Abstract

Adolescent nicotine use continues to be a significant public health problem. We examined the relationship between the age of youth reporting current smoking and concurrent risk and protective factors in a large state-wide sample. We analyzed current smoking, depressive symptoms, and socio-demographic factors among 4,027 adolescents, ages 12–17 years using multivariate logistic regression (see 2005 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) Public Use File). Consistent with previous work, Latinos, girls, those whose family incomes were below the poverty level, and those with fair-poor health were more likely to display depressive symptoms. Males, whites, older teens and those in fair-poor health were more likely to be current smokers. In a multivariate analysis predicting depressive symptoms, the interaction between age and current smoking was highly significant (Wald Χ2=15.8, p<.01). At ages 12–14 years, the probability of depressive symptoms was estimated to be four times greater among adolescents who currently smoked, compared to those who were not current smokers. The likelihood of depressive symptoms associated with current smoking decreases with age and becomes non-significant by 17 years. Interventions to reduce smoking may be most useful among youth prior to age 12 years and must be targeted at multiple risks (e.g. smoking and depression).

Introduction

Adolescent tobacco use continues to be a national health concern. Over one-third (37.6%) of ninth-grade youth report smoking cigarettes; the rate rises to 55.2% by 12th grade (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2011). Depression and depressive symptoms are well-established as concurrent risks to adolescent smoking (Ellison et al., 2006; Guo, Ratner, Johnson, Okoli, & Hossain, 2010; Hu, Davies & Kandel, 2006; Khaled, Bulloch, Exner, & Patten, 2009; Lam et al., 2005; van de Venne, Bradford, Martin, Cox, & Omar, 2006); this paper examines age-related variation in the relationship between current smoking and depressive symptoms.

The nature of the link between smoking and depressive symptoms among adolescents has been hotly debated (Griesler, Hu, Schaffran, & Kandel, 2011) and is likely bi-directional (Chaiton, Cohen, O’Loughlin, & Rehm, 2009; Munafo, Hitsman, Rende, Metcalfe, & Niaura, 2008). The influences of co-morbid psychiatric disorders vary by the specific type of disorder (Griesler et al., 2011). Results from a Canadian population health study of individuals age 12 and older suggest that depression is a risk factor for quicker onset of smoking and for the predisposition to smoke when under stress (Khaled et al., 2011).DiFranza et al. (2007) suggest that characteristics of adolescents’ first use of tobacco affect future dependence, with those experiencing depressed mood at increased risk. Evidence from animal studies suggests that even after one week of smoking, depressive symptoms can be visible and render smokers more vulnerable to stressors (Iniguez et al., 2009). Adolescents who smoke may also be at increased risk for suicidal thoughts (Jarvelaid, 2004). Most disturbing is that the onset of smoking in adolescence is associated with later risk for mood disorders, including dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and major depression over the lifespan (Ajdacic-Gross et al., 2009).

Overall, the research suggests that the relationship between mood and nicotine may vary based on demographic and other background factors. The relationship seems to be strongest for female adolescents as opposed to males (Poulin, Hand, Boudreau, & Santor, 2005; Ellison et al., 2006). Age may also play a role in this relationship. Among hospitalized adolescents, Ilomaki et al. (2008) reported that boys had a slightly earlier age of smoking compared to girls (12.4 years vs. 13.0 years). Once youth reach a certain age, they may be more susceptible to other comorbid problems. Conwell et al. (2003) documented high rates of multiple problem behaviors among adolescents who were smoking at age 14 years. Adolescent smokers have a documented increased risk of other forms of substance use as well as risky sexual behaviors (O’Cathail et al., 2011). In addition, there are parental factors, such as parental nicotine dependence, and antisocial behaviors that are common to both adolescent nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders (Griesler et al., 2011).

In this study, we aimed to answer the following research questions from data obtained from a large, representative data set of California residents:

What is the relationship between current smoking and depressive symptoms in adolescents, controlling for demographic characteristics, and does this relationship vary by age?

What variables distinguish adolescents with depressive symptoms from those without such symptoms?

Methods

We analyzed data on 4,029 adolescents, ages 12–17 years, from the 2005 CHIS Public Use File (PUF) after obtaining approval from the UCLA Institutional Review Board. Data was collected in 2005 using random-digit dialing. Estimates are weighted to be representative of the population of Californians aged 12–17 years and variances were adjusted for the sampling design. See California Health Interview Survey (2009) for more information on the survey, including survey questions. Weighted chi-square tests were used to compare rates of depressive symptoms and current smoking by individual characteristics; weighted ANOVA tests were used when comparing mean depression levels. We performed a weighted multivariate logistic regression to assess the association between current smoking and depressive symptoms controlling for demographic characteristics.

Measurement

Variables for these analyses were from the CHIS data set. An overview of the measurement of the main variables of interest is provided in the following section. See UCLA Center for Health Policy Research (2005–2006a and 2005–2006b) for more detailed information about the survey and questions, including those described below.

Depressive Symptoms

The presence of depressive symptoms was indicated by a score of 8 or more on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale 8-item short scale (CES-D8). The CES-D8 (Melchior, Huba, Brown, & Reback, 1993) is based on the longer 20-item original version CES-D scale (Radloff, 1977) and has been used in other research with adolescents (DiClemente et al., 2001). Respondents are asked to rate how many days they have experienced certain symptoms in the past 7 days, such as feeling lonely or feeling sad. Responses are rated on a scale of zero to three. Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was 0.83.

Smoking Status

The smoking variable was derived from two items (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 2005–2006a). A “current smoker” was a respondent who reported ever smoking cigarettes and reported smoking at least one time in the past 30 days. A “non-smoker” was a respondent who reported never smoking or not smoking in the past 30 days.

Family Poverty Level

Data were collected on family size and income that was used to compare the family’s income to U.S. federal poverty guidelines. At the time that these data were collected, the federal poverty guideline for the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia for a family of four was $18,100 U.S. dollars (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2002; for more information on measurement of this variable see UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 2005–2006b).

Age

Age was included in the model with dummy indicator variables. Because of the small number of current smokers in the younger (aged 12–14 years) group, those ages were combined into one age category. Separate categories were included for ages 15, 16, and 17. This specification also allowed us to capture non-linear relationships between age and distress, if there were any. Interactions between age and smoking were also included in the model.

Data analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), utilizing a jackknife method to account for the CHIS survey design using replicate weights. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence limits for adolescent distress comparing demographic groups were computed, as well as model-adjusted predicted proportion depressive symptoms for current smokers and current non-smokers at each age level.

Results

The sample for this study consisted of fairly equal numbers of males and females (51.2% and 48.8% respectively). The average age of participants was 14.4 years and the sample was fairly equally distributed across the range of ages. In terms of race, the plurality was white (40.6%) followed by Latino (28.4%), American Indian/Alaskan Native/Pacific Islander/Other (11.8%), Asian (10.7%), and African American (8.5%). Nearly half (45.2%) were from families with incomes at least 3 times higher than the federal poverty level (FPL). Self-reported health ratings were as follows: excellent: 17.9%, very good: 34.4%, good: 35.6%, and fair/poor: 12.2%. Over six percent reported that they were current smokers.

The presence of depressive symptoms by demographic characteristics is presented in Table 1. Of the 4,029 adolescents in the survey, 777 (19.3%), scored 8 or greater on the CES-D8 scale, indicating depressive symptomatology/psychological distress, with a weighted estimate of 21% of adolescents aged 12–17 years in California. In weighted bivariate comparisons, females were more likely to experience psychological distress, as were Latino(a)s, those at lower income levels, and those in poorer health. Current smokers were much more likely to report depressive symptoms than current non-smokers (38.3% vs. 19.8%). Differences in mean CES-D8 scores across categories followed the same patterns as differences in depressive symptomatology. Current smoking was more frequent among males, 17-year olds, whites, and those in fair or poor health.

Table 1.

Characteristics of teens aged 12–17 years in 2005 CHIS PUF data, and depressive symptoms status by characteristic.

| Weighted population estimates |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted counts |

% of population in category |

% with depressive symptoms among those in category |

Mean CES-D8 score in category (95% CI) |

% currently smoking among those in category |

|

| Total sample | 4029 | 100.0% | 21.0% | 4.07 (3.87, 4.28) | 6.5% |

| Gender | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Male | 2050 | 51.2% | 15.1% | 3.28 (3.01, 3.59) | 8.3% |

| Female | 1979 | 48.8% | 27.3% | 4.91 (4.58, 5.23) | 4.6% |

| Age | * | *** | |||

| 12–14 | 2123 | 51.7% | 20.1% | 3.98 (3.72, 4.23) | 1.2% |

| 15 | 682 | 16.7% | 17.5% | 3.79 (3.41, 4.18) | 8.8% |

| 16 | 652 | 17.2% | 27.3% | 4.65 (4.09, 5.21) | 10.6% |

| 17 | 572 | 14.4% | 21.0% | 4.07 (3.66, 4.47) | 17.8% |

| Race/ethnicity | ** | * | *** | ||

| White | 2150 | 40.6% | 18.5% | 3.98 (3.72, 4.25) | 9.6% |

| Latino(a) | 850 | 28.4% | 26.3% | 4.53 (4.16, 4.91) | 5.6% |

| Asian | 353 | 10.7% | 21.6% | 3.88 (3.37, 4.38) | 3.1% |

| African American | 233 | 8.5% | 21.7% | 4.07 (3.32, 3.94) | 4.5% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native/Pacific Islander/Other | 443 | 11.8% | 16.2% | 3.48 (3.01, 3.94) | 2.4% |

| Poverty level | ** | *** | |||

| 0–99% FPL | 500 | 18.3% | 25.1% | 4.59 (4.05, 5.13) | 7.0% |

| 100–199% FPL | 797 | 23.2% | 24.4% | 4.55 (4.13, 4.94) | 7.1% |

| 200–299% FPL | 498 | 13.3% | 22.0% | 4.03 (3.49, 4.58) | 5.2% |

| 300% FPL and above | 2234 | 45.2% | 17.4% | 3.64 (3.38, 3.90) | 6.4% |

| General health condition | *** | *** | *** | ||

| Excellent | 789 | 17.9% | 14.3% | 3.06 (2.70, 3.43) | 3.3% |

| Very good | 1522 | 34.4% | 17.0% | 3.56 (3.26, 3.85) | 6.3% |

| Good | 1313 | 35.6% | 23.1% | 4.45 (4.08, 4.81) | 6.4% |

| Fair/Poor | 405 | 12.2% | 36.4% | 5.78 (5.07, 6.49) | 12.1% |

| Smoking status | *** | *** | |||

| Current smoker | 240 | 6.5% | 38.3% | 6.22 (5.16, 7.29) | 100% |

| Current non–smoker | 3789 | 93.5% | 19.8% | 3.93 (3.73, 4.12) | 0% |

Depression defined as CES-D8 score of 8 or more

p < .05,

p < .01,

p<.001,

p-values based on survey design, weighted estimates

Multivariate logistic regression results indicated significant impacts of demographic characteristics on depressive symptoms as shown in Table 2. Females had significantly higher odds of depressive symptoms (OR vs. males=2.23, CI=1.77–2.82, Wald Χ2=46.1, p<.001), as did Latino(a)s (OR vs. whites=1.41, CI=1.08–1.84,Wald Χ2=6.4, p<.05), those in good health (OR vs. excellent=1.71, CI=1.13–2.60,Wald Χ2=6.4, p<.05), and those in fair/poor health (OR vs. excellent=2.71, CI=1.69–4.33,Wald Χ2=17.3, p<.001) . Poverty status was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Weighted logistic regression results: Demographic variables predicting depressive symptoms among adolescents

| Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95 % Confidence Interval |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male (reference group) | 1.00 | - | - |

| Female | 2.23 | 1.77 | 2.82*** |

| Race/ethnicity | ** | ||

| White (reference group) | 1.00 | - | - |

| Latino(a) | 1.41 | 1.08 | 1.84* |

| Asian | 1.28 | 0.89 | 1.83 |

| African American | 1.16 | 0.68 | 1.99 |

| Am. Indian/Alaska Native/Pacific Isl./ Other | 0.72 | 0.49 | 1.08 |

| Poverty Level | |||

| 0–99% FPL | 1.08 | 0.72 | 1.62 |

| 100–199% FPL | 1.20 | 0.89 | 1.61 |

| 200–299% FPL | 1.15 | 0.83 | 1.58 |

| 300% FPL and above (reference group) | 1.00 | - | - |

| General Health Condition | *** | ||

| Excellent (reference group) | 1.00 | - | - |

| Very good | 1.17 | 0.79 | 1.75 |

| Good | 1.71 | 1.13 | 2.60* |

| Fair/Poor | 2.71 | 1.69 | 4.33*** |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Other predictors in the model included age, current smoking, and age/smoking interactions.

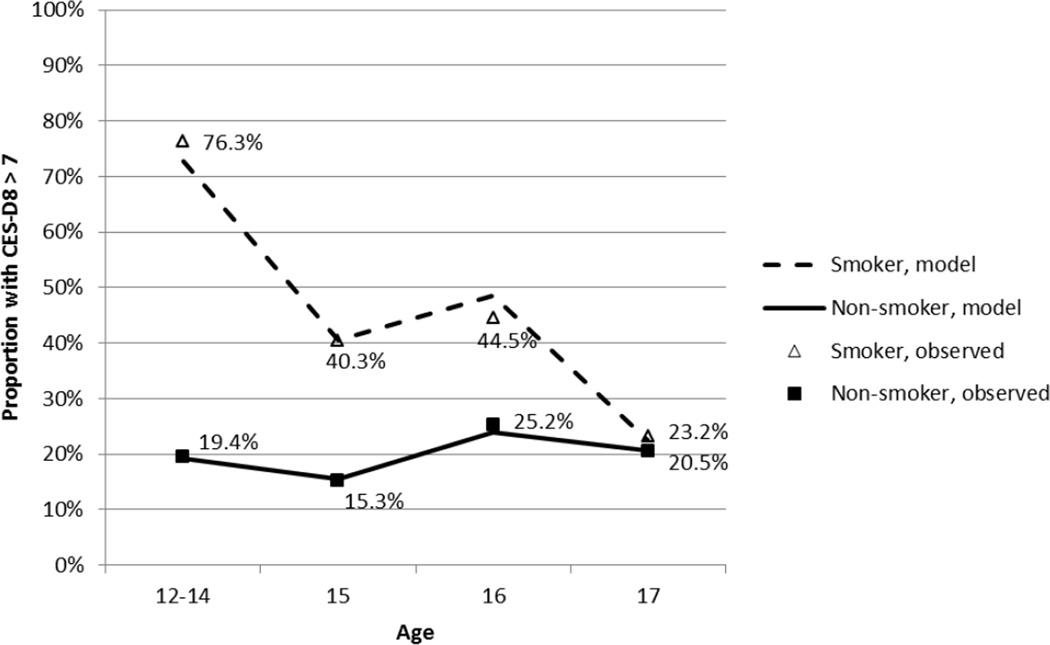

Figure 1 shows the impacts of the interacted age and smoking. Controlling for demographic characteristics, the interaction between age and smoking was highly significant (Wald Χ2=15.8, p<.01). In the younger age group, current smokers were nearly 4 times as likely to have depressive symptoms as current non-smokers (76.3% vs. 19.4%) with the difference decreasing with age and becoming non-significant by age 17 years. Among non-smokers, depressive symptoms did not differ significantly by age.

Figure 1.

Proportion with CES-D8 > 7, by age and whether teen smokes.

Discussion

The relationship between smoking and depressive symptoms is complex, and age of onset may play a role. In this study, the age at which youth reported being a current smoker was highly related to depressive symptoms. Younger current smokers were more likely to have depressive symptomatology than older smokers. Surprisingly, 12–14 year-old current smokers were nearly 4 times more likely to have depressive symptoms than 12–14 year-old current non-smokers. The strength of the link between depressive symptoms and smoking declines among older teens, yet youth were still clearly exhibiting distress. Consistent with Canadian data, smoking risk and depression among female adolescents is high during 7th–9th grades. In Canada, the link between smoking and depression remains stable for a year, and then starts to decline by 12th grade (Poulin et al., 2005). Consistent with other research, youth at increased risk of depression include females, Latino(a)s, and those who rate their overall health as poor (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2008).

Interestingly, the percentage of youth in this study who reported current smoking (6.5%) is quite low compared to national rates for the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, 2010), from 2006–2007, 10.1% of youth ages 12–17 in the U.S. reported smoking cigarettes in the past month. CDC rates for California (6.9%) were comparable to our findings, and California had the 3rd lowest rate of the 50 states. However, there was significant variability throughout the U.S. with rates ranging from 6.5% to 15.9%. Others have documented geographic variability in smoking prevalence that can be impacted by local socio-demographic characteristics (Bernat, Lazovich, Forster, Oakes, & Chen, 2009). Furthermore, those living on the West Coast may be less likely to be persistent smokers (Agrawal, Sartor, Pergardia, Huizink, & Lynskey, 2008).

Another possible explanation for low rates of current youth smoking in California is that prevention efforts may be paying off. A recent report from the Surgeon General of the U.S. (2012) suggests that there is evidence to support that some of the prevention efforts aimed at youth including mass media campaigns, legislative and regulatory initiatives, and school-based programs are effective. These interventions may play a role in the low smoking rates in California as the state ranks 8th nationally in anti-tobacco media campaign intensity, and 87.6% of households have no smoking rules (compared to 77.6% nationally; CDC, 2010).

Many researchers and public health officials assert that tobacco use can serve as a gateway into other forms of substance abuse. In particular, others have documented the link between cigarette smoking and later cannabis use (Beenstock & Rahav, 2002) as well as harder drugs such as cocaine and heroin (Lai, Lai, Page, & McCoy, 2000). For high schoolers who have ever smoked cigarettes, 9 out of 10 go on to use another substance (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2011).

These data suggest targeting younger youth for smoking and depression prevention efforts (Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids). During the period of 2002–2009, rates of greatest perceived harm of smoking among 12–17 year-olds increased with a concomitant decrease in past 30-day nicotine use (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009). Hence, a delay in the initiation of smoking of one or more years may have a positive impact on the trajectory of possible future nicotine dependence. Once youth start to smoke, quitting can be quite challenging. In a pilot study of adolescents in rural Northern California, Ellison et al. (2006) reported that more than half (53%) of those youth who smoke had tried unsuccessfully to quit.

Our conclusions are limited by several methodological issues. The public use data file excluded youth from families who had no phone and was limited to California. As noted above, California may not be representative of other parts of the country, limiting the generalizability of our findings. In addition, this is a cross-sectional study, and therefore, the direction of causality between smoking and depressed mood cannot be determined.

Conclusion

Using data from California on 4,027 adolescents, we found that younger teens aged 12–14 who are current smokers are more likely to have depressive symptoms; this trend decreases with age. Our findings suggest that prevention efforts may need to start prior to age 12 years and target the risks for both depressive symptoms and smoking. For youth who have not yet initiated nicotine use, prevention efforts aimed at the developmental period prior to middle school are clearly needed. These efforts must start at a young age to reach youth before they try cigarettes. Those youth who have already started smoking must get information about smoking cessation through multiple venues to increase the potential impact of anti-smoking education. Once youth become active smokers, the trajectory towards dependence and co-occurring depression may be more difficult to prevent.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center for HIV Identification, Prevention, and Treatment Services (CHIPTS), NIMH grant #MH58107. The data used in this study were provided by the California Health Interview Survey (see CHIS 2007 website for list of multiple funders). The data analyses were funded by the University of California at Los Angeles support to Dr. Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus.

References

- Agrawal A, Sartor C, Pergardia ML, Huizink AC, Lynskey MT. Correlates of smoking cessation in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(9):1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Landolt K, Angst J, Gamma A, Merikangas KR, Gutzwiller F, et al. Adult versus adolescent onset of smoking: How are mood disorders and other risk factors involved? Addiction. 2009;104(8):1411–1419. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02640.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenstock M, Rahav G. Testing Gateway Theory: Do cigarette prices affect illicit drug use? Journal of Health Economics. 2002;21(4):679–698. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat DH, Lazovich D, Forster JL, Oakes JM, Chen V. Area-level variation in adolescent smoking. [Accessed February 26, 2013];Prevention of Chronic Disease. 2009 6:2, 1–8. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2009/apr/08_0048.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2007 Methodology Series: Report 2 – Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2009. [Accessed January 4, 2012]. Available at: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Documents/CHIS2007_method2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2005 Methodology Series: Report 2 – Data Collection Methods. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. [Accessed January 26, 2012]; Retrieved from http://www.tobaccofreekids.org.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco Control State Highlights 2010. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O'Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell LS, O'Callaghan MJ, Andersen MJ, Bor W, Najman JM, Williams GM. Early adolescent smoking and a web of personal and social disadvantage. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2003;39:580–585. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Sionean C, Brown LK, Rothbaum B, et al. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E85. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Pbert L, O’Loughlin J, McNeill AD, et al. Susceptibility to nicotine dependence: the Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youth 2 study. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e974–983. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison J, Mansell C, Hoika L, MacDougall W, Gansky S, Walsh M. Characteristics of adolescent smoking in high school students in California. Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2006;80(2):8. Retrieved from http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/adha/jdh. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Kandel DB. Comorbid psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence in adolescence. Addiction. 2011;106(5):1010–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo SE, Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Okoli CT, Hossain S. Correlates of smoking among adolescents with asthma. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:701–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and correlates of daily smoking and nicotine dependence among young adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilomaki R, Riala K, Hakko H, Lappalainen J, Ollinen T, Rasanen P, et al. Temporal association of onset of daily smoking with adolescent substance use and psychiatric morbidity. European Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniguez SD, Warren BL, Parise EM, Alcantara LF, Schuh B, Maffeo ML, et al. Nicotine exposure during adolescence induces a depression-like state in adulthood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1609–1624. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvelaid M. Adolescent tobacco smoking and associated psychosocial health risk factors. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2004;22(1):50–53. doi: 10.1080/02813430310000988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled SM, Bulloch A, Exner DV, Patten SB. Cigarette smoking, stages of change, and major depression in the Canadian population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;54:204–208. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JVA, Lavorato DH, Patten SB. Major depression is a risk factor for shorter time to first cigarette irrespective of the number of cigarettes smoked per day: evidence from a National Population Health Survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2011;13(11):1059–1067. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S, Lai H, Page B, McCoy CB. The association between cigarette smoking and drug abuse in the United States. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2000;19(4):11–24. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TH, Stewart SM, Ho SY, Lai MK, Mak KH, Chau KV, et al. Depressive symptoms and smoking among Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. Addiction. 2005;100:1003–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior LA, Huba GJ, Brown VB, Reback CJ. A short depression index for women. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1993;53:1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Munafo MR, Hitsman B, Rende R, Metcalfe C, Niaura R. Effects of progression to cigarette smoking on depressed mood in adolescents: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Addiction. 2008;103(1):162–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. Adolescent substance use: America’s #1 public health problem. 2011 Available at: http://www.casacolumbia.org/upload/2011/20110629adolescentsubstanceuse.pdf [Accessed January 4, 2012];

- O'Cathail SM, O'Connell OJ, Long N, Morgan M, Eustace JA, Plant BJ, et al. Association of cigarette smoking with drug use and risk taking behaviour in Irish teenagers. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(5):547–550. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin C, Hand D, Boudreau B, Santor D. Gender differences in the association between substance use and elevated depressive symptoms in a general adolescent population. Addiction. 2005;100:525–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, U.S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed October 26, 2011];2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2008 Available at: http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k4nsduh/2k4tabs/Sect6peTabs1to81.htm#tab6.62b.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434) Rockville, MD: 2009. [Accessed October 26, 2011]. Available at: http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k8nsduh/2k8Results.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. [Accessed February 27, 2013];CHIS 2005 Adolescent Questionnaire Version 5.3. 2005–2006a October 10, 2006. Available at: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Documents/CHIS2005_adolescent_q.pdf.

- UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. [Accessed February 27, 2013];CHIS 2005 Adult Questionnaire. Version 6.4. 2005–2006b August 26, 2010, Available at: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/design/Documents/CHIS2005_adult_q.pdf.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Annual Update of the HHS Poverty Guidelines. Federal Register. 2002;67:6931–6933. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- van de Venne J, Bradford K, Martin C, Cox M, Omar HA. Depression, sensation seeking, and maternal smoking as predictors of adolescent cigarette smoking. Scientific World Journal. 2006;6:643–652. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]