Abstract

Protein palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of the 16-carbon fatty acid palmitate to a cysteine residue. It is the most common acylation of protein and occurs only in eukaryotes. Palmitoylation plays an important role in the regulation of protein subcellular localization, stability, translocation to lipid rafts and many other protein functions. Hence, the accurate prediction of palmitoylation site(s) can help in understanding the molecular mechanism of palmitoylation and also in designing various related experiments. Here we present a novel in silico predictor called ‘PalmPred’ to identify palmitoylation sites from protein sequence information using a support vector machine model. The best performance of PalmPred was obtained by incorporating sequence conservation features of peptide of window size 11 using a leave-one-out approach. It helped in achieving an accuracy of 91.98%, sensitivity of 79.23%, specificity of 94.30%, and Matthews Correlation Coefficient of 0.71. PalmPred outperformed existing palmitoylation site prediction methods – IFS-Palm and WAP-Palm on an independent dataset. Based on these measures it can be anticipated that PalmPred will be helpful in identifying candidate palmitoylation sites. All the source datasets, standalone and web-server are available at http://14.139.227.92/mkumar/palmpred/.

Introduction

S-Palmitoylation (hereafter termed as palmitoylation) is a eukaryote specific [1], reversible post-translational protein modification, which covalently adds palmitate moiety (C16∶0) to a cysteine residue through a thioester linkage [2], [3]. It plays an important role in a number of cellular processes such as membrane-protein interaction [4], signal transduction [5], neuronal development [6], apoptosis [7], lipid raft targeting [8], [9] and subcellular localization [10]. Thus accurate identification of palmitoylation sites may provide important clues to decipher the underlying mechanism in the above-mentioned processes. Experimental techniques employing proteomics and imaging methods can be used for detection of palmitoylation sites. However time and resources required to search palmitoylation sites in the huge number of protein sequences present in different databanks, limit their usage. Due to this reason, only a small number of palmitoylation sites have been identified experimentally to date. Therefore an effective and highly accurate in silico prediction method can be very useful in rapid identification of candidate palmitoylation site which can be targeted for further experimental verification.

In recent years a few computational methods have been reported to find out palmitoylation sites by using information carried in protein sequences. Zhou et al. [11] developed the first predictor CSS-Palm by adopting clustering and scoring strategy on the dataset containing 210 palmitoylation sites with Jack-Knife sensitivity of 82.16% and specificity of 83.17%. Another predictor NBA-Palm was created by Xue et al. [12] using Naive Bayes method which achieved the overall prediction accuracy of 86.74% in Jack-Knife cross-validation. Ren et al. [13] proposed version 2.0 of CSS-Palm and claimed significant improvement in performance over previous version. Wang et al. [14] added a new algorithm CKSAAP-Palm to this list which used composition of k-spaced amino acid pairs as the encoding scheme. Later Hu et al. [15] proposed another predictor, named IFS-Palm, based on the features of amino acid sequences using Nearest Neighbor Algorithm and successfully showed that the IFS-Palm achieved a significantly better performance over CKSAAP-Palm on an independent dataset. Recently one more predictor WAP-Palm [16] was reported having accuracy 85.99% and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.72 in 10 fold cross-validation.

Here we report a new support vector machine (SVM) based approach for palmitoylation site identification by using features extracted from the primary amino acid sequence information only. In order to build SVM model we extracted palmitoylated peptides of different window size and encoded the same with different input features namely sequence conservation (PSSM), secondary structure and disorder. The best result was achieved with the sequence conservation encoding on 11-mer peptide. Benchmarking results on independent datasets confirmed that the proposed method is more efficient than the recent predictors, IFS-Palm and WAP-Palm. A web-server and standalone package, termed PalmPred is also available at http://14.139.227.92/mkumar/palmpred/, to enable high throughput annotation of new palmitoylation sites.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

In this study, we used the dataset constructed for the development of IFS-Palm [15]. It is compiled from the Uniprot database [17] (Release: 15.9, 13-Oct-2009) by searching the keywords “Field” for ‘Sequence annotation [FT]’, “Topic” for ‘Lipidation’, “Term” for ‘Palmitoyl cysteine’, and “Confidence” for ‘Experimental’. The dataset consists of 151 proteins, which include 1537 cysteine residues in total, of which 234 residues were experimentally verified, as palmitoylation sites and remaining 1303 were not palmitoylated. The dataset was further divided into training and independent test datasets, similar to the strategy adopted in IFS-Palm.

Training dataset

Out of the total of 151 proteins, 132 proteins having 207 experimentally verified palmitoylated cysteines and 1140 non-palmitoylated cysteines were used as training dataset (Dtrain).

Independent test datasets

Remaining 19 proteins having 27 experimentally verified palmitoylated cysteines and 163 non-palmitoylated cysteines were used as an independent dataset (D1ind).

It was clear that proteins of D1ind were not present in training dataset of IFS-Palm and our method but for other predictors this may not be the case. In order to benchmark the performance of our method vis-à-vis other, we created another independent dataset (D2ind). For this, we used 54 yeast proteins in which palmitoylation sites were identified and described in [18]. Eight proteins, also present in training dataset Dtrain were excluded from the D2ind. The resulting D2ind dataset contains 46 proteins in which palmitoylation sites have been identified experimentally. This dataset was also used for independent evaluation of our method. To include any recent addition of palmitoylation sites, proteins of D2ind were also searched in Uniprot from Field “Sequence annotation (FT)”, Topic “Lipidation” and Term “S-palmitoyl cysteine”.

We also compiled two more datasets for assessing the performance of our method – D3ind and D4ind containing 10 and 17 proteins respectively in which several palmitoylation sites were experimentally confirmed. The dataset D3ind was collected from [19]. The dataset D4ind was taken from [20] and consists of synaptic, motor, channels, G-protein coupled receptor, focal adhesion and tight junction proteins. We did not find any Uniprot annotation for palmitoylation in D3ind and D4ind proteins.

Pattern Size for Feature Encoding

The first step of our work was to determine the optimal window length, W of the cysteine containing peptide which can give maximum performance for palmitoylation site prediction. In order to do this, we extracted peptide segments of different window sizes from each protein such that each W-mer peptide contained a cysteine, symmetrically flanked by (W-1)/2 residues. For terminal cysteine residue, where the flanking region had less than (W-1)/2 residues, appropriate number of dummy residue ‘X’ was added to complete the window.

Each peptide segment was assigned a label depending on the nature of central cysteine residue. The peptide segment having a palmitoylated central cysteine residue was labeled positive and a non-palmitoylated central cysteine residue was labeled as negative. Thus for each window we extracted a total of 207 and 27 positive labels from Dtrain and D1ind respectively. Similarly the number of negative labels in Dtrain and D1ind were 1140 and 163.

Feature Encoding

Conservation feature

This was obtained from position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) generated during PSI-BLAST [21] search against NR90 by three iterations of searching at e-value cut-off of 0.001 for inclusion of sequences in next iteration. The NR90 database was constructed from NR protein sequence database clustered at 90% sequence identity by using CD-HIT [22]–[24]. The PSSM contains the probability of occurrence of each type of amino acid residues at each position and hence can be considered as a measure of residue conservation at a given position. This means that evolutionary information for each amino acid is encapsulated in a vector of 20 dimensions and the size of PSSM for a protein with N residues is 20 x N. In the present work, since we were using a peptide of fixed length ‘W’ to encode a palmitoylation site, a corresponding sub-matrix of size W x 20 was extracted from each PSSM. In case of peptides containing ‘X’ (see previous section), each ‘X’ in PSSM was represented by ‘0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0′.

Structural disorder feature

Disordered regions are known to be rich in binding sites and provide an important locus for diverse protein post-translational modifications such as methylation and acetylation [25]. A number of studies also reported that the incorporation of structural disorder increases the prediction accuracy [26], [27]. Therefore, we also included structural disorder probability of each residue as an input feature to code the peptides. For this purpose, VSL2 predictor [28], [29] was used which assigned a score between 0 and 1 to each residue. Higher value of VSL2 score (close to 1) shows lack of fixed 3-dimensional structure while lower value shows higher propensity of fixed structure. It means larger the score is, the more likely a residue lacks fixed structure. We assigned score 0 to each dummy residue ‘X’.

Secondary structure feature

In their work Hu et al. [15] had reported that information of protein structure also plays an important role in the prediction of palmitoylation site. It indicates that if structural information of each amino acid can be provided into more explicit form, it may help to achieve better prediction of palmitoylation site. In the present study we provided probability of an amino acid to form each of the three secondary structures namely, helix, sheet and coil using standalone PSIPRED (Ver 3.3) [30] at default parameters. Here also NR90 was used to generate the PSSM. Similar to conservation feature, for secondary structure prediction each ‘X’ was given a hypothetical value of ′0 0 0′ to maintain uniformity with other amino acid scores.

Support Vector Machines

We employed Support Vector Machine classifiers (SVM) to predict if, for a given input feature vector, the central cysteine residue is palmitoylated or not. SVMs, designed by Vapnik [31], are computational algorithms, which can efficiently classify complex, non-linear and high-dimensional data. So, it has been used for developing a large number of bioinformatics applications [32]–[36]. SVM trains a classifier by mapping the input vectors in higher dimension space through kernel functions and separating them into two classes (represented as positive and negative labels) with the maximal margin and least error in the transformed space. The trained classifier can be used to predict in which of the two classes an unknown sample falls, with a high confidence level. In the current study, SVM model was built using SVM-light [37] which is freely available from http://svmlight.joachims.org/. We experimented with several values of cost-factor, kernel (polynomial and radial basis function kernels) and penalty parameter C on peptides of different window sizes taken from Dtrain. The model with the best performance parameters was selected as the optimal model.

Cross-Validation

Cross-validation is a method to evaluate classifier performance. The independent dataset test, sub-sampling (k-fold cross-validation) and Jack-Knife analysis (leave-one-out) are the three popular methods for cross-validation. In k-fold cross-validation, the dataset is randomly divided into k non-overlapping sets, k-1 sets are used for training and the remaining set for testing. This process is repeated k times such that each set is used as test set once and overall performance is calculated by averaging over all test sets.

In the present study we used ‘leave-one-out’ cross-validation (LOOCV) which has been considered as the most objective method in comparison to other two methods [38]–[43]. LOOCV uses one example from dataset as testing data and the remaining as training data. In a complete cycle of LOOCV, each example is used as test. The LOOCV thus shows dynamic behavior of testing and training data where every sample is the training set to train models as well as the testing set to test model [44]. It can also exclude the memory effects that exist in the re-substitution test, and provides the unique results for a given benchmark dataset [45].

Classifier Evaluation Measures

We adopted threshold-dependent performance matrices namely Specificity (Sp), Sensitivity (Sn), Accuracy (Acc), and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) to measure the prediction capability of our method. Sensitivity and specificity respectively are the percentage of correct predictions from positive (palmitoylated cysteines) and negative cases (non-palmitoylated cysteines). Accuracy (arithmetic mean of sensitivity and specificity) signifies the overall percentage of correctly predicted palmitoylated and non-palmitoylated peptides. The MCC [46] is a measure of predictive capability of classifiers, which reflects both the sensitivity, and specificity of the prediction algorithm. It is considered as a more reliable measure of the quality of binary classifications and can be used for unbalanced dataset also [47],[48]. The MCC value always ranges from -1 to 1. An efficient predictor will have positive correlation coefficient value. The value -1 and 0 represents opposite and random predictions respectively.

All of the above mentioned parameters can be defined as follows:

The abbreviations t+, t−, f+ and f− represent true positive, true negative, false positive and false negative respectively. True and false positives are the predicted palmitoylated peptides, which are in reality a palmitoylated, and non-palmitoylated peptide respectively. True and false negatives are the peptides predicted as non-palmitoylated and are actually a non-palmitoylated and palmitoylated peptides respectively.

Results and Discussion

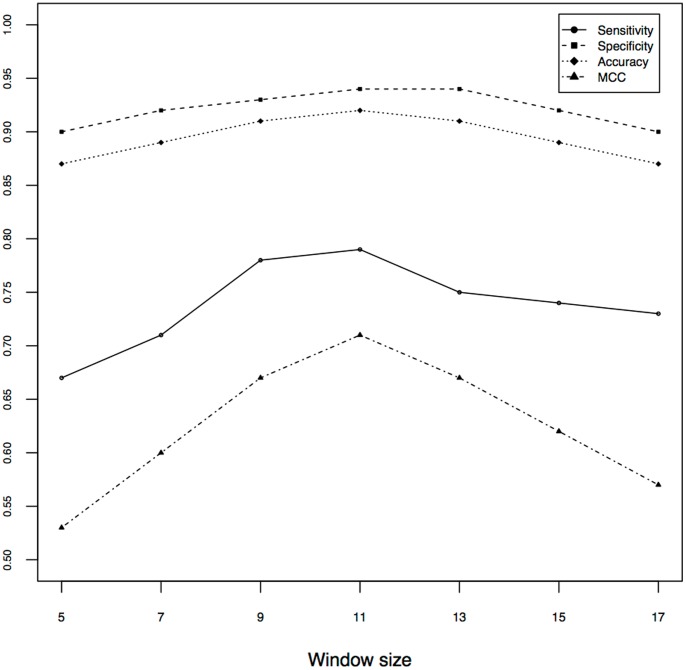

Performance of PSSM and Selection of Optimized Window

To get optimum pattern size, we used only the evolutionary information obtained from PSSM generated by PSI-BLAST search against NR90. The performance was analyzed for window sizes 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15 and 17. As shown in Figure 1, the overall performance increased steadily with increase in the window-size, attained the peak at 11 and started declining afterwards. The maximum performance, which was achieved by us for pattern size 11, was 79.23% sensitivity, 94.30% specificity and 91.98% accuracy with MCC 0.71 (detailed performance in Table 1). In rest of the work, window-size 11 and PSSM based model was considered as baseline model unless mentioned otherwise. Additional features were added to the baseline model to further improve the performance.

Figure 1. Performance of SVM on different window size.

Table 1. Performance of PSSM based SVM model.

| Threshold | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | MCC | False Positive Rate (%) (100-specificity) |

| −1 | 94.20 | 36.93 | 45.73 | 0.24 | 63.07 |

| −0.9 | 92.75 | 60.18 | 65.18 | 0.38 | 39.82 |

| −0.8 | 89.37 | 73.77 | 76.17 | 0.47 | 26.23 |

| −0.7 | 88.89 | 81.05 | 82.26 | 0.55 | 18.95 |

| −0.6 | 85.51 | 86.49 | 86.34 | 0.60 | 13.51 |

| −0.5 | 81.64 | 90.88 | 89.46 | 0.65 | 9.12 |

| −0.4 | 79.23 | 94.30 | 91.98 | 0.71 | 5.70 |

| −0.3 | 72.95 | 95.96 | 92.43 | 0.70 | 4.04 |

| −0.2 | 67.63 | 96.75 | 92.28 | 0.69 | 3.25 |

| −0.1 | 58.94 | 97.63 | 91.69 | 0.65 | 2.37 |

| 0 | 53.62 | 98.25 | 91.39 | 0.63 | 1.75 |

| 0.1 | 49.28 | 98.60 | 91.02 | 0.61 | 1.40 |

| 0.2 | 45.89 | 98.86 | 90.72 | 0.59 | 1.14 |

| 0.3 | 39.61 | 98.95 | 89.83 | 0.55 | 1.05 |

| 0.4 | 38.16 | 99.12 | 89.76 | 0.54 | 0.88 |

| 0.5 | 33.82 | 99.21 | 89.16 | 0.51 | 0.79 |

| 0.6 | 27.54 | 99.47 | 88.42 | 0.46 | 0.53 |

| 0.7 | 21.26 | 99.47 | 87.45 | 0.40 | 0.53 |

| 0.8 | 17.87 | 99.65 | 87.08 | 0.37 | 0.35 |

| 0.9 | 13.04 | 99.82 | 86.49 | 0.32 | 0.18 |

| 1 | 8.70 | 99.91 | 85.89 | 0.26 | 0.09 |

The selected performance for SVM model has been shown in bold.

Integration of Structure Disorder Information in Sequence Profile

When we integrated the disorder scores of central cysteine and its flanking 5 amino acids (on each side) derived from VSL2, no change in performance was noticed. We obtained sensitivity of 79.23%, specificity of 94.30%, accuracy of 91.98% and MCC of 0.71, which is exactly same as the performance achieved using PSSM alone (Table 1). It is opposite to what observed by Hu et al. [15] that disordered region plays an important role in the cysteine-palmitoylation. In their work, Gao and Xu [49] had observed a very little difference in the mean disorder scores (as predicted by VSL2) for both S-palmitoylated and non-palmitoylated cysteine. This little difference between the disorder propensities may be the reason for not getting any improvement in the prediction accuracy.

Prediction using Information in Sequence Conservation and Secondary Structure

Computing the probability score to form each of the three secondary structures by an amino acid is also a way of providing order/disorder information. Hence we also used PSIPRED predicted secondary structure information along with PSSM as input and trained the SVM. With PSSM and secondary structure information combined together, we achieved the accuracy of 91.98% and MCC of 0.71. The corresponding values of sensitivity and specificity were 79.23% and 94.30% respectively.

Again the result did not show any improvement over baseline model. This shows that addition of secondary structure information was also not able to provide any extra information to the predictor.

Prediction using Information in Sequence Profile, Secondary Structure and Disorder

We also used a combination of both disorder and secondary structure likelihood of each residue of the peptide pattern to see the influence of both together. Contrary to our expectation we obtained no increase in accuracy of prediction. All the performance measures i.e., sensitivity, specificity, accuracy and MCC remained same as obtained with PSSM alone (Table 1).

Hence SVM model obtained with PSSM was considered the final prediction model in rest of the work and it is referred as PalmPred henceforth.

Comparison with Existing Methods

Comparison of LOOCV performance

The existing methods of palmitoylation site prediction are CSS-Palm 1.0, NBA-Palm, CSS-Palm 2.0, CKSAAP-Palm, IFS-Palm and WAP-Palm. As the training data of the available predictors, except IFS-Palm, is different from the PalmPred, direct comparison among these predictors with PalmPred might not be reasonable. As described in materials and methods PalmPred and IFS-Palm has similar training dataset, so we compared the performance during LOOCV between them only. The PalmPred reached sensitivity of 79.23%, specificity of 94.30%, accuracy of 91.98% and MCC of 0.71 whereas the IFS-Palm attained sensitivity of 68.60%, specificity of 94.65%, accuracy of 90.65% and MCC of 0.64 (Table 2). The result shows that at comparable specificity, PalmPred achieved almost 10% higher sensitivity.

Table 2. Performance of IFS-Palm and PalmPred on training dataset (Dtrain) using LOOCV approach of training.

| Predictor | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | MCC |

| IFS-Palm | 68.60 | 94.65 | 90.65 | 0.64 |

| PalmPred | 79.23 | 94.30 | 91.98 | 0.71 |

Comparison of independent dataset performance

In order to do an unbiased evaluation, it is essential to benchmark the performance on an independent dataset. We used two independent datasets namely D1ind and D2ind for benchmarking purpose (see materials and methods for detail).

The first dataset (D1ind) had a subset of 19 proteins out of total 151 proteins compiled by Hu et al. [15] for development and evaluation of IFS-Palm. The performance of CKSAAP-Palm, IFS-Palm and PalmPred was evaluated on D1ind. As shown in Table 3, in comparison of CKSAAP-Palm, a significant difference was observed in the performance of PalmPred. When comparison was made between IFS-Palm and PalmPred, PalmPred achieved better sensitivity though the specificity was same (Table 3). The result was consistent to the performance shown during LOOCV, where also PalmPred had achieved higher sensitivity and comparable specificity. While we were working on development of PalmPred, a new palmitoylation site prediction method, namely, WAP-Palm was published by Shi et al. [16]. As 12 out of 15 proteins constituting the independent dataset of WAP-Palm were part of PalmPred training data, we did not benchmark the performance of WAP-Palm vis-à-vis PalmPred.

Table 3. Performance of CKSAAP-Palm, IFS-Palm and PalmPred on the independent dataset (D1ind) of 19 proteins.

| Predictors | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | MCC |

| CKSAAP-Palm* | 62.96 | 86.50 | 83.16 | 0.43 |

| IFS-Palm* | 92.59 | 98.77 | 97.89 | 0.91 |

| PalmPred | 96.30 | 98.77 | 98.42 | 0.94 |

*The values for all measurement categories had been taken from Hu et al. 2011.

The dataset D2ind was used for performance assessment of IFS-Palm, WAP-Palm and PalmPred. We took palmitoylation sites of D2ind proteins predicted by IFS-Palm from [15]. As Shi et al. [16] had shown that WAP-Palm performed best at threshold 0.8 we used the same threshold for prediction. We observed that PalmPred identified 61 palmitoylation sites in 33 proteins. WAP-Palm predicted 21 palmitoylation sites in 15 proteins while IFS-Palm predicted 60 sites in 31 proteins (Table 4). When we made a comparison between PalmPred and IFS-Palm, it was observed that PalmPred predicted at least one palmitoylated site in 10 different proteins where IFS-Palm failed to predict even one site. When we compared the 24 experimentally verified palmitoylation sites by Roth et al. [18], the total number of sites predicted by WAP-Palm, IFS-Palm and PalmPred were 1, 3 and 11 respectively. For protein TLG2, Roth et al. [18] had estimated the palmitoylation at position 317 [15] but PalmPred predicted it at 316 (Table 4). We cross-checked the position in sequence of TLG2 (available at Uniprot) and found that cysteine was present at position 316. When we analyzed the prediction of PalmPred vis-à-vis Uniprot annotation, we observed that PalmPred predicted 29 novel sites, failed to predict 4 sites and correctly predicted 32 sites.

Table 4. Comparative study of cysteine palmitoylation sites in Yeast proteins. This data is referred as D2ind in the text.

| Protein | Uniprot ID | Uniprot annotation | Experimentally identified sites | IFS-Palm | WAP-Palm | PalmPred |

| TVP18 | A6ZMD0 | – | – | – | – | 78 |

| HIP1 | P06775 | – | 603 | 339, 463 | 339 | – |

| RHO2 | P06781 | 188* | 188 | 188 | – | 188 |

| NUC1 | P08466 | – | – | – | – | – |

| TUB1 | P09733 | – | – | – | – | 14 |

| GPA2 | P10823 | 4 | – | 4 | – | 4 |

| GAP1 | P19145 | – | – | 286 | – | – |

| YCK1 | P23291 | 537#, 538# | – | 537, 538 | – | 537, 538 |

| YCP4 | P25349 | 243* | – | 243 | – | 243 |

| AGP1 | P25376 | 633# | – | 469 | 172, 266 | – |

| SYN8 | P31377 | 238* | 238 | – | – | 238 |

| MLF3 | P32047 | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| SSO1 | P32867 | – | 266 | – | – | 266 |

| SNC2 | P33328 | 94* | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| YKT6 | P36015 | 196# | – | 196 | – | 196 |

| YKL047W | P36090 | – | – | 516 | – | 516 |

| BAP2 | P38084 | – | 609 | – | – | – |

| VAP1 | P38085 | – | 619 | 318, 412 | – | – |

| YBR016W | P38216 | – | – | 110, 119, 122 | – | 119 |

| TAT2 | P38967 | – | – | 489 | – | – |

| AKR1 | P39010 | – | – | 663 | 533, 667 | 533, 663, 667 |

| MNN1 | P39106 | – | 17 | – | – | – |

| SSO2 | P39926 | – | 270, 274 | – | – | 270 |

| YCK3 | P39962 | 517*, 518*, 519*,520*, 522*, 523*,524* | – | 84, 517, 518,519, 522, 524 | – | 517, 518, 519,520, 522, 523 |

| VAC8 | P39968 | 4*, 5*, 7* | – | 4, 5, 7, 106, 144 | 106 | 4, 5, 7 |

| HEM14 | P40012 | – | – | 104, 435 | – | – |

| LBS6 | P42951 | – | – | 217, 223, 531 | – | 217, 223 |

| MNN11 | P46985 | – | 35 | – | – | – |

| MSE1 | P48525 | – | – | 413 | 502 | 12 |

| GNP1 | P48813 | – | 663 | 193, 312 | 201 | – |

| MNN10 | P50108 | – | 44 | 263, 362 | – | – |

| YGL108C | P53139 | 4* | – | 4 | – | 4 |

| RHO3 | Q00245 | – | 5 | – | 130 | 5 |

| MEH1 | Q02205 | 7 *, 8* | – | 7, 8 | – | 7, 8 |

| TLG1 | Q03322 | 205*, 206* | 205, 206 | – | – | 205 |

| YLR326W | Q06170 | – | – | 79, 80, 81 | 80 | 79, 80, 81 |

| SNA4 | Q07549 | 2*, 3*, 5*, 7*, 8* | – | – | – | 2, 3, 5, 7, 34 |

| PSR1 | Q07800 | 9$, 10$ | – | 10 | 10 | 9, 10 |

| YLR001C | Q07895 | – | 780 | 780 | 504 | 780 |

| PSR2 | Q07949 | 9$, 10$ | – | 9, 10 | 10 | 9, 10 |

| TLG2 | Q08144 | – | 317, 325 | – | – | 316 |

| YPL199C | Q08954 | – | – | 235 | – | 233, 235 |

| SAM3 | Q08986 | – | – | 268, 321 | 321 | – |

| YPL236C | Q12003 | 13*, 14*, 15* | – | 14, 15 | 13, 14, 159 | 13, 14, 15 |

| PIN2 | Q12057 | – | 35, 41, 53 | 66, 79, 81,82, 84 | 66, 81, 82 | 53, 66, 79,81, 82, 84 |

| VAM3 | Q12241 | – | 262, 274 | – | – | 262 |

, * and # denotes the palmitoylated cysteine respectively annotated as ‘probable’, ‘By similarity’ and ‘potential’ in Uniprot.

CSS-Palm 1.0, NBA-Palm and CSS-Palm 2.0 web-servers were not functional, so we could not compare these methods.

Database for PSSM Construction

One of the prerequisites to carry out the prediction in PalmPred is to first do the PSI-BLAST to generate input features i.e. PSSM. One major challenge in employing PSI-BLAST is that with increase in database size, PSI-BLAST search time also increases. Therefore, to speed up the PSSM generation, we used databases having less redundancy than NR90 and then evaluated the performance. For D1ind proteins, we generated PSSM against NR80 and NR70 and checked their performance on the PalmPred model. NR80 and NR70 contained 80% and 70% redundancy reduced protein sequences respectively and were compiled from NCBI-NR protein sequences by using CD-HIT [22]–[24]. As shown in Table S1, with decrease in redundancy of NR database, the performance also decreased which was as reported by Ahmad and Sarai [50].

Comparison with Other Machine Learning Classifiers

Other than SVM, several machine learning approaches have been used to develop classifiers for predicting post-translational modification sites including palmitoylation [12], [16], [51]. So besides SVM, we also tested following three machine learning methods implemented in WEKA program [52]: Naïve Bayes, RBF Network and Random forest. Similar to the SVM each of these three classifiers was constructed by incorporating PSSM score on pattern size 11. Each classifier was trained and evaluated on the training dataset (Dtrain) using LOOCV. By comparing the prediction results of the Naïve Bayes, RBF Network and Random forest classifiers with SVM classifier (Table 5), it was found that SVM classifier achieved the highest specificity, accuracy and MCC. The performance on independent dataset D1ind was also very poor for Naïve Bayes, RBF Network and Random forest classifiers (Table 5). The comparison clearly shows that the SVM is an ideal choice among different machine learning methods available.

Table 5. Performance of different machine learning classifiers.

| Leave-one-out Cross-validation | Independent Testing Dataset (D1ind) | |||||||

| Classifiers | Sn | Sp | Acc | MCC | Sn | Sp | Acc | MCC |

| Naïve Bayes | 79.60 | 74.50 | 79.58 | 0.44 | 82.80 | 81.70 | 82.63 | 0.51 |

| RBF Network | 85.00 | 49.00 | 85.00 | 0.37 | 82.10 | 60.00 | 82.11 | 0.37 |

| Random Forest | 85.20 | 21.40 | 85.23 | 0.19 | 89.50 | 36.50 | 89.47 | 0.48 |

| Support Vector Machine | 79.23 | 94.30 | 91.98 | 0.71 | 96.30 | 98.77 | 98.42 | 0.94 |

Sn, Sp, Acc and MCC represent Sensitivity, Specificity, Accuracy and Matthews Correlation Coefficient respectively.

Web-Server

To make the optimized SVM model accessible to experimental biologists, we have developed PalmPred web-server and standalone package. The prediction output provides information about all cysteine containing peptides, the position and palmitoylation state of cysteines. The PalmPred web-server can take a maximum of 5 sequences at a time. For a query dataset of more than 5 sequences standalone version of PalmPred can be used. The PalmPred is freely available at http://14.139.227.92/mkumar/palmpred/.

Performance Assessment of PalmPred

Recently two reports were published which experimentally established palmitoylation sites in a group of proteins. The first work was done by Nishimura and Linder [19] which experimentally identified palmitoylation sites in Rho GTPase proteins. The second work was reported by Oku et al. [20] on 17 candidate proteins predominantly expressed in brain. In order to further assess the reliability of PalmPred, we used the proteins of above-mentioned work (referred as D3ind and D4ind respectively in materials and methods).

Nishimura and Linder [19] reported a novel motif, CCaX, which tandomly undergoes prenylation and palmitoylation at C-terminal. In order to prove their hypothesis they worked on a set of ten proteins. They experimentally determined palmitoylation sites for five proteins and also reported a protein, PLA2γ, which is known to be palmitoylated but the site of palmitoylation present in this protein is unknown. When PalmPred was used to predict the palmitoylation site in these ten proteins, of five proteins whose palmitoylation sites were experimentally determined PalmPred could correctly determined palmitoylation sites of two of those proteins (Table 6). For PLA2γ, PalmPred predicted the candidate palmitoylation site as amino acid 539 which is consistent with the observations of [19] i.e. the predicted position lies at second C of CCaX motif. Of the remaining four proteins (PRL-1, PRL-2, PDE6α and PDE6β), whose palmitoylation sites was not determined by Nishimura and Linder, in PRL-1, PalmPred correctly predicted palmitoylation site at 171, which follows the hypothesis proposed by [19] besides one additional site at position 104 (Table 6). But in PRL-2, PalmPred predicted site did not follow the CCaX motif rule. In PDE6α and PDE6β, PalmPred did not predict any palmitoylation site which might be actually the case, as canonical CaaX processing (i.e. proteolysis and carboxymethylation after prenylation of CaaX cysteine) of PDE6α and PDE6β is well documented [53].

Table 6. Prediction performance of PalmPred on dataset D3ind taken from Nishimura and Linder 2013 (referred as D3ind).

| Protein | Uniprot ID | Total no. of cysteines in protein | Experimentally identified sites | PalmPred |

| bcdC42 | P60953 | 7 | 188 | – |

| Wrch-1 | Q7L0Q8 | 12 | 256 | 256 |

| RalA | P11233 | 3 | 203 | – |

| RalB | P11234 | 2 | 203 | – |

| PRL-1 | Q93096 | 6 | – | 104, 171 |

| PRL-2 | Q12974 | 7 | – | 101 |

| PRL-3 | O75365 | 6 | 170 | 171 |

| PDE6α | P16499 | 15 | – | – |

| PDE6β | P23440 | 21 | – | – |

| PLA2γ | Q9UP65 | 7 | – | 539 |

Out of the 17 proteins tested as candidate for palmitoylation, Oku et al. [20] were able to experimentally establish the palmitoylation only for 10 sites (Table 7). PalmPred was able to correctly predict 5 sites out of them. One additional site (at position Cys-3) was also confirmed by the mutational analysis in neurochondrin which was also correctly predicted by PalmPred. Among the seven proteins whose palmitoylation couldn’t be established by [20], in four proteins namely Homer 1C, Liprin-α2, Paxillin and Par3, PalmPred did not predict any palmitoylation site (Table 7). In remaining three proteins viz Kalirin7, KIF5C candidate site and palmitoylation sites were different while in one protein (Rab3A) both candidate and PalmPred predicted sites were same but no palmitoylation can be experimentally established.

Table 7. Prediction of PalmPred on dataset D4ind taken from Oku et al. 2013.

| Protein | Uniprot ID | Total no. ofcysteines in protein | PutativePalmitoylation sites | Experimentalconfirmation | PalmPred |

| TARPγ-2 | O88602 | 6 | 121 | + | 68, 121 |

| TARPγ-8 | Q8VHW2 | 7 | 144 | + | 90, 91, 144 |

| Cornichon-2 | O35089 | 8 | 9 | + | 84 |

| CaMKIIα | P11798 | 10 | 6 | + | – |

| Kalirin7 | A2CG49 | 55 | 1404 | – | 417, 989, 1334, 2508 |

| Homer1C | Q9Z2Y3 | 2 | 365 | – | – |

| Neurochondrin | Q9Z0E0 | 25 | 3,4 | + | 3, 4, 292, 647, 348 |

| Rab3A | P63011 | 4 | 220 | – | 218, 220 |

| Syd-1 | Q9DBZ9 | 13 | 736 | + | 346, 360 |

| Liprin-α2 | Q8BSS9 | 9 | 3 | – | – |

| KIF5C | P28738 | 10 | 7 | – | 303, 304 |

| TRPM8 | Q8R4D5 | 26 | 1032 | + | 780, 1028, 1031, 1032, 1033 |

| TRPC1 | Q61056 | 19 | 736 | + | 198, 367, 692, 703 |

| Orexin2receptor | P58308 | 14 | 381 | + | 381, 382 |

| Paxillin | Q8VI36 | 25 | 591 | – | – |

| Zyxin | Q62523 | 23 | 404 | + | – |

| Par3 | Q99NH2 | 12 | 6 | – | – |

One important thing we noticed with both datasets (D3ind and D4ind) that despite very large number of cysteines in few proteins, PalmPred predicted palmitoylation site did not increased proportionally. Rather it shows robustness and high specificity of prediction of our method. One of the possible reasons behind slightly inferior performance of PalmPred can be due to novelty of datasets on which work of [19] and [20] is based as both tried to establish palmitoylation in a new group of proteins. Even Uniprot does not have any information of palmitoylation of these proteins. We feel that with addition of new information to the database, the performance can also be improved further.

Conclusions

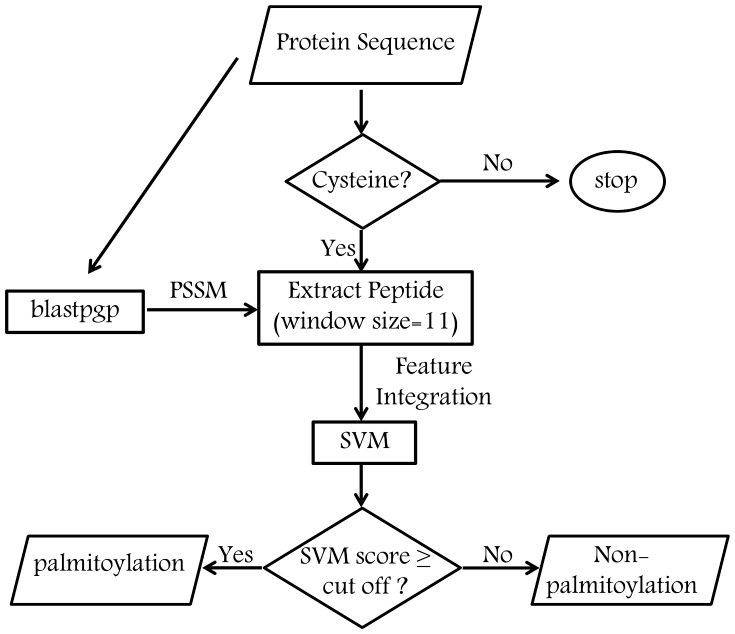

In the present study we have described a novel machine learning tool called PalmPred to identify protein palmitoylation sites by using sequence conservation features. LOOCV and benchmarking results showed that PalmPred performed better than the other existing methods. Thus we hope PalmPred may serve as a useful tool to find potential palmitoylation sites in a protein. One downside of our approach is that it takes comparatively more time to generate evolutionary profile however we tried to resolve this issue up to a certain extent by evaluating the performance of PalmPred on less redundant data. The web-interface and standalone of PalmPred is available at http://14.139.227.92/mkumar/palmpred/. The overall working schema for PalmPred is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The basic architecture of PalmPred.

Supporting Information

Performance assessment of SVM model based on different databases.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

Bandana Kumari is supported by a University Grant Commission non-NET fellowship (Non-Net/139/2012) and Ravindra Kumar by a Senior Research fellowship (20-12/2009(ii)EU-IV) from the University Grant Commission of India. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Salaun C, Greaves J, Chamberlain LH (2010) The intracellular dynamic of protein palmitoylation. J Cell Biol 191: 1229–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bijlmakers MJ, Marsh M (2003) The on-off story of protein palmitoylation. Trends Cell Biol 13: 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dietrich LE, Ungermann C (2004) On the mechanism of protein palmitoylation. EMBO Rep 5: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Linder ME, Deschenes RJ (2003) New insights into the mechanisms of protein palmitoylation. Biochemistry 42: 4311–4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Resh MD (2006) Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE 2006: re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huang K, El-Husseini A (2005) Modulation of neuronal protein trafficking and function by palmitoylation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang DA, Sebti SM (2005) Palmitoylated cysteine 192 is required for RhoB tumor-suppressive and apoptotic activities. J Biol Chem 280: 19243–19249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wong W, Schlichter LC (2004) Differential recruitment of Kv1.4 and Kv4.2 to lipid rafts by PSD-95. J Biol Chem 279: 444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salaun C, Gould GW, Chamberlain LH (2005) The SNARE proteins SNAP-25 and SNAP-23 display different affinities for lipid rafts in PC12 cells. Regulation by distinct cysteine-rich domains. J Biol Chem 280: 1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Van Itallie CM, Gambling TM, Carson JL, Anderson JM (2005) Palmitoylation of claudins is required for efficient tight-junction localization. J Cell Sci 118: 1427–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhou F, Xue Y, Yao X, Xu Y (2006) CSS-Palm: palmitoylation site prediction with a clustering and scoring strategy (CSS). Bioinformatics 22: 894–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xue Y, Chen H, Jin C, Sun Z, Yao X (2006) NBA-Palm: prediction of palmitoylation site implemented in Naive Bayes algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ren J, Wen L, Gao X, Jin C, Xue Y, et al. (2008) CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng Des Sel 21: 639–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang XB, Wu LY, Wang YC, Deng NY (2009) Prediction of palmitoylation sites using the composition of k-spaced amino acid pairs. Protein Eng Des Sel 22: 707–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu LL, Wan SB, Niu S, Shi XH, Li HP, et al. (2011) Prediction and analysis of protein palmitoylation sites. Biochimie 93: 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi SP, Sun XY, Qiu JD, Suo SB, Chen X, et al. (2013) The prediction of palmitoylation site locations using a multiple feature extraction method. J Mol Graph Model 40: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boeckmann B, Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Blatter MC, Estreicher A, et al. (2003) The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roth AF, Wan J, Bailey AO, Sun B, Kuchar JA, et al. (2006) Global analysis of protein palmitoylation in yeast. Cell 125: 1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimura A, Linder ME (2013) Identification of a novel prenyl and palmitoyl modification at the CaaX motif of Cdc42 that regulates RhoGDI binding. Mol Cell Biol 33: 1417–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oku S, Takahashi N, Fukata Y, Fukata M (2013) In silico screening for palmitoyl substrates reveals a role for DHHC1/3/10 (zDHHC1/3/11)-mediated neurochondrin palmitoylation in its targeting to Rab5-positive endosomes. J Biol Chem 288: 19816–19829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li W, Jaroszewski L, Godzik A (2001) Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 17: 282–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li W, Jaroszewski L, Godzik A (2002) Tolerating some redundancy significantly speeds up clustering of large protein databases. Bioinformatics 18: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li W, Godzik A (2006) Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 22: 1658–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russell RB, Gibson TJ (2008) A careful disorderliness in the proteome: sites for interaction and targets for future therapies. FEBS Lett 582: 1271–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O’Connor TR, Sikes JG, et al. (2004) The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 1037–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lobley A, Swindells MB, Orengo CA, Jones DT (2007) Inferring function using patterns of native disorder in proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 3: e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Dunker AK (2005) Exploiting heterogeneous sequence properties improves prediction of protein disorder. Proteins 61 Suppl 7176–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peng K, Radivojac P, Vucetic S, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z (2006) Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. BMC Bioinformatics 7: 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones DT (1999) Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J Mol Biol 292: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vapnik V (1995) The Nature of Statical Learning Theory. Springer Verlag, New York.

- 32. Hua S, Sun Z (2001) A novel method of protein secondary structure prediction with high segment overlap measure: support vector machine approach. J Mol Biol 308: 397–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim JH, Lee J, Oh B, Kimm K, Koh I (2004) Prediction of phosphorylation sites using SVMs. Bioinformatics 20: 3179–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kumar M, Verma R, Raghava GP (2006) Prediction of mitochondrial proteins using support vector machine and hidden Markov model. J Biol Chem 281: 5357–5363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kumar M, Gromiha MM, Raghava GP (2007) Identification of DNA-binding proteins using support vector machines and evolutionary profiles. BMC Bioinformatics 8: 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kumar M, Gromiha MM, Raghava GP (2008) Prediction of RNA binding sites in a protein using SVM and PSSM profile. Proteins 71: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joachims T (1999) Making large-Scale SVM Learning Practical. Advances in Kernel Methods – Support Vector Learning, B. Scholkopf and C. Burges and A. Smola (ed.), MIT-Press.

- 38. Chou KC, Zhang CT (1995) Prediction of protein structural classes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 30: 275–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chou KC, Cai YD (2004) Predicting protein structural class by functional domain composition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321: 1007–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chou KC (2011) Some remarks on protein attribute prediction and pseudo amino acid composition. J Theor Biol 273: 236–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gao Y, Shao S, Xiao X, Ding Y, Huang Y, et al. (2005) Using pseudo amino acid composition to predict protein subcellular location: approached with Lyapunov index, Bessel function, and Chebyshev filter. Amino Acids 28: 373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhou GP, Assa-Munt N (2001) Some insights into protein structural class prediction. Proteins 44: 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhou GP, Doctor K (2003) Subcellular location prediction of apoptosis proteins. Proteins 50: 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cai YD, Chou KC (2006) Predicting membrane protein type by functional domain composition and pseudo-amino acid composition. J Theor Biol 238: 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chou KC, Shen HB (2007) Recent progress in protein subcellular location prediction. Anal Biochem 370: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Matthews BW (1975) Comparison of the predicted and observed secondary structure of T4 phage lysozyme. Biochim Biophys Acta 405: 442–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xie J, Xu Z, Zhou S, Pan X, Cai S, et al. (2013) The VHSE-Based Prediction of Proteosomal Cleavage Sites. PLoS One 8: e74506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu Y, Ding J, Wu LY, Chou KC (2013) iSNO-PseAAC: predict cysteine S-nitrosylation sites in proteins by incorporating position specific amino acid propensity into pseudo amino acid composition. PLoS One 8: e55844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gao J, Xu D (2011) Correlation between Posttranslational modification and intrinsic disorder in protein. Biocomputing 2012: 94–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahmad S, Sarai A (2005) PSSM-based prediction of DNA binding sites in proteins. BMC Bioinformatics 6: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jiang Y, Li B-Q, Zhang Y, Feng Y-M, Gao Y-F, et al. (2013) Prediction and Analysis of Post-Translational Pyruvoyl Residue Modification Sites from Internal Serines in Proteins. PLoS One 8: e66678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witten IH, Frank E (2005) Data mining: practical machine learning tools and techniques. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Anant JS, Ong OC, Xie HY, Clarke S, O’Brien PJ, et al. (1992) In vivo differential prenylation of retinal cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase catalytic subunits. J Biol Chem 267: 687–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Performance assessment of SVM model based on different databases.

(DOC)