Abstract

Background: falls in hospitals are a major problem and contribute to substantial healthcare burden. Advances in sensor technology afford innovative approaches to reducing falls in acute hospital care. However, whether these are clinically effective and cost effective in the UK setting has not been evaluated.

Methods: pragmatic, parallel-arm, individual randomised controlled trial of bed and bedside chair pressure sensors using radio-pagers (intervention group) compared with standard care (control group) in elderly patients admitted to acute, general medical wards, in a large UK teaching hospital. Primary outcome measure number of in-patient bedside falls per 1,000 bed days.

Results: 1,839 participants were randomised (918 to the intervention group and 921 to the control group). There were 85 bedside falls (65 fallers) in the intervention group, falls rate 8.71 per 1,000 bed days compared with 83 bedside falls (64 fallers) in the control group, falls rate 9.84 per 1,000 bed days (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–1.22; P = 0.51). There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to time to first bedside fall (adjusted hazard ratio (HR), 0.95; 95% CI: 0.67–1.34; P= 0.12). The mean cost per patient in the intervention group was £7199 compared with £6400 in the control group, mean difference in QALYs per patient, 0.0001 (95% CI: −0.0006–0.0004, P= 0.67).

Conclusions: bed and bedside chair pressure sensors as a single intervention strategy do not reduce in-patient bedside falls, time to first bedside fall and are not cost-effective in elderly patients in acute, general medical wards in the UK.

Trial registration: isrctn.org identifier: ISRCTN44972300.

Keywords: in-patient falls, falls, bed sensors, older people

Introduction

Falls in hospitals are a major problem and contribute to substantial healthcare burden [1, 2]. Across England and Wales, ∼152,000 falls are reported in acute hospitals every year [3]. They result in physical and psychological morbidity for patients and large healthcare costs, including the costs of treating injuries, increased hospital stay, complaints and litigation [4–6]. Elderly patients admitted acutely to hospital are particularly vulnerable to falling [2], with more than half of these falls occurring at the bedside [3].

Trials of single interventions to prevent falls in acute hospital care have not demonstrated a convincing reduction in falls [7–10]. Multi-factorial interventions have been investigated with mixed results [11–14]. A cochrane review concluded that although multi-factorial interventions prevent falls in hospitals, no specific recommendations could be made regarding the effective components of these interventions [15]. Additionally, multi-factorial interventions can be difficult and costly to implement [16]. Therefore, there is a need to develop and evaluate effective single intervention strategies in acute hospital care.

Advances in assistive technology such as bed and bedside chair pressure sensors afford innovative approaches to reducing in-patient bedside falls [17]. These are increasingly being used in healthcare facilities [18], and have been endorsed by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations [19]. However, a recent cluster randomised trial in the USA found no reduction in bedside falls using these sensors [10]. Whether these findings are valid in other settings and whether using a more advanced radio-pager system is clinically effective and cost effective is unknown. We report the results of a large, pragmatic, parallel arm, randomised controlled trial of bed and bedside chair sensors using radio-pagers to reduce in-patient bedside falls in acute, general medical, elderly care wards in a UK hospital.

Methods

Participants

All patients admitted to the hospital from the medical admissions unit to three acute, general medical elderly care wards (within 24 h) at the Queen's Medical Centre (1800 beds, serving a population of 680,000), Nottingham, UK were eligible for inclusion into the trial. Participants were individually randomised to receive either a bed and bedside chair pressure sensor linked to a radio-pager (intervention group) or no sensor (control group), for the duration of their admission on the elderly care ward. Exclusion criteria were being permanently bed bound prior to admission, moribund/unconscious, on end of life care or previous inclusion in the trial on an earlier admission. Recruitment occurred between January 2009 and March 2011, with the final patient being discharged 29 March 2011. All patients were asked to give written, informed consent. In those who lacked capacity, subjects were recruited in consultation with family or professional consultees, in keeping with the research provisions of the Mental Capacity Act of England, and as approved by a local Research Ethics Committee.

Randomisation

Subjects were randomised to the intervention group or the control group using a web based randomisation service provided by the Clinical Trials Support Unit, University of Nottingham. The allocation schedule was generated using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind participants or those providing medical or nursing care to the intervention or control group allocation. A feasibility study [20], prior to this research demonstrated that nurses were able to identity which patients had the dummy sensors and which the active sensors by the end of a single nursing shift. Data were extracted from incident forms and analysed by members of the research team, blind to intervention allocation.

Withdrawals

Participants were free to withdraw from the trial at any stage. Data were included in the analyses up to the point of withdrawal. Those who were deemed to be at risk of harm resulting from the sensor equipment (e.g. in cases of confusion where participant mis-handled equipment) had the sensor removed but data collection continued and these participants were included in the analysis in the group to which they had been randomised.

Intervention

The sensor units were leased from an independent manufacturer and consisted of a battery-operated bed and bedside chair pressure sensor linked wirelessly to a handheld battery-operated radio-pager (details of the devices have been previously described [20]). When a participant left the bed or bedside chair, a radio signal alert was transmitted from a transmitter box attached to the foot of the participant's bed, to the radio-pager carried by a member of the nursing team, which provided the location of the participant. An absence of pressure on the sensor of 5 s or more triggered an alert. A central receiver on each ward recorded all alerts, which were collected by the research team.

The research team fitted the sensor units, reviewed the equipment daily, replaced batteries as required and recorded sensor unit problems, using personal diaries. The pagers were carried, where possible by the nursing aides, who were more flexible in their daily duties (i.e. less likely to be involved in medication rounds, interviews with relatives). The total registered nurse and nurse aide allocation per 28-bedded ward was eight on the morning shift (7 a.m.–2 p.m.), six in the afternoon shift (2 p.m.–7 p.m.) and four overnight (7 p.m.–7 a.m.), with each shift including at least two nursing aides. No ward had more than 10 units linked to two pagers in operation at any one time, therefore the most a single registered nurse or nurse aide would be responsible for was five sensors at any one time. Face-to-face training based on our pilot study [17] was undertaken with the ward staff. New ward staff members were trained as necessary and refresher demonstrations provided monthly.

Standard care for both groups was provided by a geriatric ward-based team comprising geriatricians, nurses, occupational therapists and physiotherapists delivering routine geriatric medical care.

Outcome measures

As the aim of providing bed and bedside chair sensors is to reduce bedside falls, the primary outcome measure was the number of in-patient bedside falls per 1,000 bed days from time of randomisation to date of discharge, death or study withdrawal, whichever occurred soonest. A bedside fall was defined as an unexpected event in which the participant came to rest on the ground, floor or lower level in the area around the bedside, with the bedside being defined as the area encompassed by the curtained area surrounding the bed. For patients in side rooms, the bedside was defined as the area of the room.

Bedside falls were ascertained from incident reporting forms, completed by the ward clinical teams, the use of which was mandatory within the hospital and enforced by systematic quality assurance processes (clinical governance) used in UK hospitals. These forms included details of the fall event, time, injuries sustained and subsequent actions taken. The forms were collected from participating wards each day by the research team, blind to group allocation.

Secondary outcome measures were:

Number of injurious in-patient bedside falls per 1,000 bed days, defined as falls resulting in abrasion, bruise, swelling, cut, laceration, dislocation, fracture or muscle sprain or strain.

Activities of daily living, measured using the Barthel ADL Index [21].

Fear of falling, measured using the modified falls efficacy scale (MFES) [22].

Length of hospital stay (number of days from admission to discharge or death, whichever occurred soonest)

Residential status on discharge (discharged to same address as on admission or discharged to another address).

Health related quality of life, measured using the EQ 5D questionnaire [23].

Statistical analysis

With 905 patients in each arm, the study had 80% power (with α = 0.05) to detect a 35% reduction in the rate of bedside falls among the intervention group, assuming a bedside falls rate of 8.0 per 1,000 beds days in the control group and an over dispersion parameter of 1.5 (to allow for non-independence of falls within individuals). The bedside falls rate was based on an anticipated mean number of falls per hospital admission of 0.15 and an average length of stay of 19 days. The 35% reduction was judged to be clinically meaningful and based on data from our previous 12-month pilot study [17]. This was a two-year (12-month pre-intervention observational study (n= 209) followed by a 12-month intervention study (n= 153)) conducted over a single ward, with bedside falls rates collected by an independent researcher from incident reporting forms, competed by the ward clinical staff.

Analyses were carried out on the basis of intention to treat. Where patients died in hospital or withdrew consent, follow-up was censored at the date of withdrawal/death with any events occurring before this date included in the analysis. On all other occasions, follow-up ended on the date of discharge (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix A).

Further details on project management, governance, confidentiality and administration may be found in the previously published protocol [20].

Results

Subjects

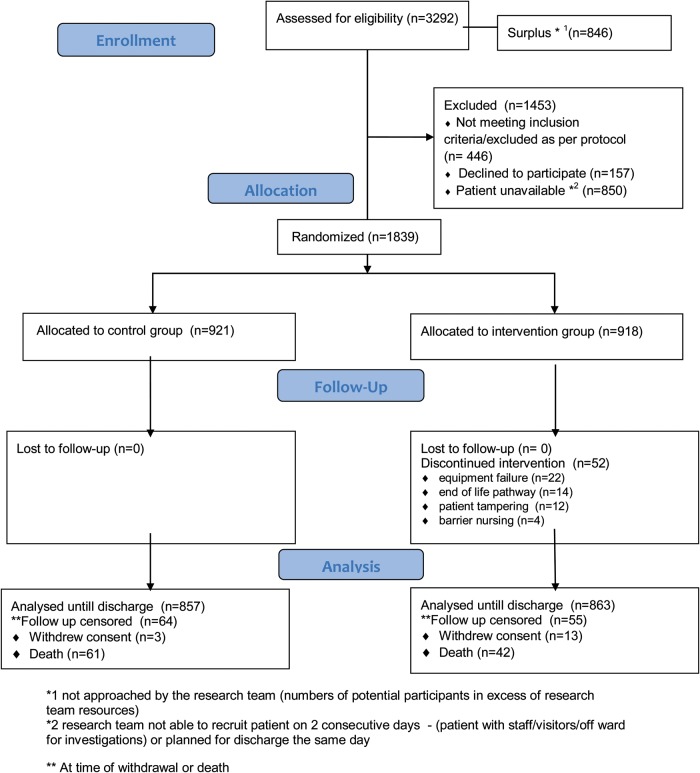

The flow of participants through the trial is shown in Figure 1. Of the 3,292 eligible patients 1,839 were randomised (918 to the intervention group and 921 to the control group). Baseline characteristics are shown in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix B, Table S1. The mean age at randomisation was 84.6 years (range 61–103 years), with a slight predominance of females (55% of total). 65.1% of the subjects had a median MMSE <23/30 and the median Barthel score was 12. The groups appeared well balanced at baseline.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. *1 not approached by the research team (numbers of potential participants in excess of research team resources). *2 research team not able to recruit patient on two consecutive days—(patient with staff/visitors/off ward for investigations) or planned for discharge the same day. **At the time of withdrawal or death.

Outcome measures

There were 85 bedside falls (65 fallers) in the intervention group, falls rate 8.71 per 1,000 bed days compared with 83 bedside falls (64 fallers) in the control group, falls rate 9.84 per 1,000 bed days, adjusted incident rate ratio 0.90 (95% CI: 0.66–1.22; P= 0.50). The rate of minor injuries is shown in Table 1. Sixteen bedside falls in the control group resulted in minor injury (6 bruises, 5 abrasions and 5 lacerations) and 24 in the intervention arm (4 bruises, 5 abrasions and 15 lacerations), (adjusted IRR, 1.60; 95% CI: 0.83–3.08; P= 0.15). The number of major injuries was small (three fractures in the control group and two in the intervention group).

Table 1.

Frequency of bedside falls by group (unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios)

| Total no. of bedside falls | Total no. of bed days | Incidence rate (falls/per 1,000 bed days) | Unadjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI)a | Adjusted incidence rate ratio (95% CI)b | P-value (from adjusted analysis) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of bed side falls | ||||||

| Intervention group | 85 | 9753.5 | 8.71 | 0.89 (0.65–1.20) | 0.90 (0.66–1.22) | 0.50 |

| Control group | 83 | 8433 | 9.84 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| No. of minor injurious (bruises, abrasions or lacerations) bed side fallsb | ||||||

| Intervention group | 24 | 9753.5 | 2.56 | 1.54 (0.80–2.97) | 1.60 (0.83–3.08) | 0.15 |

| Control group | 16 | 8433 | 1.66 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

aUnadjusted.

bAdjusted for age, gender, Barthel ADL index, previous fall and 30-item MMSE score.

There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to time to first bedside fall, adjusted HR, 0.95; 95% CI: 0.67–1.34; P= 0.12. Among those who fell, the median time between randomisation and first bedside fall was 7 days in the intervention group and 6 days in the control group. Stratifying by follow-up time showed a non-significant trend towards a greater reduction in early bedside falls risk, with the HR over the first 2 days being 0.60; 95% CI: 0.30–1.20; P= 0.11 compared with HR, 1.36; 95% CI: 0.82–2.23; P= 0.15, after 5 days.

None of the secondary outcomes differed significantly between the two groups (Table 2). Among patients who experienced one or more bedside fall (n= 127), the length of stay was significantly longer, median 20 days, IQR 12–31 days than for those who did not fall at the bedside, median 9 days, IQR 5–15 days, P< 0.001.

Table 2.

Secondary outcome measures by group (unadjusted and adjusted effect sizes)

| Intervention group (n= 918) median (IQR)a |

Control group (n= 921) median (IQR)a |

Differenceb (95% CI) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barthel ADL Index | 15 (10,17) [97] | 15 (11,17) [67] | 0 (0–0) | 0.92 |

| MFES | 53 (33,78) [294] | 54.5 (35, 82) [317] | 0 (−3–0) | 0.54 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 9 (5,17) [14] | 9 (5,15) [3] | 0 (0–1) | 0.13 |

| EQ 5D mean (SD) | 0.47 (0.26) [97] | 0.46 (0.28) [65] | 0.01 (−0.02–0.03) | 0.63 |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| Number of fallers (%) | 65 (7.08) | 64 (6.95) | 1.02 (0.71–1.46) | 0.91 |

| Discharged to admission address | 521 (60.4) [56] | 529 (61.8) [65] | 0.94 (0.78–1.15) | 0.56 |

aExcept where stated [ ] missing values.

bDifference in medians for Barthel ADL Index, MFES and length of hospital stay. Difference in means for EQ 5D.

*P-value from Mann–Whitney U-test (Barthel ADL Index, MFES and length of hospital stay), χ2-test (proportion of fallers, discharge destination) and t-test (EQ 5D).

The mean cost per patient in the intervention group was £7199 compared with £6400 in the control group (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix C, Table S4). The mean difference in QALYs per patient, adjusting for baseline, was 0.0001 (95% CI: −0.0006 to 0.0004; P= 0.67).

System problems

There were a total of 120 problems with sensor system functioning recorded between January 2009 and February 2011. Forty of the records (33%) were classified as de-functioning of the equipment (sensors disconnected, batteries removed, transmitter box power cut), 51 (43%) as pager faults (combination of problems including damage or lost) and 29 (24%) instances where working pagers found unattended (lying on desks or in drawers, taken home).

Discussion

The use of bed and bedside chair pressure sensors using radio-pagers did not significantly reduce bedside falls, time to first bedside fall or prove cost effective, in elderly patients admitted to acute, general medical wards in the UK.

There are a number of limitations in our study that need to be recognised. Our study was powered to detect a 35% reduction in the rate of bedside falls, based on the sample size estimates from our pilot study [17]. It is possible that the intervention may be associated with a smaller reduction in bedside falls, which may have been missed. Secondly, we collected our primary outcome data from the mandatory incident reporting system operating within the hospital and it is recognised that under-reporting of falls may occur within such systems [24]. Another limitation was blinding of the staff to the intervention, may have led to differential reporting of falls between groups, however unless this occurred to a very large extent, it is unlikely to explain our findings of no effect.

Our findings confirm those from a previous small non-randomised study [7] and a recent large cluster randomised RCT [10], extending the generalisability of the findings from previous studies to the UK healthcare setting. This study also adds evidence that the use of radio-paging systems to alert nurses does not enhance the effectiveness of the sensor systems. The findings from RCTs of multi-factorial interventions that have included bed sensors are mixed. One study using sensors as part of a multi-factorial intervention found no effect on falls rate [13], whilst a more recent trial using sensors as part of a multi-factorial intervention significantly reduced in-patient falls, although the actual numbers of patients receiving alarms and the type of alarm were not described [14].

The findings from our study and the recent RCT evaluating sensors as a single intervention would both suggest any reductions in falls rates seen with multi-factorial interventions which include bed/chair sensors, may be attributable to elements of the intervention other than bed/chair sensors.

There are several possible explanations for why bed and bedside chair pressure sensors do not appear to reduce in-patient falls. Complex organisational factors including managing organisational change, leadership, commitment and communication may be important in implementing change within healthcare [25, 26] and these may have been underestimated in translating the findings from our single ward pilot study, to the current RCT. It is also possible that although the sensors alerted, nurses were unable to respond to radio-pagers sufficiently quickly to avert falls and this is supported by findings from a recent U.S. study [27] which suggests faster ‘nurse call light response time’ may contribute to lower fall rates. Nurses may also be able to respond more quickly to radio-pagers if alarms were restricted to a smaller number of patients. As our trial population comprised frail older people, the majority of whom were at high risk of falls, restricting the number of alarms per ward may be problematic. First, patients at the highest risk of falls would need identifying and providing with alarms. Secondly, as most participants in our trial were already at high risk of falls, alternative fall prevention strategies would need implementing for those not provided with alarms. It is also possible that alarms may prevent some falls away from the bedside, as patients may have gone beyond the bedside area by the time nurses can respond to radio-pagers.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that bed and bedside chair pressure sensors using radio-pagers did not reduce the rate of in-patient bedside falls, time to first bedside fall and are not cost effective in elderly patients in acute, general medical wards in the UK.

Key points.

In-patient falls are a significant problem in acute hospitals.

In-patient falls lead to significant injury and increased length of stay.

Bed and bedside pressure sensors using radio-paging as part of a single intervention do not reduce falls rates.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

National Institute for Health Services Research (NIHR)—Research for Patient Benefit Programme (RfPB)-PB-PG-0107-11112. Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust was the sponsor of the trial.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rosemary Clacy and Peter Cass as patient and public involvement representatives and Professor Dawn Skelton (chair), Dr Anne-Louise Schokker and Dr Jonathan Baly as members of the independent trial management group for their support and guidance.

References

- 1.Oliver D, Daly F, Finbarr MC, et al. Risk factors and risk assessment tools for falls in hospital inpatients: a systematic review. Age and Ageing. 2004;33:122–30. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliver D, Healey F, Haines TP. Preventing falls and fall-related injuries in hospitals. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:645–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Patient Safety Agency. 2010. Slips, trips and falls data update www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/patient-safety-topics/patient-accidents-falls/?Entryid45=74567. (23 June 2010, date last accessed)

- 4.Vetter N, Ford D. Anxiety and depression scores in elderly fallers. Int J Geriatr Pscyh. 1989;4:168–73. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates D, Pruess K, Souney P, et al. Serious falls in hospitalised patients; correlates and resource utilisation. Am J Med. 1995;99:137–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liddle J, Gilleard C. The emotional consequences of falls for patients and their families. Age Ageing. 1994;23:17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tideiksaar R, Feiner C, Maby J. Falls prevention: the efficacy of a bed alarm system in an acute care setting. Mount Sinai J Med. 1993;60:522–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haines TP, Bell RAR, Varghese PN. Pragmatic cluster randomised trial of a policy to introduce low-low beds to hospital wards for the prevention of fall sand fall injuries. JAGS. 2010;58:435–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines TP, Hill AM, Hill KD, et al. Patient education to prevent falls among older hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:516e24. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shorr RI, Chandler MA, Mion LC, et al. Effects of an intervention to increase bed alarm use to prevent falls in hospitalised patients. Ann Int Med. 2012;157:692–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-10-201211200-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh SL, Hafizah N, Lee JY, et al. Impact of fall prevention programme in acute hospital settings in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stenvall M, Olofsson B, Lundström M, et al. A multidisciplinary, multifactorial intervention program reduces postoperative falls and injuries after femoral neck fracture. Osteoporosis Int. 2007;18:167–75. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cumming RG, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Prevention of Older People's Injury Falls Prevention in Hospitals Research Group. Cluster randomised trial of a targeted multifactorial intervention to prevent falls among older people in hospital. BMJ. 2008;336:758–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39499.546030.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley A, et al. Fall prevention in acute care hospitals. JAMA. 2010;304:1912–18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron ID, Murray GR, Gillespie LD, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in nursing care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD005465. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC. Rethinking individual and community fall prevention strategies: a meta-regression comparing single and multifactorial interventions. Age Ageing. 2007;36:656–62. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahota O. Vitamin D and in-patient falls. Age Ageing. 2009;38:339–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly KE, Phillips CL, Cain KC, et al. Evaluation of a non intrusive monitor to reduce falls in nursing home patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2002;3:377–82. doi: 10.1097/01.JAM.0000036702.12824.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.JCAHO (Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) 2000 Sentinel event alert issue 14: Fatal falls: Lessons for the future http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_14.htm. (12 July 2000, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vass CD, Sahota O, Drummond A, et al. REFINE (REducing Falls in In-patieNt Elderly) – a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2009;10:83–6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, et al. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:61–3. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill KD, Schwarz JA, Kalogeropoulos AJ, et al. Fear of falling revisited. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1025–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EuroQol Group: EuroQol – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shorr RI, Mion LC, Chandler AM, et al. Improving the capture of falls events in hospitals: combining a service for evaluating inpatient falls with an incident report system. J Am Geriat Soc. 2008;56:701–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01605.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Southon G, Sauer C, Dampney K. Lessons from a failed information systems initiative: issues for complex organisations. Int J Med Inform. 1999;55:33–46. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(99)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boland R, Hirschheim RA. Office Automation: A Social and Organizational Perspective. Wiley, Chichester: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzeng H-M, Titler MG, Ronis DL, Yin C-Y. The contribution of staff call light response time to fall and injurious fall rates: an exploratory study in four US hospitals using archived hospital data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:84. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-84. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472–6963/12/84. (31 March 2012, date last accessed) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.