Abstract

TGF-β and Foxp3 expressions are crucial for the induction and functional activity of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T (iTreg) cells. Here, we demonstrate that although TGF-β-primed CD8+ cells display much lower Foxp3 expression, their suppressive capacity is equivalent to that of CD4+ iTreg cells, and both Foxp3− and Foxp3+ CD8+ subsets have suppressive activities in vitro and in vivo. CD8+Foxp3− iTreg cells produce little IFN-γ but almost no IL-2, and display a typical anergic phenotype. Among phenotypic markers expressed in CD8+Foxp3− cells, we identify CD103 expression particularly crucial for the generation and function of this subset. Moreover, IL-10 and TGF-β signals rather than cytotoxicity mediate the suppressive effect of this novel Treg population. Therefore, TGF-β can induce both CD8+Foxp3− and CD8+Foxp3+ iTreg subsets, which may represent the unique immunoregulatory means to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: CD8+, regulatory T cells, TGF-β, Foxp3, CD103

Introduction

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory/suppressor T (Treg) cells play a pivotal role in the maintenance of immune homeostasis and the prevention of autoimmunity (Sakaguchi, 2005). These cells comprise thymus-derived, naturally occurring CD4+ regulatory T (nTreg) cells and induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells that can be induced in the periphery (Horwitz et al., 2008). Although two Treg subsets exhibit different developmental mechanisms, they share similar phenotypes and both develop suppressive activities (Zheng et al., 2002, 2004; Chen et al., 2003). Both subsets contribute to the Treg cell network and they may either have a synergetic action or act on different targets to maintain immune homeostasis (Lan et al., 2012a, b).

In addition to CD4+ Treg cells, CD8+ Treg cells might also play an important role in immune tolerance and homeostasis. Similar to CD4+ nTreg cells, CD8+ nTreg cells also exist in the rodents and humans, although their frequency is much lower than that of CD4+ nTreg cells (Cosmi et al., 2003). However, in certain organs such as eye and tonsil, CD8+ Treg cells likely play a predominant role in sustaining immune tolerance (Siegmund et al., 2009; Sharafieh et al., 2011). Additionally, CD8+CD28− and CD8+CD122+ cell populations also constitute CD8+ Treg subsets that have demonstrated their suppressive capacity in transplantation and autoimmunity (Suciu-Foca et al., 2003; Rifa'i et al., 2004).

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is essential for the induction of Foxp3 expression, for conferring suppressive activity on CD4+ iTreg cells, as well as for the maintenance of both Foxp3+ nTreg and iTreg cells (Zheng et al., 2002, 2007; Chen et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2010). However, it is less clear whether TGF-β also directly induces the development of CD8+ Foxp3+ iTreg cells as it does for CD4+Foxp3+ iTreg cells. While others have observed that administration of peptides to lupus-prone mice could induce CD8+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in vivo (Hahn et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2005), we here demonstrate that TGF-β combined with TCR stimulation is able to induce ex vivo a novel CD8+ Treg cell subset, CD8+Foxp3−CD103+ that does not require Foxp3 expression for its development, besides CD8+Foxp3+ iTreg subset. Despite the absence of Foxp3 expression, these CD8+Foxp3−CD103+ Treg cells display an anergic phenotype and develop potent suppressive activity against T cell responses. With IL-10 and TGF-β signals both contributing to their suppression, CD8+Foxp3− and CD8+Foxp3+ iTreg subsets display suppressive activity in a cell contact-dependent and non-cytotoxic manner. Our results demonstrate that both TGF-β-induced CD8+ Treg cell subsets, CD8+Foxp3+ and CD8+Foxp3−CD103+, have protective effects against pathologic immune-mediated inflammation.

Results

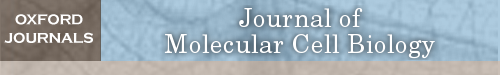

The CD8+Foxp3− cell population in TGF-β-primed CD8+ cell cultures exhibits a potent suppressive functionality

Foxp3 expression is an important feature for identifying CD4+ nTreg and iTreg cells (Hori et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2010). TGF-β-primed CD4+ (CD4TGF-β) and CD8+ (CD8TGF-β) cells were generated as described in Materials and methods using Foxp3gfp knock-in mice. Foxp3 (GFP) expression was measured by flow cytometry and Treg cell function was examined using a standard suppressive assay in vitro. Given that CD8TGF-β cells express reduced Foxp3 but display at least similar suppressive activity to CD4TGF-β cells (Supplementary Figure S1), we consider two potential possibilities. First, single CD8+ cell exhibits an enriched Foxp3 expression and renders superior suppression. Second, the Foxp3− cell subset present in CD8TGF-β also suppresses T cell responses. To the end, we found that the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Foxp3 expression in CD8TGF-β cells did not differ from that in CD4TGF-β cells (Figure 1A). Foxp3+ and Foxp3− cell subsets were FACS-sorted based on GFP expression for further functional characterization. The suppressive activities of purified Foxp3+ (GFP+) cells sorted from CD8TGF-β cells were comparable with those from CD4TGF-β cells (Figure 1B), excluding the possibility that the CD8+Foxp3+ cell population has a different Treg functional activity on a per cell basis. While the suppressive function of CD4TGF-β cells was closely associated with their Foxp3 expression, this was not the case for CD8TGF-β cells (Figure 1B). Unexpectedly, both Foxp3+ and Foxp3− subsets isolated from CD8TGF-β cells equivalently suppressed T cell responses in vitro (Figure 1B). We further confirmed this result using an in vivo colitis experiment, an animal model of inflammatory bowel disease. We determined that while the Foxp3− subset of CD4TGF-β cells failed to suppress colitis, the Foxp3− subset isolated from CD8TGF-β cells displayed a frank suppression on weight loss, disease severity, and pathology, comparable with that obtained using the Foxp3+ cells isolated from CD4TGF-β or CD8TGF-β cells (Figure 1C). These studies indicate that TGF-β is able to induce both CD8+Foxp3+ and CD8+Foxp3− regulatory T cell populations.

Figure 1.

The suppressive activity of CD8+ iTreg cells is independent of Foxp3 expression. (A) CD8+CD62L+CD25−Foxp3−(GFP−) and CD4+CD62L+CD25−Foxp3−(GFP−) cells isolated from C57BL/6 Foxp3gfp knock-in mice were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 (1 µg/ml), soluble anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml), IL-2 (100 U/ml), and TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 3 days. The Foxp3 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was shown. Data were mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. NS, no significance. (B) After 3 days of culture, Foxp3+ (GFP+) or Foxp3− (GFP−) cell subsets isolated from TGF-β-activated CD4+ or CD8+ cells were sorted by FACSAria II. Each of these cell subsets was added to CFSE-labeled T cells and stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 and irradiated mouse non-T cells for 72 h. The proliferation of T cells was determined by the dilution of CFSE on the CD4 or CD8 gate. Data are representative of the CFSE histogram gated on CD4+ or CD8+ cells (left) or mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (right). ***P < 0.001. (C) Rag2−/−mice were transferred with 5 × 105 CD4+CD45RBhi T cells along with PBS, CD8+Foxp3+, CD8+Foxp3−, CD4+Foxp3+, or CD4+Foxp3−cells (1 × 106 cells). Animal weight was monitored and mice were sacrificed when they developed clinical signs of disease (∼8 weeks after transfer). The weight, representative photomicrographs of midcolon sections, and colitis scores are shown (n = 6 in each group). NS, no significance; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

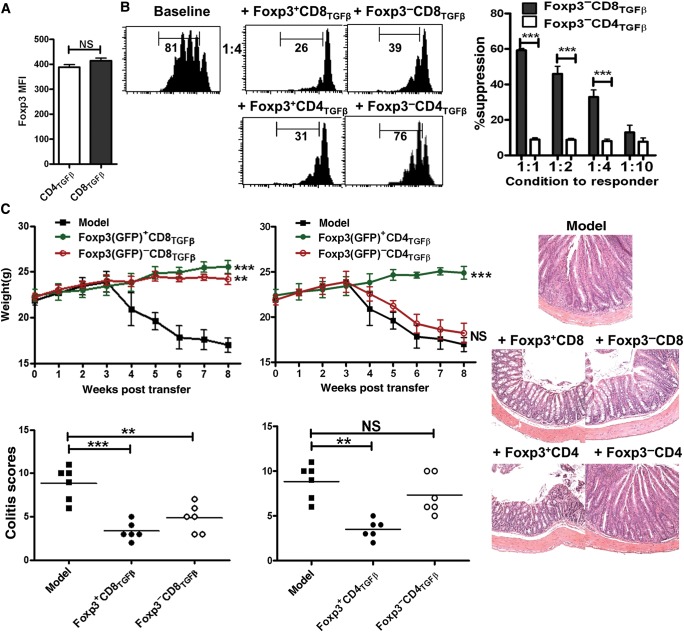

Phenotypic features of Foxp3− and Foxp3+ cell subpopulations in TGF-β-primed CD8+ cell cultures

The finding that the Foxp3− subpopulation of CD8TGF-β cells has suppressive function compels us to further investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for the development and function of novel CD8+ Treg cell subset in the absence of Foxp3 expression. We first studied the phenotypic features related to Treg cells. In contrast to CD25, GITR, and TNFRII that were highly expressed in CD8med as well as various subsets (Foxp3+ and Foxp3−) of CD8TGF-β and CD4TGF-β cells, TGF-β treatment did increase CTLA-4, ICOS, and CD62L expression on both CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Figure 2A). ICOS expression was lower in Foxp3− subsets than in Foxp3+ subsets for both CD8TGF-β and CD4TGF-β cells and CD62L expression was not significantly up-regulated on CD8+Foxp3− cells by TGF-β treatment (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Phenotypic features of Foxp3− and Foxp3+ cell subpopulations in TGF-β-primed CD8+ cells. (A) CD8med, CD8TGF-β, and CD4TGF-β were induced as in Figure 1A. The expression levels of Treg-associated markers including CD25, GITR, ICOS, CD62L, CTLA-4, and TNFR2 on Foxp3+ (GFP+) and Foxp3− (GFP−) T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms are representative of three independent experiments showing staining (black) plus isotype control (gray). (B) Intracellular IL-2/IFN-γ production and Foxp3 expression by CD8med, CD8TGF-β, and CD4TGF-β were measured by FACS, and representative data from three independent experiments are shown. Data in the graphs indicate mean ± SEM of three independent experiments showing the frequency of the indicated cytokines. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (C) Both CD4+ and CD8+ iTreg cells were induced in vitro as above. After 3 days of culture, Foxp3+ (GFP+) and Foxp3− (GFP−) cell subsets were sorted by FACSAria II. Each of these cell subsets were re-stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 (0.5 μg/ml) and irradiated non-T cells in the absence or presence of IL-2 (50 U/ml) for 72 h. 3H-TdR was added during the last 16 h of culture. All experiments were performed in triplicates and data are representative of three independent experiments. NS, no significance; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We also examined specific cytokine production from these CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Anergy is a characteristic feature of Treg cells that cells do not proliferate unless exogenous IL-2 is added. In line with previous reports (Zheng et al., 2002), we found that CD4+Foxp3+ cells expressed a certain level of IL-2, but CD8+Foxp3+ cells did not (Figure 2B). This is consistent with our finding that the CD4+Foxp3+ cell subset was not completely anergic, while CD8+Foxp3+ cells would not proliferate at all without the addition of IL-2 (Figure 2C). Furthermore, unlike the CD4+Foxp3− cells isolated from CD4TGF-β, CD8+Foxp3− cells isolated from CD8TGF-β were also completely anergic (Figure 2C). This is likely reason why the CD8+Foxp3− subset from CD8TGF-β cells exhibited a suppressive activity. In addition, TGF-β treatment dramatically suppressed IFN-γ production in CD8+ cells (Figure 2B).

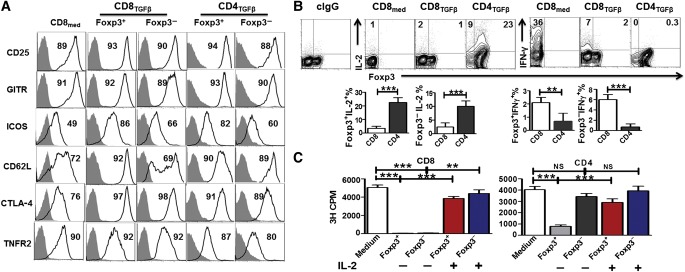

CD103 is essential for the development and function of the CD8+Foxp3− Treg subset

Among the phenotypic markers that we scanned, CD103 was markedly increased in CD8TGF-β cells relative to CD8med cells and CD4TGF-β cells. While freshly isolated CD8+ cells exhibited a complete lack of CD103, those cultured in the presence of TGF-β clearly exhibited a frank expression of this marker (Figure 3A). While very small proportions of both CD4+Foxp3− and CD8med cell subsets expressed CD103, almost all cells of the CD8+Foxp3− subset isolated from CD8TGF-β cells expressed CD103 (Figure 3A), suggesting that CD103 might contribute to the difference in functional activities between CD4+Foxp3− and CD8+Foxp3− cell subsets.

Figure 3.

The essential role of CD103 in the development and function of CD8+ iTreg cells. (A) Naïve CD8+ and CD4+ cells isolated from the spleen of Foxp3gfp knock-in mice were cultured as described in Figure 1A. CD103 expression on freshly isolated CD8+ cells, as well as CD8med, CD8TGFβ, and CD4TGFβ cells, was determined by flow cytometry. (B) Dot plot panel representative of CD8 iTreg sorting, showing the different gated populations as indicated. (C) CD103+Foxp3+, CD103+Foxp3−, and CD103−Foxp3− cell subsets were sorted from CD8 iTreg cells as in B, and their suppressive activity was assessed as in Figure 1B. Suppressive rates were determined by the dilution levels of CFSE. Left panel shows the representative histogram, and the right panel shows mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. (D) Colitis model was developed as in Figure 1C. The three subsets of CD8 iTreg (as shown in panel B) were co-injected with CD4+CD45RBhi cells. Mice were weighed weekly for 8 weeks. Each group has 6 mice. The weight and colitis scores are presented as mean ± SEM. NS, no significance; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We then sorted Foxp3+CD103+, Foxp3−CD103+, and Foxp3−CD103− subsets from CD8TGF-β cells (Figure 3B) and assayed their suppressive activities. Both Foxp3+CD103+ and Foxp3−CD103+ subsets exhibited a strong suppressive effect on T cell proliferation in vitro, but CD103−Foxp3− cells did not (Figure 3C). Likewise, adoptive transfer of either Foxp3+CD103+ or Foxp3−CD103+ but not Foxp3−CD103− subset significantly suppressed colitis (Figure 3D), indicating that CD103 expression emerges as a crucial feature for conferring suppressive activity on CD8+ iTreg cells even in the absence of Foxp3 expression.

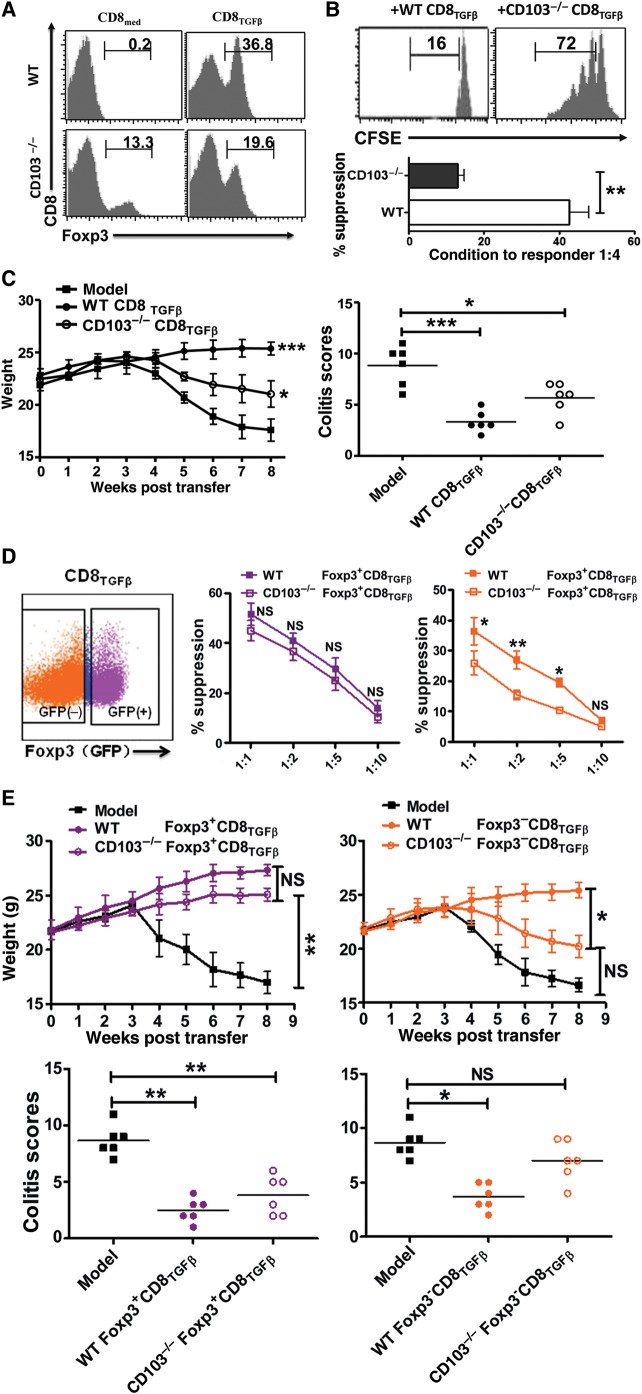

Given that CD8TGF-β cells contained few Foxp3+CD103− cells using our sorting strategy, we cannot rule out the possibility that CD103 may also play a role in CD8+Foxp3+ subset-mediated immunosuppression. We then developed CD103−/− Foxp3gfp knock-in mice for in vitro and in vivo suppressive assays. Foxp3 expression in CD8TGFβ cells from CD103−/− mice was significantly lower than that from WT mice after 3-day (Figure 4A) or longer cultures (not shown). We then developed an assay to test their function. As shown in Figure 4B and C, while CD8TGF-β cells generated from WT mice suppressed T cell proliferation in vitro and colitis development in vivo, CD8TGF-β cells from CD103−/− mice mostly lost their suppressive capacity. We then further sorted Foxp3+ and Foxp3− cell subsets from CD8TGF-β cells that had been induced from CD103−/− mice. To this end, the Foxp3− subset exhibited no immunosuppression, while the Foxp3+ cell population maintained its suppressive capacities in vitro and in vivo (Figure 4D and E). These results suggest that CD103 plays an essential role in the development of CD8+Foxp3− iTreg subset and probably a partial role in the development of CD8+Foxp3+ Treg subset. Conversely, the lack of CD103 did not hamper the development and function of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cell subset (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Inability of TGF-β to generate iTreg from CD8+ cells in CD103 deficient mice. Naïve CD8+CD25− cells isolated from WT or CD103−/− mice were stimulated in vitro as described in Figure 1A. (A) Representative histogram depicting Foxp3 expression from three independent experiments on both CD8med and CD8TGFβ from WT or CD103−/− mice. (B) CD8TGFβ cells from WT or CD103−/− mice were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled T cells, and stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 and irradiated mouse non-T cells for 3 days. The upper panel shows representative histogram of CFSE staining gated on CD4+ T cells. Suppressive rates were determined by CFSE dilution (bottom). **P < 0.01. (C) CD8TGFβ from WT or CD103−/− mice were co-injected with WT CD4+CD45RBhi cells to Rag2−/− mice. The weight of mice was monitored weekly for 8 weeks. Each group has 6 mice. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. (D) Dot plot panel representative of CD8 iTreg sorting, showing the different gated populations as indicated. The suppressive activity of Foxp3+ or Foxp3− CD8TGFβ cells from WT and CD103−/− mice was analyzed as in Figure 1B. The data indicate mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, WT group vs. CD103−/− group. (E) The suppressive activity of CD8+Foxp3+ or CD8+Foxp3− cell population generated from WT or CD103−/− mice in colitis. Mice weight and pathological scores were determined as in Figure 1C. NS, no significance; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

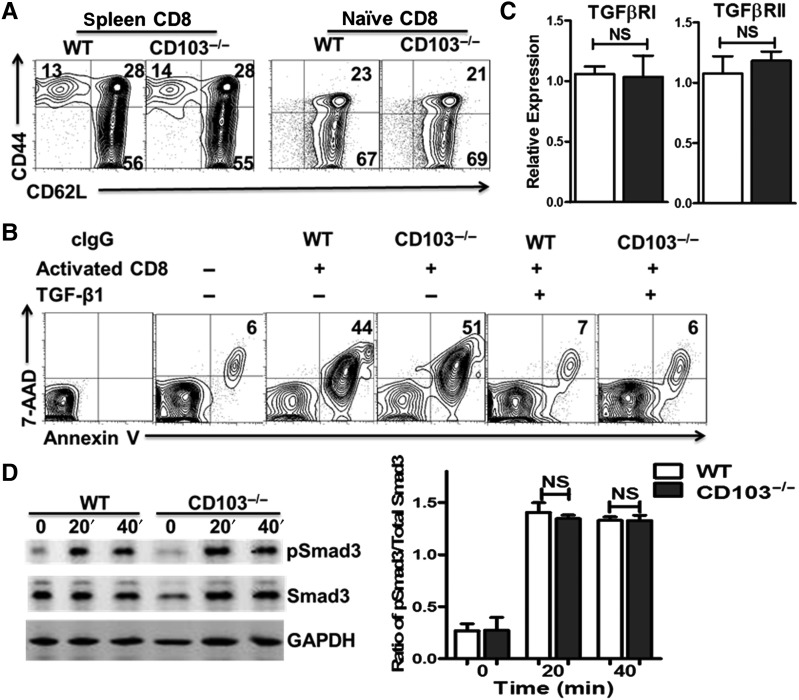

Lower levels of Foxp3 induction on CD8+ cells isolated from CD103−/− mice are not due to the reduced response to TGF-β

Given that CD44hi memory and CD62Lhi naïve cells have a different ability to be induced by Foxp3 expression following TGF-β treatment (Zheng et al., 2007), we have examined the phenotypic status of CD8+ cells in CD103−/− mice. As in WT mice, the majority of CD8+ cells are CD62LhiCD44low in CD103−/− mice (Figure 5A). Moreover, very few of the naïve CD8+ cells are in the CD44hi population (Figure 5B), excluding the possibility that the altered ratio of CD8 memory to naïve cells in CD103−/− mice leads to low Foxp3 induction.

Figure 5.

Lower levels of Foxp3 induction on CD8+ cells isolated from CD103−/− mice are not due to the reduced response to TGF-β. (A) CD62L and CD44 expression of splenocytes and naïve CD8+ T cells isolated from WT and CD103−/− mice was determined by flow cytometry. Typical FACS plots are shown. (B) Naïve CD8+ cells isolated from C57BL/6 WT and CD103−/− mice (both are Thy 1.2) were cultured with irradiated BALB/c (Thy 1.1) non-T cells (1:1), with or without BALB/c splenic CD4+ cells for 2 days, and 2 ng/ml TGF-β was added as indicated. The expression of Annexin-V and 7-AAD among CD4+ Thy1.1+ cells were determined by FACS on Day 2. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) TβRI and TβRII expression in naïve CD8+ cells from WT and CD103−/− mice was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Data are mean ± SEM of triplicate wells and representative of three independent experiments with similar results. NS, no significance. (D) Naïve C8+ cells from the indicated mice were stimulated with TGF-β (2 ng/ml) for 0, 20, and 40 min. Total and phosphorylated Smad3 levels were analyzed by Western blot in different groups. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

To determine whether the CD8+ cell subset in CD103−/− mice has a functional defect, we performed standard allogenic killing assays, because the cytotoxicity developed by activated CD8+ cells represents one of the best functional definitions of this cell population. To this end, CD8+ cells isolated from C57BL/6 CD103−/− and WT mice were stimulated with allogenic antigens from BALB/C mice. We demonstrated that the activated CD8+ cells from CD103−/− mice had a similar target cell killing capacity relative to that from WT mice. However, these cells completely lost their killing ability following the priming with TGF-β (Figure 5B). Accordingly, both Foxp3−CD103+ and Foxp3+CD103+ Treg subsets expressed lower levels of Granzyme A, Granzyme B, and Perforin compared with CD8med control cells (Supplementary Figure S2A). Moreover, the suppressive ability of Foxp3−CD103+ and Foxp3+CD103+ CD8+ iTreg subsets against T cell proliferation was similar for cells generated from Perforin−/− or Granzyme B−/− mice relative to WT mice (Supplementary Figure S2B), indicating that CD8+ iTregs suppress immune responses through non-cytotoxic mechanisms.

We further asked whether different TGF-β-induced responses of naïve CD8+ precursor cells isolated from CD103−/− mice account for the observed differential Foxp3 induction. As shown in Figure 5C, both naïve CD8+ cells isolated from CD103−/− and WT mice expressed TβRI and TβRII at identical levels. When stimulated with TGF-β for 20–40 min, they showed similar activation of Smad3 (Figure 5D), suggesting that the ability of naïve CD8+ cells to respond to TGF-β is not compromised in CD103−/− mice.

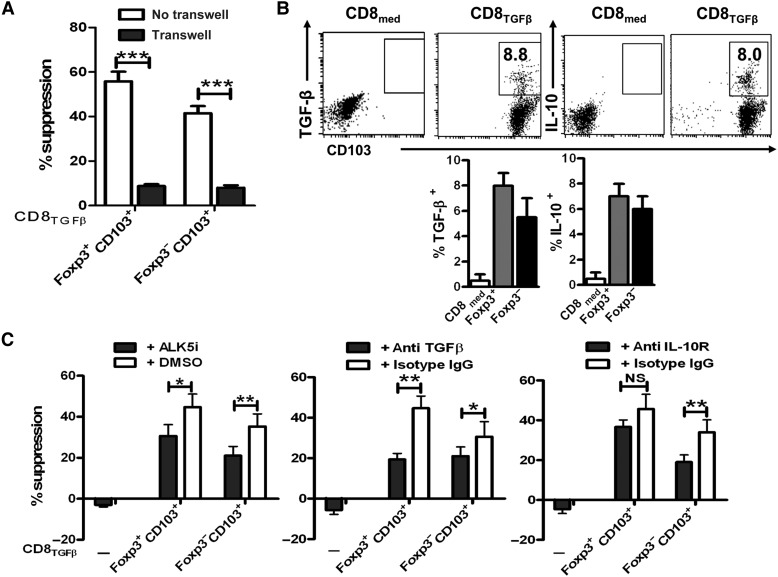

The suppressive activity of CD8+ Treg cells is cell contact dependent and also requires IL-10 and TGF-β signaling pathways

The co-culture of T cells and Foxp3−CD103+ or Foxp3+CD103+ cells isolated from CD8TGF-β cells showed a consistent and profound suppression of both CD8+Foxp3−CD103+ and CD8+Foxp3+CD103+ subsets against T cell proliferation. Interestingly, this activity was completely dependent on cell contact since it was significantly abolished when a Transwell membrane was inserted, allowing penetration of soluble factors but not cell contact (Figure 6A). Previous studies have demonstrated that cell contact is also acquired for the suppression of both natural and induced CD4+ Treg subsets in vitro (Zheng et al., 2004).

Figure 6.

The suppressive activity of CD8+ Treg cells is dependent on IL-10 and TGF-β signals in vitro. CD8med and CD8TGFβ cells were induced as in Figure 1A. (A) CD103+Foxp3+ and CD103+Foxp3− cell subsets were sorted and their suppressive activity was determined as described in Figure 1B. In some experiments, a transwell was inserted between Treg and responder cells. Values are mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001. (B) The expression of membrane-bound LAP (TGF-β1), intracellular IL-10 production, and CD103 by CD8med and CD8TGFβ was measured by FACS. Representative dot plot from four independent experiments was shown (upper). The histogram shows TGF-β and IL-10 expression gated on Foxp3+ and Foxp3− population (bottom). (C) The experiments were similarly conducted as A, and ALK5i, anti-TGFβ, anti-IL-10R, and DMSO or isotype control IgG (all at 10 µg/ml) were added to the culture wells. The data are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. NS, no significance; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

There was already considerable evidence indicating that the function of Treg is also associated with TGF-β and IL-10 (Asseman et al., 1999; Nakamura et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2004). We then evaluated whether these cytokines are involved in the suppression exerted by CD8+ Treg subsets. Unlike CD8med cells, CD8TGF-β cells expressed both surface TGF-β (latency-associated peptide, LAP) and intracellular IL-10 (Figure 6B). LAP is considered a membrane-bound form of TGF-β and the antibody used in this study is able to identify both active and functional surface-bound TGF-β forms (Horwitz et al., 2008; Gandhi et al., 2010).

As shown in Figure 6C, the addition of anti-TGF-β antibody or TβRI (ALK5) antagonist (ALK5i) significantly diminished the suppression by both Foxp3−CD103+ and Foxp3+CD103+ iTreg cell subsets in vitro. The addition of anti-IL-10R, but not control isotype IgG, also significantly reverted the suppression by Foxp3−CD103+ cells, while this effect was mild for CD8+Foxp3+CD103+ Treg subset. Antibodies and ALK5i slightly increased T responder cell proliferation in the baseline cultures, indicating that the effect of neutralizing antibodies or antagonist is mostly related to Treg subsets (Figure 6C).

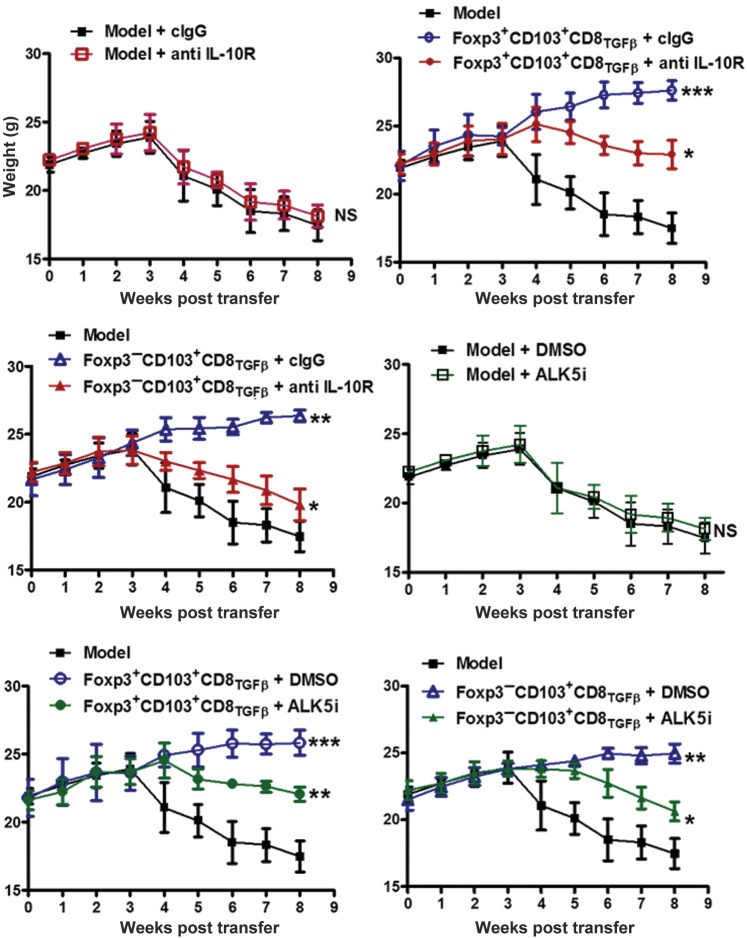

To implicate the role of IL-10 and TGF-β in the suppression by CD8+ Treg subset in vivo, the neutralizing antibodies and TβRI antagonist were also used in the colitis model. As shown in Figure 7, both anti-IL-10R antibody and TβRI antagonist significantly reverted the suppression of bodyweight loss by both CD8+Foxp3+ and CD8+Foxp3− cell populations in the colitis model. Although previous study has suggested that TGF-β, which does not have to be Treg-derived, suppresses colitis (Fahlen et al., 2005), the neutralizing antibody or antagonist alone did not significantly affect colitis progression in our in vivo study (Figure 7), excluding the non-specific role of these reagents in colitis itself. This is possible that low doses of antibodies may not significantly affect endogenous TGF-β signaling but specifically block the TGF-β signal produced by CD8+ iTregs. Taken together, these studies suggest that TGF-β can induce a novel CD8+CD103+Foxp3− Treg cell population independent of Foxp3+CD8+ iTreg cells. These cells suppress T cell-mediated immune responses through IL-10 and TGF-β signals rather than cytotoxicity.

Figure 7.

CD8+ Treg cells suppress colitis through IL-10 and TGF-β signals in vivo. CD8+ iTreg cells were induced as described in Figure 1A and sorted for two populations, CD103+Foxp3+ and CD103+Foxp3− cells. The colitis model was induced in Rag2−/− mice by injection of CD4+CD45RBhi T cells (5 × 105). CD103+Foxp3+ or CD103+Foxp3− cells (1 × 106 each) were co-injected with CD4+CD45hi cells to Rag2−/− mice. The weight of mice was determined weekly for 8 weeks. In some groups, ALK5i (0.5 mg/mouse), anti-IL-10R (0.25 mg/kg body weight), or isotype-matched IgG1 antibody was administered i.p. weekly to mice for a total of 6 injections. Each group has 6 mice and experiments were repeated twice. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. NS, no significance; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 ALK5i or anti IL-10R group vs. control group.

Discussion

Treg cells are crucial for the prevention of autoimmune diseases and the maintenance of immune tolerance. While the study of phenotypic and functional characteristics of Treg cells has been mostly focused on CD4+ Treg subsets including natural and induced Treg cells, the CD4+ Treg counterpart, CD8+ Treg cells have gained recent attention as an interesting regulator (Kapp and Bucy, 2008; Kim et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2013).

CD8+ Treg cells may not share their functional or phenotypic characteristics with CD4+ Treg cells. Several studies have identified that the CD8+ Treg cells predominately exist in immune privilege sites or organs, particularly in eye (Sharafieh et al., 2011). Human CD8+ Treg cells occur spontaneously in vivo, mostly in rejection-free cardiac transplant recipients (Ciubotariu et al., 2001), type 1 diabetes patients following anti-CD3 treatment (Bisikirska et al., 2005) or lupus patients in remission following peptides treatment (Hahn et al., 2005; Kang et al., 2005).

CD8+ Treg cells play a unique clinical role in the therapy of some diseases. Autologous hemopoietic stem cell transplantation can induce long-term remission in refractory lupus patients, which induces more potent CD8+ Treg than CD4+ Treg cells (Zhang et al., 2009a). CD8+ Treg cells also appeared to be crucial for protecting against graft-verse-host disease (GVHD)-induced lethality since ∼70% of the inducible and functional Treg cells are CD8+ cells following infusion of donor CD4+ nTreg cells (Sawamukai et al., 2012). Importantly, CD8+Foxp3+ Treg cells were sufficient to prevent GVHD mortality in the complete absence of CD4+ Treg cells, indicating the exclusive role of CD8+ Treg in some circumstances (Beres et al., 2012). Alloantigen-specific CD8+Foxp3+ Treg cells can protect skin allograft via inducing new generation of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells and concurrently suppressing effector T cell expansion, indicating the interaction between two populations of Treg cells (Lerret et al., 2012).

Although there are at least two populations of natural CD8+ Treg cells that have been identified including thymus-derived CD8+CD25+Foxp3+ and CD8+CD122+ cells, the frequency of CD8+ natural Treg cells is much lower relative to natural CD4+ Treg cells (Cosmi et al., 2003). The consequence of depletion of thymic murine CD8+ natural T cells is not known. Interestingly, most CD8+ Treg cells identified in the periphery are related to inducible cell populations including CD8+CD28−, CD8+CD103+, and CD8+Foxp3+ cells (Kapp and Bucy, 2008). Additionally, the majorities of these cells are antigen-specific and can be observed in patients with allograft transplantation and tumor, or in the decidua of pregnant women (Shao et al., 2005; Tilburgs et al., 2009).

Using antigen-specific transgenic strategy and alloantigen-specific mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), TGF-β was able to induce CD8+ cells to become CD8+ Treg cells. These cells displayed a potent suppressive activity in preventing allograft rejection in transplantation models (Kapp et al., 2006).

We now provide the evidence that polyclonal CD8+ Treg cells can be induced ex vivo with TGF-β. These TGF-β-activated CD8+ Treg cells were not antigen-specific but had potent suppressive activities in autoimmune disease animal model. Unlike CD4+ Treg cells, the newly identified CD8+CD103+ Treg cell population expressed much lower Foxp3 and did not require the existence of Foxp3 for the suppressive function. Interestingly, we found that CD103 expression was essential for the development of this new CD8+ Treg cell population.

We have also demonstrated that CD8+CD103+Foxp3− cells suppressed T cell responses independent of their cytotoxicity. These cells expressed low levels of cytolytic proteins including Granzyme A, Granzyme B, and Perforin. The Treg cells did not induce T responder and APC cells apoptosis or death when co-cultured with those cells. Furthermore, we found that both Foxp3−CD8+ and Foxp3+CD8+ cells displayed similar suppressive activity no matter they were induced from WT mice or Perforin−/− or Granzyme B−/− mice. Thus, we have identified a new CD8+ Treg cell population that requires CD103 for their development and function independent of the cytotoxic effect.

It is clear that cell contact is needed for the suppressive activity of CD8+ Treg cells in an in vitro culture, consistent with that observed in other CD4+ and CD8+ Treg subsets. It is possible that CD8+ Treg cells need APC to exert their suppression where Treg and T responder cells were brought together to contact APC in vitro.

The αEβ7 integrin CD103, a receptor for the epithelial cell-specific ligand E-cadherin, was first reported to be expressed on CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) that may participate in the response to allogeneic epithelial cells and affect allograft survival in transplant tissue, indicating that CD8+CD103+ CTL cells are linked to graft rejection (Hadley et al., 1999). Nonetheless, other reports have recently shown that CD8+ T cells do not initially express CD103 but its expression is up-regulated via a TGF-β-related pathway after cell migration to the allograft site (Wang et al., 2004). In addition, CD8+CD103+ cell numbers increased in tolerant liver transplantation and these cells were shown to have immunosuppressive activity. Thus, the functional features of CD8+CD103+ cells under transplantation condition merit further scrutiny. Similarly, these cells are known to be increased in certain tumors and their functional role in these tumors may be related to immune derivation. CD8+CD103+ cells are also increased in pregnant woman (Hadley et al., 1997; Shao et al., 2005), implicating their role in the maintenance of fetal tolerance.

CD103 expression is important for the development and function of CD8+Foxp3− Treg cells. In our study, lack of CD103 affects CD8+ but not CD4+ Treg cell development. It is possible that CD103 binding to E-cadherin can regulate IL-10 production and membrane-bound TGF-β expression since only TGF-β-activated CD8+CD103+ cells express these suppressive cytokines. As active TGF-β cannot be detected on T cells and LAP represents the membrane-bound form of TGF-β (Zheng et al., 2008; Gandhi et al., 2010), we used anti-LAP antibody to determine membrane-bound TGF-β levels. Using neutralizing antibodies to TGF-β or IL-10R, and TβRI antagonist, we demonstrated that CD8+ Treg cells depend mainly upon IL-10 and TGF-β signaling pathways.

It is possible that CD103 expression on CD8+ Treg cells also influences their trafficking. It has been known that CD103+ cells predominately migrate to skin and mucous membranes (Jenkinson et al., 2011). Treg cells need to migrate to inflammatory sites to exert their suppressive activity (Zhang et al., 2009b). Given that CD8+ Treg cells express much higher CD103 compared with CD4+ Treg cells, it is likely that CD8+ Treg cells may exhibit an enhanced ability to migrate to inflammatory sites of some diseases and have a superior effect.

In the present study, we have identified a new polyclonal CD8+ Treg cell population that can be induced by TGF-β ex vivo. Recent study has demonstrated that polyclonal CD4+ Treg cells suppress autoimmunity (Lan et al., 2012a, b). This novel CD8+ Treg population does not express Foxp3 but does require CD103 for the development. These cells suppress immune responses and T cell-mediated diseases through IL-10 and TGF-β pathways rather than the cytotoxicity. Thus, TGF-β is able to induce both polyclonal Foxp3+ and Foxp3− CD8+ Treg cells, which may have important clinical value in treating autoimmune diseases since the identification of antigens in these diseases is difficult and the use of polyclonal Treg cells might be a better and more appropriate strategy. The current study indicates that in addition to CD4+ iTregs, generation of polyclonal CD8+ iTreg cells by TGF-β may have considerable therapeutic potential for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male or female C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b), BALB/c (H-2d), CD103−/− (C57BL/6 background), Rag2−/− (C57BL/6 background) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 Foxp3gfp knock-in mice were generously provided by Dr Talil Chatilla (UCLA). CD103−/− Foxp3gfp knock-in mice were produced by backcrossing C57BL/6 Foxp3gfp knock-in mice with CD103−/− mice. Animals were used for experiments at 8–12 weeks of age. All animals were treated according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animal with the approval of the University of Southern California Committees for the use and care of animals.

Antibodies for staining using flow cytometry

The following immunofluorescence-conjugated mouse antibodies were used for flow cytometric analysis: PE-IL-10 (JES5-16E3) and PE-IL-2 (JES6-5H4) from BD Pharmingen; PerCP/Cy5.5- or PE-CD103 (2E7), PE- or PerCP-CD8 (53–6.7), PE-CD25 (PC61), PE-GITR (YGITR 765), PE-TNFRII/p75 (TR75-89), PE-CD62L (MEL-14), PE-ICOS (7E.17G9), Alexa Fluor 647-Granzyme B (GB11), APC-LAP (TGFβ1) (TW7-16B4), PE-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and Alexa Fluor 488-Foxp3 (150D) from Biolegend; PE-Granzyme A (3G8.5) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; PE-CTLA-4 (UC10.4B9) from eBiosciences.

Each sample was stained with mAbs to markers indicated above, and analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer using the Cell Quest Software (Becton Dickinson). For intracellular staining, such as Foxp3, CTLA-4, and Granzyme A and B, cells were stained with surface antigen CD4 or CD8 (eBioscience) and further fixed and permeabilized for intracellular staining. For inflammatory cytokine staining, cells were prepared and cultured with 0.25 μg/ml Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate (PMA) and 0.25 μg/ml ionomycin (Calbiochem) for 5 h in the presence of brefeldin A 5 μg/ml (Calbiochem) for the last 4 h. Cytokine expression was measured by FACS. Histograms were prepared using the FlowJo Software (Tree star Inc.).

The generation of CD4+ or CD8+ iTreg cells ex vivo

For the induction of CD4+ Treg cells, naïve CD4+CD25−CD62Lhi T cells were isolated from spleen cells of C57BL/6 mice or C57BL/6 Foxp3gfp knock-in mice using naïve CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). For CD8+ cell separation, the enriched T cells by collecting non-adherent spleen cells passing through nylon wool column were stained with PE-conjugated CD4, CD11b, B220 antibodies, then depleted by MACS with anti-PE microbeads. The purity of CD8+ cells was >96%. Cells were stimulated with plate-bound mouse anti-CD3 (1 µg/ml, Biolegend), soluble mouse anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml, Biolegend), and rhIL-2 (100 U/ml, R&D systems) with or without rhTGF-β (2 ng/ml, Humanzyme) for 3 days. RPMI 1640 supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 10 mM HEPES (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (HyClone Laboratories) was used for all cultures. Cells were harvested to determine the expression of Foxp3 by flow cytometry.

In vitro suppression assay

Fresh T responder cells labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) were stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (0.025 µg/ml) and irradiated non-T cells (30 Gy, 1:1 ratio) for 3 days with or without condition cells. T cell proliferation was determined by CFSE dilution rate after 3 days of culture. To examine the function of different subsets of CD4TGFβ and CD8TGFβ cells, Foxp3gfp knock-in mice were used for the isolation of naïve CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. After 3 days of culture, cells were sorted for different subsets by using a FACS Aria II high speed cell sorter. The suppressive activity of these cell subsets was conducted as described above.

Apoptosis assay

Naïve CD8+ cells isolated from C57BL/6 (Thy1.2) or CD103−/− (C57BL/6 background, Thy1.2) mice were stimulated with irradiated non-T cells from BALB/c (Thy 1.1), with or without CD4+ cells isolated from BALB/c for 2 days. The cells were stained with Annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) using an Annexin V apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. Both Annexin-V and 7-AAD expression was analyzed by gating on CD4+ and Thy 1.1+ cells.

Colitis model

Half million CD4+CD45RBhi splenocytes from naïve C57BL/6 mice were sorted (95%–100% purity) and intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected into Rag2−/− mice. Some groups also received 1 × 106 cells of indicated subsets. To determine the suppressive mechanisms of CD8TGFβ subsets in vivo, anti-IL-10R (0.25 mg/kg body weight), isotype-matched IgG1 antibody, or ALK5 inhibitor (ALK5i; LY-364947, Sigma, 0.5 mg/mouse) were administered i.p. weekly for a total of six injections. Mice were monitored regularly and sacrificed upon evidence of significant clinical symptoms including weight loss and/or diarrhea (∼8–12 weeks after cell injection). Colon samples were prepared as previously described (Izcue et al., 2008) and scored based on the following criteria: degree of epithelial hyperplasia and goblet cell depletion, leukocyte infiltration in lamina propria, area of tissue affected, and the presence of markers of severe inflammation (crypt abscesses, submucosal inflammation, and ulcers). Sections were scored blindly by two independent pathologists.

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). The cDNA was synthesized using iScript cDNA synthesis kit. The real-time quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Green I and iCycle-iQ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and samples were run in triplicate. Primer sequences were as follows: TGFβRI, 5′-GGTCTTGCCCATCTTCACAT-3′ and 5′-CACTCTGTGGTTTGGAGCAA-3; TGFβRII, 5′-GGC TCT GGT ACT CTG GGA AA-3′ and 5′-AAT GGG GGC TCG TAA TCC T-3′.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was performed as previously described (Zhou et al., 2011). Briefly, naïve CD8+ cells isolated from both WT and CD103−/− mice were cultured for 0–40 min with TGF-β (2 ng/ml, R&D Systems) and lysed by addition of M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific) in the presence of protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min on ice. Samples were heated in SDS-PAGE loading buffer at 95°C for 3 min and then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with antibodies against Smad3, phospho-Smad3 (Cell Signaling Technology), or GAPDH (Millipore). Signals were developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Thermo).

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Data were analyzed using the Student's t-test for comparison between two groups or ANOVA for comparison among multiple groups as appropriate. Colitis scores were compared using the Mann–Whitney test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Journal of Molecular Cell Biology online.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (AR059103 and AI084359), ACR Within Our Reach Fund, Arthritis Foundation and Wright Foundation, Science and Technology Committee Project of Shanghai Pudong new area (PKJ2009-Y41), Science and Technology Project of Guangdong Province, China (No.S2012010009667), and 985 Research Project from Sun Yat-sen University.

Conflict of interest:

none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- Asseman C., Mauze S., Leach M.W., et al. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:995–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. doi:10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beres A.J., Haribhai D., Chadwick A.C., et al. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are induced during graft-versus-host disease and mitigate disease severity. J. Immunol. 2012;189:464–474. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200886. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1200886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisikirska B., Colgan J., Luban J., et al. TCR stimulation with modified anti-CD3 mAb expands CD8+ T cell population and induces CD8+CD25+ Tregs. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2904–2913. doi: 10.1172/JCI23961. doi:10.1172/JCI23961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Jin W., Hardegen N., et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25− naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. doi:10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciubotariu R., Vasilescu R., Ho E., et al. Detection of T suppressor cells in patients with organ allografts. Hum. Immunol. 2001;62:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00226-3. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(00)00226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmi L., Liotta F., Lazzeri E., et al. Human CD8+CD25+ thymocytes share phenotypic and functional features with CD4+CD25+ regulatory thymocytes. Blood. 2003;102:4107–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1320. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-04-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlen L., Read S., Gorelik L., et al. T cells that cannot respond to TGF-beta escape control by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:737–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040685. doi:10.1084/jem.20040685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi R., Farez M.F., Wang Y., et al. Cutting edge: human latency-associated peptide+ T cells: a novel regulatory T cell subset. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4620–4624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903329. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley G.A., Bartlett S.T., Via C.S., et al. The epithelial cell-specific integrin, CD103 (alpha E integrin), defines a novel subset of alloreactive CD8+ CTL. J. Immunol. 1997;159:3748–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley G.A., Rostapshova E.A., Gomolka D.M., et al. Regulation of the epithelial cell-specific integrin, CD103, by human CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes. Transplantation. 1999;67:1418–1425. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906150-00005. doi:10.1097/00007890-199906150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B.H., Singh R.P., La Cava A., et al. Tolerogenic treatment of lupus mice with consensus peptide induces Foxp3-expressing, apoptosis-resistant, TGFbeta-secreting CD8+ T cell suppressors. J. Immunol. 2005;175:7728–7737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S., Nomura T., Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi:10.1126/science.1079490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz D.A., Zheng S.G., Gray J.D. Natural and TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells are not mirror images of each other. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.it.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izcue A., Hue S., Buonocore S., et al. Interleukin-23 restrains regulatory T cell activity to drive T cell-dependent colitis. Immunity. 2008;28:559–570. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.019. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson S.E., Whawell S.A., Swales B.M., et al. The alphaE(CD103)beta7 integrin interacts with oral and skin keratinocytes in an E-cadherin-independent manner. Immunology. 2011;132:188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03352.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H.K., Michaels M.A., Berner B.R., et al. Very low-dose tolerance with nucleosomal peptides controls lupus and induces potent regulatory T cell subsets. J. Immunol. 2005;174:3247–3255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp J.A., Bucy R.P. CD8+ suppressor T cells resurrected. Hum. Immunol. 2008;69:715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.07.018. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapp J.A., Honjo K., Kapp L.M., et al. TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells activated in the presence of TGFbeta express FoxP3 and mediate linked suppression of primary immune responses and cardiac allograft rejection. Int. Immunol. 2006;18:1549–1562. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl088. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.J., Verbinnen B., Tang X., et al. Inhibition of follicular T-helper cells by CD8+ regulatory T cells is essential for self tolerance. Nature. 2010;467:328–332. doi: 10.1038/nature09370. doi:10.1038/nature09370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q., Fan H., Quesniaux V., et al. Induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells: a potential new weapon to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases? J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012a;4:22–28. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr039. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q., Zhou X., Fan H., et al. Polyclonal CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells induce TGFbeta-dependent tolerogenic dendritic cells that suppress the murine lupus-like syndrome. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012b;4:409–419. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs040. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjs040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret N.M., Houlihan J.L., Kheradmand T., et al. Donor-specific CD8+ Foxp3+ T cells protect skin allografts and facilitate induction of conventional CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:2335–2347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04120.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Wang J., Zhang F., et al. Role of SMAD and non-SMAD signals in the development of Th17 and regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4295–4306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903418. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Kitani A., Fuss I., et al. TGF-beta 1 plays an important role in the mechanism of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity in both humans and mice. J. Immunol. 2004;172:834–842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifa'i M., Kawamoto Y., Nakashima I., et al. Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1123–1134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040395. doi:10.1084/jem.20040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:345–352. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. doi:10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamukai N., Satake A., Schmidt A.M., et al. Cell-autonomous role of TGFbeta and IL-2 receptors in CD4+ and CD8+ inducible regulatory T-cell generation during GVHD. Blood. 2012;119:5575–5583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-367987. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-07-367987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao L., Jacobs A.R., Johnson V.V., et al. Activation of CD8+ regulatory T cells by human placental trophoblasts. J. Immunol. 2005;174:7539–7547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafieh R., Lemire Y., Powell S., et al. Immune amplification of murine CD8 suppressor T cells induced via an immune-privileged site: quantifying suppressor T cells functionally. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund K., Ruckert B., Ouaked N., et al. Unique phenotype of human tonsillar and in vitro-induced FOXP3+CD8+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2124–2130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802271. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0802271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suciu-Foca N., Manavalan J.S., Cortesini R. Generation and function of antigen-specific suppressor and regulatory T cells. Transpl. Immunol. 2003;11:235–244. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(03)00052-2. doi:10.1016/S0966-3274(03)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilburgs T., Scherjon S.A., Roelen D.L., et al. Decidual CD8+CD28− T cells express CD103 but not perforin. Hum. Immunol. 2009;70:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Yuan R., Feng Y., et al. Regulation of CD103 expression by CD8+ T cells responding to renal allografts. J. Immunol. 2004;172:214–221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Bertucci A.M., Ramsey-Goldman R., et al. Regulatory T cell (Treg) subsets return in patients with refractory lupus following stem cell transplantation, and TGF-beta-producing CD8+ Treg cells are associated with immunological remission of lupus. J. Immunol. 2009a;183:6346–6358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901773. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0901773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Schroppel B., Lal G., et al. Regulatory T cells sequentially migrate from inflamed tissues to draining lymph nodes to suppress the alloimmune response. Immunity. 2009b;30:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.022. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S.G., Gray J.D., Ohtsuka K., et al. Generation ex vivo of TGF-beta-producing regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25− precursors. J. Immunol. 2002;169:4183–4189. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S.G., Wang J.H., Gray J.D., et al. Natural and induced CD4+CD25+ cells educate CD4+CD25− cells to develop suppressive activity: the role of IL-2, TGF-beta, and IL-10. J. Immunol. 2004;172:5213–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S.G., Wang J., Wang P., et al. IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta to convert naive CD4+CD25− cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:2018–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng S.G., Wang J., Horwitz D.A. Cutting edge: Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by IL-2 and TGF-beta are resistant to Th17 conversion by IL-6. J. Immunol. 2008;180:7112–7116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Liu Y., Liu M., et al. Human CD8+ regulatory T cells inhibit GVHD and preserve general immunity in humanized mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:168ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004943. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Wang J., Shi W., et al. Isolation of purified and live Foxp3+ regulatory T cells using FACS sorting on scatter plot. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;2:164–169. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq007. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Xia Z., Lan Q., et al. BAFF promotes Th17 cells and aggravates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023629. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.