Abstract

The Drosophila central brain is largely composed of lineages, units of sibling neurons derived from a single progenitor cell or neuroblast. During the early embryonic period neuroblast generate the primary neurons that constitute the larval brain. Neuroblasts reactivate in the larva, adding to their lineages a large number of secondary neurons which, according to previous studies in which selected lineages were labeled by stably expressed markers, differentiate during metamorphosis, sending terminal axonal and dendritic branches into defined volumes of the brain neuropil. We call the overall projection pattern of neurons forming a given lineage the “projection envelope” of that lineage. By inducing MARCM clones at the early larval stage, we labeled the secondary progeny of each neuroblast. For the supraesophageal ganglion excluding mushroom body (the part of the brain investigated in the present work) we obtained 81 different types of clones, Based on the trajectory of their secondary axon tracts (described in the accompanying paper), we assigned these clones to specific lineages defined in the larva. Since a labeled clone reveals all aspects (cell bodies, axon tracts, terminal arborization) of a lineage, we were able to describe projection envelopes for all secondary lineages of the supraesophageal ganglion. This work provides a framework by which the secondary neurons (forming the vast majority of adult brain neurons) can be assigned to genetically and developmentally defined groups. It also represents a step towards the goal to establish, for each lineage, the link between its mature anatomical and functional phenotype, and the genetic make-up of the neuroblast it descends from.

Keywords: Brain, Development, Drosophila, Lineage, Mapping, SAT

Introduction

In the field of developmental biology, the concepts of cell determination and cell lineage are fundamental to our understanding of the formation of complex tissues and organs. When talking about cell lineage we refer to the genealogy (family tree) of groups of cells. The lineage produced by a progenitor cell is generally used synonymously with the progeny descending from this cell. During early stages of development, a progenitor cell initiates a genetic program that controls the later fate of this cell and its progeny. The genetic program of the progenitor is defined by the expression of cell fate determinants, typically transcription factors, that either remain active in the progeny or trigger the expression of a next tier of factors impacting the fate of the progeny (Guillemot, 2007; Shirasaki and Pfaff, 2002; Skeath and Thor, 2003). Thus, when embarking on the analysis of a complex organ, one of the assumptions that guides our research is that cells which possess a similar phenotype do so because they are part of a lineage produced by a common progenitor which, early on, expresses a set of transcription factors (“intrinsic determinants”) controlling the fate of its lineage. Of course, this assumption has to always be tested against the alternative: extrinsic signals from the environment into which cells are placed trigger a genetic switch in these cells which controls their fate. In this scenario, the family tree of the cells is not important.

The fate of cell lineages in the Drosophila nervous system is heavily influenced by intrinsic determinants. A number of pioneering experiments in which neural progenitors (neuroblasts) were cultured in vitro revealed that, even when removed from their natural environment in the early embryo, neuroblasts are capable of dividing and producing progeny in the same number and cell type (assayed by expression of neurotransmitters) (Huff et al., 1989). Later studies identified many specific transcription factors expressed in neuroblasts (Doe, 1992; Urbach and Technau, 2003). Furthermore, it was shown that the timing of expression of a transcription factor is able to influence the fate of subsets of neurons (“sublineages”) forming part of a lineage (Brody and Odenwald, 2000; Isshiki et al., 2001; Kambadur et al., 1998; Pearson and Doe, 2004). Thus, a neuroblast (N) divides asymmetrically, with one daughter cell (N’) remaining in the state of a dividing neuroblast, whereas the other daughter cell (ganglion mother cell), after an additional round of division, becomes postmitotic and differentiates into two daughter cells (neurons or glia). The asymmetric division allows for a mechanism by which transcription factors are differentially inherited by daughter cells. The general model is that transcription factor (A), expressed during a specific time interval, will be inherited by one daughter cell or sublineage (α). Eventually, (A) is no longer expressed and a second one (B) turns on. All neurons born after (A) is turned off now inherit (B) and become a second sublineage (β). Several transcription factors were identified that are expressed in a sequential manner during neuroblast proliferation in the embryo, and were shown, using molecular markers as a read-out, to influence the fate of embryonic-born (primary) neurons (Isshiki et al., 2001; Kambadur et al., 1998). However, it should be emphasized that many transcription factors are active in neuroblasts from before they are mitotically active through to a later developmental period, and that this window of expression varies for each transcription factor (Doe, 1992; Kumar et al., 2009a-b; Lichtneckert et al., 2008; Urbach and Technau, 2003); these factors would be predicted to have an impact on the fate of an entire lineage.

Analyses of a few select lineages in the larval and/or adult brain support the idea that neuronal fate is controlled by factors inherited by entire lineages and by specific sublineages, which may manifest itself in a lineage's overall structure. Thus, lineages appear as “morphological units,” with all axons forming one or two (in the case of hemilineages; Truman et al., 2010) bundles and terminal arborizations focusing on a discrete neuropil territory. For example, four lineages (MB1-4) form the mushroom body (Crittenden et al., 1998; Ito et al., 1997) and three lineages, (vNB/BAla1, lNB/BAlc and dNB/BAmv3) include the majority of projection neurons connecting the antennal lobe with the protocerebrum (Lai et al., 2008). Endings of all secondary neurons of MB1-4 are confined to the calyx, peduncle, and lobes of the mushroom body; the antennal lobe–associated lineages innervate three compartments, namely the antennal lobe, calyx, and lateral horn (Das et al., 2013; Lai et al., 2008; Stocker et al., 1990). We will use the term “projection envelope” to describe the overall neuropil volume that is innervated by neurons of a lineage. Individual neurons in a lineage form restricted terminal arbors that target smaller volumes within the projection envelope. For example, the neurons produced by MB1-4 in the late embryo/early larva fill the γ-lobe; they are followed by neurons forming the α’/β’ lobes, and finally by neurons of the α/β lobes (Ito et al., 1997; Kunz et al., 2012). In the case of dNB/BAmv3, most neurons innervate a single glomerulus of the antennal lobe and project to discrete regions within the calyx and lateral horn (Jefferis et al., 2001; Yu et al., 2010). It is reasonable to assume that the projection envelope of a lineage, which is shared by all neurons of that lineage, is determined to some extent by transcription factors expressed earlier in development and are common to the neuroblast of that lineage. In addition, other factors expressed later at defined temporal intervals, thereby only reaching neurons born during that interval, may be responsible for more specific structural and functional characteristics that set neurons of a lineage apart from each other.

Whereas both expression of molecular determinants of cell fate and the phenotypic elements of cell fate (e.g., shape of neuronal arbor, choice of pre-and postsynaptic partners, physiological characteristics) can be studied in great detail, the complex cascade of molecular events linking the two levels has remained elusive. What mechanism acts on outgrowing axons and guides/restricts them to a specific compartment? How is this mechanism encoded in the cell fate determinants expressed in the neuroblast? Drosophila offers a favorable system to address these questions: its nervous system is built by a relatively small number of lineages (previous descriptive maps yielded approximately 100 lineages per central brain hemisphere and 28 lineages per ventral nerve cord hemineuromere; Doe, 1992; Urbach and Technau, 2003; Younossi-Hartenstein et al., 1996). Lineages can be globally and/or individually labeled by antibodies for various neuronal proteins (e.g. mushroom body-specific antibodies: Crittenden et al., 1998; neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor or PDF: Helfrich-Förster et al., 2007; neuropeptide IPNamide: Shafer et al., 2006) and reporter constructs (LacZ and Gal4-based: e.g. en-Gal4, Kumar et al., 2009b; Th-Gal4, Mao and Davis, 2009; Gal4 lines expressed in ellipsoid body neurons, Renn et al., 1999). Maps of the expression of transcription factors in the neuroblasts, as well as the anatomical pattern of lineages at the larval stage, have been generated (Cardona et al., 2010; Pereanu and Hartenstein, 2006; Truman et al., 2004; Urbach and Technau, 2003; Urbach and Technau, 2004). In the accompanying paper (Lovick et al., 2013) we had mapped the association between lineages and neuropil fascicles and followed these fascicles throughout metamorphosis into the adult. In this paper, we have analyzed individual lineages at the adult stage by the MARCM technique (Lee and Luo, 2001), where a GFP reporter gene is activated by somatic recombination in neuroblasts shortly before they enter their larval phase of proliferation. In this manner, all secondary neurons produced by these neuroblasts (the “secondary lineages”) are labeled as “clones.” A clone includes the cluster of cell bodies derived from the larval neuroblast, as well as the axons and terminal arborizations of these cell bodies. Based on the trajectory of their axon bundles, we are able to assign clones to their respective lineages. We analyzed a total of 814 clones located in the supraesophageal ganglion, the largest part of the brain. Excluded from this study are clones in the optic lobes, whose modular (and probably not-lineage based) structure has been described previously (Bausenwein et al., 1992; Fischbach and Dittrich, 1992). Excluded are also clones representing the four well known lineages of the mushroom body (Crittenden et al., 1998; Ito et al., 1997; Kunz et al., 2012), and the lineages of the subesophageal ganglion, which will be analyzed in an upcoming study (Kuert et al., in preparation). Clones fell into 81 groups, where each group corresponded to a known lineage or lineage pair. We provide a brief description of the projection envelopes for all lineages. The complexity of these lineages clearly warrants a much finer level of analysis, taking into account aspects like overlap of terminal arborizations of different lineages, precise relationships between arborizations and compartment boundaries, and variations in the size and location of cell bodies. These investigations, which require that specimens with different clones are digitally registered to a “standard brain”, will be presented in a series of upcoming studies. Note that numerous aspects of lineage analysis has been recently published in two large, independent studies where MARCM clones of secondary lineages were generated (Ito et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2013). The main purpose of the present work is to identify clones with defined lineages, contributing to the ultimate goal of linking the mature anatomical and functional phenotype of a lineage and its constituent neurons with the specific genetic make-up of the embryonic neuroblast that produces the lineage.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Fly Stocks

Flies were grown at 25°C using standard fly media unless otherwise noted. Fly stocks used are the ones detailed in the Clonal Analysis section below.

Immunohistochemistry

Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, Fisher-Scientific, pH = 7.4; Cat No. #BP399-4). Tissues were permeabilized in PBT (phosphate buffer saline with 0.3% Triton X-100, pH = 7.4) and immunohistochemistry was performed using standard procedures (Ashburner 1989). The following antibodies were provided by the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (Iowa City, IA): mouse anti-Neurotactin (BP106, 1:10), rat anti-DN-cadherin (DN-EX #8, 1:20), mouse anti-Neuroglian (BP104, 1:30). Secondary antibodies, IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch; Molecular Probes) were used at the following dilutions: Alexa 546-conjugated anti-mouse (1:500), DynaLight 649-conjugated anti-rat (1:400).

Clonal Analysis

Clones were generated by Flp-mediated mitotic recombination at homologous FRT sites. Larval neuroblast clones were generated by MARCM (Lee and Luo, 2001; see below) or the Flp-out construct (Zecca et al., 1996; Ito et al., 1997).

Mitotic clone generation by Flp-out

To generate secondary lineages clones in the larva using the Flp-out technique; flies bearing the genotype:

hsflp, elavC155-Gal4/+; UAS-FRT-rCD2, y+, stop-FRT-mCD8::GFP

hsflp; Act5C-FRT-stop,y+-FRT-Gal4, UAS-tauLacZ/UAS-src::EGFP

Briefly, early larva with either of the above genotype were heatshocked at 38°C for 30-40 minutes. elavC155-Gal4 is expressed in neurons as well as secondary neuroblasts.

Third instar larval and adult brains were dissected and processed for immunohistochemistry (as described above).

Mitotic clone generation by MARCM

Mitotic clones were induced during the late first instar/early second instar stages by heat-shocking at 38°C for 30 minutes to 1 hour (approximately 12h-44h ALH). GFP-labeled MARCM clones contain the following genotype:

Adult MARCM clones

hsflp/+; FRTG13, UAS-mCD8GFP/FRTG13, tub-GAL80; tub-Gal4/+ or

FRT19A GAL80, hsflp, UAS-mCD8GFP/ elavC155-Gal4, FRT19A; UAS-CD8GFP/+

Larval MARCM clones

hsflp, elavC155-Gal4, FRTG13, UAS-mCD8GFP /Y or hsflp, elavC155-Gal4, FRTG13, UAS-mCD8GFP /; FRT42D, tub-Gal80/FRT42D

Confocal Microscopy

Staged Drosophila larval and adult brains labeled with suitable markers were viewed as whole-mounts by confocal microscopy [LSM 700 Imager M2 using Zen 2009 (Carl Zeiss Inc.); lenses: 40× oil (numerical aperture 1.3)]. Complete series of optical sections were taken at 2-μm intervals. Captured images were processed by ImageJ or FIJI (National Institutes of Health, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/ and http://fiji.sc/) and Adobe Photoshop.

2D registration of clones to standard brain

Brains with MARCM clones were labeled with DN-cad and BP104 to image the SAT and projection envelope relative to the BP104-positive fascicles and DN-cad-positive neuropil compartments. Fasciculation of the SAT of a clone with a fascicle allowed for its identification with a lineage, or lineage pair (see accompanying paper by Lovick et al., 2013). To generate the figure panels of this paper, z-projections of the individual MARCM clones were registered digitally with z-projections of a standard brain (“2D registration”). To this end, the standard brain was subdivided along the antero-posterior axis into six slices of approximately 20 μm thickness. These slices, each one characterized by one or more easily recognized landmark structures (antennal lobe, optic tubercle, ellipsoid body, fan-shaped body, lateral bend of antennal lobe tract, calyx), are introduced in Pereanu et al., 2010, and are depicted throughout the figures of this and the accompanying paper (Lovick et al., 2013). The process of 2D registration involved the following steps:

The confocal stack depicting a given clone was imported into the FIJI program (National Institutes of Health, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/ and http://fiji.sc/) and digitally oriented such that the peduncle was aligned with the z-axis of the stack;

A z-projection of the entire clone (e.g., all sections of the green channel showing label) was generated;

In the case of brains containing more than one clone, background fluorescence and/or fluorescence from other clones were digitally removed to allow visualization of a single clone;

This z-projection was merged with a z-projection of the red channel (BP104 or DN-cad) derived from the confocal sections of one slice. The chosen slice is dependent upon the corresponding clone's SAT location. For example, consider the lineage BAlp4, whose SAT enters the antennal lobe postero-laterally. In terms of antero-posterior brain slices, this SAT forms part of the second slice (“level optic tubercle”);

Both the optic tubercle slice of the standard brain and the brain specimen containing the BAlp4 clone were imported as two layers into a file generated by the Adobe Photoshop program. Using few standard landmarks (location of the peduncle, tips of the MB vertical and medial lobe, vertical midline), the layer containing the clone (rendered temporarily semitransparent) was optimally fitted to the underlying layer representing the standard brain;

The optimally-fitted layer containing the clone was re-opened in FIJI, and then merged with the red channel (BP104 or DN-cad) of the standard brain. For the panels of the figure set depicting clone SATs relative to BP104-positive fascicles (Figs.5, 7, 10, 13, 16, 18), the red channel (BP104) was rendered white in Adobe Photoshop. For the figure set depicting the projection envelopes of clones (Figs.3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17), the red channel (DN-cad) was rendered magenta by duplicating it in the blue channel.

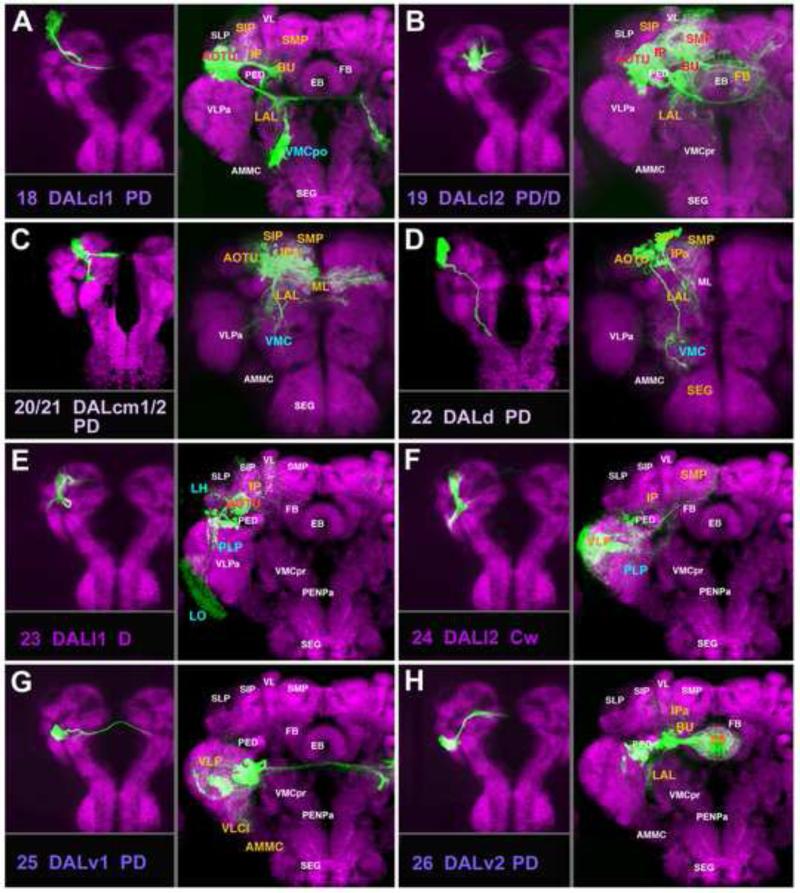

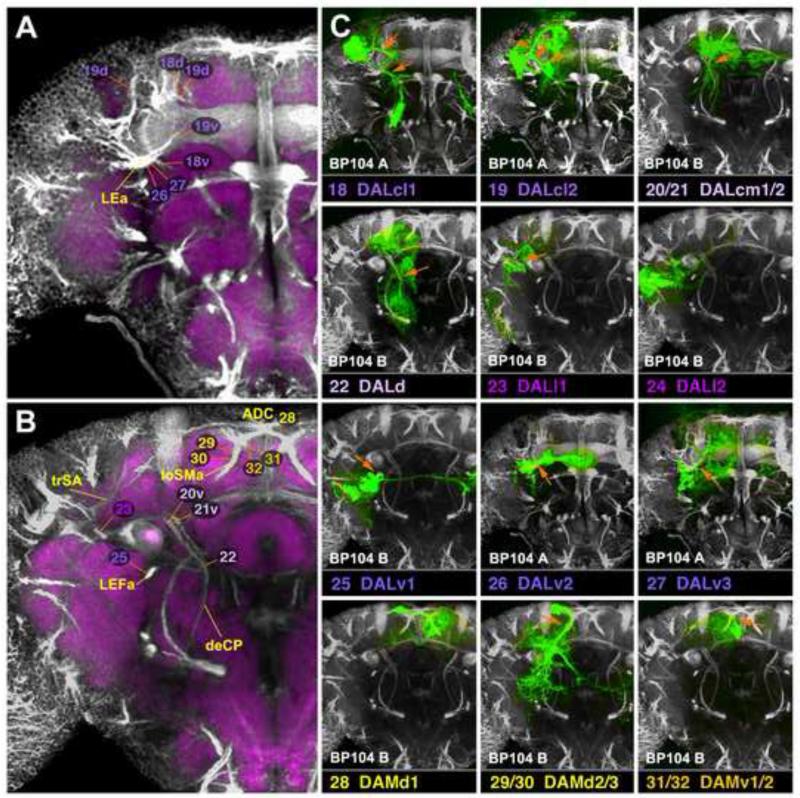

Figure 5.

A-H: Clones representing lineages of the DAL group (#18/DALcl1 to #26/DALv2) in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

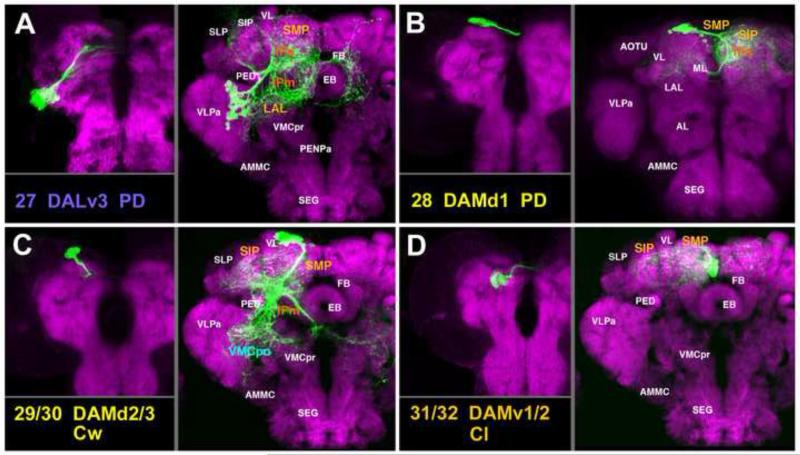

Figure 7.

A-D: Clones representing lineages of the DAL group (#27/DALv3) and the DAM group in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

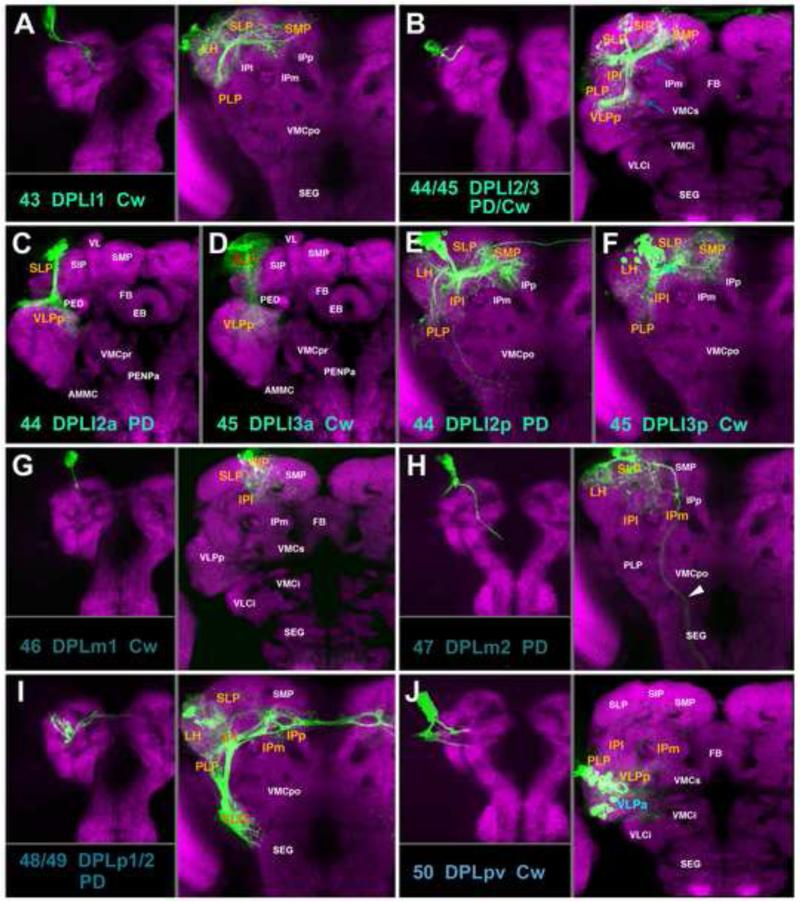

Figure 10.

A-J: Clones representing lineages #43/DPLl1 to #50/DPLpv of the DPL group in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. The lineage pair DPLl2/3 is represented by five modified panels. The first of these (B) shows z-projection of entire DPLl2 clone registered to a central slice of the brain (level of fan-shaped body). At the larval stage, only one type of clone, represented at the left of B, exists for the DPLl2/3 pair. Blue arrows point at anterior and posterior HSATs. Panels C and D show z-projections of the anterior hemilineages (#44 DPLl2a and #45/DPLl3a, respectively), registered to an anterior slice. Panels E and F show posterior hemilineages of DPLl2/3, registered to posterior brain slice. White arrows point at an anterior segment of the SAT which, in case of DPLl2, is dense and thin, and in case of DPLl3, wide and diffuse. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

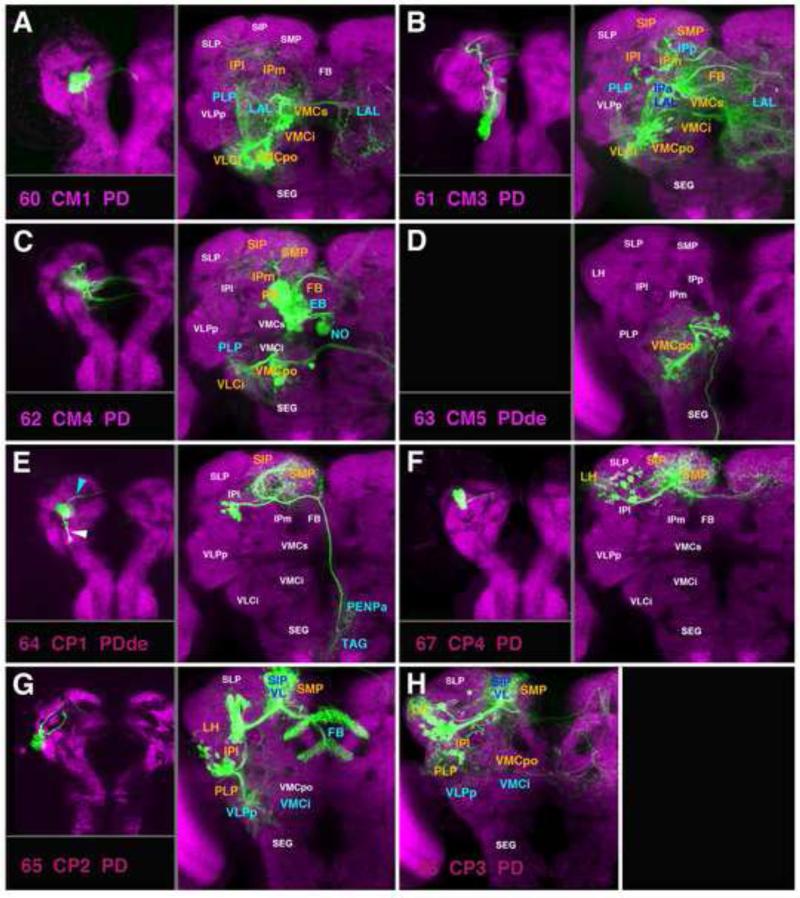

Figure 13.

A-H: Clones representing lineages of the CM and CP group in the larval and adult brain. No larval clone for CM5 (D) was isolated. For the pair CP2/3 (G, H), only one larval clone (panel G, left) is shown. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

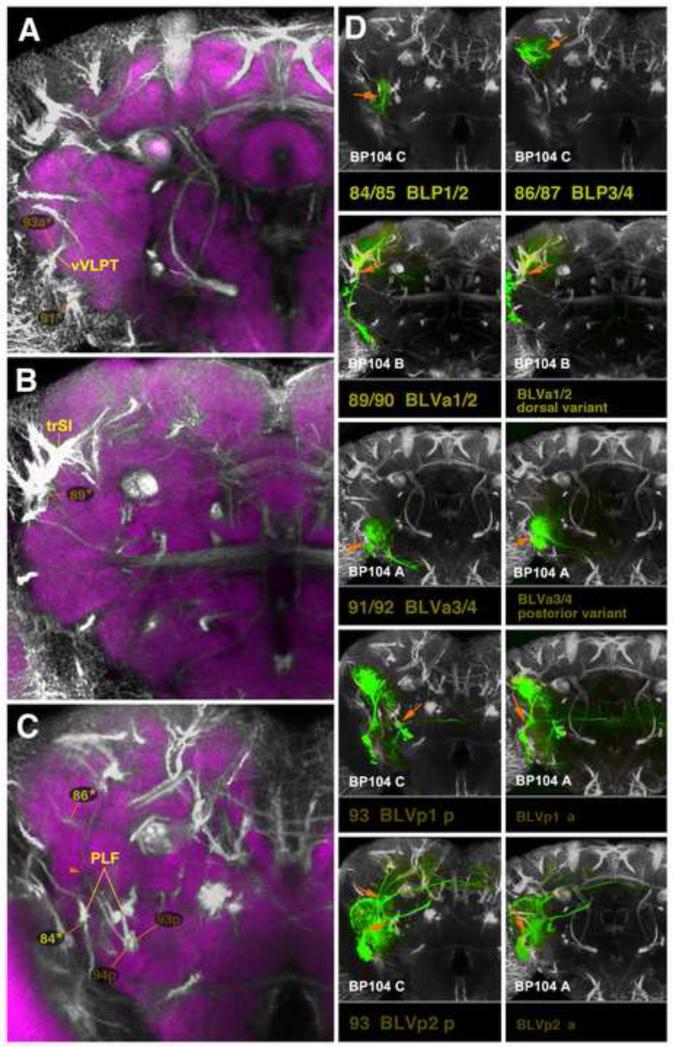

Figure 16.

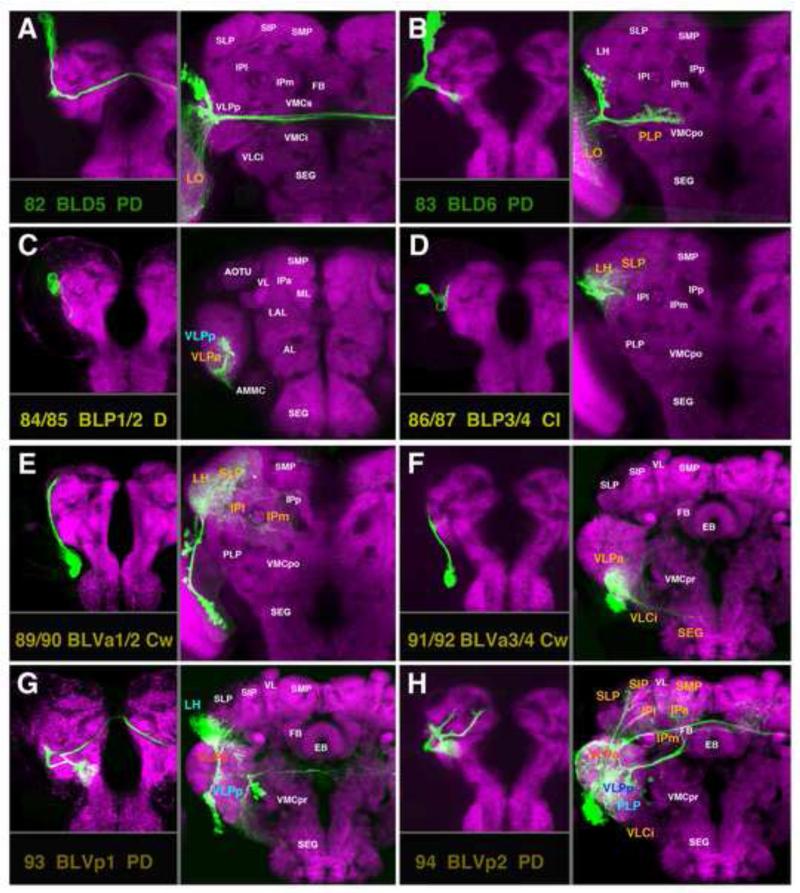

A-H: Clones representing lineages #82/BLD5-#83/BLD6 of the BLD group and lineages of the BLP and BLV group in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

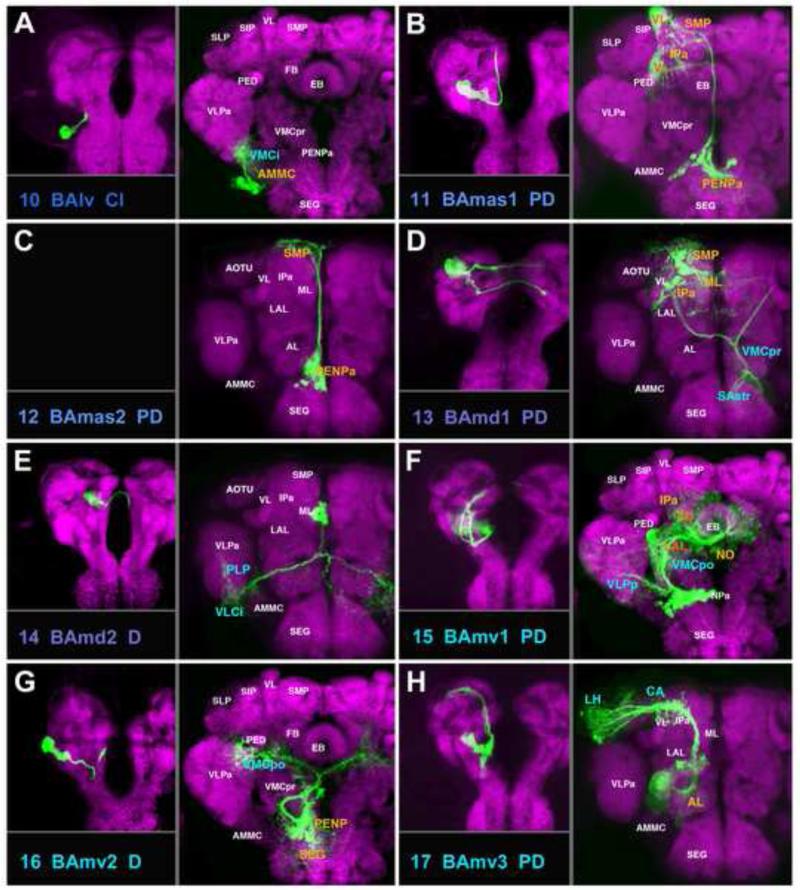

Figure 3.

A-H: Clones representing lineages of the BA group (#10/BAlv to #17/BAmv3) in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. Only one larval clone is shown for the pair BAmas1/2 (panels B and C). For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

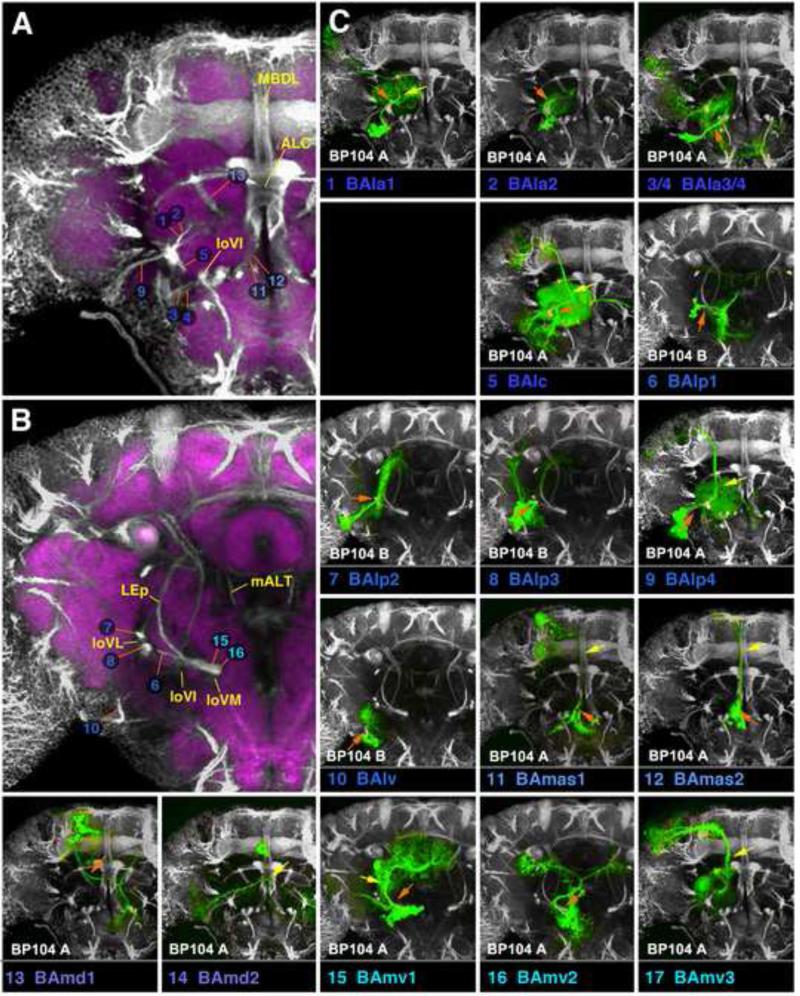

Figure 4.

Clones representing lineages of the BA group in the adult brain. This figure, as well as the following figures 6, 9, 12, 15, and 17, are all designed in the same manner. Large panels on the left (A, B in case of Fig.4) show z-projections of frontal confocal sections of adult brain hemisphere labeled with BP104 (white, SATs and neuropil fascicles) and DN-cad (purple; neuropil compartments). Each z-projection represents a brain slice of approximately 15-20µm thickness. Brain slices correspond to different levels along the antero-posterior (“z”) axis. Panels A and B of this figure represent the two slices of the brain where BA lineage tracts enter the neuropil (A: level of optic tubercle and mushroom body lobes; B: posteriorly adjacent slice, marked by ellipsoid body). SATs of lineages are annotated by colored numbers; the same color key is used as in the accompanying paper by Lovick et al. (2013). In cases where two or more SATs or HSATs come very close and cannot be distinguished, the identifying numbers may be contracted into a single number followed by an asterisk; see, for example, the annotation of the HSATs of the DPLal2/3 lineages, #34/35, as “34v*” and “34d*”, in Fig.9A. Fascicles with which SATs are associated are annotated by yellow letters. (C): The small panels in section (C) of this figure show z-projections of clones representing lineages of the BA group. Panels were generated by registering z-projection of clones to a “slice” of the BP104-labeled standard brain, as described in the Materials and Methods section. Each lineage is identified by a number and abbreviation (bottom of its panel), rendered in the same color as that used in panels A and B. For the BP104 channel (white), only slices shown in the left panels (A, B) are used and indicated at the bottom left of the panel (“BP104 A”, “BP104 B”). For example, the first small panel depicts lineage #1/BAla1. The clone is registered to the anterior slice (“optic tubercle/mushroom body lobes”; shown at higher magnification in panel A), because the proximal SAT of BAla1 is contained within this slice. Panels with other lineages (e.g., #10/BAlv) use the more posterior slice (the one shown in panel B; ellipsoid body), because the SAT of BAlv is contained within that slice. In each small panel, the orange-colored arrow points at the proximal SATs by which the clone is identified. In terms of position and orientation, the arrow matches the orange line in panel on the left (A or B) which points at the corresponding BP104-labeled tract. Yellow arrows in the C-panels point at neuropil fascicles joined by the SAT. For example, the yellow arrow in the panel #1/BAla1 points at the beginning of the antennal lobe tract (ALT). For alphabetical list of abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 25μm

Figure 6.

Clones representing lineages of the DAL and DAM groups in the adult brain. (A, B) z-projections show brain slices at level of optic tubercle/mushroom body lobes (A) and ellipsoid body (B). (C) z-projections of clones representing lineages of the DAL and DAM group. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.4. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 8.

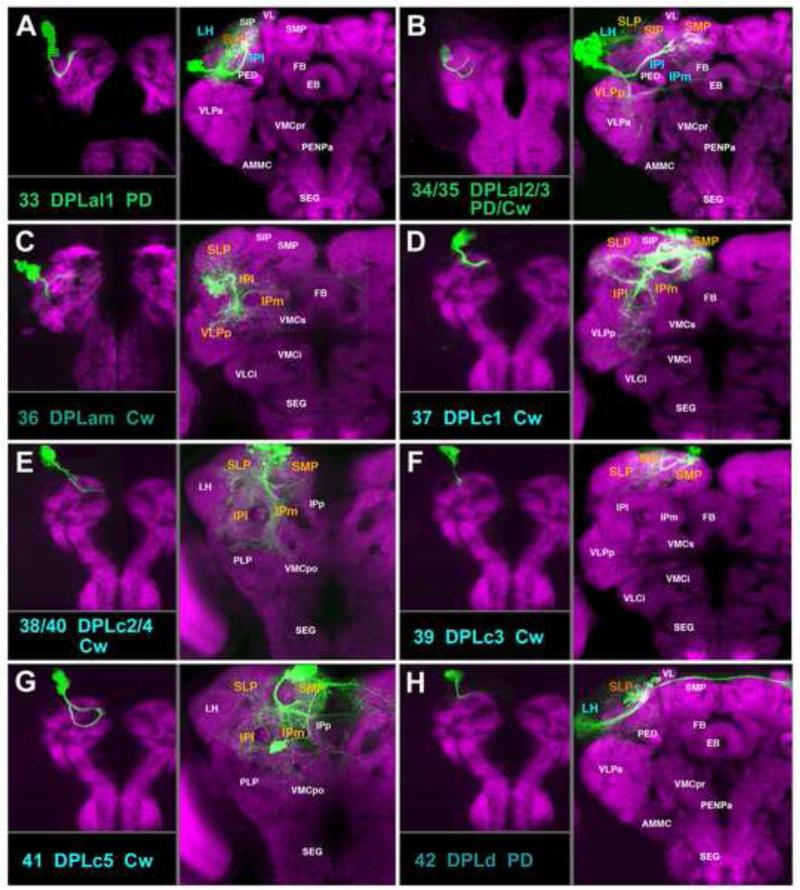

A-H: Clones representing lineages #33/DPLal1 to #42/DPLd of the DPL group in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 9.

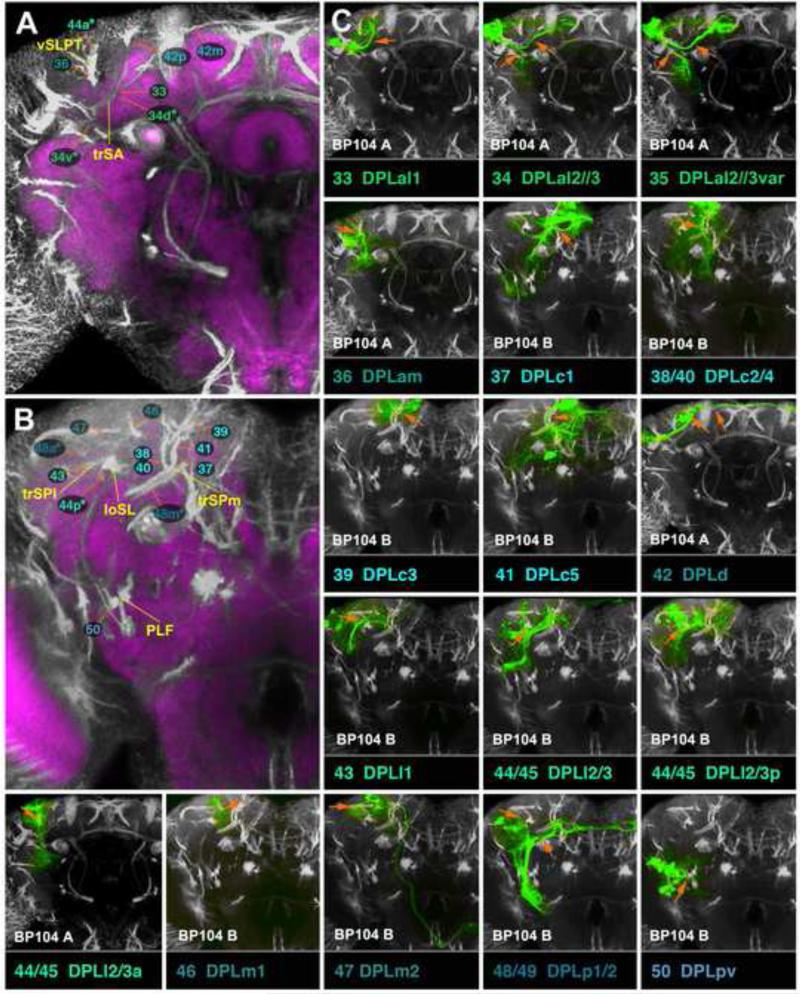

Clones representing lineages of the DPL groups in the adult brain. (A, B) z-projections show brain slices at an anterior level (ellipsoid body; A) and posterior level (lateral bend of antennal lobe tract). (C) z-projections of clones representing lineages of the DPL group. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.4. The lineage pair DPLl2/3 is represented by three panels in C. The first two of these (C44 DPLl2, C45 DPLl3) shows the clone registered to the posterior brain slice, to show association of the posterior HSAT with the obP fascicle (orange arrows; compare to panel B). In the third panel (C 45/DPLl3a), z-projection of the anterior hemilineage of DPLl3 is registered with anterior brain slice, showing entrypoint of anterior HSAT into dorsal SLP (orange arrow). For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 11.

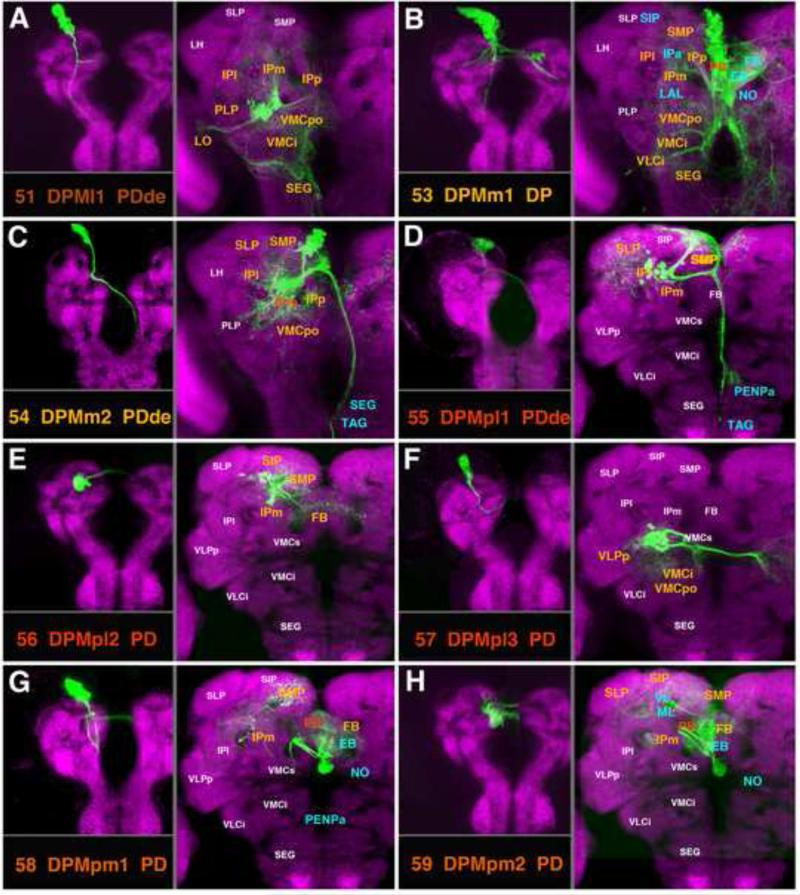

A-H: Clones representing lineages of the DPM group in the larval and adult brain. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 2. Bar: 50μm

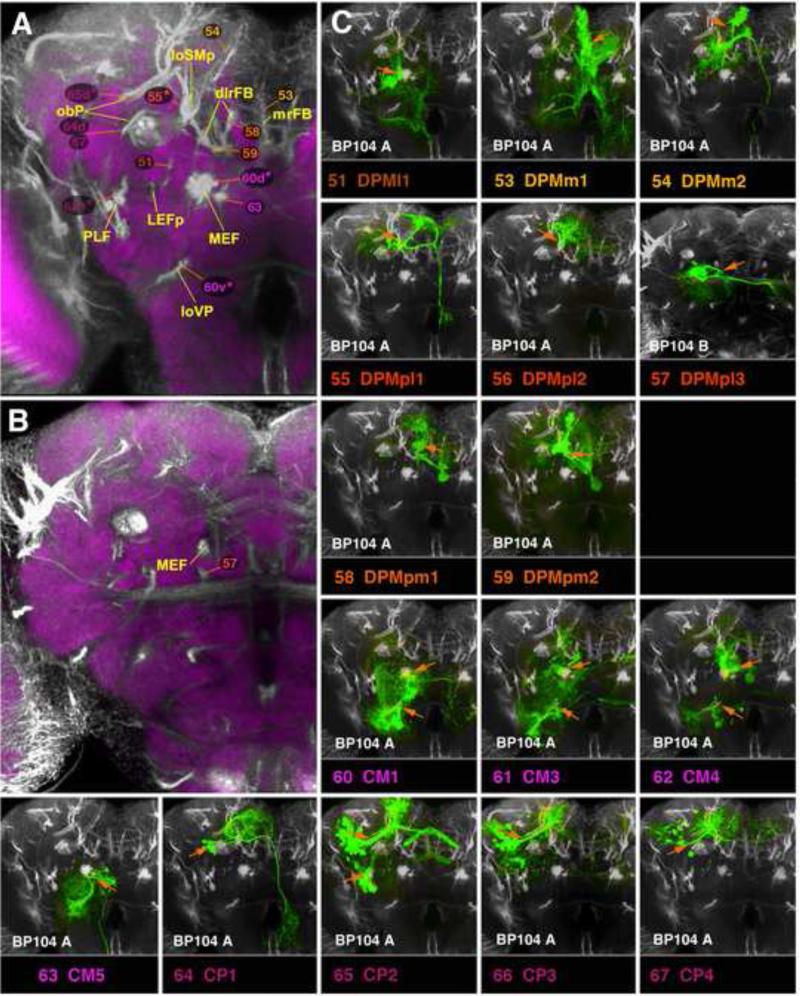

Figure 12.

Clones representing lineages of the DPM group in the adult brain. (A, B) z-projections show brain slices at a posterior level (lateral bend of antennal lobe tract; A) and central level (fan-shaped body, great commissure; B). (C) z-projections of clones representing lineages of the DPM group. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.4. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 14.

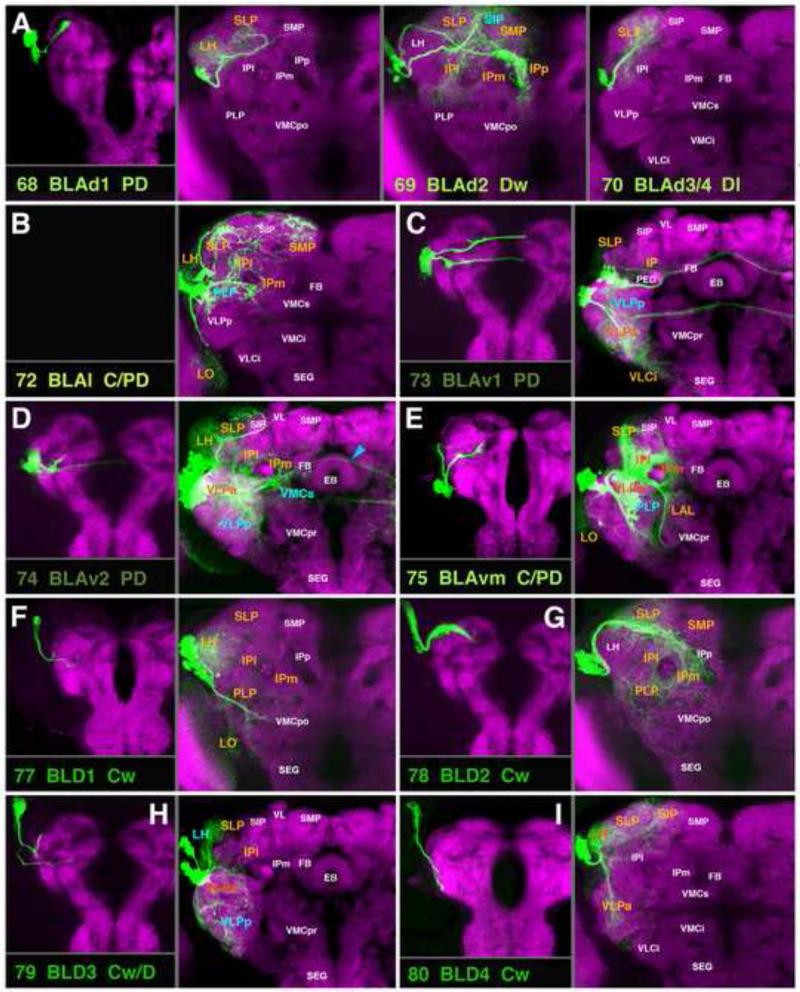

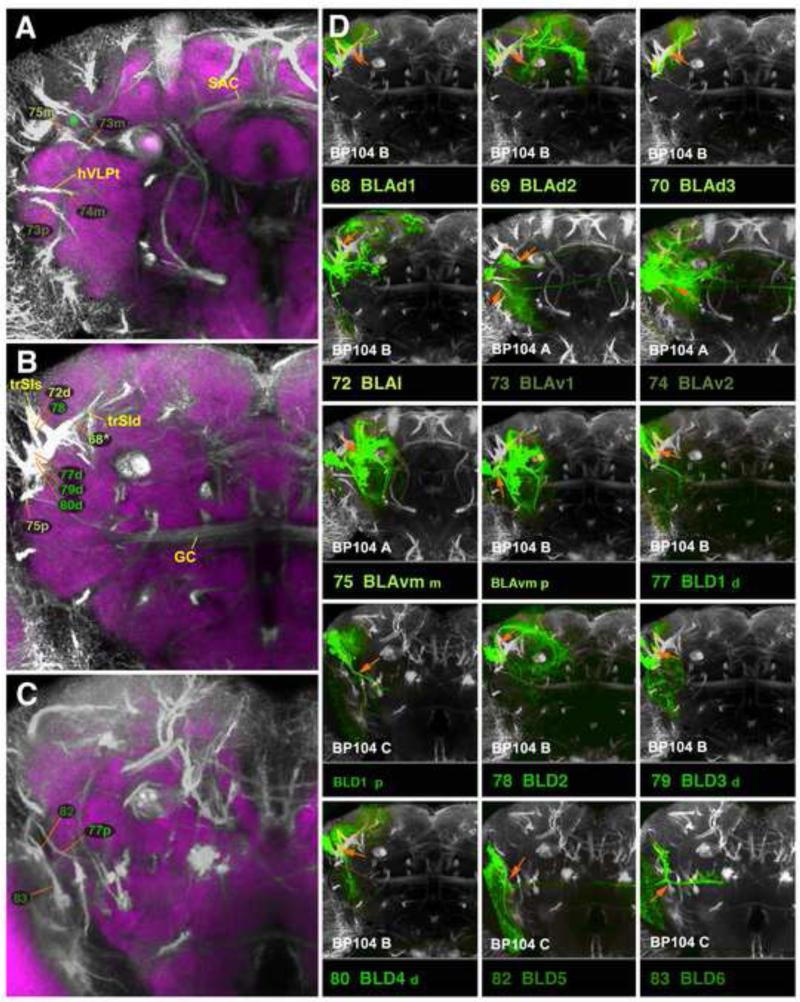

A-I: Clones representing lineages of the BLA group and lineages #77/BLD1-#80/BLD4 of the BLD group in the larval and adult brain. No larval clone for BLAl (B) was isolated. For the quartet BLAd1-4 (A) only one larval clone (panel A, left) is shown. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.2. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 15.

Clones representing lineages of the BLA and BLD group in the adult brain. (A-C) z-projections show slices of the brain at an anterior level (A; level ellipsoid body), central level (B; fan-shaped body and great commissure) and posterior level (C; lateral bend of antennal lobe tract). (D) z-projections of clones representing lineages of the BLA and BLD group. For description of how panels are made and displayed, see legend of Fig.4. The lineages BLAvm and BLD1are represented by two panels each in D. The first of the BLAvm panels (D75 BLAvm m) shows the clone registered to the anterior brain slice, to show projection of the medial HSAT of BLAvm between VLPa and SLP (orange arrow). In the second BLAvm panel (BLAvm p) the posterior HSAT of BLAvm along the surface of the VLPp is indicated (orange arrow). Similarly, separate entry points of the dorsal and posterior HSATs of BLD1 are shown in panels D77 BLD1 d and BLD1 p, respectively. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

Figure 17.

Clones representing lineages of the BLP and BLV group in the adult brain. (A-C) z-projections show slices of the brain at an anterior level (A; level ellipsoid body), central level (B; fan-shaped body and great commissure) and posterior level (C; lateral bend of antennal lobe tract). (D) z-projections of clones representing lineages of the BLP and BLV group. The lineage pairs BLVa1/2 (#89/90) and BLVa3/4 (#93/94) each are represented by two panels which show differences in location of cell body clusters. Lineages BLVp1 (#93) and BLVp2 (#94) are shown in two panels each. The left panels (D93 BLVp1 p; D94 BLVp2 p) shows the clone registered to the posterior brain slice, to show projection of the posterior HSAT of BLVp1/2 along the PLF fascicle (orange arrows). In the right panels (BLVp1 a, BLVp2 a) the anterior HSATs of these lineages, penetrating the VLPa, are shown (orange arrow). For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 1. Bar: 50μm

RESULTS

MARCM clones reveal the projection envelope of secondary lineages

We analyzed a total of 814 secondary clones, distributed over 499 brains. About half of the brains had a single clone, the other half had two or more (up to five; brains containing in excess of five clones were discarded). Aside from clonal labeling of individual secondary lineages, most brains also contained labeled-endings of afferents from the optic lobe and/or antennal nerve. All clones could be assigned to a specific secondary lineage (or lineage pairs) based on the entry point and trajectory of the SAT, defined as the fiber bundle that directly emerges from the cell body cluster and enters the neuropil (Fig.1A-B; BAlp4 clone assigned to BP104-labeled SAT). Given the number of clones analyzed, most secondary lineages were represented by more than one clone. We observed a wide range, with some lineages represented more than 20 times and others less than five times (average: ten clones per lineage; Table 2).

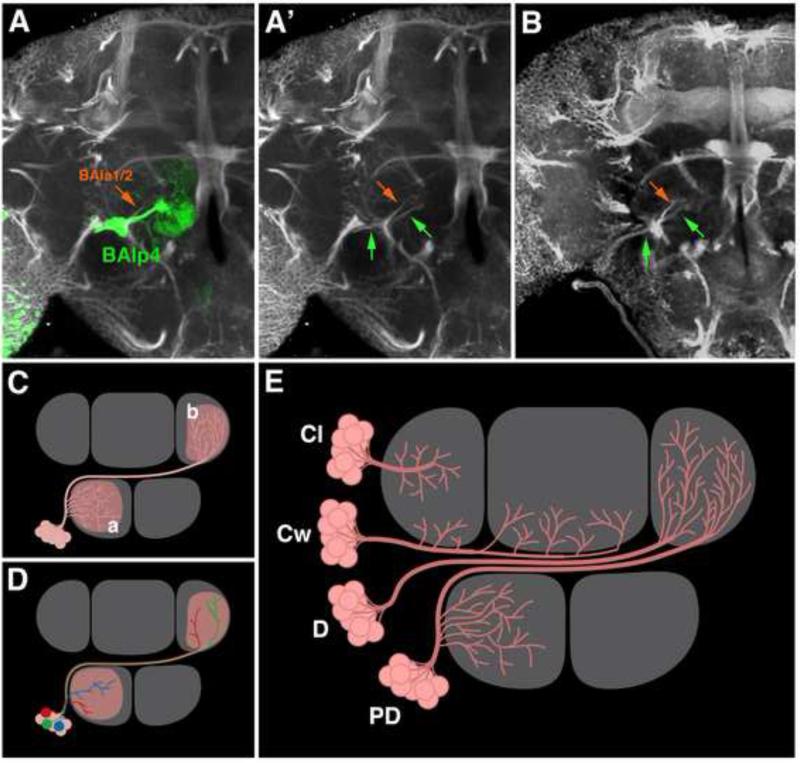

Figure 1.

Secondary lineages: SATs and projection envelope. (A-C) Assignment of clones to their respective secondary lineages is based on the entry point and trajectory of the SAT. Panel (A) shows a z-projection of an adult brain labeled with BP104 (white), containing a MARCM clone of the BAlp4 lineage (green). The SAT of BAla1/2 is shown in orange. Panel (A’) shows BP104 channel of the same z-projection. Green arrows in (A’-B) point at the SAT of the BAlp4 clone; as visible by green arrows in (A’), the SAT follows one of the BP104-positive tracts that can be followed back through metamorphosis to lineage BAlp4. Panel (B) represents a z-projection of the standard brain used in this paper, at an antero-posterior level corresponding to the one used for (A/A’). Note invariant pattern of BP104-positive fiber bundles in (A/A’) and (B) (green arrows: BAlp tract; red arrow: BAla1/2 tract). (C-D) Relationship of individual neurons and projection envelope. Schematic representation of a lineage (pink) with a projection envelope including compartments “a” and “b”. Individual neurons of the lineage could (all or in part) form arborizations throughout all compartments of the projection envelope [represented by red neuron in panel (D)], or could project to one or the other compartment [blue and green neuron in (D)]. (E) Classification of lineages based on the contour of projection envelope. Shown are four classes of lineages. In “PD” (“proximal distal”) lineages, a long segment of the SAT connects proximal to distal arborizations. In “C” (continuous) lineages, branches emerge at more or less regular intervals along the entire length of the SAT. Two subtypes of continuous lineages, local (“Cl”) and widefield (“Cw”), are illustrated. In “D” (“distal”) lineages, terminal arborizations are delimited to the distal end of the SAT. Bar: 25μm.

Table 2.

List of abbreviations of neuropil fascicles (left), compartments (center), and entry portals of lineage-associated tracts (right).

| Fascicles | Abbr. | Compartments | Abbr. | Entry portals | Abbr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior-dorsal commissure | ADC | Antennal lobe | AL | Anterior entry portal of the ML | ptML a |

| Antennal lobe commissure | ALC | Antenno-mechanosensory and motor center | AMMC | Anterior portal of the lateral horn | ptLH a |

| Antennal lobe tract | ALT | Anterior optic tubercle | AOTU | Anterior superior lateral protocerebrum portal | ptSLP a |

| Inner antennal lobe tract | iALT | Anterior periesophageal neuropil | PENPa | Antero-dorsal entry portal of the VLP | ptVLP ad |

| Medial antennal lobe tract | mALT | Bulb | BU | Dorrso-lateral superior ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP dls |

| Outer antennal lobe tract | oALT | Ellipsoid body | EB | Dorsal antennal lobe portal | ptAL d |

| Anterior optic tract | AOT | Fan-shaped body | FB | Dorsal spur portal | ptSP d |

| Anterior superior transverse fascicle | trSA | Inferior protocerebrum | IP | Dorso-lateral entry portal of the ML | ptML dl |

| Central protocerebral descending fascicle | deCP | Anterior IP | IPa | Dorso-lateral inferior ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP dli |

| Cervical Connective | CCT | Lateral IP | IPl | Dorso-lateral portal of protocerebral bridge | ptPB dl |

| Commisure of the lateral accessory lobe | LALC | Medial IP | IPm | Dorso-lateral vertical lobe portal | ptVL dl |

| Dorsal commissure of anterior subesophageal ganglion | DCSA | Posterior IP | IPp | Dorso-medial entry portal of the ML | ptML dm |

| Dorsolateral root of the fan-shaped body | dlrFB | Lateral accessory lobe | LAL | Dorso-medial portal of protocerebral bridge | ptPB dm |

| Fronto-medial commissure | FrMC | Lateral horn | LH | Dorso-medial ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP dm |

| Great commissure | GC | Mushroom body | MB | Dorso-medial vertical lobe portal | ptVL dm |

| Horizontal ventrolateral protocerebral tract | hVLPT | Calyx | CA | Lateral antennal lobe portal | ptAL l |

| Intermediate superior transverse fascicle | trSI | Medial lobe | ML | Lateral portal of calyx | ptCA l |

| Deep bundle of irSI | trSI d | Peduncle | PED/P | Lateral portal of the posterior lateral protocerebrum | ptPLP l |

| Superficial component of trSI | trSI s | Spur | SP | Lateral portal of the superior lateral protocerebrum | ptSLP l |

| Lateral ellipsoid fascicle | LE | Vertical lobe | VL | Medial portal of calyx | ptCA m |

| Anterior LE | LEa | Noduli | NO | Posterior inferior portal of the posterior lateral protocerebrum | ptPLP pi |

| Posterior LE | LEp | Posterior lateral protocerebrum | PLP | Posterior portal of superior lateral protocerebrum | ptSLP p |

| Lateral equatorial fascicle | LEF | Protocerebral bridge | PB | Posterior portal of the lateral horn | ptLH p |

| Anterior LEF | LEFa | Subesophageal ganglion | SEG | Posterior superior portal of the posterior lateral protocerebrum | ptPLP ps |

| Posterior LEF | LEFp | Superior protocerebrum | SP | Posterior ventro-medial cerebrum portal | ptVMCpo |

| Medial equatorial fascicle | MEF | Superior intermediate protocerebrum | SIP | Postero-lateral portal of superior lateral protocerebrum | ptSLP pl |

| Medial root of the fan-shaped body | mrFB | Superior lateral protocerebrum | SLP | Postero-medial portal of superior lateral protocerebrum | ptSLP pm |

| Median bundle | MBDL | Anterior SLP | SLPa | Ventral antennal lobe portal | ptAL v |

| Oblique posterior fascicle | obP | Posterior SLP | SLPp | Ventral entry portal of the VLCi | ptVLCi v |

| Posterior commissure of the posterior lateral protocerebrum | pPLPC | Superior medial protocerebrum | SMP | Ventral portal of calyx | ptCA v |

| Posterior lateral fascicle | PLF | Ventro-lateral cerebrum | VLC | Ventral portal of protocerebral bridge | ptPB v |

| External component of PLF | PLFe | Anterior VLC | VLCa | Ventral spur portal | ptSP v |

| Dorsolateral component of PLF | PLFdl | Inferior VLC | VLCi | Ventro-lateral antennal lobe portal | ptAL vl |

| Dorsomedial component of PLF | PLFdm | Lateral VLC | VLCl | Ventro-lateral inferior ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP vli |

| Ventral component of PLF | PLFv | Ventro-medial cerebrum | VMC | Ventro-lateral portal of calyx | ptCA vl |

| Posterior superior transverse fascicle | trSP | Anterior VMC | VMCa | Ventro-lateral superior ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP vls |

| Lateral trSP | trSPl | Inferior VMC | VMCi | Ventro-lateral vertical lobe portal | ptVL vl |

| Medial trSP | trSPm | Post-commissural VMC | VMCpo | Ventro-medial antennal lobe portal | ptAL vm |

| Sub-ellipsoid commissure | SuEC | Pre-commissural VMC | VMCpr | Ventro-medial ventro-lateral protocerebrum portal | ptVLP vm |

| Subesophageal-protocerebral system | SPS | Superior VMC | VMCs | Ventro-medial vertical lobe portal | ptVL vm |

| Superior arch commissure | SAC | Ventro-lateral protocerebrum | VLP | ||

| Superior commissure of the posterior lateral protocerebrum | sPLPC | Anterior VLP | VLPa | ||

| Superior lateral longitudinal fascicle | loSL | Posterior VLP | VLPp | ||

| Anterior loSL | loSLa | ||||

| Posterior loSL | loSLp | ||||

| Superior medial longitudinal fascicle | loSM | ||||

| Anterior loSM | loSMa | ||||

| Posterior loSM | loSMp | ||||

| Supra-ellipsoid body commissure | SEC | ||||

| Ventral fibrous center | VFC | ||||

| Ventral longitudinal fascicle | loV | ||||

| Intermediate loV | loVIa | ||||

| Lateral loV | loVLa | ||||

| Medial loV | loVMa | ||||

| Posterior-lateral loV | loVP | ||||

| Vertical posterior fascicle | vP | ||||

| Vertical tract of the superior lateral protocerebrum | vSLPT | ||||

| Vertical tract of the ventro-lateral protocerebrum | vVLPT |

Based on our analysis of SAT development (see accompanying paper by Lovick et al., 2013), 56 lineages defined in the late larva have SATs that can be individually followed within the neuropil throughout development (Table 2). Within this group, we could identify clones in all cases except one, DALv3. The projection pattern of DALv3 has been characterized previously (Kumar et al., 2009a). A second group of 30 lineages (e.g., BAmas1/2; DALcm1/2) have SATs that form pairs or form a quartet (the four BLAd lineages). In these cases, it is not possible to predict whether the two lineages forming the pair (or quartet, in the case of BLAd1-4) will have projection envelopes that are identical or different. Within the group of 30 lineages, four pairs (BAmas1/2, DPMpl1/2, CP2/3, BLP1/2) were obtained that had clones with significantly different arborization patterns. This suggests that paired lineages with identical SATs form distinct arborization patterns (e.g. BAmas1/2; Fig.4C11-12). In three pairs within this group (DPLl2/3, BLVa1/2, BLVa3/4) the patterns were very similar, but the trajectory of part of the SATs differed consistently (e.g. DPLl2/3 in Fig.10B-F). In the case of the BLAd1-4 quartet we isolated three different classes of clones. In the eight remaining pairs (BAla3/4, DALcm1/2, DAMd2/3, DAMv1/2, DPLal2/3, DPLc2/4, DPLp1/2, BLP3/4) only one type of clone was recovered, suggesting that these lineages form identical arborization patterns. Alternatively, it is possible that we could recover clones for only one member of the pair, which is unlikely given the fact that an average of ten clones per lineage was obtained for all other lineages.

A significant fraction of lineages form more than one SAT. In cases where these tracts separate from the very beginning where axon tracts enter the neuropil we tentatively assume that they represent two separate hemilineages (or sublineages, in case of type II lineages); ultimate proof for their status as “true” hemilineages would have to come from experimental studies such as those done for thoracic lineages (Truman et al., 2010) or a small number of engrailed-positive brain lineages (Kumar et al., 2009a). As described in the accompanying paper by Lovick et al. (2013), hemilineages move apart during metamorphosis in a number of cases. GFP labeled clones provided confirmation for this movement of hemilineages. All except one (BLAvm) of the lineages in question, notably BAlc, BAmd1, DPLl2/3, CP2/3, BLAl, BLAv1, BLVp1/2, were represented by more than five clones; for BLAvm we have three clones. In all cases, GFP labeling invariably marked both hemilineages simultaneously, whereas other, independent lineages could be represent by a clone in some cases, but not in others. In case of several lineages for which the movement of SATs and HSATs was difficult to follow (BLD1, BLD3, BLAl, DPLc5), the existence of two separating hemilineages was confirmed. In three cases, BAmd2, DPLm2 and DPMl1, the analysis of MARCM clones made it possible to identify the proper lineage in the adult brain. Thus, the SAT of BAmd2 cannot be followed beyond P24 because its entry and proximal SAT is masked by the arrays of antennal afferent surrounding it. A clone with the characteristic SAT entry point and crossing in the antennal lobe commissure confirmed BAmd2 for the adult brain. The same applied for DPMl1, whose characteristic descending SAT is not visible beyond P24. DPLm2 represents a unique case where the MARCM clone united two clusters of cells that had been previously considered to represent two separate lineages. Thus, in our larval analysis, DPMl2 with a characteristic centrifugal axon bundle projecting to the ring gland was considered as a separate lineage (Pereanu et al., 2006). MARCM clones showed that the ring gland associated axons form part of DPLm2 instead.

Classification of lineages based on the geometry of their projection envelope

The GFP-labeled clone, when superimposed on a backdrop of an adult brain labeled with a neuropil marker (anti DN-cadherin; from here on called DN-cad) or axonal marker (anti-Neurotactin, from here on referred to as BP104), allows one to map the neurite arborizations of all neurons of a single lineage (the “projection envelope”) with respect to brain neuropil compartments (Fig.1C). Note that the relationship between the projection envelope of a lineage and the projection of an individual neuron forming part of a lineage is not simple (Fig.1D). For example, when an envelope includes two neuropil compartments, a and b, there are two possibilities: (1) each individual neuron may also have arborizations in a and b (Fig.1D, red neuron); or alternatively, a subset of neurons might only project to a or to b (Fig.1D, green neuron and blue neuron, respectively). Nonetheless, documenting the projection envelope for each lineage represents a significant step towards describing brain circuitry. In this paper we will provide an overview of the projection envelopes for each lineage of the supraesophageal ganglion, following the same topology-based ordering used in the accompanying paper (Lovick et al., 2013).

Representative clones and lineage restricted markers used in previous studies suggested that, aside from their topology (spatial relationship of a SAT entry point and projection relative to neuropil tracts and compartments), lineages can also be classified according to the “geometry”, defined as the distribution of axonal/dendritic branches relative to the main SAT (Larsen et al., 2009). It should be noted that unlike vertebrate neurons, where dendritic branches connected to the cell body are separated from axonal branches, insect neurons have a neurite tree on which dendritic and axonal branches are frequently intermingled (Hartenstein et al., 2008; Watson and Schürmann, 2002). The degree of intermingling, nonetheless, varies for different neurons and presumably different lineages. For example, in the case of the well characterized lineages of antennal lobe (AL) projection neurons (e.g. BAmv3, BAlc, and BAla1), dendritic branches are concentrated along the proximal region of the SAT in the AL; whereas axonal branches are close to the distal tip of the SAT in the calyx (CA) and lateral horn (LH). The long segment of the SAT connecting proximal to distal, called the antennal lobe tract, is devoid of branches. Lineages with this geometry were classified as “PD” (“proximal distal”) lineages (Larsen et al., 2009; Fig.1E). In other lineages, branches emerged at more or less regular intervals along the entire length of the SAT (“continuous” or “C” lineages); or were all concentrated at its distal tip (“distal” or “D” lineages). Further analysis using fluorescent reporters differentially localized to either dendritic or axonal branches (e.g. UAS-ICAM5ΔECD::mCherry and UAS-GFP-KDEL; Nicolai et al., 2010 and Okajima et al., 2005, respectively) can be used to compare their distribution in the C, D, and PD lineages.

In the following, clones representing individual lineages will be described in the order established for the lineage tracts in the accompanying paper (Lovick et al., 2013). Clones are documented in three sets of figures. In one set of figures, we show z-projections of clones with spatial respect to the BP104-labeled scaffold of neuropil fascicles, starting with lineages entering the anterior brain surface (BA: Fig.4; DAL and DAM: Fig.6), followed by those of the dorsal surface (DPL: Fig.9), posterior surface (DPM, CM, CP: Fig.12), and finally, lateral surface (BLA, BLD, BLP, BLV: Figs.15 and 17). These figures illustrate the identification of clones with their corresponding lineages. The second set of figures show z-projections of clones registered to DN-cad-labeled brain slices, in the order as described above (BA: Figs.2, 3; DAL: Fig.5; DAM: Fig.7; DPL: Figs.8, 10; DPM: Fig.11; CM and CP: Fig.13; BLA and BLD: Fig.14; BLP and BLV: Fig. 16), illustrating the projection envelopes of all lineages. In all panels of all these figures, the adult MARCM clone is paired with a larval clone (MARCM or Flp-out; see Materials and Methods for more details) representing the corresponding lineage, documenting the similarity in SAT projection patterns between larval and adult stages. The third set of figures (supplementary figures S1-S5) show schematic renderings of SATs and main locations of terminal arborizations for all lineages. Lineages sharing important aspects of their projection are combined together, such that Fig.S1 shows lineages with SATs connecting ventral to dorsal compartments, Fig.S2 has lineages interconnecting ventral compartments, lineages in Fig.S3 are associated strongly with the central complex and mushroom body, Fig.S4 presents lineages of the superior protocerebrum projecting ventrally (including the subesophageal ganglion and thoracico-abdominal ganglion), and Fig.S5 shows lineages interconnecting dorsal compartments of the brain.

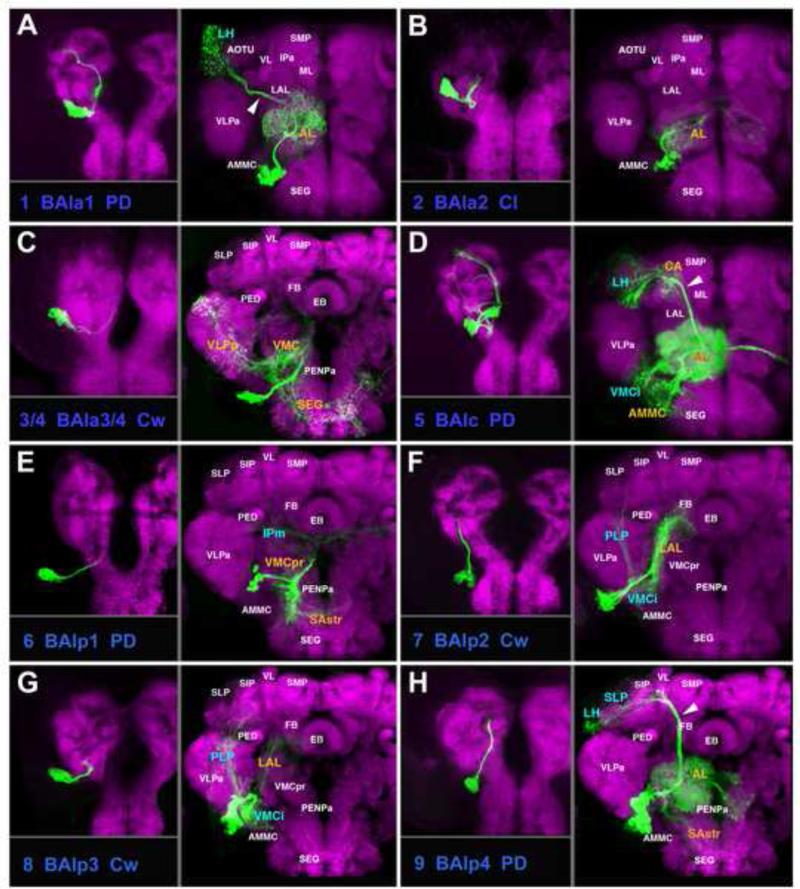

Figure 2.

A-H: Clones representing lineages of the BA group (#1/BAla1 to #9/BAlp4) in the larval and adult brain. This and the following figures 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 16 are designed in the same manner: Each lineage is represented by a panel showing z-projection of a larval brain hemisphere on the left, and of an adult hemisphere on the right. Number and abbreviation of the lineage is given at the bottom left of the panel. Next to the abbreviation, the type of lineage (C, P, PD) is indicated. Images were generated by registering full z-projection of clones (that is, a z-projection containing all sections of a stack showing GFP label) to a z-projection of a “slice” of the DN-cad-labeled standard brain, as described in the Materials and Methods section. DN-cad visualizes neuropil compartments, annotated by white letters on part of panels showing adult brain. Compartments receiving major innervation by the lineage shown in a given panel are annotated by colored letters. Innervated compartments contained within the brain slice shown by DN-cad are in orange; compartments located significantly anterior or posterior to the slice shown appear in blue letters. For example, #1/BAla1 (A) is represented by a clone registered to an anterior brain slice [level optic tubercle (OTU)/mushroom body medial lobe (ML)]. Major compartments visible at that level are annotated by small white letters. Within this slice, only the antennal lobe is innervated by BAla1; it is annotated by orange letters. BAla1 projects postero-laterally towards the lateral horn, which is located in a slice posterior to the one shown. The lateral horn (LH) is therefore annotated by blue letters. For alphabetical list of all abbreviations see Table 2. Bar: 50μm.

BA Lineages

The BA group comprises PD, C, and D lineages whose neurons are mostly associated with the ventral brain compartments (Figs.2-4; Figs.S1, S2). Four PD lineages, BAla1 (#1; Fig.2A), BAlc (#5; Fig.2D; dorsal hemilineage), BAlp4 (#9; Fig.2H), and BAmv3 (#17; Fig.3H) include all of the projection neurons connecting the antennal lobe (AL) and superior protocerebrum. After forming proximal (dendritic) branches in the AL, neurites of all neurons of these lineages converge and exit the AL posteriorly as the common antennal lobe tract (ALT; yellow arrows in Fig.4C1, C5, C9, C17). Axons of BAla1 soon leave this bundle and directly head for the lateral horn (LH) via the medial-lateral ALT (mlALT; Fig.2A, white arrowhead; Fig.S1). The remaining three SATs (#5, 9, 17) stay together as the medial ALT (mALT) which continues dorso-posteriorly towards the calyx (CA), before bending laterally towards the LH (arrowheads in Figs.2D, H; 3H; Fig.S1). As published previously (Das et al., 2013), the lineage BAlp4 (#9) forms proximal branches that not only reach the AL, but also part of the ventrally adjacent subesophageal ganglion (abbreviated as SAstr in Fig.2H; possibly a domain with gustatory input), and projects to the superior lateral protocerebrum, rather than the CA and LH (Fig.2H; Fig.S1). The ventral hemilineage of BAlc (#5v) includes complex projection neurons which are mostly unrelated to the AL. They project ventro-posteriorly, forming the loVI fascicle (Fig.4A, B; Fig.S2; see accompanying paper by Lovick et al., 2013). Proximal branches of the loVI arborize in the antenno-mechanosensory and motor center (AMMC; Fig.2D). Distally, this tract forms a T-junction, with one branch projecting laterally into the inferior domain of the ventro-lateral cerebrum (VLCi) and the other branch crossing the midline via the great commissure to reach the contralateral inferior ventro-lateral cerebrum (VLCi; Fig.2D; Fig.S2). In addition, a thin branch continues dorso-laterally towards the LH; this constitutes the lateral antennal lobe tract (not resolved in Fig.2D; Fig.S1).

Two additional PD lineages, BAmas1 and BAmas2 (#11, #12; Fig.3B, C), form a connection between the tritocerebrum and the superior medial protocerebrum and mushroom body, respectively. Thus, proximal branches of BAmas1/2 form dense arborizations in the tritocerebrum. The tritocerebrum is also called, in a segment-neutral manner, anterior peri-esophageal neuropil (PENPa; Kumar et al., 2009b; Pereanu et al., 2010; Fig.3B, C). The SATs of BAmas1/2 then project dorsally through the median bundle and reach the superior medial protocerebrum (Fig.4C11, C12). Short distal terminal branches of BAmas2 end here; BAmas1 bends laterally and forms terminal arbors in the dorsal lobe of the mushroom body (Fig.3B, C; Fig.S1).

BAmd1 (#13) and BAmd2 (#14) are complex lineages with commissural tracts. The dorsal HSAT of BAmd1 (#13d) projects medially directly behind the mushroom body medial lobe and crosses in the fronto-dorsal commissure; terminal branches innervate the medial lobe of both hemispheres, as well as the anterior inferior protocerebrum on the ipsilateral side (Figs.3D; 4A, C13; Fig.S3). The ventral HSAT of BAmd1 (#13v) projects diagonally through the AL, crosses in the antennal lobe commissure (ALC), and then bifurcates into a dorsal branch directed towards the superior lateral protocerebrum (SLP) and a ventral branch with a large terminal domain in the lateral accessory lobe (LAL), ventro-medial cerebrum (VMC), and subesophageal ganglion (SEG) (Figs.3D; 4C13; Fig.S4). BAmd2 (#14) enters near the midline, in between the antennal lobes of either side. The SAT bifurcates, with one branch crossing in the antennal lobe commissure (Fig.4C14; Fig.S2). The ipsi- and contralateral branches project in a nearly symmetrical fashion postero-laterally, innervating the ventrolateral cerebrum (VLCi) and posterior lateral protocerebrum (PLP) (Fig.3E; Fig.S2).

Another complex PD lineage, BAmv1 (#15), is marked by the per-Gal4 driver line and has been documented previously (Spindler and Hartenstein, 2010; Spindler and Hartenstein, 2011). The large proximal SAT of BAmv1 (#15p) forms a major component of the loVM that passes underneath the AL into the ventromedial cerebrum (VMC) (Fig.4B, C15). The SAT splits into three major branches: one curving dorsally and medially towards the central complex; the second continuing posteriorly into the VMC; the third one extending laterally towards the ventro-lateral protocerebrum (VLPa/p) (Fig.S2). Terminal branches innervate the lateral accessory lobe (LAL), the fan-shaped body (FB), the noduli (NO), the VMC, and the VLP (shown in orange letters in Fig.3F; Fig.S2). BAmv2 (#16) has a distally branching (type D) single SAT that accompanies BAmv1 in the loVM fascicle (#15; Fig.4B, C16). At the level of the great commissure the tract turns medially and dorsally and splits into an ipsilateral and contralateral component that innervate the VMC surrounding the great commissure (Fig.3G; Fig.S2).

BAlp2 and BAlp3 (#7, #8) are lineages with long C-type SATs that contribute to the lateral component of the ventral longitudinal fascicle (loV; Fig.4B, C7, C8). The BAlp2 tract splits into a dorsal branch with dense terminal fibers in the lateral part of the LAL compartment and a posterior branch that continues posteriorly (Fig.2F), innervating VLCi and PLP (Fig.S2). BAlp3 has a single tract that follows BAlp2 towards the VLCi and PLP (Fig.2G; Fig.S2).

BAla3/4 (#3/4) and BAlv (#10) have C-type SATs, and BAlp1 (#6) has a PD-type SAT that enter from a position lateral of the AL (Fig.4A, B, C). The first three of these lineages (#3/4, 6) project medially towards the ventromedial cerebrum: BAlp1 crosses the loVM fascicle at its dorsal surface and BAla3/4 at its ventral surface (Fig.4A, B, C3/4; C6). BAlp1 has terminal arborizations within the VMC compartment, with ventral branches reaching into the SEG/PENPa (Fig.2E; Fig.S2). BAla3, marked by the driver en-Gal4 (Kumar et al., 2009b), has widespread terminals in the VMC (Fig.2C; Fig.S2). BAla4 extends alongside BAla3; only a single type of clone was recovered for the BAla3/4 pair. BAlv (#10) contacts the inferior VLC (VLCi) from ventral (Fig.4B, C10) and has terminal fibers confined to the VLCi and neighboring AMMC (Fig.3A; Fig.S2).

DAL Lineages

Projections of the DAL lineages are predominantly associated with the medial and vertical lobes of the mushroom body (ML, VL), the central complex, and the adjacent protocerebral compartments (AOTU, SMP, IPa). Most of the DAL lineages, including the DALcl1/2, DALcm1/2, DALd, DALl1, and DALv1-3 are PD lineages with long tracts, many of which are commissural.

DALcl1 and DALcl2 (#18, #19; Figs.5A, B; 6C18, C19), located laterally of the mushroom body vertical lobe (VL), form a pair of PD lineages associated with the anterior optic tubercle (AOTU), central complex, and adjoining compartments; each one consists of two hemilineages whose diverging HSATs in a “pincer-like” manner enclose the mushroom body spur (SP; Fig.6A, C18, C19). Dense proximal branches of DALcl1 and DALcl2 innervate the AOTU (Fig.5A, B; Fig.S3). The ventral hemilineage tract of DALcl1 (#18v) passes underneath the SP and continues medially, crossing the midline in the subellipsoid commissure (SEC; Fig.5A; Fig.S3). Terminal arborizations of this tract end bilaterally in the LAL. In addition, on each side, a posteriorly directed branch of DALcl1v projects along the MEF fascicle towards the posterior VMC compartment (VMCpo; Figs.5A; 6A). The ventral DALcl2 hemilineage projects as part of the lateral ellipsoid fascicle (LEa) towards the central complex (Figs.5B, 6A, C19; Fig.S3). Dorsal hemilineage tracts of DALcl1/2 (#18d/19d) curve over the dorsal surface of the spur (SP) and peduncle. DALcl1 projects in a fairly restricted manner to the bulb (BU, a small compartment relaying information towards the ellipsoid body, EB; Fig.5A; Fig.S3); DALcl2 projects in a more widespread manner, including the BU, adjacent LAL, IP, and SMP (Fig.5B; Fig.S3).

DALd (#22) and the DALcm1/2 pair (#20/21) are located medially of the mushroom body vertical lobe (VL; Figs.5C, D; 6B, C20-22). DALd (#22) constitutes a PD lineage with dense proximal arborizations in the IPa and the superior intermediate protocerebrum (SIP), which surround the medial lobe and vertical lobe, respectively (Fig.5D; Fig.S4). The SAT of DALd (#22) projects ventro-medially, crossing the peduncle, and continues as part of the deCP tract (Fig.6B, C22). Distal arborizations are found in the VMC and SEG (Fig.5D; Fig.S4). The lineage pairs DALcm1/2 each have two PD hemilineages with very similar projection patterns in all recovered clones. This suggests that both lineage pairs possess the same projection envelope. The medial hemilineage tracts pass behind the medial lobe (ML) and enter the fronto-medial commissure (FrMC; Fig.6C20-21; Fig.S3). In terms of projection, arbors are found bilaterally in the ML and the surrounding IPa, AOTU, SIP, and SMP compartments (Fig.5C; Fig.S3). The ventral hemilineage tracts of DALcm1/2 pass through the elbow formed by the VL and peduncle before turning ventrally (Fig.5C; Fig.S4). This projection initially forms part of the deCP, but then separates from the fascicle, extending into the ventral brain as a separate, loose bundle. The proximal terminal branches are found throughout the anterior domain of the SMP, IP, and the distal branches in the VMC (Fig.5C; Fig.S4).

Two DAL lineages, DALl1 and DALl2 (#23, #24), are located laterally of the DALcl group, flanking the anterior VLP compartment (VLPa; Figs.5E, F; 6C23, C24). DALl1 (#23) is a PD lineage with a conspicuous recurrent projection. The SAT projects posteriorly, splits into a ventral branch with arborizations in the PLP and adjacent lobula (LO), and a recurrent branch that turns dorsally and anteriorly forming arborizations in the anterior SLP, IP and AOTU (Figs.5E, 6B; Fig.S5). DALl2 (#24; Fig.5F) represents a C lineage. Its short SAT projects into the anterior VLPa where it splits into several groups of terminal arborizations filling much of the anterior and posterior VLP compartment (VLPa/p). A few “outlier” branches continue dorso-medially into the IP and SMP compartments (Fig.5F).

The DALv group, comprising three PD lineages with commissural connections, is located ventral of the spur. DALv1 (#25) has a long unbranched proximal SAT that forms the LEFa fascicle (Figs.5G; 6B, C25) and then bifurcates into an ipsilateral and commissural branch that crosses in the great commissure. Terminal arborizations fill the ipsilateral and contralateral posterior VLP and neighboring VLCi compartments (Fig.5G). Ipsilaterally, there is a projection to the posterior SEG (not shown). DALv2 (#26) and DALv3 (#27) are marked by the expression of per-Gal4 and en-Gal4, as described previously (Kumar et al., 2009b; Spindler and Hartenstein, 2010; Spindler and Hartenstein, 2011); proximal SATs form the lateral ellipsoid fascicle (LEa) (Figs.5H; 6A, C26-27; 7A). The DALv2 (#26) lineage forms large proximal arborizations in the BU, as well as distal, ring-shaped branches of the EB (Fig.5H; Fig.S3), that represent the ring (R)-neurons of the EB (Spindler and Hartenstein, 2011). Additional terminal arborizations of DALv2 are found in the adjacent LAL and IPa (Fig.5H). DALv3 (#27), marked by the expression of en (Kumar et al., 2009b), projects alongside DALv2 in the LEa fascicle, which then splits into a dorsal and ventral commissural branch (Fig.6A, C27; Fig.S3). DALv3 terminal arborizations are confined to the ipsilateral and contralateral inferior protocerebrum (IPa/m) and the SMP (Fig.7A; see Kumar et al., 2009b for detail).

DAM Lineages

The small group of DAM lineages is located in the anterior dorso-medial cortex and has arborizations predominantly associated with the SMP/SIP and adjacent IPm/IPa compartments. DAMd1 (#28), a PD lineage with a unique recurrent commissural projection, first crosses the midline in the anterior dorsal commissure (ADC; Figs.6B, C28; 7B). It forms profuse arborizations in the contralateral SMP, SIP, and IPa; and crosses back via the fronto-medial commissure (FrMC) to form distal arbors in the ipsilateral SMP and IPa (Figs.6B, C28; 7B; Fig.S5). The DAMd2/3 pair (#29/30) comprises large C-type lineages (Figs.6B, 7C). Among the clones recovered for this pair, only a single type of projection envelope could be observed. The DAMd2/3 tract forms the anterior longitudinal superior medial fascicle (loSMa), continuously giving off terminal arborizations throughout the SIP, SMP, and IPm compartments (Figs.6B, C29-30; 7C; Fig.S5). Posteriorly, projections of DAMd2/3 extend ventrally to fill regions of the ipsilateral and contralateral VMCpo (Fig.7C; Fig.S5). The DAMv1/2 (#31/32) paired lineages also possess an indistinguishable projection envelope. The short SAT enters the SMP from anterior (Fig.6B, C31-32) and splays out into dense terminal arborizations, filling much of the SMP compartment (Fig.7D; Fig.S5).

DPL Lineages

DPL lineages predominantly innervate the lateral domains of the superior and inferior protocerebrum. Five lineages, DPLal1-3, DPLam, and DPLd represent the anterior subgroups, located dorso-laterally of the anterior optic tubercle (AOTU). DPLal1-3 (#33-35) are PD lineages recognizable by their crescent shaped SATs which form the anterior transverse fascicle of the superior protocerebrum (trSA; Figs.8A, B; 9A, C33-35; Fig.S5). Proximal arborizations of DPLal1 (#33) fill the deep regions of the SLP, LH, and the adjacent lateral IP (IPl); distal arbors innervate the dorso-anterior SLP (Fig.8A; Fig.S5). The DPLal2/3 (#34/35) pair has an indistinguishable projection envelope, each with two hemilineages (Figs.8B; 9C34, C35). The dorsal hemilineage (#34/35d) resembles DPLal1 (#33), forming part of the trSA (Fig.9A), but arborizing more widely than DPLal1 in the LH, SIP, SLP, SMP, and much of the IP (IPm/l, Fig.8B). The ventral HSAT forms projections in the medial IP and the adjacent posterior VLP (VLPp) (Fig.8B; Fig.S5). We recovered one clone where the two HSATs extended at a moderate distance from each other (Fig.8C); this could represent a random variant, or indicate that DPLal2/DPLal3 do differ in regard to their exact HSAT pathfinding. DPLam (#36) is a C-type lineage marked by the expression of engrailed and has been described previously (Kumar et al., 2009b). Projecting its single SAT ventro-posteriorly via the vSLPT fascicle (Figs.8C, 9A, C36), DPLam arborizes widely in the anterior SLP and the central part of the IPl/m and the VLPp (Fig.8C; Fig.S4). DPLd (#42) forms sparse proximal arborizations in the SIP and part of the adjacent SLP (Figs.8H, 9C42). The lineage has two HSATs, a medial one crossing the midline in the anterior-dorsal commissure (ADC) and projecting to the contralateral SIP (#42m; Figs.8H, 9A), and a posterior one that extends posteriorly along the anterior part of the loSL fiber system, forming terminal arborizations in the LH and lateral SLP (#42p; Figs.8H; Fig.9C42; FigS5).

The remainder of the DPL group, including DPLc1-5, DPLl1-3, DPLm1-2, DPLp1-2, and DPLpv are located in the posterior brain cortex. DPLc1-5 (#37-41; Fig.8D-G) enter through a common portal located at the junction between the SLP and SMP compartments (Fig.9B; C37-41) and have arborizations focused on the superior and inferior protocerebrum. DPLc1 (#37) is a C lineage with a characteristic crescent-shaped tract that forms part of the medial trSP fiber system (trSPm, Figs.8D; 9B, C37). Arborizations fill much of the SLP/SMP and the posterior part of the IPl/m (Fig.8D; Fig.S5). DPLc2/4 (#38, #40) is a C-type lineage pair that also forms part of the trSP fascicle (Fig.9B, C38-40). Unlike DPLc1, DPLc2/4 do not curve dorso-medially into the more anterior and dorsal part of the SMP; rather the pair remains close to the IPl/m, filling the compartment with widespread terminal arborizations and additional branches in the deep SLP/SMP compartments (Fig.8E; Fig.S5). DPLc3 (#39), another C-type lineage, has a short, anteriorly-directed SAT and arborizes in the central parts of the SLP, SIP, and SMP (Fig.8F; Fig.S5). DPLc5 (#41) possesses two hemilineages (#41a/p) which, in the adult are spaced relatively far apart from one another. The anterior hemilineage produces a curved SAT that enters alongside DPLc1-4 (Fig.9B, C41), extending antero-medially into the anterior SMP and part of the SLP; its dense terminal arborizations fill this compartment and the adjacent domains of the IP (Fig.8G; Fig.S5). The posterior DPLc5 hemilineage (#41p) is located at the ventro-posterior brain surface; the HSAT projects antero-dorsally, joining the loSM fascicle and crossing the midline in the ADC commissure (Fig.9C41). Terminal arborizations overlap with those of the anterior hemilineage in the SMP and IPm (Fig.8G).

DPLl1 (#43) and DPLl2/3p (#44/45p) enter the postero-lateral neuropil surface at the junction between the SLP/LH (Fig.9C43-45). The DPLl2/3p pair projects anteriorly, forming the loSL fascicle (Fig.9B). From the loSL fascicle, terminal branches sprout off and innervate the superior brain compartments (LH, SIP, SLP, and SMP) and ventrally directed branches also reach into the PLP, VLPp, and IPl (Fig.10B, E, F; Figs.S4, S5). While the DPLl2/3p hemilineages innervate identical compartments, they have distinct fasciculation patterns. Only one of the hemilineages, DPLl2p (#44p), forms a tight tract; fibers of the other hemilineage (DPLl3p, #45p) are more loosely aggregated (Fig.10E, F). This same characteristic holds true for the anterior hemilineages (#44/45a). As described in detail in the accompanying paper (Lovick et al., 2013), the anterior hemilineage tracts of DPLl2/3 (#44/45a) shift forward during metamorphosis and enter the anterior surface of the SLP (Fig.9A, C44, C45); they project ventrally into the upper part of the VLPp compartment (Fig.10C,D; Fig.S4). In contrast to DPLl2a (#44a), which forms a thin, compact tract with dense endings in a narrowly defined subdomain of VLPp (Fig.10C), DPLl3a (#45a) axons form a loose tract and extend diffuse terminal arborizations along their entire trajectory from the SLP to the VLPp (Fig.10D). DPLl1 (#43) enters the brain at the same point as DPLl2/3 (Fig.9B, C43), but sends its tract medially via the trSP fascicle, arborizing in the posterior SLP/SMP; a lateral branch innervates the LH/PLP (Fig.10A; Figs.S4, S5).

DPLm1 and DPLm2 (#46, #47; Fig.10G, H) are located lateral of the DPLc cluster, dorsal of the mushroom body calyx. DPLm1 (#46) is a C-type lineage and projects anteriorly in the SLP (Fig.9B, C46), producing branches in the SLP as well as the adjoining IPl/ SIP compartments (Fig.10G; Fig.S5). DPLm2 (#47) also innervates the SLP and adjacent IP; in addition, it sends a short SAT laterally (Fig.9B, C47) to form a terminal arbor in the lateral horn (LH; Fig.10H; Fig.S5). A long, thin fiber bundle of DPLm2 leaves the brain and projects to the ring gland (Fig.10H, arrowhead).

For the pair DPLp1/2 (#48/49), we were only able to isolate a single clonal type (Fig.10I). The paired tract enters the postero-lateral neuropil surface at the base of the lateral horn. A long, medial branch extends in the oblique posterior (obP) fascicle, across the peduncle and the brain midline, forming terminal arborizations along its trajectory in the posterior IP/SLP of both hemispheres (Figs.9C48, C49; 10I; Fig.S4). The anteriorly-directed HSAT of DPLp1/2 penetrates into the LH and forms profuse terminal branches in this compartment (Figs.9B; 11I; Fig.S4). A massive projection of DPLp1/2 is directed ventrally (#48v) along the vertical posterior tract (vP) into the PLP and posterior VLCi compartments (Fig.10I; Fig.S4). The posterior-most of the DPL lineages, DPLpv (#50) enters the posterior neuropil surface ventro-laterally; its SAT follows the postero-lateral fascicle anteriorly (PLF; Fig.9B, C50). Terminal branches appear along the entire length of the SAT and innervate the PLP/VLPp compartments and the adjacent IPl/m (Fig.10J; Fig.S2).

DPM Lineages

Located in the postero-medial brain, DPM lineages are primarily connected with the compartments of the central complex and the medial protocerebrum (SMP, SIP, IP). Three of the DPM lineages (DPMm1, DPMpm1, and DPMpm2) are type II lineages which have been recently described (Bayraktar et al., 2010; Bello et al., 2008; Boone and Doe; 2008; Ito and Awasaki, 2008; Izergina et al., 2009), where they were termed DM1 (DPMm1), DM2 (DPMpm1), and DM3 (DPMpm2), respectively. Expression of two genes, distalless (Izergina et al., 2009) and earmuff (Bayraktar et al., 2010), mark the type II lineages. Along with another type II lineage, CM4 (#62, see below; called DM4 in Bello et al., 2008), DPMm1, DPMpm1, and DPMpm2 (#53, #58, #59) include sub-lineages whose SATs characteristically enter through the dorso-lateral and the medial roots of the fan-shaped body (dlrFB, mrFB; Fig.12A, C53, C58, C59). They form the columnar neurons of the central complex, connecting specific small domains of the protocerebral bridge (PB) in a topographical manner with segments and sectors of the FB and EB, respectively (Ito and Awasaki, 2008; Yang et al., 2013; Fig.11B, G, H; Fig.S3). In addition, these type II lineages have other sub-lineages with widespread terminal arborizations outside the central complex. The most prominent arborizations of DPMm1 (#53) are found in the (1) medial IP and deep layers of the adjacent SMP/SLP (via SSAT #53a following the loSM), (2) posterior VMC of both hemispheres, (via SSAT #53d), (3) in the LAL, IPa, ventromedial cerebrum, SEG (via the anterior and descending SSATs #53c/e; Figs.11B; 12A, C53;.Figs.S4, S5). DPMpm1, via its long forward-directed SSAT #58a, has terminal arborizations in the anterior SMP, IPm, and PENPa (tritocerebrum; Fig.11G; Fig.S4). DPMpm2 (#59) arborizes more widely in the superior protocerebrum (SLP, SIP, SMP) and mushroom body lobes via its loSM-associated SSAT, #59a (Fig.11H; Fig.S5).

Lineages DPMpl1 and 2 (#55, #56) enter the posterior neuropil as the most lateral component of the posterior loSM fascicle. The tract extends into the superior protocerebrum, with branches all along its length (SMP, SIP, SLP; Figs.11D, E; 12A, C55, C56; Figs.S4, S5). DPMpl1 is one of the lineages with a long descending fiber bundle, which leaves the loSM, crosses in the chiasm of the median bundle (MBDLchi), follows the median bundle ventrally, and forms terminal arborizations in the PENPa (tritocerebrum), SEG, and TAG (Figs.11D; 12A, C55; Fig.S4). The SAT formed by DPMpl2 (#56) has no descending projections, but, after leaving the loSM, it continues medially into the FB where it forms wide-field arborizations (Fig.11E; Fig.S3). DPMpl3 (#57), whose cell bodies are initially located close to those of DPMpl1/2 (hence inclusion of this lineage in the same subgroup), but shift ventrally during metamorphosis, project along the MEF fascicle (Fig.12B, C57) and innervate specific ventral compartments, including the VMCpo, VLPp, and VLCi. This lineage also has a strong commissural component, reaching, via the great commissure, the contralateral VLCi and VLPp (Fig.11F; Fig.S2).

Two DPM lineages, DPMl1 (#51) and DPMm2 (#54), innervate the posterior brain compartments and send a descending tract towards the SEG and TAG (Figs.11A, C; 12C51, C54; Fig.S4). DPMl1 (#51) arborizes more ventrally than DPMm2 (#54), including in the IP (IPl; IPm/p), VMCi, VMCpo, and SEG (Fig.11A; Fig.S4). DPMm2 also branches in the posterior realm of the IP (IPl; IPm/p), as well as the adjoining SMP, SLP, and VMCpo (Fig.11C; Fig.S4). DPMl1 also has a laterally-directed branch which reaches the lobula (LO).

CM Lineages

Three of the four CM lineages (CM1, #60; CM3, #61; CM4, #62; labeled DM5, DM6, and DM4, respectively, in Izergina et al., 2009) are large type II lineages with multiple sub-lineages. Each of the three has one major ventral SSAT; the three ventral SSATs of CM1-4), forming the loVP fascicle (Lovick et al., 2013; #60v* in Fig.12A), arborize in the postero-ventral brain, including the VCMpo, VMCs, PLP, and VLCi compartments (Fig.13A-C; Fig.S2). The ventral SSATs of CM3/4 have a commissural component crossing in the pPLPC commissure and reaching the postero-ventral compartments of the contralateral hemisphere (Fig.13B-C; Fig.S2). The intermediate and dorsal SSATs of the lineages CM1-4 (#60d* in Fig.12A) connect the postero-ventral brain to more anterior and dorsal regions of the neuropil. CM1 and CM3 each have one SSAT (#60d and 61d2) that travels with the MEF fascicle and arborizes posteriorly (VMCpo), as well as more anteriorly (VMCs, IPl/m, LAL; Figs.12A; 13A, B; Fig.S2). CM1 (#60) has a conspicuous commissural component that interconnects the LAL compartments of either side (Fig.13A; Fig.S2). CM3 (#61d1) also arborizes throughout the entire FB Fig.13B; Fig.S3). As described in the previous section, CM4 (#62) is one of the four lineages (beside DPMm1, DPMpm1, and DPMpm2) which produces columnar neurons of the central complex: the CM4 SSAT (#62d) forming these arborizations is uncrossed and innervates the most lateral part of the PB and FB (Fig.13C; Fig.S3). CM3 and CM4 have one other major SSAT (#61/62a) that projects dorsally along the loSM and interconnects dorsal protocerebral compartments along their antero-posterior axis (SIP/SMP; Fig.13B, C; Fig.S5).

CM5 (#63), the most medial member of the CM group, has an SAT that enters the posterior neuropil medially of the MEF fascicle (Fig.12A, C63). CM5 is the third lineage (beside DPMl1 and DPMm2) which has a long SAT descending posteriorly towards the thoracico-abdominal ganglion (TAG); its proximal arbors are focused on the VMCpo compartment (Fig.13D; Fig.S4).

CP Lineages

The four CP lineages (CP1-4) are located laterally adjacent to the CM group and form mostly projection neurons associated with the superior and inferior protocerebrum. The CP2/3 pair (#65/66) each produces a dorsal and ventral HSAT (HSATd, HSATv) that have a characteristic spatial relationship to the mushroom body peduncle (PED; Fig.12A, C65, C66). Even though the two lineages innervate similar neuropil compartments, each shows distinctive differences. The lineage defined as CP2, with its dorsal HSAT (#65d), forms arborizations in the LH, SIP, and SMP and also projects to the mushroom body vertical lobe and fan-shaped body where it forms wide-field arborizations (Fig.13G; Figs.S3; S5). The dorsal component of CP3 (#66d) has denser innervations in the LH, but misses the projection to the fan-shaped body (Fig.13H). The ventral HSATs of CP2/3 (#65/66v) project along the PLF fascicle that converges upon the peduncle from ventrally (Fig.12A, C65, C66). They form terminal arbors along their axons in the ventro-lateral and inferior protocerebrum (PLP, VLPp, IPm/l; Fig.13G, H; Fig.S2).

CP1 and CP4 (#64, #67) have similar SATs to the HSATds of CP2/3, crossing over the peduncle along the obP fascicle. Characteristically, the tracts of CP1 and 4 are closer to the peduncle than those of CP2/3 (compare Fig.12C64/C67 to C65/C66). Both CP1 and CP4 have dense terminal arborizations in the LH, SIP, and SMP compartments (Fig.13E, F). CP1 (#64), in the late larval brain, has a dorsal (blue arrowhead in Fig.13E) and ventral hemilineage (white arrowhead in Fig.13E): the HSATv projects along the posterior LEF fascicle. In the adult, the tract of the dorsal hemilineage (#64) can be followed along the loSM towards the MBDLchi, where it joins DPMm2 and DPMpl1 to descend towards the SEG/TAG (Fig.12C64; Fig.S4). We identified a total of four clones in different brains for CP1. However, none of them had a ventral hemilineage component, even though a BP104-positive LEFp bundle could be clearly distinguished in the adult (Fig.12A; see accompanying paper by Lovick et al., 2013). One possible explanation is that the ventral CP1 hemilineage undergoes apoptosis during metamorphosis. CP4 has only a dorsal component, both in the larva and adult (Fig.13F; Fig.S5).

BLA Lineages

BLA lineages are located at the antero-lateral neuropil surface. A subgroup of five dorsal BLAs, BLAd1-4 (#68-71) and BLAl (#72), form SATs that converge on one neuropil fascicle, the trSI (Figs.14A, B; 15B, D68-72; Fig.S5), which primarily interconnects domains of the superior protocerebrum. For the four BLAds defined in the larva, three types of clones with different projection envelopes were recovered (Fig.14A); these were assigned arbitrarily to the lineages BLAd1 (#68), BLAd2 (#69), and BLAd3/4 (#70/71). BLAd1 arborizes in the LH and SLP (Fig.14A); BLAd2 is focused more on the SMP and SIP, but has an additional branch that follows the superficial trSI (trSIs), and innervates the posterior SLP, IPp, and IPm/l (Fig.14A; Fig.S5); BLAd3/4 has restricted arborizations in the medial SLP (Fig.14A; Fig.S5). The BLAl lineage (#72) has two separate hemilineages. The dorsal hemilineage (#72d) projects along the trSIs (Figs.14B; 15B, D72) and arborizes in the posterior regions of the LH, SLP, and SMP compartments (Fig.14B; Fig.S5). The medial hemilineage tract (#72m) follows the surface of the VLP, close to the anterior optic tract (green asterisk in Fig.15A), and arborizes in the IPl/m and PLP, respectively (Fig.14B; Fig.S2).

The three ventral BLA lineages, BLAv1 (#73), BLVa2 (#74), and BLAvm (#75), have two hemilineages each and interconnect ventro-lateral compartments of both hemispheres, also forming projections to the superior protocerebrum (Fig.14C-E). The medial hemilineage of BLAv1 (#73m) projects over the anterior surface of the VLPa compartment, following the anterior optic tract (Fig.15A, D73); the tract then extends underneath the peduncle and crosses the midline in the superior arch commissure (SAC). Branches innervate (ipsi- and contralaterally) the VLPa/p and the anterior SLP/IP compartments (Fig.14C; Fig.S1). The medial hemilineage of BLAv2 (#74m) projects medially through the VLPa compartment along the hVLPT tract (Fig.15A, D74). Although the HSATm of the BLAv2 lineage arborizes in a similar ipsilateral territory as BLAv1m (IPl/m, Fig.14D), the hemilineage lacks a strong commissural component across the SAC, but forms a bundle which crosses posteriorly of the central complex towards the contralateral IP (Fig.14D, blue arrowhead). The posterior hemilineages of BLAv1/2 (#73/74p) are directed through the ventro-lateral protocerebrum (Fig.15A) and across the great commissure, arborizing bilaterally in the VLPa/p (Figs.14C, D; 15D73, C74; Fig.S2). The posterior hemilineage of BLAv2 (#74p) has a strong dorsally-directed branch towards the LH and SLP compartments (Fig.14D; Fig.S1). The HSATm of BLAvm (#75m) is located at the antero-dorsal surface of the VLP, where it projects dorsally, passing the anterior optic tract (green asterisk in Fig.15A, D75). The HSATm of BLAvm has widespread terminal arborizations in the dorsal VLPa and dorso-posterior adjacent compartments: the SLP, IPl/m, and PLP (Fig.14E; Fig.S1). The posterior hemilineage of BLAvm (#75p) is located at the lateral surface of the ventrolateral protocerebrum. Its tract, similar to that of BLAl, follows the trajectory of the anterior optic tract (Fig.15B, D75). Anteriorly, it sends arborizations into the LAL compartment (Fig.14E); posteriorly, it innervates the PLP (Fig.14E; Fig.S2).

BLD Lineages