Abstract

Objective

To compare three groups of MSM—men who had attended a sex party in the past year (45.2%); men who had been to a sex party more than a year ago (23.3%); and men who had never been to one (31.5%)—on socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics.

Method

In spring 2012, 2,063 sexually active MSM in the U.S. were recruited using banner advertising on a sexual networking website to complete an online survey about their sexual behavior and attendance at sex parties.

Results

A significantly higher proportion of past year attendees were HIV-positive (28.1%), single (31.7%), demonstrated sexual compulsivity symptomology (39.2%), recently used drugs (67.8%), averaged the greatest number of recent male partners (Mdn=15, <90 days), and greater instances of recent unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) with male partners (Mdn=3, <90 days). Adjusting for covariates, those having been to a sex party in the last year were significantly more likely than others to report UAI. Free lubricant (93.4%) and condoms (81.0%) were the most desirable services/products men wanted at sex parties. More than half of men having been to a sex party expressed interest in free rapid HIV testing at sex parties (52.8%); however, few considered it acceptable to see “medical providers” (11.7%) and “peer outreach workers” (9.5%) at sex parties.

Conclusions

MSM who have attended a sex party in the last year are appropriate candidates for targeted HIV and STI prevention. Collaborating with event promoters presents valuable opportunities to provide condoms, lubricant, and HIV/STI testing.

Keywords: Sex parties, men who have sex with men, unprotected anal intercourse, gay and bisexual men, substance use

INTRODUCTION

In the United States the U.S., men who have sex with men (MSM) accounted for 63% of new HIV diagnoses in 2010.1 Researchers have recognized the role that venues where MSM meet their sex partners play in influencing HIV/STI risk as well as the need to locate prevention services within venues.2–4 Specifically, studies have investigated the role sex parties play in risk behaviors among MSM,5–10 suggesting that sex party attendance may be common and that men who attend them may be at higher risk for HIV/STIs. One study of urban MSM reported that 25% recently attended a sex party and that these men had higher rates of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI),3 and another noted that HIV-positive MSM were more likely to have attended sex parties than HIV-negative men.5 A survey of gym-attending MSM reported that 23% attended a sex party in the previous six months and 8% had attended a bareback sex party.11 In comparison, a 2011 study of young MSM found that 8.7% had recently attended a sex party; they reported higher numbers of male sex partners and were more likely to report drug use than men who had not attended sex parties.9 These findings highlight variability in the proportion of MSM who attend sex parties, suggesting that more work is needed to determine the prevalence of sex party attendance and whether there are there are demographic and behavioral differences between men who do and do not attend.

Sex parties can have themes that may impact behavior. For example, themes around HIV status,6 kink,6,9 and barebacking11 have been described, and these themes may be differentially associated with HIV risk. As such, more research is needed to characterize the full range of sex party themes and describe their prevalence. Additionally, there are insufficient data on the acceptability and feasibility of varying types of prevention/outreach approaches within sex parties, which limits the development of tailored HIV/STI prevention techniques.

We sought to address these gaps by focusing on a national online sample of MSM. We describe the prevalence and patterns of various multiple partner encounters. Second, we compared socio-demographic and behavioral differences between men who had attended sex parties in the last year, more than a year ago, and had never attended a sex party. Third, we examined the associations of UAI with sex party attendance and other HIV/STI transmission risk factors. We describe the acceptability of HIV/STI prevention, education, and services at sex parties.

METHOD

Participants and procedures

For one month in spring 2012, the research team advertised on a popular, free sexual networking website for MSM. Those clicking the ad were redirected to our survey, which took approximately 10 minutes to complete. The survey screened participants for other, paid studies, though this online survey had no incentive itself.12 Procedures were approved by the CUNY Institutional Review Board.

The ad was clicked 10,900 times. Thirty-one percent (n=3,334) provided informed consent and began the survey; the remainder closed their browsers. Eleven men were younger than 18 and ineligible. Of the remaining 3,323 who provided informed consent, 2,287 (68.8%) completed the survey. From these, we excluded the following: 108 individuals (4.7%) outside the US; four (0.1%) born biologically female; 15 (0.7%) not male-identified; 79 (3.5%) who reported no sex with men in the last 90 days; 18 surveys (0.8%) suspect of being duplicates (same IP address or computer metadata), and one man who did not indicate his sexual identity. The final sample included 2,063 sexually active MSM in the US (90% of completed surveys).

Measures

Sex with multiple partners

Participants were presented with sexual scenarios involving multiple partners. Items included threesomes as well as themed/organized sex events. Items are presented in Table 1. Response options included “No, never,” “Yes, but not within the last 12 months,” and “Yes, within the last 12 months.” Those who had ever participated in group sex (i.e., items 4 through 20 in Table 1) were asked to indicate how many sex parties they attended in the previous year.

Table 1.

Participation in different types of multiple partner sexual encounters

| No, Never | Yes, but not within the last 12 months | Yes, within the last 12 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Threesome encounters | ||||||

| 1 Had a threesome (you and two men)? | 316 | 15.3 | 614 | 29.8 | 1133 | 54.9 |

| 2 Had a threesome (you and another man and woman)? | 1583 | 76.7 | 365 | 17.7 | 115 | 5.6 |

| 3 Had a threesome (you and two women)? | 1892 | 91.7 | 140 | 6.8 | 31 | 1.5 |

| Group Sex and Sex Parties | ||||||

| 4 Been part of a group sex event (e.g., an orgy, or a spontaneous gathering of four or more people that turns sexual) at your home/apartment or someone else’s home/apartment? | 844 | 40.9 | 599 | 29.0 | 620 | 30.1 |

| 5 Attended a free sex party at someone else’s home/apartment? | 1159 | 56.2 | 467 | 22.6 | 437 | 21.2 |

| 6 Attended a sex party at someone else’s home/apartment that charged a cover for admission? | 1616 | 78.3 | 244 | 11.8 | 203 | 9.8 |

| 7 Attended a free sex party at a private venue (e.g., a sex club)? | 1380 | 66.9 | 364 | 17.6 | 319 | 15.5 |

| 8 Attended a sex party at a private venue (e.g., a sex club) that charged a cover for admission? | 1379 | 66.8 | 339 | 16.4 | 345 | 16.7 |

| 9 Attended a sex party at a private venue (e.g., a sex club) that requires a subscription or membership? | 1498 | 72.6 | 284 | 13.8 | 281 | 13.6 |

| 10 Attended a sex party for people of the same HIV status as you (i.e., ‘neg for neg’, ‘poz for poz’)? | 1657 | 80.3 | 166 | 8.0 | 240 | 11.6 |

| 11 Attended a bareback themed sex party? | 1619 | 78.5 | 198 | 9.6 | 246 | 11.9 |

| 12 Attended a jerk-off/oral sex only themed party? | 1559 | 75.6 | 305 | 14.8 | 199 | 9.6 |

| 13 Attended a safer sex only themed party? | 1545 | 74.9 | 279 | 13.5 | 239 | 11.6 |

| 14 Attended a ‘mixed’ themed sex party (e.g., both bareback and safer sex with wristbands or other identifiers to indicate your preference)? | 1687 | 81.8 | 190 | 9.2 | 186 | 9.0 |

| 15 Attended a naked massage-only erotic themed party? | 1728 | 83.8 | 170 | 8.2 | 165 | 8.0 |

| 16 Attended a kink (e.g., BDSM, fisting) themed sex party? | 1667 | 80.8 | 227 | 11.0 | 169 | 8.2 |

| 17 Attended a watersports* themed sex party? | 1793 | 86.9 | 149 | 7.2 | 121 | 5.9 |

| 18 Attended a sex party for men of certain races (e.g., ‘men of color’)? | 1733 | 84.0 | 180 | 8.7 | 150 | 7.3 |

| 19 Attended a sex party for men of certain body types (e.g., muscle men, jocks, thin men, twinks, bears)? | 1588 | 77.0 | 231 | 11.2 | 244 | 11.8 |

| 20 Attended a sex party for men of certain ages (e.g., young men only, daddies only)? | 1656 | 80.3 | 197 | 9.5 | 210 | 10.2 |

Urine play/exchange

Demographic characteristics

Participants completed measures for demographic characteristics including age, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, HIV status, and age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic differences in sex party attendance

| Group a

|

Attended a sex party? Group b

|

Group c

|

χ2 | df | p | Post hoc † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never in my life (“non-attendees”) n = 650 |

Yes, but not in the last year (“lifetime attendees”) n = 480 |

Yes, in the last year (“past year attendees”) n = 933 |

||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Sexual identity | ||||||||||

| Gay | 485 | 74.6 | 367 | 76.5 | 729 | 78.1 | 9.60 | 6 | 0.14 | -- |

| Bisexual | 155 | 23.8 | 99 | 20.6 | 181 | 19.4 | ||||

| Queer | 4 | 0.6 | 9 | 1.9 | 17 | 1.8 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 6 | 0.9 | 5 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.6 | ||||

| Sex Role | ||||||||||

| Bottom (100%) | 84 | 12.9 | 62 | 12.9 | 149 | 16.0 | 9.36 | 8 | 0.31 | -- |

| Versatile bottom | 180 | 27.7 | 109 | 22.7 | 229 | 24.5 | ||||

| Versatile (50/50) | 162 | 24.9 | 128 | 26.7 | 249 | 26.7 | ||||

| Versatile top | 148 | 22.8 | 120 | 25.0 | 196 | 21.0 | ||||

| Top (100%) | 76 | 11.7 | 61 | 12.7 | 110 | 11.8 | ||||

| HIV Status | ||||||||||

| Negative | 504 | 77.7 | 314 | 65.4 | 574 | 61.5 | 64.09 | 4 | < .001 | a ≠ b, c |

| Positive | 75 | 11.6 | 115 | 24.0 | 262 | 28.1 | ||||

| Unknown | 70 | 10.8 | 51 | 10.6 | 97 | 10.4 | ||||

| Race or Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 369 | 56.8 | 303 | 63.3 | 581 | 62.3 | 1.96 | 3 | 0.58 | -- |

| Black | 120 | 18.5 | 69 | 14.4 | 129 | 13.8 | ||||

| Latino | 76 | 11.7 | 45 | 9.4 | 110 | 11.8 | ||||

| Multiracial or “other” | 85 | 13.1 | 62 | 12.9 | 113 | 12.1 | ||||

| Currently in a relationship | ||||||||||

| Yes | 472 | 72.6 | 0.08 | 64.2 | 637 | 68.3 | 9.30 | 2 | 0.01 | a ≠ b |

| Md | IQR | Md | IQR | Md | IQR | χ2* | df | p | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| What is your age? | 29 | 23–43 | 38 | 27–48 | 37 | 27–48 | 92.78 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b, c |

Kruskal Wallis test (non-parametric equivalent to ANOVA)

As appropriate, post hoc tests were conducted using partial χ2 or Mann Whitney U with LSD criterion

Behavioral and social risk factors

Participants completed the 10-item Sexual Compulsivity (SC) Scale13 (α =.91), capturing feelings of loss of control over sexual thoughts and behaviors. Consistent with existing literature,14–16 we categorized scores of 24 as indicative of SC symptomology (M=21.1, SD=7.88, Range 10–40).

Participants indicated use of alcohol and any of the following drugs in the last three months: cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA (ecstasy), GHB, ketamine, marijuana, crack, nitrate inhalants (poppers), erectile drugs, or heroin. Participants indicated the number of male partners they had sex with in a given week, the last 30 days, and the last 90 days, and the number of UAI acts with male partners in the last 90 days. Participants indicated any anal or vaginal sex with female or transgender partners (combined), as well as their combined number of female/transgender partners (in 90 days), and the combined number of unprotected anal or vaginal acts with these partners (in 90 days). Because of the known risk of HIV transmission with main partners,17 participants were instructed to include sexual activity with main partners in their estimates. Participants indicated the preferred age of their sex partners (younger, same age, older, or “It doesn’t matter”) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Social and behavioral differences in sex party attendance

| Attended a sex party? | χ2 | df | p | Post hoc † | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group a

|

Group b

|

Group c

|

||||||||

| Never in my life (“non-attendees”) n = 650 |

Yes, but not in the last year (“lifetime attendees”) n = 480 |

Yes, in the last year (“past year attendees”) n = 933 |

||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Sexual Compulsivity Scale score is ≥ 24 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 191 | 29.4 | 168 | 35.0 | 366 | 39.2 | 16.29 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b, c |

| Do you typically prefer your sex partners to be… | ||||||||||

| Younger than you | 126 | 19.4 | 130 | 27.1 | 213 | 22.8 | 45.60 | 6 | < .001 | a ≠ b, c |

| The same age as you | 121 | 18.6 | 56 | 11.7 | 94 | 10.1 | ||||

| Older than you | 133 | 20.5 | 72 | 15.2 | 142 | 15.2 | ||||

| It doesn’t matter | 270 | 41.5 | 221 | 46.0 | 484 | 51.9 | ||||

| Drug and alcohol use, ≤ 90 days | ||||||||||

| Alcohol | 498 | 76.6 | 373 | 77.7 | 750 | 80.4 | 3.51 | 2 | 0.17 | -- |

| Cocaine | 35 | 5.4 | 28 | 5.8 | 88 | 9.4 | 11.29 | 2 | 0.004 | a, b ≠ c |

| Methamphetamine | 9 | 1.4 | 21 | 4.4 | 102 | 10.9 | 62.59 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| MDMA, Ecstasy | 15 | 2.3 | 17 | 3.5 | 56 | 6.0 | 13.61 | 2 | 0.001 | a, b ≠ c |

| GHB | 2 | 0.3 | 9 | 1.9 | 51 | 5.5 | 37.71 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Ketamine1 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 1.5 | NA | a, b ≠ c | ||

| Marijuana | 202 | 31.1 | 158 | 32.9 | 335 | 35.9 | 4.17 | 2 | 0.13 | -- |

| Crack | 5 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.6 | 31 | 3.3 | 18.87 | 2 | < .001 | a, b ≠ c |

| Poppers | 109 | 16.8 | 145 | 30.2 | 422 | 45.2 | 142.72 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Erectile drugs (e.g., Viagra, Cialis) | 52 | 8 | 93 | 19.4 | 281 | 30.1 | 115.00 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Heroin 2 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.6 | 15 | 1.6 | NA | a ≠ c | ||

| Any stimulant drug use, ≤ 90 days (cocaine, meth, crack) | 43 | 6.6 | 46 | 9.6 | 159 | 17.0 | 42.89 | 2 | < .001 | a, b ≠ c |

| Any drug use, ≤ 90 days (excludes alcohol) | 284 | 43.7 | 280 | 58.3 | 633 | 67.8 | 91.79 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Md | IQR | Md | IQR | Md | IQR | χ2 * | df | p | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Number of male sex partners in a given week | 1 | 0–2 | 1 | 1–2 | 2 | 1–4 | 306.46 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Number of male sex partners, ≤ 30 days | 1 | 2–4 | 3 | 1–6 | 6 | 3–12 | 340.34 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| Number of male sex partners, ≤ 90 days | 4 | 2–9 | 6 | 3–12 | 15 | 6–30 | 359.78 | 2 | < .001 | a ≠ b ≠ c |

| ||||||||||

| Had anal or vaginal sex with a female or transgender partner, ≤ 90 days | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Kruskal Wallis test (non-parametric equivalent to ANOVA)

NA: Not applicable. Chi-square test cannot be performed. Expected counts fell below 5 in one or more cells

Fisher’s Exact paired tests: Group a and b, p = 51; Group a and c, p = .02; Group b and c, p = .003

Fisher’s Exact paired tests (two-tailed): Group a and b, p = .08; Group a and c, p < .001; Group b and c, p = .14

As appropriate, post hoc tests were conducted using partial χ2 or Mann Whitney U with LSD criterion

HIV/STI prevention, education, and services at sex parties

Participants who had ever been to a sex party (n=1,413) were asked to select the types of HIV/STI prevention, education, and health services they would like to see or receive at sex parties (Table 4).

Table 4.

Preferences for HIV and STI prevention, education, and services at Sex Parties (n = 1413 men who attended sex parties)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Which of the following would you like to see or receive at sex parties? (select all that apply) | ||

| 1 Free lubricant | 1320 | 93.4 |

| 2 Free condoms | 1144 | 81.0 |

| 3 Free rapid HIV testing (where you receive results in 20 minutes at the event) | 746 | 52.8 |

| 4 Free STI testing | 621 | 43.9 |

| 5 Free testicular exams | 522 | 36.9 |

| 6 Information on where to get HIV testing | 381 | 27.0 |

| 7 Advertisements for HIV research studies | 305 | 21.6 |

| 8 Regular HIV testing (where you have to visit an office sometime later to receive results) | 297 | 21.0 |

| 9 Live safer sex demonstrations | 297 | 21.0 |

| 10 Brochures on sexual health | 291 | 20.6 |

| 11 Brochures on HIV | 263 | 18.6 |

| 12 Sexual health posters | 211 | 14.9 |

| 13 Video safer sex demonstrations | 184 | 13.0 |

| 14 Medical providers | 166 | 11.7 |

| 15 Peer outreach workers | 134 | 9.5 |

Analytic plan

Using descriptive statistics, we report on prevalence and patterns of multiple partner encounters. Using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis tests, we compared three groups of men: (1) those who attended sex parties in the last year (“past year attendees”); (2) those who attended a sex party more than a year ago (“lifetime attendees”); and (3) those who had never attended a sex party (“non-attendees”). In two instances, expected counts fell below five and paired Fisher’s exact tests (two-tailed) were used. We compared participants on socio-demographic and behavioral characteristics. Post-hoc tests were conducted using partial chi-square and Mann-Whitney U with LSD criterion.

We conducted two multivariable models: a logistic regression utilized to identify associations with UAI with a male partner in the last 90 days (1=yes, 0=no) and a negative binomial regression to identify associations with the number of UAI acts with male partners in the last 90 days. Such an approach allows us to investigate factors associated with the absence/presence of HIV/STI risk as well as magnitude of exposure. Independent variables entered into the model included sex party attendance (past year, lifetime, and non-attendance), recent stimulant (methamphetamine, cocaine/crack) use (1=yes, 0=no), a dichotomous indicator of SC symptomology, age (in years), HIV-positive status (1=yes, 0=no), number of male partners (≤ 90 days), and whether participants were currently in a relationship (1=yes, 0=no). These variables were selected based on significant observed bivariate associations as well as conceptual relevance.

Finally, we report descriptive statistics on the acceptability of HIV/STI prevention, education, and services at sex parties.

RESULTS

Participants resided in 49 of the 50 states and Puerto Rico. The majority were White, gay-identified, and reported being HIV-negative. Mean age was 36.2 years (SD=12.2).

Patterns and prevalence of multi-partner encounters

Table 1 reports patterns and prevalence of multi-partner encounters. A majority (54.9%) participated in a threesome with two other men in the previous year. Threesomes with female partners in the last year were less common—7.1% reported a threesome with women. Participants had attended events in private homes or commercial sex venues, either free or for a cover charge. In the past year, 11.6% of men had attended a sex party themed around serosorting (e.g., HIV-positive men only); 11.9% had attended a barebacking sex party, 11.6% had attended a safer sex party, and 9.0% had been to a ‘mixed’ safe-unsafe sex party (i.e. wristbands identified what types of sex men were into). With regard to themes not previously described in literature, 11.8% of men attended a sex party for certain body types (e.g., muscle men, thin men); 10% attended a party themed around age groups (e.g., young men only, ‘daddies’ only).

Participants who had taken part in a sex party or group sex in their lifetime (n=1413, 68.5%) indicated how many sex parties they attended in the previous year. Sixty-six percent (n=933) attended at least one in the past year (Mdn=3; IQR 2–6; “past year attendees”) and 33.9% (n=480) said they had been to a sex party, but not in the last year (“lifetime attendees”).

Demographic differences in sex party attendance

Sexual identity, sex role, and racial/ethnic background were not associated with sex party attendance. Sex party attendance was related to HIV status, relationship status, and age. In total, 28.1% of past year attendees and 24.0% of lifetime attendees were HIV-positive compared with only 11.6% of non-attendees. A significantly higher proportion of non-attendees were in a relationship (72.6%) and younger (Mdn=29). See Table 2.

Social and behavioral differences in sex party attendance

Compared to non-attendees (29.4%), a higher proportion of past year (39.2%) and lifetime (35.0%) attendees reported SC symptomology. Compared to non-attendees (41.5%), a higher proportion of past year (51.9%) and lifetime (46.0%) attendees indicated partners’ ages did not matter. A significantly larger proportion of past year attendees (67.8%) reported drug use, followed by lifetime attendees (58.3%) and non-attendees (43.7%). There were no significant differences in recent marijuana or alcohol use; however, past year attendees were the most likely to have recently used all other drugs assessed. See Table 3.

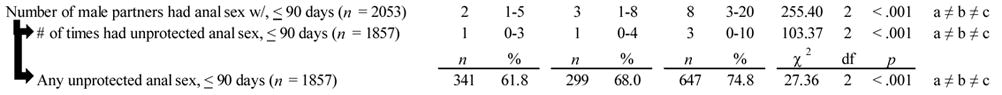

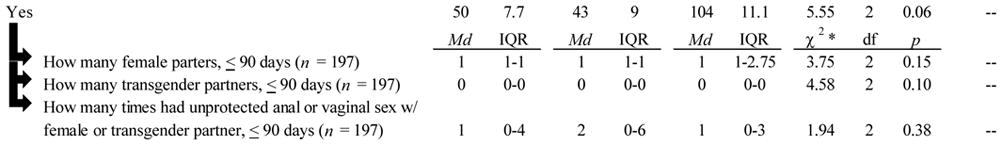

There were notable differences in sexual behavior with male partners across the three groups. Past year attendees reported the greatest number of male sex partners in a given week (Mdn=2), the last 30 days (Mdn=6), and the last 90 days (Mdn=15). Past year attendees reported having anal sex with the greatest number of male sex partners in the last 90 days (Mdn=8). Compared to non-attendees (85.9%), a significantly greater proportion of past year attendees (93.5%) and lifetime attendees (92.2%) reported anal sex with male partners in the last 90 days (χ2(2)=27.9, p<.001). Among those (n=1,857), compared with lifetime and non-attendees, past-year sex party attendees reported the greatest proportion of UAI with a male partner (74.8%) and the greatest number of UAI acts (Mdn=3). There were no significant differences in sexual behavior with female and transgender partners.

Multivariable associations with UAI with a male partner (yes/no) and UAI acts

For all participants (n=2063), we conducted logistic regression to predict UAI with a male partner in the past 90 days (1=yes, 0=no). Compared to non-attendees, past year attendees had 1.45 times the odds of engaging in UAI (CI95% 1.16–1.83, p=.001); lifetime sex party attendees had 1.37 times the odds of UAI (CI95% 1.07–1.77, p =.01). Stimulant drug use in the past 90 days (AOR=2.78, CI95% 1.92–4.02, p<.001), being HIV-positive (AOR=1.94, CI95% 1.51–2.50, p<.001), demonstrating SC symptomology (AOR=1.26, CI95% 1.03–1.54, p=.02), and reporting a greater number of male sex partners (AOR=1.02, CI95% 1.01–1.02, p<.001) were independently associated with increased odds for UAI. Age was inversely associated with UAI (AOR=0.99, CI95% .98-.998, p=.018). Relationship status was not associated with UAI (AOR=.90, CI95% .74–1.10, p=.31).

We conducted the same procedures using negative binomial regression to predict the number of UAI acts with male partners in the last 90 days (Mdn=1, IQR=0–5). Compared to past year attendees, non-attendees had a 29% lower rate of UAI (Exp β = 0.71, CI95%=.62–.81); lifetime attendees had a 24% lower rate of UAI (Exp β = 0.76, CI95%=.66–.87). Having used stimulant drugs (Exp β=1.43, CI95%=1.24–1.65, p<.001), being HIV-positive (Exp β=1.78, CI95%=1.58–2.01, p<.001), reporting a greater number of male partners (Exp β=1.02, CI95%=1.02–1.03, p<.001), and currently being in a relationship (Exp β=1.34, CI95%=1.21–1.50, p<.001) were associated with higher rates of UAI. Age was negatively associated with UAI acts (Exp β=.99, CI95%=.987-.996, p<.001). SC symptomology was not associated with the rate of UAI (Exp β=1.05, CI95%=.95–1.17, p=.31),

Acceptability of HIV/STI prevention, education, and services at sex parties

Lifetime and past year sex party attendees were asked follow-up questions about different types of HIV and STI prevention, education, or services they would like to have available at sex parties (Table 4). The vast majority of participants indicated they would want to receive free lubricant (93.4%) and condoms (81.0%); a majority expressed interest in free rapid HIV testing (52.8%). More than one-third expressed interest in free STI testing (43.9%) and testicular exams (36.9%). Least-endorsed items included peer outreach workers (9.5%), medical providers (11.7%) and video safer sex demonstrations (13.0%).

DISCUSSION

Compared with non-attendees and lifetime attendees, past year attendees differed by demographic and behavioral characteristics, suggesting these men may comprise a high-risk group for HIV/STI transmission. Sex party attendance was independently associated with engaging in UAI even after adjusting for known HIV/STI risk factors. These findings are consistent with others;3,9,11 however they do not suggest that participants engaged in these behaviors at sex parties. Instead, they suggest men who attend sex parties may be in great need of targeted HIV and STI prevention.

Free condoms and lubricant were the most desirable services/products men would like at sex parties; these could be supplied by community outreach providers. More than half of men expressed interest in free rapid HIV testing at sex parties; other research on on-site HIV testing in bathhouses suggested promising results.18,19 Studies have shown that MSM are willing to use rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners; this strategy could aid in HIV prevention.20,21 Yet, available rapid tests cannot capture acute HIV-infection, and may reinforce UAI for some.22 Added, it remains unclear the extent to which MSM who self-test as HIV-positive subsequently seek care.23 As such, it is necessary to determine how testing at sex parties impacts behavior.

The proportion of men reporting past year attendance appears higher than other studies, though they had different recall windows (i.e., 3-, 6-months).3,9,11 Pollock et al.11 reported that 8.9% of their sample had been to barebacking-themed sex parties in the past 6 months, compared with 11.9% of our participants in the past 12 months. These findings suggest notable prevalence of MSM attending sex parties that confer HIV/STI transmission risks. We reported on a broader range of themes and found that a noteworthy proportion of men (16%–25%) attended a party involving behaviors conferring lower risk of HIV transmission (massage, oral sex), though we did not collect data about their actual practices. Thus, not all sex parties are inherently risky. These findings highlight the need to assess within-person differences among male sex party attendees.

Findings regarding themed events suggest unique opportunities for providers to target demographic (e.g., younger men, men of color) and behavioral (i.e. bareback) groups. Our findings also suggest providers may want to use caution implementing preventive services at sex parties. Although over half of participants expressed interest in HIV testing and over one-third in STI testing or testicular exams, seeing “medical providers” and “peer outreach workers” was seldom considered acceptable. There may also be logistical challenges in working with events that occur in private residences or hotel rooms (e.g., finding private/separate spaces to interact with patrons, keeping updated on the ephemeral nature of the sex party scene). Providers might consider collaborating with party organizers to deliver programs, and reach out to party attendees as they enter or leave.

There are strengths and limitations to consider. We captured a range of types of sex parties, though this list was not exhaustive. We did not focus on the behaviors men might have engaged in within a sex party, thus causality cannot be inferred. We cannot attest to within-person variability in and out of sex parties.

Responses were self-reported, questions were closed-ended, and some wording was perhaps not ideal. For example, participants reported UAI with main and casual male partners combined. Relationship status was not associated with whether participants engaged in UAI (yes/no), but was associated with the number of UAI acts. This may indicative of increased UAI acts with a main partner. Participants reported sexual behavior with female and transgender partners combined, thus behavior with non-transgender and transgender female partners cannot be disentangled. We also did not have data on partners’ HIV statuses.

Findings were based on an online volunteer sample of men recruited from a single sexual-networking website. This sample engaged in greater HIV/STI risk behaviors than what has been documented in CDC surveillance data.24 Because websites often cater to specific audiences, these findings may not generalize to other sites. For example, our sample was younger and more racially and ethnically diverse than those from previous online studies,25–27 which is both a strength and limitation. The completion rate of 69% for our study was higher than most online studies of MSM.25,27–29 Though we lacked sufficient data on those who did not complete the survey to determine if attrition was random, attrition patterns suggested non-completion may have resulted from fatigue.27,30 There was no incentive for this online study, though our aim was to recruit/screen for larger incentivized studies. This might have motivated individuals to complete the survey more than once, though we found little evidence of duplicate cases.

This study has implications for providers and researchers. Past year attendees were at high risk for UAI, drug use, and SC. Collaborating with promoters presents valuable opportunities to (1) tailor outreach efforts to at-risk men, (2) provide information about behavioral risk reduction and biomedical strategies (rapid testing, PrEP), and (3) ensure the availability of condoms and lubricant. Researchers might consider evaluating the effect of on-site services in reducing HIV and STI transmission risks. Finally, this study found clear between-person differences with regard to those who do and do not attend sex parties. A next empirical question to examine is whether there is within-person variability regarding behavior in and out of sex parties.

KEY MESSAGES.

MSM who have attended a sex party in the last year demonstrate high risk for HIV and STI transmission.

MSM who have attended a sex party in the last year are appropriate candidates for targeted HIV and STI prevention.

Although a majority of men having been to a sex party expressed interest in free rapid HIV testing at sex parties, few considered it acceptable to see prevention providers at sex parties.

Collaborating with event promoters presents valuable opportunities to identify men who may be at risk, and to deliver services such as condoms, lubricant, and HIV/STI testing.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Data for this study were gathered in concert with online recruitment efforts to identify and screen potential participants to enroll in one of the following studies conducted at the Hunter College Center for HIV Educational Studies and Training (CHEST): Pillow Talk (R01 MH087714 – Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator), MiChat (R03 DA031607 – Corina Weinberger, Principal Investigator), and W.I.S.E. (R01 DA029567 – Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). Jonathon Rendina was supported in part by a National Institute of Mental Health Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31 MH095622). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Ruben Jimenez and Joshua Guthals for their valuable assistance with the projects, as well as other members of the CHEST Team: Michael Adams, Kailip Boonrai, Pedro Carneiro, Chris Hietikko, Zak Hill-Whilton, and Tyrel Starks.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS:

Christian Grov performed all analyses and took primary responsibility for the writing the manuscript as well as interpreting the findings. Along with his co-authors, Christian developed the survey questions as well as conceptualizing the research questions for the present study.

H. Jonathon Rendina assisted with data analyses and cleaning. He built and managed the electronic survey. He assisted with co-writing the manuscript for intellectual content and interpreting findings.

Aaron S. Breslow contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript through assisting in the writing and editing, as well as interpreting the findings.

Ana Ventuneac was the research scientist who oversaw the study. This included day-to-day operations of the study, conceptualizing measures, and intellectual contributions to the manuscript.

Stephan Adelson consulted with the research team in designing the survey and selecting appropriate measures for this study. He also participated in revising the manuscript for intellectual content.

Jeffrey T. Parsons is the Principal Investigator (PI) of the study from which these data are taken. This included conceptualizing the study design and oversight of all scientific decisions. Along with other co-authors, Jeffrey edited the manuscript. As PI, he also carries the responsibilities of the corresponding author and provided final approval of the completed manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

None

“The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in STI and any other BMJPGL products and sub-licenses such use and exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license" http://group.bmj.com/products/journals/instructions-for-authors/licence-forms”.

References

- 1.CDC. Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2012;17(4) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullens AB, Staunton S, Debattista J, et al. Sex on premises venue (SOPV) health promotion project in response to sustained increases in HIV notifications. Sexual Health. 2009;6(1):41–4. doi: 10.1071/sh07087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual risk behavior and venues for meeting sex partners: an intercept survey of gay and bisexual men in LA and NYC. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:915–26. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9199-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grov C, Hirshfield S, Remien RH, et al. Exploring the venue’s role in risky sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men: An event-level analysis from a national online survey in the U. S Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9854-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT. HIV status differences in venues where highly-sexually active gay and bisexual men meet sex partners: Results from a pilot study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22:496–508. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. An emerging HIV risk environment: a preliminary epidemiological profile of an MSM POZ Party in New York City. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81(5):373–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland S, et al. “It’s a quick way to get what you want”: a formative exploration of HIV risk among urban Massachusetts men who have sex with men who attend sex parties. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(10):659–74. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland SE, et al. Sex parties among urban MSM: an emerging culture and HIV risk environment. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(2):305–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon TM, Halkitis PN, Moeller RM, et al. Sex parties among young gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New York City: Attendance and behavior. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(6):1063–75. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9590-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman SR, Bolyard M, Khan M, et al. Group sex events and HIV/STI risk in an urban network. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2008;49(4):440–6. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181893f31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock JA, Halkitis PN. Environmental factors in relation to unprotected sexual behavior among gay, bisexual, and other MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(4):340–55. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grov C, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, et al. HIV risk in group sexual encounters: An Event-level analysis from an online survey of MSM in the U.S. Journal of Sexual Medicine. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12227. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, et al. Sexual sensation seeking: scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;62(3):385–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsons JT, Bimbi DS, Halkitis PN. Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:940–49. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:156–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan PS, Salazar L, Buchbinder S, et al. Estimating the proportion of HIV transmissions from main sex partners among men who have sex with men in five US cities. AIDS. 2009;23(9):1153–62. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832baa34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binson D, Blea L, Cotten PD, et al. Building an HIV/STI prevention program in a gay bathhouse: a case study. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(4):386–99. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huebner DM, Binson D, Woods WJ, et al. Bathhouse-based voluntary counseling and testing is feasible and shows preliminary evidence of effectiveness. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;43(2):239–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242464.50947.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ventuneac A, Carballo-Dieguez A, Leu CS, et al. Use of a rapid HIV home test to screen sexual partners: an evaluation of its possible use and relative risk. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(4):731–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9565-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, et al. Will gay and bisexually active men at high risk of infection use over-the-counter rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners? Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(4):379–87. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.647117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leaity S, Sherr L, Wells H, et al. Repeat HIV testing: high-risk behaviour or risk reduction strategy? AIDS. 2000;14(5):547–52. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pai NP, Sharma J, Shivkumar S, et al. Supervised and unsupervised self-testing for HIV in high-and low-risk populations: A systematic review. PLoS Medicine. 2013;10(4):e1001414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez T, Smith A, Denson D, et al. Internet-based methods may reach higher-risk men who have sex with men not reached through venue-based sampling. Open AIDS Journal. 2012;6(1):83–89. doi: 10.2174/1874613601206010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Sexual behaviors and situational characteristics of most recent male-partnered sexual event among gay and bisexually identified men in the United States. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011;8:3040–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Schick V, et al. Condom use during most recent anal intercourse event among a U.S. sample of men who have sex with men. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9:1037–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis among men who have sex with men using an Internet social networking site. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor BS, Chiasson MA, Scheinmann R, et al. Results from two online surveys comparing sexual risk behaviors in Hispanic, Black, and White men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(3):644–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9983-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS. Predictors of retention in an online follow-up study of men who have sex with men. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(3):e47. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2011 [Google Scholar]