Abstract

The chemotherapy drug Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)) induces crosslinks within and between DNA strands, and between DNA and nearby proteins. Therefore, Cisplatin-treated cells which progress into cell division may do so with altered chromosome mechanical properties. This could have important consequences for the successful completion of mitosis. Using Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy of live Cisplatin-treated Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells, we found that metaphase mitotic spindles have disorganized kinetochores relative to untreated cells, and also that there is increased variability in the chromosome stretching distance between sister centromeres. This suggests that chromosome stiffness may become more variable after Cisplatin treatment. We explored the effect of variable chromosome stiffness during mitosis using a stochastic model in which kinetochore microtubule dynamics were regulated by tension imparted by stretched sister chromosomes. Consistent with experimental results, increased variability of chromosome stiffness in the model led to disorganization of kinetochores in simulated metaphase mitotic spindles. Furthermore, the variability in simulated chromosome stretching tension was increased as chromosome stiffness became more variable. Because proper chromosome stretching tension may serve as a signal that is required for proper progression through mitosis, tension variability could act to impair this signal and thus prevent proper mitotic progression. Our results suggest a possible mitotic mode of action for the anti-cancer drug Cisplatin.

Introduction

For successful cell division, cells must faithfully contribute a copy of their genetic material to each daughter cell without error. For eukaryotes, this requires a microtubule-based mitotic spindle, which uses force-generating microtubules and motor proteins to align and segregate chromosomes1–7.

The alignment of chromosomes at the center of the mitotic spindle during metaphase is accomplished by dynamic kinetochore microtubules. In budding yeast, a single kinetochore microtubule binds to each kinetochore, which is the essential linker between the microtubules, which segregate duplicated sister chromosomes, and the chromosomes themselves8,9 (Fig. 1A, green). During metaphase, kinetochore microtubules dynamically grow and shorten, thus acting to align their end-attached chromosomes at the spindle equator10,11 (Fig. 1A). Metaphase kinetochore alignment at the spindle equator is achieved through the precise regulation of kinetochore microtubule dynamics12,13. It has been previously proposed that kinetochore microtubule dynamics may be regulated in part by chromosome stretching tension14,15. When kinetochore microtubules shorten, they pull on their end-bound chromosomes, leading to stretching tension between sister chromosomes. This stretching tension may then act to regulate tension-dependent kinetochore microtubule dynamics12,15–24. Additionally, low tension may act as a signal to activate a mitotic checkpoint, which halts mitosis until incorrect attachments are corrected, and proper tension is restored18,25.

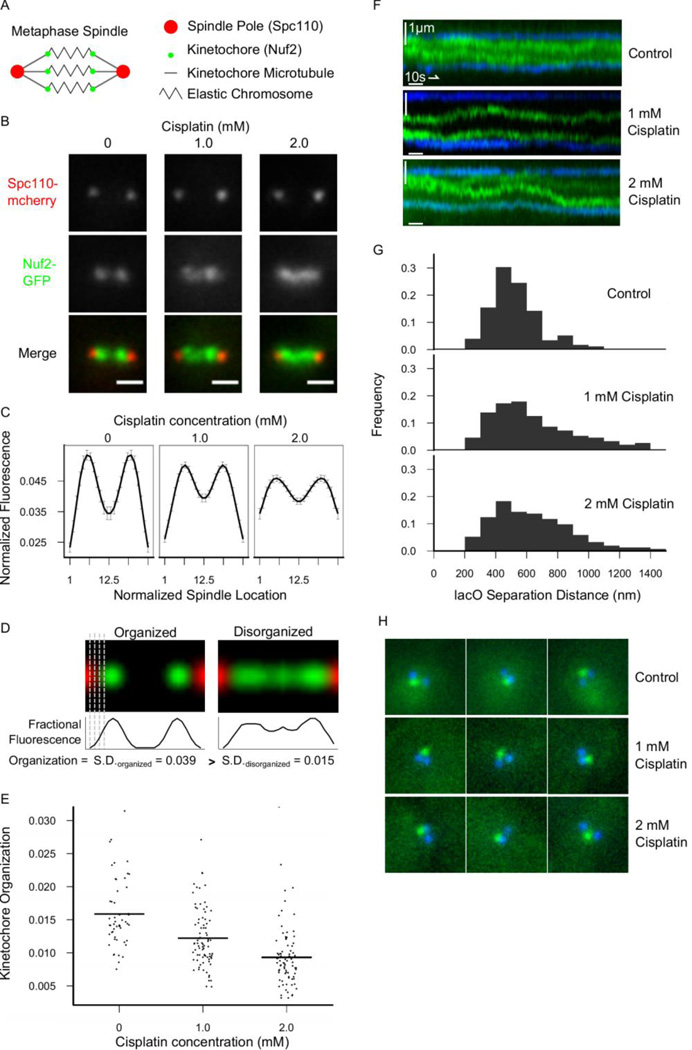

Figure 1. Cisplatin causes disorganized kinetochores and increases variation in chromosome stretch distance during budding yeast mitosis.

(A) Cartoon showing three properly oriented chromosomes in a S. cerevisiae metaphase spindle. (B) Live S. cerevisiae cells grown in increasing concentrations of Cisplatin for four hours before imaging. (Scale bar = 1µm). (C) Normalized fluorescence distributions averaged over all cells after binning into equal spindle lengths. (Error Bars = SEM) (D) Method for measuring kinetochore organization by examining the standard deviation of fractional fluorescence along metaphase spindles. (E) Kinetochore organization in S. cerevisiae metaphase cells as a function of Cisplatin concentration. Horizontal lines indicate arithmetic means. (F) Kymographs showing sister LacO spot dynamics in untreated or Cisplatin-treated cells. (G) Distances between sister lacO spots, indicative of chromatin stretching distance. Note that distances less than 200 nm were not measured due to the diffraction limit of the microscope. Control n cells = 175, 1mM n = 152, 2mM n = 153. (H) Three representative images of sister lacO spots after treatment with nocodazole to depolymerize microtubules, in order to estimate chromosome spring rest length. All Cisplatin treatments lasted four hours before imaging.

Environmental insults can stochastically affect DNA and chromosomes, potentially altering their mechanical properties, including stiffness. For example, the anti-cancer drug Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II)) stochastically creates covalent bonds within a DNA strand, between DNA stands, and between DNA and nearby proteins26,27. This could cause differences in stiffness between chromosomes. Intriguingly, if Cisplatin is applied to cells where the tension-sensing checkpoint protein Aurora B16,18,28 is inhibited, cell survival is much lower, suggesting that tension may be aberrant after Cisplatin application29. Therefore, it may be that Cisplatin leads to changes in chromosome stiffness during mitosis, thus altering the chromosome stretching tension that is sensed by dynamic kinetochore microtubules.

Here, we examined the mitotic effects of Cisplatin on budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells. Budding yeast is an excellent model for studying the effects of Cisplatin during mitosis, because budding yeast has a single microtubule associated with each kinetochore in the spindle, thereby simplifying observations of the relationship between chromosome stiffness and tension-dependent kinetochore microtubule dynamics. In the more complex spindles of higher eukaryotes, there are multiple microtubules per kinetochore, so that, although similar principles may apply, the effect of chromosome stiffness and tension on individual kinetochore microtubule dynamics may be more difficult to discern8,30.

In this work, we found that after Cisplatin treatment, the kinetochores in budding yeast metaphase spindles were disorganized. In addition, there was increased variability in chromosome stretching distances between individual sister kinetochore pairs, suggestive of increased variability in mitotic chromosome stiffness. Through stochastic modeling, we found that substantial chromosome stiffness variability can explain kinetochore disorganization during metaphase. Therefore, Cisplatin could disrupt proper cell cycle progression by stochastically modifying chromosome mechanical properties.

Results and Discussion

Metaphase Kinetochore Organization is Disrupted with Cisplatin Treatment

To ascertain the effect of the DNA-crosslinking agent Cisplatin on metaphase spindles, wild-type cultures of S. cerevisiae were treated with increasing doses of Cisplatin. Kinetochore organization phenotypes were observed using a cell line with two fluorescent fusion genes: 1) Spc110-mcherry, which labels spindle poles, and (2) Nuf2-GFP, which labels outer kinetochores (Fig. 1A). Although cells reproduced more slowly after four hours of Cisplatin treatment, as previously shown31,32, cells which continued through the cell cycle could be observed during metaphase. We found that with increasing doses of the drug, metaphase mitotic spindles exhibited a dose-dependent loss of kinetochore organization (Fig. 1B). This implies that kinetochore microtubule lengths were also becoming more variable, because kinetochore location reports the plus-end locations of kinetochore microtubules.

To ensure that cisplatin was not substantially altering the kinetochore structure, we measured the total kinetochore fluorescence in the spindle after background subtraction. We did not observe a decrease in total nuf2-GFP background-corrected spindle fluorescence after cisplatin treatment as compared to controls (mean ± SD Nuf2 fluorescence AU, control: 14101 ±4532 (n=70), 1mM:17935 ± 5192 (n = 66), 2mM: 16018 ± 4285 (n = 32)). Therefore, we conclude that Cisplatin does not significantly alter the binding affinity of Nuf2-GFP for the kinetochore.

By averaging kinetochore fluorescence along the spindle axis, quantitative analysis of the kinetochore-associated spindle fluorescence demonstrated that, on average, Cisplatin treatment led to increased kinetochore fluorescence in the spindle equator and at the poles, without obviously changing the peak fluorescence location (Fig. 1C). This quantitative result supported our qualitative observation that Cisplatin treatment leads to a kinetochore disorganization phenotype during metaphase.

To further quantify the kinetochore disorganization, we reasoned that the fluorescent kinetochore signal would have the highest standard deviation along the spindle axis when kinetochores were highly organized into two clusters (Fig. 1D, left) and lower standard deviations when kinetochores became disorganized, due to the increase in uniformity of the fluorescence signal (Fig. 1D, right). Therefore, we denoted this standard deviation as “kinetochore organization,” and used it as a single metric with which to compare organization among spindles. Note that the organization reported by this metric is specifically the variability in kinetochore location, and does not assess whether the kinetochores are correctly positioned relative to the poles. For example, this metric will give a value of “organized” if the kinetochores are all clustered at the center of the spindle. Nevertheless, as suggested from the images and the average fluorescence distributions (Fig. 1B,C), kinetochore organization is significantly decreased after four hours of Cisplatin treatment (Fig. 1E, F2,214=33.2, p « 0.0001, one-way ANOVA).

Kinetochore organization could decrease for two reasons: sister kinetochores could have more variable distances between each other (suggestive of variations in chromosome stiffness or changes in chromosome spring rest length) or equidistant sister kinetochore pairs could be less aligned at the metaphase plate. To examine whether sister kinetochores had more variable distances between each other, we examined the distances between centromeres of sister chromosome pairs using a cell line with a lacO array integrated near to the centromere (“lacO spots”), and which simultaneously expressed lacI-GFP and Spc110-mcherry33. Although the lacO spots did not appear to cross the spindle equator with greater frequency in cisplatin treated cells (Fig. 1F), we found that lacO separation distances were more variable after four hours in 1mM or 2mM Cisplatin (Fig. 1G). We calculated the standard deviation of lacO separation distance across many cells (control n = 175, 1mM n = 152, 2mM n = 153) and found that the standard deviation of lacO separation distance in control cells was 158 nm compared to 292 nm and 252 nm in 1mM and 2mM cisplatin-treated cells, respectively. This increase in lacO separation distance variability after Cisplatin treatment was statistically significant when compared using Levene’s Test for Homogeneity of Variance (F2,477 = 17.3, p « 0.0001). The histograms showing increased variability of lacO separation distance appear right-tailed, perhaps because it is experimentally intractable to measure separation distances smaller than the diffraction limit of our microscope (Fig. 1G).

We then performed experiments to determine whether the rest lengths of the chromosome spring had changed after cisplatin treatment. Four hours after initiating Cisplatin and control treatments, we applied nocodazole treatment to cells. This treatment depolymerizes microtubules, and thus removes all tension from the chromosome spring. In nocodazole, the sister lacO spots collapsed to a single diffraction-limited spot under all treatments (Fig. 1H), suggesting that the rest length of the chromosome spring was not changed after cisplatin treatment. Thus, the increased variability in lacO separation distances suggests that Cisplatin treatment leads to an increased variability in mitotic chromosome stiffness.

As far as we are aware, the potential effects of Cisplatin in increasing the chromosome stiffness variability during mitosis have not been previously explored. Therefore, we investigated the potential effects of chromosome stiffness variability on mitotic phenotypes using a stochastic model.

Simulations suggest that stochastic variation in chromosome stiffness could disrupt kinetochore organization

To evaluate the potential effect of variations in stiffness from chromosome to chromosome on kinetochore congression during metaphase, we modified a previously published model12, in which dynamic kinetochore microtubules in a yeast metaphase spindle stochastically grow, shorten, rescue, and catastrophe. Importantly, the frequency of rescue in the model (i.e., the frequency of a microtubule transitioning from shortening to growing) depended on chromosome stretching tension, where increased stiffness (κ) led to increased rescue frequency (kR) beyond baseline rescue (kR,0) due to tension imparted by chromosome stretching (Δx) (See Eqn. 2, Materials and Methods). The previously published model explored how proper kinetochore alignment during metaphase depended upon a tension-dependent microtubule rescue frequency, but examined only fixed levels of stiffness among chromosomes within a spindle12. Therefore, we used this model to explore how variability in stiffness could affect proper kinetochore alignment during metaphase. To compare simulation results to experimental microscope fluorescence images, we convolved modeled particle locations with the point-spread function of the microscope34 (Fig. 2A). Thus, by simulating kinetochore-labeled images, we were able to measure kinetochore organization as we did in live cells.

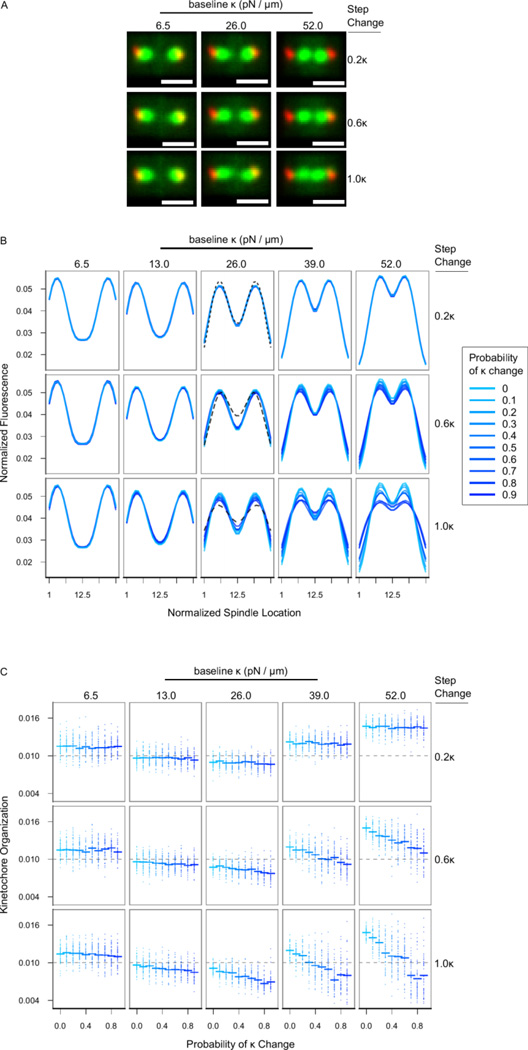

Figure 2. Kinetochore organization measured using fluorescence is stable in simulated spindles except when chromosome stiffness varies by large amounts.

(A) Simulated images created by convolving the microscope’s point-spread function onto the 3-dimension locations of the spindle poles and kinetochores at the end of simulation runs. Here, the images were generated from simulations where Pκchange = 0.6. (B) Normalized fluorescence distributions from simulations, with data from simulations varying along all three dimensions. Not all levels Pκchange are visible due to extensive overlap. The experimental fluorescence curves from Fig. 1C are overlaid here: The control cell fluorescence distribution is overlaid as the black dotted line in the top-middle, the 1mM Cisplatin-treated fluorescence distribution is the finer black dotted line in the middle-middle, and the 2mM Cisplatin-treated fluorescence distribution is the finest black dotted line in the bottom-middle. (C) Kinetochore organization in simulated spindles with varying stiffness conditions. Dots are results from individual replicates and horizontal lines indicate arithmetic means of all replicates. Color is Pκchange, as in (B).

Using this model, we examined the effect of the following parameters on the simulated metaphase kinetochore organization: (1) the baseline chromosome stiffness (κ in pN/µm), (2) the probability that a chromosome in a simulated spindle would have altered κ (Pκchange), and (3) the step size for the change in κ in chromosomes with altered κ (step change). This was applied as follows: if a chromosome was assigned a change in κ (because a uniformly distributed random number between 0 and 1 was less than Pκchange), then that chromosome’s κ was randomly modified by ± step size.

In each treatment, we simulated 50 spindles for ~15 minutes real-time. We tested the effects of nine levels of κ, ten levels of Pκchange, and six levels of fold κ change, resulting in 540 treatments and 27000 simulated spindles (complete simulation dataset shown in Fig. S1).

The initial simulated phenotype we examined was the average fluorescence distribution of kinetochores after ~15 simulated minutes, determined from model convolution of the simulated microtubule plus-end locations (Fig 2A,B). A few salient points are evident in this data: First, as κ increases (moving from left to right), the peaks of the half-spindle fluorescence move closer to the spindle equator, in contrast to our experimental Cisplatin-treated cells, whose peak location remains constant. Second, as Pκchange increases (from colder to warmer colors), the width of each peak increases, which brings up both the valley between the peaks and also the spindle pole fluorescence, similar to the experimental Cisplatin-treated cells. Third, the magnitude of this effect depends in large part upon both the step change in κ, as well as on the baseline κ, such that the greatest kinetochore disorganization is observed in spindles with high baseline κ that is able to significantly fluctuate from chromosome to chromosome with a high probability. Lower amounts of variability in stiffness among chromosomes did not noticeably cause changes in the normalized fluorescence distributions (Fig. 2B).

Similar to our analysis of the Cisplatin-treated experimental data, we next quantitatively compared kinetochore organization in our modeled spindles by determining the kinetochore organization metric from the kinetochore-associated fluorescence distrubutions in each case. Here, we analyzed the effect of the base-line κ, step-change in κ, and Pκchange on kinetochore organization. Using a 3-way ANOVA, we found significant main effects and interaction terms for all variable combinations (Table S1, Fig. S2). Our interpretation of the kinetochore organization data is as follows.

It is evident that in cells where the step-change in κ is low (Fig. 2C, upper row), kinetochore organization is determined by κ and depends very little on Pκchange. Extreme organization occurs at the extremes of stiffness—with κ = 0 or κ = 52 pN / µm, as most kinetochores are stuck either at the spindle poles or very near to the spindle equator. However, as the step-change in κ increases (Fig. 2C, moving down), we see that kinetochore organization decreases, and, importantly, the kinetochore organization also decreases with Pκchange. Interestingly, the cell-cell variability in disorganization (as shown by the spread of points in each case) increases with higher baseline κ, higher step-change in κ,(Fig. 2C, bottom-right), and higher Pκchange (warmer colors), even as the average organization decreases. This suggests a counterintuitive prediction: observations of variable kinetochore organization among cells (i.e., the range of observations from highly organized to very disorganized) may be evidence of more extreme chromosome stiffness variability than would observations of constant kinetochore disorganization across cells.

Simulations suggest that stochastic variation in chromosome stiffness leads to increased variability in metaphase kinetochore microtubule length and chromosome stretching tension

Mitotic metaphase spindles sense chromosome stretching tension and use this tension both to regulate microtubule dynamics, and perhaps also as a signal to satisfy a metaphase checkpoint16,20,35,36. Therefore, small variations in kinetochore microtubule length and tension may be important even if gross kinetochore disorganization phenotypes are not observed. Thus, we examined kinetochore microtubule lengths and tension in our model. In cells, one consequence of uniformly altered chromosome stiffness may be a change in spindle length37. By keeping spindle length constant in our model, we could learn how microtubule lengths and tension change as a function of chromosome stiffness and stiffness variability, disentangled from effect of dynamic spindle lengths. This assumption is reasonable given that Cisplatin treatment did not consistently change average experimental metaphase spindle lengths.

With constant spindle length, average kinetochore microtubule lengths predictably increased with increasing κ and were significantly but only moderately affected by the step-change in κ, and by Pκchange (Fig. 3A). However, the standard deviation of kinetochore microtubule lengths increased significantly with Pκchange, especially at high values of the step-change in κ (Fig. 3B).

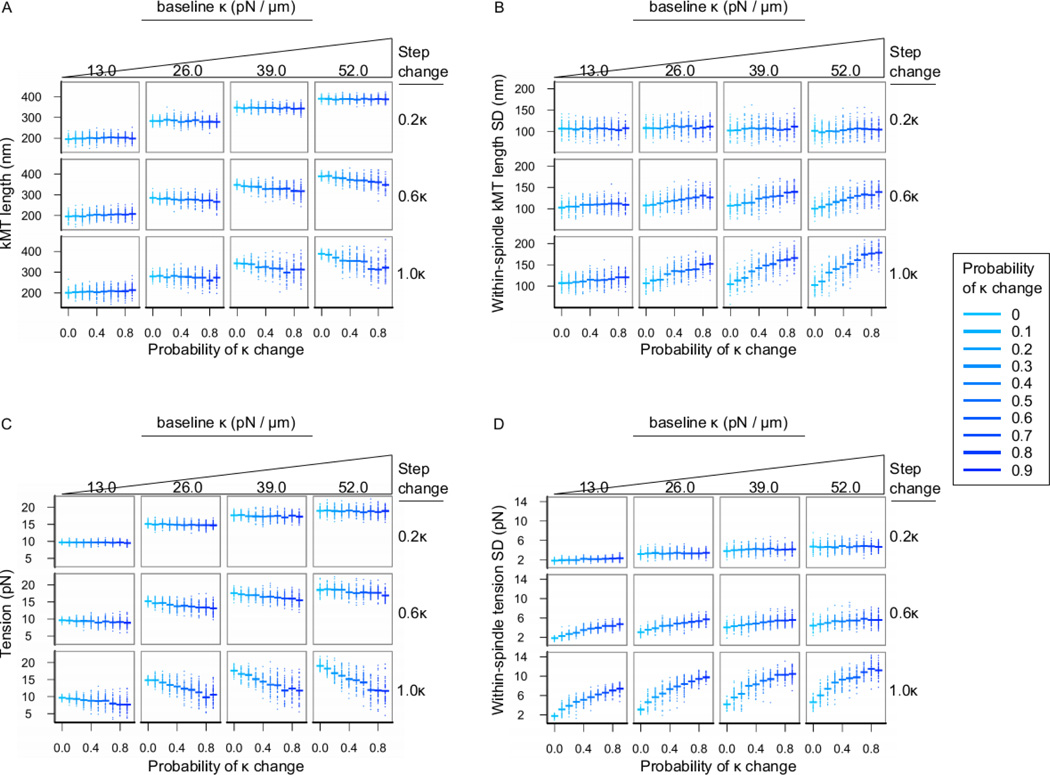

Figure 3. Increasing variability in chromosome stiffness causes increased standard deviation of kinetochore microtubule lengths and tension.

The results here are from the same models as in Fig. 2, with fewer parameter combinations shown for clarity. (A) Average within-spindle kinetochore microtubule length, (B) standard deviation of kinetochore microtubule length within spindles, (C) average within-spindle tension, and (D) standard deviation of chromosome-stretching tension within spindles after 15 minutes of simulation time. Dots are data from individual spindle simulations (n = 50 spindles per treatment) and horizontal lines are the arithmetic mean within a treatment.

The effects of chromosome to chromosome variations in stiffness on kinetochore microtubule lengths as described above are mirrored by the effects of variability in chromosome stiffness on chromosome stretching tension. Mean tension on chromosomes within a spindle increases as baseline κ increases and starts to plateau at higher levels of κ (Fig. 3C). Maintenance of mean tension within a baseline κ is relatively robust to increasing κ variability and the amount by which κ can fluctuate, although at extremes of both (Fig. 3C, bottom-right), mean tension begins to vary across spindles.

However, while mean tension within a spindle is not strongly affected by variability in chromosome stiffness, the standard deviation of tension within simulated spindles increases with Pκchange, especially when the step-change in κ is high (Fig. 3D). Therefore, when kinetochore organization decreases due to an increase in chromosome to chromosome variations in stiffness, chromosome stretching tension is inconsistent between different chromosome pairs in the spindle.

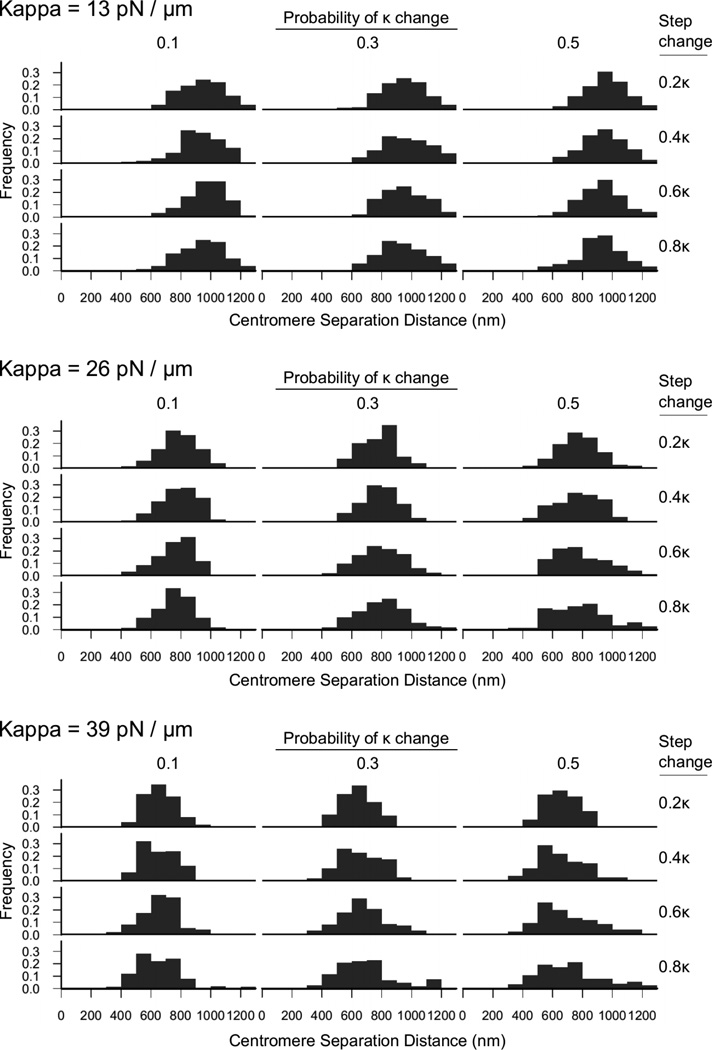

Importantly, by allowing the simulated chromosome stiffness to vary, we were able to recapitulate the increased variability in sister lacO spot separation distances as was observed inside of cells (Fig. 1G). For any given baseline level of simulated chromosome stiffness (Fig. 4, three stiffnesses shown), as we allowed the probability of stiffness change to increase and/or the stiffness step change to increase (Fig. 4, moving down-right), the simulated variability in lacO separation distance was increased (Fig. 4). Thus, varying the chromosome stiffness recapitulates both the kinetochore fluorescence distributions and the lacO separation distributions observed in vivo after cisplatin treatment.

Figure 4. Increased variability in centromere separation distance results from increasing the probability of changes in stiffness and the size of the stiffness changes.

Similar to Fig. 1G, we captured one simulated sister centromere separation distance from each simulated spindle after 10 minutes of simulation time and plot here histograms of these separation distances from 150 simulated spindles. Three baseline stiffnesses are shown here (top, middle, bottom).

Overall, chromosome stretching tension was variable when chromosome stiffness was large and variable. However, is also important to note that, in general, our sensitivity analysis showed that the mitotic spindle can exhibit relatively consistent tension values over a wide range of parameter values, only showing abnormalities at extreme parameter levels. This suggests that dynamic, tension-sensing microtubules could efficiently compensate for minor fluctuations in mitotic chromosome stiffness.

Conclusions

In summary, we found that metaphase kinetochore congression was disrupted in cells after treatment with the chemotherapy drug Cisplatin, which stochastically crosslinks DNA to itself and to proteins. In addition, metaphase chromosomes are stretched more variably with Cisplatin treatment. Computational modeling results suggested that kinetochore disorganization and variations in tension could occur when there was significant variability in stiffness between chromosomes. Therefore, the observations we made in live cells after Cisplatin treatment are consistent with a change in chromosome stiffness variability (Fig. 5).

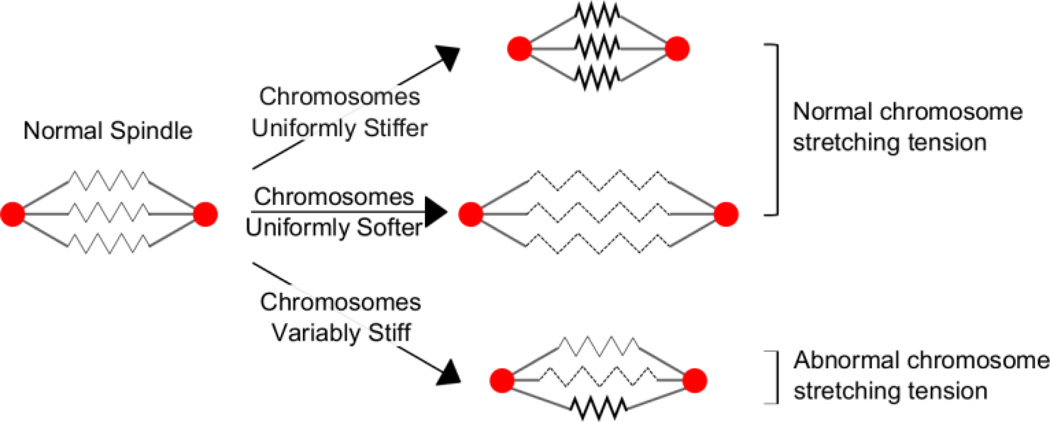

Figure 5. Hypothetical model showing the inability of mitotic spindles to maintain normal chromosome stretching tension when chromosomes are variably stiff.

Here spindle poles are red, kinetochore microtubules are grey, and chromosomes are represented by a black sawtooth in which stiffness is abnormally high when bolded and abnormally low when dashed. When the chromosomes in a normal cell (left) become uniformly stiffer (top) or softer (middle), the mitotic spindle may compensate by changing its length to maintain normal chromosome stretching tension with low variability. In contrast, if the chromosomes within a cell have variable stiffness (bottom), no global compensatory mechanism can work to maintain proper tension in all chromosomes, perhaps resulting in increased tension variability.

Intuitively, it seems paradoxical that a crosslinking agent such as Cisplatin could increase the variability in chromosome stiffness, rather than just increasing the stiffness itself. For example, previous in vitro studies have reported that cisplatin treatment led to a reduced persistence length of naked DNA, which would have the effect of increasing tensile stiffness38,39,40. However, in cells the chromosomes are composed of DNA and also DNA binding partners such as histones, topoisomerase complexes, and cohesin and condensin complexes, all of which may contribute to chromosome stiffness41–45. Specifically, cisplatin has been shown to interfere with the catalytic activity of topoisomerase 246, which, according to previous reports, may lead to decreased chromosome stiffness47. Therefore, the net effect of cisplatin on chromosomes could be either to stiffen or to soften the chromosomes, or a mixture of these effects.

Metaphase spindles read out chromosome stretching tension as a signal to allow proper progression of the cell from metaphase into anaphase, and also as a way to directly regulate kinetochore microtubule lengths16,21,25,48. When chromosome stiffness is globally and uniformly altered in a cell, the mitotic spindle may respond by both by adjusting kinetochore microtubule lengths, and also by passively changing spindle length as a consequence of the balance of forces in the spindle between molecularmotors and chromosome stretching tension37,47. However, our results suggest that when stiffness becomes variable between different chromosomes in one mitotic spindle, cells may not be able to completely compensate for this variability. Thus, tension-based signaling may become impaired, leading to negative consequences for cell cycle progression (Fig. 5). This effect could produce a mitotic mode action for the anti-cancer drug Cisplatin, in addition to its well established role in activating the DNA damage checkpoint. Indeed, combination therapy of Cisplatin with the anti-mitotic drug paclitaxel increases cell mortality26.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Microscopy

We visualized live Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells using a Nikon Eclipse Ti microscope equipped with 488nm and 561nm lasers directed using a Ti-TIRF-PAU system for total internal reflectance microscopy. We captured images using an Andor iXon3 EM-CCD camera after magnification with a Nikon CFI Apochromat 100× 1.49 NA oil objective and 2.5× projection lens.

Two yeast strains were used in this experiment. To visualize spindle poles and kinetochores, we used strain MGY55 (MAT alpha ade2-1oc ade3-delta can1-100 his-11,15 leu2-3,112 NUF2-GFP::HISMX SPC110-mCherry::hphMX trp1-1 ura3-1). To visualize spindle poles and the centromere of chromosome 3, we used strain MGY5 (MATa ura3-1 ade2-1 his3-11,-15 leu2-3,-112 can1-100 trp1-1 CEN3 lacO (Kan) GFP-lacI:HIS3 SPC110-mCherry::hphMX HIS2).

Cells were grown overnight at 26°C in YPD media supplemented with adenine, then diluted into SD complete media supplemented with adenine and grown at 30°C for four additional hours prior to imaging to encourage log-phase growth. Cisplatin was kept in DMSO aliquots. For Cisplatin and control experiments, yeast dilutions were also treated Cisplatin or the same amount of DMSO lacking Cisplatin for four hours. For nocodazole experiments, after the four hour Cisplatin (or control) treatment, cells were resuspended in SD and Cisplatin or DMSO that in each case was supplemented with 15 µg / ml nocodazole. Imaging commenced after 15 minutes of nocodazole treatment to allow for microtubule depolymerization. To image cells, the cells were affixed to concanavalin-A-coated coverslips and imaged in the same media within which they were grown.

Yeast Image Analysis

All image analysis was done using custom-made programs in Matlab. The pixel size of our images (based on the camera and objective combination) was 64 nm. All analysis began similarly: images were loaded into Matlab then filtered with a fine-grain noise filter using fspecial() with a diameter = 7 pixels and standard deviation = 1 pixels. Then, background was removed by subtracting an image created by using fspecial() on the original image with a diameter = 210 pixels and standard deviation = 30 pixels (thus, this removed background green autofluorescence filling the nuclei without affecting kinetochore fluorescence). Next, spindles were rotated so the spindle sat on the horizontal axis by having on the spindle poles and the resulting angle put into imrotate(). Precise spindle pole locations found along the spindle axis by fitting a two-Gaussian mixture model to the pole fluorescence gmdistribution.fit().

To measure kinetochore fluorescence along the spindle, for each x-position along the spindle to pole the fluorescence was averaged in a 15-pixel column centered on the spindle axis. To across-cell and across-treatment comparisons, this fluorescence vector was binned into 24 mirrored, such that bins 1 and 24 both equaled the average value of those bins, bins 2 and their average value, etc. To compare kinetochore organization among cells, we found the deviation of the binned, mirrored, fluorescence vector for each cell and used this as a single metric.

To find the distance between centromere spots in strain MGY5, gmdistribution.fit() was used mean locations of a 2-Gaussian mixture model of the centromere fluorescence.

To create the kymographs in Fig. 1F, after rotating spindles in Matlab as described above, saved and brought into Image-J to make a kymograph using the reslice function.

Stochastic Modeling

We used a previously described simulation12 to better understand the effect that variable stiffness could have on kinetochore organization. This simulation models a metaphase budding spindle with a fixed spindle length and 32 dynamic microtubules bound singly to kinetochores elastic chromosomes. It is a Monte Carlo model with a fixed time step.

Microtubules grew and shortened in the×plane. Their z-y origin location was chosen randomly circle of radius 125 nm (approximating the size of a spindle pole8). Microtubule dynamics main components: fixed growth and shortening rates (2 µm min−1 ), fixed baseline probabilities catastrophe kC,0 = 0.14 s−1 and rescue kR,0 = 0.25 s−1, and the ability for catastrophe and rescue beyond their baseline. This worked as follows:

A kinetochore microtubule’s chance of catastrophe increased linearly with its length49:

| (1) |

With LMT = microtubule length in µm and α = a free parameter relating microtubule length to catastrophe that was constrained using wild-type experimental data.

Also, when a kinetochore microtubule was under tension due to stretching of its elastic chromosome, the microtubule’s chance of rescue increased:

| (2) |

with kR = rescue frequency in s−1 and Δx = the amount by which the chromosome is stretched in µm. Rescue depends on the stiffness of the chromosome with κ*= κ/F0, a free parameter that is chromosome stiffness κ in pN/µm modified by F0, the characteristic force that increases rescue e-fold.

We constrained the free parameters in the model by comparing simulated images created from simulations with different parameter sets to experimental images34,50. We ran simulations using the same set of spindle lengths as observed experimentally in our DMSO control, kinetochore-labeled cells (Fig. 1A), convolved simulated fluorescent images from the simulations using labeled poles and outer-kinetochores, and created average, mirrored, binned kinetochore fluorescence distributions which we overlayed on the experimental fluorescence distribution to compare visually. The best match was observed when we ran simulations using α = 120 µm−1 and F0 = 11.75 µm/pN. Deviations in α by more than 10 µm−1 or F0 by more than 0.5 resulted in a poor fit. This level of constraint resulted in a wild-type κ = 26 pN/µm, which is consistent with previous data51.

The primary use of the model was to ascertain the effect of chromosome-to-chromosome variability in stiffness on kinetochore organization. To do this, we ran simulations using the above constrained parameters on spindles with a fixed spindle length of ~ 1300 nm, which equaled the average spindle length in our wild-type cells. However, we varied three major parameters: 1) Baseline κ (pN/µm), which could equal [0, 6.5, 13.0, 19.5, 26.0, 32.5, 39.0, 45.5, 52.0], 2) Pκchange, the probability that a particular chromosome would have its baseline κ modified, which could equal [0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9], and 3) Step change, which is the fractional amount by which a chromosome’s baseline κ would change if a random number compared against Pκchange determined that chromosome’s κ would be modified, and which could equal ±[0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0]. Factorial variation of these three parameters resulted in 540 simulation treatments, each of which was run independently 50 times. Simulated spindles were convolved at the end of each run to create the simulated spindle images which were then used to create fluorescence distributions as seen in Fig. 2A. Kinetochore microtubule lengths and tension were taken directly from the model data.

To examine the effects of baseline κ, Pκ change, and step change on different response variables we used a 3-way ANOVA with each independent variable treated categorically, and all interactions included in the models. Response variables examined included kinetochore organization, mean kinetochore microtubule length, standard deviation of microtubule length within a spindle, mean tension, and standard deviation of tension within a spindle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Gardner, Duncan Clarke, Meg Titus and Gant Luxton lab members for useful discussions. This work was supported by the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences (supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts) (M.K.G.) and National Institutes of Health grant GM103833 (M.K.G.). J.M.C. was supported in part by a Postdoctoral Fellowship #124521-PF-13-109-01-CCG from the American Cancer Society.

References

- 1.Nicklas RB. The forces that move chromosomes in mitosis. Annual review of biophysics and biophysical chemistry. 1988;17:431–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumont S, Mitchison TJ. Force and length in the mitotic spindle. Current Biology. 2009;19:R749–R761. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maresca TJ, Salmon ED. Intrakinetochore stretch is associated with changes in kinetochore phosphorylation and spindle assembly checkpoint activity. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;184:373–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchida KSK et al. Kinetochore stretching inactivates the spindle assembly checkpoint. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;184:383–390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wan X, et al. Protein architecture of the human kinetochore microtubule attachment site. Cell. 2009;137:672–684. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mogilner A, Craig E. Towards a quantitative understanding of mitotic spindle assembly and mechanics. Journal of Cell Science. 2010;123:3435–3445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumont S, Salmon ED, Mitchison TJ. Deformations Within Moving Kinetochores Reveal Different Sites of Active and Passive Force Generation. Science. 2012;355 doi: 10.1126/science.1221886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winey M, et al. Three-dimensional ultrastructural analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;129:1601–1615. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiato H, DeLuca J, Salmon ED, Earnshaw WC. The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117:5461–5477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson CG, Maddox PS, Salmon ED, Bloom K. Budding yeast chromosome structure and dynamics during mitosis. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;152:1255–1266. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner MK, et al. Tension-dependent Regulation of Microtubule Dynamics at Kinetochores Can Explain Metaphase Congression in Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3764–3775. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner MK, et al. Chromosome congression by Kinesin-5 motor-mediated disassembly of longer kinetochore microtubules. Cell. 2008;135:894–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franck AD, et al. Tension applied through the Dam1 complex promotes microtubule elongation providing a direct mechanism for length control in mitosis. Nature cell biology. 2007;9:832–837. doi: 10.1038/ncb1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers AF, et al. The Ndc80 Kinetochore Complex Forms Load-Bearing Attachments to Dynamic Microtubule Tips via Biased Diffusion. Cell. 2009;136:865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biggins S, Murray aW. The budding yeast protein kinase Ipl1/Aurora allows the absence of tension to activate the spindle checkpoint. Genes & development. 2001;15:3118–3129. doi: 10.1101/gad.934801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asbury CL, Gestaut DR, Powers AF, Franck AD, Davis TN. The Dam1 kinetochore complex harnesses microtubule dynamics to produce force and movement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:9873–9878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinsky BA, Kung C, Shokat KM, Biggins S. The Ipl1-Aurora protein kinase activates the spindle checkpoint by creating unattached kinetochores. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:78–83. doi: 10.1038/ncb1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouck DC, Bloom K. Pericentric chromatin is an elastic component of the mitotic spindle. Current Biology. 2007;17:741–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakhoum SF, Thompson SL, Manning AL, Compton DA. Genome stability is ensured by temporal control of kinetochore-microtubule dynamics. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ncb1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiyoshi B, et al. Tension directly stabilizes reconstituted kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Nature. 2010;468:576–579. doi: 10.1038/nature09594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khodjakov A, Pines J. Centromere tension: a divisive issue. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:919–923. doi: 10.1038/ncb1010-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lampson MA, Cheeseman IM. Sensing centromere tension: Aurora B and the regulation of kinetochore function. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011;21:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson SL, Compton DA. Chromosome missegregation in human cells arises through specific types of kinetochore–microtubule attachment errors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109720108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Indjeian VB, Stern BM, Murray AW. The centromeric protein Sgo1 is required to sense lack of tension on mitotic chromosomes. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2005;307:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1101366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milross CG, Peters LJ, Hunter NR, Mason Ka, Milas L. Sequence-dependent antitumor activity of paclitaxel (taxol) and cisplatin in vivo. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer. 1995;62:599–604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, Recognition, and Processing of Cisplatin-DNA Adducts. Chemical reviews. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cimini D. Detection and correction of merotelic kinetochore orientation by Aurora B and its partners. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2007;6:1558–1564. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Zhang S. ZM447439, the Aurora kinase B inhibitor, suppresses the growth of cervical cancer SiHa cells and enhances the chemosensitivity to cisplatin. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2011;37:591–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEwen BF, Ding Y, Heagle aB. Relevance of kinetochore size and microtubule-binding capacity for stable chromosome attachment during mitosis in PtK1 cells. Chromosome research: an international journal on the molecular, s upramolecular and evolutionary aspects of chromosome biology. 1998;6:123–132. doi: 10.1023/a:1009239013215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossmann KF, Brown JC, Moses RE. Cisplatin DNA cross-links do not inhibit S-phase and cause only a G 2 rM arrest in Saccharomyces cereÕisiae. 1999 doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(99)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burger H, et al. A genome-wide screening in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for genes that confer resistance to the anticancer agent cisplatin. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2000;269:767–774. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straight aF, Belmont aS, Robinett CC, Murray aW. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Current biology: CB. 1996;6:1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70783-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gardner MK et al. Model Convolution: A Computational Approach to Digital Image Interpretation. Cellular and molecular bioengineering. 2010;3:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s12195-010-0101-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nezi L, Musacchio A. Sister chromatid tension and the spindle assembly checkpoint. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2009;21:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Indjeian VB, Stern BM, Murray AW. The centromeric protein Sgo1 is required to sense lack of tension on mitotic chromosomes. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2005;307:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1101366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro SA et al. Condensin Regulates the Stiffness of Vertebrate Centromeres. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:2371–2380. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee N-K, et al. Elasticity of Cisplatin-Bound DNA Reveals the Degree of Cisplatin Binding. Physical Review Letters. 2008;101:248101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.248101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hou X-M, et al. Cisplatin induces loop structures and condensation of single DNA molecules. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:1400–1410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howard J. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton. Sundeland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stephens AD, Haase J, Vicci L, Taylor RM, Bloom K. Cohesin, condensin, and the intramolecular centromere loop together generate the mitotic chromatin spring. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;193:1167–1180. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marko J. Micromechanical studies of mitotic chromosomes. Chromosome Research. 2008;16:469–497. doi: 10.1007/s10577-008-1233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kawamura R, et al. Mitotic chromosomes are constrained by topoisomerase II-sensitive DNA entanglements. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;188:653–663. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yong-Gonzalez V, Wang B-D, Butylin P, Ouspenski I, Strunnikov A. Condensin function at centromere chromatin facilitates proper kinetochore tension and ensures correct mitotic segregation of sister chromatids. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2007;12:1075–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerlich D, Koch B, Dupeux F, Peters J-M, Ellenberg J. Live-cell imaging reveals a stable cohesin-chromatin interaction after but not before DNA replication. Current biology: CB. 2006;16:1571–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cantero G, Pastor N, Mateos S, Campanella C, Cortés F. Cisplatin-induced endoreduplication in CHO cells: DNA damage and inhibition of topoisomerase II. Mutation research. 2006;599:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warsi T, Navarro M, Bachant J. DNA topoisomerase II is a determinant of the tensile properties of yeast centromeric chromatin and the tension checkpoint. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19:4421–4433. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skibbens RV, Salmon ED. Micromanipulation of Chromosomes in Mitotic Vertebrate Tissue Cells: Tension Controls the State of Kinetochore Movement. Experimental Cell Research. 1997;235:314–324. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gardner MK, Odde DJ, Bloom K. Kinesin-8 molecular motors: putting the brakes on chromosome oscillations. Trends in cell biology. 2008;18:307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sprague BL et al. Mechanisms of microtubule-based kinetochore positioning in the yeast metaphase spindle. Biophysical journal. 2003;84:3529–3546. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75087-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gay G, Courtheoux T, Reyes C, Tournier S, Gachet Y. A stochastic model of kinetochore-microtubule attachment accurately describes fission yeast chromosome segregation. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:757–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201107124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.