Abstract

Objectives

To examine the volume, relevance and quality of transnational tobacco corporations’ (TTCs) evidence that standardised packaging of tobacco products ‘won't work’, following the UK government's decision to ‘wait and see’ until further evidence is available.

Design

Content analysis.

Setting

We analysed the evidence cited in submissions by the UK's four largest TTCs to the UK Department of Health consultation on standardised packaging in 2012.

Outcome measures

The volume, relevance (subject matter) and quality (as measured by independence from industry and peer-review) of evidence cited by TTCs was compared with evidence from a systematic review of standardised packaging . Fisher's exact test was used to assess differences in the quality of TTC and systematic review evidence. 100% of the data were second-coded to validate the findings: 94.7% intercoder reliability; all differences were resolved.

Results

77/143 pieces of TTC-cited evidence were used to promote their claim that standardised packaging ‘won't work’. Of these, just 17/77 addressed standardised packaging: 14 were industry connected and none were published in peer-reviewed journals. Comparison of TTC and systematic review evidence on standardised packaging showed that the industry evidence was of significantly lower quality in terms of tobacco industry connections and peer-review (p<0.0001). The most relevant TTC evidence (on standardised packaging or packaging generally, n=26) was of significantly lower quality (p<0.0001) than the least relevant (on other topics, n=51). Across the dataset, TTC-connected evidence was significantly less likely to be published in a peer-reviewed journal (p=0.0045).

Conclusions

With few exceptions, evidence cited by TTCs to promote their claim that standardised packaging ‘won't work’ lacks either policy relevance or key indicators of quality. Policymakers could use these three criteria—subject matter, independence and peer-review status—to critically assess evidence submitted to them by corporate interests via Better Regulation processes.

Keywords: PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of the study.

This study builds on the existing literature on corporate influence over public health policy to demonstrate the challenges policymakers face in assessing evidence submitted via public consultations.

Further investigation of policymakers’ perceptions of corporate evidence would be beneficial to corroborate the pertinence of our recommendations.

Indicators were used to assess quality as these would be suited to the practical demands of the policymaking context.

Introduction

Standardised packaging of tobacco products entails the prohibition of logos, brand imagery, symbols, other images, colours and promotional text from tobacco products and tobacco product packaging. Despite the common use of the term ‘plain packaging’ in media coverage of this issue, graphic and textual health warning labels would still feature prominently on packs and key anticounterfeiting marks would be retained.

Standardised packaging would further restrict the already limited opportunities of transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) to market their products. The policy's objective is to deter smoking initiation, particularly among young people, and promote cessation among existing smokers. Its introduction in Australia in December 20121 sparked a wave of interest: Ireland and New Zealand gave strong indications of their intentions to introduce standardised packaging. In contrast, the UK government announced on 12 July 2013 that it had decided to wait for ‘emerging evidence’ from Australia on the impacts of standardised packaging before taking a policy decision. This announcement followed a lengthy debate which began in 2011,2 included a 4-month public consultation ending in August 2012,3 and was subject to nearly a year's deliberation within the Department of Health before the consultation report was published.4 The consultation aimed to inform policy development and gather additional evidence for an impact assessment. The impact assessment was rated amber (needing more work) by the Regulatory Policy Committee (RPC) in February 2012.5

Public consultations and impact assessments are processes within a global governance innovation termed Better Regulation (also known as Smart regulation or better lawmaking). Drawing heavily on American Administrative Law and the cost-benefit approach to regulatory review in the USA,6 7 versions of Better Regulation are in place, for example, in multiple European Union (EU) states (UK, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Sweden and Germany),8 in the EU itself9 and in Canada10 and Australia.11 A key impetus for Better Regulation has been the pressure put on governments and inter-governmental organisations by TTCs and other transnational corporations to reduce regulatory business costs and prioritise business interests in the policy process.8 12

Public consultations effectively frontload problem-resolution in the policy process by offering affected businesses and other interested parties an early opportunity to comment on policy ideas and proposals, and to submit evidence supporting their views.13 14 Examples of consultation systems elsewhere include ‘notice and comment’ in the USA15 and the European Commission's ‘Your voice in Europe’.16 Evidence gathered from consultations can then be taken into account in developing impact assessments, which entail quantitative evidence-based assessments of the potential effects of proposed regulations and consideration of alternative policy options.17 Evidence plays a key role in the policy process, and, in practice, Better Regulation underpins a form of evidence-based policymaking which is deliberately open to stakeholder, and particularly business, influence.18 19

In the UK, these processes contribute to the attainment of five features of good governance: proportionality, accountability, consistency, transparency and targeting.14 20 Under New Labour18 and the Coalition Government,8 Better Regulation has formalised evidence-based policymaking, which is now subject to two stages of scrutiny: first, by the RPC (a body sponsored by the Department of Business Innovation and Skills); and, subsequently, by the Cabinet's Reducing Regulation Committee (RRC). The upfront costs to the government of this process are intended to be offset by an associated reduced impact on businesses post-implementation.

New tobacco control policies developed by the Department of Health are subject to Better Regulation. Thus, TTCs can make submissions to public consultations on tobacco control policies, citing evidence regarding impacts on their businesses, wider impacts and in support of alternative policies. Yet, the government is also required to meet an international commitment made under Article 5.3 of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) to take steps to ensure that: “…in setting and implementing their public health policies with respect to tobacco control, Parties shall act to protect these policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry in accordance with national law.”21 A key rationale for this provision lies in the overwhelming evidence of the tobacco industry's efforts to bias the evidence base of health impacts of tobacco products and public health policies in its favour.22–25 Uniquely in the case of tobacco, the coexistence of these two governance regimes raises the possibility of a regulatory conflict between commitments to include businesses in policy development and commitments to protect public health policies from them.26

The UK's consultation3 and impact assessment5 on standardised packaging provides an opportunity to consider how these two sets of commitments are reconciled by governments. The four largest TTCs in the UK market—Imperial Tobacco (IT), Japan Tobacco International (JTI), Philip Morris Ltd (PM) and British American Tobacco (BAT)—submitted lengthy consultation responses (1521 pages in total, of which 328 comprised their main responses and 1193 provided supplementary materials).27–30 These were just 4 of 668 433 responses the Department of Health received (2444 were ‘detailed responses’).4 Associated time and resource costs raise the question of how governments can effectively make a balanced, informed and transparent assessment of the policy relevance and the quality of all evidence cited in submissions.31

A systematic review of the evidence for standardised packaging, commissioned by the Department of Health, concluded that there is ‘strong evidence’ that standardised packaging would reduce the appeal of tobacco products and increase the prominence of health warnings.32 However, in their submissions, TTCs rejected the findings of the systematic review on the grounds that there is no evidence that standardised packaging would reduce smoking prevalence or initiation.27–30 They cited extensive evidence to support their arguments, claimed that key evidence on smoking behaviour had not been considered in the systematic review, and pointed to the absence of real-world evidence as problematic: the UK consultation preceded implementation of standardised packaging in Australia in December 2012. The TTCs have maintained that advertising and promotional material—including packaging—stimulate only brand switching among current smokers.27 29 30 33 Yet, overwhelming evidence from the tobacco industry's own marketing documents suggests this claim is highly disingenuous.34–37

In this article, we aim to examine the volume, policy relevance and quality of the evidence TTCs cited in their submissions and compare it with that included in the systematic review (further work is underway to investigate TTCs’ interpretation of the evidence itself). We use this analysis to explore the challenges public consultations and impact assessments for tobacco control policies present to governments and begin to unpack the conflict between the Better Regulation agenda and the FCTC. We suggest evidential management strategies for governments developing tobacco control policies in this multilevel governance context.

Methods

Defining ‘evidence’

The comparative analysis methodology employed in this research required that ‘evidence’ was interpreted narrowly as formal written research sources, such as reports or journal articles. This restriction enabled a comparison of similar evidence in the two datasets: TTC citations and systematic review evidence. Other forms of evidence (eg, opinion, political statements, legal rulings and press coverage) cited in the four TTCs’ submissions were excluded.

Selecting and recording TTC evidence

Details (author, title, date and source) of each piece of evidence cited by TTCs in their submissions were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet and categorised under three main arguments made by TTCs: there is no evidence of the beneficial impact of standardised packaging on public health—standardised packaging ‘won't work’; standardised packaging will have negative unintended consequences (including economic impacts on businesses, growth in illicit trade in tobacco products, reduction in the price of cigarettes or contravention of existing trade and intellectual property rules); and the policy process was ‘flawed’. Evidence was also categorised as to whether it was promoted by TTCs as supporting their argument, or contested by them. Only evidence used by TTCs to promote their argument that standardised packaging ‘won't work’ was obtained and examined further.

Evidence from the systematic review

Details of the studies cited in the systematic review were recorded in Excel and were used for further analysis of their relevance and quality.

Criteria for assessing evidence

Three criteria, identified via a review of similar studies of the quality of evidence used to oppose tobacco regulation,24 38–42 were used to assess the policy relevance and quality of the evidence: subject matter, independence and peer-review (table 1). These criteria represent an objective and practical means for policymakers to assess the policy relevance and quality of large quantities of evidence cited in submissions to public consultations prior to considering their content.

Table 1.

Coding framework for classifying evidence

| Evidential criteria | Use in previous studies | Data coding framework | Coding categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Subject matter | What is the topic, argument, position or conclusion of the evidence?40–42 | What issue does the research address? | ▸ Standardised packaging of tobacco ▸ Tobacco packaging, eg, graphic health warnings ▸ Tobacco, not packaging ▸ Unrelated to tobacco |

| Quality | Independence | Who funded the evidence? Are authors affiliated to the tobacco industry?39–42 | Who funded the research? Has the author of the research any connection with the tobacco industry? |

▸ Tobacco industry-funded (statement included that the research was funded by the tobacco industry) ▸ Tobacco industry-linked (no statement that the research was funded by the tobacco industry, but evidence of other connection: eg, author or funder have prior links to the tobacco industry) ▸ Independent of the tobacco industry (statement included that the research was funded by a source independent of the tobacco industry) ▸ No apparent tobacco industry connection (no information provided about funding source and no evidence of prior connection with the tobacco industry) |

| Peer-review status |

Has the evidence been peer-reviewed? What is the impact factor of the journal and date of publication?39–42 |

Was the research published in peer-reviewed journal? If not, where was the research published? |

▸ Peer-reviewed journal ▸ Academic press volume ▸ Conference paper ▸ Government-commissioned research ▸ University research report ▸ Government internal research ▸ Charity research report ▸ Private company research report ▸ Unpublished |

The subject matter of the evidence speaks to its relevance to the policy issue.31 Similar work has coded policy position, argument, topic and conclusion.40–42 On independence, research indicates that connection of research with a financially vested interest group can produce results which favour the sponsor, casting doubt on the independence, and therefore quality, of the evidence.40 43 44 The tobacco industry's efforts to discredit the science on environmental tobacco smoke and bias evidence on the impacts of smoke-free legislation provide historical examples of this.22–25 45 On peer-review status, articles which appear in peer-reviewed journals have been shown to be of superior quality to other research outputs in terms of study design, reporting and interpretation.40 46 For example, peer-review enables studies to be assessed by experts who are knowledgeable in the subject area, provides strong incentives for authors to heed advice and improve articles and acts as a filter which aims to prevent poorly designed studies from being published. Some alternative publication routes also include external peer-review (eg, government-commissioned research, academic press volumes and conference papers); others rely on internal peer-review (eg, charity and university research reports); research funded and published by the tobacco industry tends not to be subject to an external peer-review process: “[T]he tobacco industry has had a long-standing strategy of funding research and disseminating it through their sponsored, non-peer-reviewed publications.”47 48

Evidential coding

Each piece of evidence was obtained via online searches (general search engines and the research database Scopus), with non-digital documents obtained from library sources. Researchers read abstracts, introductions, conclusions, funding statements and cover pages of all evidence documents, and searched documents for key terms (‘plain’, ‘pack*’, ‘standard*’, ‘tobacco’, ‘smok*’). Additional web searches were conducted (eg, the Legacy Library of tobacco industry documents and Scopus) to clarify the independence and peer-review status of evidence.

Analytical process

The researchers used a content analysis methodology to code and analyse the data. Each piece of evidence was accessed and coded by one researcher (JLH) using the criteria outlined in table 1. A second researcher (GJF) blind-coded a random sample of 20% of the data (n=21). This process achieved a 97% level of inter-coder reliability. Once all the data had been analysed, a third researcher (KAE-R) blind-coded 100% of the data. This process achieved a 94.7% level of inter-coder reliability. All disagreements were fully resolved between the coders.

Having quantified and coded the evidence, we compared the policy relevance (subject matter) and quality (independence and peer-review) of the industry evidence with that of the evidence supporting standardised packaging in the systematic review.32 We also examined the relationship between policy relevance and quality by comparing the quality of the industry's evidence on tobacco packaging with its evidence on other topics. Differences were compared using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test. The results were used to develop relevance-quality typologies of the TTC evidence. Evidence was classified as relevant if it focused on standardised packaging/tobacco packaging, and parallel if it focused on other tobacco issues/was unrelated to tobacco. Evidence was classified as featuring quality indicators if it was either independent, published in a peer-reviewed journal or both.

Results

Overview of evidence cited by the TTCs in their submissions

One hundred and forty-three unique pieces of formal written research evidence were referred to or included in the four TTCs’ submissions (22 referenced by more than one company; table 2). Of the 143 documents, TTCs promoted 131 as supporting their arguments and contested the methods, findings or accessibility of the remaining 12, all of which were included in the systematic review. Eighty-eight pieces of evidence were cited to support arguments that standardised packaging would not have beneficial impacts on public health; 36 were cited to argue that standardised packaging will have negative unintended consequences, half of which related to the illicit trade in tobacco; 19 were cited to argue that the policy process—particularly the impact assessment—was ‘flawed’. Seventy-seven pieces of evidence were used to promote the TTCs’ argument that standardised packaging ‘won't work’ and were therefore the subject of further analysis in this article.

Table 2.

Overview of formal written evidence cited by transnational tobacco corporations (TTCs) in their submissions to the UK standardised packaging consultation 2012

| Theme of evidence | Standardised packaging ‘won't work’: no evidence of impacts on smoking behaviour | Standardised packaging ‘will have negative unintended consequences’ |

The policy process was ‘flawed’ | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How cited by TTCs | Economic | Illicit | IP/Trade | Price | |||

| Promoted | 77* | 3 | 18 | 5 | 9 | 19 | 131 |

| Contested | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| – | 4 | 18 | 5 | 9 | – | – | |

| Total | 88 | 36 | 19 | 143 | |||

*The evidence examined further in this article. Bold text indicates totals.

Among these 77 documents, TTCs did not cite any research showing that the tobacco industry has extensively studied and holds considerable evidence attesting to the impact of packaging on smoking behaviour.34–37 Instead, they cited industry-funded research which critiqued the systematic review articles, the impact assessment and the consultation document. And they cited a body of independent research into the drivers of youth smoking which, while published in peer-reviewed health and psychology journals with no apparent connection to the tobacco industry, did not explicitly address the role of packaging in youth uptake or prevalence.

Comparison of the TTC and systematic review evidence on the impact of standardised packaging on smoking behaviour

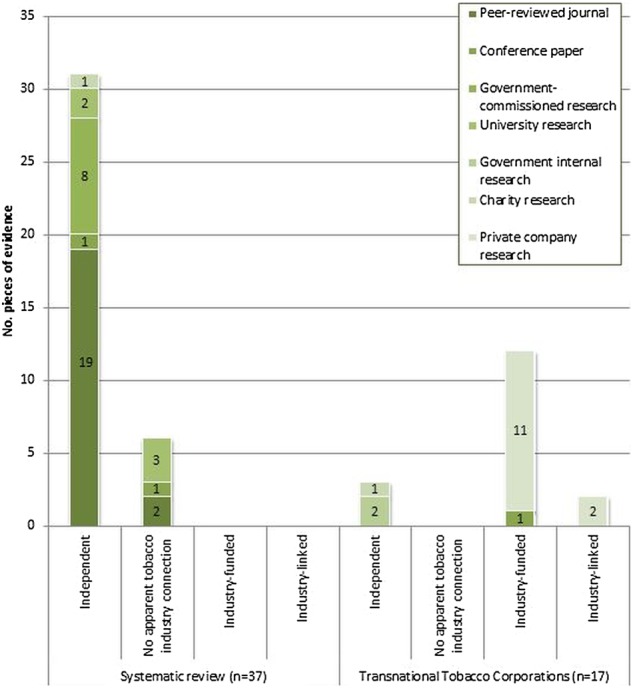

There are marked differences between the relevance and quality of the TTC and systematic review evidence (table 3 and figure 1). Only 17/77 (22%) pieces of evidence promoted by TTCs addressed standardised packaging directly; the majority of these were industry-funded/linked (14/17, 82%) and none were published in a peer-reviewed journal (0/17, 0%). The remaining 60 pieces of evidence (78% of the total, comprising the majority of the evidence the industry cites) did not address standardised packaging. In contrast, 37/37 (100%) pieces of evidence included in the systematic review focused on standardised packaging, none (0/37, 0%) had a connection with the tobacco industry, and 21/37 (57%) pieces of evidence were published in a peer-reviewed journal. A comparison of TTCs’ evidence on standardised packaging (n=17) with the systematic review evidence on standardised packaging (n=37), using Fisher's exact test, showed that the former was of significantly lower quality in terms of independence (p<0.0001) and peer-review status (p<0.0001).

Table 3.

Quality and relevance of transnational tobacco corporation (TTC) and systematic review evidence

| Relevance: subject matter |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardised packaging |

Other (TTC evidence only) |

||||

| Quality | Systematic review evidence (n=37) | TTC evidence (n=17) | Tobacco packaging (n=9) | Tobacco, not packaging (n=45) | Unrelated to tobacco (n=6) |

| Independence | |||||

| Industry-funded | 0 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Industry-linked | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Independent | 31 | 3 | 6 | 37 | 5 |

| No apparent connection to the tobacco industry | 6 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Publication route | |||||

| Peer-reviewed journal | 21 | 0 | 1 | 26 | 4 |

| Academic press | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Conference paper | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Government-commission | 8 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| University research | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Government internal research | 0 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 0 |

| Charity research | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Private company research | 0 | 13 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Unpublished | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Bold text highlights evidence relating to standardised packaging.

Figure 1.

Comparison of quality (independence and publication route) of the systematic review and transnational tobacco corporation evidence directly addressing standardised packaging of tobacco products.

Relationships between subject matter, independence and peer-review within the TTC evidence

A low proportion of TTCs’ evidence relating to standardised packaging was independent or peer-reviewed (figure 1 and table 3). When evidence on tobacco packaging was added to the standardised packaging evidence, the same pattern was found: 9/26 (35%) Pieces of evidence were independent (independent/no apparent tobacco industry connection); 1/26 (4%) pieces of evidence was published in a peer-reviewed journal (table 4) However, a greater proportion of the 51 pieces of evidence TTCs cited on parallel topics (including non-packaging drivers of youth and adult smoking behaviour, and drivers of youth behaviour in general) were independent (47/51, 92% independent/no apparent connection) and peer-reviewed (30/51, 59% published in a peer-reviewed journal). These differences are statistically significant (p<0.0001, table 4). We also found a clear relationship between the two indicators of quality—independence and peer-review—in the TTCs’ evidence: industry-funded/linked studies cited by TTCs were significantly less likely to be published in a peer-reviewed journal (3/21, 14%) than independent/no apparent connection studies they cited (28/56, 50%; p=0.0045, table 5).

Table 4.

Relationship between the policy relevance and two indicators of quality in the transnational tobacco corporations' evidence (n=77), number and per cent in parenthesis

| Quality indicators | Policy relevance: subject matter |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant: standardised packaging/tobacco packaging (n=26) | Parallel: tobacco not packaging/unrelated to tobacco (n=51) | Fisher's p value | |

| Independent of/no apparent tobacco industry connection | 9/26 (35%) | 47/51 (92%) | <0.0001 |

| Published in a peer-reviewed journal | 1/26 (4%) | 30/51 (59%) | <0.0001 |

Table 5.

Relationship between two indicators of quality in the transnational tobacco corporation evidence, number and per cent in parenthesis

| Peer-review status | Independent of/no apparent tobacco industry connection (n=56) | Connected with the tobacco industry (n=21) | Fisher's p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Published in a peer-reviewed journal | 28/56 (50%) | 3/21 (14%) | p=0.0045 |

TTCs’ evidence was classified into four typologies (table 6): relevant/quality indicators, relevant/no quality indicators, parallel/quality indicators and parallel/no quality indicators. While 100% of the systematic review evidence was relevant and featured at least one of the two quality indicators, only 12% of evidence cited by TTCs in their submissions qualified for this category.

Table 6.

Distribution of transnational tobacco corporation evidence across typologies

| Quality | Quality indicators | No quality indicators | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevance | Either independent, peer-reviewed or both | Neither independent nor peer-reviewed | |

| Relevant | Standardised packaging and other tobacco packaging | 12% (100% systematic review evidence) | 22% |

| Parallel | Tobacco, not packaging and unrelated to tobacco | 65% | 1% |

Bold text refers to TTC evidence.

Discussion

Four main findings are apparent. TTCs cited a large volume of evidence in their submissions to the UK standardised packaging consultation. Seventy-seven pieces of evidence were used to support the claim that standardised packaging ‘won't work’ yet just 17 of these actually focused on standardised packaging, 14 of which had a connection with the industry. The quality of the TTCs' evidence on standardised packaging is significantly lower, as judged by independence and peer-review, than that included in the systematic review. Overall, the evidence cited by TTCs is shown, with few exceptions, to fit one of two typologies—either relevant/no quality indicators or parallel/quality indicators (table 6). Furthermore, we show that evidence funded by or otherwise linked to industry is significantly less likely to be peer-reviewed than non-industry-connected evidence.

These findings raise a number of concerns regarding the potential impact of Better Regulation on tobacco control policymaking in jurisdictions around the world. First, our findings highlight how Better Regulation, with its requirement for public consultations and impact assessments, imposes costs on government departments in the earliest stage of policy development. Just as TTCs habitually launch legal challenges in the postdecision phase of policy-making,49 so too can they use their resource advantage to exploit Better Regulation processes by commissioning new research and submitting extensive and complex responses in the predecision phase of the policy process, effectively frontloading their opposition. The combination of a requirement for due diligence and the volume and nature of responses may have contributed to the 11-month delay in the publication of the Department of Health's consultation report.

Second, Better Regulation's requirement that policymakers consider alternative policy options, with its underlying intention of preventing unnecessary regulation, imposes additional upfront costs on governments. In the case of standardised packaging, this requirement encouraged the extensive citation of evidence beyond the focus of the policy proposal. This may partly explain why nearly two-thirds of the evidence TTCs cited to claim that standardised packaging ‘won't work’ addressed non-packaging drivers of youth and adult smoking: studies which do not consider standardised packaging in their methodology or analysis. A second possible explanation is that the level of independence and peer-review of this parallel evidence is significantly higher than that of the evidence they cite on tobacco packaging, and its inclusion may therefore have been intended to add legitimacy to the TTCs' arguments.

Third, the absence of guidelines requiring a declaration of any conflict of interest between corporations and the evidence they cite enable tobacco industry-funded/linked work to be cited by TTCs in such a way that any link is undeclared, implying independence. For example, BAT, IT and PM all cited tobacco industry-funded/linked evidence in their submissions without explicitly acknowledging their connection with it.27 29 30 This speaks to a lack of transparency in the policy process regarding the provenance of evidence submitted by corporate interests.

Fourth, the lack of clarity regarding whether or how civil servants assess the policy relevance and quality of evidence is reflected by an equivalent lack of clarity regarding how governments handle the absence of evidence. We have identified a clear omission in the TTCs’ submissions of evidence, which TTCs are known to have,34–37 on the importance of packaging in the marketing of their products.

Taken collectively, evidence present in and absent from TTCs’ submissions highlights an important transparency deficit within Better Regulation processes. This deficit obscures the view of policymakers, potentially preventing them from identifying and taking account of the judicious selection and exclusion of evidence by corporate actors with vested interests in policy outcomes. Because Better Regulation requires evidence-based impact assessments and invites evidence-based submissions to public consultations, the potential exists for corporations to exert undue and unnoticed influence on the policy process. Recently leaked industry documents outlining Philip Morris International's strategy for ensuring standardised packaging is not adopted in the UK indicate that the TTCs had identified and planned to use the opportunities presented by Better Regulation in making its arguments.50 51

Considering the statutory requirement imposed by Article 5.3 of the FCTC to ‘protect’ tobacco control policies ‘from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry’,21 it would be advisable for the 177 states which are party to the Convention to implement and publish clear guidelines on how TTC submissions to public consultations, and evidence cited within, should be managed by policymakers. Two steps could be taken by governments to achieve this. First, conflict of interest declarations regarding evidence cited could be made a mandatory element of public consultations. Second, policymakers could adopt a similar methodology to that used in this research. Adopting a process of classifying evidence for subject matter, independence and peer-review status may help policymakers to systematically prioritise good quality and policy-focused evidence, and to flag evidence about which they need to be more sceptical, such as that which is not policy-focused, not independent or not peer-reviewed.

These recommendations have relevance across government departments in all states which are signatories to the FCTC. It would also be appropriate to explore applying this critical perspective to the development of non-tobacco public health regulation—for example, of the alcohol and food industries—where corporate interests also seek to influence policy being developed for the public good.52 53

The strength of the findings is limited by the use of indicators of quality, rather than a validated quality-assessment framework, to assess the evidence. Peer-review status and independence from the tobacco industry are used as proxy indicators of quality. While we acknowledge that peer-review standards can and do vary in practice,54–57 our rationale for choosing these proxies is based on our interest in addressing the challenges policymakers face in assessing large volumes of evidence. Unlike quality assessment tools, the criteria we have selected do not require scientific expertise or lengthy data extraction processes and can be used systematically in the policy environment to assess the relevance and quality of evidence cited by consultation respondents. Where the need is identified, more in-depth analysis of study design, data and methods38–40 can be undertaken to review key pieces of evidence.

What has been learned from the UK Government's 2013 decision to postpone any decision on standardised packaging until further evidence is available is that Better Regulation ensures that evidence occupies a critical instrumental role in policymaking. Thus, how government departments handle and interpret evidence in the development of public health policy, and what evidential relevance and quality thresholds are set for policy progression in the context of Better Regulation, are of vital importance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Michelle Sims for her assistance in reviewing the statistical content of this paper. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Contributors: JLH, GJF and ABG conceived the idea for this study; ABG conceived the idea for the statistical analysis. JLH was responsible for data gathering, coding, analysis and write-up. GJF and KAE-R were responsible for secondary coding. JLH, GJF, KAE-R, SU and ABG were involved in discussion of findings and commented on and edited drafts of the article.

Funding: The work was supported by Cancer Research UK (Grant no. C38058/A15664).

Competing interests: ABG is a member (unpaid) of the Council of Action on Smoking and Health, and was a member of the WHO Expert Committee convened to develop recommendations on how to address tobacco industry interference with tobacco control policy. JLH, GJF, KAE-R, SU and ABG are part of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (Grant no. MR/K023195/1), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. KAE-R is supported by Cancer Research UK (Grant no. C48078/A16481). GJF, SU and ABG are supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant no. RO1CA160695).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Australian Government. 2011. Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011: an act to discourage the use of tobacco products, and for related purposes.

- 2.UK Government Healthy lives, healthy people: a tobacco control plan for England. London: HM Government, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health Consultation on standardised packaging of tobacco products. London: Williams Lea, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health Tobacco Programme Consultation on standardised packaging of tobacco products: summary report. London: UK Government, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health ‘Consultation stage impact assessment questions’. London: UK Government, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsbury B, Krisch N, Stewart RB. The emergence of global administrative law. Law Contem Probl 2005;68:15–61 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hahn RW, Litan RE. Counting regulatory benefits and costs: lessons for the US and Europe. J Int Econ Law 2005;8:473–508 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibbons M, Parker D. Impact assessments and better regulation: the role of the UK's regulatory policy committee. Public Money Manage 2012;32:257–64 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiener JB. Better Regulation in Europe. Curr Legal Probl 2006;59:447–518 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radaelli CM. Rationality, Power, Management and Symbols: Four Images of Regulatory Impact Assessment. Scand Polit :164–88 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fooks G, Gilmore AB. International trade law, plain packaging and tobacco industry political activity: the trans-pacific partnership. Tob Control 2013. Published Online First 20 Jun 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith K, Fooks G, Collin J, et al. Is the increasing policy use of Impact Assessment in Europe likely to undermine efforts to achieve healthy public policy? J Epidemiol Community Health 2010;64:478–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabinet Office UK Government Consultation principles. London: UK Government; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radaelli C. Better regulation in Europe: between public management and regulatory reform. Public Adm 2009;87:639–54 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yackee JW, Yackee SW. A bias towards business? Assessing interest group influence on the US bureaucracy. J Polit 2006;68:128–39 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obradovic D, Alonso Vizcaino JM. Good governance requirements concerning the participation of interest groups in EU consultations. Common Mark Law Rev 2006;43:1049–85 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radaelli CM. Regulating rule-making via impact assessment. Governance-Int J Policy Adm I 2010;23:89–108 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies HN, Nutley SM. Evidence-based policy and practice: moving from rhetoric to reality. Interdisciplinary Evidence-Based Policies and Inidcator Systems Conference; July 2001. CEM Centre University of Durham, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenhalgh T, Russell J. Evidence-based policy-making: a critique. Perspect Biol Med 2009;52:304–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs C. The evolution and development of regulatory impact assessment in the UK. In: Kirkpatrick C, Parker D. eds. Regulatory Impact Assessment: towards better regulation? Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2007:106–31 [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organisation Framework convention on tobacco control. Switzerland: WHO Library, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bero LA. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Public Health Rep 2005;120:200–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drope J, Chapman S. Tobacco industry efforts at discrediting scientific knowledge of environmental tobacco smoke: A review of internal industry documents. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:588–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes DE, Bero LA. Industry-funded research and conflict of interest: an analysis of research sponsored by the tobacco industry through the center for indoor air research. J Health Polit Policy Law 1996;21:515–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong MK, Bero LA. Tobacco industry sponsorship of a book and conflict of interest. Addiction 2006;101:1202–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith K, Gilmore AB, Fooks G, et al. Tobacco industry attempts to undermine article 5.3 and the "good governance" trap. Tob Control 2009;18:509–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imperial Tobacco. 2012. Bad for business; bad for consumers; good for criminals: standardised packaging is unjustified, anti competitive and anti business, a reponse to the UK Department of Health consultation on standardised packaging.

- 28.Japan Tobacco International Ltd. 2012. Response to the Department of Health's consultation on the standardised packaging of tobacco products.

- 29.Philip Morris Limited. 2012. Standardised tobacco packaging will harm public health and cost UK taxpayers billions: a response to the Department of Health's Consultation on standardised packaging.

- 30.British American Tobacco. 2012. UK Standardised Packaging Consultation: Response of British American Tobacco UK Ltd.

- 31.Boaz A, Ashby D. Fit for purpose? Assessing research quality for evidence based policy and practice. ESRC Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice: Queen Mary, University of London; 2003

- 32.Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L, et al. A plain tobacco packaging: a systematic review. Stirling: Public Health Research Consortium, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman B, Chapman S, Rimmer M. The case for the plain packaging of tobacco products. Addiction 2008; 103:580–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter SM. From legitimate consumers to public relations pawns: the tobacco industry and young Australians. Tob Control 2003;12(Suppl 3):iii71–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krugman DM, Quinn WH, Sung Y, et al. Understanding the role of cigarette promotion and youth smoking in a changing marketing environment. J Health Commun 2005;10:261–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoek J, Gendall P, Maubach N, et al. Strong public support for plain packaging of tobacco products. Aust N Z J Public Health 2012;36:405–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry C. The tobacco industry and underage smoking: tobacco industry documents from the Minnesota litigation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:935–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegel M. ‘Economic impact of 100% smoke-free restaurant ordinances’. In: Program PMR. Smoking and restaurants: a guide for policy makers. Berkeley, CA: University of California/UCSF, 1992;26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scollo M, Lal A, Hyland A, et al. ‘Review of the quality of studies on the economic effects of smoke-free policies on the hospitality industry’. Tob Control 2003;12:13.– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnes D, Bero LA. Scientific quality of original research articles on evironmental tobacco smoke. Tob Control 1997;12:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bero L, Montini T, Bryan-Jones K, et al. Science in regulatory policy making: case studies in the development of workplace smoking restrictions. Tob Control 2001;10:329–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montini T, Mangurian C, Bero LA. Assessing the evidence submitted in the development of a workplace smoking regulation: the case of Maryland. Public Health Rep 2002;117:291–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hillman A, Eisenberg JM, Pauly MV, et al. Avoiding bias in the conduct and reporting of cost-effectiveness research sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1362–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller PG. Research independence matters for practitioners and researchers in the addictions. J Groups Addict Recovery 2008; 3:47–59 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neilsen K, Glantz SA. A tobacco industry study of airline cabin air quality: dropping inconvenient findings. Tob Control 2004;13:i20–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albert M, Laberge S, McGuire W. Criteria for assessing quality in academic research: the views of biomedical scientists, clinical scientists and social scientists. Higher Educ 2012;64:661–76 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bero L. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Late lessons from early mornings: science, precaution and innovation. Luxembourg: European Environment Agency, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garne D, Watson M, Chapman S, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke research published in the journal Indoor and Built Environment and associations with the tobacco industry. Lancet; 365:804–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jarman H. Attack on Australia: tobacco industry challenges to plain packaging. J Public Health Policy 2013;34:375–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Philip Morris International. 2012. UK Corporate Affairs Update. February.

- 51.Philip Morris International. 2012. UK Corporate Affairs Update. March.

- 52.Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C, et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet 2013; 381:670–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jernigan DH. Global alcohol producers, science, and policy: the case of the international center for alcohol policies. Am J Public Health 2012;102:80–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Peer review in scientific publications. London: Stationery Office Ltd., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson JL, Srinivasan M, Rea J, et al. The validity of peer review in a general medicine journal. PLoS ONE 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lipworth WL, Kerridge IH, Carter SM, et al. Journal peer review in context: a qualitative study of the social and subjective dimensions of manuscript review in biomedical publishing. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1056–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jefferson T, Rudin M, Folse SB, et al. Editorial peer review for improving the quality of reports of biomedical studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;72:1056–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.