Abstract

Studies of adolescent or parent-based twins suggest that gene–environment correlation (rGE) is an important mechanism underlying parent–adolescent relationships. However, information on how parents′ and children’s genes and environments influence correlated parent and child behaviors is needed to distinguish types of rGE. The present study used the novel Extended Children of Twins model to distinguish types of rGE underlying associations between negative parenting and adolescent (age 11–22 years) externalizing problems with a Swedish sample of 909 twin parents and their adolescent offspring and a U.S.-based sample of 405 adolescent siblings and their parents. Results suggest that evocative rGE, not passive rGE or direct environmental effects of parenting on adolescent externalizing, explains associations between maternal and paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems.

The association between negative parenting behaviors (i.e., harsh discipline, criticism, conflict, parental rejection) and child and adolescent externalizing problems (i.e., acting out, delinquency, aggression) is well established (e.g., Baumrind, 1991; Stice & Barrera, 1995) and there has been long-standing interest in understanding the mechanisms underlying this association (e.g., Shaw & Bell, 1993). Traditionally, researchers have assumed a unidirectional model, such that children who are exposed to greater parental negativity, form insecure attachment bonds, or receive poor socialization from parents are at greater risk of developing externalizing problems (e.g., Hirschi, 1969). More recently, theories of transactional processes have been used to explain associations between parental negativity and children’s externalizing problems, such that parenting affects children’s externalizing problems, but that child externalizing problems also impact parenting behaviors (e.g., Lansford et al., 2011; Lytton, 1990; Stice & Barrera, 1995).

To date, few studies examining transactional processes have utilized genetically informed study designs capable of testing the contributions of parents’ and children’s genes on the association between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems. The Extended Children of Twins (ECOT) design is a novel approach that combines a sample of parents who are twins and their adolescent children with a sample of adolescents who are twins and siblings and their parents (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011). This combination assesses genetic and environmental contributions from both adolescents and parents to both parenting and adolescent behavior, which is integral for understanding the mechanisms underlying the associations between them, and enables researchers to test the direction of effects (i.e., parent to child and or child to parent) of the associations. Thus, the present study uses the ECOT approach to examine the extent to which adolescent- and parent-driven effects account for the association between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems.

Transactional Theories of Parental Negativity and Adolescent Externalizing

Theorists have postulated that both child- and parent-based effects contribute to associations between parental negativity and child and adolescent externalizing problems (e.g., Shaw & Bell, 1993). Transactional theories have been used to explain associations between positive parenting and normative development (e.g., Greenberg & Speltz, 1988; Greenberg, Speltz, & Deklyen, 1993) as well as associations between negative parenting and child behavior problems. Patterson and Fisher (2002) posited that parental negativity and child externalizing problems are associated transactionally, via coercive cycles, such that parents who respond negatively to their child’s problematic behaviors appear to exacerbate the child’s emotional and behavioral problems through environmental mechanisms. This reciprocal negative interactive style sets the parent–child relationship on a downward spiral of continual negative interactions, resulting in the exacerbation of both negative parenting and offspring externalizing problems. This model was originally developed with regard to the early development of conduct disorder in boys on very short timescales (i.e., over the course of specific parent–son interactions). The coercive cycles theory has made great contributions in terms of highlighting the transactional influences of parenting and child behaviors in the development of externalizing problems, but did not anticipate the importance of child-based genetic influences in perpetuating negative cycles and for longer term bidirectional influences across the lifespan.

Children’s characteristics have been hypothesized to elicit negative responses from others in interpersonal relationships throughout the lifespan, thereby contributing to the continuity of behavior problems over time (Moffitt, 1993). Theories of transactional or bidirectional influences between parents and children have generally been supported using nongenetically informed, longitudinal studies across childhood and adolescence most often examining one child per family (e.g., Deater-Deckard & Dodge, 1997; Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Pettit & Arsiwalla, 2008; Zadeh, Jenkins, & Pepler, 2010). These studies have typically shown that earlier child externalizing problems are associated with later negative parenting and that earlier negative parenting is associated with later child externalizing problems via cross-lagged methods. However, these nongenetically informed studies cannot account for the influence of genes shared by children and their parents, or the influence of children’s genes on how they are parented. There is substantial evidence of genetic influences on negative parenting (e.g., Kendler, 1996; Losoya, Callor, Rowe, & Goldsmith, 1997; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, Spotts, & Ganiban, 2007; Neiderhiser et al., 2004) and on child and adolescent externalizing problems (e.g., Burt, 2009; Miles & Carey, 1997; Rhee & Waldman, 2002). Therefore, it is possible that adolescents’ genes contribute to both parenting and externalizing problems.

Reciprocal interactions could reflect the direct environmental influences between parents and children implicit in many theories of development. However, because genes and environments are correlated, especially in families, passive rGE (i.e., parents and children share genes that may influence how parents parent and children behave) and evocative rGE (i.e., when parenting is a response to children’s genetically influenced behavior) may also exacerbate the association between negative parenting and offspring externalizing problems (Plomin, DeFries, & Loehlin, 1977; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). Therefore, understanding whether rGE contributes to the association between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing problems, and if so, which type, can help to clarify the mechanism of bidirectional influences between parenting and adolescent behavior. Drawing from the transactional theories of parent–child relationships and methodological and theoretical frameworks that distinguish the influence of adolescents’ and parents’ genes on the association between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems (i.e., ECOT), we examine the contributions of rGE to associations between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems.

Influence of Parent Genes

Negative parenting behaviors may be associated with adolescents’ externalizing problems via passive rGE if children and parents share genes predisposing the child to have externalizing problems and predisposing the parent to use negative parenting behaviors. Samples of parents who are twins (Children of Twins design [COT]) provide a useful test of passive rGE by using the contrast in genetic relatedness of monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twin parents to estimate the influence of parents’ genes and environments on parenting behavior, child externalizing problems, and associations between parenting behaviors and child behaviors (see Horwitz, Marceau, & Neiderhiser, 2011).

COT design studies have been used to examine several types of negative parenting behaviors, including exposure to harsh discipline, family conflict, and marital conflict. Findings suggest that while exposure to harsh parenting and conflict is an environmental risk factor, parents’ genes are also implicated in associations between family conflict and adolescents’ externalizing and substance use problems (D’Onofrio et al., 2007; Knopik et al., 2006; Lynch et al., 2006; Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, Tuvblad, Larsson, & Carlstrom, 2007; Schermerhorn et al., 2011; Silberg, Maes, & Eaves, 2010, 2011). Studies comparing adopted and biological children also suggest that passive rGE operates in infancy, early and middle childhood, and adolescence (Braungart-Rieker, Rende, Plomin, DeFries, & Fulker, 1995; McGue, Sharma, & Benson, 1996) and that family environmental influences (e.g., maternal depression, parent –child conflict) contribute to stability of antisocial behavior (Burt, McGue, & Iacono, 2010; Klahr, McGue, Iacono, & Burt, 2011; Tully, Iacono, & McGue, 2008). Together, this evidence suggests that parenting and offspring development are associated via passive rGE while causal, environmental mechanisms are likely also operating. While COT studies have permitted a careful examination of the role of passive rGE in influencing child and adolescent outcomes, they are underpowered for identifying evocative rGE because of limited variability in the genetic relatedness of offspring. Thus, to detect evocative rGE, studies have investigated the influence of adolescents’ genes on their own behavior and on their parents’ behavior.

Influence of Child Genes

Adolescents’ heritable characteristics may shape negative parenting via evocative rGE, such that adolescents with more externalizing problems may evoke more negative responses from their parents. For example, there is evidence that variation in adolescents’ genotypes contribute to the parenting they receive (e.g., McGue, Elkins, Walden, & Iacono, 2005; Narusyte, Andershed, Neiderhiser, & Lichtenstein, 2007; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Hetherington, & Plomin, 1999; Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al., 2007; Plomin, 1994). Genetically informed studies of twin and sibling children have examined transactional influences between child externalizing problems and parental negativity. Generally, findings support bidirectional influences, showing that child externalizing problems predict parental negativity and that parental negativity predicts later externalizing problems in early to middle childhood (e.g., ages 4–7; Larsson, Viding, Rijsdijk, & Plomin, 2008) and during adolescence (Burt, McGue, Krueger, & Iacono, 2005; Neiderhiser et al., 1999). These findings suggest that mainly the influence of children’s genes, but also children’s environmental influences, contribute to change in positivity and negativity in the parent– child relationship.

The findings described above represent evocative rGE, as the power to detect evocative rGE is greater in child-based designs, i.e., when adolescent siblings vary in genetic relatedness. Findings from adoption studies corroborate the role of evocative rGE in explaining associations between negative family environmental influences (e.g., parenting, parent– child conflict) and children’s externalizing symptoms (Deater-Deckard & O’Connor, 2000; Ge et al., 1996; O’Connor, Deater-Deckard, Fulker, Rutter, & Plomin, 1998). However, studies of adolescents who are twins and siblings lack the ability to definitively separate passive from evocative rGE when examining the association between parenting behavior and adolescent characteristics because only genetic and environmental influences of the adolescent can be estimated. Information on genetic and environmental influences on both parent and adolescent behavior is needed to distinguish passive from evocative rGE in associations between parent and adolescent behavior (e.g., Heath, Kendler, Eaves, & Markell, 1985).

Extended Children of Twins Design

A novel approach for understanding the direction of effects (parents influencing offspring vs. offspring influencing parents) and rGE underlying the association between parent and adolescent behavior is the ECOT design (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011; see also Silberg & Eaves, 2004). ECOT combines two studies, a parent-based and a child-based twin design, with comparable measures of parent and adolescent behavior within the same nested model. Therefore, the model includes multiple genetic and environmental sources, allowing for tests of reciprocal effects, and an identified model with unbiased estimates (Heath et al., 1993). The power to detect evocative rGE lies in the child-based design, which estimates the influence of children’s genes on their behavior and on their parents’ behavior. The ability to detect passive rGE lies in the parent-based design, which estimates the influence of parents’ genes and environmental influences on their behavior and their child’s behavior. By combining the two studies in the same statistical model using similarly measured constructs, the ECOT design allows researchers to examine three possible mechanisms explaining associations between parent and child characteristics: (a) direct environmental effects of parenting behavior on child behavior, free of genetic influences of the parent or child; (b) passive rGE, suggesting that parents’ genes influence both their parenting and their child’s behavior; and (c) evocative rGE, suggesting that children’s genes influence both their externalizing problems and the way they are parented.

Only two studies have used the ECOT design to disentangle the contributions of passive rGE, evocative rGE, and direct environmental parenting influences on the association between aspects of parenting behaviors and child adjustment problems (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011). In the first study, the ECOT design was applied to examine the association between maternal emotional overinvolvement and adolescent internalizing problems. Findings showed that evocative rGE completely accounted for the association between maternal overinvolvement and adolescent internalizing problems, highlighting the role of adolescents’ heritable characteristics for shaping parents’ behaviors (Narusyte et al., 2008). More recently, the ECOT model was applied to the association between maternal and paternal criticism and adolescent externalizing problems. Findings revealed that the association between maternal criticism and adolescent externalizing problems was explained by evocative rGE, whereas there was only direct environmental influence of paternal criticism on child externalizing problems (Narusyte et al., 2011).

These novel studies have contributed to the literature by demonstrating the role of children’s genes in the evocative effects proposed in theories of parental contributions to children’s behavior problems. Though Narusyte et al. (2011) found differences in mechanisms underlying associations between mothering versus fathering and adolescent adjustment problems, there was limited power to detect evocative rGE in the association between paternal criticism and adolescent externalizing due to a low response rate by fathers in the child-based sample used. Because of this limitation, it is unclear whether the observed differences between mother– and father–adolescent relationships actually reflect a lack of power to detect evocative rGE in the fathering sample. Further, it is unclear whether findings are specific to parental criticism, or if evocative rGE and environmental parenting effects also drive the associations across different features of parental negativity (i.e., criticism, punishment, and conflict) and adolescent externalizing problems.

Present Study

Using the ECOT approach, we examined the association between a broad rating of parental negativity (including negativity, conflict, and harsh discipline) and adolescent externalizing problems using the same parent-based sample as used in the two previous ECOT studies (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011), and a different sample of adolescent twins and siblings. The inclusion of a wider range of negative parenting behaviors, all of which have been highlighted in the literature to have strong and consistent effects across studies (e.g., Loeber & Dishion, 1983), will help to clarify whether the mechanisms underlying the associations between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems identified by Narusyte et al. (2011) are specific to parental criticism, or if there is a more general effect of negative parenting. The inclusion of a twin and sibling sample with a large number of fathers will help to clarify whether there are differences in the rGE underlying associations between maternal versus paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems.

Hypotheses

Drawing from the literature suggesting that adolescents’ genes impact the parenting they receive, we hypothesized that the association between parental negativity and externalizing problems in adolescence would arise primarily because parents are responding to adolescents’ genetically influenced externalizing problems (i.e., evocative rGE) in such a way that it contributes to higher levels of parental negativity, broadly. We also expect that parental negativity (particularly fathers’ negativity) would exert an environmental influence on adolescent externalizing problems, based on findings from Narusyte et al. (2011), and evidence of passive rGE for fathers’ but not mothers’ negativity in Neiderhiser et al. (2004) and Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al. (2007).

Method

Participants and Procedures

The present study examines how genetic and environmental influences are correlated for the association between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems using the U.S.-based Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development study (NEAD; Neiderhiser, Reiss, & Hethe-rington, 2007; Reiss, Neiderhiser, Hetherington, & Plomin, 2000) and the Swedish-based Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden (TOSS; Neiderhiser & Lichtenstein, 2008). TOSS was designed in part to mirror NEAD. Indeed, this pair of studies is the only instance of such a design. In TOSS the twins are parents, whereas in NEAD the twins are adolescents. Great care was taken to use identical measures of parenting in both. Because of its unique design, TOSS could only be conducted in a country with a very large, well-documented twin registry. At the time the studies were designed, only the Swedish twin registry was large enough. To maintain the integrity of the mirror-image design across nationalities, careful attention was paid to potential cultural confounds and to translating instruments from English to Swedish (Reiss et al., 2001). Previous reports have found the U.S. and Swedish samples to be comparable on a number of key demographic and substantive variables including negative parenting and externalizing problems (Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lich-tenstein, et al., 2007). While TOSS has been used for ECOT models in the past (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011), the inclusion of NEAD as the child-based sample is unique to this study. By adding nontwin siblings with the twins in the child-based design, the ECOT model is able to more precisely detect evocative rGE effects and is more generaliz-able to multiple family types, not only twins.

The Nonshared Environment in Adolescence (NEAD) study

The NEAD sample consisted of 721 predominantly White (94%) families of twins and siblings who participated in the first wave of data collection in the NEAD project (Neiderhiser, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2007). Most of the families were recruited through a national market survey of 675,000 families, though some were recruited through random digit dialing of 10,000 telephone numbers throughout the United States. Zygosity was established using a validated questionnaire for which adolescent twins were rated for physical similarity (Nichols & Bilbro, 1966). The agreement of this particular questionnaire with genotyping has been estimated at over 90% (e.g., Goldsmith, 1991).

The twins and siblings who still resided primarily at home were also assessed approximately 3 years after the initial assessment. Data were drawn from the 408 twin and siblings who participated in the second assessment in order to match the ages of adolescents in both samples. The analysis sample consists of 405 families falling into one of six sibling categories in two family types: 63 same-sex MZ twins, 75 DZ twins, and 58 full siblings in nondivorced families, and 95 full siblings, 60 half siblings, and 44 genetically unrelated siblings in stepfamilies. Stepfamilies were together for at least 5 years at the time of the first assessment to avoid periods of instability due to family formation. The analysis sample is slightly reduced (by three pairs) because of missing information on zygosity. Adolescents were 11–22 years old (M = 15.5 years, SD = 2 years). Siblings were within 4 years of age of each other (M = 1.6 years, SD = 1.3 years), and lived in the same two-parent household at least 50% of the time for at least 5 years.

The Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden

The TOSS sample consisted of 909 White pairs of twin parents, their spouse or partner, and their adolescent child (Neiderhiser & Lichtenstein, 2008). The TOSS sample was obtained through the use of the Swedish Twin Registry. Zygosity was established using the same validated questionnaire as used in the NEAD study, for which adolescent twins were rated for physical similarity (Nichols & Bilbro, 1966). The analysis sample consists of 854 families for whom we have zygosity information (126 MZ fathers, 188 DZ fathers, 258 MZ mothers, and 282 DZ mothers). As in the NEAD study, adolescents were 11–22 years old (M = 15.7 years, SD = 2.5 years). All adolescent cousin pairs were the same sex and were within 4 years of age of each other (M = 1.8 years, SD = 1.5 years).

Measures

Parental negativity

Parental negativity was measured in each study by mother, father, and adolescent report using identical composite scores including the conflict subscale (e.g., “How much do you yell at the child after you’ve had a bad day?”) of the Parent-Child Relationships questionnaire (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), and the coercive (e.g., brought up a lot of the child’s faults when the two of you argued) and punitiveness (e.g., punished you more severely than usual for bad behavior) subscales of the Parent Discipline Behavior Inventory (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992; α > .61 across reporters in both samples). Mother and adolescent reports of mothers’ negativity, and father and adolescent reports of fathers’ negativity on each subscale were standardized and summed to create the negativity composites (α > .74 for both samples). Composites were created in this way to be consistent with previous reports (i.e., Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al., 2007) and to avoid single-measure bias (Bank, Duncan, Patterson, & Reid, 1993). Each composite score was ranked to normalize distribution, consistent with previous studies using these data (Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al., 2007).

Adolescent externalizing problems

Adolescent externalizing problems were measured using multirater composite scores in each study. In NEAD, mother, father, and adolescents reported externalizing problems on the Zill Behavior Problems Inventory (ZIL: Zill, Hetherington, & Arasteh, 1988). The ZIL externalizing problems subscale is composed of 20 items (e.g., “Breaks things on purpose, deliberately destroys his or her own or other’s things”; “Is disobedient at home”) on a 1 (often true) to 3 (never true) scale over the past 3 months (α > .87 for each reporter). Items are reversed and then summed, so higher scores indicate more externalizing problems. In TOSS, mother, father, and adolescent-reported externalizing problems on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) were summed to create an externalizing composite. The CBCL externalizing subscale is composed of 30 items (e.g., “I destroy my own things”; “I disobey my parents”) on a 1 (not true) to 3 (often true) scale over the past 6 months. The composite externalizing scores were acceptably reliable in both studies (α > .62 for both siblings in NEAD; α > .70 for both siblings in TOSS). Again, each composite score was ranked to normalize the distributions.

Analytic Strategy

Twin and sibling studies

Quantitative genetic analyses take advantage of similarities and differences between twin and siblings with varying degrees of genetic relatedness to parse the variance in a particular phenotype into additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and nonshared environmental (E) components. By definition, twins and siblings share 100% of their shared environment (nongenetic influences that make family members similar) and none of their nonshared environment (nongenetic influences that make family members different including measurement error). Different sibling types share different average proportions of their segregating genes: MZ twins share 100% of their genes, DZ twins and full siblings share an average of 50% of their segregating genes, half-siblings and offspring of MZ twins share an average of 25% of their segregating genes, offspring of DZ twins share an average of 12.5% of their segregating genes, and stepsiblings are genetically unrelated.

Estimates of A, C, and E can be obtained by comparing the sizes of correlations between Sibling 1 and Sibling 2 across sibling types. For example, if the correlation of Sibling 1’s externalizing problems and Sibling 2’s externalizing problems among MZ twins is twice that of the correlation among DZ twins, genetic influences are indicated (because MZ twins share twice as many segregating genes as DZ twins). Shared environmental influences are indicated to the extent that the correlations between Sibling 1 and Sibling 2’s externalizing problems among each different sibling type are similar. Nonshared environmental influences are indicated to the extent that MZ twins’ externalizing problems are not perfectly correlated. For a more detailed explanation of quantitative genetic theory and expectations from twin correlations, see Marceau and Neiderhiser (in press) and Narusyte et al. (2008).

The ECOT model

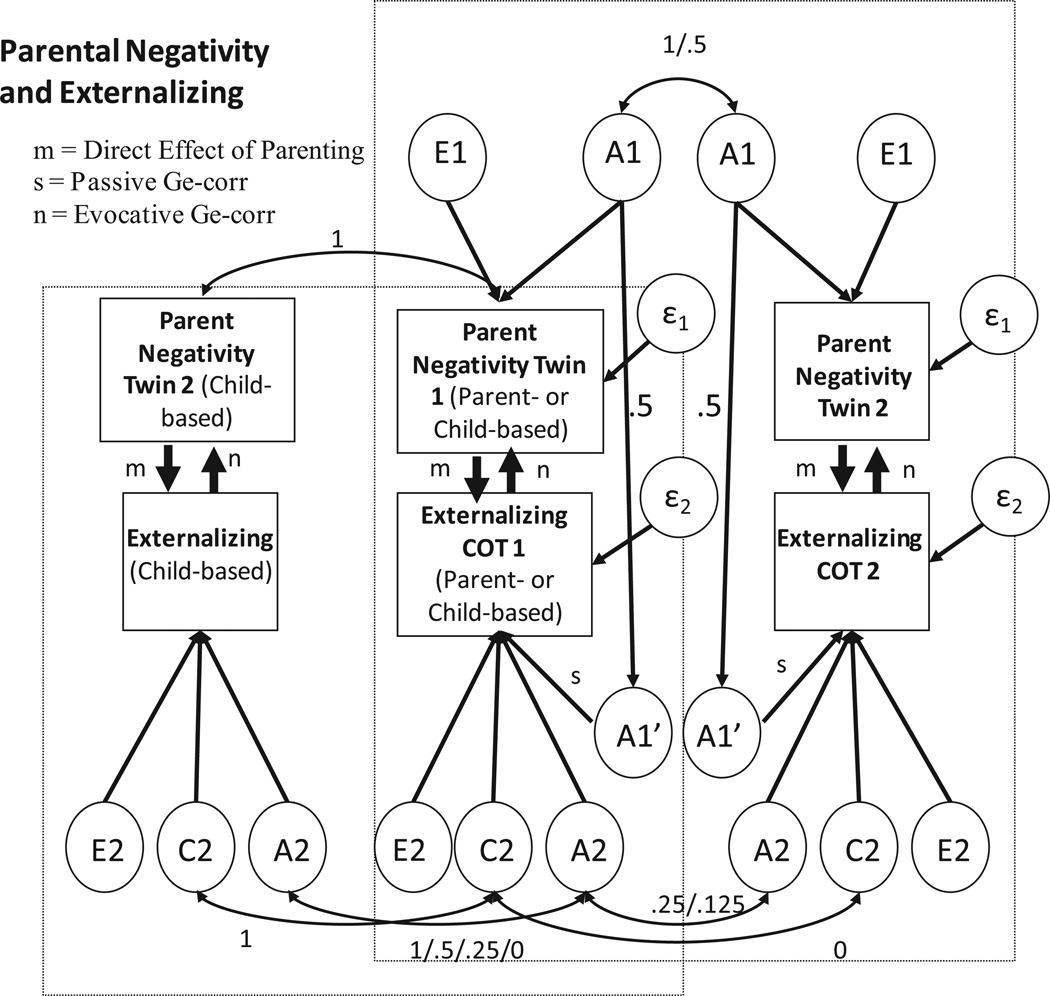

To test whether the association between parental negativity and externalizing problems in middle to late adolescence arises because of evocative rGE, passive rGE, or environmental effects free from genetic confounds, we used the ECOT model (Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011; ECOT, Figure 1). The ECOT model adds the power of a classic twin design to the power of a children-of-twins design. The lower box on the left of Figure 1 represents the classic twin sample, while the larger box on the right represents the COT sample. This quantitative genetic model is built in a structural equation modeling framework using Mx (Neale, 1999), which parses the variance in parental negativity into the influence of parents’ genes and the nonshared environment. These are represented as A1 (genetic influences) and E1 (nonshared environmental influences) along the top of Figure 1. The influence of shared environment on parental negativity for twin parents was not included in the initial model for two reasons. First, the intra-class correlations suggested that effects from the shared environment were not present on maternal and paternal negativity (see Table 1). This is consistent with other studies that have examined genetic and environmental influences on twin parents (e.g., Knopik et al., 2006; Lynch et al., 2006; Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011). Second, the ECOT model performs better when shared environmental influences are estimated on only the child phenotype rather than on both the parent and child phenotype because a larger sample size is needed to detect small shared environmental effects on the parent phenotype (Narusyte et al., 2008). This is in part because there is less power in twins-only designs (as opposed to twin and sibling designs) to detect shared environmental influences. Furthermore, shared environmental influences on parenting are likely to be small in COT designs as they reflect either the lasting impact of the twin parents’ own rearing environment or current contact.

Figure 1.

Extended Children of Twins (ECOT) model. This is a representation of the path diagram used to fit the ECOT model. The lower left-hand box represents the child-based sample. Parent negativity is correlated 1 for Twin 1 and Twin 2 because in the child-based sample the adolescent siblings share parents. The larger right-hand box represents the parent-based (COT) sample. A1 represents latent genetic influences of parents on their parenting; E1 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of parents on their parenting. A2 represents latent genetic influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; C2 represents latent shared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; E2 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems. A1′ represents the effect of genes shared by parents and adolescents on adolescents’ externalizing problems. Path m represents direct environmental effects of parenting on adolescents’ externalizing problems while path n represents child evocative effects of adolescents’ externalizing problems on parenting. Path s represents the influence of shared genes of parents and adolescents; significant path s and path m signify passive gene–environment correlation (rGE) while significant path n and either A2 or s signifies evocative rGE. Measurement error is estimated as ε1 and ε2, and constrained to be equal during model fitting.

Table 1.

Intraclass Correlations for Parental Negativity and Child Externalizing in Each Sample

| MZ | DZ | FI | FS | HS | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEAD | ||||||

| N | 126 | 148 | 116 | 190 | 120 | 88 |

| Externalizing | .67 | .47 | .29 | .39 | .19 | .08 |

| Maternal negativity | .63 | .68 | .54 | .46 | .34 | .12 |

| Paternal negativity | .74 | .69 | .24 | .55 | .39 | .27 |

| Externalizing–maternal negativity | .44 | .31 | .24 | .27 | .03 | .05 |

| Externalizing–paternal negativity | .32 | .28 | .10 | .23 | .15 | .05 |

| TOSS | ||||||

| Mothers (N) | 516 | 564 | ||||

| Externalizing (adolescents of twin mothers) | .48 | .44 | ||||

| Maternal negativity | .29 | .20 | ||||

| Externalizing–maternal negativity | .24 | .18 | ||||

| Fathers (N) | 252 | 376 | ||||

| Externalizing (adolescents of twin fathers) | .38 | .05 | ||||

| Paternal negativity | .27 | .46 | ||||

| Externalizing–paternal negativity | .17 | .13 |

Note. “Externalizing,” “maternal negativity,” and “paternal negativity” are cross-twin, intraclass correlations. “Externalizing–maternal negativity” and “externalizing–paternal negativity” are cross-twin, cross-trait correlations. NEAD = Nonshared Environment in Adolescents Study (child-based twin/sibling design); TOSS = Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden (parent-based twin design); MZ = mono-zygotic twins; DZ = dizygotic twins; FI = full siblings in nondivorced families; FS = full siblings in stepfamilies; HS = half siblings; US = genetically unrelated stepsiblings.

In accordance with quantitative genetic theory and the average percentage of genes shared between different types of siblings, the correlation between A1 for Twin Parent 1 and Twin Parent 2 is constrained to 1 for MZ twin parents and .5 for DZ twin parents. Genetic transmission is also included in the model using the latent factor A1′. The correlation between A1 (influence of parents’ genes on their own parenting) and A1′ (influence of those parenting genes on adolescent externalizing problems) is set to .5 (because children inherit half of their genes from their parents), and the influence of those genes that parents and offspring share on externalizing problems are freely estimated (A1′).

The variance in adolescent externalizing problems is parsed into the influence of adolescents’ genes, shared, and nonshared environments. These are represented as A1′ (parent and child shared genes for parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems), A2 (unique genetic influences on externalizing), C2 (shared environmental influences on externalizing), and E2 (nonshared environmental influences on externalizing) along the bottom of Figure 1. Because twins and siblings are used in the child-based design (NEAD), the correlation between A2 for adolescent Sibling 1 and adolescent Sibling 2 is constrained to 1 for MZ twins, .5 for DZ twins and full siblings, .25 for half siblings, and 0 for genetically unrelated stepsiblings.

Correlations between the influence of adolescents’ genes and parents’ genes are tested, along with direct causal paths from parental negativity to adolescent externalizing problems and paths from adolescent externalizing problems to parental negativity. Correlations between parents and adolescents’ genetic influences in combination with genetic influences on parental negativity in TOSS and genetic influences on externalizing problems in NEAD (path s) and a significant path from parental negativity to adolescent externalizing problems (path m) together suggest parent-based genetic effects (i.e., passive rGE). Only a significant path from parental negativity to adolescent externalizing problems (path m) without a significant genetic association (path s) indicates a direct environmental effect of parental negativity on adolescents’ externalizing problems. A significant path from adolescent externalizing problems to parental negativity (path n) in combination with genetic influences on externalizing problems in NEAD (as indicated by a significant path from A1′ or A2 on adolescent externalizing problems) indicates the influence of child-based genes (i.e., evocative rGE). Finally, measurement error is estimated separately (ε1 and ε2 in Figure 1). Detailed information about the specifications and power of the ECOT model can be found in Narusyte et al. (2008). Because this model is conducted using raw data in a structural equation modeling framework, missing data are handled using full information maximum likelihood data estimation procedures. All analyses were conducted after controlling for age, sex, and age difference (for nontwin siblings in NEAD).

Model fitting

We took an informed approach to model fitting, starting with a full model estimating all paths, and culminating in a best fitting model favoring parsimony. First, 95% confidence intervals were used to determine the significance of path estimates. We then conducted a series of nested models to determine if there was a significant decrement in model fit when dropping paths. We systematically dropped paths m (passive rGE) and n (evocative rGE) to verify the significance of each of these paths. We then dropped each path deemed nonsignificant based on confidence intervals separately, and as a group. The model with the least number of parameters without a significant decrement of model fit was judged to be the best fitting, most parsimonious model.

Assumptions

Twin models are built on several assumptions that can impact the estimates of genetic and environmental influences recovered in analyses. First, the equal environments assumption is that shared and nonshared environmental influences are equivalent for each sibling type (i.e., MZ twins’ environments are no more similar than genetically unrelated siblings’ environments). No systematic differences have been found negating the validity of the equal environments assumption (Loehlin & Nichols, 1976; Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Reiss et al., 2000). Second, it is assumed that assortative mating is limited (i.e., individuals do not systematically choose their mates based on genetically influenced characteristics). While assortative mating is generally modest for most psychological traits (e.g., Plomin, DeFries, & McClearn, 1990), there is evidence of moderate assortative mating for antisocial behavior (e.g., Galbaud Du Fort, Boothroyd, Bland, Newman, & Kakuma, 2002). The presence of assortative mating on traits involved in the intergenerational transmission of externalizing problems inflates shared environmental influences at the expense of genetic influences. This is because both parents are more likely to pass on genes influencing externalizing problems, so DZ twins would likely share more than 50% of their segregating genes for externalizing problems and would have a higher sibling concordance, more similar to that of MZ twins. This would reduce the contrast in correlations between MZ and DZ twins, and models using the standard fixed path coefficients for correlations between genetic influences of MZ (1) and DZ (.5) twins would underestimate genetic but overestimate shared environmental influences. However, the inclusion of genetically unrelated siblings in the child-based design in the present study helps to attenuate this bias. Assortative mating on antisocial behavior also suggests that passive rGE is more likely contributing to externalizing problems, inflating the likelihood of finding passive rGE here.

There are also several assumptions specific to the ECOT model (see also Narusyte et al., 2008; Narusyte et al., 2011). Namely, the samples are assumed to be equivalent. Specifically, we assume no systematic differences in genetic and environmental influences on parenting or on adolescent externalizing problems across the two samples. We also assume that the measurement error does not differ across phenotypes (i.e., ε1 = ε2), across samples in order for the model to be identified. Finally, in the present study, we assume that rGE processes underlying the association between parenting and adolescent externalizing problems do not differ in the Swedish and U.S. populations represented in TOSS and NEAD, as we obtain one estimate using both samples.

Results

Intraclass Correlations

Intraclass correlations for mothers’ and fathers’ negativity and adolescents’ externalizing problems are presented in Table 1. These correlations provided preliminary indications of the extent to which parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems are explained by passive and evocative rGE effects and environmental effects free from genetic confounds. Intraclass correlations on parenting in NEAD suggest some influence of adolescent’s genetic (approximately 0–8% of the variance for mothers and 10–34% of the variance for fathers), shared (approximately 12–73% of the variance for mothers and 26–64% of the variance for fathers), and nonshared (approximately 15% for mothers and 26% for fathers) environmental influences on maternal and paternal negativity. The presence of genetic influences suggests the potential for evocative rGE. Intraclass correlations on parenting in TOSS suggest primarily nonshared environmental influences (approximately 71%–73% of the variance for mothers and fathers), with some influence of mothers’ genes and fathers’ shared environmental influences on their own parenting. Because large shared environmental influences were not indicated, they were excluded from the ECOT model for parsimony and model performance.

For NEAD, intraclass correlations suggest that adolescent externalizing problems were influenced by the adolescents’ genetic, shared, and nonshared environmental factors. Intraclass correlations suggest genetic influences explain between 29% and 40% of the variance in externalizing problems, shared environmental influences account for approximately 27%–38%, and nonshared environmental influences account for about 33% of the variance in externalizing problems. Intraclass correlations on externalizing problems in TOSS suggest the influence of mothers’ shared (approximately 40% of the variance for mothers and no variance for fathers), and parents’ nonshared environmental influences (approximately 52% of the variance for mothers and 62% of the variance for fathers), but little to no influence of mothers’ genes, and moderate influences of fathers genes on adolescent externalizing problems. Thus, there is potential for an environmental influence of parenting on externalizing problems, but the influence of shared genetic influences (A1′) indicative of passive rGE is unlikely.

Maternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems were moderately correlated in both samples, with similar magnitudes (r = .58 for NEAD, r = .52 for TOSS), as were paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems (r = .49 for NEAD, r = .46 for TOSS). We conducted cross-twin, cross-trait correlations (see Table 1) to gauge whether adolescents’ genes and environments and parents’ genes and environments contributed to these associations. Cross-twin, cross-trait correlations are limited by the phenotypic correlation. Therefore, in NEAD, adolescent-based genetic influences likely contribute the majority of the variance to the association between maternal and paternal negativity and externalizing problems (MZ correlations were .44 and .32, respectively), with some potential contribution of adolescent-based shared and nonshared environmental influences. This suggests that we will find evidence of evocative rGE in both mother and father models. In TOSS, parent-based environmental influences likely contribute to the covariation between parental negativity and externalizing problems, with potentially some mother-based genetic influences (see Table 1). Therefore, we could also find some, relatively small, environmental influences of parents on adolescents.

The ECOT Model

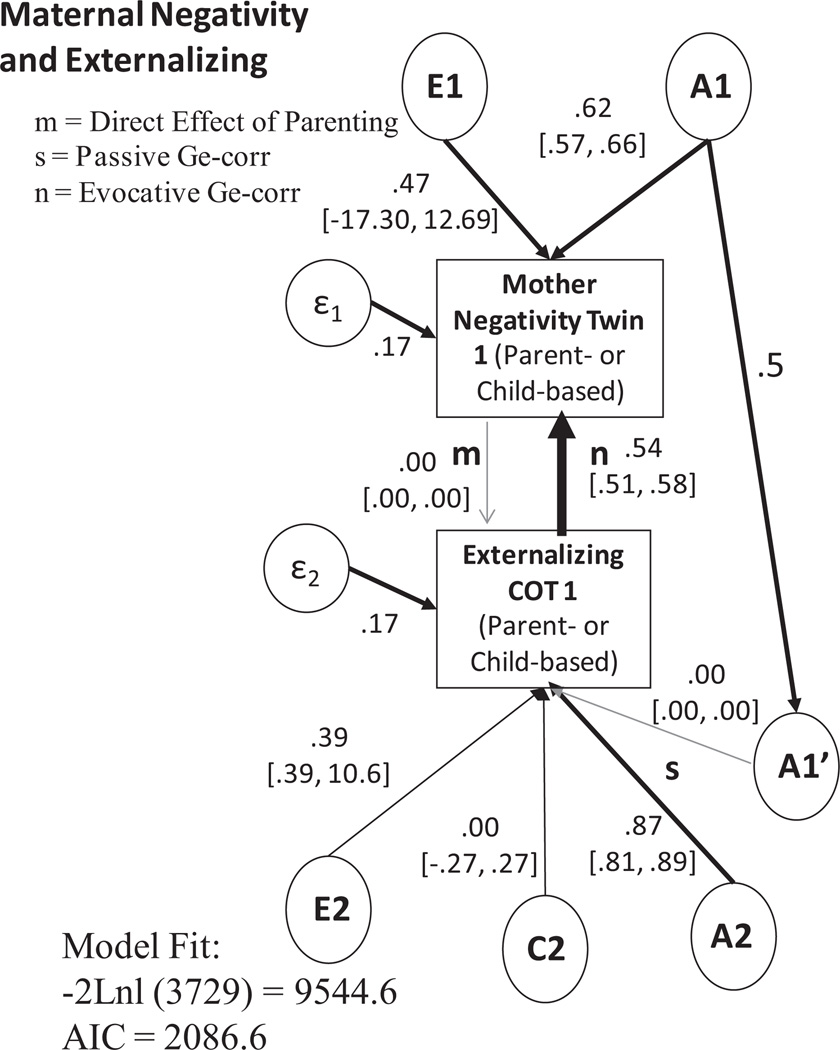

Maternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems

Results for the full model for maternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems are presented in Figure 2. The measurement error was modest across both phenotypes. There were significant influences of mothers’ genes and non-shared environment on maternal negativity. There were also significant influences of adolescents’ genes on their own externalizing problems. Paths n (evocative rGE) and A2 (adolescents’ genes) were significant, suggesting evocative rGE explains the correlation between adolescent externalizing problems and maternal negativity, while path m and path s were both nonsignificant, suggesting no passive rGE or direct environmental effects of maternal negativity on adolescent externalizing problems.

Figure 2.

Results for maternal negativity Extended Children of Twins (ECOT) model. This figure is reduced from Figure 1 in order to more succinctly present results. Unstandardized path estimates and 95% confidence intervals [in brackets] are provided for each estimated path. Significant paths are emboldened. Model fit statistics are provided in the lower left. A1 represents latent genetic influences of parents on their parenting, E1 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of parents on their parenting. A2 represents latent genetic influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; C2 represents latent shared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; E2 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems. A1′ represents the effect of genes shared by parents and adolescents on adolescents’ externalizing problems. Path m represents direct environmental effects of parenting on adolescents’ externalizing problems while path n represents child evocative effects of adolescents’ externalizing problems on parenting. Path s represents the influence of shared genes of parents and adolescents; significant path s and path m signify passive gene -environment correlation (rGE) while significant path n and either A2 or s signifies evocative rGE. ε1 and ε2 are the measurement error, and constrained to be equal.

Nested model fitting results confirmed results from the full model. Path m could be dropped without a decrement in model fit: full model, −2Lnl = 8187.5, df = 3185, Akaike information criterion [AIC] = 1807.1; without path m, −2Lnl = 8175.5, df = 3185, AIC = 1805.1, Δχ2(1) = 0.0, p > .05. However, dropping path n resulted in a decrement in model fit: without path n, −2Lnl = 8187.5, df = 3185, AIC = 1817.5, Δχ2(1) = 12.48, ρ < .05. Dropping each of the nonsignificant paths separately or together did not result in a decrement in model fit. Thus, the most parsimonious model included effects of A1, E1, N, and A2, −2Lnl = 8175.1, df = 3188, AIC = 1799.1, Δχ2(4) = 0.0, ρ > .05. As such, evocative rGE explained the correlation between maternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems.

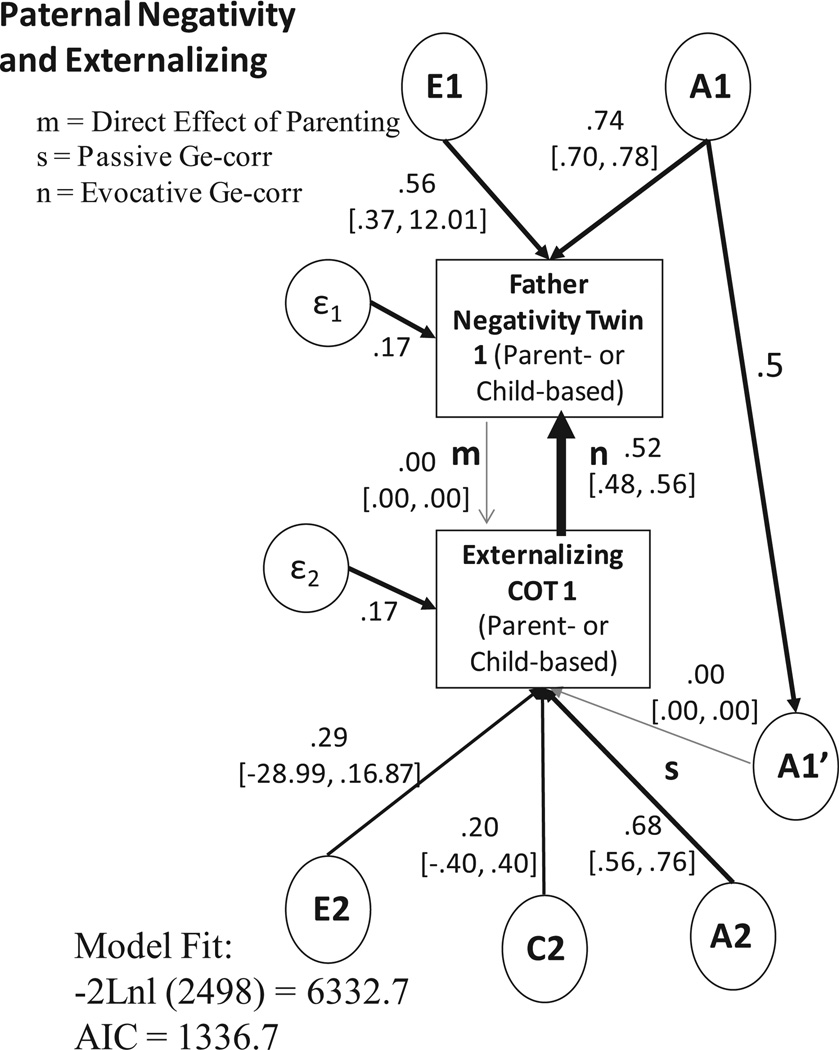

Paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems

Results for the full model for paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems are presented in Figure 3. Measurement error was modest across both phenotypes. Results for paternal negativity were remarkably consistent with results for maternal negativity. As with mothers, evocative rGE explained the correlation between paternal negativity and adolescent externalizing problems. Nested model fitting results generally confirmed results from the full model. Path m could be dropped without a significant decrement in model fit: full model, −2Lnl = 6332.7, df = 2498, AIC = 1336.7; without path m, −2Lnl = 6332.7, df = 2499, AIC = 1334.7, Δχ2(1) = 0, ρ > .05. However, dropping path n resulted in a decrement in model fit: without path n, −2Lnl = 6621.9, df=2499, AIC = 1623.9, Δχ2(1) = 289.2, ρ < .05. Dropping each of the nonsignificant paths from the full model separately or together did not result in a decrement in model fit. Thus, the most parsimonious model included effects of A1, E1, N, and A2, −2Lnl = 6337.4, df= 2502, AIC = 1333.4, Δχ2(4) = 4.7, ρ > .05.

Figure 3.

Results for paternal negativity Extended Children of Twins (ECOT) model. This figure is reduced from Figure 1 in order to more succinctly present results. Unstandardized path estimates and 95% confidence intervals [in brackets] are provided for each estimated path. Significant paths are emboldened. Model fit statistics are provided in the lower left. A1 represents latent genetic influences of parents on their parenting; E1 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of parents on their parenting. A2 represents latent genetic influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; C2 represents latent shared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems; E2 represents latent nonshared environmental influences of adolescents on their externalizing problems. A1′ represents the effect of genes shared by parents and adolescents on adolescents’ externalizing problems. Path m represents direct environmental effects of parenting on adolescents’ externalizing problems while path n represents child evocative effects of adolescents’ externalizing problems on parenting. Path s represents the influence of shared genes of parents and adolescents; significant path s and path m signify passive gene-environment correlation (rGE) while significant path n and either A2 or s signifies evocative rGE. ε1 and ε2 are the measurement error, and constrained to be equal.

Discussion

The present study found that evocative rGE explained the association between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems for both mothers and fathers. This suggests that parental negativity is partially a response to adolescents’ heritable externalizing problems. This study builds on previous studies by examining how adolescent externalizing problems contribute to rGE effects. Previous findings using the same samples and parenting measures used in the current study, but not employing the newly developed ECOT approach, suggested that evocative rGE contributed to maternal negativity, while passive and evocative rGE contributed to paternal negativity (Neiderhiser et al., 2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al., 2007). Our findings extend these conclusions by showing that adolescent’s genetically influenced externalizing problems contributed to the evocative rGE underlying maternal and paternal negativity identified in Neiderhiser et al. (2004; Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al., 2007).

Across studies, there is consistent evidence of evocative rGE for maternal negativity and the association between different forms of negative mothering behaviors and adolescent externalizing problems, despite differences in measurement and sample inclusions. Findings for fathers are somewhat less consistent. Like Neiderhiser, Reiss, Lichtenstein, et al. (2007), the present study suggests that evocative rGE plays an important role in paternal negativity and the association between paternal negativity and externalizing problems. However, there is evidence that paternal criticism has a direct environmental influence on externalizing problems (Narusyte et al., 2011). Narusyte et al. (2011) used the same parent-based twin sample and a different sample of adolescent twins to examine the role of rGE in a similar correlation: the associations between maternal and paternal criticism and adolescent externalizing problems. The present study differed from and expanded on Narusyte et al. (2011) in several ways. First, the present study used multimea-sure, multirater composites for parental negativity and multirater composites for externalizing problems instead of parent and youth self-report. Multimea-sure, multirater composites avoid single-measure bias (Bank et al., 1993) and may result in more general results capturing a broader spectrum of negative parenting and adolescent externalizing problems than the specific parenting behavior (parental criticism) and adolescent self-reported externalizing problems assessed in Narusyte et al. (2011).

Second, the present study used an adolescent sample of twins and siblings instead of an adolescent sample of only twins. The addition of nontwin siblings in the child-based twin design increased the power to detect shared environmental influences on adolescent externalizing problems, which, if present but unestimated, could inflate the estimate of genetic influences on externalizing problems. Thus, the present study provided a more conservative test of evocative rGE than Narusyte et al. (2011). The addition of nontwin siblings also increased the generalizability of findings beyond families of twins to nondivorced and stepfamilies of twins and nontwin siblings. Narusyte et al. (2011) reported limited power to detect evocative rGE (65% accuracy) in the association between fathering and externalizing problems because of the limited number of fathers who participated in the child-based twin sample. The present study included a larger sample of fathers in the child-based sample (approximately 400 vs. approximately 130 in Narusyte et al., 2011), increasing our power to detect evocative rGE for fathering compared to Narusyte et al. (2011) while maintaining a more conservative test because of the inclusion on nontwin siblings.

Thus, differences in findings for fathers could reflect power differences between samples, or may suggest that particular fathering behaviors have different effects on adolescent externalizing problems. Unfortunately, we do not have appropriate measures of parental criticism available in the NEAD study and are unable to definitively test whether differences in findings reflect differences in types of parenting behaviors. Further investigations using larger sample sizes and multiple measures of parenting are needed to fully understand these differences in findings across studies.

Transactions Between Parenting and Child Behavior

The present findings add to the growing evidence suggesting that the mechanism underlying associations between parenting and adolescent behavior problems is not a purely environmental mechanism, but instead is propagated through genotype–environment correlation processes (e.g., Narusyte et al., 2011). The present study was limited in testing theories of bidirectional influence between parents and adolescents because we had only a single measure of parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems. Longitudinal ECOT models are called for to test the changing role of rGE in associations between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing problems. There is evidence that child-based genetic effects increase from childhood to adolescence (e.g., Burt & Neiderhiser, 2009). Further, recent evidence suggests that the role of passive rGE on negative mothering may increase with children’s age, and that parents’ age also likely plays an important role in the rGE processes underlying negative parenting (Marceau et al., 2011). Together, this evidence suggests that parents’ and children’s genes are implicated in parent–child relationships across adolescence, though the present study only captures a snapshot of a dynamic developmental process.

Implications

The role of evocative rGE in associations between parental negativity and adolescent externalizing problems suggests that children’s genes, but not parents’ genes, are particularly influential for parent–adolescent relationships. That is, parental influence as a main effect was not important for the negative parent–adolescent relationship here. Theories of parental influence on child behaviors (i.e., social learning theories and coercive cycles) should be expanded to incorporate genotype–environment correlation as a mechanism of the developing negative parent–child relationship. The present findings also have practical implications. Finding evocative rGE and not that parenting exerts an environmental influence on externalizing problems during adolescence suggests that parents’ responsivity to, and relationship with, adolescents may be the optimal target for interventions aimed to reduce antisocial behavior, rather than simply targeting a reduction in negative parenting behaviors (Feinberg et al., 2001). For example, therapeutic interventions might be aimed at helping parents keep their cool by promoting positive coping strategies particularly when provoked by their adolescents as a way of reducing parent–adolescent relationship problems and adolescent externalizing problems, as opposed to aiming to reduce negative parenting behaviors generally, at all times.

Limitations and Future Directions

Evidence from molecular genetics and adoption studies suggests that gene–environment interaction may also be operating for the parent–adolescent relationship and adolescent externalizing problems (e.g., Beaver & Belsky, 2012; Delisi, Beaver, Vaughn, & Wright, 2009; Ge et al., 1996), though we could not test for it with this model. Similarly, there is evidence that assortative mating is particularly important to consider when studying offspring externalizing problems (e.g., Krueger, Moffitt, Caspi, Bleske, & Silva, 1998), but we could not control for assortative mating because the current formulation of the ECOT model only incorporates one parent at a time. So, results should be interpreted with caution, as the ECOT model simplifies the transactional processes and gene– environment interplay driving the association between parenting and externalizing problems. Similarly, although we tested direction of effects, the data are cross-sectional and correlational; therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution regarding causality. Finally, while we were able to use multirater composites, we were unable to include observer reports of parenting or externalizing problems, which could strengthen or change results. Observer reports were available in the NEAD study, but not for fathers in TOSS. Nonetheless, the present study makes an important contribution to the literature examining associations between parenting and child behavior by showing that parental negativity in adolescence is primarily a response to adolescents’ genetically influenced externalizing problems.

Acknowledgments

We thank the principal investigators and families of the Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden and the Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development project. Funding for the Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development project was provided by National Institute of Mental Health Grants R01MH43373, R01MH48825, and the William T. Grant Foundation; funding for the Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden was provided by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH54601. Additional funding was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (F31 DA033737), National Institute on Aging (F32 AG039165).

Contributor Information

Kristine Marceau, The Pennsylvania State University.

Briana N. Horwitz, The Pennsylvania State University

Jody M. Ganiban, George Washington University

David Reiss, Yale University.

Jurgita Narusyte, Karolinska Institutet.

Erica L. Spotts, Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research, NIH

Jenae M. Neiderhiser, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Duncan T, Patterson G, Reid J. Parent and teacher ratings in the assessment and prediction of antisocial and delinquent behaviors. Journal of Personality. 1993;61:693–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1993.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Parenting styles and adolescent development. In: Lerner RM, Petersen AC, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Encyclopedia of adolescence. Vol. 2. New York: Garland; 1991. pp. 746–758. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, Belsky J. Gene-environment interaction and the intergenerational transmission of parenting: Testing the differential-susceptibility hypothesis. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2012;83:29–40. doi: 10.1007/s11126-011-9180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Rieker J, Rende RD, Plomin R, DeFries JC, Fulker DW. Genetic mediation of longitudinal associations between family environment and childhood behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Are there meaningful etiological differences within antisocial behavior? Results of a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt S, McGue M, Iacono W. Environmental contributions to the stability of antisocial behavior over time: Are they shared or non-shared? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9367-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. How are parent-child conflict and childhood externalizing symptoms related over time? Results from a genetically informative cross-lagged study. Development & Psychopathology. 2005;17:145–165. doi: 10.1017/S095457940505008X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Neiderhiser JM. Aggressive versus non-aggressive antisocial behavior: Distinctive etiological moderation by age. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1164–1176. doi: 10.1037/a0016130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA. Externalizing behavior problems and discipline revisited: Nonlinear effects and variation by culture, context, and gender. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, O’Connor TG. Parent- child mutuality in early childhood: Two behavioral genetic studies. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:561–570. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delisi M, Beaver KM, Vaughn MG, Wright JP. All in the family: Gene × environment interaction between DRD2 and criminal father is associated with five antisocial phenotypes. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2009;36:1187–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M, Neiderhiser J, Howe G, Hetherington EM. Adolescent, parent, and observer perceptions of parenting: Genetic and environmental influences on shared and distinct perceptions. Child Development. 2001;72:1266–1284. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbaud Du Fort G, Boothroyd LJ, Bland RC, Newman SC, Kakuma R. Spouse similarity for antisocial behaviour in the general population. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:1407–1416. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Slutske WS, Turkheimer E, Emery RE, Harden KP, Heath AC, et al. Intergenerational transmission of childhood conduct problems: A children of twins study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:820–829. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Cadoret RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Yates W, Troughton E. The developmental interface between nature and nurture: A mutual influence model of child antisocial behavior and parent behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:574–589. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH. A zygosity questionnaire for young twins: A research note. Behavior Genetics. 1991;21:257–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01065819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML. Contributions of attachment theory to the understanding of conduct problems during the preschool years. In: Belsky J, Negworski T, editors. Clinical implications of attachment. Hillsdale, NJ: Earlbaum; 1988. pp. 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, Deklyen M. The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, Markell D. The resolution of cultural and biological inheritance: Informativeness of different relationships. Behavior Genetics. 1985;15:439–465. doi: 10.1007/BF01066238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kessler RC, Neale MC, Hewitt JK, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS. Testing hypotheses about direction of causation using cross-sectional family data. Behavior Genetics. 1993;23:29–50. doi: 10.1007/BF01067552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3) Serial No. 227. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz B, Marceau K, Neiderhiser JM. Family relationship influences on development: what can we learn from genetic research? In: Kendler K, Jaffee S, Romer D, editors. The dynamic genome and mental health: The role of genes and environments in youth development. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Parenting: A genetic-epidemiologic perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:11–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klahr AM, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA. The association between parent-child conflict and adolescent conduct problems over time: Results from a longitudinal adoption study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:46–56. doi: 10.1037/a0021350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopik VS, Heath AC, Jacob T, Slutske WS, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, et al. Maternal alcohol use disorder and offspring ADHD: Disentangling genetic and environmental effects using a children-of-twins design. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1461–1471. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bleske A, Silva PA. Assortative mating for antisocial behavior: Developmental and methodological implications. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:173–186. doi: 10.1023/a:1021419013124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, et al. Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson H, Viding E, Rijsdijk FV, Plomin R. Relationships between parental negativity and childhood antisocial behavior over time: A bidirectional effects model in a longitudinal genetically informative design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:633–645. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Tuvblad C, Larsson H, Carlstrom E. The Swedish Twin study of CHild and Adolescent Development: The TCHAD-Study. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:67–73. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Dishion T. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;94:68–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC, Nichols RC. Heredity, environment and personality. Austin: University of Texas Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Losoya SH, Callor S, Rowe DC, Goldsmith HH. Origins of familial similarity in parenting: A study of twins and adoptive siblings. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1012–1023. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SK, Turkheimer E, D’Onofrio BM, Mendle J, Emory RE, Slutske WS, et al. A genetically informed study of the association between harsh punishment and offspring behavioral problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:190–198. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton H. Child and parent effects in boys’ conduct disorder: A reinterpretation. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:683–697. [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Neiderhiser JM. Tolan P, Leventhal B, editors. Influences of gene environment interaction and correlation on disruptive behavior in the family context. Advances in clinical child and adolescent psychopathology: Vol. I. Disruptive behavior. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, Neiderhiser JM, Ganiban J, Spotts E, Lichtenstein P, Reiss D. Age moderates genetic and environmental influences on parent– child conflict and closeness: Implications for genotype– environment correlation; Montreal, Canada. Paper presented at the biennial meeting for the Society for Research on Child Development.Mar, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Elkins I, Walden B, Iacono WG. Perceptions of the parent-adolescent relationship: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:971–984. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Sharma A, Benson P. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles DR, Carey G. Genetic and environmental architecture of human aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;7:207–217. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narusyte J, Andershed A-K, Neiderhiser JM, Lich-tenstein P. Aggression as a mediator of genetic contributions to the association between negative parent- child relationships and adolescent antisocial behavior. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;16:128–137. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0582-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narusyte J, Neiderhiser JM, Andershed AK, D’Onofrio BM, Reiss D, Spotts E, et al. Parental criticism and externalizing behavior problems in adolescents: The role of environment and genotype- environment correlation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:365–376. doi: 10.1037/a0021815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narusyte J, Neiderhiser JM, D’Onofrio B, Reiss D, Spotts EL, Ganiban J, et al. Testing different types of genotype-environment correlation: An extended children-of-twins model. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1591–1603. doi: 10.1037/a0013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC. Mx: Statistical modeling. 5th ed. Richmond: University of Virginia, Department of Psychiatry; 1999. Computer software. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Lichtenstein P. The Twin and Offspring Study in Sweden: Advancing our understanding of genotype-environment interplay by studying twins and their families. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 2008;40:1116–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington EM. The Nonshared Environment in Adolescent Development (NEAD) project: A longitudinal family study of twins and siblings from adolescence to young adulthood. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:74–83. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington E, Plomin R. Relationships between parenting and adolescent adjustment over time: Genetic and environmental contributions. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:680–692. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Lichtenstein P, Spotts EL, Ganiban J. Father-adolescent relationships and the role of genotype-environment correlation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:560–571. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, Spotts EL, Hansson K, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on mothering of adolescents: A comparison of two samples. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:335–351. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols RC, Bilbro WC., Jr The diagnosis of twin zygosity. Acta Genetica. 1966;16:265–275. doi: 10.1159/000151973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Deater-Deckard K, Fulker D, Rutter M, Plomin R. Genotype-environment correlations in late childhood and early adolescence: Antisocial behavioral problems and coercive parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:970–981. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Fisher PA. Recent developments in our understanding of parenting: Bidirectional effects, causal models, and the search for parsimony. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of parenting: Practical and applied parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 5. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit G, Arsiwalla D. Commentary on special section on “bidirectional parent-child relationships”: The continuing evolution of dynamic, transactional models of parenting and youth behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:711–718. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R. Genetics and experience: The interplay between nature and nurture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE. Behavioral genetics: A primer. 2nd ed. New York: Freeman; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Cederblad M, Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, Elthammar O, Neiderhiser JM, et al. Genetic probes of three theories of maternal adjustment: II. Genetic and environmental influences. Family Process. 2001;40:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4030100261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM, Hetherington EM, Plomin R. The relationship code: Deciphering genetic and social influences on adolescent development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype greater than environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, D’Onofrio BM, Turkheimer E, Ganiban JM, Spotts EL, Lichtenstein P, et al. A genetically informed study of associations between family functioning and child psychosocial adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:707–725. doi: 10.1037/a0021362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, Bell R. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Eaves LJ. Analysing the contributions of genes and parent-child interaction to childhood behavioural and emotional problems: A model for the children of twins. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:347–356. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Maes H, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of parental depression to children’s depression and conduct disturbance: An extended Children of Twins study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:734–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Maes H, Eaves LJ. Unraveling the effect of genes and environment in the transmission of parental antisocial behavior to children’s conduct disturbance, depression and hyperactivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;53:668–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Barrera M. A longitudinal examination of the reciprocal relations between perceived parenting and adolescents’ substance use and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Tully EA, Iacono W, McGue M. An adoption study of parental depression as an environmental liability for adolescent depression and childhood disruptive disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1148–1154. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh ZY, Jenkins J, Pepler D. A transac-tional analysis of maternal negativity and child exter-nalizing behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2010;34:218–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zill N, Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD. Behavior, achievement, and health problems among children in stepfamilies: Findings from a national survey of child health. In: Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD, editors. Impact of divorce, single parenting, and stepparenting on children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 325–368. [Google Scholar]