Abstract

The mechanisms by which maternal nutrient restriction (MNR) causes reduced fetal growth are poorly understood. We hypothesized that MNR inhibits placental mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and insulin/IGF-I signaling, down-regulates placental nutrient transporters, and decreases fetal amino acid levels. Pregnant baboons were fed control (ad libitum, n=11) or an MNR diet (70% of controls, n=11) from gestational day (GD) 30. Placenta and umbilical blood were collected at GD 165. Western blot was used to determine the phosphorylation of proteins in the mTOR, insulin/IGF-I, ERK1/2, and GSK-3 signaling pathways in placental homogenates and expression of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), taurine transporter (TAUT), sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter (SNAT), and large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT) isoforms in syncytiotrophoblast microvillous membranes (MVMs). MNR reduced fetal weights by 13%, lowered fetal plasma concentrations of essential amino acids, and decreased the phosphorylation of placental S6K, S6 ribosomal protein, 4E-BP1, IRS-1, Akt, ERK-1/2, and GSK-3. MVM protein expression of GLUT-1, TAUT, SNAT-2 and LAT-1/2 was reduced in MNR. This is the first study in primates exploring placental responses to maternal undernutrition. Inhibition of placental mTOR and insulin/IGF-I signaling resulting in down-regulation of placental nutrient transporters may link maternal undernutrition to restricted fetal growth.—Kavitha, J. V., Rosario, F. J., Nijland, M. J., McDonald, T. J., Wu, G., Kanai, Y., Powell, T. L., Nathanielsz, P. W., Jansson, T. Down-regulation of placental mTOR, insulin/IGF-I signaling, and nutrient transporters in response to maternal nutrient restriction in the baboon.

Keywords: fetal growth restriction, trophoblast, nonhuman primate

Maternal undernutrition during pregnancy remains a serious problem worldwide and constitutes a significant problem also in the United States, because more than 50 million Americans live in households experiencing food insecurity or hunger at least some time during the year (1). Maternal undernutrition is the most common cause of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in developing countries. IUGR is associated with perinatal morbidity and mortality (2) and increases the risk for diabetes and cardiovascular disease in adult life (3–5). However, the mechanisms linking maternal nutrient restriction to reduced fetal growth and programming of adult disease remain to be fully established.

Previous studies in experimental animals have implicated changes in placental growth, structure, and function as critical mediators of adverse pregnancy outcomes in response to altered maternal nutrient availability (6–11). In human IUGR due to placental insufficiency, the activity of the placental system A and system L amino acid transporters is decreased (12–15), consistent with the possibility that changes in the activity of placental nutrient transporters may directly contribute to abnormal fetal growth (16–18). System A is a sodium-dependent transporter mediating the uptake of nonessential neutral amino acids into the cell (19). All three known isoforms of system A, sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter (SNAT)-1 (SLC38A1), SNAT-2 (SLC38A2), and SNAT-4 (SLC38A4) are expressed in the placenta (20). System A activity establishes the high intracellular concentration of amino acids like glycine, which is used to exchange for extracellular essential amino acids via system L. Thus, system A activity is critical for placental transport of both nonessential and essential amino acids. System L is a sodium-independent amino acid exchanger mediating cellular uptake of essential amino acids, including leucine (21). The system L amino acid transporter is a heterodimer, consisting of a light chain, typically large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT)-1 (SLC7A5) or LAT-2 (SLC7A8), and a heavy chain, 4F2hc/CD98 (SLC3A2).

Maternal hormones, such as insulin and IGF-I, as well as trophoblast mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling, are important regulators of placental amino acid transport (22–28). Calorie restriction in humans and animals typically decreases circulating levels of IGF-I and insulin, (29, 30), and maternal serum concentrations of insulin and IGF-I are reduced in pregnant rats fed a low-protein diet (8). mTOR is a serine/threonine kinase and represents an important nutrient-sensing pathway in mammalian cells, which controls cell growth, proliferation, and metabolism in response to nutrient availability and growth factor signaling. mTOR exists in two complexes, mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2. The downstream effects of mTORC1 are mediated by phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) and p70 S6 kinase (S6K). mTORC2 phosphorylates Akt, PKCα, and serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) and influences the actin skeleton. Placental mTOR activity is decreased in human IUGR (26, 31) as well as in animal models of IUGR, such as low-protein diet in rats (11). In addition, maternal protein restriction in rats inhibits placental insulin/IGF-I signaling (11).

The effects of maternal nutrient restriction on the placenta have been studied experimentally in sheep (32–35) and rodents (6, 8, 11, 36–38). However, findings in the rodent and sheep placentas may not be representative of the human. Studies exploring the effect of nutrition on pregnancy outcome in pregnant women are difficult to perform due to poor sensitivity of methods assessing dietary intake, poor compliance, high biological variability, and inability to administer strict dietary regimens. Studies in pregnant nonhuman primates, with reproductive physiology that in many respects is more similar to human than laboratory rodent species and sheep, can be used to fill this gap of knowledge. However, no data are available on the effect of maternal nutrient restriction on placental signaling and transport functions in nonhuman primates. Here we studied the effect of maternal nutrient restriction on placental signaling and nutrient transporter expression in pregnant baboons, a nonhuman primate with a placental structure and development very similar to that of humans (39). We utilized a well-established model of global maternal nutrient restriction (MNR; animals given 70% of the control diet) associated with moderate IUGR and low maternal circulating levels of IGF-I. This degree of maternal, and subsequent fetal, nutrient restriction results in IUGR accompanied by major changes in the fetal brain frontal cortex (40), liver (41), and kidney (42). Fetal cortisol is also elevated (41), and offspring show an altered postnatal phenotype with decreased peripheral glucose disposal and elevated fasting glucose (43) and behavior (44). We hypothesized that MNR in baboons inhibits placental mTOR and insulin/IGF-I signaling, down-regulates placental nutrient transporters, and decreases fetal circulating levels of amino acids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets

All procedures were approved by the Texas Biomedical Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in facilities approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Baboons (Papio species) were housed in outdoor metal and concrete gang cages, each containing 10–16 females and 1 male. Details of housing and environmental enrichment have been described elsewhere (45).

System for controlling and recording individual feeding

The feeding system used has been described in detail (45). Briefly, once a day prior to feeding, all baboons were placed in individual feeding cages. Baboons passed along a chute, over a scale, and into an individual feeding cage. The weight of each baboon was obtained as it crossed an electronic scale system (GSE 665; GSE Scale Systems, Livonia, MI, USA). The weight recorded was the mean of 50 individual measurements over 3 s. If the sd of the weight measurement was >1% of the mean weight, the weight was automatically discarded, and the weighing procedure was repeated.

Once housed in an individual cage, each animal was fed between either 07:00 and 09:00 or 11:00 and 13:00. Water was available continuously in the individual feeding cage and the group cages. Animals were fed Purina Monkey Diet 5038 (Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA), described by the vendor as “a complete life-cycle diet for all Old World Primates.” The biscuit contains stabilized vitamin C as well as all other required vitamins. Its basic composition is crude protein ≥15%, crude fat ≥5%, crude fiber ≤6%, ash ≤5%, and added minerals ≤3%. At the start of the feeding period, each baboon was given 60 biscuits in the feeding tray of the individual cage. At the end of the 2 h feeding period, the baboons were returned to the group cage. Biscuits remaining in the tray, on the floor of the cage, and in the pan beneath the cage were counted. Food consumption of animals, weights, and health status were recorded each day.

Study design

Fertile female baboons were selected to participate in this study on the basis of their reproductive age (8–15 yr old), body weight (10–15 kg), and absence of genital and extragenital pathological signs. Initially, animals were placed into two group cages with a vasectomized male to establish a stable social group. Assignment to each group was random. At the end of the acclimation period to the group and to feeding in the individual nutritional cages (30 d), a fertile male was introduced into each breeding cage. All baboons were observed twice daily for well-being and 3 times/wk for turgescence (swelling), color of sex skin, and signs of vaginal bleeding to enable timing of ovulation and subsequent conception.

Pregnancy was dated initially by timing of ovulation and changes in sex skin color and confirmed at gestational day (GD) 30 by ultrasonography when the experimental feeding period was started. Ad libitum-fed control baboons were given 60 biscuits in their individual cage. Biscuits remaining were counted after baboons returned to their group cage. Animals subjected to MNR were fed 70% of the total food intake of contemporaneous controls on a per-kilogram basis.

Collection of tissue and blood samples

Cesarean sections were performed under isoflurane anesthesia at GD 165 (term 184). Briefly, animals were tranquilized with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg), intubated, and anesthetized using isoflurane (starting rate 2% with oxygen: 2.0 L/min). Conventional cesarean sections using standard sterile technique were performed as described previously (45). At cesarean section, fetuses and placentas were towel dried and weighed. Postoperative analgesia was provided using buprenorphine (0.015 mg/kg/d as 2 doses) for 3 d (45).

Trophoblast villous tissue was obtained from 8 different locations according to a standardized protocol, and either immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C or fixed in formalin (10% buffered formalin) and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemistry. Maternal blood was collected from the femoral vein at cesarean section, and fetal blood was obtained by umbilical venous blood sampling (45). Plasma was prepared and frozen at −80°C until analysis.

Amino acid analysis

Plasma samples (0.1 ml) were deproteinized with 0.1 ml of 1.5 M HClO4 and neutralized with 0.05 ml of 2 M K2CO3. The solution was centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 1 min, and the supernatant was used for analysis. Amino acids were determined by HPLC methods involving precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde, as described previously (46). All amino acids were quantified on the basis of authentic standards (Sigma Chemicals, St. Louis, MO, USA) using Millenium-32 Software (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Maternal and fetal plasma samples were available from all 11 control animals but only for 6 of the 11 MNR animals from which placental tissue was collected. To increase statistical power, plasma samples from 11 additional control animals were analyzed, resulting in n = 22 in this group.

Isolation of trophoblast plasma microvillous membranes (MVMs)

Approximately 0.5–1 g frozen trophoblast tissue was thawed on ice and homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Bohemia, NY, USA) in 1.5–3 ml of buffer D (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM HEPES-Tris, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, at 4°C) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Syncytiotrophoblast plasma MVMs were prepared as described previously (47, 48), with the exception that the preparation was scaled down to fit the small amount of starting tissue (11). Briefly, after initial centrifugation steps, MVMs were separated by Mg2+ precipitation and further purified with differential centrifugation. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. MVM purity was determined as the enrichment of alkaline phosphatase activity compared to homogenates (49, 50) and was assessed using standard activity assays for alkaline phosphatase. MVM enrichment of alkaline phosphatase activity in the control (4.9±0.4-fold, n=8) and MNR groups (5.0±0.5-fold, n=8) was not significantly different. As an additional enrichment marker, the expression of the insulin receptor, previously shown to be highly expressed in the MVM of human placenta (51), was determined using Western blot. MVM enrichment of the insulin receptor in the control (9.4±1.0 fold, n=8) and MNR groups (9.1±0.9 fold, n=8) was not significantly different (Supplemental Fig. S1). Protein content of the vesicles was determined by the method of Bradford.

Western blot analysis

Protein expression of total and phosphorylated mTOR (S-2448), S6K (Thr-389), 4E-BP1 (Thr-37/46 or Thr-70), S6 ribosomal protein (Ser-235/236), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3; Ser-21/9), AMPKα (Thr-172), extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ (ERK1/2; Thr-202/Tyr-204), Akt (Thr-308), raptor (Ser-792), tuberin/TSC-2 (Ser-1387) and LKB-1 (Ser-248) was determined in placental homogenates using commercial antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA). Antibodies recognizing insulin receptor β were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The anti-β-actin and IRS-1 (Tyr-612) antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Protein expression of the system A amino acid transporter isoforms SNAT-1, SNAT-2, and SNAT-4 and the system L amino acid transporter isoforms LAT-1, LAT-2, glucose transporter (GLUT)-1, and taurine transporter (TAUT), was analyzed in MVMs. The justification for determining protein expression of transporters in MVMs rather than in homogenates is that trophoblast nutrient transporters mediate cellular uptake and transfer across the placental barrier only if localized in the syncytiotrophoblast plasma membranes. Thus, data on amino acid transporter and GLUT-1 protein expression in MVMs is more informative than determination of protein expression in placental homogenates. The SNAT-1 antibody was received as a generous gift from Dr. Jean Jiang (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA). A polyclonal SNAT-2 antibody generated in rabbits (52), was generously provided by Dr. Puttur Prasad (University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA). Affinity-purified polyclonal anti-SNAT-4 antibodies were produced in rabbits using the epitope YGEVEDELLHAYSKV in human SNAT-4 (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). Antibodies targeting LAT-1 and LAT-2 were produced in rabbits as described previously (53). GLUT-1 and TAUT antibodies were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (11). In brief, 20 μg of total protein was loaded onto a NuPAGE Novex (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) precast 4–12% Bis–Tris gels and electrophoresis was performed at a constant 200 V for 40 min. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes at a constant 40 V. After transfer, membranes were blocked in 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (w/v) plus 0.1% Tween 20 (v/v) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with the appropriate peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies for 1 h. After washing, bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). Blots were stripped using β-mercaptoethanol and reprobed for β-actin as a loading control. Analysis of the blots was performed by densitometry using an αImager (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, CA, USA). For each protein target, the mean density of the control sample bands was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Subsequently, all individual control and MNR density values were expressed relative to this mean.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections (5 μm) of formalin-fixed trophoblast tissue were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in descending grades of alcohol (100, 70, and 45%) to water, immersed in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0), and heated to boiling for 10–15 min for antigen retrieval. After cooling for 15 min, the sections were rinsed in PBS, washed for 10 min in a solution of 1.5% H2O2 and methanol and then for 5 min in PBS. Sections were placed in diluted (10%) normal serum for 20 min and then incubated in primary antibody overnight at 4°C using a humidified chamber. Subsequently, sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with goat anti-rabbit biotinylated secondary antibody. Antigens were localized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in PBS for 1–5 min. Finally, tissues were stained with hematoxylin and mounted. Negative controls consisted of parallel incubations of sections after preabsorbation of the primary antibody using antigen peptide (where available) or after replacement of the primary antibody with normal horse serum.

Data presentation and statistics

The number of male and female fetuses was similar in the control (6 males/5 females) and MNR (5 males/6 females) groups. Because of the limited number of observations in each of the 4 groups, data were not analyzed for males and females separately. Data are presented as means ± sem or + sem. If not stated otherwise, 11 control and 11 MNR animals were studied. Statistical significance of differences between control and MNR diet groups was assessed using Student's t test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant. With the number of statistical tests performed in this study, it is expected that ∼4 of the statistically significant differences (P<0.05) identified have occurred only by chance, i.e., represent false positives (type I error). However, with the following justification, we elected not to adjust for multiple tests. Many outcome variables in our study are highly correlated, and adjusting for multiple testing is therefore not critical (54). Because we identified 24 differences that were statistically significant, it is clear that the overwhelming majority of these are, in fact, true differences. Many of the identified statistically significant differences were highly significant. Thus, adjustment for multiple testing, taking the highly correlated outcome variables into account, would have small effects. In this article, we do not discuss individual outcome variables but rather groups of outcome variables changing in the same direction.

RESULTS

Fetal and placental weights

At GD 165, fetal weights in the MNR group were reduced by 13% (control, 812.6±36.8; MNR, 706.5±26.0 g, n=11/group, P=0.03). Placental weights (control, 207.2±14.2; MNR, 171.3±11.9 g, P=0.06) were comparable between the groups. Furthermore, fetal/placental weight ratio (4.0±0.16 vs. 4.2±0.25, P=0.4) did not differ between the groups.

Maternal and fetal plasma amino acid concentrations

Maternal plasma concentrations of aspartic acid (−55%, P=0.02), glutamic acid (−30%, P=0.05), tyrosine (−38%, P=0.001), tryptophan (−36%, P=0.01), phenylalanine (−52%, P=0.002), leucine (−31%, P=0.01) and ornithine (−76%, P=0.001) were significantly decreased in the MNR animals compared to control. In contrast, maternal plasma concentrations of glycine (20%, P=0.04) were increased in the MNR group (n=6, Table 1) compared to control (n=22, Table 1). Fetal plasma concentrations of taurine (−32%, P=0.006), tyrosine (−34%, P=0.001), phenylalanine (−36%, P=0.003), leucine (−32%, P=0.01) and ornithine (−49%, P=0.005) were lower in MNR animals (n=6, Table 2) compared to control (n=22, Table 2).

Table 1.

Maternal plasma amino acid concentrations in control and MNR animals

| Amino acid | Control | MNR | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartic acid | 16 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 0.02 |

| Glutamic acid | 81.6 ± 6.2 | 57.1 ± 9.4 | 0.05 |

| Asparagine | 24.1 ± 1.4 | 27.1 ± 2.8 | 0.36 |

| Serine | 68.9 ± 2.8 | 79.9 ± 8.5 | 0.16 |

| Glutamine | 353.3 ± 17.6 | 345.6 ± 34.2 | 0.81 |

| Histidine | 81.8 ± 3.9 | 83.1 ± 8.5 | 0.92 |

| Glycine | 230.8 ± 9.4 | 276.4 ± 20.1 | 0.04 |

| Threonine | 80.3 ± 3.7 | 68.5 ± 2.1 | 0.13 |

| Citrulline | 13.3 ± 0.9 | 13.2 ± 2.0 | 0.98 |

| Arginine | 34.4 ± 1.9 | 41.4 ± 3.4 | 0.09 |

| β-Alanine | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 0.34 |

| Taurine | 151.5 ± 10.3 | 122.3 ± 8.3 | 0.19 |

| Alanine | 177.8 ± 13.3 | 212.6 ± 19.7 | 0.12 |

| Tyrosine | 36.8 ± 1.9 | 22.7 ± 2.1 | 0.001 |

| Tryptophan | 28.3 ± 2.0 | 18.0 ± 1.8 | 0.01 |

| Methionine | 22.3 ± 1.1 | 18.7 ± 1.6 | 0.10 |

| Valine | 89.6 ± 3.9 | 89.6 ± 5.6 | 0.92 |

| Phenylalanine | 70.5 ± 5.6 | 33.8 ± 1.9 | 0.002 |

| Isoleucine | 52.3 ± 3.5 | 40.3 ± 4.6 | 0.08 |

| Leucine | 78.3 ± 4.8 | 54.2 ± 7.3 | 0.01 |

| Ornithine | 26.8 ± 3.2 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 0.001 |

| Lysine | 140.6 ± 8.0 | 149.9 ± 11.3 | 0.46 |

Amino acid concentrations (μM) were measured at GD 165. Values are given as means ± sem; n = 22 (control) and 6 (MNR).

P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

Table 2.

Fetal plasma amino acid concentrations in control and MNR animals

| Amino acid | Control | MNR | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspartic acid | 10.1 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 0.08 |

| Glutamic acid | 81.7 ± 21.6 | 38.9 ± 5.9 | 0.22 |

| Asparagine | 55.9 ± 4.5 | 45.2 ± 4.0 | 0.18 |

| Serine | 147.0 ± 7.1 | 147 ± 9.8 | 0.90 |

| Glutamine | 766.8 ± 40.6 | 663.6 ± 32.1 | 0.19 |

| Histidine | 144.0 ± 6.5 | 139.0 ± 10.1 | 0.76 |

| Glycine | 394.0 ± 19.5 | 442.0 ± 24.7 | 0.20 |

| Threonine | 139.0 ± 8.5 | 125.0 ± 13.8 | 0.39 |

| Citrulline | 26.8 ± 1.8 | 32.2 ± 4.0 | 0.23 |

| Arginine | 93.0 ± 5.3 | 111.0 ± 13.0 | 0.20 |

| β-Alanine | 8.0 ± 1.8 | 7.0 ± 1.1 | 0.78 |

| Taurine | 206.3 ± 12.1 | 140.6 ± 17.5 | 0.006 |

| Alanine | 360.5 ± 32.2 | 403.5 ± 42.5 | 0.32 |

| Tyrosine | 63.0 ± 4 | 42.0 ± 2.3 | 0.001 |

| Tryptophan | 46.8 ± 1.6 | 45.9 ± 2.0 | 0.88 |

| Methionine | 45.1 ± 1.8 | 38.4 ± 2.4 | 0.06 |

| Valine | 169.0 ± 8.0 | 162.0 ± 10.4 | 0.71 |

| Phenylalanine | 98.6 ± 6.1 | 63.2 ± 3.5 | 0.003 |

| Isoleucine | 77.7 ± 5.4 | 63.2 ± 2.8 | 0.16 |

| Leucine | 108.0 ± 8.6 | 73.6 ± 2.2 | 0.01 |

| Ornithine | 54.8 ± 5.9 | 27.7 ± 3.0 | 0.005 |

| Lysine | 369.3 ± 23.2 | 394.5 ± 23.3 | 0.45 |

Amino acid concentrations (μM) were measured at GD 165. Values are given as means ± sem; n = 22 (control) and 6 (MNR), unpaired Student's t test.

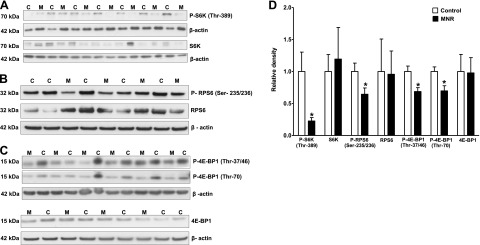

Inhibition of placental mTORC1 signaling in response to MNR

We determined the total expression and phosphorylation of S6K1 and 4E-BP1 in placental homogenates as functional readouts for mTORC1 activity. Phosphorylation of S6K1 (−78%, P=0.03) and ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6; −36%, P=0.04) was decreased in MNR placentas compared with control (Fig. 1A, B, D). However, total and phosphorylated mTOR (Ser-2448) was not significantly different in control and MNR groups (Supplemental Fig. S2A, B). Total expression of S6K1 and S6 ribosomal protein was unaffected by MNR (Fig. 1A, B, D).

Figure 1.

Phosphorylation of placental S6 kinase, RPS6, and 4E-BP1 in control and MNR animals. A–C) Representative Western blots for P-S6K (Thr-389; A) and S6K P-RPS6 (Ser-235/236; B) and RPS6 P-4E-BP1 (Thr-37/46 or Thr-70; C) and 4E-BP1 in homogenates of control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placentas at GD 165. D) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem. *P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

Figure 1C shows representative Western blots using antibodies directed against 4E-BP1 phosphorylated at Thr-37/46 or at Thr-70. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 is hierarchical, in that phosphorylation of Thr-37/46 is required for further phosphorylation at Thr-70. Both phosphorylation at Thr-37/46 (−31%, P=0.007) and at Thr-70 (−30%, P=0.01) was decreased in MNR placentas compared to control (Fig. 1C, D). In contrast, total placental 4E-BP1 expression was comparable between control and MNR groups (Fig. 1C, D).

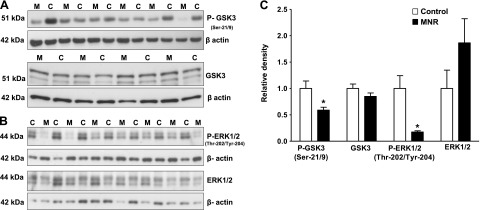

Inhibition of placental GSK-3 signaling in response to MNR

GSK-3 is regulated by insulin/IGF-I signaling via Akt and phosphorylates glycogen synthase. In the MNR placenta, phosphorylation of GSK-3 at Ser-21/9 was decreased by 42% (P=0.01) compared to control (Fig. 2A, C). However, total GSK-3 expression was comparable between the control and MNR groups (Fig. 2A, C).

Figure 2.

Placental GSK-3 and ERK1/2 signaling in control and MNR animals. A, B) Representative Western blots for P-GSK-3 (Ser-21/9) and GSK-3 (A) and P-ERK1/2 (Thr-202/Tyr-204) and ERK1/2 (B) in homogenates of control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placenta at GD 165. C) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem. *P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

Inhibition of placental ERK1/2 signaling in response to MNR

ERK1/2 is the activated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in mammals, and activation of ERK1/2 predominantly occurs through mitogenic stimuli, such as growth factors and hormones. In the MNR placenta, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 at (Thr-202/Tyr-204) was decreased by 83% (P=0.005) as compared to control (Fig. 2B, C). In contrast, total ERK1/2 expression was similar in control and MNR groups (Fig. 2A, B).

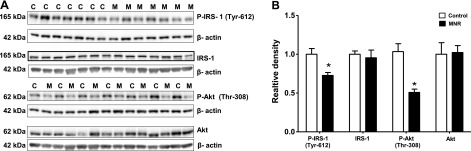

Inhibition of placental insulin/IGF-I signaling in response to MNR

Placental insulin/IGF-I signaling activity was assessed by determining phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Tyr-612 and Akt at Thr-308. In the MNR placenta, phosphorylation of IRS-1 at Tyr-612 (−68%, P=0.006) and Akt at Thr-308 (−57%, P=0.0005) was decreased compared to control Fig. 3A, B). However, total IRS-1 and Akt expression was similar in control and MNR groups (Fig. 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Placental insulin and IGF-I signaling in control and MNR animals. A) Representative Western blots for P-IRS-1 (Tyr-612), IRS-1, P-Akt (Thr-308), and P-Akt in homogenates of control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placenta at GD 165. B) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem. *P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

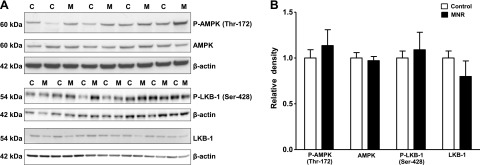

MNR does not alter placental AMPK, LKB, raptor, and tuberin/TSC2 phosphorylation

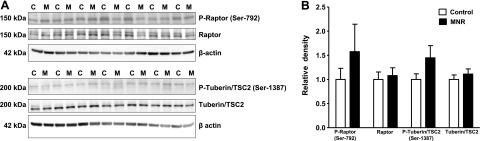

To test the hypothesis that MNR activates the placental AMPK/LKB/raptor/tuberin-TSC2 signaling pathway, total expression and phosphorylation of AMPK (Thr-172), LKB (Ser-428), raptor (Ser-792), and tuberin-TSC2 (Ser-1387) was assessed by Western blot. AMPK, LKB, raptor, or tuberin-TSC2 phosphorylation was not significantly different in control and MNR groups. Similarly, total AMPK, LKB, raptor, and tuberin-TSC2 expression was unaltered by MNR (Figs. 4 and 5A, B).

Figure 4.

Phosphorylation of placental AMPK and LKB-1 in control and MNR animals. A) Representative Western blots for P-AMPK (Thr-172), AMPK, P-LKB-1 (Ser-428), and LKB in homogenates of control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placenta at GD 165. B) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem; unpaired Student's t test.

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of placental raptor and tuberin/TSC2 in control and MNR animals. A) Representative Western blots for P-raptor (Ser-792), raptor, P-tuberin/TSC2 (Ser-1387), and tuberin/TSC2 in homogenates of control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placenta at GD 165. B) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem; unpaired Student's t test.

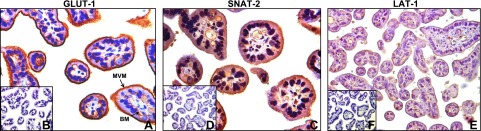

Cellular localization of nutrient transporters in the baboon placenta

Using immunohistochemistry, we demonstrate that GLUT-1 is expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast MVM and, to a lesser extent, plasma basal membrane (BM) of baboon placentas from control animals (Fig. 6A). In addition, SNAT-2 (Fig. 6C) and LAT-1 (Fig. 6E) are predominantly expressed in MVMs. No significant staining could be detected in negative control sections (Fig. 6B, D, F).

Figure 6.

Subcellular localization of nutrient transporter isoforms in baboon placenta. Subcellular localization of GLUT-1 (A), SNAT-2 (C), and LAT-1 (E) in placentas of control-fed baboons at 165 d gestation, with corresponding negative controls (B, D, F, respectively).

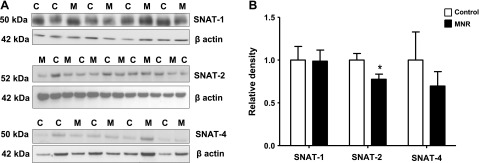

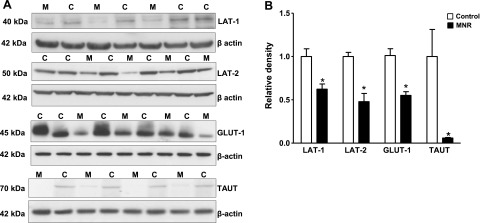

Down-regulation of placental nutrient transporter expression in response to MNR

Protein expression of system A transporter isoforms SNAT-1, SNAT-2, and SNAT-4 were detected in isolated placental MVMs at ∼50–52 kDa. Protein expression of SNAT-2 in MVMs was reduced (−22%, P=0.03) in MNR placentas compared to control (Fig. 7A, B); however, no changes could be observed in SNAT-1 and SNAT-4 expression levels (Fig. 7A, B). Feeding baboons a MNR diet significantly reduced the expression of the system L transporter isoforms LAT-1 (−28%, P=0.002) and LAT-2 (−53%, P=0.0002) in placental MVMs (Fig. 8A, B). Furthermore, protein expression of GLUT-1 and TAUT in MVMs was decreased (GLUT-1, −46%, P=0.0001, n=8/group; TAUT, −90%, n=8/group; P=0.02) in MNR placentas compared to control (Fig. 8A, B).

Figure 7.

Protein expression of system A amino acid transporter isoforms in MVMs. A) Representative Western blots for SNAT-1, SNAT-2, and SNAT-4 in MVM isolated from control (C) and MNR (M) placenta at GD 165. B) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem. *P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

Figure 8.

Protein expression of system L amino acid transporter isoforms GLUT-1 and TAUT in MVMs. A) Representative Western blots for LAT-1, LAT-2, GLUT-1, and TAUT in MVMs isolated from control (C) and MNR (M) baboon placenta at GD 165. B) Histogram summarizes the Western blotting data. Equal loading was performed. After normalization to β-actin, the mean density of C samples was assigned an arbitrary value of 1. Values are given as means + sem. *P < 0.05 vs. control; unpaired Student's t test.

DISCUSSION

The effect of maternal undernutrition on placental function has not been studied in pregnant women, and results from previous studies in rodents cannot directly be extrapolated to humans. This is the first study exploring changes in placental signaling and nutrient transporter expression in response to maternal nutrient restriction in a nonhuman primate. We report that maternal nutrient restriction during pregnancy (GD 30 to GD 165) in baboons is associated with an inhibition of insulin/IGF-I and mTOR signaling pathways, decreased expression of key amino acid and glucose transporter isoforms in the placenta, and lower fetal levels of essential amino acids. Because placental insulin/IGF-I and mTOR signaling pathways are known to be positive regulators of placental amino acid transporters, we speculate that the observed changes contribute to the decreased fetal circulating levels of amino acids and reduced fetal growth.

MNR decreased maternal plasma concentrations of aspartate, glutamate, tyrosine, tryptophan, leucine, and phenylalanine at GD 165. The mTOR signaling pathway is especially sensitive to changes in the concentrations of essential amino acids, in particular leucine (55–57). It is, therefore, possible that lower maternal leucine concentrations could contribute to mTOR inhibition in MNR placentas. MNR decreased the fetal plasma levels of the essential amino acids tyrosine, taurine, leucine, and phenylalanine, which may be a result of lower maternal amino acid levels and down-regulation of key placental amino acid transporters.

Phosphorylation is the most significant post-translational modification that reversibly regulates protein function and ultimately cell function. In the current study, we used immunoblotting targeting specific phosphoproteins, which is a powerful approach to assess steady-state protein phosphorylation in tissue. However, protein phosphorylation is a dynamic process regulated by the activity of upstream kinases and phosphatases, and it is recognized that Western blotting in a tissue sample does not provide detailed information on dynamics of protein phosphorylation. Placental signaling pathways linking maternal nutrition and metabolism to changes in nutrient transport may include mTOR, which is regulated by a wide range of factors, including amino acids, glucose, oxygen and energy status, and insulin/IGF-I, leptin, and TNF-α signaling (58). We show that phosphorylation of S6K1, RPS6, and 4E-BP1, representing well-established functional readouts of the mTORC1 signaling pathways, was decreased in placental homogenates of MNR placentas compared to control, consistent with an inhibition of placental mTOR signaling in MNR. In contrast, phosphorylation of mTOR at Ser-2448 was not altered in MNR. The functional significance of mTOR phosphorylation remains to be fully established, and whether mTOR phosphorylation is a positive, negative, or nonconsequential modification is controversial (55, 58). Furthermore, it has been reported that it is S6K1, rather than kinases upstream of mTOR that phosphorylates mTOR at Thr-2446 and Ser-2448 (59, 60). The unchanged phosphorylation at Ser-2448-mTOR despite inhibited S6K1 activity in MNR may be due to other kinases targeting this particular residue.

Placental mTOR signaling is a positive regulator of system A and L activity in cultured primary human trophoblast cells (11, 26, 61, 62). We recently demonstrated that mTOR regulates system A and L amino acid transport activity by modulating cell surface abundance of SNAT-2 and LAT-1 isoforms in cultured primary human trophoblast cells (61), providing one possible mechanism underlying the decrease in MVM system A and L isoform expression in MNR. AMPK is a well-established inhibitor of mTOR signaling. However, AMPK activation is unlikely to explain the observed inhibition in placental mTOR in association with MNR because phosphorylation of both LKB, an upstream regulator of AMPK, and AMPK was not significantly altered in MNR. Further, we report that phospho-raptor (Ser-722/792) and phospho-tuberin TSC2 (Ser-1387) (63), which are targets directly phosphorylated by AMPK, were unaltered in MNR. ERK1/2 has been reported to be a positive regulator of mTOR signaling by inactivation of TSC2 (64) and to directly phosphorylate 4E-BP1 (65). We suggest that the inhibition of the ERK1/2 and insulin/IGF-I signaling pathways that we observed in MNR placentas contribute to decreased mTOR activity and down-regulation of placental nutrient transporters.

We have reported that serum concentrations of IGF-I in pregnant MNR baboons are significantly decreased at GD 90 compared to controls (66). IGF-I (25, 67) and insulin (23, 24) stimulate the activity of trophoblast amino acid transporters (22), in part mediated by mTOR signaling (61). Nutrient restriction in humans and animal models decreases circulating levels of IGF-I and insulin (8, 29, 30). In addition, receptors for most of these hormones are highly expressed on the maternal-facing plasma membrane of the trophoblast cell (51, 68–70). Collectively, these data are consistent with the possibility that the down-regulation of placental amino acid transporters is caused by decreased maternal levels of growth factors such as IGF-I and insulin. In agreement with this hypothesis, we observed a decreased phosphorylation of GSK-3, an insulin/IGF-I target, in MNR placentas. Insulin promotes phosphorylation of GSK-3 at two serine residues, causing inhibition of the enzyme. Consequently, decreased phosphorylation at these sites activates GSK-3, which stimulates glycogen breakdown.

The similarity in subcellular localization of nutrient transporters for glucose and amino acids between the human (20, 71) and baboon placentas suggest that the mechanisms for nutrient delivery to the fetus are similar in the two species. SNAT-2 expression in MVMs, but not that of SNAT-1 or SNAT-4, was down-regulated in MNR. These findings are in agreement with other studies of SNAT isoform regulation in the placenta, suggesting that SNAT-2 is a highly regulated isoform (11, 28). In addition, system L amino acid transporter isoforms LAT-1 and LAT-2 expression in placental MVMs was reduced in MNR. GLUT-1 protein was found to be highly expressed in baboon MVMs, in agreement with the human placenta (71). Interestingly, MVM GLUT-1 protein expression was significantly decreased in MNR. ERK1/2 plays a central role in up-regulating GLUT-1 expression, thereby augmenting glucose transport (72, 73). We suggest that the inhibition of the ERK1/2 signaling pathways observed in MNR placentas contributes to down-regulation of MVM GLUT1 transporter expression. Although we did not measure fetal glucose concentrations in this study, these changes could contribute to decreased placental glucose transport in MNR. We observed a marked decrease in MVM TAUT expression in MNR placentas, and we propose that these changes contribute to the lower plasma taurine levels in the MNR fetus.

Fetal growth is intimately linked to placental nutrient transport. A significant body of evidence demonstrates that the activity of key placental amino acid transporters is decreased in human IUGR due to placental insufficiency (12–15), and both placental amino acid and glucose transporters have been reported to be up-regulated in fetal overgrowth (48, 74, 75). Furthermore, Malandro et al. (6) demonstrated that maternal protein malnutrition in rats results in down-regulation of placental amino acid transporters and IUGR in late gestation. In a more detailed analysis using the same experimental model, we demonstrated that placental amino acid transporters were down-regulated several days before IUGR could be observed, without any sign of compensatory up-regulation earlier in gestation (8, 11). Collectively, these reports and the current study show that the expression of placental nutrient transporters is positively correlated with fetal growth, compatible with the possibility that changes in placental nutrient transport directly contribute to the altered fetal growth. To explain the down-regulation of placental nutrient transport in response to maternal undernutrition and decreased uteroplacental blood flow, we have proposed a model (17) that the placenta responds to maternal nutritional cues, resulting in down-regulation of placental nutrient transporters in response to maternal undernutrition or restricted uteroplacental blood flow. In some cases, these signals dominate over fetal demand signals, fetal nutrient availability becomes limited, and fetal growth decreases. We have proposed that this mechanism matches fetal growth to the ability of the maternal supply line to allocate resources to the fetus. In this model, changes in placental growth and nutrient transport directly contribute to, or cause, alterations in fetal growth. We have proposed that these mechanisms have evolved due to the evolutionary pressures of maternal undernutrition. Matching fetal growth to maternal resources in response to maternal undernutrition will produce an offspring that is smaller in size but which, in most instances, will survive and be able to reproduce (76).

In this study we used a well-established nonhuman primate model in which pregnant baboons are fed 70% of the control diet on a per-kilogram basis to achieve global MNR. These studies are not possible to perform in humans because pregnant women cannot be subjected to experimental MNR. The striking similarities in reproductive physiology and placental structure and the close evolutionary relationship between nonhuman primates and humans contribute to the relevance of these studies. Maternal undernutrition is, together with infections, the most common cause of IUGR in developing countries. In addition, maternal undernutrition is a serious public health problem not only in the developing world, because more than 50 million Americans live in households experiencing food insecurity or hunger at least some time during the year (1). Thus, our nonhuman primate model, involving a 30% maternal calorie reduction throughout most of pregnancy, is highly relevant for human health and disease. Babies who were in utero during the wartime famine in the winter of 1944–1945 in Holland (the Dutch famine cohort) were moderately growth restricted and showed increased incidence of obesity and metabolic and cardiovascular disease in adulthood (77), demonstrating that maternal nutrition during gestation has important effects on health in later life in humans. Although most cases of IUGR in Western societies are related to impaired placental function (e.g., reduced placental blood flow, leading to “placental insufficiency”) rather than maternal undernutrition, the effects of these two distinct perturbations on placental signaling and function are strikingly similar (8, 11, 18, 26). Studies exploring the mechanisms underlying changes in placental function in response to maternal nutrient restriction may, therefore, be relevant also for placental insufficiency. In summary, we propose that inhibition of placental insulin/IGF-I, ERK1/2, and mTOR signaling and down-regulation of the expression of key placental nutrient transporters contribute to decreased fetal nutrient availability and reduced fetal growth in response to MNR in nonhuman primates (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant P01HD21350.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- 4E-BP1

- 4E-eukaryotic initiation factor binding protein 1

- ERK1/2

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- GD

- gestational day

- GLUT

- glucose transporter

- GSK-3

- glycogen synthase kinase 3

- IUGR

- intrauterine growth restriction

- LAT

- large neutral amino acid transporter

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1/2

- mTOR complex 1/2

- MNR

- maternal nutrient restriction

- MVM

- microvillous membrane

- RPS6

- ribosomal protein S6

- SGK1

- serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1

- S6K

- p70 S6 kinase

- SNAT

- sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter

- TAUT

- taurine transporter

REFERENCES

- 1. Nord M., Coleman-Jensen A., Andrews M., Carlson S. (2010) Household food security in the United States, 2009. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Services [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brodsky D., Christou H. (2004) Current concepts in intrauterine growth restriction. J. Intensive Care Med. 19, 307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gluckman P. D., Hanson M. A., Cooper C., Thornburg K. L. (2008) Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 61–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hales C. N., Barker D. J., Clark P. M., Cox L. J., Fall C., Osmond C., Winter P. D. (1991) Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ 303, 1019–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Barker D. J., Gluckman P. D., Godfrey K. M., Harding J. E., Owens J. A., Robinson J. S. (1993) Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 341, 938–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malandro M. S., Beveridge M. J., Kihlberg M. S., Novak D. A. (1996) Effect of low-protein diet-induced intrauterine growth retardation on rat placental amino acid transport. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C295–C303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Constancia M., Hemberger M., Hughes J., Dean W., Ferguson-Smith A. C., Fundele R., Stewart F., Kelsley G., Fowden A., Sibley C., Reik W. (2002) Placental-specific IGF-II is a major modulator of placental and fetal growth. Nature 417, 945–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jansson N., Pettersson J., Haafiz A., Ericsson A., Palmberg I., Tranberg M., Ganapathy V., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2006) Down-regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction in rats fed a low protein diet. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 576, 935–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu M. J., Du M., Hess B. W., Nathanielsz P. W., Ford S. P. (2007) Periconceptional nutrient restriction in the ewe alters MAPK/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt growth signaling pathways and vascularity in the placentome. Placenta 28, 1192–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhu M. J., Ma Y., Long N. M., Du M., Ford S. P. (2010) Maternal obesity markedly increases placental fatty acid transporter expression and fetal blood triglycerides at midgestation in the ewe. Am. J. Physiol. 299, R1224–R1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rosario F. J., Jansson N., Kanai Y., Prasad P. D., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2011) Maternal protein restriction in the rat inhibits placental insulin, mTOR, and STAT3 signaling and down-regulates placental amino acid transporters. Endocrinology 152, 1119–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mahendran D., Donnai P., Glazier J. D., D'Souza S. W., Boyd R. D. H., Sibley C. P. (1993) Amino acid (system A) transporter activity in microvillous membrane vesicles from the placentas of appropriate and small for gestational age babies. Pediatr. Res. 34, 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jansson T., Scholtbach V., Powell T. L. (1998) Placental transport of leucine and lysine is reduced in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr. Res. 44, 532–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Norberg S., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (1998) Intrauterine growth restriction is associated with a reduced activity of placental taurine transporters. Pediatr. Res. 44, 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glazier J. D., Cetin I., Perugino G., Ronzoni S., Grey A. M., Mahendran D., Marconi A. M., Pardi G., Sibley C. P. (1997) Association between the activity of the system A amino acid transporter in the microvillous plasma membrane of the human placenta and severity of fetal compromise in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr. Res. 42, 514–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2007) Role of the placenta in fetal programming: underlying mechanisms and potential interventional appraoches. Clin. Sci. 113, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2006) Human placental transport in altered fetal growth: does the placenta function as a nutrient sensor?—a review. Placenta 27(Suppl.), 91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sibley C. P., Turner M. A., Cetin I., Ayuk P., Boyd C. A. R., Souza S. W., Glazier J. D., Greenwood S. L., Jansson T., Powell T. (2005) Placental phenotypes of intrauterine growth. Pediatr. Res. 58, 827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mackenzie B., Erickson J. D. (2004) Sodium-coupled neutral amino acid (system N/A) transporters of the SLC38 gene family. Pflügers Arch. 447, 784–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Desforges M., Lacey H. A., Glazier J. D., Greenwood S. L., Mynett K. J., Speake P. F., Sibley C. P. (2006) The SNAT4 isoform of the system A amino acid transporter is expressed in human placenta. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C305–C312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verrey F., Closs E. I., Wagner C. A., Palacin M., Endou H., Kanai Y. (2003) CATs and HATs: the SLC7 family of amino acid transporters. Pflügers Arch. 447, 532–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jones H. N., Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2010) Full length adiponectin attenuates insulin signaling and inhibits insulin-stimulated amino acid transport in human primary trophoblast cells. Diabetes 59, 1161–1170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jansson N., Greenwood S., Johansson B. R., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2003) Leptin stimulates the activity of the system A amino acid transporter in human placental villous fragments. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 1205–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karl P. I., Alpy K. L., Fischer S. E. (1992) Amino acid transport by the cultured human placental trophoblast: effect of insulin on AIB transport. Am. J. Physiol. 262, C834–C839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karl P. I. (1995) Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates amino acid uptake by the cultured human placental trophoblast. J. Cell. Physiol. 165, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roos S., Jansson N., Palmberg I., Säljö K., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2007) Mammalian target of rapamycin in the human placenta regulates leucine transport and is down-regulated in restricted foetal growth. J. Physiol. 582, 449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roos S., Kanai Y., Prasad P. D., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2009) Regulation of placental amino acid transporter activity by mammalian target of rapamycin. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 296, C142–C150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones H. N., Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2009) IL-6 stimulates system A amino acid transporter activity in trophoblast cells through STAT3 and increased expression of SNAT2. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C1228–C1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boden G., Chen X., Mozzoli M., Ryan I. (1996) Effect of fasting on serum leptin in normal human subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 81, 3419–3423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Longo V. D., Fontana L. (2010) Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 31, 89–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yung H. W., Calabrese S., Hynx D., Hemmings B. A., Cetin I., Charnock-Jones S., Burton G. J. (2008) Evidence of translation inhibition and endoplasmic reticulum stress in the etiology of human intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 311–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yiallourides M., Sebert S. P., Wilson V., Sharkey D., Rhind S. M., Symonds M. E., Budge H. (2009) The differential effects of the timing of maternal nutrient restriction in the ovine placenta on glucocorticoid sensitivity, uncoupling protein 2, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and cell proliferation. Reproduction 138, 601–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gnanalingham M. G., Williams P., Wilson V., Bispham J., Hyatt M. A., Pellicano A., Budge H., Stephenson T., Symonds M. E. (2007) Nutritional manipulation between early to mid-gestation: effects on uncoupling protein-2, glucocorticoid sensitivity, IGF-I receptor and cell proliferation but not apoptosis in the ovine placenta. Reproduction 134, 615–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dandrea J., Wilson V., Gopalakrishnan G., Heasman L., Budge H., Stephenson T., Symonds M. E. (2001) Maternal nutritional manipulation of placental growth and glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1) abundance in sheep. Reproduction 122, 793–800 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Whorwood C. B., Firth K. M., Budge H., Symonds M. E. (2001) Maternal undernutrition during early to midgestation programs tissue-specific alterations in the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor, 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms, and type 1 angiotensin ii receptor in neonatal sheep. Endocrinology 142, 2854–2864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Coan P. M., Vaughan O. R., Sekita Y., Finn S. L., Burton G. J., Constancia M., Fowden A. L. (2010) Adaptations in placental phenotype support fetal growth during undernutrition of pregnant mice. J. Physiol. 588, 527–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lesage J., Hahn D., Leonhardt M., Blondeau B., Breant B., Dupouy J. P. (2002) Maternal undernutrition during late gestation-induced intrauterine growth restriction in the rat is associated with impaired placental GLUT3 expression, but does not correlate with endogenous corticosterone levels. J. Endocrinol. 174, 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ganguly A., Collis L., Devaskar S. U. (2012) Placental glucose and amino acid transport in calorie-restricted wild-type and Glut3 null heterozygous mice. Endocrinology 153, 3995–4007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carter A. M. (2007) Animal models of human placentation–a review. Placenta 28(Suppl. A), S41–S47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Antonow-Schlorke I., Schwab M., Cox L. A., Li C., Stuchlik K., Witte O. W., Nathanielsz P. W., McDonald T. J. (2011) Vulnerability of the fetal primate brain to moderate reduction in maternal global nutrient availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 3011–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nijland M. J., Mitsuya K., Li C., Ford S., McDonald T. J., Nathanielsz P. W., Cox L. A. (2010) Epigenetic modification of fetal baboon hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase following exposure to moderately reduced nutrient availability. J. Physiol. 588, 1349–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cox L. A., Nijland M. J., Gilbert J. S., Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N. E., Hubbard G. B., McDonald T. J., Shade R. E., Nathanielsz P. W. (2006) Effect of 30 per cent maternal nutrient restriction from 0.16 to 0.5 gestation on fetal baboon kidney gene expression. J. Physiol. 572, 67–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choi J., Li C., McDonald T. J., Comuzzie A., Mattern V., Nathanielsz P. W. (2011) Emergence of insulin resistance in juvenile baboon offspring of mothers exposed to moderate maternal nutrient reduction. Am. J. Physiol. 301, R757–R762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rodriguez J. S., Bartlett T. Q., Keenan K. E., Nathanielsz P. W., Nijland M. J. (2012) Sex-dependent cognitive performance in baboon offspring following maternal caloric restriction in pregnancy and lactation. Reprod. Sci. 19, 493–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N. E., Howell K., Rice K., Glover E. J., Nevill C. H., Jenkins S. L., Bill Cummins L., Frost P. A., McDonald T. J., Nathanielsz P. W. (2004) Development of a system for individual feeding of baboons maintained in an outdoor group social environment. J. Med. Primatol. 33, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wu G., Davis P. K., Flynn N. E., Knabe D. A., Davidson J. T. (1997) Endogenous synthesis of arginine plays an important role in maintaining arginine homeostasis in postweaning growing pigs. J. Nutr. 127, 2342–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Illsley N. P., Wang Z. Q., Gray A., Sellers M. C., Jacobs M. M. (1990) Simultaneous preparation of paired, syncytial, microvillous and basal membranes from human placenta. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1029, 218–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jansson T., Ekstrand Y., Björn C., Wennergren M., Powell T. L. (2002) Alterations in the activity of placental amino acid transporters in pregnancies complicated by diabetes. Diabetes 51, 2214–2219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pepe G. J., Burch M. G., Albrecht E. D. (2001) Localization and developmental regulation of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 and -2 in the baboon syncytiotrophoblast. Endocrinology 142, 68–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pepe G. J., Burch M. G., Albrecht E. D. (2001) Estrogen regulates 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-1 and -2 localization in placental syncytiotrophoblast in the second half of primate pregnancy. Endocrinology 142, 4496–4503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tavare J. M., Holmes C. H. (1989) Differential expression of the receptors for epidermal growth factor and insulin in the developing human placenta. Cell. Signal. 1, 55–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ling R., Bridges C. C., Sugawara M., Fujita T., Leibach F. H., Prasad P. D., Ganapathy V. (2001) Involvement of transporter recruitment as well as gene expression in the substrate-induced adaptive regulation of amino acid transport system A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1512, 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Park S. Y., Kim J. K., Kim I. J., Choi B. K., Jung K. Y., Lee S., Park K. J., Chairoungdua A., Kanai Y., Endou H., Kim D. K. (2005) Reabsorption of neutral amino acids mediated by amino acid transporter LAT2 and TAT1 in the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule. Arch. Pharm. Res. 28, 421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sankoh A. J., Huque M. F., Dubey S. D. (1997) Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat. Med. 16, 2529–2542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Foster K. G., Fingar D. C. (2010) mTOR: Conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14071–14077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ma X. M., Blenis J. (2009) Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang Q., Guan K. L. (2007) Expanding mTOR signaling. Cell. Res. 17, 666–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wullschleger S., Loewith R., Hall M. N. (2006) TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124, 471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chiang G. G., Abraham R. T. (2005) Phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) at Ser-2448 is mediated by p70S6 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 25485–25490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Holz M. K., Blenis J. (2005) Identification of S6 kinase 1 as a novel mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-phosphorylating kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 26089–26093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rosario F. J., Kanai Y., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2013) Mammalian target of rapamycin signalling modulates amino acid uptake by regulating transporter cell surface abundance in primary human trophoblast cells. J. Physiol. 591, 609–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Roos S., Lagerlof O., Wennergren M., Powell T. L., Jansson T. (2009) Regulation of amino acid transporters by glucose and growth factors in cultured primary human trophoblast cells is mediated by mTOR signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 297, C723–C731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gwinn D. M., Shackelford D. B., Egan D. F., Mihaylova M. M., Mery A., Vasquez D. S., Turk B. E., Shaw R. J. (2008) AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ma L., Chen Z., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P., Pandolfi P. P. (2005) Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell 121, 179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kawabata K., Murakami A., Ohigashi H. (2006) Citrus auraptene targets translation of MMP-7 (matrilysin) via ERK1/2-dependent and mTOR-independent mechanism. FEBS Lett. 580, 5288–5294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li C., Levitz M., Hubbard G. B., Jenkins S. L., Han V., Ferry R. J., Jr., McDonald T. J., Nathanielsz P. W., Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N. E. (2007) The IGF axis in baboon pregnancy: placental and systemic responses to feeding 70% global ad libitum diet. Placenta 28, 1200–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sferruzzi-Perri A. N., Owens J. A., Standen P., Taylor R. L., Heineman G. K., Robinson J. S., Roberts C. T. (2006) Early treatment of the pregnant guinea pig with IGFs promotes placental transport and nutrition partitioning near term. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 292, E668–E676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Desoye G., Hartmann M., Blaschitz A., Dohr G., Hahn T., Kohnen G., Kaufmann P. (1994) Insulin receptors in syncytiotrophoblast and fetal endothelium of human placenta. Immunohistochemical evidence for developmental changes in distribution pattern. Histochemistry 101, 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fang J., Furesz T. C., Lurent R. S., Smith C. H., Fant M. (1997) Spatial polarization of insulin-like growth factor receptors on the human syncytiotrophoblast. Pediatr. Res. 41, 258–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bodner J., Ebenbichler C., Wolf H., Müller-Holzner E., Stanzl U., Gander R., Huter O., Patsch J. (1999) Leptin receptor in human term placenta: in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical localization. Placenta 20, 677–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jansson T., Wennergren M., Illsley N. P. (1993) Glucose transporter protein expression in human placenta throughout gestation and in intrauterine growth retardation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 77, 1554–1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Barry J. S., Davidsen M. L., Limesand S. W., Galan H. L., Friedman J. E., Regnault T. R., Hay W. W., Jr. (2006) Developmental changes in ovine myocardial glucose transporters and insulin signaling following hyperthermia-induced intrauterine fetal growth restriction. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 231, 566–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Di Simone N., Di Nicuolo F., Marzioni D., Castellucci M., Sanguinetti M., D'Lppolito S., Caruso A. (2009) Resistin modulates glucose uptake and glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) expression in trophoblast cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 388–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jansson T., Wennergren M., Powell T. L. (1999) Placental glucose transport and GLUT 1 expression in insulin dependent diabetes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 180, 163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jansson N., Rosario F. J., Gaccioli F., Lager S., Jones H. N., Roos S., Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2012) Activation of placental mTOR signaling and amino acid transporters in obese women giving birth to large babies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, 105–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jansson T., Powell T. L. (2013) Role of placental nutrient sensing in developmental programming. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 56, 591–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Roseboom T. J., Painter R. C., de Rooij S. R., van Abeelen A. F., Veenendaal M. V., Osmond C., Barker D. J. (2011) Effects of famine on placental size and efficiency. Placenta 32, 395–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.