Abstract

Stress is a hypothesized pathway in socioeconomic status (SES)-physical health associations, but the available empirical data are inconsistent. In part, this may reflect discrepancies in the approach to measuring stress across studies, and differences in the nature of SES-stress associations across demographic groups. We examined associations of SES (education, income) with general and domain-specific chronic stressors, stressful life events, perceived stress, and stressful daily experiences in 318 Mexican–American women (40–65 years old). Women with higher SES reported lower perceived stress and fewer low-control experiences in everyday life (ps < .05), but greater chronic stress (education only, p < .05). Domain-specific analyses showed negative associations of income with chronic housing and financial stress (ps < .05), but positive associations of SES with chronic work and care-giving stress (all ps < .05 except for income and caregiving stress, p < .10). Sensitivity analyses showed that most SES-stress associations were consistent across acculturation levels. Future research should adopt a multi-dimensional assessment approach to better understand links among SES, stress, and physical health, and should consider the sociodemographic context in conceptualizing the role of stress in SES-related health inequalities.

Keywords: Hispanic, Latino, Socioeconomic status, Stress

Stress is posited as a key psychosocial conduit through which low socioeconomic status (SES) fosters health risks (Adler & Snibbe, 2003; Baum et al., 1999; Brunner, 1997; Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Myers, 2009; Thoits, 2010). This perspective is based on evidence linking low SES with psychological markers of stress (Thoits, 2010) and, in turn, connecting stress with physical health conditions that show marked SES disparities (e.g., cardiovascular disease, CVD; type 2 diabetes mellitus) (Dimsdale, 2008; Pouwer et al., 2010). To date, research addressing stress as a pathway in health disparities has mainly examined self-reported mental health symptoms or subjective physical health outcomes (Kosteniuk & Dickinson, 2003; Turner & Avison, 2003; Turner & Lloyd, 1999). However, overlapping conceptual and measurement variance between stress and these outcomes, or third variable effects (e.g., negative affect), could compromise accurate quantification of the role of stress in these analyses. In a recent review of research concerning SES and objective physical health outcomes, five of nine studies did not identify a mediating role of stress, and several found no relationship or a positive relationship between SES and stress (for details, see Matthews et al., 2010).

In part, these inconsistent findings may reflect the complex and multidimensional nature of the stress construct and differences in self-report measures examined (Cohen et al., 1995; Monroe, 2008). Conceptualizations of self-reported stress differ according to whether they focus on demanding environmental events or on the individual’s responses to these events (e.g., perceived stress measures; Cohen et al., 1995). The latter approach emphasizes individual differences in stress appraisals as well as available resources and ability to manage stress. At a more specific level, stress measures vary along dimensions of time (e.g., discrete versus chronic events) and severity (e.g., trauma versus daily hassles). Self-reports may be retrospective and aggregate in nature, or they may provide a momentary snapshot of stress in daily life. In vivo assessments of stress can help reduce recall biases and the influence of extraneous situational factors or recent events on self-reports (Kamarck et al., 2011). Despite these complexities, the majority of studies examined in the aforementioned review (Matthews et al., 2010) employed a single self-report measure of stress, sometimes consisting of only one or a few items. Further, the strongest support for a mediating role of stress in SES-physical health associations came from a study that incorporated an array of stress measures administered at two time points during an 8 year follow-up period (Lantz et al., 2005). Thus, the contribution of stress to SES-related disparities in morbidity and mortality may be underestimated in many studies due to limitations inherent to the measures used and their administration at only a single time-point (Thoits, 2010; Turner, 2010).

Another important issue that has received minimal consideration is the extent to which the relationship between SES and stress, or the role of stress in SES-health disparities, may vary across sociodemographic groups. Stress exposure and perceptions are socially patterned not only by SES, but also by ethnicity and gender (Myers, 2009; Thoits, 2010; Turner & Avison, 2003), with ethnic minorities and women typically reporting higher levels of stress than non-Latino Whites and men, respectively. Importantly, to date, most of the research concerning ethnicity and stress exposure has focused on non-Latino White and Black populations. Less is known about levels of stress and their health implications in Latinos, the largest and fastest growing US ethnic minority group (Passel et al., 2011).

As a group, Latinos face many risk factors and barriers to optimal health, yet paradoxically show lower rates of mortality (Arias et al., 2010) and some types of morbidity (e.g., CVD; Roger et al., 2011) relative to non-Latino Whites. Foreign-born Latinos also display health advantages relative to US-born Latinos (Argeseanu Cunningham et al., 2008), although these benefits deteriorate with longer duration of US residence (Cho et al., 2004; Eschbach et al., 2007). The available research concerning SES-health associations in Latinos is limited, but some studies also suggest that SES (especially education) effects are less consistent in Latinos than in non-Latino Whites (Braveman et al., 2010; Goldman et al., 2006; Karlamangla et al., 2010; Kimbro et al., 2008; Turra & Goldman, 2007). In particular, immigrant and less acculturated Latino subgroups appear to display attenuated SES gradients in physical health risks and outcomes in some studies (e.g., Gallo et al., 2009a; Kimbro et al., 2008). However, these patterns are complex, and further differences arise according to gender (Karlamangla et al., 2010). There is also substantial variability in health among Latino national origins subgroups, which has led to criticism of studies that consider Latinos as a single, pan-ethnic grouping (Zsembik & Fennell, 2005).

Among varied explanations for such patterns, resilient culturally-driven behavioral or psychosocial processes have been proposed to play a role in better than expected health outcomes and apparent resilience to effects of low SES observed in Latinos (Escarce et al., 2006; Gallo et al., 2009b). For example, the traditional Latino cultural milieu may offer social resources that buffer against stress or its mental and physical health effects. Indeed, despite increased exposure to social stressors such as immigration and poverty, foreign-born and less US-acculturated Latinos have been found to report fewer stressful life events and less exposure to discrimination, when compared with US-born or more acculturated Latinos (Tillman & Weiss, 2009; Turner et al., 2006). Furthermore, increased exposure to stress is postulated as a factor contributing to worse health in more US-acculturated Latinos (Markides & Eschbach, 2011). To our knowledge, no prior study has explored associations between SES and stress in Latinos.

The current study sought to examine the association between SES and stress in a probability sample of Mexican–American women from socioeconomically diverse communities in South San Diego. Prior studies in this cohort have shown that higher SES related to lower levels on variables comprising the metabolic syndrome, and that psychosocial risk (i.e., negative emotions and cognitions) and resource variables (e.g., social support, optimism) contributed to these associations (Gallo et al., 2011a). However, as in prior research, the gradient pattern (and its explanation by psychosocial factors) was observed more consistently in more, compared with less US-acculturated women (Gallo et al., 2011a). Women with higher SES also showed lower levels on inflammatory CVD risk markers, and this relationship was partially explained by obesity and related behavioral factors (Gallo et al., 2012). Thus, prior studies demonstrate the health-relevance of SES in this cohort, and suggest possible variability according to acculturation levels. In the current study, we emphasize the SES-stress link without incorporating a physical health endpoint, to allow more detailed examination of the complexity of associations across different types and domains of stress.

In particular, our study incorporated a multi-dimensional assessment approach with measures of stressful life events (over the past year), chronic stress in important life domains, perceived stress, and a two-day ecological momentary assessment of stress experiences in everyday life. Although the general hypothesis was that SES and stress would be inversely related, we predicted that the relative strength of associations would differ across stress types. Research on which to base these predictions is limited, but we anticipated that the association between SES and perceived stress would be relatively stronger, compared to associations with other measures, given that such conceptualizations incorporate perceptions not only of stress exposure, but also of available resources. According to several relevant theoretical frameworks (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Myers, 2009), both of these factors are shaped by SES and contribute to health disparities. Since prior research in this and other Latino samples suggests that the nature of SES-health gradients may differ by acculturation, and given the hypothesized role of psychosocial resilience in buffering SES-health gradients in less acculturated Latinos, sensitivity analyses also examined the stability of SES gradients in stress across acculturation levels. Specifically, we hypothesized that SES-stress associations would be attenuated in women who were less acculturated to the mainstream US culture.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

As previously described (Gallo et al. 2011a, b), participants were randomly recruited via targeted telephone and mail procedures from South San Diego communities with high densities of Mexican–American residents and a wide range of SES. Women who were 40–65 years of age, of Mexican descent, able to read and write in English or Spanish, and free of major health conditions (e.g., heart disease, cancer) were eligible. Six hundred and fifty-six women were screened, 365 (55.6 %) were eligible, and 323 (88 % of those eligible) participated in some or all parts of the study. The current study included 318 women who completed at least one measure of SES and the psychosocial assessments.

Procedures

Trained bilingual research assistants collected data in two home visits. At the first visit, participants provided written informed consent and completed assessments in their preferred language. During the second visit, participants were provided with a Palm handheld computer (Palm, Inc., Sunnyvale, CA) programmed with a 31-item diary, which they completed at approximately 30-min intervals during wake-time hours across 2 days. Diary items assessed situational factors and momentary levels of stress, emotions, and social experiences. Procedures were approved by San Diego State University and University of California, San Diego’s Institutional Review Boards.

Measures

Socioeconomic status (SES)

Educational attainment and monthly household income represented SES. Educational attainment was grouped into six categories: 0–8th grade, some high school (no diploma), high school graduate, some college, 4 year college degree, graduate or professional degree. Total monthly household income was represented as: < $1,000, $1,000–$1,999, $2,000–$2,999, $3,000–$3,999, $4,000–$5,999, ≥$6,000.

Acculturation

The Adult English Proficiency, Adult Pattern of English versus Spanish Language Usage, and Child Language Experiences subscales from the Hazuda Acculturation and Assimilation Scales (Hazuda et al., 1988) assessed acculturation. The scales were developed and validated in a population-based sample of Mexican–American adults aged 25–64 years (Hazuda et al., 1988). They are available in English and Spanish and have been shown to be internally consistent (α = 0.85–0.95; Haffner et al., 1994). In the current study, a principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation showed that the scales represented a single latent construct with high factor loadings for each indicator (0.75–0.93). Thus, a regression-based factor score was used, with higher values indicating greater US-acculturation.

Stress measures

The study used measures that have been administered previously in research involving multi-ethnic or Latino samples, and that have demonstrated predictive utility and adequate psychometric properties. Unless otherwise specified, the measures were translated for the current study using forward and back translation procedures, with reconciliation by committee, to ensure conceptual and linguistic equivalence across versions.

Life events stress

A modified version of the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Inventory Life Events Scale (Dohrenwend, 1981; Dohrenwend et al., 1978) assessed life events stress. The 34-item scale was developed to assess events relevant to an ethnically diverse, national midlife female cohort that included Latinas (Avis et al., 2003; Bromberger et al., 2004). Participants were assigned one point for each event they endorsed as occurring in the previous 12 months that they viewed as somewhat or very upsetting.

Chronic stress

Participants completed a measure of ongoing or chronic stress in eight major life domains (e.g., work, relationships, caregiving) developed for the same national women’s study (Bromberger & Matthews, 1996). Women were assigned one point for chronic stress in a given domain of at least 12-months duration that they rated as somewhat or very upsetting. A count score was derived to indicate total chronic stress burden and individual domains were also examined, as in prior studies (Gallo et al., 2011b; Shivpuri et al., 2011).

Perceived stress

The 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen & Williamson, 1988) measured generalized stress appraisals in the past month. This scale has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .72; Cohen et al., 1983), similar to the 10-item measure (α = .76; Cohen & Williamson, 1988). The PSS was translated into Spanish for a Mexican sample by the MAPI Research Institute (MAPI Institute, Lyon, France) using a multi-step approach to ensure linguistic and conceptual validity (Acquadro et al., 1996). Internal consistency for the 4-item version in the current sample was relatively low at α = .61. However, as noted in classic articles concerning coefficient alpha, internal consistency is necessarily truncated when few items comprise a scale (Henson, 2001), and even low alpha values do not seriously attenuate regression coefficients (Schmitt, 1996). Item-level multi-group confirmatory factor analyses supported the metric invariance of the scale across language versions.

Momentary stress experiences

A diary measure of stress in everyday life was completed by 301 participants; however, 15 women who completed < 50 % of the required diary entries were excluded from these analyses, for a sample size of N = 286. Participants completed an average of 51 entries (range = 29–69) across 2 days. Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) version 6.08 (Scientific Software International, Lincolnwood, IL), was used to obtain mean values across all time points for each item, for each individual. Participants indicated on a 3-point scale whether they felt “difficulties were piling up”, “overloaded”, and “in control”. These items were chosen, as they were similar to concepts included on the PSS. However, a PCA with varimax rotation revealed a two-factor structure, with the “difficulties” and “overloaded” items loading strongly on one factor (both loadings 0.92), and the reverse-coded “in control” having a low factor loading (0.24). Consequently, “difficulties” and “overloaded” were standardized and summed to represent momentary perceived “demands” while the reverse-coded “in control” was used to represent momentary “low control”. Item-level multi-group confirmatory factor analyses supported the metric invariance of the scales across versions.

Data analyses

Age-adjusted associations of SES with stress variables were examined using multivariate linear regression analyses performed in MPlus version 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). All continuous predictors were standardized and correlations among the five stress variables were specified. To account for correlations among the stress variables jointly, it was necessary to treat all stress variables as continuous. Life events and overall chronic stress variables (which represent “count” scores) were continuously distributed, but did evidence non-normality; thus, analyses applied a maximum likelihood estimation procedure that is robust to non-normality. Multivariate probit regression, which utilizes the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution and allows for the joint estimation of correlations among outcomes, was used to investigate similar predictive models for variables representing chronic stress domains. A weighted least squares estimation procedure was used for these models. Income and education were examined in separate models, since their psychosocial implications may differ. Sensitivity analyses evaluated multiplicative interaction effects between SES indicators and acculturation, in models that included their corresponding main effects. We used p < .05 (2-tailed) to indicate statistical significance for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive analyses and bivariate associations

Table 1 displays depscriptive statistics for all variables. Participants’ average age was 49.79 years (SD = 6.55). The sample was socioeconomically diverse; ~24 % of women reported a monthly income of less than $2,000, and ~54 % attended at least some college. Correlations among primary stress variables (data not shown) were positive and statistically significant (rs = 0.13–0.57, all ps < .05), with the exception of associations of low control in daily life with chronic and life events stress (ps >.10). Among chronic stress domains (data not shown), several correlations were non-significant; significant correlations were positive and small to moderate in magnitude (rs = 0.12–0.42, ps < .05). Excepting a positive association with chronic caregiving stress (r = 0.13, p < .05), age did not relate significantly to stress (ps > .05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for all study variables

| Variable | Scale range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) [M (SD)] | 49.79 (6.55) | |

| Monthly incomea [N (%)] | ||

| < $2,000 | 76 (24.36) | |

| $2,000–$3,999 | 108 (34.62) | |

| ≥$4,000 | 128 (41.02) | |

| Educationa [N (%)] | ||

| ≤8th grade | 52 (16.35) | |

| Some high school/GED/High school diploma | 95 (29.87) | |

| Some college/college degree | 171 (53.77) | |

| Acculturationb [M (SD)] | ||

| Hazuda adult english proficiency | 3.03 (0.90) | 1–4 |

| Hazuda adult language pattern | 2.27 (0.98) | 1–4 |

| Hazuda child language experiences | 1.37 (0.88) | 1–4 |

| Measures of stress [M (SD)] | ||

| Life events stressc | 4.17 (3.33) | 0–34 |

| Chronic stress burdenc | 1.78 (1.80) | 0–8 |

| Chronic stress domains [N (%)] | ||

| Personal health-related stress | 32 (10.06) | |

| Family health-related stress | 101 (31.76) | |

| Family drug/alcohol-related stress | 65 (20.50) | |

| Work stress | 53 (16.67) | |

| Financial stress | 106 (33.33) | |

| Housing-related stress | 40 (12.58) | |

| Caregiving stress | 70 (22.08) | |

| Relationship stress | 72 (22.64) | |

| Perceived stress | 5.55 (1.52) | 4–12 |

| Momentary stress—demands | 2.40 (0.44) | 0–3 |

| Momentary stress—low control | 1.81 (0.46) | 0–3 |

Three categories presented for brevity,

Scales presented for descriptive purposes, component score used in analyses,

Sum of somewhat and very upsetting events or stressors

Multivariate regression analyses

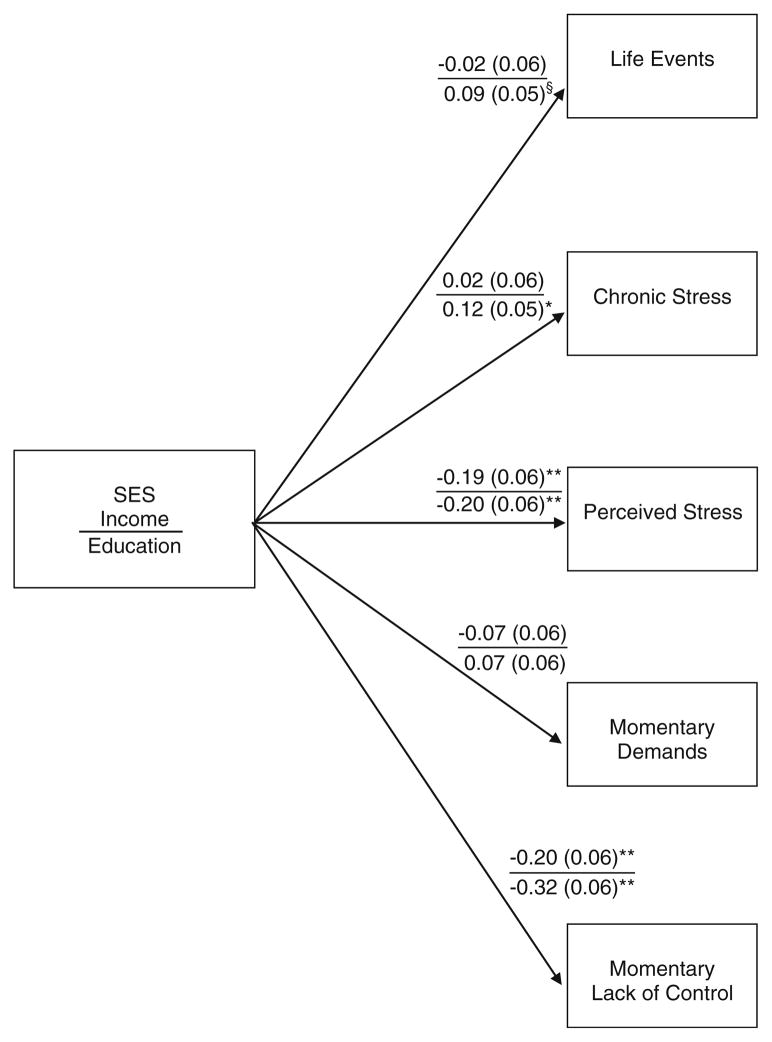

As depicted in Fig. 1, higher income and education related to lower levels of perceived stress (both R2 = 0.04) and fewer daily experiences of low control (R2 = 0.04 and 0.10, respectively). However, contrary to predictions, women with greater education also reported a greater total burden of chronic stressors (R2 = 0.01). Neither SES variable related to past year life events or perceived demands in daily life.

Fig. 1.

Results of multivariate linear regression analyses (age-adjusted) regressing life events, total chronic stress burden, perceived stress, and perceived demands and control in daily life on income and education (examined in separate models). Standardized regression coefficients are depicted, with standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05; **p < .01; §p < .10

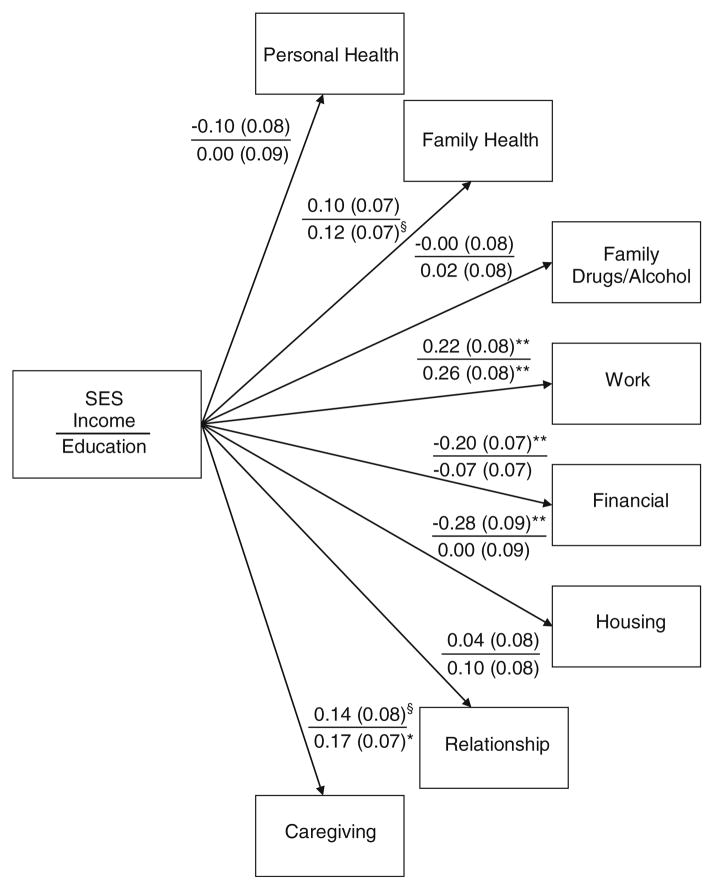

Analyses of individual chronic stress domains (Fig. 2) indicated that higher income related to a decreased likelihood of financial (R2 = 0.04) and housing-related stress (R2 = 0.08). However, contrary to predictions, greater income and education also predicted an increased likelihood of chronic work stress (R2 = 0.05 and 0.07, respectively), and higher educational attainment predicted a greater likelihood of chronic caregiving stress (R2 = 0.03).

Fig. 2.

Results of multivariate probit regression analyses (age-adjusted) regressing chronic stress domains on income and education (examined in separate models). Standardized regression coefficients are depicted, with standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05; **p < .01; §p < .10

Sensitivity analyses

SES by acculturation interaction effects were explored for all analyses and showed that acculturation moderated the association between income and health-related (β = −0.12, SE = 0.06, p < .05) and housing-related chronic stress (β = −0.19, SE = 0.09, p < .05). Simple slopes analyses revealed that higher income was associated with a lower likelihood of health-related chronic stress at high acculturation (i.e., 1 SD above the sample mean; β = −0.33, SE = 0.16, p = .05) but not low (i.e., 1 SD below the mean) or moderate (i.e. mean) acculturation levels (both ps > .05). Similarly, higher income related to a lower likelihood of housing stress among individuals with high (β = −0.51, SE = 0.19, p < .01) and moderate (β = −0.33, SE = 0.11, p < .01) but not low acculturation (p > .05). Thus, for these two outcomes only, the hypothesized pattern of an inverse gradient between SES and stress was found only at higher acculturation levels.

Discussion

In a randomly selected cohort of Mexican–American middle-aged women, associations of SES with stress varied in direction and strength across SES and stress indicators, and were generally small to moderate in magnitude. Women with higher SES (income and education) endorsed lower perceived stress and greater control in everyday life, but those with higher educational attainment also experienced a greater burden of chronic stress. For domain-specific chronic stressors, higher income related to a lower likelihood of chronic financial and housing stress, but women with higher income or education were more likely to report chronic work and caregiving stress (for income, association with caregiving stress approached significance at p < .10). Notably, in other research conducted in this cohort, women experiencing chronic caregiving, work, or financial stress evidenced elevated allostatic load (Gallo et al., 2011b)—a marker of physiological dysregulation across multiple systems that has predicted greater morbidity and mortality risk in other studies (Karlamangla et al., 2002; Seeman et al., 2001)—relative to women who did not experience these stressors. Overall, the observed pattern of SES-stress associations provides a mixed picture of future health risks in our cohort of Mexican–American women.

Consistent with the stress process model, many prior studies have found that higher SES relates to lower stress (Thoits, 2010; Turner, 2010), but there are notable exceptions. For example, other studies have failed to identify an association between indicators of SES and past year life events (Turner & Avison, 2003). In addition, higher occupational status was related to increased perceived stress in a study of Scottish men (Macleod et al., 2005), and education was unassociated with perceived stress (Gallo et al., 2001), life events, or chronic stressors experienced in the past 6 months (Matthews et al., 2008) in a probability sample of mostly non-Latino white middle-aged women. Studies of SES and stress in everyday life have been limited, but another study found that higher education was related to greater experiences of control, but not to lower perceived demands in everyday life, in mostly non-Latino white middle-aged women (Gallo et al., 2005). In a national, middle-aged sample, lower education predicted fewer (Grzywacz et al., 2004), but more severe, daily hassles (Almeida et al., 2005) across a 1-week diary study.

Thus, the current findings add to a small but growing body of research suggesting that the association between SES and stress may not be as straightforward as anecdotally portrayed, and this may help explain the inconsistent empirical findings in studies concerning stress as a pathway in SES-physical health associations (Matthews et al., 2010). A number of factors may contribute to such inconsistencies, including inaccuracies introduced by respondents’ use of heuristic strategies, strong emotions, or recent salient experiences that affect global stress appraisals (Kamarck et al., 2011; Stone et al., 1998), as well as differences in “stress” interpretations by SES. For example, due to repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage, individuals with low SES may habituate to stress over time (Nguyen & Peschard, 2003). Commonly used simplistic and single-item measures may be particularly prone to such biases and interpretive influences. Moreover, the most consistent findings in the current study were for associations of SES with measures tapping stress and ability or resources to control it (i.e., momentary perceptions of control, perceived stress). Importantly, there may also be SES-related differences in the function or interpretation of control experiences. Specifically, recent research suggests that individuals in lower social classes may place less value on certain control experiences, such as choice and individualism, relative to their higher SES counterparts (Markus & Schwartz, 2010; Stephens et al., 2007). Nonetheless, research showing that perceptions of control account for a significant amount of variance in SES-gradients for health outcomes including CVD (Bosma et al., 2005) and all-cause mortality (Bosma et al., 1999) suggest that although control experiences may differ, greater control can enhance health across socioeconomic strata.

The sociodemographic context of the current study should also be considered in interpreting the current findings and their implications for future research examining associations among SES, stress, and physical health. Specifically, these relationships may vary by gender, race/ethnicity, or social and cultural factors. For example, in women, higher SES may intensify exposure to, or distress associated with, certain types of stress (i.e., work or care-giving stress), as women navigate male-oriented professional contexts, or attempt to juggle multiple social roles, even as other types of stress (e.g., financial, housing) are mitigated. These kinds of nuanced associations would be masked in studies that evaluate global stress assessments and/or that collapse across gender groups. Moreover, in the more traditional gender-role context of the Latino culture (Kane, 2000), women of greater educational and occupational status may encounter social pressures related to their “non-traditional” choices (e.g., occupations that require long hours, delayed parenting), or they may experience increased work-family role conflict (i.e., stress that arises when obligations from one role interfere with those of the other role). National survey data suggest that Latinos report more work-family conflict than non-Latino Whites, and that Latinas report substantially greater conflict than their male counterparts (Roehling et al., 2005). A smaller study of Mexican immigrant non-skilled workers found low levels of work-family conflict overall, but higher levels in women than in men (Grzywacz et al., 2007). Family and gender-role patterns in Mexican households are affected by many factors including national origins, immigration experiences, and generation (Landale et al., 2006; Parrado & Flippen, 2005; Su et al., 2010). Nonetheless, Latinas—particularly those of higher SES—may be challenged by dual home and work experiences relative to their male counterparts, and this may help explain their increased chronic stress, especially in the areas of caregiving and work, in the current study.

Sensitivity analyses suggested that for the most part, associations of SES and stress were consistent across levels of acculturation. Only two interaction effects emerged, and suggested that higher SES was associated with lower housing related and personal health related stress only in women who were relatively more US acculturated. These findings should be interpreted with caution given the small number of significant effects relative to the number of interaction effects tested, but they are generally consistent with research suggesting that SES-health gradients may be mitigated in less acculturated Latinos (Gallo et al., 2009a; Kimbro et al., 2008). Exploring main effects of acculturation in relation to stress was beyond the scope of the current manuscript, and is an important direction for future research. However, it should be noted that disentangling the effects of SES versus acculturation in relation to stress is extremely difficult given the close relationship between these variables in Latinos.

The current study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting findings. First, despite inclusion of multiple assessment methods, all relied on self-report. A self-report approach is consistent with prior studies that have attempted to establish stress as a link in the association between SES and physical health (Matthews et al., 2010), and therefore was considered most germane to the current research questions. However, a more complete accounting of associations between SES and stress could be achieved with the addition of interview, peer ratings, or biological methods. Additionally, since associations between SES and health in Latinos are inconsistent and vary by acculturation level and gender, findings cannot be assumed to generalize to other Latino subgroups. Finally, conclusions should be interpreted in the context of the number of statistical comparisons made, since no family-wise alpha level correction was imposed.

In sum, findings from the current study and from prior research (Matthews & Gallo, 2011; Matthews et al., 2010) suggest that it may be overly simplistic to view low SES as a marker of elevated stress exposure. Researchers are urged to undertake a multi-dimensional approach to stress assessment, to consider that SES may show divergent associations with stress depending on stress type and domain, and to attend to sociodemographic differences in interpreting associations between SES and stress and considering the role of stress in SES related health disparities. Finally, given evidence that psychosocial resources such as control perceptions may form a salient pathway in the link between SES and health (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Myers, 2009), studies that consider resources in addition to stress may provide greater insight into psychosocial processes involved in SES gradients in health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Linda C. Gallo, Email: lcgallo@sciences.sdsu.edu, Department of Psychology, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA. SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

Smriti Shivpuri, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA.

Patricia Gonzalez, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA.

Addie L. Fortmann, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

Karla Espinosa de los Monteros, SDSU/UCSD Joint Doctoral Program in Clinical Psychology, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA.

Scott C. Roesch, Department of Psychology, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 105, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

Gregory A. Talavera, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 9245 Sky Park Court Suite 110, San Diego, CA 92123, USA

Karen A. Matthews, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA

References

- Acquadro C, Jambon B, Ellis D, Marquis P. Language and translation issues. In: Spiker B, editor. Quality of life and pharamcoeconomics in clinical trials. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 575–585. [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Snibbe AC. The role of psychosocial processes in explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Neupert SD, Banks SR, Serido J. Do daily stress processes account for socioeconomic health disparities? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60(2):34–39. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argeseanu Cunningham S, Ruben JD, Venkat Narayan KM. Health of foreign-born people in the United States: A review. Health & Place. 2008;14:623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias E, Eschbach K, Schauman WS, Backlund EL, Sorlie PD. The Hispanic mortality advantage and ethnic misclassification on US death certificates. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:S171–S177. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avis NE, Ory M, Matthews KA, Schocken M, Bromberger J, Colvin A. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of middle-aged women: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Medical Care. 2003;41:1262–1276. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093479.39115.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A, Garofalo JP, Yali AM. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress. Does stress account for SES effects on health? In: Adler NE, Marmot M, Stewart J, McEwen B, editors. Socioeconomic status and health in industrial nations: Social, psychological, and biological pathways. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 896. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 1999. pp. 131–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma H, Schrijvers C, Mackenbach JP. Socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and importance of perceived control: Cohort study. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:1469–1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma H, Van Jaarsveld CH, Tuinstra J, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV, Van Eijk JT, et al. Low control beliefs, classical coronary risk factors, and socio-economic differences in heart disease in older persons. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Harlow S, Avis N, Kravitz HM, Cordal A. Racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of depressive symptoms among middle-aged women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:1378–1385. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. A “feminine” model of vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal investigation of middle-aged women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:591–598. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner E. Stress and the biology of inequality. British Medical Journal. 1997;314:1472–1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Frisbie WP, Hummer RA, Rogers RG. Nativity, duration of residence, and the health of Hispanic adults in the United States. International Migration Review. 2004;38:184–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson GM. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dimsdale JE. Psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B. Life stress and illness: Formulation of the issues. New York: Prodist; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenasy AR, Dohrenwend BP. Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: The PERI Life Events Scale. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escarce JJ, Morales LS, Rumbaut RG. The health status and health behaviors of Hispanics. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. pp. 362–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschbach K, Stimpson JP, Kuo YF, Goodwin JS. Mortality of foreign-born and US-born Hispanic adults at younger ages: A reexamination of recent patterns. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1297–1304. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Bogart LM, Vranceanu AM. Socioeconomic status, resources, psychological experiences, and emotional responses: A test of the Reserve Capacity Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:386–399. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Espinosa De Los Monteros K, Allison M, Diez-Roux AV, Polak JF, Morales LS. Do socioeconomic gradients in subclinical atherosclerosis vary according to acculturation level? Analyses of Mexican-Americans in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2009a;71:756–762. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b0d2b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, Espinosa De Los Monteros K, Mills PJ, Barrett-Connor E, Roesch SC, et al. Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and inflammation in Mexican-American women: What is the role of obesity? Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f5f6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Fortmann AL, Roesch SC, Barrett-Connor E, Elder JP, Espinosa De Los Monteros, et al. Socioeconomic status, psychosocial resources and risk, and cardiometabolic risk in Mexican-American women. Health Psychology. 2011a doi: 10.1037/a0025689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Jimenez JA, Shivpuri S, Espinosa De Los Monteros K, Mills PJ. Domains of chronic stress, lifestyle factors, and allostatic load in middle-aged mexican-american women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2011b;41:21–31. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Matthews KA, Kuller LH, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Edmundowicz D. Educational attainment and coronary and aortic calcification in postmenopausal women. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001;63:925–935. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa De Los Monteros K, Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality. 2009b;77:1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman N, Kimbro RT, Turra CM, Pebley AR. Socioeconomic gradients in health for white and Mexican-origin populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:2186–2193. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Almeida DM, Neupert SD, Ettner SL. Socioeconomic status and health: A micro-level analysis of exposure and vulnerability to daily stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2004;45:1–16. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Marin A, Carrillo L, Burke B, Coates ML, et al. Work-family conflict: Experiences and health implications among immigrant Latinos. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92:1119–1130. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner S, Gonzalez Villalpando C, Hazuda HP, Valdez R, Mykkanen L, Stern M. Prevalence of hypertension in Mexico City and San Antonio, Texas. Circulation. 1994;90:1542–1549. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazuda HP, Stern MP, Haffner SM. Acculturation and assimilation among Mexican Americans: Scales and population-based data. Social Science Quarterly. 1988;69:687–706. [Google Scholar]

- Henson RK. Understanding internal consistency reliability estimates: A conceptual primer on coefficient alpha. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2001;34:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarck TW, Shiffman S, Wethington E. Measuring psychosocial stress using ecological momentary assessment methods. In: Baum Contrada., editor. The handbook of stress science: Biology, psychology, and health. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 2011. pp. 597–617. [Google Scholar]

- Kane EW. Racial and ethnic variations in gender-related attitudes. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in cardiovascular risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Annals of Epidemiology. 2010;20:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Singer BH, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Seeman TE. Allostatic load as a predictor of functional decline. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2002;55:696–710. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbro RT, Bzostek S, Goldman N, Rodriguez G. Race, ethnicity, and the education gradient in health. Health Affairs. 2008;27:361–372. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosteniuk JG, Dickinson HD. Tracing the social gradient in the health of Canadians: Primary and secondary determinants. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00345-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Bradatan C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the future of America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. pp. 138–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, House JS, Mero RP, Williams DR. Stress, life events, and socioeconomic disparities in health: Results from the Americans’ Changing Lives Study. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:274–288. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod J, Davey SG, Metcalfe C, Hart C. Is subjective social status a more important determinant of health than objective social status? Evidence from a prospective observational study of Scottish men. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:1916–1929. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Eschbach K. Hispanic paradox in adult mortality in the United States. In: Rogers RG, Crimmins EM, editors. International handbook of adult mortality. Vol. 2. Springer; Netherlands: 2011. pp. 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Schwartz B. Does choice mean freedom and well-being? Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Gallo LC. Psychological perspectives on pathways linking socioeconomic status and physical health. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:501–530. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Taylor SE. Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:146–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Räikkönen K, Gallo LC, Kuller LH. Association between socioeconomic status and metabolic syndrome in women: Testing the Reserve Capacity Model. Health Psychology. 2008;27:576–583. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM. Modern approaches to conceptualizing and measuring human life stress. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:33–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative conceptual model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VK, Peschard K. Anthropology, inequality, and disease: A review. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2003;32:447–474. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Flippen CA. Migration and gender among Mexican Women. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:606–632. [Google Scholar]

- Passel JS, Cohn DV, Lopez MH. Census 2010: 50 Million Latinos (Pew Hispanic Center report) Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pouwer F, Kupper N, Adriaanse MC. Does emotional stress cause type 2 diabetes mellitus? A review from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research Consortium. Discovery Medicine. 2010;9(45):112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehling PV, Jarvis LH, Swope HE. Variations in negative work-family spillover among White, Black, and Hispanic American men and women. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:840–865. [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:4770–4775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081072698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivpuri S, Gallo L, Crouse J, Allison M. The association between chronic stress type and C-reactive protein in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: does gender make a difference? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens NM, Markus HR, Townsend SS. Choice as an act of meaning: The case of social class. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:814–830. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Schwartz JE, Neale JM, Shiffman S, Marco CA, Hickcox M, et al. A comparison of coping assessed by ecological momentary assessment and retrospective recall. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1670–1680. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D, Richardson C, Wang G. Assessing cultural assimilation of Mexican Americans: How rapidly do their gender-role attitudes converge to the U.S. mainstream? Social Science Quarterly. 2010;91:762–776. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman KH, Weiss UK. Nativity status and depressive symptoms among Hispanic young adults: The role of stress exposure. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90:1228–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. Understanding health disparities: The promise of the stress process model. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, Wheaton B, editors. Advances in the conceptualization and study of the stress process: Essays in honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Avison WR. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:488–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. The stress process and the social distribution of depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:374–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA, Taylor J. Stress burden, drug dependence and the nativity paradox among U.S. Hispanics. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turra CM, Goldman N. Socioeconomic differences in mortality among U.S. adults: Insights into the Hispanic Paradox. The Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62B:S184–S192. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.3.s184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsembik BA, Fennell D. Ethnic variation in health and the determinants of health among Latinos. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]