Abstract

Study Design

Cross-sectional study with prospective recruitment

Objective

To determine the relationship of pain intensity (back and leg) on patients’ acceptance of surgical complication risks when deciding whether or not to undergo lumbar spinal fusion.

Background

To formulate informed decisions regarding lumbar fusion surgery, preoperative discussions should include a review of the risk of complications balanced with the likelihood of symptom relief. Pain intensity has the potential to influence a patient’s decision to consent to lumbar fusion. We hypothesized that pain intensity is associated with a patient’s acceptance of surgical complication risks.

Methods

Patients being seen for the first time by a spine surgeon for treatment of a non-traumatic or non-neoplastic spinal disorder completed a structured questionnaire. It posed 24 scenarios, each presenting a combination of risks of 3 complications (nerve damage, wound infection, nonunion) and probabilities of symptom relief. For each scenario, the patient indicated whether he/she would/would not consent to a fusion for low back pain (LBP). The sum of the scenarios in which the patient responded that he or she would elect surgery was calculated to represent acceptance of surgical complication risks. A variety of other data were also recorded, including age, gender, education level, race, history of non-spinal surgery, duration of pain, and history of spinal injections. Data were analyzed using bivariate analyses and multivariate regression analyses.

Results

The mean number of scenarios accepted by 118 enrolled subjects was 10.2 (median 8, standard deviation 8.5, range 0 to 24, or 42.5% of scenarios). In general, subjects were more likely to accept scenarios with lower risks and higher efficacy. Spearman’s rank correlation estimates demonstrated a moderate association between the LBP intensity and acceptance of surgical complication risks (r=0.37, p=0.0001) while leg pain intensity had a weak but positive correlation (r=0.19, p=0.04). In bivariate analyses history of prior spinal injections was strongly associated with patients’ acceptance of surgical complication risks and willingness to proceed with surgery (54.5% of scenarios accepted for those who had injections versus 27.6% for those with no prior spinal injections, p=0.0001). White patients were more willing to accept surgery (45.9% of scenarios) than non-whites (28.4%, p=0.03). With the available numbers, age, gender, history of previous non-spinal surgery, education, and the duration of pain demonstrated no clear association with acceptance of surgical complication risks. While education overall was not influential, more educated men had greater risk tolerance than less educated men while more educated women had less risk tolerance than less educated women (p=.023). In multivariate analysis, LBP intensity remained a highly statistically significant correlate (p=0.001) of the proportion of scenarios accepted, as did a history of prior spinal injections (p=0.001) and white race (0.03).

Conclusions

The current investigation indicates that the intensity of LBP is the most influential factor affecting a patient’s decision to accept risk of complication and symptom persistence when considering lumbar fusion. This relationship has not been previously shown for any surgical procedure. These data could potentially change the manner in which patients are counseled to make informed choices about spinal surgery. With growing interest in adverse events and complications, these data could be important in establishing guidelines for patient-directed surgical decision-making.

Keywords: pain, complications, lumbar, fusion, surgery, risk tolerance, acceptance

Introduction

Low back pain is a prevalent and disabling symptom that can arise from a variety of degenerative lumbar disorders. Low back pain may lead to consideration of surgery in carefully-selected patients when non-operative management fails to achieve adequate pain control and an identifiable etiology of pain is suspected.

Many factors can influence a patient’s decision to proceed with surgery 1. A recent study suggested that pain severity and duration were the most important to patients in their decision to proceed with lumbar spine surgery 2, though the relationship of this decision to complication risk was not examined. While clinical experience suggests that patients experiencing intense pain seem more willing to accept a greater likelihood of complications than those with milder pain, this observation has not been confirmed by published data. With growing attention paid to informed choice and adverse events from lumbar surgery, studies of this issue may facilitate improvements in the process of shared surgical decision-making.

The process of shared decision-making continues to evolve 3-6. Weiner 5 highlights a gap between patient-specific expectations and physician-specific outcomes. Barrett et al. 3 found that a patient’s valuation of his or her condition was the strongest predictor of the decision to have lumbar disk surgery, while surgeons placed more value on the location of pain. Lurie and Weinstein 4 described the importance of a patient’s understanding of treatment effectiveness in the shared decision-making process. While these authors highlight that decision-making involves balanced conversation regarding all treatment options with detailed discussion of expected outcomes, none has focused on the potential risks from surgery.

Low back surgery can result in a multitude of complications including nerve injury, wound infection, incontinence, implant failure, and nonunion (pseudarthrosis). It is important for surgeons and patients to discuss these potential adverse events prior to surgery. During such a preoperative shared decision-making (i.e. informed choice) discussion, surgeons should present their best numerical estimates of complication risks as well as the potential for complications to lead to permanent sequelae. In addition, surgeons should present their best estimates of the likelihood of a successful outcome, most basically defined as improvement in preoperative symptoms.

The objectives of this study were to determine the relationship of pain intensity to patients’ acceptance of surgical complication risks when deciding whether or not to undergo lumbar spinal fusion. We hypothesized that increased pain intensity is associated with greater likelihood of patient’s acceptance of surgical complications.

Methods

Study sample composition

Consecutive patients were considered eligible if they were being seen for the first time by a surgeon for treatment of a non-traumatic or non-neoplastic spinal disorder. Inclusion criteria were age of eighteen years or older, ability to speak English, and ability to provide written consent. The exclusion criteria were a history of previous spinal surgery in any region, acute trauma, or an oncologic etiology of spine pain. This study was approved by each hospital’s Institutional Review Board before patient enrollment was initiated. Patients were offered enrollment consecutively.

Prior to the physician seeing the patient for the scheduled consultation visit, a research study coordinator screened all patients in the clinic’s examination room to determine if the subject was eligible. If a subject satisfied the eligibility criteria, the research coordinator described the study in detail. If the patient wished to participate, written consent was obtained. A copy of the signed consent form was given to each patient.

Subjects were enrolled from three major affiliate hospitals of one medical school. At each hospital, candidate subjects were identified from one surgeon’s spine clinic. All three hospitals and clinics were based at high-volume academic teaching institutions in the same urban city in the United States. The demographics and capture areas of the three sites are virtually indistinct.

Data collection and data elements

Subjects completed a brief written questionnaire to collect basic demographic and clinical history data including age, education level, race, employment, and history of prior spinal injections. In addition, subjects were asked to score their level of low back pain and leg pain on a continuous ten-point (0 to 10) visual analog scale (VAS). Zero (0) was described as no pain and ten (10) was described as worst imaginable pain. From this scale, subjects were classified as either having ‘high’ (from 7 to 10) or ‘low’ (from 0 to 6) pain. This cut-off corresponded to the median pain level described.

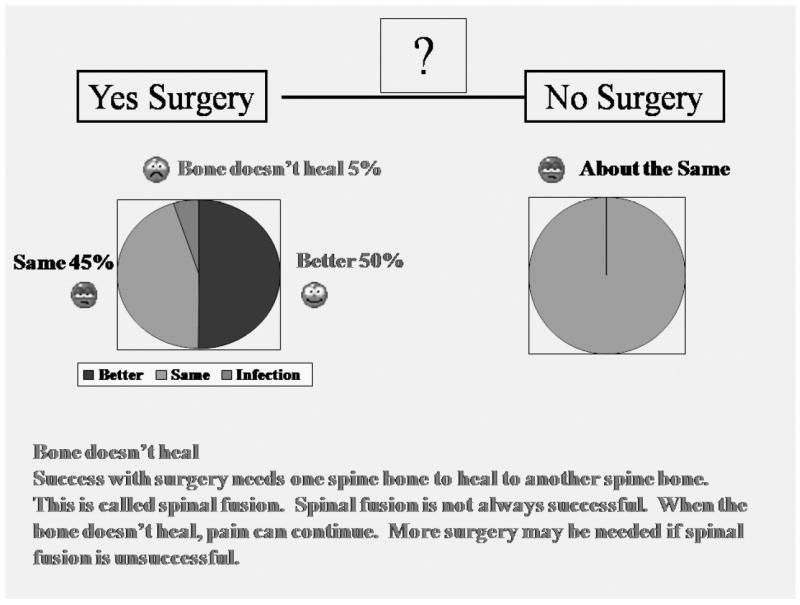

The study coordinator presented the subjects with twenty-four different flashcards depicting surgical scenarios with varying risk likelihoods of three different complications (nerve damage, wound infection, and nonunion) and varying levels of surgical efficacy (likelihood of success in relieving symptoms). Specifically, each flashcard presented a pie chart showing the percent chance of a “success”, defined as no complications and improvement in symptoms, and the respective percent chance of a complication. In each scenario, the sum total of the percentages was 100. The cards included two levels of success: 50% and 70%. Each complication had four levels of risk. For example, for nerve injury the risks included 1%, 3%, 5% or 10%. Thus, the cards included three complications times four levels of risk for each complication times two levels of success, equaling twenty-four different combinations. Figure 1 shows a typical card showing a scenario that included 50 percent chance of success, 45 percent chance of no complications, but no improvement in symptoms and 5% chance of a nonunion. The cards were presented in the same sequence to each patient.

Figure 1.

Example of diagrammatic clinical scenario presented to the patient cohort.

The flashcards used both pie charts and numerical percentages to convey information. This information was also read to patients in a standardized transcript to ensure uniformity. As part of this process, the participant was asked to explain their understanding of the questions being asked. Discrepancies in understanding were addressed on an individual basis. The standardized description emphasized whether the complication would be temporary or permanent and whether it would likely have an effect on clinical outcomes. In addition, the usual prescribed treatment for the complication was described. Subjects were then asked to decide “yes” or “no” as to whether they would be willing to undergo a lumbar spine surgery based on each of the potential outcomes presented. Collected data was de-identified and double-entered into a Microsoft Access database for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

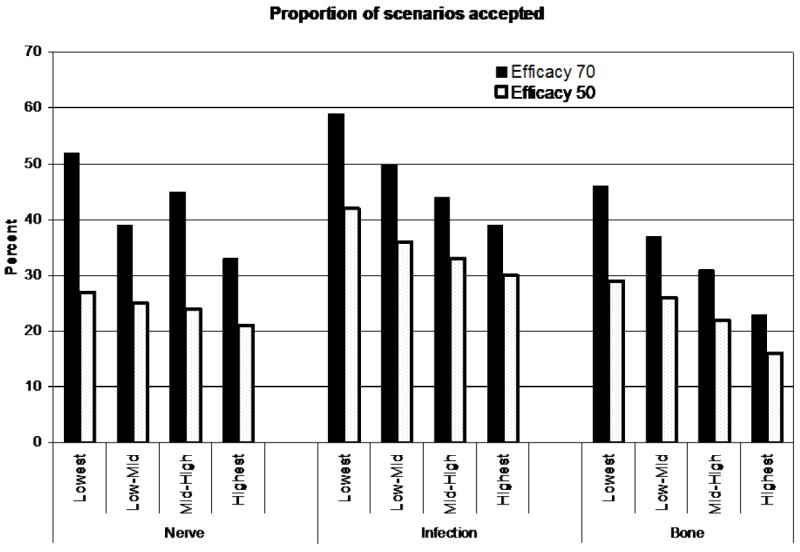

As each patient was presented twenty-four different scenarios, acceptance of surgical complication risks was represented as the sum total number of scenarios in which the patient decided to undergo surgery. This summative variable had a possible range of 0 to 24. In addition, the sum was also represented as a percentage, with a possible range of 0 to 100 percent. It was assumed that the higher the value, the more accepting the patient was to a higher risk of complication. Conversely, the lower the value, the less accepting the patient was of complications. This variable served as the principal outcome variable. This assumption was tested by analyzing the pattern and threshold at which patients responded “yes” or “no” in regards to the percentage likelihood of a complication. That is, patients were much more likely to accept scenarios with high success and low complications than scenarios with low success and high complications (Figure 2). We examined hypothesis-driven multiplicative interactions, such as between education and sex.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of the proportion of scenarios accepted stratified by complication type, complication risk, efficacy of surgery and severity of back pain.

To test the principal study hypothesis, the authors examined the bivariate correlation between pain intensity and the number of scenarios accepted using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (r). In addition, the authors examined the potential relationship of the baseline demographic and clinical variables on acceptance of surgical complication risks. These analyses used the Spearman correlation coefficient for continuous baseline variables and general linear models for categorical or ordinal variables. Bivariate correlates that had p-values less than 0.10 were advanced to multivariate linear regression analyses to identify independent correlates of the acceptance of surgical complication risks (Appendix Table). Analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package.

Results

Of a total of 265 patients who were asked to participate, 118 patients were ultimately enrolled from the spine clinics at the authors’ institutions over a period of six months. The demographic background of the study cohort is presented in Table 1. A comparison of age and gender composition of the study cohort with a randomly selected sample of thirty patients who refused to participate demonstrated that the study cohort was younger (51 years versus 54 years) and more likely to be male than those who refused (51 percent male versus 30 percent, p=0.06). Of note, the percentage of women over 60 years old in the study cohort (17 of 58, 29 percent) was not statistically significantly different than that in the group who refused to participate (7 of 21, 33 percent) (p=0.6).

Table 1.

Baseline features of the study cohort

| Feature | No. of patients (% of study cohort) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Demographic characteristics | |

|

| |

| Age (in years) | |

| <40 | 32 (27.12%) |

| 40-60 | 55 (46.61%) |

| >60 | 31 (26.27%) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Female | 58 (49.15%) |

| Male | 60 (50.85%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 95 (94.07%) |

| African American | 12 (10.62%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (1.77%) |

| Other | 4 (3.54%) |

| * not reported in 5 subjects | |

|

| |

| Education Level | |

| High School or less | 26 (22.03%) |

| Some College | 54 (45.76%) |

| College Graduate | 38 (32.20%) |

|

| |

| Occupation | |

| Professional | 50 (43.10%) |

| Manual/Skilled Manual | 35 (30.17%) |

| Other | 18 (15.52%) |

| Unemployed | 13 (11.21%) |

| * not reported in 2 subjects | |

|

| |

| Clinical Factors | |

|

| |

| History of prior spinal Injections | |

| Yes | 65 (55.08) |

| No | 53 (44.92) |

|

| |

| History of previous non-spinal surgery | |

| Yes | 35 (29.66%) |

| No | 83 (70.34%) |

|

| |

| Degree of back pain | |

| Low | 49 (42%) |

| High | 69 (58%) |

|

| |

| Duration of Pain | |

| < 6 months | 32 (27.35%) |

| > 6 months | 85 (72.65%) |

The mean number of scenarios accepted by the subjects was 10.2 (median 8, standard deviation 8.5, range 0 to 24). The mean proportion of scenarios accepted was 42.5 percent. Twenty-five percent of subjects accepted 0-2 scenarios, 25 percent accepted 3-8, 25 percent accepted 9-17, and 25 percent accepted 18-24 scenarios. In general, subjects were more likely to accept scenarios with lower risks and higher efficacy (see Figure 2).

Spearman rank correlation estimates demonstrated a moderate association between low back pain intensity and acceptance of surgical complication risks (r=0.37, p=0.0001). Leg pain intensity had a weak but positive correlation with the acceptance of surgical complication risks (r=0.19, p=0.04).

The results of bivariate analyses between the baseline variables and acceptance of surgical complication risks (expressed as the proportion of scenarios accepted by the patients) are presented in Table 2. History of prior spinal injections was strongly associated with patients’ acceptance of surgical complication risks and willingness to proceed with surgery (54.5% of scenarios accepted for those who had injections versus 27.6% for those with no prior injections, p=0.0001). White patients were more willing to accept surgery (45.9% of scenarios) than non-whites (28.4%, p=0.03). With the available numbers, age, gender, history of previous non-spinal surgery, education, and the duration of pain demonstrated no clear association with acceptance of surgical complication risks. Unemployed subjects had a somewhat higher acceptance of surgical complication risks. While education overall was not an influential factor, education analyzed for males and females separately did demonstrate a statistically significant relationship on acceptance of surgical complication risks (p=.023). More educated men had greater risk tolerance than less educated men while more educated women had less risk tolerance than less educated women.

Table 2.

Results of the crude and multivariate analysis demonstrating the strength of associations between the baseline demographic and clinical factors and patients’ willingness to undergo surgery with various level of complications and efficacy (expressed as the proportion of the number of scenarios accepted).

| Factors | Proportion of Scenarios Accepted (SE) | Adjusted* mean number of scenarios accepted, 95% CI | P-value for adjusted analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Demographic factors | |||

|

| |||

| Age (in years) | |||

| < 40 | 39.2 (6.3) | ||

| 40-60 | 44.2 (4.8) | ||

| > 60 | 42.7 (6.4) | ||

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 41.6 (4.6) | ||

| Male | 43.3 (4.6) | ||

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 34.6 (6.8) | ||

| College or less | 50.4 (4.7) | ||

| Beyond college | 36.6 (5.6) | ||

|

| |||

| Education by sex | 0.02 | ||

| Female | |||

| High school or less | 49.2 (10.5) | 38.0 (19.2-56.7) | |

| College or less | 50.9 (6.2) | 40.2 (28.3-52.1) | |

| Beyond college | 24.5 (7.8) | 21.7 (6.3-37.1) | |

| Male | |||

| High school or less | 26.9 (8.6) | 18.3 (2.6-34.0) | |

| College or less | 48.2 (6.9) | 44.7 (32.4-57.0) | |

| Beyond college | 47.5 (7.4) | 42.6 (27.6-57.7) | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 45.9 (3.6) | 41.9 (34.2-48.7) | |

| Non white | 28.4 (7.2) | 27.0 (14.2-39.8) | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Occupation | |||

| Professional | 35.5 (5.4) | 25.9 (3.5-8.9) | 0.03 |

| Manual labor | 68.3 (14.9) | 57.6 (31.6-83.6) | |

| Other | 49.4 (5.6) | 38.0 (27.5-48.4) | |

| Unemployed | 58.0 (9.2) | 38.6 (22.6-54.7) | |

| Sedentary | 42.7 (9.6) | 30.1 (13.1-47.1) | |

| Skilled manual | 17.0 (9.23) | 15.3 (-0.9-31.6) | |

|

| |||

| Clinical factors | |||

|

| |||

| History of prior spinal injections | |||

| No | 27.6 (4.5) | 25.4 (15.5-35.3) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 54.5 (4.1) | 43.1 (33.3-53.0) | |

|

| |||

| History of previous non-spinal surgery | |||

| No | 46.3 (3.8) | 40.4 (31.8-49.1) | 0.03 |

| Yes | 33.5 (6.0) | 28.1 (17.0-39.2) | |

|

| |||

| Degree of back pain | |||

| Low | 49.0 (1.2) | 25.1 (14.6-35.5) | 0.001 |

| High | 69.0 (0.9) | 43.4 (34.2-52.7) | |

|

| |||

| Pain duration | |||

| Less than six months | 40.2 (6.3) | ||

| Greater than six months | 43.4 (3.8) | ||

Adjusted means were calculated as adjusted least squared means using the GLM procedure in SAS

Multivariate analyses demonstrated that low back pain intensity remained a highly statistically significant correlate (p=0.001) of the proportion of scenarios accepted, as did a history of prior spinal injections (p=0.001) and white race (0.03). Education stratified by sex (p=0.02), occupation (p=0.03), and history of previous non-spinal surgery (p=0.03) also remained statistically significant predictors of acceptance of surgical complication risks in the multivariate analyses. Leg pain was not significantly associated with the proportion of scenarios accepted in the multivariable model (p=0.48). Analyses in which back pain was expressed as a continuous variable and those in which back pain was dichotomized both demonstrated significant associations between back pain severity and proportion of scenarios accepted. (Appendix Table)

Discussion

Pain, both in the lower back and lower extremities, is a common presenting symptom across a variety of degenerative lumbar conditions. In contrast to many other surgical specialties in which surgery is usually performed for life-threatening processes, such as cardiac ischemia or bowel obstruction, spinal surgery is most commonly elective and indicated for the treatment of pain. Pain intensity varies, both between patients and on a day-to-day basis in an individual. Furthermore, pain does not correlate well with the radiographic severity of spinal conditions 7,8.

Pain intensity is critical to both surgeons’ and patients’ decisions about surgery. However, pain is subjective and, as such, a surgeons’ assessment of a patient’s pain is always dependent upon the patient’s report. Pain reporting can be influenced by various factors, such as ethnicity and gender 9. Despite these observations, pain intensity measurement through instruments such as a visual analog scale (VAS) is routinely included in most clinical outcome studies of low back treatment.

In recent years, the concept of appropriate surgical decision-making has been broadened from simply the physician’s recommendations to have or not have an operation to a discussion between physician and patient about the risks, benefits, and extent that the choice conforms to the patient’s preferences 10-15. This has led to use of the terms “informed choice” or “shared decisionmaking” versus the more traditional “informed consent” 15,16.

The importance of pain on patients’ decision-making has been previously suggested. Bederman et al. 2 studied how patients, family practitioners, and surgeons rated the importance of six different factors in surgical decision-making for the lumbar spine via a mailed questionnaire. Surgeons’ ranked the location of pain as most important, while family practitioners ranked neurological symptoms similarly as pain severity. Patients placed the most importance on pain severity, walking tolerance, and pain duration. Of note, this group did not measure patients’ actual pain; it proposed vignettes in which pain was either “severe” or “moderate”. Furthermore, it did not include complication risk in the decision-making analysis. Notwithstanding, the suggestion that pain severity is in important factor is consistent with the current study’s findings.

The current data have implications for the process of shared decision-making for low back surgery. The data indicate that the level of low back pain intensity is strongly related to a patient’s willingness to consider lumbar surgery. Importantly, this is pain at the time of the clinic visit. This observation should be considered when counseling patients about surgery when they are having a “bad” pain day, at which time they are probably more inclined to consent to surgery. Conversely, a patient on a “good” pain day will probably be less inclined to desire surgery. Knowing this relationship, it may be preferred to have a patient delay a decision for a period of time to balance his or her preferences with risk thresholds, during which pain will likely fluctuate from day to day. In this manner, the patient is less likely to make an immediate decision that is not reflective of how he or she feels on a so-called “average” day.

In distinction to Bederman et al.’s 2 findings that duration was important to patients, the current study did not show a statistical difference between patients with pain more or less than six months in duration. In further contrast, the current data found low back pain to be more correlative to patient’s decision than leg pain, while Bederman et al. found the location of pain was not important to patients. These dissimilarities are particularly interesting when one considers that the current study was not restricted to a single diagnosis, while the previous analysis was performed only in patients with lumbar herniated disks who probably had a predominance of leg pain.

In a group of patients who were offered surgery for a lumbar herniated disc, Barrett et al. 3 studied the effects of viewing a video about patient satisfaction, decision-making, and treatment preferences. From their finding that patients were driven more towards surgery by the video, they concluded that patients’ valuation of their condition was the strongest predictor of a choosing surgery. As the current data demonstrates, the patients’ assessment of his or her pain has a strong relationship of acceptance of surgical complication risk and the willingness to proceed with low back surgery.

Besides pain intensity, the current study has identified a number of other variables that appear to correlate with a patient’s acceptance of surgical complication risks. A history of prior spinal injections showed the strongest association with acceptance of surgical complication risks. As spinal injections are commonly used as a method of nonoperative treatment prior to considering surgery, this variable could be a reflection of a patient’s relative frustration or dissatisfaction with conservative measures. In practice, a surgeon should consider this variable when counseling a patient about surgery and perhaps take greater effort to ensure that the patient clearly understands the risk-benefit ratio of the contemplated procedure.

The current study revealed a lower rate of acceptance of surgical complication risk in nonwhites than whites. This difference reflects a well-documented trend that has demonstrated racial disparities in utilization of care 17,18. Jones et al. 18 reported that African-Americans are less likely to utilize total joint arthroplasty than whites, while Borrero et al. 17 found that black women were more likely to choose tubal ligation versus nonsurgical forms of contraception than white women. As treatment decision-making is affected by many factors, including nonmedical factors such as prayer 18,19, the effect of race on choices concerning low back fusion surgery remains to be better elucidated. With knowledge that non-white patients are more risk adverse and have a lower rate of acceptance of surgical complication risk than whites, the surgeon may have an opportunity to better counsel non-white patients in attempts to avoid disparities in spinal care.

The effect of education level on risk tolerance was complex. Higher education was associated with a greater proportion of scenarios accepted in men and a lower proportion in women. This relationship has not been previously reported to our knowledge. Further investigation is warranted to better understand this apparent gender difference.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations inherent in the design of this study. First, only three specific complications were studied. As an initial study on this topic using a novel instrument to gauge patent’s risk tolerance, it was felt that examining more than three complications would have introduced too much complexity to the analysis. However, this limits the applicability of the current findings to other common adverse events, such as spinal fluid leak and adjacent segment degeneration. Importantly, the complications selected are those that are most likely to have the potential for early postoperative morbidity (nerve injury, pseudarthrosis, or infection). Complications, such as spinal fluid leak, rarely result in significant sequale 20, while others, such as adjacent segment degeneration, occur many years after surgery and may have less effect on a patient’s surgical decision.

Pain intensity was measured on only one occasion. It is not known if the relationship between patients’ pain and their responses would have been changed during a second survey occasion. This will likely require further study. However, the data presented suggests strong correlations between pain intensity and surgical decisions for the study cohort. Thus, one would postulate that this relationship would be demonstrable in a single individual on multiple occasions. As the instrument used in this study is novel, the reliability and validity of this method of risk tolerance assessment to predict a patient’s actual decision to proceed with surgery is not known. Further research is planned to better understand these features. As 265 patients were screened in order to enroll 118 patients into the study, there was the potential for selection bias. This is corroborated by the differences noted between those who participated and those who refused to participate in the study. Finally, the underlying condition for the patients’ consultation (i.e. cervical versus thoracic versus lumbar problem) could have influenced the results. While this variable was not recorded or considered in the analysis, this would have potentially introduced greater variability of the data and therefore less likelihood of finding a statistical correlation.

Conclusion

Lumbar fusion is a commonly performed procedure for the treatment of a variety of spinal conditions. The current investigation indicates that the intensity of low back pain was the most influential factor affecting a patient’s decision to accept risk of complication and symptom persistence when considering this procedure. This relationship has not been previously shown for any surgical procedure. These data could potentially change the manner in which patients are counseled to make informed choices about spinal surgery. With growing interest in adverse events and complications, these data could be important in establishing guidelines for patient-directed surgical decision-making.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Among a large group of potential surgical candidates evaluated by a structured questionnaire, low back pain intensity is highly influential on a patients’ decision to proceed with lumbar fusion surgery.

There is a direct relationship between low back pain intensity and patients’ acceptance of complication risk.

An unanticipated disparity in complication acceptance between white and non-white patients was detected.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Benjamin Rome, B.A., for invaluable editorial assistance.

Support: The Program for Research Incubation and Development, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and NIH/NIAMS K24 AR 057827

References

- 1.Phelan EA, Deyo RA, Cherkin dC, et al. Helping patients decide about back surgery: a randomized trial of an interactive video program. Spine. 2001;26:206–11. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200101150-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bederman SS, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, et al. In the eye of the beholder: preferences of patients, family physicians, and surgeons for lumbar spinal surgery. Spine. 2010;35:103–15. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b77f2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett PH, Beck A, Schmid K, et al. Treatment decisions about lumbar herniated disc in a shared decision-making program. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28:211–9. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(02)28020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lurie JD, Weinstein JN. Shared decision-making and the orthopedic work force. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2001;385:65–75. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiner BK. Matching patient-specific expectations with physician-specific outcomes: towards transparency in treatment decision-making and consent. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1287–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein JN. The missing piece: embracing shared decision making to reform health care. Spine. 2000;25:1–4. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200001010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borenstein DG, O’Mara JW, Boden SD, et al. The value of magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine to predict low-back pain in asymptomatic subjects: a seven-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1306–11. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:403–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faucett J, Gordon N, Levine J. Differences in postoperative pain severity among four ethnic groups. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1994;9:383–9. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Entwistle V, Williams B, Skea Z, et al. Which surgical decision should patients participate in and how? Reflection on women’s recollections of discussion about variants of hysterectomy. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Entwistle VA, Sheldon TA, Sowden A, et al. Evidence-informed patient choice. Practical issuesof involving patients in decision about health care technologies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998;14:212–25. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300012204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazur DJ, Hickman DH. Patients’ preferences for risk disclosure androle in decision making for invasive medical procedures. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:114–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00016.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mazur DJ, Merz JF. Older patients’ willigness to trade offurologic adverse outcomes for a better chance at five-year survival in the clinical setting of prostate cancer. J Am Geriatr. 1995;43:979–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thistlewaite J, Evans R, Tie RN. Shared decision making and decision aids-a literature review. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:537–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein JN, Clay K, Morgan TS. Informed patient choice: patient-centered valuing of surgical risks and benefits. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:726–30. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiss CG, Richter-Muesksch S, Stifter E, et al. Informed consent and decision making by cataract patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:94–8. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Rodriguez KL, et al. “Everything I know I learned from my mother…Or not”: perspectives of African-American and white women on decisions about tubal sterilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:312–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones AC, Kwoh CK, Groenveld PW, et al. Investigating racial differences in coping with chronic osteoarthritis pain. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008;23:339–47. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang DC, Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, et al. Ethnic differences in the perception of prayer and consideration of joint arthroplasty. Med Care. 2002;40:471–6. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JC, Bohlman HH, Riew KD. Dural tears secondary to operations on the lumbar spine. Management and results after a two-year-minimum follow-up of eighty-eight patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1728–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199812000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.