Abstract

The zinc finger transcription factor ThPOK plays a crucial role in CD4 T-cell development and CD4/CD8 lineage decision. In ThPOK-deficient mice, developing T cells expressing MHC class II-restricted T-cell receptors are redirected into the CD8 T-cell lineage. In this study, we investigated whether the ThPOK transgene affected the development and function of two additional types of T cells, namely self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Self-specific CD8 T cells are characterized by high expression of CD44, CD122, Ly6C, 1B11 and proliferation in response to either IL-2 or IL-15. The ThPOK transgene converted these self-specific CD8 T cells into CD4 T cells. The converted CD4+ T cells are no longer self-reactive, lose the characteristics of self-specific CD8 T cells, acquire the properties of conventional CD4 T cells and survive poorly in peripheral lymphoid organs. By contrast, the ThPOK transgene promoted the development of CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells resulting in an increased recovery of CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells that expressed higher transforming growth factor-β-dependent suppressor activity. These studies indicate that the ThPOK transcription factor differentially affects the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells.

Keywords: forkhead box protein 3, regulatory T cells, self-specific CD8 T cells, ThPOK

Introduction

The mature T-cell population is divided into two main lineages that are defined by the expression of CD4 and CD8 surface molecules. CD8+ T cells are restricted by MHC I molecules and possess cytotoxic activity by virtue of the expression of molecules such as perforin and granzyme.1 By contrast, CD4+ T cells are restricted by MHC II molecules and either provide help or suppress other immune cells through either cytokine secretion and/or expression of specific cell surface molecules.1 During T-cell development the strength and duration of T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling play key roles in CD4/CD8 lineage choice.2 In addition to TCR signalling, a number of transcription factors have recently been shown to play important roles in CD4/CD8 lineage choice. These transcription factors include the Runx family member Runx3,3 the zinc finger protein ThPOK (also called cKrox)4,5 and Gata-3.6,7 Runx3 is up-regulated in developing thymocytes that are committed to the CD8 T-cell lineage and promotes the termination of CD4 expression.4,8 By contrast, ThPOK and Gata-3 are up-regulated in developing thymocytes that are committed to the CD4+ T-cell lineage.4,5,9 Notably, the loss of ThPOK function redirects developing T cells that express MHC II-restricted TCRs into the CD8 T-cell lineage, whereas constitutive ThPOK expression redirects developing T cells that express MHC I-restricted TCRs into the CD4 T-cell lineage.4,5 By contrast, although constitutive Gata-3 expression promotes the development of CD4+ T cells, it does not redirect developing thymocytes that express MHC class I-restricted TCRs into the CD4 T-cell lineage.10 These observations provide a novel insight regarding the relative roles of ThPOK and Gata-3 in CD4 lineage choice, with ThPOK playing a pivotal role in this process.

During T-cell development in the thymus, immature T cells that express TCRs with high affinity for self antigens are deleted by a process referred to as negative selection. In TCR transgenic mice that express a male-specific TCR (H-Y TCR), negative selection of developing thymocytes that express the H-Y TCR leads to the massive deletion of double-positive thymocytes.11 Interestingly, in male H-Y TCR transgenic mice, in spite of this negative selection process, a population of CD8+ T cells that express the self-reactive H-Y TCR was able to develop.12 However, these self-reactive CD8+ T cells differ from conventional CD8+ T cells in many aspects. They express a lower level of cell-surface CD8 and possess a memory phenotype as exemplified by high expression of CD44, CD122 and Ly6C.12,13 These self-specific CD8 T cells were able to proliferate in response to interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-15 in the absence of TCR stimulation.14,15 Furthermore, when cultured in IL-2, they dramatically up-regulate NKG2D expression and participate in the killing of syngeneic tumours, particularly those that expressed NKG2D ligands.15 These self-specific CD8 T cells are not an oddity of TCR transgenic mice because they represent ˜ 10% of all CD8+ T cells in normal mice.15,16 They possess innate-like properties, due in part to their rapid production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in response to bacterial infection and serve as a critical source of IFN-γ in the defence against bacterial infections.14,15 Furthermore, unlike conventional CD8 T cells, these self-specific CD8 T cells are not dependent on RasGRP117 and Tec kinases18–20 for their development but instead are dependent on high-affinity interaction with self antigen14 and IL-1518,20,21 for their development. High-affinity interactions with self antigen appear to be a common feature for the development of various regulatory cell types, including CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells22 and T helper type 17 cells.23

CD4 Treg cells comprise between 5 and 10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells and play a critical role in the maintenance of peripheral tolerance by suppressing immune responses to self antigens.24,25 They also regulate immune responses to foreign antigens and tumour antigens.26–28 The forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) is a transcription factor that is expressed by CD4+ CD25+ T cells in mice and humans.29–31 FoxP3 is required for the development, maintenance and function of Treg cells.29–31 Treg cells that have lost FoxP3 were implicated in the induction of autoimmune diseases, further suggesting that these cells express high-affinity TCRs for self antigens and loss of FoxP3 converts them from suppressors to pathogenic effector T cells.29–31 Various mechanisms have been proposed for the suppressor function of Treg cells: suppression may occur through the secretion of suppressor cytokines [transforming growth factor (TGF-β), IL-10 and IL-35),32–34 competition for IL-2,35 expression of suppressor molecules (galectin-1) on their cell surface,36 and the killing of effector T cells.37

Previous studies have shown that expression of the ThPOK transgene in developing T cells led to the redirection of developing thymocytes that express MHC class I-restricted TCRs into the CD4 T-cell lineage.4,5 Furthermore, transduction of ThPOK into mature CD8 T cells inhibits their expression of CD8, cytotoxic effector genes and promotes expression of helper-specific genes, although not of CD4 itself.38 The development of conventional CD8+ T cells is dependent on low-affinity interactions between the TCR on immature CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes with positively selecting ligands.1 In contrast, the development of self-specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ Treg cells is dependent on high-affinity interactions between the TCR on developing thymocytes and self ligands.14,22 It is therefore of interest to determine whether the ThPOK transgene affects the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4 Treg cells in a manner that is either similar to or distinct from its effect on conventional CD8 T cells. Our data indicated that the ThPOK transgene converted self-specific CD8 T cells into CD4+ CD8− T cells with the characteristics of conventional CD4+ T cells. By contrast, the ThPOK transgene was unable to convert Treg cells into T helper cells and instead promoted the development and suppressor function of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells. These studies indicate that the CD4 lineage-specific transcription factor, ThPOK differentially affects the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

B6 mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). H-Y TCR transgenic mice were produced as previously described.39 Breeders for mice expressing the ThPOK transgene under the control of the human CD2 promoter5 were kindly provided by Dr Remy Bosselut (Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Breeders for the FoxP3-DTR mice were kindly provided by Dr Alexander Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). The targeting construct for the FoxP3-DTR mice limits the expression of both the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) and green fluorescent protein (GFP) to FoxP3+ cells.40 H-Y mice with the ThPOK transgene were produced by mating female homozygous H-Y TCR transgenic mice with male mice that expressed the ThPOK transgene and typing for the ThPOK transgene by PCR. ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were obtained by mating homozygous female FoxP3-DTR mice with male ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice and typing for the ThPOK transgene by PCR. Mice aged 8–12 weeks were used for the experiments described in this study. The mice were housed in the Wesbrook Animal Unit, Department of Microbiology and Immunology. Animal studies were performed according to guidelines established by the Canadian Council of Animal Care and approved by our institutional review board.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions from lymph nodes, spleens or thymus were subjected to red blood cell lysis. All incubations were performed in FACS buffer on ice for 15 min. Antibodies against CD4, CD8, H-Y TCR, CD44, CD122, Ly6C, 1B11, 2B4, CD94, DX5, NKG2D, granzyme B, IFN-γ, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), CD25, CTLA-4, GITR, FoxP3, Gata-3, IL-4, IL-10 and mouse, rat, Armenian Hamster IgG isotype control antibodies, were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Antibodies against TGF-β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). For intracellular staining of cytokines, GolgiPlug™ (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was added to block cytokine secretion before activation. The activated cells were fixed, permeabilized with a FoxP3 staining buffer set (eBioscience) following the manufacturer's protocols and subsequently stained and analysed by FACS. The FACS analyses were performed using either the FACScan or LSRII (BD Biosciences) flow cytometers.

CFSE labelling

Purified CD8lo or CD4+ cells (107/ml) from H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice were labelled with 1 μm carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After stopping the reaction by adding an equal amount of FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), cells were washed four times with complete medium before use.

Proliferation assays

CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y TCR mice, CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male ThPOK H-Y mice, were purified by cell sorting with the FACSAria flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with purities over 95%. For H-Y peptide stimulation, the purified cells were labelled with CFSE and stimulated with 5 × 105 mitomycin C (50 μg/ml) -treated antigen-presenting cells from female B6 mice and the indicated concentration of H-Y peptide14 in a 96-well U-bottom plate. CFSE measurements were assessed by FACS at 72 and 90 hr. For concanavalin A activation, sorted CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y TCR mice and H-Y ThPOK mice, respectively, were labelled with CFSE and stimulated with concanavalin A (2 μg/ml) for 48 and 60 hr. For IL-2 and IL-15 stimulation, purified cells were labelled with CFSE and stimulated with either IL-2 (200 U/ml) or IL-15 (100 ng/ml) for 72 and 96 hr and CFSE dilutions were assessed by FACS. In some experiments, 5 μg/ml isotype control antibody or anti-CD122 (eBioscience) were added to the cultures as indicated.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells from B6 mice, CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y TCR mice, CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y ThPOK mice, CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were all purified by cell sorting with the FACSAria flow cytometer with purities over 95%. The purified cells were activated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hr. RNA isolation and first-strand cDNA syntheses were prepared using the RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and M-MuLV First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (BioLab, Ipswich, WA) following the manufacturer's protocols. The indicated transcripts in the cDNA samples were quantified using TaqMan gene expression assay kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with β2-microglobulin (Mm00437762_m1), granzyme B (Mm00442834_m1), IFN-γ (Mm01168134_m1), Eomes (MM01351985_m1), Gata-3 (Mm0048463_m1), IL-4 (Mm00445259_m1), IL-10 (Mm00439614_m1), TGF-β1 (Mm01178820_m1) and IL-2 (Mm00434256_m1) as primers and probes. Quantitative PCR was performed in triplicates using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) chemistry in 20-μl reactions composed of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), cDNA template and PCR probe set for individual genes, as described above. For each target, PCR amplification was performed and detected with a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). To analyse the relative transcripts we used the comparative Ct method, also referred as the ΔΔCt method.41 The relative fold of each test group to the control group is given by the arithmetic formula  . For each sample, the cycle threshold (Ct) values for β2-microglobulin and other genes of interest were determined and values obtained with β2-microglobulin were used for normalization. The ΔCt values are subtraction of the average β2-microglobulin Ct value from the average gene of interest Ct value, and the ΔΔCt values are the subtraction of test group from the control group. Relative transcript expression for each gene is depicted as

. For each sample, the cycle threshold (Ct) values for β2-microglobulin and other genes of interest were determined and values obtained with β2-microglobulin were used for normalization. The ΔCt values are subtraction of the average β2-microglobulin Ct value from the average gene of interest Ct value, and the ΔΔCt values are the subtraction of test group from the control group. Relative transcript expression for each gene is depicted as  . For example, if the ΔΔCt value of the control group is 0, the relative fold to itself is 1 (according to

. For example, if the ΔΔCt value of the control group is 0, the relative fold to itself is 1 (according to  ). If the ΔΔCt value of test group is 2, the relative fold to control group is 0·25.

). If the ΔΔCt value of test group is 2, the relative fold to control group is 0·25.

Suppressor assay

CD4+ FoxP3+ cells and CD4+ FoxP3− cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice were purified by cell sorting with the FACSAria flow cytometer with purities over 95%. The suppressor assay was performed using 2 × 104 CD4+ FoxP3− cells as responders, 2 × 105 mitomycin C (50 μg/ml) treated antigen-presenting cells as stimulators and the indicated number of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells as suppressors in 200 μl media with anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) in a U-bottom 96-well plate. During the last 8 hr of the 3-day incubation period 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) was added to each well. In some experiments, 4 μg/ml of neutralizing TGF-β antibodies (R&D Systems) or 4 μg/ml mouse IgG1 control antibodies (eBioscience) were added at the beginning of the 3-day incubation. All data are shown as mean [3H]thymidine incorporation of triplicate cultures.

Results

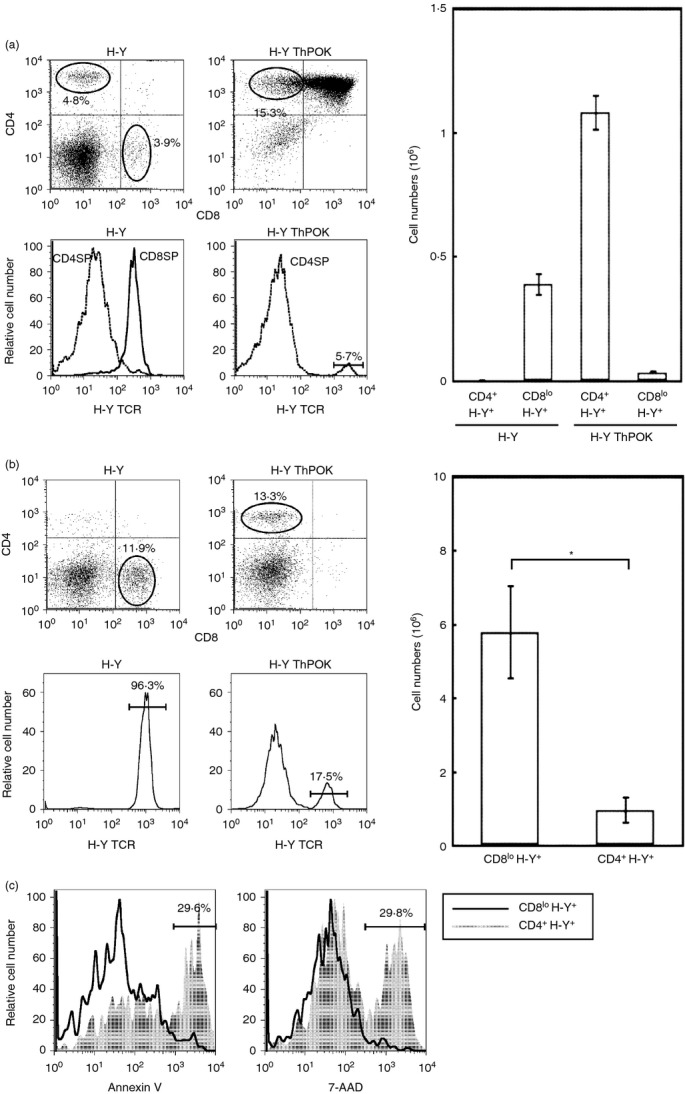

The ThPOK transgene converted self-specific CD8lo cells into CD4+ CD8− cells

In normal mice, the ThPOK transgene redirected the development of conventional MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T cells into the CD4+ T-cell lineage. To determine whether the ThPOK transgene can also redirect self-specific CD8 cells into the CD4+ T-cell lineage, we produced male H-Y TCR transgenic mice that expressed the ThPOK transgene. The total thymocyte numbers of male H-Y and ThPOK H-Y mice were 8·3 × 106 and 1·5 × 108, respectively. Staining of thymocytes from male H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice indicated that the development of CD8lo cells in male ThPOK H-Y mice was abrogated (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, there is a large population of CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes in male H-Y ThPOK mice and 18 times more thymocytes were recovered from male H-Y ThPOK mice compared with male H-Y mice. The high recovery of CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes in male H-Y ThPOK mice was at least in part due to the down-regulation of the H-Y TCR and CD8 by these cells (see Supplementary material, Fig. 1). Three-colour staining revealed that only 5·7% of the CD4+ CD8− thymocytes from male H-Y ThPOK mice expressed a high level of the H-Y TCR (Fig. 1a). Despite the low percentage of H-Y+ cells in the CD4+ CD8− population, a total of 1·3 × 106 CD4+ CD8− H-Y+ thymocytes was recovered from male ThPOK H-Y mice compared with 0·4 × 106 CD4−CD8lo thymocytes recovered from male H-Y mice. This indicated that the conversion of CD4−CD8lo H-Y TCR+ to CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ by the ThPOK transgene is highly efficient.

Figure 1.

The ThPOK transgene converts CD8lo cells into CD4+ CD8− cells. (a) The dot plots depict CD4 and CD8 profiles of thymus from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice. The circles in the dot plots indicate the gates for CD8SP or CD4SP cells. The histograms depict the expression of H-Y TCR by gated CD8SP or CD4SP cells from H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively. The numbers in the dot plots and histograms indicate the percentages of gated cells. The bar graphs depict the mean numbers of the indicated cell types recovered from male H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice. (b) The dot plots depict CD4 and CD8 profiles of lymph node cells from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice. The circles in the dot plots indicate the gates for CD8lo or CD4+ cells. The histograms depict the expression of H-Y TCR by gated CD8lo or CD4+ cells from H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively. The * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. (c) The histograms depict levels of annexin V and 7-AAD staining by gated CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

We also determined the recovery of CD4− CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells from the lymph nodes of male H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice. In contrast to the thymus, significantly fewer CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells were recovered from the lymph nodes of male H-Y ThPOK mice compared with the CD4− CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells recovered from male H-Y lymph nodes (Fig. 1b). Staining of CD4− CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells with either annexin V or 7-AAD revealed that ˜ 30% of CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells were highly stained with either annexin V or 7-AAD, indicating that the CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells have a survival disadvantage compared with CD4− CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells (Fig. 1c). Similar results were observed for splenic CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells (data not shown). This poorer survival probably contributed to the low recovery of CD4+ CD8− H-Y TCR+ cells from the peripheral lymphoid organs of male ThPOK H-Y lymph nodes.

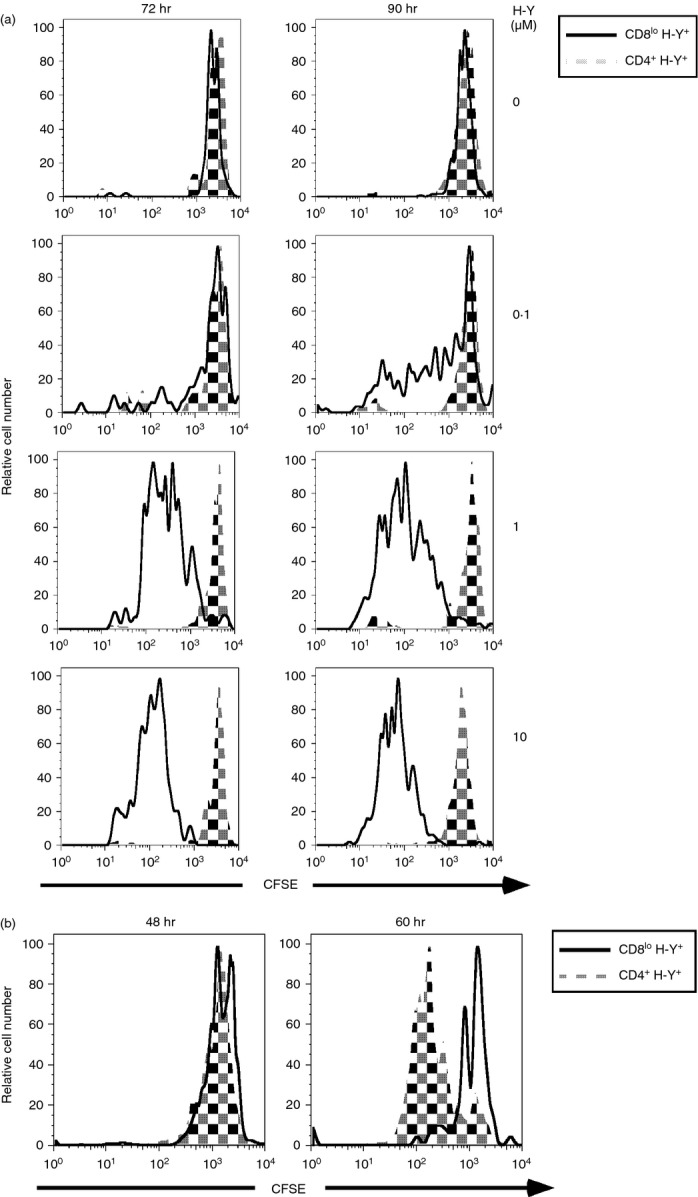

Converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells are not activated by the male antigen

Since the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells express the wrong co-receptor we determined the effect on the expression of the wrong co-receptor on their ability to be activated by the male antigen. CFSE-labelled CD8lo H-Y TCR+ T cells or CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells from male H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice respectively were stimulated with mitomycin C-treated female B6 spleen cells with various concentrations of the H-Y peptide.14 Whereas the CD8lo H-Y TCR+ T cells proliferated vigorously in response to the male peptide, the CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells were not male-responsive, even at high peptide concentrations (Fig. 2a). However, the CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells are not functionally inert because they proliferated to a greater extent than the CD8lo H-Y TCR+ T cells when activated for 60 hr by the T-cell mitogen, concanavalin A (Fig. 2b). These results indicate that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells are no longer responsive to the male antigen.

Figure 2.

Converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells are not activated by male antigen. (a) Sorted CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice were labelled with CFSE and cultured with mitomycin C treated spleen cells from B6 female mice with the indicated concentration of H-Y peptide. Cells were analysed by FACS at 72 and 90 hr. (b) Sorted CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice were labelled with CFSE and activated with concanavalin A (2 μg/ml) for 48 and 60 hr. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Converted self-specific CD8lo T cells lost their cell-surface and functional properties and acquired helper characteristics

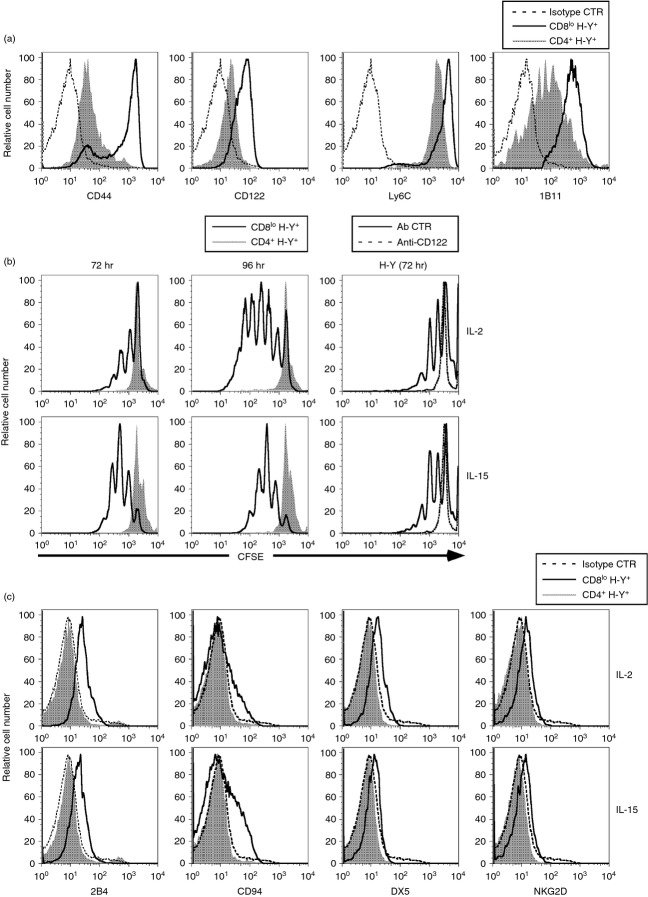

Self-specific CD8 T cells expressed high levels of CD44, CD122, Ly6C and 1B11.14 We found that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells express much lower levels of CD44, CD122, Ly6C and 1B11 when compared with CD8lo H-Y TCR+ T cells, indicating that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells lost memory markers that were characteristic of self-specific CD8lo cells (Fig. 3a). We have shown previously that the CD8lo cells from male H-Y mice proliferated vigorously in response to either IL-2 or IL-15. We determined whether the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells retained this ability to be stimulated by IL-2 or IL-15. Purified CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells were labelled with CFSE before stimulation with either IL-2 or IL-15 and reduction in CFSE labelling after 72 or 96 hr of culture was used as a measure of proliferation. These results indicate that while the CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells proliferated well when stimulated with either IL-2 or IL-15, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells proliferated very poorly after either 72 or 96 hr of culture in either IL-2 or IL-15 (Fig. 3b). The lack of response to either IL-2 or IL-15 by CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells is probably a result of the lower levels of CD122 (IL-2 receptor β-chain) that are expressed by these cells (Fig. 3a). This notion is confirmed by the observation that either IL-2-induced or IL-15-induced proliferation of CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells was completely abrogated by the addition of a neutralizing anti-CD122 antibody (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells lost expression of cell surface molecules characteristic of self-specific CD8 T cells and do not respond to either interleukin-2 (IL-2) or IL-15. (a) The histograms depict expression of the indicated cell surface molecules by gated CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively. The fluorescence-conjugated rat IgG1 control antibodies were used to show the basal level as indicated. (b) Purified CD8lo and CD4+ cells from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively, were labelled with CFSE and cultured with either 200 U/ml IL-2 (upper row) or 100 ng/ml IL-15 (lower row). Proliferation of gated CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells were analysed by FACS at 72 and 96 hr. In the blocking experiments, CFSE-labelled CD8lo H-Y TCR+ cells were activated with IL-2 (upper row) or IL-15 (lower row) with isotype control antibody or anti-CD122 for 72 hr (right column). (c) Purified CD8lo and CD4+ cells from male H-Y TCR and H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice, respectively, were cultured with either 200 U/ml IL-2 (upper row) or 100 ng/ml IL-15 (lower row). The histograms represent the expression of the indicated cell surface molecule by gated CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells after 3 days of culture. The isotype control antibodies were used as indicated. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Another characteristic of self-specific CD8lo cells is that they expressed elevated natural killer (NK) cell markers after activation with either IL-2 or IL-15.14 Consistent with their low proliferative response to these cytokines, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells did not express NK cell surface markers (2B4, CD94, DX5 and NKG2D) after stimulation with either IL-2 or IL-15 (Fig. 3c).

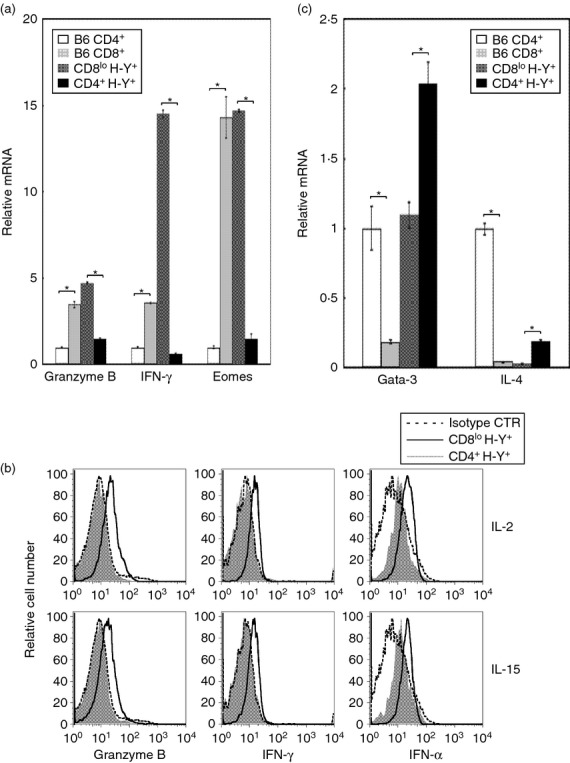

To further characterize the effect of the ThPOK transgene on the function of self-specific CD8lo T cells we determine whether production of transcripts that are indicative of these cells after PMA + ionomycin stimulation is affected by the ThPOK transgene. We have previously shown that activated CD8lo cells were efficient producers of IFN-γ and possess killer activity.14 As shown in Fig. 4(a), PMA + ionomycin-activated CD8lo H-Y TCR+ T cells expressed high levels of transcripts for granzyme B, IFN-γ and the CD8+ T-cell-specific T box transcription factor, Eomesodermin (Eomes).42 It is noted that the activated CD8lo cells expressed similar levels of transcripts for granzyme B and Eomes compared with CD8+ T cells from normal mice. However, CD8lo cells differed from normal CD8+ T cells by expressing a much higher level of transcripts for IFN-γ (Fig. 4a). Notably, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells, which lost memory markers, expressed very low levels of transcripts for granzyme B, IFN-γ and Eomes and these low levels were similar to those expressed by activated CD4+ T cells from normal mice (Fig. 4a). The low levels of transcripts for granzyme B and IFN-γ also corresponded with the much lower levels of proteins expressed by these cells, as determined by intracellular staining (Fig. 4b). We have previously shown that activated CD8lo cells were efficient producers of TNF-α.43 Here, we show that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells produced significantly less TNF-α after PMA + ionomycin activation relative to CD8lo T cells (Fig. 4b). These results indicate that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells were unable to express transcripts that were indicative of self-specific CD8lo cells after PMA + ionomycin activation.

Figure 4.

Repression of CD8+ T-cell-specific genes and expression of CD4+ T-cell-specific genes by converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells. (a) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were purified from B6 mice. CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells were purified from male H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice, respectively. The purified cells were activated with PMA + ionomycin for 4 hr. The bar graphs depict expression of the indicated transcripts by the indicated type of activated T cells. The expression level of individual transcript is compared with the expression level by activated CD4+ cells from B6 mice (arbitrarily set to 1 for each gene). All PCR were performed in triplicates and the SD of these measurements are shown. * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. (b) Purified CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells from H-Y and H-Y ThPOK mice, respectively, were cultured with either interleukin-2 (IL-2) or IL-15 for 72 hr. The histograms indicate the expression of the indicated intracellular protein by the cultured cells. The isotype control antibodies were used as indicated. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (c) The bar graphs depict the relative expression of indicated transcripts by activated CD4+ cells and CD8+ cells from B6 mice and CD8lo H-Y TCR+ and CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from H-Y TCR and ThPOK H-Y transgenic mice, respectively. The level of transcript expression for Gata-3 and IL-4 by activated CD4+ T cells from B6 mice is arbitrarily set to 1. All PCR were performed in triplicates and the SD of these measurements are shown. The * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. Results are representative of three experiments.

We next determined whether the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells expressed transcripts that were specific for conventional CD4+ T cells after PMA + ionomycin activation. Gata-3 is a transcription factor that is required for the development of CD4+ T cells and is expressed at a high level in CD4+ T cells following activation.7,9 Similarly, IL-4 transcripts are produced at high levels by activated CD4+ cells but not CD8+ T cells. We found that the CD8lo cells differ from normal CD8+ T cells by expressing high levels of Gata-3 transcripts after activation (Fig. 4c). This level was as high as that observed for conventional CD4+ T cells. Interestingly, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells express significantly higher levels of Gata-3 transcripts relative to similarly activated CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4c). Similar to normal CD8+ T cells, the CD8lo cells do not express IL-4 transcripts after activation. However, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells produced a significantly higher level of IL-4 transcripts relative to CD8lo cells after activation. The converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells produced much lower levels of IL-4 transcripts compared with similarly activated normal CD4+ T cells. In summary, although there are differences between the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells and normal CD4+ T cells, it is clear that the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ T cells are able to produce transcripts that are specific for the CD4+ T-cell lineage after activation.

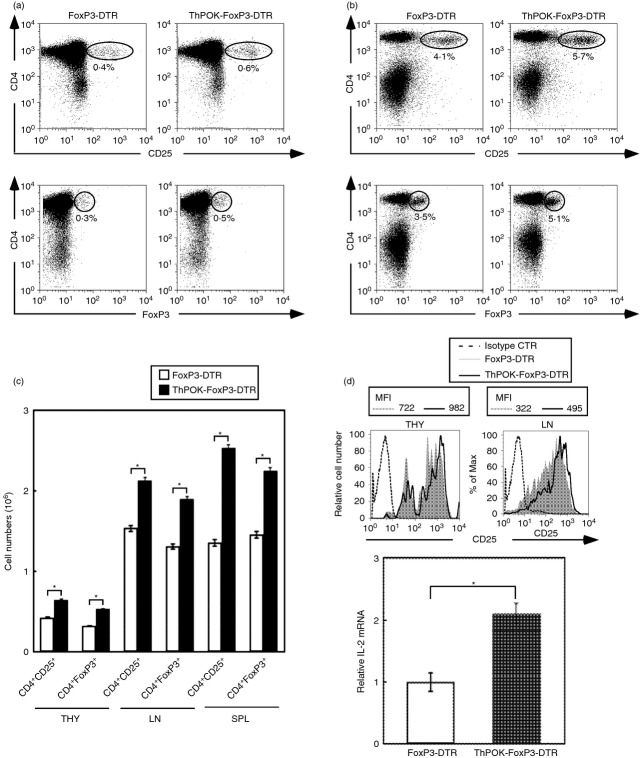

Increased recovery of CD4+ Treg cell from ThPOK transgenic mice

We next determined whether the ThPOK transgene affected the development and function of CD4 Treg cells. FoxP3 is a definitive marker for Treg cells. However, FoxP3 is an intracellular molecule and not detectable directly by FACS. We therefore used FoxP3-DTR mice to monitor FoxP3 expression by CD4 Treg cells. In these mice, expression of both human DTR and GFP is limited to FoxP3+ cells.40 In this way, FoxP3+ cells can be detected directly by FACS without the necessity to stain for FoxP3 intracellularly. We found that the percentages of CD4+ CD25+ as well as CD4+ FoxP3+ cells in the thymus (Fig. 5a) and lymph nodes (Fig. 5b) of ThPOK transgenic mice were significantly increased relative to normal mice. This increase in percentages translated to a significantly higher recovery of CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from the thymus, lymph node and spleen of ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice relative to FoxP3-DTR mice (Fig. 5c). The CD4+ FoxP3+ cells recovered from ThPOK transgenic mice expressed slightly higher levels of CD25. Thymocytes and lymph node cells from ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice expressed slightly higher levels of CD25 relative to those from FoxP3-DTR mice (mean fluorescence intensity of 982 versus 722 for thymocytes and 495 versus 322 for lymph node cells; Fig. 5d). Furthermore, PMA + ionomycin activated CD4+ Foxp3+ cells from ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice expressed significantly higher levels of IL-2 mRNA compared with those from FoxP3-DTR mice (Fig. 5d). As the development of CD4+ Treg cells is dependent on interactions of IL-2 with the high affinity IL-2 receptor,44 the higher expression of CD25 by thymocytes and lymph node cells and the more efficient induction of IL-2 mRNA in activated CD4+ Foxp3+ cells from ThPOK transgenic mice probably contributed to the more efficient development of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells in ThPOK transgenic mice.

Figure 5.

Increased recovery of CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells from ThPOK transgenic mice. The dot plots depict the expression of CD4 and CD25 (upper row) and CD4 and FoxP3 (lower row) by thymocytes (a) and lymph node cells (b) from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice. The numbers in the dot plots indicate percentages of the indicated populations. (c) The bar graphs depict the mean numbers ± SD of CD4+ CD25+ and CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells recovered from the thymus, lymph nodes and spleens of FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice. The * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. (d) The histograms indicate expression of CD25 by CD4+ FoxP3+ cells of thymus and lymph nodes from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice. The mean fluorescence intensities of CD25 expressed by thmocytes and lymph node cells from FoxP3-DTR or ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice are indicated. The bar graphs depict the relative interleukin-2 (IL-2) transcripts of PMA + ionomycin-activated CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells of lymph nodes from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice. The rat IgG2 isotype control antibodies were used as indicated. The * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. Results are representative of three experiments.

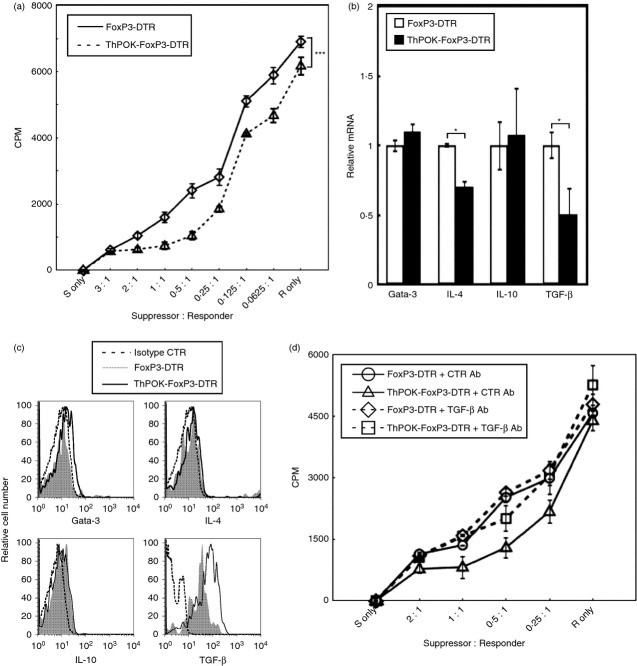

The CD4+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice possess higher suppressor activity

We next determined whether the function of CD4+ Treg cells is affected by the ThPOK transgene. To determine the suppressor activity of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from normal or ThPOK transgenic mice, these cells were purified from FoxP3-DTR mice with or without the ThPOK transgene and their suppressor activity was determined by co-culturing with CD4+ Foxp3− T cells at various suppressor to responder ratios as previously described.17 We found that relative to CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR mice, CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were significantly more suppressive than those from FoxP3-DTR mice at various ratios of suppressor to responder cells in this suppressor assay (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

The CD4+ FoxP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells from ThPOK transgenic mice expressed higher transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) -dependent suppressor activity. (a) Sorted CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were cultured with sorted CD4+ FoxP3− cells from FoxP3-DTR mice and mitomycin C-treated antigen-presenting cells from B6 mice for 72 hr. [3H]Thymidine (1 μCi per well) was added to the cultures for the final 8 hr. The x-axis indicates the ratio of CD4+ FoxP3+ (suppressor) cells to CD4+ FoxP3− (responder) cells. Data points indicate mean [3H]thymidine incorporation of triplicate cultures. The *** indicates P < 0·001; paired t-test. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (b) The bar graphs represent the relative transcript level of Gata-3, interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-10 and TGF-β expressed by activated CD4+ PoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice by real-time PCR. Gene expression by activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR mice was arbitrarily set to 1 for each gene. The values shown are the mean ± SD of triplicate assays. The * indicates P < 0·05; two-tailed t-test. Results are representative of three experiments. (c) The histograms depict the expression of the indicated cytokines by gated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR transgenic mice. The isotype control antibodies were used as indicated. Results are representative of three separate experiments. (d) Sorted CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were cultured with CD4+ FoxP3− cells and mitomycin C-treated antigen-presenting cells from for 72 hr with 4 μg/ml of either control or neutralizing anti-TGF-β antibodies. [3H]Thymidine was added to the cultures for the final 8 hr. Individual data points represent mean [3H]thymidine incorporation ± SD of triplicate cultures. Results are representative of three experiments.

We next determined the effect of the ThPOK transgene on the production of transcripts that are specific for CD4+ T helper (Gata-3 and IL-4) and CD4+ Treg cells (IL-10 and TGF-β) by PMA + ionomycin-activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells. We found that the production of Gata-3 and IL-10 transcripts by activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells was not significantly affected by the ThPOK transgene (Fig. 6b). However, the production of IL-4 and TGF-β transcripts by activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK transgenic mice was significantly lower (Fig. 6b). The low transcript levels for TGF-β were a surprising result in view of the higher suppressor activity observed for CD4+ FoxP3+ cells recovered from ThPOK transgenic mice. We therefore proceeded to determine whether the protein level of activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells for IL-10 and TGF-β were affected by the ThPOK transgene. Interestingly, we found that despite significantly lower levels of TGF-β transcripts, activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK transgenic mice produced significantly more TGF-β protein than similarly activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from normal mice (Fig. 6c). By contrast, the protein levels of Gata-3, IL-4 and IL-10 of activated CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from either FoxP3-DTR and ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice were similar (Fig. 6c).

To determine whether the higher suppressor activity of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK transgenic mice was a result of TGF-β we repeated the suppressor assay with the inclusion of either control or anti-TGF-β antibodies. We found that addition of anti-TGF-β antibodies reduced the suppressor activity of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK-FoxP3-DTR mice to that of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from FoxP3-DTR mice (Fig. 6d). This result indicates that the higher suppressive activity of CD4+ FoxP3+ cells from ThPOK transgenic mice is a result of the higher amount of TGF-β protein produced by these cells.

Discussion

The ThPOK transcription factor plays a pivotal role in the development of CD4 T cells and CD4/CD8 lineage decisions. Furthermore, transgenic expression of ThPOK redirects developing thymocytes expressing MHC I-restricted TCRs into the CD4 lineage4,5,45 and retroviral expression of ThPOK in peripheral CD8+ T cells inhibits CD8 expression and effector functions and promotes the expression of CD4-specific helper genes.38 These observations indicate that the ThPOK transcription factor affects both intra-thymic and post-thymic stages of conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell development. However, it is not known whether ThPOK can affect the development and function of other T-cell types. In this study, we investigated the effect of the ThPOK transcription on the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells. Unlike conventional CD8 T cells, which are dependent on low-affinity interactions with the selecting ligands, both self-specific CD8 T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells are dependent on high-affinity interactions with their selecting ligand for their development.22,46 We found that transgenic expression of ThPOK differentially affected the development and function of these two regulatory cell types. Whereas ThPOK converted self-specific CD8 cells into non-self-reactive CD4 T cells with a survival disadvantage, the development and function of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells were enhanced by ThPOK.

It is noted that > 80% of peripheral CD4+ T cells from ThPOK H-Y male mice do not express the H-Y TCR. Previous studies have shown that the development of CD4+ T cells in male H-Y mice was inhibited because of the deletion of immature CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes at an early stage. However, a low percentage of mature peripheral CD4+ T cells expressing endogenous α-chain genes do develop in these mice.11,12 As the ThPOK transgene is not expected to affect the development of these cells, it is reasonable to detect their existence in ThPOK H-Y male mice. However, the expression of the wrong co-receptor by the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells rendered them non-male-reactive and affected their survival in peripheral lymphoid organs. This is consistent with our previous studies demonstrating that the survival and the maintenance of the memory phenotype of self-specific CD8lo cells in peripheral lymphoid organs is dependent on continuous antigen stimulation.43 Hence, the poor recovery of CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells from male ThPOK H-Y mice is probably a result of their survival disadvantage in the peripheral lymphoid organs of these mice.

The converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells also differ from self-specific CD8 cells in the expression of memory markers, proliferative response to IL-2 and IL-15, and expression of Eomes, granzyme B, IFN-γ, TNF-α and NK markers after activation. Furthermore, the converted CD4+ H-Y TCR+ cells acquire properties that are characteristic of conventional CD4+ T helper cells, i.e. production of Gata-3 and IL-4 transcripts after activation. There are several similarities between the effect of ThPOK on the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells and conventional CD8 T cells. These similarities include the conversion of these cells to CD4+ T cells, inability to express granzyme B, IFN-γ and Eomes, and expression of higher levels of Gata-3 and IL-4 transcripts after PMA + ionomycin activation. We have noted that there are major differences in the requirements for the development of self-specific CD8 T cells and conventional CD8 T cells that include differential dependence for Tec kinases, RasGRP1, IL-15 and affinity for the selecting ligands. Despite these differences, the ThPOK transgene is able to affect the development and function of self-specific CD8 T cells. However, these data may only indicate the effect of the ThPOK transcription factor on the development and function of memory CD8 T cells and do not reflect a lineage switch of memory CD8+ T cells into conventional CD4+ T helper cells. It also remains to be determined whether the ThPOK transgene can affect the development and function of other cytotoxic cell types such as NK cells.

The effect of the ThPOK transgene on the development and function of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells has not been determined. In this study, we found that the ThPOK transgene affected the development as well the function of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells. We found that more CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells were produced in ThPOK transgenic mice. The CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells express higher levels of CD25 (Fig. 5d) but not CTLA-4 and GITR (data not shown). Furthermore, activated CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice express higher levels of IL-2 transcripts (Fig. 5d). As the development of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells is dependent on IL-2,47 the higher expression of CD25 and IL-2 transcripts by these cells may have contributed to their more efficient development in ThPOK transgenic mice. Interestingly, the CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice were more suppressive on a per cell basis when compared with their counterpart from normal mice. This higher suppressor activity was observed in spite of lower levels of TGF-β transcripts that are produced by PMA + ionomycin-activated cells. Surprisingly, despite producing significantly lower level of TGF-β transcripts, CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice produced more TGF-β protein on activation (Fig. 6c). Previous studies showed that the 2·5-kb TGF-β transcript is poorly translated in human, rat and mouse cells.48–51 Furthermore, its unusually long GC-rich 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions46 performed either inhibitory or stimulatory roles in the translation of the TGF-β transcript.52,53 It is possible that the higher level of TGF-β protein that is produced by CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice may be a result of alteration in the regulation of these untranslated region sequences, leading to more efficient translation of the TGF-β transcript in these cells. Further studies are required to test this hypothesis. However, regardless of the mechanism that leads to more efficient production of the TGF-β protein, we have conclusively shown that the higher suppressor activity of CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells from ThPOK transgenic mice was due to TGF-β (Fig. 6d).

In summary, this study showed that the CD4 lineage-specific transcription factor ThPOK is able to differentially affect the development and function of self-specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ FoxP3+ Treg cells. Further studies will determine whether ThPOK can alter the development and function of other cell types. These observations also provide novel insight regarding new approaches to alter the development and effector function of various T-cell subsets and provide new avenues for immune regulation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Remy Bosselut for providing us with breeders for the ThPOK transgenic mice and Dr Alexander Rudensky for providing breeders for the FoxP3-DTR mice. We thank Jade Tong and Soo-Jeet Teh for excellent technical assistance and the staff of the Westbrook Animal Unit, UBC for animal husbandry. We thank Andy Johnson of the Life Sciences Institute Flow Cytometry Facility at UBC for assistance with cell sorting. This research is funded by grant 019458 from the Canadian Cancer Society to Hung-Sia Teh and grant NSC 101-2811-B-010-601 from National Science Council, Taiwan to Yuh-Ching Twu.

Authors' contribution

Yuh-Ching Twu designed and performed the research, analysed and interpreted the data, performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. Hung-Sia Teh designed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Increased recovery of thymocytes in male H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice.

References

- 1.Singer A, Bosselut R. CD4/CD8 coreceptors in thymocyte development, selection, and lineage commitment: analysis of the CD4/CD8 lineage decision. Adv Immunol. 2004;83:91–131. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)83003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yasutomo K, Doyle C, Miele L, Fuchs C, Germain RN. The duration of antigen receptor signalling determines CD4+ versus CD8+ T-cell lineage fate. Nature. 2000;404:506–10. doi: 10.1038/35006664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taniuchi I, Osato M, Egawa T, Sunshine MJ, Bae SC, Komori T, Ito Y, Littman DR. Differential requirements for Runx proteins in CD4 repression and epigenetic silencing during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 2002;111:621–33. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He X, Dave VP, Zhang Y, et al. The zinc finger transcription factor Th-POK regulates CD4 versus CD8 T-cell lineage commitment. Nature. 2005;433:826–33. doi: 10.1038/nature03338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun G, Liu X, Mercado P, Jenkinson SR, Kypriotou M, Feigenbaum L, Galéra P, Bosselut R. The zinc finger protein cKrox directs CD4 lineage differentiation during intrathymic T cell positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:373–81. doi: 10.1038/ni1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Hoyos G, Anderson MK, Wang C, Rothenberg EV, Alberola-Ila J. GATA-3 expression is controlled by TCR signals and regulates CD4/CD8 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:83–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pai SY, Truitt ML, Ting CN, Leiden JM, Glimcher LH, Ho IC. Critical roles for transcription factor GATA-3 in thymocyte development. Immunity. 2003;19:863–75. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egawa T, Tillman RE, Naoe Y, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. The role of the Runx transcription factors in thymocyte differentiation and in homeostasis of naive T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1945–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu J, Min B, Hu-Li J, et al. Conditional deletion of Gata3 shows its essential function in TH1-TH2 responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1157–65. doi: 10.1038/ni1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Wildt KF, Zhu J, et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factors GATA-3 and ThPOK during intrathymic differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1122–30. doi: 10.1038/ni.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kisielow P, Bluthmann H, Staerz UD, Steinmetz M, Boehmer von H. Tolerance in T-cell-receptor transgenic mice involves deletion of nonmature CD4+ 8+ thymocytes. Nature. 1988;333:742–6. doi: 10.1038/333742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teh HS, Kishi H, Scott B, Boehmer Von H. Deletion of autospecific T cells in T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice spares cells with normal TCR levels and low levels of CD8 molecules. J Exp Med. 1989;169:795–806. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada H, Ninomiya T, Hashimoto A, Tamada K, Takimoto H, Nomoto K. Positive selection of extrathymically developed T cells by self-antigens. J Exp Med. 1998;188:779–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanji S, Teh SJ, Oble D, Priatel JJ, Teh HS. Self-reactive memory-phenotype CD8 T cells exhibit both MHC-restricted and non-MHC-restricted cytotoxicity: a role for the T-cell receptor and natural killer cell receptors. Blood. 2004;104:2116–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhanji S, Teh HS. IL-2-activated CD8+ CD44high cells express both adaptive and innate immune system receptors and demonstrate specificity for syngeneic tumor cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3442–50. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow MT, Dhanji S, Cross J, Johnson P, Teh HS. H2-M3-restricted T cells participate in the priming of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5098–104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Priatel JJ, Chow MT, Teh HS. Preferential development of CD4 and CD8 T regulatory cells in RasGRP1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2008;180:5973–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atherly LO, Lucas JA, Felices M, Yin CC, Reiner SL, Berg LJ. The Tec family tyrosine kinases Itk and Rlk regulate the development of conventional CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2006;25:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broussard C, Fleischacker C, Horai R, et al. Altered development of CD8+ T cell lineages in mice deficient for the Tec kinases Itk and Rlk. Immunity. 2006;25:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois S, Waldmann TA, Muller JR. ITK and IL-15 support two distinct subsets of CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605212103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itsumi M, Yoshikai Y, Yamada H. IL-15 is critical for the maintenance and innate functions of self-specific CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1784–93. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan MS, Boesteanu A, Reed AJ, Petrone AL, Holenbeck AE, Lerman MA, Naji A, Caton AJ. Thymic selection of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:301–6. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marks BR, Nowyhed HN, Choi JY, Poholek AC, Odegard JM, Flavell RA, Craft J. Thymic self-reactivity selects natural interleukin 17-producing T cells that can regulate peripheral inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1125–32. doi: 10.1038/ni.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakaguchi S, Regulatory T. Cells: key controllers of immunologic self-tolerance. Cell. 2000;101:455–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor PA, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. CD4+ CD25+ immune regulatory cells are required for induction of tolerance to alloantigen via costimulatory blockade. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1311–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suri-Payer E, Amar AZ, Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutmuller RP, Duivenvoorde van LM, Elsas van A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–42. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li MO, Wan YY, Flavell RA. T cell-produced transforming growth factor-β1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1- and Th17-cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;26:579–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pesu M, Watford WT, Wei L, et al. T-cell-expressed proprotein convertase furin is essential for maintenance of peripheral immune tolerance. Nature. 2008;455:246–50. doi: 10.1038/nature07210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pandiyan P, Zheng L, Ishihara S, Reed J, Lenardo MJ. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1353–62. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garin MI, Chu CC, Golshayan D, Cernuda-Morollon E, Wait R, Lechler RI. Galectin-1: a key effector of regulation mediated by CD4+ CD25+ T cells. Blood. 2007;109:2058–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gondek DC, Lu LF, Quezada SA, Sakaguchi S, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: contact-mediated suppression by CD4+ CD25+ regulatory cells involves a granzyme B-dependent, perforin-independent mechanism. J Immunol. 2005;174:1783–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.4.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jenkinson SR, Intlekofer AM, Sun G, Feigenbaum L, Reiner SL, Bosselut R. Expression of the transcription factor cKrox in peripheral CD8 T cells reveals substantial postthymic plasticity in CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:267–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teh HS, Kisielow P, Scott B, Kishi H, Uematsu Y, Bluthmann H, von Boehmer H. Thymic major histocompatibility complex antigens and the αβ T-cell receptor determine the CD4/CD8 phenotype of T cells. Nature. 1988;335:229–33. doi: 10.1038/335229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winer J, Jung CK, Shackel I, Williams PM. Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:41–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearce EL, Mullen AC, Martins GA, et al. Control of effector CD8+ T cell function by the transcription factor Eomesodermin. Science. 2003;302:1041–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1090148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dhanji S, Chow MT, Teh HS. Self-antigen maintains the innate antibacterial function of self-specific CD8 T cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:138–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Almeida AR, Legrand N, Papiernik M, Freitas AA. Homeostasis of peripheral CD4+ T cells: IL-2Rα and IL-2 shape a population of regulatory cells that controls CD4+ T cell numbers. J Immunol. 2002;169:4850–60. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keefe R, Dave V, Allman D, Wiest D, Kappes DJ. Regulation of lineage commitment distinct from positive selection. Science. 1999;286:1149–53. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leishman AJ, Gapin L, Capone M, Palmer E, MacDonald HR, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Precursors of functional MHC class I- or class II-restricted CD8αα+ T cells are positively selected in the thymus by agonist self-peptides. Immunity. 2002;16:355–64. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SJ, Park K, Koeller D, et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of the human transforming growth factor-β1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13702–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romeo DS, Park K, Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Kim SJ. An element of the transforming growth factor-β1 5'-untranslated region represses translation and specifically binds a cytosolic factor. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:759–66. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.6.8361501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Allison RS, Mumy ML, Wakefield LM. Translational control elements in the major human transforming growth factor-β1 mRNA. Growth Factors. 1998;16:89–100. doi: 10.3109/08977199809002120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang YL, Guh JY, Yang ML, Lai YH, Tsai JH, Hung WC, Chang CC, Chuang LY. Interaction between high glucose and TGF-β in cell cycle protein regulations in MDCK cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:182–93. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V92182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonenberg N. mRNA translation: influence of the 5' and 3' untranslated regions. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:310–5. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(05)80059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scotto L, Assoian RK. A GC-rich domain with bifunctional effects on mRNA and protein levels: implications for control of transforming growth factor β1 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3588–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.6.3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Increased recovery of thymocytes in male H-Y ThPOK transgenic mice.