Abstract

Objective

Despite numerous studies on parental involvement in children’s academic schooling, there is a dearth of knowledge on how parents respond specifically to inadequate academic performance. This study examines whether 1) racial differences exist in parenting philosophy for addressing inadequate achievement, 2) social class has implications for parenting philosophy, and 3) parents’ philosophies are consequential for children’s academic achievement.

Methods

Using data from the Child Development Supplement (N=1041) to the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, we sort parents into two categories—those whose parenting repertoires for addressing poor achievement include punitive responses and those whose repertoires do not. We then determine whether racial differences exist between these categories and how various responses within the aforementioned categories are related to students’ academic achievement.

Results

The findings show that white and black parents have markedly different philosophies on how to respond to inadequate performance, and these differences appear to impact children’s achievement in dramatically different ways.

Conclusion

Educators and policy makers should pay particular attention to how parents respond to inadequate achievement as imploring parents of inadequately performing students to be more involved without providing them with some guidance might exacerbate the problem.

INTRODUCTION

Parents play a primary role in the academic achievement of their children (e.g., Sui-Chu and Willms 1996; Muller 1995, 1998; Crosnoe 2001). Additionally, their involvement in children’s schooling affairs predicts numerous other schooling outcomes including truancy and school dropout (e.g., Domina 2005; McNeal 1999). While cumulative evidence supports the theoretical link between parents and academic performance (Dornbusch et al. 1987; Stevenson and Baker 1987; Ingram, Wolfe, and Lieberman 2007; Amato and Fowler 2002), previous research provides virtually no insight into how parents deal with inadequate academic performance in particular. That is, most research on parenting and achievement examine parental involvement in general; there is a dearth of research on how parents deal specifically with inadequate achievement and the implications that their approach in addressing the problem has for their children’s academic outcomes.

Asking parents to be involved in their children’s schooling is conceptually and empirically distinct from asking them to address inadequate academic performance. Whereas the former condition for involvement is intended to help a child improve or maintain their current level of academic engagement and performance, the latter requires that parents address a problem. The consideration of a “problem” introduces some level of urgency, which might lead to a shift in philosophy in how a parent approaches the situation. Thus, parenting under this scenario might trigger responses from parents that they otherwise would not employ absent the need to “fix” a problem. An examination of how parents deal with inadequate achievement is especially important since informing parents of effective strategies to improve children’s achievement is the concern of virtually every school administration in the country facing increasing pressure to close the racial achievement gap. While schools can enact strategies to handle inadequate performance such as recruiting and training high-quality teachers, or strengthening the quality of program-instruction, it is less clear what responses parents should employ to improve their children’s achievement.

It is also important to assess the link between parents’ philosophy for dealing with inadequate academic performance and children’s achievement for groups who typically perform inadequately in school. The importance of this link becomes apparent when one considers the magnitude of racial differences in achievement. Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)—created to regularly test nationally representative samples of students in grades 4, 8 and 12 (or sometimes ages 9, 13, 17)—shows that black 12th graders score lower than white 8th graders in reading, math, U.S. history, and geography. Hedges and Nowell (1999) concluded that the pace at which mean group differences in test scores decreased during the last 30 years of the 20th century suggests gap convergence would take 30 years in reading and about 75 years in math. They also concluded gap convergence on non-NAEP surveys would take over 50 years in reading and more than a century in math.

Given the increasing urgency for closing the racial achievement gap, it is surprising that few empirical studies have focused on racial differences in how parents are oriented toward dealing with their child’s inadequate academic performance, and whether achievement differences exist between the various strategies parents are inclined to employ. Examining this link could yield strategies useful for educators and parents of youths from traditionally under-performing groups. Previous studies give reason to expect racial variation in the strategies parents are inclined to employ in response to inadequate performance. In their study of cultural variations in parenting among two-parent families, Julian, McKenry, and McKelvey (1994) find that ethnic parents (e.g., blacks, Asians, and Hispanics) place greater emphasis on their children’s academic success than white parents. However, they also find that ethnic parents express greater strictness and control over their children. Thus, while whites and blacks may want their children to do better academically, black parents may feel a disciplinary approach is the most effective strategy for dealing with poor achievement. The black achievement disadvantage also means that a greater share of black parents operate in “crisis” mode rather than “maintenance” mode when it comes to their children’s education. Therefore, it is important to determine parents’ preferred strategy for addressing their children’s poor achievement.

We take up this issue in this study by answering three questions. First, do racial differences exist in parenting philosophy for addressing inadequate achievement? Second, given the importance social class can have on both parenting and achievement, does social class have implications for the strategies parents believe are more effective for dealing with inadequate achievement? Finally, is parents’ philosophy for dealing with inadequate achievement consequential for children’s academic achievement? Since our concern here is with youth from traditionally under-performing groups, we focus on blacks relative to whites. Also, we consider both parents’ penchant for responding in a particular way when their child’s achievement does not meet expectations as well as their actual responses to poor performance. Below we begin with a brief discussion of why we expect group differences in parental responses to poor performance. We then proceed to answer each of these questions in turn, and conclude with a summary of the findings and a discussion of the theoretical and policy implications of this study.

Race and Parenting Philosophy

Historically, the literature on parenting styles by race have attributed drastically different parenting styles to white and black parents. For example, white parents are posited to use inductive reasoning with their children, allow choices for the children, encourage their children to be independent, solve problems on their own, and be active explorers of the environment (McGroder 2000). In contrast, for much of the 20th century scholars posited that black families operated under a social deficit model of childrearing. Black parents have been characterized as expressing low levels of reasoning, intolerant of child self-expression, and as having high levels of power assertion (Baumrind 1972). In fact, there is a long history of characterizing the black family as consisting of mothers who are harsh and capricious and fathers who are aloof, violent, and uninterested in child affairs (Kardiner and Ovesey 1951).

Although parenting styles have been attributed to social class (Lareau 2003; Middlemiss 2003), some studies show that there are racial differences in parenting net of social class. For example, in a study across various social class strata, Hill and Sprague (1999) find that whereas white parents are more likely to emphasize children’s happiness and self-esteem, blacks place more emphasis on obedience and school performance. They also find that blacks are more likely to report that being a disciplinarian is a major part of their role as parents. Even among their upper middle class subsample, they find that white parents are more likely to use reason and black parents are more likely to withdraw privileges. Some studies suggest that the disciplinary practices of black parents are more severe, punitive, and power assertive than white parents net of socioeconomic background (Allen 1985; Portes et al. 1986).

Parenting styles for blacks might be a direct result of their experiences as a subordinate group within the U.S. Because blacks have been subjected to longstanding discrimination, they have developed “adaptive strategies” particular to their position within larger society (Harrison et al. 1990). This is consistent with the family ecology perspective, which proposes that white and black families have developed different strategies of childrearing resulting from their respective experiences of living in the U.S. Hill (2001) notes that black parents might feel a greater need to adopt forceful parenting styles in response to structural forces that undermine their childrearing efforts. Similarly, Gonzales et al. (1998) note that black mothers tend to employ a parenting style that sets clear and firm rules and reinforce their role as authority figures. The use of power-assertive discipline is posited to partially stem from parents’ attempts to teach functional competences (e.g., self-reliance and mistrust of authority figures) needed to survive in environments marked by marginal conventional economic resources and a robust under-ground economy (Ogbu, 1981). Thus, racial differences in parenting may be partly due to inequality in material resources (e.g., wealth) and environmental support. Blacks’ disadvantage on these factors contributes to their higher levels of psychological distress, which is associated with a more punitive parenting style (McCLoyd 1990).

It is important to note that black parents have greater educational expectations for their children than whites (Harris 2011). In fact, a national poll commissioned by the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education found that black parents place higher value on obtaining an education as a means for advancement than whites (Public Agenda 2000). Working class black parents are more likely to discuss their children’s school experiences and plans, restrict television on school nights, set rules about grades, and help with homework than their white counterparts (U.S. Department of Education 1992). Given black parents’ greater educational expectations, and that they are more likely than whites to anticipate that their children will experience discrimination (Harris 2011), it is reasonable to expect that they will differ from white parents in their approach to dealing with poor academic performance. Since high socioeconomic status often fails to protect against racial discrimination (Cose 1993; Feagin and Sikes 1994; Hochschild 1995), we expect racial difference to exist even after accounting for socioeconomic background. Below we determine whether racial differences exist in parents’ philosophy for addressing low achievement.

Question 1: Do Racial Differences Exist in Parenting Philosophy?

We examine whether differences exist between black and white parents in their preferred approach for dealing with their child’s poor school achievement using data from the Child Development Supplement (CDS) of the Panel Study for Income Dynamics (PSID). The PSID began in 1968 as a nationally representative sample of 5,000 American families who were interviewed every year until 1997, after which data collection occurred biannually. Data collection includes members from the original families and families formed by children of initial sample members. In 1997, the PSID added the CDS to address the lack of information on children. Thus, the objective of the CDS was to provide a nationally representative longitudinal database of children and their families to support studies on the dynamic process of early human capital development. The CDS is especially suited to examine the link between parental responses on children’s future achievement as it collects test information over two waves which span a total of 6 years.

The CDS contains three waves of data. The first wave (CDS-I) contains 3563 children between the ages of 0–12 sampled from PSID families in 1997. The first follow-up wave (CDS-II) was conducted in 2002–2003 among 2908 children whose families remained active in the PSID panel. The children were then between the ages of 5 and 18. A third wave of data was collected in 2007, when youth were approximately ages 9–22. To ensure that all children in the sample were in school during the first two waves of the CDS, we restrict our sample to children in grades 7–12 in CDS-II (N = 1041). Due to the limited sample on immigrant families and other ethnic groups, we further restrict our analyses to whites (n = 549) and blacks (n = 492). We employ a weighting system devised by the PSID staff to account for the effects of the initial probability of being sampled and attrition over time—which is generally low—and incorporates a post-stratification factor to ensure the data are nationally representative (see http://psidonline.isr.umich.edu/CDS/weightsdoc.html for a detailed description of the CDS weight construction).

We gauge parenting philosophy from the first wave of the CDS, which asked parents how they would respond “if their child brought home a report card with grades or progress that was lower than expected.” We sorted parents into two mutually exclusive categories—a punitive response, and a non-punitive response (see Table 1 for a detailed description of measures). Within the punitive group, which comprised 36 percent of the sample, parents were further sorted into whether their punitive approach was mild (those who punish or limit their child’s activities) or acute (those who both punish and limit activities).

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Descriptions for Variables used in this Study

| Variable | Description | Metric | Means (SD) | Data | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites | Blacks | ||||

| Educational Outcomes (CDS-II): Each of the following subscales are from the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Test | |||||

| Reading | Summation of the Letter-Word and Passage Comprehension scores. | 0 – 193 | 108.98 (18.79) | 93.29 (17.48) | CDS-II |

| Math | Summation of the Calculation and Applied Problems scores. | 49 – 171 | 108.51 (15.28) | 95.23 (13.74) | CDS-II |

| Parents’ Philosophy toward Inadequate Performance | |||||

| If (child) brought home a report card with grades or progress lower than expected, would you be likely to: | |||||

| Punitive | |||||

| Mild | Punish or limit or reduce (child’s) non-school activities. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.27 | .39 | CDS-I |

| Acute | Both punish and limit (child’s) non-school activities. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.02 | .23 | CDS-I |

| Non-Punitive | |||||

| Contact | Contact (child’s) teacher or principal. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.10 | .05 | CDS-I |

| Help | Spend more time helping (child) with homework. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.18 | .13 | CDS-I |

| Contact & Help | Both contact and help. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.33 | .12 | CDS-I |

| Monitor/Encourage | Keep a close eye on (child’s) activities and/or tell child to spend more time on schoolwork. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.06 | .04 | CDS-I |

| Other | None of the above responses. | 0 = Not very likely 1 = Very likely |

.04 | .04 | CDS-I |

| Parents’ Response to Inadequate Performance | |||||

| When (child) did poorly in school, how often did you do the following things?: | |||||

| Threat | Threaten to physically punish or spank child? | 0 = ~Frequently or Always 1 = Frequently or Always |

.06 | .27 | MADICS |

| Take Privilege | Take privileges away from child? | 0 = ~Frequently or Always 1 = Frequently or Always |

.31 | .57 | MADICS |

| Ground | Ground child? | 0 = ~Frequently or Always 1 = Frequently or Always |

.20 | .50 | MADICS |

| Yell | Yell at child? | 0 = ~Frequently or Always 1 = Frequently or Always |

.18 | .31 | MADICS |

| Physically Punish | Physically punish or spank child? | 0 = ~Frequently or Always 1 = Frequently or Always |

.01 | .10 | MADICS |

| Background Factors | |||||

| Parents’. Education | Highest level of education by either parent, measured in years of education. | 0 – 17, (17 > 4yr degree) | 13.84 (2.31) | 12.39 (2.64) | CDS-I |

| Household Income | Total household income (x10,000). | $0 – $500 or > | 6.73 (5.69) | 2.89 (2.45) | CDS-I |

| Family Structure | Two-parent household. | 0 = Not two-parent 1 = Two-parent |

.86 | .41 | CDS-I |

| Prior Reading | Summation of the Letter-Word and Passage Comprehension scores. | 42 – 163 | 112.25 (15.70) | 99.21 (14.52) | CDS-I |

| Prior Math | Summation of the Calculation and Applied Problems scores. | 33 – 184 | 112.26 (17.54) | 101.13 (14.79) | CDS-I |

The remaining portion of the sample (64%) consisted of parents who generally do not opt for a punitive approach, and were therefore considered non-punitive responders. We sorted this group into four categories; those who 1) contact faculty but do not help their child more, 2) help their child more but do not contact faculty, 3) simultaneously contact faculty and help their child more, and 4) engage in closer monitoring and/or encouragement. These four categories contained 9, 17, 29, and 6 percent of the sample, respectively (the final 3% did not fall into any of these categories and were labeled as other). While parents in the punitive group could also employ non-punitive responses, the key distinction between these groups is that punitive approaches are within their parenting repertoire, which was not the case for parents in the non-punitive groups. The responses were obtained directly from children’s primary caregiver. Approximately 95 percent of these respondent’s were mothers (either biological/step/or adopted). Very small percentages of fathers (biological, step, and adopted - 2.7%), legal guardians (1.2%), and other household adults (0.4%) were the main respondents.

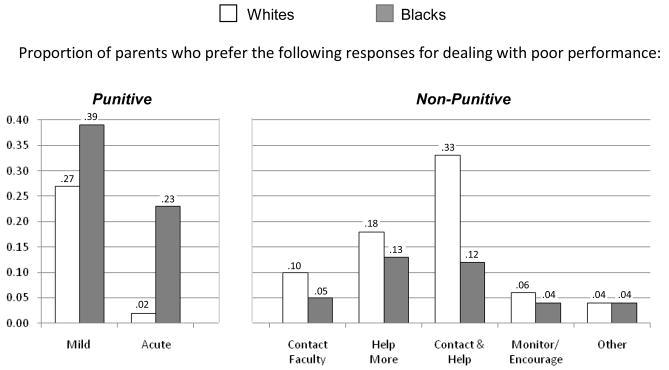

We show how white and black parents sort into these categories in Figure 1. The figure shows that black parents express a greater preference for punitive responses to address inadequate academic performance than white parents; less than one-third of whites were in the punitive group (29%) compared to nearly two-thirds for blacks (62%). A greater proportion of blacks fell into the mild (.39) and acute (.23) categories relative to whites (.27 and .02, respectively). Alternatively, this means that more than two-thirds of white parents were in the non-punitive response group (71%) compared to roughly over one-third (38%) of black parents. Whites held a substantial advantage over blacks in the proportion of parents who sorted into the first three non-punitive categories. It seems that white parents’ preferred strategy for addressing inadequate performance is to contact school officials in conjunction with providing their child with more help. These findings suggest that whites and blacks differ dramatically in their inclinations for dealing with their child’s inadequate achievement.

Figure 1. Parents’ Preferred Strategy for and Dealing with Poor Academic Performance: CDS.

Note: Findings are unadjusted. All racial differences are significant at the .05 level with the exception of Monitor/Encourage and other. Unweighted N= 1041.

Although the findings in figure 1 show substantial racial variation in how parents are inclined to respond to inadequate performance, a major critique that could be raised is that we are capturing a hypothetical rather than an actual response. However, we view this as an inclusive measure of parents’ behavioral inclination toward academic underperformance. In this case, parents who respond harshly to underperformance might be displaying consistent behavior with how they raise their child(ren) generally. If our question asked, “how did you respond when your child brought home…lower than expected,” we would be capturing a parents’ response to a specific instance. This response could be indicative of how parents typically respond, but it could also be reflective of a behavioral “shock” a parent experienced when an unusually stressful moment occurred concomitantly with their child’s underperformance, for example marital turmoil or loss of employment. A major strength of the measure we use is that it asks parents about a situation that would elicit a response under normal circumstances. Moreover, we recognize that for some parents inadequate performance can occur if their child scores lower on a test than usual; this circumstance can compel some parents to respond in ways they feel are appropriate. Thus, in addition to capturing students who are not doing well in school, our measure captures those who might be doing well overall but are performing less well relative to their usual academic achievement, which may trigger a response from parents.

Despite the strength that we see in our measure, we understand that some readers might approach our findings with some trepidation. Furthermore, it is unclear what the punitive responses actually mean as they are less suggestive than the non-punitive categories. Therefore, we employ data from the Maryland Adolescent Development in Context Study (MADICS), which contains a unique collection of measures on 1,407 black and white families (66 and 34 percent, respectively) from a county on the Eastern seaboard of the United States. The sample was selected from approximately 5,000 adolescents in the county that entered middle school during 1991 via a stratified sampling procedure designed to get proportional representations of families from each of the county’s 23 middle schools. As such, students’ socioeconomic backgrounds are varied as the sample includes families from neighborhoods in low-income urban areas, middle class suburban areas, and rural farm-based areas. While the mean family income in the sample is normally distributed around $45,000–$49,000 (range $5,000–$75,000), white families report significantly higher incomes ($50,000–$54,999) than black families ($40,000–$44,999). The MADICS consists of five waves of data collected from both parents and youth from grade seven (n = 1407), eight (n = 1004), eleven (n = 954), one year post-high school (n = 832), and three years post-high school (n = 853). In supplemental analyses not shown, blacks were not less likely to be retained than whites; the proportion of blacks and whites within the sample remains constant across waves.

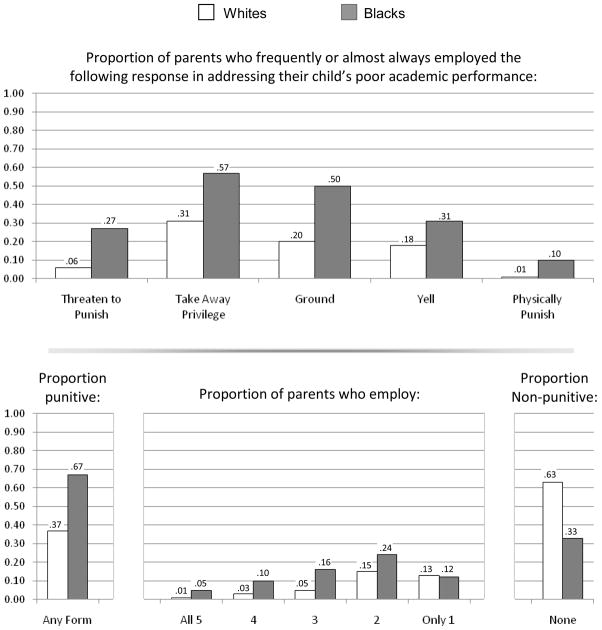

We supplement the findings from Figure 1 using the MADICS because despite being drawn from a regional sample, the MADICS contains a broader set of questions on punitive parenting responses to inadequate achievement than the CDS. Furthermore, parents were asked how they have actually responded in the past when their child performed poorly in school. Thus, the MADICS can provide some insight into whether the patterns observed in Figure 1 are robust. We display these findings in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Parents’ Response to Poor Academic Performance: MADICS.

Note: Findings are unadjusted. Findings are for youth in middle school (grade 8). All racial differences in the top panel are significant at the .05 level. In the bottom panel, racial differences are significant at the .05 level for any form, 3, and none. Finally, the racial differences for all 5, 4, and 2 in the bottom panel are marginally significant (p < .10). Number of observations ranges from 277 to 280.

The findings in the top panel of Figure 2 are consistent with those based on the CDS. Specifically, relative to whites, a greater proportion of black parents respond to their child’s inadequate academic performance by threatening to physically punish them, taking away their privileges, grounding them, yelling at them, and physically punishing them. Unlike for our analysis of the CDS, these options were not mutually exclusive. However, the bottom panel shows that the ratio of parents in the punitive group to those in the non-punitive groups is similar to the ratio observed in the CDS for both racial groups. The proportion of white parents who engage in punitive responses is .27, only .02 less than in the CDS. Similarly, 67 percent of blacks engage in punitive approaches, only 5 percent more than recorded using the CDS.

It seems rather clear that black parents have a penchant for employing punitive strategies for addressing their child’s inadequate academic performance. It is important to note that parenting styles are ways of socializing children to accomplish childrearing goals of a particular group. Also, the extent to which some parenting approaches are considered to be undesirable varies across families. For example, many black parents who employ physical punishment do not regard it as abuse (Mosby et al 1999). In fact, Deater-Deckard and colleagues (1995) found that among black parents in their sample, physical punishment was positively associated with warmth and use of reason. Although discipline is more harsh and physical among black families, it is rarely coupled with withdrawal of love, as is often the case among white families (Borkowski, Ramey, and Bristol-Power 2009). In general, researchers agree that there are different parenting styles that can be effective for different racial groups, and that what is the “ideal” response to children depends on cultural beliefs about parenting and child socialization (Luster and Okagaki 2005).

Some scholars caution against a parochial conception of black parents as invariably harsh and suggest prior evidence overstates the claim that black parents are oriented to punitive parenting styles (Bluestone and LaMonda 1999). Critics note many examinations of white and black parenting styles fail to account for the confounding effects of socioeconomic status (e.g., Baumrind 1972). This methodological shortcoming obscures the notion that disciplinary forms of parenting may be prominent among blacks for a variety of reasons related to their socioeconomic position in society (e.g., higher incidences of family poverty and lower social status). Furthermore, an extension to the social class argument is that punitive parenting is likely to be more prevalent among lower socioeconomic parents because the neighborhoods in which lower-class individuals reside often pose elevated risks to children. These parents account for their children’s greater susceptibility for involvement in deviant activities by employing stricter parenting measures (Kelley, Power, and Wimbush 1992; Ogbu 1981). According to this explanation, punitive parenting is a product of social class rather than race.

Question 2: Is Social Class Important for Parenting Philosophy?

Bronfenbrenner (1979) developed an ecological theory which suggested that family processes (e.g., parental behavior) and contextual factors (e.g., social class or race) interact to affect children’s development. There is a great deal of discussion among sociologists and psychologists on the precise nature of this interaction. Some scholars have argued that social class plays a determinative role shaping the particular responses parents employ toward their children’s academic outcomes. More than four decades ago, Kohn (1963) offered that parents from lower social class (particularly those with lower education) positions were more prone toward child external authority (e.g., punishment). Parents of higher social class pay less attention to raising obedient children, and more attention to children’s internal states, relying more on reasoning, explaining, and psychological techniques of discipline (Hughes and Perry-Jenkins 1996). The link here is that social class affects which characteristics parents will value for their children and this variation in values leads to differences in parenting behavior. Though Kohn’s theory was developed specifically in the context of childrearing, it gives reason to expect parenting strategies for handling inadequate achievement will vary across family contexts.

Scholars have criticized Kohn’s theory on several accounts, namely that it suggests that middle and upper class parents have better or more worthy values, which can be used evaluatively to blame individuals in lower social class positions for their children’s academic difficulties (Hughes and Perry-Jenkins 1996). More recent theories suggest that parents’ education affects how they respond to their children’s school performance because it alters parents’ expertise. For example, according to efficacy theory, the extent to which parents directly help their children improve academically will likely depend on how capable they feel in this arena. Lareau and Shumar (1996) report such results in their ethnographic study, in which a working-class parent told her nephew that in order to receive help with fractions he would have to wait until his older brother arrived home. Another parent reported being “embarrassed” that he could not assist his son with 3rd-grade homework. In their view, parents have developed perspectives about how best to help their children in school, and these perspectives are heavily influenced by the social resources (e.g., human capital) parents hold. Thus, while the desire to see their child’s achievement improve may be near uniformity among parents, the approach they use to directly help their child improve is likely to vary widely since parents differ in their social class position, particularly with respect to their education levels.

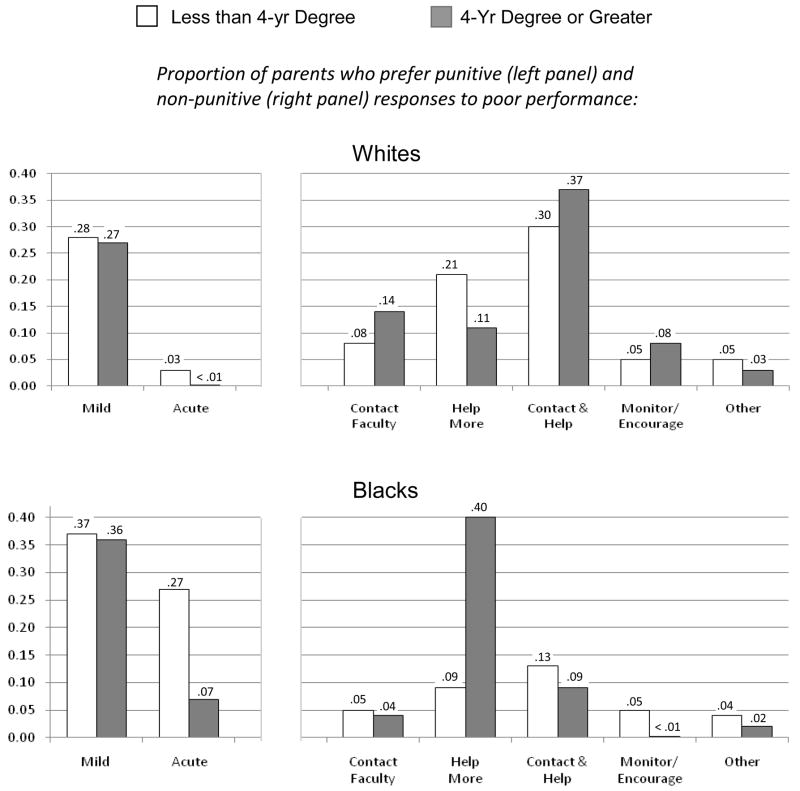

We examine whether social class—human capital in particular—structures parenting philosophy toward addressing inadequate academic performance for white and black parents. These findings are displayed in Figure 3. We simply replicate Figure 1 and display the findings for each racial group based on parents’ level of education. We stratify social class according to parents’ level of education (parents’ with less than a four-year college degree and those with a four-year degree or greater) because it is closely related to parental expectations and behaviors toward children’s schooling and how effectively they communicate their expectations to their children. Simply giving more material resources to parents does not mean they will be more capable of rationalizing how their school involvement affects a child’s achievement trajectory.

Figure 3. Parents’ Preferred Response to Poor Academic Performance by Social Class: CDS.

Note: Findings are unadjusted. All differences in the top panel are significant at the .05 level with the exception of mild. All differences in the bottom panel are significant at the .05 level with the exception of mild and contact faculty. All racial differences within social class are significant at the .05 level with the exception of monitor/encourage and other for less than 4-yr degree. Unweighted N= 1041.

The top panel of Figure 3 shows that in general parenting philosophy for addressing inadequate academic performance varies modestly by level of parental education for whites. The bottom panel shows that a substantially greater share of blacks with lower levels of education prefer acute punitive responses (.27) than those with a 4-year degree (.07). In contrast, 40 percent of blacks with a 4-year degree prefer to help their child more compared to only 9 percent of blacks without a 4-year degree. However, social class has minor implications for the racial differences observed in Figure 1. Blacks in both the lower and higher social class groups prefer both forms of punitive responses more than their white counterparts. Similarly, both groups of black parents are less inclined to contact faculty and to contact faculty in conjunction with helping their child than both groups for whites. The findings for preferring to provide the child with more help yield a different pattern; whereas whites with a four-year degree have a lower inclination to help than their less educated counterparts (only 11 and 22 percent, respectively), a much greater proportion of blacks with a four-year degree prefer to help more than less educated blacks (40 and 9 percent, respectively).

In general, Figure 3 shows that blacks prefer punitive responses for dealing with their child’s inadequate academic performance more than whites regardless of parents’ level of education. Also, with the exception of providing youth with more help, blacks have a lower preference for non-punitive responses than whites. This pattern is alarming to the extent that these inclinations have implications for youths’ academic outcomes.

Question 3: Does Parenting Philosophy have Implications for Achievement?

Although most studies on the role of parents in schooling focus on the link between parental involvement and academic outcomes, a small number of studies within the child development literature suggest that a parental response to inadequate academic performance might have implications for children’s academic outcomes. In a well conducted report, Dornbusch and colleagues’ (1987) utilized self reports from 7,836 high school students to examine the link between parental behaviors and adolescent performance. Their findings revealed that white and Latino adolescents had higher grade point averages under authoritative parenting styles; this finding did not hold for Asian and African American adolescents. Parents’ use of encouragement after viewing their child’s grades led to increases in effort and academic performance. Although Dornbusch’s study employed longitudinal data, design issues such as the use of student responses to measure parenting styles prohibited them from establishing a clear link between child performance and parental responses. A related study by Steinberg, Elmen, and Mounts (1989) confirmed Dornbusch et al.’s (1987) findings using longitudinal data. However, their results were limited by the homogeneity of their sample, which mainly included whites from middle-class and professional backgrounds. Thus, few studies examine achievement prospectively to provide a sense of how various parenting philosophies for addressing inadequate achievement are related to academic outcomes.

Developmental theorists have hypothesized that the link between parenting strategies and adolescent achievement operates through (or is explained by) psychological characteristics governing a child’s approach towards academic affairs. For example, Gottfried, Fleming and Gottfried (1998) find that adolescents’ intrinsic motivation—characterized by enjoyment and inherent pleasure in school learning is—fostered in environments which provide optimal challenge, competence-promoting feedback, and support for autonomous behavior. Conversely, environments with more controlling aspects, such as those relying on surveillance, often undermine intrinsic motivation (Deci and Ryan 1985). The direction of these findings is consistent with previous research (Ginsburg and Bronstein 1993). Thus, research generally finds that granting children autonomy through an emphasis on independence and reasoning rather than punishment is positively associated with their perceived competence, self-initiated regulation in the classroom, and academic achievement (Grolnick and Ryan 1989; Steinberg, Elmen, and Mounts 1989). Therefore, one should expect that a tendency toward punitive parenting approaches for dealing with inadequate academic performance will be less effective than non-punitive parenting approaches.

We show the estimated effect of the various types of approaches within each parenting philosophy for addressing inadequate performance on reading and math achievement in Table 2. The findings are displayed separately for four subsamples: whites, blacks, youth whose parents do not hold a four-year college degree and those whose parents have a four-year degree or greater. The following equation was employed to obtain the findings in the top panel of Table 2:

where achievement measured during the second wave of the CDS (w2) is a function of punitive parental responses (β1 and 2). Parents who reported a preference for non-punitive approaches served as the reference group. These parents were grouped separately from those that did not affirm any of the preferences we examined, which is reflected by δ—the estimate for “other.” The next estimate (λ) is for a vector of social class (X), which includes race when the analysis is conducted by parents’ level of education in the right-hand panel of Table 2 (and for all analyses in Table 3). The final two estimates are for youths’ prior achievement and grade level in school during CDS-II. To obtain the findings in the bottom panel, we employed the following equation:

Table 2.

Implication of Parental Response to Inadequate Performance by Race and Class: CDS

| Race

|

Social Class

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whites

|

Blacks

|

< 4-yr Degree

|

4-yr Deg. or>

|

|||||

| Read | Math | Read | Math | Read | Math | Read | Math | |

| Punitive (vs. Non-Punitive Group) | ||||||||

| Mild | −0.91*** (0.20) | −1.40*** (0.20) | −1.38*** (0.40) | −2.13*** (0.40) | −1.95*** (0.21) | −3.05*** (0.21) | 0.42 (0.35) | 1.82*** (0.35) |

| Acute | −6.45*** (0.63) | −4.03*** (0.65) | −3.27*** (0.43) | −5.15*** (0.44) | −4.49*** (0.36) | −5.28*** (0.36) | −8.75*** (1.87) | −0.99 (1.86) |

| Constant | 33.74*** (1.02) | 61.22*** (0.93) | 37.96*** (2.25) | 61.46*** (2.04) | 48.92*** (1.02) | 73.63*** (0.91) | 25.53*** (1.71) | 71.27*** (1.66) |

| R2 | .42 | .36 | .44 | .32 | .44 | .36 | .44 | .36 |

| Non-Punitive (vs. Punitive Group) | ||||||||

| Contact Faculty | 1.07*** (0.33) | 3.17*** (0.33) | 7.01*** (0.78) | 5.57*** (0.79) | 1.92*** (0.39) | 4.80*** (0.37) | 2.76*** (0.51) | 1.025 (0.54) |

| Help More | 0.52 (0.27) | 0.62* (0.26) | 1.11* (0.50) | 3.25*** (0.50) | 1.43*** (0.27) | 1.70*** (0.26) | −0.16 (0.50) | 0.01 (0.49) |

| Contact & Help More | 1.71*** (0.23) | 1.29*** (0.22) | 3.53*** (0.50) | 4.22*** (0.53) | 3.59*** (0.24) | 4.26*** (0.24) | −1.11** (0.39) | −3.12*** (0.39) |

| Monitor/Encourage | 1.67*** (0.40) | 3.29*** (0.37) | −5.19*** (0.85) | −1.37 (0.84) | 0.44 (0.43) | 3.67*** (0.40) | −0.86 (0.67) | −2.35*** (0.61) |

| Constant | 32.52*** (1.03) | 60.47*** (0.93) | 33.02*** (2.18) | 58.83*** (1.97) | 45.89*** (1.03) | 70.91*** (0.91) | 24.94*** (1.73) | 71.19*** (1.65) |

| R2 | .42 | .36 | .46 | .32 | .44 | .36 | .45 | .37 |

Note: Coefficients are unstandardized. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Estimates in the top panel were obtained from an equation in which both forms of punitive responses were included, along with controls for parents’ education, household income, family structure, youths’ sex, grade in school, prior achievement, other form of response to inadequate performance, and a flag or “missing data” measure for each predictor—coded as 0 if not missing and 1 if missing. Race is included as a control for the analysis by social class in the right-hand panel. The findings in the bottom panel were obtained from an equation that includes all forms of non-punitive measures and the aforementioned controls. Whereas the parenting measures are from CDS-I, the measures for youths’ academic achievement are from CDS-II. To account for the potential of ceiling and floor effects, these analyses are for the middle 90 percent of the achievement distribution. Unweighted N = 1041.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

Table 3.

Implication of Parental Response to Inadequate Performance: CDS

| Achievement Distribution

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th – 50th %tile

|

51st – 95th %tile

|

|||

| Read | Math | Read | Math | |

| Punitive (vs. Non-Punitive Group) | ||||

| Mild | −0.28* (0.12) | −0.92*** (0.12) | −0.12 (0.22) | −0.36 (0.19) |

| Acute | −0.68*** (0.19) | −0.73*** (0.20) | −4.06*** (0.58) | −2.90*** (0.55) |

| Constant | 68.20*** (0.68) | 85.85*** (0.60) | −77.13*** (1.22) | 89.24*** (0.96) |

| R2 | .36 | .21 | .20 | .21 |

| Non-Punitive (vs. Punitive Group) | ||||

| Contact Faculty | 1.30*** (0.23) | 1.88*** (0.26) | −1.18*** (0.32) | −0.33 (0.28) |

| Help More | 0.10 (0.15) | 0.71*** (0.15) | 0.60* (0.29) | 0.60* (0.25) |

| Contact Faculty & Help More | 0.70*** (0.14) | 0.69*** (0.14) | 0.75** (0.24) | 0.51* (0.21) |

| Monitor/Encourage | −0.97*** (0.22) | 1.39*** (0.23) | 2.86*** (0.46) | 2.84*** (0.35) |

| Constant | 67.89*** (0.67) | 85.09*** (0.59) | 74.68*** (1.21) | 89.06*** (0.95) |

| R2 | .36 | .21 | .21 | .22 |

Note: Coefficients are unstandardized. Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Estimates in the top panel were obtained from an equation in which both forms of punitive responses were included, along with controls for race, parents’ education, household income, family structure, youths’ sex, grade in school, prior achievement, other form of response to inadequate performance, and a flag or “missing information” measure for each predictor—coded as 0 if not missing and 1 if missing. The findings in the bottom panel were obtained from an equation that includes all forms of non-punitive measures and the aforementioned controls. The parenting measures are from CDS-I and the measures for youths’ academic achievement are from CDS-II. Unweighted N = 1041.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001 (two-tailed tests)

For these analyses, parents who reported a preference for punitive responses served as the reference group.

In general, the findings show that whereas an inclination toward punitive parental responses are associated with declines in achievement, a tendency toward non-punitive responses to inadequate academic performance are associated with increases in achievement. These patterns are similar for both reading and math. Findings for the punitive philosophy—displayed in the top panel—suggest that both mild and acute punitive responses to inadequate academic performance are associated with declines in achievement for all subsamples (except for the higher social class subsample, for which mild is not associated with declines in reading and neither mild nor acute appear to compromise math). The negative estimated effects of the punitive responses also exist for analysis based on the MADICS (results available upon request).

The bottom panel of Table 2 contains findings for the responses within the non-punitive philosophy grouping. With the exception of help more for reading (which is not significant), it seems that all non-punitive responses are associated with increases in achievement for whites. The next few columns show that an inclination toward contacting faculty, helping more, and employing both simultaneously is associated with increases in achievement for blacks and youth whose parents do not have a 4-year college degree. However, monitoring and/or encouraging youth is associated with a decline in reading for blacks and is not significant for the reading achievement of less advantaged youth. Among youth whose parents hold a 4-year degree or greater, only a tendency to contact faculty is associated with increases in reading. Providing more help and encouragement is not significant for reading achievement and simultaneously contacting faculty and providing more help is associated with a decline in both reading and math.

In order to determine whether the patterns observed in Table 2 are fairly robust across the achievement distribution, we repeated this analysis for two additional subsamples: students in the 5th to 50th percentile of the achievement distribution and those in the 51st to 95th percentile. Displaying findings for these groups has two advantages. First, this accounts for the potential of ceiling and floor effects—the distortion of estimates resulting from top performing students having scores with nowhere to go but down (vice versa for inadequately performing youths). Second, the estimates can be displayed separately for students in the top and bottom half of the achievement distribution. Findings for these subgroups are displayed in Table 3.

The findings in the top panel suggest that both mild and acute punitive responses hurt reading and math achievement for students in the lower performing subsample. In contrast, only an acute punitive response is associated with declines in achievement for students in the top half of the achievement distribution. With regard to the findings for the non-punitive philosophy, the bottom panel suggests that an inclination towards contacting faculty, whether or not it is done in conjunction with providing more help, is associated with an increase in both reading and math achievement for the students in the lower performing subsample. However, providing more help without consulting with teachers and increasing one’s level of supervision and encouragement are associated with improvements in achievement only in math for this group. Higher performing students seem to benefit in both reading and math from parental help, contacting faculty when done simultaneously with parental help, and encouragement.

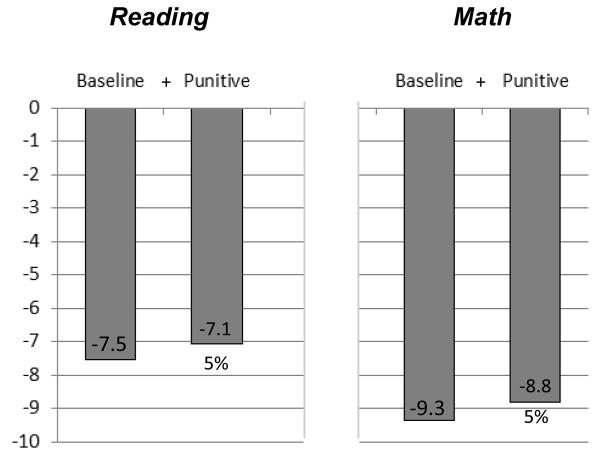

In addition to examining the link between parenting philosophy and achievement, we examine the implications of parenting philosophy for the black-white achievement gap. Figure 4 displays the results from this analysis using data from the CDS. The first bar shows that the baseline gap in reading, which includes the full set of controls, is 7.5 points. After accounting for parents’ punitive responses, the gap declines to 7.1 points—approximately a 5 percent reduction. A similar pattern is observed for math in the right-hand panel, in which the baseline gap declined from 9.3 to 8.8 points after accounting for parents’ punitive responses, which is also a 5 percent reduction. Overall, it appears that a modest portion of the black-white achievement gap can be attributed to parents’ punitive responses to inadequate performance.

Figure 4. Achievement for Blacks Relative to Whites and Percent Declines in the Black-White Achievement Gap Due to Parenting Philosophy: CDS.

Note: Baseline represents the achievement gap after accounting for parents’ education, household income, family structure, youths’ sex, grade in school, prior achievement, and a flag or “missing information” measure for each predictor—coded as 0 if not missing and 1 if missing. The column labeled punitive represents the achievement gap from an equation that includes all factors from the baseline model and the following three variables: mild punitive, acute punitive, and the other form of response. All estimates are significant at the .001 level. Unweighted N= 1041.

Summary and Discussion

In this study we examined whether racial and social class differences exist in parenting philosophy for addressing inadequate achievement. We also estimated the extent to which various responses within the non-punitive and punitive philosophies impact reading and math achievement by race, social class, and achievement level. Lastly, we examined whether punitive parenting has implications for the racial achievement gap. Our investigation revealed several findings relevant for sociological theory and important for educators and policy makers. We offer four main findings.

Whereas within the context of inadequate performance whites appear more inclined to intervene in non-punitive ways, black parents appear more inclined to respond in punitive ways. Smetana and Gaines’ (1999) discussion of their results in a study on conflicts between parents and their adolescent children provides a useful interpretation for this finding. When parents must decide how to respond to their child’s inadequate performance they are engaging in a form of conflict resolution. Smetana and Gaines (1999) suggest black parents tend to view conflicts in terms of respect for parents and obedience to authority. In contrast, white parents typically view conflicts as a means for establishing personal jurisdiction, a justification Smetana (1995) labels as a social-cognitive aspect of autonomy development.

Second, whereas a non-punitive parenting philosophy is associated with improvement in reading and math achievement, a punitive parenting philosophy appears to lead children to perform worse in both subjects. When considered along with the aforementioned findings on racial differences, the implication here is that whereas white parents are likely to respond in ways that increase future achievement, black parents are drawn towards punitive approaches, which are negatively associated with achievement for all adolescents. We show that these racial differences do explain a small portion of the black-white achievement gap. Also, although several of the findings are nuanced—for example, that a preference for monitoring and/or encouraging as an intervention is negatively associated with blacks’ reading achievement but not associated with their math achievement—the overall patterns are rather consistent. A parental philosophy favoring punitive approaches for inadequate academic performance seems harmful for children’s achievement, while a non-punitive philosophy seems to benefit achievement.

Third, the implication of parenting philosophy for achievement varies by race. Our findings suggest that a greater likelihood for employing non-punitive responses is associated with greater improvement in reading and math for black youth relative to their white counterparts. Supplemental analyses suggest that blacks would benefit more than whites in both reading and math from parental contact with faculty, greater help from parents, and the employment of both of these strategies simultaneously. Perhaps the most troubling finding reveals that a punitive parenting philosophy (both mild and acute) for dealing with academic performance that is lower than expected seems more negatively associated with math for blacks than whites. This is particularly unfortunate because, as previously noted, black parents are much more likely to employ these responses to inadequate achievement.

Fourth, although having a four-year college degree significantly reduced the odds that black parents would likely employ acute punitive responses, the more educated black parents still express a greater preference for punitive responses than their white counterparts. Recall that whites with a 4-year degree or greater were more inclined to use non-punitive strategies such as contacting faculty, both contacting faculty and providing more help to their children, and monitor/encourage their child. Returning to the efficacy theory, our findings with regards to blacks without a four-year college degree align with the notion that less educated parents would be more likely to use punitive responses, perhaps because they felt incapable of aiding children in non-punitive ways. Our results support Lareau and Shumar’s (1996) claim that more educated parents, equipped with greater amounts of human capital, are more prone to engage with faculty about their child’s academic affairs because they feel more comfortable with how schools operate. This support, though, was shown only among whites. Thus, while there is a connection between parents’ education and preferred parenting strategies for whites and blacks, the strength and pattern of this link varies across racial groups.

How Should Parents Respond to Inadequate Achievement?

A main finding from our analyses is that a non-punitive parenting philosophy enhances future academic performance. It may be that non-punitive strategies are particularly effective because they create an optimal setting under which children can devote more attention to schooling. This setting, void of punitive restrictions on activities, might foster the intrinsic motivation necessary for improved performance (Deci and Ryan 1985). It might also be that parents are re-organizing the way children spend their time, for example, suggesting (rather than explicitly demanding) they exchange some time spent on extracurricular activities for time on activities more essential for academic success. An exchange of this sort may involve spending fewer hours watching television or time alone in recreation, to more time studying with friends or attending after-school classes over the same number of hours. In this way, parents are not using punitive measures to adjust the way their child spends time, which might be the most effective way to motivate children academically.

Conclusion

It must be noted that although black parents appear to respond in ways that negatively affect their children’s academic performance, one should not assume they are less concerned with improving achievement than Whites. While punitive approaches are typically inversely related to more nurturing parent-child relationships, this relationship is not always a one-to-one correlation. Undoubtedly, some parents will be supportive and encouraging while still employing punitive measures. On the one hand, the use of punishment in general is not surprising since parents may feel an obligation to regulate inadequate achievement based on concerns about their child’s future. On the other hand, it is surprising that black parents remain more likely to prefer punishment net of social class, family structure, and family income. While this finding supports the notion that race and class should be distinguished in empirical research, it contrasts with previous findings that attribute punitive parenting styles of blacks to their lower income-status or incidences of single parenting.

There are both strengths and weaknesses to our measure of parental responses. Parents’ report of their likely response precludes us from directly relating their behaviors to child academic outcomes. At the same time, since the question captures expected response, it is likely to be a suitable reflection of parents’ normal parenting approach. It represents an implicit control for behavior “shocks” that could arise if a stressor such as job loss or unforeseen financial hardship occurred concomitantly with inadequate academic performance. Additionally, asking parents such a hypothetical means the structure of the question reduces the probability of parents falsifying about their actual behavior. A stronger sense of stigma may reside over parents’ responses if they were asked, “Have you ever punished your child for inadequate performance?” rather than being asked their likelihood of engaging in several types of responses to their child’s performance. Nevertheless, we supplement the racial comparisons on parental responses with data from the MADICS, which asked parents about the actual approach they have taken in the past to address their child’s inadequate academic performance. Furthermore, the MADICS yields results substantively similar to those found in this study (results available upon request).

We recognize that punishment can take numerous forms. Parents who respond with acute punishment could excoriate children for inadequate achievement or use physical discipline. Since the CDS does not disaggregate punishment in response to inadequate school achievement, we supplemented our analysis with data from the MADICS, which was developed for understanding psychological determinants of behavior and developmental trajectories and contains numerous forms of parental punishment in response to inadequate achievement. The findings showed a similar pattern to the CDS; black parents threaten, physically punish, ground, and withhold rewards more than white parents when their children perform inadequately in school. In sum, the findings from this study suggest that educators and policy makers should pay particular attention to how parents respond to inadequate achievement. Imploring parents of inadequately performing students to be more involved without providing them with some guidance might exacerbate the problem.

The current analysis highlights the importance of understanding parent-child dynamics with regard to education outcomes. The No Child Left Behind initiative (NCLB) calls for schools to increase parental involvement by implementing programs to involve parents in ways that promote academic success. Yet, perhaps NCLB has overlooked strategies parents can employ at home to increase achievement. The present findings suggest the effects of the NCLB mandate might be different depending on which type of parental involvement is encouraged.

While we feel our results are important, we also recognize that parental responses are just one factor among many which influence achievement. Factors such as school type, curriculum, school quality, and family SES have all been shown to play salient roles in child academic outcomes (Card and Kreuger 1998; Hanushek 1997; Teitelbaum 2003; White et al. 1996; Burkam et al. 2004). However, strategies schools enact to improve performance such as recruiting and training high-quality teachers, or strengthening the quality of program–instruction have received more attention than what responses parents should employ to improve their children’s achievement. This study could inform policy makers and school personnel of the racial and social class variation in parental approaches to children’s achievement and some implications this has for improving achievement. It also provides some suggestion on which responses should be encouraged and which should be avoided, particularly for black parents.

We believe the examination of the link between parental responses and future achievement is in its early stages. Further research directives are warranted. Researchers and policy makers should comprehensively explore dimensions in which parents can help children succeed academically. Additionally, findings from this study could be greatly enhanced by qualitative analyses aimed at providing greater depth to each parental response measure. Such studies could reveal the underlying sentiment parents have when enacting a given response or reduce the uncertainty in interpretation of response categories between parents and researchers, a consistent problem of survey research. Additional research should also explore this topic using other racial-ethnic groups such as Asian Americans and Hispanics.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Chandra Muller for helpful comments. This research is supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development (Grant 5 R24 HD042849) awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin, by the National Science Foundation (Grant DUE-0757018) STEM in the New Millennium: Preparation, Pathways and Diversity, awarded to Chandra Muller and Catherine Riegle-Crumb, by NICHD Grant #R01 HD33437 to Jacquelynne S. Eccles and Arnold J. Sameroff, by the Spencer Foundation Grant MG #200000275 to Tabbye Chavous and Jacquelynne S. Eccles, and by the MacArthur Network on Successful Adolescent Development in High Risk Settings (Chair: R. Jessor).

Footnotes

All data and coding information is available upon request.

Contributor Information

Keith Robinson, University of Texas at Austin.

Angel L. Harris, Princeton University

References

- Allen Walter Recharde. Race, Income and Family Dynamics: A Study of Adolescent Male Socialization Processes and Outcomes. In: Spencer M, Brookins G, Allen W, editors. Beginnings: The Social And Affective Development of Black Children. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1985. pp. 273–92. [Google Scholar]

- Amato Paul R, Fowler Frieda. Parenting Practices, Child Adjustment, and Family Diversity. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:703–716. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind Diana. Current patterns of Parental Authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs. 1972;41:1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone Cheryl, Tamis-LeMonda Catherine S. Correlates of Parenting Styles in Predominantly Working-and Middle-Class African American Mothers. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:881–93. [Google Scholar]

- Borkowski John G, Ramey Sharon L, Bristol-Power Marie. Parenting and the Child’s World: Influences on Academic, Intellectual, and Socio-Emotional Development. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner Uri. Contexts of Child-Rearing – Problems and Prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34: 844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Burkham David T, Ready Douglas D, Lee Valerie E, LoGerfo Laura F. Social-Class Differences in Summer Learning between Kindergarten and First Grade: Model Specification and Estimation. Sociology of Education. 2004;77:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Card David, Krueger Alan B. School Resources and Student Outcomes. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1998;559:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Cose Ellis. The Rage of a Privileged Class. New York: Harper Collins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe Robert. Academic Orientation and Parental Involvement in Education during High School. Sociology of Education. 2001;74:210–30. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard Kirby, Dodge Kenneth A, Bates John E, Pettit Gregory S. Physical Discipline among African American and European American Mothers: Link’s to Children’s Externalizing Behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:1065–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Deci Edward L, Ryan Richard M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Domina Thurston. Leveling the Home Advantage: Assessing the Effectiveness of Parental Involvement in Elementary School. Sociology of Education. 2005;78:233–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch Sanford M, Ritter Philip L, Herbert Leiderman P, Roberts Donald F, Fraleigh Michael J. The Relation of Parenting Style to Adolescent School Performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1244–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin Joe R, Sikes Melvin P. Living with Racism: The Black Middle-Class. Boston: Beacon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg Golda S, Bronstein Phyllis. Family Factors Related to Children’s Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivational Orientation and Academic Performance. Child Development. 1993;64:1461–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Nancy A, Hiraga Yumi, Cauce Ana Mari. Observing mother-daughter interaction in African-American and Asian American families. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson EA, Thompson AI, Futrell JA, editors. Resiliency in African-American families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried Adele Eskeles, Fleming James S, Gottfried Allen W. Role of Cognitively Stimulating Home Environment in Children’s Academic Intrinsic Motivation: A Longitudinal Study. Child Development. 1998;69:1448–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick Wendy S, Ryan Richard M. Parent Styles Associated with Children’s Self-Regulation and Competence in School. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1989;81:143–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek Eric A. Assessing the Effects of School Resources on Student Performance: An Update. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1997;19:141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Angel L. Kids Don’t want to Fail: Oppositional Culture and the Black-White Achievement Gap. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison Algea O, Wilson Melvin N, Pine Charles J, Chan Samuel J, Buriel Raymond. Family Ecologies of Ethnic Minority Children. Child Development. 1990;61:347–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges Larry V, Nowell Amy. Changes in the Black-White Gap in Achievement Test Scores. Sociology of Education. 1999;72:111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Shirley A. Class, Race, and Gender Dimensions of Child Rearing in African American Families. Journal of Black Studies. 2001;31:494–508. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Shirley A, Sprague Joey. Parenting in Black and White Families: The Interaction of Gender with Race and Class. Gender and Society. 1999;13:480–502. [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild Jennifer L. Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class, and the Soul of the Nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Robert J, Perry-Jenkins Maureen. Social Class Issues in Family Life Education. Family Relations. 1996:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram Melissa, Wolfe Randi B, Lieberman Joyce M. The Role of Parents in High-Achieving Schools Serving Low-Income, At-Risk Populations. Education and Society. 2007;39:479–99. [Google Scholar]

- Julian Teresa W, McKenry Patrick C, McKelvey Mary W. Cultural Variations inParenting; Perceptions of Caucasion, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American Parents. Family Relations. 1994;43:30–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kardiner Abram, Ovesey Lionel. The Mark of Oppression. New York: World; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley Michelle L, Power Thomas G, Wimbush Dawn D. Determinants of Disciplinary Practices in Low-Income Black Mothers. Child Development. 1992;63:573–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn Melvin L. Social Class and Parent-Child Relationships: An Interpretation. American Journal of Sociology. 1963;68:471–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette, Shumar Wesley. The Problem of Individualism in Family-School Policies. Sociology of Education. 1996;69:24–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette. Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luster Tom, Okagaki Lynn. Parenting: An Ecological Perspective. Mahwah, N J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd Vonnie C. The Impact of Economic Hardship on Black Families and Children: Psychological Distress, Parenting, and Socioemotional Development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal Ralph B., Jr Parental Involvement as Social Capital: Differential Effectiveness on Science Achievement, Truancy, and Dropping Out. Social Forces. 1999;78:117–44. [Google Scholar]

- McGroder Sharon M. Parenting among Low-Income, African American Single Mothers with Preschool-Age Children: Patterns, Predictors, and Developmental Correlates. Child Development. 2000;71: 752–771. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlemiss Wendy. Brief Report: Poverty, Stress, And Support: Patterns Of Parenting Behavior Among Lower Income Black And Lower-Income White Mothers. Infant and Child Development. 2003;12: 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Mosby Lynetta, Anne Warfield Rawls Rawls, Meehan Albert J, Mays Edward Pettinari, Johnson Catherine. Troubles in Interracial Talk about Discipline: An Examination of African American Childrearing Narratives. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1999;30:489–521. [Google Scholar]

- Muller Chandra. Maternal Employment, Parental Involvement, and Mathematics Achievement among Adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Muller Chandra. Gender Differences in Parental Involvement and Adolescents’ Mathematics Achievement. Sociology of Education. 1998;71:336–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu John U. Origins of Human Competence: A Cultural-Ecological Perspective. Child Development. 1981;52: 413–29. [Google Scholar]

- Portes P, Dunham R, Williams S. Assessing Child-Rearing Style in Ecological Settings: Its Relation to Culture, Social Class, Early Age Intervention and Scholastic Achievement. Adolescence. 1986;21: 723–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Agenda. Great Expectations: How the Public and Parents—White, African American and Hispanic—View Higher Education. Washington, DC: The National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education; 2000. (Report #00–2) [Google Scholar]

- Smetana Judith G, Gaines Cheryl. Adolescent-Parent Conflict in Middle-Class African American Families. Child Development. 1999;70:1447–63. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana Judith G. Parenting Styles and Conceptions of Parental Authority during Adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:299–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Laurence, Elmen Julie D, Mounts Nina S. Authoritative Parenting, Psychosocial Maturity, and Academic Success among Adolescents. Child Development. 1989;60:1424–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson David L, Baker David P. The Family-School Relation and the Child’s School Performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1348–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui-Chu Esther Ho, Douglas Willms J. Effects of Parental Involvement on Eighth-Grade Achievement. Sociology of Education. 1996;69:126–41. [Google Scholar]

- Teitlebaum Peter. The Influence of High School Graduation Requirement Policies in Mathematics and Science on Student Course-Taking Patterns and Achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2003;25:31–57. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. A Profile of Parents of Eighth Graders. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- White Paula A, Gamoran Adam, Smithson John, Porter Andrew C. Upgrading the High School Math Curriculum: Math Course-Taking Patterns in Seven High Schools in California and New York. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 1996;8:285–307. [Google Scholar]