventions as the sharing of HIV/AIDS information in small groups or one-to-one by a peer matched, either demographically or through risk behavior, to the target population. This definition distinguishes peer education from mass media programs that may be hosted by a peer, but where no interpersonal interaction occurs and information flows in only one direction.

Inclusion criteria

Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (1) a peer education intervention meeting our definition was implemented; (2) the intervention was conducted in a developing country, defined as the World Bank categories of low-income, lower-middle income, or upper-middle income economies (World Bank, 2008); (3) an evaluation design was employed that compared post-intervention outcomes using either a pre/post or multi-arm study design (including post-only exposure analysis); (4) behavioral, psychological, social, care, or biological outcome(s) related to HIV prevention were presented; and (5) the article was published in a peer-reviewed journal from January 1990 through November 2006. We restricted the review to developing country settings for three reasons: (1) the epidemic is generally more severe in these settings; (2) the factors affecting the success or failure of these interventions may differ based on resource availability; and (3) there is a dearth of information on the effectiveness of these interventions at changing HIV-related attitudes and behaviors in these settings. No language restrictions were used; English translations were conducted when necessary. If two articles presented data for the same project and target population, the article with the longest follow-up was retained for analysis.

Search strategy

We conducted searches using five electronic databases: the U.S. National Library of Medicine's (NLM) Gateway system, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, EMBASE, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). A complete list of search terms can be found in the Appendix. To identify articles not obtained from electronic database searching, we hand-searched the table of contents of four journals: AIDS, AIDS and Behavior, AIDS Care, and AIDS Education and Prevention. We also examined the reference lists of included articles to further identify articles we may have missed. This process was iterated until no new articles were found.

Study selection

Initial inclusion/exclusion of studies was conducted by a member of the study staff, who excluded clearly non-relevant citations based on titles and abstracts. The remaining citations were then screened by two senior study staff according to the inclusion criteria above. The results of these two independent screenings were merged for comparison, and discrepancies were discussed to establish consensus. Final inclusion/exclusion of studies was based on a thorough reading of the full-text article.

Data extraction

Each article meeting the inclusion criteria underwent data extraction by two independent reviewers. Data were entered into a systematic coding form that included detailed questions on intervention, study design, methods, and outcomes. The two completed coding forms were compared and discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer.

Rigor score

The rigor of the study design of included articles was assessed using an eight-point scale. This scale was developed for the larger series of systematic reviews and is additive, with one point awarded for each of the following items: (1) prospective cohort; (2) control or comparison group; (3) pre/post intervention data; (4) random assignment of participants to the intervention; (5) random selection of subjects for assessment; (6) follow-up rate of 80% or more; (7) comparison groups equivalent on socio-demographic measures; and (8) comparison groups equivalent at baseline on outcome measures.

Meta-analysis

We converted effect size estimates to the common metric of an odds ratio since all studies compared two groups and reported dichotomous outcomes. We utilized standard meta-analytic methods to derive standardized effect size estimates (Cooper & Hedges, 1994) and used the software package Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V.2.2 to conduct statistical analyses. For each outcome, we entered the odds ratio directly into the program or calculated the odds ratio from the percentages reported in the article. When other statistics were presented such as chi-square or mean differences, we converted them to the standardized mean difference, “d”, and then converted “d” to an odds ratio using readily available and widely accepted formulas (Cooper & Hedges, 1994). Odds ratios were pooled using random effects models. We attempted to contact authors when published articles provided insufficient information to conduct these calculations.

Selection of study endpoints

Meta-analysis was conducted on four outcomes that were reported across multiple studies: HIV knowledge, injection drug equipment sharing, condom use, and STI infection. HIV knowledge included variables measuring correct and incorrect information regarding modes of HIV transmission and prevention. Intravenous drug equipment sharing included reported episodes of sharing needles/syringes, rinse water and/or cookers. Condom use was the dichotomous proportion of respondents who either (a) did or did not use condoms, or (b) did or did not have unprotected sex. STI measures included STI incidence, current prevalence, and lifetime prevalence, and were measured by self-report, chart review, and clinical diagnosis. All STI measures were dichotomous proportions of respondents who reported or who were diagnosed with an STI using these measures.

For all outcomes, our selection of the measure to be included in meta-analysis prioritized the comparison with the longest follow-up. When articles presented multiple measures of the same outcome (e.g. condom use at last sex and ever condom use), we calculated an average effect size across these various measures within each study. The specific measures contributed by each study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study descriptions

| Study | Setting | Population Characteristics |

Intervention Description | Study Design | Outcomes Used in Meta-Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth and adolescents | |||||

| Agha et al., 2004 | Zambia (Central, Copperbelt, and Lusaka provinces) | School based adolescents Gender: 56% male, 44% female Age Range: 14–23 years |

Intervention arm: Peer educators facilitated a 1-hour and 45 minute long session that included an open discussion about sexual health; drama skits; and the distribution of leaflets about STIs. Comparison arm: Students received a 1-hour long peer edcuation session about water purification. |

Group randomized trial with comparison arm. Assessments at baseline (N=481), 2-months (N=416), and 8-months (N=416) post-intervention. Randomized selection of both schools and participants for intervention. | HIV knowledge, condom use |

| Asamoah, 1999 | Ghana (Urban Cape Coast municipality) | In-school adolescents Gender: 50% female; 50% male Mean age: 13.68 years |

Peer-led discussion: 50 minute discussion on AIDS led by peer educators Adult-led lecture: 50 minute didactic lecture about AIDS Comparison group: 50 minute spelling and word games |

Individual randomized trial with three study arms. Assessments at baseline (N=180) and 3-weeks (N, not reported). Individual unit of analysis. Randomized selection of individuals for intervention. | HIV knowledge |

| Ergene et al., 2005 | Turkey (Ankara) | Undergraduate students at two metropolitan state universities. Gender: 40.6% males; 59.4% females Average age: 20 years |

Peer group: Peer educators organized seminars and responded to questions. Average session lasted 25–40 minutes. Lecture: A medical doctor gave a 1-hr. lecture on HIV/AIDS prevention followed by a 15-minute question and answer session. |

A post-test only quasi-experimental design comparing a peer-led intervention (N=204) to a single session lecture (N=74) and wait-list control group (N=109). Random selection of participants into study arms. | HIV knowledge |

| Gao et al., 2002 | China (Beijing, Shanghai) | Students Age and gender distribution not reported |

Intervention: Senior medical students were trained to teach their junior peers about HIV/AIDS, STDs and safer sex. Control: Received no intervention. |

Group randomized control trial. Assessments at baseline (N=NR) and 6-month follow-up (N=NR). Random assignment of school classes to intervention arms. | HIV knowledge |

| Kinsler et al., 2004 | Belize (Belize City) | School based adolescents Gender: 63% female 37% male Mean Age: 15.3 years |

Intervention: Peer educators delivered seven weekly 2-hour classroom based education sessions. Comparison: Students received HIV/AIDS educational handbooks. | Non-randomized group trial comparing an intervention group to a comparison group. Assessments at baseline (N=150) and 3-months (N=150) follow-up. Individual unit of analysis. Non-random selection of schools and participants. | HIV knowledge, Condom use |

| Merati et al., 1997 | Indonesia (Bali) | Youth aged 16–25 years attending youth groups in banjars in Bali Age and gender distribution not reported |

Youth attended a 7 hour peer-led educational training program on HIV/AIDS prevention. | Before-after study design with no comparison group. Assessments at baseline (N=100) and 6-month follow-up (N=97). Non-random selection of participants. |

HIV knowledge |

| Ozcebe et al., 2004 | Turkey (Ankara) | Target pop: High school students Gender: 45.9% Male; 54.1% Female Median age: 16 years |

Peer educators shared knowledge with classmates through designing posters for the school billboard, giving lectures in the classroom, and holding group discussions. |

Before-after study design with no comparison group. Assessments at baseline (N=148) and 6-months (N=148). Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge |

| Speizer et al., 2001 | Cameroon (Nkongsamba: intervention; Mbalmayo: control) |

Adolescents both in-school and out-of-school Gender: Approximately 50% female and 50% male Age Range: 12–25 years |

Peer educators organized 353 discussion-group seminars with about 12,000 young people and distributed the project’s promotional materials, including calendars, comic strips, and posters, to schools and elsewhere in the community. They also referred youth to health or social centers for services. | A pre- and post-test serial cross sectional design with two arms (intervention and control). Assessments at baseline (N=802) and 17-months (N=818). Random selection of participants for assessment. | Condom use |

| Female commercial sex workers | |||||

| Asamoah-Adu et al., 1994 | Ghana (Accra) | Female commercial sex workers Mean Age: 38 years |

Trained peer educators provided information about AIDS and distributed free condoms and spermicidal foaming tablets. Outreach workers organized group meetings to augment peer education efforts. | Time series design with assessments at baseline (N=72), 6-months (N=44), and 3-years (N=27). Individual unit of analysis. Non-random selection of participants. | Condom use |

| Ford et al., 2000 | Indonesia (Bali) | Female sex workers Age range: 15–42 years, Mean age 27.6 |

Peer educators acted as a resource for a cluster of other sex workers. Intervention group: peer educators remained in cluster at least 1-month Comparison group: peer educators remained less than one month. Both groups also received group education from health worker every two months. |

Pre-post serial cross sectional design comparing intervention and comparison groups. Assessments s at baseline (N=189) and at a 5–6 months follow-up (N=187). Individual unit of analysis. Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge, STI infection, Condom use |

| Morisky et al., 2006 | Philippines (Legaspi, Cagayan de Oro, Cebu, Ilo-Ilo) | Female commercial sex workers Mean Age: 22.5 years (range 15–41 years) |

Peer educators delivered HIV/STI prevention messages and sexual negotiation skills. Managers were also trained to deliver health messages to their employees and to have a 100% oral and written condom-use policy. | Group randomized serial cross sectional design comparing three interventions (peer-only intervention; manager-only intervention; combined peer and manager intervention) and a control group. Assessments at baseline (N=897) and 24-months before and 24-months after an intervention. Random selection of participants | HIV knowledge, STI infection, Condom use |

| Ngugi et al., 1996 (Kenya) | Kenya (Machakos, Nakuru, Thika) | Female sex workers Mean Age: 27.9 years |

Each peer educator was responsible for a group of 20 peers and served as a resource, an HIV/AIDS educator and a promoter and distributor of condoms. | Before-after study design with no comparison group. Assessments at baseline (N=299) and 1-year (N=299). Non-random sampling of participants. | Condom use |

|

Ngugi et al., 1996 (Zimbabwe) |

Zimbabwe (Bulawayo) | Female commercial sex workers Age Distribution Not Reported |

Peer educators held two or more weekly community meetings in their social networks and distributed male condoms. | Serial cross sectional design with no control group. Assessments at baseline (N=not reported) and 1-year follow-up (N=705). Non-random selection of participants. | Condom use |

| Thomsen et al., 2006 | Kenya (Mombasa District) | Female commercial sex workers Mean Age: 29 years |

Peer educators educated women about female condoms and distributed free female condoms for the 8-months of the intervention (20 condoms/month/participant). | Time series study design with no comparison arm. Assessments at baseline (N=210), 4-months (N=196), and 12-months (N=195). Mixture of random and non-random sampling. | Condom use |

| Van Griensven et al., 1998 | Thailand (Sungai Kolok and Betong) |

Female commercial sex workers Mean Age: Intervention: 25 years Control: 24 years |

“Walkman” and cassette tapes with music and informative messages were circulated among women. Leaflets, comic books, and free condoms were distributed at STD clinics. Peer educators were established at each of the sex establishments. Leaflets with two condoms were placed in hotel rooms. | Serial cross sectional design comparing an intervention and control group. Assessments at baseline (N=751) and 6-months (N=739). Non-random selection of participants. |

Condom use |

| Welsh et al, 2001 | Dominican Republic (La Romana, San Pedro de Macoris, Guaymate) | Female commercial sex workers (FSWs) Age range: 20–29 years |

Peer educators emphasized risk-reduction strategies, including the regular and consistent use of condoms. The intervention was only implemented in La Romana, but due to proximity of the other two cities, it was assumed that the peer educators also diffused information to the other cities. | Serial cross sectional design with no control arm. Assessments at baseline (N=196), 4-months (N=201), and 8-months (N=200). Non-random selection of participants. | Condom use |

| Injection drug users | |||||

| Broadhead et al., 2004 | Russia (Bragino and Rybinsk) | Injection drug users Gender: 73.3% males; 26.7% females Age distribution varied by city |

Peer educators deliver an initial HIV education and refer participants to study clinic. At study clinic, a health educator delivers an enhanced education session. At 6-months, participants taught a second education module. All participants given harm reduction kits to distribute to peers. Free HIV counseling and testing and needle exchange offered on-site. | Before/after study design comparing two types of peer-driven interventions (PDI). In the Simplified PDI, peer educators were paid based on how well participants perform on HIV knowledge test. In the Standard-PDI, peer educators were paid based on number of recruits who come to clinic. Assessments at baseline (N=857) and 6-months (N=629). Individual unit of analysis. Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge, Condom use, Equipment sharing |

| Hammett et al., 2006 | China (Ning Ming), Vietnam (Lang Son) |

Injection drug users Gender: China: 90% male; 10% female; Vietnam: 99% male; 1% female Age: Percent between ages of 21–30 years: 68% in China, 72% in Vietnam. |

Trained peer educators provide information on reducing drug use-related and sexual HIV risks, orally and through distribution of brochures. They distribute new needles/syringes, ampoules of sterile water for injection, and condoms. Peer educators also collect and dispose of used needles/syringes. | Serial cross sectional design. Assessments at baseline (N=633), 6-months (N=671), 12-months (N=630), 18-months (N=634), and 24-months (N=542) follow-ups. In China, non-random selection of participants. In Vietnam, a mixture of probability and non-probability sampling was used to select participants. | Equipment sharing |

| Li et. al., 2001 | China (Kunming) | Injection drug users attending drug rehabilitation centers Age and gender distribution not reported |

Peer educators designed and produced harm reduction materials with program workers. They returned to their dormitories and used these materials to educate their peers. | Before-after serial cross-sectional study design. Assessments at baseline (N=306) and 2-years post-intervention (N=418). Random selection of participants. | Condom use, Equipment sharing |

| Sergeyev et al., 1999 | Russia (Yaroslavl) | Injection drug users Gender: 28.3% female and 71.7% male Age: 34.8% under 20 years; 60.2% 20–29; 4.3% 30–39; 0.7% 40–49 |

Active drug users were given modest monetary incentives for educating their peers about risk reduction techniques, recruiting them to a storefront for further education and HIV/STD testing, and distributing HIV prevention materials. Needle exchange and free condom distribution were also provided. | Time series study with no comparison arm. Assessments at baseline (N=484), first follow-up (N=86), and second follow-up (N=35). Times for follow-ups not reported. Non-random selection of participants. | Equipment sharing |

| Truck drivers/transport workers | |||||

| Leonard et al., 2000 (41) | Senegal (Kaolack) | Male transport workers from two transportation parks Mean Age: 32.5 years (range 13–70 years) |

Peer educators answered basic questions about HIV and STDs and distributed condoms and print materials to their peers. They also referred men with symptoms suggestive of STI infection to the study clinic. | Before-after study design with a prospective cohort. Assessments at baseline (N=477) and 2-years post-intervention (N=436). Analysis limited to the 260 men who completed both questionnaires. Non-random sampling of participants. | HIV knowledge, Condom use |

| Adult heterosexual men and women | |||||

| Morisky et al., 2004 | Philippines |

High-risk male heterosexual populations Mean Age: 34.7 years |

Peer counselors were expected to educate at least 10 of their peers on STI/HIV/AIDS prevention and distribute IEC materials including posters, stickers and photonovellas. | Cross-over time series design comparing an intervention and delayed control. Assessments at baseline (N=3389), 12-months (N=3389) and 30-months (N=3389). Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge, STI infection, Condom use |

| Ngugi et al., 1996 (Kenya) | Kenya (Korogocho slum) | Pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in the Korogocho slum. Age Distribution Not Reported |

Each peer educator was responsible for a group of 20 peers and served as a resource, an HIV/AIDS educator and a promoter and distributor of condoms. In addition, women were screened and treated for syphilis. | Pre/post serial cross sectional design with control group. Assessments at baseline (N=973) and 7–14 months (N=516). Non-random selection of participants. | STI infection |

| Norr et al., 2004 | Botswana |

Target population: urban employed women |

Peer eductors delivered six 90-minute weekly or biweekly HIV/AIDS education sessions. Each session included role plays to build communication skills related to that session’s content. | Non-randomized group trial comparing an intervention group to a delayed control group. Assessments at baseline (N=403) and 4-months (N=278). Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge, Condom use |

| Wang et al., 2005 | China (Sichuan Province) | Men from the Yi, Tibetan, and Han cultural communities Age Range: 17 to 39 |

Peer educators delivered safe sex role model stories to their peers. Each trained peer educator was asked to tell their role model stories to at least 8–15 peers within 3 months. | Non-randomized intervention trial with three groups: directly trained peer educators; individuals who had received information from peer educators; and a control group who received no intervention. Assessments at baseline (N=450) and 5-months (N=450). | HIV knowledge, Condom use |

| Prisoners | |||||

| Dolan et al., 2004 | Russia (Siberia) | Drug-dependent male prisoners Mean age: 24 (Range 18 to 30 years) |

Trained peer educators distributed information leaflets and general health care booklets to other prinsoners. Condoms were given to staff to make available to inmates. | Pre/post serial cross sectional design. Assessments at baseline (N=153) and 12-month follow-up (N=124). Individual unit of analysis. Cell blocks randomly selected for intervention assessment. All prisoners living on block invited to complete questionnaire. | STI infection |

| Vaz et al., 1996 | Mozambique (Maputo) | Male prison inmates Mean Age: 26 years Range (15–70 years) |

Prisoners attended 3 educational sessions on AIDS and STDs, led by trained, primary school educated, prisoner activists. Prisoners also created a theatre group that performed monthly shows for the entire prison focusing on STD/AIDS prevention. | A before and after study design with no control group. Assessments at baseline (N=300) and 6-months (N=300). Non-random selection of participants. | HIV knowledge |

| Multiple target groups | |||||

| Laukamm-Josten et al, 2000 | Tanzania | Truck drivers and their sex partners Gender: 58% males; 42% females Median age: men, 32yrs; women, 24 years |

Truck stop workers and truck drivers were trained to educate their peers on HIV transmission and prevention, correct condom use and negotiating skills during an 18-month intensive intervention period. This was followed by 24-month maintenance period with fewer trainings and less support provided to peer educators. | Serial cross sectional study design with assessments at baseline (N=729), 18-months (N=319), and 24-months (N=623). Male truck divers were selected using non-probability sampling. Female truck stop workers were randomly selected for assessment. | HIV knowledge, STI infection, Condom use |

| Walden et al., 1999 | Malawi | Target pop: Female bar-based sex workers and male long-distance truck drivers; Gender: 55% female; 45% male Age: NR |

Sex workers and truck drivers were trained to give information on HIV/AIDS, to promote and distribute condoms, and to teach safe sex negotiation skills. | A cross-sectional study design with three arms (active districts - peer education training took place in the last year; non-active - no training since initial training; and average - training had taken place but there was little observed activity). 424 bar-based workers and 347 long distance truck drivers were included in the analysis. Non-random sampling of participants. | HIV knowledge, Condom use |

| Williams et al., 2003 | South Africa (Carletonville) | Target population: Mine workers, sex workers, and adults and youth (age 15–24 years) in the general community Age range: 15–49 years |

The intervention included recruiting and training peer educators from among sex workers, mine workers, and youth in the area; distributing condoms; and training health service providers in syndromic management of STI. Monthly periodic presumptive treatment for curable STI among sex workers was also included. |

Serial cross sectional design. Assessments at baseline (mine workers, N=899; sex workers, N=121; general population, N=1134) and 26-months (mine workers, N=769; sex workers, N=93; general population, N=1499). Mixed sampling used to recruit participants. Random selection of mine workers and community members. Non-random selection of sex workers. | HIV knowledge, STI infection, Condom use |

RESULTS

Description of studies

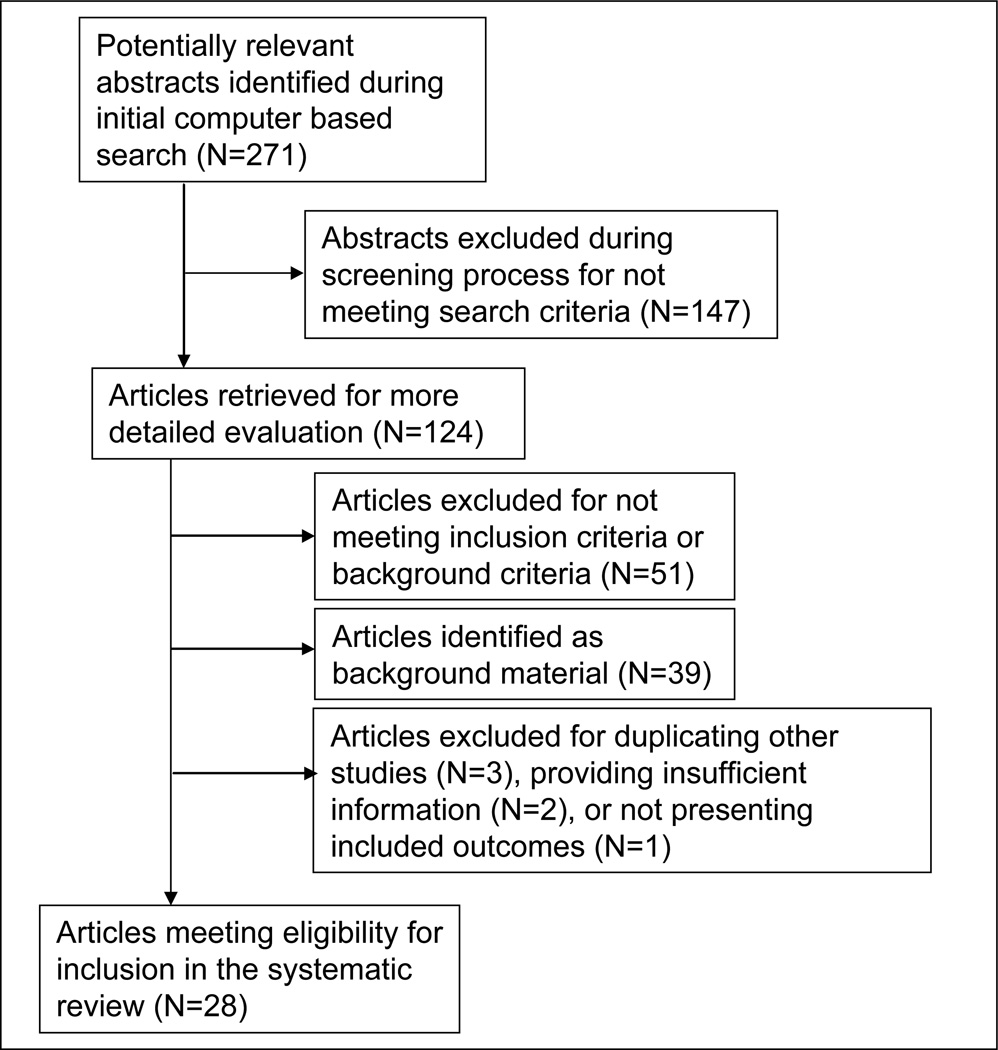

Out of 271 potentially relevant articles discovered in initial searching, thirty-four articles met our predefined inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Six of these thirty-four articles were not included in the meta-analysis because they either included the same intervention and study population as another article (Agha, 2002; Morisky, Chiao, Stein, & Malow, 2005; Morisky, Nguyen, Ang, & Tiglao, 2005), provided insufficient information for the meta-analysis (Basu, Jana, Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, Lee, Newman et al., 2004; Sloan & Myers, 2005), or did not include one of the four outcomes of interest (Brieger et al., 2000). One article presented the results of three different studies (Ngugi, Wilson, Sebstad, Plummer & Moses, 1996). Each of these three studies was treated separately in the meta-analysis, giving a total of 30 included studies from 28 articles. The characteristics of each study are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Disposition of citations during search process

Of these thirty studies, thirteen were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, ten in East and Southeast Asia, five in Central Asia, and two in Latin America and the Caribbean. Target populations included youth (N=8), commercial sex workers (CSWs) (N=12), injection drug users (IDUs) (N=4), transport workers (N=3), heterosexual adults (N=6), prisoners (N=2), and miners (N=1).

Study design rigor was mixed; rigor scores ranged from 1 to 6, with a mean score of 2.8 out of 8, which is the most rigorous (Table 2). Only three studies employed a randomized controlled design. The remaining studies included twelve serial cross-sectional studies, two post-only cross-sectional studies, ten before/after studies, and three non-randomized trials.

Table 2.

Study quality assessment (rigor)

| Study | Cohort | Control or comparison group |

Pre/post intervention data |

Random assignment of participants to the intervention |

Random selection of participants for assessment |

Follow- up rate of 80% or more |

Comparison groups equivalent on socio- demographics |

Comparison groups equivalent at baseline on outcome measure |

Final score out of 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agha, 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Asamoah, 1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | NR | NR | 1 | 5 |

| Asamoah, 1994 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Broadhead, 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR1 | NR1 | 3 |

| Dolan, 2004 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 2 |

| Ergene, 2005 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | NA | 1 | NA | 3 |

| Ford, 2000 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA | NR | 1 | 3 |

| Gao, et. al., 2001 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | 1 | 5 |

| Hammett, 2006 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 1 |

| Kinsler, 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Laukamm-Josten., 2000 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | NR | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Leonard, 2000 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 2 |

| Li et. al., 2001 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 |

| Merati et.al., 1997 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Morisky et al., 2006 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Morisky et al., 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NR | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Ngugi et. al., 1996 (Kenya, CSWs) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NR | N/A | N/A | 2 |

| Ngugi et. al., 1996 (Zimbabwe) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | NR | NR | 2 |

| Ngugi et. al., 1996 (Kenya, adults) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Norr et. al, 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ozcebe et. al, 2004 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NR | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Sergeyev et al., 1999 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | 2 |

| Speizer, 2001 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Thomsen, 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | NA | NA | 4 |

| Van Griensven, 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | NR | NA2 | 0 | NR | 3 |

| Vaz, 1996 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A | 3 |

| Walden, 1999 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | NR | NA | 1 |

| Wang, 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | NR | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Welsh et. al., 2001 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Williams et. al, 2003 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 |

Participants’ characteristics at baseline for the intervention and comparison group are presented, but, no statistical analysis was reported. Similarly although authors report the proportions of risk behaviors at baseline for the two groups, they do not report the result of any statistical analysis.

Authors only use data from participants who had completed both pre- and post-intervention surveys.

Impact of peer education on outcome measures

Table 3 presents a summary of the random-effects pooled effect sizes for the four outcomes, both overall and stratified by the seven target populations.

Table 3.

Summary of meta-analysis results by outcome and target population

| HIV Knowledge | Equipment Sharing | Condom Use All Partners |

Condom Use Regular Partners |

Condom Use Casual Partners |

STI Infection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of Study Population | 15,989 | 3,240 | 17,916 | 3,393 | 7,250 | 11,105 |

| Overall Pooled Effects Size (95% CI) | 2.28 (1.88, 2.75)*** | 0.37 (0.20, 0.67)** | 1.92 (1.59, 2.33)*** | 1.94 (1.27, 2.94)** | 2.23 (1.70, 3.09)*** | 1.22 (0.88, 1.71) |

| Q-statistic for Heterogeneity | 514.25*** | −117.06*** | 289.76*** | 42.35*** | 52.159*** | 62.78*** |

| Pooled Effects Size by Target Population (95% CI) | ||||||

| Youth and Adolescents | 2.52 (1.62, 3.92)*** | N/A | 1.12 (0.85, 1.48) | 0.53 (0.28, 1.00) | 1.93 (0.43, 8.60) | N/A |

| Injection Drug Users | 1.52 (1.31, 1.76)*** | 0.37 (0.20, 0.67)** | 1.49 (1.05, 2.10)* | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Commercial Sex Workers | 1.66 (1.19, 2.33)** | N/A | 2.31 (1.66, 3.23)*** | 1.66 (1.06, 2.60)* | 1.25 (0.38, 4.14) | 1.15 (0.64, 2.04) |

| Transport Workers | 1.28 (0.62, 2.660) | N/A | 2.43 (1.68, 3.52)*** | 2.23 (0.96, 5.17) | 2.93 (2.39, 3.60)*** | 1.95 (1.45, 2.62)*** |

| Heterosexual Adults | 3.46 (2.10, 5.69)*** | N/A | 1.84 (1.34, 2.53)*** | 4.47 (2.33, 8.60)*** | 3.35 (1.72, 6.53)*** | 0.94 (0.59, 1.49) |

| Prisoners | 8.27 (5.00, 13.68)*** | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.40 (0.81, 2.43) |

| Miners | 2.49 (2.06, 3.02)*** | N/A | 1.97 (1.31, 2.97)** | N/A | 2.45 (1.91, 3.14)*** | 1.90 (0.89, 4.07) |

p<0.0001,

p<0.001,

p<0.05

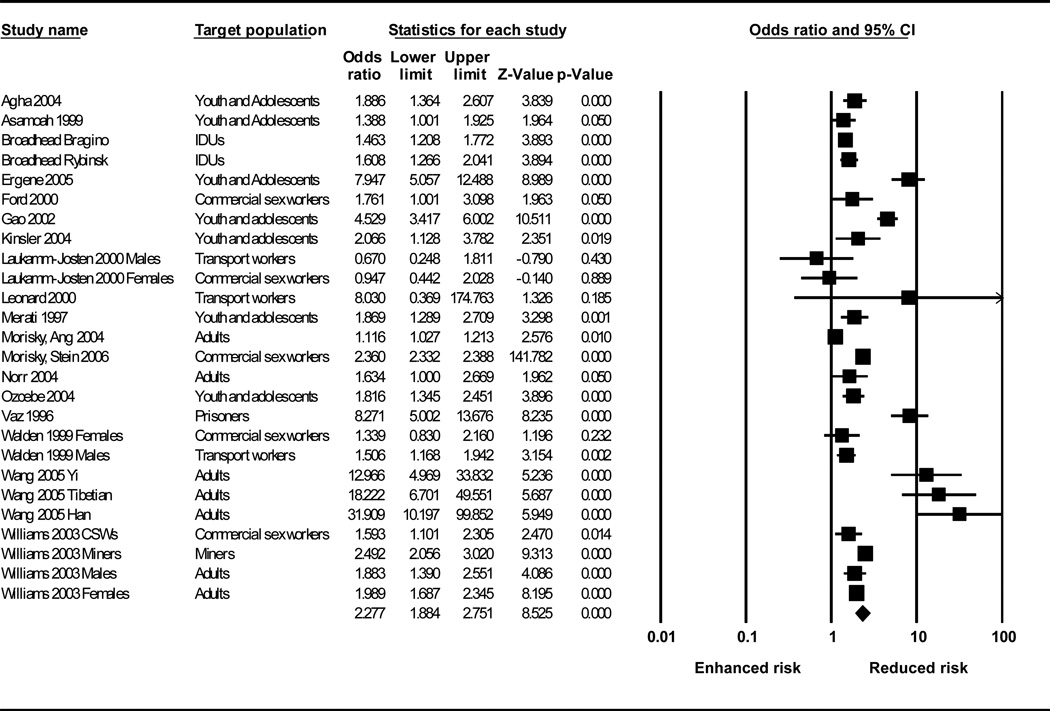

HIV knowledge

Eighteen studies (Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Asamoah, 1999; Merati et al., 1997; Ford et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2006; Broadhead et al., 2006; Ergene, Cok, Tumer & Unal, 2005; Gao et al., 2002; Ozcebe, Akin & Aslan, 2004; Kinsler, Sneed, Morisky & Ang, 2004; Leonard et al., 2000; Morisky, Ang, Coly & Tiglao, 2004; Norr, Norr, McElmurry, Tlou, & Moeti, 2004; Wang & Keats, 2005; Williams et al., 2003; Vaz, Gloyd, & Trindade, 1996; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000; Walden, Mwangulube & Makhumula-Nkhoma, 1999), with a combined study population of 15,989, generated twenty-six discrete effect size estimates on HIV knowledge (Table 4). Pooled, these data show that peer education had a moderate but positive effect on this outcome (OR: 2.28, 95% CI: 1.88, 2.75). The Q statistic for heterogeneity of 514.29 was statistically significant (p<0.0001) indicating variation across studies. Stratifying the discrete random effect size estimates by target population, peer education was significantly associated with an increase in HIV knowledge among all populations except transport workers (Table 3).

Table 4.

Meta-analysis: random effects model: HIV knowledge

|

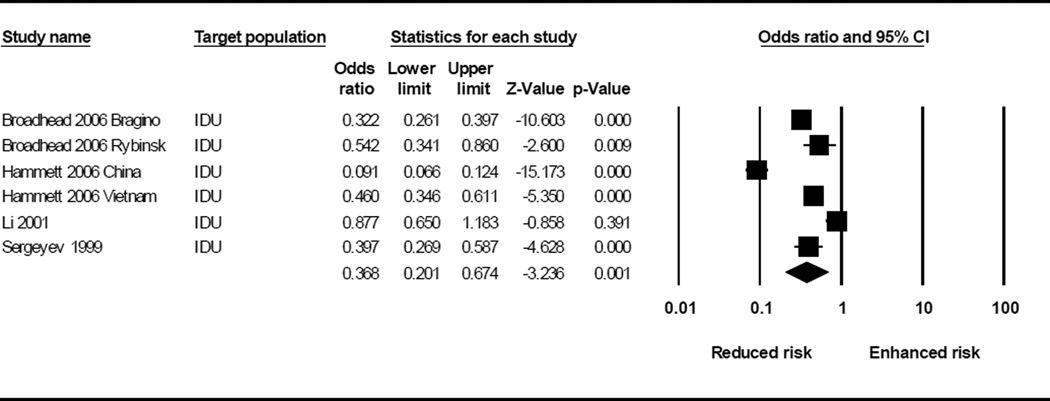

Equipment sharing

Four studies (Broadhead et al., 2006; Sergeyev et al., 1999; Hammett et al., 2006; Li et al., 2001), with a combined study population of 3,240, generated six discrete effect sizes on equipment sharing (Table 5). Three of the four studies showed statistically significant positive effects on equipment use (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Broadhead et al., 2006; Hammett et al., 2006). In one such study, receptive needle sharing during the past 6 months decreased significantly between baseline and the 24-month follow-up (47% versus 11%) (Hammett et al., 2006). However, another study showed non-significant changes in needle sharing before and after the intervention (68.3% versus 62.0%) (Li et al., 2001). This study was carried out in a drug rehabilitation center in China and the authors attribute the insignificant results to the high attrition rate among peer educators. The meta-analysis of these four studies (Table 5) showed a statistically significant reduction in equipment sharing (OR: 0.37; 95% CI: 0.20, 0.67).

Table 5.

Meta-analysis: random effects model: equipment sharing

|

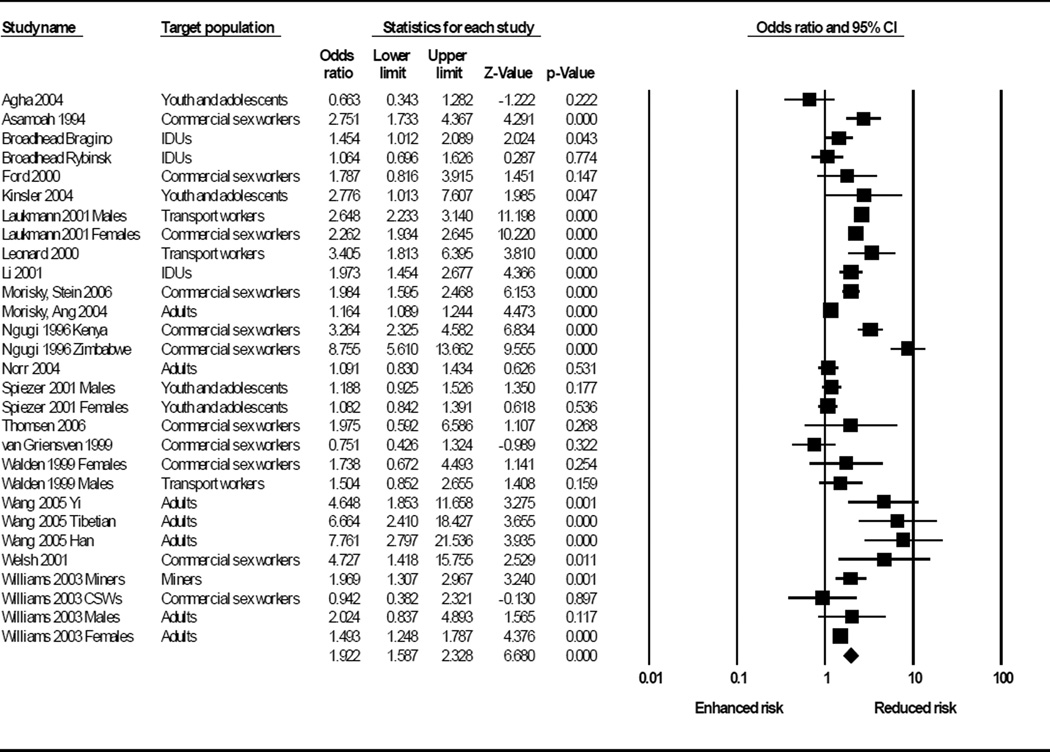

Condom use

Nineteen studies (Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Ford et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2006; Broadhead et al., 2006; Li et al., 2001; Ngugi et al., 1996; Kinsler et al., 2004; Speizer, Tambashe & Tegang, 2001; Asamoah et al., 1994; Thomsen et al., 2006; van Griensven, Limanonda, Ngaokeow, Ayuthaya, & Poshyachinda, 1998; Welsh, Puello, Meade, Kome, & Nutley, 2001; Leonard et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2004; Norr et al., 2004; Wang & Keats, 2005; Williams et al., 2003; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000; Walden et al., 1999) with a combined study population of 17,916 individuals, generated twenty-nine discrete effect size estimates for condom use (Table 6). Results across these studies were mixed and varied by target population (Table 3). For example, only one of three studies among youth showed positive effects on condom use (Kinsler et al., 2004). The other two studies showed no intervention effects on reported condom use (Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Speizer et al., 2001), resulting in a non-significant pooled effect size for condom use among youth (OR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.85, 1.48). However, positive intervention effects were observed among IDUs, CSWs, transport workers, heterosexual adults, and miners. When results for all target populations were combined, there was a statistically significant positive impact of peer education on condom use (OR: 1.92; 95% CI: 1.59, 2.33) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Meta-analysis: random effects model: condom use

|

We also stratified the meta-analysis results for condom use by partner type (Table 3) and found moderate increases with both casual (OR: 2.23; 95% CI: 1.70, 3.09) and regular (OR: 1.94; 95% CI: 1.28, 2.94) partners. Again, there were no intervention effects among youth for either regular or casual partners. Among CSWs, there was a small intervention effect on condom use with regular partners (OR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.06, 2.60), but no observed effect among casual partners (OR: 1.25; 95% CI: 0.38, 4.14). In contrast, among transport workers, there was a positive intervention effect on condom use with casual partners (OR: 2.93; 95%CI: 2.39, 3.60), but no effect with regular partners (OR: 2.23; 95%CI: 0.96, 5.17). Among heterosexual adults, positive intervention effects were observed for both casual and regular partners.

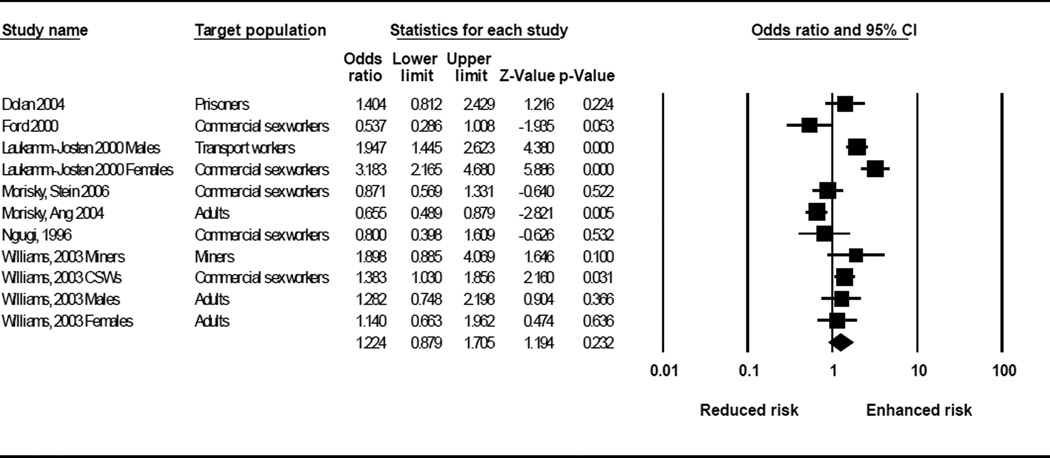

STI infection

Seven studies (Ford et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2006; Ngugi et al., 1996; Morisky et al., 2004; Williams et al., 2003; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000; Dolan, Bijl & White, 2004) with a combined study population of 11,105 yielded eleven discrete effect size estimates for STI infection (Table 7). Pooled, these data reveal a non-significant increase in STI infection following the intervention (OR: 1.22; 95% CI: 0.88, 1.71). This finding was driven by three studies that reported an increase in STI infection following peer education programs (Williams et al., 2003; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000; Dolan et al., 2004).

Table 7.

Meta-analysis: random effects model: STI prevalence

|

Implementation issues

Differences in effectiveness across studies may be attributable to evaluation methods, context-specific factors, or different ways in which interventions are implemented. These implementation issues are analyzed below.

Recruiting peer educators

Peer education interventions are dependent upon the individuals who are chosen to be the peer educators, and the proper selection of peer educators is therefore key to program success. However, of the 30 studies included in this review, 16 did not report how peer educators were recruited. Of those that did report this information, three studies used self-nominated volunteers (Li et al., 2001; Ergene et al., 2005; Welsh et al., 2001). In six studies the peer educators were nominated by the target audience or through snowball recruitment (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Broadhead et al., 2006; Ngugi et al., 1996; Leonard et al., 2000; Norr et al., 2004; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000), while in five studies the peer educators were nominated by other individuals (Merati et al., 1997; Morisky et al., 2006; Hammett et al., 2006; Kinsler et al., 2004; Dolan et al., 2004), usually program staff or supervisors of the target audience, such as prison staff (Dolan et al., 2004), brothel owners/managers (Morisky et al., 2006), and youth group leaders (Merati et al., 1997).

Similarly, how peer educators are recruited can determine how they are perceived by the target population. For example, peer educators chosen by their peers might be expected to be more popular, but less motivated than volunteers, or less skilled than peer educators chosen by program staff. Unfortunately, only 3 of 30 articles discussed how their recruitment strategies affected the implementation or success of their interventions. One study reported that their program worked “because the peer counselors were carefully selected, and were considered influential leaders among the different groups” (Morisky et al., 2004). On the other hand, another article noted that because they used a snowball recruitment approach, they did not expect all recruits to be good peer educators (Broadhead et al., 2006).

Stratifying the meta-analysis by recruitment method was possible for two outcomes: HIV knowledge and condom use. All three recruitment strategies yielded significant increases in both HIV knowledge (self-nomination: OR=7.95, 95%CI: 5.06, 12.49; target audience nomination: OR=1.38, 95%CI: 1.06, 1.79; other nomination: OR=2.36, 95%CI: 2.33, 2.39) and condom use (self-nomination: OR=2.50, 95%CI: 1.17, 5.33; target audience nomination: OR=2.84, 95%CI: 1.89, 4.27; other nomination: OR=2.01, 95%CI: 1.63, 2.49).

Training and supervision of peer educators

Training and supervision of peer educators is also likely to be an important factor in intervention effectiveness. However, seven studies did not describe what, if any, training peer educators received (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Li et al., 2001; Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Ngugi et al., 1996; Asamoah et al., 1994; Thomsen et al., 2006; Williams et al., 2003), while three studies reported that peer educators were trained but did not provide details of that training (Ngugi et al., 1996; Gao et al., 2002; Welsh et al., 2001). Fifteen studies reported that peer educators received a one-time training course that ranged in length from a few days to two months (Merati et al., 1997; Ford et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2006; Broadhead et al., 2006; Asamoah, 1999; Ergene et al., 2005; Ozcebe et al., 2004; Kinsler et al., 2004; van Griensven et al., 1998; Morisky et al., 2004; Norr et al., 2004; Wang & Keats, 2005; Vaz et al., 1996; Walden et al., 1999; Dolan et al., 2004). Only five studies reported that peer educators were provided refresher training beyond the initial training program (Hammett et al., 2006; Ngugi et al., 1996; Speizer et al., 2001; Leonard et al., 2000; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000). Stratifying the meta-analysis by one-time training versus on-going refresher training was again possible for two outcomes: HIV knowledge and condom use. For HIV knowledge, one-time training was associated with increased knowledge, whereas refresher training was not associated with a change in HIV knowledge (one-time training: OR=2.52, 95%CI: 1.95, 3.27; refresher training: OR=0.92, 95%CI: 0.47, 1.80). For condom use, both one-time and on-going refresher training were associated with increased condom use (one-time training: OR=1.66, 95%CI: 1.29, 2.13; refresher training: OR=2.49, 95%CI: 1.67, 3.72).

Similarly, eleven studies did not mention the level of supervision peer educators received, though one of these studies did note that peer educators wanted more supervision (Asamoah et al., 1994). Three studies reported that no supervision was given after the initial training session (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Broadhead et al., 2006; Wang & Keats, 2005). Four other studies mentioned that peer educators were supervised “regularly” or “throughout the project”, but did not provide specifics (Merati et al., 1997; Ngugi et al., 1996; Welsh et al., 2001; Ergene et al., 2005). Ten studies noted the frequency of supervision as every session (Vaz et al., 1996), twice weekly (Ford et al., 2000), weekly (Agha & van Rossem, 2004; Hammett et al., 2006; Leonard et al., 2000; Morisky et al., 2004), biweekly (van Griensven et al., 1998), monthly (Morisky et al., 2006; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000), or quarterly (Speizer et al., 2001). Both on-going supervision and no supervision beyond training were associated with positive changes in HIV knowledge (on-going supervision: OR=2.22, 95%CI: 1.52, 3.23; no supervision: OR=5.66, 95%CI: 2.60, 12.31) and condom use (on-going supervision: OR=1.94, 95%CI: 1.41, 2.65; no supervision: OR=2.87, 95%CI: 1.40, 5.91) in stratified meta-analysis.

Compensation

Peer education is often believed to be more cost-effective than other interventions because it uses volunteers, or minimally paid peers to deliver information (Milburn, 1995). Compensation of peer educators, therefore, varies widely, and the effect of compensation on intervention efficacy is unknown. Of the 8 studies that discussed compensation, only one provided no financial compensation; the school-aged peer educators in this intervention later received course credit for participation (Gao et al., 2002). The remaining seven studies generally provided small amounts of money to reimburse time or travel expenses (Morisky et al., 2006; Ergene et al., 2005; Ozcebe et al., 2004; Wang & Keats, 2005; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000) or give incentives for educating others (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Broadhead et al., 2006). All of these studies showed positive intervention effects on condom use (Morisky et al., 2006; Wang & Keats, 2005; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000), HIV knowledge (Ozcebe et al., 2004; Morisky et al., 2006; Broadhead et al., 2006; Ergene et al., 2005; Wang & Keats, 2005), and equipment sharing (Sergeyev et al., 1999; Broadhead et al., 2006).

Retention

Retention of trained peer educators is crucial to program effectiveness and sustainability. However, retention may be difficult since peer education interventions are often conducted with marginalized or hidden populations such as CSWs or IDUs. Twenty studies did not discuss retention of peer educators. Of the ten studies that reported retention of peer educators, one reported high retention rates among in-school youth (Speizer et al., 2001). The remainder reported mediocre to poor retention, either of previous trainees (Williams et al., 2003) or current peer educators (Ford et al., 2000; Hammett et al., 2006; Li et al., 2001; Welsh et al., 2001; Laukamm-Josten et al., 2000; Walden et al., 1999). As expected, retention seemed particularly difficult in marginalized or hidden populations. For example, two interventions with CSWs found dropout rates of 50% in the first month (Ford et al., 2000) and four months (Walden et al., 1999) respectively. Similarly, two studies attributed high turnover in IDU peer educators to a cycle of drug use and rehabilitation (Hammett et al., 2006; Li et al., 2001).

DISCUSSION

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis yielded thirty studies that examined the effectiveness of peer education programs for HIV prevention in developing countries. These thirty studies covered a broad range of both countries and target populations. Study designs were mostly cross-sectional in nature or before-after studies with no comparison. Despite generally weak study designs, combined data from these studies showed an overall positive effect on behavioral outcomes. Peer education interventions were associated with increased HIV knowledge, reduced equipment sharing among IDUs, and increased condom use. These findings are encouraging and support the use of peer education programs in these settings. They also suggest that peer education can be an effective strategy for changing behavior among hard-to-reach, hidden populations such as CSWs and IDUs. However, while statistically significant, the effect sizes were moderate. Given limited resources, public health practitioners need to consider what effect sizes are programmatically significant.

The only reported biological outcome was STI infection, which in meta-analysis showed a null effect. This may indicate that while peer education programs can lead to positive changes in knowledge and behaviors, these changes may not result in biological impact. However, of the seven studies that measured STI infection, none used a randomized control design and only one included a cohort. Specifically, the three studies with negative results that drove the meta-analysis were all serial cross-sectional studies with an average rigor of 1.7. Weak study designs may have limited the ability of these studies to detect differences in this outcome. Further research with more rigorous designs will be needed to examine the long-term impact of peer education programs on distal outcomes such as STI incidence/prevalence and ultimately HIV incidence/prevalence.

To understand how issues such as peer educator recruitment, supervision, and training affect program success we stratified the analysis by key implementation issues. These stratified analyses did not reveal any important differences on the effectiveness of these interventions in changing behavioral and biological outcomes. Unfortunately, many articles did not report on these implementation issues. This reduced the sample size for the stratified analyses and may have limited our ability to detect important differences in program success. Moreover, even when articles did discuss implementation issues, there was no consistent way to compare across interventions. Operational research is needed to identify the factors that maximize program success. Additionally, future articles that report on peer education interventions should include more detailed descriptions of their programs so that best practices can be identified and the impact of different strategies on outcomes can be examined.

Limitations to the meta-analysis and the included studies should be considered when interpreting these findings. In addition to the limitations described above, the measurement of outcome variables varied greatly across studies. For example, condom use was alternatively defined as ever use, use at last sex, or consistent use at every sex act. Moreover, articles often stratified condom use by partner type, further complicating comparisons across studies. In order to fully utilize all of these data, we averaged the results of all definitions for each outcome across the different sub-groups within studies, and used that result in meta-analysis. However, so as not to hide important differences in effects among sub-groups, we also reported condom use stratified by partner type and by target population. Similarly, STI infection was variously reported as STI incidence, current prevalence, and lifetime prevalence, and was measured by self-report, chart review, and/or clinical diagnosis. A widely used, standardized set of measures for condom use, HIV knowledge, and other behavioral and biological outcomes would facilitate future comparisons across studies.

In summary, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of peer education programs as an HIV prevention strategy in developing countries. The findings provide evidence that peer education programs are effective at improving knowledge and behavioral outcomes. While study designs were frequently weak, there were consistent positive effects with moderate effect sizes. However, peer education programs had no significant impact on STI infection. Unfortunately, there has been no comparable review of these interventions in developed countries, so we are unable to compare whether these interventions are more or less efficacious in developing versus developed country settings. Evaluation and critical examination of peer education programs, including exploration of implementation issues that may affect program effectiveness, are needed in order to strengthen the impact that these interventions have on changing HIV-related behavior and ultimately in reducing the incidence of HIV infections globally.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Anne Palaia, Amy Gregowski, Priya Emmart, Rae Hower, Elizabeth Jere, Sarah Mauch, Carolyn Pleisca, Andrea Ippel, Morgan Philbin, Andrea Wirtz, Devaki Nambiar, Jennifer Gonyea, Sidney Callahan, Lisa Fiol Powers, Alexandra Melby, and Lauren Tingey for their coding work.

Support: This research was supported by the World Health Organization, Department of HIV/AIDS, the US National Institute of Mental Health, grant number R01 MH071204, and the Horizons Program. The Horizons Program is funded by the US Agency for International Development under the terms of HRN-A-00-97-00012-00.

Appendix

The following search terms were used when searching electronic databases: peer education and HIV; peer counseling and HIV; peer teaching and HIV; peer interventions and HIV; peer approaches and HIV; peer outreach and HIV; peer meetings and HIV; peer education and AIDS; peer counseling and AIDS; peer approaches and AIDS; peer outreach and AIDS; peer meetings and AIDS; peer evaluation and HIV; peer and HIV and intervention; peer leaders and HIV; peer networks and HIV

REFERENCES

- Agha S, van Rossem R. Impact of a school-based peer sexual health intervention on normative beliefs, risk perceptions, and sexual behavior of Zambian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34(5):441–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agha S. An evaluation of the effectiveness of a peer sexual health intervention among secondary-school students in Zambia. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2002;14(4):269–281. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.5.269.23875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah A. Effects of adult-led didactic presentation and peer-led discussion on AIDS-knowledge of junior secondary school students. IFE Psychologia: An International Journal. 1999;7(2):213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Asamoah A, Weir S, Pappoe M, Kanlisi N, Neequaye Al, Lamptey P. Evaluation of a targeted AIDS prevention intervention to increase condom use among prostitutes in Ghana. AIDS. 1994;8(2):239–246. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199402000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus M, Swendeman D, Lee SJ, Newman P, Weiss R. HIV Prevention Among Sex Workers in India. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(3):845–852. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, O'Reilly K, Denison J, Anhang R, Sweat M. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries. Health Education Research. 2006;21(4):567–597. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieger W, Delano G, Lane C, Oladepo O, Oyediran K. West African Youth Initiative: outcome of a reproductive health education program. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(6):436–446. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead R, Volkanevsky V, Rydanova T, Ryabkova M, Borch C, van Hulst Y, Fullerton A, Sergeyev B, Heckathorn D. Peer-driven HIV interventions for drug injectors in Russia: First year impact results of a field experiment. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(5):379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: Participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(2):331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Mzaidume Z. Grassroots participation, peer education, and HIV prevention by sex workers in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(12):1978–1986. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.12.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, editors. The handbook of research synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Denison J, O’Reilly K, Schmid G, Kennedy C, Sweat M. HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: a meta-analysis 1990–2005. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(3):363–373. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K, Bijl M, White B. HIV education in a Siberian prison colony for drug dependent males. Int J Equity Health. 2004;3(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergene T, Cok F, Tumer A, Unal S. A controlled-study of preventive effects of peer education and single-session lectures on HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitudes among university students in Turkey. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2005;17(3):268–278. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.4.268.66533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan D, Suastina W, Reed B, Muliawan P. Evaluation of a peer education programame for female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2000;11(11):731–733. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Shi R, Lu Z, Qiu Y, Niu W, Short R. An effective Australian-Chinese peer education program on HIV/AIDS/STDs for university students in China. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2002;11(suppl 1):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Kling R, Johnston P, Liu W, Ngu D, Friedmann P, Binh K, Dong H, Van L, Donghua M, Chen Y, Des Jarlais D. Patterns of HIV prevalence and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users prior to and 24 months following implementation of cross-border HIV prevention interventions in Northern Vietnam and Southern China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(2):97–115. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton G, Wyss K, N’Diekhor Y. Prioritization of prevention activities to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS in resource constrained settings: a cost-effectiveness analysis from Chad, Central Africa. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2003;18(2):117–136. doi: 10.1002/hpm.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy C, O'Reilly K, Medley A, Sweat M. The impact of HIV treatment on risk behaviour in developing countries: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2007;19(6):707–720. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukamm-Josten U, Mwizarubi B, Outwater A, Mwaijonga C, Valadez J, Nyamwaya D, Swai R, Saidel T, Nyamuryekung'e K. Preventing HIV infection through peer education and condom promotion among truck drivers and their sexual partners in Tanzania 1990–1993. AIDS Care. 2000;12(1):27–40. doi: 10.1080/09540120047440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard L, Ndiaye I, Kapadia A, Eisen G, Diop O, Mboup S, Kanki P. HIV prevention among male clients of female sex workers in Kaolack, Senegal: results of a peer education program. AIDS Educ Prev. 2000;12(1):21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Luo J, Yang F. Evaluation on peer education program among injecting drug users. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi. 2001;22(5):334–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merati T, Ekstrand M, Hudes E, Suarmiartha E, Mandel J. Traditional Balinese youth groups as a venue for prevention of AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl 1):S111–S119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milburn K. A critical review of peer education with young people with special reference to sexual health. Health Education Research. 1995;10(4):407–420. doi: 10.1093/her/10.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D, Stein J, Chaio C. Impact of a social influence intervention on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female sex workers in the Philippines: a multilevel analysis. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):595–603. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D, Chiao C, Stein J, Malow R. Impact of Social and Structural Influence Interventions on Condom Use and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Establishment-Based Female Bar Workers in the Philippines. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2005;17(1):45–63. doi: 10.1300/J056v17n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D, Nguyen C, Ang A, Tiglao T. HIV/AIDS prevention among the male population: results of a peer education program for taxicab and tricycle drivers in the Philippines. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky D, Ang A, Coly A, Tiglao T. A model HIV/AIDS risk reduction program in the Philippines: A comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promotion International. 2004;19(1):69–76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi E, Wilson D, Sebstad J, Plummer F, Moses S. Focused peer-mediated educational programs among female sex workers to reduce sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus transmission in Kenya and Zimbabwe. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl 2):S240–S247. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norr K, Norr J, McElmurry B, Tlou S, Moeti M. Impact of peer group education on HIV prevention among women in Botswana. Health Care for Women International. 2004;25(3):210–226. doi: 10.1080/07399330490272723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcebe H, Akin L, Aslan D. A peer education example on HIV/AIDS at a high school in Ankara. Turk J Pediatr. 2004;46(1):54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkerton S, Holtgrave D, DiFranceisco W, Stevenson L, Kelly J. Cost-effectiveness of a community-level HIV risk reduction intervention. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(8):1239–1242. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.8.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Council. Peer Education and HIV/AIDS: Past Experience, Future Directions. [Accessed on: April 2, 2008];2000 Available at: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/peer_ed.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Sergeyev B, Oparina T, Rumyantseva T, Volkanevskii V, Broadhead R, Heckathorn D, Madray H. HIV Prevention in Yaroslavl, Russia: A Peer-Driven Intervention and Needle Exchange. Journal of Drug Issues. 1999;29(4):777–803. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan N, Myers J. Evaluation of an HIV/AIDS peer education programme in a South African workplace. S Afr Med J. 2005;95(4):261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer I, Tambashe B, Tegang S. An evaluation of the "Entre Nous Jeunes" peer-educator program for adolescents in Cameroon. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(4):339–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange V, Forrest S, Oakley A. Peer-led sex education--characteristics of peer educators and their perceptions of the impact on them of participation in a peer education programme. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):327–337. doi: 10.1093/her/17.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: A Proposal for Reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweat M, O'Reilly K, Kennedy C, Medley A. Psychosocial support for HIV-infected populations in developing countries: a key yet understudied component of positive prevention. AIDS. 2007;21(8):1070–1071. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280f774da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao G, Remafedi G. Economic evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention for gay and bisexual male adolescents. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998;17(1):83–90. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199801010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen S, Ombidi W, Toroitich-Ruto C, Wong E, Tucker H, Homan R, Kingola N, Luchters S. A prospective study assessing the effects of introducing the female condom in a sex worker population in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(5):397–402. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Griensven G, Limanonda B, Ngaokeow S, Ayuthaya S, Poshyachinda V. Evaluation of a targeted HIV prevention programme among female commercial sex workers in the south of Thailand. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74(1):54–58. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz R, Gloyd S, Trindade R. The effects of peer education on STD and AIDS knowledge among prisoners in Mozambique. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 1996;7(1):51–54. doi: 10.1258/0956462961917069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden V, Mwangulube K, Makhumula-Nkhoma P. Measuring the impact of a behaviour change intervention for commercial sex workers and their potential clients in Malawi. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(4):545–554. doi: 10.1093/her/14.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Keats D. Developing an innovative cross-cultural strategy to promote HIV/AIDS prevention in different ethnic cultural groups of China. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):874–891. doi: 10.1080/09540120500038314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh M, Puello E, Meade M, Kome S, Nutley T. Evidence of diffusion from a targeted HIV/AIDS intervention in the Dominican Republic. J Biosoc Sci. 2001;33(1):107–119. doi: 10.1017/s0021932001001079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Taljaard D, Campbell C, Gouws E, Ndhlovu L, van Dam J, Carael M, Auvert B. Changing patterns of knowledge, reported behaviour and sexually transmitted infections in a South African gold mining community. AIDS. 2003;17(14):2099–2107. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200309260-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Countries and Regions. 2008 Retrieved April 17, 2008 from http://www.worldbank.org/ [Google Scholar]