Abstract

Promoter-associated RNAs (pRNAs) are a family of ~90–100 nt-long divergent RNAs overlapping the promoter of the rRNA (rDNA) operon. pRNA transcripts interact with TIP5, a component of the chromatin remodeling complex NoRC, which recruits enzymes for heterochromatin formation and mediates silencing of rRNA genes. Here we present a comprehensive analysis of pRNA homologs, including different versions per species, as result of in silico studies in available metazoan genome assemblies. Comparative sequence analysis and secondary structure prediction ended up in two possible secondary structures, which let us assume a possible dual function of pRNAs for regulation of rRNA operons. Furthermore, we validated parts of our computational predictions experimentally by RT-PCR and sequencing. A representative seed alignment of the pRNA family, annotated with possible secondary structures was released to the Rfam database.

Keywords: promoter-associated RNA, non-coding RNA, ribosomal RNA, gene silencing

Introduction

Promoter-associated RNAs (pRNAs) originate from an intergenic RNA polymerase I (Pol I) promoter located about 2 kb upstream of the pre-rRNA transcription start site.1 The intergenic transcripts are short-lived and degraded by the exosome, except a 150–250 nt transcript that matches the promoter of the ribosomal genes (rDNA), termed promoter-associated RNA.2 These pRNAs are stabilized by binding to TIP5 (transcription termination factor I interacting protein 5), the large subunit of the nucleolar remodeling complex NoRC, which mediates heterochromatin formation and transcriptional silencing.3 This interaction is a prerequisite for the function of NoRC, because antisense-mediated depletion of pRNA leads to decreased rDNA methylation and activation of Pol I transcription.1 The 5′ terminal part of pRNA is believed to recruit DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 3b to rDNA by forming a DNA:RNA triple helix and directing therewith DNA methylation.4,5 The release mechanism of the pRNA is regulated by the acetyltransferase MOF (males absent on the first), which acetylates a single lysine residue (K633) of TIP5 and leads to a dissociation of the pRNA from NoRC.6

pRNAs were previously described to fold into a specific stem-loop structure, which is recognized by TIP5. Its importance for binding to TIP5 was shown by mutation studies that prevented the formation of this structure and led to an abolishment of targeting NoRC to nucleoli.3 Besides some sequence predictions of rDNA promoter sequences in mammals (human, mouse, rat, rabbit, and pig), little is known about the distribution of pRNAs among different species.3

The Rfam seed alignment RF01518 currently lists sequences of 16 species. The full alignment contains 659 sequences from 25 species, including alveolata, which we show is unlikely true. Here, we present a set of pRNAs detected in 31 available eutherian genome assemblies and extended it by additional sequences from 11 species detected in EST and WGS databases. We show common features concerning the sequence, secondary structure, and syntenic regions, which lead to a possible regulatory function of pRNA by two possible secondary structures.

Results

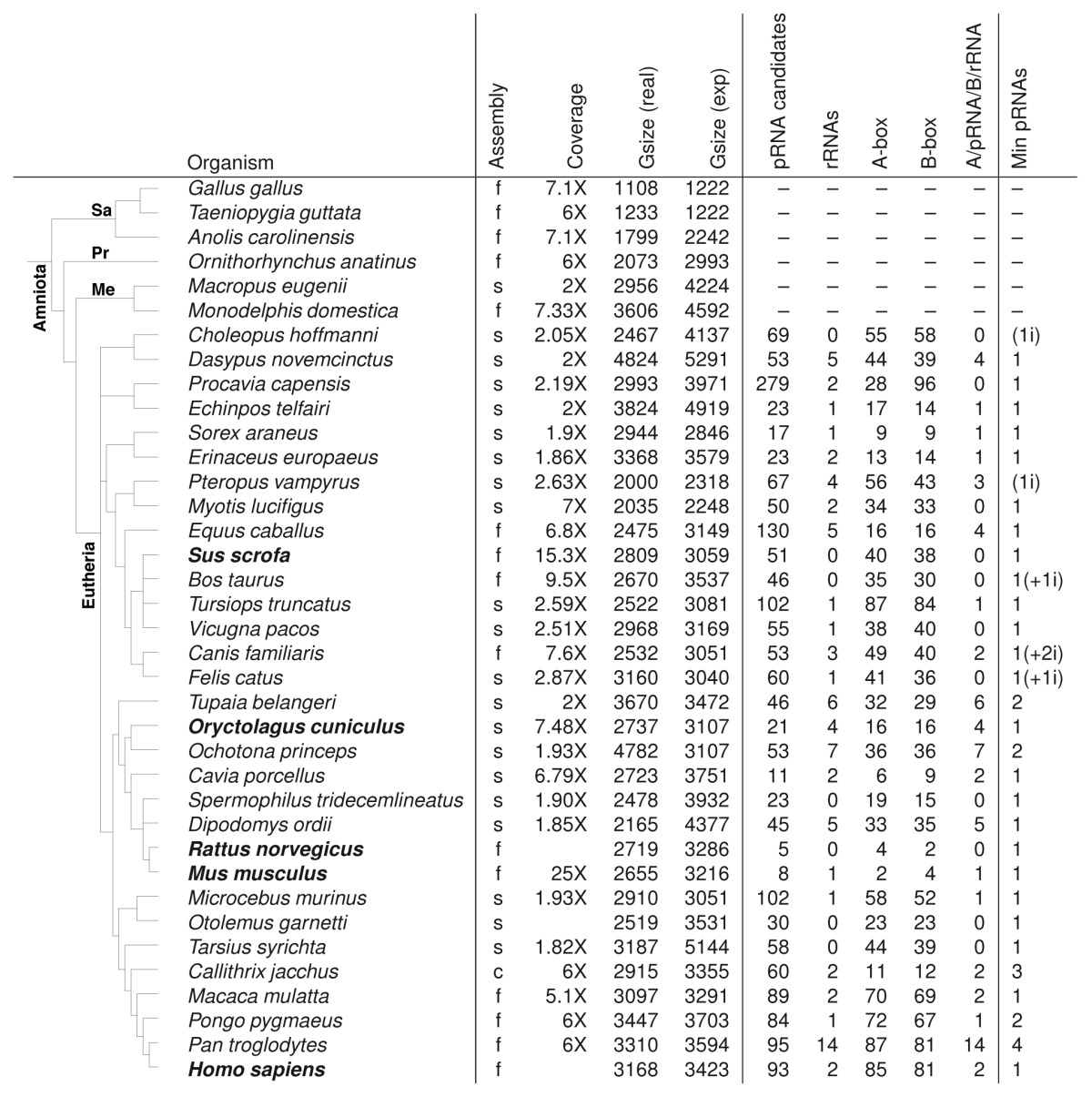

Homology search and phylogenetic distribution of pRNA

With the published pRNA sequences of Mayer et al.,3 including Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Oryctolagus cuniculus, and Sus scrofa, we performed a homology search with blast and infernal. As rDNA transcription is species-specific, there is little sequence homology among these sequences that are complementary to the the rDNA promoter.1,3 We searched automatically and manually in 37 Amniota genomes (new and old assemblies) for pRNAs, resulting in 1901 sequences from 31 eutherian genomes with 5–279 candidates per genome (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of pRNA candidates.

The number of pRNA candidates from the assembled (contig, scaffold or finished) genomes can be reduced, according to adjacent rRNAs, A-box (part of UCE) and B-box (part of core promoter) in expected distances to pRNA candidates. We suggest a number of minimal pRNAs believed to be functional (Min pRNAs), derived from unique sequences of genome analysis, EST sequences and candidates from previous genome assemblies. Additionally, we found pRNA candidates for eleven more species: Gorilla gorilla, Nomascus leucogenys, Pongo abelii, Macaca fuscata, Macaca fascicularis, Cricetulus griseus, Cricetulus longicaudatus, Canis lupus familiaris, Pseudorca crassidens, Bubalus bubalis, and Muntiacus muntjak vaginalis. For more details see main text. f, finished; s, scaffold; c, contig; Gzise, Genomesize in Mbp; pRNA candidates, in current assembly; rRNAs, number of rRNAs within 10 000 nt downstream of pRNA candidates; i, candidates with unexpected insertion in upstream sequence; Sa, Sauropsida; Pr, Protheria; Me, Metatheria; known sequences in bold font.

No candidates were detected in Sauropsida, Protheria, and Metatheria, which clearly shows the invention of pRNAs correlated with the development of Eutherians. All sequences have roughly the same length (91–98 nt). Most trustable sequences (little variations to initial known pRNAs) showed ∼24 nt upstream and 39 nt downstream of pRNA highly conserved regions (A-box/B-box). We used this information and an intensive rRNA search to determine which of our candidates are likely to be functional and which of them are possible pseudogenes. We defined a possible pRNA to be functional, if the conserved upstream located A-box, the conserved downstream located B-box and the further downstream located rRNA operon are present. Finally, we found in all of the 31 eutherians at least one copy being highly possible functional. Whenever multiple copies of pRNA of a genome (including conserved boxes) are identical, we report a minimum of one copy to be functional due to possible assembly errors.

Furthermore, we searched in NCBI databases, like “expressed sequences tags (est)” and “whole-genome shotgun contigs (WGS).” For 11 more species we were able to detect homologous pRNA sequence candidates: Gorilla gorilla, Nomascus leucogenys, Pongo abelii, Macaca fascicularis, Macaca fuscata, Cricetulus griseus, Cricetulus longicaudatus, Canis lupus familiaris, Pseudorca crassidens, Bubalus bubalis, and Muntiacus muntjak vaginalis.

The alignment of all 42 most likely functional sequences (including A/B-box) is shown in the online supplemental material. The alignment shows a very variable pRNA sequence (40–73% identity to consensus sequence). The exact start and stop position of the functional pRNA remains unclear; however, according to secondary structure searches and conservation visualized with Emacs Ralee mode, the assumed limits are indicated in the alignment. The start site of the Rfam alignment was confirmed with a difference of 1nt with our assumed 5′ end, whereas our assumed 3′ end is located 8 nt downstream of the proposed Rfam sequences.

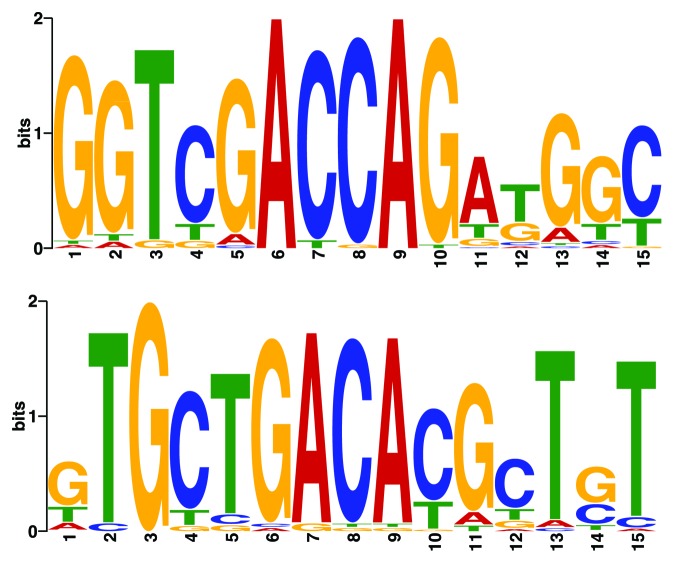

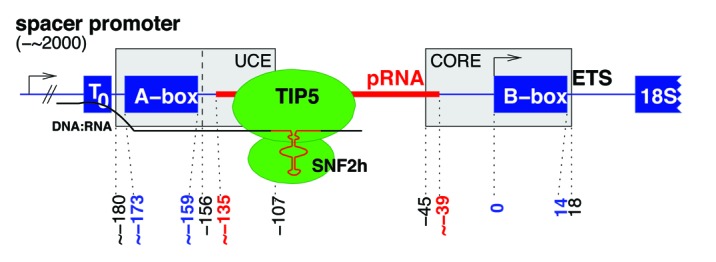

Conserved motifs in syntenic regions

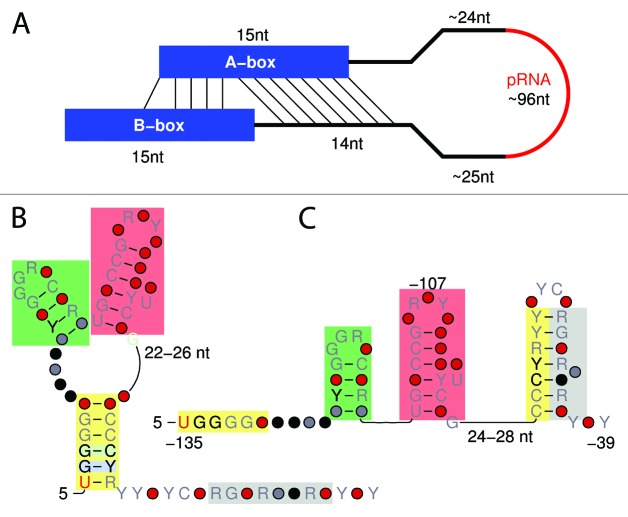

The most strikingly conserved motifs were found in the syntenic regions in a distance of approximately 24 nt upstream and 39 nt downstream of the pRNA sequences, see Figure 1. Interestingly, these motifs being not part of the Rfam alignment, which are detectable in all species, are close to or overlapping with two major control elements of the rDNA promoter, namely the upstream control element (UCE) and the core element,7 see Figure 2. The upstream motif GGTCGACCAGA TGGC (A-box, Figure 1-top) is located directly upstream to the UCE according to,7 or alternatively, overlapping with UCE in the common sense. The downstream motif GTGCTGACAC GCTGT (B-box, Figure 1-bottom) and the core element are overlapping. In all 42 species the combination A-box-pRNA-B-box was observed. Some of them contained a genomic insertion between A-box and pRNA. The numbers of detected A- and B-boxes were in most of the available genomes similar to each other (Table 1). The here mentioned motifs are not part of the current Rfam alignment, however are as main characteristics part of our provided alignment.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of a pRNA in genomic context and its interaction partners. The promoter associated RNA (red, 96 nt) is located upstream of the rRNA operon and surrounded by two highly conserved regions of 15 nt each: The A-box (-173–-159 nt) is located 24 nt upstream of the pRNA and overlaps the common Upstream Control Element (UCE, -180–-107 nt), itself overlapping partly with the pRNA. According to Haltiner et al., the UCE is located downstream of the A-box (-156–-107 nt).7 The B-box (0–14 nt) is initiated with the Transcription Start Site and is part of the core (-45–18 nt).7 Positions according to human pRNA sequence and with respect to the Pol I transcription start site. When the pRNA binds to TIP5 and T0, methylation of the rDNA promoter is increased and the rDNA gene is silenced. A DNA:RNA triplex helix of the premature pRNA transcript is formed at T0.

Figure 2. Highly conserved boxes were detected ~24 nt upstream (top, A-box) and ~39 nt downstream (bottom, B-box) of pRNAs. The upstream A-box is part of the highly conserved UCE, whereas the downstream B-box is part of the promoter core region.

Secondary structure

When folding all here retrieved pRNAs and their surrounding conserved boxes with various in silico methods, we retrieved one striking interaction. We observed an interaction of A-box and the B-box-area, see Figure 3A. This interaction is highly conserved in all metazoans, with a high average energy value (-7.32 kcal/mol), compensatory mutations, and nearly no variations in length (14 nt). Doubts about the secondary structure of the pRNA itself remain: Mayer et al.3 reported that the pRNA folds into a conserved stem-loop structure that is necessary for nucleolar localization and rDNA silencing. This hairpin structure is also presented in the current Rfam entry based on this publication.3 Therefore, we tested if all of our predicted pRNA sequences are also able to fold into this specific structure by using RNAsubopt and constraint options. We found this possibility for all of the pRNA candidates, nevertheless, for most pRNAs this is only possible with unfavorable energy values, which is possible just by chance for any sequence of the same length and dinucleotide distribution. Therefore, we performed extensive secondary structure analyses and found two possible secondary structures being valid for all detected pRNAs, which are displayed in Figure 3B and C. Both secondary structures hold two hairpins of about 6 nt. The first hairpin and half of the second hairpin are part of the UCE. In one of the two cases (Fig. 3B), the two hairpins are part of a multi-loop. In the other case, a third hairpin is formed (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Secondary structure of the promoter of an rDNA operon. (A) A-box and B-Box (blue) are interacting highly conserved for all metazoan animals. The pRNA itself (red) of all here reported sequences can fold into two possible secondary structures (B and C). The first hairpin (green box) and half of the second hairpin (red box) are part of the UCE (-180/-156–-107 nt). Color boxes represent interacting regions of pRNAs colored identical in (B and C). Promoter-associated RNAs may fold into one of the structures depending on their interaction to NoRC.

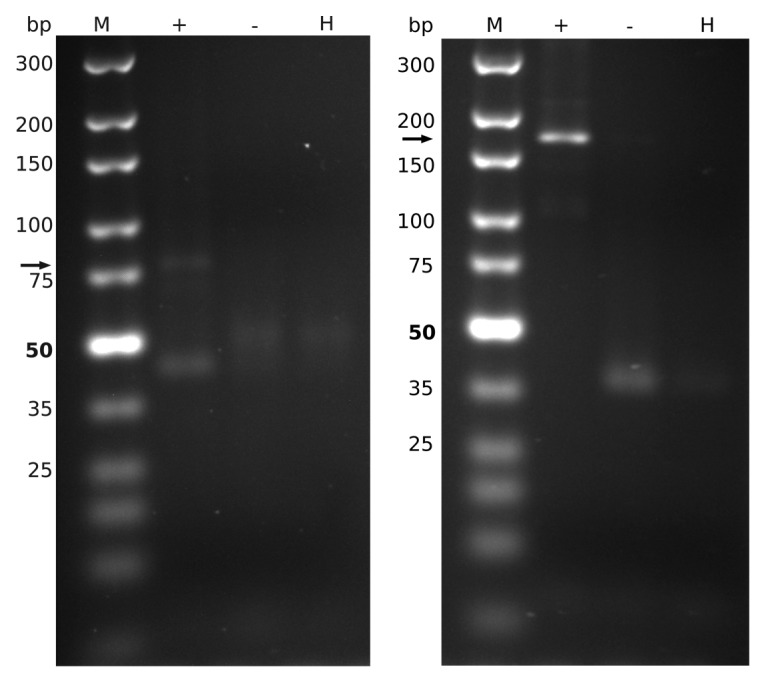

Experimental verification

Promoter-associated RNAs were previously described in vitro in mouse and human.3 Here, we decided to verify our bioinformatical results by an experimental approach. We selected Vicugna pacos, being evolutionary not too close and not far away from the two already characterized sequences of M. musculus and H. sapiens, in order to retrieve a positive and interesting result. By performing RT-PCR with specific primers for the pRNA itself as well as for the conserved boxes up- and downstream of the pRNA (which are also transcribed) we could verify our predicted pRNA experimentally (Fig. 4). Additionally, we sequenced the PCR product, which was in conformation with our predicted pRNA sequences. For Oryctolagus cuniculus and Pongo pygmaeus we also verified the PCR-product in sequence with the predicted sequence (see Supplemental Materials).

Figure 4. Validation of a pRNA candidate in Vicugna pacos. RT-PCR was performed with the cDNA of the pRNA itself (left, 76 nt expected, arrow) and with the conserved boxes (right, 164 nt expected, arrow). M, Marker; +, c-DNA; -, negative control; H, water control.

Discussion

When inspecting Table 1, there is obviously often a large difference between the number of putative pRNAs and the assumed minimal number of pRNAs, because most pRNA candidates do not show an rRNA sequence in the downstream region in current assemblies, which lack most rRNA operon copies in eukaryotic genomes. In conclusion, there might be many more functional pRNA genes in the genomes. On the other hand, when a genome is released on contig level, many detected copies may refer to only one real gene (no mutations among various copies and their upstream and downstream region) on the originating genome (e.g., in O. cuniculus). For S. scrofa and closely related species, our blast search failed because of low sequence homology of the pRNA sequences. Consequently, the conserved up- and downstream region are essential to describe and find pRNAs in whole genomes. Especially when searching for either repeats, genes close to repeats or genome fragments containing telomere regions, centromere regions, or rRNA operons, searching in older assemblies, even being “only” on scaffold or contig level can be a huge contribution.

Therefore, the strategy to find more pRNAs should be significantly different from a normal covariance model search (such as infernal e.g., used for the current Rfam pRNA class): (1) search in older assemblies containing more information about rDNA operons; (2) search with syntenic information, such as surrounding highly conserved upstream and downstream regions.

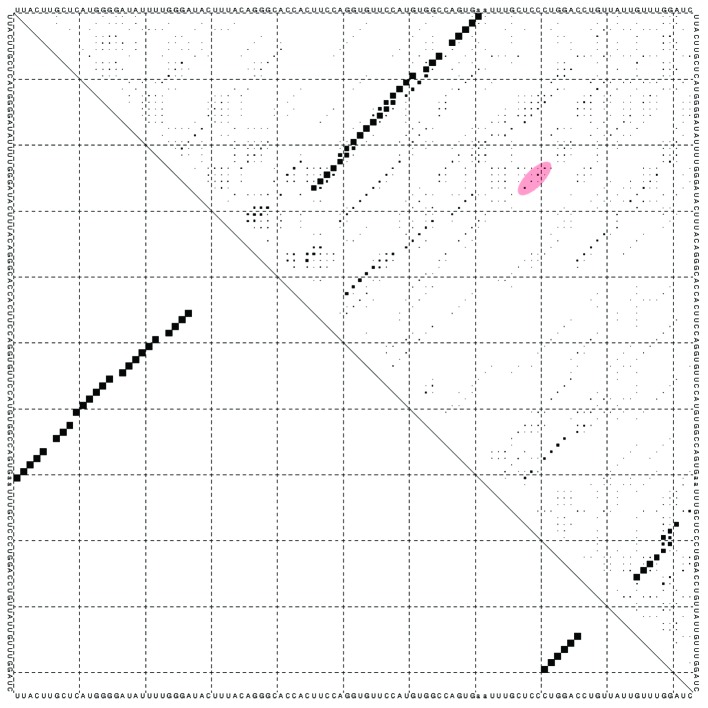

We were able to detect pRNAs for all Eutherians. We assume organisms with pRNAs use different strategies (compared with organisms without pRNAs) to regulate rDNA gene transcription, and thus, would give new insights in heterochromatin formation and rDNA silencing. The conserved boxes being close to or part of UCE and core promoter region seem essential to functional pRNAs. This is especially interesting as at active genes, wrapping of promoter sequences around the nucleosomes places the core element and the UCE side by side, whereas at silent genes both promoter elements are in a different translational position and do not allow cooperative binding of UBF and TIF-IB/SL1.5 The interaction of A-box and B-box region seems essential for this regulation. Additionally, the two possible secondary structures of the inner part show a possible dual function of pRNAs, which may switch depending on the interacting proteins. The supposed secondary structure of Mayer et al.3 cannot be supported by our analysis. The supposed interaction of GGG and CCC (Fig. 5, red circle), is supported by only a small probability. This may refer to pRNA–protein interactions, which are not predictable yet.

Figure 5. Dotplot of pRNA secondary structure of Mus musculus. The supposed interaction GGG:CCC (red circle) of3 is rather unlikely, when not taking protein-pRNA interaction into account.

Interestingly, in Bos taurus we were able to find two very different pRNA candidates, containing conserved syntenic regions and a downstream rDNA operon. The two pRNAs fold into different secondary structures, for one of them the interaction of the conserved syntenic boxes is not very stable. The final meaning of such two systems for the organism remains unclear and needs further investigations and experiments.

Materials and Methods

All input and output data, genome composition,8 secondary structures, and alignments are available in the supplemental material http://www.rna.uni-jena.de/supplements/prna.

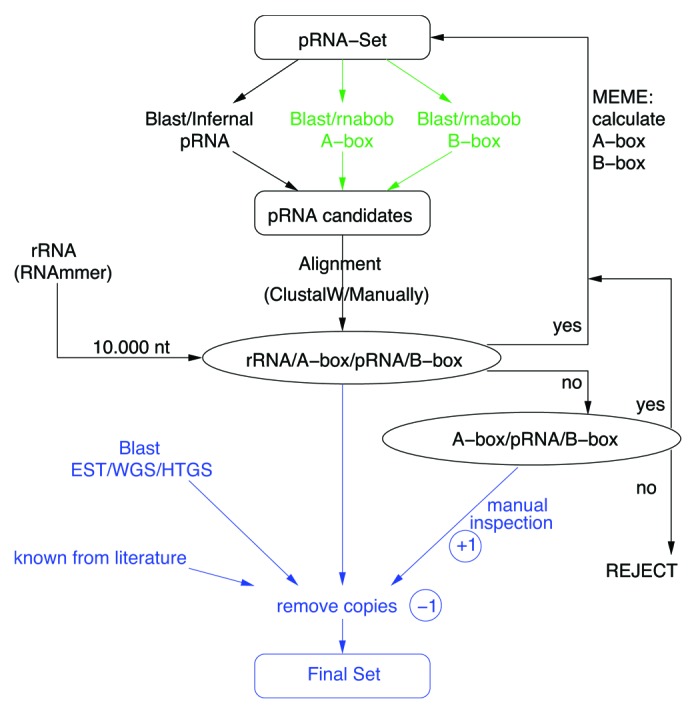

Homology search for pRNA

As input for the homology search we used the alignment of the five known mammalian pRNAs Sus scrofa, Oryctolagus cuniculus, Rattus norvegicus, Mus musculus, and Homo sapiens.3 For each species, we performed blastn searches9 using an E-value of < 10−4. Hits were extended and aligned with ClustalW.10 Subsequently, the alignments were manually viewed, evaluated, and changed. When the sequences were approved as possible pRNAs, they were additionally and iteratively used as input for another blastn step, see Figure 6. We repeated this step until no new trustable sequences were obtained. Furthermore, homology searches for upstream and downstream regions (300 nt) were performed independently. For each organism, we obtained multiple pRNA candidates. The one candidate with conserved boxes upstream and downstream as well as an rRNA operon nearby was chosen for the final multiple alignment. Additionally, we searched for more pRNAs in older assemblies, and on NCBI in databases “NR,” “EST,” “WGS,” and “HTGS.” We added them to the final alignment.

Figure 6. Pipeline for detection of pRNAs. pRNAs are searched by homology and aligned. New candidates (passing the conservation and synteny filter) are used additionally and iteratively as input for the next search step (black). For each next search iteration a MEME-derived motif for A-box and B-box is used independently (green). We repeated these steps until no new trustable sequences were obtained. In the end (blue), the promising candidates, homologous sequences from NCBI databases EST, WGS or HTGS, as well as described pRNAs from the literature are taken together and copies are removed. The final pRNA-set is presented in the last column of Table 1 and in detail in the Supplemental Material. Parameters are given in main text.

With MEME11 -minw 10 -maxw 20 -minsites 18 we found conserved motifs within 100 nt up- and downstream of pRNA. A separate search for these motifs using rnabob12 (mutations upstream:4, downstream:9) was performed. These motifs and their expected distance of 157‒177 nt were also used for pattern specific searches with fragrep.13

This alignment with consensus sequences as well as the final alignment is provided at the supplemental page, at which also gff and fasta files of the pRNAs and information about the corresponding rDNAs for each species can be found.

Detection of rRNA genes

In order to see if our pRNA candidates are located upstream to an RNA operon, we annotated rRNAs using RNAmmer (v.2.1)14 with the parameters -S euk -m lsu, ssu, tsu -gff. We listed in the supplement all detected rRNAs within 10 000 nt downstream of potential pRNAs.

Secondary structure analysis

We analyzed the secondary structures of the sequences of our final multiple alignment and tested, if all candidates are able to fold into the reported structure of the literature. We used RNAsubopt15 and RNAfold16 with constraints. For alignments, including also the secondary structure information, we used RNAalifold,17 Locarna,18 and locarnate.19 The resulting stockholm alignment was used to build a pRNA specific covariance model with infernal.20 With this model, we searched with standard parameters against genomes, for which no pRNA sequence was previously detected. Furthermore, this alignment was used to construct the consensus secondary structures with R2R.21

Experimental verification

Cell culture and RNA isolation

Cell cultures from orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) kidney, domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus forma domestica) pancreas and from alpaca (Vicugna pacos) placenta were provided by the “German Cell Bank for Wildlife” (www.cryo-brehm.de). The cells were propagated in Dulbeccos modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum “GOLD” (PAA Laboratories), Penicillin (100 U/ml) and Streptomycin (0.1 mg/ml) using 75 cm2 T-flasks (PAA Laboratories) at 37 °C in 5% index 2 humidified atmosphere. The cells were detached using a 0.05% trypsin/EDTA solution (PAA Laboratories). The cell suspension was transferred into culture medium and centrifuged with 800 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was removed and RNA isolated fully automated using the QIAcube instrument (Qiagen) together with Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini spin column kit according to the manufacturers protocols. The RNA solution was stored in a freezer at -80 °C until use.

RT-PCR

Three hundred ng of total RNA were reverse-transcribed with SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen) using specific primers (see Supplemental Materials). Sixty ng of the resulting cDNA were used as template for PCR analysis. PCR reactions were performed with either DreamTaq™DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific) or Phusion® High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific) based on the manufacturers procedure for a total of 30 cycles. The amplification products were cloned into the pJET1.2/blunt cloning vector (Thermo Scientific). Positive recombinant clones were identified by colony PCR. Plasmids from these clones were isolated using the QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit and sequenced with the pJET1.2 FW sequencing primer (Thermo Scientific). The obtained and the deduced nucleotide sequences were compared using the ClustalW software.

Author: Please include in-text citation for reference 21.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Submitted Data

This manuscript documents the seed alignment pRNA1.seed.stk.

Acknowledgments

MM was funded by the Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung. This work was supported in part by DFG-Graduiertenkolleg 1384 “Enzymes and multienzyme complexes acting on nucleic acids” and DFG MA5082/1–1.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/rnabiology/article/27448

References

- 1.Mayer C, Schmitz K, Li J, Grummt I, Santoro R. Intergenic transcripts regulate the epigenetic state of rRNA genes. Molecular Cell 22, 2006351-361. ISSN 1097-2765. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Santoro R, Schmitz KM, Sandoval J, Grummt I. Intergenic transcripts originating from a subclass of ribosomal DNA repeats silence ribosomal RNA genes in trans. EMBO Rep. 2010;11:52–8. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer C, Neubert M, Grummt I. The structure of NoRC-associated RNA is crucial for targeting the chromatin remodelling complex NoRC to the nucleolus. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:774–80. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grummt I. Wisely chosen paths--regulation of rRNA synthesis: delivered on 30 June 2010 at the 35th FEBS Congress in Gothenburg, Sweden. FEBS J. 2010;277:4626–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grummt I, Längst G. Epigenetic control of RNA polymerase I transcription in mammalian cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:393–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Schmitz KM, Mayer C, Yuan X, Akhtar A, Grummt I. Reversible acetylation of the chromatin remodelling complex NoRC is required for non-coding RNA-dependent silencing. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1010–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haltiner MM, Smale ST, Tjian R. Two distinct promoter elements in the human rRNA gene identified by linker scanning mutagenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:227–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregory TR. Animal Genome Size Database, 2012. http: //www.genomesize.com

- 9.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215, 1990403-410. ISSN 0022-2836. 10.1006/jmbi 1990.9999. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Research 22, 1994:4673-4680. ISSN 0305-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. MEME discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Research 34, 2006W369-W373. ISSN 0305-1048. 10.1093/nar/gkl198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Eddy RNABOB Sr. a program to search for RNA secondary structure motifs in sequence databases, 1992-1996. http: //selab.janelia.org/software.html

- 13.Mosig A, Sameith K, Stadler P. Fragrep: an efficient search tool for fragmented patterns in genomic sequences. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2006;4:56–60. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(06)60017-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rodland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. NUCLEIC ACIDS RESEARCH 35, 20073100-3108. ISSN 0305-1048. { 10.1093/nar/ gkm160}. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wuchty S, Fontana W, Hofacker IL, Schuster P. Complete suboptimal folding of RNA and the stability of secondary structures. Biopolymers 49, 1999145-165. ISSN 0006-3525. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(199902) 49:2<145:AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Hofacker IL, Fontana W, Stadler PF, Bonhoeffer LS, Tacker M, Schuster P. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatshefte f ür Chemie Chemical Monthly 125, 1994167-188. ISSN 0026-9247. 10.1007/BF00818163 [DOI]

- 17.Hofacker IL. RNA consensus structure prediction with RNAalifold. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;395:527–44. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-514-5_33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Will S, Reiche K, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Backofen R. Inferring noncoding RNA families and classes by means of genome-scale structure-based clustering. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otto W, Will S, Backofen R. Structure local multiple alignment of RNA. In Proceedings of German Conference on Bioinformatics (GCB’2008), volume P-136 of Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI). Gesellschaft für Informatik (GI), 2008. ISBN 987-3-88579-230-7. ISSN 1617-5468, 178-188.

- 20.Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0 inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics 25, 20091335-1337. ISSN 1367-4803. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Weinberg Z, Breaker RR. R2R--software to speed the depiction of aesthetic consensus RNA secondary structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]