Abstract

Thymic epithelial cells (TECs) are the key components in thymic microenvironment for T cells development. TECs, composed of cortical and medullary TECs, are derived from a common bipotent progenitor and undergo a stepwise development controlled by multiple levels of signals to be functionally mature for supporting thymocyte development. Tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family members including the receptor activator for NFκB (RANK), CD40, and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) cooperatively control the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance establishment. In addition, fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), Wnt, and Notch signals are essential for establishment of functional thymic microenvironment. Transcription factors Foxn1 and autoimmune regulator (Aire) are powerful modulators of TEC development, differentiation, and self-tolerance. Dysfunction in thymic microenvironment including defects of TEC and thymocyte development would cause physiological disorders such as tumor, infectious diseases, and autoimmune diseases. In the present review, we will summarize our current understanding on TEC development and the underlying molecular signals pathways and the involvement of thymus dysfunction in human diseases.

1. Introduction

Thymus, as a primary lymphoid organ for T lymphocyte development and maturation, plays an essential role in keeping host cellular immune tolerance to self-antigens. Thymic epithelial cells (TECs) forming a 3-dimentional network critically shape T cell repertoire in thymus, though other antigen-presenting cells in the thymus were also involved [1]. Based on the location, TECs are divided into cortical TECs (cTECs) located in the outer cortex region and medullary TECs (mTECs) located in the inner medulla area, respectively. cTECs and mTECs play distinct roles in thymocyte positive and negative selections [1, 2]. Except for hyperplasia, thymomas, Nude syndrome, and thymic involution which occur in the thymus itself, the relationships of thymus dysfunction with other human diseases such as myasthenia gravis (MG), type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune diseases have been recognized [3, 4]. On the other hand, the thymus undergoes atrophy caused by several endogenous and exogenous factors such as aging, hormone fluctuations, and infectious agents, resulting in abnormal release of thymus-derived T cells and impaired host immunity [5]. In the present review, we will focus on our current understanding on TEC biology and the involvement of TEC dysfunction in human diseases.

2. Thymus Organogenesis and TEC Development

The rudimentary thymus arises from the endoderm of the third pharyngeal pouch around day 9 of embryonic development (E9) in mice. The thymic gland reaches its final anatomical location at about week 6 in the human fetus [6]. TECs are derived from nonhematopoietic cells which are negative for CD45 expression and positive for epithelial marker EpCAM. TECs are roughly divided into two groups—cTECs and mTECs, which are phenotypically and functionally different. cTECs and mTECs distinctively express different cytokeratin, in which most mTECs express cytokeratin 5 (K5) and K14 but low level of K8, whereas cTECs express K8 and K18 [7]. TECs that express both K5 and K8 (K5+K8+) are mainly located at the corticomedullary junction. They are part of cTECs or the immature progenitors for mTECs and cTECs. In addition, mTECs are positive for the expression of Ulex europaeus agglutinin-1 (UEA-1) on cell surface, but not Ly51 (UEA-1+Ly51−), while cTECs are UEA-1−Ly51+. With these markers, we can roughly distinguish mTECs and cTECs in immunofluorescence and flow cytometry assays. In addition, mature cTECs express high level of MHCII and protease β5t and thymus-specific serine protease (TSSP) participating in thymocyte positive selection, while mature mTECs express MHCII, CD80, autoimmune regulator (Aire) and tissue-restricted antigens (TRAs). Proteases Cathepsin-L and -S in mTECs mediate thymocyte negative selection. The major differences of cTECs and mTECs are briefly summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The major differences between cTECs and mTECs.

| cTECs | mTECs | |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Cortex | Medulla |

| Cytokeratin expression | K8, K18 | K5, K14 |

| Surface marker | Ly51, CD205 | UEA-1, CD80 |

| Maturation | MHCIIhi, β5t | MHCIIhi, CD80hi, Aire, TRAs |

| Proteases | β5t, Cathepsin-L, TSSP | IFN-γ-induced β5i, β1i, β2i |

| Cathepsin-L, S | ||

| T cell selection | Positive | Negative |

hiHigh expression; TSSP: thymus-specific serine protease; TRAs: tissue restricted antigens.

It has been reported that bipotent TEC precursors (TEPCs) could differentiate into both cTECs and mTECs [8–10]. The size of the TEC progenitor pool significantly controls the number of mature TECs and limits their recovery [11]. These TEPCs remained uncharacterized for some time. One recent study has shown that a group of TECs expressing cTEC marker CD205 represented TEPCs [12]. These progenitors first emerge as early as E11 when TECs just began Foxn1 expression, and they could generate both cTECs and Aire+ mTECs to establish a functional thymic microenvironment. In addition, the individual progenitors for cTECs and mTECs exist [13, 14]. mTECs highly expressing the tight-junction protein claudin-3 and claudin-4 (UEA-1+Cld3,4hi) may represent the progenitors specifically for Aire+ mTECs [14], while the progenitors for cTECs are phenotypically characterized as EpCAM+CD205+CD40− [15].

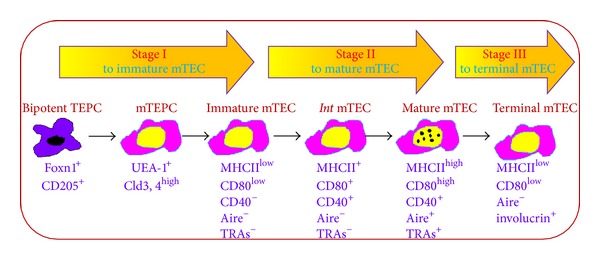

Generally, the development of mTECs is divided into 3 stages (Figure 1): bipotent TEPCs acquire mTEC sublineage differentiation orientation into immature mTECs expressing UEA-1 but low MHCII and costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD40. As mTECs develop into mature mTECs, MHCII CD80 and CD40 are upregulated concomitantly. mTECs in the middle mature stage do not express Aire and are functionally immature. The full mature mTECs are phenotypically characterized as high expression of MHCII and CD80 and Aire (UEA-1+MHCIIhiCD80hiAire+) as well as upregulation of Aire-dependent and Aire-independent TRAs participating in thymocyte negative selection [7]. Eventually, mature mTECs continue to develop into terminal differentiation stage by loss of CD80, MHCII, Aire, and TRAs expression, but with involucrin expression [16].

Figure 1.

mTEC development stages and the relevant markers. The development of mTECs is roughly divided into 3 stages: CD205+ TEPCs first develop into progenitors specifically for mTECs characterized as high expression of claudin-3 and claudin-4 (UEA-1+Cld3,4high). mTEPCs develop into immature mTEC expressing UEA-1 but low level of MHCII and costimulatory molecules CD80, and CD40. As mTECs develop further into the middle mature stage, MHCII, CD80, and CD40 expression are upregulated but still without Aire and tissue-restricted antigens (TRAs) expression. The full mature mTECs highly express MHCII, CD80 and Aire (UEA-1+MHCIIhighCD80highAire+) as well as upregulation of Aire-dependent and independent TRAs. Finally, mature mTECs enter into terminal differentiation stage as Aire−CD80int/lowMHCIIlow involucrin+ mTECs.

MHCIIhiCD80hiAire+ mTEC subset was previously considered to be the postmitotic end stage of mTECs which will be removed by apoptosis. However, accumulating evidence has shown that mTECs may continually develop beyond Aire+ stage. First, Aire−/− mice have no Hassall's corpuscles (HCs) structure [44] which is formed from terminally differentiated epithelial cells. The presence of HCs follows the Aire+mTECs during ontogeny [27], and it seems that these mTECs are developed beyond Aire+ cell stage [45]. By using a cell fate-tracing method, Nishikawa and his colleagues demonstrated that Aire+CD80hiMHCIIhi mTECs developed into Aire−CD80intMHCIIlow end stage [16]. Recently, by using a transgenic mouse model in which LacZ reporter gene was under the control of Aire promoter, Wang et al. showed that a single mTEC had 2 to 3 weeks' life cycle, in which Aire was expressed only once within possible maximal 1-2 days [46]. The loss of Aire expression is accompanied by downregulation of MHCII, CD80 and TRAs. In the final developmental stage, mTECs lose their nuclei to become HCs and specifically express desmogleins (DGs) 1 and 3 [46]. So the expression of Aire, CD80, and MHCII undergoes dynamic changes from low to high to low expression eventually. The end stage of mTECs expresses involucrin, a marker of terminally differentiated epithelium. Consistently, the presence of involucrin+mTECs followed the Aire+mTECs during ontogeny [27].

In contrast to mTECs, the developing stages of cTECs remain poorly defined. It is proposed that TEPCs firstly develop into progenitors specific for cTECs (cTEPCs) phenotypically characterized as EpCAM+CD205+CD40−MHCII−. Unlike the common bipotent progenitors, cTEPCs could self-renew after thymus injury is recovered [47]. Concomitant with cTECs maturation, the expressions of CD40, MHCII, and a series of proteases participating in thymocyte positive selection are upregulated [15, 48–50]. β5t thymoproteasome in cTECs is required for MHCI-restricted CD8+ T cells production, while cathepsin-L and TSSP are important for MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cells generation. Clearly, it is required to investigate the specific markers for cTEPCs and cTEC subsets in different developing stages, which will significantly help us to study cTEC development and the relevant mechanisms.

3. Molecules Control TEC Development

TEC development is a complex and continuous process under control of extrinsic and intrinsic signal regulatory network. Tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family members including the receptor activator for NFκB (RANK), CD40, and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) are especially involved in determining mTEC formation and development, while fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Wnt promote TEC expansion and functional maintenance. Transcription factors Foxn1 and Aire are essential for TEC development and functional maturation. The molecules involved in TEC development are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Molecules involved in TEC development.

| Family | Molecule | Receptor | Source | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | RANKL | RANK | Embryonic: LTi, DETC | Thymic medulla formation | [17, 18] |

| Postnatal: positively selected thymocytes | mTEC development | [19, 20] | |||

| CD40L | CD40 | Positively selected thymocytes | mTEC development | [19–22] | |

| mTEC proliferation | [19–22] | ||||

| LTα1β2, LIGHT | LTβR | Positively selected thymocytes | mTEC development | [23–25] | |

| Promote RANK signals | [26] | ||||

| mTEC terminal differentiation | [27] | ||||

|

| |||||

| FGFs | FGF8 | Pharyngeal region | Thymopoiesis | [28] | |

| FGF10 | FGFR2IIIb | Positively selected thymocytes | mTEC proliferation | [29] | |

| FGF7 | FGFR2IIIb | Positively selected thymocytes | mTEC and thymocyte Proliferation | [30, 31] | |

| Protect thymus damage | [32–34] | ||||

| Enhance thymopoiesis | [35, 36] | ||||

|

| |||||

| Wnt | wnt4 | Frizzled | TECs, fibroblast | Regulate Foxn1 expression | [37] |

| Thymopoiesis | [38–40] | ||||

|

| |||||

| Notch | Jagged, Delta | Notch | Thymocyte progenitor | TEC survival and development | [41–43] |

DETC: invariant Vγ5+ dendritic epidermal T cells; RA: retinoic acid.

3.1. The Effects of TNFR Family on TECs

It is highly recognized that TECs development and maturation are definitely dependent on their interaction with other cells in thymus such as thymocytes, fibroblasts, and mesenchymal cells. TNFR superfamily members and their ligands play an essential role in TECs especially mTECs development [51]. mTECs express a diverse set of TNFRs, and three of them including RANK, CD40, and LTβR have been proven to cooperatively control the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance establishment.

In the embryonic thymus, RANKL signals provided by CD4+CD3− lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells promote CD80−Aire−mTEC developing into CD80+Aire+mTECs [17]. Invariant Vγ5+ dendritic epidermal T cells also made contribution to the development of Aire+ mTEC development through providing RANKL [18]. In the postnatal thymus, RANKL signal is provided mainly by positively selected CD4+ T cells [19, 20]. Disruption of the RANKL-RANK signaling in the postnatal thymus leads to reduction of mature UEA-1+CD80hiMHCIIhi mTECs. In contrast, mice deficient for osteoprotegerin (OPG, a decoy receptor for RANKL) developed thymic hyperplasia and had more mature mTECs [20]. Transplantation of RANKL−/− thymus or transferring their splenocytes to immune deficient mice caused severe inflammatory cell infiltration and abundant production of autoimmune antibody [17, 19]. So the abnormality of RANKL-RANK signaling results in mTEC development arrest and the failure of T cells for self-tolerance.

CD40L-CD40 signaling pathway is also essential for mTEC development. CD40- or CD40L-deficient mice had obviously less mature mTECs and showed an autoimmune phenotype. Although the defects are less severe compared to RANK-deficient mice, CD40−/−RANKL−/− double deficient mice displayed a greater reduction in mature mTECs and more severe autoimmune disease, implying that RANK and CD40 act cooperatively in modulation of thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance [19–21]. In the postnatal thymus, CD40L signal provided by positively selected thymocytes (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) promotes mTEC proliferation [22].

In the thymus, LTβR is mainly expressed on thymic stromal cells other than T and B lymphocytes. Two ligands for LTβR are discovered: LTα1β2 and LIGHT, in which the former consists of LTα and LTβ subunits. The mature single positive thymocytes are the main source for LTβR ligands in the thymus [21]. Mice deficient in LTβR, its ligands, or downstream signal molecule nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (Nik) caused defects of thymic medulla development including disorganized medullary architecture, significant reduction in overall mTECs, and retention of T cell maturation with autoimmune disease [23–25]. However, there is still controversy in the role of LTβR in Aire and TRAs expression. Previous work showed that lymphotoxin signaling is required for Aire and Aire-dependent as well as Aire-independent TRA expression [52]. The following research claimed that lymphotoxin signaling does not regulate Aire and TRAs expression in mTECs [53]. LTα- or LTβ-deficient mice showed normal CD80, CD40, and Aire as well as TRAs expression despite reduced medulla area. The distribution of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and DCs in the thymus was also not affected [53, 54]. The inconsistent results regarding lymphotoxin signaling and Aire expression might be due to different TCR transgenic mouse models and the different detecting measures used in those studies [55], which need to be clarified in the future. One recent study showed that in embryonic mTEC development, the LTβR signal upregulated RANK expression in the thymic stroma, thereby promoting RANK signaling and mTEC differentiation [26]. Continued mTEC development into the involucrin+ stage also requires the activation of the LTα-LTβR signal provided by mature thymocytes [27]. Meanwhile, LTβR signals could indirectly influence mTEC development through regulating other stromal cells like MTS15+ fibroblasts which express the highest LTβRl than TECs [54].

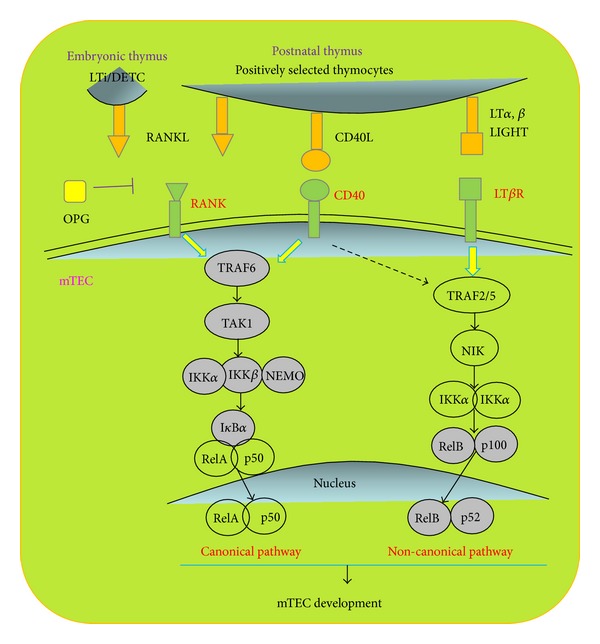

The signaling pathway downstream of RANK, CD40, and LTβR is usually NF-κB signal [56]. In the thymus, NFκB1 and RelA are mainly localized in cortical areas, whereas NFκB2, c-Rel and RelB are in the medulla [57]. Both canonical and noncanonical NF-κB signal pathways regulate mTEC development [25]. RANK and CD40 initiate activation of the classical NF-κB pathways via TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6). TRAF6-deficient mice showed severe destruction of medullary architecture and loss of UEA-1+mTECs [58]. In classical NF-κB pathways, TRAF6 activates TGF-β activating kinase 1 (TAK1), which in turn activates the IKK complex composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO. The IKK complex phosphorylates IkBα for degradation, leading to translocation of the RelA/p50 complex to the nucleus. In addition, RANK, CD40, and LTβR signaling could elicit nonclassical NF-κB pathways via TRAF2/5 to activate p52/RelB [59]. IKKα is phosphorylated by NIK and in turn triggers p100 partial degradation to p52 and then translocation to the nucleus together with RelB. Mice deficient of genes in nonclassical NF-κB pathways including NIK, IKKα, and RelB had abnormal thymus development with reduced UEA-1+ and/or Aire+ mTECs [60–64]. p52 deficiency results in less significant damage with little reduction in UEA-1+ and CD80hi mTEC but with no obvious medullary architecture changes [65]. The effects and pathways of TNFRs on TECs are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The effects and signaling pathways of TNFRs on TECs. Tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) including the receptor activator for NFκB (RANK), CD40, and lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) signalings is especially important for mTEC formation and development. In the embryonic thymus, RANKL is provided by CD4+CD3− lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells and Invariant Vγ5+ dendritic epidermal T cells, while in the postnatal thymus, RANKL, CD40L, and LTβR ligands LTα, LTβ, and LIGHT are provided exlusively by positively selected mature T cells. Canonical and noncanonical NF-κB signal pathways are the major downstream of RANK, CD40, and LTβR. In classical NF-κB pathways, TNFR-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) activates TGF-β activating kinase 1 (TAK1), which in turn activates the IKK complex composed of IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO. The IKK complex phosphorylates IkBα for degradation, leading to translocation of the RelA/p50 complex to the nucleus. Nonclassical NF-κB pathways activate p52/RelB via TRAF2/5. IKKα is phosphorylated by NIK, which in turn triggers p100 partial degradation to p52 and then translocation to the nucleus together with RelB.

3.2. The Effects of FGFs on TECs

FGFs boost thymopoiesis and promote differentiation by working on both thymocytes and TECs. FGF8 influences TECs indirectly by regulating neural crest cells (NCCs) survival and differentiation; therefore, FGF8 deficiency and NCCs deletion result in similar manifestation [28]. FGF7 and FGF10 conduct mainly as nutritional factors promoting TEC proliferation but not differentiation. Loss of FGF10 causes defects of thymus development and alters thymic cytokeratin expression pattern [29]. Development of thymus in mice deficient of FGF receptor R2-IIIb (FGFR2IIIb), receptor for FGF7 and FGF10, is blocked at E12.5 when TECs just emerge. However, FGF signal is not always enhancing TECs. When thymus and parathyroid glands are derived from the third pharyngeal pouch endoderm, localized inhibition of FGF signaling is essential for normal Gcm2, Bmp4 and Foxn1 expression and thymus/parathyroid detachment [66].

FGF7 is known as keratinocyte growth factor (KGF). Mature CD4+ and CD8+ thymocytes and fibroblasts are the main source for KGF in the thymus. KGF acts on both thymocytes and TECs, promoting their proliferation and function [30]. Applying KGF into RAG-deficient mice increased medullary compartment [31]. Administration of KGF protects the thymus against damage from radiation or graft-versus-host disease thus enhancing immune reconstitution after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [32–34]. KGF attenuates thymic aging in elderly individuals, protects medullary architecture, and promotes T cell production [35, 36]. KGF regulates a series of genes associated with TEC function and T cell development including BMP2, BMP4, Wnt5b, and Wnt10b via activation of p53 and NF-κB signal pathway [30].

3.3. The Effects of Wnt and Notch on TECs

Wnt receptors are exclusively expressed on TECs and Wnt regulates Foxn1 expression in the thymus [37]. Wnt4 is predominantly produced by TECs including both mTECs and cTECs [38]. Wnt4 controls thymopoiesis and thymus size by regulating TEC, thymocyte, and their progenitor proliferation [38, 39]. Wnt4 protects TECs from dexamethasone-induced injury [40]. Overexpression of DKK1, an inhibitor of Wnt4 in TECs, leads to thymic atrophy, reduction of TEPCs, and decreased TEC proliferation, features similar to thymic aging [67]. Therefore, Wnt4 becomes an indication for thymic senescence [68]. With ageing, the expression of Wnt4 and its downstream target Foxn1 is downregulated. On the other hand, one of the Wnt4 target gene, connective tissue growth factor, is involved in a negative feed-back loop suppressing Wnt expression, which is important for initiation of thymic senescence [69]. Thus, Wnt plays an important role in the thymic aging.

Development of both TECs relies on cell-cell interactions between the developing T-lymphocytes and the thymic epithelium. Such interdependency between thymocytes and TECs is often referred to as “thymic crosstalk.” Notch signaling represents one important molecular example for thymic crosstalk. In the thymus, both TECs and thymocytes express various Notch receptors and their ligands [70]. It is widely accepted that Notch ligands expressed on TECs are essential for T cell lineage commitment and maturation [71–73]. Further studies focused on the opposite direction of the crosstalk in which Notch activation played an essential role in TEC development. Jagged and Delta proteins are the main ligands for Notch receptor. Jagged2 gene mutant mice display defects in thymic morphology and impaired differentiation of γδT cells [41]. In fetal thymic organ culture system, B cells enforced to express Delta-like-1 could efficiently induce TECs development to establish three-dimensional architecture of thymic environment [42]. However, overactivation of Notch signaling also causes regression of the thymus. Targeted expression of Jagged1 in the thymocyte progenitors leads to thymic atrophy by induction of apoptosis of TECs [43]. Accordingly, an increase in Notch and Delta expression in aging thymus was noticed [74]. The molecule regulating networks involved in the role of Notch in TECs need to be studied.

3.4. The Effects of Foxn1 on TECs

Transcription factor Foxn1 plays a crucial role in TEC development. Mice deficient in Foxn1 (Foxn1nu/nu, nude mice) have atrophic thymus and few T cells in the periphery, leading to severe immune deficiency [75]. Foxn1 expression was first detectable on E11.25 in mice, the stage between thymus anlage formation and TEC development [88]. Foxn1, expressing on almost all TECs, regulates mTEC and cTEC differentiation and function in the fetal and adult thymus [78]. In Foxn1nu/nu mice, the earliest stage of TEC development was not impaired, in which the common progenitors could persist even in the postnatal thymus. However, thymus development was arrested after initial formation of the organ anlage (about E12.0 in mice) without hematopoietic precursor colonization [9, 76]. Foxn1Δ/Δ mice with a hypomorphic Foxn1 allele, lacking exon 3 of Foxn1, had a highly cystic thymus, containing no discernible cortical or medullary regions [79]. In mouse models with conditional deletion of Foxn1, ubiquitous deletion of Foxn1 after birth, caused dramatic thymic atrophy in 5 days with more severe defects in mTECs (especially the MHCIIhiUEA-1hi mature population) than cTECs [80]. It was demonstrated that aging-related loss of Foxn1 caused thymic epithelial cysts in medulla and perturbed negative selection [81]. Recently, it is demonstrated that Foxn1 is required for stable entry into both the cortical and medullary TEC development lineage in Foxn1 dosage-dependent manner [77]. Overexpression of Foxn1 attenuated age-induced thymic involution. In old Foxn1 transgenic mice, age-associated thymic atrophy was diminished, and the total number of EpCAM+ and MHCIIhi TECs was higher [82]. The accumulated studies collectively suggest that Foxn1 is a powerful regulator of TEC development on multiple stages and respects (Table 3): (1) Foxn1 is dispensable for earliest progenitors (TEPCs) presence [75, 77]; (2) Foxn1 is required for the differentiation from TEPCs to cTEC and mTEC sublineages; (3) Foxn1 participates in TEC proliferation [83, 84] and terminal differentiation [77, 85, 86]; (4) Foxn1 regulates the differentiation of TEC sublineages in postnatal thymus and aging. In addition to the function in regulating TEC development, Foxn1 also contributes to the vascularization of the murine thymus. In the nude thymus, CD31+ endothelial cells are not detected in the epithelial region [87], indicating that Foxn1 may indirectly regulate TEC and thymocyte development via controlling thymic vascularization.

Table 3.

Foxn1 regulates multiple TEC development stages.

| Capability | Regulation aspects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Dispensable | TEPCs appearance | [75–77] |

| TEC fate-choice | [77] | |

| Medullary sublineage divergence | [77] | |

|

| ||

| Indispensable | TEPCs into cTEC and mTEC sub-lineage | [77] |

| TECs differentiation | [76–82] | |

| TECs proliferation | [83, 84] | |

| TECs termination | [77, 85, 86] | |

| Thymic vascularization | [87] | |

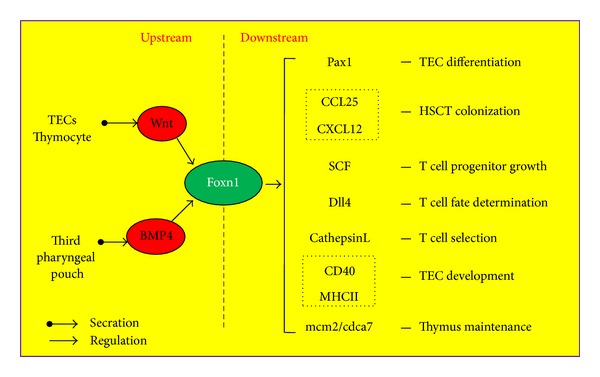

Foxn1 directly or indirectly regulates a series of genes involved in diverse aspects of thymus development and function [77]. Meanwhile, the expression and maintenance of Foxn1 gene in thymus are strictly under control [77]. The regulation network of upstream and downstream Foxn1 is briefly summarized in Figure 3. Pax1, expressed on the third pharyngeal pouch at E9.5 and essentially regulating TECs differentiation and proliferation, is Foxn1-dependent [89]. CCL25 and CXCL12, modulating hematopoietic stem cell localization in the thymus and stem cell factor (SCF), promoting T cell progenitor growth, were undetectable in Foxn1-deficient thymus [90–92]. Foxn1 deficiency also caused diminishment of Delta-like-4, ligand for Notch which controls hematopoietic stem cells specifically differentiated into early T cell progenitors [91, 93]. In addition, CathepsinL, CD40, and MHCII involved in TEC development and function are regulated by Foxn1 directly or indirectly [77]. Importantly, it is identified that Foxn1 regulates development of TECs and thymocytes through mcm2/cdca7 axis in zebrafish thymus [92].

Figure 3.

The molecular regulating network of Foxn1 in TECs. Foxn1 in TECs regulates a series of genes involved in the thymus development and function, and the expression of Foxn1 itself is strictly under control. Wingless (Wnt), provided by TECs and thymocytes, positively regulate Foxn1 expression in TECs. Bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) expressed in the third pharyngeal pouch modulate Foxn1 expression during fetal thymopoiesis. Genes are regulated by Foxn1 in TECs are determined so far: Pax1, regulating TEC differentiation and proliferation during thymopoiesis; CCL25 and CXCL12, for hematopoietic stem cell localization in the thymus; SCF, Dll4 and CathepsinL, participating in T cell development and selection; CD40 and MHCII, involved in TEC development and function.

Wnt and bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) are two main regulators upstream of Foxn1 gene. In the thymus, mostly Wnt4 and Wnt5b, produced by TECs and thymocytes, regulate Foxn1 expression in TECs through both autocrine and paracrine manners [37]. Overexpression of Noggin, an antagonist of BMP4 in TECs, leads to atrophic thymus and small number of thymocytes [94]. In the fetal thymic organ culture, BMP4 promotes Foxn1 expression on TECs and thereby improving thymic microenvironment for thymopoiesis [95].

3.5. The Effects of Aire on TECs

Aire is not only a marker for mature mTECs but also regulates mTEC development and differentiation (reviewed in [96]). Aire-deficient mice showed morphological changes in medullary components with decreased mTECs [44]. It is demonstrated that the numbers of mTECs expressing involucrin, a marker for terminal differentiated epithelium, were reduced in the Aire-deficient thymus [20]. The most important function of Aire is regulating expression of a panel of peripheral self-antigens in mTECs and promotes the antigen presentation ability of mTECs, participating in T cell negative selection and selftolerance establishment [97]. The mRNA levels of Aire in mTECs could also determine the expression of peripheral tissue antigen genes [98]. Aire deficiency caused a severe autoimmune disease manifestation with inflammatory cell infiltration in multiple organs and autoimmune antibody production [99, 100]. So far, three main manners are proposed for Aire regulating TRAs expression [101], which are summarized in Table 4: (1) Aire as a classical transcription factor directly initiates transcription of target genes; (2) Aire increases TRAs expression nonspecifically by loosening up the chromatin structure; (3) Aire functions through epigenetic modification. Aire could recognize epigenetic site of unmethylated histone 3. Following demethylation, Aire enhances target gene transcription via either itself directly or recruiting other transcriptional activators indirectly.

Table 4.

Models of Aire regulate TRAs expression.

| Model | Classical transcription factor | Random transcriptional activator | Epigenetic tag recognition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manner | Bind to promoter of target genes initiating the transcription of master transcription factors | Loosening the chromatin structure | Bind modified histones |

|

| |||

| Evidence | DNA binding domain activating transcription Recruit transcriptional molecules |

DNA accessibility function DNA sequences recognition |

Demethylation histone 3 interact with transcription cofactors |

Recent reports indicated that Aire also controlled the expression of microRNAs in mTECs, which in turn play a crucial role in maintaining thymic microenvironments [102, 103]. Giraud and colleagues found that Aire could induce transcription of target genes by unleashing stalled RNA polymerase in mTECs [104]. In addition, an increase of mTEC expressing truncated Aire protein was observed in Aire-deficient thymus, indicating that these mTECs would be eliminated in wild-type thymus and shed light on Aire's proapoptotic activity [105]. Overexpression of Aire in an mTEC cell line caused overt apoptosis [106]. The mechanism of this proapoptotic activity is in part associated with nuclear translocation of stress sensor and proapoptotic protein GAPDH [107].

4. Thymic Dysfunction and Human Diseases

The major biological function of the thymus is to generate a diverse repertoire of T cells to constitute an important part in host adaptive immune system against foreign pathogens, while thymus also plays a critical role in self-tolerance via thymic negative selection and the production of Treg cells. TECs are the most important components in thymic microenvironment supporting thymocyte development and self-tolerance establishment. Since the thymus plays a key role in keeping balance between host immunity and tolerance, it is obvious that thymic dysfunction causes a diversity of diseases in humans (Table 5).

Table 5.

Thymic dysfunction and human diseases.

| Level | Thymic dysfunction | Immunity | Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular | Aire gene mutation | Autoimmunity | APECED |

| Foxp3 gene mutation | Autoimmunity | IPEX | |

|

| |||

| Cellular | Thymic epithelial tumor | Deficiency/autoimmunity | Thymomas |

| Thymic epithelial tumor | Deficiency | Thymic carcinoma | |

| Treg dysfunction | Autoimmunity | IBD | |

|

| |||

| Individual | Thymus infection/injury | Deficiency | Infectious diseases: |

| AIDS (HIV) | |||

| measles (measles virus) | |||

| Ebola infection (Ebola virus) | |||

| syphilis (bacteria) | |||

| Absence of self-tolerance | Autoimmunity | Autoimmune diseases: | |

| myasthenia gravis | |||

| type 1 diabetes | |||

| autoimmune thyroiditis | |||

| rheumatoid arthritis | |||

| multiple sclerosis | |||

| autoimmune myocarditis | |||

| Graves' disease | |||

4.1. Thymus Tumors

Thymus tumors are scarce. Thymomas and thymic carcinomas are two major epithelial tumors of the thymus. Thymomas are neoplasms arising from TECs, usually with organotypic features (have normal thymus), numerous maturing thymocytes, and autoimmune syndromes such as myasthenia gravis (MG). Thymic carcinomas are malignant epithelial tumors with invariability and invasiveness and without organotypic feature and autoimmune disease [108].

4.2. Diseases Related to Immune Deficiency

Abnormality of the thymus is always concomitant with lower production of functional T cells and leads to immunodeficiency. Immunodeficiency in hosts means higher susceptibility to pathogens infection including viruses, bacteria, and protozoa, as well as decreases in antitumor immunity. Abnormalities in TEC development lead to dysfunction of T cells which could cause chronic inflammatory disease. Targeted gp39 (CD40L) overexpression in thymocytes caused loss of cTECs and mTEC expansion, with decline in thymocyte numbers and morphologic features of chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [109].

4.3. Autoimmune Diseases

Central self-tolerance is established in the thymus by at least two main mechanisms: (1) negative selection—clonal deletion of self-antigen reactive T cells (2) generation of self-antigen-specific natural regulatory T cells (nTregs) to downregulate immune response. Impairment or breakdown of the thymic self-tolerance plays a primary role in the development of some autoimmune diseases. More and more evidence showed the correlation between thymus dysfunction in self-tolerance and autoimmune diseases.

In humans, Aire mutation results in autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED), also known as autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome type 1 (APS-1). APECED is a rare systemic autoimmune disease characterized by chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis, hypoparathyroidism, and adrenal insufficiency. Different from many other autoimmune diseases, APECED is caused by a single gene mutation [110]. APECED is the first time for us to find the important autoimmune regulator Aire [111]. In mature mTECs, Aire drives organ-specific antigens expression on mTECs and mediates negative selection of autoreactive T cells. Therefore, failure of central tolerance based on tissue-restricted antigens expression could result in a series of autoimmune diseases in multiple organs.

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a neuromuscular autoimmune disease characterized as muscle weakness and fatigability caused by T cell-dependent autoantibodies against neuromuscular junction. In MG patients, autoantibodies could directly attack muscle acetylcholine receptors (AChR), muscle-specific receptor tyrosine kinases (MuSK), and even muscles themselves. The exact trigger of MG is unclear; however, it is certain that alteration of the thymus and TECs is involved in MG pathogenesis. TEC dysfunction contributes to MG pathogenesis in several ways: defects in negative selection by producing AChR-reactive CD4+ T cells; overexpression of various cytokines and chemokines to recruit peripheral lymphocytes to the thymus leading to thymic hyperplasia, a hallmark of MG [112, 113].

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease resulting from destruction of pancreatic islet β cells. It is widely accepted that the absence or failure of immune tolerance to islet β cells is the primary cause for development of T1D. Previous results have demonstrated that all the members of insulin gene family were expressed in mTECs [114]. Insulin1 and insulin2 are two Aire-dependent TRAs expressed in mTECs. Decreased expression of T1D-related antigens in the thymus or Aire deficiency would break down the self-tolerance to islet β cells leading to the development of T1D [115]. Other autoimmune diseases related to abnormalities of self-tolerance by organ-specific antigens expression on mTECs are autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis (MS), autoimmune myocarditis, Graves' disease, and so forth.

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells are developed in the thymus as negative regulation candidate to control peripheral self-tolerance. Dysfunction of the negative regulatory system mediated by nTreg cells could also play a crucial role in the development of autoimmune diseases. Loss of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells alone is sufficient to induce autoimmune reaction. In humans, mutation of FOXP3, a specific transcription factor for nTreg cells, will cause a failure of nTreg cell development and will subsequently cause X-linked immunodeficiency syndrome IPEX (X-linked syndrome, immune abnormality, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy) [116]. Dysfunction of nTreg cells means loss of balance between CD4+ T helper cells subsets (Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg) which is supposed to participate in other autoimmune diseases, such as MG [117] and T1D [115]. It is reported that a direct role for CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in restraining B cell autoantibody production and defects in CD4+CD25+ Treg cells may be crucial to the development of primary biliary cirrhosis [118]. Defective thymic selection with higher Th1 response and lower nTreg cells numbers spontaneously develops IBD-like colitis, suggesting that the impaired control of self-reactive T cells by nTreg cells could result in autoimmune diseases [119].

In conclusion, thymus (TECs) dysfunction participates in autoimmune disease development mainly through the abnormality in the following two aspects: (1) self-tolerance established by Aire-mediated tissue-restricted antigens expression on mTECs; (2) negative regulatory system formed by CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ nTreg cells.

4.4. Thymus Defects Caused by Diseases

More and more observations have implied that thymus is very sensitive and fragile to many physiological disorders such as infection, autoimmune diseases, and aging [120]. A variety of infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and protozoa would cause thymic atrophy characterized largely by the depletion of thymocytes (especially CD4+CD8+ T cells). Thymic microenvironment of epithelial network is also affected by loss of mTECs and cTECs compartment, accumulation in extracellular matrix deposition. In HIV-infected children and adults, thymic dysfunction and involution including thymocyte apoptosis and severe TEC damage occur during disease progression [121, 122]. Thymic disorders are very common in some autoimmune diseases. Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a connective tissue autoimmune disease related to self-tolerance failure. Thymus hyperplasia is present in a significant number of SSc patients. Moreover, in advanced SSc patients, thymus involution occurred [123]. In addition, thymic hyperplasia is commonly observed in Graves' disease [124] and MG [113].

Thymus involution remains a significant marker for senescence. In aged mice or humans, thymus size is reduced, as well as TECs, thymocytes, and peripheral T cells. Aged thymus has disorganized thymic architecture, increased cavity and cysts, and more fibroblast and fatty cells [74, 125, 126]. Besides, the thymus is sensitive to malnutrition. Protein energy, vitamin, trace element, and Zn2+ deficiencies could cause multiple thymic defects including thymic atrophy [127]. Accordingly, thymus defects lead to lower functional T cells production and self-tolerance breakdown, which could in turn exacerbate the disease progression. Therefore, thymus has been proven extremely important in maintenance of host immunity and self-tolerance and protection from the occurrence and progression of many diseases and aging.

5. Concluding Remarks

The fundamental function of thymus is to establish host immunity with self-tolerance. TECs are the most important components in thymic microenvironment supporting thymocytes development and directing central tolerance. Multiple signals and cellular interactions are required for the maturation, expansion, and maintenance of thymic epithelial compartments. TNFR signals including RANKL, CD40L, and lymphotoxin cooperatively control the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance establishment, while FGFs, Wnt, and Notch signals are essential for TEC and thymocyte expansion and functional maintenance. Foxn1 is a powerful modulator of TECs lineage progression in fetal and adult thymus in a dose-dependent manner. Aire expression in mature mTECs drives mTEC development and directs self-tolerance establishment. Thymic dysfunction is associated with many diseases including tumors, infectious diseases, and autoimmune diseases. On the other hand, the thymus is a primary target organ for many physiological disorders such as pathogen infections, autoimmune diseases, aging, and malnutrition. Since the thymus plays an important role in immunity and diseases, understanding the mechanisms for TEC differentiation and function would offer the possibility for the clinical application of “modification of thymus function” to improve our cellular immunity in physiological and pathological conditions such as infections, autoimmune diseases, and aging.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Douglas Corley for his careful reading of the paper. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2010CB945301, 2011CB710903, Yong Zhao) and the National Natural Science Foundation (C81072396, U0832003, Yong Zhao; C31200681, Haiying Luo).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Anderson G, Takahama Y. Thymic epithelial cells: working class heroes for T cell development and repertoire selection. Trends in Immunology. 2012;33(6):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerder S, Viret C, Luche H, Ardouin L, Malissen B. Differential processing of self-antigens by subsets of thymic stromal cells. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2012;24(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaïdane H, Sané F, Hiar R, et al. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: enterovirus, thymus and type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2012;168(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romano R, Palamaro L, Fusco A, et al. From murine to human Nude/SCID: the thymus, T-Cell development and the missing link. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2012;2012:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/467101.467101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Meis J, Aurélio Farias-De-Oliveira D, Nunes Panzenhagen PH, et al. Thymus atrophy and double-positive escape are common features in infectious diseases. Journal of Parasitology Research. 2012;2012:9 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/574020.574020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghali WM, Abel-Rahman S, Nagib M, Mahran ZY. Intrinsic innervation and vasculature of pre- and post-natal human thymus. Acta Anatomica. 1980;108(11):115–123. doi: 10.1159/000145289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexandropoulos K, Danzl NM. Thymic epithelial cells: antigen presenting cells that regulate T cell repertoire and tolerance development. Immunologic Research. 2012;54(1-3):177–190. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossi SW, Jenkinson WE, Anderson G, Jenkinson EJ. Clonal analysis reveals a common progenitor for thymic cortical and medullary epithelium. Nature. 2006;441(7096):988–991. doi: 10.1038/nature04813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleul CC, Corbeaux T, Reuter A, Fisch P, Mönting JS, Boehm T. Formation of a functional thymus initiated by a postnatal epithelial progenitor cell. Nature. 2006;441(7096):992–996. doi: 10.1038/nature04850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Sun L, Zhao Y. Thymic epithelial progenitor cells and thymus regeneration: an update. Cell Research. 2007;17(1):50–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkinson WE, Bacon A, White AJ, Anderson G, Jenkinson EJ. An epithelial progenitor pool regulates thymus growth. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(9):6101–6108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baik S, Jenkinson EJ, Lane PJ, Anderson G, Jenkinson WE. Generation of both cortical and Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial compartments from CD205+ progenitors. European Journal of Immunology. 2013;43(3):589–594. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodewald H-R, Paul S, Haller C, Bluethmann H, Blum C. Thymus medulla consisting of epithelial islets each derived from a single progenitor. Nature. 2001;414(6865):763–768. doi: 10.1038/414763a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamazaki Y, Fujita H, Kobayashi T, et al. Medullary thymic epithelial cells expressing Aire represent a unique lineage derived from cells expressing claudin. Nature Immunology. 2007;8(3):304–311. doi: 10.1038/ni1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakib S, Desanti GE, Jenkinson WE, Parnell SM, Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G. Checkpoints in the development of thymic cortical epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(1):130–137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishikawa Y, Hirota F, Yano M, et al. Biphasic Aire expression in early embryos and in medullary thymic epithelial cells before end-stage terminal differentiation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2010;207(5):963–971. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossi SW, Kim M-Y, Leibbrandt A, et al. RANK signals from CD4+3− inducer cells regulate development of Aire-expressing epithelial cells in the thymic medulla. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(6):1267–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts NA, White AJ, Jenkinson WE, et al. Rank signaling links the development of invariant γδ T cell progenitors and Aire+ medullary epithelium. Immunity. 2012;36(3):427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiyama T, Shimo Y, Yanai H, et al. The tumor necrosis factor family receptors RANK and CD40 cooperatively establish the thymic medullary microenvironment and self-tolerance. Immunity. 2008;29(3):423–437. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hikosaka Y, Nitta T, Ohigashi I, et al. The cytokine RANKL produced by positively selected thymocytes fosters medullary thymic epithelial cells that express autoimmune regulator. Immunity. 2008;29(3):438–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irla M, Hugues S, Gill J, et al. Autoantigen-specific interactions with CD4+ thymocytes control mature medullary thymic epithelial cell cellularity. Immunity. 2008;29(3):451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desanti GE, Cowan JE, Baik S, et al. Developmentally regulated availability of RANKL and CD40 ligand reveals distinct mechanisms of fetal and adult cross-talk in the thymus medulla. Journal of Immunology. 2012;189(12):5519–5526. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boehm T, Scheu S, Pfeffer K, Bleul CC. Thymic medullary epithelial cell differentiation, thymocyte emigration, and the control of autoimmunity require lympho-epithelial cross talk via LTβR. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;198(5):757–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venanzi ES, Gray DHD, Benoist C, Mathis D. Lymphotoxin pathway and aire influences on thymic medullary epithelial cells are unconnected. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(9):5693–5700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu M, Fu Y. The complicated role of NF-κB in T-cell selection. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2010;7(2):89–93. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouri Y, Yano M, Shinzawa M, et al. Lymphotoxin signal promotes thymic organogenesis by eliciting RANK expression in the embryonic thymic stroma. Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(9):5047–5057. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White AJ, Nakamura K, Jenkinson WE, et al. Lymphotoxin signals from positively selected thymocytes regulate the terminal differentiation of medullary thymic epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(8):4769–4776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bockman DE, Kirby ML. Dependence of thymus development on derivatives of the neural crest. Science. 1984;223(4635):498–500. doi: 10.1126/science.6606851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Revest J-M, Suniara RK, Kerr K, Owen JJT, Dickson C. Development of the thymus requires signaling through the fibroblast growth factor receptor R2-IIIb. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(4):1954–1961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossi SW, Jeker LT, Ueno T, et al. Keratinocyte Growth Factor (KGF) enhances postnatal T-cell development via enhancements in proliferation and function of thymic epithelial cells. Blood. 2007;109(9):3803–3811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-049767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erickson M, Morkowski S, Lehar S, et al. Regulation of thymic epithelium by keratinocyte growth factor. Blood. 2002;100(9):3269–3278. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alpdogan Ö, Hubbard VM, Smith OM, et al. Keratinocyte Growth Factor (KGF) is required for postnatal thymic regeneration. Blood. 2006;107(6):2453–2460. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi S, Blazar BR, Farrell CL, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor preserves normal thymopoiesis and thymic microenvironment during experimental graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2002;100(2):682–691. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Min D, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Protection from thymic epithelial cell injury by keratinocyte growth factor: a new approach to improve thymic and peripheral T-cell reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;99(12):4592–4600. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berent-Maoz B, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Signer RA, Dorshkind K. Fibroblast growth factor-7 partially reverses murine thymocyte progenitor aging by repression of Ink4a. Blood. 2012;119(24):5715–5721. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-400002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min D, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Kuro-o M, Holländer GA, Blazar BR, Weinberg KI. Sustained thymopoiesis and improvement in functional immunity induced by exogenous KGF administration in murine models of aging. Blood. 2007;109(6):2529–2537. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-043794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balciunaite G, Keller MP, Balciunaite E, et al. Wnt glycoproteins regulate the expression of FoxNI, the genes defective in nude mice. Nature Immunology. 2002;3(11):1102–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heinonen KM, Vanegas JR, Brochu S, Shan J, Vainio SJ, Perreault C. Wnt4 regulates thymic cellularity through the expansion of thymic epithelial cells and early thymic progenitors. Blood. 2011;118(19):5163–5173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-350553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heinonen KM, Vanegas JR, Lew D, Krosl J, Perreault C. Wnt4 enhances murine hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion through a planar cell polarity-like pathway. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019279.e19279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talaber G, Kvell K, Varecza Z, et al. Wnt-4 protects thymic epithelial cells against dexamethasone-induced senescence. Rejuvenation Research. 2011;14(3):241–248. doi: 10.1089/rej.2010.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang R, Lan Y, Chapman HD, et al. Defects in limb, craniofacial, and thymic development in Jagged2 mutant mice. Genes and Development. 1998;12(7):1046–1057. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masuda K, Germeraad WTV, Satoh R, et al. Notch activation in thymic epithelial cells induces development of thymic microenvironments. Molecular Immunology. 2009;46(8-9):1756–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beverly LJ, Ascano JM, Capobianco AJ. Expression of JAGGED1 in T-lymphocytes results in thymic involution by inducing apoptosis of thymic stromal epithelial cells. Genes and Immunity. 2006;7(6):476–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yano M, Kuroda N, Han H, et al. Aire controls the differentiation program of thymic epithelial cells in the medulla for the establishment of self-tolerance. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(12):2827–2838. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hale LP, Markert ML. Corticosteroids regulate epithelial cell differentiation and hassall body formation in the human thymus. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(1):617–624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, Laan M, Bichele R, Kisand K, Scott HS, Peterson P. Post-Aire maturation of thymic medullary epithelial cells involves selective expression of keratinocyte-specific autoantigens. Frontiers in Immunology. 2012;3, article 19 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rode I, Boehm T. Regenerative capacity of adult cortical thymic epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(9):3463–3468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118823109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murata S, Takahama Y, Tanaka K. Thymoproteasome: probable role in generating positively selecting peptides. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2008;20(2):192–196. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murata S, Sasaki K, Kishimoto T, et al. Regulation of CD8+ T cell development by thymus-specific proteasomes. Science. 2007;316(5829):1349–1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1141915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahama Y, Takada K, Murata S, Tanaka K. β5t-containing thymoproteasome: specific expression in thymic cortical epithelial cells and role in positive selection of CD8+ T cells. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2012;24(1):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akiyama T, Shinzawa M, Akiyama N. TNF receptor family signaling in the development and functions of medullary thymic epithelial cells. Frontiers in Immunology. 2012;3, article 278 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chin RK, Lo JC, Kim O, et al. Lymphotoxin pathway directs thymic Aire expression. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(11):1121–1127. doi: 10.1038/ni982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martins VC, Boehm T, Bleul CC. Ltβr signaling does not regulate aire-dependent transcripts in medullary thymic epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(1):400–407. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seach N, Ueno T, Fletcher AL, et al. The Lymphotoxin pathway regulates aire-independent expression of ectopic genes and chemokines in thymic stromal cells1. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(8):5384–5392. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu M, Brown NK, Fu Y-X. Direct and indirect roles of the LTβR pathway in central tolerance induction. Trends in Immunology. 2010;31(9):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Basak S, Hoffmann A. Crosstalk via the NF-κB signaling system. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2008;19(3-4):187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manley NR, Condie BG. Transcriptional regulation of thymus organogenesis and thymic epithelial cell differentiation. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2010;92:103–120. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)92005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Akiyama T, Maeda S, Yamane S, et al. Dependence of self-tolerance on TRAF6-directed development of thymic stroma. Science. 2005;308(5719):248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.1105677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Irla M, Hollander G, Reith W. Control of central self-tolerance induction by autoreactive CD4+ thymocytes. Trends in Immunology. 2010;31(2):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weih F, Carrasco D, Durham SK, et al. Multiorgan inflammation and hematopoietic abnormalities in mice with a targeted disruption of RelB, a member of the NF-κB/Rel family. Cell. 1995;80(2):331–340. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kajiura F, Sun S, Nomura T, et al. NF-κB-inducing kinase establishes self-tolerance in a thymic stroma-dependent manner. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(4):2067–2075. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lomada D, Lin B, Coghlan L, Hu Y, Richie ER. Thymus medulla formation and central tolerance are restored in IKKα −/− mice that express an IKKα transgene in keratin 5+ thymic epithelial cells. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(2):829–837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinoshita D, Hirota F, Kaisho T, et al. Essential role of IκB kinase α in thymic organogenesis required for the establishment of self-tolerance. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(7):3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burkly L, Hession C, Ogata L, et al. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature. 1995;373(6514):531–536. doi: 10.1038/373531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang B, Wang Z, Ding J, Peterson P, Gunning WT, Ding H-F. NF-κB2 is required for the control of autoimmunity by regulating the development of medullary thymic epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(50):38617–38624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606705200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gardiner JR, Jackson AL, Gordon J, Lickert H, Manley NR, Basson MA. Localised inhibition of FGF signalling in the third pharyngeal pouch is required for normal thymus and parathyroid organogenesis. Development. 2012;139(18):3456–3466. doi: 10.1242/dev.079400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Osada M, Jardine L, Misir R, Andl T, Millar SE, Pezzano M. DKK1 mediated inhibition of Wnt signaling in postnatal mice leads to loss of TEC progenitors and thymic degeneration. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009062.e9062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kvell K, Varecza Z, Bartis D, et al. Wnt4 and LAP2alpha as pacemakers of thymic epithelial senescence. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010701.e10701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Varecza Z, Kvell K, Talabér G, et al. Multiple suppression pathways of canonical Wnt signalling control thymic epithelial senescence. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2011;132(5):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Felli MP, Maroder M, Mitsiadis TA, et al. Expression pattern of Notch1, 2 and 3 and Jagged1 and 2 in lymphoid and stromal thymus components: distinct ligand-receptor interactions in intrathymic T cell development. International Immunology. 1999;11(7):1017–1025. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmitt TM, Ciofani M, Petrie HT, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. Maintenance of T cell specification and differentiation requires recurrent Notch receptor-ligand interactions. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200(4):469–479. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feyerabend TB, Terszowski G, Tietz A, et al. Deletion of Notch1 converts Pro-T cells to dendritic cells and promotes thymic B cells by cell-extrinsic and cell-intrinsic mechanisms. Immunity. 2009;30(1):67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hozumi K, Mailhos C, Negishi N, et al. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(11):2507–2513. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aw D, Taylor-Brown F, Cooper K, Palmer DB. Phenotypical and morphological changes in the thymic microenvironment from ageing mice. Biogerontology. 2009;10(3):311–322. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blackburn CC, Augustine CL, Li R, et al. The nu gene acts cell-autonomously and is required for differentiation of thymic epithelial progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(12):5742–5746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cordier AC, Heremans JF. Nude mouse embryo: ectodermal nature of the primordial thymic defect. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1975;4(2):193–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1975.tb02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nowell CS, Bredenkamp N, Tetélin S, et al. Foxn1 regulates lineage progression in cortical and medullary thymic epithelial cells but is dispensable for medullary sublineage divergence. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002348.e1002348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nehls M, Pfeifer D, Schorpp M, Hedrich H, Boehm T. New member of the winged-helix protein family disrupted in mouse and rat nude mutations. Nature. 1994;372(6501):103–107. doi: 10.1038/372103a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Su D-M, Navarre S, Oh W-J, Condie BG, Manley NR. A domain of Foxn1 required for crosstalk-dependent thymic epithelial cell differentiation. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(11):1128–1135. doi: 10.1038/ni983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cheng L, Guo J, Sun L, et al. Postnatal tissue-specific disruption of transcription factor FoxN1 triggers acute thymic atrophy. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(8):5836–5847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xia J, Wang H, Guo J, Zhang Z, Coder B, Su DM. Age-related disruption of steady-state thymic medulla provokes autoimmune phenotype via perturbing negative selection. Aging and Disease. 2012;3(3):248–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zook EC, Krishack PA, Zhang S, et al. Overexpression of Foxn1 attenuates age-associated thymic involution and prevents the expansion of peripheral CD4 memory T cells. Blood. 2011;118(22):5723–5731. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-342097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Itoi M, Kawamoto H, Katsura Y, Amagai T. Two distinct steps of immigration of hematopoietic progenitors into the early thymus anlage. International Immunology. 2001;13(9):1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.9.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen L, Xiao S, Manley NR. Foxn1 is required to maintain the postnatal thymic microenvironment in a dosage-sensitive manner. Blood. 2009;113(3):567–574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baxter RM, Brissette JL. Role of the Nude gene in epithelial terminal differentiation. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2002;118(2):303–309. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Janes SM, Ofstad TA, Campbell DH, Watt FM, Prowse DM. Transient activation of FOXN1 in keratinocytes induces a transcriptional programme that promotes terminal differentiation: contrasting roles of FOXN1 and Akt. Journal of Cell Science. 2004;117(part 18):4157–4168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mori K, Itoi M, Tsukamoto N, Amagai T. Foxn1 is essential for vascularization of the murine thymus anlage. Cellular Immunology. 2010;260(2):66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bennett AR, Farley A, Blair NF, Gordon J, Sharp L, Blackburn CC. Identification and characterization of thymic epithelial progenitor cells. Immunity. 2002;16(6):803–814. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Su D-M, Ellis S, Napier A, Lee K, Manley NR. Hoxa3 and Pax1 regulate epithelial cell death and proliferation during thymus and parathyroid organogenesis. Developmental Biology. 2001;236(2):316–329. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu C, Saito F, Liu Z, et al. Coordination between CCR7- and CCR9-mediated chemokine signals in prevascular fetal thymus colonization. Blood. 2006;108(8):2531–2539. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Calderón L, Boehm T. Synergistic, context-dependent, and hierarchical functions of epithelial components in thymic microenvironments. Cell. 2012;149(1):159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ma D, Wang L, Wang S, Gao Y, Wei Y, Liu F. Foxn1 maintains thymic epithelial cells to support T-cell development via mcm2 in zebrafish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(51):21040–21045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217021110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koch U, Fiorini E, Benedito R, et al. Delta-like 4 is the essential, nonredundant ligand for Notchl during thymic T cell lineage commitment. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2008;205(11):2515–2523. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bleul CC, Boehm T. BMP signaling is required for normal thymus development. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(8):5213–5221. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsai PT, Lee RA, Wu H. BMP4 acts upstream of FGF in modulating thymic stroma and regulating thymopoiesis. Blood. 2003;102(12):3947–3953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mathis D, Benoist C. Aire. Annual Review of Immunology. 2009;27:287–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gardner JM, Fletcher AL, Anderson MS, Turley SJ. AIRE in the thymus and beyond. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2009;21(6):582–589. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oliveira EH, Macedo C, Donate PB, et al. Expression profile of peripheral tissue antigen genes in medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) is dependent on mRNA levels of autoimmune regulator (Aire) Immunobiology. 2012;218(1):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ramsey C, Winqvist O, Puhakka L, et al. Aire deficient mice develop multiple features of APECED phenotype and show altered immune response. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002;11(4):397–409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Anderson MS, Venanzi ES, Klein L, et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science. 2002;298(5597):1395–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1075958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Danso-Abeam D, Humblet-Baron S, Dooley J, Liston A. Models of aire-dependent gene regulation for thymic negative selection. Frontiers in Immunology. 2011;2, article 14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Macedo C, Evangelista AF, Marques MM, et al. Autoimmune regulator (Aire) controls the expression of microRNAs in medullary thymic epithelial cells. Immunobiology. 2012;218(4):554–560. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zuklys S, Mayer CE, Zhanybekova S, et al. MicroRNAs control the maintenance of thymic epithelia and their competence for T lineage commitment and thymocyte selection. Journal of Immunology. 2012;189(8):3894–3904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Giraud M, Yoshid H, Abramson J, et al. Aire unleashes stalled RNA polymerase to induce ectopic gene expression in thymic epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(2):535–540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119351109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dooley J, Erickson M, Farr AG. Alterations of the medullary epithelial compartment in the aire-deficient thymus: implications for programs of thymic epithelial differentiation. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(8):5225–5232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gray D, Abramson J, Benoist C, Mathis D. Proliferative arrest and rapid turnover of thymic epithelial cells expressing Aire. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(11):2521–2528. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liiv I, Haljasorg U, Kisand K, Maslovskaja J, Laan M, Peterson P. AIRE-induced apoptosis is associated with nuclear translocation of stress sensor protein GAPDH. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2012;423(1):32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ströbel P, Hohenberger P, Marx A. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma: molecular pathology and targeted therapy. Journal of Thoracic Oncology. 2010;5(10, supplement 4):S286–S290. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f209a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Clegg CH, Rulffes JT, Haugen HS, et al. Thymus dysfunction and chronic inflammatory disease in gp39 transgenic mice. International Immunology. 1997;9(8):1111–1122. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.8.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vogel A, Strassburg CP, Obermayer-Straub P, Brabant G, Manns MP. The genetic background of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy and its autoimmune disease components. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2002;80(4):201–211. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0306-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Aaltonen J, Björses P, Perheentupa J, et al. An autoimmune disease, APECED, caused by mutations in a novel gene featuring two PHD-type zinc-finger domains. Nature Genetics. 1997;17(4):399–403. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Le Panse R, Bismuth J, Cizeron-Clairac G, et al. Thymic remodeling associated with hyperplasia in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity. 2010;43(5-6):401–412. doi: 10.3109/08916930903563491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mays J, Butts CL. Intercommunication between the neuroendocrine and immune systems: focus on myasthenia gravis. NeuroImmunomodulation. 2011;18(5):320–327. doi: 10.1159/000329491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geenen V. The thymic insulin-like growth factor axis: involvement in physiology and disease. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2003;35(11-12):656–663. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Geenen V. Thymus and type 1 diabetes: an update. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;98(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gambineri E, Torgerson TR, Ochs HD. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked inheritance (IPEX), a syndrome of systemic autoimmunity caused by mutations of FOXP3, a critical regulator of T-cell homeostasis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2003;15(4):430–435. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhu J, Paul WE. CD4 T cells: fates, functions, and faults. Blood. 2008;112(5):1557–1569. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-078154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tsuda M, Torgerson TR, Selmi C, et al. The spectrum of autoantibodies in IPEX syndrome is broad and includes anti-mitochondrial autoantibodies. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2010;35(3):265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ishimaru N, Yamada A, Kohashi M, et al. Development of inflammatory bowel disease in Long-Evans Cinnamon rats based on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell dysfunction. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(10):6997–7008. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Savino W. The thymus is a common target organ in infectious diseases. PLoS Pathogens. 2006;2(6, article e62) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020062.10.1371/journal.ppat.0020062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ye P, Kirschner DE, Kourtis AP. The thymus during HIV disease: role in pathogenesis and in immune recovery. Current HIV Research. 2004;2(2):177–183. doi: 10.2174/1570162043484898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kourtis AP, Ibegbu C, Nahmias AJ, et al. Early progression of disease in HIV-infected infants with thymus dysfunction. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(19):1431–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611073351904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ferri C, Colaci M, Battolla L, Giuggioli D, Sebastiani M. Thymus alterations and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology. 2006;45(1):72–75. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Murakami M, Hosoi Y, Negishi T, et al. Thymic hyperplasia in patients with Graves’ disease: identification of thyrotropin receptors in human thymus. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98(10):2228–2234. doi: 10.1172/JCI119032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cavallotti C, D’Andrea V, Tonnarini G, Cavallotti C, Bruzzone P. Age-related changes in the human thymus studied with scanning electron microscopy. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2008;71(8):573–578. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Aw D, Silva AB, Maddick M, von Zglinicki T, Palmer DB. Architectural changes in the thymus of aging mice. Aging Cell. 2008;7(2):158–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Savino W, Dardenne M. Nutritional imbalances and infections affect the thymus: consequences on T-cell-mediated immune responses. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2010;69(4):636–643. doi: 10.1017/S0029665110002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]