Abstract

The effect of Parkinson’s disease on hand-eye coordination and corrective response control during reach-to-grasp tasks remains unclear. Moderately impaired Parkinson’s disease patients (PD, n=9) and age-matched controls (n=12) reached to and grasped a virtual rectangular object, with haptic feedback provided to the thumb and index fingertip by two 3-degree of freedom manipulanda. The object rotated unexpectedly on a minority of trials, requiring subjects to adjust their grasp aperture. On half the trials, visual feedback of finger positions disappeared during the initial phase of the reach, when feedforward mechanisms are known to guide movement. PD patients were tested without (OFF) and with (ON) medication to investigate the effects of dopamine depletion and repletion on eye-hand coordination online corrective response control. We quantified eye-hand coordination by monitoring hand kinematics and eye position during the reach. We hypothesized that if the basal ganglia are important for eye-hand coordination and online corrections to object perturbations, then PD patients tested OFF medication would show reduced eye-hand spans and impoverished arm-hand coordination responses to the perturbation, which would be further exasperated when visual feedback of the hand was removed. Strikingly, PD patients tracked their hands with their gaze, and their movements became destabilized when having to make online corrective responses to object perturbations exhibiting pauses and changes in movement direction. These impairments largely remained even when tested in the ON state, despite significant improvement on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Our findings suggest that basal ganglia-cortical loops are essential for mediating eye-hand coordination and adaptive online responses for reach-to-grasp movements, and that restoration of tonic levels of dopamine may not be adequate to remediate this coordinative nature of basal ganglia modulated function.

Keywords: Reaching, Grasping, Online Corrections, Dopamine-replacement, Eye-hand Coordination

INTRODUCTION

The ability to continuously adapt motor commands to meet task demands is essential to successful interactions in dynamic environments. Online correction of hand movements to grasp a moving object require complex eye-hand coordination. The brain must analyze visual input about the object and the environment, analyze proprioceptive input from the limb, head, and eyes, update its representations in relation to dynamic changes of the environment and the arm, and issue appropriate and precisely timed motor commands. Parieto-frontal circuits mediate reaching (Marconi et al. 2001) and grasping (Rizzolati et al. 2003). The posterior parietal cortex is critical for on-line visuomotor control (Frey et al. 2005; Rice et al. 2006), particularly in response to perturbations either of a target to be reached for (Desmurget et al. 1999; Torres et al. 2010) or an object to be grasped (Tunik et al. 2005, 2008a, 2008b). Disruption of activity within the anterior intraparietal sulcus (aIPS) by transcranial magnetic stimulation, for example, selectively interferes with subjects’ ability to adjust their grasp to sudden perturbations in an object’s size or orientation (Tunik et al. 2005). However, the role of basal ganglia-cortical circuits and dopaminergic pathways in such on-line visuomotor control is poorly understood. Evaluating the behavioral output of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients presents a unique opportunity to indirectly investigate these issues, since death of midbrain dopaminergic cells results in marked alterations in basal ganglia modulation of frontal cortical activity, leading to the core deficits in motor planning and execution seen in PD (Rodriguez-Oroz et al. 2009).

Two deficits particularly implicated in PD are the inability to assemble complex motor actions that include multiple movement components and the difficulty in producing accurate movements that are internally generated rather than visually guided (Rodriguez-Oroz et al. 2009). Previous work has shown that PD patients exhibit deficits in the generation of intentional saccades to targets (Crawford et al. 1989; Briand et al. 1999) and difficulties in the initiation and precise control of internally driven arm movements (Flowers 1976; Georgiou et al. 1993; Adamovich et al. 2001). Moreover, the temporal coupling of the hand and arm is impaired in PD during reaching for and grasping objects differing both in size and shape (Castiello et al. 1994; Schettino et al. 2004, 2006). These deficits are exacerbated when vision of the hand is blocked (Rand et al. 2010; Schettino et al. 2006; Lee et al. in press).

Furthermore, the interplay of reaching and grasping with gaze behavior and eye-hand coordination is unknown. Patterns of eye-hand coordination become particularly important when subjects must adapt their hand movements during the reach to a perturbation of the object to be grasped. Boisseau et al. (2002) suggested that the nature of eye-hand coordination control was no different between PD patients and controls after finding no performance differences in a pointing task. However, they did not directly record eye movements and the movement profiles of the hand in space were not reported. While eye-hand coordination and intersegmental coordination are considered central features of cerebellar function (Thach et al. 1992; Miall and Reckess 2002), basal ganglia circuits may also play a very important role. Differentiated, parallel, and largely segregated cortical-subcortical reentrant circuits link specific cortical areas with their corresponding regions in the basal ganglia (Alexander et al. 1986, 1990). Precise, differentiated function within and across these topographically separated circuits may facilitate the integration of different brain regions needed for coordinated motor output. The integrity of these circuits also may be critical for gating afferent input to cortical motor areas in a context-sensitive manner (Schneider et al. 1982; Lidsky et al. 1987; West et al. 1987) and, thus, critical for the context-dependent adaptive control of movement. Under conditions of dopamine depletion, fronto-basal ganglia circuits become pathologically synchronized and “locked-in” at the beta band frequency (Jenkinson and Brown 2011), potentially reducing the ability of the circuits to appropriately update an ongoing action in response to an environmental perturbation.

Dopaminergic therapy is the most common and effective treatment for motor deficits in PD (Sage and Mark 1994; Hagan et al. 1997). Previous electrophysiological data have shown that increasing tonic dopamine levels improves the desynchronization of activity over cortical motor areas prior to and during hand and arm movements, correlating with increases in movement speed (Wang et al. 1999). However, our lab and others have found that dopaminergic therapy does not have a unidimensional effect on movement but rather reverses deficits in what we have termed ‘intensive’ aspects of movement (e.g., speed or amplitude) to a greater extent than deficits in ‘coordinative’ aspects such as hand-arm coordination (Johnson et al. 1994, 1996; Schettino et al. 2006; Levy-Tzedek et al. 2011), hand-posture coordination during trunk-assisted reaching (Tunik et al. 2007; Rand et al. 2010), and multi-segmental coordination during walking while holding an object (Albert et al. 2010). It is currently unknown, however, what effects dopamine repletion may have on visuomotor online corrective responses to object perturbations and on associated eye-hand coordination for reach-to-grasp movements.

To examine the effect of Parkinson’s disease on eye-hand coordination and online corrective responses, we compared PD patients and age-matched controls in reaching for and grasping a virtual rectangular object with visual and haptic feedback, while simultaneously recording finger, thumb, and eye movements. On a subset of trials, the to-be-grasped object rotated mid-reach such that subjects had to dynamically adapt their finger trajectories to successfully grasp the object. In addition, on half of the trials, visual feedback of finger positions disappeared during the feedforward phase of movement, forcing reliance on internal rather than external guidance of the movement.

We hypothesized the following: First, that healthy subjects would rapidly and smoothly alter their finger trajectories to enable a successful grasp in the face of unexpected perturbations of the object. In contrast, if the basal ganglia are critical nodes in a network mediating the flexible and adaptive visuomotor responses to altered environmental contexts, perturbation of the object should have a detrimental effect on the finger trajectories of the PD patients. Second, we hypothesized that due to PD patients’ over-reliance on visual feedback to monitor and correct movement errors, their gaze would be aligned with their finger positions to a greater extent than in the control group. Given this reliance on visual feedback, we also hypothesized that blocking vision of the hand would have a much more detrimental effect on the movements of the PD patients than on the control subjects. Finally based on prior results, we hypothesized that increasing tonic dopamine levels through dopaminergic therapy would increase reach speed and aperture of hand opening (i.e., intensive measures), but would not reverse online grasp correction deficits or deficits in eye-hand coordination (i.e., coordinative measures).

METHODS

Participants

Nine PD patients (6 female) and 12 age-matched normal older adults (4 female) participated in this study (Mean ± SD age: PD patients, 62.8 ± 8.4 years; controls, 65.7 ± 9.8 years; t = 0.72, p > .05). All patients had mild to moderate clinically typical PD (Hoehn and Yahr (1967) stages 2 and 3), and their motor disabilities were responsive to anti-Parkinsonian medications. No patient had marked resting tremor, action tremor, or dyskinesias. Moreover, no patient had dementia or major depression (screened with the Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein et al. 1975) and Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al. 1961). No participant had any neurological or psychiatric disease in addition to PD for the PD participants. All participants were right-handed (Oldfield 1971) with normal or corrected to normal vision. Clinical characteristics of the PD patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of Parkinson’s disease patients.

| Patient ID |

Sex | Age (years) |

Disease duration (years) |

UPDRS (ON/OFF) |

H&Y Stage (ON/OFF) |

Medications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD01 | F | 65 | 8 | 20, 39 | 2, 2 | Carbidopa/Levodopa, Pramipexole |

| PD02 | M | 70 | 17 | 47, 52 | 3, 3 | Carbidopa/Levodopa, Amantadine, Selegiline |

| PD03 | M | 47 | 7 | 42, 58 | 3, 3 | RopiniroleXL, Selegiline, Rasagiline |

| PD04 | F | 70 | 7 | 30, 38 | 2, 2 | Selegiline HCL, Parmipexole |

| PD05 | F | 68 | 3 | 22, 28 | 3, 2 | Rasagiline, Carbidopa/Levodopa |

| PD06 | F | 69 | 9 | 31, 37 | 3, 3 | Carbidopa/Levodopa, Amantadine, Selegiline, Parmipexole, CoQ10, Vit.E |

| PD07 | F | 66 | 4 | 36, 44 | 3, 3 | Carbidopa/Levodopa, Pramipexole, Rasagiline |

| PD08 | M | 58 | 12 | 37, 41 | 2, 3 | Carbidopa/Levodopa/Entacapone; Rasagiline |

| PD09 | F | 52 | 9 | 33, 43 | 3, 3 | Carbidopa/Levodopa, Rasagiline, Amantadine, RopiniroleXL |

PD patients were tested on and off their anti-Parkinsonian medications in counterbalanced order on separate days. For off medication testing, patients were tested in the morning before taking their first medications of the day and having not taken their anti-Parkinsonian medication for at least 12 hours (Defer et al. 1999). Prior to testing, a trained individual administered the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) to each patient to provide a clinical measure of disease severity. All participants signed the informed consent document approved by the human subjects Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Diego.

Experimental setup

Haptic interaction

Two haptic robots with 3 degrees of freedom (Phantom Premium 1.0, Geomagic, Wilmington, MA, USA) sat facing each other such that subjects could insert the tips of their thumb and index finger into thimble gimbals affixed to the left and right robot, respectively (see Figure 1). The robots passively tracked subjects’ digits during the reach. When the digits made contact with the virtual object as seen on the monitor, the robots’ motors activated and applied an opposing force as if a real object was being touched. The haptic robots allowed precise manipulation of the timing and magnitude of object rotation and were extremely accurate spatially (resolution of 0.03 mm) and temporally (data collected at 1000 Hz with a 1ms latency) (Snider et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Experimental Setup.

Panel A illustrates the experimental setup using eye-tracking hardware (Eyetrack 1000), haptic robots (Phantom robots), and the virtual-reality environment used for the experiment. A computer monitor was used to display the virtual object, visual feedback of the subject’s digits in space, and a speed meter depicting the speed of the previous reach. Panel B is a diagram illustrating the object shape during unperturbed (upper diagram) and perturbed (lower diagram) trials, which consisted of a 90-degree rotation of the object in the frontal plane. Reaching movements during were performed in either full vision (FV) or blocked vision (BV) conditions. Panel C shows the temporal representation of a trial. An audio-visual cue was used to indicate the start of the movement. In the BV condition, vision of the hand was removed at the onset of movement and returned when the hand was 2/3rds to the distance to the object. In perturbed trials, object rotation occured at 20–40% of the reaching movement. During grasp, force feedback was provided by the haptic robots as well as a visual color cue indicating that the object was touched (good for good grasp, red for bad grasp; see Methods), at which point participants were free to return to the starting position and await the next trial.

Eye Tracking

A table-mounted eye-tracker (EyeLink 1000, SR Research, Kanata, Ontario, Canada),placed between the subject and robots, recorded eye movements at 1000 Hz. A tower mount elevated the eye-tracking device so that it did not restrict or interfere with the arm and hand movements. The EyeLink 1000 received a pulse from the shared data collection computer to assure temporal alignment of hand and eye data (see below). The two dimensional position of the eye on the monitor had a nominal accuracy of 0.25 – 0.5 degrees.

Virtual Reality Software

Custom scripts (Vizard, WorldViz LLC, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) developed to visualize the digits’ movements superimposed on the virtual scene, also coordinated the timing of the data streams from all components. The virtual environment contained a translucent, virtual table with a checkerboard pattern to aid depth perception. To increase realism, a picture of the room behind the screen was the background of the stimuli. The fingertips were represented by two white spheres 0.4 cm in radius, which cast a virtual shadow straight ‘down’ in the virtual environment onto the checkerboard table, to further aid depth perception. The haptic interaction with the virtual object occurred at the geometric center of the cursor sphere. Since the robots had three degrees of freedom (Euclidean x,y,z), the cursor spheres did not rotate. A detailed description of the virtual reality system and the method for temporally aligning all data streams can be found in Snider et al. (2011). High-density electroencephalographic (EEG) data was collected simultaneously and will form the basis of a separate report.

Protocol

Participants reached to and grasped a rectangular object (3.5 × 8.5 × 6 cm; Figure 1) with the thumb and index finger of their right hand. Participants placed their digits on a virtual starting dock, with the object located 13–18 cm away in the virtual environment. Participants had haptic as well as visual feedback of the dock so that they felt their hands resting on a solid surface. At the sound of a tone, participants reached toward the object at a comfortable speed and grasped the left and right sides of the object with their thumb and index finger, respectively. Participants had ample time to familiarize themselves with the environment and task requirements prior to the experiment.

Participants performed reach-to-grasp movements for 144 trials (4 blocks of 36 trials). The object perturbation occurred on 33% of these trials by rotating it 90 degrees in the frontal plane, thereby making the object appear horizontal. The perturbation occurred at a randomly jittered distance of 20–40% between the starting dock and the front of the object (Figure 1). The goal of the task remained the same regardless of the object orientation: to grasp along the left and right sides of the object. Therefore, participants had to adjust their grasp dynamically to a larger precision grip during perturbation trials. Finally, full visual feedback of the fingertips on the monitor was present in half of the trials in each block. In the other half of the trials, pseudo-randomly selected, no visual feedback of the fingertips was present until the hand reached 2/3rds of the distance to the object. The exact distance at which visual feedback of the fingertips appeared was randomly jittered half a centimeter around the 2/3rds distance point to help prevent anticipatory responses. The intermingling of all trial types (unperturbed, perturbed, blocked vision, full vision) within blocks of trials further helped reduce any anticipatory responses. Blocked visual feedback of the hand during the first 2/3rds of the movement forced participants to internally generate and guide the movement during the feedforward planning phase of the movement; visual feedback was provided only during the visual correction phase of the movement as the hand approached the object. The trial sequence contained an equal number of object perturbation trials with full and blocked vision, as well as an equal number of unperturbed trials with full and with blocked vision. After grasping the object, participants returned to the starting dock and awaited the next trial. Participants rested between each block of trials to limit fatigue. Additionally, participants completed an eye-tracker calibration before each block to verify the accuracy of the system and to avoid drift in the data over time.

Data Processing and Analysis

The 3-dimensional reach trajectories were obtained from the position recordings of the haptic robots during each trial. Successful grasps occurred when subjects grasped the left and right sides of the object, with their thumb and index finger, respectively. Trials were unsuccessful when subjects touched and untouched the object with one finger but not the other (i.e. they ‘tapped’ it with the finger or thumb before grasping it) or when the digits touched the wrong part of the target (e.g. they bumped into the front of the object). Unsuccessful trials were not repeated. Success rate was the percentage of trials in which subjects were able to successfully grasp the object based on the number of overall trials performed. We computed the following measures for the successful grasp trials:

-

-

Movement onset: the time at which both fingertips left the starting dock.

-

-

Movement offset: the time of first finger contact with the object.

-

-

Reach duration: the time taken for subjects to leave the starting dock and touch the object (i.e., movement offset minus onset).

-

-

Aperture: the 3-dimensional Euclidean distance between the thumb and index fingers.

-

-

Anteroposterior Velocity: the velocity of the average position of the thumb and index finger along the anteroposterior axis (anterior velocity is the component of the velocity associated with moving towards the object).

-

-

Tangential velocity: the velocity of the average position of the thumb and index finger in 3-D space.

-

-

Eye-hand distances: the distance between the x or y screen coordinate of the thumb or index finger and the x or y screen coordinate of the gaze.

From these measures, we calculated the following variables used for statistical analyses:

Intensive (Scaling) Measures

Peak aperture: the maximum aperture during the movement.

Peak tangential velocity: the maximum speed during the movement.

Coordinative Measures

Movement destabilization index: the sum of time periods greater than 50 ms during which tangential velocity did not exceed 3% of the peak tangential velocity. This measure was based on previous studies reporting compensatory responses to perturbations in healthy, elderly individuals at latencies less than 50 ms, and at latencies greater than 50 ms in PD patients (Tunik et al. 2004, 2007). It was a measure of how well subjects adapted their movements online in perturbation trials in response to the rapid change in orientation of the object to be grasped. We have previously shown that PD patients, unlike healthy subjects, markedly slowed or even stopped their hand movement entirely during trunk-assisted reaching when the trunk was unexpectedly blocked (Tunik et al., 2004; 2007). We observed a similar phenomenon in the present experiment. The amount of time that the arm movement was destabilized in response to the change in orientation of the object to be grasped provided a measure of how well subjects flexibly altered their movement repertoire in response to the changed environmental demands. If subjects stopped their hand movement entirely upon seeing the object perturbation, the hand movement was reinitiated after some period of time. If the hand movement slowed down, the tangential velocity, although decreased, remained above zero and could fluctuate about an almost constant level for a given period of time.

Preshape coordination was calculated as the distance from peak aperture to peak speed along the anteroposterior axis as a percent of total distance travelled along that axis. It was a measure of how well subjects coordinated their hand and arm during the movement. The reach-to-grasp movement consisted of two distinct, but integrated components (Jeannerod 1981, 1984) that have been extensively studied. Normally, subjects preshape their hand during the reach such that their hand configuration evolves gradually to conform to the size or shape of the object to be grasped (Santello and Soechting, 1998). A measure of this coordination is the separation along the trajectory between peak aperture and peak speed. In more highly coordinated movements, the hand achieves peak aperture close to when the arm achieves peak speed, reflecting an integration of these two components in mapping the motor action to the object. Since small differences in movement amplitude arose due to variations in the exact contact points of the fingers on the object, we normalized the distance between peak aperture and peak speed by the movement amplitude along anteroposterior axis; a percentage of the reach distance separating peak aperture and peak speed was then obtained. Larger values reflect increased separation between peak aperture and peak speed and thus poorer hand-arm coordination.

Distance from peak aperture to grasp was defined as the anteroposterior distance from peak aperture to grasp. We have previously found that PD patients wait to shape their hands to grasp objects of different shapes until the hand is near the object, thus making both hand and object simultaneously visible in the workspace (Schettino et al., 2006).

Eye-hand span was defined as the mean minimum distance on the screen of the gaze point to either the thumb cursor or the index finger cursor across time. One measure of skilled eye-hand performance in a variety of skilled actions has been termed the eye- hand span. In playing musical instruments, for example, the eyes generally scan the music ahead of where the hand is playing. The spatial separation between the gaze on the musical score and the note the hand is playing, termed the eye-hand span, increases as a function of skill level (Wurtz et al. 2009; Furneaux and Land, 1999). Similarly, in reaching movements, the eyes typically lead the hand, and often remain locked on the target throughout the movement (Neggers and Bekkering, 2000). Thus, we used the minimum horizontal and vertical distances separating the gaze position and hand position on the screen as a measure of the coordination of hand and eye movements. If PD patients look at their hands during the reach, or look back-and-forth between the object and the hand, or between the cursor representing the thumb position and the cursor representing the finger position, they will have small eye-hand spans, and will also exhibit multiple saccades per unit time. For perturbation trials, the eye-hand span was separately computed for two phases of the movement: reach onset to perturbation and perturbation onset to grasp.

Eye-Hand Correlation was defined as the correlation between the mean vertical position on the screen of the hand (i.e., average of thumb and index position) with gaze position from reach onset to perturbation onset. If the gaze followed the hand during this initial phase of the reach, then the correlation would have been high, reflecting on-line tracking of the hand with their gaze. The mean horizontal position of the thumb and index was centered on the object for all subjects, and thus was not relevant. Correlations were transformed to Z-scores using the Fisher’s Z-transform (Corey et al. 1998).

Saccade Rate was the number of saccades from reach onset to grasp calculated using custom scripts for the EyeLink 1000. Since PD patients had longer movement durations than control subjects, the number of saccades was normalized to the movement duration, yielding the number of saccades per unit time or saccade rate

Statistical Analysis

For comparisons between control subjects and PD patients, a mixed design repeated measures ANOVA was performed on each variable with Group (PD-OFF, controls) as an independent factor, perturbation condition (perturbed trials, unperturbed trials), and vision condition (full vision, blocked vision) as repeated factors. To examine the effects of dopaminergic therapy, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on each dependent variable with Group (PD-ON, PD-OFF medications), perturbation condition (perturbed trials, unperturbed trials), and vision condition (full vision, blocked vision). P < 0.05 was used for statistical significance. Only significant results are reported.

RESULTS

Online corrective responses were impaired in PD patients off medication

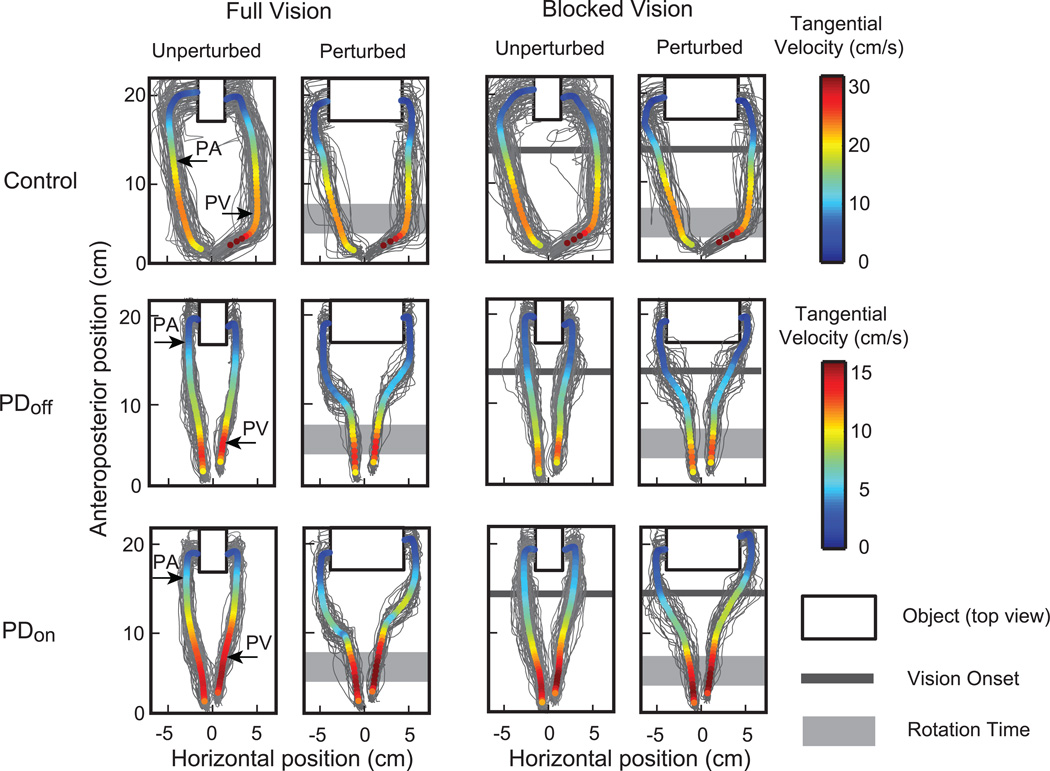

There were no significant differences in success rates of grasping the object between PD-OFF patients and age-matched control subjects (p > 0.05; Table 2). Thus, PD-OFF patients were able to readily adapt to the experimental setup and overall task requirements. However, despite having similar grasp success rates, PD patients exhibited marked abnormalities in the reach-to-grasp movements. Figure 2 presents the reach-to-grasp trajectories of the index finger and thumb for all successful trials of a representative PD patient on and off medications (PD ON vs. PD OFF) and an age-matched control. The grey lines in Figure 2 represent trajectories of single trials, and the thick colored line depicts the mean trajectory. The color of the trajectory represents the mean tangential velocity across trials throughout the reach. Figure 2 shows that the control subject exhibited a greater distance between the thumb and index finger from early on in the movement until the end of the reach. In contrast, the PD patient limited aperture to just beyond the size of the object. On average, peak aperture of participants with PD was 12% less than that of age matched controls (F(1,19) = 5.5, p < 0.05; Table 2). Figure 2 also shows that the PD patient’s reach-to-grasp movements were slower and more variable, particularly off medication, than the movements of the control subject. Note the 2-fold higher tangential velocity scale for the control than the PD patient, and in the greater spatial divergence of individual trials from the trajectory mean. As a group, PD OFF patients across visual conditions had on average 30% lower peak tangential velocity than controls (F(1,19) = 4.9, p < 0.05; Table 2). As expected, the effect of Perturbation was significant, with perturbed trials having significantly larger peak apertures than non-perturbed trials (F(1,19) = 216.3, p < 0.001; Table 3). The significant decreases in aperture and tangential velocity of PD patients are consistent with previous literature and the common clinical observation that PD patients show slow, small movements (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of outcome measures for all groups (n=9 PD patients on and off medication, n=12 age-matched controls).

| Condition |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Vision, Unperturbed |

Full Vision, Perturbed |

Blocked Vision, Unperturbed |

Blocked Vision, Perturbed |

|||||

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Peak Aperture (cm) | ||||||||

| Control | 8.3 | 1.5 | 11.5 | 0.6 | 8.7 | 1.6 | 11.8 | 0.7 |

| PD off | 6.6 | 1.5 | 10.8 | 1.2 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 10.9 | 1.2 |

| PD on | 6.7 | 1.2 | 11.0 | 0.8 | 7.3 | 1.4 | 11.2 | 0.7 |

| Peak Tangential Velocity (cm/s) | ||||||||

| Control | 24.5 | 4.8 | 24.5 | 5.0 | 23.1 | 4.9 | 22.8 | 4.4 |

| PD off | 16.7 | 9.8 | 16.8 | 10.7 | 16.1 | 8.8 | 17.0 | 9.7 |

| PD on | 15.3 | 7.1 | 15.3 | 7.8 | 15.3 | 6.5 | 15.1 | 6.7 |

| Movement Destabilization Index (ms) | ||||||||

| Control | 100.4 | 165.7 | 112.1 | 128.9 | 89.0 | 114.4 | 83.9 | 101.6 |

| PD off | 146.6 | 249.1 | 227.8 | 410.6 | 215.1 | 307.0 | 326.5 | 381.4 |

| PD on | 251.6 | 398.5 | 538.0 | 715.2 | 415.9 | 602.4 | 859.4 | 1136.7 |

| Preshape Coordination (%) | ||||||||

| Control | 25.0 | 17.0 | 50.2 | 9.9 | 35.6 | 19.3 | 54.0 | 8.8 |

| PD off | 48.6 | 21.2 | 62.9 | 12.2 | 52.0 | 14.7 | 64.7 | 13.2 |

| PD on | 44.5 | 15.9 | 59.8 | 8.9 | 48.6 | 9.0 | 60.4 | 9.2 |

| Distance from Peak Aperture to Grasp (cm) | ||||||||

| Control | 6.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 5.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.7 |

| PD off | 2.9 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.8 |

| PD on | 3.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Minimum Horizontal Eye-Hand Span during reach to perturbation (mm) | ||||||||

| Control | 52.3 | 11.1 | 51.5 | 11.3 | 51.3 | 11.7 | 49.0 | 10.8 |

| PD off | 32.6 | 11.0 | 30.2 | 15.1 | 26.3 | 12.8 | 26.4 | 12.3 |

| PD on | 28.0 | 9.9 | 28.1 | 10.6 | 26.7 | 9.7 | 28.0 | 10.8 |

| Minimum Horizontal Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | ||||||||

| Control | 37.1 | 8.1 | 43.6 | 8.8 | 39.7 | 8.2 | 44.6 | 9.1 |

| PD off | 34.3 | 9.8 | 43.2 | 7.7 | 34.5 | 13.6 | 42.6 | 8.7 |

| PD on | 30.4 | 8.3 | 43.2 | 6.0 | 32.6 | 7.1 | 43.9 | 6.6 |

| Minimum Vertical Eye-Hand Span during reach to perturbation (mm) | ||||||||

| Control | 59.0 | 31.4 | 60.2 | 32.3 | 60.9 | 31.6 | 62.5 | 30.0 |

| PD off | 71.5 | 54.3 | 72.4 | 56.6 | 73.2 | 55.2 | 72.6 | 55.6 |

| PD on | 74.6 | 52.8 | 74.2 | 54.1 | 73.7 | 52.9 | 74.9 | 53.5 |

| Minimum Vertical Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | ||||||||

| Control | 62.7 | 35.4 | 55.0 | 31.7 | 58.3 | 33.5 | 55.7 | 33.9 |

| PD off | 74.8 | 60.0 | 66.9 | 53.8 | 64.8 | 60.3 | 66.6 | 50.8 |

| PD on | 83.2 | 62.1 | 84.4 | 56.4 | 81.4 | 60.8 | 82.5 | 56.1 |

| Saccade Rate (No. of saccades/s) | ||||||||

| Control | 1.5 | 0.4 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| PD off | 2.0 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| PD on | 2.0 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0.6 |

| Grasp Success Rate (%) | ||||||||

| Control | 85.6 | 10.7 | 73.8 | 19.4 | 83.8 | 15.5 | 74.3 | 17.0 |

| PD off | 87.9 | 8.1 | 69.2 | 24.7 | 86.0 | 10.1 | 68.2 | 25.2 |

| PD on | 85.5 | 9.5 | 69.9 | 20.0 | 86.9 | 9.0 | 69.3 | 21.0 |

Figure 2. Thumb and index finger reach trajectories.

Top view of reach to grasping movements in one representative PD patient on and off medications (PD ON vs. PD OFF) and his/her age-matched control. Individual trial thumb and index finger trajectories are colored in gray, whereas the mean trajectories of the thumb and index finger are color-coded relative to their mean speed across time. The virtual object is depicted by a black outlined rectangle. For the perturbed conditions, a light gray rectangle represents the ~20–40% of the reach when the object was rotated. For the blocked vision conditions, visual feedback of finger position was removed through the first ~2/3rds of the reach, as seen here as a dark gray line. The average peak aperture (PA) and peak tangential velocity (PV) are marked along the thumb and index finger for each of the representative subjects during the unperturbed full vision condition.

Table 3.

RM-ANOVA tables for PD OFF vs. control comparison.

| Effect | SS | df | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Aperture (cm) | |||||

| Group | 29.3 | 1 | 5.5 | .030** | |

| Vision | 1.8 | 1 | 18.2 | .000** | |

| Perturbation | 265.9 | 1 | 216.3 | .000** | |

| Vision × Perturbation | 0.2 | 1 | 6.6 | .018** | |

| Peak Tangential Velocity (cm/s) | |||||

| Group | 1036.8 | 1 | 4.9 | .039** | |

| Vision | 16.3 | 1 | 9.5 | .006** | |

| Group × Vision | 8.9 | 1 | 5.2 | .034** | |

| Movement Destabilization Index (ms) | |||||

| Perturbation | 0.1 | 1 | 5.0 | .037** | |

| Group × Vision | 0.1 | 1 | 5.8 | .026* | |

| Group × Perturbation | 0.0 | 1 | 4.4 | .050* | |

| Preshape Coordination (%) | |||||

| Group | 0.5 | 1 | 7.4 | .013** | |

| Vision | 0.1 | 1 | 8.9 | .008** | |

| Perturbation | 0.6 | 1 | 53.8 | .000** | |

| Distance from Peak Aperture to Grasp (cm) | |||||

| Group | 80.5 | 1 | 11.5 | .003** | |

| Vision | 4.0 | 1 | 6.7 | .018** | |

| Perturbation | 124.1 | 1 | 35.2 | .000** | |

| Group × Perturbation | 20.2 | 1 | 5.7 | .027** | |

| Minimum Horizontal Eye-Hand Span during reach to perturbation (mm) | |||||

| Group | 10094.6 | 1 | 19.6 | .000** | |

| Vision | 239.8 | 1 | 6.7 | .018** | |

| Minimum Horizontal Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | |||||

| Perturbation | 1025.7 | 1 | 14.1 | .001** | |

| Minimum Vertical Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | |||||

| Vision × Perturbation | 284.5 | 1 | 4.4 | .050** | |

| Saccade Rate (No. of saccades/s) | |||||

| Group | 5.9 | 1 | 5.4 | .032** | |

| Perturbation | 2.5 | 1 | 28.6 | .000** | |

| Eye-Hand Correlation during reach to perturbation (Z-scored) | |||||

| Group | 1.1 | 1 | 4.798 | .041** | |

| Eye-Hand Correlation during perturbation to grasp (Z-scored) | |||||

| Group × Vision | 0.1 | 1 | 7.696 | .012** | |

| Grasp Success Rate (%) | |||||

| Perturbation | 4287.0 | 1 | 11.0 | .004** | |

p < .05

p < .005

NOTE: SS = sum of squares, df = degrees of freedom.

Impaired hand transport and movement destabilization in PD

Figure 3 shows that the velocity in the anterior direction and the tangential velocity for the PD patients differed markedly from those of the controls. Whereas control subjects displayed typical bell-shaped velocity profiles for reaching during unperturbed trials, PD patients displayed a slower and more constant velocity throughout. Similar to tangential velocity, peak velocity in the anterior direction of PD patients was 32% less than that of age matched controls. Despite having overall slower reach velocities, PD patients were unable to maintain velocity when the object rotated, as seen as a decrease in both the tangential velocity and velocity in the anterior direction following object perturbation (perturbed trials in Figure 3). In contrast, control subjects smoothly continued to increase speed while adjusting hand aperture.

Figure 3. Anteroposterior and tangential velocity during reach.

Mean anteroposterior velocity (A) and tangential velocity (B) is shown for one representative PD subject on (blue line) and off (red line) medications and his/her age-matched control (green line). The thin lines represent individual trials and the thick lines present mean traces for each condition. The top row and bottom row depict full vision and blocked vision conditions, respectively, during unperturbed and perturbed trials (left and right plots of each row, respectively). Overall, PD patients were found to have slower peak velocities in comparison to healthy age matched controls

Additionally, PD patients showed a two-fold increase in their movement destabilization index compared to control subjects, particularly in blocked vision trials versus full vision trials (i.e., Group × Vision interaction effect, F(1,19) = 5.8, p < 0.05; Figure 4) and in perturbed versus unperturbed trials (i.e., Group × Perturbation interaction effect, F(1,19) = 4.4, p ≤ 0.05; Figure 4A). Figure 4A shows that the significant interaction of Group × Vision was due to the markedly deteriorated online corrective responses of the PD patients compared to control subjects when visual feedback of the finger positions was blocked. Likewise, the Group × Perturbation interaction indicates that PD patients had much greater difficulty than control subjects in achieving online corrections to the object rotation (Figure 4A). Since vertical or lateral components of the movement would not affect sagittal velocity but would affect tangential velocity, the destabilized movements of the PD patients involved both pausing in the anterior-posterior axis and slight changes in movement direction.

Figure 4. Movement destabilization index and peak aperture to grasp distance.

Mean (SE) of movement destabilization index (A), and peak aperture to grasp distance (B) is displayed across experimental conditions for PD ON, PD OFF, and controls. PD patients have an increased movement destabilization index in comparison to controls, particularly when the target is perturbed, and decreased peak aperture to grasp distance than healthy age-matched controls.

Hand preshaping deficits in PD

Figure 2 illustrates another difference across groups, relating to the preshaping of the hand during the reach. Healthy young adults coordinate their hand and arm movements, preshaping their hands during the reach such that peak aperture and peak speed are achieved nearly synchronously (Jeannerod, 1984; Wallace et al., 1990). Figure 2 shows that preshape coordination, defined by distance along the path separating peak aperture and peak speed, was reduced in the PD patient. Peak aperture and peak speed occurred in a more coincident manner in the control subject than in the PD patient (left-hand panels of Figure 2). PD patients achieved peak aperture much later than peak speed in the reach, nearly at grasp, whereas in control subjects, peak aperture and speed occurred closer to mid-reach. This pattern led to a 38% lower (better) preshape coordination measure in controls compared to PD patients (F(1,19) = 7.4, p < 0.05, Table 2). PD patients did not achieve peak aperture until their hand was near the object, a markedly (49%) shorter distance relative to controls (F(1,19) = 11.5, p < 0.005, Table 2). The shortened distance from peak aperture to grasp for PD patients relative to controls was more pronounced for unperturbed trials than for perturbed trials, where both groups shortened the distance between peak aperture and grasp (F(1,19) = 5.7, p < 0.05; Figure 4B). It should be noted, however, that the slower movements of the PD patients could have contributed to their impaired preshape coordination (Gordon et al., 1994).

PD patients tracked their hands with their gaze

Figure 5 presents the vertical (Figure 5A) and horizontal (Figure 5B) positions on the screen of the thumb, index finger, and gaze as a function of time (normalized to the movement duration) for a representative trial for a control subject and PD patient. At reach onset, the gaze of the control subject did not overlap with the position of the thumb or index finger. The control subject made a saccade to the object before moving the hand and kept his gaze there, except for making an additional small saccade as the hand neared the object. In contrast, the gaze of the PD patient often overlapped with the position of either the thumb or index finger, as if following the hand with the gaze. Moreover, in contrast to the control subject, the PD patient made numerous short saccades between the thumb and the index finger as the movement progressed. Figure 7 presents the mean (SD) horizontal hand and gaze positions across all subjects in each group. Overall, the minimal horizontal eye-hand span from reach onset to object perturbation was markedly smaller for PD OFF patients than control subjects, indicating that PD patients tended to look at their hand during the first phase of the reach instead of using feed-forward anticipatory mechanisms (F(1,19) = 19.6, p < 0.001; Table 2). In comparison to control subjects, eye-hand correlations during reach onset to perturbation onset were higher in PD patients: the Fisher’s z transform (rz’) increased from 0.47 for controls to 0.70 in PD patients (F(1,19) = 4.8, p < 0.05; Table 3). Furthermore, saccade rate of PD patients was 31% greater in comparison to controls (F(1,19) = 5.4, p < 0.05; Table 2). Taken together, smaller eye-hand span, increased eye-hand correlations, and increased saccade rate relative to control subjects suggested that PD patients had a greater reliance on visual feedback of their hand during reach.

Figure 5. Eye-hand span.

Red and blue lines of each plot represent the horizontal (Panel A) or vertical (Panel B) position of thumb and index finger over time for a single trial. The black line of each plot represents the projection of the eye on the monitor over the anteroposterior distance from tone to grasp. The gray rectangle illustrates the horizontal and vertical span of the virtual object in perturbed and unpertubed trials. Data are shown for a representive control (top plots) and PD (OFF: middle plots; ON: bottom plots) participant during a perturbed trial with blocked vision and an unperturbed trial with full vision. Unperturbed trials without vision and perturbed trials with vision demonstrated similar characteristics. Reach onset (vertical dashed line), perturbation onset (vertical solid line), and the portion of the trial with blocked vision (light gray box) are indicated in each trial. Note that distance is normalized across groups and conditions for graphical comparison. In contrast to age matched control subjects, PD patients, particularly on medications more closely track finger movements with their eyes.

Blocking visual feedback of hand increased trial-to-trial reach variability

To investigate the extent to which PD patients relied on vision of their hand during the reach, we removed visual feedback of the fingers after movement onset for the first ~2/3rds of the reach during a subset of trials. The right-hand panels of Figure 2 show that removal of vision increased the trial-to-trial variability of the trajectories in PD patients, both on and off medication. Despite these qualitative differences, no differences in success rate were found. However, peak tangential velocity demonstrated a surprising finding, as PD patients had relatively invariant peak tangential velocity across blocked and full vision trials, in contrast to controls who decreased tangential velocity with removal of visual feedback (F(1,19) = 5.2, p < 0.05; Table 2). Interestingly, in spite of the lack of vision PD patients successfully continued to look at the screen where their finger cursors would have been rendered, as indicated by their consistently smaller horizontal eye-hand span compared to the controls (F(1,19) = 10094.6, p < 0.001, Table 2, Figure 7).

Dopaminergic medication did not improve corrective response control

Consistent with our previous finding that dopaminergic therapy did not reverse impaired online corrections of arm movements to a trunk perturbation in PD (Tunik et al., 2007), we found that medication did not significantly improve PD patients’ ability to adapt to the object perturbation. On the contrary, dopaminergic therapy was found to worsen PD patients’ ability to adapt. There was a significant Group × Perturbation interaction, indicating that when PD patients were on medications, they showed over a three-fold increase in their movement destabilization index when the object was perturbed (F(1,8) = 6.7, p < 0.05; Figure 4). Similar to PD OFF, PD ON patients exhibited smaller peak apertures, peak tangential velocity, decreased preshape coordination and peak aperture to grasp distance, and an increased saccade rate and increased eye-hand correlations during reach onset to perturbation onset compared to controls, across experimental conditions (Tables 2 and 4). In contrast to PD OFF, PD ON patients had increased peak aperture to grasp distances (F(18) = 11.2, p < 0.05; Table 2) and vertical eye-hand span during perturbation to grasp (F(18) = 6.4, p < 0.05; Table 2). Both of these latter findings suggest that PD patients on medication relied less strongly on visual guidance of the grasp.

Table 4.

RM-ANOVA tables for PD ON vs OFF comparison.

| Effect SS | df | F | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Aperture (cm) | ||||

| Vision | 2.2 | 1 | 36.2 | .000** |

| Perturbation | 296.2 | 1 | 181.8 | .000** |

| Vision × Perturbation | 0.9 | 1 | 8.8 | .018* |

| Movement Destabilization Index (ms) | ||||

| Perturbation | 1.0 | 1 | 5.6 | .045* |

| Medication × Perturbation | 0.3 | 1 | 6.7 | .032* |

| Preshape Coordination (%) | ||||

| Perturbation | 0.3 | 1 | 24.0 | .001** |

| Distance from Peak Aperture to Grasp (cm) | ||||

| Medication | 5.4 | 1 | 11.2 | .010* |

| Perturbation | 41.5 | 1 | 11.9 | .009* |

| Minimum Horizontal Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | ||||

| Perturbation | 1880.1 | 1 | 14.8 | .005** |

| Minimum Vertical Eye-Hand Span during perturbation to grasp (mm) | ||||

| Medication | 3833.7 | 1 | 6.4 | .035* |

| Vision | 220.9 | 1 | 5.8 | .043* |

| Saccade Rate (No. of saccades/s) | ||||

| Vision | 0.1 | 1 | 6.3 | .037* |

| Perturbation | 2.6 | 1 | 29.9 | .001** |

| Grasp Success Rate (%) | ||||

| Perturbation | 5453.9 | 1 | 8.0 | .022* |

p < .05

p < .005

NOTE: SS = sum of squares, df = degrees of freedom.

DISCUSSION

We examined the effect of Parkinson’s disease on eye-hand coordination and online corrective responses by having PD patients and age-matched controls reach for and grasp a rectangular object in a virtual realty environment with visual and haptic feedback, while simultaneously recording finger and thumb movements and eye movements. On a subset of trials, the to-be-grasped object rotated mid-reach such that subjects had to adapt their finger trajectories online to successfully grasp the object. In addition, on half of the trials visual feedback of finger positions disappeared during the feedforward phase of movement, forcing subjects to rely on internal rather than external guidance of the movement.

Our first hypothesis was that healthy, elderly subjects, but not PD patients off dopaminergic therapy would rapidly and smoothly alter their finger trajectories to enable a successful grasp. This hypothesis was strongly supported (Figures 2, 3, and 4A). Second, we hypothesized that due to PD patients’ over-reliance on external, visual control of their movements, they would show markedly abnormal patterns of eye-hand coordination. This hypothesis also was supported (Figures 5 and 6). Indeed, we found that PD patients off medication made multiple, short saccades that tracked their finger-thumb positions during the course of the movement (Figure 5). Third, we hypothesized that blocking vision of the hand would have a much more detrimental effect on the movements of the PD patients than on the control subjects. As hypothesized, movements of the PD patients off medication were significantly more destabilized than those of the control subjects when vision was blocked compared to when it was not (Figure 4A). Finally, we hypothesized that dopaminergic therapy, in addition to improving clinical motor function, would improve reach speed and the amplitude of hand opening in PD patients but would not reverse online correction deficits or deficits in eye-hand coordination. This hypothesis was partially supported. Dopaminergic therapy improved clinical motor function, but did not significantly improve peak speed or peak aperture. Moreover, medications worsened online corrections to the perturbation (Figure 4A) and did not improve arm-hand or eye-hand coordination. Nonetheless, PD patients on medication achieved peak aperture earlier during the reach than they did off medication, suggesting that they relied less strongly on visual guidance of the grasp when on therapy.

Figure 6. Minimum eye-hand span during reach.

Horizontal minimum eye-hand span from reach onset to perturbation is shown for controls (green lines), PD ON (blue lines), and PD OFF (red lines) during full vision and blocked vision conditions (top and bottom plots, respectively) for unperturbed and perturbed trials (left and right plots, respectively). In contrast to healthy age-matched control subjects, PD patients have smaller horizontal eye-hand span from reach to perturbation.

PD patients off medication exhibit impaired online grasp corrections to object perturbations

Consistent with prior studies (Poizner et al. 2000; Tunik et al. 2004), even though PD patients were able to correctly grasp the object on its left and right side as successfully as the control subjects, they were unable to synchronize fingertip movements and perform rapid and smooth corrective responses (Figure 3). In response to the object perturbation, PD patients exhibited a significant decrease in hand velocity directly following the rotation of the object (Figure 3). This is in contrast to age-matched control subjects who exhibited a smooth continuation of hand movement towards the object. Indeed, at times, PD patients would completely stop the forward movement of the arm when the object was perturbed or even move their hand slightly backward or off the anterior-posterior axis. This lack of online corrective response to the perturbation occurred despite the fact that the PD patients moved more slowly than the control subjects, and thus would have had more time than control subjects to smoothly alter their movements. Subjects’ ability to adjust an ongoing movement was quantified with the movement destabilization index, which represents the amount of time that the hand spends in a paused state in the direction of movement towards the object. PD patients off medication had a two-fold increase in the movement destabilization index over that of control subjects when vision was provided, and a four-fold increase over that of controls when vision was blocked. This excessive time spent in a destabilized pause for a reach-to-grasp action is very consistent with our previous data for reach-to-location movements during online perturbations that showed similar pauses during the online adaptive response and which remained largely impervious to dopaminergic treatment (Tunik et al, 2007). In all, these data suggest that PD patients have impaired rapid reprogramming of ongoing movements irrespective of the upper limb effector system.

In order to reconfigure the opening of the hand smoothly and rapidly during the reach when the object is unexpectedly perturbed, particularly when vision is blocked, subjects must integrate proprioception from the moving arm and hand with a visual representation of the altered object. For this to happen, the brain must compute the geometric relations between the new object orientation (sensed through vision) and the position, orientation, and movement of the hand and arm (sensed through proprioception) when vision is blocked (Soechting and Flanders, 1989; Crawford et al. 2004). It has recently become clear that cells in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and cortical motor areas show a lack of specificity in responding to changes in limb position in primate models of PD (Boraud et al. 2000; Escola et al. 2002; Pessiglione et al. 2005) and that PD patients show proprioceptive deficits of the arm and hand (Fiorio et al. 2007; Konczak et al. 2009). Thus, the lack of precision in proprioceptive processing in PD patients may have prevented them from rapidly and smoothly adapting to the object perturbation. The pauses in the arm movements of the PD patients when the object was perturbed may reflect this imprecision in processing proprioceptive signals and integrating proprioception with vision. Thus, the integrity of cortico-basal ganglia circuits may be critical for updating an ongoing action in dynamic environments.

PD patients off medication have impaired hand-arm coordination

Normally, subjects preshape their hand during reach such that their hand configuration evolves gradually to conform to the size or shape of the object to be grasped (Santello and Soechting, 1998). A measure of this coordination is the separation along the trajectory between peak aperture and peak speed (preshape coordination). In more highly coordinated movements, the hand achieves peak aperture close to when the arm achieves peak speed, reflecting an integration of these two components in mapping the motor action to the object. Consistent with previous studies (Schettino et al. 2006; Teulings et al. 1997), we found that PD patients showed impaired preshape coordination (Figure 2). This failure in coordinating the two motor components was present even with full vision of both arm and target. Moreover, as in previous studies (Rand et al. 2006; Schettino et al. 2003; 2006), PD patients did not achieve peak aperture until the hand approached the object where hand and object could be simultaneously visualized. There are multiple, parallel loops connecting cortex and basal ganglia that are topographically organized and functionally segregated (Alexander et al. 1990; Hoover and Strick, 1993). However, under conditions of dopamine depletion, this circuit organization shows reduced functional segregation (Bergman et al. 1998), which may have led to a lack of parallel control of hand and arm seen in the present study. We do note however, that the PD patients moved more slowly than did the control subjects. Since moving very slowly engages a different control process from faster speed movements (Gordon et al., 1994), an element of the deficient hand-arm coordination in PD patients may derive from their very slow movement speeds. This should be systematically investigated in future studies.

PD patients off medication show reduced eye-hand span

Eye-hand span was significantly reduced during the feedforward phase of the reaching movement, as evidenced by the decreased minimal horizontal eye-hand span from reach-to-perturbation in PD patients (Figures 5 and 6). In contrast to healthy adults who made a saccade to the object and anchored their gaze there during the reach, PD patients tracked their hands with their gaze throughout the reach. PD patient reliance on direct vision of the hand is a novel finding and is consistent with PD patients having deficits in limb proprioception (Rand et al. 2010; Konczak et al. 2009; Lee et al. in press). Unexpectedly, this pattern was apparent regardless of whether or not patients actually had visual feedback of their hand (i.e., Blocked Vision Condition; Figures 5 and 6). Thus, patients may have been trying to continuously predict the location of their hand in space. Since this behavior was evident during what should have been controlled by feedforward motor processes, it lends further support to presence of PD abnormalities in anticipatory control (Lukos et al., 2010) and/or proprioception feedback mechanisms (Konczak et al., 2009). Since anticipatory control is known to be essential for optimizing motor activities, deficits in anticipatory control of eye-hand movements may be an underappreciated aspect of PD patients’ behavioral impairments and deserves further attention.

We are unaware of any other studies in the literature that have simultaneously monitored and analyzed eye-hand coupling throughout the course of a reaching or grasping movement in PD. There have been a few other studies to simultaneously measure eye and hand movements in PD patients, and these studies also found disturbed patterns of eye-hand coupling in PD (Warabi et al. 1988; Muilwijk et al. 2013), although these studies restricted analysis to relative onset and offset latencies of the hand and eye. Abnormal eye-hand coupling as well as intersegmental coordination (c.f. Poizner et al. 2000) may be a highly sensitive indicator basal ganglia dysfunction. This abnormality may be apparent even when the overall movement goal of reaching and grasping an object is preserved in PD patients, as in the present study. Moreover, the marked tendency of the PD patients to visually track their hands in the present study, and the improvement in PD performance commonly reported when PD patients can see their hands (Flash et al. 1992; Klockgether et al. 1994; Poizner et al. 2000) suggests that abnormal eye-hand coupling may serve as a sensitive, quantitative measure of the existence of basal ganglia dysfunction.

Dopaminergic therapy does not restore the ability to adapt to environmental perturbations

Dopaminergic therapy, as expected, significantly improved clinical motor function in the PD patients as measured with the UPDRS. In contrast to prior studies (Johnson et al. 1994, 1996; Schettino et al. 2006; Tunik et al. 2007; Levy-Tzedek et al. 2011), intensive aspects of the reaching movements such as peak speed and peak aperture were not significantly improved with dopaminergic therapy. However, the present study used only small movement amplitudes, and, thus, the peak hand velocities of both control and PD subjects were low. Since there was no requirement for subjects to make fast movements, the beneficial effect of dopaminergic therapy on intensive parameters such as speed would have been minimized. Importantly, dopaminergic therapy did not improve patients’ ability to smoothly alter their hand and arm movements in response to the perturbation of the object. This finding is similar to that of Tunik et al. (2007) where dopaminergic therapy did not reverse deficits in online corrections to mechanically blocking a trunk movement during a trunk-assisted reaching movement to a spatial target. Moreover, in the present study, dopaminergic therapy did not improve coordination of the hand and arm, or coordination of the eye and hand during the reach, and actually worsened PD patients’ ability to adapt to the visual perturbation of the object (Figure 4A). However, PD patients on medication achieved peak aperture earlier during the reach than they did off medication. This finding suggests that dopaminergic therapy may have reduced PD patients’ reliance on visual guidance of the grasp and thus did improve some aspects of feedforward control. Overall, however, these data provided added support for the notion that dopaminergic therapy does not improve fine motor coordination. Dopaminergic therapy acts to increase tonic (background) levels of dopamine, but may not improve the phasic (transient) release of dopamine that needs to be appropriately synchronized with dynamic changes in the movement and in the environment for the optimal control of movement (Morris et al. 2010; Rice et al. 2011).

Neurophysiological basis for reach-to-grasp corrective response deficits

The anterior intraparietal sulcus (aIPS) appears to be a crucial cortical region involved in the integration of a target goal with an emerging action plan during visually guided reach-to-grasp tasks (Tunik et al. 2005, 2008a). When this region is temporarily disabled, corrective responses of hand shaping during reach to perturbed objects are disrupted (Tunik et al. 2005; Rice et al. 2006; Tunik et al. 2008b). The anterior intraparietal area (AIP), believed to be the neural correlate of aIPS in nonhuman primates (Binkofski et al. 1998; Frey et al. 2005), has been shown to receive significant inputs from the basal ganglia (Clower, Dum, and Strick 2005). Thus, PD, which is associated with dysfunction of basal ganglia-cortical circuits, may not provide appropriate input to aIPS for detecting and / or correcting for online disruptions to grasp. If so, basal ganglia-cortical circuit dysfunction in PD should compromise the ability to generate corrective responses to object perturbations, as was indeed found. However, the functionality of the parietal-frontal networks in PD patients and their ability to adapt to object perturbations remains virtually unexplored. Moreover, the role of dopaminergic pathways in modulating behavioral and cortical responses during complex motor actions is also poorly understood (Schettino et al. 2006; Tunik et al. 2007; Levy-Tzedek et al. 2011). Further investigations of the cortical activity through the analysis of EEG associated with corrective response control in PD are currently underway in our laboratory.

Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrated that PD patients exhibit impaired eye-hand coordination and impaired online corrective response control.. Moreover, increasing tonic dopamine levels through dopaminergic therapy did not reverse online corrective response deficits or eye-hand coordination deficits in PD patients. Furthermore, our results provide evidence that eye-hand coordination during natural actions is impaired in PD patients, irrespective of tonic dopamine levels, thus increasing our understanding of the relation between eye-hand coordination and the critical functions of basal ganglia-cortical circuits for the control of complex movements. Finally, virtual environments that include haptic feedback provide a powerful experimental setting for studying naturalistic motor behavior in healthy individuals and in individuals with neuromotor disorders. The fact that PD patients showed typical PD motor deficits in the present study, despite their limited prior interaction with the virtual environment, or even experience with computers in some cases, provides an important foundation for the planning of future virtual reality experiments and rehabilitation strategies for patient populations.

Highlights.

We studied online visuomotor control of grasping in Parkinson’s disease (PD)

PD patients showed pauses and changes in movement direction in corrective movements

PD patients looked at their hands rather than at the object while reaching to grasp

Dopaminergic therapy did not reverse online adaptation deficits

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health Grant 2 R01 NS-036449 (H.P.), National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant #SMA-1041755 to the Temporal Dynamics of Learning Center, an NSF Science of Learning Center, NSF Grants ENG-1137279 (EFRI M3C) and BCS-1029084 (S.H.), and ONR MURI Grant N00014-10-0072 (H.P.). We thank Sofia Campos, Luke Miller and Markus Plank for their help with equipment setup and data collection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

No conflict of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Adamovich SV, Berkinblit MB, Hening W, Sage J, Poizner H. The interaction of visual and proprioceptive inputs in pointing to actual and remembered targets in Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience. 2001;104:1027–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert F, Diermayr G, McIsaac TL, Gordon AM. Coordination of grasping and walking in Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 2010;202:709–721. doi: 10.1007/s00221-010-2179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecke R, Rothwell JC, Dick JP, Day BL, Marsden CD. Performance of simultaneous movements in patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1986;109(Pt 4):739–757. doi: 10.1093/brain/109.4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benecke R, Rothwell JC, Dick JP, Day BL, Marsden CD. Disturbance of sequential movements in patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1987;110(Pt 2):361–379. doi: 10.1093/brain/110.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman H, Feingold A, Nini A, Raz A, Slovin H, Abeles M, Vaadia E. Physiological aspects of information processing in the basal ganglia of normal and parkinsonian primates. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:32–38. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binkofski F, Dohle C, Posse S, Stephan KM, Hefter H, Seitz RJ, Freund HJ. Human anterior intraparietal area subserves prehension: a combined lesion and functional MRI activation study. Neurology. 1998;50:1253–1259. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisseau Scherzer, Cohen Eye-Hand Coordination in Aging and in Parkinson's Disease. Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition. 2002;9:266–275. [Google Scholar]

- Boraud T, Bezard E, Bioulac B, Gross CE. Ratio of inhibited-to-activated pallidal neurons decreases dramatically during passive limb movement in the MPTP-treated monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1760–1763. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briand KA, Strallow D, Hening W, Poizner H, Sereno AB. Control of voluntary and reflexive saccades in Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 1999;129:38–48. doi: 10.1007/s002210050934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castiello U, Bennett KM. Parkinson's disease: reorganization of the reach to grasp movement in response to perturbation of the distal motor patterning. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:1367–1382. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clower DM, Dum RP, Strick PL. Basal ganglia and cerebellar inputs to 'AIP'. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:913–920. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey DM, Dunlap WP, Burke MJ. Averaging Correlations: Expected Values and Bias in Combined Pearson rs and Fisher's z Transformations. The Journal of General Psychology. 1998;125:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JD, Medendorp WP, Marotta JJ. Spatial transformations for eye-hand coordination. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:10–19. doi: 10.1152/jn.00117.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TJ, Henderson L, Kennard C. Abnormalities of nonvisually-guided eye movements in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1989;112(Pt 6):1573–1586. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.6.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defer GL, Widner H, Marié RM, Rémy P, Levivier M. Core assessment program for surgical interventional therapies in Parkinson's disease (CAPSIT-PD) Mov Disord. 1999;14:572–584. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199907)14:4<572::aid-mds1005>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget M, Epstein CM, Turner RS, Prablanc C, Alexander GE, Grafton ST. Role of the posterior parietal cortex in updating reaching movements to a visual target. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:563–567. doi: 10.1038/9219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escola L, Michelet T, Douillard G, Guehl D, Bioulac B, Burbaud P. Disruption of the proprioceptive mapping in the medial wall of parkinsonian monkeys. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:581–587. doi: 10.1002/ana.10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorio M, Stanzani C, Rothwell JC, Bhatia KP, Moretto G, Fiaschi A, Tinazzi M. Defective temporal discrimination of passive movements in Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;417:312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flash T, Inzelberg R, Schechtman E, Korczyn AD. Kinematic analysis of upper limb trajectories in Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 1992;118:215–226. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90038-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers KA. Visual “closed-loop” and “open-loop” characteristics of voluntary movement in patients with Parkinsonism and intention tremor. Brain. 1976;99:269–310. doi: 10.1093/brain/99.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey SH, Vinton D, Norlund R, Grafton ST. Cortical topography of human anterior intraparietal cortex active during visually guided grasping. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;23:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furneaux S, Land MF. The effects of skill on the eye-hand span during musical sight-reading. Proc Biol Sci. 1999;266:2435–2440. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou N, Iansek R, Bradshaw JL, Phillips JG, Mattingley JB, Bradshaw JA. An evaluation of the role of internal cues in the pathogenesis of parkinsonian hypokinesia. Brain. 1993;116(Pt 6):1575–1587. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.6.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Ghilardi MF, Ghez C. Accuracy of planar reaching movements. I. Independence of direction and extent variability. Exp Brain Res. 1994;99(1):97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00241415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HaGAN JJ, Middlemiss DN, Sharpe PC, Poste GH. Parkinson's disease: prospects for improved drug therapy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18:156–163. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover JE, Strick PL. Multiple output channels in the basal ganglia. Science. 1993;259:819–821. doi: 10.1126/science.7679223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. Intersegmental coordination during reaching at natural objects. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 153–169. Attention and performance IX. [Google Scholar]

- Jeannerod M. The timing of natural prehension movements. J Mot Behav. 1984;16:235–254. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1984.10735319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson N, Brown P. New insights into the relationship between dopamine, beta oscillations and motor function. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MT, Kipnis AN, Coltz JD, Gupta A, Silverstein P, Zwiebel F, Ebner TJ. Effects of levodopa and viscosity on the velocity and accuracy of visually guided tracking in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 3):801–813. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.3.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MT, Mendez A, Kipnis AN, Silverstein P, Zwiebel F, Ebner TJ. Acute effects of levodopa on wrist movement in Parkinson's disease. Kinematics, volitional EMG modulation and reflex amplitude modulation. Brain. 1994;117(Pt 6):1409–1422. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.6.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klockgether T, Dichgans J. Visual control of arm movement in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 1994;9(1):48–56. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konczak J, Corcos DM, Horak F, Poizner H, Shapiro M, Tuite P, Volkmann J, Maschke M. Proprioception and motor control in Parkinson's disease. J Mot Behav. 2009;41:543–552. doi: 10.3200/35-09-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Henriques DY, Snider J, Song D, Poizner H. Reaching to proprioceptively defined targets in Parkinson's disease: Effects of deep brain stimulation therapy. Neuroscience. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Henriques DYP, Song DD, Poizner H. Reaching to kinesthetically defined targets in Parkinson’s disease: Effects of deep brain stimulation therapy. Neuroscience [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Tzedek S, Krebs HI, Arle JE, Shils JL, Poizner H. Rhythmic movement in Parkinson's disease: effects of visual feedback and medication state. Exp Brain Res. 2011;211:277–286. doi: 10.1007/s00221-011-2685-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidsky TI, Manetto C. Context-dependent activity in the striatum of behaving cats. Toronto: Hans Huber Publishers; 1987. pp. 123–133. Basal Ganglia and Behavior: Sensory Aspects of Motor Functioning. [Google Scholar]

- Lukos JR, Lee D, Poizner H, Santello M. Anticipatory modulation of digit placement for grasp control is affected by Parkinson's disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi B, Genovesio A, Battaglia-Mayer A, Ferraina S, Squatrito S, Molinari M, Lacquaniti F, Caminiti R. Eye-hand coordination during reaching. I. Anatomical relationships between parietal and frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11:513–527. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miall RC, Reckess GZ. The cerebellum and the timing of coordinated eye and hand tracking. Brain Cogn. 2002;48:212–226. doi: 10.1006/brcg.2001.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris ED, Constantinescu CC, Sullivan JM, Normandin MD, Christopher LA. Noninvasive visualization of human dopamine dynamics from PET images. Neuroimage. 2010;51:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muilwijk D, Verheij S, Pel JJ, Boon AJ, van der Steen J. Changes in Timing and kinematics of goal directed eye-hand movements in early-stage Parkinson's disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2013;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neggers SF, Bekkering H. Ocular gaze is anchored to the target of an ongoing pointing movement. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:639–651. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessiglione M, Guehl D, Rolland AS, François C, Hirsch EC, Féger J, Tremblay L. Thalamic neuronal activity in dopamine-depleted primates: evidence for a loss of functional segregation within basal ganglia circuits. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4056-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poizner H, Feldman AG, Levin MF, Berkinblit MB, Hening WA, Patel A, Adamovich SV. The timing of arm-trunk coordination is deficient and vision-dependent in Parkinson's patients during reaching movements. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:279–292. doi: 10.1007/s002210000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MK, Lemay M, Squire LM, Shimansky YP, Stelmach GE. Control of aperture closure initiation during reach-to-grasp movements under manipulations of visual feedback and trunk involvement in Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 2010;201:509–525. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-2064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand MK, Smiley-Oyen AL, Shimansky YP, Bloedel JR, Stelmach GE. Control of aperture closure during reach-to-grasp movements in Parkinson's disease. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0073-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Patel JC, Cragg SJ. Dopamine release in the basal ganglia. Neuroscience. 2011;198:112–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.08.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice NJ, Tunik E, Grafton ST. The anterior intraparietal sulcus mediates grasp execution, independent of requirement to update: new insights from transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8176–8182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1641-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzolatti G, Matelli M. Two different streams form the dorsal visual system: anatomy and functions. Exp Brain Res. 2003;153:146–157. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1588-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Jahanshahi M, Krack P, Litvan I, Macias R, Bezard E, Obeso JA. Initial clinical manifestations of Parkinson's disease: features and pathophysiological mechanisms. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1128–1139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage JI, Mark MH. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson's disease in the elderly. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:583–589. doi: 10.1007/BF02599289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santello M, Soechting JF. Gradual molding of the hand to object contours. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1307–1320. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettino LF, Adamovich SV, Hening W, Tunik E, Sage J, Poizner H. Hand preshaping in Parkinson's disease: effects of visual feedback and medication state. Exp Brain Res. 2006;168:186–202. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schettino LF, Adamovich SV, Poizner H. Effects of object shape and visual feedback on hand configuration during grasping. Exp Brain Res. 2003;151:158–166. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]