Abstract

Purpose.

To test whether a diet supplemented with coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) ameliorates glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress–mediated retinal ganglion cell (RGC) degeneration by preventing mitochondrial alterations in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice.

Methods.

Preglaucomatous DBA/2J and age-matched control DBA/2J-Gpnmb+ mice were fed with CoQ10 (1%) or a control diet daily for 6 months. The RGC survival and axon preservation were measured by Brn3a and neurofilament immunohistochemistry and by conventional transmission electron microscopy. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), superoxide dismutase-2 (SOD2), heme oxygenase-1 (HO1), N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NR) 1 and 2A, and Bax and phosphorylated Bad (pBad) protein expression was measured by Western blot analysis. Apoptotic cell death was assessed by TUNEL staining. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) content and mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam)/oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complex IV protein expression were measured by real-time PCR and Western blot analysis.

Results.

Coenzyme Q10 promoted RGC survival by approximately 29% and preserved the axons in the optic nerve head (ONH), as well as inhibited astroglial activation by decreasing GFAP expression in the retina and ONH of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Intriguingly, CoQ10 significantly blocked the upregulation of NR1 and NR2A, as well as of SOD2 and HO1 protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In addition, CoQ10 significantly prevented apoptotic cell death by decreasing Bax protein expression or by increasing pBad protein expression. More importantly, CoQ10 preserved mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice.

Conclusions.

Our findings suggest that CoQ10 may be a promising therapeutic strategy for ameliorating glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Keywords: coenzyme Q10, excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, mitochondrial alteration, glaucoma

Coenzyme Q10 may be a promising therapeutic strategy for ameliorating glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness and affects 70 million people worldwide.1,2 Although elevated IOP is an important risk factor for optic nerve (ON) degeneration and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) death in glaucoma, lowering IOP is not always effective for preserving visual function in patients.1,2 Glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress have been implicated as important pathophysiological mechanisms in mitochondrial dysfunction–mediated glaucomatous neurodegeneration.3–10 Increasing evidence indicates that glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress are associated with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) alteration or DNA oxidation–related mitochondrial dysfunction in retinal neurodegeneration, including glaucoma.4,8,11–13

Mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam, also as known as mtTFA), a nucleus-encoded DNA-binding protein in mitochondria, has an important role in mitochondrial gene expression and mtDNA maintenance and therefore is essential for oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)–mediated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis.8,14–17 Mice lacking Tfam have impairment of mtDNA transcription and loss of mtDNA, leading to bioenergetics dysfunction and embryonic lethality.14 In contrast, overexpression of Tfam mediates delayed neuronal death following transient forebrain ischemia in mice.18–20 Importantly, emerging evidence indicates that acute IOP elevation significantly increased Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the early neurodegeneration of ischemic rat retina, suggesting that these responses may support endogenous repair mechanisms for elevated IOP–induced mtDNA alteration.8

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), an essential cofactor of the electron transport chain, acts by maintaining the mitochondrial membrane potential, supporting ATP synthesis and inhibiting reactive oxygen species generation for protecting neuronal cells against oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases.21–25 Previous studies demonstrated that CoQ10 protected retinal neurons against kainate-induced apoptotic injury26 and against hydrogen peroxide–induced oxidative stress in vitro and N-methyl-d-aspartate–induced glutamate excitotoxicity in vivo.27 Moreover, CoQ10 prevented retinal damage caused by acute high IOP–induced transient ischemic injury.28,29 Of interest, the level of CoQ10 in the human retina can decline by approximately 40% with age,30 suggesting the possibility that this decline in CoQ10 may be associated with age-related glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Herein, we tested whether a diet supplemented with CoQ10 ameliorates glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress–mediated RGC and axon degeneration in a mouse model of glaucoma. We also assessed whether CoQ10 prevents mitochondrial alteration by preserving mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retina of the mouse model.

Methods

Animals

Adult 4-month-old female DBA/2J and DBA/2J-Gpnmb+ (D2-Gpnmb+) mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME)31 were housed in covered cages, fed with CoQ10 or a control diet daily for 6 months as reported below, and kept on a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle. All procedures described were performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Diego.

CoQ10 Treatment

Coenzyme Q10 was purchased from Kaneka Nutrients (Pasadena, TX). An AIN-93G purified control diet and a diet supplemented with CoQ10 were formulated by Harlan Laboratories (Madison, WI). The following four groups of mice were studied: D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (n = 25), DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet (n = 70), D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the 1% CoQ10 diet (vol/vol) (which equals a daily dose of 1600–2000 mg/kg body weight in mice weighing 25–30 g) (n = 25), and DBA/2J mice treated with the 1% CoQ10 diet (n = 80).32 To examine a daily dose for CoQ10, the amount of food taken by the mice was measured by weighing pelleted mouse chow that has 1% CoQ10, and then the actual dose of CoQ10 that the mouse received was calculated.

IOP Measurement

The IOP elevation onset typically occurs between age 5 and 7 months, and IOP-linked ON axon loss is well advanced by age 10 months.31,33,34 The DBA/2J and nonglaucomatous D2-Gpnmb+ mice used in this study had a single IOP measurement at age 10 months (to confirm the development of spontaneous IOP elevation > 20 mm Hg). The IOP measurement was performed as described previously.33–35 Briefly, after anesthesia with a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg, Ketaset; Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and xylazine (9 mg/kg, TranquiVed; Vedeco, Inc., St. Joseph, MO), a sterilized and water-filled microneedle with an external diameter of 50 to 70 μm was used to cannulate the anterior chamber. The microneedle was then repositioned to minimize corneal deformation and to ensure that the eye remained in its normal position. The microneedle was connected to a pressure transducer (Blood Pressure Transducer; WPI, Sarasota, FL), which relayed its signal to a bridge amplifier (Quad Bridge; ADInstruments, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia). The amplifier was connected to an analog to digital converter (Power Laboratory; ADInstruments) and a computer (G4 Macintosh; Apple Computer, Inc., Cupertino, CA).

Tissue Preparation

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg, Ketaset; Fort Dodge Animal Health) and xylazine (9 mg/kg, TranquiVed; Vedeco, Inc.) before cervical dislocation. For immunohistochemistry, the retinas were dissected from the choroids and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 2 hours at 4°C. After several washes in PBS, the retinas and ON heads (ONHs) were dehydrated through graded ethanols and embedded in polyester wax as previously described.34

Whole-Mount Immunohistochemical Analysis

Retinas from enucleated eyes were dissected as flattened whole mounts in 10-month-old glaucomatous DBA/2J and age-matched nonglaucomatous D2-Gpnmb+ mice. The retinas were immersed in PBS containing 30% sucrose for 24 hours at 4°C. The retinas were blocked in PBS containing 3% donkey serum, 1% BSA, 1% fish gelatin,36,37 and 0.1% Triton X-100 and then incubated with goat polyclonal anti-Brn3a antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), a specific maker for RGCs,38 and guinea pig polyclonal anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (1:500; Advanced ImmunoChemical, Inc., Long Beach, CA) for 3 days at 4°C. After several wash steps with PBS, the retinas were incubated with the secondary antibodies AlexaFluor 568 donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:100; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or Cy5-conjugated anti–guinea pig IgG antibody (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA) for 24 hours and subsequently washed with PBS. The retinas were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen) in PBS. Images were captured with a spinning disk confocal microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, PA) equipped with a high-precision closed-loop XY stage and closed-loop Z control with commercial mosaic acquisition software (MicroBrightField; MBF Bioscience, Inc., Williston, VT).

Quantitative Analysis for RGC Counting

To count RGCs labeled with Brn3a, each retinal quadrant was divided into three zones by the central, middle, and peripheral retina (one-sixth, three-sixths, and five-sixths of the retinal radius, respectively). The RGC densities were measured in 24 distinct areas (two areas at the central, middle, and peripheral per retinal quadrant) per condition by two investigators (HK and SYK) in a masked fashion, and the scores were averaged (n = 10 retinal flat mounts per group).

Western Blot Analysis

The retinas were immediately homogenized with mortar homogenizer in ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination lysis buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 50 mM Tris-cl [pH 7.6]) containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Ten micrograms of pooled retinal protein from each group (n = 4 retinas per group) was separated by SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membrane was blocked with PBS–0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature and subsequently incubated with the primary antibodies for 16 hours at 4°C. The primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP antibody (1:3000; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO), rabbit polyclonal anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NR) 1 antibody (1:1000; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-NR2A antibody (1:500; Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti–superoxide dismutase-2 (SOD2) antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti–heme oxygenase-1 (HO1) antibody (1:1000; Millipore), mouse monoclonal anti-actin antibody (1:5000; Millipore), rabbit polyclonal anti-Tfam antibody (1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti–total OXPHOS complex antibody (1:3000; Invitrogen), rabbit polyclonal anti-Porin antibody (1:1000; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax antibody (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and rabbit polyclonal anti–phosphorylated Bad (pBad) antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). After several washes in PBST, the membranes were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5000; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5000; Bio-Rad), or donkey anti-goat IgG (1:5000; Bio-Rad) and developed by film using chemiluminescence detection (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ). The scanned film images were analyzed by ImageJ (in the public domain at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and the band intensities were normalized to the band intensity for actin.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed with 7-μm wax sections of ONHs as previously described.34 To prevent nonspecific background, the sections were incubated in 1% BSA–PBS for 1 hour at room temperature before incubation with the primary antibodies for 16 hours at 4°C. The primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti–neurofilament 68 (clone NR4, 1:500; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) and guinea pig polyclonal anti-GFAP antibody (1:500; Advanced ImmunoChemical, Inc.). After several wash steps, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibodies AlexaFluor 488 dye–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100; Invitrogen) and Cy5-conjugated anti–guinea pig IgG antibody (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.) for 2 hours at 4°C and were subsequently washed with PBS. The sections were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL; Invitrogen) in PBS. Images were acquired with confocal microscopy (Olympus FluoView1000; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Electron Microscopy

For conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM), two eyes from each group were fixed via cardiac perfusion with solution at 37°C in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.) and placed in precooled fixative on ice for 1 hour. The ONs were dissected with 0.15 M sodium cacodylate plus 3 mM calcium chloride (pH 7.4) on ice and postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide, 0.8% potassium ferrocyanide, and 3 mM calcium chloride in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4) for 1 hour, and they were then washed with ice-cold distilled water, poststained with 2% uranyl acetate at 4°C, dehydrated using graded ethanols, and embedded in Durcupan resin (Fluka, St. Louis, MO). Ultrathin (70 nm) sections were poststained with uranyl acetate and lead salts and evaluated with a JEOL 1200FX transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc., Peabody, MA) operated at 80 kV. Images were recorded on film at ×8000 magnification. The negatives were digitized at 1800 dots per inch using a Nikon Cool scan system (Nikon, Melville, NY), giving an image size of 4033 × 6010–pixel array and a pixel resolution of 1.77 nm. For quantitative analysis, the number of axons was normalized to the total area occupied by axons in each image, which was measured using ImageJ (in the public domain at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Measurement of mtDNA Content

The mtDNA content of each sample was determined as described previously.39 Briefly, total genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from retinas using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as described in the manufacturer's protocol. For the measurement of relative mtDNA content, real-time PCR was carried out using an MX3000P real-time PCR system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Total gDNA (10 ng) from each sample was amplified using iQTM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and mitochondrial cytochrome B (CytB-F: 5′-GGTCTTTTCTTAGCCATACACTACA-3′; CytB-R: 5′-ATATCGGATTAGTCACCCGTAAT-3′) or β-actin (ActB-F: GATCGATGCCGGTGCTAAGA-3′; ActB-R: 5′-CACCATCACACCCTGTGGAAG-3′) primers for 40 cycles (initial incubation at 95°C for 10 minutes) and an additional 40 cycles (95°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds). Output data were obtained as Ct values, and the difference in mtDNA content among samples was calculated using the comparative Ct method.40 The ActB gene was used to normalize the ratio between mtDNA and gDNA. The samples were run in triplicate for all experiments.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means (SDs). Comparison of two or three experimental conditions was evaluated using the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

CoQ10 Promotes RGC Survival in Glaucomatous DBA/2J Mice

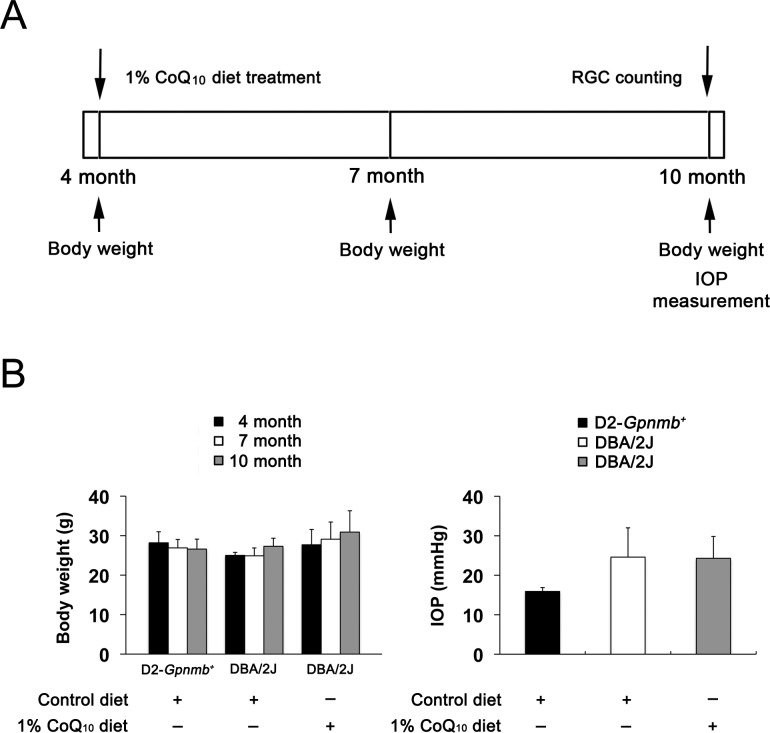

Preglaucomatous DBA/2J and age-matched nonglaucomatous control D2-Gpnmb+ mice at age 4 months were fed with either an unsupplemented control diet or a CoQ10 (1%) diet daily for 6 months. We found that the daily dose for CoQ10 per mouse was 33 (2) mg. To determine whether CoQ10 induces changes in the body weight and IOP, we measured the body weight at age 4, 7, and 10 months and the IOP at age 10 months (Fig. 1A). There was no significant change in the body weight between control and CoQ10-treated DBA/2J mice (Fig. 1B). Consistent with our previous study,34 the IOP peak was 23.1 (5.7) mm Hg among 10-month-old glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. However, there was no significant change in the IOP between control and CoQ10-treated DBA/2J mice (Fig. 1B), indicating that the CoQ10 diet did not change the IOP in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In addition, the mean IOP was 14.7 (5.7) mm Hg in 10-month-old D2-Gpnmb+ mice (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Coenzyme Q10 supplementation and IOP measurement in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. (A) Diagram for CoQ10 (1%) supplementation and IOP measurement. Preglaucomatous DBA/2J and age-matched control D2-Gpnmb+ mice at age 4 months were fed with either an unsupplemented control diet or the 1% CoQ10 diet daily for 6 months. (B) There was no significant change in the body weight among groups. The IOP peak was 23.1 (5.7) mm Hg among 10-month-old glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, and there was no significant change in IOP between control and 1% CoQ10–treated glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (n = 70). In addition, the mean IOP was 14.7 (5.7) mm Hg in 10-month-old D2-Gpnmb+ mice (n = 25).

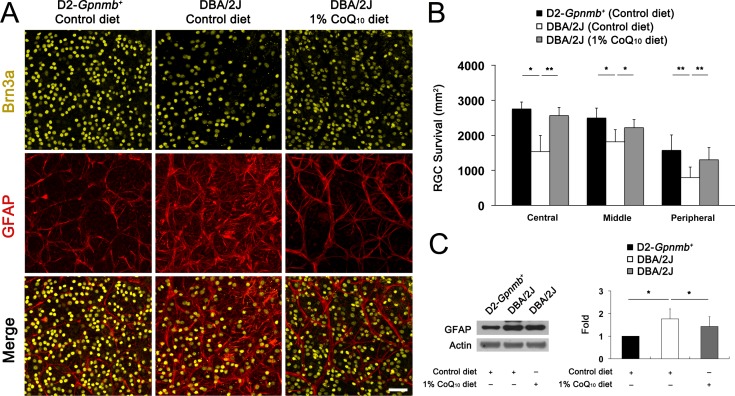

Because CoQ10 protects RGCs against high IOP–induced transient ischemic injury28 and other apoptotic insults,26,41 we determined RGC survival following CoQ10 supplementation in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice by whole-mount immunohistochemistry using antibody raised against Brn3a. There was no significant change in RGC survival between control and CoQ10-treated 10-month-old D2-Gpnmb+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S1, Supplementary Table S1). The mean RGC density per retina for each group is summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The retinas from 10-month-old D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet had a mean of 2754 (196) RGCs in the central area, 2495 (283) RGCs in the middle area, and 1570 (442) RGCs in the peripheral area (n = 10 retinas) (Figs. 2A, 2B; Supplementary Table S1). Compared with D2-Gpnmb+ retinas treated with the control diet, glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed approximately 31% of RGC loss in the retinas (P < 0.05) (Figs. 2A, 2B; Supplementary Table S1). In contrast, CoQ10 significantly promoted RGC survival by approximately 29% in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Figs. 2A, 2B; Supplementary Table S1). In addition, RGC loss was accompanied by activation of astroglia as indicated by significantly increased GFAP expression by 1.76 (0.44)–fold in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Figs. 2A, 2C). However, CoQ10 significantly decreased GFAP expression by 1.42 (0.43)–fold in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Figs. 2A, 2C).

Figure 2.

The RGC survival in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet. (A) Retinal whole-mount immunohistochemistry using antibodies raised against Brn3a and GFAP. High magnification showed representative images from the middle area of retinas. Compared with the retinas in D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet, the retinas in glaucomatous DBA/2J treated with the control diet showed greater RGC loss and astroglial activation. However, the CoQ10 diet significantly promoted RGC survival and blocked astroglial activation in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of RGC survival. (C) Glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet significantly increased GFAP protein expression compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice. In contrast, the CoQ10 diet significantly decreased GFAP protein expression in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Values are means (SDs) (n = 10 retinas per group for RGC counting; n = 4 retinas per group for Western blot). *Significant at P < 0.05 compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. **Significant at P < 0.05 compared with glaucomatous DBA/2J treated with the control diet.

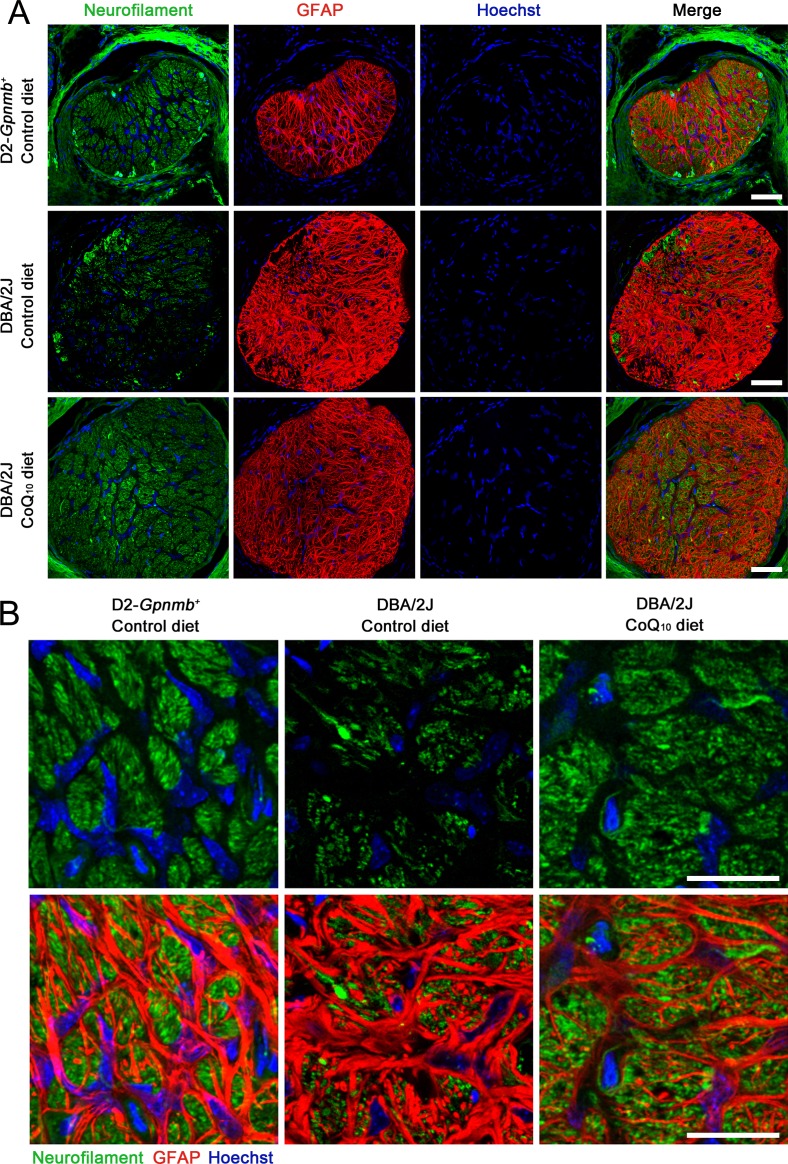

CoQ10 Partially Preserves RGC Axons in the Glial Lamina of the ONH in Glaucomatous DBA/2J Mice

To determine whether CoQ10 preserves RGC axons in the glial lamina of the ONH in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, we performed immunohistochemistry using antibodies raised against neurofilament, a marker for axons, and GFAP. The ONHs in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed greater loss of axons in the glial lamina by decreasing neurofilament immunoreactivity compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. However, the CoQ10 diet partially restored neurofilament immunoreactivity in the glial lamina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (Figs. 3A, 3B). In addition, the ONHs in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed activation of astroglia in the glial lamina by increasing GFAP immunoreactivity and hypertrophic cell bodies compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. However, the CoQ10 diet partially restored GFAP immunoreactivity in the glial lamina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (Figs. 3A, 3B).

Figure 3.

The preservation of RGC axons in the glial lamina of the ONH in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet. (A, B) Neurofilament and GFAP double immunohistochemistry. (A) The ONH of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed greater loss of axons in the glial lamina by decreasing neurofilament immunoreactivity compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice. However, the CoQ10 diet partially restored neurofilament immunoreactivity in the glial lamina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In addition, glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed activation of astroglia in the glial lamina by increasing GFAP immunoreactivity and hypertrophic cell bodies compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice. However, the CoQ10 diet partially restored GFAP immunoreactivity in the glial lamina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. (B) High magnification from (A). Scale bars: 20 μm.

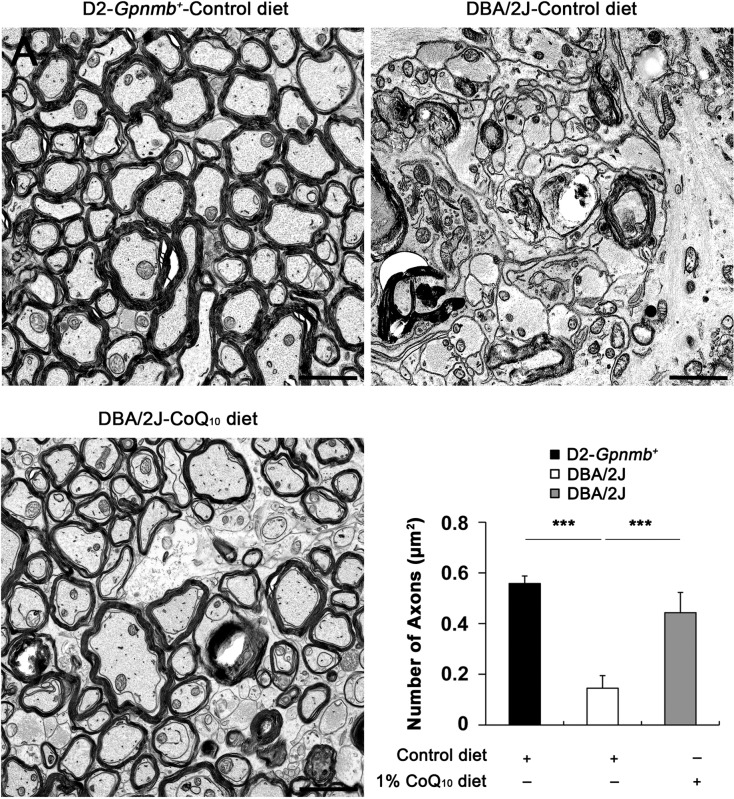

Based on our in vivo results of axon preservation in the glial lamina, we sought to determine whether CoQ10 preserves axonal integrity in the ON posterior to the myelination transition zone in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice by counting ON axons using conventional TEM analysis. The D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet showed normal healthy morphology of myelinated axons in the ON (Fig. 4). In contrast, glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet showed an absence of axons and the accumulation and disorganization of myelination in the ON. In addition, we found that abundant hypertrophic astrocyte processes were filled in the area of axon loss (Fig. 4). Of interest, CoQ10 treatment showed the preservation of axons and their myelination in the ON of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (Fig. 4). In good agreement with these results, quantitative analyses showed that the number of axons, normalized to the total area in each image, was significantly decreased approximately 62% in the ON of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with the ON of D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (0.15 [0.05] vs. 0.56 [0.03] μm2, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). A previous study42 reported that glaucomatous DBA/2J mice showed greater than 50% loss of myelinated axons compared with young mice and old low-IOP mice. Although there was a difference in the axon density between these findings, it is possible that this difference might have resulted from the use of a counting method that only measured the healthy axons with intact myelination by electron microscopy analysis or from the great variability in the DBA model. Finally and most importantly, CoQ10 significantly increased the number of axons and preserved myelination in the ON in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (0.44 [0.08] μm2, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The preservation of RGC axon integrity in the ON of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet as shown by conventional TEM analysis. The control diet–treated D2-Gpnmb+ mice showed normal healthy morphology of myelinated axons in the ON. In contrast, the control diet–treated glaucomatous DBA/2J mice showed an absence of axons and the accumulation and disorganization of myelination in the ON. Note that abundant hypertrophic astrocyte processes were filled in the area of axon loss. However, CoQ10 diet–treated glaucomatous DBA/2J mice showed partial preservation of axons and myelination in the ON. Quantitative analyses showed that the number of axons, normalized to the total area in each image, was significantly decreased in the ON of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet (n = 10 images) compared with the ON of D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (n = 6 images). In contrast, CoQ10 significantly increased the number of axons in the ON of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (n = 12 images). ***Significant at P < 0.001 compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet or glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet. Scale bars: 2 μm.

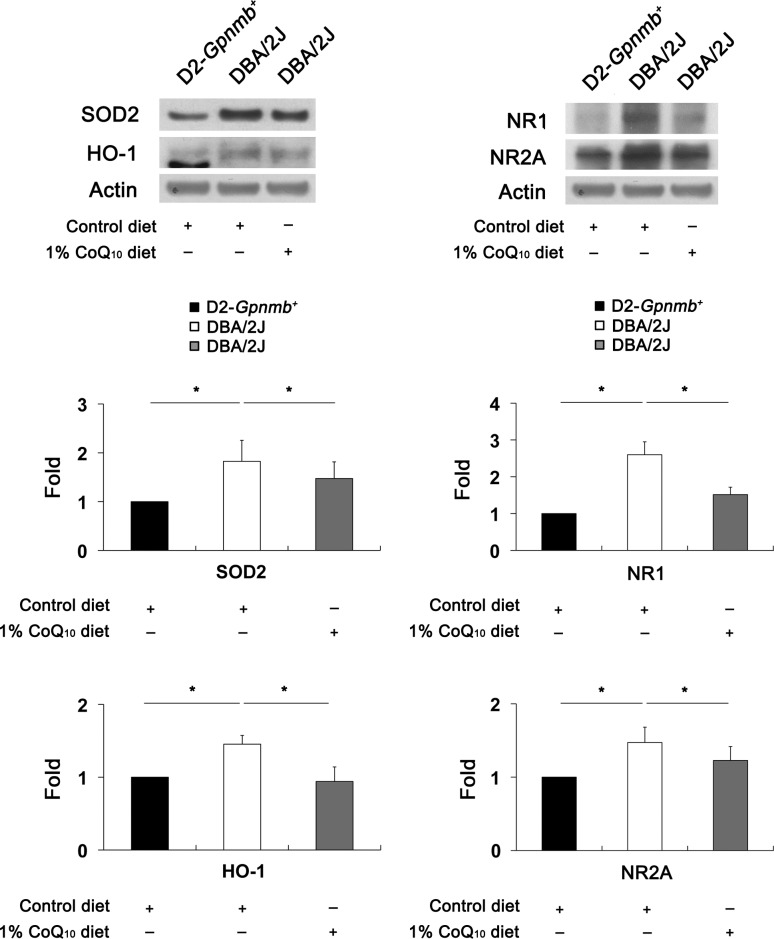

CoQ10 Ameliorates Glutamate Excitotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Glaucomatous Retina

Previous studies6,43 reported that the uncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine promoted RGC survival and that the antioxidant α-luminol reduced oxidative stress in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In addition, CoQ10 protects retinal cells or NT2/D1 neuronal precursor cells against glutamate excitotoxicity or oxidative stress.27,44 To determine whether CoQ10 influences NRs and oxidative stress in the retinas of 10-month-old glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, relative changes in NR1, NR2A, SOD2, and HO1 protein expression were measured by Western blot analysis.

Compared with the retinas of D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet, NR1 and NR2A protein expression was significantly increased by 2.59 (0.21)–fold and 1.47 (0.12)–fold, respectively, in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5). However, CoQ10 significantly decreased NR1 and NR2A protein expression by 1.51 (0.14)–fold and 1.22 (0.11)–fold in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5), respectively. Compared with the retinas of D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet, SOD2 and HO1 protein expression was significantly increased by 1.82 (0.43)–fold and 1.45 (0.12)–fold in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5), respectively. However, CoQ10 significantly decreased SOD2 and HO1 protein expression by 1.47 (0.34)–fold and 0.94 (0.20) fold in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5), respectively.

Figure 5.

The blockade of oxidative stress and glutamate excitotoxicity in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet. The retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet significantly increased SOD2, HO1, NR1, and NR2A protein expression compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. In contrast, the CoQ10 diet significantly decreased SOD2, HO1, NR1, and NR2A protein expression in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Values are means (SDs) (n = 4 retinas per group). *Significant at P < 0.05 compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet or glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet.

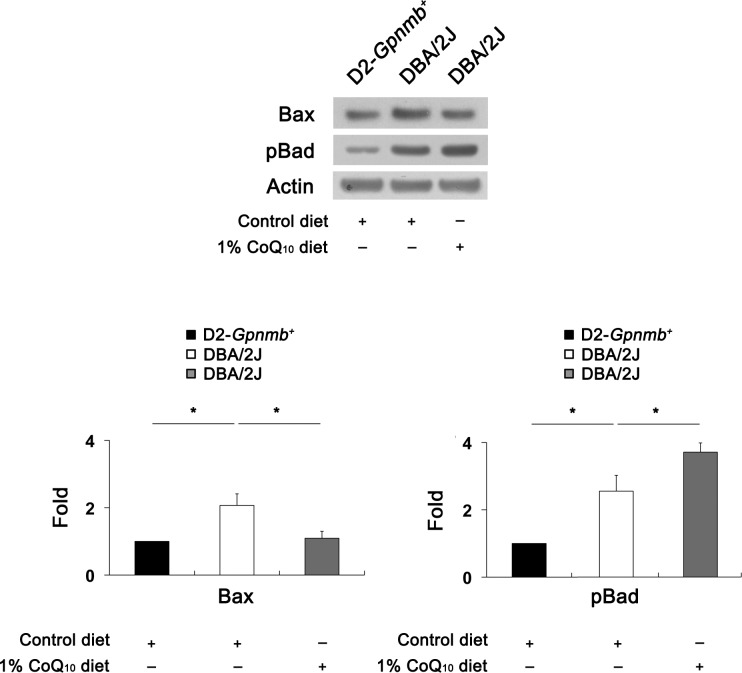

CoQ10 Decreases Bax but Increases pBad Expression in Glaucomatous Retina

To determine whether CoQ10 modulates the apoptotic cell death pathway in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, we performed Western blot analysis using antibodies raised against Bax and pBad. Bax protein expression was significantly increased by 2.08 (0.27)–fold in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Compared with glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet, CoQ10 significantly decreased Bax protein expression by 1.15 (0.09)–fold in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). In addition, pBad protein expression significantly increased by 2.51 (0.34)–fold in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Compared with glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet, CoQ10 significantly increased Bax protein expression by 3.67 (0.21)–fold in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The blockade of the apoptotic pathway in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet. The retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet significantly increased Bax and pBad protein expression compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. However, the CoQ10 diet significantly decreased Bax protein expression but showed a greater level of pBad protein expression in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Values are means (SDs) (n = 4 retina per group). *Significant at P < 0.05 compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet or glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet.

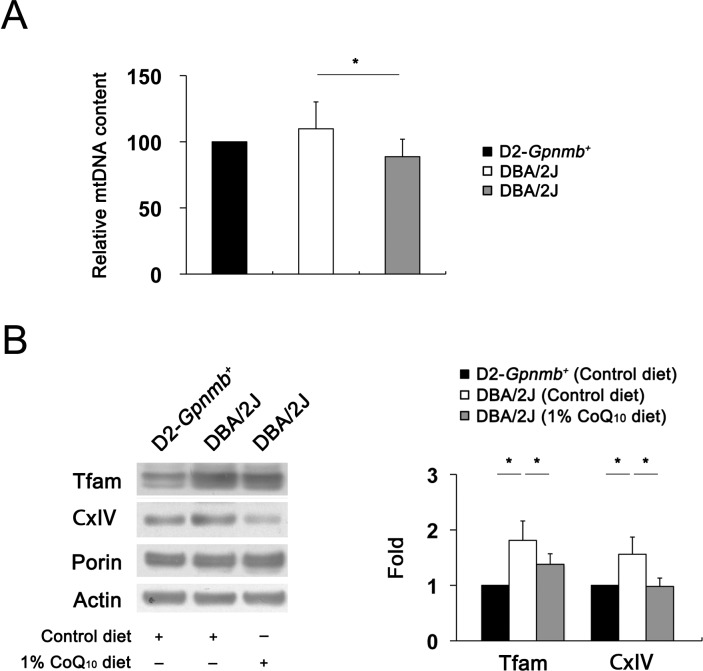

CoQ10 Preserves mtDNA Content and Tfam/OXPHOS Complex IV Protein Expression in Glaucomatous Retina

Although mtDNA is particularly susceptible to glutamate excitotoxicity–induced oxidative stress,45 it is unknown whether glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress are associated with mtDNA alteration in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. To determine whether glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by IOP elevation alter mtDNA content and whether CoQ10 preserves this alteration in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, the relative mtDNA content was measured by real-time PCR. The relative mtDNA content was slightly increased by 110% (20%), but there was no statistical significance in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (Fig. 7A). However, CoQ10 significantly decreased mtDNA content by 88% (13%) in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A). To further determine whether glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by IOP elevation alter Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression and whether CoQ10 preserves this alteration in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, we performed Western blot analysis using antibodies raised against Tfam and OXPHOS complex protein. The Tfam and OXPHOS complex IV protein expression was significantly increased by 1.82 (0.35)–fold and 1.56 (0.31)–fold, respectively, in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B). Compared with glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet, CoQ10 significantly decreased Tfam and OXPHOS complex IV protein expression by 1.38 (0.19)–fold and 0.98 (0.15)–fold, respectively, in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The preservation of mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the CoQ10 diet. (A) Quantitative analysis of mtDNA content. The retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet slightly increased mtDNA content compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. However, the CoQ10 diet significantly decreased mtDNA content in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. (B) Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein Western blot analysis. The retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet significantly increased Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet. However, the CoQ10 diet significantly decreased Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Values are means (SDs) (n = 4 retinas per group). *Significant at P < 0.05 compared with D2-Gpnmb+ mice treated with the control diet or glaucomatous DBA/2J mice treated with the control diet.

Discussion

Coenzyme Q10 is a potent antioxidant and neurotherapeutic agent against oxidative stress in many neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson and Huntington diseases.23,32,46–48 Of note, it has been reported that the level of CoQ10 in the human retina declines with age,30 raising the possibility that the decline in CoQ10 level with aging may lead to increased vulnerability of RGCs in glaucomatous neurodegeneration due to a link between older age and the prevalence of glaucoma.11 Moreover, growing evidence indicates that CoQ10 is neuroprotective in retinal cells against pressure in vivo and in vitro, as well as against oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and apoptotic radiation.27,28,41,49 The dose of CoQ10 supplementation correlates well with the plasma CoQ10 level: when administered in large doses, CoQ10 was taken up by all tissues, including heart and brain mitochondria.50 These findings suggest that CoQ10 could also be taken up by the retina and lead to a beneficial effect in glaucomatous retina. Nevertheless, the effect of CoQ10 and its protective mechanisms in glaucomatous neurodegeneration remain unknown.

In the present study, we found that a diet supplementation with CoQ10 for 6 months significantly promoted RGC survival in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. In addition, CoQ10 not only preserved RGC axons in the ON but also blocked astroglial activation in the ONH of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. These results indicate that CoQ10 can ameliorate RGC survival and axon degeneration during glaucomatous neurodegeneration. Because astroglia or Müller cell activation coincides with RGC degeneration in the hypertensive retina of human, rat, and mouse8,51–54 and with the glaucomatous retina or ONH of human, rat, and mouse,55–57 our findings showing CoQ10-mediated inhibition of astroglial activation in the retina and ONH may reflect the possibility that CoQ10-mediated blockade of oxidative stress may indirectly reduce astroglial activation in the retina or ONH against elevated IOP–induced glaucomatous damage as a result of increased RGC survival. Regardless, it cannot be ruled out that CoQ10 may also prevent glial activation by directly blocking oxidative stress in astroglia or Müller cells in glaucomatous retina and ONH. Future studies will be needed to determine whether CoQ10 is also neuroprotective in glial cells in the retina or ONH against oxidative stress because oxidative stress has remarkably been linked to glial cell activation or reaction in the retina and ON.8,57–61

Glutamate excitotoxicity–mediated oxidative stress is considered one of the major causal factors for neuronal cell death in many neurodegenerative diseases, including glaucoma.6–8,29,62–64 Emerging evidence indicates that glutamate excitotoxicity–mediated oxidative stress has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction in retinal injury.7,8 In the present study, our findings demonstrated the first evidence to date that CoQ10 significantly blocks the upregulation of NR1, NR2A, SOD2, and HO1 protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, raising the possibility not only that glutamate excitotoxicity triggers oxidative stress but also that excessive oxidative stress may, in turn, lead to increased vulnerability of the retina by involving the upregulation of NRs in glaucomatous neurodegeneration. Therefore, we suggest that CoQ10 has therapeutic potential for ameliorating glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress–mediated glaucomatous neurodegeneration in the retina.

Consistent with our finding that CoQ10 promoted RGC survival in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice, we observed that CoQ10 significantly decreased Bax protein expression but increased pBad protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Bax is a proapoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family that is essential in many pathways of apoptosis65,66 and directly interacts with the component forming the mitochondrial permeability transition pore allowing proteins to escape from the mitochondria into the cytosol to initiate apoptosis.67–69 Bax is counteracted by Bcl-xL, which forms heterodimers with dephosphorylation of Bad, which inactivates Bcl-xL, and pBad eliminates this dimerization, which activates Bcl-xL.70,71 Collectively, our results suggest that CoQ10 may promote RGC survival against the mitochondria-related apoptotic pathway in glaucomatous neurodegeneration by decreasing Bax protein expression and by increasing pBad protein expression. These results suggest that increased pBad expression may represent an endogenous repair mechanism against the apoptotic pathway and that CoQ10 may contribute to the blockade of a Bax-mediated increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability or the promotion of mitochondrial homeostasis in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Alterations of mtDNA or OXPHOS induced by glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress have been implicated in the pathogenesis of glaucoma.9,11,72–77 Tfam regulates mtDNA copy numbers in mammals, and the levels of Tfam correlate with the levels of mtDNA.15,78 Recent evidence suggests that Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein is rapidly increased in the early neurodegenerative events of ischemic retinal injury or neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, indicating that Tfam may contribute to an endogenous repair mechanism of injured retinal or brain neurons.8,79 Furthermore, recent studies18,19 reported that overexpression of Tfam protects mitochondria against β-amyloid–induced oxidative damage in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells and ameliorates delayed neuronal cell death in the hippocampus following transient forebrain ischemia in mice. On the other hand, impaired mtDNA transcription and mtDNA loss are triggered in mice lacking Tfam, leading to mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction–mediated embryonic lethality.14 However, it is unknown whether glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by IOP elevation alter Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retina or whether CoQ10 blocks this alteration of Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression against glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

We found that elevated IOP significantly triggered an increase in Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. However, CoQ10 preserved mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in the retina of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Consistent with these results, our previous findings demonstrated that acute IOP elevation triggered glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress, as well as the upregulation of Tfam protein expression in early retinal neurodegeneration.8 Collectively, these results suggest that increasing Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression may be an important mtDNA-related endogenous compensatory mechanism in mitochondria against glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration. Furthermore, CoQ10-mediated preservation of mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression may provide a potential mechanism for protecting RGCs against glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress–mediated mitochondrial alteration in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

In conclusion, these results provide the first direct evidence to date that CoQ10 promotes RGC survival by inhibiting oxidative stress, glutamate excitotoxicity, and activation of the Bax and Bad–mediated apoptotic pathway and by preserving mtDNA content and Tfam/OXPHOS complex IV protein expression in glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Based on these observations, our findings suggest that CoQ10 may be a promising therapeutic strategy for ameliorating glutamate excitotoxicity and oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Grants EY018658 (W-KJ) and P30EY022589 (Vision Research Core Grant) from the National Institutes of Health, an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY), and the international collaborative research funds of Chonbuk National University in 2010 (DL).

Disclosure: D. Lee, None; M.S. Shim, None; K.-Y. Kim, None; Y.H. Noh, None; H. Kim, None; S.Y. Kim, None; R.N. Weinreb, None; W.-K. Ju, None

References

- 1. Weinreb RN, Khaw PT. Primary open-angle glaucoma. Lancet. 2004; 363: 1711–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang K, Zhang L, Weinreb RN. Ophthalmic drug discovery: novel targets and mechanisms for retinal diseases and glaucoma. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012; 11: 541–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tezel G. Oxidative stress in glaucomatous neurodegeneration: mechanisms and consequences. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006; 25: 490–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jarrett SG, Lin H, Godley BF, Boulton ME. Mitochondrial DNA damage and its potential role in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008; 27: 596–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Osborne NN. Pathogenesis of ganglion “cell death” in glaucoma and neuroprotection: focus on ganglion cell axonal mitochondria. Prog Brain Res. 2008; 173: 339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ju WK, Kim KY, Angert M, et al. Memantine blocks mitochondrial OPA1 and cytochrome c release and subsequent apoptotic cell death in glaucomatous retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 707–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nguyen D, Alavi MV, Kim KY, et al. A new vicious cycle involving glutamate excitotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dynamics. Cell Death Dis. 2011; 2: e240 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3252734/. Accessed January 22, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee D, Kim KY, Noh YH, et al. Brimonidine blocks glutamate excitotoxicity–induced oxidative stress and preserves mitochondrial transcription factor A in ischemic retinal injury. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e47098 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3467218/. Accessed January 22, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chrysostomou V, Rezania F, Trounce IA, Crowston JG. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in glaucoma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013; 13: 12–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Osborne NN, Del Olmo-Aguado S. Maintenance of retinal ganglion cell mitochondrial functions as a neuroprotective strategy in glaucoma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013; 13: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee S, Sheck L, Crowston JG, et al. Impaired complex-I–linked respiration and ATP synthesis in primary open-angle glaucoma patient lymphoblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 2431–2437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santos JM, Kowluru RA. Role of mitochondria biogenesis in the metabolic memory associated with the continued progression of diabetic retinopathy and its regulation by lipoic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 8791–8798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Inman DM, Lambert WS, Calkins DJ, Horner PJ. α-Lipoic acid antioxidant treatment limits glaucoma-related retinal ganglion cell death and dysfunction. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e65389 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3673940/. Accessed January 22, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Larsson NG, Wang J, Wilhelmsson H, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat Genet. 1998; 18: 231–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ngo HB, Kaiser JT, Chan DC. The mitochondrial transcription and packaging factor Tfam imposes a U-turn on mitochondrial DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011; 18: 1290–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bonawitz ND, Clayton DA, Shadel GS. Initiation and beyond: multiple functions of the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Mol Cell. 2006; 24: 813–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Falkenberg M, Larsson NG, Gustafsson CM. DNA replication and transcription in mammalian mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007; 76: 679–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu S, Zhong M, Zhang L, et al. Overexpression of Tfam protects mitochondria against β-amyloid–induced oxidative damage in SH-SY5Y cells. FEBS J. 2009; 276: 3800–3809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hokari M, Kuroda S, Kinugawa S, Ide T, Tsutsui H, Iwasaki Y. Overexpression of mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) ameliorates delayed neuronal death due to transient forebrain ischemia in mice. Neuropathology. 2010; 30: 401–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piao Y, Kim HG, Oh MS, Pak YK. Overexpression of TFAM, NRF-1 and myr-AKT protects the MPP+-induced mitochondrial dysfunctions in neuronal cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1820: 577–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noack H, Kube U, Augustin W. Relations between tocopherol depletion and coenzyme Q during lipid peroxidation in rat liver mitochondria. Free Radic Res. 1994; 20: 375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forsmark-Andree P, Lee CP, Dallner G, Ernster L. Lipid peroxidation and changes in the ubiquinone content and the respiratory chain enzymes of submitochondrial particles. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997; 22: 391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beal MF, Shults CW. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in Huntington's disease and early Parkinson's disease. Biofactors. 2003; 18: 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCarthy S, Somayajulu M, Sikorska M, Borowy-Borowski H, Pandey S. Paraquat induces oxidative stress and neuronal cell death; neuroprotection by water-soluble coenzyme Q10. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004; 201: 21–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bessero AC, Clarke PG. Neuroprotection for optic nerve disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010; 23: 10–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lulli M, Witort E, Papucci L, et al. Coenzyme Q10 instilled as eye drops on the cornea reaches the retina and protects retinal layers from apoptosis in a mouse model of kainate-induced retinal damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 8295–8302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakajima Y, Inokuchi Y, Nishi M, Shimazawa M, Otsubo K, Hara H. Coenzyme Q10 protects retinal cells against oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2008; 1226: 226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nucci C, Tartaglione R, Cerulli A, et al. Retinal damage caused by high intraocular pressure–induced transient ischemia is prevented by coenzyme Q10 in rat. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007; 82: 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Russo R, Cavaliere F, Rombola L, et al. Rational basis for the development of coenzyme Q10 as a neurotherapeutic agent for retinal protection. Prog Brain Res. 2008; 173: 575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qu J, Kaufman Y, Washington I. Coenzyme Q10 in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 1814–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Howell GR, Libby RT, Marchant JK, et al. Absence of glaucoma in DBA/2J mice homozygous for wild-type versions of Gpnmb and Tyrp1. BMC Genet. 2007; 8: e45 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1937007/. Accessed January 24, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang L, Calingasan NY, Wille EJ, et al. Combination therapy with coenzyme Q10 and creatine produces additive neuroprotective effects in models of Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases. J Neurochem. 2009; 109: 1427–1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Howell GR, Libby RT, Jakobs TC, et al. Axons of retinal ganglion cells are insulted in the optic nerve early in DBA/2J glaucoma. J Cell Biol. 2007; 179: 1523–1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ju WK, Kim KY, Lindsey JD, et al. Intraocular pressure elevation induces mitochondrial fission and triggers OPA1 release in glaucomatous optic nerve. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 4903–4911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. John SW, Hagaman JR, MacTaggart TE, Peng L, Smithes O. Intraocular pressure in inbred mouse strains. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997; 38: 249–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duhamel RC, Johnson DA. Use of nonfat dry milk to block nonspecific nuclear and membrane staining by avidin conjugates. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985; 33: 711–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaur R, Dikshit KL, Raje M. Optimization of immunogold labeling TEM: an ELISA-based method for evaluation of blocking agents for quantitative detection of antigen. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002; 50: 863–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nadal-Nicolas FM, Jimenez-Lopez M, Sobrado-Calvo P, et al. Brn3a as a marker of retinal ganglion cells: qualitative and quantitative time course studies in naive and optic nerve–injured retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 3860–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alavi MV, Bette S, Schimpf S, et al. A splice site mutation in the murine Opa1 gene features pathology of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Brain. 2007; 130: 1029–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008; 3: 1101–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lulli M, Witort E, Papucci L, et al. Coenzyme Q10 protects retinal cells from apoptosis induced by radiation in vitro and in vivo. J Radiat Res. 2012; 53: 695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Inman DM, Sappington RM, Horner PJ, Calkins DJ. Quantitative correlation of optic nerve pathology with ocular pressure and corneal thickness in the DBA/2 mouse model of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 986–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gionfriddo JR, Freeman KS, Groth A, Scofield VL, Alyahya K, Madl JE. α-Luminol prevents decreases in glutamate, glutathione, and glutamine synthetae in the retinas of glaucomatous DBA/2J mice. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009; 12: 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sandhu JK, Pandey S, Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of glutamate neurotoxicity in mixed cultures of NT2-derived neurons and astrocytes: protective effects of coenzyme Q10. J Neurosci Res. 2003; 72: 691–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beal MF. Aging, energy, and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann Neurol. 1995; 38: 357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shults CW, Haas RH, Passov D, Beal MF. Coenzyme Q10 levels correlate with the activities of complexes I and II/III in mitochondria from parkinsonian and nonparkinsonian subjects. Ann Neurol. 1997; 42: 261–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beal MF, Matthews RT. Coenzyme Q10 in the central nervous system and its potential usefulness in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 1997; 18 (suppl): S169–S179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferrante RJ, Andreassen OA, Dedeoglu A, et al. Therapeutic effects of coenzyme Q10 and remacemide in transgenic mouse models of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 2002; 22: 1592–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guo L, Cordeiro MF. Assessment of neuroprotection in the retina with DARC. Prog Brain Res. 2008; 173: 437–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bhagavan HN, Chopra RK. Coenzyme Q10: absorption, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Free Radic Res. 2006; 40: 445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tezel G, Chauhan BC, LeBlanc RP, Wax MB. Immunohistochemical assessment of the glial mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 3025–3033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schuettauf F, Rejdak R, Walski M, et al. Retinal neurodegeneration in the DBA/2J mouse: a model for ocular hypertension. Acta Neuropathol. 2004; 107: 352–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bosco A, Inman DM, Steele MR, et al. Reduced retina microglial activation and improved optic nerve integrity with minocycline treatment in the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 1437–1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Park SW, Kim KY, Lindsey JD, et al. A selective inhibitor of Drp1, Mdivi-1, increases retinal ganglion cell survival in acute ischemic mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2837–2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dai Y, Weinreb RN, Kim KY, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase–mediated alteration of mitochondrial OPA1 expression in ocular hypertensive rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 2468–2476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ju WK, Kim KY, Duong-Polk KX, Lindsey JD, Ellisman MH, Weinreb RN. Increased optic atrophy type 1 expression protects retinal ganglion cells in a mouse model of glaucoma. Mol Vis. 2010; 16: 1331–1342 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hernandez MR, Miao H, Lukas T. Astrocytes in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Prog Brain Res. 2008; 173: 353–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Malone PE, Hernandez MR. 4-Hydroxynonenal, a product of oxidative stress, leads to an antioxidant response in optic nerve head astrocytes. Exp Eye Res. 2007; 84: 444–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee I, Lee H, Kim JM, Chae EH, Kim SJ, Chang N. Short-term hyperhomocysteinemia-induced oxidative stress activates retinal glial cells and increases vascular endothelial growth factor expression in rat retina. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007; 71: 1203–1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Luo C, Yang X, Kain AD, Powell DW, Kuehn MH, Tezel G. Glaucomatous tissue stress and the regulation of immune response through glial Toll-like receptor signaling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51: 5697–5707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. McElnea EM, Quill B, Docherty NG, et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and calcium overload in human lamina cribrosa cells from glaucoma donors. Mol Vis. 17: 1182–1191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mattson MP, Pedersen WA, Duan W, Culmsee C, Camandola S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying perturbed energy metabolism and neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999; 893: 154–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wang X, Michaelis EK. Selective neuronal vulnerability to oxidative stress in the brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010; 2: e12 Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2874397/. Accessed January 24, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mehta A, Prabhakar M, Kumar P, Deshmukh R, Sharma PL. Excitotoxicity: bridge to various triggers in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013; 698: 6–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001; 292: 727–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wasiak S, Zunino R, McBride HM. Bax/Bak promote sumoylation of DRP1 and its stable association with mitochondria during apoptotic cell death. J Cell Biol. 2007; 177: 439–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Antonsson B, Conti F, Ciavatta A, et al. Inhibition of Bax channel-forming activity by Bcl-2. Science. 1997; 277: 370–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schlesinger PH, Gross A, Yin XM, et al. Comparison of the ion channel characteristics of proapoptotic BAX and antiapoptotic BCL-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997; 94: 11357–11362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Desagher S, Martinou JC. Mitochondria as the central control point of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2000; 10: 369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993; 74: 609–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 1995; 80: 285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ferreira SM, Lerner SF, Brunzini R, Evelson PA, Llesuy SF. Oxidative stress markers in aqueous humor of glaucoma patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004; 137: 62–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moreno MC, Campanelli J, Sande P, Sanez DA. Keller Sarmiento MI, Rosenstein RE. Retinal oxidative stress induced by high intraocular pressure. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004; 37: 803–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ko ML, Peng PH, Ma MC, Ritch R, Chen CF. Dynamic changes in reactive oxygen species and antioxidant levels in retinas in experimental glaucoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005; 39: 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tezel G, Yang X, Cai J. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified retinal proteins in a chronic pressure-induced rat model of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 3177–3187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Abu-Amero KK, Morales J, Bosley TM. Mitochondrial abnormalities in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006; 47: 2533–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Yuki K, Murat D, Kimura I, Tsubota K. Increased serum total antioxidant status and decreased urinary 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010; 88: e259–e264 Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01997.x/abstract. Accessed January 24, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ekstrand MI, Falkenberg M, Rantanen A, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum Mol Genet. 2004; 13: 935–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yin W, Signore AP, Iwai M, Cao G, Gao Y, Chen J. Rapidly increased neuronal mitochondrial biogenesis after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. Stroke. 2008; 39: 3057–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]