Abstract

Context

Some relatively small studies suggest that maternal postnatal depression is a risk factor for offspring adolescent depression. However no large cohort studies have addressed this issue. Furthermore only one small study has examined the association between antenatal depression and later offspring depression. Understanding these associations is important to inform prevention.

Objective

To investigate the hypothesis that there are independent associations between antenatal and postnatal depression with offspring depression; and that the risk pathways are different, such that the risk associated with postnatal depression is moderated by disadvantage (low maternal education) but the risk associated with antenatal depression is not.

Design

Prospective investigation of associations between symptoms of antenatal and postnatal parental depression with offspring depression at age 18.

Setting

UK community based birth cohort (ALSPAC).

Participants

Data from over 4,500 parents and their adolescent offspring.

Main Outcome Measure

Diagnosis of offspring major depression, aged 18, using ICD-10.

Results

Antenatal depression was an independent risk factor. Offspring were 1.28 times (95% CI 1.08 to 1.51, p=0.003) more likely to have depression at 18 for each s.d increase in maternal depression score antenatally, independently of later maternal depression. Postnatal depression was also a risk factor for mothers with low education, with offspring 1.26 times (95% CI 1.06 to 1.50, p=0.009) more likely to have depression for each s.d increase in postnatal depression score. However, for more educated mothers, there was little association (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.36, p=0.420). Moderation analyses found that maternal education moderated the effects of postnatal but not antenatal depression. Paternal depression antenatally was not associated with offspring depression, while postnatally paternal depression showed a similar pattern to maternal depression.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that treating maternal depression antenatally could prevent offspring depression during adulthood and that prioritising less advantaged mothers postnatally may be most effective.

Keywords: ALSPAC, depression, antenatal, postnatal, mechanisms, moderation

Depression in late adolescence is a major public health issue worldwide. It is associated with substantial present and future morbidity and is predictive of depression persisting into adulthood1. By late adolescence the prevalence rates are particularly high2 and the depression can have a severe and persisting impact on socio-emotional functioning, education and employment. The identification of early life risk factors is important to guide prevention and intervention.

There is evidence that maternal postnatal depression (PND) is associated with problems in later child development because of the impact of depression on care-giving 3;4. It may be a period where suboptimal care-giving confers particularly high risk because of the infant’s dependence on parents 4. To date, the association between PND and offspring depression has been studied up to age 16 5;6. However, findings of an independent association with offspring depression have been inconsistent1 and sample sizes have been relatively small. To our knowledge, there have been no large published prospective cohort studies and no reports into late adolescence.

Despite receiving less attention, emerging evidence suggests that antenatal depression (AND) is associated with independent risks for child development 7;8. The mechanism for this is unclear, but if it is causal, rather than being explained by the continuation of AND postnatally, then the mechanisms for the transmission of risk from mother to foetus would differ from those related to maternal depression during the child’s life. One explanation is that cortisol, elevated in depression, passes through the placenta and directly alters fetal neural development with long-term consequences 9. One small study found an association between AND and offspring depression at age 16 6. However, the study did not have the power to distinguish the effects of AND from maternal depression at later time points. No studies have investigated the effects of AND on depression during late adolescence.

These findings raise two important questions: First, is there evidence that both AND and PND are independently associated with an increased risk of offspring depression up to age 18, and if so which period carries the greater risk? However, given that AND often continues and is the strongest predictor of PND10, large studies are required to provide sufficient power to assess whether the risks associated with AND and PND are independent. Second, is there evidence that any effects of AND and PND operate through different mechanisms? One way to investigate whether the pathways by which AND and PND influence offspring depression are different is to look at moderation effects. Moderation operates by altering the pathway from exposure (maternal depression) to outcome (adolescent depression), thus differential moderation would provide indirect evidence for different and independent pathways.

Evidence suggests that associations between PND and negative child outcomes are moderated by socio-economic status (SES): children whose mothers have the same degree of PND, but who are from higher SES, are less likely to be adversely affected than children of mothers from lower SES 3;11;12. Of the variables that constitute SES, maternal education is most strongly associated with the quality of the home environment 13; 14. One explanation for the moderating effects of SES is that education diminishes the association between maternal depression and home environmental adversity 3;13;15;16, therefore mitigating any adverse effects on offspring. This would not apply to the effects of AND if such effects result directly from the biological consequences of AND in utero. In contrast, if any effect of AND on offspring depression occurs only because AND continues postnatally, then maternal education should moderate the antenatal effect.

Investigating paternal depression may also help to understand these pathways. For example, there should be no effect of paternal AND on the child if AND has an effect through biologically mediated pathways in utero; while paternal PND may have more similar effects to maternal PND if effects operate through the home environment.

This study uses data from a large UK birth cohort. Several measurements of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms were collected during the ante- and postnatal periods and a validated interview measure of offspring depression was completed at age 18. Our questions were:

Is maternal AND and PND associated with offspring depression at age 18?

Do AND and PND have independent effects on offspring depression? If so, are the risks of different magnitude?

Does maternal education moderate the effects of PND but not AND?

Are the effects of AND, but not PND, unique to mothers?

DATA SOURCE

The sample comprised participants from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). All pregnant women resident in the former Avon Health Authority in south-west England, having an estimated date of delivery between April 1991 and December 1992, were invited to take part. The children of 15,247 pregnancies were recruited17. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Law and Ethics Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees, participants gave informed consent. Information on the ALSPAC study is available on the web site: http://www.alspac.bris.ac.uk17. Detailed information has been collected on the cohort since early pregnancy, including regular self-reported information from mothers and children and face to face assessments in research clinics. The current study uses data from the child sample (singletons only) attending the most recent research clinic.

SAMPLE

Our starting sample was those with maternal AND and PND data, n =8937. Outcome data were available for 4566 adolescents at age 18. A sample with complete data across all exposure, outcome and confounding variables (n=2847) was used to investigate main and independent effects of maternal depression. Data was available on paternal depression and education from a sample of 2475. To maximise power to examine magnitude of risk and moderation all available data from exposures and outcomes were used for these analyses. All missing data was imputed and all analyses were repeated using the same sample (n=8937).

We imputed for missing data because if those with missing data are ignored it can result in bias by making the assumption that data are missing completely at random 18. Full details of the imputation method are given in eMethod1.

MEASURES

Parental Depression

Symptoms of maternal depression were measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) 19. The EPDS is a10 item self-report depression questionnaire validated for use in the perinatal period because it avoids physical symptoms 19. It is validated for use outside of the perinatal period and in men 20;21;22. Scores of >12 have a high sensitivity and specificity in predicting clinically diagnosed major depressive disorder 21;22;23. We primarily used the continuous scores to make full use of the variation in symptoms, although we also used the >12 threshold to test for main effects.

Postal questionnaires, including EPDS measures, were administered at approximately 18 and 32 weeks antenatally and 8 weeks and 8 months postnatally. For the current study the periods of interest were pregnancy (whilst mother and fetus are physiological attached) and the first year postnatally (whilst the infant is heavily dependent on care-givers and exposed to home environment). We averaged EPDS scores across the two available measures within these a priori selected and theoretically defined periods, providing a more stable and reliable estimate of levels during that period than would be obtained using one measure alone 24 as used previously 25. The mean of the 18 and 32 weeks antenatal EPDS scores was taken as the AND measure, and the mean of the 8 weeks and 8 months postnatal EPDS scores as the PND measure. Analyses were repeated looking at the effect of each of the 4 EPDS measures separately and individual EPDS scores had comparable effects to those reported for averaged AND or PND scores.

As the EPDS is validated beyond the postnatal period, this same measure of maternal depression was used repeatedly over the child’s life, allowing us to take account of later maternal depression. We used the latest available measure of maternal depression when the children were aged 12 (closest to the 18 year outcome) to account for later maternal depression. To account for repeated exposure to maternal depression, a count of subsequent depression episodes in the child’s life was derived (number of times the mother scored >12 on any of 6 EPDS measures from ages 1 to 12). This measure is only valid if all time points are included. However, as most women only missed one or two of the EPDS questionnaires we were able to impute this variable using data from EPDS scores at other time points. Fathers also completed the EPDS at 18 weeks of pregnancy (paternal AND) and 8 months postnatally (paternal PND).

Parent Education

Mothers completed questionnaires concerning their education and their partner’s education at 32 weeks of pregnancy. Response categories were; minimal education or none, compulsory secondary level (up to age 16), non-compulsory secondary (up to age 18), or post-school university level education. Education up to age 16 (compulsory education only) was categorised as low education and post 16 education as high. Low education was relatively common (>50%). This socio-economic indicator was chosen a priori for theoretical reasons (see introduction).

Adolescent Depression

Depression in the offspring was measured using the computerised version of the Clinical Interview Schedule-Revised (CIS-R)26. The CIS-R is a computerised interview which derives a diagnosis of depression according to ICD-10 criteria. The interview is fully standardised and equally reliable whether conducted by a clinically trained interviewer or self administered on the computerised version26;27;28. The CIS-R is designed for, and has been widely used within, community samples including the National Surveys of Psychiatric Morbidity and the 1958 birth cohort 28-31. A binary variable indicating a primary diagnosis of major depression on the CIS-R or no such diagnosis was the outcome measure.

Confounding variables

Maternal characteristics identified in previous studies as being associated with maternal depression 7 or education were obtained from maternal questionnaires administered antenatally and the child’s life. These included maternal age (in years), social class (1-5), parity, history of depression before pregnancy (self-report yes/no), smoking during pregnancy, breastfeeding in the first year (none/ <3months/3 - 6 months/ >6 months), use of non-parental child-care within the first 6 months (yes/no). Smoking is important because the association between prenatal smoking and child psychiatric outcomes may reflect genetic confounding32.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Main effects

To test main effects of both AND and PND, associations of AND and PND symptoms with offspring depression were investigated in separate logistic regression models. Later maternal depression and potentially confounding variables were then included into these models.

Independent effects

To assess independent effects, both AND & PND were included into the same regression model. The reported effects reflect the association between AND and offspring depression, adjusted for PND and the association between PND and offspring depression adjusted for AND. We also investigated independent effects, by repeating each main effect analysis, excluding women reaching above thresholds for depression (>12) at the other timing (i.e. women with PND were removed from the AND analyses). The interaction between AND and PND was also investigated.

Heightened risk

In order to investigate whether the antenatal or postnatal period represents a time of heightened risk to the child, analyses were conducted to disentangle the correlated aspects of AND and PND from separable timing effects. A joint multi-level model of the outcome and maternal depression trajectories across the antenatal and postnatal period was used 33. The 4 antenatal and postnatal EPDS scores were included, modelling repeated measures within theoretically relevant ‘periods’ (period 1: pregnancy; period 2: first year postnatally) as ‘within period variation’ and this was accounted for in the model. Latent depression trajectories were summarised by two parameters a) initial levels of maternal depression in period 1 [the intercept] and b) the change in maternal depression levels across periods [the slope] using a longitudinal random effects model. Parameters were allowed to vary across individuals (random effects) and their dependence on the outcome estimated using the Bayesian approach 33. If either the antenatal or postnatal period is a period of greater risk it would be expected that there would be an effect of the change in depression across periods.

Moderating effects

Analyses were conducted to investigate whether maternal education moderated the associations between both AND and PND and offspring depression. Analyses used continuous exposure variables and compared models with and without interaction terms, testing moderation effects of maternal education using likelihood ratio tests.

Paternal depression

We investigated the association between paternal AND and PND with offspring depression at 18 and whether any effects were moderated by paternal education.

For the sample with complete exposure measures (n=8937), the mean maternal depression score was 6.7 (s.d 4.7, range 0 to 29) antenatally and 5.5 (s.d 4.4, range 0 to 27) postnatally. Measures of maternal depression were highly correlated with each other (correlations ranging from 0.6 to 0.7). The number of women who exceeded thresholds for depression antenatally (mean scores of >12 across the 2 antenatal time-points) was 1,034 (12%); and postnatally was 664 (7 %). Associations between AND and PND with socio-demographic confounding variables are given in eResults 1.

At 18 years, 4566 adolescents completed the CIS-R. A primary diagnosis of ICD-10 depression was given for 360 (8%): 3374 mothers of these adolescents had provided data on all measures of depression during the antenatal and postnatal period and 3335 also had maternal education data. Characteristics for the sample with complete CIS-R outcome and maternal depression data compared to the rest of the ALSPAC sample are given in etable 1.

MAIN & INDEPENDENT EFFECTS

The univariable results provide evidence for main effects of both AND and PND scores on offspring depression (Table 1, model 1). These results were replicated using binary EPDS variables, derived using the clinical threshold > 12 (for AND: OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.2, p=0.047; for PND: OR 1.67, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.6, p=0.026). Both associations were independent of later depression (model 2). There was little evidence that the association with AND was subject to confounding by socio-demographic variables. However, the association with PND was reduced once these variables were included (model 3). The association between AND and offspring depression remained after including PND in the same model. In contrast, the association with PND was substantially reduced once AND was included (model 4). It is difficult to draw firm conclusions from these results because the correlation between AND and PND could result in over-adjustment34. Taking account of AND by excluding women with antenatal depression diminished the association to a lesser extent (model 5). There was no evidence for an interaction between AND and PND on adolescent depression (p=0.32).

Table 1.

Odds ratio for offspring depression according to each 5 point (1 s.d) increase in antenatal and postnatal depression scores (n=2847 complete cases all variables). Model 1) univariable, 2) adjusting for later maternal depression, 3) including confounding variables, 4) whilst adjusting for the other timing and 5) whilst excluding women exceeding thresholds at the other timing.

|

Timing of maternal

depression |

Model 1: Univariable associations between each timing of maternal depression and caseness of depression at 18. |

Model 2: Model 1 with adjustments for exceeding thresholds ( >12) on the most recent maternal depression measure available (age 12) |

Model 3: Model 1 including confounding* variables ( see figure note) |

Model 4: Model 1 with adjustments for the other timing of maternal depression |

Model 5: Model 1excluding women exceeding thresholds for depression at the other timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | OR 1.28(95% CI 1.08 to 1.51) p=0.003 |

OR 1.27 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.51) p=0.003 |

OR 1.23 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.44) p=0.025 |

OR 1.27 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.59) p=0.035 (adjusted for postnatal depression) |

OR 1.29 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.55) p=0.006 (excluding women with postnatal depression ) n=2778 |

| Postnatal | OR 1.24 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.49) p=0.022 |

OR 1.21(95% CI 1.01 to 1.44) p=0.034 |

OR 1.13 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.34) p=0.188 |

OR 0.98 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.23) p=0.857 (adjusted for antenatal depression) |

OR 1.20 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.48) p=0.081 (excluding women with antenatal depression) n=2272 |

Confounding variables; maternal age, parity, social class, maternal education, maternal history of depression, smoking during pregnancy, child gender, breastfeeding in the first year and child-care.

Results were comparable when using imputed data sets; main effect (model 1) of AND (OR 1.36 [95% CI 1.18 to 1.56] p<0.0001) and PND (OR 1.29 [95% CI 1.12 to 1.49] p=0.001). Imputed data sets were used to investigate the impact of future episodes of maternal depression. The number of episodes was associated with an increased risk of offspring depression (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.22, p=0.012). However, adjusting for this did not diminish the effects of either AND (adjusted OR 1.30 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.55, p=0.001) or PND (adjusted OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.45, p=0.012).

HEIGHTENED RISK

The intercepts of mothers’ depression trajectories from the antenatal to postnatal period were positively associated with risk of offspring depression at 18; the OR for offspring depression for a 5 point increase in initial depression scores was 1.58 (95% CI 1.2 to 2.1). However, the model did not provide evidence for an effect of change in maternal depression from the antenatal to postnatal period, suggesting no difference in the magnitude of risk associated with AND and PND. The OR for offspring depression for each 5 point reduction in EPDS scores across periods was 0.77 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.8). Results were comparable after accounting for missing data.

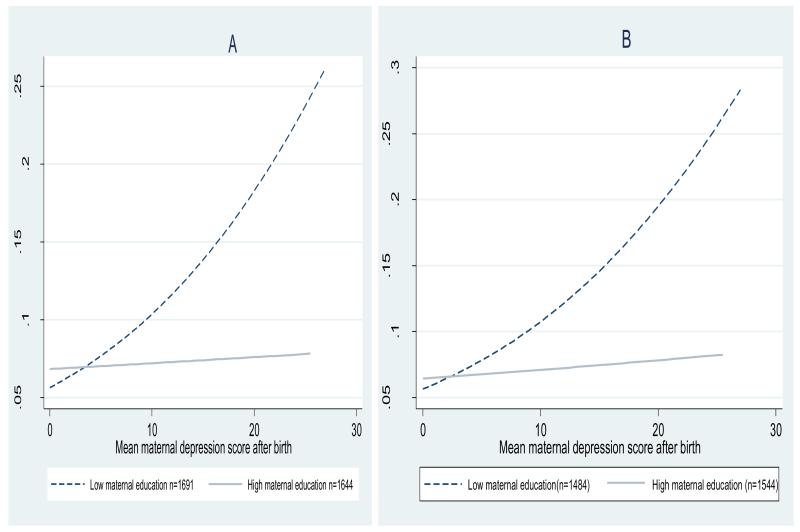

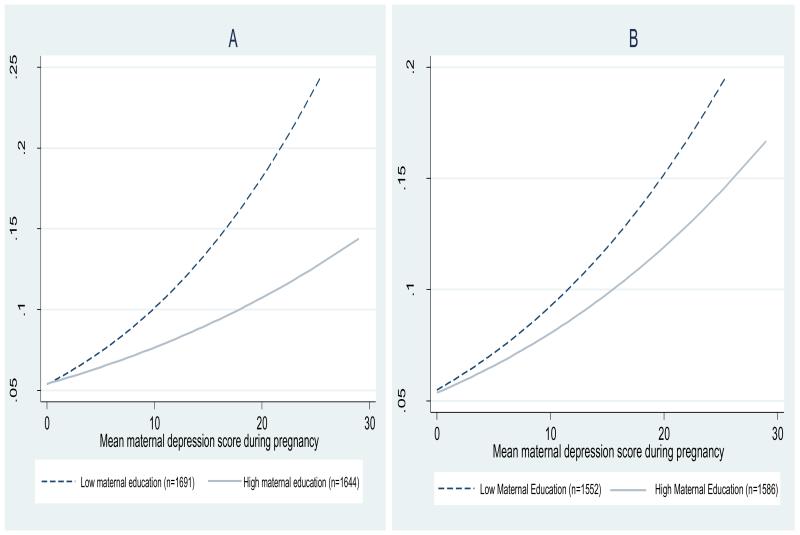

MODERATING EFFECTS

There was evidence for an interaction between PND and maternal education but no evidence for an interaction between AND and maternal education (see table 2). Stratified analyses provided evidence that the effect of PND was limited to mothers with lower education. In contrast the effects of AND were present in mothers with both high and low education. Sensitivity analyses using another SES indicator (income) found similar patterns of moderation (results available on request). Results were comparable after imputing for missing data. This pattern of moderation was replicated using a different approach, investigating moderation of AND and PND in combined model (see eResults 2 and eTable 2).

Table 2.

Odds ratio for offspring depression according to antenatal or postnatal depression and stratified by maternal education using a) continuous measures of antenatal and postnatal depression as exposure variables. Results are for those with complete data for both timings of depression and maternal education = 3335.

| Timing of maternal depression |

Exposure measure |

Whole sample N=3335 |

High maternal education N=1644 |

Low maternal education N=1691 |

Interaction term |

Test for interaction using likelihood ratio test for model with and without interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal | Mean EPDS continuous score /5 |

1.28 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.51) p=0.003 |

1.27 (1.02 to 1.57) p=0.030 |

1.34 (1.12 to 1.60) p=0.001 |

0.96 (0.9 to 1.11) p=0.179 |

chi2 =0.62, p=0.43. |

| Postnatal | Mean EPDS continuous score /5 |

1.24 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.49) p=0.022 |

1.09 (0.88 to 1.36) p=0.420 |

1.26 (1.06 to 1.50) p=0.009 |

0.93 (0.88 to 0.99) p=0.035 |

chi2 =4.52, p=0.033 |

PATERNAL DEPRESSION

There was no evidence for an association between paternal AND and offspring depression (OR for a 5 point increase in EPDS score; 0.9 [95% CI 0.7 to 1.1], p=0.187) or that this effect was moderated by paternal education (depression*education interaction p=0.742). In contrast, there was evidence for an association between paternal PND and offspring depression, however, this was limited to offspring of fathers with low education (low education; OR 1.5 [1.1 to 2.0]; high education: OR 1.0 [0.7 to 1.3], depression*education interaction p=0.048). Effects were comparable using imputed data.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to test the relative effects of depressive symptoms antenatally and postnatally on offspring depression at 18. Initial analyses provided evidence for associations between both AND and PND and adolescent depression, and these associations remained after adjusting for later maternal depression. The unadjusted effects of AND and PND did not suggest differences in the magnitude of risk to the offspring. However, after taking account of PND and adjusting for other confounders AND remained an independent predictor of outcome while the effect of PND (taking account of confounding variables and AND) was considerably weakened. Moderation analyses indicated that the effects of PND were moderated by maternal education, with only the offspring of mothers with lower education showing increased risk of adolescent depression, while adolescents whose mothers had higher education appeared unaffected. This moderation by maternal education helps to explain the diminished overall postnatal effect once maternal education was adjusted for. There was no evidence that antenatal effects were moderated in this way. Paternal AND was not associated with offspring depression. In contrast, paternal PND was associated with offspring depression, but this was limited to those whose fathers had low education.

MECHANISMS

This study does not directly test the mechanisms of transmission of depression from mother to adolescent. However, the findings of the moderation analyses and comparison of the effects of paternal depression with maternal depression provide indirect evidence that the pathways from AND and PND are different. Differential moderation of the effects of AND and PND indicates that an important part of the pathway from maternal AND to adolescent depression does not operate through AND continuing in to the postnatal period. Rather it indicates the operation of a separate pathway. Furthermore, evidence that the antenatal, but not the postnatal, effect was unique to mothers, further suggests different pathways.

Given that education is associated with several key environmental factors 13 and that education moderated the effects of PND, this is consistent with an environmental mechanism. Maternal education indicates multiple sources of psycho-social support (for example, mothers with more education were more likely to use non-maternal childcare) and positive home environments, particularly more positive and sensitive parenting 3;12, which in turn are likely to be protective in the context of depression 35;36.

In contrast, the absence of any moderation by education antenatally is consistent with the effects of AND operating through the biological consequences of depression in utero which are unlikely to be mitigated by education and associated environmental advantages. This is further supported by the absence of any effect of paternal AND on offspring outcome. To directly test this hypothesis, future studies could measure indices of the dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocorticol axis such as cortisol or catecholamines, as well as other physiological parameters antenatally 37. It is also important to note that due to the high correlation between AND and PND, overall effects of AND include both timing-specific effects and the effects of AND continuing postnatally.

It also remains possible that part of the intergenerational transmission of depression, both in the antenatal and postnatal periods, reflects shared genetic risk 32;35. The current findings suggest that any shared genetic risk associated with PND, but not AND, may be related to maternal education.

STRENGTHS & LIMITATIONS

The strengths of this study include the large sample, the long-term follow up, the repeated measures of maternal depression and the availability of confounding and moderating variables. As maternal depression was first measured 18 years earlier than the measure of child depression, reverse causality is implausible.

There were a number of limitations of the study. Adolescents who attended the 18 year assessment were more likely to come from families of higher SES than those in the original sample. Although we cannot fully explain the role of selective attrition, the pattern of missing data and analyses post imputation suggests that if anything attrition has led to an underestimation of the size of the associations between maternal and offspring depression.

A further limitation was the lack of a measure of maternal depression when the child was 18. However, we adjusted for maternal depression in early adolescence and this had little impact on the effects of AND or PND. Furthermore, any effect would be common to both AND and PND. There is no reason to believe later maternal depression would explain the differential effects observed. It is also important to note that the maternal depression measure was a self-report rather than a diagnostic interview. Importantly a clinical interview was used for the offspring outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study provides evidence that the risks associated with AND and PND are different: AND is an independent risk factor for offspring depression whilst PND may only be a risk factor in disadvantaged families. The findings have important implications for the nature and timing of interventions aimed at preventing depression in the offspring of depressed mothers. In particular, the findings suggest that treating depression in pregnancy, irrespective of background, may be most effective. However, the association between PND and risk of offspring depression appears to be greatest for children whose mothers have lower education. Hence, there may be benefit in prioritising support of more disadvantaged mothers. Further work is needed to understand why offspring of postnatally depressed mothers from low education are particularly at risk.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE 1.

A: Predicted probability of offspring depression at 18 according to the maternal depression score during the first year after birth, stratified by maternal education for the sample with exposures and outcomes n=3335. B: as 2A with the exclusion of women who exceeded thresholds for depression during pregnancy n=3028

FIGURE 2.

A: Predicted probability of offspring depression at 18 according to maternal depression score during pregnancy, stratified by maternal education for the sample with exposures and outcomes n=3335. B: as 1A with the exclusion of women who exceeded thresholds for depression after birth n=3138. Antenatal depression is strongly correlated with postnatal depression. Therefore, some of the effect of antenatal depression on child depression will be mediated through a postnatal depression pathway. This indirect pathway from antenatal depression would be moderated by education. As can be seen in figure 1B exclusion of women with postnatal depression reduced any residual moderating effects on the association between antenatal depression and child depression.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part, the midwives for help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists, and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council (Grant ref: 74882) the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 076467) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. The current project was supported by a Wellcome grant held by GL. AS supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant ref: 090139). This article is the work of the authors, and Dr Pearson will serve as guarantor for the contents of this article and the analyses of data. Dr Pearson and Dr. Kounali performed analyses. Dr Pearson had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The funders had no influence on the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest None

References

- (1).Thapar A, Collishaw S, Pine DS, Thapar AK. Depression in adolescence. Lancet. 2012;379:1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Brent DA, Weersing VR. Depressive disorders in childhood and adolescence. In: Rutter M BDPD, editor. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; Oxford: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Murray L, Halligan SL, Cooper PJ. Effects of postnatal depression on mother-infant interactions, and child development. In: Wachs T, Bremner G, editors. Handbook of Infant Development. Wiley-Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Murray L, Arteche A, Fearon P, Halligan S, Goodyer I, Cooper P. Maternal postnatal depression and the development of depression in offspring up to 16 years of age. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:460–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pawlby S, Hay DF, Sharp D, Waters CS, O’Keane V. Antenatal depression predicts depression in adolescent offspring: prospective longitudinal community-based study. J Affect Disord. 2009;113:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Evans J, Melotti R, Heron J, et al. The timing of maternal depressive symptoms and child cognitive development: a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:632–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).O’Connor TG, Heron J, Glover V. Antenatal anxiety predicts child behavioral/emotional problems independently of postnatal depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1470–1477. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Talge NM, Neal C, Glover V. Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Heron J, O’Connor TG, Evans J, Golding J, Glover V. The course of anxiety and depression through pregnancy and the postpartum in a community sample. J Affect Disord. 2004;80:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Stein A, Malmberg LE, Sylva K, Barnes J, Leach P. The influence of maternal depression, caregiving, and socioeconomic status in the post-natal year on children’s language development. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:603–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Raviv T, Kessenich M, Morrison FJ. A mediational model of the association between socioeconomic status and three-year-old language abilities: the role of parenting factors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2004;19:528–547. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Pearson RM, Heron J, Melotti R, et al. The association between observed non-verbal maternal responses at 12 months and later infant development at 18 months and IQ at 4 years: a longitudinal study. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34:525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella LV. Implications of timing of maternal depressive symptoms for early cognitive and language development. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2006;9:65–83. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Parks PL, Smeriglio VL. Parenting knowledge among adolescent mothers. J Adolesc Health Care. 1983;4:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0070(83)80369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, Henderson J, Macleod J, Molloy L, Ness A, Ring S, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA. Cohort Profile: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012 doi: 10.1093/ije/dys066. doi:10.1093/ije/dys066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Edmondson OJ, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, Netsi E, Ramchandani PG. Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. J Affect Disord. 2010;125:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Shakespeare J. Evaluation of screening for postnatal depression against the NSC handbook criteria. National Screening Committee; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hewitt C, Gilbody S, Brealey S, Paulden M, Palmer S, Mann R, et al. Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: an integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technology Assessment. 2009;13(36):1–230. doi: 10.3310/hta13360. England, NLM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ ) 2005;(119):1–8. doi: 10.1037/e439372005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bland JM, Altman DG. Regression towards the mean. BMJ. 1994;308:1499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Bowes L, Maughan B, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L. Families promote emotional and behavioural resilience to bullying: evidence of an environmental effect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:809–817. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22:465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Patton GC, Coffey C, Posterino M, Carlin JB, Wolfe R, Bowes G. A computerised screening instrument for adolescent depression: population-based validation and application to a two-phase case-control study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:166–172. doi: 10.1007/s001270050129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bell T, Watson M, Sharp D, Lyons I, Lewis G. Factors associated with being a false positive on the General Health Questionnaire. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:402–407. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Brugha TS, Morgan Z, Bebbington P, et al. Social support networks and type of neurotic symptom among adults in British households. Psychol Med. 2003;33:307–318. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Brugha TS, Meltzer H, Jenkins R, Bebbington PE, Taub NA. Comparison of the CIS-R and CIDI lay diagnostic interviews for anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1089–1091. doi: 10.1017/s0033291705005180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bebbington P, Dunn G, Jenkins R, et al. The influence of age and sex on the prevalence of depressive conditions: report from the National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2003;15:74–83. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000045976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Thapar A, Rutter M. Do prenatal risk factors cause psychiatric disorder? Be wary of causal claims. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:100–101. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.062828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Guo X, Carlin BP. Separate and joint modeling of longitudinal and event time data using standard computer packages. The American Statistician. 2004;58:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Weinberg CR. Toward a clearer definition of confounding. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Field T. Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2010;33:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ. A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1012–1024. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.