Do you know your patient? More than 20 years ago Dr. Afaf Meleis wrote about the importance of knowing your patient and the unique opportunity for nurses to use this knowledge to improve care (Schumacher, Jones, & Meleis, 1999). “Knowing your patient” can mean different things to different nurses depending on how you define knowing and where one practices. In this editorial, we present one practical case exemplar and evidence to support this approach.

A couple of months ago, the authors participated in nursing rounds on Mr. E., a 77-year-old man who was retired with a PhD degree in psychology. He had a diagnosis of dementia and was admitted with a gastrointestinal illness and dehydration. He and his wife had recently moved to the area to be closer to their children. Because the nurses in this hospital were part of an ongoing study (see http://clinicaltrials.gov, trial NCT01505257), they had access to a tool to detect delirium called the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM, Inouye et al., 1990) embedded in the hospital electronic medical record and were assessing his mental status every shift. They had even reviewed his chart to avoid medications that might cause him to get delirium on top of his dementia (Fick & Resnick, 2012). However, Mr. E. would often appear restless and try to get out of bed unassisted, even though he was still quite unsteady due to weakness from his gastrointestinal illness. Like many hospitals, this hospital encouraged fall prevention strategies. Although the nursing staff was getting Mr. E. up in a chair every day, they also implemented a pad that would sound an alarm every time he stepped on it, and then he would be put promptly back into bed.

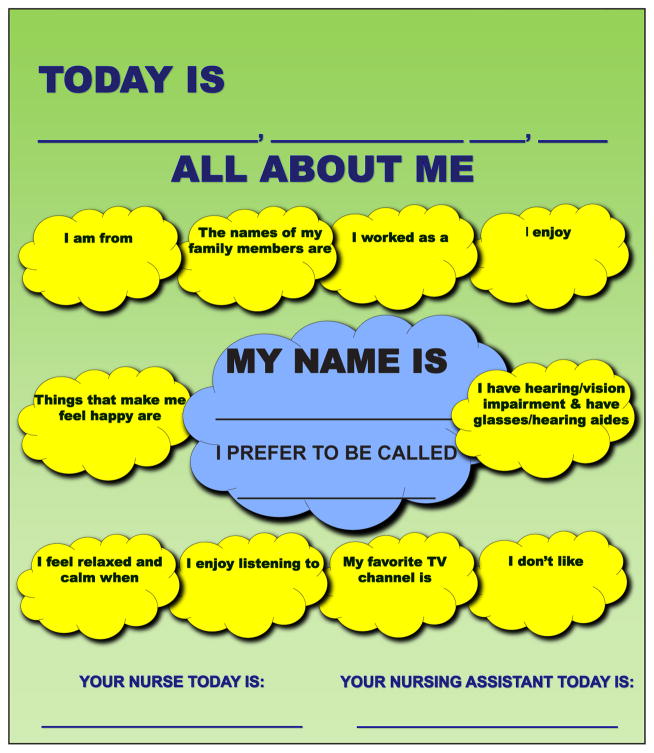

While doing our rounds, we introduced the “All About Me Board” to Mr. E., which helped initiate a conversation with him and his wife and subsequently helped us know him better and implement a nursing intervention to address his care needs. The All About Me Board, which was developed by the direct care nurses in consultation with the gerontological clinical nurse specialist and nurse practitioner, contains information including what older adults prefer to be called, their favorite music, what makes them feel calm, their past occupation, hobbies, and the names of family members and pets. Because the board is in the room and highly visible, staff do not need to search through the chart for this key information and it is available in the middle of the night if the older adult with dementia or delirium becomes restless or agitated.

Mr. E. had a Mini-Mental State Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of 17 of 30 and scored negative for delirium on the CAM. He had some problems with comprehension but was still able to have a conversation with the nurses about his likes and dislikes. While filling out the board we found out that his favorite thing to do every day was to take a 3-mile walk around his neighborhood with his wife. We discovered he loved classical music, sports, outdoor activities, and had a cat. This information, including his prior activity level, was placed on the All About Me Board that hung in his room. After the nurses knew how much he had been walking at home they implemented a schedule where he would take progressively longer walks in the hallway with staff and a family member. The nursing staff reported that his restlessness decreased and the caregiver reported high satisfaction with use of the board.

The board (Figure) is colorful, large, easily designed on the computer, and is laminated so it can be wiped down with disinfectant and reused. The board can be adapted to the setting and produced for a minimal cost. Although many hospitals have orienting white boards with the date and name of the nurse caring for the patient that shift, we found that most older adults cannot even see the boards (sometimes they are behind the patient), and the information is not very helpful to their care.

Figure.

The All About Me Board, which was developed by the authors, contains key information about the patient.

This type of approach helps us personalize interventions for individuals with dementia and helps us know our patient (Schumacher et al., 1999). This is supported by work that illustrated the importance of individualizing care to increase the impact of your intervention (Kolanowski, Litaker, & Buettner, 2005; Kolanowski & Whall, 1996; Penrod et al., 2007). In addition, the board is congruent with Kitwood’s (1997) framework of personhood and person-centered nursing care. This allowed the nursing staff to know the person first, rather than the disease. By getting to know a little bit about Mr. E.’s life story and things he enjoys doing, nursing care is personalized and tailored to his needs. Importantly, this intervention helped us address Mr. E.’s restlessness, increased his activity level, and possibly avoided delirium and a decrease in his function.

A recent small study from 19 residents found that using a person-centered care approach with nursing assistants improved both resident and nursing assistant perceptions of closeness and satisfaction (Penrod et al., 2007; Van Haitsma et al., 2013). Many aspects of hospitalization are not conducive to maintaining function and activity and lead to hospital-acquired functional decline (Creditor, 1993). On the other hand, the benefits of physical activity and exercise in older adults are well known, and the evidence for the cognitive benefits of exercise is growing (Boltz, Resnick, Capezuti, Shuluk, & Secic, 2012; Gates, Singh, Sachdev, & Valenzuela, 2013; Ruthirakuhan et al., 2012). A number of studies have tested models to promote function in older adults across settings of care (Boltz et al., 2012).

Nurses need to consider and plan for the elements of the hospital environment that encourage activity and those that impede it; including an overly zealous desire to prevent falls and the unintended consequences this can have for older adults. Mr. E. and the use of the All About Me Board is just one example of how to get to know your patients and maintain their function and activity level while hospitalized. Can you think of others?

Acknowledgments

Dr. Fick acknowledges funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research Early Nurse Detection of Delirium Superimposed on Dementia (END-DSD) (grant 5 R01 NR011042 03), as well as nursing staff and nursing leadership at Mount Nittany Health System for support of this project and delirium rounds.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Donna M. Fick, Journal of Gerontological Nursing, Professor of Nursing, School of Nursing, Professor of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Brittney DiMeglio, Adult/Gerontology Nurse Practitioner Student.

Jane A. McDowell, Project Director, School of Nursing, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

Jeanne Mathis-Halpin, Clinical Supervisor, Mount Nittany Health System State College, Pennsylvania.

References

- Boltz M, Resnick B, Capezuti E, Shuluk J, Secic M. Functional decline in hospitalized older adults: Can nursing make a difference? Geriatric Nursing. 2012;33:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creditor M. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1993;118:219–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fick DM, Resnick B. 2012 Beers criteria update: How should practicing nurses use the criteria? Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2012;38(6):3–5. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20120517-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates N, Singh MF, Sachdev P, Valenzuela M. The effect of exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;S1064–7481(13):00165–00166. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1990;113:941–948. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-12-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood TM. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM, Litaker M, Buettner L. Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nursing Research. 2005;54:219–228. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski AM, Whall AL. Life-span perspective of personality in dementia. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1996;28:315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1996.tb00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Yu F, Kolanowski A, Fick DM, Loeb SJ, Hupcey JE. Reframing person-centered nursing care for persons with dementia. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice. 2007;21:57–72. doi: 10.1891/rtnpij-v21i1a007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthirakuhan M, Luedke A, Tam A, Goel A, Kurji A, Garcia A. Use of physical and intellectual activities and socialization in the management of cognitive decline of aging and in dementia: A review (Article 384875) Journal of Aging Research. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/384875. Retrieved from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jar/2012/384875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schumacher KL, Jones PS, Meleis AI. Helping elderly persons in transition: A framework for research and practice. In: Swanson EA, Tripp-Reimer T, editors. Life transitions in the older adult: Issues for nurses and other health professionals. New York: Springer; 1999. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haitsma K, Curyto K, Spector A, Towsley G, Kleban M, Carpenter B, Koren MJ. The Preferences for Everyday Living Inventory: Scale development and description of psychosocial preferences responses in community-dwelling elders. The Gerontologist. 2013;53:582–595. doi: 10.1093/geront/gns102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]