Abstract

Insulin resistance (IR) is associated with elevated plasma levels of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs) of intestinal origin. However, the mechanisms underlying the overaccumulation of apolipoprotein (apo)B-48-containing TRLs in individuals with IR are not yet fully understood. This study examined the relationships between apoB-48-containing TRL kinetics and the expression of key intestinal genes and proteins involved in lipid/lipoprotein metabolism in 14 obese nondiabetic men with IR compared with 10 insulin-sensitive (IS) men matched for waist circumference. The in vivo kinetics of TRL apoB-48 were assessed using a primed-constant infusion of L-[5,5,5-D3]leucine for 12 h with the participants in a constantly fed state. The expression of key intestinal genes and proteins involved in lipid/lipoprotein metabolism was assessed by performing real-time PCR quantification and LC-MS/MS on duodenal biopsy specimens. The TRL apoB-48 pool size and production rate were 102% (P < 0.0001) and 87% (P = 0.01) greater, respectively, in the men with IR versus the IS men. On the other hand, intestinal mRNA levels of sterol regulatory element binding factor-2, hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α, and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein were significantly lower in the men with IR than in the IS men. These data indicate that IR is associated with intestinal overproduction of lipoproteins and significant downregulation of key intestinal genes involved in lipid/lipoprotein metabolism.

Keywords: apolipoprotein B-48, apolipoprotein B-100, cholesterol, fatty acids, kinetic, intestine

Dyslipidemia is an important feature of insulin resistance (IR) that contributes to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (1). Dyslipidemia associated with IR is typically characterized by elevated concentrations of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs), reduced plasma levels of HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C), an increased number of small dense LDL particles, and greater levels of free fatty acid (FFA) (1). Metabolic kinetic studies have indicated that the increased plasma levels of TRLs in individuals with IR are caused by the elevated secretion of both hepatic (apoB-100-containing) and intestinal (apoB-48-containing) lipoproteins in fasting and postprandial states (2–5). We have already shown that the intestinal lipoprotein production rate (PR) is markedly greater in dyslipidemic patients with type 2 diabetes (6). This relationship is of significant interest because there is now convincing evidence indicating that elevated levels of intestine-derived lipoproteins are proatherogenic and associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (7–9). Hence, a better understanding of the factors regulating intestinal lipoprotein secretion could potentially lead to rational therapeutic strategies to reduce cardiovascular risk in this vulnerable group of patients.

Recent findings from animal models of IR are consistent with data from humans that have revealed the overproduction of intestinal apoB-48-containing lipoproteins (10, 11). Studies have also consistently supported the concept that inducing IR in various animal models is associated with significant upregulation of the expression of key intestinal genes involved in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism (12, 13). Although the upregulation of the key intestinal genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism may play an important role in the overproduction of intestinal lipoproteins in individuals with IR, this phenomenon has not yet been examined in humans. In the present study, we investigated the relationships between intestinally derived apoB-48-containing lipoprotein kinetics and the expression of key intestinal genes and proteins involved in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in nondiabetic men with IR compared with insulin-sensitive (IS) men. The gene expression and protein mass levels were measured in human tissue obtained in duodenal biopsies. We hypothesized that IR would be associated with significant upregulation of the expression of key intestinal genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism.

METHODS

Subjects

Fourteen nondiabetic males with IR and ten IS male control subjects, matched for waist circumference, were recruited from the Quebec City area to participate in the study. To be included in the study, the subjects with IR were required to have a plasma triglyceride (TG) level >1.5 mmol/l, a homeostasis model of assessment (HOMA)-IR index >2.5, and a waist circumference >94 cm. On the other hand, the IS subjects were required to have a plasma TG level <1.5 mmol/l, a HOMA-IR index <2.5, and a waist circumference >94 cm. Both groups of subjects were matched for waist circumference to adjust for undetermined obesity-associated factors that could potentially modulate lipoprotein kinetics and intestinal gene expression. Subjects were excluded if they had elevated blood pressure, monogenic hyperlipidemia (such as familial hypercholesterolemia), plasma TG levels >4.5 mmol/l, a recent history of alcohol or drug abuse, diabetes mellitus, or a history of cancer. Furthermore, none of the participants were first- or second-degree relatives. The study consisted of a 1 week screening period followed by a kinetic study using primed-constant infusion of deuterated leucine and duodenal biopsies performed within a 2 day timeframe. The research protocol was approved by the Laval University Medical Centre ethical review committee and written informed consent was obtained from each subject. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01829945.

Experimental protocol for in vivo stable isotope kinetics

To determine the kinetics of TRL apoB-48, VLDL, intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL), and LDL apoB-100, the subjects underwent a primed-constant infusion of L-[5,5,5-D3]leucine while they were in a constant fed state. Starting at 7:00 AM, the subjects consumed 30 small identical cookies every half-hour for 15 h. Each cookie contained to 1/30th of their estimated daily food intake based on the Harris-Benedict equation (14), with 15% of the calories from protein, 45% from carbohydrates, and 40% from fat (7% saturated, 26% monounsaturated, 7% polyunsaturated), as well as 85 mg of cholesterol/1,000 kcal. At 10:00 AM, with two intravenous lines in place, one for the infusate and one for blood sampling, L-[5,5,5-D3]leucine (10 μmol/kg body weight) was injected as a bolus iv and then by continuous infusion (10 μmol·kg body wt−1·h−1) over a 12 h period. Blood samples (20 ml) were collected after 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, and 12 h.

Characterization of plasma lipids and lipoproteins

Twelve hour fasting venous blood samples were obtained from an antecubital vein prior to the beginning of the kinetic study. The serum was separated from the blood cells by performing centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Serum cholesterol and TG concentrations were determined with a Roche/Hitachi Modular analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, PQ, Canada) using Roche Diagnostics reagents. The VLDL (TRL) (d < 1.006 g/ml), IDL (d = 1.006–1.019 g/ml), and LDL (d = 1.019–1.063 g/ml) fractions were isolated from fresh plasma stored in Vacutainer tubes containing EDTA (0.1% final concentration) using sequential ultracentrifugation (15), and HDL-C was measured as previously described (16). The plasma concentrations of lathosterol (a precursor in the biosynthesis of cholesterol) and the plant sterols campesterol and β-sitosterol (used as plasma surrogates of intestinal cholesterol absorption) were quantified using a gas chromatography method similar to a method previously described (17). Because noncholesterol sterols are transported in plasma by lipoproteins, their concentrations were expressed relative to the total cholesterol concentration (mmol/mol of cholesterol) to correct for the differences in the numbers of lipoprotein acceptor particles.

Measurement of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, glucagon, and glucagon-like peptide-1

Plasma glucose was measured enzymatically, whereas plasma insulin was measured using a radioimmunoassay with polyethylene glycol separation (18, 19). The plasma C-peptide levels were measured using a modified version of Heding's method (20) with polyclonal antibody A-4741 from Ventrex (Portland, ME) and polyethylene glycol precipitation (18). The interassay coefficient of variation was 1.0% for a basal glucose value set at 5.0 mmol/l. Glucagon was analyzed using an in-house assay that has previously been described (21). The blood samples for measuring intact glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) were collected into chilled tubes containing a proprietary Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) protease inhibitor (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and intact GLP-1 was determined as previously described (21). The HOMA-IR index value was calculated using the following formula: fasting blood glucose (mmol/l) × fasting insulin (mU/l)/22.5 (22). β-Cell function was assessed using the following formula: 20 × fasting insulin (mU/l)/[fasting glucose (mmol/l)-3.5] (22).

Quantification and isolation of apoB-48 and apoB-100

The apoB-100 and apoB-48 concentrations in TRLs (VLDL) were determined by performing a noncompetitive ELISA using immuno-purified polyclonal antibodies (Alerchek Inc., Portland, ME) and (Shibayagi Co. Ltd., Gunma, Japan) to calculate their respective pool sizes (PSs). We used three different time points during the kinetic study to estimate the average concentrations of apoB-100 and apoB-48. ApoB-100 and apoB-48 were then separated by SDS polyacrylamide slab gel electrophoresis according to standardized procedures (23). Briefly, 50 μl of the TRL, IDL, or LDL fractions were mixed with 50 μl of 3% SDS sample buffer and subjected to electrophoresis in 3–10% linear gradient polyacrylamide slab mini gels. The gels were stained for 2–3 h in 0.25% Coomassie Blue R-250 and destained overnight.

Isotopic enrichment determinations

ApoB-48 and apoB-100 bands were excised from polyacrylamide gels, and the bands were hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl at 110°C for 24 h (24). Trifluoroacetic acid and trifluoroacetic anhydride (1:1) were used as derivatization reagents for the amino acids before the analysis was conducted using a Hewlett-Packard 6890/5973 gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer (25). The isotope enrichment (%) and tracer/tracee ratios (%) were calculated from the observed ion current ratios (26). The isotopic enrichment of leucine in the apolipoproteins was expressed as the tracer/tracee ratio (%) using standardized formulas (26).

Kinetic analysis

The kinetics of TRL apoB-48 and apoB-100 in the VLDL, IDL, and LDL fractions were derived using a multi-compartmental model that has been previously described (27).

Intestinal biopsies

Biopsies were obtained from the second portion of the duodenum during the gastro-duodenoscopy. Six biopsy samples were collected using multiple-sample single-use biopsy forceps, immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before RNA extraction.

Total RNA extraction, RNA quantification, and quantitative real-time PCR

The intestinal biopsy tissue samples were homogenized in 1 ml of Qiazol and were extracted using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). The tissue samples were also treated with an RNase-free DNase set to eliminate any contaminating DNA. Total RNA was then eluted into 100 μl RNase-free H2O and stored at −80°C. RNA quantification and quantitative real-time PCR were performed as described (28).

Determination of protein levels by LC-MS/MS in duodenal biopsy samples

Duodenal biopsy samples were milled in a frozen state and solubilized in extraction buffer (0.5% deoxycholate, 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 50 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors). Next, 20 μg of proteins were reduced (Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride, 3.1 mM), alkylated (S-methyl methanethiosulfonate, 6 mM), and then digested with trypsin (1 μg) overnight. Purified synthetic peptides containing [13C6]Lys and [13C6]Arg were obtained from JPT Peptide Technologies (Germany) and reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid to a final concentration of 500 pmol/μl. Three transitions were optimized on two peptides for each of the five target proteins using MRMPilot 2.1. Supplementary Table I shows the target peptides for each of the five proteins assessed. A 200 ng sample of peptides (in 5 ul) was analyzed on an ABSciex 4000QTRAPTM hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent 1100TM series LC system controlled by Analyst 1.5TM and a nanospray ionization source. The MS analysis was conducted in positive ion mode with an ion spray voltage of 2,200 V. The collision energy was optimized for each transition, and the scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) algorithm acquisition mode was used. The acquisition method was developed using MRMPilot 2.1TM. LC-MRM/MS analyses were performed using three transitions on two peptides for each of the target proteins. The MRM transition that yielded the highest area counts was used for the measurements, and the other two transitions acted as qualifier transitions to confirm the peptide retention times and the fragment ion ratios. The samples were analyzed in duplicate. The concentration of proteins was normalized with villin, a characteristic brush border membrane marker (29).

Statistical analysis

Student's t-tests were used to compare the lipid-lipoprotein profile, glucose homeostasis, kinetic parameters, and mRNA expression between the IR group and the IS group. Spearman's correlation coefficients were determined to assess the significance of the associations. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. All of the analyses were performed using JMP statistical software (version 10.0; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and fasting biochemical parameters of the subjects

The demographic characteristics and fasting biochemical parameters of the IR and control subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean age, body mass index, and waist circumference of the participants did not differ significantly between the two groups. The subjects with IR had higher systolic (+10.9%, P = 0.01) and diastolic (+17.6%, P = 0.003) blood pressure than the control subjects. Compared with the control subjects, the subjects with IR had significantly higher plasma levels of total cholesterol (+20.8%, P = 0.02), TGs (+224%, P < 0.0001), apoB (+49.3%, P = 0.0004), VLDL-cholesterol (+327%, P < 0.0001), VLDL-TGs (+341%, P < 0.0001), and lower HDL-C (−29.2%, P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the participants with IR had elevated levels of LDL apoB (+34.8%, P = 0.006), but they did not have significantly different LDL-cholesterol levels, suggesting that they had higher concentrations of small dense LDL particles. Surrogates of cholesterol absorption (campesterol and β-sitosterol) and synthesis (lathosterol) in plasma were also assessed. Compared with the control subjects, the participants with IR had lower levels of campesterol (−21.8%, P = 0.05) and β-sitosterol (−26.5%, P = 0.03) and higher levels of lathosterol (+31.7%, P = 0.06), suggesting that these subjects have higher rates of synthesis and lower rates of cholesterol absorption.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics and fasting biochemical parameters of the subjects

| Variables | Insulin-Sensitive Subjects (n = 10) | Insulin-Resistant Subjects (n = 14) | %Δa | P |

| Age (years) | 33.7 (21.1–55.5) | 40.3 (27.2–61.4) | +19.6 | 0.17 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.8 (25.5–41.8) | 30.7 (26.4–36.4) | +0.3 | 0.62 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 105.5 (97.0–130.3) | 106.2 (95.7–125.9) | +0.6 | 0.87 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 110 (95–127) | 122 (102–141) | +10.9 | 0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 68 (62–77) | 80 (63–93) | +17.6 | 0.003 |

| Serum | ||||

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 4.48 (3.29–5.37) | 5.41 (3.66–7.72) | +20.8 | 0.02 |

| TGs (mmol/l) | 0.93 (0.57–1.4) | 3.01 (1.51–5.62) | +224 | <0.0001 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.75 (0.45–0.96) | 1.12 (0.73–1.52) | +49.3 | 0.0004 |

| VLDL | ||||

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 0.26 (0.09–0.53) | 1.11 (0.46–2.49) | +327 | <0.0001 |

| TGs (mmol/l) | 0.54 (0.17–0.76) | 2.38 (1.03–4.55) | +341 | <0.0001 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.06 (0.02–0.10) | 0.19 (0.11–0.31) | +217 | <0.0001 |

| LDL | ||||

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 2.91 (1.74–3.68) | 3.37 (1.76–5.67) | +15.8 | 0.21 |

| TGs (mmol/l) | 0.17 (0.10–0.30) | 0.36 (0.19–0.66) | +112 | 0.0003 |

| ApoB (g/l) | 0.69 (0.43–0.90) | 0.93 (0.60–1.32) | +34.8 | 0.006 |

| HDL | ||||

| Cholesterol (mmol/l) | 1.30 (0.98–1.49) | 0.92 (0.69–1.27) | −29.2 | <0.0001 |

| TGs (mmol/l) | 0.22 (0.17–0.34) | 0.28 (0.15–0.41) | +27.3 | 0.02 |

| ApoAI (g/l) | 1.33 (1.15–1.63) | 1.17 (0.98–1.31) | −12.0 | 0.005 |

| Cholesterol homeostasisb | ||||

| Lathosterol | 227 (111–305) | 299 (161–578) | +31.7 | 0.06 |

| Campesterol | 165 (91–247) | 129 (83–226) | −21.8 | 0.05 |

| β-sitosterol | 162 (102–228) | 119 (66–237) | −26.5 | 0.03 |

Data are presented as mean (range).

%Δ represents the percent difference between the two groups.

Cholesterol homeostasis: 102 μmol/mmol of cholesterol.

Table 2 shows the parameters related to glucose homeostasis and the FFA concentrations in both the fasting state and the constantly fed state. In the fasting state, the IR group had significantly higher levels of glucose (+7.0%, P = 0.009), insulin (+125%, P < 0.0001), and C-peptide (+28.1%, P = 0.0009), and consequently, the HOMA-IR index was significantly higher among the subjects with IR than among the control subjects (+141%, P < 0.0001). When the participants were in the constantly fed state during the kinetic study, the levels of insulin and C-peptide were higher in the IR group than in the control group. Compared with the control subjects, the subjects with IR had significantly higher FFA concentrations in the fed state (+77.0%, P = 0.04). No significant differences were observed between the two study groups in the fasting and nonfasting levels of plasma glucagon and GLP-1.

TABLE 2.

Glucose homeostasis and FFA concentrations of the subjects

| Variables | Insulin-Sensitive Subjects (n = 10) | Insulin-Resistant Subjects (n = 14) | %Δa | P |

| Fasting | ||||

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 5.7 (5.3–6.2) | 6.1 (5.6–7.0) | +7.0 | 0.009 |

| Insulin (ρmol/l) | 52.9 (36–65) | 119 (75–196) | +125 | <0.0001 |

| C-peptide (ρmol/l) | 960 (728–1260) | 1326 (1080–1901) | +28.1 | 0.0009 |

| Glucagon (ρg/ml) | 206 (91–478) | 255 (76–526) | +23.8 | 0.41 |

| GLP-1active (ρmol/l) | 1.41 (0.52–4.97) | 3.11 (0.55–28.4) | +121 | 0.45 |

| GLP-1total (ρmol/l) | 2.11 (0.40–7.00) | 3.26 (0.54–21.3) | +54.5 | 0.53 |

| FFAs (μM) | 504 (371–816) | 410 (299–659) | −18.7 | 0.06 |

| HOMA-IR index | 1.94 (1.34–2.33) | 4.67 (2.98–8.52) | +141 | <0.0001 |

| Fed state | ||||

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 6.3 (5.5–7.2) | 6.6 (5.9–7.5) | +4.8 | 0.17 |

| Insulin (ρmol/l) | 157 (117–247) | 286 (144–496) | +82.2 | 0.003 |

| C-peptide (ρmol/l) | 1,823 (1,266–2,403) | 2,628 (1,885–3,508) | +44.2 | 0.0002 |

| Glucagon (ρg/ml) | 178 (104–379) | 255 (71–511) | +43.3 | 0.17 |

| GLP-1active (ρmol/l) | 1.56 (0.73–4.81) | 3.60 (0.90–30.2) | +131 | 0.42 |

| GLP-1total (ρmol/l) | 3.42 (1.52–7.63) | 4.91 (1.56–22.9) | +43.6 | 0.43 |

| FFAs (μM) | 183 (124–240) | 324 (152–942) | +77.0 | 0.04 |

Data are presented as mean (range).

%Δ represents the percent difference between the two groups.

Kinetics of TRL apoB-48

The analyses of the deuterated plasma amino acids and the lipid/lipoprotein measurements indicated that plasma leucine enrichments as well as plasma TG and TRL apoB-48 levels remained constant throughout the infusion (data not shown). The detailed kinetic information obtained from the multi-compartmental model analysis is summarized in Table 3. Compared with the control group, the group with IR showed significantly higher TRL apoB-48 PS (+102%, P < 0.0001), which can be attributed to higher PR (+86.7%, P = 0.01).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of apoB-48 in TRLs and apoB-100 in VLDLs, IDLs, and LDLs in insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant subjects

| Kinetic parameters | Insulin-Sensitive Subjects (n = 10) | Insulin-Resistant Subjects (n = 14) | %Δa | P |

| TRL apoB-48 | ||||

| PS (mg) | 24.8 (14.3–33.7) | 50.2 (28.5–81.9) | +102 | <0.0001 |

| FCR (pools/day) | 6.7 (1.5–13.9) | 4.8 (1.7–11.4) | −28.4 | 0.13 |

| PR (mg/kg/day) | 1.5 (0.5–2.7) | 2.8 (0.8–5.8) | +86.7 | 0.01 |

| VLDL apoB-100 | ||||

| PS (mg) | 218 (100–347) | 460 (308–681) | +111 | <0.0001 |

| FCR (pools/day) | 8.2 (5.1–11.9) | 5.4 (3.8–8.4) | −34.1 | 0.0006 |

| PR (mg/kg/day) | 18.1 (14.7–27.4) | 25.3 (19.8–34.4) | +39.8 | 0.0006 |

| IDL apoB-100 | ||||

| PS (mg) | 46.4 (22.0–87.4) | 60.4 (24.9–119) | +30.2 | 0.21 |

| FCR (pools/day) | 24.4 (10.9–48.7) | 17.9 (5.7–32.4) | −26.6 | 0.16 |

| PR (mg/kg/day) | 10.1 (5.8–15.0) | 11.0 (3.5–21.1) | −8.9 | 0.67 |

| LDL apoB-100 | ||||

| PS (mg) | 2,136 (1,080–3,730) | 3,180 (1,175–6,592) | +48.9 | 0.08 |

| FCR (pools/day) | 0.54 (0.34–1.00) | 0.39 (0.10–0.79) | −27.8 | 0.06 |

| PR (mg/kg/day) | 10.9 (8.5–13.9) | 11.5 (6.2–20.8) | +5.5 | 0.68 |

Data are presented as mean (range).

%Δ represents the percent difference between the two groups.

Kinetics of VLDL, IDL, and LDL apoB-100

Compared with the control group, the group with IR had significantly higher VLDL apoB-100 PS (+111%, P < 0.0001) because of their lower VLDL apoB-100 fractional catabolic rate (FCR) (−34.1%, P = 0.0006) and higher PR (+39.8%, P = 0.0006). There was no significant difference between the two groups in IDL apoB-100 PS, PR, and FCR. The group with IR exhibited a trend in higher LDL apoB-100 PS (+48.9%, P = 0.08), mainly because of the lower LDL apoB-100 FCR (−27.8%, P = 0.06) they demonstrated compared with the control group.

Intestinal mRNA levels

Next, we questioned whether IR was associated with variations in the expression of key genes involved in intestinal lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. As shown in Table 4, studies of gene expression have revealed that IR is associated with significantly lower intestinal mRNA levels of the following nuclear transcription factors: sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-2 (−26.1%; P = 0.002) and hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α (HNF-4α) (−17.7%; P = 0.03). The intestinal expression of acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2 (ACAT-2) (−14.5%; P = 0.02) was also significantly lower in the subjects with IR. The intestinal expression of various key genes involved in fatty acid metabolism and transport was also lower in the subjects with IR. Specifically, the mRNA levels of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACAC)-α (−18.3%, P = 0.02), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD)-1 (−38.5%, P = 0.005), and acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS)-1 (−29.5%, P = 0.004) were all significantly lower in the subjects with IR compared with the control subjects. There were no significant differences between the groups in the expression of ACAC-β, fatty acid synthase (FASN), fatty acid desaturase (FADS)-1 and FADS-2, fatty acid binding protein 2 (FABP-2), and fatty acid transporter member 4 (FATP-4). The mRNA levels of diacylglycerol-O-acetyltransferase (DGAT)-2 were 36.4% (P = 0.02) lower in the participants with IR compared with the control subjects, but there were no significant changes in mannosyl (α-1,6-)-glycoprotein β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-2 (MGAT-2) and DGAT-1 gene expression. Finally, the expression of microsomal TG transfer protein (MTP) (−22.2%, P = 0.04) and SAR1 homolog B (SAR1-β) (−13.0%, P = 0.05), two genes that play crucial roles in chylomicron assembly and transport, was significantly lower in the subjects with IR compared with the control subjects. No significant changes were observed in the two study groups in apoB, LDL receptor (LDLR), VLDL receptor (VLDLR), or proprotein convertase subtilizing kexin-9 (PCSK9) gene expression.

TABLE 4.

Intestinal mRNA expression levels of key genes involved in lipid/lipoprotein metabolism in insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant subjects

| Genes | Insulin-Sensitive Subjects(n = 10)a | Insulin-Resistant Subjects(n = 14)a | %Δb | P |

| Nuclear transcription factors | ||||

| SREBP-1c | 103,061 (72,556–132,424) | 84,245 (28,799–141,615) | −18.3 | 0.07 |

| SREBP-2 | 78,286 (59,832–104,740) | 57,861 (36,402–90,403) | −26.1 | 0.002 |

| HNF-4α | 221,725 (154,765–272,294) | 182467 (89,208–282,002) | −17.7 | 0.03 |

| Cholesterol metabolism and transport | ||||

| HMG-CoAR | 135,217 (105,931–175,075) | 121,413 (83,901–193,351) | −10.2 | 0.20 |

| ACAT-2 | 92,368 (73,234–115,853) | 78,944 (58,989–106,175) | −14.5 | 0.02 |

| NPC1L1 | 182,985 (105,689–235,569) | 157,721 (37,214–223,141) | −13.8 | 0.23 |

| ABCG5 | 485,668 (226,188–688,006) | 553,028 (63,577–1,042,395) | +13.9 | 0.50 |

| ABCG8 | 80,645 (35,696–110,128) | 97,735 (16,716–200,957) | +21.2 | 0.34 |

| Fatty acid metabolism and transport | ||||

| ACAC-α | 11,508 (8,079–14,222) | 9,402 (5,871–14,480) | −18.3 | 0.02 |

| ACAC-β | 33,109 (23,994–46,529) | 27,708 (13,581–40,946) | −16.3 | 0.11 |

| SCD-1 | 248,397 (109,640–413,704) | 152,841 (73,055–261,121) | −38.5 | 0.005 |

| FASN | 35,738 (24,953–54,314) | 34,663 (24,574–43,961) | −3.0 | 0.72 |

| FADS-1 | 50,385 (27,446–66,916) | 50,265 (33,789–80,123) | −0.2 | 0.98 |

| FADS-2 | 82,328 (35,290–193,593) | 63,244 (37,686–119,244) | −23.2 | 0.23 |

| ACS-1 | 234,643 (166,259–299,052) | 165,512 (92,018–294,548) | −29.5 | 0.004 |

| FABP-2 | 1,072,609 (583,724–1,560,837) | 826,754 (298,624–1,559,120) | −22.9 | 0.09 |

| FATP-4 | 248,109 (140,351–351,911) | 214,169 (77,530–322,808) | −13.7 | 0.16 |

| TG synthesis | ||||

| MGAT-2 | 140,578 (94,276–162,549) | 136,810 (94,285–185,629) | −2.7 | 0.70 |

| DGAT-1 | 1,440,914 (942,704–1,774,111) | 1,403,681 (430,007–2,405,061) | −2.6 | 0.81 |

| DGAT-2 | 483,519 (155,048–832,777) | 307,648 (14,464–708,806) | −36.4 | 0.02 |

| Lipoprotein assembly and transport | ||||

| MTP | 4,531,746 (2,484,929–6,050,915) | 3,527,300 (1,373,649–5,914,664) | −22.2 | 0.04 |

| ApoB | 2,090,646 (1,077,168–3,679,436) | 1,810,004 (209,862–3,527,715) | −13.4 | 0.40 |

| LDLR | 79,207 (48,131–128,499) | 77,845 (52,005–119,326) | −1.7 | 0.90 |

| VLDLR | 6,618 (4,638–9,068) | 6,294 (3,972–10,812) | −4.9 | 0.63 |

| PCSK9 | 9,359 (2,975–2,0741) | 6,598 (2,542–13,163) | −29.5 | 0.10 |

| SAR1-β | 549,199 (417,362–643,585) | 477,697 (276,895–673,281) | −13.0 | 0.05 |

The results are expressed as the number of copies per 100,000 copies of the housekeeping gene glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase ± SD. HMG-CoAR, HMG-CoA reductase; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like 1; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin-9.

Number of copies per 100,000 copies glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

%Δ represents the percent difference between the two groups.

Tables 5 and 6 show the correlations between the mRNA levels of key intestinal genes in the control subjects and the subjects with IR. Intestinal SREBP-2 gene expression was strongly correlated with the mRNA levels of several genes that are known to be regulated by this nuclear transcription factor (HMG-CoA reductase, ACAT-2, ACS-1, and LDLR). MTP and apoB mRNA levels were also positively correlated in both groups of subjects.

TABLE 5.

Summary of the correlations between the mRNA levels of key intestinal genes in the insulin-sensitive subjects (n = 10)

| Genes | SREBP-1c | SREBP-2 | HNF-4α | HMG-CoAR | ACAT-2 | NPC1L1 | ACS-1 | FABP-2 | FATP-4 | MTP | ApoB |

| SREBP-2 | 0.32 | — | |||||||||

| HNF-4α | 0.22 | 0.34 | — | ||||||||

| HMG-CoAR | 0.10 | 0.90b | 0.16 | — | |||||||

| ACAT-2 | 0.10 | 0.91b | 0.25 | 0.93c | — | ||||||

| NPC1L1 | −0.03 | 0.32 | 0.66a | 0.07 | 0.26 | — | |||||

| ACS-1 | 0.47 | 0.89b | 0.26 | 0.89b | 0.81a | 0.05 | — | ||||

| FABP-2 | −0.04 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.34 | — | |||

| FATP-4 | −0.04 | 0.19 | 0.66a | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.76a | — | ||

| MTP | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 0.79a | 0.74a | — | |

| ApoB | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.68a | 0.75a | 0.66a | — |

| LDLR | 0.39 | 0.63a | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.71a | 0.14 | 0.60a | −0.34 | −0.27 | −0.03 | −0.11 |

The correlation analyses were performed using Spearman's rank order correlation test. HMG-CoAR, HMG-CoA reductase; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like 1.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.0001.

TABLE 6.

Summary of the correlations between mRNA levels of key intestinal genes in the insulin-resistant subjects (n = 14)

| Genes | SREBP-1c | SREBP-2 | HNF-4α | HMG-CoAR | ACAT-2 | NPC1L1 | ACS-1 | FABP-2 | FATP-4 | MTP | ApoB |

| SREBP-2 | 0.65a | — | |||||||||

| HNF-4α | 0.75a | 0.91c | — | ||||||||

| HMG-CoAR | 0.91c | 0.72a | 0.70a | — | |||||||

| ACAT-2 | 0.38 | 0.65a | 0.63a | 0.52a | — | ||||||

| NPC1L1 | 0.67a | 0.86c | 0.84b | 0.78a | 0.70a | — | |||||

| ACS-1 | 0.50 | 0.83b | 0.74a | 0.69a | 0.65a | 0.77b | — | ||||

| FABP-2 | 0.61a | 0.58a | 0.42 | 0.61a | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.42 | — | |||

| FATP-4 | 0.78b | 0.74a | 0.74a | 0.77b | 0.44 | 0.72a | 0.53a | 0.67a | — | ||

| MTP | 0.69a | 0.71a | 0.64a | 0.70a | 0.25 | 0.57a | 0.45 | 0.88c | 0.81b | — | |

| ApoB | 0.95c | 0.67a | 0.80b | 0.85b | 0.44 | 0.67a | 0.51 | 0.64a | 0.80b | 0.76a | — |

| LDLR | 0.35 | 0.71a | 0.64a | 0.49 | 0.79b | 0.72a | 0.70a | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.30 |

The correlation analyses were performed using Spearman's rank order correlation test. HMG-CoAR, HMG-CoA reductase; NPC1L1, Niemann-Pick C1-like 1.

P< 0.05.

P< 0.001.

P< 0.0001.

Intestinal protein levels assessed by LC-MS/MS

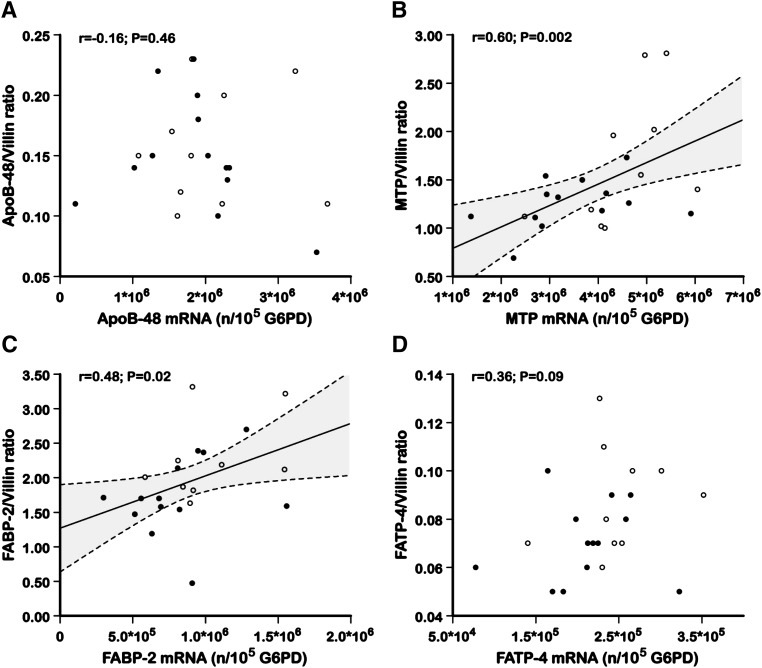

To examine the potential impact of IR on fatty acid absorption and lipoprotein metabolism in the fasting state, the protein mass levels of FABP-2, FATP-4, MTP, and apoB-48 in the duodenal biopsy specimens were assessed using LC-MS/MS. As shown in Table 7, the apoB-48 protein levels were not significantly different between the group with IR and the control group. The MTP, FABP-2, and FATP-4 protein levels, however, were significantly lower in the subjects with IR than in the control subjects (−25.4%, P = 0.05; −23.8%, P = 0.05, and −22.2%, P = 0.04, respectively). Figure 1 shows no significant correlation between the apoB-48 mRNA levels and the apoB-48 protein mass levels and between the FATP-4 mRNA levels and the FATP-4 protein mass levels. Positive correlations were observed, however, between the mRNA levels and the protein mass of MTP (r = 0.60, P = 0.002) and FABP-2 (r = 0.48, P = 0.02).

TABLE 7.

Intestinal protein levels assessed by LC-MS/MS in the insulin-sensitive and the insulin-resistant subjects

| Proteins | Insulin-Sensitive subjects(n = 10)a | Insulin-Resistant subjects(n = 14)a | %Δ | P |

| ApoB-48 | 0.16 (0.10–0.23) | 0.15 (0.07–0.23) | −6.3 | 0.79 |

| MTP | 1.69 (1.00–2.81) | 1.26 (069–1.73) | −25.4 | 0.05 |

| FABP-2 | 2.27 (1.63–3.32) | 1.73 (0.47–2.7) | −23.8 | 0.05 |

| FATP-4 | 0.09 (0.06–0.13) | 0.07 (0.05–1.00) | −22.2 | 0.04 |

The results are expressed as the molar ratio of the target protein normalized with the enterocyte-specific marker villin (range).

Target protein/villin ratio.

%Δ represents the percent difference between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

The correlations between intestinal mRNA and the corresponding protein levels for (A) apoB-48, (B) MTP, (C) FABP-2, and (D) FATP-4. mRNA levels are expressed as the number of mRNA copies per 100,000 copies of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) [mRNA (c/105 c G6PD)], and protein levels are expressed as the molar ratio of the target protein normalized with the enterocyte-specific marker villin. Open circles represent the control subjects, and filled circles represent the insulin-resistant subjects. The dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals for the regression lines.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the in vivo kinetics of TRL apoB-48 in the fed state were assessed using a stable isotope enrichment technique, and gene expression along with protein mass levels were assessed by conducting real-time PCR quantification and LC-MS/MS, respectively, on duodenal biopsy specimens from participants with IR and IS control participants in the fasted state. The plasma TRL concentrations were significantly higher in the subjects with IR because these subjects had higher PRs of intestinal and hepatic TRL particles as well as lower clearance rates. This study enhances the data from previous studies (2, 6) that revealed an oversecretion of TRL apoB-48 in subjects with IR. The current study provides new evidence, however, that key genes involved in intestinal lipid and lipoprotein metabolism are downregulated in subjects with IR compared with IS controls.

The cellular mechanisms that mediate the oversecretion of intestinal lipoproteins in individuals with IR have been extensively investigated in various animal models but not in humans. Comprehensive studies by Haidari et al. (30) have shown a 2- to 4-fold elevation in TRL apoB-48 secretion in vivo in fructose-fed Syrian golden hamsters compared with chow-fed hamsters. Ex vivo experiments with primary cultured enterocytes derived from these animals revealed that the oversecretion of intestinal lipoprotein was associated with greater stability of intracellular apoB-48, enhanced endogenous synthesis of TGs and cholesterol esters, elevated de novo lipogenesis, and greater MTP protein mass (30). Further evidence from sand rats appears to support the observations derived from the fructose-fed hamster model (31, 32). The sand rats that developed obesity and IR showed significantly higher rates of de novo TG synthesis, apoB-48, and TRLs, suggesting that IR induces an oversecretion of intestinal apoB-48-containing lipoproteins in these animals. Similarly, Vine et al. (33) reported impaired postprandial apoB-48 metabolism, greater TG absorption, and higher levels of apoB-48 in the lymph of obese IR JCR:LA-cp rats. Studies have also revealed abnormal intestinal lipoprotein metabolism in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Lally, Owens, and Tomkin (13) showed that cholesterol, TGs, apoB-48, and apoB-100 were elevated in the chylomicrons and VLDLs of these animals. Finally, Sasase et al. (34) provided evidence of increased fat absorption and impaired fat clearance in spontaneously diabetic Torii (SDT) rats, a finding suggesting a link between IR and the efficiency of intestinal lipid absorption and lipoprotein secretion. Data from animal models also support the notion that IR is associated with significant alterations in the expression of key intestinal genes involved in chylomicron production and cholesterol absorption. Intestinal MTP and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 mRNA levels were significantly increased in streptozotocin diabetic rats (12), and intestinal MTP, DGAT-1, and MGAT-2 mRNA expression were all significantly elevated in SDT rats (34).

Based on a previous report from our group showing that the expression of key genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism is highly regulated in the human duodenum following treatment with atorvastatin (35) or a high-fat diet (28), we have investigated the relationships between intestinally derived apoB-48-containing lipoprotein kinetics and the expression of major genes and proteins involved in lipid metabolism in nondiabetic males with IR compared with IS males. Our findings showed that IR in humans was associated with a significant downregulation of several key genes involved in intestinal fatty acid and lipoprotein metabolism. The plasma levels of TRL apoB-48 PS and PR measured in a constantly fed state were increased by 102% and 87%, respectively, in IR subjects. In contrast, intestinal MTP protein levels assessed by LC-MS/MS in the fasted state were decreased by 25% in IR and no significant difference was observed between subjects with IR and IS subjects in intestinal apoB-48 levels. These results suggest the absence of a direct correlation between fasted intestinal MTP and apoB-48 protein levels and postprandial TRL apoB-48 PR.

Only a few human studies have examined the potential mechanisms underlying the oversecretion of intestinal lipoproteins in individuals with IR. Previous findings by Veilleux et al. (36) have shown increased protein levels of MTP, elevated lipogenesis rate, higher expression of transcription factors SREBP and liver X receptor, and amplification of lipid and lipoprotein synthesis in small intestine sections obtained from obese diabetic subjects undergoing bariatric surgery. Phillips et al. (37) have also reported that diabetic subjects had significantly higher duodenal MTP mRNA levels than nondiabetic control subjects. The MTP gene promoter region contains a putative insulin-responsive element (38), and studies of cultured liver cells suggest that insulin and glucose reduce the expression of the MTP gene (39). In fact, several factors, including circulating FFAs and pancreatic hormones, have been demonstrated to acutely regulate intestinal lipoprotein production. Hormonal secretion is rapidly modulated in the fasted-to-fed transition and postprandial hyperglycemia coupled with GLP-1 has been shown to stimulate β-cell insulin secretion, which in turn may acutely suppress lipoprotein assembly and secretion in the liver and the intestine (40). Therefore, the discrepancies between our findings in nondiabetic insulin-resistant subjects and the findings of the studies performed in diabetics could be related to the presence of relative insulin insufficiency along with resistance in diabetic subjects that could stimulate MTP expression. In the fasted subjects with IR, the downregulation of intestinal MTP could be related to a greater inhibitory effect of insulin, whereas the oversecretion of intestinal lipoproteins observed in the constantly fed subjects with IR could reflect the fact that other factors, such as dietary lipid availability, are more important than the inhibitory effect of hyperinsulinism in determining MTP expression and lipoprotein secretion rates from the intestine.

One potential mechanism whereby IR may differentially affect intestinal gene regulation in animal models and in humans may be an adaptive response of the human enterocyte to chronic exposure to high levels of circulating FFAs and insulin. Ota, Gayet, and Ginsberg (41) have shown that modest increases in fatty acid delivery were associated with elevated secretion of apoB-100 in rat hepatocytes and C57BL/6J mice, whereas more significant fatty acid loading for a longer period of time was associated with a reduction in apoB-100 secretion and greater hepatic steatosis. Further studies will be required to assess the molecular basis for the downregulation of key intestinal genes involved in lipid metabolism in IR patients.

The current study has shown that key genes involved in cholesterol metabolism/transport (ACAT-2), fatty acid metabolism/transport (ACAC-α, SCD-1, ACS-1), and TG synthesis (DGAT-2) were downregulated in subjects with IR. This finding supports the notion that intestinal lipid absorption and de novo lipid synthesis are reduced in fasted IR subjects. Accordingly, surrogate markers of cholesterol absorption were lower in the subjects with IR than the controls. Major nuclear transcriptional factors such as SREBP-2 and HNF-4α, which are known to regulate cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis (42, 43), were also downregulated in the subjects with IR. The mechanism underlying this effect remains unclear, but it is compatible with the idea that prolonged exposure to high levels of circulating FFAs increases enterocyte TG content, leading to the inhibition of SREBP expression and the adaptive repression of intestinal de novo lipogenesis and lipid absorption.

In conclusion, the results of the present study show an overproduction of both hepatic and intestinal lipoproteins in constantly fed subjects with IR, but the expression of key genes involved in intestinal lipid and lipoprotein metabolism is significantly reduced in these subjects. These results expand our understanding of the impact of IR on intestinal lipid homeostasis in humans. Whether intestinal gene downregulation is related to relative hyperinsulinism and/or an adaptive response of the human enterocyte to chronic exposure to high levels of circulating FFAs and insulin remains unknown. Additional studies are required to further explore the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the subjects for their excellent collaboration and to the dedicated work of Danielle Aubin, Steeve Larouche, Johanne Marin, Pascal Dubé, and the staff of the Lipid Research Center.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- ACAC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- ACAT-2

- acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 2

- ACS

- acetyl-CoA synthase

- DGAT

- diacylglycerol-O-acetyltransferase

- FABP-2

- fatty acid binding protein 2

- FADS

- fatty acid desaturase

- FATP-4

- fatty acid transporter member 4

- FCR

- fractional catabolic rate

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide-1

- HDL-C

- HDL-cholesterol

- HNF-4α

- hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α HOMA-IR, homeostasis model of assessment-insulin resistance

- IDL

- intermediate density lipoprotein

- IR

- insulin resistance

- IS

- insulin-sensitive

- LDLR

- LDL receptor

- MGAT-2

- mannosyl (α-1,6-)-glycoprotein β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase-2

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- MTP

- microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- PR

- production rate

- PS

- pool size

- SAR1-β

- SAR1 homolog B

- SCD

- stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element binding protein

- TG

- triglyceride

- TRL

- triglyceride-rich lipoprotein

- VLDLR

- VLDL receptor

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (NMD-94075). P.C. is the recipient of a scholarship from Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of one table.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ginsberg H. N. 2000. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Invest. 106: 453–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duez H., Lamarche B., Uffelman K. D., Valero R., Cohn J. S., Lewis G. F. 2006. Hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased production rate of intestinal apolipoprotein B-48-containing lipoproteins in humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 1357–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duez H., Lamarche B., Valero R., Pavlic M., Proctor S., Xiao C., Szeto L., Patterson B. W., Lewis G. F. 2008. Both intestinal and hepatic lipoprotein production are stimulated by an acute elevation of plasma free fatty acids in humans. Circulation. 117: 2369–2376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duvillard L., Pont F., Florentin E., Galland-Jos C., Gambert P., Verges B. 2000. Metabolic abnormalities of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in non-insulin-dependent diabetes: a stable isotope kinetic study. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 30: 685–694 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginsberg H. N. 1987. Very low density lipoprotein metabolism in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Rev. 3: 571–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogue J. C., Lamarche B., Tremblay A. J., Bergeron J., Gagné C., Couture P. 2007. Evidence of increased secretion of apolipoprotein B-48-containing lipoproteins in subjects with type 2 diabetes. J. Lipid Res. 48: 1336–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNamara J. R., Shah P. K., Nakajima K., Cupples L. A., Wilson P. W., Ordovas J. M., Schaefer E. J. 2001. Remnant-like particle (RLP) cholesterol is an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor in women: results from the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 154: 229–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mero N., Syvanne M., Eliasson B., Smith U., Taskinen M. R. 1997. Postprandial elevation of ApoB-48-containing triglyceride-rich particles and retinyl esters in normolipemic males who smoke. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17: 2096–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolovou G. D., Anagnostopoulou K. K., Daskalopoulou S. S., Mikhailidis D. P., Cokkinos D. V. 2005. Clinical relevance of postprandial lipaemia. Curr. Med. Chem. 12: 1931–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adeli K., Lewis G. F. 2008. Intestinal lipoprotein overproduction in insulin-resistant states. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 19: 221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy E., Spahis S., Ziv E., Marette A., Elchebly M., Lambert M., Delvin E. 2006. Overproduction of intestinal lipoprotein containing apolipoprotein B-48 in Psammomys obesus: impact of dietary n-3 fatty acids. Diabetologia. 49: 1937–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lally S., Owens D., Tomkin G. H. 2007. Genes that affect cholesterol synthesis, cholesterol absorption, and chylomicron assembly: the relationship between the liver and intestine in control and streptozotosin diabetic rats. Metabolism. 56: 430–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lally S., Owens D., Tomkin G. H. 2007. The different effect of pioglitazone as compared to insulin on expression of hepatic and intestinal genes regulating post-prandial lipoproteins in diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 193: 343–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris J., Benedict F. 1919. A Biometric Study of Basal Metabolism in Man. Carnegie Institution, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havel R. J., Eder H., Bragdon J. 1955. The distribution and chemical composition of ultracentrifugally separated lipoproteins in human serum. J. Clin. Invest. 34: 1345–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albers J. J., Warnick G. R., Wiebe D., King P., Steiner P., Smith L., Breckenridge C., Chow A., Kuba K., Weidman S., et al. 1978. Multi-laboratory comparison of three heparin-Mn2+ precipitation procedures for estimating cholesterol in high-density lipoprotein. Clin. Chem. 24: 853–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthan N. R., Giovanni A., Schaefer E. J., Brown B. G., Lichtenstein A. H. 2003. Impact of simvastatin, niacin, and/or antioxidants on cholesterol metabolism in CAD patients with low HDL. J. Lipid Res. 44: 800–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desbuquois B., Aurbach G. D. 1971. Use of polyethylene glycol to separate free and antibody-bound peptide hormones in radioimmunoassays. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 33: 732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richterich R., Dauwalder H. 1971. Determination of plasma glucose by hexokinase-glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 101: 615–618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heding L. G. 1975. Radioimmunological determination of human C-peptide in serum. Diabetologia. 11: 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vilsbøll T., Krarup T., Sonne J., Madsbad S., Vølund A., Juul A. G., Holst J. J. 2003. Incretin secretion in relation to meal size and body weight in healthy subjects and people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88: 2706–2713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews D. R., Hosker J. P., Rudenski A. S., Naylor B. A., Treacher D. F., Turner R. C. 1985. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 28: 412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotite L., Bergeron N., Havel R. J. 1995. Quantification of apolipoproteins B-100, B-48, and E in human triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 36: 890–900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welty F. K., Lichtenstein A. H., Barrett P. H., Dolnikowski G. G., Schaefer E. J. 1999. Human apolipoprotein (Apo) B-48 and ApoB-100 kinetics with stable isotopes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19: 2966–2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dwyer K. P., Barrett P. H., Chan D., Foo J. I., Watts G. F., Croft K. D. 2002. Oxazolinone derivative of leucine for GC-MS: a sensitive and robust method for stable isotope kinetic studies of lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 43: 344–349 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cobelli C., Toffolo G., Bier D. M., Nosadini R. 1987. Models to interpret kinetic data in stable isotope tracer studies. Am. J. Physiol. 253: E551–E564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tremblay A. J., Lamarche B., Hogue J. C., Couture P. 2009. Effects of ezetimibe and simvastatin on apolipoprotein B metabolism in males with mixed hyperlipidemia. J. Lipid Res. 50: 1463–1471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tremblay A. J., Lamarche B., Guay V., Charest A., Lemelin V., Couture P. 2013. Short-term, high-fat diet increases the expression of key intestinal genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism in healthy men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98: 32–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altmann S. W., Davis H. R., Jr, Zhu L. J., Yao X., Hoos L. M., Tetzloff G., Iyer S. P., Maguire M., Golovko A., Zeng M., et al. 2004. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science. 303: 1201–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haidari M., Leung N., Mahbub F., Uffelman K. D., Kohen-Avramoglu R., Lewis G. F., Adeli K. 2002. Fasting and postprandial overproduction of intestinally derived lipoproteins in an animal model of insulin resistance. Evidence that chronic fructose feeding in the hamster is accompanied by enhanced intestinal de novo lipogenesis and ApoB48-containing lipoprotein overproduction. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 31646–31655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zoltowska M., Ziv E., Delvin E., Lambert M., Seidman E., Levy E. 2004. Both insulin resistance and diabetes in Psammomys obesus upregulate the hepatic machinery involved in intracellular VLDL assembly. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 118–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoltowska M., Ziv E., Delvin E., Sinnett D., Kalman R., Garofalo C., Seidman E., Levy E. 2003. Cellular aspects of intestinal lipoprotein assembly in Psammomys obesus: a model of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 52: 2539–2545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vine D. F., Takechi R., Russell J. C., Proctor S. D. 2007. Impaired postprandial apolipoprotein-B48 metabolism in the obese, insulin-resistant JCR:LA-cp rat: increased atherogenicity for the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 190: 282–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasase T., Morinaga H., Yamamoto H., Ogawa N., Matsui K., Miyajima K., Kawai T., Mera Y., Masuyama T., Shinohara M., et al. 2007. Increased fat absorption and impaired fat clearance cause postprandial hypertriglyceridemia in spontaneously diabetic Torii rat. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 78: 8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tremblay A. J., Lamarche B., Lemelin V., Hoos L., Benjannet S., Seidah N. G., Davis H. R., Jr, Couture P. 2011. Atorvastatin increases intestinal expression of NPC1L1 in hyperlipidemic men. J. Lipid Res. 52: 558–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veilleux A., Grenier É., Carpentier A., Richard A., Levy É. 2012. Alteration in intestinal insulin signaling in obese subjects and their effect on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Diabetes. 61 (Suppl. 1): A15 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips C., Mullan K., Owens D., Tomkin G. H. 2006. Intestinal microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic subjects: the relationship to triglyceride-rich postprandial lipoprotein composition. Atherosclerosis. 187: 57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagan D. L., Kienzle B., Jamil H., Hariharan N. 1994. Transcriptional regulation of human and hamster microsomal triglyceride transfer protein genes. Cell type-specific expression and response to metabolic regulators. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 28737–28744 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin M. C., Gordon D., Wetterau J. R. 1995. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) regulation in HepG2 cells: insulin negatively regulates MTP gene expression. J. Lipid Res. 36: 1073–1081 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pavlic M., Xiao C., Szeto L., Patterson B. W., Lewis G. F. 2010. Insulin acutely inhibits intestinal lipoprotein secretion in humans in part by suppressing plasma free fatty acids. Diabetes. 59: 580–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ota T., Gayet C., Ginsberg H. N. 2008. Inhibition of apolipoprotein B100 secretion by lipid-induced hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 118: 316–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. 1997. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell. 89: 331–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horton J. D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. 2002. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 109: 1125–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.