Abstract

Objective

To examine the seasonal distribution of tendon ruptures in a large cohort of patients from Vancouver, Canada.

Design

Retrospective chart review.

Setting

Acute Achilles tendon rupture cases that occurred from 1987 to 2010 at an academic hospital in Vancouver, Canada. Information was extracted from an orthopaedic database.

Participants

No direct contact was made with the participants. The following information was extracted from the OrthoTrauma database: age, sex, date of injury and season (winter, spring, summer and autumn), date of surgery if date of injury was unknown and type of injury (sport related or non-sport related/unspecified). Only acute Achilles tendon rupture cases were included; chronic cases were excluded along with those that were conservatively managed.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was to determine the seasonal pattern of Achilles tendon rupture. Secondary outcomes, such as differences in gender and mechanism of sport (non-sport vs sport related), were also assessed.

Results

There were 543 cases in total; 83% of the cases were men (average age 39.3) and 17% were women (average age 37.3). In total, 76% of cases were specified as sport related. The distribution of injuries varied significantly across seasons (χ2, p<0.05), with significantly more cases occurring in spring. The increase in the number of cases in spring was due to sport-related injuries, whereas non-sport-related cases were distributed evenly throughout the year.

Conclusions

The seasonality of sport-related Achilles tendon ruptures should be considered when developing preventive strategies and when timing their delivery.

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, ORTHOPAEDIC & TRAUMA SURGERY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study included a large cohort of patients who had Achilles tendon repair.

Retrospective study: prevalence or incidence rates were not reported as the study was limited to patients treated at a single institution.

The injury rates cannot be specifically related to the sport-specific playing season as the ruptures occurred as a result of various sporting activities.

Introduction

Acute Achilles tendon rupture is a common injury, with the reported incidence ranging from 6 to 37 ruptures/100 000 people.1–3 The incidence has been noted to be increasing over time, a trend which has been attributed to increasing participation in recreational physical activity.4 Achilles tendon rupture itself results in major functional deficits which persist even 2 years after rupture, regardless of whether the injury is managed surgically or conservatively.5 Thirty-two per cent of professional football players who sustained an Achilles tendon rupture did not return to league play.6 The prevention of Achilles tendon injuries has been identified as a valid clinical goal7 but there is at present limited evidence on which to base recommendations or preventive strategies.

A common feature of successful injury preventative programmes is that they address relevant risk factors.8 Previously identified factors which are associated with Achilles tendon rupture include a previous rupture (ipsilateral or contralateral),9 a family history of tendon rupture,10 genetic variants in genes related to extracellular matrix metabolism,11 male sex12 and participation in sporting activity (particularly high-load activities).13 Reported medical risk factors include dyslipidaemia,14 hyperparathyroidism15 and the use of fluoroquinolones and corticosteroids.16 Associated clinical features which have been suggested as risk factors include a history of Achilles tendinopathy,17 calf muscle inflexibility or weakness,18 training errors and abnormal foot type.19

A significant seasonal risk for Achilles tendon ruptures has not previously been reported. This is in contrast to other conditions; for example, there is an increased incidence of hamstring injuries at the start of the football season.20 We conducted a systematic literature search for articles which examined the potential seasonal nature of Achilles tendon ruptures. The following search terms were used: ‘Achilles tendon’ and ‘season or seasonal or seasonality’ for all dates available up to November 2012). Medline Ovid, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and EMBASE were searched; the obtained abstracts were reviewed to determine whether specific information on the seasonality of Achilles tendon injuries was reported. Three relevant studies were found, and all reported that there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of Achilles tendon rupture by season, although two reported on the existence of non-significant trends.2 3 6

Therefore, the objective of this retrospective review was to document the seasonal pattern of Achilles tendon ruptures repair at an academic teaching hospital in Vancouver, Canada.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective review of an orthopaedic trauma surgical database which is maintained at the Vancouver General Hospital, Division of Orthopaedic Trauma, Vancouver, Canada (the OrthoTrauma database). Given that we did not intend to report incidence values for this injury (which have been extensively reported previously), we reasoned that limiting our study to a single institution would (1) yield enough cases to examine the seasonal distribution of cases and (2) result in a more homogeneous dataset.

The OrthoTrauma database is a repository of prospectively collected data that generates a case for every individual who has been treated for orthopaedic traumatic injuries at our institution, including patients admitted for day surgery or overnight stay surgery. Each week, the database administrative staff, in conjunction with the surgeons, validate admission–discharge–transfer data uploaded from the hospital's information system and add clinical information related to patient, injury, treatment, complications and discharge disposition. The database was searched by a research coordinator who extracted all cases which had been coded as Achilles tendon repairs. This coding has been consistently used throughout the years of the database searched (1987–2010). We acknowledge that this case definition does introduce a potential bias in that it does not include information on patients who had been conservatively managed, but we rationalise that it would be highly unlikely for the choice of management (conservative vs surgical) to be influenced by season. In addition, conservatively managed Achilles tendon ruptures represent only a small minority of cases at our institution—typically elderly, less active individuals presenting a high risk for surgery. Also, there were no major shifts in the management strategy (conservative vs surgical management) during the period over which the database was searched (1987–2010). The following information was extracted—date of injury, age, sex and mechanism of injury (sport related vs non-sport related or not reported). The mechanism of injury had previously been extracted from the medical history and entered into the database by a research assistant. Injuries were categorised by season based on locally used meteorological definitions which are based on the equinoxes and solstices (winter, 21 December–20 March; spring, 21 March–20 June; summer, 21 June–20 September; and fall, 21 September–20 December).

Statistical analyses were conducted using an online χ2 calculator (http://www.graphpad.com). A two-tailed χ2 test was used to examine the null hypothesis that ruptures were equally distributed in all four seasons, for the sport-related cases and for other cases (p<0.05 considered significant for each test).

Results

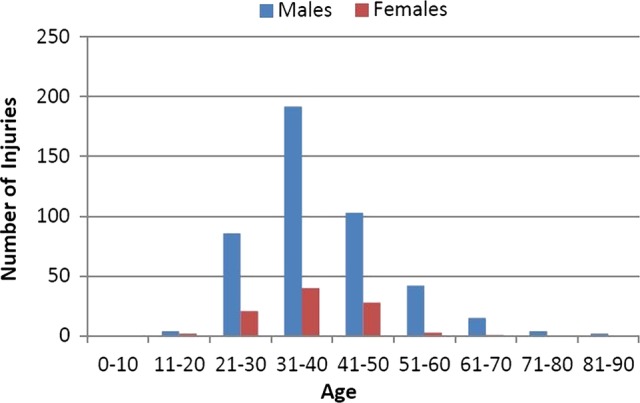

A total of 543 Achilles tendon ruptures occurring between 1 January 1987 and 31 December 2010 were identified. The male : female ratio was 4.7 : 1 (448 males and 95 females). The mean age was 38.8 years (range 16–84). The peak age range was the same for men and women, 31–40, and the average age of men and women was similar (39.3 and 37.3, respectively; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Achilles tendon rupture cases in different age ranges recorded at Vancouver General Hospital between 1 January 1987 and 31 December 2010. A comparison is shown of the number of injuries in males and females, demonstrating a similar peak in the fourth decade for both genders.

The majority of cases (413) were specified as sport related. There were no differences in the average age or sex distribution between the sport-related or other cases. The mean age (SD) of sport-related cases versus other cases was 38.7 (10.1) vs 39.4 (11.4). The proportion of men among the sport-related cases versus other cases was 0.83 vs 0.85.

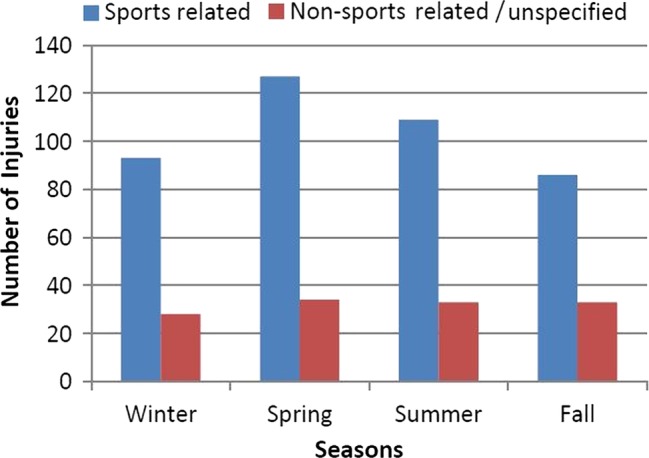

There was a clear seasonal pattern (p=0.03, figure 2), with the highest number of cases occurring in spring (n=161) and the lowest in winter (n=121) and fall (n=119). When the seasonal pattern was examined specifically in sport-related cases, the statistical significance of the χ2 test increased (p=0.022). By contrast, the non-sport-related/unspecified cases did not display any trend towards a seasonal effect.

Figure 2.

The seasonal pattern of Achilles tendon ruptures. Sport-related and non-sport-related/unspecified injuries are shown separately—the seasonal pattern is statistically significant (p<0.05) only for the sport-related cases.

Discussion

We identified an increased number of Achilles tendon rupture cases in spring compared with other seasons. This effect was only present for the subset of cases that were noted as sport related in the medical history. Overall, there were 33% more cases in spring than in winter, implying that the transition into spring sporting activity is a period of increased risk of Achilles tendon ruptures.

Several previous studies have examined the seasonal distribution of Achilles or other activity-related injuries. Parekh et al6 studied Achilles tendon ruptures in a retrospective review of National Football League injury registries (USA). In contrast to the current study, they found that while the majority of injuries (65%) occurred during regular seasonal games, compared with the preseason (35%), the injuries which occurred during the playing season were equally distributed across all months. Maffulli et al2 reported on all Achilles tendon ruptures reported over a 15-year period in a Scottish national registry, and noted a reduced number of cases in the autumn; however, this finding was not statistically significant. In line with our current findings, Suchak et al3 noted that over a 5-year period in Edmonton, Canada, the highest number of cases appeared to occur in spring; however, the effect did not reach statistical significance. In the current study, we found a marked and statistically significant seasonal variation, with the highest number of cases occurring in spring.

The gender difference in the rates of Achilles tendon rupture is a well-known but still not entirely explained phenomenon.21 The incidence of lower extremity tendinopathies (Achilles, patellar) is higher in men,22 23 but the incidence of upper extremity tendinopathies, such as lateral epicondylalgia and rotator cuff tendinopathy, are equal in both genders.24 25 A recent study found that the administration of oestrogen in postmenopausal women enhanced the synthesis of type I collagen in the tendon following exercise.26 Thus, the availability of oestrogen appears to potentiate the tendon's ability to adapt or repair following damaging loading. However, for a given tendinopathy, other risk factors (both systemic and local) may mask or outweigh the effects of oestrogen.

The study has several limitations. It was a retrospective study limited to a single institution; thus, we are not able to report on prevalence or incidence rates. In our database, if a case was not specified as sport related, it may have been due to an alternate mechanism of injury or it may have been inadvertently left blank. However, we believe that the majority of unspecified cases were, in fact, non-sport related, because the percentage of cases which were unspecified in our database (24%) is similar to the rate of non-sport related injuries in previous reports (eg, 26%9). We did not have enough cases to separately analyse the seasonality of different sports, genders or age ranges, so it is not clear how these factors may interact. However, the average age and the gender ratio of the sport-related and non-sport-related cases were the same. Another limitation is that the ruptures occurred as a result of various sporting activities; thus, it was not possible to relate the injury rates to the sport-specific playing season. It is also not clear to what extent the findings of this study would be generalisable to other countries or climates; it is possible that seasonal trends in Achilles injuries could be particularly pronounced in Vancouver, Canada, a city with a temperate climate and which has a long history of highly popular spring running events (eg, Vancouver Sun Run, 1985 to present).

We conclude that seasonality influences the risk of Achilles tendon ruptures. Furthermore, studies that are local and/or sport specific will need to be conducted for developing preventative strategies for this injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All the authors would like to thank Raman Johal for assistance in searching the database and Rick White for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Contributors: PG conceived the original study design, and AS and NG contributed to the development of the study design, and conducted the statistical analysis. NG reviewed the database, extracted and summarised the data. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. AS and PG are responsible for the overall content as guarantors.

Funding: Alex Scott was supported by a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Clinical Scholar award.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia clinical research ethics board, and institutional approval was obtained from the Vancouver Coastal Health and Research Institute.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Houshian S, Tscherning T, Riegels-Nielsen P. The epidemiology of Achilles tendon rupture in a Danish county. Injury 1998;29:651–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maffulli N, Waterston SW, Squair J, et al. Changing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Scotland: a 15-year study. Clin J Sport Med 1999;9:157–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suchak AA, Bostick G, Reid D, et al. The incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in Edmonton, Canada. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:932–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nillius SA, Nilsson BE, Westlin NE. The incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1976;47:118–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsson N, Nilsson-Helander K, Karlsson J, et al. Major functional deficits persist 2 years after acute Achilles tendon rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:1385–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parekh SG, Wray WH, III, Brimmo O, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of Achilles tendon ruptures in the National Football League. Foot Ankle Spec 2009;2:283–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochcongar P, Bryand F, Bucher D, et al. French football epidemiological study for soccer injuries. Sci Sports 2004;19:63–8 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahr R, Krosshaug T. Understanding injury mechanisms: a key component of preventing injuries in sport. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:324–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aroen A, Helgo D, Granlund OG, et al. Contralateral tendon rupture risk is increased in individuals with a previous Achilles tendon rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2004;14:30–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraemer R, Wuerfel W, Lorenzen J, et al. Analysis of hereditary and medical risk factors in Achilles tendinopathy and Achilles tendon ruptures: a matched pair analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132:847–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins M, Raleigh SM. Genetic risk factors for musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries. Med Sport Sci 2009;54:136–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levi N. The incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Copenhagen. Injury 1997;28:311–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kujala UM, Sarna S, Kaprio J. Cumulative incidence of Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15:133–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathiak G, Wening JV, Mathiak M, et al. Serum cholesterol is elevated in patients with Achilles tendon ruptures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1999;119:280–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JH, Kim SB, Shin HS, et al. Spontaneous and serial rupture of both Achilles tendons associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism in a patient receiving long-term hemodialysis. Int Urol Nephrol 2013;45:587–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wise BL, Peloquin C, Choi H, et al. Impact of age, sex, obesity, and steroid use on quinolone-associated tendon disorders. Am J Med 2012;125:1228 e23–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahlstrom M, Bjornstig U, Lorentzon R. Acute Achilles tendon rupture in badminton players. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:467–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols AW. Achilles tendinitis in running athletes. J Am Board Fam Pract 1989;2:196–203 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smart GW, Taunton JE, Clement DB. Achilles tendon disorders in runners—a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1980;12:231–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen J, Thorborg K, Nielsen MB, et al. Acute hamstring injuries in Danish elite football: a 12-month prospective registration study among 374 players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:588–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjaer M, Hansen M. The mystery of female connective tissue. J Appl Physiol 2008;105:1026–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lian OB, Engebretsen L, Bahr R. Prevalence of jumper's knee among elite athletes from different sports: a cross-sectional study. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:561–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Jonge S, van den Berg C, de Vos RJ, et al. Incidence of midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the general population. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1026–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruchow HW, Pelletier D. An epidemiologic study of tennis elbow. Incidence, recurrence, and effectiveness of prevention strategies. Am J Sports Med 1979;7:234–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechardt M, Shiri R, Karppinen J, et al. Lifestyle and metabolic factors in relation to shoulder pain and rotator cuff tendinitis: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pingel J, Langberg H, Skovgard D, et al. Effects of transdermal estrogen on collagen turnover at rest and in response to exercise in postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol 2012;113:1040–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.