Abstract

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is a rare, difficult-to-diagnose genetic disorder of bile acid (BA) synthesis that can cause progressive neurological damage and premature death. Detection of CTX in the newborn period would be beneficial because an effective oral therapy for CTX is available to prevent disease progression. There is no suitable test to screen newborn dried bloodspots (DBS) for CTX. Blood screening for CTX is currently performed by GC-MS measurement of elevated 5α-cholestanol. We present here LC-ESI/MS/MS methodology utilizing keto derivatization with (O-(3-trimethylammonium-propyl) hydroxylamine) reagent to enable sensitive detection of ketosterol BA precursors that accumulate in CTX. The availability of isotopically enriched derivatization reagent allowed ready tagging of ketosterols to generate internal standards for isotope dilution quantification. Ketosterols were quantified and their utility as markers for CTX was compared with 5α-cholestanol. 7α,12α-Dihydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one provided the best discrimination between CTX and unaffected samples. In two CTX, newborn DBS concentrations of this ketosterol (120–214 ng/ml) were ∼10-fold higher than in unaffected newborn DBS (16.4 ± 6.0 ng/ml), such that quantification of this ketosterol provides a test with potential to screen newborn DBS for CTX. Early detection and intervention through newborn screening would greatly benefit those affected with CTX by preventing morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: leukodystrophy, CYP27A1, bile acid, ketosterol, newborn screening, LC-ESI-MS/MS, derivatization

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX; OMIM#213700) is an autosomal recessive adolescent-to-adult onset leukodystrophy associated with deficient sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1), a mitochondrial enzyme important in conversion of cholesterol to the bile acids (BA) cholic and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA; for pathways to primary BA, see Fig. 1) CTX is difficult to diagnose; for most affected individuals, it is not clinically obvious at birth, although neonatal cholestatic jaundice may occur in some infants (1, 2). The mean age of symptom onset has been estimated between 14 and 19 years old, and the mean delay in diagnosis between 17 and 19 years (3–5). Childhood onset symptoms can include diarrhea, juvenile cataracts, and developmental delay (3). Adolescent-to-adult onset symptoms include tendon and cerebral xanthomas. In 95–97% of patients, neurological symptoms have developed by the time of diagnosis (4, 5); these may include cognitive impairment, cerebellar signs (for example, ataxia), and pyramidal signs (for example, spasticity). As the disorder progresses, patients can become incapacitated with motor dysfunction, with premature death often occurring due to advancing neurological deterioration.

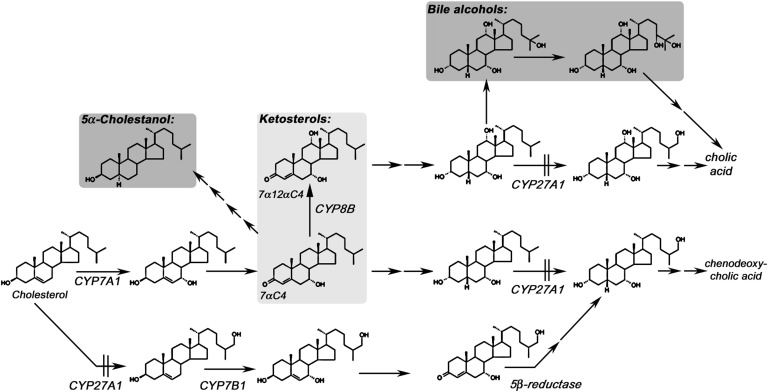

Fig. 1.

Pathways to primary BA. The major adult pathway is the neutral pathway initiated by CYP7A1-mediated 7α-hydroxylation of cholesterol. There is a minor pathway to CDCA termed the acidic pathway initiated by CYP27A1-mediated 27-hydroxylation of cholesterol followed by oxysterol 7α-hydroxylation. Synthesis of CDCA through both pathways is blocked in CTX with accumulation of ketosterol BA precursors, such as 7αC4 (from which most 5α-cholestanol is derived). Highlighted in dark gray are the disease markers routinely used to test for CTX; 5α-cholestanol in blood (16, 17), and bile alcohols (primarily pentol) in urine (18–20), and in light gray, ketosterol BA precursors, quantification of which we describe here provides an improved blood test for CTX.

Based on a 1:115 carrier frequency determined for the pathogenic CYP27A1 c.1183C>T mutation in Caucasians (6), the prevalence of CTX due to homozygosity for this mutation alone has been estimated as 1:52,000, although comprehensive prevalence data for CTX is lacking. Genetic islands of increased mutation frequency exist for CTX; for example, in an isolated Israeli Druze community, a carrier frequency of 1:11 for the deleterious c.355delC mutation was reported (7, 8). Despite these observations, only around three hundred cases of CTX have been described worldwide (9), although large series of patients have been described by physicians with experience in recognizing the disorder in Italy (9, 10), the Netherlands (3, 4), Japan (11), Spain (5), the United States, and Israel (12). CTX is likely not well recognized and under- or misdiagnosed.

An effective therapy for CTX is available in the form of oral CDCA, the main BA deficient in CTX. CDCA treatment has been shown to normalize the biochemical phenotype and halt progression of disease (10, 12). There are reports indicating treatment prevents the onset of disease complications in presymptomatic children (13, 14). Cholic acid treatment has been reported to be a less hepatotoxic alternative to CDCA in infants (13). Although treatment at every stage of disease is recommended (15), in many cases, treatment of patients with advanced neurological disease does not reverse the neurological impairment (10). Therefore, it is essential to diagnose and treat CTX as early as possible.

Although CTX fulfills the majority of criteria required for a disorder to be screened for in newborns, there is no suitable test to screen newborn dried bloodspots (DBS) for CTX. Blood testing for CTX is routinely performed using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) measurement of elevated 5α-cholestanol (16, 17), with diagnostic confirmation normally accomplished using fast atom bombardment (FAB)-MS measurement of elevated urinary bile alcohol glucuronides (18–20), which are more specific markers for CTX. Neither test would be useful as a biochemical test in newborn screening laboratories, where electrospray ionization-tandem MS (ESI-MS/MS) analysis of DBS is routinely performed.

A focus of our research has been to develop high-throughput, amenable ESI-MS/MS-based blood tests with utility to screen DBS for CTX (21, 22). We previously utilized keto-moiety derivatization with Girard's P reagent (1-(carboxymethyl) pyridinium chloride hydrazide) (23, 24) to enable sensitive isotope dilution LC-ESI-MS/MS quantification of plasma ketosterol BA precursors that accumulate in CTX (25–27). Although the method lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) that we reported (50–100 ng/ml) was close to the maximum circulating concentration of 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7αC4) in healthy individuals (28–31), we demonstrated 7αC4 possessed improved diagnostic utility over 5α-cholestanol as a marker of CTX (21). Recently keto derivatization with quaternary amonoxy (QAO) O-(3-trimethylammonium-propyl) hydroxylamine reagent to form a cationic oxime derivative enabled highly sensitive LC-ESI-MS/MS quantification of testosterone (32). We describe here development and application of this methodology utilizing QAO derivatization for LC-ESI-MS/MS quantification of ketosterol BA precursors in very small volumes of plasma (4 μl) or 3.2 mm DBS punches. The availability of isotopically enriched derivatization reagent allowed ready tagging of different ketosterols to generate stable isotope-labeled derivative internal standards for isotope dilution quantification. Free (nonhydrolyzed) ketosterol BA precursors in plasma or DBS, including newborn DBS, were quantified, and their utility as markers for CTX was compared with hydrolyzed 5α-cholestanol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subject research considerations

Whole blood and plasma was purchased commercially or was obtained from participants enrolled in studies at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) under Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. De-identified clinical samples submitted to the OHSU Lipid Laboratory for diagnostic confirmation of CTX using GC-MS measurement of elevated plasma 5α-cholestanol were used with IRB approval. For CTX-positive samples, diagnostic confirmation was by molecular genetic testing performed by the Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory of J. Chiang at OHSU. De-identified DBS from newborns later diagnosed with CTX from the Ontario and California newborn screening programs, as well as anonymized residual newborn DBS from the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory, were used with IRB approval.

Chemicals and reagents

7α-Hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7αC4), 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one-d7 (7αC4-d7), and 7α, 12α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (7α12αC4) were from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Ontario). 5α-cholestanol was from Steraloids (Newport, RI) and epicoprostanol from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). BSTFA reagent was from Thermo Scientific (Bellefonte, PA). Human plasma, double charcoal-stripped (DCS) plasma, and whole blood were from Golden West Bio (Temecula, CA). Methanol and water (GC-MS grade) were from Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI). Formic acid (90%) was J.T. Baker brand, and glacial acetic acid (99.99%) was from Aldrich. QAO reagent (O-(3-trimethylammoniumpropyl) hydroxylamine) bromide is commercially available as AmplifexTM Keto reagent from http://www.sciex.com. The QAO-d3 reagent was provided by AB SCIEX. Protein Saver 903 and DMPK A and DMPK B filter papers were obtained from Whatman (Miami, FL).

Preparation of calibrators and samples for GC-MS measurement of 5α-cholestanol

The GC-MS analysis method for measurement of elevated plasma 5α-cholestanol was modified from a published method (33). In brief, internal standard (epicoprostanol) was added to plasma or DBS samples or to calibrants generated using 5α-cholestanol. Sterols were saponified by the addition of ethanol/KOH, incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and then the aqueous phase was extracted twice with hexane. The combined hexane extracts were evaporated and derivatized with BSTFA at 80°C for 30 min. Concentrations of the trimethylsilyl ether derivatives of 5α-cholestanol were measured using GC (pulsed/splitless injection with an Agilent GC 6890N) performed with a ZB1701 column (30m, 0.25 mm ID, 0.25 µm film thickness; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) coupled to a mass spectrometer (MS 5975; Santa Clara, CA). Mass spectra were collected in selected ion mode (with m/z 355 and 370 ions monitored for epicoprostanol, and m/z 306 and 305 ions monitored for 5α-cholestanol).

Preparation of calibrators and samples for LC-MS/MS measurement of ketosterols

For the LC-ESI-MS/MS method, calibrators were generated using dilutions of authentic standard in methanol. The dilutions were spiked into DCS plasma or pooled whole blood from unaffected individuals (which was used to create DBS by pipetting 100 μl aliquots onto filter paper and air drying for 1 h). For calibrators or samples, 300 pg 7αC4-d7 internal standard in 10 μl methanol was added to either 4 μl plasma or 3.2 mm DBS punches followed by 80 μl QAO reagent solution (210 μg in methanol plus 5% acetic acid, v/v). The mixture was vortexed and kept at room temperature for 2 h, at which point QAO derivatization was complete (<2% underivatized ketosterol could be detected by LC-ESI-MS/MS). Ten microliters of water and 300 pg of previously prepared QAO-d3 7αC4 and QAO-d3 7α12αC4 internal standards in 10 μl methanol were added. Prior to LC-MS/MS analysis, any precipitate was removed using Ultrafree 0.45 μm centrifugal filters from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

Preparation of QAO-d3 7αC4 and QAO-d3 7α12αC4 internal standards

7αC4 and 7α12αC4 were tagged with isotopically enriched QAO reagent to prepare internal standards by derivatization of 30 ng of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 using 942 μl QAO-d3 reagent (2.8 mg/ml) in methanol at 5% acetic acid. This reaction was kept at room temperature for 18 h; the underivatized ketosterols were monitored to ensure greater than 98% derivatization. This mixture was frozen without purification, and aliquots of QAO-d3-tagged ketosterol internal standards were directly added to plasma and DBS samples after 2 h of derivatization with QAO-d0 reagent.

LC-ESI-MS/MS optimization

LC-ESI-MS/MS experiments were performed, and the method was validated using a QTRAP® 5500 triple-quadrupole hybrid mass spectrometer with linear ion trap functionality (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA), equipped with a TurboIonSpray® ESI source. The ionization interface was operated in the positive mode using the following settings: TEM 500°C, IS 5.0 kV; and CUR, GS2, and GS1 nitrogen gas flow rates, 40, 40, and 30 psi, respectively. For QAO derivatives and underivatized ketosterols, the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions monitored for quantification were as follows (all at EP 10 V with dwell times of 40 ms): for QAO 7αC4, m/z 515.7→152.3 quantifier (CE 65eV, DP 71eV, and CXP 4eV) and m/z 515.7→438.6 qualifier (CE 65eV, DP 76eV and CXP 6eV); for QAO 7α12αC4, m/z 531.7→152.1 qualifier (CE 65eV, DP 71eV, and CXP 4eV), and m/z 531.7→454.5 qualifier (CE 65eV, DP 76eV, and CXP 6eV); for QAO 7αC4-d7, m/z 522.7→152.2 (CE 70eV, DP 71eV, and CXP 8eV); for QAO-d3 7αC4, m/z 518.7→152.3 (with CE 70eV, DP 85eV, and CXP 8eV); and for QAO-d3 7α12αC4, m/z 534.7→152.1 (CE 65eV, DP 71eV, and CXP 4eV). For underivatized 7αC4 (monitored to ensure complete derivatization), the MRM transition was m/z 401.6→97.2 (CE 50eV, DP 71eV, and CXP 8eV). The QTRAP® 5500 was coupled to a Shimadzu UPLC system (Columbia, MD) composed of a SIL-20ACXR auto-sampler and two LC-20ADXR LC pumps. QAO derivatives of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 were resolved using a 50 × 2.1(i.d.) mm, 5.0 μm Luna C8-HPLC column with guard (Phenomenex; Torrance, CA). The gradient mobile phase was delivered at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The mobile phase consisted of two solvents: A, water:acetonitrile (98:2 v/v) at 0.1% formic acid, and B, water:acetonitrile (10:90 v/v) at 0.1% formic acid. Solvent B was increased from 10% to 60% over 2 min, kept at 60% for 1 min, then increased from 60% to 100% over 0.2 min. The column was washed at 100% B for 1.8 min, decreased to 10% B over 0.1 min, and reequilibrated at 10% B for 1.4 min. The column temperature was kept at 35°C using a Shimadzu CTO-20AC column oven. The sample injection volume was 10 μl.

Data analysis

To calculate analyte concentrations, calibration curves were generated by performing a least-squares linear regression for peak area ratios (QAO-d0 7αC4 analyte/QAO-d0 7αC4-d7 internal standard or QAO-d3 7αC4 internal standard and QAO-d0 7α12αC4 analyte/QAO-d3 7α12αC4 internal standard) plotted against specified calibrant concentration in plasma (ng/ml). The analyte and internal standard peaks were integrated as previously described (32).

Method performance

The LLOQ was determined as the lowest spiked concentration in the matrix for which the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio was greater than 5 and the reproducibility of calculated concentrations was less than or equal to 20% relative standard deviation (RSD). Within-day reproducibility was determined using calculated concentrations for quality control (QC) samples generated by spiking 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 into DCS plasma or whole blood spotted onto filter paper. Between-day reproducibility was determined using calculated concentrations for QCs analyzed on different days. Potential method interference was carefully evaluated by examination of the peak shape, peak shoulder, and peak area ratio of two MRM transitions (quantifier and qualifier) acquired for each analyte (34). The selectivity of the method was also evaluated by analysis of possible method interference by, for example, endogenous regioisomers of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4, such as 7-ketocholesterol (Steraloids) and 3β,27-dihydroxy-5-cholesten-7-one (Avanti, Alabaster, AL). Carryover from the auto-sampler was determined by assessing carryover from a 2,500 ng/ml sample. The extraction efficiency of 7α12αC4 from filter paper was determined by comparing the QAO 7α12αC4 peak area for ketosterol calibrators spotted onto filter paper against calibrators not spotted onto filter paper. The matrix effect was determined in two ways: by comparing the QAO ketosterol peak area for matrix-based calibrators against nonmatrix calibrators and by using the post-column infusion method (35). The stability of QAO-tagged ketosterols in matrix stored at −20°C or −80°C for 1 week and at room temperature or at 4°C for 8 h was assessed.

RESULTS

LC-ESI-MS/MS method

The QAO reagent introduces a trimethyl ammonium-charged moiety that couples to the ketosterol ketone functionality via oxime bond formation (32) (see derivative structures in Fig. 2). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation of the [M]+ ions for QAO derivatives produces dominant [M-59]+ product ions from the neutral loss (NL) of trimethylamine, as well as [M-59-18]+ product ions from the NL of trimethylamine and water, and product ions at m/z 152.2 composed of part of ring A of the ketosterol and part of the QAO moiety (32). MS2 spectra for QAO-tagged ketosterols are provided in supplementary Fig. I. The m/z 152.2 product ions are unique in that they result from both the structure of the QAO reagent and the ketosterol molecule. This type of specific fragment usually results in improved MRM method selectivity and reduced background noise (32). Reconstructed ion chromatograms (RICs) for QAO-tagged 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 possess low background noise, improving the S/N ratio and lowering limit of detection (LOD) values. The signal enhancement factor for QAO derivatization over Girard P derivatization was at least 2- to 3-fold, and over nonderivatization, it was approximately 20- to 30-fold (see supplementary Fig. I). The LODs for QAO-tagged ketosterols under these conditions (based on S/N ratio of 3:1) were 0.5–1.0 pg on-column injection.

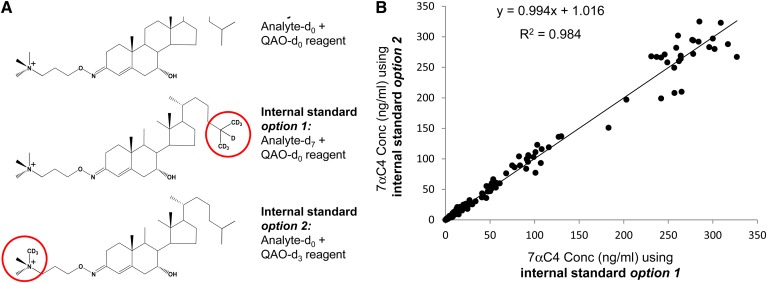

Fig. 2.

A: Upper structure is QAO-d0-tagged 7aC4-d0 analyte, middle structure is QAO-d0-tagged 7aC4-d7 internal standard (option 1), and lower structure is QAO-d3-tagged 7aC4-d0 internal standard (option 2). B: Comparison of plasma concentrations of 7αC4 calculated using either QAO-d0-tagged 7αC4-d7 or QAO-d3-tagged 7αC4-d0 internal standard (option 1 versus option 2).

Comparison of quantification using commercially available ketosterol-dx analog as internal standard versus quantification using QAO-dx-tagged ketosterol as internal standard

DCS plasma calibration curves for QAO-tagged 7αC4 analyte with QAO-tagged 7αC4-d7 internal standard demonstrated acceptable linearity and a mean correlation coefficient r2 = 0.992 across the range 10–250 ng/ml (n = 6). From the concentrations calculated for 10, 20, 50, and 250 ng/ml QCs, the LLOQ for 7αC4 in plasma was determined to be 20 ng/ml and the upper limit of quantification 250 ng/ml (accuracy and precision data not shown).

The availability of isotopically enriched derivatization reagent allowed the ready preparation of QAO-d3-tagged ketosterols as internal standards for isotope dilution quantification. To validate use of QAO-d3-tagged ketosterol as an internal standard, DCS plasma calibration curves were generated for QAO-d0-tagged 7αC4 with QAO-d3-tagged 7αC4 internal standard (acceptable linearity and characteristic correlation coefficients r2 > 0.990, data not shown). The accuracy and precision data for 7αC4 concentrations calculated using QAO-d3-tagged 7αC4 internal standard (Table 1) was comparable to the data using QAO-tagged 7αC4-d7 internal standard. A comparison of calculated 7αC4 concentrations was performed for n = 200 plasma samples, QCs, and calibrators using either QAO-d0-tagged 7αC4-d7 or QAO-d3-tagged 7αC4-d0 as internal standard (options I and 2, respectively, in Fig. 2A). The calculated 7αC4 concentrations demonstrated acceptable correlation (r2 = 0.984; Fig. 2B).

TABLE 1.

Accuracy and precision data for calculated ketosterol concentrations in plasma and DBS

| Ketosterol | Nominal Concentration(ng/ml) | Calculated Concentration (ng/ml) | Accuracy (%) | RSD (%) | Calculated Concentration (ng/ml) | Accuracy (%) | RSD (%) | On-column Injection (pg) |

| Within-run (n = 3) plasma | Between-run (n = 6) plasma | |||||||

| 7αC4 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 94.6 | 52.9 | 8.7a | 87.8a | 26.7a | 3.8 |

| 20.0b | 17.7 | 88.7 | 12.0 | 18.1 | 90.4 | 13.0c | 7.7b | |

| 50.0 | 53.0 | 106 | 10.9 | 47.9 | 95.8 | 9.9 | 19.2 | |

| 250 | 247 | 98.9 | 1.7 | 252 | 101 | 1.3 | 96.2 | |

| 7α12αC4 | 10.0 | 8.5 | 84.7 | 37.6 | 9.1a | 90.7a | 27.7a | 3.8 |

| 20.0b | 17.0 | 84.8 | 4.7 | 19.6 | 97.9 | 5.3 | 7.7b | |

| 50.0 | 51.6 | 103 | 11.2 | 45.6 | 91.1 | 10.4 | 19.2 | |

| 250 | 261 | 105 | 2.1 | 253 | 101 | 1.8 | 96.2 | |

| Within-run (n = 3) DBS | Between-run (n = 4) DBS | |||||||

| 7α12αC4 | 20 | 25.0 | 125 | 23.3 | 18.9c | 94.3c | 26.8c | 7.7 |

| 50bd | 48.4 | 96.7 | 3.3 | 47.0 | 94.0 | 10.4 | 19.2bd | |

| 100 | 88.9 | 88.9 | 3.0 | 101 | 101 | 9.6 | 38.5 | |

| 250 | 250 | 99.8 | 5.3 | 251c | 100c | 1.2c | 96.2 | |

Accuracy and precision data generated using QAO-d3-tagged ketosterol-d0 internal standard spiked at 75 ng/ml.

n = 3.

LLOQ.

n = 5.

Approximate value based on an estimate of 4 μl whole blood volume.

After validating the use of QAO-d3-tagged ketosterol as internal standard, we prepared QAO-d3-tagged 7α12αC4 internal standard. DCS plasma calibration curves for QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 with QAO-d3-tagged 7α12αC4 internal standard demonstrated acceptable linearity (mean correlation coefficient across the plasma range 20–250 ng/ml of r2 = 0.997; n = 6). The LLOQ determined for 7α12αC4 in plasma was 20 ng/ml (for accuracy and precision data, see Table 1).

A DBS calibration curve for 7αC4 could not be generated as method interference precluded measurement of 7αC4 in DBS. DBS calibration curves for QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 with QAO-d3-tagged 7α12αC4 internal standard demonstrated acceptable linearity and a mean correlation coefficient of r2 = 0.997 across the range 50–250 ng/ml (n = 5; for accuracy and precision data, see Table 1).

LC-ESI-MS/MS method performance studies

Selectivity.

For measurement of 7αC4 in plasma, a mean peak area ratio for quantifier and qualifier MRM transitions was obtained with a RSD of 14% (for n = 120 samples and calibrants ≥ 20 ng/ml, with <5% not within ± 2 SD), and for 7α12αC4 in plasma, a mean peak area ratio was obtained with a RSD of 10% (for n = 120 samples and calibrants ≥ 20 ng/ml, with <1% not within ± 2 SD). Method interference precluded measurement of 7αC4 in whole-blood spotted onto filter paper. An interfering peak was extracted from filter paper (detected with both qualifier and quantifier MRM transitions) that coeluted with 7αC4 even under shallower gradient or isocratic HPLC elution. The interfering peak was extracted from Protein Saver 903, as well as Whatman DMPK A and DMPK B filter paper (data not shown). For measurement of 7α12αC4 in DBS, a mean peak area ratio for quantifier and qualifier MRM transitions was obtained with a RSD of 7.5% (for n = 70 samples and calibrants ≥ 20 ng/ml; with <4% not within ± 2 SD). The selectivity of the method was also evaluated by analysis of endogenous regioisomers of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 reported to be present: 7-ketocholesterol and 3β,27-dihydroxy-5-cholesten-7-one. These ketosterols (at 100 ng/ml) were derivatized and analyzed using the LC-ESI-MS/MS method to ensure they did not coelute with QAO-tagged 7αC4 or 7α12αC4. Between injection carryover for 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 from the auto-sampler was assessed and determined to be <0.1%.

Extraction efficiency.

The extraction efficiency of 7α12αC4 from filter paper was determined by comparing the QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 peak area for calibrators spotted onto filter paper and derivatized against calibrators not spotted onto filter paper. The mean extraction efficiency of 7α12αC4 from filter paper across the range 20-250 ng/ml was 92%.

Matrix effect.

The matrix effect was determined by comparing the QAO-tagged ketosterol peak area for matrix-based against nonmatrix calibrators and by the post-column infusion method (35) where a solution of QAO-tagged ketosterol (0.1 ng/ml in methanol) was continuously infused into the ESI source while a QAO-derivatized blank DCS plasma or DBS sample was analyzed. Signal suppression was estimated by observing the loss in signal for infused QAO-tagged ketosterols at their respective elution times. The mean signal suppression from four experiments due to matrix interference from plasma was calculated to be 29% (21% RSD) for QAO-tagged 7αC4 and 36% (21% RSD) for QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 across the range 20–250 ng/ml. The signal suppression calculated due to matrix interference from DBS was 21% (15% RSD) for QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 across the range 20–250 ng/ml.

Stability studies.

Ketosterols spiked into DCS plasma (7αC4 and 7α12αC4) and DBS (7α12αC4) over the calibration curve range were stable when stored at −20°C and −80°C for 1 week at room temperature and at 4°C for 8 h (a comparison of absolute peak area, as well as peak area ratio of analyte to internal standard demonstrated each condition differed from a mean value at time zero by less than 10%). It was previously reported that 7αC4 was stable in plasma stored at −20°C for up to 10 months (30). QAO derivatives in aqueous quenched derivatization solvent were stable kept in the auto-sampler for 24 h at room temperature (exhibiting a loss in absolute peak area but differing from a mean value at time zero by less than 5%). Methanol dilutions of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 were stable at −80°C for at least 1 year (21).

Quantification of endogenous ketosterols as a blood test for CTX

RICs for detection of QAO-tagged ketosterols illustrate detection of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4, respectively (Fig. 3A, B), in plasma from unaffected and CTX-affected adults. CTX adult plasma samples with concentrations greater than 250 ng/ml were diluted 25-fold and reanalyzed. The mean plasma concentrations of 7αC4, 7α12αC4, and 5α-cholestanol measured in CTX-affected adults were, respectively, 183-, 3862-, and 24-fold the mean concentrations in unaffected adults, with no overlap between the concentrations found in CTX-affected and unaffected adults (Table 2).

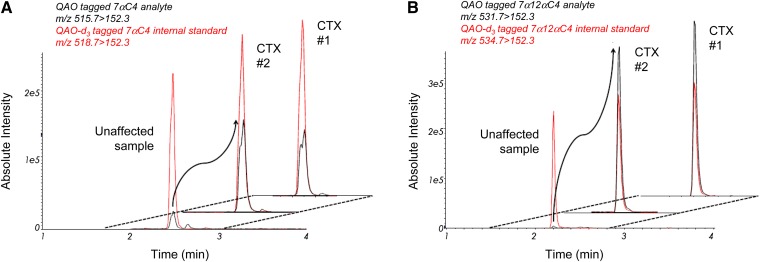

Fig. 3.

7αC4 and 7α12αC4 in unaffected and CTX-affected adult plasma samples A: Offset RICs for MRM detection of QAO-tagged 7αC4 and QAO-d3-tagged 7αC4 internal standard (black and red traces, respectively) in representative unaffected and CTX-affected samples (n = 2). QAO-tagged 7αC4 is a split peak (syn and anti conformers) eluting at 2.4 min. B: RICs for detection of QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 and QAO-d3-tagged 7α12αC4 internal standard (black and red traces, respectively) in representative unaffected and CTX-affected samples (n = 2). The CTX plasma was diluted 25-fold prior to analysis.

TABLE 2.

7αC4 and 7α12αC4 as improved markers for CTX in plasma and DBS

| 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-onea (ng/ml) | 7α12α-dihydroxy-4-cholesten-3-onea (ng/ml) | 5α-cholestanolb (μg/ml) | |

| Untreated CTX-affected adult plasma (n = 10) | 1174 ± 711 c [204–1828] | 1545 ± 1144 c [57–2420] | 31 ± 19 [8.4–66] |

| Unaffected adult plasma (n = 20) | 6.4 ± 5.3d [1.6–22] | 0.4 ± 0.27d [0.1–0.8] | 1.3 [0.8–1.8] |

| Untreated CTX-affected adult DBS (n = 4) | ND | 1385 ± 467d [852–1990] | 17.4 ± 6.5 [6.8–24.4] |

| Unaffected adult DBS (n = 3) | ND | 1.0 ± 1.3d [0–2.5] | 2.3 ± 0.9 [1.4–3.8]e |

| Untreated CTX-affected newborn DBS (n = 2) | ND | [120–214]f | [8.4–8.7]f |

| Unaffected newborn DBS (n = 4) | ND | 16.4 ± 6.0dg [12.3–26.3] | 4.7 ± 1.8 [2.5–7.0] |

Mean concentration ± SD where possible and [range of results] are given. ND, not determined (due to method interference).

Nonhydrolyzed sterol; quantification based on area ratio of QAO ketosterol to QAO-d3 ketosterol internal standard.

Hydrolyzed sterol; quantification by GC-MS.

These samples were diluted 25-fold and reanalyzed.

Calculated outside the quantifiable range.

n = 6.

Range for two samples.

n = 6.

The concentration of 7α12αC4 in adult DBS was similar to concentrations found in plasma, with highly disparate concentrations observed between unaffected and CTX-affected adult samples (see Table 2 and Fig. 4A). Despite calculated 7α12αC4 concentrations outside the measurable range, the mean concentration of 7α12αC4 in CTX-affected adult DBS was 1385-fold the mean concentration in unaffected adult DBS, with no overlap between the concentrations in CTX-affected and unaffected adult samples (Table 2). In contrast, the mean DBS concentration of 5α-cholestanol measured by GC-MS in CTX-affected adults was only 7.6-fold the mean concentration in unaffected adults.

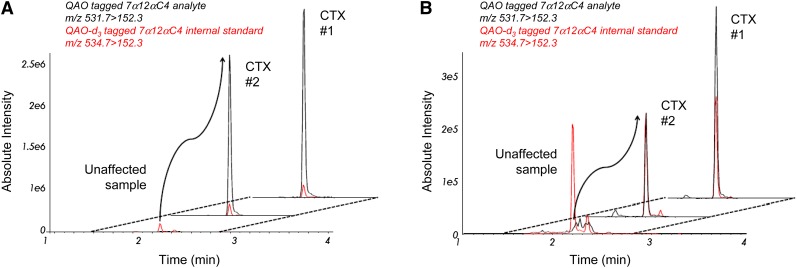

Fig. 4.

7α12αC4 in unaffected and CTX-affected adult and newborn DBS Both panels are offset RICs for MRM detection of QAO-tagged 7α12αC4 and QAO-d3-tagged 7α12αC4 internal standard (black and red traces, respectively) in representative unaffected and CTX-affected samples (n = 2). A: Data for unaffected and affected adult DBS. B: Data for unaffected and affected newborn DBS.

Through significant effort and collaboration, we were able to obtain two newborn DBS samples from individuals diagnosed with CTX later in life (between 5 and 15 years old). Although the DBS had been stored at room temperature for between 15 and 25 years, we were able to measure elevated 7α12αC4 in both samples (120–214 ng/ml). While the CTX (asymptomatic) newborn DBS concentrations of 7α12αC4 were around 10-fold lower than the mean CTX (symptomatic) adult DBS concentration, they were 10-fold greater than the mean unaffected newborn DBS 7α12αC4 concentration (Table 2 and Fig. 4B), with no overlap between concentrations in affected and unaffected DBS. In contrast, the CTX newborn DBS concentrations of 5α-cholestanol were only around 2-fold the mean 5α-cholestanol concentration in unaffected newborn DBS, with some overlap between the 5α-cholestanol concentrations in unaffected newborns and affected adult DBS.

DISCUSSION

Due to the poor ionization efficiency of neutral sterols, derivatization to incorporate an ionizable moiety or permanent charge has been utilized to improve sensitivity for ESI or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS/MS sterol detection. We previously explored Girard P derivatization of ketosterols, such as 7αC4, to form hydrazones (21). This methodology was limited by an LLOQ of 50–100 ng/ml (close to the maximum circulating concentration of 7αC4) (29). The keto moiety of sterols or steroids has also been derivatized with aminooxy reagents to form oxime derivatives, for example, using hydroxylamine or QAO reagent (32). A higher equilibrium constant for oxime over hydrazone formation results in improved room temperature stability for oxime derivatives. In addition, fragmentation of QAO derivatives can produce unique fragments that result in lower background noise (32). We report here that LC-ESI-MS/MS methodology utilizing QAO derivatization, with simple and rapid sample preparation amenable to automation and analysis times of 4–6 min using conventional LC instrumentation and buffers, enabled sensitive isotope dilution quantification of ketosterol BA precursors and allowed characterization of their utility as markers for CTX compared with 5α-cholestanol.

The acidic BA pathway initiated by cholesterol 27-hydroxylation (lower pathway in Fig. 1) has been proposed to be the major BA synthesis pathway in neonates, as deficiency in the oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase enzyme (CYP7B1) can cause severe liver disease in infancy (36–38). Our data and the recent observation that CYP7B1 mutations also cause a form of hereditary spastic paraplegia with disease onset outside of the newborn period (39) suggest that when the acidic pathway is blocked, neonates are able to synthesize BA via the neutral pathway. This hypothesis is also supported by clinical observations in CTX. Generally affected newborns survive the newborn period and serious complications of the disorder present later in life. Some cholic acid is likely formed in CTX newborns via diversion of the neutral BA pathway through bile alcohols (in CTX adults, cholic acid can be synthesized through bile alcohols formed from 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α-triol by microsomal 25- followed by 24- or 23-hydroxylation; see Fig. 1). Elevated bile alcohol intermediate 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α,25-tetrol was previously detected in serum from a four-month-old CTX patient (1).

There are concerns regarding the specificity of 5α-cholestanol as a marker for CTX as it can be elevated in other disorders (for example, sitosterolemia and liver disease) (40). Although 7αC4 can also be elevated in BA malabsorption and ileal resection (41), we previously reported that 7αC4 demonstrated improved utility over 5α-cholestanol as a circulating marker for CTX (21). Studies are under way in our laboratory to determine whether 7α12αC4 is a more specific marker for CTX than 7αC4. The data we present here, that the mean circulating concentration of 7α12αC4 in CTX-affected individuals is 3,862-fold the mean control concentration, suggests 7α12αC4 may be a more unique marker for CTX. Bjorkhem and colleagues reported that in CTX hepatic tissue elevation of 7α12αC4 over control values was greater than elevation of 7αC4, as well as downstream 7α12αC4 derivatives formed in the pathway to bile alcohols, such as 7α,12α-dihydroxy-5β-cholestan-3-one and 5β-cholestane-3α,7α,12α-triol (25).

In summary, we describe here LC-ESI-MS/MS methodology that utilizes keto-moiety derivatization with QAO reagent to enable highly sensitive isotope dilution quantification of 7αC4 and 7α12αC4 in plasma or DBS from CTX-affected adults and newborns. Quantification of 7α12αC4 provides improved discrimination between CTX and unaffected samples compared with 5α-cholestanol, such that it serves as an improved blood test for CTX. Although accumulation of ketosterol BA precursors has been previously reported in affected adults and adolescents (1, 25, 26), we demonstrate for the first time that elevated 7α12αC4 can be measured in DBS obtained from affected newborns. With the limitation that we were able to retrieve and analyze only two DBS from individuals with adolescent onset disease, there appears to be no overlap between concentrations of 7α12αC4 in affected and unaffected samples, thus potentially enabling the screening of newborn DBS for CTX.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cheryl Hermerath and Mike Skeels at the Northwest Regional Newborn Screening Program, Pranesh Chakraborty at the Ontario Screening Program, Fred Lorey at the California Newborn Screening Program for providing access to stored DBS, and the Bioanalytical Shared Resource at OHSU for providing technical assistance and access to analytical instrumentation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- 7α12αC4

- 7α,12α-dihydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one

- 7αC4

- 7α-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one

- BA

- bile acid

- CDCA

- chenodeoxycholic acid

- CID

- collision-induced dissociation

- CTX

- cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis

- DBS

- dried blood spot

- DCS

- double charcoal stripped

- FAB

- fast atom bombardment

- LLOQ

- lower limit of quantification

- LOD

- limit of detection

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- NL

- neutral loss

- QAO

- quaternary amonoxy

- QC

- quality control

- RIC

- reconstructed ion chromatogram

- RSD

- relative standard deviation

- S/N

- signal-to-noise

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants KL2-TR-000152 and 1U54-HD-061939, and by seed funding from the Friends of Doernbecher and United Leukodystrophy Foundations (A.E.D.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one figure.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clayton P. T., Verrips A., Sistermans E., Mann A., Mieli-Vergani G., Wevers R. 2002. Mutations in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene (CYP27A) cause hepatitis of infancy as well as cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 25: 501–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Bahr S., Bjorkhem I., van't Hooft H. F., Alvelius G., Nemeth A., Sjovall J., Fischler B. 2005. Mutation in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene associated with fatal cholestasis in infancy. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 40: 481–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verrips A., van Engelen B. G., Wevers R. A., van Geel B. M., Cruysberg J. R., van den Heuvel L. P., Keyser A., Gabreels F. J. 2000. Presence of diarrhea and absence of tendon xanthomas in patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Arch. Neurol. 57: 520–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verrips A., Hoefsloot L. H., Steenbergen G. C., Theelen J. P., Wevers R. A., Gabreels F. J., van Engelen B. G., van den Heuvel L. P. 2000. Clinical and molecular genetic characteristics of patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Brain. 123: 908–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pilo-de-la-Fuente B., Jimenez-Escrig A., Lorenzo J.R., Pardo J., Arias M., Ares-Luque A., Duarte J., Muniz-Perez S., Sobrido M. J. 2011. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Spain: clinical, prognostic, and genetic survey. Eur. J. Neurol. 18: 1203–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorincz M. T., Rainier S., Thomas D., Fink J. K. 2005. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: possible higher prevalence than previously recognized. Arch. Neurol. 62: 1459–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falik-Zaccai T. C., Kfir N., Frenkel P., Cohen C., Tanus M., Mandel H., Shihab S., Morkos S., Aaref S., Summar M. L., et al. 2008. Population screening in a Druze community: the challenge and the reward. Genet. Med. 10: 903–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leitersdorf E., Safadi R., Meiner V., Reshef A., Bjorkhem I., Friedlander Y., Morkos S., Berginer V. M. 1994. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in the Israeli Druze: molecular genetics and phenotypic characteristics. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 55: 907–915 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallus G. N., Dotti M. T., Mignarri A., Rufa A., Da P. P., Cardaioli E., Federico A. 2010. Four novel CYP27A1 mutations in seven Italian patients with CTX. Eur. J. Neurol. 17: 1259–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondelli M., Sicurelli F., Scarpini C., Dotti M. T., Federico A. 2001. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: 11-year treatment with chenodeoxycholic acid in five patients. An electrophysiological study. J. Neurol. Sci. 190: 29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuriyama M., Fujiyama J., Yoshidome H., Takenaga S., Matsumuro K., Kasama T., Fukuda K., Kuramoto T., Hoshita T., Seyama Y., et al. 1991. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: clinical and biochemical evaluation of eight patients and review of the literature. J. Neurol. Sci. 102: 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berginer V. M., Salen G., Shefer S. 1984. Long-term treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with chenodeoxycholic acid. N. Engl. J. Med. 311: 1649–1652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierre G., Setchell K., Blyth J., Preece M. A., Chakrapani A., McKiernan P. 2008. Prospective treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis with cholic acid therapy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 31(Suppl. 2): S241–S245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berginer V. M., Gross B., Morad K., Kfir N., Morkos S., Aaref S., Falik-Zaccai T. C. 2009. Chronic diarrhea and juvenile cataracts: think cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis and treat. Pediatrics. 123: 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federico A., Dotti M. T., Gallus G. N. 2003. Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. In GeneReviews [Internet]. R. A. Pagon, M. P. Adam, T. D. Bird, et al., editors. University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salen G. 1971. Cholestanol deposition in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. A possible mechanism. Ann. Intern. Med. 75: 843–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leitersdorf E., Reshef A., Meiner V., Levitzki R., Schwartz S. P., Dann E. J., Berkman N., Cali J. J., Klapholz L., Berginner V. M. 1993. Frameshift and splice-junction mutations in the sterol 27-hydroxylase gene cause cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis in Jews or Moroccan origin. J. Clin. Invest. 91: 2488–2496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egestad B., Pettersson P., Skrede S., Sjovall J. 1985. Fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry in the diagnosis of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 45: 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitt J. J. 2007. High-throughput urine screening for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome and cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis using negative electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chim. Acta. 380: 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas D., Gan-Schreier H., Langhans C. D., Rohrer T., Engelmann G., Heverin M., Russell D. W., Clayton P. T., Hoffmann G. F., Okun J. G. 2012. Differential diagnosis in patients with suspected bile acid synthesis defects. World J. Gastroenterol. 18: 1067–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBarber A. E., Connor W. E., Pappu A. S., Merkens L. S., Steiner R. D. 2010. ESI-MS/MS quantification of 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one facilitates rapid, convenient diagnostic testing for cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 411: 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeBarber A. E., Sandlers Y., Pappu A. S., Merkens L. S., Duell P. B., Lear S. R., Erickson S. K., Steiner R. D. 2011. Profiling sterols in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: utility of Girard derivatization and high resolution exact mass LC-ESI-MS(n) analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 879: 1384–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shackleton C. H., Chuang H., Kim J., de la Torre X., Segura J. 1997. Electrospray mass spectrometry of testosterone esters: potential for use in doping control. Steroids. 62: 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths W. J., Wang Y., Alvelius G., Liu S., Bodin K., Sjovall J. 2006. Analysis of oxysterols by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 17: 341–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjorkhem I., Oftebro H., Skrede S., Pederson J. I. 1981. Assay of intermediates in bile acid biosynthesis using isotope dilution-mass spectrometry: hepatic levels in the normal state and in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J. Lipid Res. 22: 191–200 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda A., Salen G., Matsuzaki Y., Batta A. K., Xu G., Leitersdorf E., Tint G. S., Erickson S. K., Tanaka N., Shefer S. 2001. Differences in hepatic levels of intermediates in bile acid biosynthesis between Cyp27(−/−) mice and CTX. J. Lipid Res. 42: 291–300 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skrede S., Bjorkhem I., Buchmann M. S., Hopen G., Fausa O. 1985. A novel pathway for biosynthesis of cholestanol with 7 alpha-hydroxylated C27-steroids as intermediates, and its importance for the accumulation of cholestanol in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J. Clin. Invest. 75: 448–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjorkhem I., Skrede S., Buchmann M. S., East C., Grundy S. 1987. Accumulation of 7 alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one and cholesta-4,6-dien-3-one in patients with cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis: effect of treatment with chenodeoxycholic acid. Hepatology. 7: 266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honda A., Yamashita K., Numazawa M., Ikegami T., Doy M., Matsuzaki Y., Miyazaki H. 2007. Highly sensitive quantification of 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one in human serum by LC-ESI-MS/MS. J. Lipid Res. 48: 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galman C., Arvidsson I., Angelin B., Rudling M. 2003. Monitoring hepatic cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase activity by assay of the stable bile acid intermediate 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one in peripheral blood. J. Lipid Res. 44: 859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovgren-Sandblom A., Heverin M., Larsson H., Lundstrom E., Wahren J., Diczfalusy U., Bjorkhem I. 2007. Novel LC-MS/MS method for assay of 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one in human plasma. Evidence for a significant extrahepatic metabolism. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 856: 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Star-Weinstock M., Williamson B. L., Dey S., Pillai S., Purkayastha S. 2012. LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of testosterone at sub-picogram levels using a novel derivatization reagent. Anal. Chem. 84: 9310–9317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merkens L. S., Jordan J. M., Penfield J. A., Lutjohann D., Connor W. E., Steiner R. D. 2009. Plasma plant sterol levels do not reflect cholesterol absorption in children with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. J. Pediatr. 154: 557–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kushnir M. M., Rockwood A. L., Nelson G. J., Yue B., Urry F. M. 2005. Assessing analytical specificity in quantitative analysis using tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Biochem. 38: 319–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Annesley T. M. 2003. Ion suppression in mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 49: 1041–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setchell K. D., Schwarz M., O'Connell N. C., Lund E. G., Davis D. L., Lathe R., Thompson H. R., Weslie T. R., Sokol R. J., Russell D. W. 1998. Identification of a new inborn error in bile acid synthesis: mutation of the oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene causes severe neonatal liver disease. J. Clin. Invest. 102: 1690–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueki I., Kimura A., Nishiyori A., Chen H. L., Takei H., Nittono H., Kurosawa T. 2008. Neonatal cholestatic liver disease in an Asian patient with a homozygous mutation in the oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 46: 465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizuochi T., Kimura A., Suzuki M., Ueki I., Takei H., Nittono H., Kakiuchi T., Shigeta T., Sakamoto S., Fukuda A., et al. 2011. Successful heterozygous living donor liver transplantation for an oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase deficiency in a Japanese patient. Liver Transpl. 17: 1059–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsaousidou M. K., Ouahchi K., Warner T. T., Yang Y., Simpson M. A., Laing N. G., Wilkinson P. A., Madrid R. E., Patel H., Hentati F., et al. 2008. Sequence alterations within CYP7B1 implicate defective cholesterol homeostasis in motor-neuron degeneration. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82: 510–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koopman B. J., van der Molen J. C., Wolthers B. G., de Jager A. E. J., Waterreus R. J., Gips C. H. 1984. Capillary gas chromatographic determination of cholestanol/cholesterol ratio in biological fluids. Its potential usefulness for the follow-up of some liver diseases and its lack of specificity in diagnosing CTX (cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis). Clin. Chim. Acta. 137: 305–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camilleri M., Nadeau A., Tremaine W. J., Lamsam J., Burton D., Odunsi S., Sweetser S., Singh R. 2009. Measurement of serum 7alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one (or 7alphaC4), a surrogate test for bile acid malabsorption in health, ileal disease and irritable bowel syndrome using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 21: 734–e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.