Abstract

Objective

The rate of alcohol drinking has been shown to predict impairment on cognitive and behavioral tasks. The current study assessed the influence of speed of alcohol consumption within a laboratory-administered binge on self-reported attitudes toward driving and simulated driving ability.

Method

Forty moderate drinkers (20 female, 20 male) were recruited from the local community via advertisements for individuals who drank alcohol at least once per month. The equivalent of four standard alcohol drinks was consumed at the participant’s desired pace within a two-hour session.

Results

Correlation analyses revealed that, after alcohol drinking, mean simulated driving speed, time in excess of speed limit, collisions, and reported confidence in driving were all associated with rapid alcohol drinking.

Conclusion

Fast drinking may coincide with increased driving confidence due to the extended latency between the conclusion of drinking and the commencement of driving. However, this latency did not reduce alcohol-related driving impairment, as fast drinking was also associated with risky driving.

Keywords: alcohol drinking, binge drinking, simulated driving, risk-taking

INTRODUCTION

One of the hallmarks of problematic drinking is drinking too much too fast (Leeman et al., 2010). The level of intoxication produced by an alcoholic beverage is determined partly by the speed at which it was consumed (Higgs et al., 2008), suggesting that fast drinking would result in higher levels of impairment. Fast rates of alcohol consumption have been associated with performance impairment on cognitive and psychomotor tasks (Jones and Vega, 1973; Moskowitz and Burns, 1976).

One behavior characterized by deliberate rapid alcohol consumption is binge drinking, which produces a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08% within a two-hour period (NIAAA, 2004). A binge typically includes five drinks for men and four drinks for women. An estimated 80% of impaired driving incidents occur as a result of binge drinking (Quinlan et al., 2005). Additionally, binge drinkers are 14 times more likely to drive while under the influence of alcohol than non-bingeing individuals (Naimi et al., 2003).

The goal of the present study was to determine the influence of speed of drinking on driving behaviors after alcohol in binge drinkers. Binge drinkers were administered the equivalent of four alcoholic beverages in 10 small drinks, paced ad libitum, within two hours. In frequent bingers, after four standard drinks in two hours, simulated driving speed increased while confidence in driving was unaffected relative to placebo (Bernosky-Smith et al., 2011). Similarly, we hypothesized that as speed of drinking increased, simulated driving speed would also increase, even if self-reported impairment and confidence in driving were unchanged.

METHODS

Participants

Forty moderate drinkers (20 male, 20 female) participated. Hazardous drinkers were excluded as determined by a score greater than 12 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Babor et al., 1983). The study protocol was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board and all participants gave informed consent. Subjects received $80 compensation for participation.

Procedure

During a screening visit, participants were administered the modified Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (First et al., 2001) and the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Psychological Corporation, 1999). All participants with a current Axis-I disorder or IQ < 80 were excluded. Positive urinalysis results for illicit drugs (Multi-drug 6 line screen; Innovacon, Inc, San Diego, CA) and/or pregnancy (QuickVue; Quidel, San Diego, CA) excluded the individual from participation.

Eligible participants returned to the laboratory for the second testing day. Upon arrival participants completed a baseline driving simulation then began alcohol administration. Participants were instructed to consume 10 small drinks (described as “the amount of four standard drinks”) sequentially at their desired pace, and were informed that the session would always last the full two hours. Participants alerted research staff by hand wave when they desired each new drink. Participants were not prohibited from monitoring the progress of time.

After the two hour alcohol administration period, participants completed visual analog scales. Twenty minutes later, they began the driving simulation, then returned to the drinking laboratory where breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) was measured every 20 minutes (Intoxilyzer SD-5; CMI Inc., Owensboro, KY). Participants who reached a BrAC below 0.03% and satisfactorily completed a field sobriety test were allowed to leave the laboratory with a previously appointed designated driver.

Alcohol Administration

In this paradigm, 0.8 g/kg 95% alcohol was mixed with lemonade to yield a 500 mL solution which was separated into ten 50 mL glasses. Alcohol concentrations were reduced by 8% for females to adjust for alcohol metabolism (Hindmarch et al., 1991).

Visual Analog Scales (VAS)

These consisted of a question (“I feel impaired” or “I am confident in operating a vehicle”) above a 100-mm horizontal line indicating a range of responses from “not at all” to “extremely”. Participants indicated the degree to which they agreed with each statement by drawing a vertical line to intersect the horizontal line. Scores were calculated as the distance in millimeters from the left of the line to the intersecting line drawn by the participant.

Simulated Driving (STISIM Drive™, Systems Technology, Inc., Hawthorne, CA). In this original task developed by our laboratory, subjects drove through a nine-mile course that alternated suburban driving (speed limit 35–45) and highway driving (speed limit 55). The course featured four stop lights, two stop signs, moderate-to-heavy automobile traffic, jaywalking pedestrians, and random “speeding tickets”. The latter were indicated by sirens and triggered if speed exceeded the posted limit by at least 9 mph. Participants were instructed to drive within posted speed limits. Individuals who completed the task in 16.5 minutes or less after alcohol administration earned a $20 bonus above the $80 compensation. Participants were penalized $2 from this bonus for each stop sign violation, speeding ticket, collision, or traffic light violation. Anyone with ten or more penalties received no bonus but did not lose additional money.

Data Analysis

Simulated driving variables at baseline and post-alcohol were compared with paired t tests. Speed of drinking was quantified as minutes to order all ten beverages. Pearson correlations quantified relationships between age, drinks per week, BrAC at start of testing, speed of drinking, mean driving speed, time spent speeding, collisions, and VAS. Sex differences in pre-study self-reported drinks per week, speed of drinking, mean driving speed, time spent speeding, and VAS were measured with t tests. Statistical significance was defined as α < 0.05.

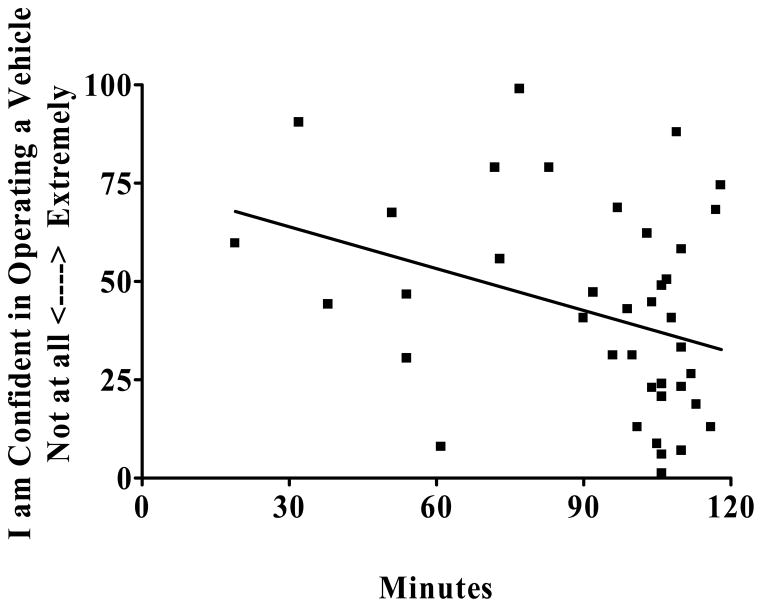

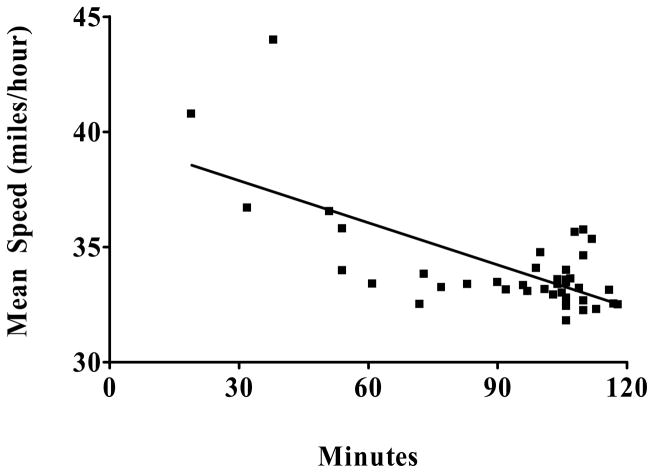

RESULTS

Simulated driving occurred within the descending limb of the breath alcohol curve. Mean (SD) BrAC was .07% (.02%) immediately following the two-hour drinking session and .06% (.02%) when driving began. Mean driving speed was faster after alcohol administration than at baseline (t = 3.4, df = 39; p < .05); the mean (SD) time to complete the course was 16.67 (.84) minutes before alcohol and 16.12 (.84) minutes after alcohol. Confidence in driving was positively correlated with BrAC at time of testing (p < .01; Table 1). Time to finish drinking was negatively correlated with confidence in driving after alcohol, as well as mean driving speed and time spent above the speed limit both before and after alcohol (p < 0.05; Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). Age, drinks per week, and BrAC at time of testing were unrelated to driving measures. No significant sex differences were found.

Table 1.

Age, drinking measures, driving performance, and self-report measures: Correlations and Descriptive Statistics (N=40)

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (yrs) | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Drinks/week | −.15 | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. BrAC @ testing | .17 | −.12 | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Time to finish drinking (mins) | −.05 | .12 | −.12 | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Mean driving speed (mph, baseline) | .10 | .30 | .28 | −.33* | -- | |||||||

| 6. Time above speed limit (sec, baseline) | .08 | .06 | .17 | −.49** | .74*** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Collisions (baseline) | −.11 | .06 | −.17 | −.19 | .04 | .30 | -- | |||||

| 8. Mean driving speed (mph, post-alcohol) | −.20 | .09 | −.03 | −.68*** | .45** | .52** | .30 | -- | ||||

| 9. Time above speed limit (sec, post-alcohol) | −.11 | .11 | −.07 | −.55*** | .47** | .62*** | .28 | .87*** | -- | |||

| 10. Collisions (post-alcohol) | .03 | −.16 | −.12 | −.40* | .17 | .22 | .09 | .60*** | .61** | -- | ||

| 11. Confidence in driving VAS | .02 | .05 | .44** | −.34* | .22 | .15 | −.03 | .16 | .13 | −.09 | -- | |

| 12. Impairment VAS | .06 | −.02 | −.06 | .25 | −.002 | −.16 | −.04 | −.23 | −.25 | .18 | −.59*** | -- |

|

| ||||||||||||

| M | 26 | 8 | .06% | 92 | 33 | 24 | 2 | 34 | 22 | 1 | 42 | 46 |

| SD | 3 | 6 | .02% | 25 | 2 | 67 | 1 | 2 | 31 | 1 | 27 | 24 |

| Range | 21–35 | 1–25 | .03–.10% | 19–118 | 29–40 | 0–429 | 0–5 | 32–44 | 0–154 | 0–6 | 1–99 | 4–95 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Figure 1.

Mean time in minutes to order all ten drinks was correlated (r = −0.34, p < 0.05) with reported confidence in operating a vehicle after alcohol administration for all subjects (n=40).

Figure 2.

Mean time in minutes to order all ten drinks was correlated (r = − 0.68, p < 0.0001) with mean driving speed on the simulator after alcohol for all subjects (n=40).

DISCUSSION

This study found a positive association between speed of alcohol consumption and self-reported confidence in driving an automobile. Speed of drinking was also positively associated with subsequent simulated driving speed and collisions. Alcohol intoxication encourages risk-taking behaviors, such as speeding while driving (Fillmore et al., 2008). The finding that faster drinking was associated with faster driving speeds is troubling, as heavy episodic drinking leads to impaired driving in an estimated 80% of cases (Quinlan et al., 2005). Speeding and alcohol use combined increase the risk of collisions. Post-crash analyses have reported that individuals who consumed alcohol drove at elevated speeds as compared to sober drivers (Stoduto et al., 1993; McGwin and Brown, 1999). Heavy episodic drinking is characterized by consumption of alcohol in a rapid manner. Therefore, the elevated crash risk due to driving at excessive speeds may be enhanced by the fast drinking of alcohol.

Binge drinkers are more likely than non-bingers to engage in a risk behavior such as speeding after alcohol use due to their tendency to underestimate impairment (Beirness, 1987). The observed relationship between speed of drinking and confidence in driving may have been a function of the BrAC curve. Those who drank most quickly would likely be on the descending limb of the BrAC curve at the time of driving. In this regard, binge drinkers have shown acute tolerance to the effects of alcohol on the descending limb (Marczinski and Fillmore, 2009). Existing evidence that binge drinkers are more likely to drive after drinking compared to non-bingers may be a direct result of acute tolerance to the subjective effects of alcohol as BrAC levels are falling. Individuals may also report greater confidence due to a greater latency between alcohol consumption and driving. They may approach driving in a less cautious manner by driving at elevated speeds due to their decreased perception of impairment, though alcohol effects persist for some time after initial ingestion.

With regard to traffic safety, binge drinkers should be encouraged to control the pace of their alcohol consumption, rather than consuming the bulk of their alcohol intake early in a binge episode. Our data are consistent with evidence that protective behavioral strategies such as pacing drinks to one or fewer per hour minimizes negative consequences of alcohol use (Martens et al., 2004; Ray et al., 2012). Though fast drinkers may no longer perceive themselves as intoxicated after two hours, alcohol impairment persists long after initial ingestion. Drinkers are likely to underestimate the time required for BrAC to reach its peak after drinking has concluded (Portans et al., 1989). This underestimation may indicate why individuals believe they are able to drive legally when their blood alcohol concentration is actually above the legal limit (Marczinski and Fillmore, 2009). Greater efforts are needed in alcohol education to make individuals aware that the dangers of alcohol persist after drinking has stopped.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge research funding from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grants P01 17056 and T32 07565.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None reported.

References

- Babor TF, Berglas S, Mendelson JH, Ellingboe J, Miller K. Alcohol, affect, and the disinhibition of verbal behavior. Psychopharmacology. 1983;80:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00427496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirness DJ. Self-estimates of blood alcohol concentration in drinking-driving context. Drug Alc Depen. 1987;19:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(87)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernosky-Smith KA, Shannon EE, Roth AJ, Liguori A. Alcohol effects on simulated driving in frequent and infrequent binge drinkers. Hum Psychopharm Clin. 2011;26:216–223. doi: 10.1002/hup.1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Blackburn JS, Harrison EL. Acute disinhibiting effects of alcohol as a factor in risky driving behavior. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2008;95:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User’s Guide for the SCID-I (Research Version) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S, Stafford LD, Attwood AS, Walker SC, Terry P. Cues that signal the alcohol content of a beverage and their effectiveness at altering drinking rates in young social drinkers. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2008;43:630–635. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarch I, Kerr JS, Sherwood N. The effects of alcohol and other drugs on psychomotor performance and cognitive function. Alcohol Alcoholism. 1991;26:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BM, Vega A. Fast and slow drinkers. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1973;34:797–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Heilig M, Cunningham CL, Stephens DN, Duka T, O’Malley SS. Ethanol consumption: how should we measure it? Achieving consilience between human and animal phenotypes. Addict Biol. 2010;15:109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Acute alcohol tolerance on subjective intoxication and simulated driving performance in binge drinkers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:238–247. doi: 10.1037/a0014633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, Cimini MD. Protective behavioral strategies when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences in college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGwin G, Jr, Brown DB. Characteristics of traffic crashes among young, middle-aged, and older drivers. Accident Anal Prev. 1999;31:181–198. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(98)00061-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz H, Burns M. Effects of rate of drinking on human performance. J Stud Alcohol. 1976;37:598–605. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1976.37.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA newsletter. 2004;3 [Google Scholar]

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic Safety Facts 2008. National Center for Statistics & Analysis; Washington D.C: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Portans I, White JM, Staiger PK. Acute tolerance to alcohol: changes in subjective effects among social drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 1989;97:365–369. doi: 10.1007/BF00439452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Corporation. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan KP, Brewer RD, Siegel P, Sleet DA, Mokdad AH, Shults RA, Flowers N. Alcohol-impaired driving among U.S. adults, 1993–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray AE, Stapleton JL, Turrisi R, Philion E. Patterns of drinking-related protective and risk behaviors in college student drinkers. Addict Behav. 2012;37:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoduto G, Vingilis E, Kapur BM, Sheu WJ, McLellan BA, Liban CB. Alcohol and drug use among motor vehicle collision victims admitted to a regional trauma unit: demographic, injury, and crash characteristics. Accident Anal Prev. 1993;25:411–420. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(93)90070-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]