Abstract

Background

Arp2/3 complex is a key actin cytoskeletal regulator that creates branched actin filament networks in response to cellular signals. WASP-activated Arp2/3 complex assembles branched actin networks by nucleating new filaments from the sides of pre-existing ones. WASP-mediated activation requires seed filaments, to which the WASP-bound Arp2/3 complex can bind to form branches, but the source of the first substrate filaments for branching is unknown.

Results

Here we show that Dip1, a member of the WISH/DIP/SPIN90 family of actin regulators, potently activates Arp2/3 complex without preformed filaments. Unlike other Arp2/3 complex activators, Dip1 does not bind actin monomers or filaments, and interacts with the complex using a non-WASP-like binding mode. In addition, Dip1-activated Arp2/3 complex creates linear instead of branched actin filament networks.

Conclusions

Our data show the mechanism by which Dip1 and other WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins can provide seed filaments to Arp2/3 complex to serve as master switches in initiating branched actin assembly. This mechanism is distinct from other known activators of Arp2/3 complex.

Introduction

The dynamic meshworks of filaments that make up the actin cytoskeleton are tightly regulated to orchestrate complex cellular process like endocytosis and cellular motility. Assembly of actin filaments is limited by a slow nucleation step, in which the first few actin monomers assemble to form a template for assembly of a new filament [1]. Cells contain multiple actin filament nucleators to regulate network assembly [2], but Arp2/3 complex is the only one capable of nucleating branched actin networks [3]. Its activity is tightly regulated, and there are currently about a dozen known Arp2/3 complex activators, called nucleation promoting factors (NPFs) [3, 4]. WASP/Scar family proteins, the best-studied NPFs, recruit actin monomers to Arp2/3 complex to stimulate an activating conformational change [5, 6]. However, nucleation occurs only when the complex is bound to the sides of pre-existing filaments [7], ensuring that the complex creates exclusively branched actin networks. Once branching is initiated, Arp2/3 complex-nucleated filaments can serve as substrates to drive the reaction, but the source of the very first substrate actin filaments remains an open question. Cellular concentrations of actin filaments are high, but distinct pools of filaments are coated with characteristic actin binding proteins that may influence their suitability as substrates for the complex [8, 9]. For example, tropomyosin coats bundles of linear actin filaments, blocking Arp2/3 complex binding and inhibiting branching nucleation [10].

WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins are poorly understood actin regulators that interact with Arp2/3 complex [11]. SPIN90, the mammalian ortholog, was previously shown to activate Arp2/3 complex, and based on sequence alignments it was hypothesized to be a WASP-like activator [11]. Consistent with this, knockdown of SPIN90 prevented PDGF-stimulated formation of lamelipodia and caused defects in actin organization [11]. In contrast, another study showed that mammalian WISH/DIP/SPIN90 could bind N-WASP to relieve its auto-inhibition and induce activation of the Arp2/3 complex, but could not directly activate Arp2/3 complex [12]. Therefore, the role of WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins in regulating Arp2/3 complex is uncertain.

In S. pombe, Dip1 regulates the timing of actin assembly in endocytic actin patches [13]. Actin patches are nucleated by Arp2/3 complex, and branched filaments in these networks are thought to drive endocytosis by providing the pushing forces to invaginate membranes and internalize the endocytic vesicles [14]. Normally, the S. pombe WASP protein, Wsp1, arrives at endocytic sites 8-10 seconds before internalization and initiates a tightly controlled sequence of actin polymerization and recruitment of actin binding proteins [13, 15]. In dip1Δ cells, the timing of this process is random, with actin assembly and internalization sometimes delayed by hundreds of seconds. This delay was hypothesized to result from the absence of suitable substrate actin filaments for Wsp1-activated branching nucleation in dip1 knockouts [13]. These observations led us to ask how Dip1 can regulate the initiation of branched actin networks, and how it might provide the initial substrate filaments for Arp2/3 complex.

Here we show that Dip1 directly activates Arp2/3 complex, but with a mechanism distinct from other NPFs. Dip1 does not interact with actin filaments or monomers like other NPFs, but instead uses a non-WASP-like interaction to bind to Arp2/3 complex and initiate an activating conformational change. Importantly, we show that Dip-mediated activation does not require preformed filaments, providing the biochemical mechanism by which Dip1 can control the timing of endocytic actin assembly. The biochemical properties of Dip1 are conserved in SPIN90, suggesting WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins may have a general role in providing seed filaments to initiate branching nucleation.

Results

S. pombe Dip1 Is a Potent Activator of Arp2/3 complex

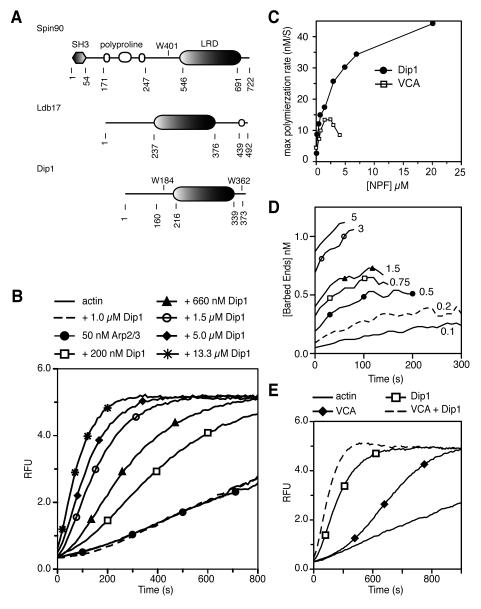

The S. pombe WISH/DIP/SPIN90 ortholog Dip1 has a conserved leucine rich domain (LRD), but has neither a polyproline region nor Src homology domain III (SH3) present in other orthologs (Figure 1A, S1). To determine if Dip1 can influence the activity of Arp2/3 complex, we tested its activity in pyrene actin polymerization assays. Purified Dip1 dramatically increased polymerization rates in reactions containing Arp2/3 complex, but had no effect on reactions containing only actin, demonstrating that Dip1 activates Arp2/3 complex (Figure 1B). Comparing the activation potency of Dip1 to the canonical type I NPF from S. pombe, Wsp1, revealed striking differences between these two activators. First, Dip1 is a more potent activator of Arp2/3 complex than Wsp1. At saturation, the minimal construct of Wsp1 sufficient to activate Arp2/3 complex, Wsp1-VCA [16], increased the maximum polymerization rate to a level nine fold higher than Arp2/3 complex alone. In contrast, near saturating concentrations of Dip1 increased the maximum polymerization rate forty-fold over Arp2/3 complex alone (Figure 1C). At each concentration tested, Dip1 produced faster polymerization rates than the equivalent concentration of Wsp1-VCA. With 50 nM Arp2/3 complex, saturating Wsp1-VCA produced 0.7 nM barbed ends while near saturating Dip1 produced 1.3 nM ends (Figure 1D). A second critical difference between the two NPFs is that at high concentrations, Wsp1-VCA potently inhibits actin polymerization, whereas Dip1 did not slow accumulation of polymer even at concentrations up to 20 μM (Figure 1C). VCA inhibits polymerization because its V-region binds to actin monomers, preventing them from spontaneously associating into nuclei [17]. That Dip1 does not slow polymerization suggests that it does not bind actin monomers like V, and that it may use a different mechanism to activate Arp2/3 complex. Finally, adding a GST tag to Dip1 did not increase its potency (Figure S1). This is in contrast to WASP family proteins, which show increased activity upon induced dimerization [18].

Figure 1.

Dip1 is a potent activator of Arp2/3 complex. (A) Domain organization of human SPIN90, budding yeast Ldb17 and fission yeast Dip1. The leucine rich domain, LRD, is conserved in all species. The LRD not have sequence homology to leucine rich repeat domains. (B) Time course of polymerization of 3 μM 15 % pyrene-actin with or without 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex and a range of concentrations of Dip1. (C) Plot of maximum polymerization rate versus Dip1 or Wsp1-VCA concentration for pyrene-actin polymerization assays described in B. (D) Plot of calculated number of barbed ends versus time for reactions described in B. Micromolar concentration of Dip1 in each reaction is indicated. (E) Pyrene actin polymerization assays with Arp2/3 complex and pyrene actin as in (B), plus 1μM Dip1 and 200 nM Wsp1-VCA as indicated. See also Figure S1.

Wsp1 and Dip1 colocalize to endocytic actin patches, and both contribute to the assembly of actin filament networks in patches [13]. To determine if these NPFs can cooperate to assemble actin filaments in vitro, we added Dip1 to a pyrene actin polymerization assay containing Wsp1 and Arp2/3 complex. Dip1 increased the maximum polymerization rate 2.5-fold over reactions containing Arp2/3 complex activated by Wsp1 alone, suggesting that Dip1 and Wsp1 can act either additively or synergistically (Figure 1E). To explore further, we preincubated Arp2/3 complex with saturating Dip1 and a range of concentrations of GST-Wsp1-VCA before initiating polymerization assays. GST-Wsp1-VCA did not increase the maximum polymerization rate, and at high concentrations it slowed polymerization (Figure S1). These data indicate that Dip1 and Wsp1 are unlikely to synergistically activate the complex by simultaneously engaging it. The decreased polymerization rates at high concentrations of GST-Wsp1-VCA could be due to a number of factors, including competition of the two NPFs for binding to the complex, or slowed spontaneous or induced nucleation from Wsp1-bound actin monomers.

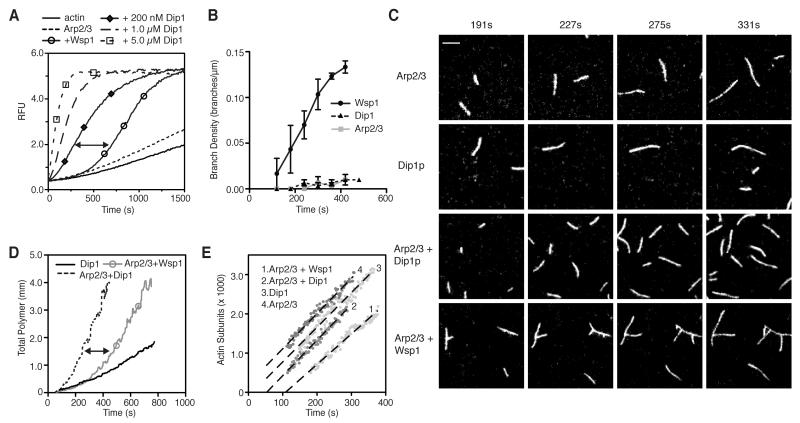

Dip1 Activates Arp2/3 Complex Without Preformed Actin Filaments

Because WASP-mediated activation of Arp2/3 complex requires binding of the complex to a preformed filament, accumulation of branched filaments proceeds through a lag phase caused by slow spontaneous nucleation [17]. However, examination of the polymerization time courses revealed that the lag phase of Dip1-activated Arp2/3 complex was insignificant compared to the lag we observed with GST-Wsp1-VCA activated Arp2/3 complex (Figure 2A). An important consequence of the requirement for preformed filaments is that WASP-activated Arp2/3 complex specifically nucleates branched actin filaments. To determine if Dip1 activates Arp2/3 complex without requiring preformed filaments, we used TIRF microscopy to compare actin polymerization in the presence or absence of Arp2/3 complex and Dip1 or Wsp1-VCA (Movie S1-2). As expected, Arp2/3 complex activated by Wsp1-VCA produced branched filaments (Figure 2B,C, Movie S3). In contrast, Dip1-activated Arp2/3 complex produced many short, linear filaments that did not branch, indicating that preformed filaments are not required for activation of the complex (Figure 2B,C, Movie S4,S5). The accumulation of filamentous actin in TIRF assays was accelerated in reactions containing Dip1 versus Wsp1-VCA-activated Arp2/3 complex, consistent with the absence of a lag phase in bulk assays (Figure 2D). Filaments nucleated by Dip1 and Arp2/3 complex elongated from their barbed ends at the same rate as reactions containing Wsp1-VCA and Arp2/3 complex or actin alone, consistent with our conclusion that Dip1 acts directly on the complex rather than actin filament barbed ends (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Dip1-mediated activation of Arp2/3 does not require preformed actin filaments. (A) Time course of polymerization of 3 μM 15% pyrene actin with 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex, and 200 nM Wsp1-VCA or the indicated concentrations of Dip1. Arrow highlights lag in activation of Arp2/3 complex by Wsp1-VCA. (B) Plot of branch density versus time for TIRF data in panel C. Data are represented as mean +/- SEM. (C) Total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) images of 33% Oregon green-488 actin polymerizing with 50nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex, 150 nM Dip1 and 75 nM GST-Wsp1-VCA as indicated. Scale Bar = 2.2 μm. (D) Plot of total polymer length verses time for TIRF data in panel C. (E) Plot of filament lengths expressed in subunits of actin versus time for select single filaments in TIRF data in panel B. Dashed lines are linear fits of each filament growth. Global analysis of at least 7 filaments/reaction showed that the average growth rate in reactions with Arp2/3 alone was 9.0 ± 0.1 s−1 (n=541); Dip1 alone was 9.7 ± 0.3 s−1 (n=816); Arp2/3 + GST-Wsp1-VCA was 9.2 ± 0.2 s−1 (n=641); and Arp2/3 + dip1 was 9.5 ± 0.2 s−1 (n=775).

To provide additional evidence that actin filaments are not required for Dip1-Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation, we tested the influence of the Arp2/3 complex inhibitor protein coronin on Dip1 activity. Coronin binds to actin filament sides and blocks Arp2/3 complex from associating, thereby inhibiting nucleation [19]. We reasoned that if Dip1-mediated activation of Arp2/3 complex does not require actin filament side binding, coronin will not antagonize Dip1. Indeed, we found that coronin had no effect on Dip1-mediated activation of the complex in pyrene actin polymerization assays, but blocked Wsp1-VCA-mediated activation (Figure 3A). As an additional test, we asked if increased concentrations of actin filament side binding sites stimulate Dip1 activity. Preformed actin filaments had no effect on the polymerization rate in a reaction containing Dip1 and Arp2/3 complex, but eliminated the lag phase in a reaction containing Wsp1 and Arp2/3 complex (Figure 3B). These data demonstrate that Dip1 does not require preformed filaments to active Arp2/3 complex.

Figure 3.

Bulk polymerization assays verify preformed filaments are not required for Dip1-mediated Arp2/3 complex activation. (A) Pyrene actin polymerization assay showing the influence of 1.5 μM Crn1 WD-CC construct (contains residues 1-410 and 594-651) on activation of 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex by 5 μM Dip1 or 200 nM GST-Wsp1-VCA. (B) Pyrene actin polymerization assay showing the influence of preformed actin filaments on Dip1- versus Wsp1-activated Arp2/3 complex. Reactions contained 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex, 1 μM Dip1, 200nM GST-Wsp1-VCA and 300 nM actin filament seeds as indicated.

Dip1 Uses a Mechanism Distinct from Known Type I or Type II NPFs to Activate Arp2/3 complex

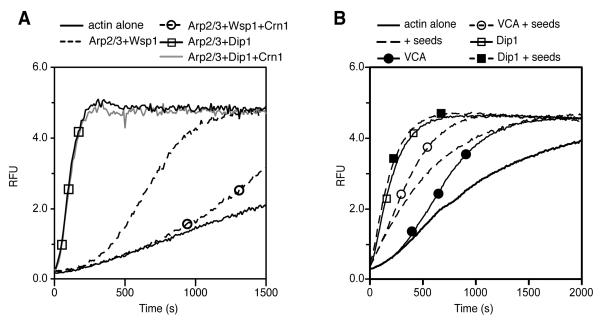

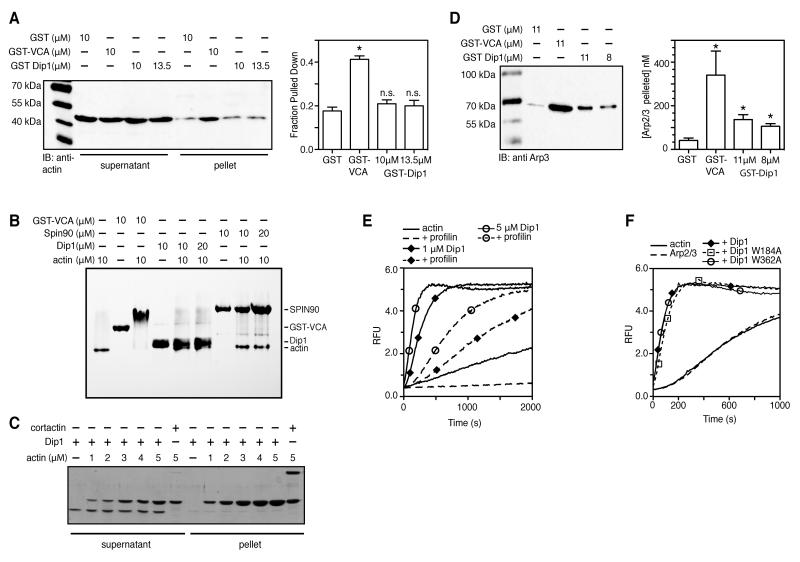

NPFs have been separated into two categories: type I, which bind to Arp2/3 complex and actin monomers, and type II NPFs, which bind Arp2/3 complex and filamentous actin [3]. Importantly, the actin binding specificity affects the mechanism by which Arp2/3 is activated. Recruitment of actin monomers to the complex by WASP-VCA, the canonical type I NPF, stimulates formation of the actin “short-pitch” conformation of the Arp2-Arp3 subunits, thereby stimulating nucleation activity [5, 6]. Less is known about how Type II NPFs regulate the complex, but their filament binding domains are key contributors to activation [3]. To determine how Dip1 activates the complex, we tested its interactions with actin. Dip1 did not interact with actin monomers in a pull down assay or a native gel shift assay, suggesting that it does not recruit actin monomers to Arp2/3 complex (Figure 4A,B). We next tested the ability of Dip1 to interact with actin filaments. Dip1 did not copellet with actin filaments at any concentration we tested, up to 4.9 μM, whereas ~99% of the prototypical type II NPF, cortactin, copelleted at 4.9 μM actin (Figure 4C). That Dip1 does not interact with either actin monomers or filaments demonstrates that it uses a different mechanism than known type I or type II NPFs.

Figure 4.

Dip1 uses a non-WASp-like mechanism to activate Arp2/3 complex. (A) Western blot of supernatant and pelleted fractions in actin monomer pull-down assay. Actin at 1.0 μM was pulled down with 10 μM GST-Wsp1-VCA, 10 or 13.5 μM or 10 μM GST control protein. Quantified data are represented as the mean +/- SEM (n=3), asterisk represents significant difference compared to GST control p < 0.0001 (parametric two-tailed T-test) (B) Coomassie-stained native gel shift binding assay. Reactions contained indicated concentrations of each protein plus 40 μM Latrunculin B to prevent actin polymerization. Arrows indicate Dip1 (top) and actin (bottom) (C) Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel of actin filament copelleting assay. Dip1 (750 nM) or cortactin (750 nM) were copelleted with a range of concentrations of polymerized actin (total actin concentration is indicated). (D) Anti-Arp3 western blot of pull-down assay containing GST-Dip1 and 1.14 μM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex. Control assays contained 11 μM GST or 11 μM GSTWsp1-VCA. Quantified data are represented as the mean +/- SEM (n=3), asterisk represents significant difference compared to GST control p < 0.05 (parametric two-tailed T-test) (E, F) Time courses of polymerization of 3 μM 15% pyrene actin with 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex, 7.5 μM profilin and 5 μM mutant or wild-type Dip1, as indicated.

Because Dip1 activates Arp2/3 complex but does not interact with filaments or monomers, we hypothesized that it might interact directly with Arp2/3 complex to influence its activity. To test this, we used GST-tagged Dip1 to pull down Arp2/3 complex. Dip1 at 8 μM pulled down 20% of a 1.14 μM solution of Arp2/3 complex, showing the two proteins interact directly (Figure 4D). Dip1 bound weakly to the complex compared to GST-Wsp1-VCA, and we did not saturate binding. This observation is consistent with our actin polymerization assays, which show the concentration at which Dip1 reaches half maximal activation is approximately 6-fold greater than Wsp1-VCA (Figure 1C).

Proflin binds actin monomers to catalyze nucleotide exchange and inhibit spontaneous nucleation of filaments [20, 21]. In addition, profilin has been shown to inhibit activation of Arp2/3 complex by some WASP/Scar family proteins [22, 23]. To determine if profilin affects Dip1-mediated activation of Arp2/3 complex, we added excess profilin to pyrene actin polymerization assays. Profilin at 7.5 μM decreased the number of barbed ends created by 5 μM Dip1 and 50 nM Arp2/3 complex from 0.38 to 0.12 nM (Figure 4E). This is more than the profilin-induced decrease in spontaneously nucleated ends (0.082 nM to 0.02 nM), suggesting that while Dip1 can activate Arp2/3 complex even in excess profilin, profilin may have a direct effect on Dip1-mediated activation of the complex that slows down nucleation.

Dip1 does not have a WASp-like CA region

Sequence analysis suggested that SPIN90, the mammalian ortholog of Dip1, has a CA-like region that might interact with and activate Arp2/3 complex using the same mechanism as WASP CA [11] (Figure S2). The A sequence in WASP/Scar proteins consists of a conserved tryptophan surrounded by variable numbers of acidic residues [24]. Previous data have shown that the trypotophan in the A region of WASP forms a contact with Arp2/3 complex important for binding and activation [25, 26] [27]. Analysis of the Dip1 sequence revealed two tryptophans, W184 and W382 (Figure 1A, Figure S2). To ask if either tryptophan marks a potential A region that could allow Dip1 to make a WASP-like interaction with the complex, we singly mutated each tryptophan to alanine. Neither tryptophan mutant affected Dip1 activity (Figure 4F). Therefore, we conclude that Dip1 does not interact with Arp2/3 complex using a WASP-like binding mode.

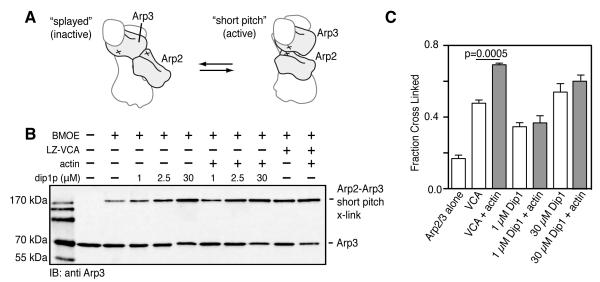

Dip1 Stimulates Formation of the Short Pitch Arp2-Arp3 dimer

Our data show that Dip1 activates the complex but does not bind with significant affinity to actin monomers, and does not interact with the complex using a WASP-like binding mode. To test this, we used a previously described double cysteine mutant of budding yeast Arp2/3 complex [6]. This mutant harbors engineered cysteine residues on Arp2 and Arp3 that can be cross-linked upon activation of the complex, when Arp2 and Arp3 adopt a short pitch filament-like conformation. Dip1 activates budding yeast Arp2/3 complex, so this assay can be used to determine the influence of Dip1 on formation of the short pitch conformation (Figure S3). We added the 8 Å crosslinker bismaleimideoethane (BMOE) to the engineered complex in the presence of Dip1 or N-WASP-VCA. Dip1 at 30 μM increased the formation of the short pitch crosslink 3.5 fold over Arp2/3 complex alone (Figure 5). Previous data showed that N-WASP-VCA alone weakly shifts the population toward the active state, but that actin monomers and VCA cooperate to strongly induce the short pitch conformation [6]. In contrast, we found that actin monomers did not increase population of the short pitch conformation stimulated by Dip1 (Figure 5). Together, our data indicate that Dip1 activates Arp2/3 complex by stimulating formation of the short-pitch conformation, using a mechanism distinct from WASP.

Figure 5.

Dip1 stimulates formation of the short pitch conformation. (A) Cartoon schematic showing relative positions of engineered cysteine residues on Arp2 and Arp3 in active or inactive conformation. (B) Anti-Arp3 western blot of crosslinking assays containing 1.0 μM S. cerevisiae Arp2/3 complex (Arp3L155C/Arp2R198C) and 25 μM BMOE, 10 μM leucine-zipper (LZ) N-WASp-VCA, 10 μM latrunculin B-bound actin, and Dip1 as indicated. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 60 s before quenching with 1.25 mM dithiolthreitol and separating by SDS-PAGE. (C) Quantification of short-pitch Arp2-Arp3 crosslinking assays as described in panel. Data are represented as mean +/- SEM. P-value calculated from parametric two-tailed t-test

The Mechanism of Activation of Arp2/3 complex is Conserved Among WISH/DIP/SPIN90 Proteins

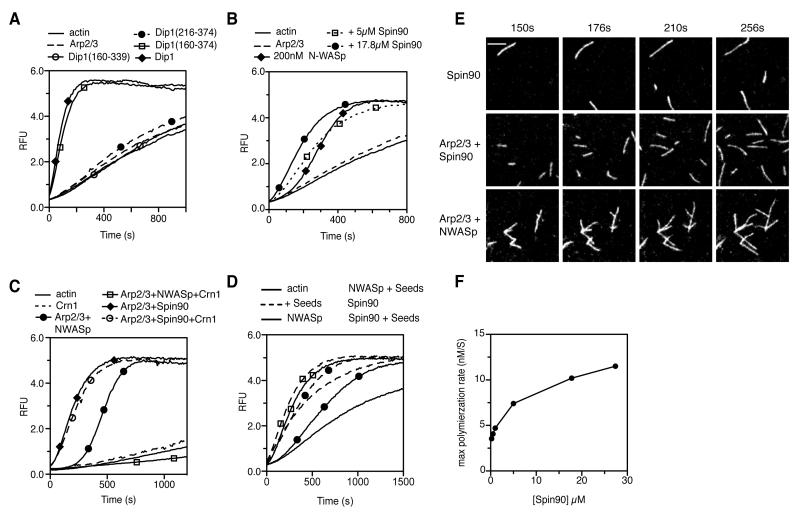

To determine which regions of Dip1 are required for activation, we tested the ability of Dip1 truncations to activate Arp2/3 complex. An N-terminal deletion construct starting at residue 160 retained nearly full activity (Figure 1A, 6A). This result is consistent with the lack of conservation of the N-terminal region among WISH/DIP/SPIN90 family proteins. Regions flanking the LRD domain, as defined by our analysis of fungal LRD sequences, were also required for activity (Figure 6A). However, truncation of these flanking sequences resulted in a poorly behaved protein with low solubility and a propensity to aggregate (data not shown). Therefore, these regions could either be important for protein stability or may be directly involved in activating Arp2/3 complex, or both.

Figure 6.

SPIN90 and Dip1 may use the same mechanism to activate Arp2/3 complex. (A) Time course of 3 μM 15% pyrene actin polymerization showing influence of wild type and 2.2 μM GSTDip1 truncations on GST-Dip1-mediated activation of 50 nM S. pombe Arp2/3 complex. (B) Time course of 3 μM 15% pyrene actin polymerization containing SPIN90 (residues 269-722) or GSTN-WASp-VCA and 50 nM bovine Arp2/3 complex. (C) Pyrene actin polymerization assays containing 50 nM bovine Arp2/3 complex, 2 μM Crn1 WD-CC construct, 17.8 μM SPIN90, and 200 nM GST-N-WASp-VCA as indicated. (D) Pyrene actin polymerization assay showing the influence of preformed actin filaments on Spin90 versus GST-N-WASp-VCA activated bovine Arp2/3 complex. Reactions contained 50 nM bovine Arp2/3 complex, 10.6 μM Spin90, 200 nM GST-N-WASp-VCA and 300 nM actin filament seeds as indicated. (E) Total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) images of 33% Oregon green-488 actin polymerizing with B. taurus Arp2/3 complex and 1.5 μM SPIN90 or 100 nM GST-NWASp-VCA as indicated. Reaction with 1.5 μM SPIN90 contains 25 nM Bt Arp2/3 and reaction with N-WASp-VCA contains 20 nM BtArp2/3 complex. Scale Bar = 2.2 μm. (F) Plot of maximum polymerization rate versus Spin90 concentration for pyrene-actin polymerization assays described in B.

Because the LRD domain is conserved in all WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins, we hypothesized that the mechanism of Dip1-mediated activation of the complex might be conserved. As previously reported, human SPIN90 activated the complex ([11], Figure 6B). Activation required relatively high concentrations, but like Dip1, SPIN90-mediated activation lacked a lag phase. SPIN90-mediated activation of Arp2/3 complex was not inhibited by coronin, and addition of preformed filaments did not increase activation of the complex by SPIN90 (Figure 6C,D). SPIN90-activated Arp2/3 complex produced linear instead of branched actin filaments in a TIRF microscopy assay, in contrast to a previous report (Figure 6E, Movie S6-S9) [28]. These data demonstrate that like Dip1, SPIN90, does not require preformed actin filaments to activate Arp2/3 complex. It was previously reported that SPIN90 harbors a V region similar to WASP proteins that allows it to interact with actin monomers, suggesting it may use a WASP-like activation mechanism [11]. However, our sequence analysis indicates that the proposed V region in SPIN90 has significant differences from other V-region-containing proteins (Figure S4). We also found substantial biochemical differences between WASP-V and the proposed SPIN90 V-region. For instance, SPIN90 did not interact with actin monomers in a native gel shift assay, unlike N-WASP-VCA (Figure 4B). In addition, while high concentrations of WASP-VCA inhibited actin monomers from spontaneously nucleating (Figure 1C), SPIN90 did not inhibit spontaneous nucleation at the highest concentrations we tested, up to 27.4 μM (Figure 6F). Together our data suggest that WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins use a conserved mechanism, distinct from other NPFs, that allows them to activate Arp2/3 complex without requiring preformed filaments.

Discussion

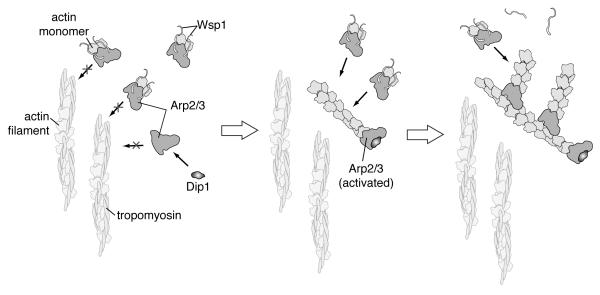

Here we show that Dip1 defines a distinct class of NPFs that directly bind and activate Arp2/3 complex. Dip1 is distinct from known NPFs in that it does not bind actin monomers or filaments, and does not contain an Arp2/3 complex-interacting CA (or A) region. The biochemical properties of Dip1 explain its ability to serve as the master timer in initiating the assembly of actin filaments during endocytosis. Based on our data, and on the work of Basu et. al. and others, we propose the following model for Dip1 function in actin patch assembly (Figure 7). Dip1 and Wsp1 are recruited to endocytic sites 8 to 10 seconds before internalization [13, 15]. Actin cables are nucleated by the formin For3 at the poles where they could potentially seed branching nucleation [29] [30], but are coated with tropomyosin [31, 32], so likely cannot serve as substrates for Wsp1-mediated Arp/3 complex nucleation [10]. Dip1 binds Arp2/3 complex, stimulating nucleation of unbranched filaments that provide seeds for Wsp1-mediated Arp2/3 complex activation. This model predicts that tropomyosin does not block Dip1-nucleated filaments from activating Wsp1-bound Arp2/3 complex, though we cannot currently explain why. Wsp1-activated branching creates more substrates for nucleation, resulting in a positive feedback loop that causes rapid assembly of the actin network. Deletion of Dip1 destroys the timing mechanism and initiation of the network becomes dependent on the stochastic encounter of Wsp1-Arp2/3 complex with rare suitable actin filament substrates [13].

Figure 7.

Cartoon model of initiation and propagation of Arp2/3-mediated branching nucleation by Dip1 and Wsp1. See text for details.

Our data show that Dip1 binds directly to Arp2/3 complex to stimulate formation of the short pitch conformation. Dip1 does not contain a CA region to bind Arp2/3 complex, and instead uses a non-WASP-like interaction to initiate this conformational change. We hypothesize that once the Dip1-Arp2/3 complex is in the short pitch conformation, actin monomers can associate with the barbed ends of both Arp2 and Arp3, creating a filament with a blocked pointed end and a barbed end that elongates at the same rate as spontaneously nucleated filaments. This mechanism is consistent with our elongation rate measurements and with structural and biochemical data indicating that Arp2/3 complex binds to the pointed end of the filaments it nucleates [33, 34]. Importantly, we showed that like Dip1, SPIN90 activates Arp2/3 complex without preformed filaments. In addition, we showed that SPIN90 binds significantly weaker to actin monomers than WASP and does not harbor a WASP-like V region. Together, these data indicate that SPIN90 and Dip1 use a common mechanism to activate Arp2/3 complex, which is likely conserved among WISH/DIP/SPIN90 proteins. One potentially important difference between SPIN90 and Dip1 is that SPIN90 contains a polyproline segment. While this segment is not required for SPIN90 activity (Figure 6B,C), it will be important to determine if it interacts with profilin-bound actin and how this interaction could influence Arp2/3 complex activation.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that Wsp1 is the dominant NPF in controlling the architecture of endocytic actin patches. First, electron microscopy of the patches show Arp2/3 complex nucleates a densely branched network of short (19-38 subunit) filaments [35, 36], more similar to the Wsp1-initiated networks than the unbranched Dip1-activated networks we observed in vitro. Second, Dip1 knockdown influences the timing of patch initiation, but not patch assembly or internalization after initiation, whereas Wsp1 deletion strains have defective patches that fail to internalize [13]. An important question is how Wsp1 is maintained as the dominant NPF in vivo, despite the ability of Dip1 to strongly activate the complex. One possibility is that the concentration of Dip1 is relatively low in patches, allowing it to remain active during assembly without significantly decreasing branch density. Consistent with this hypothesis, there are approximately 20 molecules of Dip1 per patch compared to about 150 Wsp1 molecules [13]. It is also possible that the activity of Dip1 is down regulated after initiation of the actin network, so that Dip1 is turned off as Wsp1 becomes active.

A key finding of this work is that Dip1 does not require preformed actin filaments to activate Arp2/3 complex, unlike other NPFs tested [7, 17]. This observation suggests that at least in some cases, cells use WISH/DIP/SPIN90, a specialized NPF, to create substrate filaments, instead of relying on nucleation machinery that functions independently of Arp2/3 complex. In actin patches, Dip1 may be better suited to initiate patch assembly than independently functioning nucleators. As previously mentioned, formin-nucleated filaments may not provide suitable filament substrates because they are coated with tropomyosin [10, 31]. In addition, formins remain at elongating filament barbed ends, preventing capping protein from blocking ends to keep filaments short [37]. Dip1 likely acts at the pointed end of filaments, so it may not influence barbed end capping. In budding yeast, Las17, the WASP/Scar family protein, was recently reported to contain a poly-proline segment that nucleates actin filaments without requiring preformed branches or Arp2/3 complex [38]. Mutation of these segments caused a phenotype distinct from the Dip1 knockout, extending the lifetime of the patches at the membrane and increasing the percentage of patches that fail to internalize. It will be important to determine if this segment works in concert with Ldb17, the budding yeast WISH/DIP/SPIN90 protein, or if the actin patch defects observed result from an inability of Las17 to deliver profilin-bound actin monomers to Arp2/3 complex. It will also be important to determine how short diffusing filaments severed by cofilin from disassembling patches might also play a role in initiating new patch assembly [39].

In endocytic actin patches, there are four known Arp2/3 complex activators (Pan1, Dip1, Myo1, Wsp1) in fission yeast and six in S. cerevisiae (Pan1, Myo3, Myo5, Las17, Crn1, and Abp1) [19, 40, 41]. While there are partial redundancies between some of these activators, mounting evidence suggests intricate but critical division of duties for these NPFs [16, 42]. Here we show that Wsp1 and Dip1 use different biochemical mechanisms to activate Arp2/3 complex, explaining how they carry out distinct functions in the assembly of branched actin networks during endocytosis. A similar division of duties may occur in other branched networks that contain multiple NPFs. Dissecting the biochemical underpinnings that allow multiple Arp2/3 complex regulators to coordinately regulate a single branched actin network will be critical for our understanding of complex cellular processes like endocytosis and cellular motility.

Experimental Procedures

Fission yeast Dip1, Arp2/3 complex, Wsp1-VCA, human SPIN90 (269-722), NWASp-VCA, and budding yeast Crn1 (WD-CC) were purified as described in the supplemental material. The GST affinity tag of Dip was cleaved for all experiments, unless otherwise noted in the figure legend. Arp2/3 complex used in assays was from S. pombe, unless otherwise indicated. Rabbit skeletal muscle actin was purified and labeled with either pyrene iodoacetamide, or Oregon Green 488 maleimide as described previously [43, 44]. Polymerization of pyrene actin was monitored as the increase in fluorescence at 407 nM as described previously [45]. The polymerization of Oregon Green 488 actin was monitored using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRF) essentially as previously described [6] with modifications detailed in the supplemental material. Details of other experimental procedures used can be found in the supplemental material.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Dip1 is a potent activator of Arp2/3 complex

Dip1-mediated activation of Arp2/3 complex does not require actin filaments

Dip1 mechanism may allow it to provide seed filaments for branched network assembly

The mechanism of Dip1 is conserved in the WISH/DIP/SPIN90 family

Acknowledgements

We thank Luke Helgeson for assistance with TIRF microscopy and Max-Rodnick Smith for assistance with cloning and protein purification. We also thank Ken Prehoda for critically reading the manuscript and Kathy Gould for the anti-SpArp3 antibody. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant RO1-GM092917 (to B.J.N) and the Pew Biomedical Scholar Program (to B.J.N). A.R.W. is funded by an NIH predoctoral training grant GM007759.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cooper JA, Buhle EL, Jr, Walker SB, Tsong TY, Pollard TD. Kinetic evidence for a monomer activation step in actin polymerization. Biochemistry. 1983;22:2193–2202. doi: 10.1021/bi00278a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesarone MA, Goode BL. Actin nucleation and elongation factors: mechanisms and interplay. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goley ED, Welch MD. The ARP2/3 complex: an actin nucleator comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:713–726. doi: 10.1038/nrm2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rotty JD, Wu C, Bear JE. New insights into the regulation and cellular functions of the ARP2/3 complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;14:7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chereau D, Kerff F, Graceffa P, Grabarek Z, Langsetmo K, Dominguez R. Actin-bound structures of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-homology domain 2 and the implications for filament assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16644–16649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507021102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hetrick B, Han MS, Helgeson LA, Nolen BJ. Small molecules CK-666 and CK-869 inhibit Arp2/3 complex by blocking an activating conformational change. Chem Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Achard V, Martiel JL, Michelot A, Guerin C, Reymann AC, Blanchoin L, Boujemaa-Paterski R. A “primer”-based mechanism underlies branched actin filament network formation and motility. Curr Biol. 2010;20:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwasa JH, Mullins RD. Spatial and temporal relationships between actin-filament nucleation, capping, and disassembly. Curr Biol. 2007;17:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skau CT, Courson DS, Bestul AJ, Winkelman JD, Rock RS, Sirotkin V, Kovar DR. Actin filament bundling by fimbrin is important for endocytosis, cytokinesis, and polarization in fission yeast. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26964–26977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.239004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchoin L, Pollard TD, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex-nucleated actin polymerization and branch formation by tropomyosin. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1300–1304. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DJ, Kim SH, Lim CS, Choi KY, Park CS, Sung BH, Yeo MG, Chang S, Kim JK, Song WK. Interaction of SPIN90 with the Arp2/3 complex mediates lamellipodia and actin comet tail formation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:617–625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504450200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukuoka M, Suetsugu S, Miki H, Fukami K, Endo T, Takenawa T. A novel neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) binding protein, WISH, induces Arp2/3 complex activation independent of Cdc42. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:471–482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu R, Chang F. Characterization of dip1p reveals a switch in Arp2/3- dependent actin assembly for fission yeast endocytosis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:905–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaksonen M, Toret CP, Drubin DG. Harnessing actin dynamics for clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrm1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sirotkin V, Berro J, Macmillan K, Zhao L, Pollard TD. Quantitative analysis of the mechanism of endocytic actin patch assembly and disassembly in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2894–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirotkin V, Beltzner CC, Marchand JB, Pollard TD. Interactions of WASp, myosin-I, and verprolin with Arp2/3 complex during actin patch assembly in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:637–648. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgs HN, Blanchoin L, Pollard TD. Influence of the C terminus of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) and the Arp2/3 complex on actin polymerization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15212–15222. doi: 10.1021/bi991843+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Padrick SB, Cheng HC, Ismail AM, Panchal SC, Doolittle LK, Kim S, Skehan BM, Umetani J, Brautigam CA, Leong JM, et al. Hierarchical regulation of WASP/WAVE proteins. Mol Cell. 2008;32:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu SL, Needham KM, May JR, Nolen BJ. Mechanism of a concentration-dependent switch between activation and inhibition of Arp2/3 complex by coronin. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:17039–17046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mockrin SC, Korn ED. Acanthamoeba profilin interacts with G-actin to increase the rate of exchange of actin-bound adenosine 5′-triphosphate. Biochemistry. 1980;19:5359–5362. doi: 10.1021/bi00564a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tseng PC, Pollard TD. Mechanism of action of Acanthamoeba profilin: demonstration of actin species specificity and regulation by micromolar concentrations of MgCl2. J Cell Biol. 1982;94:213–218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.94.1.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machesky LM, Mullins RD, Higgs HN, Kaiser DA, Blanchoin L, May RC, Hall ME, Pollard TD. Scar, a WASp-related protein, activates nucleation of actin filaments by the Arp2/3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodal AA, Manning AL, Goode BL, Drubin DG. Negative regulation of yeast WASp by two SH3 domain-containing proteins. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1000–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zalevsky J, Lempert L, Kranitz H, Mullins RD. Different WASP family proteins stimulate different Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin-nucleating activities. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blanchoin L, Amann KJ, Higgs HN, Marchand JB, Kaiser DA, Pollard TD. Direct observation of dendritic actin filament networks nucleated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP/Scar proteins. Nature. 2000;404:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35010008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ti SC, Jurgenson CT, Nolen BJ, Pollard TD. Structural and biochemical characterization of two binding sites for nucleation-promoting factor WASp-VCA on Arp2/3 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E463–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campellone KG, Webb NJ, Znameroski EA, Welch MD. WHAMM is an Arp2/3 complex activator that binds microtubules and functions in ER to Golgi transport. Cell. 2008;134:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DJ, Kim SH, Kim SM, Bae JI, Ahnn J, Song WK. F-actin binding region of SPIN90 C-terminus is essential for actin polymerization and lamellipodia formation. Cell Commun Adhes. 2007;14:33–43. doi: 10.1080/15419060701225010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin SG, Chang F. Dynamics of the formin for3p in actin cable assembly. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelham RJ, Jr., Chang F. Role of actin polymerization and actin cables in actin-patch movement in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:235–244. doi: 10.1038/35060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skau CT, Kovar DR. Fimbrin and tropomyosin competition regulates endocytosis and cytokinesis kinetics in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai R, Nakano K, Mabuchi I. Subcellular localization and possible function of actin, tropomyosin and actin-related protein 3 (Arp3) in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Eur J Cell Biol. 1998;76:288–295. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(98)80007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullins RD, Heuser JA, Pollard TD. The interaction of Arp2/3 complex with actin: nucleation, high affinity pointed end capping, and formation of branching networks of filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouiller I, Xu XP, Amann KJ, Egile C, Nickell S, Nicastro D, Li R, Pollard TD, Volkmann N, Hanein D. The structural basis of actin filament branching by the Arp2/3 complex. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:887–895. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodal AA, Kozubowski L, Goode BL, Drubin DG, Hartwig JH. Actin and septin ultrastructures at the budding yeast cell cortex. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:372–384. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young ME, Cooper JA, Bridgman PC. Yeast actin patches are networks of branched actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:629–635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urbanek AN, Smith AP, Allwood EG, Booth WI, Ayscough KR. A novel actin-binding motif in Las17/WASP nucleates actin filaments independently of Arp2/3. Curr Biol. 2013;23:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, Pollard TD. Actin Filament Severing by Cofilin Dismantles Actin Patches and Produces Mother Filaments for New Patches. Curr Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kovar DR, Sirotkin V, Lord M. Three’s company: the fission yeast actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weaver AM, Young ME, Lee WL, Cooper JA. Integration of signals to the Arp2/3 complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galletta BJ, Chuang DY, Cooper JA. Distinct roles for Arp2/3 regulators in actin assembly and endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacLean-Fletcher S, Pollard TD. Identification of a factor in conventional muscle actin preparations which inhibits actin filament self-association. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;96:18–27. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pollard TD. Polymerization of ADP-actin. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:769–777. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu SL, May JR, Helgeson LA, Nolen BJ. Insertions within the actin core of Actin-related protein 3 (Arp3) modulate branching nucleation by Arp2/3 complex. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.406744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.