Abstract

Background

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is a potential partner treatment strategy. Significant efforts have been devoted to policies intended to facilitate its practice. However, few studies have attempted to evaluate these policies.

Methods

We used data on interviewed gonorrhea cases from 12 sites in the STD Surveillance Network (SSuN) in 2010 (n=3,404). Patients reported whether they had received EPT. We coded state laws relevant to EPT for gonorrhea using Westlaw legal research database, and the general legal status of EPT in SSuN sites from CDC’s website in 2010. We also coded policy statements by medical and other boards. We used chi-squares to compare receipt of EPT by legal/policy variables, patient characteristics and provider type. Variables significant at p<.10 in bivariate analyses were included in a logistic regression model.

Results

Overall, 9.5% of 2,564 interviewed gonorrhea patients reported receiving EPT for their partners. Receipt of EPT was significantly higher where laws and policies authorizing EPT existed. Where EPT laws for GC existed and EPT was permissible, 13.3% of patients reported receiving EPT as compared to 5.4% where there were no EPT laws and EPT was permissible, and 1.0% where there were no EPT laws and EPT was potentially allowable (p<.01). EPT was higher where professional boards had policy statements supporting EPT (p<.01). Receipt of EPT did not differ by most patient characteristics or provider type. Policy-related findings were similar in adjusted analyses.

Conclusions

EPT laws and policies were associated with higher reports of receipt of EPT among interviewed gonorrhea cases.

Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is a partner management technique where medications or prescriptions are provided to the partner of a patient who tests positive for chlamydia or gonorrhea without physical examination of the partner. EPT can reduce chlamydia and gonorrhea reinfection [1–4] and is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other medical and legal organizations. [5–8] Given the effectiveness of EPT in reducing sexually transmitted disease (STD) reinfections and the low risk of side effects associated with its use [9], policy efforts have focused on facilitating its practice. To serve as a resource for providers, Hodge and colleagues analyzed state laws and policies relevant to EPT, categorizing the probable legal status of EPT for treating any STD in each state as: permissible, potentially allowable, or prohibited. [10] The primary factors considered were state statutes (laws passed by the legislature), regulations (promulgated by state departments of health or professional licensure boards), and policy statements by state professional licensure boards supporting its practice. This resulted in a “comparative snapshot of legal provisions that may highlight legislative, regulatory, judicial laws and policies concerning EPT.” [11]

Research has evaluated various aspects of EPT. One study found that EPT is routinely utilized by family planning providers in California, and that the vast majority of these providers feel that it improves care. [12] Additionally, rates of partner treatment are higher for both concurrent treatment visits (patient and partner treated concurrently) and EPT as compared to standard patient referral. [13] EPT is cost-effective in certain situations [14], and changes to clinic policies requiring documentation of EPT have been shown to increase EPT’s acceptance. [15] Lastly, provider knowledge of EPT is associated with higher rates of practice, yet practice is inhibited by concern for legal liability. [16] Concern for liability exists because EPT involves prescribing and dispensing medications to individuals who have not been physically examined by a healthcare provider. Potential legal actions include medical malpractice lawsuits from individuals or censure from state professional licensure boards. [10]

Concern for legal liability is considered one of the primary impediments to the practice of EPT [10], and despite policy initiatives intended to clarify its legal status, the effect of these laws and policies on the provision of EPT has not been evaluated. Therefore, this study investigates the relationship between laws and policies and the practice of EPT by comparing the receipt of EPT by gonorrhea patients in Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance Network (SSuN) participating sites across states of varying legal environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

We used several sources to assess the relationship between legal and policy aspects of EPT and receipt of EPT among reported cases of gonorrhea in the United States (U.S.). For the legal and policy variables, we used the Westlaw legal research database (Thompson Reuters, New York, NY) and the probable legal status for each state as listed on CDC’s website to categorize states. [11] These data were merged with data collected in 2010 from the 12-site SSuN, which includes STD programs in health departments in the four U.S. Census regions (Figure 1). Each site interviewed a random sample of individuals diagnosed with gonorrhea from cases reported to the health department. Cases were randomly assigned into the sample when entered into the surveillance system or were randomly selected from the reported cases weekly or biweekly. All sites include at least one county (refer to Figure 1 for a list of counties), and cases were eligible for sampling if reported within 30 days of diagnosis. Interviews were conducted by telephone and respondents were asked a series of questions about their gonorrhea diagnosis.

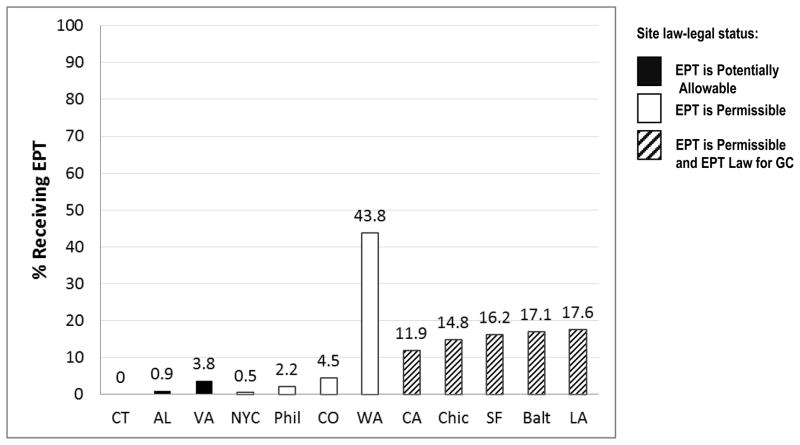

Figure 1. Receipt of EPT among interviewed gonorrhea patients by SSuN site, 2010. (n=2564)*.

Counties sampled by site include: Alabama, Jefferson County (AL); Baltimore, Baltimore City (Balt); California, all counties excluding San Francisco County (CA)†; Chicago, Cook County (Chic); Colorado, Adams, Arapahoe and Denver counties (CO); Connecticut, Hartford and New Haven counties (CT); Louisiana, Orleans Parish (LA); Philadelphia, Philadelphia County (Phil); New York City, Kings, Queens, Bronx, Richmond, New York counties (NYC); San Francisco, San Francisco County (SF); Virginia, Chesterfield and Henrico counties and Richmond City (VA); Washington, all counties (WA).

*Data were weighted for site sampling fraction and non-response.

†California and San Francisco are independently funded and operated SSuN sites.

Measures

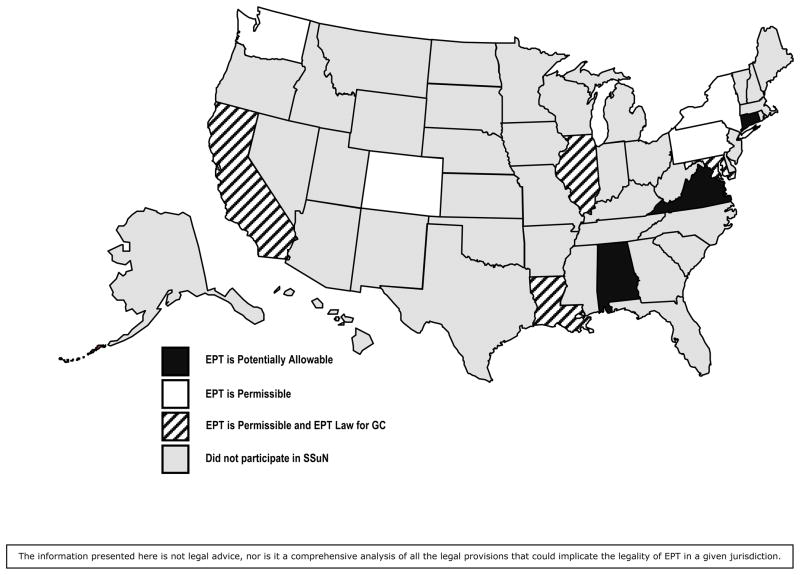

We used three measures to assess the legal and policy aspects of EPT as of January 1, 2010: 1) a combined variable of the general determination of state legal status for EPT as shown on CDC’s website (based on legal research conducted by Hodge and colleagues [10]) and state laws that explicitly authorize EPT for gonorrhea (law-legal status); 2) state medical board statements relevant to EPT; and 3) state non-medical board (e.g., pharmacy board) statements relevant to EPT. Using EPT laws specific to gonorrhea from Westlaw, and the probable legal status of EPT as displayed on CDC’s website, we coded the primary legal variable, law-legal status, into the following categories: 1) has law authorizing EPT for gonorrhea and is listed as permissible on CDC website (GC EPT law & CDC permissible); 2) does not have law authorizing EPT for gonorrhea but is listed as permissible on CDC’s website (No GC EPT law & CDC permissible); and 3) does not have law authorizing EPT for gonorrhea and is listed as potentially allowable on CDC’s website (No GC EPT law & CDC potentially allowable) (Figure 2). We used the legal status of EPT as shown on CDC’s website as a measure of the general legal context of EPT for each state. We considered only those authorities that carry the force of law (e.g. statutes and regulations) to be “laws” for this variable.

Figure 2. Legal status of EPT for gonorrhea by SSuN site as of January 1, 2010.

This map represents a combination of the legal status of EPT displayed on CDC’s website and whether a state had a law explicitly legalizing EPT for gonorrhea. This study examined data from Baltimore City only. For legibility, the coding used for Maryland is based on Baltimore law. Furthermore, Baltimore’s laws apply only to STD clinics within Baltimore City.

We also coded policy variables indicating whether a state medical board or other non-medical board had released a policy statement that would influence the provision of EPT. While these policy statements do not carry the force of law, they are nonetheless presumptive of the legal status of EPT in a state and provide a strong indication of the likelihood that a board would censure a licensee for practicing EPT. For our purposes, “non-medical board” meant any professional board or organization other than the entity responsible for licensing physicians, including entities such as boards of pharmacy and state medical associations. The policy statement variables were coded as 1) yes, statement prohibits EPT; 2) yes, statement permits EPT; and 3) no statement influencing EPT. EPT laws and policies did not change during the study period in any SSuN site.

Our outcome of interest was receipt of EPT. As part of the SSuN interviews, gonorrhea patients were asked if they were given medication or a prescription for their sex partners using the following response options: 1) no; 2) no, partner(s) was already treated; and 3) yes. Respondents who reported that their partner(s) was already treated were considered ineligible for EPT; therefore, our final outcome measure was dichotomous (yes/no). One site (San Francisco) used different coding (yes/missing) for this variable that we recoded as yes/no; therefore, our estimate of EPT in this site should be interpreted as a minimum estimate.

Additionally, SSuN interviews with gonorrhea patients collected information on patient characteristics and provider type. Demographics examined in our analysis included patient age (limited to 15–59 year olds), race/ethnicity, education, gender/sexual behavior (women; men who have sex with men, MSM; men who have sex with women, MSW), and recent incarceration history (past 12 months). Although EPT is not routinely recommended for MSM because it might inhibit diagnosis and treatment of coexisting infections [5], our purpose was to examine the actual implementation of EPT in areas with different legal environments rather than evaluating adherence to CDC guidelines. Therefore, we included MSM in our analyses. Additionally, respondents were asked about other STDs (previous gonorrhea diagnosis in past 12 months and co-infection with chlamydia during current gonorrhea diagnosis), and were asked if they had used crack cocaine or methamphetamines in the past 12 months. Respondents reported their number of sex partners in past 3 months and were asked several questions about sexual risk in the past 12 months including: had anonymous sex partner, met sex partner on internet, exchanged sex for money/drugs, and had partner who had been in jail/prison recently. Type of healthcare provider where gonorrhea was diagnosed was also included in the analyses.

Statistical Analyses

We used SAS (Release 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for analyses. Specifically, the SURVEY procedures were used to 1) adjust and account for the complex sample design (e.g., clustering by county) and 2) weight data for site sampling fraction and non-response (by age, gender, provider type). Our law-legal status variable was highly correlated with our two policy variables (policies were included in the general legal status displayed on CDC’s website); therefore, we assessed the relationship between these variables and our outcome separately. We used chi-square tests for bivariate analyses. Variables significant at p<.10 in bivariates were included in an adjusted logistic regression model. We conducted two post-hoc analyses excluding MSM and Washington (state-wide effort to promote EPT) separately, to see if our findings were the same without either group. Finally, in the seven SSuN sites that did not have a law authorizing EPT for gonorrhea, we used the chi-square test of independence to assess the relationship of each policy variable (state medical board and other non-medical board policy statement) to the receipt of EPT. These estimates were unstable (relative standard errors were > 30%); therefore, we did not include these variables in adjusted models.

RESULTS

In 2010, 3,404 interviews with selected gonorrhea patients were completed with a response rate of 39%. Among the sample, 2,564 patients responded to the receipt of EPT question and were considered eligible to receive EPT. Overall, 9.5% of eligible gonorrhea patients reported receiving EPT for their sex partners. Receipt of EPT was highest in Washington state where 43.8% of eligible gonorrhea patients reported receipt of EPT and lowest in Connecticut where no eligible gonorrhea patients reported receipt of EPT. Five sites reported receipt of EPT by less than 5% of gonorrhea patients; the remaining five reported receipt by 10–20% of gonorrhea patients (Figure 1).

Bivariate Analyses

The law-legal status variable was significantly associated with the receipt of EPT (p<.01) (Table 1). EPT was received by gonorrhea patients more often in jurisdictions that have a GC EPT law and where EPT is considered permissible (13.3%) than in jurisdictions that do not have an EPT law and where EPT is considered permissible (5.4%), as well as in jurisdictions that do not have an EPT law and where EPT is considered potentially allowable (1.0%). Several demographic variables also met our criteria for inclusion in our adjusted model. In terms of race/ethnicity, white gonorrhea patients had the highest reported receipt of EPT (12.4%), followed by blacks (9.7%), Hispanics (5.9%), and other racial/ethnic groups (14.4%, p=.06). The receipt of EPT also differed based on the gender of the patient’s sex partner, with MSM receiving EPT 7.5% of the time, MSW receiving EPT 5.8% of the time, and women receiving EPT 13.7% of the time (p<.01). Lastly, patients who had a recently incarcerated sex partner (past 12 months) had higher reports of receiving EPT (13.7%) than those not having such a partner (8.7%, p=.07).

Table 1.

Receipt of EPT among interviewed gonorrhea cases by site legal status, patient characteristics and provider type (n=2564): Bivariate and adjusted analyses

| Correlates | Bivariate Analyses

|

Adjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N | Weighted % (SE) | P value | ||

| Legal/policy issues | ||||

| Site law-legal status | <.01 | |||

| GC EPT law & CDC permissible | 1201 | 13.3% (3.3) | 23.2 (6.0–89.8) | |

| No GC EPT law & CDC permissible | 984 | 5.4% (2.1) | 7.3 (1.7–30.7) | |

| No GC EPT law & CDC potentially allowable | 379 | 1.0% (0.5) | 1.0 | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | .94 | -- | ||

| 15–19 | 597 | 8.0% (3.2) | ||

| 20–24 | 810 | 9.7% (2.7) | ||

| 25–34 | 691 | 8.9% (2.0) | ||

| 35–59 | 400 | 8.4% (2.9) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .06 | |||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 495 | 12.4% (2.7) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 1414 | 9.7% (2.6) | 1.0 | |

| Hispanic | 458 | 5.9% (2.1) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | |

| Other | 152 | 14.4% (4.1) | 1.5 (0.7–2.9) | |

| Education level | .27 | -- | ||

| < high school | 551 | 9.0% (3.4) | ||

| High school/GED | 809 | 7.2% (2.1) | ||

| Some college | 681 | 10.3% (2.6) | ||

| College or higher | 315 | 5.3% (2.1) | ||

| Incarcerated (past 12 months) | .96 | -- | ||

| No | 2266 | 9.3% (2.0) | ||

| Yes | 253 | 9.5% (4.0) | ||

| Gender/sexual behavior | .01 | -- | ||

| Men | ||||

| MSM | 620 | 7.5% (2.7) | 0.3 (0.2–0.7) | |

| MSW | 734 | 5.8% (1.9) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | |

| Women | 1190 | 13.7% (3.2) | 1.0 | |

| Previous gonorrhea diagnosis (past 12 months) | .55 | -- | ||

| No | 2114 | 8.6% (2.0) | ||

| Yes | 286 | 10.8% (4.4) | ||

| Co-infected with chlamydia | .76 | -- | ||

| No | 1352 | 13.0% (3.2) | ||

| Yes | 616 | 12.1% (2.6) | ||

| Number of sex partners (past 3 months) | .81 | -- | ||

| 1 partner | 1184 | 10.6% (2.8) | ||

| 2 partners | 617 | 9.1% (3.3) | ||

| 3 or more partners | 623 | 8.5% (2.9) | ||

| Had anonymous sex partner (past 12 months) | .68 | -- | ||

| No | 1936 | 9.9% (2.5) | ||

| Yes | 445 | 7.7% (4.3) | ||

| Met sex partner via Internet (past 12 months) | .72 | -- | ||

| No | 1866 | 7.5% (1.9) | ||

| Yes | 330 | 6.6% (2.9) | ||

| Exchanged sex for $/drugs (past 12 months) | .73 | -- | ||

| No | 2358 | 9.5% (2.2) | ||

| Yes | 70 | 8.2% (4.2) | ||

| Had recently incarcerated partner (past 12 months) | .07 | |||

| No | 2098 | 8.7% (2.1) | 1.0 | |

| Yes | 272 | 13.7% (4.9) | 1.1 (0.6–1.7) | |

| Used crack cocaine (past 12 months) | .88 | -- | ||

| No | 2343 | 9.1% (2.1) | ||

| Yes | 81 | 8.8% (2.9) | ||

| Used methamphetamines (past 12 months) | .99 | -- | ||

| No | 2323 | 9.1% (2.1) | ||

| Yes | 101 | 9.1% (4.2) | ||

| Provider type | .42 | -- | ||

| STD clinic | 716 | 9.7% (4.0) | ||

| Reproductive health (FP/GYN) | 369 | 15.2% (5.9) | ||

| ER/urgent care | 247 | 7.6% (2.7) | ||

| Hospital other | 277 | 6.2% (2.2) | ||

| HMO/private | 394 | 6.0% (1.6) | ||

| Public/community health center | 222 | 9.0% (3.6) | ||

| Other | 252 | 11.8% (3.6) | ||

Note. GC = gonorrhea. MSM = men who have sex with men. MSW = men who have sex with women. Past 3 months refers to the 3 months prior to current gonorrhea diagnosis. Among women, there was no difference in receipt of EPT by pregnancy status. N adjusted analyses = 2323.

Among states that do not have a law authorizing EPT for GC, the receipt of EPT differed based on state medical board or other non-medical board policy statements relevant to EPT (Table 2). In states with medical board policy statements permitting EPT, gonorrhea patients received EPT at a significantly higher rate (24.4%) than in states with medical board policy statements prohibiting EPT (0%) and states without a medical board policy statement (1.1%, p<.01). Similar results were found for non-medical board policy statements. In states with non-medical board policy statements permitting EPT, gonorrhea patients received EPT at a significantly higher rate (24.4%) than in states with non-medical board policy statements prohibiting EPT (3.8%) and states without a non-medical board policy statement (1.0%, p<0.1). Washington implemented an extensive state-wide effort to increase EPT uptake among providers; therefore, we also examined policy variables excluding this site. The significant differences remained (p<.01) but the percentage who received EPT dropped to 4.5% where state medical and non-medical boards had statements permitting EPT.

Table 2.

Receipt of EPT among interviewed gonorrhea cases by board opinions: SSuN sites without law authorizing EPT for gonorrhea

| Policy variables | Bivariate Analyses

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted N | Weighted % (SE) | P value | |

| All 7 sites (n=1363) | |||

| State medical board opinion+ | <.01 | ||

| Yes, prohibits | 0 | 0 | |

| Yes, permits | 448 | 24.4% (10.1)* | |

| No | 915 | 1.1% (0.4)* | |

| Other non-medical board opinion† | <.01 | ||

| Yes, prohibits | 115 | 3.8% (0.8) | |

| Yes, permits | 448 | 24.4% (10.1)* | |

| No | 800 | 1.0% (0.4)* | |

| 6 sites without a state-wide effort to promote EPT (n=1124) | |||

| State medical board opinion† | <.01 | ||

| Yes, prohibits | 0 | 0 | |

| Yes, permits | 209 | 4.5% (0.5) | |

| No | 915 | 1.1% (0.4)* | |

| Other non-medical board opinion† | <.01 | ||

| Yes, prohibits | 115 | 3.8% (0.8) | |

| Yes, permits | 209 | 4.5% (0.5) | |

| No | 800 | 1.0% (0.4)* | |

Board rulings defined as “prohibit” did not refer directly to EPT.

Estimate is unstable: relative standard error is > 30%.

Multiple Logistic Regression Models

In adjusted analyses, gonorrhea patients in states that have an EPT law and where EPT is considered permissible (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 23.2 [95% CI, 6.0–89.8]) and states that do not have an EPT law but where EPT is considered permissible (AOR, 7.3 [95% CI, 1.7–30.7]) were more likely to have received EPT than gonorrhea patients in states without a law and where EPT is potentially allowable (Table 1). Of the demographic variables included in the model, gender of sex partners was the only variable that remained statistically significant in adjusted analysis. MSW were less likely to receive EPT than women (AOR, 0.4 [95% CI, 0.2–0.8]), as were MSM (AOR, 0.3 [95% CI, 0.2–0.70]). Race/ethnicity and having a recently incarcerated partner (past 12 months) were not significant in adjusted analyses.

Finally, we conducted two additional analyses to determine if findings were the same when separately excluding 1) MSM and 2) Washington (data not shown in tables). When excluding MSM, the findings for the law-legal status variable, gender of sex partners, and having an incarcerated partner in the past 12 months were similar to results from the overall model; however, we found one difference in that non-Hispanic whites (AOR, 2.1 [95% CI, 1.1–4.1]) were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic blacks to have received EPT. When excluding Washington, the only finding that was not similar to the overall model was that gonorrhea patients in states that do not have an EPT law but where EPT is considered permissible (AOR, 1.9 [95% CI, 0.5–7.6]) did not differ from patients in sites without a law and where EPT is considered potentially allowable.

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that laws and policies authorizing EPT are associated with higher reports of receipt of EPT among gonorrhea patients when adjusting for patient and provider variables associated with EPT. While this is the first study to evaluate the relationship between laws and EPT by comparing uptake across states of varying legal environments, our findings are consistent with evaluations of EPT uptake within jurisdictions that have laws authorizing EPT. [12] Potential explanations include the possibility that laws authorizing EPT may diminish provider concern for legal liability, as such laws explicitly make the practice of EPT legal within a jurisdiction. Uptake is also higher in jurisdictions where EPT is deemed permissible versus those in which it is potentially allowable, notwithstanding the existence of an EPT law. However, in adjusted analyses, these findings were only observed when the site with an intensive state-wide effort to promote the use of EPT (Washington) was included.

This study found that having a law or a regulation authorizing EPT was associated with higher receipt of EPT. However, in states where such laws or regulations do not exist, our findings suggest that professional licensure board policy statements are related to an increase in the receipt of EPT, as the receipt of EPT was significantly higher in states with policy statements endorsing EPT, even when excluding Washington. It should be noted, however, that board policy statements do not carry the force of law as statutes and regulations do; policy statements are nevertheless highly presumptive of boards’ priorities in terms of regulating healthcare professionals.

It is worth noting that receipt of EPT was low overall with fewer than 1 in 10 gonorrhea patients reporting that they received it. While receipt of EPT for gonorrhea was higher within jurisdictions with laws authorizing EPT for gonorrhea, it was still relatively low in these areas. Thus, while laws may alleviate provider concerns with dispensing medication without a physical examination, other possible barriers to the use of EPT may remain. Among providers, awareness of EPT and reimbursement issues may inhibit EPT use even in supportive legal environments. Furthermore, technological advancements like electronic health records, may optimize the practice of EPT. [15] Finally, it is possible that uptake of new strategies may take several years; therefore, future research should examine the time since a law took effect and health department and other organizations’ efforts to increase the use of EPT.

There are some limitations to our analysis. First, our findings may not be generalizable to gonorrhea patients across the U.S. given that only 12 sites participated in SSuN (accounting for approximately 20% of U.S. gonorrhea cases), and the response rate was low (39%). Additionally, the number of sites produced limited legal environment variation. The second limitation is that this study analyzes the receipt of EPT among gonorrhea patients, yet it has been suggested that EPT is more commonly provided to chlamydia patients. This limitation was due to the lack of available data on the receipt of EPT for chlamydia; future studies should investigate this issue as such data becomes available. Additionally, given increasing antimicrobial resistance, in 2012, CDC amended its guidance concerning EPT for gonorrhea stating “if a heterosexual partner of a patient cannot be linked to evaluation and treatment in a timely fashion, then expedited partner therapy should be considered, using oral combination antimicrobial therapy for gonorrhea…”. [17] Thus, the receipt of EPT for gonorrhea may have changed since the time of data collection, and concerns regarding susceptibility to oral cephalosporins may limit the practice of EPT for gonorrhea moving forward. Third, this study is not a randomized controlled trial; causality cannot be inferred from our results. Lastly, it is possible that states with providers more receptive to EPT are more likely to pass a law. Thus, the receipt of EPT itself could cause a legal environment more amendable to EPT, rather than the legal environment facilitating its practice. Additionally, it is possible that health departments may more actively promote the use of EPT in states that pass laws.

The results of this analysis show that, within our sample, individuals with gonorrhea in jurisdictions that have an EPT law, and to a lesser degree, jurisdictions where EPT is considered legally permissible, are significantly more likely to receive EPT as a treatment option. Similarly, in those jurisdictions without an EPT law, EPT was practiced at a significantly higher rate in jurisdictions with a medical or non-medical board that supports its practice. For jurisdictions wanting to increase the receipt of EPT, this study suggests that laws and policies may be effective options for doing so.

Summary.

Based on interviewed gonorrhea cases in the STD Surveillance Network, laws and policies authorizing EPT were associated with higher reports of receipt of EPT.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement number PS08-865, Data collection in Washington State also supported in part by NIH, NIAID R01A068107).

This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: a randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:49–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trelle S, Shang A, Nartey L, et al. Improved effectiveness of partner notification for patients with sexually transmitted infections: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;334(7589):354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39079.460741.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kissinger P, Mohammed H, Richardson-Alston G, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment for male urethritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:623–9. doi: 10.1086/432476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2010. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Accessed April 14, 2012]. Accessible at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2010/toc.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider JF. [Accessed April 13, 2012];Expedited Partner Therapy (Patient-delivered Partner Therapy): An Update. 2006 Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/csaph/a06csaph7-fulltext.pdf.

- 7. [Accessed April 13, 2012];Expedited Partner Therapy in the Management of Gonorrhea and Chlamydia by Obstetrician-Gynecologists. 2011 Sep; doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310cee. Available at: http://www.acog.org/~/media/Committee%20Opinions/Committee%20on%20Adolescent%20Health%20Care/co506.ashx?dmc=1&ts=20111207T1406092727. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. [Accessed April 14, 2012];American Bar Association Recommendation 116A. 2008 Aug 12; Available at: http://www.abanet.org/leadership/2008/annual/adopted/OneHundredSixteenA.doc.

- 9.Handsfield HH, Hogben M, Schillinger JA, et al. [Accessed April 16, 2012];Expedited Partner Therapy in the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/EPTFinalReport2006.pdf.

- 10.Hodge JG, Pulver A, Hogben M, et al. Expedited Partner Therapy for Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Assessing the Legal Environment. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):238–243. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed April 13, 2012];Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy. 2012 Feb 9; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm.

- 12.Jotblad S, Park IU, Bauer HM, et al. Patient-delivered partner therapy for chlamydial infections: practices, attitudes, and knowledge of California family planning providers. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(2):122–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318237b723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Y, Frasure-Williams JA, Dunne EF, et al. Chlamydia partner services for females in California family planning clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:913–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182240366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gift TL, Kissinger P, Mohammed H, et al. The cost and cost-effectiveness of expedited partner therapy compared with standard partner referral for the treatment of chlamydia or gonorrhea. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38:1067–73. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e9192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mickiewicz T, Al-Tayyib A, Thrun M, et al. Implementation and Effectiveness of an Expedited Partner Therapy Program in an Urban Clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:923–929. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182756f20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor MM, Collier MG, Winscott MM, et al. Reticence to prescribe: utilization of expedited partner therapy among obstetrics providers in Arizona. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(8):449–52. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2011.010492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) Update to CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines, 2010: Oral Cephalosporins No Longer a Recommended Treatment for Gonococcal Infections. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Accessed September 17, 2012]. Accessible at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6131a3.htm?s_cid=mm6131a3_w. [Google Scholar]