Abstract

In spite of the fact that a surgical procedure may have been performed for the appropriate indication and in a technically perfect manner, patients are threatened by perioperative organ injury. For example, stroke, myocardial infarction, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, or acute gut injury are among the most common causes for morbidity and mortality in surgical patients. In the present review, we discuss the pathogenesis of perioperative organ injury, and provide select examples for novel treatment concepts that have emerged over the past decade. Indeed, we believe that research to provide mechanistic insight into acute organ injury and to identify novel therapeutic approaches for the prevention or treatment of perioperative organ injury represents the most important opportunity to improve outcomes of anesthesia and surgery.

Introduction

If perioperative death would constitute its own category in the annual mortality tables from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, it would represent a leading cause of death in the United States. Although substantial advancements in anesthesia safety have been made over the past 50 years, similarly improved outcomes throughout the perioperative period have not been achieved.1 Regardless of many advances in the care we provide, acute organ injury leading to single or multiple organ failure remains the leading precursor to death following surgery.2 Inpatient mortality in the setting of postoperative critical illness is as high as 20.6% and occurs secondary to multiple organ dysfunction in 47%–53% of cases.2,3 While severe sepsis is the typical precurser to multiple organ dysfunction, systemic inflammatory response syndrome is a common trigger in surgical patients.4 The purpose of this review is to discuss some of the more frequent causes of acute organ injury in context with their clinical relevance and pathophysiologic mechanisms. To highlight the enormous potential for anesthesiologists to impact outcomes of surgical patients, we present recent, exemplary findings that have improved our understanding of acute organ injury and could lead to successful therapeutic strategies.

Patient risk for adverse events in the context of anesthesia has steadily decreased over the last 60 years. In a study of 599,548 patients from 1948–52, Henry Beecher reported that the anesthesia-related death rate was 1 in 1560 anesthetics.5 Recent studies report much lower incidences of death thought to be related to anesthesia: in the United States, 8.2 deaths per million surgical hospital discharges6, in Japan, 21 deaths per million surgeries7, and in a global meta-analysis, 34 deaths per million surgeries were attributed to the anesthetic.8 These data may lead some to conclude that the technological and pharmacological advances in the delivery of anesthesia care have made surgery relatively safe.

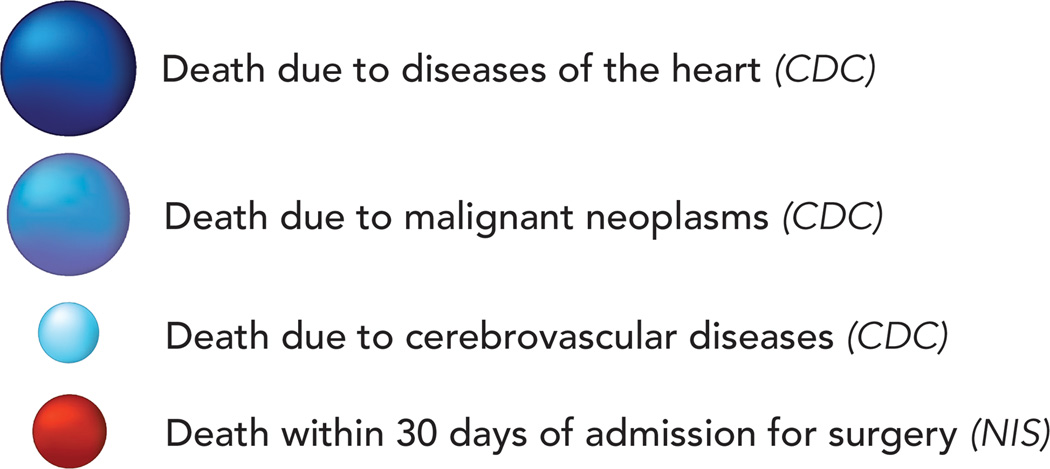

When all-cause perioperative mortality is assessed, current studies in fact report much poorer outcomes. And, the perceived improvements in surgical care appear to be modest at best. In a Dutch study of 3.7 million patients who underwent surgical procedures between 1991 and 2005, perioperative death prior to discharge or within 30 days following elective open surgery occurred at a rate of 1.85%.9 Gawande reported a 30-day death rate of 1.32% in a United States based inpatient surgical population for the year 2006.10 This translates to 189,690 deaths in 14.3 million admitted surgical patients in one year in the United States alone. For the same year, only 2 categories reported by the Center for Disease Control - heart disease and cancer - caused more deaths in the general population (Figure 1). Cerebrovascular disease, the third most common cause of death, was responsible for 137,119 deaths.* Thus, all-cause perioperative death occurs more frequently than stroke in the general population, further emphasizing the potential impact of improved perioperative organ protection.

Figure 1. Magnitude of perioperative mortality.

The 3 leading causes of death in the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) annual death table for the United States in 2006 were: #1. Diseases of heart (n=631,636), #2. Malignant neoplasms (n=559,888), and #3. Cerebrovascular diseases (n=137,119).* Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) for the same year, Gawande and colleagues reported 189,690 deaths within 30 days of admission for inpatients having a surgical procedure.10 In magnitude, all-cause 30-day inpatient mortality following surgery approximated the third leading cause of death in the United States.

Even though the rate of anesthesia-related deaths has dramatically declined over the past 60 years, perioperative mortality has not. In a 2007 editorial, Evers and Miller challenged us to take on the charge of “dramatically improving perioperative outcomes.”1 Although a herculean task, we have immense opportunities for advancing patient care through improved pre-, intra-, and postoperative medicine. Anesthesiologists have a unique chance to pre-empt insults through pharmacological and interventional therapy. Preventing organ injury has the potential to avoid the need for postoperative escalation of care, which is not only costly, but also associated with decreased health-related quality of life up to 6 years following admission to a surgical intensive care unit.11 To exemplify promising areas of ongoing and future research in acute organ injury, we have summarized new findings for 5 select pathologies - stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), acute kidney injury (AKI), and acute gut injury (AGI). We present newly identified mechanisms of injury in the context of past, current, and emerging therapeutic strategies. While our selection of findings is not intended to be complete or exclusive, we chose to present innovative approaches that can serve as examples of how research aimed at impacting common hypoxic and inflammatory pathways has the potential to advance perioperative medicine. Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of acute organ injury and multiple organ failure is imperative or conditio sine qua non for the design of innovative and successful interventions that will help us reach our ultimate goal: Improving outcomes for surgical patients.

Stroke

The World Health Organization has defined stroke as “rapidly developed clinical signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 h or until death, with no apparent non-vascular cause.”12 The clinical diagnosis of perioperative stroke is often delayed because the mental status of patients can be impaired by sedative or analgesic drugs, and motor or sensory function can be limited by the nature of an operation. In recent studies, the incidence of stroke in non-cardiac and non-neurologic surgery is 0.1%–0.7%.13–15 Higher risk procedures, such as coronary artery bypass surgery and cardiac valve surgery, are complicated by stroke in 1.6%16 and 2.2%17 of cases respectively. Mortality in patients who suffer from perioperative stroke is significantly elevated and ranges from 12%–32.6%.13,14,18

Rupture of a blood vessel leading to hemorrhagic stroke is rare following surgery. Most strokes are due to acute occlusion of a blood vessel, and thus are ischemic in nature.19 Blockage can develop from local arterial thrombosis or from embolization of material originating in the heart or the vasculature. Vascular sources commonly include proximal large arteries, such as the internal carotid or the aorta. Paradoxical embolization from a venous source can cause stroke, if a right-to-left cardiac shunt permits direct passage from the venous circulation to the brain.20 Watershed infarcts occur in the distal perfusion territories of cerebral arteries and can be due to hypo-perfusion and concurrent microembolization.21 Most strokes occur following an uneventful emergence from anesthesia, and do not present until post-operative day two.16,19 Although intra-operative events, such as hypotension or thromboembolism from aortic manipulation in cardiac surgery, can cause intra-operative strokes that manifest immediately following anesthesia, the more commonly encountered delayed form of stroke following surgery likely has a different pathophysiology.22 Major surgery induces a patient-specific inflammatory profile.23 The acute stress response to surgery likely contributes to the creation of a hyper-coagulable and neuro-inflammatory milieu that impairs neuro-protective mechanisms and can lead to stroke.20

Risk factor modification to prevent stroke hinges on life-style changes and medical therapy for hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and hypertension.24 Patients with a history of cerebral ischemia are at higher risk for stroke, and are commonly maintained on lifelong lipid-lowering25 and antiplatelet therapy.26 Pharmacologic anticoagulation for patients with atrial fibrillation or a mechanical heart valve is managed by using different perioperative bridging strategies, after weighing the risk for stroke against the risk for procedural bleeding.27 Although intraoperative hypotension is associated with stroke,18 defining optimal blood pressure targets for an individual patient remains challenging. New approaches use near-infrared spectroscopy to delineate patient-specific limits of cerebral blood flow auto-regulation.28 Gaining more insight into intraoperative cerebral perfusion is an intriguing concept to better tailor hemodynamic management, even though available studies do not yet link monitoring of cerebral oxygenation to reliable prevention of neurologic injury.29

For the treatment of stroke, current guidelines emphasize early diagnosis and transfer to a stroke unit, general supportive therapy, including airway management and mechanical ventilation, and avoidance of further cerebral insults, for example through prevention of hyperthermia.30 The enthusiasm for endovascular therapy to treat acute ischemic stroke using intra-arterial thrombolysis or clot disruption has recently been dampened by two trials that showed no benefit when compared to systemic thrombolysis.31,32 However, given that systemic tissue plasminogen activator administration is contraindicated following surgery, endovascular stroke therapy may still hold promise for select cases of perioperative stroke. Concepts for stroke therapy remain in flux, and many previously pursued strategies, such as intensive insulin treatment, are now obsolete.33,34

Although at least 1,000 substances have been experimentally proven to exert neuroprotective properties, more than 280 clinical studies have not identified a drug that approaches the (low) efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator.35,36 Emerging knowledge has led to a new appreciation for the role of the immune system in the pathophysiology of stroke. It is no longer considered a mere by-stander, but an active mediator of processes linked to brain damage and reconstruction.37 Immuno-adaptive host responses by lymphocytes have both detrimental38 and protective39 effects following ischemia reperfusion (I/R) injury to the brain. Recent advances in the understanding of their key differential role for immune-mediated cerebro-protection have the potential to inform the development of novel approaches for the treatment of stroke.

The brain mounts a profound inflammatory response to post-ischemic reperfusion. The innate immune response includes polynuclear cells, macrophages, and other resident cells that are activated through damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from damaged host cells.40 Innate immunity is non-specific and dominates the early phase of the body’s defense. Adaptive immune responses refer to antigen-specific actions by lymphocytes that require more time to develop and also induce memory.36 To better understand the role of lymphocytes in stroke, Hurn and colleagues examined the effects of temporary occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in severe combined immuno-deficient mice that lack B-cells and T-cells.38 The observation that the severe combined immuno-deficient mice showed a less pronounced inflammatory response might seem intuitive; however, they also displayed a decrease in brain infarct volume compared to the wild-type mice. Kleinschnitz and colleagues showed that when B-cells are reconstituted in mice lacking T- and B-cells, infarct volumes are not affected, thereby indicating that T-cells are likely responsible for the observed greater degree of brain damage in wild-type animals.41 The detrimental effects of T-lymphocytes in the post-ischemic brain are thought to be in part due to superoxide production42, a key mediator of oxidative stress leading to exaggerated brain damage following I/R.43 Translation of these findings into clinical therapies is not straightforward. Infectious complications are a primary cause of death following stroke, and previous clinical trials that tested immunosuppressive strategies have failed.44,45 An appealing alternative approach to general immunosuppression could be the targeted augmentation of protective and restorative components of the adaptive immune response.

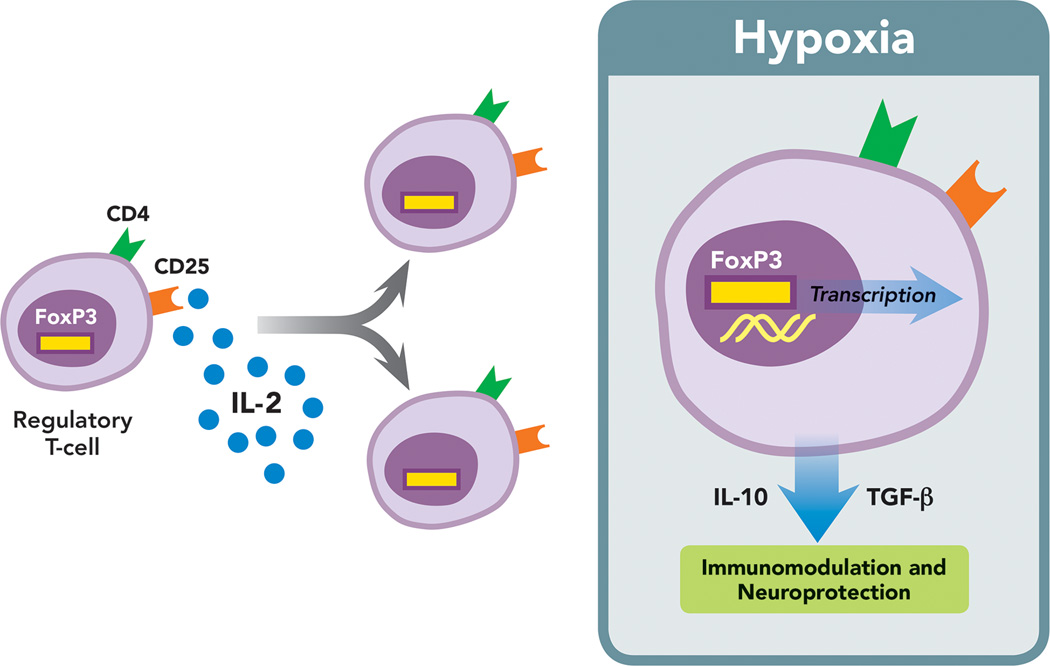

Specific subpopulations of T-lymphocytes including natural killer T-cells46 and regulatory T-cells39,47 have beneficial effects in models of cerebral ischemia. Regulatory T-cells are characterized by their expression of the surface molecules cluster of differentiation (CD)4 and CD25 in conjunction with the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3). Interleukin-2 (IL-2) binds to CD-25 and induces proliferation of regulatory T-cells to ensure their physiologic maintenance (Figure 2).48 Hypoxia leads to induction of FoxP3 and thereby solicits anti-inflammatory mechanisms conferred by regulatory T-cells.49 Depletion of regulatory T-cells using a CD25-specific antibody lead to increased brain damage and worse functional outcomes in a mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion, thereby suggesting a protective role for these cells mediated by the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.39 In a genetic association study of participants in the PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) trial, the clinical relevance of decreased IL-10 production was highlighted by the association of cerebrovascular events and the single-nucleotide polymorphism 2849AA in the promoter region of IL-10.50 Successful therapeutic activation of regulatory T-cells using low doses of IL-2 has been reported in clinical trials with patients suffering from graft-versus-host disease51 and hepatitis C-induced vasculitis.52 Targeting the immunologic response to cerebral I/R, for example by administering cytokine therapy to foster neuroprotective effects mediated by regulatory T-cells, might prove to be a valuable approach to perioperative organ protection in the future (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Activation of regulatory T-cells.

Regulatory T-cells are a subpopulation of immuno-modulatory T-cells characterized by expression of the cell surface molecules cluster of differentiation (CD)4 and CD25, and by the presence of the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3). Binding of interleukin (IL)-2 to CD25 induces proliferation of regulatory T-cells and is required to ensure their physiologic maintenance.48 FoxP3 expression is induced under hypoxic conditions and regulates target genes that govern immuno-modulatory functions.49 Neuroprotective effects are mediated by regulatory augmentation of T-cell proliferation and activity as well as by synthesis of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1039 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β.37 Therapeutic activation of regulatory T-cells has been successfully achieved through exogenous administration of IL-2 in clinical trials of primarily non-neurologic diseases.51,52 This approach may serve as a model for studying neuroprotective effects by regulatory T-cells in perioperative stroke.

Myocardial Infarction

MI is defined as an elevated plasma cardiac troponin concentration that exceeds the 99th percentile of a normal reference population in conjunction with one of the following: 1) symptoms of ischemia; 2) ST-segment / T-wave changes, new left bundle branch block, or development of pathological Q-waves on electrocardiogram; 3) evidence of new wall motion abnormalities or loss of viable myocardium on imaging; or 4) detection of an intracoronary thrombus.53 During the perioperative period of major non-cardiac surgery, the incidence of MI is 1-3%,54,55 and is associated with an increased risk for death. In a recent multicenter international cohort study of 8351 surgical patients at risk for atherosclerotic disease, 30-day mortality was 11.6% in patients who suffered perioperative MI, compared to 2.2% in those who did not.56

MI occurs when cardiomyocytes die, which is a consequence of prolonged ischemia. Ischemia can result from acute intracoronary flow occlusion, usually secondary to the rupture of a fissured atherosclerotic plaque (type 1 MI). Nonsurgical MI is often associated with intracoronary thrombus formation.57,58 Alternatively, an ischemic imbalance is caused by a supply/demand mismatch brought on by conditions other than coronary artery disease alone, for example, anemia, arrhythmia, hypotension, or hypertension (type 2 MI).53 Since such conditions are frequently encountered in the operating room and intensive care unit, one might suspect that demand ischemia is responsible for most perioperative MIs. Angiographic studies of patients treated for post-operative MI have shown conflicting data regarding classification into type-1 versus type-2 MI.59,60 Since histopathologic examination of the coronaries is only possible after death, plaque disruption found on autopsy in 46%-55% of cases61,62 is not likely representative of the MI mechanism in the surviving majority of surgical patients. The pathophysiologic mechanisms probably vary, but a common pathway for MI in the perioperative environment is a supply/demand mismatch in which hemodynamic instability and a hypercoagulable state lead to cardiac ischemia and ST depression with eventual cell death and troponin increase.63

Standard pharmacologic approaches for the treatment of coronary artery disease and prevention of myocardial ischemia include beta-blockers, antiplatelet agents, statins, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, and nitrates. Unfortunately, effective pre-emptive medical therapy for high-risk surgery patients has not yet been developed. Even promising strategies, such as perioperative beta-blockade, have not succeeded in decreasing postoperative mortality.64 Invasive therapeutic options for coronary artery disease and MI include catheter-based, as well as operative revascularization techniques. When myocardial ischemia progresses to heart failure, temporary and permanent tools, designed to support or assume the pump function of the heart include intra-aortic balloon pumps and an ever-growing armamentarium of ventricular assist and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation devices. Although the progression of MI to severe heart failure within the immediate perioperative period is uncommon, myocardial injury leading to troponin elevations remains not only a frequent occurrence,65 but also an independent predictor of mortality following surgery.66 This has reinforced efforts to develop more effective cardio-protective strategies.

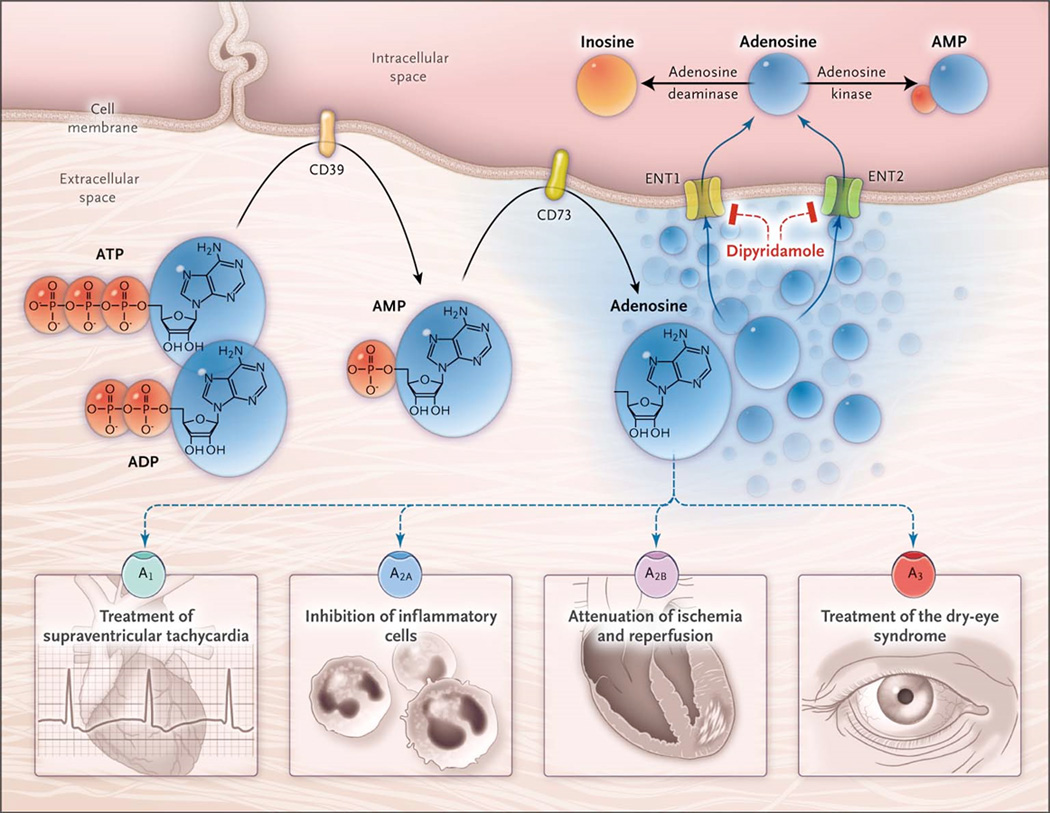

Many novel approaches to prevent and treat MI are currently under investigation. Here we discuss new and emerging concepts developed from an improved understanding of the function and metabolism of an old drug - adenosine. Adenosine is well known to clinicians for its ability to arrest conduction of the atrioventricular node, thereby permitting diagnosis and treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias. While this mechanism of action is based on activation of the A1 adenosine receptor (ADORA1), a total of 4 adenosine receptors mediate distinctly different biologic effects via separate signaling pathways (Figure 3).67

Figure 3. Extracellular Adenosine Signaling and Its Termination.

In inflammatory conditions, extracellular adenosine is derived predominantly from the enzymatic conversion of the precursor nucleotides ATP and ADP to AMP through the enzymatic activity of the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (CD39) and the subsequent conversion of AMP to adenosine through ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73). Extracellular adenosine can signal through four distinct adenosine receptors: ADORA1 (A1), ADORA2A (A2A), ADORA2B (A2B), and ADORA3 (A3). An example of the functional role of extracellular adenosine signaling is A1-receptor activation during intravenous administration of adenosine for the treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. In addition, experimental studies implicate activation of A2A that is expressed on inflammatory cells such as neutrophils180 or lymphocytes in the attenuation of inflammation.181,182 Other experimental studies provide evidence of signaling events through A2B in tissue adaptation to hypoxia and attenuation of ischemia and reperfusion.93,94,96 A clinical trial has shown that an oral agonist of the A3 adenosine receptor may be useful in the treatment of the dry-eye syndrome.183 Adenosine signaling is terminated by adenosine uptake from the extracellular space toward the intracellular space, predominantly through equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) and equilibrative nucleoside transporter 2 (ENT2), followed by metabolism of adenosine to AMP through the adenosine kinase or to inosine through the adenosine deaminase. Blockade of equilibrative nucleoside transporters by dipyridamole is associated with increased extracellular adenosine concentrations and signaling (e.g., during pharmacologic stress echocardiography or in protection of tissue from ischemia).

From: Purinergic signaling during inflammation; Holger K. Eltzschig, M.D., Ph.D., Michail V. Sitkovsky, Ph.D., and Simon C. Robson, M.D., Ph.D., N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2322-2333 © (2012) Massachusetts Medical Society.67 Reprinted with permission.

Although restoration of flow through acutely obstructed coronaries is the goal of interventional treatment for MI, reperfusion itself can exacerbate tissue injury,68 e.g. via leukocyte transmigration leading to exacerbation of local inflammation.69 Extracellular adenosine triphosphate is the precursor to adenosine and its release is modulated in the setting of hypoxia and inflammation.70–72 Adenosine signaling has been strongly implicated in the attenuation of I/R injury in multiple organs, including the heart.73–79 In 2005 Ross and colleagues studied the effect of intravenous adenosine infusion on clinical outcomes and infarct size in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients undergoing reperfusion therapy (AMISTAD-2 trial).80 This study and a post hoc analysis81 showed that patients who received higher concentrations of adenosine infusion (70µg/kg/min) had smaller myocardial infarct sizes, a finding that correlated with fewer adverse clinical events. In a subset of patients who received adenosine within 3.17 hours of onset of evolving MI, early and late survival was enhanced and the composite clinical endpoint of death at 6 months was reduced. The fact that this study did not show even more dramatic therapeutic effects of adenosine infusions could be related to the extremely short extracellular half-life of adenosine. Alternatively, combining adenosine infusions with an adenosine uptake inhibitor – such as dipyridamole,82–87 or use of direct pharmacological adenosine receptor agonists88 may yield even better therapeutic effects for the treatment of ischemic disease states.89,90

Basic research studies provide compelling evidence that the A2B adenosine receptor (ADORA2B) in particular can provide potent cardioprotection against I/R injury. Mice with genetic deletion of the Adora2b gene have increased myocardial infarct sizes,91,92 while a specific agonist of the ADORA2B (BAY 60-6583)93–95 attenuates myocardial I/R injury.91,92,96 Mechanistic studies link ADORA2B-dependent cardio-protection to the circadian rhythm protein Period 2 (Per2). Per2 stabilization by adenosine receptor activation or by light therapy emulates adenosine-mediated cardio-protection.96 These findings are consistent with studies that show increased susceptibility to the detrimental effects of myocardial ischemia in the early morning hours.89 Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that adenosine signaling could become a novel therapeutic approach to prevent or treat ischemic myocardial tissue injury in surgical patients. In future studies, the effectiveness of specific adenosine receptor agonists (e.g. for ADORA2B) must be tested in a clinical setting.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

A 2011 consensus conference held in Berlin redefined the diagnostic criteria ARDS.97 These now include: 1) Acute onset within one week of a pulmonary insult or manifestation of symptoms, 2) Bilateral opacities not fully explained by another cause, 3) Exclusion of heart failure or fluid overload as causative for respiratory failure, and 4) differentiation into mild, moderate, and severe ARDS based on a value of ≤300, ≤200, and ≤100 mmHg, respectively, for the ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspiratory oxygen (Pao2/Fio2) at a minimum of 5 cm H2O positive end-expiratory pressure. The previously used definition of Acute Lung Injury is now referred to as mild ARDS. In a single-institution cohort study of 50,367 general surgery patients the reported incidence of ARDS was only 0.2%.98 In higher risk surgeries, ARDS occurs in 2%–15% of patients.99 Mortality in affected surgical patients is high and ranges from 27%–40%.98,100 Surprisingly, Phua and colleagues found that the mortality rate secondary to ARDS has not changed since the introduction of the first standard definition of the syndrome in 1993.101

ARDS can occur as a result of direct injury, such as pneumonia, aspiration, or pulmonary contusion. Indirect insults causing ARDS include sepsis, transfusion of blood products, shock, or pancreatitis.102 Breakdown of the alveolar-capillary membrane causes accumulation of proteinaceous intra-alveolar fluid that is accompanied by formation of hyaline membranes on the denuded epithelial basement membrane of the alveolus. Washout of alveolar surfactant predisposes the lungs to atelectasis and decreased compliance.103 Influx of neutrophils and activation of alveolar macrophages constitute the basis for the innate immune response. Maintaining a balance between activation of pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways might determine whether the initial pulmonary insult is resolved or progresses to ARDS.

Triggers that exacerbate lung inflammation include microbial products and DAMPs, which are recognized by Toll-like receptors.104 A complex interplay of inflammasomes, cytokines, complement, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and mediators of oxidative stress sustains the biochemical injury.105,106 Fibrosing alveolitis, characterized by neovascularization and infiltration of the alveolar space with mesenchymal cells, develops in some patients and is associated with poorer outcomes.103

A key dilemma in the therapeutic approach to ARDS is the double-edged nature of the most commonly applied treatment - mechanical ventilation. Mechanical ventilation per se induces lung injury via a complex combination of mechanisms referred to as ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).107 Ongoing biophysical injury by repeated opening and closing of alveoli (atelectrauma), over-distention (volutrauma), and high transpulmonary pressures (barotrauma) exacerbates the initial lung injury.105

Current therapy for ARDS consists of limiting further iatrogenic damage to the injured lungs by applying a lung protective ventilation strategy with tidal volumes ≤ 6 mL/kg, plateau pressures ≤ 30 cmH2O and appropriate positive end-expiratory pressure based on the required minimal FiO2.108 Prone positioning promotes ventilation of dependent parts of the lung. In a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial, Guerin and colleagues recently demonstrated a survival benefit when proning is initiated early in severe ARDS.109 High-frequency oscillation ventilation constitutes yet another alternative to conventional mechanical ventilation; however, it does not seem to confer a mortality benefit.110,111 Other therapeutic strategies used to limit harmful effects of VILI include limiting the volume of administered intravenous fluids,112 and considering early administration of neuromuscular blocking agents.113 Multiple attempts have been made to pharmacologically attenuate the pro-inflammatory cascade encountered in ARDS. Unfortunately, randomized clinical trials, using methylprednisolone114 or omega-3 fatty acids115 have failed to prove any benefit, and have actually suggested harmful effects from these drugs.

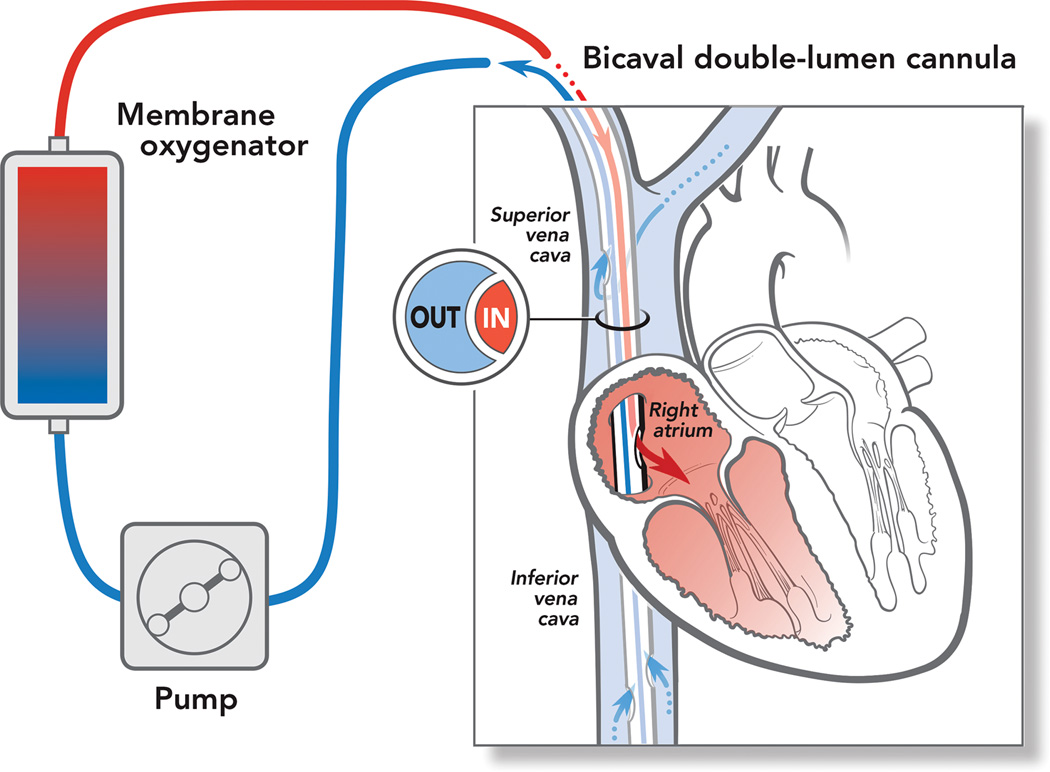

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has been used to treat respiratory failure for more than 40 years,116 but it has recently experienced a renaissance. The concept of attenuating the effects of ongoing VILI in patients suffering from ARDS (Figure 4) has received new interest with the advent of modern veno-venous ECMO technology,117 the reports of its successful use during the H1N1 influenza outbreak,118 and the encouraging results of a randomized clinical trial by Peek and colleagues using ECMO in adult patients with severe respiratory failure.119 In this study, 180 patients were randomized to continue conventional management or be referred for transport to a specialized center for consideration of ECMO therapy. Sixty-three percent of patients in the group that was transferred for ECMO consideration survived 6 months without disability compared with 47% in the conventional group. An obvious source of bias for the interpretation of these results is that ECMO initiation did not occur at the site of randomization, but rather was preceded by evaluation and treatment following transport to the ECMO center. Ultra-low tidal volume mechanical ventilation has also been used in combination with veno-venous ECMO in an attempt to limit VILI by reducing plateau pressures in conjunction with extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal in ARDS patients.120 In a recent prospective randomized trial, ECMO combined with ultra-low tidal volume mechanical ventilation (3 mL/kg) was compared to conventional protective mechanical ventilation (6 mL/kg), and confirmed feasibility of this approach.121 Although the primary outcomes (ventilator-free days in a 28- and 60-day period) were not statistically different, a post-hoc analysis of patients with severe ARDS showed a shorter mechanical ventilation time within a 60-day period.

Figure 4. Veno–venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO).

A bicaval, double-lumen central venous cannula is placed in the right internal jugular vein. Deoxygenated blood is collected from both the inferior and the superior vena cava. After passing through a centrifugal pump and a membrane oxygenator, the oxygenated blood is then returned to the right atrium through the cannula’s second lumen’s orifice. Various configurations are currently in use, including pumpless systems and alternative cannulation techniques.

While it is too early to endorse ECMO as a routine therapy for patients with severe ARDS, the concept of attenuating ongoing VILI by enabling ultra-protective mechanical ventilation via extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal, deserves further study.

Acute Kidney Injury

Two sets of criteria that define AKI have gained widespread acceptance and form the basis for the current Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines:122 First, the classification into Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss or End Stage Kidney Disease (RIFLE) by the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative123. Second, the three stages of the modified version of the RIFLE criteria created by the AKI Network.124 Both systems use serum creatinine or urine output in addition to glomerular filtration rate (RIFLE) or need for renal replacement therapy (AKI Network) as basis for classification, and both have high sensitivity and specificity to detect AKI. However, decreased urine output and increased serum creatinine occur relatively late following the initial insult, and newer biomarkers permit earlier detection of injury. These include neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, kidney injury molecule-1, and more recently insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2.125 Whether improved bio-markers will affect clinical outcomes, still needs to be determined. The incidence of AKI remains high. In a cohort of 75,952 general surgical procedures, Kheterpal and colleagues reported a rate of 1%.126 In this study, mortality of patients with perioperative AKI was increased eight-fold to 42%.

Historically, the origins of AKI have been classified as pre-renal, intrinsic, and post-renal. The ischemic forms, pre-renal azotemia and acute tubular necrosis, are the most common causes of AKI in hospitalized patients.127 AKI represents a continuum of injury, and the distinction between pre-renal azotemia and acute tubular necrosis is likely not reflective of tubular biology.123 Focus has shifted to the importance of early detection and intervention to prevent worsening of AKI, as even modest decreases in glomerular filtration rate have profound effects on mortality of hospitalized patients.128

Therapy of AKI rests on treating the underlying cause, such as infection, anemia, low cardiac output, or post-renal obstruction. Protecting the kidney from additional insults includes avoiding nephrotoxic drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aminoglycosides, and intravenous contrast agents, whenever possible.129 Recent clinical trials identified low-molecular weight hydroxyethylstarches as potent nephrotoxins in a diverse cohort of intensive care unit patients130 and as a cause of an increased death rate in septic patients.131

Pharmacologic therapy for AKI is still attempted, although clinical trials have shown that most drugs are ineffective or even harmful. In a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in 328 critically ill patients, low-dose dopamine had no impact on mortality or indices of renal function.132 It was however associated with higher rates of atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery.133 While furosemide can be used to treat hypervolemia, it actually increased serum creatinine values in a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of patients following cardiac surgery.134 Glomerular filtration rate can decrease following furosemide administration,135 potentially raising plasma creatinine concentrations. However, forced diuresis can also lead to hypovolemia, secondary renal hypoperfusion, and subsequent AKI. Renal replacement therapy is initiated if the decreased clearance function leads to severe metabolic sequelae such as acidemia, hyperkalemia, volume overload, or uremia. In a clinical trial that evaluated different strategies for renal replacement therapy for AKI in critically ill patients only 5.6% needed to continue replacement therapy at 90 days post initiation; however, 44.7% had died.136

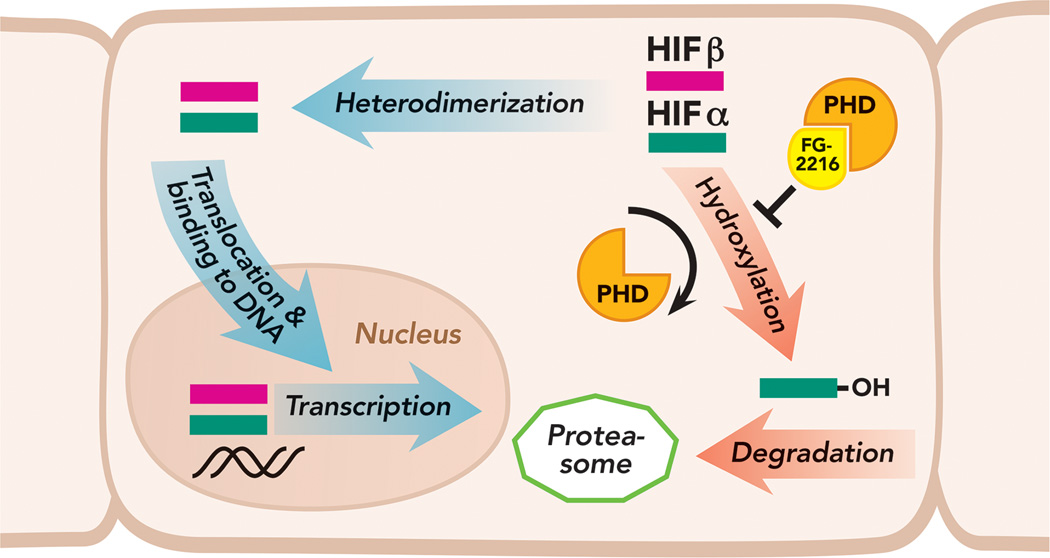

Several recent studies have increased our understanding of the kidney’s response to ischemia. Renal ischemia drives persistent renal hypoxia, which leads to concomitant stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF).87 In a hypoxic environment, HIF controls the expression of more than 100 genes that are involved with vital cell functions, such as glucose metabolism, pH-control, angiogenesis, and erythropoiesis.137,138 HIF is a heterodimer that consists of two subunits - the oxygen-sensitive HIF-α and the constitutively expressed HIF-β139 These subunits translocate to the cell nucleus, where they become highly effective regulators of gene expression by binding to the hypoxia response promoter element. HIF-activated gene expression is repressed under normoxic conditions. One control mechanism that inhibits HIF-dependent gene transcription involves hydroxylation of HIF-α via oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases, which tag HIF-α for degradation in the cell proteasome (Figure 5).140

Figure 5. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent gene expression via prolyl hydroxylase inhibition.

Under hypoxic conditions (blue arrows), HIF-α and the constitutively expressed HIF-β bind and translocate into the cell nucleus. After binding to the DNA hypoxia response promoter element, the HIF heterodimer induces expression of hypoxia-sensitive genes. Under normoxic conditions (red arrows), prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs) hydroxylate HIF-α and thereby mark it for proteasomal degradation, effectively inhibiting HIF-dependent gene expression. Prevention of proteasomal HIF-α degradation using prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors, e.g., FG-2216,144 activates hypoxia-activated signaling pathways even under normoxic conditions.

Hypoxia-sensitive signaling mechanisms may inform the development of novel perioperative organ protective strategies.87,94 Conde and colleagues reported HIF-1α to be expressed in human renal tubular cells obtained from kidney biopsies following renal transplantation, and its presence was negatively correlated with the degree of acute tubular necrosis.141 Preventing proteasomal degradation of HIF by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylases confers renal protection in animal models of I/R142 and in a model of gentamicin induced AKI.143 The oral drug FG-2216 inhibits prolyl hydroxylases, and it has already been successfully used in a clinical phase-1 study to increase endogenous erythropoietin synthesis in patients with end-stage renal disease.144 Thus, clinically tested prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in conjunction with emerging evidence from animal studies suggest that hypoxia-activated signaling pathways are promising targets for prevention of perioperative AKI.

Acute Gut Injury

The true medical impact of perioperative AGI remains the target of intense clinical and experimental investigation. The incidence of clinically overt AGI following major non-abdominal surgery, such as cardiopulmonary bypass or lung transplantation surgery, is relatively low (0.3%–6.1%), but is associated with significant morbidity and a high mortality risk (18–58%).145,146

Different specific factors influence particular AGI manifestations, e.g. the altered coagulation state following cardiopulmonary bypass in the context of gastro-intestinal bleeding. Beyond this, splanchnic perfusion abnormalities and associated mucosal I/R injury form a central common pathophysiologic insult. The intestinal mucosa is supported by a complex underlying vasculature.147 Especially in low-flow states (shock, cardiopulmonary bypass perfusion), oxygen is shunted away from the villus tip via a countercurrent mechanism, therefore exposing the epithelium to significant hypoxia.148–150 In its most extensive form, such intestinal hypo-perfusion presents as mesenteric ischemia, which occurs in approximately 0.15%145 of cardiopulmonary bypass patients compared to 0.00012% of the general medical population.151 While hard evidence is limited, ischemia in low-flow states appears to be largely non-occlusive. 152,153 Whereas in the general medical population, about 84% of mesenteric ischemia is caused by embolism, arterial or venous thrombosis.151

Major mesenteric ischemia is a clinical emergency because of the rapid development of a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which is associated with distant organ injury and ultimately, multiple organ failure. Consequently, the question has been raised of whether mesenteric ischemia represents only the “tip-of-the-iceberg,” and whether beyond this, subclinical AGI secondary to episodes of low blood flow is the insidious source of perioperative inflammatory activation. Indeed, in critical illness or following cardiopulmonary bypass, signs of intestinal injury and parallel loss of intestinal barrier function are regularly observed.154–156 However, lack of clear evidence that directly links bacterial translocation to outcome has triggered a re-evaluation of the concept of gut-origin sepsis, and has led to an increased focus on the concomitant release of nonbacterial gut-derived inflammatory and tissue injurious factors.157 The rapid release of preformed effectors from cellular sources such as mucosal mast cells or Paneth cells at the base of the epithelial crypt may explain both the promptness and the potency of intestinal responses to I/R (Figure 6).

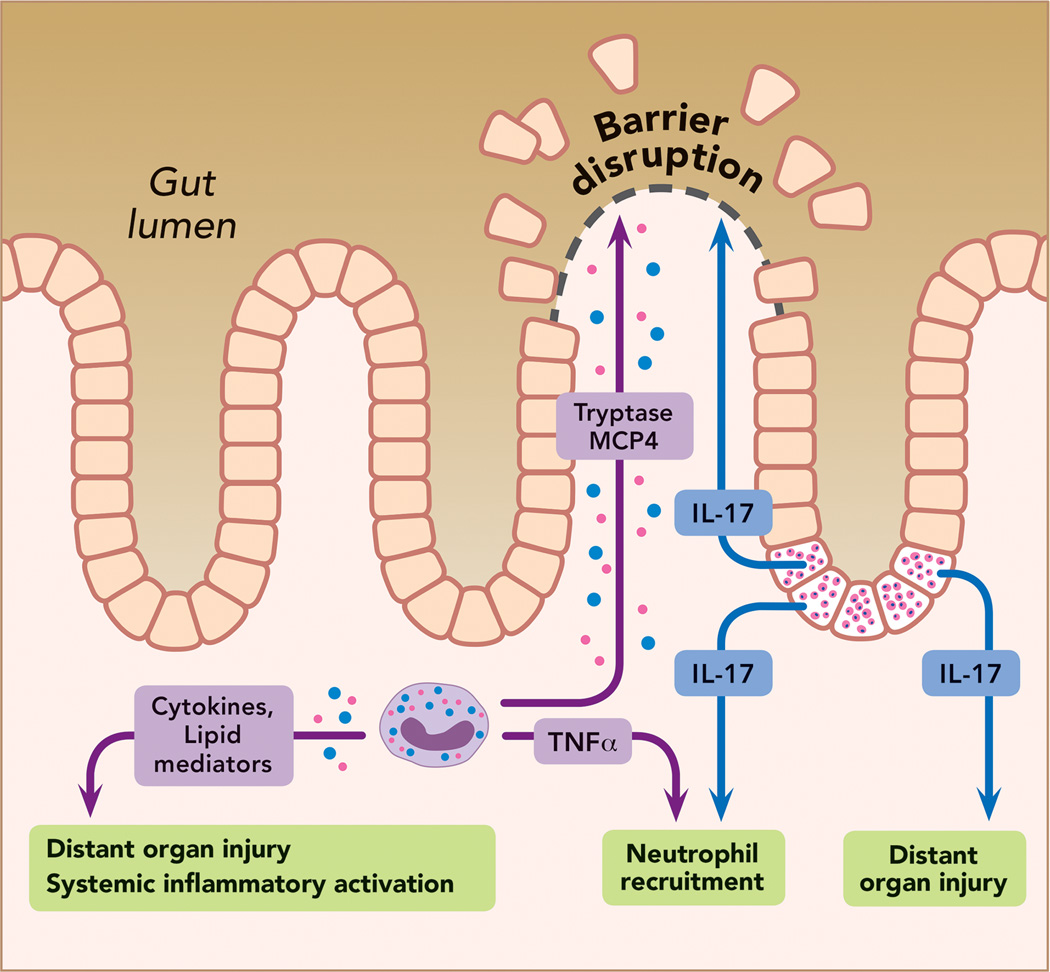

Figure 6. Paneth cells and intestinal Mast cells release potent effectors to regulate local injury and systemic inflammation following intestinal ischemia/reperfusion.

Most prominently, the Paneth cell-dependent pathway (blue) depends on release of interleukin (IL)-17 from Paneth cells localized at the base of small intestinal crypts. Mast cell responses (purple) use a number of pre-formed and de novo-synthesized products such as proteases (tryptase, mast cell protease (MCP)4), lipid mediators (leukotriens, prostaglandins) and cytokines (tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6).

Paneth cells are highly secretory cells of the intestine that release various antimicrobial peptides and important inflammatory mediators.158 Until recently, Paneth cell function has been regarded as host-protective, particularly in the sense of anti-microbial control.159 More recently, it was revealed that Paneth cell-derived IL-17 not only mediates local damage and distant organ injury in murine intestinal I/R160, but also plays a critical role in multi-organ dysfunction after hepatic I/R injury161, and following tumor necrosis factor-α-induced shock.162 Much attention has focused on inflammatory activation by non-microbial DAMPs and the role of the toll-like receptors in I/R injury.163 As such, shock-induced AGI is toll-like receptor 4 dependent.164 New data suggest that IL-17 constitutes an important activator of this pathway,165 which is noteworthy, as the established endogenous toll-like receptor 4 ligands HMGB1, heat shock protein-70 or -27, or hyaluronic acid do not seem to be involved.164

Another source of potent effectors of tissue injury and inflammation are mucosal mast cells (MCs). As important immune surveillance cells strategically positioned within the gut wall, their physiologic role is slowly evolving beyond the traditional focus on allergy.166–168 MCs exert local and systemic effects via rapid release of preformed proteases, mediators and cytokines. For example, MC-tryptase169,170, as well as MC-protease 4171 have been implicated in the breakdown of tight junctions in various mucosal epithelia, including the gut. Release of preformed tumor necrosis factor-α from MCs is a powerful inflammatory stimulus that not only promotes local pathogen clearance,172 but also drives detrimental systemic inflammatory deregulation in critical illness.173,174 The role of MCs in intestinal I/R injury has been studied extensively,175–177 with recent reports suggesting that MCs may influence perioperative outcomes: In a rat model of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, intestinal MC activation contributed to intestinal injury and intestinal barrier disruption, as well as to the release of systemic cytokines.178 Similarly, in a piglet model of ECMO, systemic inflammatory responses appeared to stem from mediators released by splanchnic MCs.179

Although this overview is incomplete, the highlighted mechanisms exemplify an increased appreciation for non-classical pathways in the control of tissue injury and inflammatory activation. Because they constitute very early events in intestinal I/R, such mechanisms show great promise for the development of novel therapeutic approaches to reduce the local and systemic consequences of intestinal hypo-perfusion.

Conclusions

Despite major advances in the delivery of anesthesia, perioperative morbidity and mortality remain a major public health problem. The magnitude of all-cause mortality following surgery approximates the third leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease and cancer. While this serves as a sobering recognition of the status quo, it also points to tremendous opportunities in anesthesiology to drive medical progress and fundamentally improve patient outcomes.

This review did not attempt to encompass the abundance of worthy approaches that are currently underway to improve survival from acute organ injury. Its purpose was instead to summarize current strategies and to present an exemplary outlook of promising ideas for prevention and treatment of commonly encountered perioperative pathologies – stroke, MI, ARDS, AKI, and AGI. A key conclusion is that the discussed cellular and molecular responses to injury are active, inter-related components. They play key roles in the development of the disease process and are not merely bystander reactions. The injury-induced adaptations are complex and convey both protective and injurious effects on the tissues. Future approaches to reduce perioperative morbidity and mortality will require ongoing efforts to better understand mechanisms of acute organ injury. Nevertheless, we believe that this area of research represents the most important opportunity to improve outcomes of surgery and anesthesia.

Summary Statement.

Prevention and treatment of acute organ injury in surgical patients represents a critical challenge for the field of perioperative medicine. Here, we discuss manifestations of perioperative organ injury and provide examples for novel treatment approaches.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kathy Gage for her editorial contributions to this manuscript.

Disclosure of funding: This work was supported by a Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Roizen Anesthesia Research Foundation, Richmond, VA, USA grant to Jörn Karhausen, an American Heart Association, Dallas, TX, USA grant to Eric T. Clambey, an American Heart Association, Dallas, TX, USA grant to Almut Grenz, and National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA grants R01-DK097075, R01-HL0921, R01-DK083385, R01-HL098294, POIHL114457-01, and a grant by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA), New York, NY, USA to Holger K. Eltzschig.

Footnotes

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK9_2006.pdf Accessed last on 07/16/2013

Conflicts of interest statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Evers AS, Miller RD. Can we get there if we don't know where we're going? Anesthesiology. 2007;106:651–652. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000264751.31888.be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobo SM, Rezende E, Knibel MF, Silva NB, Paramo JA, Nacul FE, Mendes CL, Assuncao M, Costa RC, Grion CC, Pinto SF, Mello PM, Maia MO, Duarte PA, Gutierrez F, Silva JM, Jr, Lopes MR, Cordeiro JA, Mellot C. Early determinants of death due to multiple organ failure after noncardiac surgery in high-risk patients. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:877–883. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e2bf8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayr VD, Dunser MW, Greil V, Jochberger S, Luckner G, Ulmer H, Friesenecker BE, Takala J, Hasibeder WR. Causes of death and determinants of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2006;10:R154. doi: 10.1186/cc5086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dulhunty JM, Lipman J, Finfer S. Sepsis Study Investigators for the ACTG: Does severe non-infectious SIRS differ from severe sepsis? Results from a multi-centre Australian and New Zealand intensive care unit study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1654–1661. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beecher HK, Todd DP. A study of the deaths associated with anesthesia and surgery: Based on a study of 599, 548 anesthesias in ten institutions 1948–1952, inclusive. Ann Surg. 1954;140:2–35. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195407000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li G, Warner M, Lang BH, Huang L, Sun LS. Epidemiology of anesthesia-related mortality in the United States, 1999–2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:759–765. doi: 10.1097/aln.0b013e31819b5bdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawashima Y, Takahashi S, Suzuki M, Morita K, Irita K, Iwao Y, Seo N, Tsuzaki K, Dohi S, Kobayashi T, Goto Y, Suzuki G, Fujii A, Suzuki H, Yokoyama K, Kugimiya T. Anesthesia-related mortality and morbidity over a 5-year period in 2,363,038 patients in Japan. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:809–817. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bainbridge D, Martin J, Arango M, Cheng D. Perioperative and anaesthetic-related mortality in developed and developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1075–1081. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noordzij PG, Poldermans D, Schouten O, Bax JJ, Schreiner FA, Boersma E. Postoperative mortality in The Netherlands: A population-based analysis of surgery-specific risk in adults. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1105–1115. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d5f95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semel ME, Lipsitz SR, Funk LM, Bader AM, Weiser TG, Gawande AA. Rates and patterns of death after surgery in the United States, 1996 and 2006. Surgery. 2012;151:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmers TK, Verhofstad MH, Moons KG, van Beeck EF, Leenen LP. Long-term quality of life after surgical intensive care admission. Arch Surg. 2011;146:412–418. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): A major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman BT, Schumacher HC, Wang S, Shaefi S, Berman MF. Perioperative acute ischemic stroke in noncardiac and nonvascular surgery: Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:231–238. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318194b5ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mashour GA, Shanks AM, Kheterpal S. Perioperative stroke and associated mortality after noncardiac, nonneurologic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1289–1296. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318216e7f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharifpour M, Moore LE, Shanks AM, Didier TJ, Kheterpal S, Mashour GA. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of perioperative stroke in noncarotid major vascular surgery. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:424–434. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826a1a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tarakji KG, Sabik JF, 3rd, Bhudia SK, Batizy LH, Blackstone EH. Temporal onset, risk factors, and outcomes associated with stroke after coronary artery bypass grafting. JAMA. 2011;305:381–390. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Filsoufi F, Rahmanian PB, Castillo JG, Bronster D, Adams DH. Incidence, imaging analysis, and early and late outcomes of stroke after cardiac valve operation. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1472–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bijker JB, Persoon S, Peelen LM, Moons KG, Kalkman CJ, Kappelle LJ, van Klei WA. Intraoperative hypotension and perioperative ischemic stroke after general surgery: A nested case-control study. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:658–664. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182472320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selim M. Perioperative stroke. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:706–713. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ng JL, Chan MT, Gelb AW. Perioperative stroke in noncardiac, nonneurosurgical surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:879–890. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31822e9499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momjian-Mayor I, Baron JC. The pathophysiology of watershed infarction in internal carotid artery disease: Review of cerebral perfusion studies. Stroke. 2005;36:567–577. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155727.82242.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hogue CW, Jr, Murphy SF, Schechtman KB, Davila-Roman VG. Risk factors for early or delayed stroke after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:642–647. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.6.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pillai PS, Leeson S, Porter TF, Owens CD, Kim JM, Conte MS, Serhan CN, Gelman S. Chemical mediators of inflammation and resolution in post-operative abdominal aortic aneurysm patients. Inflammation. 2012;35:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9294-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, Bacharach JM, Barr JD, Bush RL, Cates CU, Creager MA, Fowler SB, Friday G, Hertzberg VS, McIff EB, Moore WS, Panagos PD, Riles TS, Rosenwasser RH, Taylor AJ. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: Executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery. Circulation. 2011;124:489–532. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820d8d78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, 3rd, Goldstein LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE, Sillesen H, Simunovic L, Szarek M, Welch KM, Zivin JA. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549–559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration: Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wysokinski WE, McBane RD., 2nd Periprocedural bridging management of anticoagulation. Circulation. 2012;126:486–490. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono M, Zheng Y, Joshi B, Sigl JC, Hogue CW. Validation of a stand-alone near-infrared spectroscopy system for monitoring cerebral autoregulation during cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:198–204. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318271fb10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng F, Sheinberg R, Yee MS, Ono M, Zheng Y, Hogue CW. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring and neurologic outcomes in adult cardiac surgery patients: A systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:663–676. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318277a255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Jr, Bruno A, Connors JJ, Demaerschalk BM, Khatri P, McMullan PW, Jr, Qureshi AI, Rosenfield K, Scott PA, Summers DR, Wang DZ, Wintermark M, Yonas H. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciccone A, Valvassori L, Nichelatti M, Sgoifo A, Ponzio M, Sterzi R, Boccardi E. Endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:904–913. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broderick JP, Palesch YY, Demchuk AM, Yeatts SD, Khatri P, Hill MD, Jauch EC, Jovin TG, Yan B, Silver FL, von Kummer R, Molina CA, Demaerschalk BM, Budzik R, Clark WM, Zaidat OO, Malisch TW, Goyal M, Schonewille WJ, Mazighi M, Engelter ST, Anderson C, Spilker J, Carrozzella J, Ryckborst KJ, Janis LS, Martin RH, Foster LD, Tomsick TA. Endovascular therapy after intravenous t-PA versus t-PA alone for stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:893–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finfer S, Chittock DR, Su SY, Blair D, Foster D, Dhingra V, Bellomo R, Cook D, Dodek P, Henderson WR, Hebert PC, Heritier S, Heyland DK, McArthur C, McDonald E, Mitchell I, Myburgh JA, Norton R, Potter J, Robinson BG, Ronco JJ. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gandhi GY, Nuttall GA, Abel MD, Mullany CJ, Schaff HV, O'Brien PC, Johnson MG, Williams AR, Cutshall SM, Mundy LM, Rizza RA, McMahon MM. Intensive intraoperative insulin therapy versus conventional glucose management during cardiac surgery: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:233–243. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young AR, Ali C, Duretete A, Vivien D. Neuroprotection and stroke: Time for a compromise. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1302–1309. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macrez R, Ali C, Toutirais O, Le Mauff B, Defer G, Dirnagl U, Vivien D. Stroke and the immune system: From pathophysiology to new therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:471–480. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: From mechanisms to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:796–808. doi: 10.1038/nm.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hurn PD, Subramanian S, Parker SM, Afentoulis ME, Kaler LJ, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. T- and B-cell-deficient mice with experimental stroke have reduced lesion size and inflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1798–1805. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liesz A, Suri-Payer E, Veltkamp C, Doerr H, Sommer C, Rivest S, Giese T, Veltkamp R. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med. 2009;15:192–199. doi: 10.1038/nm.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinschnitz C, Schwab N, Kraft P, Hagedorn I, Dreykluft A, Schwarz T, Austinat M, Nieswandt B, Wiendl H, Stoll G. Early detrimental T-cell effects in experimental cerebral ischemia are neither related to adaptive immunity nor thrombus formation. Blood. 2010;115:3835–3842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brait VH, Jackman KA, Walduck AK, Selemidis S, Diep H, Mast AE, Guida E, Broughton BR, Drummond GR, Sobey CG. Mechanisms contributing to cerebral infarct size after stroke: Gender, reperfusion, T lymphocytes, and Nox2-derived superoxide. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1306–1317. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Warner DS, Sheng H, Batinic-Haberle I. Oxidants, antioxidants and the ischemic brain. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Enlimomab Acute Stroke Trial Investigators. Use of anti-ICAM-1 therapy in ischemic stroke: Results of the Enlimomab Acute Stroke Trial. Neurology. 2001;57:1428–1434. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krams M, Lees KR, Hacke W, Grieve AP, Orgogozo JM, Ford GA. Acute Stroke Therapy by Inhibition of Neutrophils (ASTIN): An adaptive dose-response study of UK-279,276 in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2543–2548. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000092527.33910.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong CH, Jenne CN, Lee WY, Leger C, Kubes P. Functional innervation of hepatic iNKT cells is immunosuppressive following stroke. Science. 2011;334:101–105. doi: 10.1126/science.1210301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu P, Hata R, Ogasawara M, Cao F, Kameda K, Yamauchi K, Schinkel AH, Maeyama K, Sakanaka M. Targeted disruption of organic cation transporter 3 (Oct3) ameliorates ischemic brain damage through modulating histamine and regulatory T cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1897–1908. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clambey ET, McNamee EN, Westrich JA, Glover LE, Campbell EL, Jedlicka P, de Zoeten EF, Cambier JC, Stenmark KR, Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha-dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T-cell abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2784–E2793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202366109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trompet S, Pons D, AJ DEC, Slagboom P, Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Cobbe SM, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Ford I, Hyland M, Gaw A, Macfarlane PW, Packard CJ, Norrie J, Perry IJ, Stott DJ, Sweeney BJ, Twomey C, Westendorp RG, Jukema JW. Genetic variation in the interleukin-10 gene promoter and risk of coronary and cerebrovascular events: The PROSPER study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:189–198. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, McDonough SM, Bindra B, Alyea EP, 3rd, Armand P, Cutler C, Ho VT, Treister NS, Bienfang DC, Prasad S, Tzachanis D, Joyce RM, Avigan DE, Antin JH, Ritz J, Soiffer RJ. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saadoun D, Rosenzwajg M, Joly F, Six A, Carrat F, Thibault V, Sene D, Cacoub P, Klatzmann D. Regulatory T-cell responses to low-dose interleukin-2 in HCV-induced vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2067–2077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD, Katus HA, Lindahl B, Morrow DA, Clemmensen PM, Johanson P, Hod H, Underwood R, Bax JJ, Bonow RO, Pinto F, Gibbons RJ, Fox KA, Atar D, Newby LK, Galvani M, Hamm CW, Uretsky BF, Steg PG, Wijns W, Bassand JP, Menasche P, Ravkilde J, Ohman EM, Antman EM, Wallentin LC, Armstrong PW, Januzzi JL, Nieminen MS, Gheorghiade M, Filippatos G, Luepker RV, Fortmann SP, Rosamond WD, Levy D, Wood D, Smith SC, Hu D, Lopez-Sendon JL, Robertson RM, Weaver D, Tendera M, Bove AA, Parkhomenko AN, Vasilieva EJ, Mendis S. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126:2020–2035. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, Thomas EJ, Polanczyk CA, Cook EF, Sugarbaker DJ, Donaldson MC, Poss R, Ho KK, Ludwig LE, Pedan A, Goldman L. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100:1043–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Yusuf S, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH. Surveillance and prevention of major perioperative ischemic cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A review. CMAJ. 2005;173:779–788. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Devereaux PJ, Xavier D, Pogue J, Guyatt G, Sigamani A, Garutti I, Leslie K, Rao-Melacini P, Chrolavicius S, Yang H, Macdonald C, Avezum A, Lanthier L, Hu W, Yusuf S. Characteristics and short-term prognosis of perioperative myocardial infarction in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:523–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davies MJ, Thomas AC. Plaque fissuring - the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J. 1985;53:363–373. doi: 10.1136/hrt.53.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeWood MA, Spores J, Notske R, Mouser LT, Burroughs R, Golden MS, Lang HT. Prevalence of total coronary occlusion during the early hours of transmural myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:897–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010163031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duvall WL, Sealove B, Pungoti C, Katz D, Moreno P, Kim M. Angiographic investigation of the pathophysiology of perioperative myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:768–776. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gualandro DM, Campos CA, Calderaro D, Yu PC, Marques AC, Pastana AF, Lemos PA, Caramelli B. Coronary plaque rupture in patients with myocardial infarction after noncardiac surgery: Frequent and dangerous. Atherosclerosis. 2012;222:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cohen MC, Aretz TH. Histological analysis of coronary artery lesions in fatal postoperative myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1999;8:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(98)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dawood MM, Gutpa DK, Southern J, Walia A, Atkinson JB, Eagle KA. Pathology of fatal perioperative myocardial infarction: Implications regarding pathophysiology and prevention. Int J Cardiol. 1996;57:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)02769-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Landesberg G. The pathophysiology of perioperative myocardial infarction: Facts and perspectives. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:90–100. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2003.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Devereaux PJ, Yang H, Yusuf S, Guyatt G, Leslie K, Villar JC, Xavier D, Chrolavicius S, Greenspan L, Pogue J, Pais P, Liu L, Xu S, Malaga G, Avezum A, Chan M, Montori VM, Jacka M, Choi P. Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery (POISE trial): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:1839–1847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Landesberg G, Mosseri M, Shatz V, Akopnik I, Bocher M, Mayer M, Anner H, Berlatzky Y, Weissman C. Cardiac troponin after major vascular surgery: The role of perioperative ischemia, preoperative thallium scanning, and coronary revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levy M, Heels-Ansdell D, Hiralal R, Bhandari M, Guyatt G, Yusuf S, Cook D, Villar JC, McQueen M, McFalls E, Filipovic M, Schunemann H, Sear J, Foex P, Lim W, Landesberg G, Godet G, Poldermans D, Bursi F, Kertai MD, Bhatnagar N, Devereaux PJ. Prognostic value of troponin and creatine kinase muscle and brain isoenzyme measurement after noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:796–806. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820ad503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eltzschig HK, Sitkovsky MV, Robson SC. Purinergic signaling during inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2322–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1205750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eltzschig HK, Collard CD. Vascular ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Br Med Bull. 2004;70:71–86. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petzelbauer P, Zacharowski PA, Miyazaki Y, Friedl P, Wickenhauser G, Castellino FJ, Groger M, Wolff K, Zacharowski K. The fibrin-derived peptide Bbeta15-42 protects the myocardium against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:298–304. doi: 10.1038/nm1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faigle M, Seessle J, Zug S, El Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. ATP release from vascular endothelia occurs across Cx43 hemichannels and is attenuated during hypoxia. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hart ML, Gorzolla IC, Schittenhelm J, Robson SC, Eltzschig HK. SP1-dependent induction of CD39 facilitates hepatic ischemic preconditioning. J Immunol. 2010;184:4017–4024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Riegel AK, Faigle M, Zug S, Rosenberger P, Robaye B, Boeynaems JM, Idzko M, Eltzschig HK. Selective induction of endothelial P2Y6 nucleotide receptor promotes vascular inflammation. Blood. 2011;117:2548–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-313957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bauerle JD, Grenz A, Kim JH, Lee HT, Eltzschig HK. Adenosine generation and signaling during acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:14–20. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eltzschig HK, Macmanus CF, Colgan SP. Neutrophils as Sources of Extracellular Nucleotides: Functional Consequences at the Vascular Interface. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eltzschig HK. Adenosine: An old drug newly discovered. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:904–915. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181b060f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hart ML, Henn M, Kohler D, Kloor D, Mittelbronn M, Gorzolla IC, Stahl GL, Eltzschig HK. Role of extracellular nucleotide phosphohydrolysis in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. FASEB J. 2008;22:2784–2797. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-103911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hart ML, Much C, Gorzolla IC, Schittenhelm J, Kloor D, Stahl GL, Eltzschig HK. Extracellular adenosine production by ecto-5'-nucleotidase protects during murine hepatic ischemic preconditioning. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1739–1750. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.064. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eckle T, Koeppen M, Eltzschig HK. Role of extracellular adenosine in acute lung injury. Physiology (Bethesda) 2009;24:298–306. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00022.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hart ML, Grenz A, Gorzolla IC, Schittenhelm J, Dalton JH, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-dependent protection from intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury involves ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) and the A2B adenosine receptor. J Immunol. 2011;186:4367–4374. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 80.Ross AM, Gibbons RJ, Stone GW, Kloner RA, Alexander RW. A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of adenosine as an adjunct to reperfusion in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMISTAD-II) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1775–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kloner RA, Forman MB, Gibbons RJ, Ross AM, Alexander RW, Stone GW. Impact of time to therapy and reperfusion modality on the efficacy of adenosine in acute myocardial infarction: The AMISTAD-2 trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2400–2405. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eckle T, Hughes K, Ehrentraut H, Brodsky KS, Rosenberger P, Choi DS, Ravid K, Weng T, Xia Y, Blackburn MR, Eltzschig HK. Crosstalk between the equilibrative nucleoside transporter ENT2 and alveolar Adora2b adenosine receptors dampens acute lung injury. FASEB J. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228551. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morote-Garcia JC, Rosenberger P, Nivillac NM, Coe IR, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter 2 attenuates mucosal inflammation during intestinal hypoxia. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:607–618. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Loffler M, Morote-Garcia JC, Eltzschig SA, Coe IR, Eltzschig HK. Physiological roles of vascular nucleoside transporters. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1004–1013. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.126714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eckle T, Grenz A, Kohler D, Redel A, Falk M, Rolauffs B, Osswald H, Kehl F, Eltzschig HK. Systematic evaluation of a novel model for cardiac ischemic preconditioning in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2533–H2540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00472.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eltzschig HK, Abdulla P, Hoffman E, Hamilton KE, Daniels D, Schonfeld C, Loffler M, Reyes G, Duszenko M, Karhausen J, Robinson A, Westerman KA, Coe IR, Colgan SP. HIF-1-dependent repression of equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT) in hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1493–1505. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Grenz A, Bauerle JD, Dalton JH, Ridyard D, Badulak A, Tak E, McNamee EN, Clambey E, Moldovan R, Reyes G, Klawitter J, Ambler K, Magee K, Christians U, Brodsky KS, Ravid K, Choi DS, Wen J, Lukashev D, Blackburn MR, Osswald H, Coe IR, Nurnberg B, Haase VH, Xia Y, Sitkovsky M, Eltzschig HK. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 (ENT1) regulates postischemic blood flow during acute kidney injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:693–710. doi: 10.1172/JCI60214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 88.Thiel M, Chouker A, Ohta A, Jackson E, Caldwell C, Smith P, Lukashev D, Bittmann I, Sitkovsky MV. Oxygenation inhibits the physiological tissue-protecting mechanism and thereby exacerbates acute inflammatory lung injury. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Eltzschig HK, Bonney SK, Eckle T. Attenuating myocardial ischemia by targeting A2B adenosine receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion - from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 2011;17:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/nm.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Eckle T, Kohler D, Lehmann R, El Kasmi KC, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Is Central to Cardioprotection: A New Paradigm for Ischemic Preconditioning. Circulation. 2008;118:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eckle T, Krahn T, Grenz A, Kohler D, Mittelbronn M, Ledent C, Jacobson MA, Osswald H, Thompson LF, Unertl K, Eltzschig HK. Cardioprotection by ecto-5'-nucleotidase (CD73) and A2B adenosine receptors. Circulation. 2007;115:1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Laucher S, Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor dampens hypoxia-induced vascular leak. Blood. 2008;111:2024–2035. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grenz A, Osswald H, Eckle T, Yang D, Zhang H, Tran ZV, Klingel K, Ravid K, Eltzschig HK. The Reno-Vascular A2B Adenosine Receptor Protects the Kidney from Ischemia. PLoS Medicine. 2008;5:e137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hart ML, Jacobi B, Schittenhelm J, Henn M, Eltzschig HK. Cutting Edge: A2B Adenosine receptor signaling provides potent protection during intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Immunol. 2009;182:3965–3968. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eckle T, Hartmann K, Bonney S, Reithel S, Mittelbronn M, Walker LA, Lowes BD, Han J, Borchers CH, Buttrick PM, Kominsky DJ, Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK. Adora2b-elicited Per2 stabilization promotes a HIF-dependent metabolic switch crucial for myocardial adaptation to ischemia. Nat Med. 2012;18:774–782. doi: 10.1038/nm.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Blum JM, Stentz MJ, Dechert R, Jewell E, Engoren M, Rosenberg AL, Park PK. Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of postoperative acute respiratory distress syndrome in a general surgical population. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:19–29. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182794975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gajic O, Dabbagh O, Park PK, Adesanya A, Chang SY, Hou P, Anderson H, 3rd, Hoth JJ, Mikkelsen ME, Gentile NT, Gong MN, Talmor D, Bajwa E, Watkins TR, Festic E, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kaufman DA, Esper AM, Sadikot R, Douglas I, Sevransky J, Malinchoc M. Early identification of patients at risk of acute lung injury: Evaluation of lung injury prediction score in a multicenter cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:462–470. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0549OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dulu A, Pastores SM, Park B, Riedel E, Rusch V, Halpern NA. Prevalence and mortality of acute lung injury and ARDS after lung resection. Chest. 2006;130:73–78. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Phua J, Badia JR, Adhikari NK, Friedrich JO, Fowler RA, Singh JM, Scales DC, Stather DR, Li A, Jones A, Gattas DJ, Hallett D, Tomlinson G, Stewart TE, Ferguson ND. Has mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome decreased over time?: A systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:220–227. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-722OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: A clinical review. Lancet. 2007;369:1553–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fan E, Villar J, Slutsky AS. Novel approaches to minimize ventilator-induced lung injury. BMC Med. 2013;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L, Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Landazury R, Eppanapally S, Christie JD, Meyer NJ, Ware LB, Christiani DC, Ryter SW, Baron RM, Choi AM. Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1225–1234. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: From the bench to the bedside. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:24–33. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]