Abstract

Objectives

Intercountry comparability between studies on medication use in pregnancy is difficult due to dissimilarities in study design and methodology. This study aimed to examine patterns and factors associated with medications use in pregnancy from a multinational perspective, with emphasis on type of medication utilised and indication for use.

Design

Cross-sectional, web-based study performed within the period from 1 October 2011 to 29 February 2012. Uniform collection of drug utilisation data was performed via an anonymous online questionnaire.

Setting

Multinational study in Europe (Western, Northern and Eastern), North and South America and Australia.

Participants

Pregnant women and new mothers with children less than 1 year of age.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Prevalence of and factors associated with medication use for acute/short-term illnesses, chronic/long-term disorders and over-the-counter (OTC) medication use.

Results

The study population included 9459 women, of which 81.2% reported use of at least one medication (prescribed or OTC) during pregnancy. Overall, OTC medication use occurred in 66.9% of the pregnancies, whereas 68.4% and 17% of women reported use of at least one medication for treatment of acute/short-term illnesses and chronic/long-term disorders, respectively. The extent of self-reported medicated illnesses and types of medication used by indication varied across regions, especially in relation to urinary tract infections, depression or OTC nasal sprays. Women with higher age or lower educational level, housewives or women with an unplanned pregnancy were those most often reporting use of medication for chronic/long-term disorders. Immigrant women in Western (adjusted OR (aOR): 0.55, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.87) and Northern Europe (aOR: 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.83) were less likely to report use of medication for chronic/long-term disorders during pregnancy than non-immigrants.

Conclusions

In this study, the majority of women in Europe, North America, South America and Australia used at least one medication during pregnancy. There was a substantial inter-region variability in the types of medication used.

Keywords: Maternal medicine < OBSTETRICS, Therapeutics, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Uniform data collection of drug utilisation data across all participating countries allows for intercountry comparability of the prevalence of medication use during pregnancy, up to now impeded by differences in study design and methodology.

The study adds a multinational perspective on over-the-counter medication use during pregnancy to the limited number of studies quantifying the extent of self-medication during pregnancy.

Lack of validity of the self-reported diagnoses is a limitation since all disorders and related medication use were self-reported by the study participants.

A web-based survey as a study method impedes calculation of a conventional response rate and may cause selection bias of the target population.

Introduction

Ethical reasons preclude inclusion of pregnant women in the vast majority of premarketing clinical trials.1 As a consequence, most medications are placed onto the market without a directly established safety profile in human pregnancy.2 So far, few medications have been shown to be major teratogens, yet the risk of minor teratogenicity or of more subtle effects on fetal development still have to be determined for most of them.3 Despite this, medication use during pregnancy is common. Mitchell et al4 found that use of medications, either prescribed or purchased over the counter (OTC), occurred in 88.8% of all pregnancies in the USA. In Europe, prevalence estimates of prescribed medication use vary considerably across countries, ranging from 26% in Serbia to 93% in France.5–10 Such intercountry variability could, at least in part, be caused by differences in study design, methodology and exposure ascertainment across studies.11 Uniform collection of drug utilisation data during pregnancy between countries may overcome such drawbacks, allowing for intercountry comparability of prevalence estimates and shedding light on differences in prenatal care in the various countries.

Prior studies have addressed research priorities in this area such as presenting results on an individual drug level according to the indication of use, quantifying the extent of OTC and prescribed medication use during pregnancy, and taking into account intercountry comparability.4 Only a few studies have individually examined maternal factors associated with specific types of medication use during pregnancy.11–14

The objectives of the current study were to examine patterns of medication use in pregnancy from a multinational perspective, with special emphasis on type of medication utilised, including OTC medications and self-reported indications for use, and to identify maternal background factors potentially associated with medication use for acute/short-term illnesses, medication use for chronic/long-term disorders and OTC medication use during pregnancy.

Methods

Study design and data collection

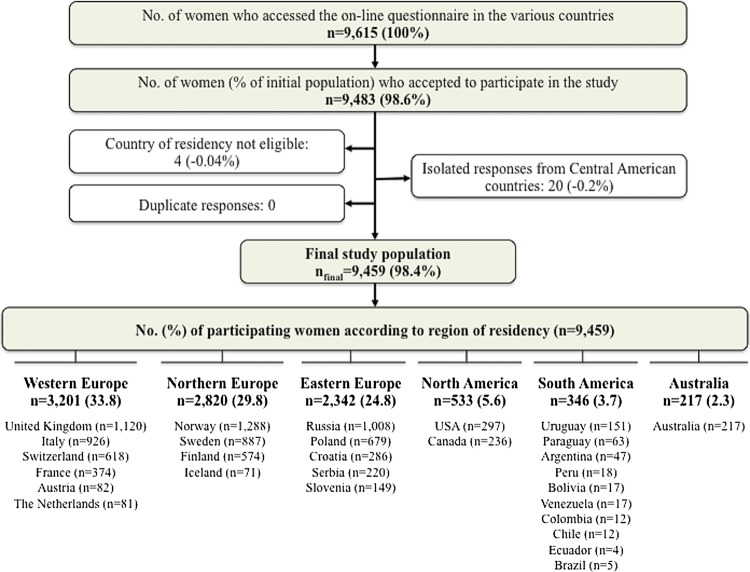

This is a multinational, cross-sectional, web-based study. Pregnant women at any gestational week and mothers with children less than 1 year of age were eligible to participate. Member countries of the European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS), the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) in North America, MotherSafe in Australia and European institutions conducting public health research were invited to take part in the project. Of these, 18 countries participated (Australia, Austria, Canada, Croatia, Finland, France, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the USA). Data originating from some South and Central American countries were also collected through OTIS. Owing to the low number of participants on the individual country level, the region of Central America was excluded and countries in South America were aggregated into one region. Data selection to achieve the final study sample was performed as depicted in figure 1. Participants were categorised according to the reported country of residency and grouped into six regions: Western Europe, Northern Europe, Eastern Europe, North America, South America and Australia.

Figure 1.

The participant flowchart to achieve the final sample analysed.

Data were collected through an anonymous online questionnaire administered by Quest Back (http://www.questback.com) and accessible for a period of 2 months in each participating country within the period 1 October 2011 to 29 February 2012. The questionnaire was open to the public via utilisation of banners (invitations to participate in the study) on national websites and/or social networks commonly visited and consulted by pregnant women and/or new mothers. The complete questionnaire is presented in online supplementary appendix 1. Detailed information about recruitment tools utilised and Internet penetration rates are summarised in online supplementary appendix 2.

The questionnaire was first developed in Norwegian and English and then translated into the other relevant languages. A pilot study was carried out in September 2011 (n=47) which elicited no major change to the questionnaire. Collected data were scrutinised for the presence of potential duplicates (based on reported country of residency, sociodemographic characteristics, date and exact time of questionnaire completion) but none were identified.

Exposure variables

Maternal sociodemographics (ie, region of residency, age, educational level, mother tongue, working status at time of conception, previous children, marital status and unplanned pregnancy) and lifestyle characteristics (ie, smoking status before and during pregnancy and alcohol consumption after awareness of pregnancy) constituted the exposure variables. To assess external validity, we compared sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics of our study population on an individual country level with those of the general birthing population in the same country. Reports of National Statistics Bureaus or previous national studies were utilised for this purpose. The ratio between the number of respondents and the estimated number of live births in the 2-month period was also examined for each country (see online supplementary appendix 3).

Outcome variables

Use of any medication, medication for acute/short-term illnesses, medication for chronic/long-term disorders and OTC medication use during pregnancy constituted the outcome variables. Participants were first confronted with a list of the most common acute/short-term illnesses (ie, nausea, heartburn, constipation, common cold, urinary tract infections (UTIs), other infections, pain in the neck/back/pelvic girdle, headache and sleeping problems) and the most prevalent chronic/long-term disorders (ie, asthma, allergy, hypothyroidism, rheumatic disorders, diabetes, epilepsy, depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease and other disorders) and asked whether they suffered/had suffered from these conditions during pregnancy. In case of an affirmative response, women were questioned about medication use for each individual indication as a free-text entry. Use of OTC medications was also recorded. Recall was aided with a list of five OTC medication categories: painkillers, nasal spray/drops, antinauseants, antacids and laxatives, along with examples of brand name products of relevance in each country. It was optional to report timing of exposure for each of the medication use questions (the alternatives were gestational weeks 0–12 (1st trimester), 13–24 (2nd trimester) and 25 to delivery (3rd trimester)).

We defined a medicine as a single product containing one or more active ingredients. We initially identified the main active ingredient(s) and formulation of the reported medicinal products either in the relevant national medicines database or in the ‘Martindale’ textbook.15 All recorded medications were coded into the corresponding Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes at the ATC 5th level (ie, the substance level) whenever possible, otherwise into the 2nd–4th levels as appropriate, in accordance with the WHO ATC index.16 The OTC status of medications was crosschecked with the prescription policies within each country. Whenever a prescription medication was reported under the OTC question, this record was omitted from the analysis of OTC use but counted in the estimation of total medication use (including prescription and OTC). Iron, mineral supplements, vitamins, herbal remedies and any type of complementary medicine were recorded separately and excluded from the estimation of medication use.

The required sample size calculation for the outcome variables on region and individual country levels is outlined in online supplementary appendix 4. The expected prevalence estimates were set according to the results of previous studies.5–10 17 18

Ethics

All participants gave informed consent by answering ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Are you willing to participate in the study?’. All data were handled and stored anonymously.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilised as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to examine the association between maternal characteristic and three categorical outcome measures (yes/no): medication use for acute/short-term illnesses; medication use for chronic/long-term disorders; OTC medication use. p Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data are presented as adjusted ORs (aOR) with 95% CI. The analysed explanatory variables included all maternal sociodemographics and lifestyle characteristics. After fitting the univariate logistic regression model for all explanatory variables, the multivariate model was built and adjusted for all remaining covariates. The Hosmer and Lemeshow19 test was used to assess goodness of fit of the final multivariate model. Analogue subanalyses on individual region level were performed. In these instances, region of residency was not included in the model. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.20.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics).

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 9615 women accessed the online questionnaire, of which 98.6% completed it. The participant flowchart to achieve final study population (n=9459) is depicted in figure 1. A total of 5089 women (53.8%) were pregnant at the time of completion of the questionnaire, whereas 4370 women (46.2%) had delivered their babies within the previous year. Of the former group, 1095 (21.5%), 1702 (33.4%) and 2291 (45%) women were in the first, second and third trimester of pregnancy, respectively. Of the latter group, 1320 (30.2%), 947 (21.7%) and 2102 (48.1%) had a baby of age ≤16 weeks, 17–28 weeks and ≥29 weeks, respectively. For two women, the time of gestation/baby’s age was unknown. Overall, the birthing population in each participating country was reflected quite well by the sample with respect to age, parity and smoking habits (see online supplementary appendix 3). However, there was a difference in terms of educational level; on average, the women in the study had higher education than the general birthing population in each country. In addition, participants in Sweden, Austria, Iceland and Italy were slightly more often primiparous, whereas the responders in Australia, the USA, the Netherlands, Slovenia and Croatia were somewhat older than the general birthing population.

Total medication use

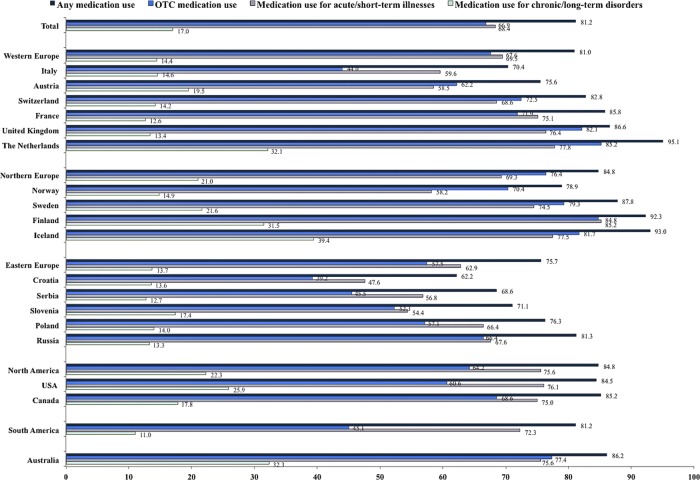

After exclusion of vitamins, mineral supplements and iron, use of at least one medication either prescribed or OTC at any time during pregnancy was reported by 7678 of 9459 women (81.2%). Figure 2 depicts prevalence estimates of total medication use during pregnancy by region and country of residence. The extent of OTC medication use, as well as medication use for acute/short-term illnesses and chronic/long-term disorders, is also outlined. The highest prevalence of total medication use during pregnancy was observed in the Netherlands (95.1%), Iceland (93%) and Finland (92.3%). The overall prevalence estimates of medication use in pregnancy according to timing and drug class (ATC levels 1 and 2) are presented in online supplementary appendix 5. Medications for the nervous system (ATC class N) were most commonly used during pregnancy (57.5%), mostly due to paracetamol (acetaminophen) and its combinations.

Figure 2.

The proportion of respondents (%) reporting use of any medication, over-the-counter (OTC) medication, medication for acute/short-term illnesses and medication for chronic/long-term disorders during pregnancy, according to region and country of residency. The observed estimates do not include vitamins, mineral supplements, iron and herbal or complementary medicine products.

A corollary analysis according to pregnancy status showed that pregnant women reported in a significantly lower degree than new mothers any medication use during pregnancy (78.8% vs 84%, p<0.001), as well as OTC medication use (63% vs 71.5%, p<0.001) and medication use for acute/short-term illnesses (66.2% vs 70.9%, p<0.001). In contrast, the difference in medication use for chronic/long-term disorders was not significant (17.4% vs 16.5%, p=0.271). None of the rates differed significantly when women in the third trimester of pregnancy were compared with new mothers.

Medication use according to indication

Headache, heartburn, pain, nausea and UTIs constituted the leading indications for use of medication during pregnancy among the acute/short-term illnesses analysed. Hypothyroidism, asthma, allergy and depression were the leading indications for chronic/long-term medication use. Observed prevalence rates of these disorders, overall and by region of residency, are presented in online supplementary appendices 6 and 7, respectively, along with rates of total and specific medication use. Table 1 outlines prevalence estimates of OTC medication use during pregnancy by region and indication for use. Only the most common medication groups reported are presented. Inter-region variations in rates and types of medication used during pregnancy were observed for acute/short-term illnesses (eg, nausea and UTIs), chronic/long-term disorders (eg, asthma and depression) and OTC medications (eg, nasal spray).

Table 1.

Use of OTC medication at any time during pregnancy by ATC level, indication for use and region (n=9459)*†

| OTC medication use, overall and by drug groups | REGION |

Total n=9459 n (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Europe n=3201 n (%) |

Northern Europe n=2820 n (%) |

Eastern Europe n=2342 n (%) |

North America n=533 n (%) |

South America n=346 n (%) |

Australia n=217 n (%) |

||

| OTC painkillers, total | 1714 (53.5) | 1773 (62.9) | 734 (31.3) | 284 (53.3) | 127 (36.7) | 151 (69.9) | 4783 (50.6) |

| By drug group | |||||||

| Paracetamol (including combinations) (N02BE) | 1655 (51.7) | 1735 (61.5) | 630 (26.9) | 263 (49.3) | 87 (25.1) | 146 (67.3) | 4516 (47.7) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (M01A) | 70 (2.2) | 182 (6.5) | 68 (2.9) | 40 (7.5) | 59 (17.1) | 7 (3.2) | 426 (4.5) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (including combinations) (N02BA) | 7 (0.2) | 11 (0.4) | 32 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 55 (0.6) |

| Metamizole (N02BB02) | – | 6 (0.2) | 31 (1.3) | 1 (0.2) | 12 (3.5) | – | 50 (0.5) |

| OTC antacids, total | 1011 (31.6) | 883 (31.3) | 583 (24.9) | 129 (24.2) | 48 (13.9) | 76 (35.0) | 2730 (28.9) |

| By drug group | |||||||

| Antacids (aluminium, salts combinations, antiflatulents) | 472 (14.7) | 550 (19.5) | 508 (21.7) | 47 (8.8) | 36 (10.4) | 54 (24.9) | 1667 (17.6) |

| Alginic acid complex/sucralfate/bismuth (A02BX) | 606 (18.9) | 421 (14.9) | 87 (3.7) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 17 (7.8) | 1136 (12.0) |

| H2 receptor antagonists (A02BA) | 20 (0.6) | 20 (0.7) | 16 (0.7) | 57 (10.1) | 10 (2.9) | 17 (7.8) | 137 (1.4) |

| Antacids with calcium (A02AC) | 23 (0.7) | 12 (0.4) | 10 (0.4) | 69 (12.9) | 2 (0.6) | 10 (4.6) | 126 (1.3) |

| Proton pump inhibitors (A02BC) | 38 (1.2) | 52 (1.8) | – | 10 (1.9) | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.3) | 107 (1.1) |

| OTC nasal sprays/drops, total | 272 (8.5) | 742 (26.3) | 451 (19.3) | 35 (6.6) | 7 (2.0) | 14 (6.5) | 1521 (16.1) |

| By drug group | |||||||

| Sympathomimetic nasal decongestants (R01AA/R01BB) | 204 (6.4) | 683 (24.2) | 365 (15.6) | 20 (3.8) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.8) | 1279 (13.5) |

| Nasal corticosteroids (R01AD) | 31 (1.0) | 49 (1.7) | 12 (0.5) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 10 (4.6) | 109 (1.2) |

| Nasal immunostimulants (low-dose interferon) (L03A) | – | – | 28 (1.2) | – | – | – | 28 (0.3) |

| OTC laxatives, total | 240 (7.5) | 227 (8.0) | 237 (10.1) | 50 (9.4) | 8 (2.3) | 19 (8.8) | 781 (8.3) |

| By drug group | |||||||

| Osmotically acting laxatives (A06AD) | 159 (5.0) | 171 (6.1) | 197 (8.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (3.7) | 539 (5.7) |

| Contact laxatives (A06AB) | 28 (0.9) | 44 (1.6) | 18 (0.8) | 7 (1.3) | 6 (1.7) | 2 (0.9) | 105 (1.1) |

| Enemas (A06AG) | 3 (0.1) | 25 (0.9) | 34 (1.5) | 4 (0.8) | – | 2 (0.9) | 68 (0.7) |

| Softeners, emollients (A06AA) | 8 (0.2) | – | – | 38 (7.1) | – | 6 (2.8) | 52 (0.5) |

| OTC antinauseants, total | 263 (8.2) | 273 (9.7) | 41 (1.8) | 60 (11.3) | 28 (8.1) | 40 (18.4) | 705 (7.5) |

| By drug group | |||||||

| First generation antihistamines (R06A) | 141 (4.4) | 256 (9.1) | 7 (1.5) | 55 (10.3) | 5 (1.4) | 5 (2.3) | 469 (5.0) |

| Metoclopramide/domperidone/bromopride (A03FA) | 113 (3.5) | 5 (0.2) | 18 (0.8) | 2 (0.4) | 19 (5.5) | 27 (12.4) | 184 (1.9) |

| Total OTC medication use | 2163 (67.6) | 2155 (76.4) | 1347 (57.5) | 342 (64.2) | 156 (45.1) | 168 (77.4) | 6331 (66.9) |

*Countries are grouped into regions as shown in figure 1.

†Sums of percentages do not add up to total medication use as only most common medication groups are presented. Rates do not include mineral supplements, vitamins, iron and herbal or complementary medicine products.

Total use estimates of the main OTC categories are presented in italics.

ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical; OTC, over-the-counter medications.

Factors associated with medication use

Factors associated with medication use during pregnancy according to type of medication utilised are presented in table 2. Use of chronic/long-term medications during pregnancy was reported in a significantly larger extent by women in Northern Europe (aOR: 1.68, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.94), North America (aOR: 1.80, 95% CI 1.42 to 2.28) and Australia (aOR: 2.76, 95% CI 2.03 to 3.76) compared with women in Western Europe. Older women or housewives, those with low education or with an unplanned pregnancy, were the ones most often reporting use of chronic/long-term medication. Subanalysis on individual region level revealed that women not having the official language of the country of residency as mother tongue were less likely to report chronic/long-term medication use in Western (aOR: 0.55, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.87) and Northern Europe (aOR: 0.50, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.83), but not in the other regions.

Table 2.

Factors associated with medication use in pregnancy (n=9459)*

| Medication use |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For acute/short-term illnesses (n=6469) |

For chronic/long-term disorders (n=1604) |

OTC (n=6331) |

||||

| n (%) | aOR (95% CI) | n (%) | aOR (95% CI) | n (%) | aOR (95% CI) | |

| Region of residency† | ||||||

| Western Europe | 2224 (69.5) | Reference | 462 (14.4) | Reference | 2163 (67.6) | Reference |

| Northern Europe | 1954 (69.3) | 0.96 (0.86 to 1.08) | 593 (21.0) | 1.68 (1.46 to 1.94) | 2155 (76.4) | 1.54 (1.36 to 1.74) |

| Eastern Europe | 1474 (62.9) | 0.69 (0.61 to 0.78) | 322 (13.7) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.21) | 1347 (57.5) | 0.60 (0.53 to 0.67) |

| North America | 403 (75.6) | 1.28 (1.03 to 1.60) | 119 (22.3) | 1.80 (1.42 to 2.28) | 342 (64.2) | 0.81 (0.66 to 0.99) |

| South America | 250 (82.3) | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) | 38 (11.0) | 0.70 (0.48 to 1.01) | 156 (45.1) | 0.34 (0.27 to 0.44) |

| Australia | 164 (75.6) | 1.29 (0.93 to 1.79) | 70 (32.3) | 2.76 (2.03 to 3.76) | 168 (77.4) | 1.57 (1.12 to 2.20) |

| Maternal age (years) | ||||||

| ≤20 | 232 (70.5) | 1.22 (0.93 to 1.60) | 761 (14.7) | 0.58 (0.39 to 0.87) | 205 (62.3) | 1.05 (0.81 to 1.36) |

| 21–30 | 3531 (68.2) | Reference | 33 (10.0) | Reference | 3461 (66.8) | Reference |

| 31–40 | 2576 (68.6) | 0.90 (0.82 to 1.00) | 764 (20.4) | 1.44 (1.27 to 1.63) | 2531 (67.4) | 0.85 (0.77 to 0.94) |

| ≥41 | 130 (66.3) | 0.73 (0.54 to 1.00) | 46 (23.5) | 1.61 (1.13 to 2.29) | 134 (68.4) | 0.86 (0.62 to 1.19) |

| Previous children | ||||||

| No | 3082 (65.5) | Reference | 735 (15.6) | Reference | 2949 (62.6) | Reference |

| Yes | 3387 (71.3) | 1.34 (1.22 to 1.47) | 869 (18.3) | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.21) | 3382 (71.2) | 1.58 (1.44 to 1.74) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 6066 (68.5) | Reference | 1503 (17.0) | Reference | 5960 (67.3) | Reference |

| Single/divorced/others | 403 (66.3) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.10) | 101 (16.6) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.35) | 371 (61.0) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.10) |

| Working status | ||||||

| Employed, but not as HCP | 3737 (66.8) | Reference | 905 (16.2) | Reference | 3667 (65.6) | Reference |

| HCP | 934 (74.4) | 1.41 (1.23 to 1.63) | 240 (19.1) | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.33) | 944 (75.2) | 1.42 (1.23 to 1.64) |

| Student | 592 (69.1) | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 128 (14.9) | 1.04 (0.84 to 1.30) | 578 (67.4) | 1.10 (0.93 to 1.30) |

| Housewife | 608 (72.6) | 1.14 (0.96 to 1.35) | 170 (20.3) | 1.34 (1.10 to 1.63) | 577 (68.9) | 1.05 (0.88 to 1.24) |

| Job seeker | 281 (66.0) | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.20) | 66 (15.5) | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.36) | 258 (60.6) | 0.85 (0.68 to 1.05) |

| Other than above | 311 (65.2) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.12) | 94 (19.7) | 1.29 (1.01 to 1.65) | 302 (63.3) | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Less than high school | 331 (72.7) | 1.17 (0.93 to 1.49) | 92 (20.2) | 1.51 (1.15 to 1.97) | 317 (69.7) | 1.32 (1.04 to 1.67) |

| High school | 1864 (68.7) | Reference | 428 (15.8) | Reference | 1779 (65.6) | Reference |

| More than high school | 3574 (68.4) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.11) | 916 (17.5) | 1.04 (0.91 to 1.20) | 3489 (66.8) | 1.07 (0.96 to 1.19) |

| Others, unspecified | 700 (65.7) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.96) | 168 (15.8) | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.16) | 746 (70.0) | 1.13 (0.97 to 1.33) |

| Alcohol use after awareness of pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 5270 (67.1) | Reference | 1322 (16.8) | Reference | 5133 (65.3) | Reference |

| Yes | 1144 (75.7) | 1.59 (1.39 to 1.81) | 270 (17.9) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.29) | 1150 (76.1) | 1.95 (1.71 to 2.23) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 5835 (68.5) | Reference | 1441 (16.9) | Reference | 5716 (67.0) | Reference |

| Yes, but less than before pregnancy | 530 (69.0) | 1.08 (0.91 to 1.27) | 130 (16.9) | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.25) | 511 (66.5) | 1.06 (0.90 to 1.26) |

| Yes, the same or more than before pregnancy | 88 (67.7) | 0.95 (0.64 to 1.40) | 28 (21.5) | 1.19 (0.74 to 1.90) | 89 (68.5) | 1.21 (0.81 to 1.82) |

| Planned pregnancy | ||||||

| Yes | 5836 (68.4) | Reference | 1427 (16.7) | Reference | 5727 (67.2) | Reference |

| No | 616 (68.4) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.12) | 173 (19.2) | 1.29 (1.06 to 1.56) | 587 (65.1) | 1.00 (0.85 to 1.17) |

| First language different from the official main language in the country of residency | ||||||

| No | 6089 (68.5) | Reference | 1530 (17.2) | Reference | 5972 (67.1) | Reference |

| Yes | 363 (67.2) | 0.93 (0.76 to 1.12) | 71 (13.1) | 0.66 (0.50 to 0.86) | 347 (64.3) | 0.89 (0.74 to 1.08) |

*Numbers may not add up due to missing values. Missing values are less than 5% of the total. Mineral supplements, vitamins, iron, herbal or complementary medicine products are not included in the medication use estimates.

†Countries are grouped into regions as shown in figure 1.

Statistically significant results (ie, p values <0.05) are presented in italics.

aOR, adjusted OR; HCP, healthcare provider; OTC, over-the-counter medications.

Discussion

This is the first web-based study examining patterns and factors associated with medication use during pregnancy on a multinational level. In all regions, approximately 8 of 10 women reported use of at least one medication, either prescribed or OTC, during the course of their pregnancy. This finding is in line with previous research conducted in Europe, North America, South America and Australia,4 20–25 though our estimates were somewhat higher in some of the Eastern European countries, for example, Serbia, than those observed in a previous study.5 Different recruitment strategies, that is, web based in our study versus maternity care unit/community pharmacy based in the previous study could explain such discrepancy.

Overall, analgesics, antacids, nasal decongestants/antiallergics and systemic antibiotics were the medication groups dominating the drug utilisation scenario, as also shown by previous research.4 20–22 However, our study also provides insights into the proportion of medicated women among those suffering from a specific illness during pregnancy across the six regions. We found that approximately 7 of 10 women who reported UTIs were treated with antibiotics during pregnancy. This related to all regions, except Eastern Europe where it was only 4 of 10 women. Since women may perceive dysuria without ascertainment of bacteriuria in the urine as UTI, an over-reporting of the illness could have occurred. Yet, a suboptimal treatment of UTIs during pregnancy in Eastern Europe cannot be ruled out. The intercountry variability in the types of antibiotics used for UTIs could simply be explained by differences in prescribing practice,26 presence of screening for bacteriuria in early pregnancy or specific antibiotic resistance patterns.

Even though nausea was the condition affecting most women in all six regions, the corresponding proportions of medicated nausea were generally low. This scenario is probably due to two main factors: (1) the predominantly mild character of nausea and the possibility of non-pharmacological management (eg, dietary advices) and (2) the reluctance of general practitioners to prescribe antinauseants even though safety profile assessments are in place.27 28 As also shown in previous studies,4 29 use of serotonin antagonists during pregnancy in North America and Australia is increasing compared with the other regions, eliciting the need of sound studies assessing the safety profile of this drug group in pregnancy.

In most regions, the self-reported prevalence of hypothyroidism was somewhat higher than the reported hormone substitution rate. Owing to its known association with adverse pregnancy outcomes,30 the unexpected finding of potential suboptimal treatment of hypothyroidism during pregnancy deserves attention. It could probably be due to lack of information about hypothyroidism typology and its diagnostic ascertainment in our study.

In our study, depression was self-reported and not based on any psychometric assessment, thus the observed substantial inter-regional variability in the extent of this disorder and related medication use could have certainly been affected by women's attitudes in reporting. Our estimate of medication use for depression in Australia was higher than that observed in a recent study (10.6% vs 2.1%).31 However, the similarity in self-reported depression itself (11.5% vs 15.6%) suggests that our population might mostly comprise women who did not discontinue their pharmacological therapy once they became pregnant. Our estimates for North America and Western Europe were in line with recent literature showing an increase in antidepressant use in pregnancy during the past years.4 32 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most widely used antidepressant class. Recent meta-analyses have shown that antidepressants, including SSRIs, do increase the risk of poor neonatal adaptation syndrome, specific cardiovascular malformations and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.33–35 However, the clinical impact of the latter two outcomes, in absolute terms, is small and the risk of pharmacotherapy should always be weighted versus the risk of undertreated depression in pregnancy.

In most regions, approximately 60–70% of women reported use of at least one OTC medication during the course of their pregnancies, mostly for pain conditions, heartburn and upper airways disorders, indicating a substantially high rate of self-medication during pregnancy. This estimate aligns with previous research carried out in North America.17 Of note, self-medication with OTC sympathomimetic nasal decongestants was more extensive in Northern and Eastern Europe than in the remaining regions; this could be explained by the time of the year when the data collection was performed.

Region of residency was an important factor associated with medication use during pregnancy. As also shown by Cleary et al,36 we found that rates of medication use among women originally from Eastern Europe and South America were significantly lower than those observed in Western Europe, North America and Australia. Such geographical differences could be due to culture, variations in prenatal care assistance or access to medications in the various regions and the related costs.

Women working as healthcare providers, consuming alcohol during pregnancy or those already having children were more likely to use short-term and OTC medications, possibly reflecting higher confidence in self-treatment and use of medications in general in the former instance, and less anxiety for the pregnancy outcome in the latter two instances.

Contrary to previous studies indicating an association between higher maternal education and more prevalent use of medication during pregnancy,14 17 23 we found that lower education was associated with a higher use of OTC medications as well as medication for chronic/long-term disorders (30–50% increased risk). Results of similar magnitude (30% increased risk) were also observed by Olesen et al,37 whereas Stokholm et al38 identified a stronger association (2.3-fold increased risk) between low maternal education and use of antibiotic for respiratory tract infections during pregnancy. One factor negatively associated with chronic/long-term medication use was not having the official language of the country of residency as mother tongue. This tendency was detected in Western and Northern Europe, raising concerns about the potential health risks for immigrant women in these two regions. As shown by Hämeen-Anttila et al,39 57% of pregnant women have perceived information needs about medications during pregnancy. Thus, identification of potential users or non-users of medication during pregnancy might be of clinical relevance. Indeed, this may allow tailored evidence-based information about medication safety or outcome of suboptimal medication of severe medical conditions in pregnancy.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength is that data collection was performed uniformly across all participating countries, allowing for intercountry comparison of the prevalence of medication use during pregnancy. By quantifying the extent of self-medication with OTC drugs and medication use according to self-reported indication, it was possible to determine the leading causes for medication use among pregnant women. Categorisation of maternal characteristics positively associated with the various types of medications used during pregnancy enabled us to identify which groups of women are more likely to need information about medication use during pregnancy. The utilisation of an anonymous web-based questionnaire enabled us to reach a large proportion of the birthing population in several countries worldwide. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the women who decided to participate in the study differed from the general birthing population in other ways that our analysis could not control for. In most of the participating countries, the study sample was large enough to warrant calculation of prevalence estimates with a precision of 5%. However, less precise estimates were permitted by the study sample in Austria, Iceland and the Netherlands (precision of 9–11%), as well as in Australia, Canada, Croatia, Serbia, Slovenia and the USA (precision of 6–7%).

One main limitation of the study is the lack of validity of the self-reported diagnoses. All disorders were self-reported by the participants, and hence dependent on the women's perception of the medical condition. Similarly, information about medication use during pregnancy was dependent on the accuracy of the women's reporting and recall. For new mothers, data were registered retrospectively; hence a risk of recall bias cannot be ruled out. In specific countries (Australia, Canada, France, Russia, the Netherlands and the USA), the study sample was a small proportion of the general birthing population; hence the generalisability of our findings for these specific countries should be interpreted with caution.

The questionnaire was only available through Internet websites; by using this kind of approach, a conventional response rate cannot be calculated and a selection bias of the target population cannot be ruled out. However, recent epidemiological studies indicate reasonable validity of web-based recruitment methods.40 41 Also, the penetration rate of the Internet either in households or at work is relatively high among women in childbearing age.42–46 Hence, the degree to which our findings can be extrapolated to the target population is based on the representativeness of the respondents to the general birthing populations in each country. The sample in each country had a somewhat higher educational level than the general birthing populations. Such a limitation might have led to an underestimation of the prevalence of medication during pregnancy. Since many ailments requiring pharmacotherapy occur in mid or late pregnancy, inclusion of women in the first trimester of pregnancy in the total data material has somewhat inflated the prevalence of non-users of medications during pregnancy. Also, women with specific disorders or in need of information about medication use during pregnancy might have been more likely to consult Internet websites, and therefore participate in this study.

Conclusions

Use of medications for acute/short-term illnesses and chronic/long-term disorders, as well as use of OTC medications, was common during pregnancy. The extent of medicated illnesses and types of medications used for the different indications varied across the six regions. This was especially relevant not only for acute/short-term illnesses such as nausea and UTIs, but also for chronic/long-term disorders such as hypothyroidism or depression. Women with higher age or lower educational level, housewives or women with an unplanned pregnancy were those most often reporting chronic/long-term medication use, as opposed to immigrants residing in Western and Northern Europe who reported the least use of this medication category. Future research should definitely focus on this specific group of women and also address more insights into the outcome of suboptimal medication for severe conditions in pregnancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Organisation of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS) and the European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS) Scientific Board who reviewed the study protocol and all website providers who contributed to the recruitment phase. They are grateful to all the participating women who took part in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AL, OS and HN conceived the idea for the study and participated in its design and coordination. AL drafted the manuscript and analysed the data. MJT, KZ, ACM, MEM, MD, AP, KH-A, AR, RGJ, MO, DK, GR, HJ, AP and IB contributed to data collection. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Norwegian Research Council grant number 216771/F11 and by the Foundation for Promotion of Norwegian Pharmacies and the Norwegian Pharmaceutical Society.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee, Region South-East in Norway. Ethical approval or study notification to the relevant national Ethics Boards was achieved in specific countries as required by national legislation.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available. Researchers can apply for data access for subprojects within the overall aims of the main study ‘The Multinational Medication Use in Pregnancy Study’.

References

- 1.Committee on Ethics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG Committee Opinion No. 377: research involving women. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:731–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam MP, Polifka JE, Friedman JM. Evolving knowledge of the teratogenicity of medications in human pregnancy. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2011;157:175–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. [S.l]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:51 e1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odalovic M, Vezmar Kovacevic S, Ilic K, et al. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Serbia. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:719–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gagne JJ, Maio V, Berghella V, et al. Prescription drug use during pregnancy: a population-based study in Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:1125–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engeland A, Bramness JG, Daltveit AK, et al. Prescription drug use among fathers and mothers before and during pregnancy. A population-based cohort study of 106,000 pregnancies in Norway 2004–2006. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:653–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakker MK, Jentink J, Vroom F, et al. Drug prescription patterns before, during and after pregnancy for chronic, occasional and pregnancy-related drugs in the Netherlands. BJOG 2006;113:559–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacroix I, Hurault C, Sarramon MF, et al. Prescription of drugs during pregnancy: a study using EFEMERIS, the new French database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:839–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malm H, Martikainen J, Klaukka T, et al. Prescription drugs during pregnancy and lactation—a Finnish register-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2003;59:127–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daw JR, Hanley GE, Greyson DL, et al. Prescription drug use during pregnancy in developed countries: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:895–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin JD, Ferencz C, Loffredo C. Use of prescription and non-prescription drugs in pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:581–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna L, McIntyre M. What over-the-counter preparations are pregnant women taking? A literature review. J Adv Nurs 2006;56:636–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odalovic M, Vezmar Kovacevic S, Nordeng H, et al. Predictors of the use of medications before and during pregnancy. Int J Clin Pharm 2013;35:408–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martindale W, Sweetman SC. Martindale: the complete drug reference. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Collaborating Centre for Drugs Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. Oslo, 2012. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ (accessed 17 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Refuerzo JS, Blackwell SC, Sokol RJ, et al. Use of over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies in pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2005;22:321– 4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawicki E, Stewart K, Wong S, et al. Medication use for chronic health conditions by pregnant women attending an Australian maternity hospital. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51: 333–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordeng H, Ystrøm E, Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:207–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Headley J, Northstone K, Simmons H, et al. Medication use during pregnancy: data from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004;60:355–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.[No authors listed] Medication during pregnancy: an intercontinental cooperative study. Collaborative Group on Drug Use in Pregnancy (C.G.D.U.P.). Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1992;39:185–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donati S, Baglio G, Spinelli A, et al. Drug use in pregnancy among Italian women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;56:323–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry A, Crowther C. Patterns of medication use during and prior to pregnancy: the MAP study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2000;40:165–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marín G, Cañas M, Homar C, et al. Uso de fármacos durante el período de gestación en embarazadas de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Rev salud pública 2010;12:722–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Surveillance of antimicrobial consumption in Europe, 2010. Stockholm: ECDC, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith J, Refuerzo J, Ramin S. Treatment and outcome of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. In: Basow D. ed UpToDate. Waltham, MA (accessed 8 Jun 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gadsby R, Barnie-Adshead T, Sykes C. Why won't doctors prescribe antiemetics in pregnancy? BMJ 2011;343:d4387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raymond SH. A survey of prescribing for the management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy in Australasia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:358–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross DS. Hypothyroidism during pregnancy: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. In: Basow DS. ed UpToDate. Waltham, MA (accessed 8 Jun 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis AJ, Bailey C, Galbally M. Anti-depressant use during pregnancy in Australia: findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012; 36:487–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petersen I, Gilbert RE, Evans SJ, et al. Pregnancy as a major determinant for discontinuation of antidepressants: an analysis of data from the Health Improvement Network. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:979–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. Antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and congenital malformations: is there an association? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the best evidence. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e293–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grigoriadis S, Vonderporten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. Prenatal exposure to antidepressants and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;348:f6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grigoriadis S, VonderPorten EH, Mamisashvili L, et al. The effect of prenatal antidepressant exposure on neonatal adaptation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:e309–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cleary BJ, Butt H, Strawbridge JD, et al. Medication use in early pregnancy-prevalence and determinants of use in a prospective cohort of women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19: 408–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olesen C, Thrane N, Henriksen TB, et al. Associations between socio-economic factors and the use of prescription medication during pregnancy: a population-based study among 19,874 Danish women. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:547–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stokholm J, Schjorring S, Pedersen L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of antibiotic administration during pregnancy and birth. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e82932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hämeen-Anttila K, Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, et al. Medicines information needs during pregnancy: a multinational comparison. BMJ Open 2013;3 :pii:e002594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ekman A, Dickman P, Klint Å, et al. Feasibility of using web-based questionnaires in large population-based epidemiological studies. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:103–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Gelder MM, Bretveld RW, Roeleveld N. Web-based questionnaires: the future in epidemiology? Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:1292–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seybert H. Internet use in households and by individuals in 2011. Eurostat Statistics in focus, 2011. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-11–066/EN/KS-SF-11-066-EN.PDF (accessed 13 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Internet World Stats Usage and population statistics. 2012. http://www.internetworldstats.com/ (accessed 13 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Australian Bureau of Statistics Household use of information technology. Australia, 2010–2011. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/8146.0Main.Features12010-11?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=8146.0&issue=2010-11&num=&view= (accessed 13 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Statistics Canada Individual internet use and e-commerce (2010) 2011. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/111012/dq111012a-eng.htm (accessed 13 Nov 2012).

- 46.United States Census Bureau The 2012 statistical abstract. Information & Communications: Internet Publishing and Broadcasting and Internet Usage, 2010. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/information_communications/internet_publishing_and_broadcasting_and_internet_usage.html (accessed 13 Nov 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.