Abstract

Quantitative ultrasound (QUS) traits are correlated with bone mineral density (BMD), but predict risk for future fracture independent of BMD. Only a few studies, however, have sought to identify specific genes influencing calcaneal QUS measures. The aim of this study was to conduct a genome-wide linkage scan to identify quantitative trait loci (QTL) influencing normal variation in QUS traits. QUS measures were collected from a total of 719 individuals (336 males and 383 females) from the Fels Longitudinal Study who have been genotyped and have at least one set of QUS measurements. Participants ranged in age from 18.0 to 96.6 years and were distributed across 110 nuclear and extended families. Using the Sahara ® bone sonometer, broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA), speed of sound (SOS) and stiffness index (QUI) were collected from the right heel. Variance components based linkage analysis was performed on the three traits using 400 polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) markers spaced approximately 10 cM apart across the autosomes to identify QTL influencing the QUS traits. Age, sex, and other significant covariates were simultaneously adjusted. Heritability estimates (h2) for the QUS traits ranged from 0.42 to 0.57. Significant evidence for a QTL influencing BUA was found on chromosome 11p15 near marker D11S902 (LOD = 3.11). Our results provide additional evidence for a QTL on chromosome 11p that harbors a potential candidate gene(s) related to BUA and bone metabolism.

Keywords: Genetic linkage, quantitative ultrasound, calcaneus, family studies, bone

Introduction

Low bone mass and reduced bone strength is a key determinant of osteoporosis, a complex skeletal disease of aging influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Genetic factors account for up to 80% of the variation in areal bone mineral density (BMD), which is typically assessed using dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (1-4). Several genome-wide linkage studies (2-4) and, more recently, genome-wide association investigations examining BMD and fracture risk (5-9) have been published. While some chromosomal loci or genes have been replicated (e.g., osteoprotegerin and lipoprotein-receptor-related protein (LRP5) gene), overall few genetic studies for osteoporosis risk or BMD have been replicated even in genome-wide association studies (5, 8, 9).

Even though areal BMD is known to be the best predictor of osteoporosis and related fracture risk, other measures of bone strength, such as quantitative ultrasound (QUS), are also clinically important in predicting future osteoporosis or fracture risk (10-12). Calcaneal QUS measures are closely correlated with areal BMD, but not completely (10, 11). Further, evidence suggests that QUS measures are under significant genetic control (13-15). Heritability (h2) studies involving twins and extended families report that various QUS parameters of the calcaneus are under significant genetic control (h2 ranges from 45% to 74%) (13-15). Several chromosomal regions have been linked to broadband ultrasound attenuation (BUA) or speed of sound (SOS) including regions of chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 12 and 17 with suggestive or strong evidence for linkage (7, 13, 14). Some of these QTL (e.g., 5p) appear to share a number of plausible positional candidate gene loci with areal BMD as well (2). In this study, we conducted an autosome-wide linkage scan for QUS measures of the calcaneus to identify the regions or loci (quantitative trait loci, QTL) of the genome linked to the variation in QUS measures obtained from 719 men and women from nuclear and extended families participating in the Fels Longitudinal Study.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This study is based on adult participants of the Fels Longitudinal Study. The Fels Longitudinal Study began in 1929, and is the one of the longest running studies of human growth, development, and body composition over the lifespan (16). From its beginning Fels Longitudinal Study participants have not been selected based on health status or any other chronic disease related traits including osteoporosis. Participants in the Fels Longitudinal Study represent approximately 200 families, ranging in size from small nuclear families to large, four generation, extended families. A total of 719 European American adults (336 men and 383 women) age 18 years and over were included in this genome-wide linkage study. Participants were included in this analysis if they had at least one set of calcaneal QUS measurements and whole-genome short tandem repeat (STR) marker data. The Wright State University Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects Research approved the informed consent and research protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. There are a total of 3,138 relative pairings that exist among the 719 participants including 858 pairings for the first degree relationships (e.g. parent-offspring) and 605 relative pairings for the second degree relationships (e.g., grandparent-grandchild). This subset of participants belongs to 110 families with a mean family size of 5.

Quantitative Ultrasound

BUA (dB/MHz), SOS (m/s) and quantitative ultrasound index (QUI), a combined index of BUA and SOS were measured on the right calcaneous using the Sahara ® bone sonometer (Hologic, Inc., Waltham, MA). Duplicate measurements of BUA and SOS were performed and the average value of these duplicates was used. Quality control was performed daily following the manufacturer's protocols. The coefficients of variation (CV) for duplicated measures of BUA and SOS were 7.51% and 0.58% respectively (15).

Other Measurements

Body weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated from body weight and height (kg/m2). Current smoking and alcohol consumption, physical activity levels, and menopausal status were collected by questionnaire. Participants who reported that they currently smoked cigarettes, cigars or pipe were coded as current-smokers. Current alcohol consumers were those who consumed a 12 oz bottle of beer, 4 oz of wine, or 1 oz of hard liquor once or more weekly. Sport physical activity level was recorded using the Baecke Habitual Physical Activity questionnaire (17). Women who did not menstruate over the past 12 months or longer or who underwent a hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy were categorized as post-menopausal.

Genotyping

Venous blood samples were collected after overnight fasting, and leukocyte samples were stored in −80°C freezers for later DNA isolation. Isolation of DNA and genotyping of short tandem repeat (STR) markers were conducted in the Department of Genetics at the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research (San Antonio, TX). A total of 400 highly polymorphic markers from the ABI Prism Linkage Mapping Set –MD10 (Ver 2, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) spaced at approximately 10 cM intervals (range 2.4 to 24.1 cM) across 22 autosomes were used. Genotypes were assigned using the Applied Biosystems Genotyper software package, and were based upon known genotypes from Centre d'Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH) DNA samples included with each run (18). Genotypes were initially evaluated for simple Mendelian inconsistencies using the PEDSYS (19) program INFER. Markers were eliminated from further consideration if their Mendelian error rate was greater than 1%. Samples were removed from analysis if they failed typing for more than 5% of markers. The genotyping success rate was 97% for our sample.

Maximum likelihood techniques that accounted for pedigree structure were used to estimate allelic frequencies. For each genetic marker locus, the estimates of the allele frequencies and their standard errors were obtained using the Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR) analytic platform (20). The PEDSYS program PRESWALK was used to clean the genotype data for any remaining Mendelian inconsistencies and excess implied recombinants. Based on the results of a SimWalk2 mistyping analysis (21), PRESWALK blanks genotypes likely to be in error. The error rate was 0.31% based on the PRESWALK mistyping analysis. The genetic map used for the mistyping analysis was constructed from the deCODE map (22). Using this map and the cleaned genotype data, multipoint estimates of IBD-allele sharing among genotyped individuals were calculated using the Markov chain Monte Carlo methods implemented in Loki (23). The resulting multipoint IBD matrices were used in quantitative trait linkage analysis.

Statistical Analysis

QUS traits were examined for normal distribution and kurtosis. QUS values greater than four standard deviations from the mean of each trait (n = 3 for BUA, n = 2 for SOS) were excluded in order to improve normality of the distribution. The relationships between QUS traits and osteoporosis risk factors were tested at the phenotypic level using general linear modeling in Statistical Analysis Software (SAS Ver 9.1.3, SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

A variance component decomposition approach implemented in SOLAR was used to examine evidence for additive genetic effects on QUS traits in quantitative genetic analysis. The heritability (h2) of each QUS trait was estimated as the proportion of the total phenotypic trait variance (σp2) attributable to additive genetic effects (σg2). Covariates included in the genetic analyses were age, age2, sex, age-by-sex, age2-by-sex, BMI, height, current smoking, sport activity level, and menopausal status.

Quantitative Trait Linkage Analysis

A variance components-based linkage analysis method implemented in SOLAR was used (20). The SOLAR analytic platform (20) contains an integrated set of computer algorithms for the detection and localization of QTL. To examine QTL linked to QUS measures, the phenotypic covariance matrix (Ω) for a pedigree is given by:

where π is a matrix of identical by descent (IBD) coefficients at a marker locus that is used to structure σ2q, the variance due to the QTL; Φ is the n × n matrix of kinship coefficients that structures σ 2g, the variance due to additive effects of genes; and I is an identity matrix that serves as the structuring matrix for σ2e, the variance due to unmeasured, non-genetic factors. We tested the null hypothesis that σ2q, (the genetic variance due to the QTL) equals zero (no linkage) by comparing the likelihood of this restricted model with that of a model in which σ2q is estimated. The difference between these two likelihoods produces a LOD (log-odds). Following the approach of Feingold et al. (24), we calculated genome-wide significance levels for our data given the pedigree structure. Significant evidence for linkage (i.e., genome-wide p-value < 0.05) (25) for the QUS phenotypes corresponds to a LODscore of 2.9, and from this 1-Lod unit support intervals forsignificant linkage were determined. Significant covariateswere retained from the quantitative genetic analysis and weresimultaneously adjusted for in the multipoint linkage analysis.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The average age is 47.6 years. Weight, height, and BMI are greater in men than in women (all p-values < 0.05). Men reported higher sport activity compared to women (p-values < 0.01). Phenotypically, there are significant (p-values < 0.01) negative relationships between age and QUS parameters (phenotypic correlation coefficients; r = -0.16 (BUA) and r =-0.32 (SOS)). All three QUS measurements were significantly lower in women than in men (p-values < 0.05). The phenotypic correlation coefficients among QUS traits were r = 0.82 for BUA and SOS, r= 0.92 for BUA and QUI, and r = 0.98 for SOS and QUI (p-values < 0.001).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of study participants (n=719).

| Variables | Total | Males (n=336) | Females (n=383) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.57 (17.21) | 47.68 (17.28) | 47.47 (17.17) |

| Weight (kg) | 79.69 (18.90) | 88.23 (18.14) | 72.23 (16.20)* |

| Height (cm) | 171.57 (9.83) | 179.12 (7.28) | 164.95 (6.42)* |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.98 (5.56) | 27.50 (5.33) | 26.53 (5.72)* |

| Sport activitya | 2.29 (0.69) | 2.44 (0.74) | 2.15 (0.62)* |

| Current smoking (n)b | 165 (22.98%) | 87(25.97%) | 78 (20.37%) |

| Current drinking (n)c | 393 (54.81%) | 217 (64.97%) | 176 (45.95%)* |

| Menopause (n) | -- | 160 (41.78%) | |

| QUS parameters | |||

| BUA (dB/MHz) | 81.53 (19.11) | 84.89 (19.04) | 78.59 (18.70)* |

| SOS (m/s) | 1563.62 (35.29) | 1566.93 (36.09) | 1560.72 (34.36)* |

| QUI | 103.51 (21.64) | 106.25 (21.88) | 101.12 (21.17)* |

Data were presented as mean (standard deviation) otherwise noted. Statistical significance between males and females was denoted as

p < 0.05;

n = 707;

n = 718;

n = 717

Table 2 shows heritability estimates and significant covariates included in the quantitative genetic analysis. All three QUS measures were significantly heritable (h2 ± SE, p < 0.00001): 0.42 ± 0.09 for BUA, 0.57 ± 0.08 for SOS, and 0.52 ± 0.09 for QUI respectively indicating that over 40% of the variance in QUS traits is explained by additive genetic effects. The proportion of the phenotypic variance in QUS traits accounted for by significant covariates such as age, BMI and current smoking status range from 10.4% to 13.8%.

Table 2. Heritability estimates and significant covariates.

| h2 (SE)a | Significant covariates | Variance explained by covariates (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUA | 0.42 (0.09) | BMI, sport activity, current smoking | 13.8 |

| SOS | 0.57 (0.08) | Age, BMI, stature, sport activity, current smoking | 11.7 |

| QUI | 0.52 (0.09) | Age, BMI, stature, sport activity, current smoking | 10.4 |

Heritability estimates presented are adjust for only significant covariates (p < 0.05) among age, sex, age2, age-by-sex interaction, age2-by-sex interaction, BMI, stature, sport activity, current smoking, alcohol use, and menopausal status.

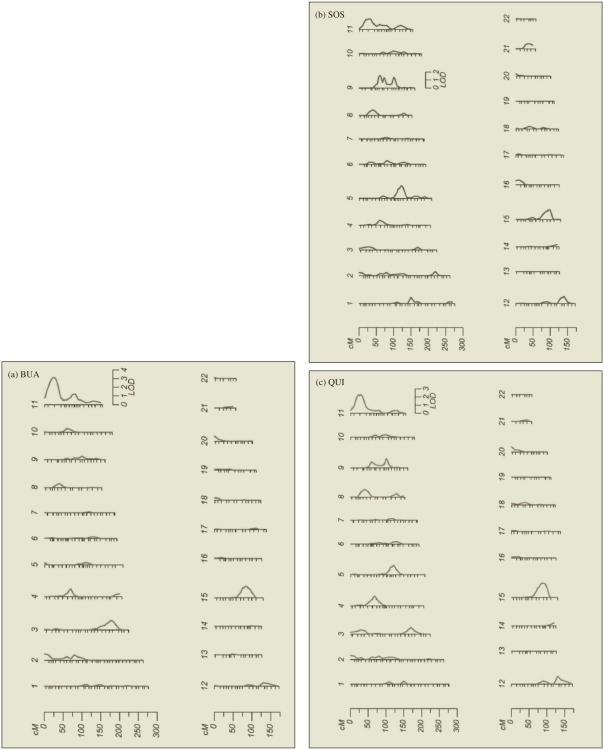

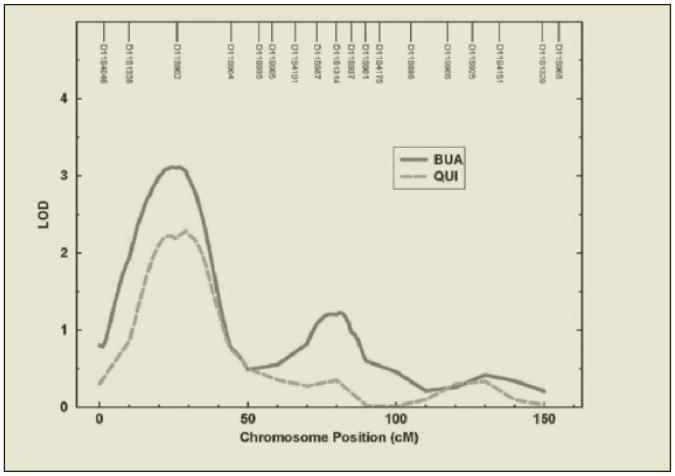

Figure 1 shows the results of genome-wide linkage analysis of QUS parameters and demonstrates several interesting chromosomal regions based on multipoint analysis. Evidence for significant linkage for BUA was detected at chromosome 11 at 27 cM near the marker D11S902 (maximum LOD = 3.11) with a 1-LOD unit support interval ranging 25 cM (approximately 15,379,779 base pairs) from 11 to 36 cM in Figure 2. No strong evidence for linkage of the SOS measure was detected. For SOS, the highest LOD score observed was 1.56 at chromosome 9p near the marker D9S1817. Multipoint linkage results for QUI showed similar results to those for BUA. The strongest signal (LOD = 2.28) for QUI was found at 11p15 (29 cM) close to the marker D11S902. This signal on 11p was near the LOD peak for BUA (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Multipoint genome scans of BUA, SOS, and QUI.

Figure 2. Significant linkage on chromosome 11 for BUA and QUI.

Discussion

Osteoporosis is a complex disease influenced by environmental and genetic factors. Measures of bone mass such as areal BMD are influenced, to varying degrees, by different genes or sets of genes. Even though the underlying genetic mechanisms of BMD have been extensively examined in twin and family studies for the last two decades (2, 3, 5, 6, 26), the influence of genes underlying normal variation in QUS measures has not been explored to a similar extent (7, 13-15). Our estimates of heritability for QUS measures ranged from 0.42 to 0.57 and are consistent with those of other published studies (2, 13).

Many genome-wide linkage scans for BMD have yielded a wealth of information regarding possible candidate loci or suggestive genes (2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 14, 26). Further, the exploration of genome-wide association studies in recent years has resulted in a number of putative single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) linked to variation in BMD and fracture risk (7-9). QUS measurements, as suggested in animal and epidemiologic studies, may provide additional information beyond bone mass in relation to bone metabolism and structural properties of various skeletal sites (27-29). Whilst there are a large number of linkage studies or genome-wide association study of BMD using nuclear or extended families, relatively a few genome-wide linkage analyses of QUS parameters have been conducted. Researchers in the Framingham Osteoporosis Study presented suggestive linkage for BUA to chromosome 1p36.3 (LOD = 2.4) near marker D1S468 (14) and more recently for SOS linked to chromosome 5 at 38.7 cM in females only (LOD = 3.06) and chromosome 6 at 150.7 cM (LOD=2.75) (7). In another study, based on female twins, Wilson et al., found significant linkage of QUS parameters (BUA and VOS) to chromosomes 2q and 4q (13). In the present study, we identified at least one chromosomal region (chromosome 11p15) contributing significantly to variation in BUA. The findings of this study also provide additional evidence for a QTL in the same location for the QUI phenotype, which is a combined index of BUA and SOS.

The significant QTL identified in our study has not been implicated in previous linkage studies of QUS measures. However, our results warrant further investigation. Interestingly, a recent study of bone density detected linkage of BMD changes over 5.6 years of follow up to the same or nearby regions of our chromosome 11p peak (30). Suggestive linkage (LOD = 2.5) to bone loss at the 33% radius was identified at region 11p14-15 among young Mexican Americans from the San Antonio Family Osteoporosis Study (30). The 1-LOD unit support interval for the BUA peak on chromosome 11p15, found in our study, spans approximately 15.3 Mbp and contains 160 known or hypothetical genes. A number of interesting candidate genes with potential influence on bone, calcium and vitamin D metabolism underlie this chromosomal region. Recent genome-wide association studies have demonstrated that allelic variants in SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 6 (SOX6) gene were significantly associated with femoral neck areal BMD (8) and with the bivariate relationship between femoral neck BMD and BMI (31). The SOX6 gene encodes a transcription factor related to a conserved DNA-binding domain called the high mobility group (HMG) box and is expressed abundantly in skeletal muscle (32, 33). With crosstalk between bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling, the SOX6 gene is also associated with chondrocyte proliferation in the process of endochondral bone formation in coordination with BMPs (34, 35).

The CALCA gene coding for calcitonin or calcitonin related polypeptide alpha on 11p15.2 – p15.1 is also within close proximity to our observed linkage peak at 27cM. Produced mainly in the thyroid, calcitonin has been extensively studied for its physiological role as a potent inhibitor of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and calcium excretion by the kidney by modulating the pathways linked to calcium, vitamin D3 and parathyroid hormone (PTH) (36). More recently, studies have suggested that calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP), expressed by the CALCA gene but spliced differentially in neuronal cells, are involved in the proliferation of osteoblasts and inhibition of osteoclast activity via the central and peripheral nervous system (37, 38). Other positional candidate genes in the region include a gene coding for PTH, which is known to be a major regulatory hormone involved in calcium homeostasis and/or vitamin D metabolism, and known to modulate both osteoclastic and osteoblastic activity (39). Another gene coding for cytochrome P450-vitamin D-25-hydroxlase (cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily R, polypeptide 1, CYP2R1) that produces 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the liver (40) is also a potential candidate.

There are some limitations to our study. It is known that linkage studies of complex traits such as osteoporosis have limited success to replicate the significant genetic loci due to an inability to detect individual gene(s) with smaller effects. Our power simulations suggest that our sample and pedigree structure have sufficient power to detect QTL linked to QUS measures. However, linkage in combination with genome-wide association studies in families may help to increase power and to refine the location of gene(s) underlying variation in QUS measures. Future plans include following these results with genome-wide association studies to identify and further refine the location positional candidate genes influencing QUS measures. Another potential limitation is that our study participants were composed of Caucasian families, and these results, therefore, may not be generalizable to other ethnic/racial groups.

In summary, this study has shown that QUS parameters obtained from healthy Caucasian adults over a wide age range are under significant genetic influence. Since calcaneal QUS measurements are correlated with BMD, but also represent somewhat different properties of bone strength, our finding may augment our current understanding of the complex genetic factors influencing osteoporosis risk. We found significant evidence for a QTL for BUA on chromosome 11p15. This region of chromosome 11p has recently been implicated in other genetic studies of BMD, but may contain putative genes involved in the regulation of calcaneal QUS measures as well.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (HD12252 and AR52147) and partially conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program (Grant Number C06 RR13556). The SOLAR statistical genetics computer package was supported by NIH grant (MH059490). We are grateful for the participation of the families in the Fels Longitudinal Study, and the assistance of our research staff. We also thank the research staff at the Department of Genetics, Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, Texas.

This work supported by: NIH grants HD12252 and AR52147

References

- 1.Pocock NA, Eisman JA, Hopper JL, Yeaste MG, Sambrook PN, Eberl S. Genetic determinants of bone mass in adults: a twin study. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:706–710. doi: 10.1172/JCI113125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karasik D, Cupples LA, Hannan MT, Kiel DP. Genome screen for a combined bone phenotype using principal component analysis: the Framingham Study. Bone. 2004;34:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell BD, Kammerer CM, Schneider JL, Perez R, Bauer RL. Genetic and environmental determinants of bone mineral density in Mexican Americans: results from the San Antonio Family Osteoporosis Study. Bone. 2003;33:839–846. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ralston SH, Galwey N, MacKay I, Albagha OM, Cardon L, Compston JE, Cooper C, Duncan E, Keen R, Langdahl B, McLellan A, O'Riordan J, Pols HA, Reid DM, Uitterlinden AG, Wass J, Bennett ST. Loci for regulation of bone mineral density in men and women identified by genome wide linkage scan: the FAMOS study. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:943–951. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiel DP, Demissie S, Dupuis J, Lunetta KL, Murabito JM, Karasik D. Genome-wide association with bone mass and geometry in the Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8(1):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Styrkarsdottir U, Halldorsson BV, Gretarsdottir S, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, Ingvarsson T, Jonsdottir T, Saemundsdottir J, Center JR, Nguyen TV, Bagger Y, Gulcher JR, Eisman JA, Christiansen C, Sigurdsson G, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. Multiple genetic loci for bone mineral density and fractures. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2355–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karasik D, Dupuis J, Cho K, Cupples LA, Zhou Y, Kiel DP, Demissie S. Refined QTLs of osteoporosis-related traits by linkage analysis with genome-wide SNPs: Framingham SHARe. Bone. 2010;46:1114–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, Richards JB, Zillikens MC, Kavvoura FK, Amin N, Aulchenko YS, Cupples LA, Deloukas P, Demissie S, Grundberg E, Hofman A, Kong A, Karasik D, van Meurs JB, Oostra B, Pastinen T, Pols HA, Sigurdsson G, Soranzo N, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Williams FM, Wilson SG, Zhou Y, Ralston SH, van Duijn CM, Spector T, Kiel DP, Stefansson K, Ioannidis JP, Uitterlinden AG. Twenty bone-mineral-density loci identified by large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/ng.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards JB, Kavvoura FK, Rivadeneira F, Styrkarsdottir U, Estrada K, Halldorsson BV, Hsu YH, Zillikens MC, Wilson SG, Mullin BH, Amin N, Aulchenko YS, Cupples LA, Deloukas P, Demissie S, Hofman A, Kong A, Karasik D, van Meurs JB, Oostra BA, Pols HA, Sigurdsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Soranzo N, Williams FM, Zhou Y, Ralston SH, Thorleifsson G, van Duijn CM, Kiel DP, Stefansson K, Uitterlinden AG, Ioannidis JP, Spector TD. Collaborative meta-analysis: associations of 150 candidate genes with osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:528–537. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-8-200910200-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gluer CC, Hans D. How to use ultrasound for risk assessment: a need for defining strategies. Osteoporos Int. 1999;9:193–195. doi: 10.1007/s001980050135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pocock NA, Culton NL, Gilbert GR, Hoy ML, Babicheva R, Chu JM, Lee KS, Freund J. Potential roles for quantitative ultrasound in the management of osteoporosis. Med J Aust. 2000;173:355–358. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb125686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer DC, Ewing SK, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Cummings SR, Orwoll ES. Quantitative ultrasound predicts hip and non-spine fracture in men: the MrOS study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:771–777. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson SG, Reed PW, Andrew T, Barber MJ, Lindersson M, Langdown M, Thompson D, Thompson E, Bailey M, Chiano M, Kleyn PW, Spector TD. A genome-screen of a large twin cohort reveals linkage for quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus to 2q33-37 and 4q 12-21. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:270–277. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karasik D, Myers RH, Hannan MT, Gagnon D, McLean RR, Cupples LA, Kiel DP. Mapping of quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus bone to chromosome 1 by genome-wide linkage analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:796–802. doi: 10.1007/s001980200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee M, Czerwinski SA, Choh AC, Towne B, Demerath EW, Chumlea WC, Sun SS, Siervogel RM. Heritability of calcaneal quantitative ultrasound measures in healthy adults from the Fels Longitudinal Study. Bone. 2004;35:1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roche AF. Growth, maturation, and body composition: the Fels Longitudinal Study, 1929-1991. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baecke JAH, Burema J, Frijters JER. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;36:936–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/36.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray JC, Buetow KH, Weber JL, Ludwigsen S, Scherpbier-Heddema T, Manion F, Quillen J, Sheffield VC, Sunden S, Duyk GM, et al. A comprehensive human linkage map with centimorgan density. Cooperative Human Linkage Center (CHLC) Science. 1994;265:2049–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.8091227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyke B. PEDSYS: A Pedigree Data Management System. Population Genetics Laboratory, Sounthwest Foundation for Biomedical Research; San Antonio, Tex: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobel E, Papp JC, Lange K. Detection and integration of genotyping errors in statistical genetics. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:496–508. doi: 10.1086/338920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong A, Gudbjartsson DF, Sainz J, Jonsdottir GM, Gudjonsson SA, Richardsson B, Sigurdardottir S, Barnard J, Hallbeck B, Masson G, Shlien A, Palsson ST, Frigge ML, Thorgeirsson TE, Gulcher JR, Stefansson K. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2002;31:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heath SC. Markov chain Monte Carlo segregation and linkage analysis for oligogenic models. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:748–760. doi: 10.1086/515506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feingold E, Brown PO, Siegmund D. Gaussian models for genetic linkage analysis using complete high-resolution maps of identity by descent. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:234–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lander ES, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralston SH. Genetics of osteoporosis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66:158–165. doi: 10.1017/S002966510700540X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toyras J, Nieminen MT, Kroger H, Jurvelin JS. Bone mineral density, ultrasound velocity, and broadband attenuation predict mechanical properties of trabecular bone differently. Bone. 2002;31:503–507. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Njeh CF, Fuerst T, Diessel E, Genant HK. Is quantitative ultrasound dependent on bone structure? A reflection. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:1–15. doi: 10.1007/PL00020939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouxsein ML, Radloff SE. Quantitative ultrasound of the calcaneus reflects the mechanical properties of calcaneal trabecular bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:839–846. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.5.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaffer JR, Kammerer CM, Bruder JM, Cole SA, Dyer TD, Almasy L, Maccluer JW, Blangero J, Bauer RL, Mitchell BD. Quantitative trait locus on chromosome 1q influences bone loss in young Mexican American adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;84:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9197-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu YZ, Pei YF, Liu JF, Yang F, Guo Y, Zhang L, Liu XG, Yan H, Wang L, Zhang YP, Levy S, Recker RR, Deng HW. Powerful bivariate genome-wide association analyses suggest the SOX6 gene influencing both obesity and osteoporosis phenotypes in males. PloS one. 2009;4:e6827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Barak O, Hagiwara N, Arlt MF, Horton JP, Brilliant MH. Cloning, characterization and chromosome mapping of the human SOX6 gene. Gene. 2001;265:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hagiwara N, Yeh M, Liu A. Sox6 is required for normal fiber type differentiation of fetal skeletal muscle in mice. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2062–2076. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smits P, Dy P, Mitra S, Lefebvre V. Sox5 and Sox6 are needed to develop and maintain source, columnar, and hypertrophic chondrocytes in the cartilage growth plate. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:747–758. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chimal-Monroy J, Rodriguez-Leon J, Montero JA, Ganan Y, Macias D, Merino R, Hurle JM. Analysis of the molecular cascade responsible for mesodermal limb chondrogenesis: Sox genes and BMP signaling. Dev Biol. 2003;257:292–301. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deftos LJ. Calcitonin. In: Favus MD, editor. Primer on the metabolic bone diseases and disorders of mineral metabolism. 6th. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research; Washington D. C.; 2006. pp. 115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cornish J, Callon KE, Bava U, Kamona SA, Cooper GJ, Reid IR. Effects of calcitonin, amylin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide on osteoclast development. Bone. 2001;29:162–168. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00494-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villa I, Melzi R, Pagani F, Ravasi F, Rubinacci A, Guidobono F. Effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide and amylin on human osteoblast-like cells proliferation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;409:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00872-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bikle D. Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:26–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1678S–1688S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]