Abstract

Legally certified sturgeon fisheries require population protection and conservation methods, including DNA tests to identify the source of valuable sturgeon roe. However, the available genetic data are insufficient to distinguish between different sturgeon populations, and are even unable to distinguish between some species. We performed high-throughput single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-genotyping analysis on different populations of Russian (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Persian (A. persicus), and Siberian (A. baerii) sturgeon species from the Caspian Sea region (Volga and Ural Rivers), the Azov Sea, and two Siberian rivers. We found that Russian sturgeons from the Volga and Ural Rivers were essentially indistinguishable, but they differed from Russian sturgeons in the Azov Sea, and from Persian and Siberian sturgeons. We identified eight SNPs that were sufficient to distinguish these sturgeon populations with 80% confidence, and allowed the development of markers to distinguish sturgeon species. Finally, on the basis of our SNP data, we propose that the A. baerii-like mitochondrial DNA found in some Russian sturgeons from the Caspian Sea arose via an introgression event during the Pleistocene glaciation.

In the present study, the high-throughput genotyping analysis of several sturgeon populations was performed. SNP markers for species identification were defined. The possible explanation of the baerii-like mitotype presence in some Russian sturgeons in the Caspian Sea was suggested.

Keywords: Genotyping, glaciation, population genetics, SNP, species relationships, sturgeon

Introduction

The Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) is one of the most commercially valuable fish species in the Caspian, Azov, and Black Seas due to its role as a major caviar producer (Vlasenko et al. 35,b; Birstein and Bemis 5) and important aquaculture species (Fig. 1). Three other species are closely related to A. gueldenstaedtii: the Persian sturgeon (A. persicus), the Adriatic sturgeon (A. naccarii), and the Siberian sturgeon (A. baerii), the least abundant and hence most valuable species. Together, these four species make up the Ponto-Caspian clade of sturgeons. However, several difficulties have complicated efforts to distinguish between the various species in this clade. Acipenser persicus inhabits the Caspian Sea and cannot be readily distinguished from A. gueldenstaedtii by mitochondrial markers (Birstein et al. 8; Birstein and Doukakis 6), or by morphological or anatomical differences (Vlasenko et al. 35, b; Ruban et al. 26). Thus, the taxonomic rank of A. persicus is disputed, with some authors considering it to be a separate species (Luk'yaneko et al. 16; Putilina 22) and others regarding it to be a subspecies of A. gueldenstaedtii (Berg 3; Birstein and Bemis 5; Birstein et al. 8; Birstein and Doukakis 6; Ruban et al. 26). Although the Adriatic sturgeon uniquely inhabits the northern Adriatic Sea, it also morphologically resembles A. gueldenstaedtii (Tortonese 34). Unlike its anadromous relatives, the Siberian sturgeon is a freshwater species. Its geographical distribution includes Siberian Rivers and Lake Baikal, and does not overlap with Russian sturgeon. All these species are highly endangered, and are under the control and protection of the Convention for International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

Figure 1.

The Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) at the Astrakhan fish farm.

The unusual polyphyly of Russian sturgeons’ mitochondrial DNA further complicates their unique identification. Roughly a third of Russian sturgeon specimens from the Caspian Sea have mitochondrial DNA that is similar to that of Siberian sturgeons, which is often referred to as the “baerii-like mitotype” (Birstein et al. 8; Jenneckens et al. 11; Rastorguev et al. 23). However, baerii-like haplotypes found in the Caspian population of A. gueldenstaedtii are different from those of A. baerii in one substitution in the highly variable D-loop and can be distinguished by PCR-based test (Mugue et al. 17). Two percent of Russian sturgeons in the Azov Sea have the baerii-like mitotype (Timoshkina et al. 33). In contrast, no Persian sturgeons have been found to possess the baerii-like mitotype (Mugue et al. 17), supporting that A. persicus is genetically isolated entity. Nevertheless, mitochondrial DNA analysis can distinguish only the Siberian sturgeon from among its relatives (Mugue et al. 17).

There are several explanations of the “baerii-like mitotype” phenomenon. Some authors propose that the baerii-like mitotype arose from farmed A. baerii having escaped into the Volga River (Jenneckens et al. 11), whereas others suggest that the baerii-like mitotype and the majority A. gueldenstaedtii mitotype are ancestral mitotypes for the Siberian, Russian, and Persian sturgeon species (Birstein et al. 9). It is also possible that hybridization between Siberian and Russian sturgeons during the Pleistocene glaciation led to Siberian sturgeon mitochondrial DNA introgression, as considerable changes in the species distributions of other organisms occurred in that period (Hewitt 10).

The identification of nuclear genome markers associated with specific Ponto-Caspian sturgeon species has generally lagged behind due to the polyploidy of the sturgeon genome. It is widely accepted that polyploidization took place several times within the order Acipenseriformes. First whole-genome duplication presumably occurred in the ancestral lineage and led to formation of 2n = 120–140 (“low chromosome number”) group of species. Two independent second rounds of polyploidization were proposed: one in pacific clade, and another one in Atlantic clade of sturgeons (2n = 240–260), leading to formation of two phylogenetically unrelated groups of “high chromosome number” sturgeon species (Birstein et al. 7). Evidence suggests that low chromosome number species are tetraploids with functionally diploid genome, and high chromosome number species are octoploids, with two sets of paralogous tetrasomic loci.

The species relationship between Russian and Persian sturgeons has been addressed recently by restriction site–associated DNA (RAD) sequencing (Baird et al. 1), but the issue remains unresolved (Ogden et al. 20).

Meanwhile, high-throughput single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping provides precise sample assignment to its origin therefore it becomes highly valuable tool against illegal fishing and mislabeling. Effectiveness of such approach was shown for four commercial marine fish species (Nielsen et al. 19).

In this study, we performed high-throughput genotyping analysis of individuals from several populations of Russian, as well as Persian, and Siberian sturgeons to find SNP markers for species identification. The resulting data should aid in sturgeon conservation efforts and help prevent illegal fishing. Additionally, we suggest an explanation of the baerii-like mitotype found in some Russian sturgeons in the Caspian Sea region.

Material and Methods

RNA isolation and cDNA library construction

A several-month-old Russian sturgeon fingerling from an Astrakhan fish farm (Ltd Astrakhan Fish Breeding Company, also known as “Beluga”) was suspended in RNAlater reagent (Invitrogen/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for the preparation of a cDNA library. RNA extraction from different tissues (representing total body RNA content) was done with the TRIzol reagent according to the provided RNA extraction protocol (Invitrogen). Recent international FP6 supported project SturSNiP revealed that there is no fixed segregating genetic markers between these species, and all informative markers are frequency dependent due to sheared polymorphism (Ogden et al. 20). Our approach was different from that one of SturSNiP because our aim was to reveal highly polymorphic loci in the Caspian population of Russian sturgeon; therefore, we collected transcriptome information from a single individual rather than from pooled samples from different populations of different species. There was twofold rationale behind taking one fingerling for transcriptome analysis; first, we attempted to analyze the entire mRNA repertoire, so we needed artificially propagated fingerling to be sacrificed and the diversity of tissues to be sampled, and second, the data of allelic composition from one individual allowed us to avoid problem of paralogous (resulted from previous whole-genome duplication) loci and to discriminate paralogous loci from true polymorphic sites (see below). cDNA was prepared from total RNA by a M-MLV reverse transcriptase approach (Schmidt and Mueller 28) using the MINT cDNA synthesis kit (Evrogen, catalog #SK001). The resulting “SMART” cDNA was amplified and normalized (reducing the levels of highly abundant transcripts), using the duplex-specific nuclease (DSN) normalization method (Zhulidov et al. 37).

Transcriptome sequencing and mapping

Approximately 5 μg of nonnormalized cDNA and 10 μg of normalized cDNA were used for SOLiD library construction and sequencing using the SOLiD™ 4.0 system (Life Technologies) according to the standard protocol (SOLiD User Guide). Reads from the normalized and nonnormalized libraries were mapped against the sequence of Russian sturgeon mitochondrial DNA (NCBI accession number NC_012576.1), and all reads apparently derived from mitochondrial DNA were excluded from further mapping. The remaining reads were mapped against the sturgeon EST database from GenBank using the Bowtie software package (Langmead et al. 12). An EST-derived reference database was created using sequences bearing the “Acipenser” tag in the “species name” field (6219 sequences in total), and was then used for mapping. SNP calling was performed using the SAMtools package (Li et al. 14; Li 13). Mismatches between mapped reads were catalogued in VCF files, and heterozygous positions were then identified with a custom Perl script. SNP positions were sorted by coverage, and those that were covered by more than 100 reads were selected for the further analysis.

Sturgeon samples and genotyping

Sturgeon samples were obtained from The Russian National Collection of Reference Genetic Materials (RNCRGM), developed by the Russian CITES scientific authority on sturgeon fishes and maintained by VNIRO. Population samples of Caspian basin Russian sturgeons originated from the Volga and Ural Rivers (14 specimens each), with five additional specimens of Russian sturgeons originating from the Azov Sea; 28 Persian sturgeon specimens originated from the northern Caspian Sea; and five Siberian sturgeon specimens originated from the Lena and Irtysh rivers. DNA was isolated using the Wizard® SV 96 Genomic DNA Purification System (Promega, Fitchburg, WI).

Custom GoldenGate Genotyping Panel was constructed in Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA using loci, selected from SNP calling procedure described above (Table S1). The GoldenGate assay was performed using the Illumina GoldenGate platform according to the manufacturer's instructions and analyzed by the genotyping module of Illumina's Genome Studio data analysis software (Illumina Inc.). Loci for which all specimens showed the same genotype or genotypes could not be distinguished by this software, and were excluded from further analysis.

Genotyping data analysis

An UPGMA (unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean) tree of sturgeon populations was constructed using the POPTREE2 software (Takezaki et al. 32), with FST distances according to Latter (101). We used the Whichloci program to identify SNP loci with the highest statistical power for population assignments (Banks et al. 2). For the Whichloci analysis, we generated four simulated datasets by random resampling the SNP loci (three with sample size 100, one with sample size 500), and we then ran Whichloci on each dataset and chose loci that were present in the outcomes from all four simulated datasets. Population structure was inferred using the STRUCTURE software (Pritchard et al. 21), with parameters “prior sample location information” and “allele frequency model correlated among populations” included in the admixture model. FST statistics – the effect of subpopulations (s) compared to the total population (t) – were determined using the GenePop web service (http://genepop.curtin.edu.au/; Raymond and Rousset 24; Rousset 25), with the “FST and other correlation” options.

Results and Discussion

RNA-Seq analysis of the sturgeon transcriptome

Transcriptome data for the Russian sturgeon fingerling were generated from approximately 250 million 50-base reads of a normalized cDNA library and 80 million reads of a nonnormalized cDNA library using the SOLiD (Life Technology) platform. After removing mitochondrial DNA reads, approximately 1.7 million reads from the normalized library and 3 million reads from the nonnormalized library mapped to the GenBank sturgeon expressed sequence tag (EST) database (Table 1; note that the reduced number of mapped reads for the normalized library was expected due to the removal of ribosomal and tRNA transcripts during the normalization process; 0.3% [821,892 of 252,186,716] of normalized library reads and 4.6% [3,624,935 of 79,030,219] of control library reads were mapped on ribosomal database). From 6219 totals, 4300 ESTs were covered by at least one read. The overall low numbers of mapped reads could be explained by the fact that the database contains mainly A. sinensis and A. transmontanus ESTs, which are distantly related to A. gueldenstaedtii.

Table 1.

SOLiD read mapping and SNP calling statistics for two Acipenser gueldenstaedtii cDNA libraries

| Normalized cDNA library | Nonnormalized cDNA library | |

|---|---|---|

| Total reads | 252,186,716 | 79,030,219 |

| Mapped reads | 1,787,162 | 3,159,679 |

| Total SNPs called | 1,014,088 | 755,147 |

| Heterozygous SNP | 50,124 | 30,682 |

| SNPs (coverage ≥10) | 611,971 | 415,411 |

| Heterozygous (coverage ≥10) | 45,645 | 27,143 |

| SNPs (coverage ≥100) | 181,683 | 138,058 |

| Heterozygous (coverage ≥100) | 17,765 | 9812 |

Read mapping was performed using the sturgeon EST database as a reference. SNP calling was done with default SNP caller settings (using SAMtools) and with minimum coverage depths of 10 and 100.

SNP discovery for sturgeon genotyping and population identification

Several thousand SNP candidates were identified by screening heterozygous positions using the following criteria of read sequence quality, read mapping quality, and quality score at the mismatch position. Additionally, we required that the presumptive SNPs have allele ratios close to 3:1 based on the following assumptions: “high chromosome number” sturgeons, including three species in our study, have two sets of paralogous tetrasomic loci (total eight similar genomic regions, segregated as two tetrasomic loci), special precaution was applied to avoid erroneous considering alternatively fixed paralogous loci as a polymorphic locus. Thus, alleles with 1:1 ratios would likely represent divergent paralogous loci which would not be polymorphic across individuals in a population. Therefore, we sought to identify genotypes where one tetrasomic set of alleles was heterozygous and the other locus (paralog) was homozygous. Allelic ratio 3:1 would likely represent situation when one paralog is fixed (i.e., AAAA) and the other one is polymorphic (AABB). Total 384 of the best-scoring mismatch positions were chosen for a GoldenGate custom SNP panel (Illumina) for sturgeon genotyping (Table S1). The GoldenGate assay revealed that 123 of the 384 variable loci were successfully genotyped; the others appeared homozygous or heterozygous across all individuals (fixed at the same or alternative alleles at paralogous loci) and were excluded from further analysis. Loci that appeared heterozygous across all individuals most likely reflected the presence of a paralogous locus, creating the appearance of two different alleles.

Analysis of sturgeon population structure

To perform a population structure analysis, genotype calls were filtered from the Illumina Genome Studio report into the STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al. 21) and GenePop (Raymond and Rousset 24) programs. The Whichloci program (Banks et al. 2) guided the choices of the most informative loci for population assignment. We detected few genetic differences at the 123 diagnostic positions between the Volga River and Ural River populations of Russian sturgeons. Eight of the most informative SNP loci were sufficient to assign specimens to the Caspian Russian (Volga and Ural River) populations, Russian Azov Sea population, and Persian populations with 80% accuracy. A total of 12 loci were sufficient to make these population assignments with 90% accuracy (Table 2).

Table 2.

DNA sequences of the 12 SNP candidate markers used for sturgeon population assignment

| Marker name | DNA sequence |

|---|---|

| EV824350.93 | TTCGATACGATAAGCCGCAATGTCTGCAGGAACACTGGCTAAACCCGCAATGCGCGGTCT[A/G] CTCGGTAAACGTCTACGATTCCACCTGGCTGTTGCTTTCACGCTGTCTTTGGCTGCAGCA |

| ES698489.358 | ATTTTAAAGTGGARCCCTTTGTTGTTGATTCCTGGTTTAAATTTCCAGCACCTTCACAAA[A/T]TC CAGTAAGAAAGACATGTGAAGTAGACMSTGGCCGTGTATTTCAGATGTGCTCTGATAA |

| DR977078.72 | TTGCCCAGGTCTTGAACAATATGCTATCAAGAAGTTTGCAGAGGCTTTTGAAGCCATTCC[A/G]C GTGCTCTTGCAGAGAACTCTGGTGTCAAGGGCAATGAACTTATCTCCAAACTGTATGCT |

| DR976209.314 | GAACAGTGCACTCCACAAGAATTGTTTTTAGCCGTATAACTTCAAGAACAGAAAACTAAG[T/C] TGCATTATGAGTGGAGGAAGACAGATGACTGCGCTACTGTACACCCCTTTTACAACAASA |

| DR977006.239 | CTCTTTCACCTTTGAGCTTCGTGATACTGGCAGATATGGATTCCTCCTTCCAGAGTCGCA[A/G]A TCAGGCCAACTTGCCAAGAAACAATGCTGGCAGTCAAATACATTGCCAAACATGTTCAG |

| EV824380.474 | CCAAGGGCAATGTACCGCAACTTCTGGAGCCCATCCCATACGAGTTCATGGCGTAAAGCA[T/C] GGTCAAGCCAGAATAAAGTCCTGTTTTCAACAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANAAANNNA |

| DR976578.395 | TTTCCCCATCAATGTGGTCGTTCAGGAAACTGGGTCTCTGGTGGAAATCAGGAATTTCTT[A/G]G GAGAAAAGTACATCCGCAGAGTACGCATGAGGCAGGGTGTGACCTGTAATGTTTCCCAG |

| DR975536.188 | TAGAAGAGGGCGCCTGACCAAGCACACCAAGTTYGTTCGGGACATGATCCGCGAGGTGTG[T/C] GGCTTCGCCCCCTACGAGAGACGCGCCATGGAGCTGCTGAAGGTCTCCAAGGATAAGCGM |

| DR977561.396 | GAAGTTTGCCTGCAATGGGACTGTGATTGAGCATCCAGAATATGGTGAAGTGGTTCAGCT[A/G] CAGGGTGATCAGCGCAAGAATATCTGCCAGTTCCTTACTGAGATTGGCTTGGCTAAGGAG |

| ES698197.350 | AACAAGCCAAGGACAAGCCCCAGGAGAAACCCAAATAACATGGCAAGAGRACTAACCATC[A/G] CTTACAAGAGAAGTTTCAATCTCCGACACAAGCTTCCTGTCTGGGATTTCATTTTCMTTT |

| DR974886.648 | TTGGTACCGTGTATCTCTCTGCTCTGGCTTTATAATGATGGGTGTCACCGTATATGAAGG[A/G]G GCACCTGGTAATGCASATGGTAAACCAATCAGTAATGTAAAGAATTGGATGCAATAAAG |

| ES697699.316 | GAGAAGATYGACCTGAAGTTCAACCACCTCCAAGTTCGGACACGGACGCTTCCAGACCGC[T/C] GAAGAGAAGAAGGCGTTCATGGGACCACTCAAAAAGGACCGAATCCTCAAGGAGGAGACT |

Each polymorphic position is shown in square brackets. Sequence names consist of the GenBank accession number of the candidate EST sequence, with the SNP position within the EST given after the period.

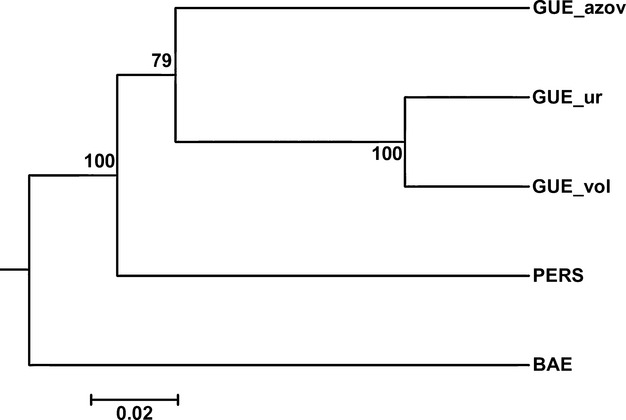

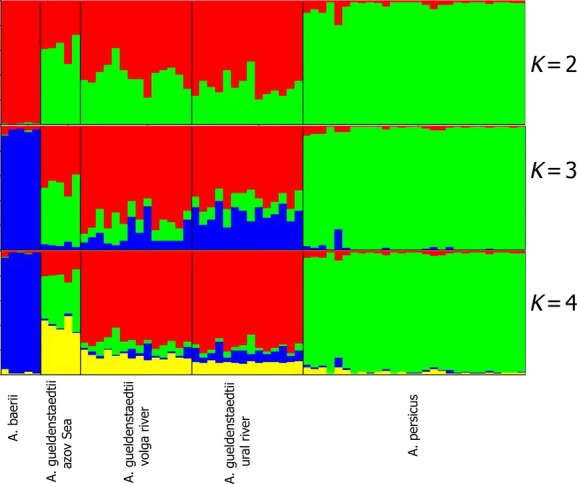

Using the allele frequencies within each population for all 123 polymorphic SNP loci (taken from the Genome Studio report), we constructed a population tree (Fig. 2). As expected, the Siberian sturgeons appeared more distant from the other species of the Ponto-Caspian clade. Our data also indicated that the Persian sturgeon was separated from all three samples of the Russian sturgeon, suggesting that A. persicus is genetically different from all A. gueldenstaedtii populations. These data do not support an opinion of Ruban et al. (26) that A. persicus is an ecological morph within the Caspian Sea population of Russian sturgeon, but not a valid species. The population assignment analysis (STRUCTURE) also supported the genetic separation of the Persian sturgeon, as a homogeneous cluster consisted exclusively of A. persicus specimens (Fig. 3). The Siberian and Persian populations were clearly separated into two distinct groups, whereas the Russian sturgeons appeared as intermediate and shared population structure elements of both the Siberian and Persian sturgeons. This is likely due to nature of our SNP loci when polymorphic loci were obtained from Russian sturgeon specimen.

Figure 2.

UPGMA tree showing the relationships of sturgeon populations (POPTREE2; Takezaki et al. 32). Genetic distances (FST) between the populations (Latter 101) were estimated using allele frequency data for 123 loci. Bootstrap values are indicated next to corresponding nodes. GUE_azov, Acipenser gueldenstaedtii from the Azov Sea; GUE_ur, A. gueldenstaedtii from the Ural River; GUE_vol, A. gueldenstaedtii from the Volga River; PERS, A. persicus; BAE, A. baerii. (The Ural and Volga River sturgeons are considered to be representative of Caspian Sea Russian sturgeons.)

Figure 3.

Population structure analysis of various sturgeon samples using the STRUCTURE software. Three runs of STRUCTURE with the cluster number (K) set to two, three, or four are shown. Siberian (Acipenser baerii) and Persian (A. persicus) sturgeons form their own distinct clusters, whereas all three Russian sturgeon populations have mixed origins.

Siberian sturgeon introgression into Caspian Russian sturgeon population during the Pleistocene glaciation

Frequency of several SNPs of the Caspian (Volga and Ural Rivers) populations of Russian sturgeon shows an intermediate value compared to those in Siberian and Persicus populations, indicating that Caspian population of the Russian sturgeon retains traces of ancient introgression of Siberian sturgeon into ancestral Caspian population of the Russian sturgeon during the Pleistocene glaciation. These data support the hypothesis that the baerii-like mitotype is a result of this ancient introgression. The climatic oscillations during the glaciation caused great changes in species distribution, and considerable evidence suggests that other organisms dispersed to new locations (Hewitt 10). An investigation of 41 North American fish species concluded that the Pleistocene glaciation had a great impact on fish population structure (Bernatchez and Wilson 4). The presence of distinct mitochondrial DNA sequences within a species has been explained as a consequence of intraspecific lineage reorganization, whereby the dispersed lineages of an ancestral set of refugees reunite in one formerly glaciated region (Taberlet and Bouvet 31; Santucci et al. 27).

Notably, the hypothesis of the interspecific hybridization is required to explain abundance of the baerii-like mitotype and nuclear markers in the Caspian population of A. gueldenstaedtii. This scenario is supported by evidence that hybridization between Russian and Siberian sturgeons leads to the formation of fertile hybrids (Jenneckens et al. 11), which are widely used in aquaculture. Considering that the glaciation allowed the Siberian sturgeons into the Caspian Sea, there may have been nothing to prevent their hybridization with Caspian sturgeons. Previously published data that “baerii-like” mitotypes are present in the Caspian Russian sturgeon population and absent from the Persian population are consistent with this notion (Mugue et al. 17).

Conclusions

In this study, we discovered SNP markers for distinguishing between Caspian and Azov Sea populations of Russian sturgeons, as well as between Russian, Persian, and Siberian sturgeons. These data allow the development of a genetic test that can be used for law enforcement in sturgeon fishery, aquaculture industry, and trading, as well as in conservation efforts for endangered sturgeon species. Finally, our SNP analysis supported the idea that the mitochondrial DNA polyphyly of Russian sturgeons in the Caspian Sea resulted from an introgression event during the Pleistocene glaciation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthon Teslyuk for useful discussions and for technical support with the computer cluster of the NRC Kurchatov Institute, Maria Tolochkova for help in obtaining samples from the RNCSGM genetic material collection, and Aleksey Sergeev and Nikolay Chekanov for comments and discussion.

Data Accessibility

The SOLiD sequence data in .csfasta + .quality formats, mapped data in SAM/BAM formats, and SNP variants in .vcf format are available on request.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

References

- Baird NA, Etter PD, Atwood TS, Currey MC, Shiver AL, Lewis ZA, et al. Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks MA, Eichert W, Olsen JB. Which genetic loci have greater population assignment power? Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1436–1438. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg LS. Acipenser guldenstadti persicus, a sturgeon from the south Caspian Sea. Ann. Mag. Hist. London Ser. 10. 1934;13:317–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatchez L, Wilson CC. Comparative phylogeography of nearctic and palearctic fishes. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:431–452. [Google Scholar]

- Birstein VJ, Bemis WE. How many species are there within the genus Acipenser. In: Birstein VJ, Waldman JR, Bemism WE, editors. Sturgeon biodiversity and conservation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997. pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Birstein VJ, Doukakis P. Molecular identification of sturgeon species: science, bureaucracy, and the impact of environmental agreements. In: Riede K, editor. New perspectives for monitoring for migratory animals. Bonn, Germany: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation; 2001. pp. 47–63. International Workshop on Behalf of the 20th Anniversary of the Bonn Convention. [Google Scholar]

- Birstein VJ, Poletaev AI, Goncharov BF. DNA content in Eurasian sturgeon species determined by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1993;14:377–383. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birstein VJ, Doukakis P, DeSalle R. Polyphyly of mtDNA lineages in the Russian sturgeon, Acipenser gueldenstaedtii: forensic; evolutionary implications. Conserv. Genet. 2000;1:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Birstein VJ, Ruban G, Ludwig A, Doukakis P, DeSalle R. The enigmatic Caspian Sea Russian sturgeon: how many cryptic forms does it contain? Syst. Biodivers. 2005;3:203–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt G. The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature. 2000;405:907–913. doi: 10.1038/35016000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenneckens I, Meyer JN, Debus L, Pitra C, Ludwig A. Evidence of mitochondrial DNA clones of Siberian sturgeon, Acipenser baerii, within Russian sturgeon, Acipenser gueldenstaedtii, caught in the River Volga. Ecol. Lett. 2000;3:503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latter BD. Selection in finite populations with multiple alleles. 3. Genetic divergence with centripetal selection and mutation. Genetics. 1972;70:475–490. doi: 10.1093/genetics/70.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. Improving SNP discovery by base alignment quality. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1157–1158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk'yaneko VI, Umerov ZG, Karataeva BB. The Southern sturgeon is a separate species within the genus Acipenser. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Biol. 1974;5:736–739. . (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugue NS, Barmintseva AE, Rastorguev SM, Mugue VN, Barmintsev VA. Polymorphism of the mitochondrial DNA control region in eight sturgeon species and development of a system for DNA-based species identification. Rus. J. Genetics. 2008;44:793–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen EE, Cariani A, Mac Aoidh E, Maes GE, Milano I, Ogden R, et al. Gene-associated markers provide tools for tackling illegal fishing and false eco-certification. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:851. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden R, Gharbi K, Mugue N, Martinsohn J, Senn H, Davey JW, et al. Sturgeon conservation genomics: SNP discovery and validation using RAD sequencing. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:3112–3123. doi: 10.1111/mec.12234. . doi:10.1111/mec.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putilina LA. Morphological characteristics of the Persian sturgeon in the Volga River. In: Belyaeva VN, editor. Complex utilization of biological resources of the Caspian and Azov Seas. Moscow, Russia: VNIRO; 1983. pp. 70–71. (in Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rastorguev S, Mugue N, Volkov A, Barmintsev V. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence analysis of Ponto-Caspian sturgeon species. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2008;24:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond M, Rousset F. GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 1995;86:248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F. genepop'007: a complete re-implementation of the genepop software for Windows and Linux. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2008;8:103–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruban GI, Kholodova MV, Kalmykov VA, Sorokin PA. A review of the taxonomic status of the Persian sturgeon (Acipenser persicus Borodin) J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2011;27:470–476. [Google Scholar]

- Santucci F, Emerson B, Hewitt GM. Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of European hedgehogs. Mol. Ecol. 1998;7:1163–1172. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt WM, Mueller MW. CapSelect: a highly sensitive method for 5′ CAP dependent enrichment of full-length cDNA in PCR mediated analysis of mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e31. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.21.e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taberlet P, Bouvet J. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism, phylogeography, and conservation genetics of the brown bear (Ursus arctos) in Europe. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1994;255:195–200. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezaki N, Nei M, Tamura K. POPTREE2: software for constructing population trees from allele frequency data and computing other population statistics with Windows interface. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:747–752. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timoshkina NN, Barmintseva AE, Usatov AV, Miuge NS. Intraspecific genetic polymorphism of Russian sturgeon Acipencer gueldenstaedtii. Genetika. 2009;45:1250–1259. . (in Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortonese E. Acipenser naccarii Bonaparte, 1836. In: Holcik J, editor. The freshwater fishes of Europe. Vol. 1, Part II. General introduction to fishes, Acipenseriformes. Wiesbaden, Germany: AULA-Verlag; 1989. pp. 284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasenko AD, Pavlov AV, Sokolov LI, Vasiĺev VP. Acipenser gueldenstaedti Brandt, 1833. In: Holcík J, editor. The freshwater fishes of Europe. General introduction to fishes, Acipenseriformes. 1 II. Wiesbaden, Germany: AULA-Verlag; 1989a. pp. 294–344. [Google Scholar]

- Vlasenko AD, Pavlov AV, Vasil'ev VP. Acipenser persicus Borodin, 1897. In: Holcik J, editor. The freshwater fishes of Europe. Vol. 1, Part II. General introduction to fishes. Acipenseriformes. Wiesbaden, Germany: AULA-Verlag; 1989b. pp. 344–366. [Google Scholar]

- Zhulidov PA, Bogdanova EA, Shcheglov AS, Vagner LL, Khaspekov GL, Kozhemyako VB, et al. Simple cDNA normalization using kamchatka crab duplex-specific nuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The SOLiD sequence data in .csfasta + .quality formats, mapped data in SAM/BAM formats, and SNP variants in .vcf format are available on request.