Abstract

Signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE) of a substrate and parahydrogen at a catalytic center promises to overcome the inherent insensitivity of magnetic resonance. In order to apply the new approach to biomedical applications, there is a need to develop experimental equipment, in situ quantification methods, and a biocompatible solvent. We present results detailing a low-field SABRE polarizer which provides well-controlled experimental conditions, defined spins manipulations, and which allows in situ detection of thermally polarized and hyperpolarized samples. We introduce a method for absolute quantification of hyperpolarization yield in situ by means of a thermally polarized reference. A maximum signal-to-noise ratio of ∼103 for 148 μmol of substance, a signal enhancement of 106 with respect to polarization transfer field of SABRE, or an absolute 1H-polarization level of ≈10–2 is achieved. In an important step toward biomedical application, we demonstrate 1H in situ NMR as well as 1H and 13C high-field MRI using hyperpolarized pyridine (d3) and 13C nicotinamide in pure and 11% ethanol in aqueous solution. Further increase of hyperpolarization yield, implications of in situ detection, and in vivo application are discussed.

Magnetic resonance (MR) is an invaluable tool which finds application in many research fields despite its inherent insensitivity. This situation holds true even when employing the strongest available superconducting magnets which exceed the earth’s magnetic field strength by 100 000 times. This is because only a miniscule fraction of the nuclear spins present in a sample contribute positively to the detected MR response when their alignment is thermally controlled. For the most commonly analyzed spin, 1H (spin 1/2), this is, in effect, the population difference that exists across addressable spin states and amounts to only 3 spins per million per Tesla (T). The situation is far worse for all other stable nuclei because their interactions with the magnetic field are even weaker. As a consequence, while NMR is an essential tool in the analytical chemist’s arsenal, there is a significant need to improve the detection limits which will open up many new areas of analysis and diagnosis.

Hyperpolarization (hyp) methods can be used to address the poor thermal distribution of spins and have been discussed and employed for some time. Common sources of such hyperpolarized spin order include polarized light,1−4 electron spin,5−8 and parahydrogen (pH2).9−15 Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) is currently one of the most frequently used methods, due to its flexibility in hyperpolarizing a wide range of molecules as well as its commercial availability and well-developed experimental approach.

Utilization of pH2, the nuclear spin-singlet of dihydrogen, was suggested as a potential route to MR signal enhancement in the 1980s, where “pH2 and synthesis allow dramatically enhanced nuclear alignment” (PASADENA), “pH2 induced polarization” (PHIP), and “adiabatic longitudinal transport after dissociation engenders net alignment” (ALTADENA) reflect the early approaches.9−12 These methods rely on adding the spin order of a single pH2 molecule into a target dihydrogen acceptor, by means of hydrogenation.

A wide range of studies have been reported that use this approach to probe catalysis16−18 and support biomedical in vivo imaging.19−23 Some of these results have employed polarization transfer to longer-lived 13C nuclei by means of r.f. sequence application.14,24 The quality control and equipment necessary for in vivo experimentation has been described, but the technique is not yet available as a “push-button” method.25−28 Recently, the detection and quantification of 13C-polarization achieved via such a transfer at a B0 field of ≈50 mT29 and steps toward a catalyst-free pH2-hyperpoalrization30 was presented and this can be considered as an important step in moving toward routine and reliable biomedical application.

In 2009 it was demonstrated that pH2 does not need to actually be incorporated into the target. Instead, pH2 and a substrate were brought into reversible interaction at a metal center. When this process occurs in an appropriate magnetic field, BS, strong hyperpolarization is observed and this was termed SABRE.31,32 SABRE stands for signal amplification by reversible exchange and, although a method in its infancy, its potential to achieve rapid hyperpolarization has resulted in significant research interest. Published work has focused thus far on demonstrating its potential for chemical analysis.33−35 Typically, SABRE has been reported to occur in a methanol solution, after shaking a sample to introduce pH2 in a stray field (∼5 × 10–3 T). Upon transfer into a high-field magnet, hyperpolarized signals have been observed in the free substrate. This process is illustrated in Figure 1, which demonstrates the simplicity of SABRE. Methanol, however, is neither biocompatible nor suited for in vivo measurements.

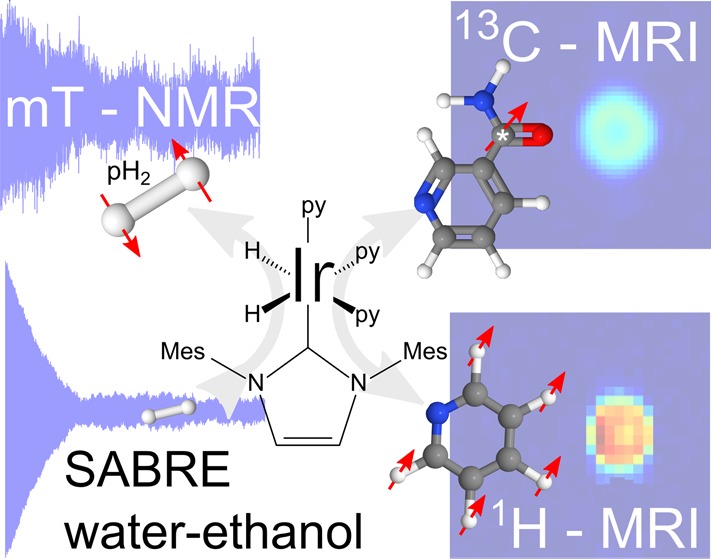

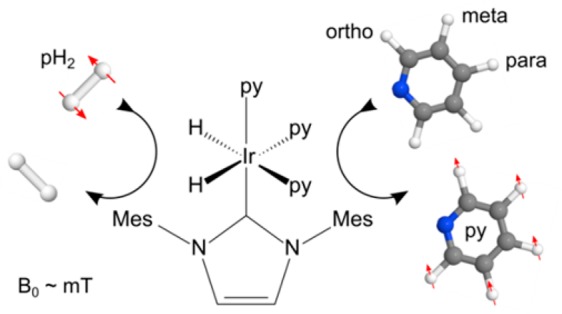

Figure 1.

Schematic of SABRE: The pure and NMR-invisible spin order of pH2 is transferred into observable hyperpolarization of the pyridine (py) target during their temporary contact, in low field, mediated by the metal complex. The red arrows indicate how spin-order equilibration leads to hyperpolarization in the ortho-, meta- and para-1H-nuclei of the free pyridine receptor.

Accurate experimental conditions, the absolute quantification of the level of hyperpolarization in situ, and biocompatible solvents are important milestones for SABRE toward biomedical application, which have not yet been addressed in the literature. In this contribution, we will detail the following: (i) a SABRE polarizer which provides well-controlled experimental conditions and enables reproducible and repeatable in situ detection in various solvents, (ii) a method for absolute quantification of in situ hyperpolarization at low field, and also following transfer to high field, and (iii) NMR of SABRE hyperpolarized pyridine at Earth-, SABRE-, and high-field, as well as MRI of 13C-nicotinamide in pure ethanol and an ethanol–water mixture.

Materials and Methods

ParaHydrogen

pH2 with a purity of >95%, as described elsewhere, was used in this study.36 A volume of 3 L of pH2 at a pressure of ≈35 bar was produced and stored in an aluminum cylinder prior to completion of SABRE.

Chemistry

The SABRE catalyst reported37 and recently investigated further38 Ir(1,5-cyclooctadiene) (1,3-bis (2,4,6-trimethylphenyl) imidazolium) Cl (MW = 639.67 g/mol) was employed to polarize pyridine (py, MW = 79.1 g/mol, Carl Roth, Germany). Catalyst and substrate were dissolved in (a) 99.8% methanol-d4 (Carl Roth, Germany), (b) 100% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich), or (c) 100% ethanol followed by dilution with water in the ratio 1:9.

13C-Nicotinamide Route 1

13C-nicotinic acid (744 mg, 6 mmol) was added to SOCl2 (2 mL) heated to 80 °C for 2 h and then allowed to cool. The excess SOCl2 was removed in vacuo, and the resulting acid chloride was added dropwise to a cooled (0 °C) conc. ammonia solution (5 mL). The solution was subsequently concentrated in vacuo and the crude product purified via column chromatography (10% MeOH in DCM) to afford the product as an off-white powder (280 mg, 38%).

13C-Nicotinamide Route 2

From methyl-13C-nicotinoate, 600 mg, 3.89 mmol was added to a solution of MeOH (5 mL) and conc. ammonia solution (5 mL), and the reaction stirred for 18 h at 20 °C. The solution was subsequently concentrated in vacuo and the crude product purified via column chromatography (10% MeOH in DCM) to afford the product as an off white powder (362 mg, 76%).

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): 8.99 (app. td, J = 2.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (ddd, J = 5.0, 1.7, 0.6 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (dddd, J = 8.0, 3.9, 2.3, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (app. ddt, J = 8.0, 5.0, 0.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz): 170.0 (13C), 153.0 (d, J = 0.6 Hz), 149.6 (d, J = 3.5 Hz), 137.5 (d, J = 2.1 Hz), 131.6 (d, J = 63.4 Hz), 125.3 (d, J = 3.3 Hz). MS (ESI) m/z (rel.%): 124 [M + H]+ (100), 85 (24), 61 (24). HRMS (ESI) calculated for 13C12C5H7N2O, 124.0586; found, 124.0590.

The synthesis of 3,4,5-trideuterio-pyridine extends upon a route described by Cowley et al.37 and Pavlik et al.39

In Situ and Field-Cycling Polarizer

The solution composed of solvent, catalyst, and substrate was placed in a reaction chamber that was manufactured from polysulfone and withstands a pressure of 15 bar (Figure 2b,c, length 8 cm, radius 2.75 cm, inner volume 13.3 mL).27 PTFE tubing was connected to the ports of the reaction chamber to allow pH2 injection, gas venting, and solution transfer, controlled by electromagnetic solenoid valves. The chamber was placed into the low-field NMR or Earth’s field cycling setup as described below. To allow shaking of the chamber, a vortexer was placed outside of the B0 coil and connected to the reaction chamber’s holder (Figure 2d,e) using an acrylic rod.

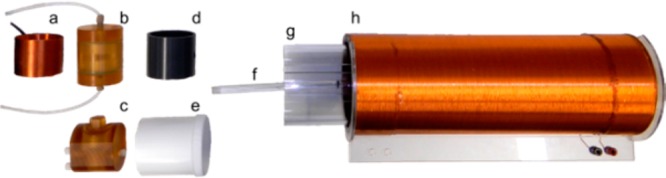

Figure 2.

Experimental equipment used for in situ SABRE hyperpolarization and quantification: (a) low-field transmit and receive coil (f0 ≈ 230 kHz), (b,c) typical reaction chambers, (d,e) reaction chamber holders, (f,g) mixing device, (h) electromagnet used to establish a uniform and well-defined polarization transfer field BS.

In Situ Low-Field NMR

We modified the recently presented prototype for NMR at very low fields40 for quantitative in situ detection of thermally and hyperpolarized samples. A static magnetic field was generated by the illustrated, numerically optimized, resistive solenoid (Figure 2h, length 35 cm, radius 6 cm, two layers of copper wire r = 0.5 mm, additional windings on the ends to improve homogeneity). Simulations predicted a very high level of homogeneity within the area of the reactor as the difference between Bmax and Bmin is only ≈8.6 × 10–7 T. The magnet was powered by a low-noise battery-driven current controller.40

For signal excitation and detection, a solenoid transmit-receive coil was constructed to fit around the reaction chamber. (Figure 2a,b, f0 ≈ 230 and 270 kHz, 2.75 cm radius, 4.4 cm length, 280 μm wire diameter, capacitance 390 pF). Crossed diodes were added in the transmission path for rapid passive switching between transmission and receive. Excitation pulses were generated using a digital-to-analog converter controlled by custom software (6251 USB, National Instruments and Matlab, The Mathworks). The NMR signal was detected in the same device, 1–2 ms after excitation.

The 1H NMR flip angle was adjusted as optimized signal from deionized water at thermal equilibrium and 5.4 mT. The resulting flip-angle error is estimated to 1°.40 The experimentally observed line widths vary between 10 and 45 Hz, likely depending on the filling of the reactor. For SABRE, the reaction chamber was held in the center of the magnet and was connected to a commercial vortexer (Figure 2d,f) which allowed for efficient gas mixing (optionally).

Field-Cycling NMR

Flip angles and field homogeneity of the field-cycling NMR and MRI unit (Terra-Nova, Magritek, NZ) were adjusted according to the MR signal of a water sample that was prepolarized for 4 s at 20 mT. For hyperpolarization experiments, fresh pH2 was supplied for every acquisition to the headspace of the reaction chamber (Figure 2c). The SABRE process was established under a transfer field, BS, that could be set between 0.5 and 24 mT and held constant for 4 s. The BS field was then turned off and the sample interrogated by a simple 90°-pulse-acquisition experiment in the shimmed Earth’s field at ≈2.1 kHz (50 μT). In view of the fact that there is a need to prepolarize the nonhyperpolarized reference sample, an absolute quantification of the hyperpolarized signal cannot easily be made in such a field cycling device.

High-Field MRS and MRI

A glass vial was filled with water and placed in the MRI or NMR system for calibration (two Biospec, 70/20 Avance III for 1H MRS and 13C MRI or 400 MHz, 89 mm vertical bore DRX for 1H MRI, Bruker, Germany). For SABRE, an appropriate solution was placed into the vial and sealed. pH2 was introduced into the solution through either a Young’s valve or a syringe needle. After ≈10 s in a field of between 1 and 6.5 mT, the sample was introduced into the high-field magnet and either nonlocalized spectra or MRI data were recorded within seconds.

All proton images were acquired using the RARE pulse sequence,41 a single-shot method which allows for acquisition times shorter than or of the order of 1 s. For the pyridine and pyridine-d3 images, methanol-d4 was employed as the solvent and the acquisition parameters used were echo time (TE) 7.5 ms, field of view (FOV) 40 mm × 40 mm, slice thickness 2 mm, and acquisition matrix 64 × 64. The associated parameters used to collect the 13C-nicotinamide image reported here in methanol or ethanol solution were TE 7.5 ms, FOV 6 cm × 6 cm, slice thickness 30 mm, and acquisition matrix 32 × 32, zero-filled to 128 × 128.

Quantification Methods

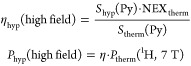

High-field data were processed using the manufacturer’s Paravision and Topspin package and Matlab. The signal enhancement (η) and absolute polarization yield (Phyp) for spectra was quantified by comparing the integral of the hyperpolarized signal Shyp to the signal in thermal equilibrium Stherm of the sample, acquired with identical parameters as shown in eq 1. For imaging, if the thermal signal of the nonhyperpolarized sample was too low for direct detection, the signal of a second sample was used as reference. However, quantification of the absolute hyperpolarization yield is exacerbated by relaxation weighting of the sequence and different relaxation properties of sample and reference. Thus, in this work, we report an apparent enhancement of contrast instead of absolute signal enhancement.

|

1 |

where Ptherm (1H, 7T) = 2.5 × 10–5.

A similar problem presents itself for low-field NMR. It was pointed out before that direct detection of MR signal at ≈10–3 T in a single acquisition is not possible but requires prepolarization at much higher fields, as only 3 ppb of all spins effectively contribute to the signal.42 Only recently, we presented the detection of a thermally polarized MR signal at 10–3 T after a single excitation.40 The apparatus described here improves on this by using reaction chambers and exploiting dedicated transmit-receive coils fitted to the chamber. Even with this equipment, however, the amount of nonhyperpolarized substrate is far too low for its direct detection. Under these conditions, the level of hyperpolarization was quantified by reference to the thermal signal of a 0.74 M H2O sample. Of the 1.48 mol of protons in this sample, 1/4 are invisible as they are in the para-state43 and do not contribute to the signal. Consequently, the signal arises for an effective 1.1 mol of protons. Area, line width, and peak height data were obtained by fitting a Lorentzian function to the detected low-field resonances (Matlab). The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) was calculated by dividing the height of the resonance at 230 kHz by the standard deviation of the data between 216 and 228 kHz.

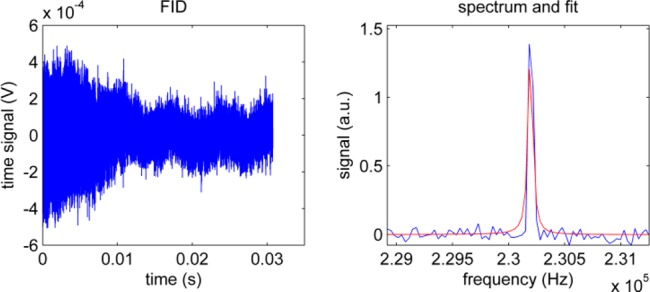

The area of the H2O reference spectrum in Figure 3 was quantified as 104.7 au (NEX = 10 free-induction decays, TR = 15 s, α = 90°, T1 (H2O, 5.4 mT) ≈ 2.7 s). The summed spectra, and the mean of the individual spectra, exhibited a SNRNEX=10 of 88.9 and SNRNEX=1 of 31.4, respectively. Thus, in thermal equilibrium at this field, the limit of detection (SNR = 2) was ≈70 mmol of water protons, which corresponds to about 1 nmol of polarized spins.

Figure 3.

Low-field 1H-NMR reference signal of H2O used for quantification of the 1H-hyperpolarization yield. Sum of 10 free induction decays (left) and real spectrum with fit (right) of 0.74 mol of deionized H2O detected in thermal equilibrium at B0 = 5.4mT (TR = 15 s, fwhm = 45 Hz, SNR = 89).

The associated full-width at half-maximum (fwhm) of the line of the H2O sample were fwhmNEX=10 = 45 Hz and fwhmNEX=1 = 42 Hz, respectively. These data demonstrate a near stable field homogeneity throughout the experiment, which accounts for the 10% lower than expected SNR increase.

The 1H polarization in thermal equilibrium at 290 K is 1.90 × 10–8 at 5.4 mT. This leads to the following equations for signal enhancement (η) and absolute polarization yield (eq 2).

|

2 |

where Shyp and Stherm are the area of hyperpolarized and thermally polarized resonances, NEX is number of excitations, and nA is the amount of substance.

At 5.4 mT, a 45 Hz line-width equates to ≈200 ppm, which is now 2 orders of magnitude above the typical chemical shift range of 1H resonances. Consequently, the 1H resonances for all molecules are collapsed into one peak during these measurements. In the case of SABRE-derived magnetization in low field, the single line is comprised of all the coherence order created by the simple excitation pulse. Thus, even though significant polarization can be detected, it cannot be attributed to an individual proton resonance. Furthermore, any variation in phase across proton resonances, as is typical in SABRE or PHIP, may cancel a portion of the detected signal. The hyperpolarization level achieved for pyridine is therefore reported per molecule as a whole, which holds five protons. The enhancement of each of these hydrogen nuclei is known to vary in high field, in both phase and magnitude, but are treated equally here because we cannot resolve such effects in low field.

Results

In Situ Detection and Quantification at Low Field in Methanol

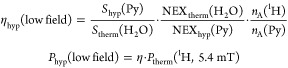

When a thermally polarized 148 μmol sample of pyridine in 4.7 mL of methanol-d4 and 2 mM catalyst was monitored at 5.4 mT, no 1H signal is observed, as was expected. However, when pH2 was utilized to activate the SABRE effect, a substantial signal was observed indicative of strong enhancement. The SNR achieved for the data in Figure 4 that was collected with one acquisition was 1.67 × 103. Compared to the fitted peak area of a H2O reference, a signal enhancement value, ηhyp of 320 × 103 was estimated. This corresponds to an absolute polarization level of ≈0.6% (eq 2) and confirms that low concentration analytes can be readily detected through SABRE even at low field.

Figure 4.

Representative low-field 1H-NMR time-domain data, spectrum and fit obtained in situ for 148 μmol of SABRE hyperpolarized pyridine in 4.7 mL of CD3OD in the presence of 2 mM catalyst at 5.4 mT with a SNR of 1.6 × 103 confirming that low concentration analytes can be observed in a single acquisition.

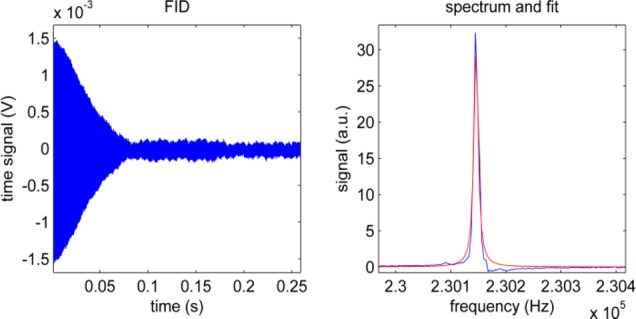

In Situ Detection and Quantification at Low Field in Pure and Diluted Ethanol

A strong signal was also observed when this enhancement method was applied to 35 mg of pyridine and 14 mg of catalyst dissolved in either 4 mL of ethanol or 9:1 H2O–ethanol mixture. In these cases, polarization levels of 0.2 and 0.02%, respectively, were achieved in situ (Figure 5). These correspond to signal enhancement, ηhyp, values of between 104 and 105. No difference was observed if the catalyst was activated with H2 before or after the addition of water, nor when the amount of ethanol was reduced to 0.4 mL, which, after dilution, may be considered an important first step toward SABRE-hyperpolarized in vivo MRI.

Figure 5.

Low-field 1H NMR time-domain data, spectrum, and fit of hyperpolarized Py in 4 mL of 9:1 water–ethanol mixture in situ at 6.3 mT. The irregular line shape may be attributed to inhomogeneities associated with the injection of pH2.

As stated above, the single resonance observed in Figures 4 and 5 reflects the sum of the contributing SABRE hyperpolarization from all individual proton sites. A fifth of the polarization may be attributed to each.

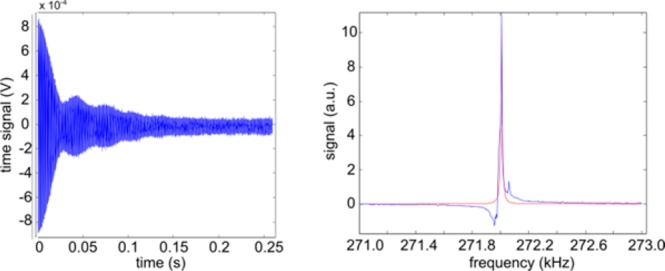

Chemical Shift Resolution at High Field

To shed light on the phase distribution, we have acquired high-field spectra. We seek here to compare measurements at low and high field and consider how changes from the transfer field, BS, (of order 10–3 T) to the measurements fields affects the results.

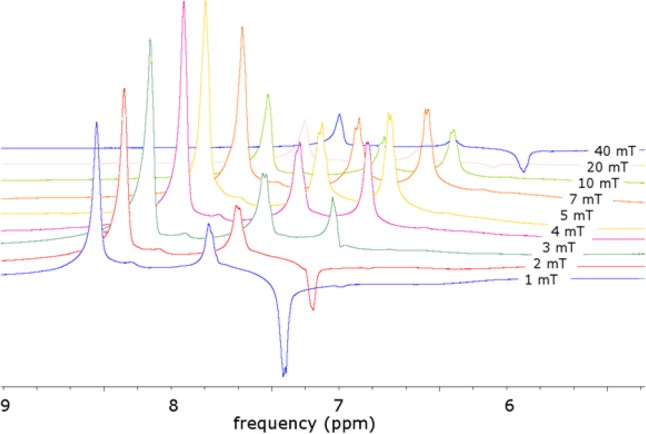

When the analogous SABRE-polarized sample consisting of 5.8 mg of catalyst, 11.8 mg of Py in 4.2 mL of methanol-d4 was transferred to high field, chemical-shift resolved signals for the three distinct proton sites of pyridine were observed that show phase variations according to the transfer field BS. These data are reproduced in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

1H-NMR spectra of hyperpolarized pyridine in methanol-d4 acquired on a 7 T MR imager, polarized at low field over a range of BS = 1–40 mT. The spectra were integrated with the phase as shown and plotted as circles in Figure 7

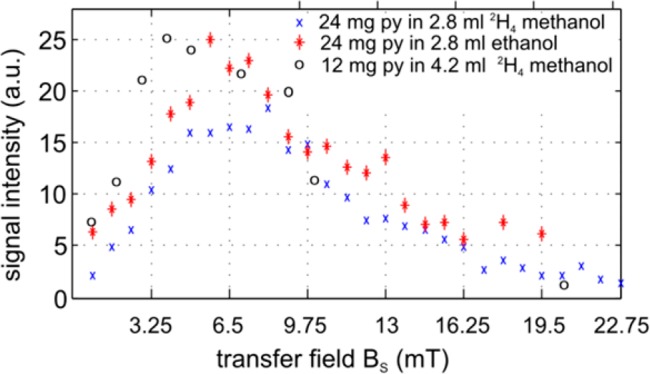

The highest hyperpolarization yield was detected when the mixing BS field was between 4 and 7 mT. In this region, all the detected high field signals are in phase. It is also possible to sum the associated signal intensities to estimate what might be observed in low field. The data obtained via this route are indicated in Figure 7 by circles, which suggest that the optimum polarization transfer field is the similar regardless of where the measurement is made. Note, though, that the sample experienced fields ranging from BS ≈ 10–3 T during SABRE, Btransfer ≈ 10–5 T during transfer, and Bdetection ≈ 101 T at detection.

Figure 7.

Signal intensities of hyperpolarized pyridine in methanol-d4 and ethanol as a function of the transfer field, BS, over the range 0.5–22 mT. Signals were detected at Earth field (× and ∗) or at 7 T (○). The latter were scaled to the same maximum value.

Solvent Effects Monitored by in Situ Detection at Low Field

A more precise measure of the effects due to field change was estimated by using the field-cycling system. In this apparatus, the sample experiences less field variations as no transfer is necessary, namely, an initial field of BS ≈ 10–3 T for SABRE and Bdetection ≈ 10–5 T for detection. BS was varied between 0 and 22.75 mT and the resulting data is displayed in Figure 7, along with the integrals of the high-field spectra as described in the previous section, scaled to fit. The signal maxima for SABRE in methanol and ethanol occur with very similar BS-field values. When the rates of magnetization build-up are considered as a function of the duration of the BS period for each solvent, the signals in ethanol were found to appear with twice the growth rate of those in perdeuterated methanol at 4 and 8 s, respectively. These time constants describing the polarization build-up indicate that the maximum polarization is not achieved while the transfer field BS is applied for 4 s. A total of 9 mg of catalyst were used.

Enhanced Polarization through Isotopic Substitution

Because of the fact that pyridine has three magnetically nonequivalent protons, three separate enhanced resonances were identified in high-resolution liquid-state 1H NMR spectra in CD3OD, located at 8.5, 7.8, and 7.4 ppm, respectively. While this may represent an advantage in some cases, as it allows for an in-depth investigation of the influence of the mixing field on the enhancement at various sites (see previous section), it raises significant difficulties when pyridine is used in imaging experiments. Not only is the magnetization transferred to several protons, leading to relatively low average polarization levels in an image, but the fast relaxation rates and the chemical shift artifacts which arise from the presence of nonequivalent nuclei, further lower the results’ quality and contrast.

In order to circumvent this situation, pyridine-3,4,5-d3 was prepared. Pyridine-3,4,5-d3 presents the obvious advantage that the magnetization is transferred to the only remaining two (equivalent) ortho-protons, which furthermore have slower relaxation rates compared to the nondeuterated molecule of 31 s in methanol-d4.

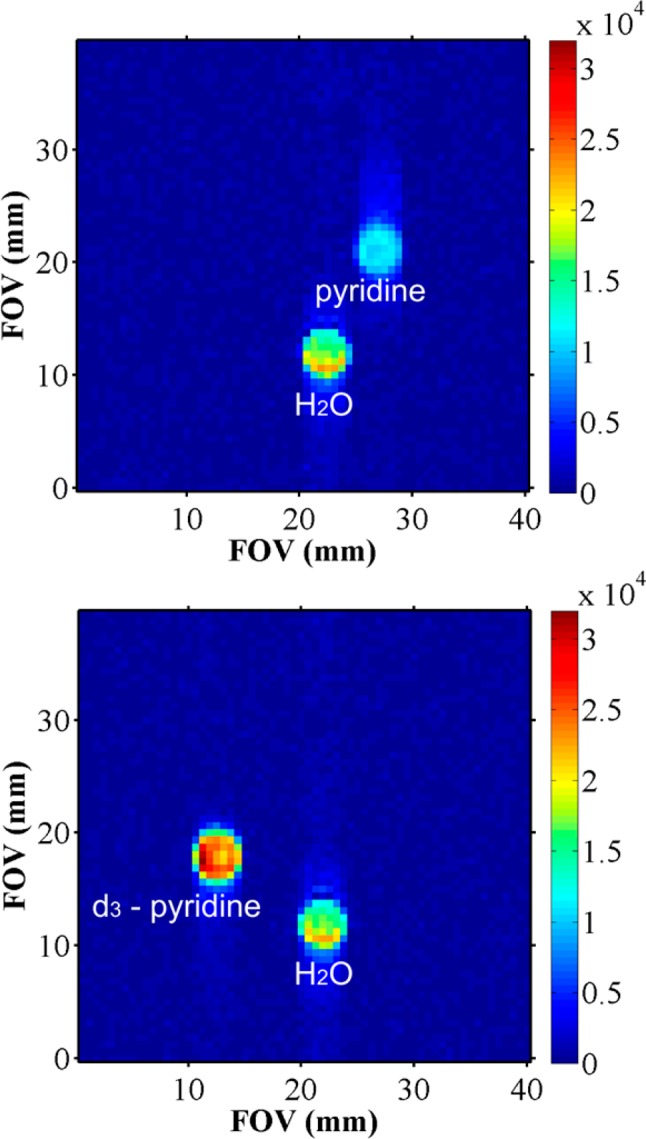

2D magnetic resonance imaging data of milligrams of hyperpolarized pyridine and hyperpolarized pyridine-d3, respectively, in 0.6 mL of CD3OD and 2 mg of catalyst were acquired in order to illustrate the strong effect isotopic substitution can have on the signal.

A 169-fold apparent contrast enhancement was calculated based on a H2O internal standard for the image of the sample containing pyridine (Figure 8, top). When analyzing the images acquired on the sample prepared with deuterated substrate, upon comparison with the reference sample, a contrast enhancement ηhyp of 807 was obtained. This enhancement corresponded to an apparent polarization level of 2.5% (Figure 8, bottom). The associated increase in polarization level is due to the more efficient transfer of magnetization during SABRE to fewer proton sites in 3,4,5-d3-pyridine and the longer T1 value for the remaining two protons.

Figure 8.

1H-RARE image of hyperpolarized pyridine (top) and pyridine-3,4,5-d3 (bottom), each with a reference sample, dissolved in methanol and acquired at 9.4 T. A stronger signal was observed from SABRE when the deuterated substrate was used.

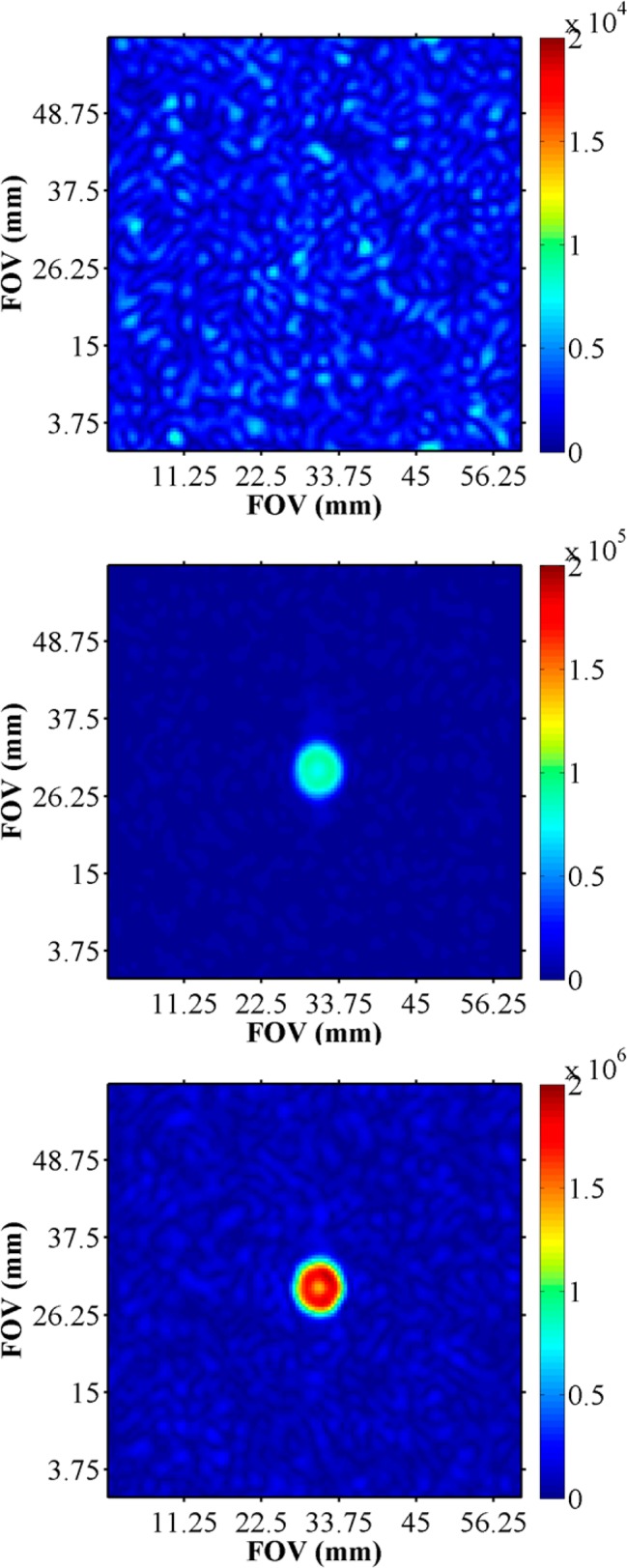

High-Field 13C-Imaging of SABRE-Derived Signals

Given the established utility of exploiting the long T1 of 13C by in vivo DNP and PHIP, we have also investigated the hyperpolarization of a 13C in a carbonyl group using SABRE. This involved the initial preparation of a sample of 13C-enriched nicotinamide. The resulting 13C-MRI of hyperpolarized nicotinamide that was detected in a single acquisition where Phyp is 0.03% is shown in Figure 9. Solution volumes were 0.6 mL methanol-d4 with 2 mg of catalyst and 5 mg of substrate.

Figure 9.

Single-acquisition 13C-RARE MRI at 7 T of a 8 mm diameter phantom containing 13C-labeled nicotinamide in methanol-d4, before (top) and during hyperpolarization using the SABRE method (middle). Both images took approximately 1 s to acquire. Bottom: Comparative image of the sample in thermal equilibrium collected with 1100 averages that took 18 h 20 min used to establish the level of 13C signal enhancement was 65-fold, corresponding to a polarization of 0.03%.

Discussion

In this paper we investigated the intricacies of SABRE hyperpolarization in a wide range of fields, at ≈10–3 T in situ, at ≈10–5 T in the Earth’ field, and at ≈101 T in the high fields of superconducting magnets. Furthermore, we investigated biocompatible solvents and demonstrated high-field 1H and 13C MR imaging of isotopically enriched substances with respect to an in vivo application.

We have shown that a recently developed low-field MR system allows in situ signal detection and quantification by means of using a thermally polarized reference. This has enabled us, for the first time, to monitor and quantify the SABRE hyperpolarization yield at BS, the point of polarization transfer. It has been shown that in the case of pyridine a signal enhancement value ηhyp of 320 × 103 results which equates to ≈0.6% 1H polarization and is sufficient for MRI detection. To generate an equal polarization in thermal equilibrium at room temperature, a magnetic field of ≈3000 T would be required.

While this represents a signal enhancement of 6 orders of magnitude compared to BS, it is still two orders below unity. Higher pressure or other means to increase the pH2 concentration in solution may be used to increase the hyperpolarization yield further. This is supported by preliminary findings that the hyperpolarization yield increased ≈2.5-fold by doubling the pH2 pressure from 5 to 10 bar. Given the lower solubility of H2 in H2O, which is roughly 0.8 mM compared to 4 mM in methanol at 1 bar and room temperature, we expect this to be very important in studies using water.

The in situ detection approach offers several advantages over the conventional high-field detection methods which necessarily involve sample transport and hence a delay where relaxation can occur. There is also the possibility of further spin state evolution during the transfer process which typically takes several seconds. The data presented here suggest that such effects do not strongly affect the optimal field for SABRE, BS, for the compound investigated. What is clear, however, is that there is no need to fully commit an expensive instrument to developing this phenomenon, as many important observations can be made at low field without chemical shift resolution (e.g., new agents or catalysts). Furthermore, interesting low-field application may emerge.

Many of the molecules SABRE hyperpolarizes contain nonequivalent nuclei. In order to observe the relative signal amplitudes that result from the probing of these environments, separate resonances are required. As Figure 6 reveals, these effects can be substantial. Figure 7, however, shows that both in situ and high-field detection provide a similar view of the effect BS plays on the overall signal response of pyridine. The advantage of an in-phase signal was pointed out before32,44 and is being investigated.

When pyridine is examined using NMR imaging, significant artifacts may arise due to the multiple frequency responses. This problem is not present at low field, where the signals overlap due to the smaller frequency range over which the chemical shift is dispersed. However the net signal amplitude which is detected must be reduced due to internal cancellation as reflected in Figure 6. A strategy that overcomes internal cancellation is provided by deuteration and the examination of pyridine-3,4,5-d3 or other single-resonance molecules. In this case, as the SABRE effect transfers spin-polarization into just two protons on pyridine, rather than the more usual five, and their relaxation time is extended, superior signal gains and hence better images are obtained in a very short amount of time.

A similar situation where a single resonance is detected is illustrated by using the biomolecule 13C-nicotinamide. This molecule readily yields a 13C-MR image through SABRE, albeit the polarization level is relatively low. Now as the T1 of 13C nuclei are longer than 1H and no thermal background is visible, ultrafast in vivo imagining can be facilitated using this approach.

The key requirement for in vivo measurements of SABRE, however, is a biocompatible solvent, which is illustrated here in conjunction with ethanol and ethanol–water mixtures, where further dilution is possible. This route may be necessary until water-soluble catalysts are developed that deliver high polarization.

Conclusion

By means of a dedicated experimental setup and reference to a thermally polarized sample, in situ detection and absolute quantification of SABRE hyperpolarization was achieved in methanol, ethanol, and aqueous ethanol. 1H and 13C NMR imaging of hyperpolarized pyridine and 13C-nicotinamide was demonstrated. Pure ethanol was found to be an efficient solvent for the catalyst, offering the perspective for first in vivo experiments in conjunction with biomolecules such as nicotinamide. In situ detection while SABRE takes place offers an interesting perspective of using renewing hyperpolarization.

These results demonstrate that no extensive hardware is required for highly sensitive NMR in aqueous solution. Because SABRE, unlike other hyperpolarization methods, does not necessitate extensive equipment and pH2 may be stored for days to weeks, it may provide for mobile hyperpolarization on-demand. Its combination with portable, low-field MR systems45 may open up new, previous inaccessible applications, including mobile diagnostic MRI or chemical analysis by NMR.

Acknowledgments

Jan-Bernd Hövener wishes to thank the Academy of Excellence of the German Science Foundation and the Innovationsfonds of Baden-Würtemberg. The Wellcome Trust (Grants 092506 and 098335) and the University of York are also thanked for supporting this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Bhaskar N. D.; Happer W.; McClelland T. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 49, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert M.; Grossmann T.; Heil W.; Surkau R.; Leduc M.; Bachert P.; Knopp M. V.; Schad L. R.; Thelen M. Lancet 1996, 347, 1297–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M. S.; Cates G. D.; Driehuys B.; Happer W.; Saam B.; Springer C. S.; Wishnia A. Nature 1994, 370, 199–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder L.; Lowery T. J.; Hilty C.; Wemmer D. E.; Pines A. Science 2006, 314, 446–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser K. H.; Stehlik D. Adv. Magn. Reson. 1968, 3, 79–139. [Google Scholar]

- Abragam A.; Goldman M. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1978, 41, 395–467. [Google Scholar]

- Ardenkjaer-Larsen J. H.; Fridlund B.; Gram A.; Hansson G.; Hansson L.; Lerche M. H.; Servin R.; Thaning M.; Golman K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003, 100, 10158–10163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batel M.; Krajewski M.; Weiss K.; With O.; Däpp A.; Hunkeler A.; Gimersky M.; Pruessmann K. P.; Boesiger P.; Meier B. H.; Kozerke S.; Ernst M. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 214, 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers C. R.; Weitekamp D. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5541–5542. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenschmid T. C.; Kirss R. U.; Deutsch P. P.; Hommeltoft S. I.; Eisenberg R.; Bargon J.; Lawler R. G.; Balch A. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 8089–8091. [Google Scholar]

- Pravica M. G.; Weitekamp D. P. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1988, 145, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Haake M.; Natterer J.; Bargon J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 8688–8691. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Johannesson H. C. R. Phys. 2005, 6, 575–581. [Google Scholar]

- Chekmenev E. Y.; Hövener J.; Norton V. A.; Harris K.; Batchelder L. S.; Bhattacharya P.; Ross B. D.; Weitekamp D. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4212–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S. B.; Mewis R. E. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1247–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S. B.; Wood N. J. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 2278–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Green R. A.; Adams R. W.; Duckett S. B.; Mewis R. E.; Williamson D. C.; Green G. G. R. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2012, 67, 1–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golman K.; Axelsson O.; Jóhannesson H.; Månsson S.; Olofsson C.; Petersson J. s. Magn. Reson. Med. 2001, 46, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövener J.-B.; Chekmenev E. Y.; Harris K. C.; Perman W. H.; Tran T. T.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. 2009, 22, 123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya P.; Chekmenev E.; Reynolds W.; Wagner S.; Zacharias N.; Chan H.; Bünger R.; Ross B. D. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias N.; Chan H.; Sailasuta N.; Ross B. D.; Bhattacharya P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trantzschel T.; Plaumann M.; Bernarding J.; Lego D.; Ratajczyk T.; Dillenberger S.; Buntkowsky G.; Bargon J.; Bommerich U. Appl. Magn. Reson. 2012, 44, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Johannesson H.; Axelsson O.; Karlsson M. C. R. Chim. 2006, 9, 357–363. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman M.; Johannesson H.; Axelsson O.; Karlsson M. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2005, 23, 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlecek S.; Vahdat V.; Nakayama T.; Ng D.; Emami K.; Rizi R. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövener J.-B.; Chekmenev E.; Harris K.; Perman W.; Robertson L.; Ross B.; Bhattacharya P. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. 2009, 22, 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agraz J.; Grunfeld A.; Cunningham K.; Li D.; Wagner S. J. Magn. Reson. 2013, 235, 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell K. W.; Coffey A. M.; Chekmenev E. Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtunov K. V.; Zhivonitko V. V.; Skovpin I. V.; Barskiy D. A.; Salnikov O. G.; Koptyug I. V. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 22887–22893. [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. W.; Duckett S. B.; Green R. A.; Williamson D. C.; Green G. G. R. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 194505–194515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams R. W.; Aguilar J. A.; Atkinson K. D.; Cowley M. J.; Elliott P. I. P.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G. R.; Khazal I. G.; López-Serrano J.; Williamson D. C. Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd L. S.; Adams R. W.; Bernstein M.; Coombes S.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G. R.; Lewis R. J.; Mewis R. E.; Sleigh C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12904–12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöggler S.; Emondts M.; Colell J.; Müller R.; Blümich B.; Appelt S. Analyst 2011, 136, 1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöggler S.; Müller R.; Colell J.; Emondts M.; Dabrowski M.; Blümich B.; Appelt S. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 13759–13764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hövener J.-B.; Bär S.; Leupold J.; Jenne K.; Leibfritz D.; Hennig J.; Duckett S. B.; von Elverfeldt D. NMR Biomed. 2013, 26, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley M. J.; Adams R. W.; Atkinson K. D.; Cockett M. C. R.; Duckett S. B.; Green G. G. R.; Lohman J. A. B.; Kerssebaum R.; Kilgour D.; Mewis R. E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6134–6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerdenburg B. J. A.; van Glöggler S.; Eshuis N.; Engwerda A. H. J. (Ton); Smits J. M. M.; Gelder R.; de Appelt S.; Wymenga S. S.; Tessari M.; Feiters M. C.; Blümich B.; Rutjes F. P. J. T. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7388–7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik J. W.; Laohhasurayotin S. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2007, 44, 1485–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak R.; Schwaderlapp N.; Huethe F.; Fischer E.; Lickert T.; Bär S.; Hennig J.; Elverfeldt D.; Hövener J.-B. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phys. 2013, 26, 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig J.; Nauerth A.; Friedburg H. Magn. Reson. Med. 1986, 3, 823–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöggler S.; Blümich B.; Appelt S. Top. Current Chem. 2011, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carravetta M.; Johannessen O. G.; Levitt M. H. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 153003-1–153003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dücker E. B.; Kuhn L. T.; Münnemann K.; Griesinger C. J. Magn. Reson. 2012, 214, 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danieli E.; Perlo J.; Blümich B.; Casanova F. Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 4227–4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]