Abstract

In utero exposure to antiandrogenic xenobiotics such as di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) has been linked to congenital defects of the male reproductive tract, including cryptorchidism and hypospadias, as well as later life effects such as testicular cancer and decreased sperm counts. Experimental evidence indicates that DBP has in utero antiandrogenic effects in the rat. However, it is unclear whether DBP has similar effects on androgen biosynthesis in human fetal testis. To address this issue, we developed a xenograft bioassay with multiple androgen-sensitive physiological endpoints, similar to the rodent Hershberger assay. Adult male athymic nude mice were castrated, and human fetal testis was xenografted into the renal subcapsular space. Hosts were treated with human chorionic gonadotropin for 4 weeks to stimulate testosterone production. During weeks 3 and 4, hosts were exposed to DBP or abiraterone acetate, a CYP17A1 inhibitor. Although abiraterone acetate (14 d, 75mg/kg/d po) dramatically reduced testosterone and the weights of androgen-sensitive host organs, DBP (14 d, 500mg/kg/d po) had no effect on androgenic endpoints. DBP did produce a near-significant trend toward increased multinucleated germ cells in the xenografts. Gene expression analysis showed that abiraterone decreased expression of genes related to transcription and cell differentiation while increasing expression of genes involved in epigenetic control of gene expression. DBP induced expression of oxidative stress response genes and altered expression of actin cytoskeleton genes.

Key Words: xenograft, Hershberger assay, antiandrogen, abiraterone acetate, di-n-butyl phthalate, CYP17A1.

In the rat, disruption of fetal androgen signaling by antiandrogenic xenobiotics can produce dramatic negative consequences for the male reproductive tract (Rider et al., 2008). It has been hypothesized that antiandrogens have similar effects in the human fetal male reproductive tract. These effects are included as part of a hypothesized testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS), wherein perturbation of fetal Sertoli and Leydig cell function, through mechanisms including impaired fetal androgen signaling, is associated with cryptorchidism and hypospadias, decreased adult male fertility, and increased testicular cancer risk in adulthood (Lottrup et al., 2006; Toppari et al., 2010). However, the impact of some putative antiandrogens, particularly phthalates, on the development of the human male reproductive tract is unclear.

Phthalates are organic esters used as plasticizers, to which humans are almost universally exposed. In the rat, phthalates interfere with male reproductive tract development to produce TDS endpoints (Howdeshell et al., 2008). However, a mechanistic association between phthalate exposure and TDS outcomes has not been established, and effects of fetal phthalate exposure appear species specific. In utero di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) exposure reduces fetal testicular testosterone in the rat but not in the mouse (Gaido et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2012). Neither model is necessarily predictive of the human response.

In rodents, the effects of suspected antiandrogens can be assessed directly. In utero exposure studies assess testicular hormone levels and androgen-sensitive endpoints such as anogenital distance, nipple retention, hypospadias, and cryptorchidism (Howdeshell et al., 2008; Rider et al., 2008). The Hershberger assay allows for quantification of antiandrogenic effects in juvenile rats, with endpoints including serum hormones and the weights of androgen-responsive accessory sex organs (Gray et al., 2005). However, there is no means by which to study the physiological effects of antiandrogens in intact human fetal testis. To address this issue, human fetal testis xenograft models have been developed. In 2 studies, DBP exposure induced multinucleated germ cells (MNGs) in xenografts but had no effect on expression of genes related to androgen biosynthesis (Heger et al., 2012), or host serum testosterone or seminal vesicle weight (Mitchell et al., 2012). No study to date has demonstrated inhibition of testosterone biosynthesis in human fetal testis xenografts.

Abiraterone acetate is an irreversible steroidal CYP17A1 inhibitor (Jarman et al., 1998), which decreases testosterone in in vivo rodent studies (Duc et al., 2003; Haidar et al., 2003) and is used clinically for treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer (de Bono et al., 2011). We hypothesized that abiraterone acetate, but not DBP, would inhibit testosterone biosynthesis in human fetal testis xenografts. The model previously published by Heger et al. (2012) was modified to optimize measurements of antiandrogenic effects, using a human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG)–stimulated castrated mouse host, similar to Mitchell et al. (2012). This xenograft bioassay allowed for the measurement of host serum hormones and androgen-sensitive accessory sex organ weights, parallel to the Hershberger bioassay in the rat, to quantify inhibition of androgen signaling in human fetal testis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal care.

Adult male athymic nude mice (Crl:NU(NCr)-Foxn1 nu, strain code 490) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, Massachusetts) and housed in the Brown University Animal Care Facility under a 12:12h light-dark cycle with controlled temperature and humidity. Mice were given free access to water and Purina Rodent Chow 5001 (Farmer’s Exchange, Framingham, Massachusetts). All animal care protocols were approved by the Brown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Donor information.

Human fetal testis samples originated from spontaneous pregnancy losses and were donated with full informed consent, as previously described (De Paepe et al., 2012), in accordance with protocols approved by the Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island Institutional Review Board. At the time of donation, the gestational age of the fetus was recorded, as well as any relevant notes regarding the pregnancy and the postmortem interval from delivery until the time of xenograft surgery (Table 1). Human fetal testis tissue was transported from Women and Infants Hospital, Providence, RI, to Brown University on ice in Leibovitz’s L15 media supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and gentamicin (each 50 μg/ml). Testis tissue was dissected under aseptic conditions. A small piece of each testis was fixed immediately in 10% neutral-buffered formalin (NBF), another piece was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the remainder was prepared for xenograft surgery. All unimplanted samples were morphologically normal, as verified by histopathology, and no sample was used after a postmortem interval greater than 36h.

TABLE 1.

Donors and Experimental Conditions

| Donor ID | GA (weeks) | PMI (h) | Surgery Date | Treatment | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17,18 | 22 | 20 | May 18, 2012 | Abiraterone | Twins |

| 19 | 20 | 16.5 | September 11, 2012 | DBP | PROM; no prenatal care |

| 20 | 16 | 33 | October 12, 2012 | DBP | |

| 23 | 20 | 17 | November 29, 2012 | Abiraterone | |

| 25 | 20 | 21 | January 9, 2013 | Abiraterone | |

| 26 | 20 | 12 | March 1, 2013 | DBP | No vehicle-treated sham |

Treatments: abiraterone—14 d 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate or vehicle (distilled water with Tween-20) po. DBP—14 d 500mg/kg/d DBP or vehicle (corn oil) po. Both treatments followed 14 d 20 IU hCG sc 3 times per week; hCG treatment continued concurrently with DBP or abiraterone treatment.

Abbreviations: DBP, di-n-butyl phthalate; GA, gestational age; PMI, postmortem interval; PROM, premature rupture of membranes.

Xenograft surgery and experimental protocol.

Testis tissue was dissected into 64 pieces of approximately 1mm3 for implantation into 8 hosts, with 8 xenografts per host. Within each experiment, 8 xenografted host mice and 6 ungrafted control (“sham”) mice were divided into treatment (abiraterone or DBP) or vehicle groups. The exception to this design was sample 26 (Table 1), in which 2 grafted mice were assigned to control and treated groups, respectively, and 2 “sham” mice were treated with DBP; there was no vehicle-treated sham group. The sample size for all treatment groups, using the donor as the unit of replication, was n = 3, except for the sham-vehicle group in the DBP studies (n = 2). Xenograft surgery was performed using an abdominal incision and renal subcapsular xenograft site, as described by Heger et al. (2012). Immediately prior to xenografting, the host or sham mouse was castrated using an abdominal approach through the same midline incision. Both testes and epididymides were removed in their entirety. The vas deferens and associated vasculature were cauterized using a stainless steel cautery and cut, and any connective tissue was trimmed to allow removal of the testis and epididymis.

Following surgery, hosts were given 20 IU hCG sc 3 times per week for 4 weeks. During the final 2 weeks, mice were also administered daily oral gavage of 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate or 500mg/kg/d DBP (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri), or matching vehicle control (diH2O with approximately 0.3% Tween-20 or corn oil, respectively), according to the treatment designations in Table 1. Abiraterone vehicle was chosen based on similarity with Duc et al. (2003). Abiraterone acetate tablets (Zytiga, Centocor Ortho Biotech, Horsham, Pennsylvania), obtained by donation of Dr Mark Sigman and Dr Kathleen Huang at Rhode Island Hospital, were ground into a powder using a mortar and pestle and added to the appropriate volume of Tween-20/distilled water solution to produce a uniform suspension. Six hours after the final dose, hosts were euthanized by overdose of isoflurane. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Accessory sex organs and kidneys containing xenografts were removed. Xenografts designated for gene expression analysis were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Xenografts intended for histology and immunohistochemistry were fixed in NBF or modified Davidson’s fixative (MDF). MDF was changed to NBF after 24h, and xenografts were stored in NBF until further processing. Accessory sex organs, including the seminal vesicles, anterior prostate, and levator ani- bulbocavernosus muscles (LABC), were dissected from hosts according to the method of Gray et al. (2005); however, seminal vesicles and anterior prostate were dissected and weighed separately. The Hershberger assay also makes use of the ventral prostate, Cowper’s gland, and glans penis. We dissected ventral, lateral, and dorsal prostate, but found the weights to be highly variable in our mice, making anterior prostate a more consistent endpoint. The mouse Cowper’s gland is smaller than that of the rat and did not provide a reasonable dissection endpoint. We also decided not to use the glans penis, as it is no longer androgen sensitive in the adult hosts, unlike the juvenile rats used for the Hershberger assay. Blood was allowed to coagulate for at least 10min at room temperature and then centrifuged for 10min at 3000·g to obtain serum. Serum was frozen at −80oC and shipped on dry ice to the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction, where radioimmunoassays for testosterone and progesterone were performed. Reported coefficients of variation for all radioimmunoassays performed at this facility in 2012 were 4.0% intra-assay and 7.1% interassay for testosterone, and 4.3% intra-assay and 7.3% interassay for progesterone.

Histological analysis.

Xenografts were dehydrated in a series of graded ethanols and embedded in Technovit 7100 glycol methacrylate (Heraeus Kulzer GmBH, Wehrheim, Germany). Three serial 5 µm sections were cut from the approximate center of the graft. Total germ cells and MNGs were counted on the second section using an Olympus BH-2 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, Pennsylvania), as described in Heger et al. (2012), using the first and third sections for confirmation when possible. The second section was scanned into an Aperio ScanScope CS (Aperio Technologies, Vista, CA) at ×40 magnification to quantify seminiferous cord area and total xenograft cross-sectional area in square milli- meters. These measures were used to calculate the ratio of germ cells to seminiferous cord cross-sectional area and the percentage of germ cells that were multinucleated.

Immunohistochemistry.

Additional xenografts were processed and embedded in paraffin, trimmed to their approximate center, and sectioned at 5 µm. Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanols. Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 20min in a vegetable steamer, and then was allowed to cool on the bench top for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked for 30min in a 3% solution of hydrogen peroxide in methanol. Avidin/biotin blocking was performed using the Vector Avidin/Biotin Blocking Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California). Blocking and antibody binding were performed using the Vector Laboratories Mouse on Mouse (M.O.M.) Basic Kit. Tissue sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal Cytochrome P450 17A1 (CYP17A1) antibody, clone 3F11 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, Colorado) at a 1 µg/ml dilution, and a secondary antibody was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Avidin/biotin-based peroxidase conjugation was performed using the Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Laboratories), and staining was developed using Vector Laboratories DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine) Peroxidase Substrate Kit.

Gene expression analysis.

Snap-frozen xenografts were pooled by donor and treatment group to provide sufficient tissue for RNA extraction and to allow the donor to be treated as the unit of replication for real-time PCR analysis. RNA was extracted from snap-frozen xenograft tissue using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California) and on-column DNase treatment with the Qiagen RNase-free DNase Set, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was retained for a separate study. RNA was further purified by overnight precipitation at −80oC with 0.1 volume of 3M sodium acetate, pH 5.2, and 3 volumes of ethanol. Precipitated RNA was centrifuged for 30min at 16 100·g in an Eppendorf 5414 D microcentrifuge at 4oC, washed with ice-cold 75% ethanol, and reconstituted in nuclease-free water. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using the Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) (average A260/A280: 1.75, range = 1.6–1.93; average A260/A230: 2.18, range = 1.73–2.42). RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California) (average RNA Integrity Number: 7.92, range = 5.3–9.6). Gene expression analysis was performed using both Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, California) and RT2 Profiler PCR Arrays (SA Biosciences, Valencia, California), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

To determine the reliability of the microarray-based gene expression analysis, we developed a custom gene expression RT2 PCR Profiler Array (SA Biosciences). The array primarily consisted of genes involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis, including STAR, CYP11A1, CYP17A1, HSD17B1, HSD17B2, HSD17B3, SRD5A1, SRD5A2, HSD3B1, HSD3B2, CYP19A1, CYP11B1, CYP11B2, CYP21A2, HSD11B1, HSD11B2, AKR1C1, AKR1C3, POR, FDX1, FDXR, CYB5A, H6PD, and HSD17B6, the roles of which are reviewed by Miller and Auchus (2011). The hormone receptors AR, LHCGR, FSHR, ESR1, ESR2, and PGR were also included. Despite their primary expression in hypothalamus and pituitary, GNRH1, GNRH2, and GNRHR were included because they are reportedly expressed in fetal rat gonads (Botte et al., 1998). Also included were 2 genes, INSL3 and SCARB1, which are known to respond to DBP in short-term rodent studies (Heger et al., 2012); 3 inhibin genes, INHA, INHBA, and INHBB, because serum inhibin B is altered by some testicular toxicants (Moffit et al., 2013); and 2 genes, KIT and KITLG, related to Sertoli-germ cell contact (Unni et al., 2009).

To determine the best combination of the 5 housekeeping genes (HKGs) to use for analysis of the PCR panel, real-time PCR array data were first analyzed using NormFinder (Andersen et al., 2004) and BestKeeper (Pfaffl et al., 2004). These 2 algorithms determined RPLP1 and HPRT1 to be the most stable HKGs, respectively, and found HSP90AB1 and GAPDH to be the least stable. GAPDH had particularly poor correlation (r = 0.77) with the other HKGs, according to BestKeeper and so was removed from the HKG set. The remaining 4 HKGs each had a correlation of r ≥ 0.91 with each other and were deemed an appropriate set for normalization. PCR array results were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), with the arithmetic mean CT of HPRT1, RPLP1, B2M, and HSP90AB1 acting as the HKG value.

Data analysis and statistics.

For serum hormone, histology, immunohistochemistry, and organ weight data, within-experiment replicates were averaged by treatment group so that the donor (tissue sample) was treated as the unit of replication, giving a sample size of n = 3, except for the vehicle-treated sham group in the DBP experiments, where n = 2. Treatment effects within sham groups were not significant for any comparison using 1-tailed t test or paired t test, so the mean of all values was used as a reference. The effect of treatment on implanted hosts or xenograft tissue was analyzed by a 1-tailed paired t test (n = 3). In the case that data failed the normality assumption by Shapiro-Wilk test, they were analyzed using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Microarray data were processed in the R software environment (R Core Team, 2012), using the RMA algorithm (R package oligo) (Carvalho and Irizarry, 2010) for probe-level summarization and preprocessing with ComBat (Leek et al., 2012) for batch correction. Gene annotation information was joined to the expression data using the hugene10sttranscriptcluster.db package (Li, 2013). Three paired analyses were performed using the limma package in R (commands lmfit and eBayes), with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons (Smyth, 2005): vehicle-treated xenografts versus unimplanted testis (n = 5), abiraterone-treated xenografts versus matched control xenografts (n = 3), and DBP-treated xenografts versus matched control xenografts (n = 3). For the vehicle versus unimplanted comparison, statistical significance was considered as q < 0.05 with a fold change greater than 2.0. For the latter 2 comparisons, there were no q-significant genes, so genes with p < .05 and fold change > 1.5 are listed. Raw and normalized microarray data were submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database (series no. GSE49244), in accordance with MIAME standards (Brazma et al., 2001). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on median-centered microarray data using the PCA module within GenePattern (Reich et al., 2006). Following gene-level analysis, functional enrichment analysis was performed using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (Subramanian et al., 2005) to identify Gene Ontology (GO) classes of genes that were enriched in the microarray data, performing 1000 permutations using the default settings. Real-time PCR data were analyzed using paired t tests to compare vehicle with unimplanted samples (n = 5), as well as DBP and abiraterone with respective vehicle samples (n = 3).

RESULTS

Xenograft Morphology

Germ cells were visible in xenografts from all treatment groups (Figs. 1A–C). Leydig cells from all xenografts expressed CYP17A1 highly, and in the cytoplasm only (Figs. 1D–F), indicating potential for testosterone biosynthesis in all treatment groups. Neither abiraterone (Figs. 1G and H) nor DBP (Figs. 1I and J) treatment resulted in significant differences in the proportion of germ cells that were multinucleated (Figs. 1A and C) or in the number of germ cells per unit of seminiferous cord cross-sectional area (Figs. 1B and D). However, DBP-treated xenografts exhibited a trend toward higher MNG numbers compared with vehicle-treated xenografts (Fig. 1C, p = .051, 1-tailed paired t test).

FIG. 1.

Xenograft morphology. Xenografts treated with vehicle (A), 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate (B), and 500mg/kg/d di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) (C) showed normal fetal testis morphology. Germ cells (arrowheads) were present in all treatment groups (A–C: hematoxylin and eosin; scale bar = 50 µm). Arrow in (C) labels a multinucleated germ cell (MNG) in a DBP-treated xenograft. CYP17A1 was expressed only in the cytoplasm of Leydig cells (D–F; hematoxylin counterstain; scale bar = 50 µm). No difference in staining intensity or localization was evident among xenografts treated with vehicle (D), abiraterone acetate (E), and DBP (F). Frequency of MNGs, expressed as a percentage of total germ cells, was not significantly different following abiraterone acetate (G) or DBP (I) treatment (n = 3, 1-tailed paired t test), but DBP treatment resulted in a trend toward increased MNGs (p = .051). The number of germ cells per unit seminiferous cord area did not differ significantly following either treatment (H, J, n = 3, 1-tailed paired t test). The full color image is available online.

Host Serum Hormone Status

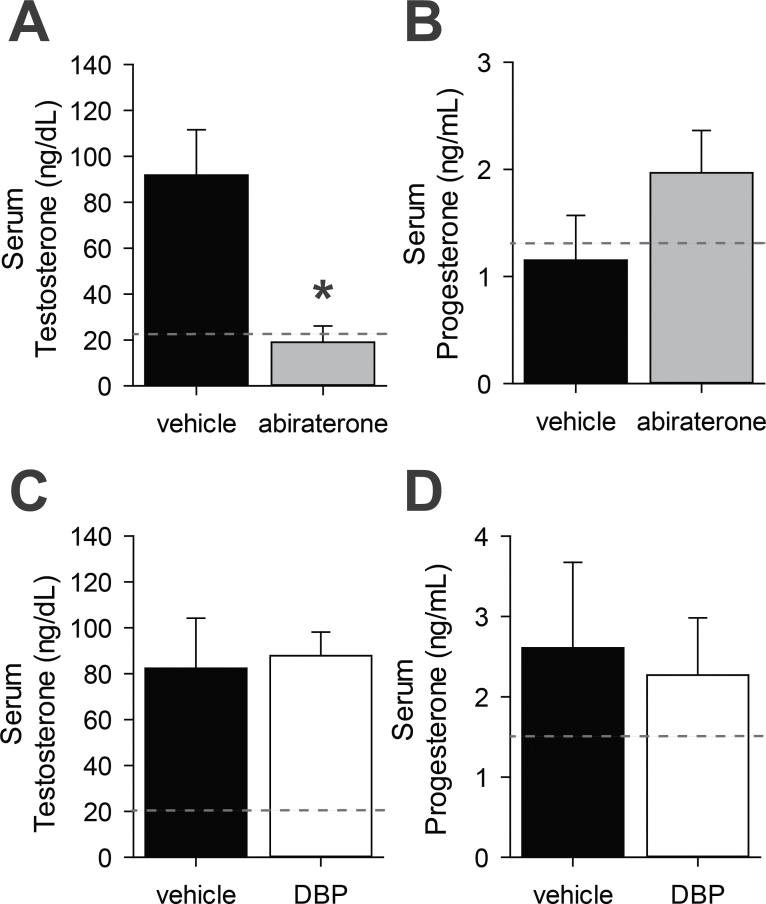

Serum hormone levels were consistently lower in sham than in implanted mice and did not differ by treatment. Abiraterone treatment reduced host serum testosterone levels to approximately 20% of the concentration in vehicle-treated host serum at the time of euthanasia (Fig. 2A, p < .01). The resulting serum testosterone concentration was similar to the ungrafted sham hosts (reference line in 2A). Serum progesterone concentration trended toward an increase in host serum, concomitant with decreasing testosterone, but this was not statistically significant (Fig. 2B). This does suggest, however, that abiraterone is acting in human fetal Leydig cells through inhibition of CYP17A1, as serum progesterone increases with CYP17A1 inhibition (Laier et al., 2006). Conversely, DBP treatment did not reduce host serum testosterone or increase host serum progesterone (Figs. 2C and D).

FIG. 2.

Host serum hormones. Hosts receiving 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate had significantly lower serum testosterone (A) and trended toward higher serum progesterone (B) than vehicle-treated hosts. Serum testosterone (C) and progesterone (D) did not differ significantly between 500mg/kg/d di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) and vehicle-treated hosts. Dotted reference line indicates average value for sham mice. *p < .05, 1-tailed paired t test, n = 3.

The weights of accessory sex organs—seminal vesicles, anterior prostate, and LABC—were also consistently lower in sham than in implanted hosts and did not differ by treatment. Seminal vesicle and LABC weights were significantly reduced (p < .05) in abiraterone-treated hosts compared with vehicle-treated hosts (Figs. 3B–D). DBP treatment resulted in no significant reduction in host accessory sex organ weights (Figs. 3F–H). The weights of all 3 accessory sex organs were significantly correlated (Spearman’s ρ) with serum testosterone at the time of euthanasia (Figs. 3J–L). However, ρ values for the 3 comparisons ranged from 0.638 to 0.696, indicating a moderate strength of correlation. Accessory sex organ weights are likely to be more representative of treatment-derived antiandrogenic effects over the course of the entire 14-d exposure period compared with the more stochastic measurement of serum testosterone. Neither treatment had a significant effect on host body weight (Figs. 3A and E), confirming that neither treatment caused gross toxicity. Of 78 total host and sham mice, there was one fatality, which occurred prior to treatment. Body weight, unlike accessory sex organ weights, was not significantly correlated with host serum testosterone (Fig. 3I).

FIG. 3.

Host accessory sex organ weights. Body weight of host mice was unaffected by treatment with either abiraterone acetate or DBP (A, E). Abiraterone acetate (75mg/kg/d) significantly reduced seminal vesicle weight (B) and levator ani-bulbocavernosus muscle (LABC) weight (D), but not anterior prostate weight (C). Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP, 500mg/kg/d) did not significantly reduce the weights of any of the 3 accessory sex organs (F–H). One-tailed paired t test, n = 3, for all except body weights of abiraterone experiment hosts (panel A, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 3). Seminal vesicle (J), anterior prostate (K), and LABC (L) weights were all significantly positively correlated with serum testosterone, whereas body weight (I) was not significantly correlated with testosterone (Spearman’s ρ). ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Microarray Analysis

The results of PCA indicated that unimplanted samples had relatively similar overall gene expression profiles, whereas all of the implanted xenografts formed a diffuse cluster with no treatment-driven separation. The first 3 principal components described 54.48% of variation in the data set (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Whole-transcriptome gene expression analysis. A, Principal component analysis indicated that unimplanted samples formed a cluster distinct from the xenografts, but xenografts did not resolve by treatment. A total of 55.48% of variation in microarray data was explained in the first 3 principal components (PCs). B, Microarray analysis identified 224 transcript clusters differentially regulated between vehicle-treated xenografts and the matching unimplanted samples (q < 0.05, expression ratio > 2, red circles). A total of 184 transcript clusters were differentially regulated between vehicle- and abiraterone-treated xenografts (C), and 134 between vehicle- and di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP)-treated xenografts (D) (p < .05, fold change > 1.5, green circles). None of the differences in the DBP or abiraterone treatments was significant after post hoc adjustment. Selected genes labeled in (B), (C), and (D) are discussed in the text. The full color image is available online.

Gene-level microarray analysis identified 224 gene transcript clusters differentially regulated between vehicle-treated xenografts and unimplanted samples (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table S1). Several genes with known expression and/or function in testis were also included in the list of significantly downregulated genes. These included CT45A5, a member of the cancer/testis antigen 45 family; the spermatogonial marker GFRA1 and family member GFRA3, receptors for glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor, which functions in germ-Sertoli cell interaction; and the tudor domain-containing protein gene TDRD1. The most frequently represented group of upregulated RNAs were 22 microRNAs, which suggests a strong impact of xenografting on noncoding regulatory RNAs (Supplementary Table S1). Although there were no widespread impacts on steroidogenic genes, CYP19A1 and STARD13 were upregulated. Beyond changes in the expression of individual genes, enrichment analysis revealed a number of GO processes and functions that were affected by both xenografting and treatment (Table 2). Xenografts showed enrichment for the mono-oxygenase activity GO term, which includes CYPs involved in steroid biosynthesis, such as CYP19A1, CYP11B1, and CYP11B2. Not surprisingly, steroid biosynthetic process, hormone metabolic process, and steroid binding also had strong enrichment scores, but they were not statistically significant. Ultimately, xenografts and pregrafting samples differed in expression of genes related to tissue structure, gene expression, and metabolic function. This may reflect the age of the samples, hCG stimulation, or aspects of the xenograft environment.

TABLE 2.

Significant Gene Sets in Microarray Analysis

| GO Term | GO ID | Size | ES | NES | NOM p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched in unimplanted versus vehicle | |||||

| Establishment of organelle localization | GO:0051656 | 16 | 0.71 | 1.54 | .025 |

| Transcription coactivator activity | GO:0003713 | 116 | 0.37 | 1.48 | .025 |

| Transcription activator activity | GO:0016563 | 163 | 0.35 | 1.46 | .031 |

| Regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | GO:0006357 | 274 | 0.30 | 1.41 | .001 |

| Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | GO:0045944 | 60 | 0.31 | 1.38 | .016 |

| Enriched in vehicle versus unimplanted | |||||

| Detection of stimulus involved in sensory perception | GO:0050906 | 21 | −0.68 | −1.40 | .018 |

| Secondary active transmembrane transporter activity | GO:0015291 | 46 | −0.51 | −1.36 | .008 |

| Mono-oxygenase activity | GO:0004497 | 26 | −0.69 | −1.35 | .021 |

| Enriched in abiraterone versus vehicle | |||||

| Activation of protein kinase activity | GO:0015291 | 24 | 0.42 | 1.68 | <.001 |

| Basal lamina | GO:0005605 | 20 | 0.44 | 1.59 | <.001 |

| Maintenance of localization | GO:0051235 | 21 | 0.54 | 1.57 | <.001 |

| Cell projection biogenesis | GO:0030031 | 25 | 0.43 | 1.56 | <.001 |

| Protein homo-oligomerization | GO:0051260 | 21 | 0.42 | 1.56 | <.001 |

| Regulation of gene expression, epigenetic | GO:0040029 | 28 | 0.49 | 1.53 | <.001 |

| Protein oligomerization | GO:0051259 | 38 | 0.32 | 1.52 | <.001 |

| Cell matrix junction | GO:0030055 | 17 | 0.58 | 1.50 | <.001 |

| Adherens junction | GO:0005912 | 22 | 0.47 | 1.47 | <.001 |

| Cell substrate adherens junction | GO:0005924 | 15 | 0.59 | 1.47 | <.001 |

| Nuclear chromosome part | GO:0044454 | 29 | 0.48 | 1.46 | <.001 |

| Calcium ion binding | 95 | 0.38 | 1.43 | <.001 | |

| Enriched in vehicle versus abiraterone | |||||

| Positive regulation of transcription, DNA dependent | GO:0005509 | 110 | −0.31 | −1.62 | <.001 |

| Positive regulation of RNA metabolic process | GO:0051254 | 111 | −0.30 | −1.61 | <.001 |

| Positive regulation of cell differentiation | GO:0045597 | 24 | −0.49 | −1.57 | <.001 |

| Neuron development | GO:0048666 | 58 | −0.44 | −1.57 | <.001 |

| Positive regulation of transcription | GO:0045893 | 131 | −0.29 | −1.57 | <.001 |

| Cellular morphogenesis during differentiation | GO:0000904 | 44 | −0.50 | −1.57 | <.001 |

| Icosanoid metabolic process | GO:0006690 | 17 | −0.65 | −1.56 | <.001 |

| Regulation of blood pressure | GO:0008217 | 22 | −0.76 | −1.55 | <.001 |

| Positive regulation of nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide, and nucleic acid metabolic process | GO:0045935 | 139 | −0.28 | −1.54 | <.001 |

| Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor activity | GO:0004879 | 21 | −0.55 | −1.53 | <.001 |

| Neurite development | GO:0031175 | 50 | −0.46 | −1.53 | <.001 |

| Axon guidance | GO:0007411 | 21 | −0.57 | −1.51 | <.001 |

| Axonogenesis | GO:0007409 | 40 | −0.50 | −1.50 | <.001 |

| Proteinaceous extracellular matrix | GO:0005578 | 93 | −0.38 | −1.50 | <.001 |

| Extracellular matrix | GO:0031012 | 94 | −0.37 | −1.50 | <.001 |

| Intercellular junction | GO:0005911 | 60 | −0.45 | −1.49 | <.001 |

| Monovalent inorganic cation transmembrane transporter activity | GO:0015077 | 34 | −0.53 | −1.49 | <.001 |

| Glutamate signaling pathway | GO:0007215 | 17 | −0.61 | −1.48 | <.001 |

| Vitamin metabolic process | GO:0006766 | 17 | −0.51 | −1.46 | <.001 |

| Neuron differentiation | GO:0030182 | 73 | −0.39 | −1.46 | <.001 |

| Enriched in DBP versus vehicle | |||||

| Myoblast differentiation | GO:0045445 | 15 | 0.62 | 1.72 | <.001 |

| Biogenic amine metabolic process | GO:0006576 | 17 | 0.73 | 1.72 | <.001 |

| Cofactor metabolic process | GO:0051186 | 50 | 0.47 | 1.70 | <.001 |

| Protein N-terminus binding | GO:0047485 | 32 | 0.52 | 1.69 | <.001 |

| Cytoskeletal protein binding | GO:0008092 | 145 | 0.36 | 1.68 | <.001 |

| Amino acid derivative metabolic process | GO:0006575 | 24 | 0.62 | 1.68 | <.001 |

| Sphingolipid metabolic process | GO:0006665 | 24 | 0.55 | 1.68 | <.001 |

| Muscle cell differentiation | GO:0042692 | 20 | 0.56 | 1.60 | <.001 |

| Deoxyribonuclease activity | GO:0004536 | 18 | 0.51 | 1.59 | <.001 |

| Unfolded protein binding | GO:0051082 | 39 | 0.44 | 1.58 | <.001 |

| Translation initiation factor activity | GO:0003743 | 23 | 0.48 | 1.55 | <.001 |

| Actin binding | GO:0003779 | 68 | 0.40 | 1.55 | <.001 |

| Response to oxidative stress | GO:0006979 | 44 | 0.42 | 1.54 | <.001 |

| Actin filament | GO:0005884 | 16 | 0.58 | 1.54 | <.001 |

| Actin filament organization | GO:0007015 | 24 | 0.42 | 1.52 | <.001 |

| Mitochondrial lumen | GO:0005759 | 40 | 0.51 | 1.51 | <.001 |

| Mitochondrial matrix | GO:0005759 | 40 | 0.51 | 1.51 | <.001 |

| Enriched in Vehicle versus DBP | |||||

| Pattern specification process | GO:0007389 | 29 | −0.57 | −1.59 | <.001 |

| Female gamete generation | GO:0007292 | 16 | −0.63 | −1.54 | <.001 |

| Organelle localization | GO:0051640 | 21 | −0.43 | −1.51 | <.001 |

| Positive regulation of cellular component organization and biogenesis | GO:0051130 | 35 | −0.35 | −1.47 | <.001 |

| Transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling pathway | GO:0007169 | 81 | −0.38 | −1.38 | <.001 |

| Embryonic development | GO:0009790 | 53 | −0.42 | −1.35 | <.001 |

| Enzyme-linked receptor protein signaling pathway | GO:0007167 | 136 | −0.34 | −1.34 | <.001 |

| Cell projection | GO:0042995 | 98 | −0.24 | −1.31 | <.001 |

| Voltage-gated calcium channel activity | GO:0005245 | 18 | −0.48 | −1.27 | <.001 |

Treatments: abiraterone—14 d 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate or vehicle (distilled water with Tween-20) po. DBP—14 d 500mg/kg/d DBP or vehicle (corn oil) po.

Abbreviations: DBP, di-n-butyl phthalate; ES, enrichment score; NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM p value, nominal p value (no post hoc adjustment).

In contrast with the vehicle versus unimplanted comparison, the abiraterone versus vehicle-treated xenograft comparison produced no significant genes after post hoc adjustment for multiple comparisons. At a minimum 1.5 fold change, there were 184 transcript clusters with nominal p < .05 (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Table S2). Changes related to endocrine processes included upregulation of SULT2A1, a sulfotransferase that acts on dehydroepiandrosterone, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, and pregnenolone (Rainey and Nakamura, 2008). TGFB2, MET, and GPR64 were downregulated after abiraterone treatment, indicating a potential negative effect of treatment on tissue proliferation. Abiraterone most notably increased genes in the GO term epigenetic regulation of gene expression, including DICER1, DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, suggesting that abiraterone may affect epigenetic processes.

As with abiraterone, there were no genes with significant q-values after DBP treatment, relative to vehicle, but 134 transcript clusters had fold changes greater than 1.5 and p < .05 (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table S3). These included 2 transcripts for structural genes that may be targets of DBP: CNN1, a component of the actin-myosin structure in smooth muscle, and the myosin light chain peptide MYL7. Functional enrichment analysis indicated that DBP-treated grafts were enriched for genes involved in oxidative stress response, particularly the glutathione metabolism genes GSS, GPX3, and GLRX2, and in actin filament genes including ACTC1, ACTA1, MYO3A, and ACTN2. DBP-treated xenografts had negative enrichment for genes related to organelle localization. These processes could be among those that are altered leading to morphological changes in the human fetal testis after DBP exposure, without effects on testosterone biosynthesis.

Real-time PCR Panel

PCR array analysis identified 5 significantly differentially regulated transcripts (p < .05, paired t test) between vehicle and unimplanted samples (Table 3). Two transcripts were differentially regulated between abiraterone and vehicle (p < .05, paired t test). No significant differences were detected between DBP-treated and vehicle xenografts. Gene expression levels determined by microarray and real-time PCR were highly concordant for 36 of the 40 target genes (ρ = −0.909 between microarray log2 intensity and real-time PCR Ct). The remaining 4 genes—AKR1C3, CYP11B1, ESR2, and KIT—were detected at higher levels by microarray than by PCR. PCR assays for these genes appeared less sensitive than microarrays, and in many cases no expression was detected. The fold changes of significant genes, as determined by either platform, were similar across the board, but statistical significance often differed based on the platform (Table 3). However, this confirms the microarray results, which indicated that gene expression changes related to steroidogenesis are limited following 14-d exposure to abiraterone or DBP.

TABLE 3.

Significant Genes in Real-time PCR Analysis Compared With Microarray

| Gene symbol | Gene ID | Microarray fold change | q | Real-time PCR fold change | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle versus unimplanted | |||||

| AKR1C3 | 8644 | 1.38 | .093 | 1.93 | .011 |

| CYP11B1 | 1584 | 2.72 | .062 | 13.09 | .007 |

| CYP19A1 | 1588 | 8.67 | .045 | 39.41 | .019 |

| ESR2 | 2100 | 0.77 | .130 | 0.55 | .043 |

| FDX1 | 2230 | 2.53 | .044 | 3.02 | .073 |

| KIT | 3815 | 0.50 | .052 | 0.53 | .001 |

| POR | 5447 | 1.69 | .045 | 1.67 | .212 |

| Abiraterone versus vehicle | |||||

| FDX1 | 2230 | 1.20 | .084 | 1.40 | .024 |

| GNRH2 | 2797 | 1.02 | .878 | 1.41 | .023 |

| DBP versus vehicle | |||||

| FSHR | 2492 | 0.68 | .015 | 0.60 | .203 |

Table 3 lists all genes that were included in the PCR panel and were significantly differentially regulated according to the microarray (q<0.05), PCR array (p<0.05), or both. Fold change and p or q are shown in bold where significant. Treatments: abiraterone—14 d 75mg/kg/d abiraterone acetate or vehicle (distilled water with Tween-20) po. DBP—14 d 500mg/kg/d DBP or vehicle (corn oil) po.

Abbreviations: DBP, di-n-butyl phthalate; q, q value determined by limma; p, p value determined by paired t test.

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of an antiandrogenic effect in a human fetal testis xenograft model. In previous studies, exposure of rodent hosts bearing rat fetal testis xenografts to DBP produced antiandrogenic effects, but these effects were not reproduced in hosts bearing human fetal testis xenografts (Heger et al., 2012; Mitchell et al., 2012). Here, our goal was to inhibit testosterone biosynthesis directly in human fetal testis xenografts using abiraterone acetate and to compare with the effects of DBP treatment. This makes for a particularly relevant comparison because both compounds exert their antiandrogenic effects by reducing testosterone, without antagonizing the androgen receptor. As we hypothesized, 500mg/kg/d DBP had no effect on host serum testosterone or androgen-sensitive organ weights in our xenograft model; however, abiraterone acetate treatment dramatically reduced serum testosterone and significantly reduced seminal vesicle and LABC weights (Figs. 2 and 3). This supports the conclusions of Heger et al. (2012) and Mitchell et al. (2012) that human fetal testis xenografts are resistant to the antiandrogenic effects of a high dose of DBP while also confirming the utility of the model for measuring antiandrogenicity.

Dose Selection

Given the limited number of samples available for this study, DBP dose was carefully considered, and 500mg/kg/d DBP was chosen as the best dose for comparison with existing studies in the literature. A dose of 500mg/kg/d DBP reduced accessory sex organ weights in the rat xenograft study by Mitchell et al. (2012) and reduced expression of genes involved in testosterone biosynthesis in the rat xenograft study by Heger et al. (2012). In the rat in vivo, doses of DBP ranging from 100 to 500mg/kg/d during the late gestational period have been sufficient to reduce testicular testosterone (Carruthers and Foster, 2005; Howdeshell et al., 2008; Mahood et al., 2007; Struve et al., 2009) while not resulting in significant fetal mortality (Howdeshell et al., 2008).

The abiraterone acetate dose was selected based on a smaller body of literature. We chose a dose of 75mg/kg/d, 1.5 times the 50mg/kg/d dose that reduced serum testosterone, seminal vesicle, and ventral prostate weight in an adult rat study (Duc et al., 2003) and greater on a per weight basis than the 1000mg/d dose given to human patients in clinical trials (de Bono et al., 2011). This dose proved effective in reducing testosterone in our xenograft model. There was no significant treatment-associated mortality, and no significant effect on host weight (Fig. 3), an important consideration in reproductive toxicology studies. Therefore, we felt this was an informative dose for comparison with DBP and for confirmation that the model is sensitive to compounds that directly reduce testosterone biosynthesis. Importantly, abiraterone acetate can be used as a positive control in future xenograft studies.

Abiraterone Acetate Is Antiandrogenic in Human Fetal Testis

CYP17A1 inhibition by abiraterone has been well characterized (Jarman et al., 1998). In the present study, abiraterone treatment resulted in a dramatic decrease in host serum testosterone and a trend toward increased progesterone (Figs. 2A and B), consistent with CYP17A1 inhibition. However, abiraterone did not significantly affect the intensity or localization of CYP17A1 protein expression (Figs. 1D and E), which might have been expected based on rat data with the CYP17A1 inhibitor prochloraz (Laier et al., 2006). SULT2A1, the product of which is responsible for sulfation of pregnenolone (Rainey and Nakamura, 2008), was upregulated in the present study (Fig. 4C). This could possibly be explained by elevated levels of pregnenolone, the intermediate between cholesterol and progesterone, in the hosts, but this was not measured directly. Abiraterone exposure also resulted in slight upregulation of GNRH2, per PCR (Table 3), which could be a response to low intraxenograft testosterone. Gnrh and Gnrhr appear to have a role in gonad development and early hormone signaling in the rat (Botte et al., 1998).

In addition to antiandrogenic effects, abiraterone appears to have an impact on tissue development and proliferation in the human fetal testis. TGFB2 and MET are downregulated, and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis indicated that transcriptional genes and genes related to cellular morphogenesis were negatively enriched in abiraterone-treated xenografts (Table 2). Perhaps most interesting, abiraterone-treated xenografts were positively enriched for genes involved in epigenetic control of gene expression, including DICER1 and several DNA methyltransferase genes. This indicates that a CYP17A1 inhibitor could alter epigenetic programming in the testis, including the germ line, which undergoes major reprogramming of DNA methylation during fetal development (Reik et al., 2001). Although abiraterone does not have wide environmental distribution, this may be a human health concern for other CYP17A1 inhibitors such as prochloraz.

Effects of DBP in Human Fetal Testis Xenografts

The mechanisms of action of DBP, unlike abiraterone, are not well characterized and appear to differ by species, as indicated in several recent reviews (Albert and Jégou, 2013; Johnson et al., 2012; Scott et al., 2009). In the rat, fetal DBP exposure reduces testosterone biosynthesis, possibly through inhibition of cholesterol transport and a decrease in the expression of several genes coding for testosterone biosynthesis enzymes (Thompson et al., 2004). In the mouse, no such decrease in testicular testosterone is observed following in utero DBP exposure (Gaido et al., 2007). Albert and Jégou (2013) argue that the preponderance of rat studies clearly demonstrate antiandrogenic effects of phthalates in utero, and mouse exposures largely produce a “pro-androgenic” or “norm-androgenic” effect. However, neither species is necessarily predictive of human response. As in previous human fetal testis studies (Heger et al., 2012; Lambrot et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2012), DBP had no effect on androgenic processes in the present study (Figs. 2 and 3). DBP-treated grafts did, however, display a nonsignificant trend toward increased MNGs (Fig. 1, p = .051). This is an expected effect, as DBP treatment increases germ-cell multinucleation in rat, mouse, and human fetal testis (Gaido et al., 2007). DBP-treated xenograft gene expression data showed enrichment for genes related to cell cycle arrest and the actin filament (Table 2). Arrest of normal germ cells and collapse of intercellular bridges may be involved in MNG formation, and there is existing evidence that DBP affects vimentin localization in Sertoli cells (Kleymenova et al., 2005). Therefore, the impact of DBP on these processes reveals possible mechanistic targets that should be the subject of further study. DBP also decreased FSHR mRNA expression (Table 3), which may further suggest Sertoli cell effects of DBP, as expression of FSHR mRNA increases with Sertoli cell number during the second trimester in normal human fetal testis (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2007).

Implications for Human Health Risk Assessment of Phthalates

Human studies comprise a small proportion of the phthalate literature (Albert and Jégou, 2013), but human fetal testis in vitro and xenograft studies have indicated that the human fetal testis differs from the rat in its sensitivity to the antiandrogenic effects of phthalates. DBP has not had significant effects on circulating hormones or organ weights in human fetal testis xenograft studies, despite significant effects in rat xenografts. However, phthalates consistently alter the histology of the seminiferous cord in both in vitro and xenograft studies (Heger et al., 2012; Lambrot et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2012). The testis is susceptible to formation of MNGs following DBP exposure, without changes in androgen levels (Johnson et al., 2012), and these changes in the seminiferous cord could have ramifications for germline health (Saffarini et al., 2012). Ultimately, in order to assess the human health risk posed by in utero exposure to phthalates, additional effort must be made to identify the apparently disparate initiating events leading to the Leydig cell (antiandrogenic) and seminiferous cord effects of phthalates, and to determine the responsiveness of human fetal testis to each of these effects at relevant doses. The TDS hypothesis states that Sertoli and germ cells, in addition to Leydig cells, are potential targets for perturbation of developing testis (Toppari et al., 2010), and so persistent effects on testis could be caused by developmental perturbations of the seminiferous cord as realistically as antiandrogenic effects. Future studies should employ phthalates other than DBP, as well as mixtures of phthalates, which have additive effects in the rat (Howdeshell et al., 2008).

Utility of the Human Fetal Testis Xenograft Model for Testing Antiandrogens

We have confirmed that a xenograft model can be used to detect an antiandrogenic effect in human fetal testis. Additionally, by including ungrafted control mice, we were able to quantify serum testosterone levels in the castrate host, which should largely derive from the host adrenal gland (Albert and Jégou, 2013). Sham testosterone levels were 20%–25% of those in hosts bearing grafts (Fig. 2), and neither treatment significantly affected sham serum hormone levels, suggesting that adrenal testosterone is unlikely to interfere with assessment of xenograft-derived testosterone. Phthalate metabolism and kinetics are concerns that should be fully addressed in future xenograft studies, although metabolism does not appear to differ greatly among species. DBP is metabolized to the active metabolite monobutyl phthalate (MBP) rapidly, and MBP peaks within 2h following a single dose in pregnant mice (Gaido et al., 2007). Similarly, DBP appears to be metabolized rapidly in humans, primarily to MBP (Koch et al., 2012). Human and mouse metabolism of diethylhexyl phthalate does differ but to a lesser degree than interindividual differences among humans (Ito et al., 2013). Windows of susceptibility to antiandrogenic effects are another concern that should be further characterized in the xenograft model. Although this window has been approximated in previous reports, eg, 8–14 weeks gestation in Scott et al. (2009) and 8–12 weeks in Mazaud-Guittot et al. (2013), in the current study, gestational week 16–22 testes were clearly still susceptible to disruption by abiraterone acetate.

In characterizing the effects of the xenograft model on gene expression, we found significant differences between unimplanted testis and vehicle-treated xenografts (Figs. 4A and B, Supplementary Table S1). The large number of differentially regulated genes could be driven by several factors, including the effective 4-week age difference between the unimplanted sample and its matched vehicle-treated xenograft sample, hCG stimulation, or other aspects of the renal subcapsular environment of the athymic nude mouse host. The major steroidogenesis-related changes following xenografting were significant increases in expression of CYP11B1 and CYP19A1. Given that the testis xenografts were stimulated with a high dose of hCG, testosterone levels in the xenografts may have induced aromatase expression. Small noncoding RNAs also appear to have a significant role in either the normal maturation of the testis or the adaptation to the xenograft environment (Supplementary Table S1). Small RNAs with altered expression levels included those with known roles in the testis, including SNORD116 genes (Cassidy et al., 2012) and the LET7 family of microRNAs (Rakoczy et al., 2013). However, it should be cautioned that microRNAs can be packaged and stably transported in circulating blood (Kosaka et al., 2010) and are highly conserved across species, meaning that these microRNAs may not have originated in the xenografts. Also, the RNA preparation procedure used for this experiment is presumed to be size selective for RNAs > 200 nt. Therefore, the roles of these microRNAs in the human fetal testis have not been fully characterized. This would require additional experiments aimed at quantifying small RNAs.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed our hypothesis: in hosts bearing human fetal testis xenografts, abiraterone acetate treatment led to a reduction in testosterone, whereas 500mg/kg/d DBP did not. This result is consistent with several recent findings that human fetal testis is relatively insensitive to direct antiandrogenic actions of DBP but not to the seminiferous cord effects of DBP. We further determined that a Hershberger-like xenograft bioassay can detect antiandrogenic effects in human fetal testis tissue. Humans are exposed to potentially antiandrogenic xenobiotics on a regular basis, including during pregnancy. Based on the available evidence, exposure to antiandrogens in utero can dramatically impair the testosterone-dependent development of the male reproductive tract. Numerous industrial, pharmaceutical, and agricultural compounds have antiandrogenic effects in rodents. In addition to studying these compounds in rodents in utero, antiandrogenic effects can be assessed in human fetal testis directly using a xenograft system.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING

United States Environmental Protection Agency (RD-83459401); National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (R01-ES017272, P20, T32-ES7272 to D.J.S.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are deeply grateful to the parents who consented to participate in this study. They thank Kristen Delayo for coordinating tissue donations, Christoph Schorl for microarray processing, and Melinda Golde and Paula Weston for processing histological samples. They also thank the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction for serum hormone analyses. The University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD/NIH (SCCPIR) Grant U54-HD28934. K. B. does occasional expert consulting with pharmaceutical companies (Akros, Pfizer, Global Alliance for Tb Drug Development, Zafgen). He also owns stock in Exxon-Mobil and Pfizer and in a small start-up biotechnology company (CytoSolv) developing a wound-healing therapeutic.

REFERENCES

- Albert O., Jégou B. (2013). A critical assessment of the endocrine susceptibility of the human testis to phthalates from fetal life to adulthood. Hum Reprod Update. 10.1093/humupd/dmt1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C. L., Jensen J. L., Orntoft T. F. (2004). Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 64, 5245–5250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botte M. C., Chamagne A. M., Carre M. C., Counis R., Kottler M. L. (1998). Fetal expression of GnRH and GnRH receptor genes in rat testis and ovary. J. Endocrinol. 159, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazma A., Hingamp P., Quackenbush J., Sherlock G., Spellman P., Stoeckert C., Aach J., Ansorge W., Ball C. A., Causton H. C., et al. (2001). Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nat. Genet. 29, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers C. M., Foster P. M. (2005). Critical window of male reproductive tract development in rats following gestational exposure to di-n-butyl phthalate. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 74, 277–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho B. S., Irizarry R. A. (2010). A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics 26, 2363–2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S. B., Schwartz S., Miller J. L., Driscoll D. J. (2012). Prader-Willi syndrome. Genet Med. 14, 10–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono J. S., Logothetis C. J., Molina A., Fizazi K., North S., Chu L., Chi K. N., Jones R. J., Goodman O. B., Jr, Saad F., et al. (2011). Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 1995–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Paepe M. E., Chu S., Heger N., Hall S., Mao Q. (2012). Resilience of the human fetal lung following stillbirth: Potential relevance for pulmonary regenerative medicine. Exp. Lung Res. 38, 43–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duc I., Bonnet P., Duranti V., Cardinali S., Riviere A., De Giovanni A., Shields-Botella J., Barcelo G., Adje N., Carniato D., et al. (2003). In vitro and in vivo models for the evaluation of potent inhibitors of male rat 17alpha-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 84, 537–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaido K. W., Hensley J. B., Liu D., Wallace D. G., Borghoff S., Johnson K. J., Hall S. J., Boekelheide K. (2007). Fetal mouse phthalate exposure shows that gonocyte multinucleation is not associated with decreased testicular testosterone. Toxicol. Sci. 97, 491–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray L. E., Jr., Furr J., Ostby J. S. (2005). Hershberger assay to investigate the effects of endocrine-disrupting compounds with androgenic or antiandrogenic activity in castrate-immature male rats. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 26, 16.9.1–16.9.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar S., Ehmer P. B., Barassin S., Batzl-Hartmann C., Hartmann R. W. (2003). Effects of novel 17alpha-hydroxylase/C17, 20-lyase (P450 17, CYP 17) inhibitors on androgen biosynthesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 84, 555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heger N. E., Hall S. J., Sandrof M. A., McDonnell E. V., Hensley J. B., McDowell E. N., Martin K. A., Gaido K. W., Johnson K. J., Boekelheide K. (2012). Human fetal testis xenografts are resistant to phthalate-induced endocrine disruption. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 1137–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdeshell K. L., Wilson V. S., Furr J., Lambright C. R., Rider C. V., Blystone C. R., Hotchkiss A. K., Gray L. E., Jr. (2008). A mixture of five phthalate esters inhibits fetal testicular testosterone production in the sprague-dawley rat in a cumulative, dose-additive manner. Toxicol. Sci. 105, 153–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y., Kamijima M., Hasegawa C., Tagawa M., Kawai T., Miyake M., Hayashi Y., Naito H., Nakajima T. (2013). Species and inter-individual differences in metabolic capacity of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) between human and mouse livers. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 10.1007/s12199-12013-10362-12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman M., Barrie S. E., Llera J. M. (1998). The 16,17-double bond is needed for irreversible inhibition of human cytochrome p45017alpha by abiraterone (17-(3-pyridyl)androsta-5, 16-dien-3beta-ol) and related steroidal inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 41, 5375–5381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. J., Heger N. E., Boekelheide K. (2012). Of mice and men (and rats): Phthalate-induced fetal testis endocrine disruption is species-dependent. Toxicol. Sci. 129, 235–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleymenova E., Swanson C., Boekelheide K., Gaido K. W. (2005). Exposure in utero to di(n-butyl) phthalate alters the vimentin cytoskeleton of fetal rat Sertoli cells and disrupts Sertoli cell-gonocyte contact. Biol. Reprod. 73, 482–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch H. M., Christensen K. L., Harth V., Lorber M., Bruning T. (2012). Di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP) and diisobutyl phthalate (DiBP) metabolism in a human volunteer after single oral doses. Arch. Toxicol. 86, 1829–1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N., Iguchi H., Yoshioka Y., Takeshita F., Matsuki Y., Ochiya T. (2010). Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17442–17452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laier P., Metzdorff S. B., Borch J., Hagen M. L., Hass U., Christiansen S., Axelstad M., Kledal T., Dalgaard M., McKinnell C., et al. (2006). Mechanisms of action underlying the antiandrogenic effects of the fungicide prochloraz. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 213, 160–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrot R., Muczynski V., Lecureuil C., Angenard G., Coffigny H., Pairault C., Moison D., Frydman R., Habert R., Rouiller-Fabre V. (2009). Phthalates impair germ cell development in the human fetal testis in vitro without change in testosterone production. Environ. Health Perspect. 117, 32–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leek J. T., Johnson W. E., Parker H. S., Jaffe A. E., Storey J. D. (2012). The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 882–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A. (2013). hugene10sttranscriptcluster.db: Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0-ST Array Transcriptcluster Revision 8 annotation data (chip hugene10sttranscriptcluster), R package version 8.0.1. Available at: http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/hugene10sttranscriptcluster.db.html

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottrup G., Andersson A. M., Leffers H., Mortensen G. K., Toppari J., Skakkebaek N. E., Main K. M. (2006). Possible impact of phthalates on infant reproductive health. Int. J. Androl. 29, 172–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahood I. K., Scott H. M., Brown R., Hallmark N., Walker M., Sharpe R. M. (2007). In utero exposure to di(n-butyl) phthalate and testicular dysgenesis: Comparison of fetal and adult end points and their dose sensitivity. Environ. Health Perspect. 115(Suppl. 1), 55–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazaud-Guittot S., Nicolaz C. N., Desdoits-Lethimonier C., Coiffec I., Maamar M. B., Balaguer P., Kristensen D. M., Chevrier C., Lavoue V., Poulain P., et al. (2013). Paracetamol, aspirin and indomethacin induce endocrine disturbances in the human fetal testis capable of interfering with testicular descent. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 10.1210/jc.2013–2531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. L., Auchus R. J. (2011). The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev 32, 81–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R. T., Childs A. J., Anderson R. A., van den Driesche S., Saunders P. T., McKinnell C., Wallace W. H., Kelnar C. J., Sharpe R. M. (2012). Do phthalates affect steroidogenesis by the human fetal testis? Exposure of human fetal testis xenografts to di-n-butyl phthalate. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, E341–E–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit J. S., Her L. S., Mineo A. M., Knight B. L., Phillips J. A., Thibodeau M. S. (2013). Assessment of inhibin B as a biomarker of testicular injury following administration of carbendazim, cetrorelix, or 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane in wistar han rats. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 98, 17–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shaughnessy P. J., Baker P. J., Monteiro A., Cassie S., Bhattacharya S., Fowler P. A. (2007). Developmental changes in human fetal testicular cell numbers and messenger ribonucleic acid levels during the second trimester. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92, 4792–4801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W., Tichopad A., Prgomet C., Neuvians T. P. (2004). Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 26, 509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2012). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [Google Scholar]

- Rainey W. E., Nakamura Y. (2008). Regulation of the adrenal androgen biosynthesis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 108, 281–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy J., Fernandez-Valverde S. L., Glazov E. A., Wainwright E. N., Sato T., Takada S., Combes A. N., Korbie D. J., Miller D., Grimmond S. M., et al. (2013). MicroRNAs-140-5p/140-3p modulate Leydig cell numbers in the developing mouse testis. Biol. Reprod. 88, 143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich M., Liefeld T., Gould J., Lerner J., Tamayo P., Mesirov J. P. (2006). GenePattern 2.0. Nat. Genet. 38, 500–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reik W., Dean W., Walter J. (2001). Epigenetic reprogramming in mammalian development. Science 293, 1089–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider C. V., Furr J., Wilson V. S., Gray L. E., Jr. (2008). A mixture of seven antiandrogens induces reproductive malformations in rats. Int. J. Androl. 31, 249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffarini C. M., Heger N. E., Yamasaki H., Liu T., Hall S. J., Boekelheide K. (2012). Induction and persistence of abnormal testicular germ cells following gestational exposure to di-(n-butyl) phthalate in p53-null mice. J. Androl. 33, 505–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott H. M., Mason J. I., Sharpe R. M. (2009). Steroidogenesis in the fetal testis and its susceptibility to disruption by exogenous compounds. Endocr. Rev. 30, 883–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth G. (2005). Limma: Linear models for microarray data. In Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor (Gentleman R., Carey V., Dudoit S., Irizarry R. A., Huber W., Eds.), pp. 397–420 Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Struve M. F., Gaido K. W., Hensley J. B., Lehmann K. P., Ross S. M., Sochaski M. A., Willson G. A., Dorman D. C. (2009). Reproductive toxicity and pharmacokinetics of di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) following dietary exposure of pregnant rats. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 86, 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S. L., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., et al. (2005). Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.102, 15545–15550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. J., Ross S. M., Gaido K. W. (2004). Di(n-butyl) phthalate impairs cholesterol transport and steroidogenesis in the fetal rat testis through a rapid and reversible mechanism. Endocrinology 145, 1227–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppari J., Virtanen H. E., Main K. M., Skakkebaek N. E. (2010). Cryptorchidism and hypospadias as a sign of testicular dysgenesis syndrome (TDS): Environmental connection. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 88, 910–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unni S. K., Modi D. N., Pathak S. G., Dhabalia J. V., Bhartiya D. (2009). Stage-specific localization and expression of c-kit in the adult human testis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 861–869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.