Abstract

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects millions of people worldwide and about a half million people die every year. India represents the second largest pool of chronic HBV infection worldwide with an estimated 40 million infected people. The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in pregnant women is shown to be 0.82 per cent with the risk of mother-to-child vertical transmission. Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positivity indicates replicative form of HBV which may play a role in immunotolerance in utero by crossing the placenta. In case of HBeAg positivity and high viral load of mother, HBV immunoglobulin is preferably given along with HBV vaccination. Antiviral therapy is recommended for use in the third trimester of pregnancy to reduce the perinatal transmission of HBV, however, use of antiviral therapy should be individualized during pregnancy. Chronic HBV infection in neonates is linked with strong presence of Tregs (T regulatory cells) and defective CD8 T cells pool to produce interferon (IFN)-γ. T cell receptor (TCRζ) chain defects were also associated with decreased CD8 T cell dysfunction. Decreased TCRζ expression could be due to persistent intrauterine exposure of the viral antigens early in embryonic development leading to immune tolerance to HBV antigens in the newborns positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg+ve). Therefore, due to HBV infection, T cell tolerance to HBV-antigen may probably leave the newborn as a chronic carrier. However, HBV vaccination may have benefits in restoring acquired immunity and better production of HBV specific antibodies.

Keywords: Chronic infection, HbeAg, HbsAg, hepatitis B virus (HBV), perinatal, pregnancy

Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant mothers and transmission to newborns

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection affects over 240 million people worldwide and about a half million people die every year due to the acute or chronic consequences leading to liver failure and liver cancer1. HBV is present in blood, saliva, semen, vaginal secretions, and menstrual blood of infected individuals2.

In Southeast Asia and China, the prevalence of HBV infection among women of child-bearing age is as high as 10-20 per cent3. India represents the second largest pool of chronic HBV infection worldwide with an estimated 40 million people. In India, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in pregnant females is 0.82 per cent4 and during pregnancy, hepatitis B virus infection presents the risk of mother-to-child (vertical) transmission.

To analyze the source of acquisition of HBV infection in chronic HBV infected patients, mothers of 384 chronic hepatitis B index patients were screened for HBV infection. The mothers of 40.1 per cent index patients were positive for HBsAg. The mothers of 34.1 per cent index patients were positive only for antibodies (total anti-HBc and/or anti-HBe) indicating that the mothers were exposed to HBV infection some time in past5. These data provide substantial evidence of present or past HBV infection in mothers of chronic HBV patients, suggesting possible perinatal transmission. It could be possible that one third of mothers, who were initially hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive, could have cleared the infection during post-partum period and remained positive only for HBV antibodies5. Therefore, vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus could be one of the main causes of chronic HBV infection in our country.

The neonates born to mothers infected with chronic hepatitis B, have 90 per cent risk of acquiring chronic HBV infection and its persistence6. In contrast, when HBV is acquired during adulthood, only 5-10 per cent of adults develop persistent chronic HBV infection7. Most of the developed countries screen all pregnant women for HBV infection, however, in the developing countries it depends upon the risk factors. In India, there is no consistent policy of screening the pregnant women across the country. A meta-analysis of prevalence of hepatitis B in India showed 2.4 per cent prevalence in general population8. However, the prevalence rate of HBsAg positivity in pregnant women varied from 1-9 per cent in different parts of the country and e antigen (HBeAg) positivity rates among them varied from 4.8-68.7 per cent8.

A large single centre study from north India of 20,104 pregnant women showed a chronic HBsAg positivity rate of 1.1 per cent9. Majority of pregnant women with viral hepatitis B are considered as chronic hepatitis B infected but a few may develop acute hepatitis in the third trimester of pregnancy resulting in 1 per cent fulminant hepatitis10,11. During pregnancy, acute viral hepatitis involves a particular risk both for the mother and the baby.

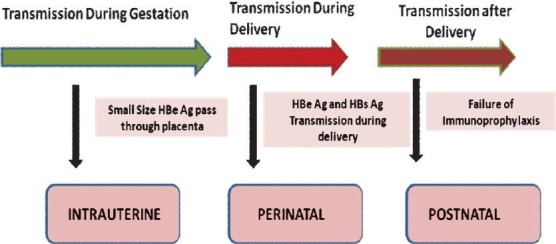

Of the two secretory proteins; HBsAg and HBeAg, HBsAg does not usually cross the placenta, however, small sized HBeAg passes through the placental barrier even with low maternal viral load titre12,13 (Fig. 1). In newborn, transplacental HBeAg can be detected at one month of age but it would disappear before 4 months of age. However, in a few, infected newborns with HBV viral titres, persistent detection of HBeAg for more than 4 months strongly indicates HBV chronicity14,15. It is also observed that anti-HBc (antibodies to core antigen) positivity can be detected more than anti-HBe in the babies born to hepatitis B infected mothers12,13. Therefore, anti-HBe till one year of age and anti-HBc till two years of age represent the transplacental maternal antibodies to the virus, and may not be an indicator of present active or past HBV infection in babies born to hepatitis B infected mothers.

Fig. 1.

Secretory proteins crossing the placenta and vertical transmission through during and after delivery.

Hepatitis B envelope antigen spillage through placenta induces HBV specific T cell tolerance in utero16 and intrauterine infection could be the main cause of the failure of immunoprophylaxis17,18,19 (Fig. 1). However, there are several evidences to show that the incidence of intrauterine transmission is rare and only happens in case of placental leakage20,21.

Infants born to HBeAg positive mothers are likely to be infected and progress to chronicity, however, infants born to HBsAg positive mothers develop acute hepatitis and less likely to progress to chronicity13. In north India, HBeAg positivity was 7.8 per cent, and risk of perinatal transmission was 18.6 per cent from HBsAg positive mothers vs. 3 per cent among infants of HBsAg-negative mothers22,23.

Effect of HBs and HBe antigen on pregnancy

HBV infection does certainly affect the outcome of pregnancy and influence spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or prematurity. Increased frequencies of reproductive casualties were reported, in pregnant women with acute or chronic hepatitis B infection24. With HBV infection, the incidence of preterm birth observed was quite high around 21.9 vs 12.1 per cent in healthy controls25.

The gestational diabetes and antepartum haemorrhage were also associated with chronic hepatitis B infection26. In a case-control study, HBeAg positivity was proved to be more important with high HBV DNA levels in transmission of HBV to infants27. HBeAg positivity indicates replicative form of HBV which may play a role in the immunotolerance in utero by crossing the placenta28. In HBV genotype C, HBeAg seroconversion is longer, which may be the reason for higher perinatal transmissions in this genotype29. Therefore, in prenatal screening of pregnant women, it is important to check the HBeAg status along with HBsAg.

Serovaccination of the newborn

There are chances of vertical transmission and resulting chronic hepatitis B infection in a newborn from a chronic hepatitis B infected mother with HBsAg positivity30. Therefore, vaccination against HBV has been implemented recently to prevent HBV infection predominantly acquired perinatally or in childhood31. In many countries, immunization programmes for HBV are implemented, despite this HBV prevalence is not decreasing32. This may be due to incomplete vaccination or inefficacy of the immunization programme. Screening for HBsAg is essential in all pregnant women. All infants born to mothers who are HBsAg positive must receive a serovaccination against this virus, by intramuscular injection of HBV vaccine and of hepatitis B immune globulin (H-BIG, 100 or 200 IU), in the first 12 hours of birth9. Despite improved health policies, there is no national hepatitis B immunization programme in India, thus chronic HBV infection still remains a considerable medical burden, affecting young adults.

HBV vaccine

HBV vaccines are directed against common antigenic epitopes of genotype A and D of HBV surface region, which provide sufficient cross-protection across genotypes to prevent infection33. Hepatitis B vaccination alone can prevent transmission in 80-95 per cent of cases, however, in case of HBeAg positivity and high viral load of mother, HBV immunoglobulin is preferrablly given along with HBV vaccination at different sites. Although HBV vaccination along with H-BIG has been reported effective in many studies and transmission rates can be reduced between 0 and 14 per cent34, the recent data from India showed no significant effect of the combination of vaccination and H-BIG vs. HBV vaccination alone, especially when the viral load is very high during pregnancy35.

In fact, in many other studies, standard passive-active immunoprophylaxis with hepatitis B immunoglobulin and the hepatitis B vaccine had a failure rate as high as 10 to 15 per cent36 and these failures are associated with high maternal serum HBV DNA levels37. In some cases, vaccine failures are also associated with intrauterine infection in women during pregnancy38. Therefore, it is being considered that HBV vaccination alone or along with HBV immunoglobulin is not sufficient and may be prevented by nucleotide analogue therapy. As antiviral therapies are being used to prevent HIV transmission from mother to child, similar strategy could be beneficial in the case of HBV.

Use of antivirals during pregnancy: its safety and concern

Levels of HBV DNA and alamine transaminase (ALT) are highly variable during entire course of pregnancy. In a few cases, HBV DNA levels seemed to rise in the third trimester or in the post-partum period, otherwise for entire duration of pregnancy the levels of HBV DNA remain stable. There are limited data available on anti-viral treatment during pregnancy which show symptomatically or asymptomatically HBV infection clearance during subsequent pregnancies and postpartum37,38.

Pregnant women with a low HBV viral load do not require immediate treatment, because due to the passive immunization and active HBV vaccination of the newborn, chances of acquiring infection due to perinatal transmission are negligible. Treatment of the mother can, therefore, be postponed until after the birth. However, with high HBV viral load (>105 copies/ml in serum), strategy for treating with antivirals during the last trimester of pregnancy is being considered39. Antiviral therapy was also used in pregnant woman with acute exacerbation of hepatitis B, as this was quite effective in reducing possible HBV-associated hepatitis flares or reactivation and made a difference to maternal morbidity and mortality before hepatic decompensation40,41. However, vertical transmission has been reported even with the treatment of hepatitis B during the pregnancy and when there was an undetectable viral load at delivery39.

In antivirals, lamivudine was the first drug which was used to diminish viral load and considered effective in the third trimester of pregnancy and resulted in reduced risk of chronic hepatitis B in the child41,42,43. Oral dose of 150 mg of lamivudine every day during the last month of pregnancy reduced serum HBV DNA concentration and normalised ALT levels till the time of delivery. In the lamivudine-treated group, only 12.5 per cent infants were tested positive for HBsAg in comparison to 28 per cent untreated historical control subjects. Therefore, lamivudine therapy was considered effective in reducing HBV transmission from highly viraemic mothers to their infants who received passive/active immunization. Despite, the fact that lamivudine therapy leads to suppression of the HBV DNA to undetectable levels in the mother, there is a case report of a newborn with raised ALT levels and positive for HBV DNA at birth, followed by developing chronic hepatitis B virus infection44.

Recently, telbivudine was evaluated for its efficacy and safety in the third trimester of pregnant women in one of the clinical trials and also compared with lamivudine41,44. Both antivirals, showed reduction in HBV DNA levels in mothers from log 8 to log 2. Newborns were given hepatitis B vaccination as well as immunoglobulin within 24 h of birth and completed vaccine schedule. After one year of birth, 18 per cent of children in lamivudine group showed HBsAg positivity, however, in telbivudine group only 2 per cent children showed HBsAg positivity. Therfore, telbevudine was considered to be better antiviral than lamivudine41. Use of antivirals from the first trimester showed more birth defects than their use in third trimester. Usage of recent antivirals in the first trimester, including emtricitabine, tenofovir, lamivudine, telbivudine, and adefovir showed more than 1.5 fold increase in overall birth defects41.

Most of the antiviral data support lamivudine and tenofovir usage in the pregnancy than adefovir and entecavir, as safety of entecavir is questionable. The global recommendations are to use tenofovir, lamivudine, and telbivudine during pregnancy and substantial registry evidence positively supports the use of tenofovir, which is a potent inhibitor of HBV44. However, in the case of lamivudine or telbivudine antiviral therapy, genotypic resistance should be assessed during treatment45.

Antiviral therapy is recommended to continue in post-partum period but the safety of anti-viral therapy during lactation period is a concern. Though HBsAg has been detected in the breast milk, but globally breast feeding has not been contraindicated in HBsAg positive mothers46. There are not many studies discussing the effects of antiviral therapy during lactation period47,48, however, a study on lamivudine treated pregnant women showed that infant received only 2 per cent of recommended antiviral dose through breast milk and the tenofovir treated HIV group showed only 0.03 per cent release of recommended dose in breast milk49.

Antiviral therapy might not prevent perinatal transmission of HBV infection in every newborn, therefore, use of antivirals during pregnancy need to be individualized and as the evaluation and management of abnormal liver tests in the pregnant women is challenging, importance of understanding case by case natural history of chronic HBV infection in the peri-partum period is extremely vital.

After birth, HBsAg positivity in children varies. In India, children below 15 yr have 1.3-12.7 per cent HBsAg positivity, whereas in other countries it ranges from 0-7.8 per cent3,4,5. Ultimately children after perenatal transmission with detectable HBV DNA levels are being treated with antivirals and interferon50, however, the success rate and adverse effects need to be determined.

Role of human leukocyte antigens (HLA)

The implantation of a fertilized ovum followed by placental and foetal development can be compared to a transplanted graft having both maternal and paternal HLA molecules. The foetal derived placental trophoblasts ensure survival by avoiding rejection from the maternal immune system and evading infection. The trophoblast cells lack expression of classical HLA class I and II molecules, express HLA-G, which is instrumental in preventing placental cell death by maternal NK cells in maternal deciduas51.

Pregnancy supports HBV infection

The liver also plays a crucial role in the metabolism of different hormones, including estrogens and progesterone. The normal course of pregnancy is bound to have a number of physiological changes and these changes may affect the normal course of chronic hepatitis B infection in infected women52,53,54. During pregnancy, successful foetal development is necessary by eliciting poor immune response against foetal antigens. Therefore, weak immunity of the mother might allow HBV viral replication and increases the chances of perinatal transmission of HBV infection in children.

Sex hormones such as androgens, estrogens and progestrone can directly interact with the cells of the immune system, thus impacting the development of immune responses. The female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone have been implicated as playing a role in modulating the local immune system and altering cytokines during pregnancy.

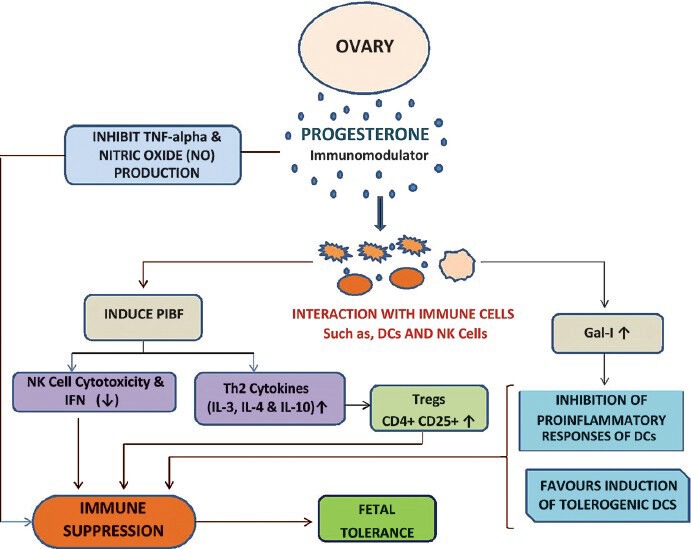

Progesterone, a hormone associated with the maintenance of pregnancy, is immunosuppressive and decreases NK cell cytotoxicity, inhibits nitric oxide (NO) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α production. Progesterone induced binding factor inhibits the activity of dendritic cells (DCs) that generate proinflammatory responses and favour the induction of tolerogenic DCs. It also controls the activity of natural killer (NK) cells and the differentiation of T cells into T helper cell type 2 (Th2) like clones (Fig. 2). Therefore, progesterone mediates the immunological effects, and induces the production of Th2 dominant cytokines like IL-3, IL-4, and IL-1055 (Fig. 2). The Th2 phenotype induced by progesterone is a prerequisite for the maintenance of pregnancy, which is associated with the susceptibility and the existing disease exacerbation56,57. The anti-inflammatory properties of progesterone prevent the development of Th1 responses that could result in foetal abortion58.

Fig. 2.

Release of hormones induce immune suppression and fetal tolerance during pregnancy.

In contrast to progesterone, estrogen is considered a proinflammatory mediator. Estrogen has been shown to stimulate the production of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF59,60, which is known to directly interact with the interferon (IFN)-γ promoter61, and further has been shown to enhance antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses62. The ability of estrogen to drive proinflammatory, Th1-associated immune responses induces higher concentrations of the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and IFN-γ. Th1 responses are associated with protective immunity and favour disease resolution. Therefore, progesterone favours Th2 response which protects foetal development and estrogen leads to Th1 response, which favours HBV disease resolution.

Pregnancy being a relatively immunosuppressed state, some of the chronic hepatitis B infected mothers may develop hepatitis flare or fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) due to immune restoration during the peri-partum period63,64,65. Generally, after delivery a significant increase in liver disease activity is being observed. , Overt liver dysfunction was maximum, observed in 43 per cent of mothers who were HBeAg positive within the first post-partum month66. These robust immune responses have cleared HBeAg in 12.5 per cent of mothers during the first month of post-partum period67.

HBV infection and T cell immunity

HBV is not cytopathogenic, still HBV infection carries a significant risk of developing severe liver diseases, including chronic hepatitis B (CHB), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HBV specific T cells mediated host immune response plays an important role in viral clearance as well as viral persistence which leads to chronicity as well as HCC67. Different HBV genotypes have been found in different ethnicity and global locations. Mechanism of immune tolerance may be influenced by different HBV markers and it is observed that exposure of the immature immune system in uterus to transplacental HBeAg induces immunotolerance leading to low HBeAg sero-conversion rates in children68,69.

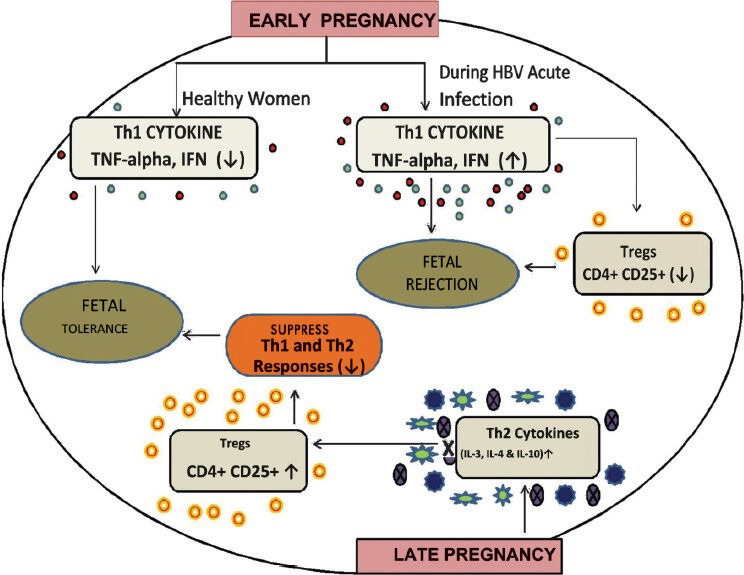

The constant immunologic changes that occur during pregnancy appear to mostly occur locally, however, these changes alter the maternal immune system grossly during gestation. Increase in systemic inflammation also results in different complications related to pregnancy and delivery70. Infiltrations of virus- non specific inflammatory cells in the liver also participate actively in HBV-associated liver pathogenesis. The downregulation of Th1 cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ was found in early pregnancy71. Therefore, a delicate balance of cytokine effects is necessary because overproduction of IFN-γ during the first trimester of human pregnancy leads to foetal rejection. As pregnancy progresses, the most compatible tilt occurs towards the Th2-type cytokine profile such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, and IL-25 and a T repressor type 1 (Tr1) or T-helper type 3 (Th3) such as TGF-β and IL-10 and away from Th1-type cytokines72,73. When Th2-like activity is increased during pregnancy, the elevated immune suppressive CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells suppress both Th1-like and Th2-like immunity against paternal/foetal alloantigens and checks IFN-γ reactions during pregnancy74,75 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Role of regulatory T-cells in regulating Th1/Th2 response leading to fetal rejection of fetal tolerance.

These alterations in the immune system during pregnancy induces a surge in cell mediated immunity cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, which could play a significant role in clearing the underlying HBV infection in HBsAg positive mothers during pregnancy and thereby help to tailor therapy after delivery to enhance the clearance of HBV72.

During pregnancy, the regulatory T cells suppress Th1 response and induce Th2 type immunity, contributing to an inadequate immune response against the virus with rise in viral load and decline in ALT levels76. A retrospective study has observed that in nearly 50 per cent of HBsAg positive pregnant mothers, after delivery there is increase in ALT when the immune status recovers which also influences with more maternal morbidity77,78.

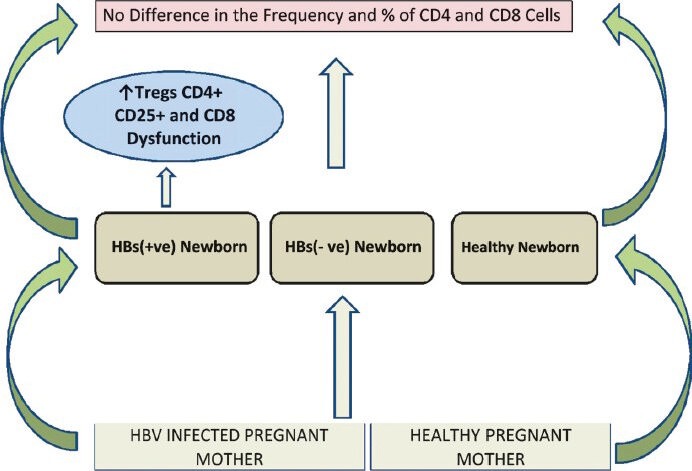

The precise roles of the hormones and cytokines alterations happening during “immunological orchestra” of pregnancy have not been clearly studied in HBsAg positive mothers. A study focused on the immune cells in HBsAg positive and negative mothers and their newborns. This study revealed that there was no difference in the frequencies or percentage of CD4, CD8 T cells in HBsAg+ve mothers and their newborns compared to HBsAg-ve and healthy mothers79. Then question is how the HBsAg+ve newborns develop chronic liver disease at a later stage of life. Shrivastava et al76 have analysed the immune cells functionality. When functional assays were performed for CD8 T cells, functionality was compromised at birth in HBsAg+ve newborns. Along with non functional CD8 T cells, presence of higher levels of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells was also observed, which probably was instrumental in establishing chronic infection in neonates (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immune response in HBV infected pregnant mothers and its outcomes.

It is known that the regulatory T cells suppress the proliferation, cytokine-production (IFN-γ, IL-2), cytolytic activity of naïve and antigen specific CD4 and CD8 T cells, functions of antigen presenting cells (APCs) and B cells through secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 or TGF-β80. These specialized regulatory T cells could possibly facilitate immune tolerant environment of newborns preventing the development of mature protective immune response and also support Medawar hypothesis; “Antigen encountered during fetal life induces a state of acquired immunological tolerance and mammals exposed to foreign homologous tissue cells during fetal life never react immunologically, or react to a limited degree only”81. Initially immune tolerance was also considered due to deletion or inactivation of T cells82 and, therefore, neonatal period has been viewed as a ‘window of opportunity’ for inducing tolerance to specific antigen83. At the time of birth with HBV infection, T cell tolerance to HBV-Ag may probably leave the newborn as a chronic carrier. Therefore, one aspect of chronic HBV infection in neonates is linked with strong presence of Tregs (regulatory T cells) and another aspect is why CD8 T cells capacity to produce IFN-γ and CD107a cytotoxicity decreased. In the literature, TCR signaling defects were significantly linked with functionality of T cells, in many diseases, downregulated expression of TCRζ chain on CD8 T cells have been observed, TCRζ chain defects eventually lead to decreased TCRζ expression positively correlated with decreased CD8 T cell dysfunction84,85. Decreased TCRζ expression could be due to persistent intrauterine exposure of the viral antigens early in embryonic development leading to immune tolerance to HBV antigens in the HBsAg+ve newborns.

Shrivastava et al78 also observed that HBsAg+ve newborns had lower expression of chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5 on CD4+ and CD8+T cells at birth. In many chronic diseases, presence of chemokines and toll like receptor was also not observed on leuckocytes, which may eventually contribute to infection persistence86,87.

Till date, there are only phenotypic studies which suggested possible defects in cell setting and mechanisms, in which diminished expression of TCRζ chain associated with CD8 T cell dysfunction in HBsAg+ve newborns was observed compared to HBsAg-ve and healthy uninfected newborns78. These observations add a new perspective to our growing understanding of the key mechanisms by which HBV could promote T cell dysfunction related to the loss of TCRζ chain expression. Additionally, we also speculate the role of T regs in the setting of immune tolerance.

The predisposition of newborns to infections has been attributed to defects in both the humoral and cellular arms of the adaptive immune responses. Infants with a diminished pool of B and T lymphocytes show lower serum complement levels and impaired antigen presenting ability of DCs and eventually reduced immunoglobulin production of B cells even after regular vaccination88,89,90. Development of mature B cells from naïve population is very important and HBV viral infection in adults are characterized by increased number of activated and exhausted B cells, increased levels of short lived plasma B cells or immature transitional B cells or decreased memory B cell response91,92,93.

There was a general tendency of higher levels of transitional B cells and lower memory B cells in HBsAg+ve newborns as compared to HBsAg-ve newborns immediately at birth. After 12 months post HBV vaccination, immature transitional B cells were declined and there was a rise in memory B cell with increased frequencies of CD69+ and CCR5+ activated memory B cell subpopulation93. The improved B cell responses suggest that HBV vaccination is somehow beneficial for improving the overall immune competency in HBsAg +ve newborns, but to understand the precise mechanism of disease progression further, larger cohort and long-term studies are needed.

In summary, higher levels of immunosuppressive T regulatory cells and CD8+ T cell dysfunction in HBsAg +ve newborns are suggestive of already established chronic and immune tolerant state of HBV infection at birth during vertical transmission. However, HBV vaccination may have benefits in restoring acquired immunity and better production of HBV specific antibodies.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Hepatitis B: World Health Organization fact sheet No 204 (July 2012) [accessed on July 1, 2012]. Available from: http://www.who.int/ mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en .

- 2.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CJ, Wang LY, Yu MW. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(Supp):E3–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee S, Ravishankar K, Chatterjee R, Narang A, Kinikar A. Hepatitis B Prevalence during pregnancy. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:1005–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hissar S, Sarin SK, Kumar M, Kazim SN, Tarun KG, Pande C, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B virus infection is predominantly perinatal in the Indian subcontinent. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:S–723. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C. Effect of hepatitis B immunisation in newborn infants of mothers positive for hepatitis B surface antigen: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:328–36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38719.435833.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeff LB, Beebe GW, Hoofnagle JH, Norman JE, Buskell-Bales Z, Waggoner JG, et al. A serologic follow-up of the 1942 epidemic of post-vaccination hepatitis in the United States Army. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:965–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704163161601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batham A, Narula D, Toteja T, Sreenivas V, Puliyel JM. Sytematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of hepatitis B in India. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:663–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pande C, Sarin SK, Patra S, Bhutia K, Mishra SK, Pahuja S, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and virological profile of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women in India. J Med Virol. 2011;83:962–7. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gambarin-Gelwan M. Hepatitis B in pregnancy. Clin Liver Dis. 2007;11:945–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lao T, Chan B, Leung W, Ho L, Tse K. Maternal hepatitis B infection and gestational diabetes mellitus. J Hepatol. 2007;47:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elefsiniotis IS, Papadakis M, Vlahos G, Daskalakis G, Saroglou G, Antsaklis A. Clinical significance of hepatitis B surface antigen in cord blood of hepatitis B e-antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B virus-infected mothers. Intervirology. 2009;52:132–4. doi: 10.1159/000219852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, Heron LG, et al. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust. 2009;190:489–92. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milich D, Liang TJ. Exploring the biological basis of hepatitis B e antigen in hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2003;38:1075–86. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen MT, Billaud JN, Sallberg M, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV, Jones J, et al. A function of the hepatitis B virus precore protein is to regulate the immune response to the core antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14913–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406282101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Q, Yu G, Yu H, Lu Q, Gu X, Dong Z, et al. A randomized control trial on interruption of HBV transmission in uterus. Chin Med J. 2003;116:685–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang JS, Zhu QR. Infection of the fetus with hepatitis B eantigen via the placenta. Lancet. 2000;355:989. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Zhang J, Yang H, Li X, Wen S, Guo Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of HBV DNA level and HBeAg titer inhepatitis B surface antigen positive mothers and their babies:HBeAg passage through the placenta and the rate of decay in babies. J Med Virol. 2003;71:360–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vranckx R, Alisjahbana A, Meheus A. Hepatitis B virus vaccination and antenatal transmission of HBV markers to neonates. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:135–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1999.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu DZ, Yan YP, Choi BC, Xu JQ, Men K, Zhang JX, et al. Risk factors and mechanism of transplacental transmission of hepatitis B virus: a case-control study. J Med Virol. 2002;67:20–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao ZJ, Zhang L, Xu JQ, Xu DZ, Men K, Zheng JX, et al. Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus: a Chinese experience. J Med Virol. 2011;83:791–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nayak NC, Panda SK, Zuckerman AJ, Bhan MK, Guha DK. Dynamics and impact of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus in North India. J Med Virol. 1987;21:137–45. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittal SK, Rao S, Rastogi A, Aggarwal V, Kumari S. Hepatitis B - potential of perinatal transmission in India. Trop Gastroenterol. 1996;17:190–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavel A, Tirsia E, Maior E, Cristea A. Detrimental effects of hepatitis B virus infection on the development of the product of conception. Virologie. 1983;34:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong S, Chan LY, Yu V, Ho L. Hepatitis B carrier and perinatal outcome in singleton pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 1999;16:485–8. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-6802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safir A, Levy A, Sikuler E, Sheiner E. Maternal hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus carrier status as an independent risk factor for adverse perinatal outcome. Liver Int. 2010;30:765–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tse KY, Ho LF, Lao T. The impact of maternal HBsAg carrier status on pregnancy outcomes: a case-control study. J Hepatol. 2005;43:771–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh AE, Plitt SS, Osiowy C, Surynicz K, Kouadjo E, Preiksaitis J, et al. Factors associated with vaccine failure and vertical transmission of hepatitis B among a cohort of Canadian mothers and infants. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:468–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livingston SE, Simonetti JP, Bulkow LR, Homan CE, Snowball MM, Cagle HH, et al. Clearance of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B and genotypes A, B, C, D, and F. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1452–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Broderick AL, Jonas MM. Hepatitis B in children. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:59–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dusheiko G. Interruption of mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B: time to include selective antiviral prophylaxis? Lancet. 2012;379:2019–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Z, Li L, Ruan B. Impact of the implementation of a vaccination strategy on hepatitis B virus infections in China over a 20-year period. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16:e82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tacke F, Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, Heim A, Luedde T, Manns MP, Trautwein C. Acute hepatitis B virus infection by genotype F despite successful vaccination in an immunecompetent German patient. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghendon Y. WHO strategy for the global elimination of new cases of hepatitis B. Vaccine. 1990;8(Suppl):S129–33. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90233-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pande C, Sarin SK, Patra S, Kumar A, Mishra S, Srivastava S, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination with or without hepatitis B immunoglobulin at birth to babies born of HBsAg-positive mothers prevents overt HBV transmission but may not prevent occult HBV infection in babies: randomized controlled trial. J Viral Hepat. 2013;20:801–10. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buchanan C, Tran TT. Management of chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang M-H. Hepatitis B virus infection. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boland GJ, Veldhuijzen IK, Janssen HLA, van der Eijk AA, Wouters MGAJ, Boot HJ. Management and treatment of pregnant women with hepatitis B. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2009;153:A905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan H, Lui H, Chow W. Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in pregnancy. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:370–5. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9063-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hung JH, Chu CJ, Sung PL, Chen CY, Chao KC, Yang MJ, et al. Lamivudine therapy in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B with acute exacerbation during pregnancy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:155–8. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie Y, Li M. Antiviral treatment for pregnant women with chronic HBV infection. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2010;18:486–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bacq Y. Hepatitis B and pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:S12–9. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Zonneveld M, van Nunen AB, Niesters HGM, de Man RA, Schalm SW, Janssen HLA. Lamivudine treatment during pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:294–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chotiyaputta W, Lok AS. Role of antiviral therapy in the prevention of perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:91–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2008.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill JB, Sheffield JS, Kim MJ, Alexander JM, Sercely B, Wendel GD. Risk of hepatitis B transmission in breast-fed infants of chronic hepatitis B carriers. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1049–52. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02000-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson MA, Moore KH, Yuen GJ, Bye A, Pakes GE. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lamivudine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:41–66. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199936010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Rompay KK, Hamilton M, Kearney B, Bischofberger N. Pharmacokinetics of tenofovir in breast milk of lactating rhesus macaques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2093–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.2093-2094.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benaboud S, Pruvost A, Coffie PA, Ekouevi DK, Urien S, Arrive E, et al. Concentrations of tenofovir and emtricitabine in breast milk of HIV-1-infected women in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, in the ANRS 12109 TEmAA Study, Step 2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1315–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00514-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pazmany L, Mandelboim O, Valés-Gómez M, Davis DM, Reyburn HT, Strominger JL. Protection from natural killer cell-mediated lysis by HLA-G expression on target cells. Science. 1996;274:792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jonas M, Block JM, Haber BA, Karpen SJ, London WT, Murray KF. Treatment of children with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Patient selection and therapeutic options. Hepatology. 2010;52:2192–205. doi: 10.1002/hep.23934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angel Garcia AL. Effect of pregnancy on pre-existing liver disease physiological changes during pregnancy. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5:184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tan J, Surti B, Saab S. Pregnancy and cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1081–91. doi: 10.1002/lt.21572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trowsdale J, Betz AG. Mother's little helpers: mechanisms of maternal-fetal tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:241–6. doi: 10.1038/ni1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Druckmann R, Druckmann MA. Progesterone and the immunology of pregnancy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szekeres-Bartho J, Halasz M, Palkovics T. Progesterone in pregnancy; receptor-ligand interaction and signaling pathways. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;83:60–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.06.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raghupathy R. Th1-type immunity is incompatible with successful pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1997;18:478–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Piccinni MP, Scaletti C, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Role of hormone-controlled Th1-and Th2-type cytokines in successful pregnancy. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;109:30–3. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller L, Hunt JS. Sex steroid hormones and macrophage function. Life Sci. 1996:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuckerman SH, Bryan-Poole N, Evans GF, Short L, Glasebrook AL. In vivo modulation of marine serum tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-6 levels during endotoxemia by oestrogen agonists and antagonists. Immunology. 1995:18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fox HS, Bond BL, Parslow TG. Estrogen regulates the IFN-gamma promoter. J Immunol. 1991;146:4362–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maret A, Coudert JD, Garidou L, Foucras G, Gourdy P, Krust A, et al. Estradiol enhances primary antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses and Th1 development in vivo, Essential role of estrogen receptor alpha expression in hematopoietic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:512–21. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.ter Borg MJ, Leemans WF, de Man RA, Janssen HLA. Exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection after delivery. J Vir Hepat. 2008;15:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Y-B, Li X-M, Shi Z-J, Ma L. Pregnant woman with fulminant hepatic failure caused by hepatitis B virus infection: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2305–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i15.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jonas MM. Hepatitis B and pregnancy: An underestimated issue. Liver Intl. 2009;29:133–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tagawa H, Suzuki K, Oh S, Kawano M, Fujita A, Yasuhi Y, et al. Influence of pregnancy on HB virus carriers. Nippon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi. 1987;39:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin HH, Wu WY, Kao JH, Cehn DS. Hepatitis B post-partum e antigen clearance in hepatitis B carrier mothers: correlation with viral characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:605–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trehanpati N, Kotillil S, Hissar SS, Shrivastava S, Khanam A, Sukriti S, et al. Circulating Tregs correlate with viral load reduction in chronic HBV-treated patients with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31:509–20. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang MH, Hsu HY, Hsu HC, Ni YH, Chen JS, Chen DS. The significance of spontaneous hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion in childhood: with special emphasis on the clearance of hepatitis B e antigen before 3 years of age. Hepatology. 1995;22:1387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tse KY, Ho LF, Lao T. The impact of maternal HBsAg carrier status on pregnancy outcomes: a case-control study. J Hepatol. 2005;43:771–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Athanassakis I, Vassiliadis S. Interplay between T helper type 1 and type 2 cytokines and soluble major histocompatibility complex molecules: a paradigm in pregnancy. Immunology. 2002;107:281–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borish LC, Steinke JW. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(Suppl 2):S460–75. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann TR. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mjösberg J, Berg G, Ernerudh J, Ekerfelt C. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in human pregnancy: development of a Treg-MLC-ELISPOT suppression assay and indications of paternal specific Tregs. Immunology. 2007;120:456–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Somerset DA, Zheng Y, Kilby MD, Sansom DM, Drayson MT. Normal human pregnancy is associated with an elevation in the immune suppressive CD25+CD4+ regulatory T-cell subset. Immunology. 2004;112:38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01869.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stoop JN, van der Molen RG, Baan CC, van der Laan LJW, Kuipers EJ, Kusters JG, et al. Regulatory T cells contribute to the impaired immune response in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2005;41:771–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tse KY, Ho LF, Lao T. The impact of maternal HBsAg carrier status on pregnancy outcomes: a case-control study. J Hepatol. 2005;43:771–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.ter Borg MJ, Leemans WF, de Man RA, Janssen HLA. Exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B infection after delivery. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shrivastava S, TrehanPati N, Khanam A, Pande C, Patra S, Trivedi S, et al. Hepatitis B virus mediated down regulated expression of CD3 ζ is associated with phenotypic and functionally defective T cells in HBV infected newborns. Hepatology. 2010;52(Suppl):365A. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mills KH. Regulatory T cells: friend or foe in immunity to infection? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:841–55. doi: 10.1038/nri1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Billingham RE, Brent L, Medawar PB. Actively acquired tolerance of foreign cells. Nature. 1953;172:603–6. doi: 10.1038/172603a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells inimmunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gammon G, Dunn K, Shastri N, Oki A, Wilbur S, Sercarz EE. Neonatal T-cell tolerance to minimal immunogenic peptides is caused by clonal inactivation. Nature. 1986;319:413–5. doi: 10.1038/319413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schmielau J, Nalesnik MA, Finn OJ. Suppressed T-cell receptor ζ chain expression and cytokine production in pancreatic cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:933S–9S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schule J, Bergkvist L, Hakansson L, Gustafsson B, Hakansson A. Down-regulation of the CD3ζ chain in sentinel node biopsies from breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:33–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1016009913699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borish LC, Steinke JW. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:460–75. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Strieter RM, Standiford TJ, Huffnagle GB, Colletti LM, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL, et al. The good, the bad, and the ugly. “The role of chemokines in models of human disease. J Immunol. 1996;156:3583–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Johnston RB. Function and cell biology of neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes in the newborn infant. Vaccine. 1998;16:1363–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schelonka R, L, Infante AJ. 1998. Neonatal immunology. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22:2–14. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(98)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Siegrist CA. Neonatal and early life vaccinology. Vaccine. 2011;19:3331–46. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moir S, Ho J, Malaspina A, Wang W, Di Poto AC, O’Shea MA, et al. Evidence for HIV-associated B cell exhaustion in a dysfunctional memory B cell compartment in HIV-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1797–805. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moir S, Fauci AS. B cells in HIV infection and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:235–45. doi: 10.1038/nri2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shrivastava S, Trehanpati N, Kottilil S, Sarin SK. Decline in immature transitional B cells after hepatitis B vaccination in hepatitis B positive newborns. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:792–4. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828df344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]