ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Filipino Americans have high rates of hypertension, yet little research has examined hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in this group.

OBJECTIVE

In a community-based sample of hypertensive Filipino American immigrants, we identify 1) rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control; and 2) factors associated with awareness, treatment, and control.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional analysis of survey data from health screenings collected from 2006 to 2010.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 566 hypertensive Filipino immigrants in New York City, New York and Jersey City, New Jersey.

MAIN MEASURES

Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control. Participants were included in analysis if they were hypertensive, based on: a past physician diagnosis, antihypertensive medication use, and/or high blood pressure (BP) screening measurements. Demographic variables included sex, age, time in the United States, location of residence, and English spoken language fluency. Health-related variables included self-reported health, insurance status, diabetes diagnosis, high cholesterol diagnosis, clinical measures (body mass index [BMI], glucose, and cholesterol), exercise frequency, smoking status, cardiac event history, family history of cardiac event, and family history of hypertension.

RESULTS

Among the hypertensive individuals, awareness, treatment, and control rates were suboptimal; 72.1 % were aware of their status, 56.5 % were on medication, and only 21.7 % had controlled BP. Factors related to awareness included older age, worse self-reported health, family history of hypertension, and a diagnosis of high cholesterol or diabetes; factors related to treatment included older age, longer time lived in the United States, and being a non-smoker; having health insurance was found to be the main predictor of hypertension control. Many individuals had other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors; 60.4 % had a BMI ≥25, 12.0 % had at-risk glucose measurements and 12.8 % had cholesterol ≥ 240.

CONCLUSIONS

Hypertensive Filipinos exhibit poor hypertension management, warranting increased efforts to improve awareness, treatment and control. Culturally tailored public health strategies must be prioritized to reduce CVD risk factors among at-risk minority populations.

KEY WORDS: hypertension, community based participatory research, immigrant health, cardiovascular disease, race & ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

Hypertension, a modifiable risk factor for heart disease, stroke, and heart failure, continues to be a significant public health issue. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, nearly one in three noninstitutionalized adults in the United States (U.S.) have hypertension.1 Moreover, approximately 30 % of hypertensive adults are unaware of their hypertension; over 40 % of hypertensive individuals are not on treatment, and two-thirds of hypertensive individuals have not achieved blood pressure (BP) control.2 By increasing awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, morbidity and mortality associated with hypertension can be reduced.3

Of particular concern are the consistently high rates of hypertension among Filipinos, the third largest Asian American population in the U.S.4 The 2004–2006 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) found that Filipino adults were most likely to have ever been told that they had hypertension when compared to other Asian groups, with a prevalence of 27 %.5,6 Additionally, several regional studies conducted among Filipinos indicate that this population possesses a disproportionately higher burden of hypertension compared with whites and other Asian American groups.7–12 According to data from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination (NHANES), Filipinos have a 41 % prevalence of hypertension,3 a rate that is approaching that of black adults in the U.S. who have consistently been shown to have high BP.13–15

Despite the high burden of hypertension experienced by Filipinos, few published studies have examined awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among this group, and the existing research is not current.16,17 Further, research has focused on the West Coast of the U.S. and Hawaii, excluding the differential experiences of Filipino populations living in the Northeast U.S. Of the few cardiovascular studies including Filipino Americans, five have reported on antihypertensive medication use, and the only study to examine awareness, treatment and control of hypertensive was based on the 1979 California Hypertension Survey.7,17–20 This study found that the rate of uncontrolled hypertension among Filipinos was 24.5 %, despite the high rates of hypertension awareness (63 %) and hypertension treatment (49 %) among Filipinos.17 In regards to hypertension treatment, a study in Hawaii found that Filipinos were the least adherent Asian group.18

This study builds off the limited research on hypertension among Filipino Americans, and it is the first study to examine hypertension awareness, treatment, and control strictly among a Filipino sample in the Northeast U.S. The objectives of this paper are: 1) to identify the rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control among hypertensive Filipino Americans living in the New York (NY) metropolitan area; and 2) to examine the factors associated with awareness, treatment, and control among this group.

METHODS

Study Sample

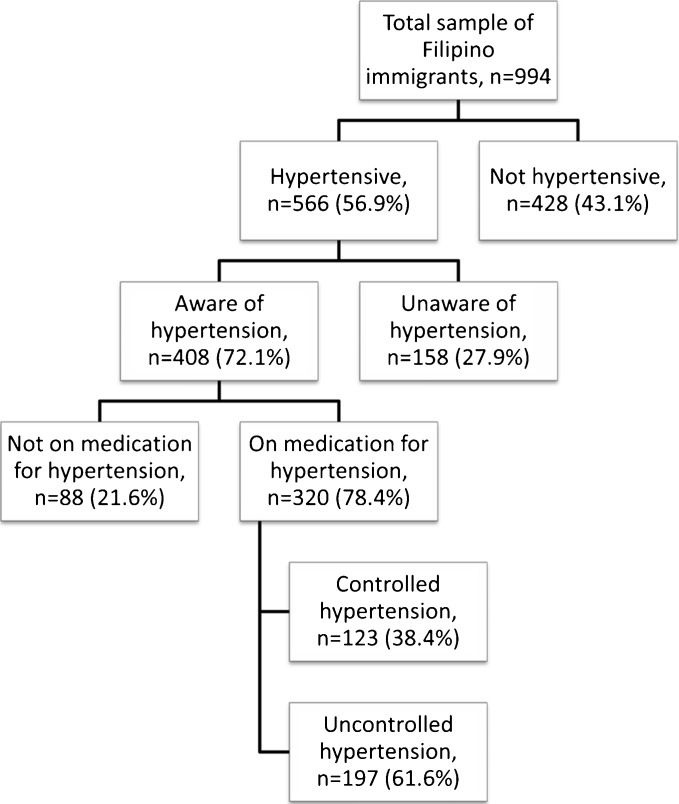

Data for this study were obtained from the recruitment phase of Project AsPIRE (Asian American Partnership in Research and Empowerment). The goal of AsPIRE is to utilize a community-based participatory research approach to implement a community health worker (CHW) hypertension management intervention among Filipinos in the NY metropolitan area. Convenience sampling methods were used for participant recruitment, occurring from June 2006 to May 2010 in Queens, NY and Jersey City, New Jersey (NJ). In order to increase the representativeness of target communities living in these areas, Geographic Information Systems mapping techniques were used to strategically sample in zip codes with large Filipino enclaves. Community health screenings were held at community-based organizations, faith-based organizations, cultural associations, restaurants, banks, shipping companies, consulate offices, schools, and parks. Screenings were advertised via flyers and through announcements given by community leaders. Trained bilingual staff explained the screening, obtained informed consent, and administered a survey to each participant, and CHWs and licensed clinical nurses obtained clinical measurements. A total of 994 foreign-born Filipino Americans aged 18 years or over were screened, answered questions on hypertension medication use and hypertension diagnosis, and had three consistent BP measurements taken. Of these individuals, 566 were hypertensive, comprising the sample for this manuscript (Fig. 1). A previous publication using this data defined hypertension using high BP readings and current hypertension medication, while the current study also included a self-reported hypertension diagnosis in the definition. Our current sample was smaller than the previous paper, due to the exclusion of individuals with missing responses to a self-reported hypertension diagnosis.21 This study was approved by the NYU Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Filipino Sample: Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control. The first box indicates the total sample of Filipino individuals. Boxes on subsequent lines indicate numbers and percentages of subgroups (hypertension, awareness of hypertension, medication for hypertension, and control of hypertension).

Survey Measures

Hypertensive individuals were divided into subgroups based on awareness, treatment, and control. Hypertension awareness was determined using the questions, “Has a doctor ever told you that you are hypertensive” and “Are you taking medication for hypertension?”; individuals answering “yes” to either question were defined as aware of hypertension, while individuals answering “no” or “don’t know”, but having a systolic BP (SBP) measurement ≥140 mmHg and/or a diastolic BP (DBP) measurement ≥90 mmHg were defined as unaware of hypertension. Hypertension treatment was determined for all individuals aware of their hypertension status using the question “Are you taking medication for hypertension?” Individuals answering “yes” were considered on treatment, while individuals answering “no” or “don’t know” were considered untreated. Hypertension control was determined for all individuals on treatment for hypertension; uncontrolled hypertension was defined as a SBP measurement ≥140 mmHg and/or a DBP measurement ≥90 mmHg, while controlled hypertension was defined as a SBP measurement of <140 mmHg and a DBP measurement of <90 mmHg. BP measurements were taken using Omron HEM-712C automatic BP monitors (Shelton, CT) with participants in a seated position. Three measurements were taken 3 min apart on a single day, and the means of the second and third measurements were used for all analyses.

Independent variables include demographic and health-related characteristics and clinical measurements. Demographic variables include gender, age, domicile (NY and NJ), years lived in the U.S., and English language capacity. Health-related characteristics include insurance status, self-rated health status, self-reported diagnoses of diabetes and high cholesterol, frequency of physical activity, cigarette smoking, and self-reported personal and family histories of cardiac events (heart attack, stroke, or coronary heart failure). Self-reported diagnoses of cholesterol and diabetes were combined for logistic regression. Clinical measurements include glucose, cholesterol, and body mass index (BMI). Glucose was classified as normal or at-risk; if an individual had fasted and had a glucose reading of ≥140 mm/dL, or if an individual had not fasted and had a glucose reading of ≥180 mg/dL, he or she was considered at risk for diabetes.22,23 Cholesterol was categorized into normal (< 200 mg/dL), elevated (200–239 mg/dL), and high (≥ 240 mg/dL).24 Standard BMI guidelines were used.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized using counts and percentages. Bivariate analyses were conducted for: 1) awareness among hypertensive individuals; 2) treatment among individuals aware of their hypertension; and 3) hypertension control among individuals on treatment for hypertension. Sample counts and percentages are presented across rows for each subgroup outcome (awareness, treatment, and control), and chi-square p values are given for each analysis. Associations for each subgroup outcome were assessed using separate multivariable logistic regression models. Each model was adjusted for age and gender in addition to variables found to be significant at p < 0.25 in bivariate analysis. Variables found to be significant at p < 0.05 once in the logistic regression model or with theoretical significance were kept in the final model; ORs and 95 % CIs were reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 describe the overall sample and provide bivariate analyses for awareness, treatment, and control. Table 1 includes all sociodemographic variables, and Table 2 includes all health-related variables.

Table 1.

Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control: Sociodemographic Variables

| Hypertensive | Awareness | Treatment | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Column %) | N (Row %) | N (Row %) | N (Row %) | |

| Total | 566 | 408 (72.1) | 320 (78.4) | 123 (38.4) |

| Gender | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.783 | |

| Male | 198 (35.3) | 130 (65.7) | 90 (69.2) | 36 (40.0) |

| Female | 363 (64.7) | 274 (75.5) | 227 (82.8) | 87 (38.3) |

| Age range | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.101 | |

| 18 to 45 | 95 (16.8) | 49 (51.6) | 19 (38.8) | 10 (52.6) |

| 46 to 55 | 151 (26.7) | 107 (70.9) | 73 (68.2) | 35 (47.9) |

| 56 to 65 | 189 (33.4) | 145 (76.7) | 126 (86.9) | 42 (33.3) |

| 66+ | 131 (23.1) | 107 (81.7) | 102 (95.3) | 36 (35.3) |

| Years lived in the U.S. | 0.560 | < 0.001 | 0.454 | |

| ≤ 5 years | 131 (25.4) | 91 (69.5) | 59 (64.8) | 19 (32.2) |

| 6 to 15 years | 175 (34.0) | 125 (71.4) | 92 (73.6) | 39 (42.4) |

| > 15 years | 209 (40.6) | 156 (74.6) | 141 (90.4) | 54 (38.8) |

| Domicile | 0.203 | 0.002 | 0.830 | |

| New York | 316 (56.2) | 221 (69.9) | 160 (72.4) | 62 (38.8) |

| New Jersey | 246 (43.8) | 184 (74.8) | 157 (85.3) | 59 (37.6) |

| Speaks english | 0.166 | 0.419 | 0.568 | |

| Yes | 535 (95.5) | 389 (72.7) | 303 (77.9) | 116 (38.3) |

| No | 25 (4.5) | 15 (60.0) | 13 (86.7) | 6 (46.2) |

| Insurance status | 0.016 | < 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| Insured | 280 (50.2) | 215 (76.8) | 183 (85.1) | 83 (45.4) |

| Uninsured | 278 (49.8) | 188 (67.6) | 132 (70.2) | 38 (28.8) |

Table 2.

Hypertension Aawareness, Treatment, and Control—Health-Related Variables

| Hypertensive | Awareness | Treatment | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (Column %) | N (Row %) | N (Row %) | N (Row %) | |

| Total | 566 | 408 (72.1) | 320 (78.4) | 123 (38.4) |

| Self-rated health status | 0.004 | 0.895 | 0.936 | |

| Excellent/Very good | 123 (22.0) | 77 (62.6) | 62 (80.5) | 25 (40.3) |

| Good | 278 (49.7) | 197 (70.9) | 154 (78.2) | 58 (37.7) |

| Fair/Poor | 158 (28.3) | 127 (80.4) | 99 (78.0) | 38 (38.4) |

| Self-reported diabetes | < 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.799 | |

| Yes | 88 (16.4) | 77 (87.5) | 70 (90.9) | 26 (37.1) |

| No | 391 (73.1) | 274 (70.1) | 204 (74.5) | 81 (39.7) |

| Don’t know | 56 (10.5) | 31 (55.4) | 24 (77.4) | 8 (33.3) |

| Self-reported high cholesterol | < 0.001 | 0.032 | 0.086 | |

| Yes | 247 (45.6) | 205 (83.0) | 170 (82.9) | 60 (35.3) |

| No | 198 (36.5) | 126 (63.6) | 91 (72.2) | 44 (48.4) |

| Don’t know | 97 (17.9) | 59 (60.8) | 42 (71.2) | 14 (33.3) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.355 | 0.079 | 0.925 | |

| Normal (< 25) | 212 (39.6) | 146 (68.9) | 107 (73.3) | 40 (37.4) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 253 (47.2) | 187 (73.9) | 156 (83.4) | 62 (39.7) |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 71 (13.2) | 54 (76.1) | 42 (78.8) | 16 (38.1) |

| Glucose | 0.332 | 0.229 | 0.608 | |

| Normal | 468 (88.0) | 331 (70.7) | 259 (78.2) | 97 (37.5) |

| At-Risk | 64 (12.0) | 49 (76.6) | 42 (85.7) | 14 (33.3) |

| Cholesterol | 0.206 | 0.341 | 0.873 | |

| Normal (< 200) | 343 (68.6) | 254 (74.1) | 205 (80.7) | 81 (39.5) |

| Borderline Risk (200–240) | 93 (18.6) | 64 (68.8) | 51 (79.7) | 20 (39.2) |

| High Risk (> 240) | 64 (12.8) | 41 (64.1) | 29 (70.7) | 10 (34.5) |

| Physical activity | 0.519 | 0.408 | 0.607 | |

| Does not exercise | 94 (16.8) | 64 (68.1) | 46 (71.9) | 16 (34.8) |

| Exercises 1–3 times a week | 212 (37.9) | 150 (70.8) | 120 (80.0) | 51 (42.5) |

| Exercises 4–7 times a week | 253 (45.3) | 187 (73.9) | 147 (78.6) | 56 (38.1) |

| Current smoker | 0.975 | < 0.001 | 0.068 | |

| Yes | 50 (9.9) | 36 (72.0) | 20 (55.6) | 11 (55.0) |

| No | 457 (90.1) | 330 (72.2) | 268 (81.2) | 93 (34.7) |

| Personal history of cardiac event | < 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.925 | |

| Yes | 32 (6.6) | 32 (100.0) | 31 (96.9) | 12 (38.7) |

| No/Don’t know | 455 (93.4) | 325 (71.4) | 245 (75.4) | 97 (39.6) |

| Family history of cardiac event | 0.003 | 0.200 | 0.622 | |

| Yes | 261 (48.5) | 202 (77.4) | 164 (81.2) | 62 (37.8) |

| No/Don’t know | 277 (51.5) | 182 (65.7) | 138 (75.8) | 56 (40.6) |

| Family history of hypertension | < 0.001 | 0.315 | 0.294 | |

| Yes | 381 (69.4) | 294 (77.2) | 227 (77.2) | 82 (36.1) |

| No/Don’t know | 168 (30.6) | 100 (59.5) | 82 (82.0) | 35 (42.7) |

| Hypertension Stages (column %) | ||||

| Stage 1 | 169 (47.5) | 156 (38.2) | 123 (38.4) | – |

| Stage 2 | 140 (24.7) | 95 (23.3) | 74 (23.1) | – |

Overall Sample

Among hypertensive individuals, 65 % were female, 41 % had lived in the U.S. for more than 15 years, 96 % spoke English, and 50 % were insured (Table 1). Ten percent were smokers and 69 % had a family history of hypertension. Approximately 47 % were overweight and 13 % were obese using standard World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, while 56 % were overweight and 26 % were obese when using Asian WHO guidelines (not shown).25 Additionally, 13 % had high cholesterol and 12 % had at-risk glucose levels (Table 2).

Awareness

Among hypertensive individuals, 72 % were aware of their hypertension status (Tables 1 and 2). In bivariate analysis, awareness of hypertension was found to significantly increase (p < 0.05) with female gender, older age, lower self-rated health, having health insurance, self-reported diabetes diagnosis, self-reported high cholesterol diagnosis, a personal history of a cardiac event, a family history of a cardiac event, and family history of hypertension.

While adjusting for all other factors in the model (Table 3), older age, fair or poor self-rated health status, a self-reported high cholesterol diagnosis, and a self-reported family history of hypertension were significantly associated with hypertension awareness. Individuals aged 66 years and over were 4.8 times more likely and individuals aged 56–65 were 2.8 times more likely to be aware of their hypertension compared to individuals aged 18–45 (p < 0.01, p < 0.001). Individuals self-rating their health as fair or poor were twice as likely to be aware of their hypertension compared to individuals self-rating their health as excellent or very good (p < 0.01). Additionally, individuals with a family history of hypertension were 2.7 times more likely than individuals without a family history of hypertension to be aware of their hypertension (p < 0.001), and individuals self-reporting high cholesterol or diabetes were 2.4 times more likely than individuals not reporting high cholesterol to be aware of their hypertension (p < 0.001). Once in regression, insurance was no longer significant.

Table 3.

Multivariable Predictors of Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension

| Awareness, OR (95 % CI) |

Treatment, OR 95 % CI) |

Control, OR (95 % CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Ref = male) | |||

| Female | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) |

| Age range (Ref = —45) | |||

| 46–55 | 1.9 (1.1–3.5)* | 3.6 (1.5–8.7)† | 0.8 (0.3–2.3) |

| 56–65 | 2.8 (1.5–5.1)† | 8.4 (3.4–21.0)‡ | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) |

| 66 and older | 4.8 (2.4–9.8)‡ | 19.0 (4.9–74.2)‡ | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) |

| Domicile (Ref = New York) | |||

| New Jersey | — | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) | — |

| Self-reported health (Ref = Excellent/very good) | |||

| Good | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | — | — |

| Fair/Poor | 2.1 (1.1–3.8)* | — | — |

| Insurance (Ref = Uninsured) | |||

| Insured | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | 2.1 (1.2–3.6)† |

| Years in the U.S. (Ref = ≤5 years) | |||

| 6–15 years | — | 1.6 (0.8–3.5) | — |

| > 15 years | — | 3.6 (1.4–9.3)* | — |

| Current smoker (Ref = Yes) | |||

| No | — | 3.4 (1.3–9.2)* | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) |

| Family history of hypertension (Ref = No/Don’t know) | |||

| Yes | 2.7 (1.7–4.3)‡ | — | — |

| Self-reported high cholesterol or diabetes (Ref = No/DK) | |||

| Yes | 2.4 (1.5–3.8)‡ | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) | — |

Ref indicates reference category

*P < 0.05

†P < 0.01

‡P < 0.001

Treatment

Of the 408 individuals aware of their hypertension, 78.4 % were on treatment (Tables 1 and 2). In bivariate analysis, treatment was found to significantly increase (p < 0.05) with female gender, older age, longer time in the U.S., living in NJ, having health insurance, not smoking, self-reported diabetes diagnosis, self-reported cholesterol diagnosis, and a personal history of a cardiac event.

While adjusting for all other factors in the model (Table 3), older age, having lived in the U.S. for 15 years or more, and not smoking were significantly associated with treatment. The likelihood of treatment increased significantly with age. Compared to individuals age 18–45, the likelihood of treatment was 8.4 times greater for those aged 56–65 years, and 19.0 times greater for those aged 66 and over (p < 0.001). Individuals living in the U.S. for 15 years or more were 3.6 times more likely than individuals living in the U.S. for 5 years or less to be on treatment (p < 0.05). Non-smokers were 3.4 times more likely than smokers to be on treatment (p < 0.05). Once in the model, self-reported high cholesterol and/or diabetes and insurance coverage were not significant.

Control

Of the 320 individuals on treatments for hypertension, 38.7 % had controlled hypertension (Tables 1 and 2). Additionally, 38.4 % of individuals had Stage 1 hypertension and 23.1 % of individuals had Stage 2 hypertension. In bivariate analysis, hypertension control was found to significantly increase (p < 0.05) with health insurance. Control was also found to increase among non-smokers, insured individuals, and younger individuals, but these associations were not significant at p < 0.05.

While adjusting for all other factors in the model (Table 3), health insurance was significantly associated with controlled hypertension. Insured individuals were two times more likely than uninsured individuals to have controlled hypertension (p < 0.01). Smoking was included in the regression model, but was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Using data from community health screenings in the Filipino community in the NY metropolitan area, these findings offer valuable information on awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in this population. Our results show that while the majority of hypertensive individuals were aware of their hypertension status, 28 % of hypertensive individuals were unaware that they had high BP. Hypertension control among individuals on medication for hypertension was very low; only 38.4 % of treated individuals had achieved BP control and 23.1 % had Stage 2 hypertension. Additionally, a large percentage of hypertensive individuals had other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors; 60.4 % of individuals were overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25), 12.0 % had at-risk glucose measurements, and 12.8 % had cholesterol ≥240.

While previous hypertension research has focused on minority groups such as African Americans and Hispanics,26–28 this is the first study to examine awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among Filipino Americans. One previous study in NYC examined these outcomes and included an Asian group, but all Asian subgroups were aggregated due to small sample size.29 Poor control among individuals on medication for hypertension is of particular concern; while 78 % of aware individuals were taking medication for hypertension, the rate of control (38.4 %) was lower than the rate previously seen among African Americans, Mexican Americans, and whites.26–28 A qualitative study examining 27 uninsured hypertensive Filipino immigrants found that forgetfulness, time constraints, ethnic/cultural practices, stress, and medication side effects contributed to non-adherence and uncontrolled hypertension.19

The rate of hypertension awareness (72.1 %) among Filipino Americans in this study was lower than the unadjusted rate for NYC overall (83.0 %), as well as other minority populations in NYC, including non-Hispanic Blacks (85.5 %), Hispanics (81.9 %), and Asians overall (78.3 %).29 The treatment rate among hypertensive Filipino Americans (56.5 %) was also much lower when compared to NYC overall (72.7 %), non-Hispanic Blacks (71.9 %), Hispanics (72.2 %), and Asians overall (73.2 %).29 In our sample, only 21.7 % of hypertensive individuals exhibited hypertension control, a rate nearly half that of hypertensive adults in NYC overall (47.1 %), as well as Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks (both 46.8 %), and Asians overall (39.9 %).29

Similar to previous research in Filipino and other ethnic groups, older age was associated with a greater awareness of hypertension and treatment for hypertension,18,27 having health insurance was associated with greater BP control,15,27,30 lower self-rated health and comorbidities were associated with greater awareness of hypertension,15,26 and smoking cigarettes was associated with not being on treatment for hypertension.15 A family history of hypertension was significantly associated with awareness of hypertension, and longer time lived in the U.S. was associated with treatment for hypertension. Half of our sample was uninsured, and 60 % were recent immigrants, having lived in the U.S. for 15 years or less. A previous study using New York City Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NYC HANES) data found that non-Hispanic Asians and foreign-born adults living in the U.S. for less than 10 years were less likely to have a routine place of care than adults living in the U.S. for longer.31

An important strength of this study is the large, community-based sample from which the data was taken. Recent epidemiological studies have relied on pooled data to form sufficient sizes of Asian American subgroups (e.g. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), and the Veteran Affairs Medical Centers records).26,29,32 The data for our study was drawn from a community-based sample of Filipino Americans at health screening events around the NY Metropolitan area. Measurements were taken directly by CHWs and licensed clinical nurses and reflect an exact measurement as opposed to self-reported diagnoses of hypertension. Additionally, insured and uninsured individuals were captured. Past hypertension studies have relied on data collected from hospitals and insurance plans, limiting the generalizability to insured individuals.32–34 Our sample also represents the NY metropolitan area, which includes NYC and Jersey City, NJ, where large numbers of Filipinos reside along the Northeast coast of the U.S..4

Several limitations should be mentioned. First, the use of convenience sampling limits the generalizability of these findings to the larger Filipino population. Second, measures of awareness (treatment and past diagnoses of hypertension) were collected via participants’ self-report, as opposed to hospital records or requiring individuals to bring in medication bottles.15,18,20 Third, our screening survey did not include several important variables, including educational attainment, income, routine sources of health care, and knowledge regarding hypertension, which other studies have shown to be predictors of awareness, treatment, and control.18,29,32,35,36 Finally, white coat hypertension could modify the prevalence of hypertension in the unaware group, since hypertension was defined using 1 day of BP readings.2 Following recommendations, we took repeated measurements that were at least 3 min apart and used the last two out of three measurements to reduce the chance of wrongly detecting hypertension.37

In summary, our study demonstrates high rates of hypertension and low rates of control among Filipino immigrants living in the NY metropolitan area. The prevalent CVD risk factors in this population, such as high BMI, high rates of self-reported diabetes and high cholesterol, and current cigarette smoking, suggest the need for approaches designed to manage multiple risk factors, such as behavioral interventions that address physical activity and diet. The finding that insured individuals were twice as likely to exhibit hypertension control when compared to uninsured individuals suggests the importance of health insurance in the control of hypertension. The health insurance mandate under the Affordable Care Act introduces opportunities for currently uninsured hypertensive individuals to afford and enroll in health insurance.38 Additionally, the American Heart Association recommends that states and certain localities develop surveillance capacity that would include direct the assessment of “awareness, detection, treatment, and control of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes.”29 Although requiring extensive efforts, community organizing is one type of approach to reach a large community-based population in order to provide mechanisms for individuals to access necessary healthcare resources for hypertension management. Such healthcare access will ideally improve levels of awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in populations experiencing cardiovascular health disparities.

Acknowledgements

This publication would not be possible without the support of the staff, members, and leadership of the Kalusugan Coalition, Inc., who have given their time and expertise in designing and implementing this project. The authors would also like to thank the community health workers for their contributions in engaging stakeholders and recruiting study participants: Romerico Foz, Leonida Gamboa, Yves Nibungco, Hanalei Ramos, Henry Soliveres. The authors are especially grateful to all the community members who participated in the study.

This publication was made possible by Grant Number R24MD001786 from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIH NIMHD), and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH NIMHD.

Preliminary findings from this work were previously presented at the 2011 American Public Health Association conference in Washington, D.C.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008;8:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289(19):2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostchega Y, Yoon SS, Hughes J, Louis T. Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control—continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2008;3:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 3-Year Estimates, 2008–2010.

- 5.Barnes PM, Adams PF, Powell-Griner E. Health characteristics of the Asian adult population: United States, 2004–2006. Adv Data. 2008;394:1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ye J, Rust G, Baltrus P, Daniels E. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans: results from a National Health Survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(10):718–723. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araneta MR, Barrett-Connor E. Subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic Filipino and white women. Circulation. 2004;110(18):2817–2823. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146377.15057.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klatsky AL, Tekawa IS, Armstrong MA. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(Suppl 2):62–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klatsky AL, Armstrong MA. Cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans living in northern California. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(11):1423–1428. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.81.11.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu TY, Hsieh HF, Wang J, Yao L, Oakley D. Ethnicity and cardiovascular risk factors among Asian Americans residing in Michigan. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):811–818. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown DE, James GD. Physiological stress responses in Filipino-American immigrant nurses: the effects of residence time, life-style, and job strain. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(3):394–400. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan C, Shaw R, Pliam M, Zapolanski AJ, Murphy M, Valle HV, Myler R. Coronary heart disease in Filipino and Filipino-American patients: prevalence of risk factors and outcomes of treatment. J Invasive Cardiol. 2000;12(3):134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Wang QJ. The prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension among US adults according to the new joint national committee guidelines: new challenges of the old problem. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(19):2126–2134. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.19.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis AM, Vinci LM, Okwuosa TM, Chase AR, Huang ES. Cardiovascular health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5 Suppl):29S–100S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyatt SB, Akylbekova EL, Wofford MR, Coady SA, Walker ER, Andrew ME, Keahey WJ, Taylor HA, Jones DW. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2008;51(3):650–656. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.100081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stavig GR, Igra A, Leonard AR. Hypertension among Asians and Pacific islanders in California. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(5):677–691. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stavig GR, Igra A, Leonard AR. Hypertension and related health issues among Asians and Pacific Islanders in California. Public Health Rep. 1988;103(1):28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taira DA, Gelber RP, Davis J, Gronley K, Chung RS, Seto TB. Antihypertensive adherence and drug class among Asian Pacific Americans. Ethn Health. 2007;12(3):265–281. doi: 10.1080/13557850701234955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.dela Cruz FA, Galang CB. The illness beliefs, perceptions, and practices of Filipino Americans with hypertension. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(3):118–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magno CP, Araneta MR, Macera CA, Anderson GW. Cardiovascular disease prevalence, associated risk factors, and plasma adiponectin levels among Filipino American women. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):458–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ursua RA, Islam NS, Aguilar DE, Wyatt LC, Tandon SD, Abesamis-Mendoza N, Nur PR, Rago-Adia J, Ileto B, Rey MJ, Trinh-Shevrin C. Predictors of hypertension among Filipino immigrants in the Northeast US. J Community Health. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Mayo Clinic. Type 2 diabetes: Tests and diagnosis 2012. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/type-2-diabetes/ds00585/dsection=tests-and-diagnosis.

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Living With Diabetes: Checking Your Blood Glucose. http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/treatment-and-care/blood-glucose-control/checking-your-blood-glucose.html.

- 24.Mayo Clinic. High cholesterol 2011. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/cholesterol-levels/CL00001.

- 25.The WHO Expert Consultation Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victor RG, Leonard D, Hess P, Bhat DG, Jones J, Vaeth PA, Ravenell J, Freeman A, Wilson RP, Haley RW. Factors associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in Dallas County, Texas. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bersamin A, Stafford RS, Winkleby MA. Predictors of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control among Mexican American women and men. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 3):521–527. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, Saunders E. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(18):2098–2104. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angell SY, Garg RK, Gwynn RC, Bash L, Thorpe LE, Frieden TR. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and predictors of control of hypertension in New York City. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1(1):46–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.791954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker G. Effects of being uninsured on ethnic minorities’ management of chronic illness. West J Med. 2001;175(1):19–23. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.175.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen QC, Waddell EN, Thomas JC, Huston SL, Kerker BD, Gwynn RC. Awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia among insured residents of New York City, 2004. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(5):A109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knight EL, Bohn RL, Wang PS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J. Predictors of uncontrolled hypertension in ambulatory patients. Hypertension. 2001;38(4):809–814. doi: 10.1161/hy0901.091681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeVore AD, Sorrentino M, Arnsdorf MF, Ward RP, Bakris GL, Blankstein R. Predictors of hypertension control in a diverse general cardiology practice. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(8):570–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2010.00298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stockwell DH, Madhavan S, Cohen H, Gibson G, Alderman MH. The determinants of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in an insured population. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(11):1768–1774. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.84.11.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ong KL, Cheung BM, Man YB, Lau CP, Lam KS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):69–75. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000252676.46043.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morenoff JD, House JS, Hansen BB, Williams DR, Kaplan GA, Hunte HE. Understanding social disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control: the role of neighborhood context. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1853–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mallion JM, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Padfield P, Palatini P, Parati G, Pickering T, Redon J, Staessen J, Stergiou G, Verdecchia P. European society of hypertension working group on blood pressure M. European society of hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2003;21(5):821–848. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez J, Ro M, Villa NW, Powell W, Knickman JR. Transforming the delivery of care in the post-health reform era: what role will community health workers play? Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):e1–e5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]