Letter to the Editor

CLL is an incurable B-cell malignancy and the most common form of leukemia in the Western hemisphere. Recently, we identified a previously undefined receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), Axl, in CLL B-cells(1), as a constitutively active (phosphorylated) RTK which regulates activation of multiple non-receptor cellular kinases including Lyn and PI3K/AKT(1). To this end, the finding that Axl is expressed at variable levels in CLL B-cells from CLL patients(1) indicates that its regulation is controlled at multiple levels. In addition to its known regulation by multiple transcription factors, post-transcriptional regulation, which plays a critical role in modifying and stabilizing protein levels, of Axl remains largely undefined. To explore the possibility of any such regulation in CLL, the entire 3’-untranslated region (UTR) of Axl was analyzed for complementary seed sequences of any known potential miR-binding sites (http://www.microrna.org/microrna/home.do; http://www.targetscan.org), relevant to CLL B-cell biology. The most relevant miR-binding target sequence identified was that for the miR-34a (Fig. 1A). Of interest, p53 directly regulates the expression of the miR-34 family (miR-34a/b/c); and loss of miR-34 expression is linked to resistance against apoptosis induced by p53 activating agents used in chemotherapies(2).

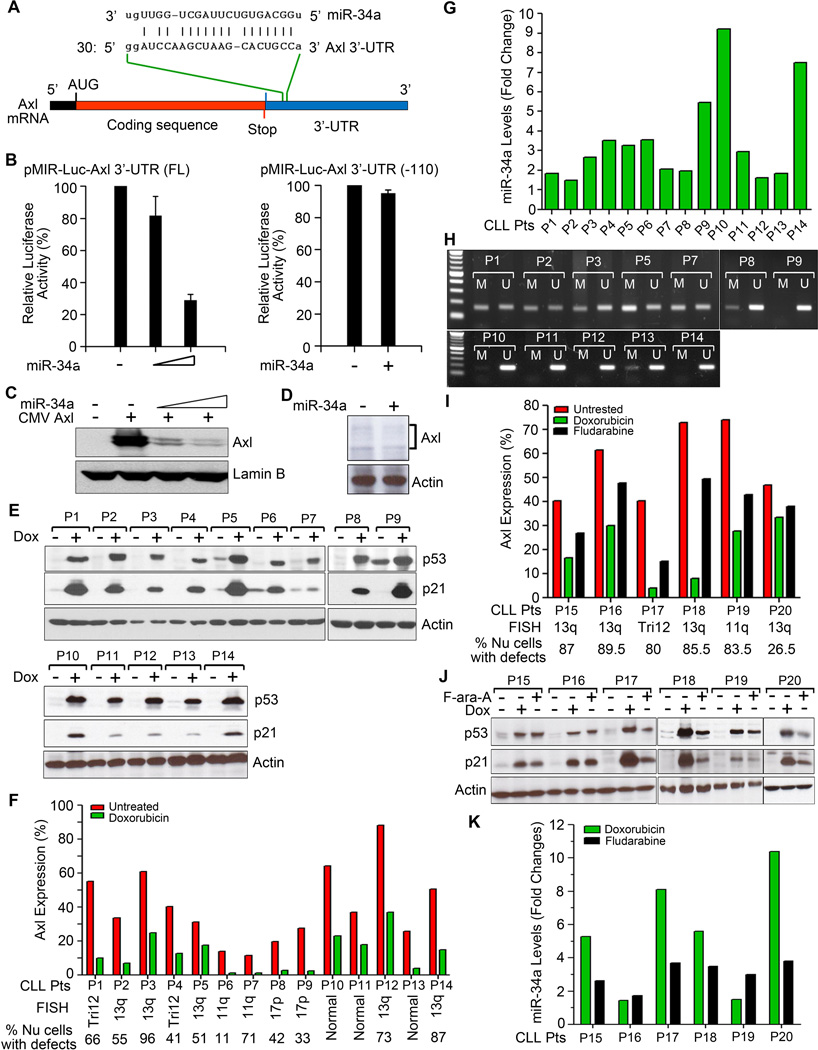

Figure 1. miR-34a targets Axl expression in primary CLL B-cells.

A. Alignment of Axl 3’-UTR with miR-34a sequence. B. miR-34a targets Axl 3’-UTR. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid DNAs containing the entire Axl 3’-UTR with a putative miR-34a-binding site (full-length) or without the miR-34a-binding site [Axl 3’-UTR (-110)] and increasing amounts of miR-34a mimic or sc- miR as control. After 24 hour, luciferase activity was measured in the cell lysates. Experiments were repeated twice in triplicates. Data were normalized and presented as mean values with standard deviations. C. Exogenous miR-34a reduces Axl expression. HEK293 cells were co-transfected with an Axl expressing plasmid DNA containing the putative miR-34a binding site in the 3’-UTR and increasing amounts of miR-34a or sc-miR for 24 hours. Cells were examined for the expression of Axl by Western blot using a specific antibody to Axl. Lamin B was used as a loading control. D. Introduction of miR-34a mimic reduces Axl expression in primary CLL B-cells. Purified CLL B-cells were transfected with miR-34a mimic or sc-miR as control using B-cell specific nucleofection reagent (Amaxa). After 24 hours, cell lysates were analyzed for the expression of Axl by Western blots using a specific antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. Representative result of CLL B-cells from 3 different CLL patients is shown. E. Doxorubicin activates p53. Lysates from purified CLL B-cells treated with doxorubicin or left untreated for 16 hours were analyzed for the expression of p53 and its downstream target p21 in Western blots using specific antibodies. Actin was used as a loading control. CLL B-cells from various CLL patients are indicated by arbitrary numbers (P1-P14). F. Impact of doxorubicin on Axl expression. CLL B-cells from the same CLL patients’ cohort (P1-P14) studied above (panel E) were treated with doxorubicin or left untreated for 16 hours. Axl expression was determined by flow cytometry using a specific antibody. Percent of cells with FISH detectable chromosomal abnormalities are indicated. G. Doxorubicin treatment activates miR-34a expression in CLL B-cells. Total RNA was extracted from untreated and doxorubicin-treated CLL B-cells and miR-34a levels were measured by qRT-PCR using primers specific for mature miR-34a and normalized using the 2-∆∆Ct method relative to U6-snRNA (RNU6B). Relative miR-34a expression levels in untreated vs. doxorubicin-treated CLL B-cells are presented as “fold changes” determined as mean of triplicate values. CLL B-cells studied here were chosen from the same cohort of CLL patients depicted and studied above in panels E&F. H. Methylation specific-PCR analysis of the miR-34a promoter in CLL B-cells. DNA isolated from purified CLL B-cells of the CLL patients (P1 - P3, P5, P7 - P14) whose miR-34a levels were studied above (panel G) were subjected to bisulfite conversion and analyzed by methylation specific-PCR (MSP) with primers specific for methylated (M) and unmethylated (U) miR-34a promoter DNA. Amplified PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel along with a standard DNA ladder (Invitrogen; 1st lane from left) to ascertain the size of the PCR products. I. In vitro Fludarabine treatment reduces Axl expression on CLL B-cells. CLL B-cells from CLL patients (P15 – P20) were treated with fludarabine (F-ara-A) for 16 hour or left untreated and Axl expression was determined by flow cytometry as described above. Doxorubicin was included as a positive control. J. Fludarabine activates p53. Cell lysates prepared from untreated, doxorubicin-treated and F-ara-A-treated CLL B-cells from CLL patients (P15 – P20) were examined for the expression of p53 and p21 in Western blot analysis. Actin was used as a loading control. K. Fludarabine upregulates miR-34a expression. Total RNA was extracted from untreated, doxorubicin-treated and F-ara-A-treated CLL B-cells from the same CLL patients used above (P15 – P20). Mature miR-34a levels were measured by qRT-PCR and presented as “fold changes” as described in panel G.

To define that the Axl 3’-UTR is a functional target of miR-34a, we first performed in vitro luciferase reporter gene assays using the reporter construct containing the entire Axl 3’-UTR and increasing amounts of miR-34a mimic or sc-miR in HEK293 cells (see supplementary information for methods). A dose-dependent reduction of the luciferase activity was observed when the reporter gene and miR-34a mimic were co-transfected (Fig. 1B, left panel). As expected, miR-34a did not show any effect on the pMIR-luc-Axl 3’-UTR(-110) reporter gene lacking the miR-34a-binding site (Fig. 1B, right panel). We also found that co-transfection of miR-34a mimic with a plasmid DNA expressing the full-length Axl gene reduced Axl expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). In addition, enforced introduction of miR-34a mimic in primary CLL B-cells reduced endogenous level of Axl (Fig. 1D). Together, these results suggest that miR-34a targets the Axl 3’-UTR and reduces Axl protein level. During progression of our study(3), two independent groups of investigators have reported a similar complementary binding site for miR-34a in the Axl 3’-UTR(4, 5) however; their findings were limited to established cell lines thus any clinical correlation was less obvious.

These initial findings became of more clinical interest as miR-34a, a direct target of p53, is reported to be associated with the adverse outcome in CLL patients(6–8). Therefore, we interrogated whether enforced activation of p53 could reduce Axl expression in primary CLL B-cells using a DNA-damaging agent, doxorubicin. Results demonstrated accumulation of p53 protein in doxorubicin-treated CLL B-cells from all the CLL patients tested (n=14; see supplementary information) who had various FISH detectable chromosomal abnormalities, albeit at variable degrees (Fig. 1E). We noted that CLL B-cells with deletion of 17p13 or 11q23 (11q23-defects: P6, P7; 17p13-defects: P8, P9) post doxorubicin exposure, accumulated lower levels of p53 and p21, the latter a direct target of p53, relative to the CLL clones with wild-type p53 or the ATM gene, an upstream regulator of p53 function (Fig. 1E). Consistent with p53-activation, substantial reduction of Axl expression on doxorubicin-treated CLL B-cells was noted including the CLL clones with heterologous deletion of the p53 or ATM gene when compared to the untreated cells (Fig. 1F). Next, to establish that it was the increased expression of miR-34a which reduced Axl expression in doxorubicin-exposed CLL B-cells, we measured the levels of mature miR-34a in these CLL B-cells. Of note, CLL B-cells do not express other members of the miR-34 family: miR-34b/c(8) which recognize the same target binding sequence as does miR-34a(2). An increase of mature miR-34a at variable levels was detected in doxorubicin-treated CLL B-cells from different patients (Fig. 1G). Interestingly, leukemic B-cells with 11q23-/17p13-defects also showed variable degrees of miR-34a upregulation in response to doxorubicin (Fig. 1G).

Multiple studies indicated that p53 could also be activated upon DNA-damage independent of ATM via Atr, Chk2 or DNA-PK(9, 10). This raised the possibility that p53 was likely to be activated in 11q23-defected CLL clones independent of ATM upon DNA-damage. However, induction of p53 and increase of p21/miR-34a in 17p13-/11q23-defected CLL B-cells in response to DNA-damage is likely due to presence of sub-population of cells without the indicated cytogenetic defects and/or these cells have retained one intact wild-type allele. To begin to explore the latter possibility, we sequenced the p53 gene (exon 4–9) in the leukemic B-cells from the two 17p13-deleted patients (P8, P9). We found that P8 had a heterozygous splice mutation after exon 4 (GT→TT) although the precise proportion of CLL B-cells that had only the heterozygous splice mutation was not known since only 42% of the CLL clone was 17p13-deleted. It is however likely that not all the CLL B-cells have this defect as this patient showed activation of the p53 axis upon DNA-damage (Fig. 1E,G). CLL B-cells from P9 harbored splice mutations on the p53 gene before exon 5 (AG→AT and GG→T) after amino acid 153 resulting in a frameshift mutation with a relative abundance of ~30% in the CLL B-cells. This was estimated by relative sequence peak heights at the respective nucleotide positions. Of note, CLL B-cells from P9 had functionally active p53 (Fig. 1E,G).

An alternative explanation for the differential levels of miR-34a in CLL B-cells could be its promoter methylation status(11, 12). The promoter region containing a p53-binding site and transcription start site of miR-34a gene has been mapped to >30 kb upstream of the mature miR-34a and is within a large (>1.5 kb) CpG island(13). Indeed, leukemic B-cells from CLL patients (P1-P3, P5, P7) who had no 17p13-defects contained both methylated and unmethylated miR-34a promoters (Fig. 1H, upper panel). Interestingly, CLL B-cells from patients (P10-P14) with no 17p13-defects exhibited predominantly unmethylated miR-34a promoter region except P13, where low level methylation of the miR-34a promoter was evident (Fig. 1H, lower panel). However, CLL B-cells from P9 with 17p13-defects had unmethylated miR-34a promoter only while P8 had trace level of methylation and a dominant level of unmethylated miR-34a promoter region (Fig. 1H, upper panel). The high level of miR-34a in P9 (Fig. 1G) is therefore likely due to both the unmethylated status of miR-34a promoter region and that significant number of the CLL clones had wild-type p53. A relatively low level of miR-34a in P8 (Fig. 1G) could be explained by the presence of methylation in the promoter region and slightly higher numbers of 17p13-defective cells. Collectively, these findings suggest that epigenetic regulation of miR-34a expression contributes to the pathobiology of CLL B-cells, independent of p53 status.

As fludarabine, a standard chemotherapeutic agent in CLL, is known to induce DNA damage, we were interested in knowing what the impact of this drug has on Axl expression in CLL B-cells. Indeed, fludarabine treatment substantially reduced Axl expression on leukemic B-cells from CLL patients (n=6; see supplementary information) (Fig. 1I) likely, due to activation of the p53/miR-34a axis in CLL B-cells (Figs. 1J–K), suggesting that reduction of Axl expression could be another mechanism by which fludarabine reduces apoptotic resistance and/or induces apoptosis in CLL B-cells.

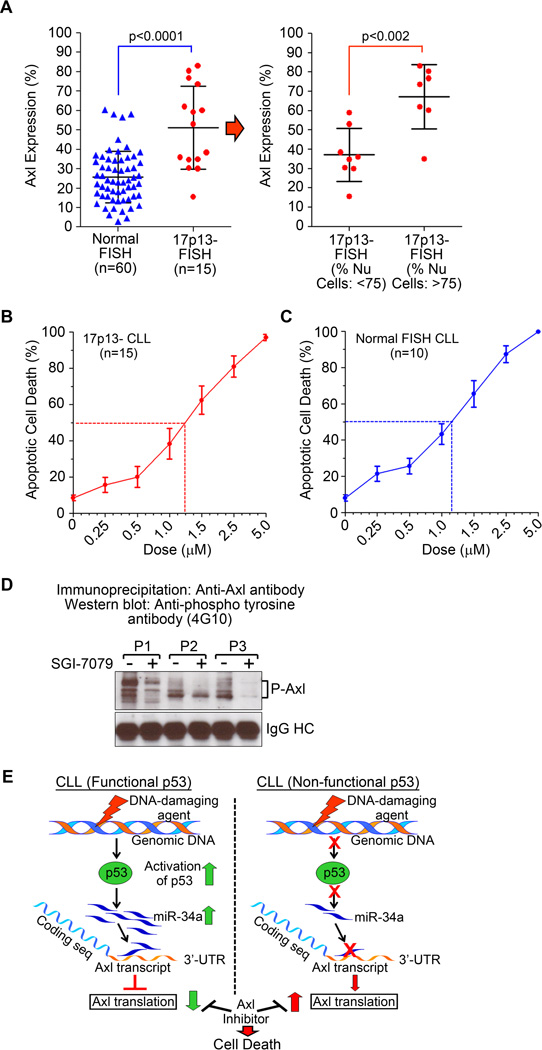

Finally, we hypothesized that CLL B-cells with 17p13-defects might express higher levels of Axl relative to those with no detectable genetic abnormalities. Indeed, a significantly (p<0.0001) higher levels of Axl expression was detected on CLL B-cells from the patients with 17p13-deletion as compared to those with no genetic abnormalities (Fig. 2A, left panel). In depth analysis of the same 17p13-cohort shows that the CLL patients with >75% CLL B-cells carrying 17p13-defects express significantly higher levels (p<0.002) of Axl compared to those patients having <75% leukemic B-cells with 17p13-defects (Fig. 2A, right panel), further indicating that CLL patients with non-functional p53 may express higher levels of Axl. To pursue Axl as a therapeutic target in 17p13-deleted CLL patients, we observed that SGI-7079, a high-affinity Axl-inhibitor (Astex), induces massive apoptosis in CLL B-cells who had 17p13-deletion in at least 40% of leukemic B-cells (n=15) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, when we compared the sensitivity of the leukemic B-cells with 17p13-defects vs. no genetic abnormalities (normal FISH; n=10) to SGI-7079, no significant difference in LD50 doses was detected (Fig. 2B-C). Importantly, SGI-7079 induces apoptosis in CLL B-cells likely by targeting Axl phosphorylation (Fig. 2D). However, we cannot completely rule out off-target effects of SGI-7079 on other RTKs. Collectively, these results suggest that Axl is a targetable RTK in CLL and provides a future therapeutic option for very “high-risk”(14) CLL patients with non-functional p53.

Figure 2. Axl RTK is an attractive therapeutic target in high-risk CLL patients with 17p13-abonormalities.

A. CLL B-cells with 17p13-defects express significantly higher levels of Axl. CLL B-cells from patients with 17p13-chromosomal defects (n=15) or no FISH detectable chromosomal abnormalities (n=60) were examined for Axl expression by flow cytometry using a specific antibody. Results demonstrate significantly increased levels (p<0.0001) of Axl on CLL B-cells with 17p13-defects as compared to that on CLL B-cells with no FISH detectable chromosomal defects (normal FISH). Further analysis demonstrates that the CLL patients containing >75% 17p13-defective CLL clones express significantly higher levels (<0.002) of Axl as compared to those having <75% 17p13-defective leukemic B-cells (right panel). B & C. Axl inhibition induces robust apoptosis in CLL B-cells. CLL B-cells from CLL patients with 17p13 chromosomal abnormalities (panel B) or normal FISH (panel C) were treated with increasing doses of the high-affinity Axl-inhibitor, SGI-7079 for 72 hours. Cells were harvested and induction of apoptosis was determined by flow cytometric analysis after staining with Annexin FITC and propidium iodide. Results are presented as mean values with standard deviations. D. SGI-7079 targets Axl phosphorylation in CLL B-cells. Purified CLL B-cells from CLL patients were treated with a sub-lethal dose of SGI-7079 for 16 hours. Axl was immunoprecipitated from equal amount of cell lysates and phosphorylation status was examined by Western blot analysis using a phospho-tyrosine-specific antibody (4G10-Platinum). Vehicle-treated cells were used as controls. IgG heavy chain is shown as a loading control. Results show a substantial level of reduction in phosphorylation of Axl in CLL B-cells following treatment with SGI-7079. CLL patients are indicated by arbitrary numbers (P1 – P3). E. Model of p53-mediated regulation of Axl in CLL B-cells. Activation of p53 via various stressors in CLL with a functional p53 inhibits translation of the Axl mRNA by activating miR-34a transcription. Accumulated miR-34a binds the single binding site on the Axl 3’-UTR and inhibits its translation resulting in reduction of Axl protein level. In CLL B-cells with a non-functional p53 (due to chromosomal deletion and/or inactivating mutation on p53 gene) this regulatory pathway remains non-functional which likely results in significant upregulation/stabilization of Axl RTK protein levels. Importantly, this study finds that Axl has the potential to be an effective therapeutic target in CLL B-cells with or without a functional p53 gene.

In summary, we found that p53 activation negatively regulates Axl expression via up-regulating miR-34a in CLL B-cells with functional p53 (Fig. 2E). Although this study found an inverse link between p53 inactivation and Axl expression in CLL B-cells, we are aware that Axl can also be regulated by other mechanisms including multiple transcription factors and/or epigenetic modulations(15). However our study uniquely adds to the growing body of literature regarding Axl regulation in human malignancies and suggests that p53-inactivation stabilizes Axl protein levels in CLL. Thus Axl inhibition in CLL should be considered and evaluated as a potential therapy (Fig. 2E).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by a Mayo Clinic Hematology Research Award 2012, Eagles Cancer Research Award and research fund from National Cancer Institute CA170006-01A1 to AKG and research fund from National Cancer Institute CA95241 to NEK. We also acknowledge Astex Corp. for providing us with the Axl inhibitor SGI-7079 and excellent secretarial help from Ms. Tammy Hughes.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no potential conflict of interest

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the Leukemia website (http://www.nature.com/leu)

References

- 1.Ghosh AK, Secreto C, Boysen J, Sassoon T, Shanafelt TD, Mukhopadhyay D, et al. The novel receptor tyrosine kinase Axl is constitutively active in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and acts as a docking site of nonreceptor kinases: implications for therapy. Blood. 2011 Feb 10;117(6):1928–1937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-305649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010 Feb;17(2):193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh AK, Boysen J, Price-troska T, Secreto C, Zent CS, Kay N. Axl Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling Pathway and the p53 Tumor Suppressor Protein Exist In A Novel Regulatory Loop In B-Cell Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2011 Nov 18;118(21):799. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mudduluru G, Ceppi P, Kumarswamy R, Scagliotti GV, Papotti M, Allgayer H. Regulation of Axl receptor tyrosine kinase expression by miR-34a and miR-199a/b in solid cancer. Oncogene. 2011 Jun 23;30(25):2888–2899. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackiewicz M, Huppi K, Pitt JJ, Dorsey TH, Ambs S, Caplen NJ. Identification of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL in breast cancer as a target for the human miR-34a microRNA. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Nov;130(2):663–679. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1690-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zenz T, Mohr J, Eldering E, Kater AP, Buhler A, Kienle D, et al. miR-34a as part of the resistance network in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009 Apr 16;113(16):3801–3808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zenz T, Habe S, Denzel T, Mohr J, Winkler D, Buhler A, et al. Detailed analysis of p53 pathway defects in fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): dissecting the contribution of 17p deletion, TP53 mutation, p53-p21 dysfunction, and miR34a in a prospective clinical trial. Blood. 2009 Sep 24;114(13):2589–2597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-224071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkstra MK, van Lom K, Tielemans D, Elstrodt F, Langerak AW, van 't Veer MB, et al. 17p13/TP53 deletion in B-CLL patients is associated with microRNA-34a downregulation. Leukemia. 2009 Mar;23(3):625–627. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirao A, Cheung A, Duncan G, Girard PM, Elia AJ, Wakeham A, et al. Chk2 is a tumor suppressor that regulates apoptosis in both an ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)-dependent and an ATM-independent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002 Sep;22(18):6521–6532. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6521-6532.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tibbetts RS, Brumbaugh KM, Williams JM, Sarkaria JN, Cliby WA, Shieh SY, et al. A role for ATR in the DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53. Genes Dev. 1999 Jan 15;13(2):152–157. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chim CS, Wong KY, Qi Y, Loong F, Lam WL, Wong LG, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of the miR-34a in hematological malignancies. Carcinogenesis. 2010 Apr;31(4):745–750. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lodygin D, Tarasov V, Epanchintsev A, Berking C, Knyazeva T, Korner H, et al. Inactivation of miR-34a by aberrant CpG methylation in multiple types of cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008 Aug 15;7(16):2591–2600. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.16.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang TC, Wentzel EA, Kent OA, Ramachandran K, Mullendore M, Lee KH, et al. Transactivation of miR-34a by p53 broadly influences gene expression and promotes apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 2007 Jun 8;26(5):745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay NE, O'Brien SM, Pettitt AR, Stilgenbauer S. The role of prognostic factors in assessing 'high-risk' subgroups of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2007 Sep;21(9):1885–1891. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mudduluru G, Allgayer H. The human receptor tyrosine kinase Axl gene--promoter characterization and regulation of constitutive expression by Sp1, Sp3 and CpG methylation. Biosci Rep. 2008 Jun;28(3):161–176. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.