Abstract

Development of ecofriendly and reliable processes for the synthesis of nanoparticles has attracted considerable interest in nanotechnology because of its tremendous impetus in modulating metals into nanosize to their potential use for human benefits. In this study an endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp., isolated from healthy leaves of Curcuma longa (turmeric) was subjected to extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNps) and their activity against MDR E. coli and S. aureus. The biosynthesized AgNps optimization was studied and characterized by UV-visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Then produced AgNps were tested against MDR E. coli and S. aureus. The endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. from healthy leaves of C. longa (turmeric) was found to be a good producer of AgNps. Parametric optimization showed maximum absorbance of 420–425 nm at pH-7, 25°C with 1 mM AgNO3 concentration and 15–20 g of wet biomass. Further TEM revealed the formation of spherical, well-dispersed nanoparticles with size ranging between 25 and 30 nm and FTIR shows the bands at 1644 and 1538 cm−1 corresponding to the binding vibrations of amide I and II bands of proteins, respectively. Antibacterial activity against MDR E. coli and S. aureus showed good results showing maximum zone of inhibition of 17 mm and 16 mm, respectively, at 80 µL of AgNps.

1. Introduction

Resistance in human pathogens is a big challenge in fields like pharmaceutical and biomedicine. Antibiotic resistance profiles lead to fear about the emergence and reemergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens [1]. These MDR pathogens require multiple treatments of broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are less effective, more toxic, and more expensive [2]. Therefore, development of or modification in antimicrobial compounds to improve bactericidal potential is a priority area of research in the modern era [3]. Nanotechnology is an emerging field with its application in science and technology for the purpose of synthesis and development of nanomaterials at the nanoscale level [4]. The use of metal nanoparticles is gaining impetus in the present century due to their optical, electrical, and catalytic properties. To utilize and optimize physical properties of nanosized metal particles large spectrums of research have been focused to control the size and shape, which is crucial in tuning their physical, chemical, and optical properties [5–7].

Various techniques, such as chemical, physical, and mechanical techniques, have been developed to prepare metal nanoparticles, as these methods are costly, toxic, and nonecofriendly. A green synthesis of nanoparticles with the help of biological sources like plant and microorganisms is carried out because they are less toxic to human and environment [8]. Different types of metal nanoparticles are produced, copper, zinc, titanium [9], magnesium, gold [10], alginate [11], and silver; of them silver nanoparticles (AgNps) have proved to be most effective as they have good antimicrobial efficacy against bacteria, viruses, and other eukaryotic microorganisms [12]. The researchers are moving towards nanoparticles especially silver nanoparticles to solve the problem of emerging human pathogens [13, 14]. Silver nanoparticles are more effective because of the high surface area to volume ratio so that a large proportion of silver nanoparticles are in direct contact with their environment [15]. By using fungi and bacteria various studies on biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles have been demonstrated [16, 17]; one such clique of microbes is the endophytes whose potential biosynthesis of nanoparticles has not been studied completely. Bacon et al. [18] defined endophytes as “microbes that colonize living internal tissues of plants without causing any immediate, overt negative effects,” whereas Strobel and colleagues [19] suggested that the relationship can range from mutualistic to bordering on pathogens. Very few reports are available wherein endophytic fungi were used for the synthesis of nanoparticles. Therefore, in the present study, we have used endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. isolated from healthy leaves of Curcuma longa (turmeric) for the extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles, its optimization, and characterization studies; to obtain monodispersed silver nanoparticles its efficacy against MDR E. coli and S. aureus strains, was studied.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Endophytic Fungi

Healthy leaves of Curcuma longa (turmeric) were collected from the Department of Botany, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga. The leaves brought to the laboratory were washed several times under running tap water and cut into small pieces. These pieces were surface sterilized by sequential rinsing into 70% ethanol (C2H5OH) for 30 sec, 0.01% mercuric chloride (HgCl2) for 5 min, 0.5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), and 2-3 minutes with sterile distilled water and then allowed to dry under sterile conditions. The cut surface of the segment was placed on petri dish containing (potato dextrose agar) PDA supplemented with streptomycin sulfate (250 μg/mL), incubated at 28°C for 3-4 days, and monitored every day for the growth of endophytic fungal colony from leaf segment. The fungi which grew out from leaf segment were isolated and brought into pure culture onto other PDA plates. The fungal isolate was identified based on its morphological and reproductive characters using standard identification manual [20].

2.2. Extracellular Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

The isolated endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp., was grown in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask. About 100 mL of malt glucose yeast peptone (MGYP) broth [21] contained yeast extract and malt extract, 0.3% each, glucose, 1%, and peptone, 0.5%, at 25°C in static position. After 72 h of incubation the mycelial biomass was separated by filtration and then extensively washed with distilled water to remove the traces of media components. This biomass was taken into flasks containing 100 mL distilled water and incubated at the same position for 48 h. The suspension was filtered with Whatman filter paper number 1 and was used. Further, the fungal filtrate was mixed with aqueous solution AgNO3 of 1 mM concentration for reduction [20].

2.3. Optimization Studies for Silver Nanoparticles Production

There is always a continuous interaction between organism and the environment in which they live. The environmental conditions exert an influence on growth and development of organism. The enzyme production by fungi is influenced by the condition in which the organisms are cultivated [21, 22]. Therefore, optimization studies will not only support good growth but also enhance product yield.

2.3.1. Effect of AgNO3 Concentration

The production of nanoparticles is also dependent on substrate concentration. The concentration of AgNO3 from 0.5 to 2.0 mM was studied with a difference of 0.5 mM. The optimum concentration for the synthesis of nanosilver is confirmed by UV-visible absorption spectroscopy.

2.3.2. Effect of pH

pH has a strong influence on growth and enzyme production which is required for the biosynthesis of AgNps. Different pH ranging from 4.0 to 8.0 was used with the difference of 1.0 to study the influence of pH on AgNps production from endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp.

2.3.3. Effect of Temperature

Temperature plays a very important role in all reactions. Optimization studies with respect to temperature were carried out with temperature ranging from 20°C to 40°C with difference of 5°C on endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp. for AgNps production. The sample was analyzed with UV-visible absorption spectroscopy and further effect of temperature on nanoparticles was studied.

2.3.4. Effect of Biomass Concentration

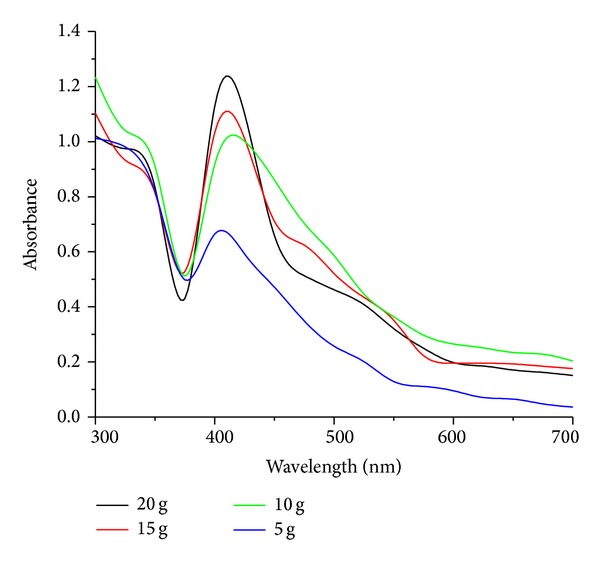

The effect of biomass concentration on the extracellular synthesis of AgNps was studied by exposing 5 to 20 g of wet biomass with a difference of 5 g of endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. Biosynthesis of nanosilver particles at different biomass concentrations was characterized by UV-visible absorption spectroscopy.

2.4. Characterization Studies for Silver Nanoparticles

2.4.1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

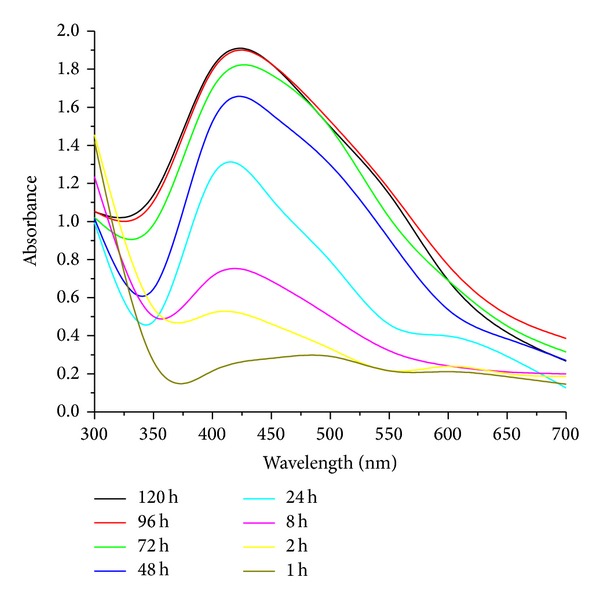

The formation of AgNps was preliminarily confirmed by visual observation of color change from pale white to reddish brown, further by UV-visible spectra at different time intervals. Sharp peak given by UV-visible spectrum confirms silver nanoparticle at the absorption range between 400 and 450 nm.

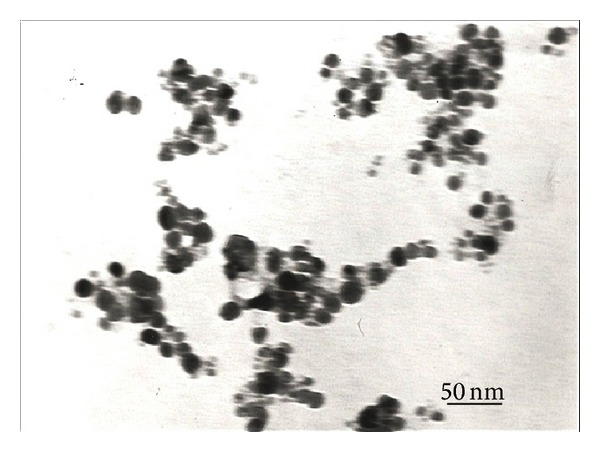

2.4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Characterization of AgNps was done by TEM (Hitachi-H-7500) to know the size and shape of nanoparticles. The samples were prepared by drop-coating the AgNps solution onto the carbon-coated copper grid and were loaded onto a specimen holder. TEM micrographs were taken and then sizes and shape of AgNps were confirmed.

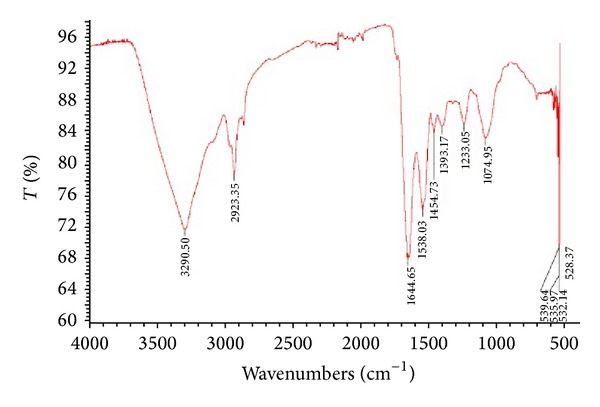

2.4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The AgNps synthesized were air-dried at room temperature and were subjected to FTIR analysis in the range of 500 to 4000 cm−1. The probable biomolecules responsible for reduction, capping, and effective stabilization of the AgNps were recorded using FTIR spectrophotometer at diffuse reflectance mode.

2.5. Analysis of Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles against MDR E. coli and S. aureus Strains

2.5.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assay of Clinical Isolates

The clinical isolates were collected from the diagnostic labs of the Gulbarga district and tested for the sensitivity against different antibiotics by subculturing the bacterial cultures, incubated at 37°C for 5-6 h to moderate turbidity. Then lawn of pathogenic bacteria was prepared on nutrient agar plate using sterile swabs and then antibiotic disc was kept aseptically on the lawn plate and incubated at 37°C for 24 h and then results were monitored.

2.5.2. Antibacterial Assay of Silver Nanoparticles against MDR E. coli and S. aureus

Antibacterial assay was done on MDR E. coli and S. aureus strains using agar well diffusion assay method [23, 24]. The test organisms were grown in nutrient broth for 5-6 h lawn of MDR bacteria which was prepared on nutrient agar plates using sterile swabs. Agar wells were made on nutrient agar plates using gel puncture and each well was loaded with 20 μL, 40 μL, 60 μL, and 80 μL, respectively, of AgNps solution and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The zone of inhibition was measured.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation of Endophytic Fungi

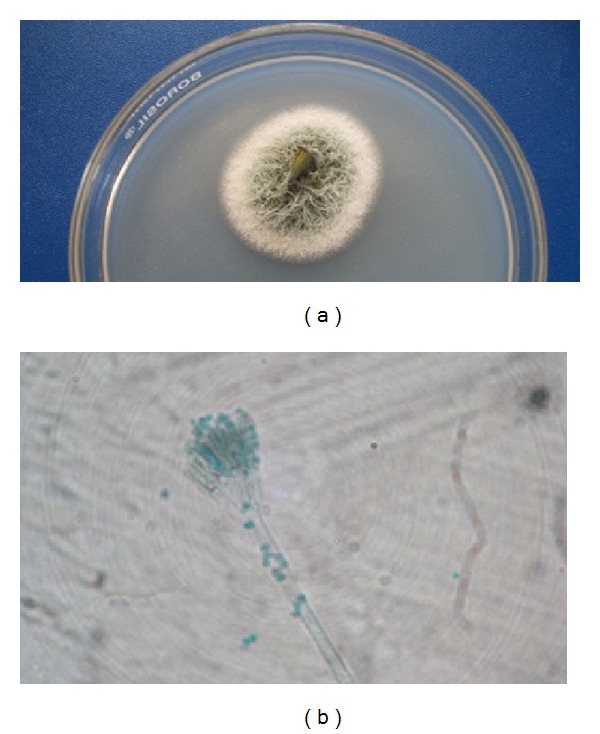

The surface sterilized leaf segments of C. longa (turmeric) were placed on PDA medium and incubated for 72 h. The fungi grown out from tissue were brought into pure culture, identified by microscopic observation and morphological characteristic features. Studies revealed that the fungus is Penicillium sp. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Endophytic fungi grown from sterilized leaf segment of Curcuma longa on PDA. (b) Microscopic image of endophytic fungi, Penicillium sp.

3.2. Extracellular Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles

Fungal filtrate was treated with equal volume of 1 mM AgNO3 solution after 24 h incubation; appearance of color change from pale white to brown is a clear indication for the formation of silver nanoparticles in the reaction mixture. The intensity of the color was increased with the period of incubation Figure 2. The appearance of the brown color was due to the excitation of surface plasmon vibrations [25].

Figure 2.

Color change to reddish brown after treating filtrate of endophytic fungi, Penicillium sp., with 1 mM AgNO3.

3.3. Optimization Studies for Silver Nanoparticles Production

Environmental conditions profoundly modulate the growth and metabolism of fungi. Culture conditions have been the critical components, directly affecting the productivity and also the process economics. Optimization of physical parameters will not only support good growth but also enhance the product yield [26]. The growth conditions, such as substrate concentration, pH, temperature, and inoculum size, directly monitor the rate of enzyme activity which reflects the synthesis of AgNps.

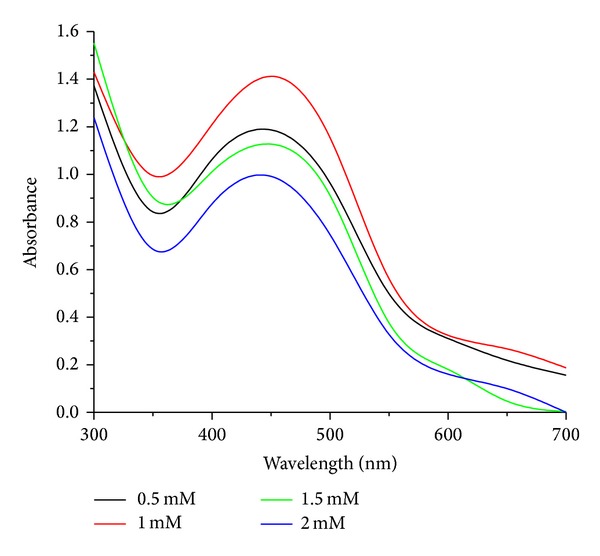

3.3.1. Effect of AgNO3 Concentration

Biosynthesis of AgNps with different concentrations of silver nitrate solution 0.5 mM to 2 mM was studied with the fungal filtrate. The optimum substrate concentration was predicted as 1 mM by color change and by UV-visible spectra at the maximum absorbance peak of 425 nm Figure 3. When the AgNO3 concentration increased to 2 mM the particle size may increase due to the aggregation of large silver nanoparticles [27]. Our results correlate with Banu et al., [25] who used 1.0 mM AgNO3 for the production of AgNps using the fungus Rhizopus stolonifer.

Figure 3.

UV-visible absorption spectra of AgNps at different concentrations of AgNO3.

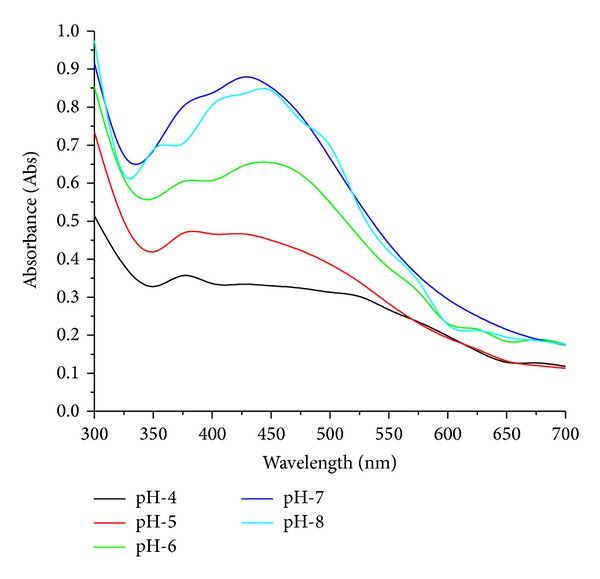

3.3.2. Effect of pH

Biosynthesis of AgNps due to the effect of varying different pH's from 4 to 8 by endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. is depicted in Figure 4 by UV-visible absorption spectra. The maximum peak at pH-7.0 is about 425 nm which indicates the presence of nanoparticle with a size range between 10 and 100 nm. On the contrary decrease in pH to 4.0 did not show any peak. At low pH, protein structure gets affected and the protein gets denatured and loses its activity; thus, aggregation of nanoparticles is observed [28]. It can be concluded that protein secreted by Penicillum sp. in the solution for the capping of AgNps is stable at pH-7.0 but not at acidic pH which can be attributed to the stability of capping proteins. Our results correlate with Banu et al. [25, 28], which shows maximum absorbance peak at 422 nm at pH-7.0 and with Jain et al. [29], using A. flavus at pH-7.0.

Figure 4.

UV-visible absorption spectra of biosynthesized AgNps at different at pH.

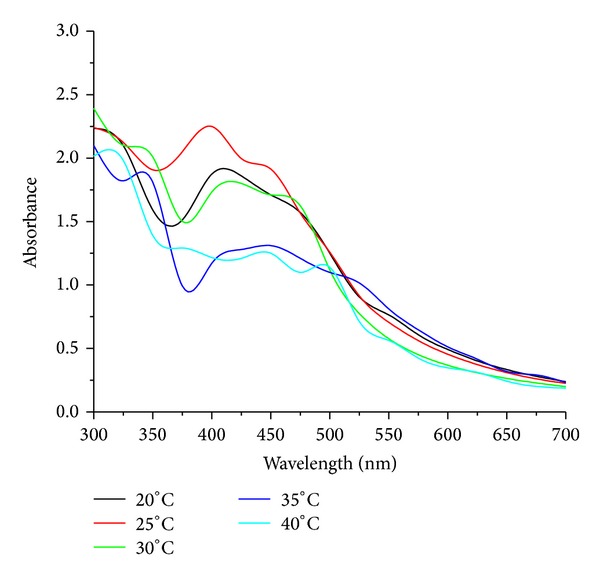

3.3.3. Effect of Temperature

Temperature is an essential factor affecting AgNps production. The effect of varying temperatures on AgNps production by endophytic fungi, Penicillium sp., is carried out at different temperatures from 25°C to 45°C with a difference of 5°C to know the phenomenon of silver ion reduction. The maximum production of AgNps was attended at 25°C by change in color within 12–14 h quicker when compared with other temperatures and also detected by UV-visible absorption spectra the maximum peak was at 390 nm which indicates the production of AgNps [16, 29]. On the other side at high temperature of 40°C, the enzyme activity gets low so the synthesis slows down for the AgNps in the reaction Figure 5.

Figure 5.

UV-visible absorption spectra of biosynthesized AgNps at different temperatures.

3.3.4. Effect of Biomass Concentration

Extracellular synthesis of AgNps was carried out by exposing 5 g to 20 g of wet biomass with the difference of 5 g of endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. in 1 mM of aqueous solution of AgNO3. UV-visible absorption spectra represent 15 and 20 g of wet biomass shows a maximum peak at 410 nm with no broadening or red shift of absorbance; the particles were well separated without any agglomeration, due the availability of enzymes which is sufficient for the production of nanosilver particles at pH-7 and temperature 25°C Figure 6. Our results correlate with the reports of Sunkar and Nachiyar [30] wherein they used endophytic fungi isolated by healthy leaf of Garcinia xanthochymus and Aravae lanata for the synthesis of AgNps.

Figure 6.

UV-visible absorption spectra of AgNps at different biomass concentrations.

3.4. Characterization Studies of Silver Nanoparticles

3.4.1. UV-Visible Spectroscopy

The extracellular synthesis of AgNps using endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. involves the bioreduction of silver ions in the filtrate. Reaction solution was monitored by periodic sampling of the reaction mixture at regular time intervals by using UV-visible spectroscopy. Synthesized AgNps showed maximum absorbance peak at 420 nm Figure 7. The AgNps formed were highly stable up to 120 h after the reaction. The AgNps were characterized and confirmed by TEM analysis. Similar results were observed by Ninganagouda et al., [24] who revealed plasma resonance of AgNps between 380 and 450 nm, and Sunkar and Nachiyar, who [31] revealed absorption peak at 400 nm and 423 nm by endophytic fungi isolated from leaf samples of Garcinia Xanthochymus and Aravae lanata.

Figure 7.

UV-visible absorption spectra of biosynthesized AgNps at different time intervals.

3.4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM measurements were carried out to determine the morphology and shape of AgNps. TEM micrograph Figure 8 revealed that the particle is spherical and well dispersed without agglomeration. The particle size of AgNps synthesized by endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. ranges from 25 to 30 nm. Various reports have provided evidence of extracellular synthesis of AgNps by TEM images. Ganachari et al. [32] reported well-distributed spherical shaped AgNps in the range of 5–30 nm by Penicillium diversum and Raheman et al. [33] also revealed spherical and polydispersive AgNps ranging from 10 to 40 nm by endophytic fungus Pestalotia sp. isolated from leaves of Syzygium cumini. (Banu et al. [25] revealed spherical shaped AgNps, with the size ranging between 3 and 20 nm by Rhizopus stolonifer.

Figure 8.

TEM image shows biosynthesized AgNps by endophytic fungi, Penicillium sp.

3.4.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR measurement of the dried and powdered sample was carried out to identify the possible interaction between silver and bioactive molecules, which may be responsible for synthesis and stabilization of AgNps. FTIR spectrum revealed the presence of eight bands at 1074, 1233, 1393, 1454, 1538, 1644, 2933, and 3290 cm−1 Figure 9. The bands at 1644, 1538, and 3290 cm−1 correspond to the binding vibrations of amide I and amide II band of protein, respectively, with N–H stretching's, while the 2923 cm−1 represents C–H stretching vibration. The bands observed at 1393, 1233, and 1074 cm−1 can be assigned to C–N stretching vibrations of aromatic and aliphatic amines, respectively. The observation revealed that the protein molecules not only act as reducing agent but also can act as stabilizing agent by binding to AgNps through free amino groups or cysteine residues or through electrostatic attraction of negatively charged carboxylate groups in extracellular enzyme filtrate from fungal mycelia [34].

Figure 9.

FTIR spectrum showing the presence of proteins as capping agents for AgNps synthesized by endophytic fungi, Penicillium sp. [20].

3.5. Analysis of Antibacterial Activity of AgNps against MDR E. coli and S. aureus Strains

3.5.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test

The antibiotic susceptibility test was performed by using different antibiotic discs for both E. coli and S. aureus. For E. coli strain antibiotic discs such as Amikacin (AK), Norfloxacin (NF), Pefloxacin (PF), Ciprofloxacin (CI), Cefuroxime Sodium (CR), Ofloxacin (OF), Nalidixic Acid (NA), Gentamicin (GM), Cefotaxime (CX), Ceftazidime (CZ), Ceftriaxone (FR), Cefixime (FX), Cefdinir (CN), and Nitrofurantoin (AT) were used, wherein only Amikacin (AK) showed sensitivity with zone of 15 mm and resistance for other antibiotics Figure 10(a). Discs of Ciprofloxacin (CI), Cefuroxime Sodium (CR), Ofloxacin (OF), Penicillin-G (PG), Amoxicillin (AX), Amoxicillin + Clavulanic (AC), Cotrimoxazole (CT), Cephalexin (CP), Cefazolin (CF), Erythromycin (ER), Chloramphenicol (CK), Piperacillin (PC), Azithromycin (AZ), and Tetracycline (TE) were used for S. aureus; surprisingly only Chloramphenicol (CK) showed sensitivity against S. aureus with zone of inhibition of 18 mm Figure 10(b).

Figure 10.

(A) Antibiotic susceptibility test of (a) E. coli and (b) S. aureus. (B) Antibacterial activity of AgNps synthesized by endophytic fungus Penicillium sp. against above confirmed MDR strains of (c) E. coli and (d) S. aureus.

3.5.2. Antibacterial Assay of Silver Nanoparticle against MDR E. coli and S. aureus

Antibacterial assay of biosynthesized AgNps was studied against MDR pathogenic strains (clinical isolates) of both E. coli and S. aureus using agar well diffusion method and zone of inhibition was depicted in Figure 10(B) and Table 1). AgNps solution was loaded into the wells with different concentrations of 20 μL, 40 μL, 60 μL, and 80 μL, respectively, against E. coli and S. aureus. The results revealed that AgNps were most effective against MDR E. coli. It was 17 mm at 80 μL concentration. For MDR S. aureus, however, AgNps showed a mild growth inhibitory effect of 16 mm even at high concentration of 80 μL when compared to MDR E. coli strain. Similar effects on E. coli and S. aureus pathogenic strains were observed by Kim et al., [35] and also Ninganagouda et al. [24] reported good antibacterial activity against E. coli using AgNps synthesized by Aspergillus flavus. Due to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics microorganisms have developed resistance against many antibiotics, and thus MDR strains have cropped up. A good alternative source which is ecofriendly and cost effective is only through AgNps because of their inhibitory and bactericidal effects.

Table 1.

Zone of inhibition of AgNps produced by the endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. against MDR E. coli and S. aureus.

| S. no | MDR bacterial strains | Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 µL | 40 µL | 60 µL | 80 µL | ||

| 1 | Escherichia coli | 14 mm | 15 mm | 16 mm | 17 mm |

| 2 | Staphylococcus aureus | 12 mm | 15 mm | 15 mm | 16 mm |

4. Conclusion

Development of resistance to human pathogens is a challenge in field of pharmaceuticals and biomedicine. Antibiotic resistance profiles lead to fear about the emergence and reemergence of MDR pathogens. Development or modification in antimicrobial compounds to improve bactericidal potential is an area of priority in this modern era. Nanotechnology provides a good platform to modify and develop nanostructures having promising applications in various fields. Therefore, an endophytic fungus, Penicillium sp., isolated from healthy leaves of Curcuma longa (turmeric) was found to be a good producer of AgNps which remained untouched for nanoparticles production apart from being rich sources of secondary metabolites. These AgNps were proved to be powerful weapons against the MDR E. coil and S. aureus in a facial way.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. The American Journal of Medicine. 2006;119(6):S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb GF, D’Agata EMC, Magal P, Ruan S. A model of antibiotic-resistant bacterial epidemics in hospitals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(37):13343–13348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504053102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lara HH, Ayala-Núñez NV, Turrent LCI, Padilla CR. Bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;26(4):615–621. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht MA, Evans CW, Raston CL. Green chemistry and the health implications of nanoparticles. Green Chemistry. 2006;8(5):417–432. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor clusters, nanocrystals, and quantum dots. Science. 1996;271(5251):933–937. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coe S, Woo WK, Bawendi M, Bulović V. Electroluminescence from single monolayers of nanocrystals in molecular organic devices. Nature. 2002;420(6917):800–803. doi: 10.1038/nature01217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruchez M, Jr., Moronne M, Gin P, Weiss S, Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor nanocrystals as fluorescent biological labels. Science. 1998;281(5385):2013–2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rai M, Yadav A, Gade A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnology Advances. 2009;27(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schabes-Retchkiman PS, Canizal G, Herrera-Becerra R, Zorrilla C, Liu HB, Ascencio JA. Biosynthesis and characterization of Ti/Ni bimetallic nanoparticles. Optical Materials. 2006;29(1):95–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu H, Ho PL, Tong E, Wang L, Xu B. Presenting vancomycin on nanoparticles to enhance antimicrobial activities. Nano Letters. 2003;3(9):1261–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmad Z, Pandey R, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Alginate nanoparticles as antituberculosis drug carriers: formulation development, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic potential. The Indian Journal of Chest Diseases & Allied Sciences. 2006;48(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong P, Li H, He X, et al. Preparation and antibacterial activity of Fe3O4@Ag nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(28):604–611.285604 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gemmell CG, Edwards DI, Fraise AP, Gould FK, Ridgway GL, Warren RE. Guidelines for the prophylaxis and treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the UK. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;57(4):589–608. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chopra I. The increasing use of silver-based products as antimicrobial agents: a useful development or a cause for concern? Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2007;59(4):587–590. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingle A, Gade A, Pierrat S, Sönnichsen C, Rai M. Mycosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using the fungus Fusarium acuminatum and its activity against some human pathogenic bacteria. Current Nanoscience. 2008;4(2):141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, et al. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their immobilization in the mycelial matrix: a novel biological approach to nanoparticle synthesis. Nano Letters. 2001;1(10):515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minaeian S, Shahverdi AR, Nohi AS, Shahverdi HR. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by somebacteria. Journal of Science IAU. 2008;17(66):66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacon CW, Hinton DM, Porter JK, Glenn AE, Kuldau G. Fusaric acid, a Fusarium verticillioides metabolite, antagonistic to the endophytic biocontrol bacterium Bacillus mojavensis . Canadian Journal of Botany. 2004;82(7):878–885. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strobel G, Yang X, Sears J, Kramer R, Sidhu RS, Hess WM. Taxol from Pestalotiopsis microspora, an endophytic fungus of Taxus wallachiana . Microbiology. 1996;142(2):435–440. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-2-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh D, Rathod V, Ninganagouda S, Herimath J, Kulkarni P. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticle by endophytic fungi Penicillium sp. isolated from Curcuma longa (turmeric) and its antibacterial activity against pathogenic gram negative bacteria. Journal of Pharmacy Research. 2013;7(5):448–453. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karbasian M, Atyabi SM, Siadat SD, Momen SB, Norouzian D. Optimizing nano-silver formation by Fusarium oxysporum PTCC 5115 employing response surface methodology. The American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science. 2008;3(1):433–437. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lekha PK, Lonsane BK. Production and application of tannin acyl hydrolsase: state of the art. Advances in Applied Microbiology. 1997;44(27):215–260. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell SC, Grundy WE. Preparation of agar wells for antibiotic assay. Applied Microbiology. 1968;16(10):1611–1612. doi: 10.1128/am.16.10.1611-1612.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ninganagouda S, Rathod V, Jyoti H, Singh D, Prema K, Manzoor-Ul-Haq Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus flavus and their antimicrobial activity against gram negative MDR strains. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences. 2013;4(2):222–229. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banu A, Rathod V, Ranganath E. Silver nanoparticle production by Rhizopus stolonifer and its antibacterial activity against extended spectrum β-lactamase producing (ESBL) strains of Enterobacteriaceae. Materials Research Bulletin. 2011;46(9):1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Greasham R. Chemically defined media for commercial fermentations. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1999;51(4):407–421. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rao CRK, Trivedi DC. Synthesis and characterization of fatty acids passivated silver nanoparticles—their interaction with PPy. Synthetic Metals. 2005;155(2):324–327. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banu A, Rathod V. Synthesis and chacterzation of silver nanoparticles by Rhizopus stolonifer . International Journal of Biomedical and Advance Research. 2011;2(5):148–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain N, Bhargava A, Majumdar S, Tarafdar JC, Panwar J. Extracellular biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Aspergillus flavus NJP08: a mechanism perspective. Nanoscale. 2011;3(2):635–641. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00656d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunkar S, Nachiyar CV. Endophytic fungi mediated extracellular silver nanoparticles as effective antibacterial agents. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Science. 2013;5(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunkar S, Nachiyar CV. Biogenesis of antibacterial silver nanoparticles using the endophytic bacterium Bacillus cereus isolated from Garcinia xanthochymus . Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2(12):953–959. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ganachari SV, Bhat R, Deshpande R, Venkataraman A. Extracellular biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using fungi Penicillium diversum and their antimicrobial activity studies. BioNanoScience. 2012;2(4):316–321. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raheman F, Deshmukh S, Ingle A, Gade A, Rai M. Silver nanoparticles: novel antimicrobial agent synthesized from an endophytic fungus Pestalotia sp. isolated from leaves of Syzygium cumini (L) Nano Biomedicine and Engineering. 2011;3(3):174–178. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gole A, Dash C, Ramakrishnan V, et al. Pepsin-gold colloid conjugates: preparation, characterization, and enzymatic activity. Langmuir. 2001;17(5):1674–1679. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim JS, Kuk E, Yu KN, et al. Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;3(1):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]