Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that the ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC)A1 and ABCG1 function in many aspects of cholesterol efflux from macrophages. In this current study, we continued our investigation of extracellular cholesterol microdomains that form during enrichment of macrophages with cholesterol. Human monocyte-derived macrophages and mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, differentiated with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) or granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulation factor (GM-CSF), were incubated with acetylated LDL (AcLDL) to allow for cholesterol enrichment and processing. We utilized an anti-cholesterol microdomain monoclonal antibody to reveal pools of unesterified cholesterol, which were found both in the extracellular matrix and associated with the cell surface, that we show function in reverse cholesterol transport. Coincubation of AcLDL with 50 μg/ml apoA-I eliminated all extracellular and cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains, while coincubation with the same concentration of HDL only removed extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol microdomains. Only at an HDL concentration of 200 µg/ml did HDL eliminate the cholesterol microdomains that were cell-surface associated. The deposition of cholesterol microdomains was inhibited by probucol, but it was increased by the liver X receptor (LXR) agonist TO901317, which upregulates ABCA1 and ABCG1. Extracellular cholesterol microdomains did not develop when ABCG1-deficient mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were enriched with cholesterol. Our findings show that generation of extracellular cholesterol microdomains is mediated by ABCG1 and that reverse cholesterol transport occurs not only at the cell surface but also within the extracellular space.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein A-I, high density lipoprotein, probucol, macrophages

Macrophage cholesterol homeostasis is important to the understanding and study of atherosclerosis. It has been suggested that excess cholesterol accumulation is cytotoxic to macrophages (1, 2), which contributes to the theory that atherosclerotic plaques progress when a macrophage's mechanisms for cholesterol removal become overwhelmed, thus leading to excess cholesterol accumulation (3). Reverse cholesterol transport represents one important pathway for cellular cholesterol removal, and many molecular factors have been implicated in its mediation (4–7).

One such group of molecules is the ATP-binding cassette transporter family. The ABC transporter proteins mediate the unidirectional transport of a variety of substrates across the plasma membrane and other cellular membranes. ABCA1-mediated phospholipidation of apoA-I is a necessary step in order for apoA-I to be able to solubilize cholesterol (8). However, there is still much debate about the function of ABCG1. ABCG1 was initially identified as one of the most highly activated genes in macrophages heavily enriched with sterols (9). In vitro studies clearly demonstrate that expression of the ABCG1 gene stimulates cholesterol efflux (10–13), but they also indicate that ABCG1 shows little specificity for any cholesterol acceptor. In fact, HDL, LDL, and phospholipid vesicles all serve as excellent cholesterol acceptors mediating ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux (10–12, 14, 15). Considering the wide arrange of acceptors, it has been proposed that ABCG1 does not directly transfer cholesterol to an acceptor but, rather, mobilizes cholesterol to the plasma membrane where it can be incorporated with a cholesterol acceptor (11).

Many cell types are found in atherosclerotic plaques, which in turn create local regions with complex cytokine profiles. Monocytes migrating to these regions of the vessel wall will be influenced by the local cytokine environment. In a previous study (16), we observed two macrophage cell types with differing antigen expression profiles, CD68+/CD14+ and CD68+/CD14−, within human atherosclerotic plaques. These two macrophage cell types resemble in morphology and antigen expression human monocyte-derived macrophages that are differentiated in vitro in fetal bovine serum with M-CSF or GM-CSF, respectively (16). M-CSF-differentiated macrophages are elongated, while GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages are rounded (16, 17). The presence of different macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerotic plaques dictates that these different macrophage phenotypes should be studied in vitro when attempting to learn about macrophage cholesterol metabolism. In this regard, we have observed differences in the generation of cell-surface associated and extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol microdomains when various cell types are enriched with cholesterol (18, 19).

In earlier research, we detected these cholesterol microdomains with monoclonal antibody (mAb) 58B1, which labels ordered arrays of unesterified cholesterol molecules in monolayers and cholesterol crystals rather than individual cholesterol molecules (20–22). Cholesterol labeling can be eliminated by treatment of fixed cells with cholesterol oxidase or cyclodextrin, an agent that binds and removes cholesterol from cholesterol-containing structures (18). The antibody does not detect cholesteryl ester (20). We have used this antibody to label cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains in cultured human skin fibroblasts and human monocyte-derived macrophages differentiated with human serum (18), a culture condition producing a phenotype characterized by a rounded shape similar to human monocytes cultured in fetal bovine serum containing GM-CSF (16, 23). Only following cholesterol enrichment of fibroblasts in the presence of an inhibitor of cholesterol esterification do cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains in these cells become detectable with mAb 58B1 (18). This presumably occurs because some of the buildup of cellular unesterified cholesterol localizes to the plasma membrane in preparation for cellular cholesterol efflux. The cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains do not form in mutant Niemann-Pick Type C (NPC) fibroblasts, whose mutated Niemann-Pick Type C protein leads to aberrant cholesterol trafficking and trapping of unesterified cholesterol within lysosomes (24, 25). Likewise, ketoconazole, an agent that inhibits transport of cholesterol from lysosomes to the cell surface (26), blocks the development of cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains induced by cholesterol enrichment in the presence of a cholesterol esterification inhibitor.

Following cholesterol enrichment of human serum-differentiated macrophages, although rare macrophages show cholesterol microdomains at the cell surface or within the extracellular matrix adjacent to the macrophage, most human serum-differentiated macrophages, similar to fibroblasts, show no labeling with mAb 58B1 unless cholesterol esterification is inhibited. In contrast to the cell types above, without requiring inhibition of cholesterol esterification, cholesterol-enrichment of human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages induces extensive cholesterol microdomains that are both cell surface-associated and present within the extracellular matrix (19). Previous findings suggest that unesterified cholesterol-rich microdomain deposition occurs through a two-step process in which macrophages first accumulate unesterified cholesterol in the form of cell surface microdomains. These cell surface microdomains are subsequently deposited onto the extracellular matrix through a mechanism requiring Src family kinase activity (19). Both cell surface-associated and extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol microdomains can be mobilized by cholesterol acceptors, such as HDL and apoA-I (18, 19). ApoA-I, but not HDL, requires the presence of living macrophages in order to effect mobilization of the cholesterol microdomains (19), most likely because of the requirement for apoA-I to be phospholipidated before it can function as a cholesterol acceptor (8).

In the current study, we have continued our investigation of the hypothesis that mAb 58B1-labeled cholesterol microdomains represent a pool of unesterified cholesterol that functions in reverse cholesterol transport, and we determined the molecular mediator for generation of the novel extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol microdomains. Here, we show that the generation of extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol microdomains in macrophages is ABCG1-dependent and that apoA-I mobilizes cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains more efficiently than does HDL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

RPMI-1640 was obtained from Mediatech (Herndon, VA); FBS and Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) with Ca2+ and Mg2+ were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); 6-well and 12-well CellBIND plates were obtained from Corning (Corning, NY); human M-CSF, human GM-CSF, human interleukin-10 (IL-10), mouse M-CSF and GM-CSF were obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ); acetylated LDL (AcLDL), and HDL were obtained from Intracel (Frederick, MD); apoA-I was obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA); TO901317 was obtained from Cayman Chemical (La Jolla, CA); Oil Red O, glycerol-gelatin mounting media, probucol, BSA, penicillin-streptomycin, L-glutamine, and Histopaque-1077 were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); mouse anti- (unesterified) cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 IgM in ascites was produced as previously described (20); mouse anti-Clavibacter michiganense mAb (clone 9A1) IgM in ascites was obtained from Agdia (Elkhart, IN); paraformaldehyde was obtained from Polysciences (Warrington, PA); biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgM, hematoxylin QS, and Vectashield hard set mounting medium with 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA); Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate was obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY).

Culture of human monocyte-derived macrophages

Mononuclear cells were obtained from human donors by monocytopheresis and subsequently purified using counterflow centrifugal elutriation as previously described (27). Monocytopheresis was carried out under a human subjects research protocol approved by a National Institutes of Health institutional review board. The resulting elutriated human monocytes were diluted in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and seeded on 6- or 12-well CellBIND plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/cm2. Cultures were incubated in a 37°C cell culture incubator with 5% CO2/95% air for 2 h, and subsequently rinsed three times with RPMI-1640 to remove nonadherent cells. The remaining adherent cells were then differentiated with RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 50 ng/ml M-CSF (human), and 25 ng/ml IL-10. As done previously, IL-10 was included because it enhances the growth and differentiation of human monocytes cultured in M-CSF and creates a more homogenous macrophage phenotype for study (28). Cultures were rinsed and replaced with fresh media on day 6. The resulting monocyte-derived macrophages were used for experiments on day 7.

Human GM-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages were cultured in a similar manner except that the adherent macrophages were differentiated with RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS and 50 ng/ml GM-CSF (human). These GM-CSF cultures were rinsed and replaced with fresh media on days 3, 6, and 13, and were used for experiments on day 14.

All experiments were carried out with the same medium used for differentiation except that serum was omitted.

Culture of mouse monocyte- and bone marrow-derived macrophages

Male C57BL/6 and ABCG1−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were generated as described previously (29). For culture of bone marrow-derived macrophages, femurs and tibias were isolated from mice and muscle were removed. Both ends of the bones were cut with scissors and then flushed with 5 ml of RMPI-1640 with a 25 gauge needle. Cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 nucleated bone marrow cells/cm2 in 12-well CellBIND plates containing 1.5 ml per well of RPMI-1640 plus 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 ng/ml GM-CSF (mouse) to generate GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages. After a 24 h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2/95% air, cells were rinsed three times with 1 ml RPMI-1640 to remove nonadherent cells, and then cultured further with 1.5 ml of RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 ng/ml GM-CSF. Cell culture medium was subsequently changed every three days with fresh medium as detailed above. After three weeks in culture, experiments were performed with serum-free RPMI-1640, 50 ng/ml GM-CSF, and the indicated additions. GM-CSF differentiation of mouse bone marrow-derived cells required three weeks to acquire a near-uniform culture of macrophages with rounded, heavily vacuolated morphology. Culture of M-CSF-differentiated macrophages was identical to the procedure for GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages, except that cells were incubated with 50 ng/ml M-CSF (mouse) instead of GM-CSF, and experiments were performed after one week of culture.

Monocyte-derived macrophages were obtained by collecting blood from the orbital sinus as previously described (30). Mononuclear cells were isolated from the blood using Histopaque-1077 density centrifugation medium following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Cells were seeded at a density of 4.2 × 105 cells/cm2 and cultured for two weeks with mouse M-CSF as described above.

Immunostaining of macrophages

Fixation, immunostaining, and microscopy were all performed with macrophages in their original CellBIND culture plates, and all steps were carried out at room temperature. Macrophage cultures were rinsed three times in DPBS, fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in DPBS, and then rinsed an additional three times in DPBS. Macrophages were then incubated 60 min with 5 µg/ml purified mouse anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 IgM diluted in DPBS containing 0.1% BSA. Control staining was performed with 5 µg/ml of an irrelevant purified mouse anti-Clavibacter michiganense mAb (clone 9A1) IgM diluted in DPBS containing 0.1% BSA. Cultures were then rinsed three times (5 min each) in DPBS, followed by a 30-min incubation in 5 µg/ml biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgM diluted in DPBS containing 0.1% BSA. After three rinses in DPBS (5 min each), cultures were incubated 10 min with 10 µg/ml Streptavidin Alex Fluor 488 diluted in DPBS. Cultures were then rinsed three times with DPBS and mounted in Vectashield hard-set mounting medium with DAPI nuclear stain in preparation for digital imaging using an Olympus IX81 fluorescence microscope. Because macrophages were not permeabilized, mAb 58B1 staining represents cell surface- or extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol labeling, the latter referred to as extracellular staining hereafter. No staining was observed when the control mAb was substituted for the anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb. The immunostained cells shown in figures are representative of a minimum of five microscopic fields viewed in one culture well.

Oil Red O staining of macrophages

Fixation, Oil Red O staining, and microscopy were all performed with macrophages in their original CellBIND culture plates, and all steps were carried out at room temperature. One-week-old human monocyte-derived macrophages were rinsed three times in DPBS, fixed for 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in DPBS, and then rinsed an additional three times in DPBS. Then, macrophages were stained 15 min at room temperature with 1 ml of filtered Oil Red O staining solution. Oil Red O staining solution was prepared by dissolving Oil Red O in isopropanol to obtain a 3% solution (w/v). Then, this Oil Red O-isopropanol solution was diluted by adding two parts water to three parts Oil Red O-isopropanol solution, and the resulting staining solution was filtered (0.45 µm pore size). After Oil Red O staining, macrophages were rinsed three times with water, stained 2 min with hematoxylin QS, rinsed with water, and then coverslipped with glycerol-gelatin mounting media.

Microscopic analysis

Cells were identified using phase-contrast microscopy, or by locating DAPI-stained nuclei. The pattern and intensity of mAb 58B1 staining were then analyzed for cultures from each experimental parameter, and these data were compared with one another. mAb 58B1-labeling was considered cellular if it was located within cell membrane boundaries, as identified on the corresponding phase-contrast view. Labeling was considered extracellular if it was located outside the cell membrane boundaries seen on phase-contrast view. Different planes of focus were visualized before acquiring images to confirm that only a monolayer of cells was present, thereby ensuring that labeling seen outside cell membrane boundaries did not represent cellular labeling from cells lying in a different plane of focus.

Quantification of macrophage cholesterol

After incubations, human monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were rinsed three times in DPBS. Macrophages were then harvested from wells by scraping into 1 ml distilled water. Thus, cholesterol measurements represent both macrophage- and extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol. Lipid was extracted from the resulting cell suspension using the Folch method (31), and quantities of esterified and unesterified cholesterol were determined using the method previously described by Gamble et al. (32). Protein quantification was performed on an aliquot of cell lysate using the Lowry method with BSA as a standard (33).

Analysis of 125I-AcLDL cell association and degradation

Macrophage uptake of 125I-AcLDL was assessed by measuring cell-associated and degraded 125I-AcLDL according to the method previously described by Goldstein et al. (34). A portion of culture media was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min, and trichloroacetic acid-soluble organic iodide radioactivity was measured to quantify lipoprotein degradation. Cell-associated 125I-AcLDL was assessed as follows. Macrophages were rinsed three times with DPBS containing 0.2% BSA, followed by three rinses with DPBS, all at 4°C. Macrophages were dissolved overnight in 0.1 M NaOH at 37°C, and then assayed for 125I radioactivity with a γ counter. 125I radioactivity values for wells incubated with 125I-AcLDL without macrophages were subtracted from 125I radioactivity values obtained for macrophages incubated with 125I-AcLDL. Values were less than 1% of cell-associated 125I-AcLDL. Protein quantification was performed on an aliquot of cell lysate using the Lowry method (33) with BSA as a standard. 125I-AcLDL uptake is presented as the sum of cell-associated 125I-AcLDL and degraded 125I-AcLDL.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Means were determined with three replicate wells. An unpaired, two-tailed Student t-test or one-way ANOVA was used for statistical comparisons as indicated. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Human M-CSF-differentiated macrophage cholesterol accumulation

Our previous study showed continuous increase in extracellular cholesterol microdomains generated by human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages over a two-day incubation (19). To follow the cholesterol enrichment process in macrophages incubated with AcLDL, we quantified esterified and unesterified cholesterol levels over a two-day incubation of human M-CSF-differentiated macrophage cell cultures with AcLDL (50 µg/ml). Serum was not included in the culture media at this point to eliminate any serum-mediated cholesterol efflux. Total and esterified cholesterol levels progressively increased during incubation with AcLDL. Compared with control macrophages incubated without AcLDL, human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages accumulated 426 nmol total cholesterol/mg cell protein after one day, and 756 nmol/mg after two days. As for esterified cholesterol, macrophages accumulated 100 nmol cholesterol/mg cell protein after one day and 370 nmol cholesterol/mg cell protein after two days. Unesterified cholesterol levels raised 325 nmol/mg cell protein after one day and 384 nmol/mg cell protein after two days (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Time course of macrophage cholesterol accumulation

| Condition | Cholesterol | Esterified Cholesterol | ||

| Total | Unesterified | Esterified | ||

| nmol/mg cell protein | % | |||

| No addition (one day) | 136 ± 16 | 136 ± 16 | 1 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 |

| AcLDL (one day) | 562 ± 23 | 461 ± 17 | 101 ± 6 | 18 ± 0 |

| No addition (two days) | 104 ± 2 | 104 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 | 1 ± 2 |

| AcLDL (two days) | 860 ± 75 | 488 ± 27 | 371 ± 51 | 43 ± 2 |

One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for one or two days without or with 50 µg/ml AcLDL. Then macrophage cultures were analyzed for their unesterified and esterified cholesterol contents.

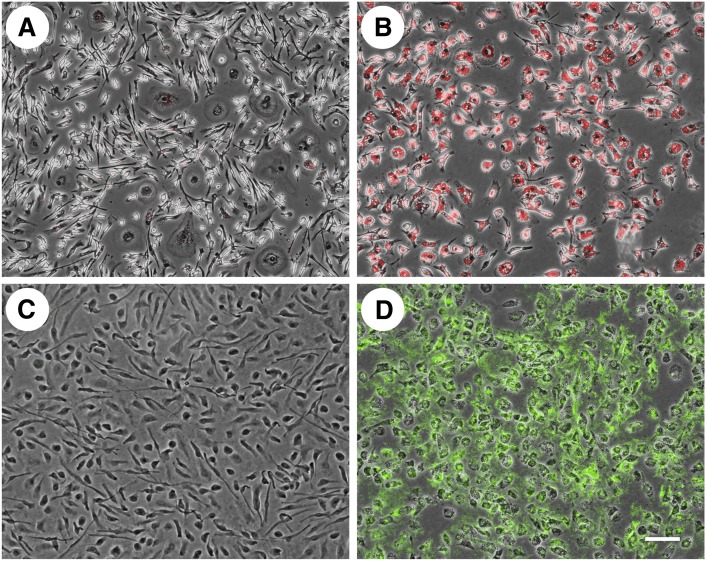

Extracellular cholesterol microdomains do not stain with Oil Red O

The continuous cycle of esterification and hydrolysis of cholesterol converts potentially toxic unesterified cholesterol to its neutral esterified form for storage, or converts cholesteryl esters into unesterified cholesterol for mobilization and efflux (35). On the other hand, some cell types such as hepatocytes and intestinal epithelia cells secrete cholesteryl ester as a component of typically apoB-containing lipoproteins. We wanted to see if the extracellular cholesterol microdomains generated by human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages showed any evidence that they contained esterified cholesterol, and thus could be derived from some type of macrophage-derived esterified cholesterol-containing lipoprotein. Cell cultures were incubated without or with AcLDL (50 µg/ml) for two days. Following fixation, macrophages were stained either with Oil Red O (Fig. 1A, B), which stains esterified cholesterol (and triglyceride), or with anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (Fig. 1C, D). Cholesterol-enrichment of macrophages caused generation of extracellular anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb staining as reported by us previously (Fig. 1D) (19). While the cholesterol-enriched macrophages stained bright red consistent with their accumulation of cholesteryl ester-rich lipid droplets, no Oil Red O staining was observed in the extracellular space (Fig. 1B), suggesting that if the cholesterol microdomains do contain esterified cholesterol, it is not in a form that can be stained with Oil Red O. Macrophages not incubated with AcLDL showed no staining with either Oil Red O (Fig. 1A) or anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Extracellular cholesterol microdomains do not stain with Oil Red O. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for two days without (A and C) or with 50 µg/ml AcLDL (B and D), fixed, and then stained with either Oil Red O (A and B) or anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (C and D). Macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy, and staining was visualized with fluorescence microscopy (red fluorescence for Oil Red O in A and B; green fluorescence for anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 in C and D). Fluorescence and phase-contrast images were superimposed to produce the images shown. Bar = 100 µm and applies to all.

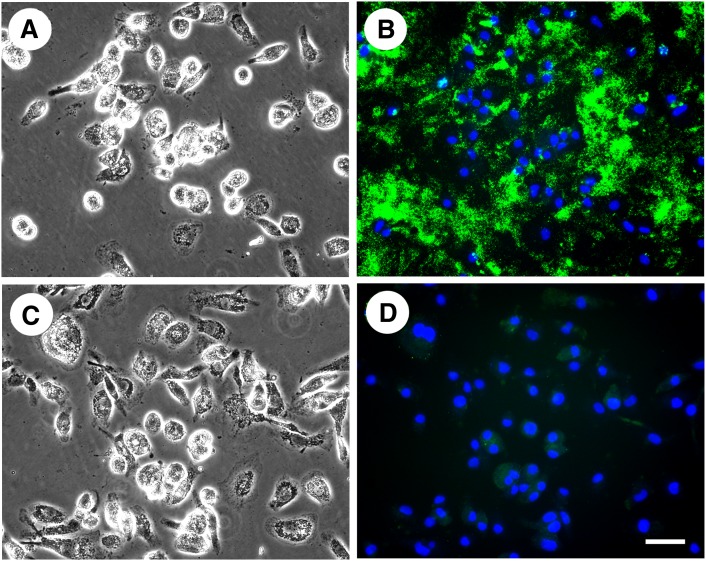

Extracellular cholesterol microdomains can be eliminated by cyclodextrin treatment

We next tested whether staining with anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 can be eliminated by treatment of cholesterol-enriched macrophages with methyl-β-cyclodextrin, an agent that complexes cholesterol and thus, can cause its efflux from cells (36). After cholesterol microdomains were generated in macrophages through cholesterol enrichment with AcLDL (50 µg/ml) for two days, the macrophages were treated 1 h either without or with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin added to RPMI-1640 media. Then, the macrophages were fixed and stained with anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1. Fig. 2 shows that methyl-β-cyclodextrin pretreatment completely eliminated anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 staining consistent with the cholesterol microdomain specificity of this antibody.

Fig. 2.

Methyl-β-cyclodextrin eliminates anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 staining. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for two days with 50 µg/ml AcLDL. Next, macrophage cultures were treated 1 h either without (A and B) or with 5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (C and D) added to RPMI-1640 media. Then, the macrophages were fixed and stained with anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1. In A and C macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B and D, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

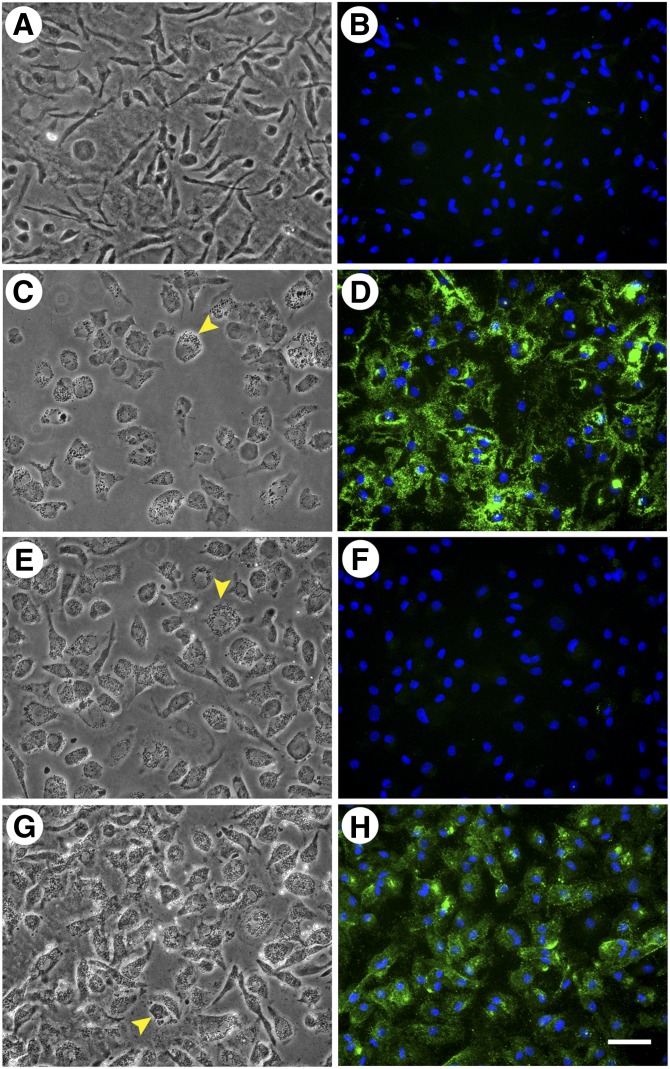

ApoA-I is a more efficient than HDL in mobilizing cell-associated cholesterol microdomains

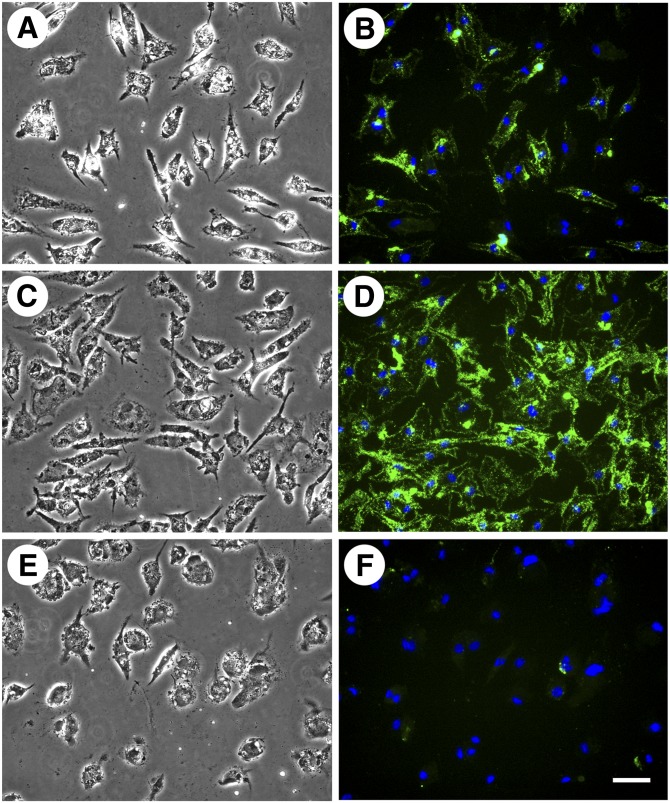

In our previous study, following macrophage cholesterol enrichment, incubation of macrophages with apoA-I or HDL resulted in decreased cell surface-associated and extracellular cholesterol microdomain staining. We wanted to determine if HDL or apoA-I would produce a similar result if incubated simultaneously with AcLDL during macrophage cholesterol enrichment. Thus, we incubated human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages for two days with AcLDL (50 µg/ml) both without and with a cholesterol acceptor, either 50 µg/ml HDL or 50 µg/ml apoA-I. Incubation with AcLDL generated cholesterol microdomains both at the cell surface, as well as in the extracellular space (Fig. 3C, D). No cholesterol microdomains were present without macrophage cholesterol enrichment with AcLDL (Fig. 3A, B). In addition, no cholesterol microdomains were observed when macrophages were incubated simultaneously with AcLDL and apoA-I (Fig. 3E, F). Inclusion of apoA-I even at a concentration as low as 12.5 µg/ml eliminated the cholesterol microdomains induced by AcLDL (data not shown). Incubation of macrophages simultaneously with AcLDL and HDL (50 µg/ml) eliminated cholesterol microdomains in the extracellular space, but did not eliminate the microdomains at the cell surface (Fig. 3G, H). Some of the microdomains that remained at the cell surface were large intense green staining regions in contrast to smaller green staining punctated cell-surface regions. However, we could not determine whether these different staining patterns were due to a lack of resolution by fluorescence microscopy of densely packed small green staining microdomains.

Fig. 3.

ApoA-I is more efficient than HDL in eliminating cholesterol microdomains. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for two days without (A and B) or with 50 µg/ml AcLDL (C and D). Additional wells were incubated for two days with 50 µg/ml AcLDL in the presence of either 50 µg/ml apoA-I (E and F) or 50 µg/ml HDL (G and H). In A, C, E, and G, macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B, D, F, and H, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. At the concentration tested, both HDL and apoA-I eliminated extracellular cholesterol microdomains, but only apoA-I eliminated cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. Arrowheads indicate lipid droplets within the macrophages. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

Neither apoA-I nor HDL prevented macrophage accumulation of lipid droplets (observed in Fig. 3C, E, G) induced during incubation of macrophages with AcLDL. The effect of apoA-I to eliminate all cholesterol microdomains, while HDL only prevented the generation of the extracellular cholesterol microdomains was surprising. Because the presence of HDL during macrophage cholesterol enrichment did not eliminate cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomain generation, we tested whether increasing HDL concentration could eliminate these cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. We incubated human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages for two days with AcLDL, and varying concentrations of HDL (0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/ml) (50 and 100 μg/ml are not shown) (Fig. 4). At an HDL concentration of 25 μg/ml, extracellular cholesterol microdomains were eliminated, but cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains remained (Fig. 4C, D). Only at an HDL concentration of 200 μg/ml were cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains eliminated (Fig. 4E, F). Taken together, these results suggest that apoA-I is more efficient than HDL at either preventing the generation of or mobilizing cholesterol from those cholesterol microdomains that are cell surface-associated.

Fig. 4.

Only high levels of HDL eliminate cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for two days with 50 µg/ml AcLDL in the absence (A and B) or presence of 25 µg/ml HDL (C and D) or 200 µg/ml HDL (E and F). In A, C, and E, macrophages were visualized using phase- contrast microscopy. In B, D, and F, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. HDL eliminated extracellular cholesterol microdomains at a concentration of 25 µg/ml, but it did not eliminate cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains until a concentration of 200 µg/ml HDL was reached. Bar = 100 µm and applies to all.

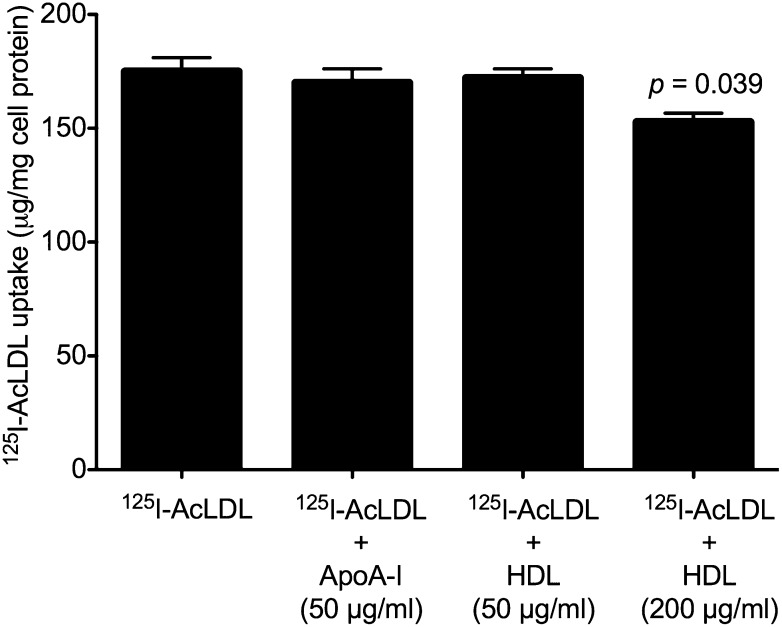

To ensure that the presence of neither HDL nor apoA-I affected AcLDL uptake and therefore cholesterol enrichment, we incubated human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages with 125I-AcLDL alone, or 125I-AcLDL with either 50 µg/ml apoA-I, 50 µg/ml HDL, or 200 µg/ml HDL. 125I-AcLDL uptake was not significantly affected by the presence of 50 µg/ml apoA-I or 50 µg/ml HDL. The addition of 200 µg/ml HDL significantly but only slightly decreased 125I-AcLDL uptake by 13% (Fig. 5). Thus, decreased uptake of 125I-AcLDL cannot explain the absence of cholesterol microdomains when macrophages were cholesterol-enriched in the presence of HDL or apoA-I. Cholesterol enrichment occurred with all incubations with AcLDL regardless of whether apoA-I or HDL were present (supplementary Fig. I). However, ApoA-I and HDL did decrease macrophage cholesterol accumulation induced by AcLDL, with apoA-I decreasing cholesterol accumulation greater than HDL.

Fig. 5.

ApoA-I and HDL do not substantially affect AcLDL uptake. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for two days with 50 µg/ml 125I-AcLDL without or with 50 µg/ml apoA-I, 50 µg/ml HDL, or 200 µg/ml HDL, after which total 125I-AcLDL uptake (i.e., sum of cell-associated and degraded 125I-AcLDL) was determined. Only incubation with 200 µg/ml HDL showed a slight (13%) decrease in 125I-AcLDL uptake. Statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) was determined using the Student t-test.

TO901317 increases and probucol decreases development of extracellular cholesterol microdomains

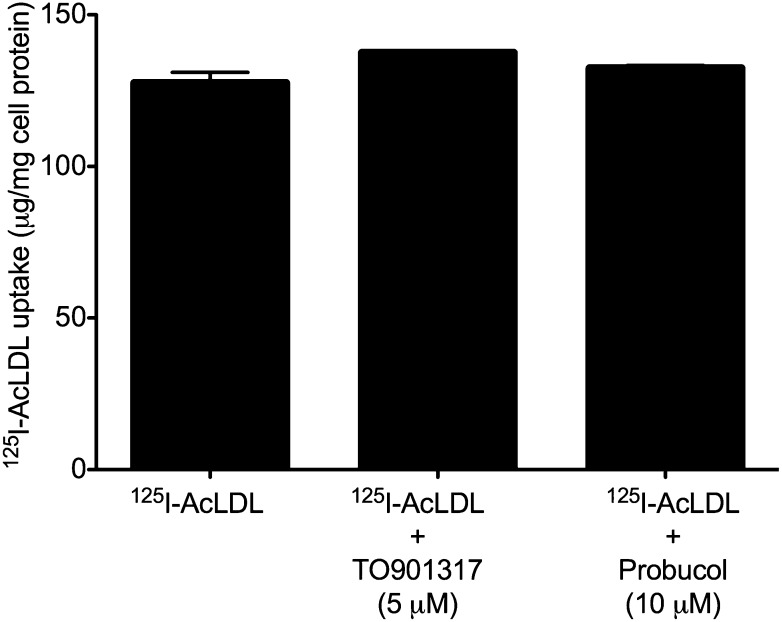

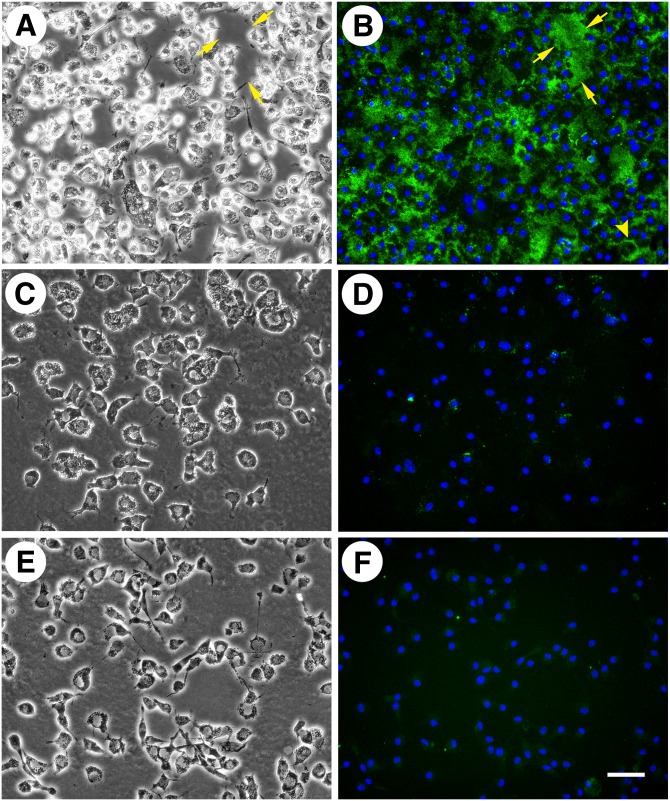

Previous studies have shown that LXR activation, such as by the drug TO901317, increases cholesterol efflux, in part through the up-regulation of ABC transporter proteins such as ABCA1 and ABCG1 (37). Probucol, an anti-hyperlipidemic drug, inhibits ABCA1 (38, 39), but no studies have shown conclusively whether probucol can inhibit other members of the ABC transporter protein family, such as ABCG1. We therefore hypothesized that if ABC transporter proteins functioned in generation of cholesterol microdomains, then TO901317 would increase the rate of cholesterol microdomain generation, while probucol could potentially inhibit cholesterol microdomain generation. To test these ideas, we incubated human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages for one day with AcLDL (50 µg/ml) without and with 10 µM probucol or 5 µM TO901317. During the one-day incubation with AcLDL, most but not all macrophages generated cholesterol microdomains, which were typically associated with the cell surface (Fig. 6A, B). However, the addition of TO901317 increased the amount of the cholesterol microdomains (extracellular and cell surface-associated) so that almost all macrophages showed intense labeling with the anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 mAb (Fig. 6C, D). In contrast, addition of probucol inhibited most of the cholesterol microdomain generation (Fig. 6E, F). To ensure that the presence of neither probucol nor TO901317 affected AcLDL uptake, we performed an analysis of 125I-AcLDL uptake. Neither probucol nor TO901317 affected 125I-AcLDL uptake (Fig. 7). Further, neither probucol nor TO901317 affected macrophage cholesterol accumulation induced by AcLDL (supplementary Fig. II).

Fig. 6.

TO901317 increases and probucol diminishes the generation of extracellular cholesterol microdomains. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for one day with 50 µg/ml AcLDL without drug (A and B), with 5 µM TO901317 (C and D), or with 10 µM probucol (E and F). In A, C, and E, macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B, D, and F, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

Fig. 7.

Probucol and TO901317 do not affect AcLDL uptake. One-week-old human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for one day with 50 µg/ml 125I-AcLDL without or with either 10 µM probucol or 5 µM TO901317, after which total 125I-AcLDL uptake (i.e., sum of cell-associated and degraded 125I-AcLDL) was determined. There were no significant differences (P ≤ 0.05) using the Student t-test.

Induction of cholesterol microdomains in human GM-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages

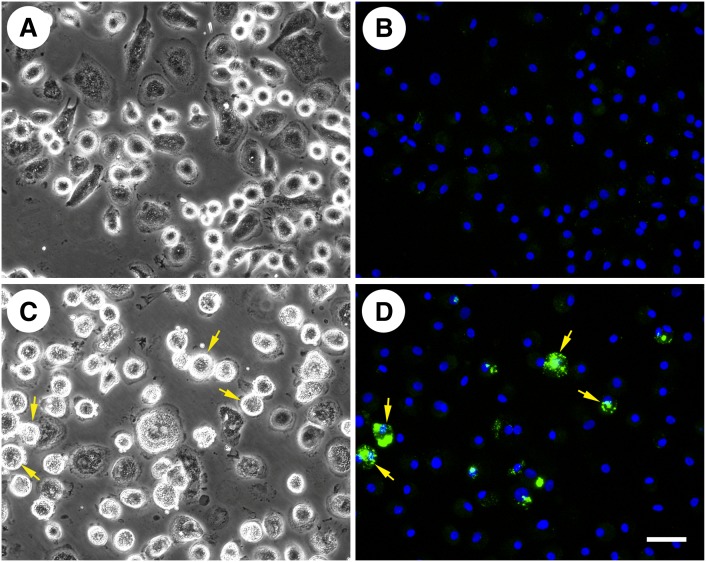

We attempted to induce cholesterol microdomains in human GM-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages by two-day incubation with 50 µg/ml AcLDL, similar to the incubation condition that induces cholesterol microdomains in human M-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages. Subsequent staining with mAb 58B1 revealed only minimal generation of cholesterol microdomains (data not shown). We therefore increased the incubation time with AcLDL to 5 days. With the increased incubation time, only a few GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages generated cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains (Fig. 8C, D), while control macrophages incubated without AcLDL showed no staining (Fig. 8A, B).

Fig. 8.

Human GM-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophages produce some cholesterol microdomains. One-week-old human GM-CSF-differentiated, monocyte-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for 5 days without (A and B) or with 50 µg/ml AcLDL (C and D) to generate cholesterol microdomains. In A and C, macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B and D, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. The arrows point to some examples of macrophages showing anti-cholesterol mAb 58B1 staining. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

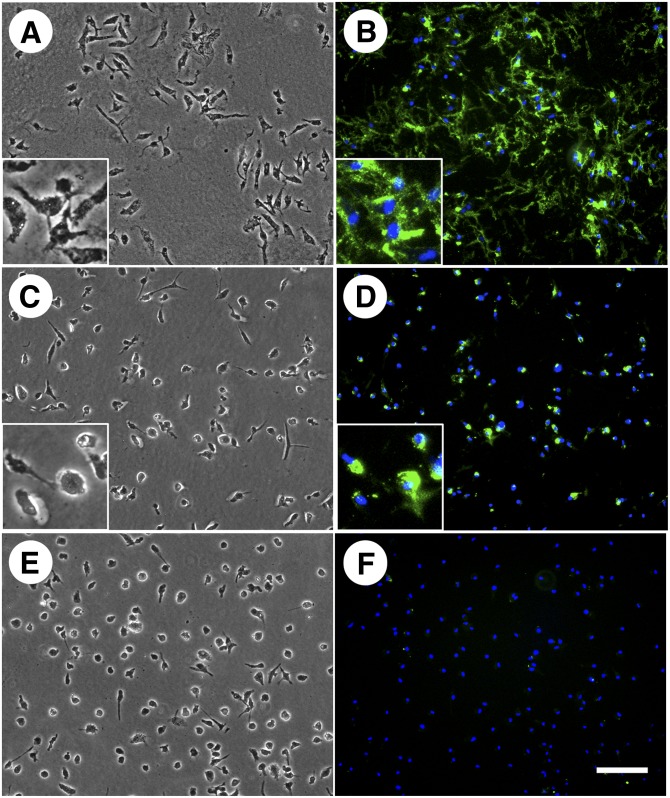

Cholesterol microdomain generation is ABCG1-dependent

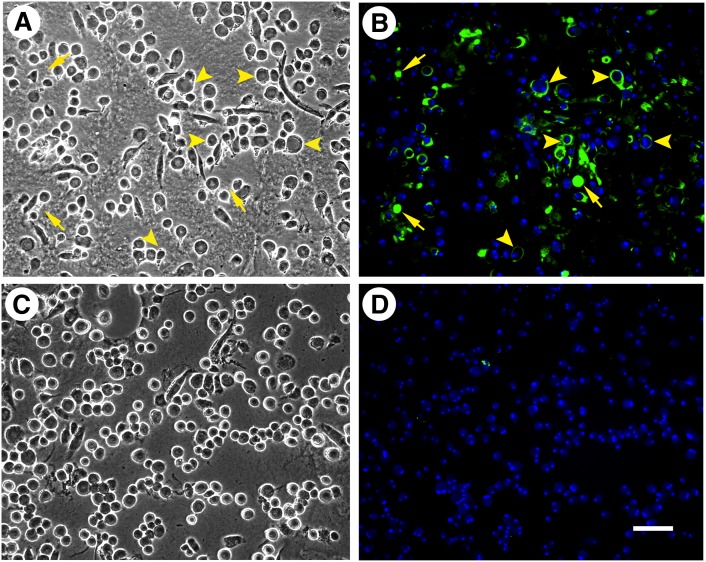

Our earlier and current findings indicate that apoA-I and HDL can mobilize cholesterol from both the cell surface-associated and extracellular cholesterol microdomains. Mobilization by apoA-I requires the presence of macrophages, while HDL-mediated cholesterol microdomain mobilization does not (19). Because HDL-mediated macrophage cholesterol efflux depends on ABCG1 but not on ABCA1, our findings suggested that ABCG1 might be functioning to generate the cholesterol microdomains. To test this possibility, we examined cholesterol microdomain generation in bone marrow-derived macrophages cultured from wild-type and ABCG1−/− mice. When incubated with AcLDL, C57BL/6 mouse macrophages differentiated with either mouse M-CSF or GM-CSF produced extracellular cholesterol microdomains that labeled with the mAb 58B1 monoclonal antibody. Wild-type mouse M-CSF-differentiated macrophages incubated with AcLDL generated mostly extracellular but only some rare cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains (Fig. 9A, B). Similar to what we observed for human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages, probucol greatly diminished cholesterol microdomains in the wild-type mouse M-CSF-differentiated macrophages incubated with AcLDL (Fig. 9C, D).

Fig. 9.

ABCG1 is necessary for mouse M-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived macrophage generation of cholesterol microdomains. One-week-old mouse wild-type (A–D) and ABCG1−/− (E, F) bone-marrow-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for 5 days with 50 µg/ml AcLDL. In C and D, 10 µM probucol was added to the incubation. In A, C, and E, macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B, D, and F, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. Probucol decreased generation of extracellular cholesterol microdomains by wild-type macrophages incubated with AcLDL. ABCG1−/− mice incubated with AcLDL did not generate extracellular cholesterol microdomains. Arrows indicate extracellular cholesterol microdomains, and arrowheads indicate cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

Mouse macrophages cultured from monocytes showed a similar pattern of mainly extracellular cholesterol microdomain labeling (supplementary Fig. III); albeit far fewer macrophages showed extracellular staining. Thus, the mouse M-CSF-differentiated macrophages regardless of origin from blood or bone marrow showed similar predominant extracellular cholesterol microdomain labeling, but were different from human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages that showed not only extracellular but also cell-associated cholesterol microdomain labeling. When enriched with cholesterol, the wild-type mouse GM-CSF-differentiated macrophage phenotype produced an extracellular staining pattern with anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 different from the staining pattern observed with M-CSF-differentiated macrophages. A halo-like staining pattern surrounding the GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages was observed (arrowheads in Fig. 10A, B). However, these cholesterol microdomains were not intrinsically part of the plasma membrane because anti-cholesterol staining persisted even where macrophages apparently had detached from the culture surface leaving behind cholesterol microdomain staining. In these cases, the halo pattern of staining was replaced by spherical areas of staining revealing cholesterol microdomains that accumulated between the bottom surface of the macrophage and the culture dish (arrows in Fig. 10A, B). Similar to mouse M-CSF-differentiated macrophages, no cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains were visualized with mouse GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages.

Fig. 10.

ABCG1 is necessary for mouse GM-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived macrophage generation of cholesterol microdomains. Three-week-old mouse wild-type (A and B) and ABCG1−/− (C and D) GM-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived macrophage cultures were incubated for 5 days with 50 µg/ml AcLDL to generate cholesterol microdomains. In A and C, macrophages were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy. In B and D, cholesterol microdomains were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using anti-cholesterol microdomain mAb 58B1 (green), and nuclei were imaged with DAPI fluorescence staining (blue). Left- and right-hand columns are corresponding microscopic fields. In contrast to wild-type mice, ABCG1−/− mice did not generate cholesterol microdomains. Arrowheads indicate macrophages with a halo-like pattern of staining. Arrows indicate a spherical pattern of staining that was revealed where macrophages had detached from the culture dish. Bar = 50 µm and applies to all.

In contrast to the cholesterol microdomains that developed when wild-type mouse macrophages were enriched with cholesterol, no cholesterol microdomains developed in mouse ABCG1−/− macrophages when these macrophages were enriched with cholesterol (Figs. 9E, F and 10C, D). This result was not due to decreased uptake of AcLDL by ABCG1−/− macrophages, because M-CSF-differentiated wild-type and ABCG1−/− macrophages took up similar amounts of 125I-AcLDL, and GM-CSF-differentiated ABCG1−/− macrophages took up about twice as much 125I-AcLDL as GM-CSF-differentiated wild-type macrophages (data not shown). Moreover, substantial cholesterol enrichment occurred in both wild-type and ABCG1−/− mouse macrophages (Table 2). Taken together, these results show that the ABCG1 transporter was necessary for the generation of the cholesterol microdomains in both macrophage phenotypes.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of cholesterol accumulation by wild-type and ABCG1−/− mouse macrophages

| Condition | Cholesterol | Esterified Cholesterol | ||

| Total | Unesterified | Esterified | ||

| nmol/mg cell protein | % | |||

| No addition (WT) | 59 ± 1 | 55 ± 2 | 4 ± 2 | 6 ± 4 |

| AcLDL (WT) | 392 ± 5 | 60 ± 2 | 331 ± 7 | 85 ± 1 |

| No addition (ABCG1−/−) | 66 ± 2 | 56 ± 1 | 10 ± 3 | 14 ± 4 |

| AcLDL (ABCG1−/−) | 353 ± 17 | 60 ± 5 | 293 ± 13 | 83 ± 1 |

One-week-old mouse wild-type and ABCG1−/− M-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived macrophage cultures were incubated two days without or with 50 µg/ml AcLDL. Then macrophage cultures were analyzed for their unesterified and esterified cholesterol contents. There were no significant differences in total cholesterol accumulation between the two macrophage phenotypes using the Student t-test.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have focused on cholesterol efflux due to HDL mobilization of cholesterol from the plasma membrane of cells such as macrophages. In our studies (18, 19), we have shown that in addition to cell surface-associated cholesterol, extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol is a novel cholesterol pool functioning in reverse cholesterol transport. Both cell surface-associated and extracellular matrix-associated pools of cholesterol are visualized with anti-cholesterol microdomain Mab58B1 under conditions of macrophage enrichment with cholesterol. Importantly, extracellular matrix-associated cholesterol domains can be detected with Mab58B1 in human atherosclerotic plaques (19). Vaughan and Oram (11, 40) described both ABCG1- and ABCA1-mediated development of cellular cholesterol microdomains that were accessible to cholesterol oxidase, and thus, these cholesterol microdomains were presumably located in the plasma membrane. However, our finding of macrophage deposition of cholesterol into the extracellular matrix shows that cholesterol susceptibility to cholesterol-oxidase should not be assumed to localize cholesterol to the plasma membrane, but alternatively could be cholesterol that has deposited within the extracellular matrix.

Mouse GM-CSF-differentiated and M-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived macrophages showed very different patterns of extracellular cholesterol microdomains. All the cholesterol microdomains generated by GM-CSF-differentiated macrophages were closely associated with the macrophage cell surface underlying macrophages, while the opposite was the case for M-CSF-differentiated macrophages where most cholesterol microdomains were dispersed throughout the adjacent extracellular matrix. The reason for these cell type differences is not clear but could reflect an effect of differences in amount and composition of extracellular matrix production on cholesterol microdomain trafficking. Burgess et al. (41) have described that J774 mouse macrophages show a lipid-containing binding site for apoA-I that underlies these cultured macrophages. It will be of interest in future studies to determine whether cholesterol microdomains colocalize with these apoA-I binding sites.

The extracellular cholesterol microdomains did not stain with Oil Red O indicating that the microdomains do not contain appreciable amounts of neutral lipid such as cholesteryl ester or triglyceride. This is consistent with the specificity of the antibody for unesterified cholesterol rather than cholesteryl ester (20), and the fact that macrophages typically excrete unesterified rather than esterified cholesterol (42). Previous experiments using mAb 58B1 show that cholesterol microdomains in the extracellular matrix increase between day 1 and day 2 (19). Thus, macrophages clear their excess unesterified cholesterol both by cholesterol esterification with storage in lipid droplets (35), and removal to cholesterol microdomains within the extracellular matrix. Previous work from our lab has shown that the compound, SU6656, inhibits cholesterol microdomain deposition into the extracellular matrix, while inducing a concomitant increase in cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomain labeling (19). This is consistent with cholesterol microdomains forming at the cell surface and then being shed into the extracellular matrix by an active cell-dependent process. Such sequestration of cholesterol within the extracellular matrix may minimize the potential toxicity of cholesterol that might otherwise be physically associated with the plasma membrane.

We found that the ABC transporter protein ABCG1 was necessary for macrophage generation of extracellular cholesterol microdomains because the extracellular cholesterol microdomains did not develop when ABCG1−/− mouse macrophages were enriched with cholesterol. Consistent with this finding in ABCG1−/− mouse macrophages, the LXR agonist, TO901317, which upregulates ABCG1 (10, 12), increased generation of cholesterol microdomains in human M-CSF-differentiated macrophages. We could not evaluate the role of ABCG1 in generation of cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains because cholesterol-enrichment did not generate these microdomains in the mouse macrophages. In any case, our findings indicate that ABCG1 mediates efflux to cholesterol acceptors not only by processing cholesterol for efflux from the macrophage plasma membrane, but also for efflux of cholesterol deposited by macrophages into the extracellular matrix.

Our previous study showed that cholesterol microdomains generated by macrophages incubated with AcLDL for one day, were eliminated during a subsequent one day incubation with HDL or apoA-I, agents that mediate cholesterol efflux (19). This was somewhat different from the results we observed in our current study in which simultaneous incubation of macrophages with AcLDL and either HDL or apoA-I was employed. Under the present simultaneous incubation condition, macrophages may be continuously effluxing cholesterol processed from AcLDL. Thus, this simultaneous incubation condition could more readily saturate cholesterol efflux pathways and cholesterol acceptors. Consistent with this possibility, simultaneous incubation of macrophages with AcLDL and 50 µg/ml HDL eliminated extracellular cholesterol microdomains, but did not eliminate a pool of cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains that was relatively resistant to HDL removal. These cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains were eliminated when HDL concentration reached 200 µg/ml. In contrast, addition of apoA-I at a concentration as low as 12.5 µg/ml to incubations of macrophages with AcLDL eliminated development of both extracellular and cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains.

The findings above suggest that both apoA-I and HDL can efficiently mobilize extracellular cholesterol microdomains. However, compared with HDL, apoA-I more efficiently mobilizes cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. This idea is consistent with previous findings. ApoA-I added to macrophages generates nascent HDL discoidal particles (43). These nascent HDL discs are much more efficient acceptors of cholesterol than mature HDL (11, 44), and this could explain the difference we observed between HDL and apoA-I in the efficiency of mobilization of cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. Furthermore, it is possible that the cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains form from ABCA1 action because cholesterol efflux mediated by this ABC transporter is more efficient with apoA-I compared with HDL (10, 45–47).

Probucol inhibited generation of both extracellular and cell surface-associated cholesterol microdomains. While probucol is known to inhibit ABCA1 (38, 39), it is not known whether probucol can inhibit ABCG1. Thus, probucol inhibition of cholesterol microdomain generation could either be due to a direct effect on ABCG1, or be due to probucol inhibition of ABCA1 that facilitates formation of the cholesterol microdomains, a point we plan to examine in future studies.

Studies of reverse cholesterol transport have demonstrated synergism between ABCG1 and ABCA1 transporters in mediating cellular cholesterol efflux (13, 14, 48, 49). In contrast to ABCA1 that can mediate cholesterol efflux in the presence of apoA-I or other amphipathic apolipoproteins that become phospholipidated through ABCA1 action, ABCG1 can only mediate cholesterol efflux to phospholipid or apolipoproteins that have already associated with phospholipid such as occurs in HDL (10–12). ABCG1-generated extracellular cholesterol microdomains may be one source of cholesterol that ABCA1-generated HDL mobilizes.

We previously showed that apoA-I was not sufficient in the absence of macrophages (and hence ABCA1) to mobilize cholesterol from the extracellular cholesterol microdomains that we now show are formed by ABCG1 (19). The ineffectiveness of apoA-I is presumably because apoA-I requires ABCA1-mediated phospholipidation before it can mobilize cholesterol. Although extracellular cholesterol microdomains could be associated with phospholipid (ABCG1 mediates excretion of phospholipid in addition to cholesterol (50)), the phospholipid in the extracellular cholesterol microdomains may not be of suitable composition or physical form to associate with apoA-I, thus precluding mobilization of extracellular microdomain cholesterol by lipid-poor apoA-I. It is known that cholesterol added to phospholipid vesicles stabilizes the vesicles and inhibits their conversion by apoA-I into smaller discoidal particles (51). In a similar manner, the extracellular cholesterol microdomain-containing particles may not be susceptible to mobilization by lipid-poor apoA-I.

The function of ABCG1 in atherosclerosis development remains controversial. Although knockout and overexpression studies of ABCG1 demonstrate its function in efflux of cholesterol from cells, other studies have drawn conflicting conclusions as to whether ABCG1 function is atherogenic or anti-atherogenic (52). It is conceivable that in the absence of effective mobilization of extracellular cholesterol microdomains, the deposited extracellular cholesterol at some degree of accumulation becomes cytotoxic or functions as a chemotactic signal for additional macrophage influx, and thus contributes to the atherogenic process. If this were so, then probucol inhibition of extracellular cholesterol microdomains generation could explain why probucol can be anti-atherogenic even though it inhibits ABCA1-mediated HDL formation. On the other hand, as long as the ABCG1 deposited extracellular cholesterol pool can be effectively mobilized by ABCA1-generated HDL, the ABCG1 function that generates extracellular cholesterol deposition could be anti-atherogenic. This idea is consistent with the previous finding that ABCG1 is atherogenic in the absence of ABCA1 function (53, 54), and the known synergy between ABCG1 and ABCA1 in mediating cellular cholesterol efflux (13, 14, 48, 49).

ABCG1 has been implicated in intracellular cholesterol trafficking as well as efflux of cholesterol and certain cytotoxic oxysterols (55–57). We have now shown that ABCG1 functions in generation of the extracellular cholesterol microdomains by cholesterol-enriched foam cell macrophages. The extracellular cholesterol microdomains could serve dual functions. Extracellular cholesterol microdomains function in ABCG1-mediated cholesterol removal. Also, because, like certain oxysterols, excess unesterified cholesterol can be cytotoxic (1, 2), exportation of cholesterol microdomains represents another means by which cells maintain cholesterol homeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Transfusion Medicine, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, for providing elutriated monocytes.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AcLDL

- acetylated LDL

- GM-CSF

- granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IL-10

- interleukin-10

- LXR

- liver X receptor

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- M-CSF

- macrophage colony-stimulating factor

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of three figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tabas I. 2002. Consequences of cellular cholesterol accumulation: basic concepts and physiological implications. J. Clin. Invest. 110: 905–911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warner G. J., Stoudt G., Bamberger M., Johnson W. J., Rothblat G. H. 1995. Cell toxicity induced by inhibition of acyl coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase and accumulation of unesterified cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 5772–5778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruth H. S. 2001. Macrophage foam cells and atherosclerosis. Front. Biosci. 6: D429–D455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jessup W., Gelissen I. C., Gaus K., Kritharides L. 2006. Roles of ATP binding cassette transporters A1 and G1, scavenger receptor BI and membrane lipid domains in cholesterol export from macrophages. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17: 247–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcel Y. L., Ouimet M., Wang M. D. 2008. Regulation of cholesterol efflux from macrophages. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19: 455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tarling E. J., Edwards P. A. 2012. Dancing with the sterols: critical roles for ABCG1, ABCA1, miRNAs, and nuclear and cell surface receptors in controlling cellular sterol homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1821: 386–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenson R. S., Brewer H. B., Jr, Davidson W. S., Fayad Z. A., Fuster V., Goldstein J., Hellerstein M., Jiang X. C., Phillips M. C., Rader D. J., et al. 2012. Cholesterol efflux and atheroprotection: advancing the concept of reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation. 125: 1905–1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama S. 2005. Assembly of high density lipoprotein by the ABCA1/apolipoprotein pathway. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 16: 269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klucken J., Buchler C., Orso E., Kaminski W. E., Porsch-Ozcurumez M., Liebisch G., Kapinsky M., Diederich W., Drobnik W., Dean M., et al. 2000. ABCG1 (ABC8), the human homolog of the Drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97: 817–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy M. A., Barrera G. C., Nakamura K., Baldan A., Tarr P., Fishbein M. C., Frank J., Francone O. L., Edwards P. A. 2005. ABCG1 has a critical role in mediating cholesterol efflux to HDL and preventing cellular lipid accumulation. Cell Metab. 1: 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaughan A. M., Oram J. F. 2005. ABCG1 redistributes cell cholesterol to domains removable by high density lipoprotein but not by lipid-depleted apolipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 30150–30157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang N., Lan D., Chen W., Matsuura F., Tall A. R. 2004. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101: 9774–9779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X., Collins H. L., Ranalletta M., Fuki I. V., Billheimer J. T., Rothblat G. H., Tall A. R., Rader D. J. 2007. Macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1, but not SR-BI, promote macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 117: 2216–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelissen I. C., Harris M., Rye K. A., Quinn C., Brown A. J., Kockx M., Cartland S., Packianathan M., Kritharides L., Jessup W. 2006. ABCA1 and ABCG1 synergize to mediate cholesterol export to apoA-I. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sankaranarayanan S., Oram J. F., Asztalos B. F., Vaughan A. M., Lund-Katz S., Adorni M. P., Phillips M. C., Rothblat G. H. 2009. Effects of acceptor composition and mechanism of ABCG1-mediated cellular free cholesterol efflux. J. Lipid Res. 50: 275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldo S. W., Li Y., Buono C., Zhao B., Billings E. M., Chang J., Kruth H. S. 2008. Heterogeneity of human macrophages in culture and in atherosclerotic plaques. Am. J. Pathol. 172: 1112–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akagawa K. S., Komuro I., Kanazawa H., Yamazaki T., Mochida K., Kishi F. 2006. Functional heterogeneity of colony-stimulating factor-induced human monocyte-derived macrophages. Respirology. 11(Suppl.): S32–S36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruth H. S., Ifrim I., Chang J., Addadi L., Perl-Treves D., Zhang W. Y. 2001. Monoclonal antibody detection of plasma membrane cholesterol microdomains responsive to cholesterol trafficking. J. Lipid Res. 42: 1492–1500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong D. S., Anzinger J. J., Leyva F. J., Rubin N., Addadi L., Kruth H. S. 2010. Extracellular cholesterol-rich microdomains generated by human macrophages and their potential function in reverse cholesterol transport. J. Lipid Res. 51: 2303–2313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perl-Treves D., Kessler N., Izhaky D., Addadi L. 1996. Monoclonal antibody recognition of cholesterol monohydrate crystal faces. Chem. Biol. 3: 567–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addadi L., Geva M., Kruth H. S. 2003. Structural information about organized cholesterol domains from specific antibody recognition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1610: 208–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ziblat R., Fargion I., Leiserowitz L., Addadi L. 2012. Spontaneous formation of two-dimensional and three-dimensional cholesterol crystals in single hydrated lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 103: 255–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruth H. S., Jones N. L., Huang W., Zhao B., Ishii I., Chang J., Combs C. A., Malide D., Zhang W. Y. 2005. Macropinocytosis is the endocytic pathway that mediates macrophage foam cell formation with native low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 2352–2360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruth H. S., Comly M. E., Butler J. D., Vanier M. T., Fink J. K., Wenger D. A., Patel S., Pentchev P. G. 1986. Type C Niemann-Pick disease. Abnormal metabolism of low density lipoprotein in homozygous and heterozygous fibroblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 261: 16769–16774 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sokol J., Blanchette-Mackie J., Kruth H. S., Dwyer N. K., Amende L. M., Butler J. D., Robinson E., Patel S., Brady R. O., Comly M. E., et al. 1988. Type C Niemann-Pick disease. Lysosomal accumulation and defective intracellular mobilization of low density lipoprotein cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 3411–3417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liscum L. 1990. Pharmacological inhibition of the intracellular transport of low-density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1045: 40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruth H. S., Skarlatos S. I., Lilly K., Chang J., Ifrim I. 1995. Sequestration of acetylated LDL and cholesterol crystals by human monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 129: 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto S., Yamada M., Motoyoshi K., Akagawa K. S. 1997. Enhancement of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced growth and differentiation of human monocytes by interleukin-10. Blood. 89: 315–321 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Draper D. W., Gowdy K. M., Madenspacher J. H., Wilson R. H., Whitehead G. S., Nakano H., Pandiri A. R., Foley J. F., Remaley A. T., Cook D. N., et al. 2012. ATP binding cassette transporter G1 deletion induces IL-17-dependent dysregulation of pulmonary adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 188: 5327–5336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoff J. 2000. Methods of blood collection in the mouse. Lab. Anim. 29: 47–53 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G. H. 1957. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226: 497–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gamble W., Vaughan M., Kruth H. S., Avigan J. 1978. Procedure for determination of free and total cholesterol in micro- or nanogram amounts suitable for studies with cultured cells. J. Lipid Res. 19: 1068–1070 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193: 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstein J. L., Basu S. K., Brown M. S. 1983. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein in cultured cells. Methods Enzymol. 98: 241–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown M. S., Ho Y. K., Goldstein J. L. 1980. The cholesteryl ester cycle in macrophage foam cells. Continual hydrolysis and re-esterification of cytoplasmic cholesteryl esters. J. Biol. Chem. 255: 9344–9352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yancey P. G., Rodrigueza W. V., Kilsdonk E. P., Stoudt G. W., Johnson W. J., Phillips M. C., Rothblat G. H. 1996. Cellular cholesterol efflux mediated by cyclodextrins. Demonstration of kinetic pools and mechanism of efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 16026–16034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tontonoz P., Mangelsdorf D. J. 2003. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 17: 985–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Favari E., Zanotti I., Zimetti F., Ronda N., Bernini F., Rothblat G. H. 2004. Probucol inhibits ABCA1-mediated cellular lipid efflux. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 2345–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu C. A., Tsujita M., Hayashi M., Yokoyama S. 2004. Probucol inactivates ABCA1 in the plasma membrane with respect to its mediation of apolipoprotein binding and high density lipoprotein assembly and to its proteolytic degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 30168–30174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendez A. J., Lin G., Wade D. P., Lawn R. M., Oram J. F. 2001. Membrane lipid domains distinct from cholesterol/sphingomyelin-rich rafts are involved in the ABCA1-mediated lipid secretory pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 3158–3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess J. W., Kiss R. S., Zheng H., Zachariah S., Marcel Y. L. 2002. Trypsin-sensitive and lipid-containing sites of the macrophage extracellular matrix bind apolipoprotein A-I and participate in ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 31318–31326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho Y. K., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. 1980. Hydrolysis and excretion of cytoplasmic cholesteryl esters by macrophages: stimulation by high density lipoprotein and other agents. J. Lipid Res. 21: 391–398 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oram J. F., Yokoyama S. 1996. Apolipoprotein-mediated removal of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids. J. Lipid Res. 37: 2473–2491 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Favari E., Calabresi L., Adorni M. P., Jessup W., Simonelli S., Franceschini G., Bernini F. 2009. Small discoidal pre-beta1 HDL particles are efficient acceptors of cell cholesterol via ABCA1 and ABCG1. Biochemistry. 48: 11067–11074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang N., Silver D. L., Costet P., Tall A. R. 2000. Specific binding of ApoA-I, enhanced cholesterol efflux, and altered plasma membrane morphology in cells expressing ABC1. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 33053–33058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Larrede S., Quinn C. M., Jessup W., Frisdal E., Olivier M., Hsieh V., Kim M. J., Van Eck M., Couvert P., Carrie A., et al. 2009. Stimulation of cholesterol efflux by LXR agonists in cholesterol-loaded human macrophages is ABCA1-dependent but ABCG1-independent. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 1930–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaughan A. M., Oram J. F. 2003. ABCA1 redistributes membrane cholesterol independent of apolipoprotein interactions. J. Lipid Res. 44: 1373–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorenzi I., von Eckardstein A., Radosavljevic S., Rohrer L. 2008. Lipidation of apolipoprotein A-I by ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC) A1 generates an interaction partner for ABCG1 but not for scavenger receptor BI. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1781: 306–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaughan A. M., Oram J. F. 2006. ABCA1 and ABCG1 or ABCG4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich HDL. J. Lipid Res. 47: 2433–2443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi A., Takanezawa Y., Hirata T., Shimizu Y., Misasa K., Kioka N., Arai H., Ueda K., Matsuo M. 2006. Efflux of sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and phosphatidylcholine by ABCG1. J. Lipid Res. 47: 1791–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukuda M., Nakano M., Sriwongsitanont S., Ueno M., Kuroda Y., Handa T. 2007. Spontaneous reconstitution of discoidal HDL from sphingomyelin-containing model membranes by apolipoprotein A-I. J. Lipid Res. 48: 882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meurs I., Lammers B., Zhao Y., Out R., Hildebrand R. B., Hoekstra M., Van Berkel T. J., Van Eck M. 2012. The effect of ABCG1 deficiency on atherosclerotic lesion development in LDL receptor knockout mice depends on the stage of atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 221: 41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Out R., Hoekstra M., Habets K., Meurs I., de Waard V., Hildebrand R. B., Wang Y., Chimini G., Kuiper J., Van Berkel T. J., et al. 2008. Combined deletion of macrophage ABCA1 and ABCG1 leads to massive lipid accumulation in tissue macrophages and distinct atherosclerosis at relatively low plasma cholesterol levels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 258–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yvan-Charvet L., Ranalletta M., Wang N., Han S., Terasaka N., Li R., Welch C., Tall A. R. 2007. Combined deficiency of ABCA1 and ABCG1 promotes foam cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 117: 3900–3908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tarling E. J., Edwards P. A. 2011. ATP binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1) is an intracellular sterol transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108: 19719–19724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engel T., Kannenberg F., Fobker M., Nofer J. R., Bode G., Lueken A., Assmann G., Seedorf U. 2007. Expression of ATP binding cassette-transporter ABCG1 prevents cell death by transporting cytotoxic 7beta-hydroxycholesterol. FEBS Lett. 581: 1673–1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terasaka N., Wang N., Yvan-Charvet L., Tall A. R. 2007. High-density lipoprotein protects macrophages from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced apoptosis by promoting efflux of 7-ketocholesterol via ABCG1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104: 15093–15098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.