Abstract

Introduction

Micro-invasive glaucoma surgical implantation of trabecular micro-bypass stents, previously shown to be safe and effective for open-angle glaucoma (OAG) subjects during cataract surgery, was considered for evaluation as a sole procedure. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and intraocular pressure (IOP)-lowering efficacy after ab interno implantation of two Glaukos Trabecular Micro-Bypass iStent inject second generation devices in subjects with OAG. This study was performed at sites in France, Germany, Italy, Republic of Armenia, and Spain.

Methods

In this pan-European, multi-center prospective, post-market, unmasked study, 99 patients with OAG on at least two topical ocular hypotensive medications who required additional IOP lowering to control glaucoma disease underwent implantation of two GTS400 stents in a stand-alone procedure. Patients were qualified if they presented with preoperative mean IOP between 22 and 38 mmHg after medication washout. Postoperatively, subjects were assessed at Day 1, Months 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, and 12. IOP, medication use and safety were assessed at each visit.

Results

Sixty-six percent of subjects achieved IOP ≤18 mmHg at 12 months without medication, and 81% of subjects achieved Month 12 IOP ≤ 18 mmHg with either a single medication or no medication. Mean baseline washout IOP values decreased by 10.2 mmHg or 39.7% from 26.3 (SD 3.5) mmHg to 15.7 (SD 3.7) mmHg at Month 12. Mean IOP at 12 months was 14.7 (SD 3.1) mmHg in subjects not using ocular hypotensive medications. Reduction from preoperative medication burden was achieved in 86.9% of patients, including 15.2% with reduction of one medication and 71.7% with reduction of two or more medications. Postoperative complications occurred at a low rate and resolved without persistent effects.

Conclusion

In this series, implantation of two trabecular micro-bypass second generation stents in subjects with OAG resulted in IOP and medication reduction and favorable safety outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0095-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ab interno, Intraocular pressure, iStent inject, Open-angle glaucoma, Ophthalmology, Trabecular bypass

Introduction

Glaucoma, the second leading cause of blindness in the world, requires chronic, life-long treatment with an array of therapeutic options available including medications, laser treatment and surgical implants [1, 2]. The common therapeutic goal of surgical treatment for this progressive and debilitating disease is to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) to target levels to prevent loss of visual field, while enabling patients to recover faster and with fewer complications [2]. An ideal procedure for the treatment of open-angle glaucoma (OAG) would restore physiologic outflow and decrease IOP using a minimally invasive approach. Limitations and safety considerations of the multitude of therapies has prompted the development of a safer, less invasive treatment for glaucoma designed to prevent the need for trabeculectomy or other invasive procedures associated with significant damage to intraocular and extraocular structures and resulting significant postoperative complications.

The advent of micro-invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) using ab interno trabecular micro-bypass stents has been shown to be safe and effective for mild–moderate glaucoma subjects in conjunction with cataract surgery [3–5]. These stents bypass the trabecular meshwork, which is considered the primary source of resistance to aqueous drainage in many glaucomas, in order to improve outflow through the natural physiologic pathway and reduce IOP [3, 6–8]. MIGS has the potential to preserve important eye tissue and future treatment options that may help maintain long-term vision for the patient with glaucoma [9]. The first generation iStent Trabecular Micro-Bypass (Glaukos Corp., Laguna Hills, CA, USA) has demonstrated the capability of providing a safe and effective way to lower IOP in patients with mild-to-moderate glaucoma. Multiple studies have demonstrated long-term safety and effectiveness of iStent in conjunction with or without cataract surgery to reduce IOP and medication burden for up to 5 years postoperative [3–5, 10–12].

A new micro-scale stent, the Model GTS400 iStent inject (Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, USA), is a second generation device developed to reduce IOP in a safe and effective way, similar to that of the iStent. The iStent inject is CE marked in Europe. Recent work by Bahler et al. [13, 14] entailed a prospective laboratory investigation using the iStent inject in human donor eyes and found that the addition of a second stent further increased outflow facility beyond the initial increase from placement of the first stent, a finding consistent with their work on the first generation stent. In parallel to the investigation of multiple stent insertion, an initial injector system, the Model G2-0 injector (Glaukos Corporation), was designed to enable implantation of iStent inject devices one at a time. A second generation injector, the Model G2-M-IS system (Glaukos Corporation), was then developed to house two stents, providing the clinician the ability to insert multiple stents while entering the eye only once.

The goal of this work was to examine outcomes after implantation of multiple trabecular bypass stents in OAG by increasing conventional outflow, and to determine the additive effect of a drug to increase uveoscleral outflow if needed to further reduce IOP. This report summarizes data from patients who underwent implantation of the second generation GTS-400 iStent inject device via either the Model G2-0 injector or the Model G2-M-IS Injector as a sole procedure.

Methods

Subject Screening and Inclusion

This prospective, open-label study involved iStent implantation and follow-up of phakic or pseudophakic subjects with OAG (including primary, pigmentary, and pseudoexfoliative) on at least two topical ocular hypotensive medications, who in the opinion of the investigator, required additional IOP lowering to control their OAG. The study was conducted at sites in France, Germany, Italy, Republic of Armenia, and Spain. A list of participating investigators and site affiliation is provided in Appendix 1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material. Appendix 2, in the Electronic Supplementary Material, lists the number of subjects at each site. The study protocol was approved by ethical committees at each of the study sites. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. The clinical trial registration number is NCT00911924 (Clinicaltrials.gov).

Inclusion criteria included subjects at least 18 years of age who had been using at least two IOP-lowering medications for at least 3 months but still required additional IOP lowering, with visual field defects or nerve abnormality characteristic of glaucoma, preoperative best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/200 or better, and ability and willingness to provide informed consent and attend follow-up visits through 1 year postoperative. Subjects were required to have an untreated mean IOP of at least 22 mmHg and <38 mmHg at screening baseline visit after washout of medications. Exclusion criteria included subjects known to be non-responders to latanoprost and with glaucoma other than OAG, angle closure glaucoma, secondary glaucoma (except pseudoexfoliative and pigmentary), eyes with prior stent or shunt implantation, argon laser trabeculoplasty or selective laser trabeculoplasty within 90 days of screening visit, peripheral anterior synechiae, prior iridectomy or laser iridotomy, active corneal inflammation or edema, prior corneal surgery, corneal opacities/disorders inhibiting visualization of the nasal angle, elevated episcleral venous pressure, and chronic or active ocular inflammation.

Following the informed consent process, a comprehensive screening examination was performed that included best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), slit-lamp biomicroscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and measurement of IOP (Goldmann applanation). At most sites, IOP measurements were taken by the same operator using the same tonometer each time. Tonometers were calibrated monthly.

Subjects selected for the trial began a washout of all glaucoma medications (4 weeks for prostaglandin analogs and beta-blockers, 2 weeks for alpha adrenergic agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors). At baseline, the subjects’ BCVA (via Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study system [15]), cup-to-disc ratio (C:D), central corneal thickness and IOP were measured. Un-medicated diurnal IOP measurements were taken at selected sites at 8 am, 10 am, 12 pm, and 4 pm (±1 h).

iStent Inject Device

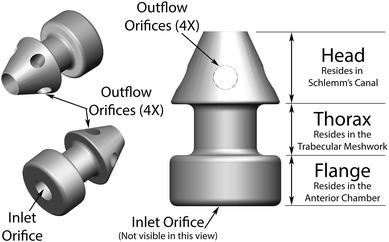

The micro-bypass iStent inject device GTS400 is a single-piece, heparin-coated, gamma-sterilized device made from implant-grade titanium. The one-piece device is 360 μm in length, and the maximal width of the conical head is 230 μm. The stent is symmetrically designed such that it may be used in either the right or left eye. The iStent inject is smaller than the first generation iStent, but functions in the same way to bypass the trabecular meshwork to improve aqueous flow from the anterior chamber into Schlemm’s canal. The iStent inject devices are pre-loaded in the customized injector system designed to deliver the stents automatically into Schlemm’s canal through a stainless steel insertion tube. The injector features a surgeon-activated release button on the housing, which is pressed to allow the stent to move over a small guiding trocar to exit the injector. The G2-0 injector housed one stent; therefore, two injectors were used during implantation. The G2-M-IS system houses two stents, thereby enabling insertion of both stents from one injector. A diagram of the iStent inject is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Trabecular Micro-Bypass Stent Model GTS400

Surgery and Follow-up

Two iStent inject devices were implanted through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal at the nasal position, separated by approximately two clock hours, using topical anesthesia and stent insertion methods similar to those described previously [16]. Following implantation of two iStents, subjects received topical postoperative anti-inflammatory and anti-infective medications for 4 weeks.

Follow-up visits were scheduled at Day 1, Months 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, and 12. Postoperative examination parameters were similar to preoperative parameters. In addition, postoperative diurnal IOP was measured at selected sites at Month 6, Month 9, and Month 12 exams at the same time points (8 am, 10 am, 12 pm, and 4 pm) as the baseline exam. At Month 6, subjects whose IOP was greater than or equal to 18 mmHg were prescribed latanoprost for the next 6 months. The study protocol further indicated that if at any time during the study, a subject’s IOP exceeded 38 mmHg, the subject would be exited from the study and alternative treatment commenced at the discretion of the investigator.

Study Endpoints and Statistical Analysis

The primary efficacy endpoint was defined as the proportion of subjects with IOP of ≤18 mmHg without the use of ocular hypotensive medications at Month 12. The secondary efficacy endpoint was defined as the proportion of subjects with IOP ≤ 18 mmHg regardless of ocular hypotensive medications at Month 12. Subjects not included in the responder analysis at Month 12 either did not have IOP data available at Month 12 or underwent secondary surgical intervention that could affect IOP (e.g., incisional or laser surgery, cataract surgery, or postoperative procedure to reposition or remove the stent) prior to Month 12. Safety analyses involved assessment of adverse events, BCVA, slit lamp findings, and pachymetry.

The subject population in this trial included qualified subjects who underwent implantation of two GTS-400 iStent inject devices with either insertion device, the G2-0 injector or the G2-M-IS system. The safety and efficacy data comprise all study subjects (regardless of insertion device) because the implanted stents are identical in all cases. For the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints, proportional analyses were performed. Exact 95% confidence intervals based on a binomial distribution were calculated for the responder rates. For continuous variables such as mean IOP and IOP reduction, 95% confidence intervals were computed using the t-distribution. Statistical tests were performed using PC-SAS software (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Subject Disposition and Demographics

A total of 112 subjects were enrolled in the study. One subject did not have baseline information recorded and eight subjects did not have at least two medications at screening. Four enrolled subjects did not undergo implantation of two devices. These 13 subjects were not included in the analysis, resulting in a total of 99 subjects analyzed. This group of 99 subjects consisted of 72 cases in which the G2-0 injector was employed, while the remaining 27 cases underwent insertion via the G2-M-IS system. Of the 99 subjects implanted with devices, 92 subjects were available at the Month 12 visit and 7 subjects did not complete the Month 12 visit (Table 1). Another 4 subjects had undergone secondary surgical interventions by the Month 12 visit. Therefore, data from 88 subjects were included in the analysis of efficacy endpoints.

Table 1.

Subject accountability

| Subject status | Screening | Baseline | Day 1 | Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 7 | Month 9 | Month 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All implanted eyes | |||||||||

| Available at visit | 99 | 99 | 98 | 91 | 96 | 93 | 87 | 93 | 92 |

Demographics for the study population are presented in Table 2. The mean age at enrollment was 66.4 years ± 10.9 (SD). Fifty-six subjects (57.0%) were female. There were 40 right eyes and 59 left eyes. Eight-two eyes (83.0%) were phakic. The mean C:D ratio was 0.7 ± 0.2 (SD). Subjects were taking an average of 2.21 medications; with beta-blockers used in 80.8% of eyes, followed by prostaglandin analogs (61.6% of eyes), carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (56.6%), alpha agonists (18.2%), and miotics (pilocarpine; 4.0%). Mean medicated IOP at screening was 22.1 mmHg ± 3.3 (SD) and mean IOP following medication washout was 26.3 mmHg ± 3.5 (SD).

Table 2.

Demographic and preoperative characteristics

| Variable | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Subjects analyzed (N) | 99 |

| Mean age (years) ± SD | 66.4 ± 10.9 |

| Range | 34–94 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 (43%) |

| Female | 56 (57%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 95 (96%) |

| Eye | |

| Right | 40 (40%) |

| Left | 59 (60%) |

| Additional glaucoma diagnosis | |

| Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma | 3 (3.0%) |

| Lens status | |

| Phakic | 82 (83%) |

| Pseudophakic | 17 (27%) |

| Mean C:D ratio ± SD | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Mean # medications (SD) | 2.21 (0.44) |

| # Medications by classa | |

| Alpha agonist | 18 (18.2%) |

| Beta blocker | 80 (80.8%) |

| Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor | 56 (56.6%) |

| Prostaglandin analog | 61 (61.6%) |

| Miotic (pilocarpine) | 4 (4.0%) |

| Mean medicated IOP (mmHg) | 22.1 ± 3.3 |

| Mean pachymetry (μm) | 541.0 ± 38.1 |

| Mean post-washout IOP (mmHg) | 26.3 ± 3.5 |

C:D cup:disc ratio, IOP intraocular pressure

aSubjects could be on two or more medications

Intraocular Pressure and Medication Use

The primary endpoint, IOP ≤ 18 mmHg at 12 months without medications, was achieved by 66% of subjects (n = 58 of 88 eyes; 95% CI 55%, 76%; Table 3). The secondary endpoint, IOP ≤ 18 mmHg at 12 months regardless of medications was achieved by 81% of subjects (n = 71 of 88 eyes; 95% CI 71%, 88%), of which 12 subjects were using a prostaglandin at Month 12. Furthermore, 72% of subjects (n = 63, 95% CI 61%, 81%) experienced a 20% or greater reduction in IOP without medication at 12 months, 93% (n = 82, 95% CI 86%, 97%) experienced a 20% or greater reduction in IOP regardless of medication at 12 months, and 77% (n = 68, 95% CI 67%, 86%) achieved IOP reduction of 30% or more.

Table 3.

Proportional analysis of IOP over time

| IOP | Baseline washout, n (%)a | Month 1, n (%) | Month 3, n (%) | Month 6, n (%)a | Month 7, n (%) | Month 9, n (%)a | Month 12, n (%) 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (IOP available) | 99 | 91 | 96 | 93 | 87 | 93 | 92 |

| N | 99 | 91 | 94 | 89 | 82 | 88 | 88 |

| IOP ≤ 18 mmHg without Meds | 0 (0%) | 61 (67%) | 62 (66%) | 54 (61%) | 61 (74%) | 63 (72%) | 58 (66%) (55%, 76%) |

| IOP ≤ 18 mmHg regardless of Meds | 0 (0%) | 63 (69%) | 69 (73%) | 60 (67%) | 72 (88%) | 77 (88%) | 71 (81%) (71%, 88%) |

| Decrease ≥ 20% without Meds | 70 (77%) | 71 (76%) | 62 (70%) | 64 (78%) | 66 (75%) | 63 (72%) (61%, 81%) | |

| Decrease ≥ 30% without Meds | 60 (66%) | 57 (61%) | 52 (58%) | 56 (68%) | 58 (66%) | 54 (61%) (50%, 72%) | |

| Decrease ≥ 20% regardless of Meds | 73 (80%) | 83 (88%) | 72 (81%) | 77 (94%) | 82 (93%) | 82 (93%) (86%, 97%) | |

| Decrease ≥ 30% regardless of Meds | 63 (69%) | 68 (72%) | 62 (70%) | 66 (80%) | 71 (81%) | 68 (77%) (67%, 86%) | |

| SSIb | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

IOP intraocular pressure, SSI secondary surgical intervention

aDiurnal IOP was taken for the visit at selected sites

bSSI related to glaucoma. Outcomes after SSI were excluded

Mean IOP at the 6-month visit was 16.8 ± 4.1 mmHg (95% CI 15.9, 17.7; Table 4). At this visit, 24.4% (n = 23) were administered medication for additional IOP control. By the 12-month visit, mean IOP was 15.7 ± 3.7 mmHg (95% CI 14.9, 16.5) in all 88 subjects, representing a 10.2 mmHg or 39.7% decrease from baseline washout IOP. Mean IOP at Month 12 was 14.7 ± 3.1 mmHg (95% CI 14.0, 15.5) in the 66 subjects not using ocular hypotensive medication. At Month 12, 86.9% of subjects had reduced their medication burden, including 15.2% with reduction of one medication, and 71.7% with reduction of two or more medications (53.5% reduced by 2, 17.2% reduced by 3, and 1% reduced by 4 medications, respectively).

Table 4.

Mean IOP over time

| IOP | Screening, n (%) | Baseline washout, n (%)a | Month 1, n (%) | Month 3, n (%) | Month 6, n (%)a | Month 7, n (%) | Month 9, n (%)a | Month 12, n (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean IOP—all eyes | ||||||||

| N (IOP available) | 99 | 99 | 91 | 96 | 93 | 87 | 93 | 92 |

| N b | 99 | 99 | 91 | 94 | 89 | 82 | 88 | 88 |

| Mean | 22.1 | 26.3 | 17.0 | 16.6 | 16.8 | 15.8 | 15.5 | 15.7 |

| SD | 3.3 | 3.5 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.7 |

| 95% CI | 21.5, 22.8 | 25.7, 27.0 | 15.7, 18.4 | 15.7, 17.6 | 15.9, 17.7 | 15.1, 16.5 | 14.9, 16.1 | 14.9, 16.5 |

| Min | 16.0 | 22.3 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 9.8 |

| Max | 33.0 | 38.2 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 29.8 | 30.0 | 28.0 | 29.5 |

| Mean IOP—eyes without medication at Month 12 | ||||||||

| IOP | ||||||||

| N | 74 | 74 | 66 | 71 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 66 |

| Mean | 22.2 | 25.6 | 15.0 | 15.5 | 15.8 | 15.0 | 14.5 | 14.7 |

| SD | 3.4 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.1 |

| 95% CI | 21.4, 22.9 | 24.9, 26.3 | 13.8, 16.2 | 14.6, 16.4 | 14.9, 16.8 | 14.4, 15.5 | 14.0, 15.1 | 14.0, 15.5 |

| Min | 16.0 | 22.3 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 9.8 |

| Max | 33.0 | 38.2 | 30.0 | 27.0 | 24.8 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 23.3 |

| IOP change from baseline—eyes without medication at Month 12 | ||||||||

| N | 74 | 74 | 66 | 71 | 67 | 65 | 66 | 66 |

| Mean | −10.8 | −10.0 | −9.5 | −10.4 | −10.6 | −10.4 | ||

| SD | 4.8 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 | ||

| 95% CI | −12.0, −9.6 | −10.9, −9.1 | −10.3, −8.6 | −11.1, −9.6 | −11.4, −9.9 | −11.2, −9.6 | ||

| Min | −21.2 | −25.2 | −17.8 | −19.0 | −19.8 | −18.3 | ||

| Max | 2.3 | 0.0 | −2.0 | −4.3 | −4.3 | −1.5 | ||

IOP intraocular pressure, SSI secondary surgical intervention

aDiurnal IOP was taken for the visit at selected sites

bOutcomes after SSI were excluded

Best Corrected Visual Acuity, Slit-Lamp, Pachymetry

The proportion of subjects with BCVA of 20/40 or better was 84% at screening, 84% at 1 and 3 months, 88% at 6 months and 86% at 12 months (Table 5). The mean C:D ratio at Month 12 was 0.7 ± 0.2, and did not change versus preoperative C:D ratio. Mean central corneal thickness was stable over time as well with 541.4 ± 38.1 μm reported at screening versus 537.0 ± 35.3 μm at 12 months.

Table 5.

Best corrected visual acuity over time

| BCVA | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 7 | Month 9 | Month 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/20 or better | 42 (42%) | 35 (39%) | 40 (43%) | 42 (46%) | 43 (50%) | 40 (43%) | 43 (47%) |

| 20/40 or better | 83 (84%) | 75 (84%) | 79 (84%) | 80 (88%) | 74 (86%) | 80 (86%) | 79 (86%) |

| 20/80 or better | 93 (94%) | 83 (93%) | 90 (96%) | 87 (96%) | 81 (94%) | 88 (95%) | 88 (96%) |

| 20/100 or better | 94 (95%) | 85 (96%) | 92 (98%) | 89 (98%) | 83 (97%) | 89 (96%) | 90 (98%) |

| 20/200 or better | 99 (100%) | 89 (100%) | 94 (100%) | 91 (100%) | 86 (100%) | 92 (99%) | 92 (100%) |

| 20/400 or better | 99 (100%) | 89 (100%) | 94 (100%) | 91 (100%) | 86 (100%) | 93 (100%) | 92 (100%) |

| Worse than 20/400 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| N (BCVA available) | 99 | 89 | 94 | 91 | 86 | 93 | 92 |

Baseline last available measurement before implantation, BCVA best corrected visual acuity

Postoperative Adverse Events and Other Observations

Eighteen ocular adverse events were reported (Table 6). Ten of these adverse events were elevated IOP. Elevated IOP resolved in four subjects after treatment with medication, and in six subjects after surgical intervention, including two trabeculectomies and one goniotrephanation. Three reports of stent obstruction resolved without treatment, and three reports (in conjunction with elevated IOP reported above) resolved after laser surgery [neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser in two cases and argon laser in one case]. Following resolution of stent obstruction in one subject, this subject underwent subsequent deep sclerectomy for a subsequent event of elevated IOP. The remaining five adverse events consisted of one subject with progression of pre-existing cataract treated with cataract surgery, one subject with an allergic reaction due to ocular hypotensive medication, a subject with stent malposition, one subject with intraocular inflammation, and a subject with sub-conjunctival hemorrhage. All cases of adverse events resolved without further sequelae. There were 13 cases in which one of the stents was not visible, one case of goniosynechiae (resolved with laser treatment), and one case of lens–iris synechiae (resolved without surgical intervention). No associated complications were reported. Two subjects presented with posterior capsular opacification and associated BCVA loss that resolved after Nd:YAG capsulotomy.

Table 6.

Postoperative ocular adverse events and other postoperative observations

| n (N = 99) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | ||

| Elevated IOP | 10 | 10.1 |

| Treated with medication | 4 | 4.1 |

| Treated with surgerya | 3 | 3.0 |

| With stent obstruction and treated with laser surgeryb | 3 | 3.0 |

| Stent obstruction | 3 | 3.0 |

| Progression of pre-existing cataract treated with cataract surgery | 1 | 1.0 |

| Allergic reaction to ocular hypotensive medication | 1 | 1.0 |

| Stent malposition | 1 | 1.0 |

| Intraocular inflammation | 1 | 1.0 |

| Sub-conjunctival hemorrhage | 1 | 1.0 |

| Other postoperative observations | ||

| Stent not visible upon gonioscopy | 13 | 13.1 |

| Posterior capsular opacification treated with Nd:YAG capsulotomy | 2 | 2.0 |

| Goniosynechiae (resolved without treatment) | 1 | 1.0 |

| Lens–iris synechiae (resolved with laser treatment) | 1 | 1.0 |

Nd:YAG neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet, IOP intraocular pressure

aOne subject underwent trabeculectomy, one subject underwent trabeculectomy and cataract surgery, and one subject underwent goniotrephanation

bTwo subjects underwent Nd:YAG laser surgery and one subject underwent argon laser surgery. Following resolution of stent obstruction, a subsequent event of elevated IOP in one subject was subsequently treated with deep sclerectomy

Discussion

Previous investigations have concluded that MIGS procedures are capable of improving aqueous outflow through the natural physiologic pathway without compromising safety for patients with glaucoma. In the US Food and Drug Administration pivotal trial of the first generation iStent, Samuelson et al. [3] reported a mean IOP reduction of 8.4 mmHg at 12 months following implantation of a single iStent in conjunction with cataract surgery. In a follow-up report by Craven et al. [5], Month 24 mean IOP in the iStent group was 17.1 ± 2.9 mmHg on a mean of 0.3 ± 0.6 medications. Fea et al. [4, 12] and Arriola-Villalobos et al. [10] corroborated the long-term postoperative IOP reduction after implantation of one stent. Confirmation of the outcomes of implantation of a single first generation iStent for the reduction of IOP prompted the investigation of the use of two iStent devices to provide increased facility-of-outflow and to achieve further reductions in IOP. Work by Belovay et al. [17] showed the benefit of multiple implantation of stents in conjunction with cataract surgery to reduce mean IOP to less than 15 mmHg while also reducing medication burden through a period of 12 months postoperative. An initial study demonstrated that subjects with mild-to-moderate OAG who were implanted with two iStent devices as a sole procedure reported an average IOP of 13.6 mmHg at 1 year postoperatively without the need for ocular hypotensive medication [18, 19]. Further, this study confirmed that IOP reduction to <15 mmHg and elimination of medication burden is possible after implantation of two iStent devices, as a stand-alone procedure, without significant postoperative adverse effects. The study concluded MIGS with iStent to be a safe and effective implant procedure that supports earlier intervention in mild-to-moderate OAG [18, 19]. Thus, multiple stent usage has been shown to be viable, both in a theoretical in vitro perfusion model [14, 15] and in clinical experience [18, 19].

The current post-market, prospective, multi-center study evaluated the safety and IOP-lowering efficacy of two GTS-400 iStent inject devices implanted as a sole procedure. The study comprised 99 subjects who underwent implantation of two iStent devices per eye with either the G2-0 injectors or the G2-M-IS injector and were followed for 1 year. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective multi-centered study of iStent inject implantation as the sole procedure in eyes with open-angle glaucoma. The merits of the data include, among other factors, a high rate of subject follow-up through 1 year (93%; n = 92/99).

This study in subjects with OAG on two or more preoperative medications showed mean IOP reduction through 1 year. Most subjects reported IOP ≤ 18 mmHg without the use of concomitant medication. With IOP reduction ≥ 30% in 61% of subjects without medication and in 77% of subjects regardless of medication, it is shown that the Preferred Practice Pattern goal® of 25% IOP reduction from pre-treatment baseline [2] was achieved in the majority of subjects in this study. The medication reduction from preoperative use was noteworthy. Furthermore, the IOP-lowering effect of two iStent inject devices implanted as a sole procedure in this study appears to be greater than that of a single iStent implanted in conjunction with cataract surgery. The iStent US pivotal trial of iStent found that 66% of treatment eyes versus 48% of control eyes achieved ≥20% IOP reduction without medication at Month 12 (P = 0.003) [3]. Results from the current study compare favorably: 72% achieved ≥20% IOP reduction without medication at Month 12, and 93% the Month 12 IOP reduction of 20% or more regardless of medication.

A secondary goal of our study was to evaluate the potential additive effect of conventional outflow and uveoscleral outflow therapy. While 66% of subjects met both the primary endpoint of IOP ≤18 mmHg at 12 months without medication and subsequently the secondary endpoint (i.e., Month 12 IOP ≤ 18 mmHg regardless of medications), an additional 15% (n = 13) of subjects met the secondary endpoint with the use of a single medication, in whom 12 subjects were using prostaglandins. This suggests an additive (synergistic) effect of prostaglandin added to conventional outflow therapy. It should be noted that the second generation iStent inject devices studied in the trial described in this report are implanted using an automated injector system versus the manual inserter system for the first generation device, and may be preferred by some clinicians. Further, this study shows that the iStent inject can lower IOP independent of cataract extraction.

The study demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with a low number of subjects experiencing adverse events. No subjects experienced hypotony, endophthalmitis, or sight-threatening complications frequently associated with more invasive procedures. Other safety measures including BCVA, C:D ratio, and pachymetry were stable throughout the 1-year postoperative period. Limitations of this trial were that it was not masked, did not require a two-person method (with one person masked) to measure IOP, did not have diurnal IOP data available at all sites, did not include visual field measurements, and did not include a control group. There was no standard protocol for restarting glaucoma therapy except at the 6-month time point. These limitations will be addressed in future studies.

Conclusion

This present study demonstrated that implantation of two trabecular micro-bypass stents as the sole procedure in subjects with OAG has a favorable benefit/risk profile as demonstrated by the proportion of subjects who reported IOP reduction and ≤18 mmHg without medication through 12 months. The iStent inject is able to provide a clinically significant reduction in intraocular pressure with a favorable safety profile. Further studies of this promising MIGS technology are planned for evaluation in phakic and pseudophakic OAG patients with earlier glaucoma disease and in concomitant cataract procedures.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Study devices were provided by Glaukos Corporation, Laguna Hills, CA, USA. Sponsorship for performing this study and payment of the article processing charges was provided by Glaukos Corporation. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Jeannie Gifford Cecka, Clinical and Regulatory Consultant, and was funded by Glaukos Corporation. L. Voskanyan is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

L. Voskanyan received financial support from Glaukos for her work as an investigator in this study. J. García-Feijoó received financial support from Glaukos for his work as an investigator in this study. J.I. Belda received financial support from Glaukos for his work as an investigator in this study. A. Fea received financial support from Glaukos for his work as an investigator in this study and has also received non-study financial support from Glaukos. A. Jünemann received financial support from Glaukos for his work as an investigator in this study. C. Baudouin received financial support from Glaukos for his work as an investigator in this study.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The study protocol was approved by ethical committees at each of the study sites. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Footnotes

On behalf of the Synergy Study Group.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov #NCT00911924.

References

- 1.Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya’ale D, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Ophthalmology Glaucoma Panel. Preferred Practice Pattern® guidelines. Primary open-angle glaucoma. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2010. Available at: http://www.aao.org/ppp. Last accessed January 6, 2014.

- 3.Samuelson TW, Katz LJ, Wells JM, Duh Y-J, Giamporcaro JE, for the US iStent Study Group Randomized evaluation of the trabecular micro-bypass stent with phacoemulsification in patients with glaucoma and cataract. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fea AM. Phacoemulsification versus phacoemulsification with micro-bypass stent implantation in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craven ER, Katz LJ, Wells JM, Giamporcaro JE, for the iStent Study Group Cataract surgery with trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation in patients with mild-to-moderate open-angle glaucoma and cataract: Two-year follow-up. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant WM. Experimental aqueous perfusion in enucleated human eyes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;69:783–801. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1963.00960040789022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnstone MA, Grant WG. Pressure-dependent changes in structures of the aqueous outflow system of human and monkey eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75:365–383. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(73)91145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenquist R, Epstein D, Melamed S, et al. Outflow resistance of enucleated human eyes at two different perfusion pressures and different extents of trabeculotomy. Curr Eye Res. 1989;8:1233–1240. doi: 10.3109/02713688909013902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saheb H, Ahmed II. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery: current perspectives and future directions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:96–104. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834ff1e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arriola-Villalobos P, Martinez-de-la-Casa J, Fernandez-Perez J, et al. Combined iStent trabecular micro-bypass stent implantation and phacoemulsification for coexistent open-angle glaucoma and cataract: a long-term study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spiegel D, Wetzel W, Neuhann T, et al. Coexistent primary open-angle glaucoma and cataract: interim analysis of a trabecular micro-bypass stent and concurrent cataract surgery. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:393–399. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fea AM, Pignata, G, Bartoli E, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-masked trial of trabecular bypass stent and cataract surgery vs. cataract surgery alone in primary OAG: long-term data. Presented at the 2012 European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons, Milan, Italy, September, 2012.

- 13.Bahler C, Hann C, Fjield T, et al. Second-generation trabecular meshwork bypass stent (iStent inject) increases outflow facility in cultured human anterior segments. Am J Ophthal. 2012;153:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahler C, Smedley G, Zhou J, Johnson D. Trabecular bypass stents decrease intraocular pressure in cultured human anterior segments. Am J Ophthal. 2004;138:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study. Manual of operations. Chap. 12, 1985.

- 16.Arriola-Villalobos P, Martinez de la Casa JM, Diaz-Valle D, et al. Mid-term evaluation of the new Glaukos iStent with phacoemulsification in coexistent open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension and cataract. Br J Ophthalmol. 2013;97:1250–1255. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-302394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belovay GW, Naqi A, Chan BJ, Rateb M, Ahmed II. Using multiple trabecular micro-bypass stents in cataract patients to treat open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38:1911–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz LJ, on behalf of the MIGS Study Group. IOP and medication reduction after micro invasive glaucoma surgery with two trabecular micro-bypass stents in OAG. Presented at 2013 American Glaucoma Society Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, February, 2013.

- 19.Chang LJ, on behalf of the MIGS Study Group. Intraocular pressure reduction and safety outcomes after microinvasive glaucoma surgery with 2 trabecular bypass stents in OAG. Presented at 2013 American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgeons Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, April, 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.