Abstract

Introduction

While the liraglutide effect and action in diabetes (LEAD-6) clinical trial compared the efficacy and safety of liraglutide once daily (LIRA) to exenatide twice daily (EXEN) in adult patients with type 2 diabetes, few studies have explored the associated per-patient costs of glycemic goal achievement of their use in a real-world clinical setting.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used integrated medical and pharmacy claims linked with glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) results from the IMS Patient-Centric Integrated Data Warehouse. Patients’ ≥18 years and naïve to incretin therapies during a 6-month pre-index period, with ≥1 prescription for LIRA or EXEN between January 2010 and December 2010, were included. Patients with evidence of insulin use (pre- or post-index) were excluded. Only patients who were persistent on their index treatment during a 180-day post-index period were included. Follow-up A1C assessments were based on available laboratory data within 45 days before or after the 6-month post-index point in time. Diabetes-related pharmacy costs over the 6-month post-index period were captured and included costs for both the index drugs and concomitant diabetes medications.

Results

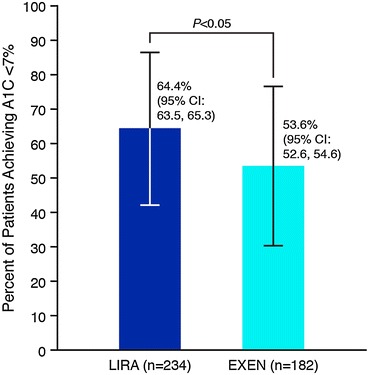

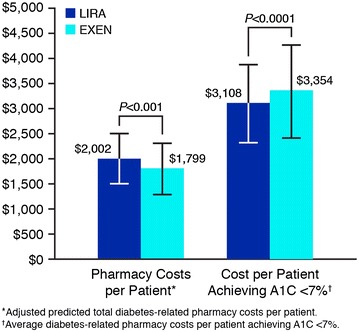

234 LIRA and 182 EXEN patients were identified for the analysis. The adjusted predicted diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient over the 6-month post-index period were higher for LIRA compared to EXEN ($2,002 [95% confidence interval (CI): $1,981, $2,023] vs. $1,799 [95% CI: $1,778, $1,820]; P < 0.001). However, a higher adjusted predicted percentage of patients on LIRA reached A1C < 7% goal (64.4% [95% CI: 63.5, 65.3] vs. 53.6% [95% CI: 52.6, 54.6]; P < 0.05), translating into lower average diabetes-related pharmacy costs per successfully treated patient for LIRA as compared to EXEN ($3,108 vs. $3,354; P < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Although predicted diabetes-related pharmacy costs were greater with LIRA vs. EXEN, a higher proportion of patients on LIRA achieved A1C < 7%, resulting in a lower per-patient cost of A1C goal achievement with LIRA compared to EXEN.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-014-0098-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cost-effectiveness, Endocrinology, Exenatide, Glycated hemoglobin A1C goal attainment, Glycemic control, Liraglutide, Type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Current estimates of health care costs and recent increases in health care costs attributable to the management of diabetes and its complications in the United States (US) are staggering and continue to increase. Total estimated costs of diagnosed diabetes have increased 41%, to $245 billion in 2012 from $174 billion in 2007 [1]. Most of the costs are attributable to the care of individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and treating the complications of T2DM, while only 12% of total health care costs relate to antidiabetic medications and supplies.

To reduce the costs of diabetes, preventing the development of diabetes complications through glycemic control is imperative [1, 2]. Consequently, glycemic control is an essential component of the effective management of T2DM [3] and its associated health care costs [2].

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends a glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) goal of <7.0% in most patients to reduce the incidence of microvascular complications [3]. Recent guidelines have highlighted the need to individualize treatment goals based on comorbidities, duration of diabetes, life expectancy, presence and severity of complications, and history of hypoglycemia.

Metformin—either alone or in combination with another glucose-lowering agent—is the first-line antidiabetic therapy for patients with T2DM [2, 3]. Several treatment options are recommended for patients who do not achieve their glycemic targets on metformin alone, including the most recent incretin-based therapies: dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. Currently available GLP-1 receptor agonists include exenatide (EXEN) twice daily, EXEN once weekly, and liraglutide (LIRA) once daily.

The efficacy of LIRA as monotherapy, in combination with other agents, and in comparison to other incretin therapies is well documented by randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews [4–11]. The LEAD-6 (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes) clinical trial (NCT00518882) compared the efficacy and safety of LIRA once daily to EXEN twice daily in adult patients with T2DM inadequately controlled on metformin, a sulfonylurea, or both [9]. LIRA provided significantly greater reductions in A1C and higher rates of A1C goal achievement compared to EXEN. A second study reported greater A1C reductions, higher rates of A1C goal achievement, and greater weight loss with LIRA once daily vs. EXEN once weekly [10].

An understanding of the true costs of helping patients achieve A1C goals, particularly based on real-world data, may facilitate clinical decision making in candidates for LIRA or EXEN. The objective of this study is to evaluate real-world costs of successful A1C < 7% goal attainment with LIRA and EXEN in clinical practice, to provide health care providers and payers in the USA with transparent cost-effectiveness data to help inform decisions regarding treatment as well as coverage.

Methods

Data Source

Data were accessed through the IMS Patient-Centric Data Warehouse, an extensive US database with linked laboratory, pharmacy and medical claims. The database contains de-identified longitudinal data, as well as clinical and demographic information (e.g., sex, age, comorbidities, insurance plan type), inpatient and outpatient claims (e.g., service charges, admission and discharge dates, procedure and diagnosis codes), laboratory tests and results, and pharmacy claims data (de-identified prescribing physician, drug dispensed based on national drug codes (NDCs), quantity and date dispensed, drug strength, days’ supply, prescription cost). The warehouse is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. The patients for this study were selected by linking the medical and pharmacy elements of the database to the laboratory data asset to augment the number of patients with A1C laboratory values, one of two key outcome variables associated with the study’s objective.

Patient Selection

This was a retrospective cohort study, with all patients having at least one claim for LIRA or EXEN identified between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010. The date of the first drug identified during this time was considered the index date and the drug was designated as the index drug. To be included in the cohort, all patients had to be at least 18 years of age on the index date, be GLP-1 and DPP-4-naïve during a 6-month pre-index period, and have at least one claim for a physician visit within the 12-month study period (6-month pre-index and 6-month post-index). Only patients who were considered persistent to the index medication during the 6-month post-index period were included in the analysis to avoid introducing bias based on historic medication use. Persistent patients included those who remained on their index drug (LIRA or EXEN) until discontinuation, medication switch, or augmentation to another index medication. Patients with evidence of gestational diabetes and/or pregnancy, Type 1 diabetes, or dopamine receptor agonists in the pre-index period or the use of insulin at any point during the study period were excluded from the analysis. Please see Table 1 for details on patients’ concomitant medications.

Table 1.

Physician specialty, use of concomitant glucose-lowering agents, comorbidities, and pre-index healthcare costs

| LIRA (n = 234) | EXEN (n = 182) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prescriber physician specialty (n, %) | 0.77 | ||

| General practice/family practice | 67 (28.6%) | 50 (27.5%) | |

| Internal medicine | 73 (31.2%) | 63 (34.6%) | |

| Endocrinology | 61 (26.1%) | 38 (20.9%) | |

| Cardiology | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (1.1%) | |

| Other | 26 (11.1%) | 24 (13.2%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (1.7%) | 5 (2.7%) | |

| Concomitant oral antidiabetic medication use in the pre-index period (n, %) | |||

| Any oral antidiabetic medication | 196 (83.8%) | 161 (88.5%) | 0.17 |

| Sulfonylureas (SUs) | 84 (35.9%) | 60 (33.0%) | 0.53 |

| Biguanides | 132 (56.4%) | 105 (57.7%) | 0.79 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.19 |

| Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) | 48 (20.5%) | 40 (22.0%) | 0.72 |

| Other oral antidiabetic medication | 5 (2.1%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.19 |

| No drug use | 38 (16.2%) | 21 (11.5%) | 0.17 |

| Concomitant oral antidiabetic medication use in the post-index period (n, %) | |||

| Any oral antidiabetic medication | 189 (80.8%) | 159 (87.4%) | 0.07 |

| Sulfonylureas (SUs) | 63 (26.9%) | 60 (33.0%) | 0.18 |

| Biguanides | 142 (60.7%) | 127 (69.8%) | 0.05 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.44 |

| Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) | 31 (13.2%) | 37 (20.3%) | 0.05 |

| Other oral antidiabetic medication | 3 (1.3%) | 5 (2.7%) | 0.31 |

| No drug use | 45 (19.2%) | 23 (12.6%) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes-related macrovascular complications in the pre-index period (n, %) | |||

| Any diabetes-related macrovascular complication | 25 (10.7%) | 16 (8.8%) | 0.52 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 (2.6%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.47 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 18 (7.7%) | 10 (5.5%) | 0.37 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.44 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (2.1%) | 6 (3.3%) | 0.46 |

| Diabetes-related microvascular complications in the pre-index period (n, %) | |||

| Any diabetes-related microvascular complication | 33 (14.1%) | 22 (12.1%) | 0.55 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11 (4.7%) | 6 (3.3%) | 0.47 |

| Diabetic neuropathy | 17 (7.3%) | 14 (7.7%) | 0.87 |

| Diabetic retinopathy | 5 (2.1%) | 4 (2.2%) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes-related comorbidities in the pre-index period (n, %) | |||

| Any diabetes-related comorbidity | 161 (68.8%) | 120 (65.9%) | 0.54 |

| Amputation/ulceration | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0.08 |

| Depression | 12 (5.1%) | 12 (6.6%) | 0.52 |

| Diabetes with hypoglycemia | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.2%) | 0.04 |

| Dyslipidemia | 124 (53.0%) | 93 (51.1%) | 0.70 |

| Heart failure | 7 (3.0%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0.52 |

| Hypertension | 120 (51.3%) | 88 (48.4%) | 0.55 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (1.6%) | 1.00 |

| Obesity | 26 (11.1%) | 21 (11.5%) | 0.89 |

| Other renal disease | 4 (1.7%) | 6 (3.3%) | 0.34 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) Score (n, %) | |||

| 0 | 51 (21.8%) | 40 (22.0%) | 0.96 |

| 1–2 | 167 (71.4%) | 128 (70.3%) | |

| 3–4 | 14 (6.0%) | 13 (7.1%) | |

| 5+ | 2 (0.9%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Mean | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.92 |

| SD | 0.9 | 0.9 | |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Pre-index healthcare costs | |||

| Mean | $3,844 | $3,634 | 0.59 |

| SD | $4,311 | $3,662 | |

| Median | $2,683 | $2,436 | |

| Pre-index total outpatient pharmacy costs | |||

| Mean | $704 | $567 | 0.02 |

| SD | $782 | $435 | |

| Median | $524 | $455 | |

EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide

The A1C change from baseline and glycemic goal attainment of A1C < 7% over the 6-month post-index period for each cohort relied on available laboratory data. For the follow-up A1C measurement at the 6-month post-index point in time, the laboratory value was identified during the time period ±45 days to the 6-month post-index point in time, utilizing the mean of the laboratory values available during that time interval if several measures were present. The costs that were captured included both index drug (LIRA or EXEN) pharmacy costs and the costs of other diabetes-related pharmacy costs for concomitant medications.

Statistical Analysis

All patient demographic and clinical characteristics as well as diabetes-related pharmacy costs were descriptively reported. For continuous variables, findings were presented as the mean, standard deviation (SD), and median. For categorical measures, data included the frequency [number of cases (N)] and percentage (%) of patients observed in each category. P values using the Student’s t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the Pearson Chi square test for categorical variables were produced. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

For the outcome measures of glycemic goal attainment of A1C < 7% and total diabetes-related pharmacy costs, multivariate analyses were performed to account for baseline and post-index differences between the two treatments of interest. The likelihood of reaching A1C goal of <7% was estimated using a logistic regression model. A generalized linear model (GLM) was developed (controlling for the same independent variables as in the logistic regression model) to estimate the total diabetes-related pharmacy costs over the 6-month post-index period. Covariates in the models included gender, plan type, pre- and post-index concomitant medications, history of diabetes-related comorbidities, and patient copayment, among other explanatory variables.

Predicted values for both diabetes-related pharmacy cost per patient and A1C < 7% goal attainment over 6-month follow-up were estimated from the multivariate regression models based on the method of recycled predictions, along with constructing 95% confidence intervals from the bootstrap distribution. This method entails comparisons of two predictive margins where a particular attribute (in this case the index treatment) is assumed present or absent.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® (version 9.2, Cary, NC, USA).

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

There were few significant differences when comparing the clinical characteristics between LIRA and EXEN patients (Table 2). Mean A1C at baseline was 7.8% in both groups. A greater proportion of LIRA patients resided in the south compared to EXEN (67.5% vs. 52.7%; P < 0.01). In addition, a significantly greater proportion of LIRA patients had a third party health plan type compared to EXEN (94.4% vs. 73.6%; P < 0.0001) and more EXEN patients had claims for hypoglycemia in the pre-index period compared to LIRA patients (2.2% vs. 0.0%; P = 0.04). The total average outpatient pharmacy costs in the pre-index period were higher for patients initiating LIRA compared to EXEN ($704 vs. $567; P = 0.02) (Table 1).

Table 2.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| LIRA (n = 234) | EXEN (n = 182) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| Mean | 54.3 | 54.6 | 0.73 |

| SD | 9.6 | 10.6 | |

| Median | 54 | 55 | |

| Age group, n (%) | 0.11 | ||

| 18–34 years | 5 (2.1%) | 9 (4.9%) | |

| 35–44 years | 34 (14.5%) | 25 (13.7%) | |

| 45–54 years | 79 (33.8%) | 50 (27.5%) | |

| 55–64 years | 87 (37.2%) | 62 (34.1%) | |

| 65+ years | 29 (12.4%) | 36 (19.8%) | |

| Female (%) | 129 (55.1%) | 106 (58.2%) | 0.53 |

| Mean A1C at baseline, % (SD) | 7.8 (1.5) | 7.8 (1.4) | 0.89 |

| Geographic region, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Northeast | 30 (12.8%) | 25 (13.7%) | |

| Midwest | 18 (7.7%) | 17 (9.3%) | |

| South | 158 (67.5%) | 965 (52.7%) | |

| West | 28 (12.0%) | 44 (24.2%) | |

| Health plan type, n (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Cash | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Medicaid | 5 (2.1%) | 14 (7.7%) | |

| Medicare | 8 (3.4%) | 34 (18.7%) | |

| Third party | 221 (94.4%) | 134 (73.6%) | |

A1C glycated hemoglobin A1C, EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide, SD standard deviation

Descriptive A1C and Cost Outcomes: Unadjusted Results

Prior to adjusting for confounding factors, a significantly greater proportion of LIRA patients achieved an A1C value of <7% as compared to EXEN patients (64.5% vs. 54.4%; P = 0.04) (Table 3). The difference in A1C from baseline to 6 months post-index was also significantly greater for LIRA patients compared to EXEN patients (−0.99% vs. −0.68%; P = 0.02). Over the 6-month post-index period, descriptive unadjusted total diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient were similar between the two groups ($1,993 vs. $1,924; P = 0.376) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Unadjusted descriptive glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) outcomes at 6-month follow-up

| LIRA (n = 234) | EXEN (n = 182) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months Post-index (n, %) | |||

| % of patients achieving A1C value of <7.0% | 151 (64.5%) | 99 (54.4%) | 0.04 |

| Unadjusted difference between baseline and 6 months Post-index (%-point) | |||

| Mean | 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.02 |

| SD | 1.40 | 1.34 | |

| Median | 0.60 | 0.40 | |

A1C glycated hemoglobin A1C, EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide, SD standard deviation

Table 4.

Unadjusted descriptive pharmacy costs at 6-month follow-up

| LIRA (n = 234) | EXEN (n = 182) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total diabetes-related pharmacy costs in 6 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | $1,993 ($810) | $1,924 ($740) | 0.376 |

| Median | $1,873 | $1,788 | |

| Total index drug pharmacy costs in 6 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | $1,641 ($584) | $1,423 ($372) | <0.0001 |

| Median | $1,615 | $1,432 | |

| Total other diabetes-related pharmacy costs in 6 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | $351 ($52) | $501 ($596) | 0.007 |

| Median | $98 | $259 | |

EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide, SD standard deviation

Adjusted A1C and Cost Outcomes: Multivariable Models

The factors associated with achieving A1C < 7% were estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model (Table 5). EXEN patients were 43.5% less likely to reach A1C < 7% compared to LIRA patients (OR = 0.565; P = 0.015). Plan type as well as certain pre- and post-index concomitant medications had a significant impact on the likelihood of reaching A1C < 7%.

Table 5.

Factors associated with reaching glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) < 7% over 6-month post-index period: logistic regression

| Independent variables | 95% Confidence limits | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | Lower limit | Upper limit | P value | |

| EXEN vs. LIRA | 0.565 | 0.357 | 0.894 | 0.015 |

| Age (years) | 0.999 | 0.989 | 1.009 | 0.874 |

| Gender (male/female) | 0.957 | 0.785 | 1.167 | 0.666 |

| Cash vs. third party | 1.440 | 0.393 | 5.283 | 0.582 |

| Medicaid vs. third party | 0.591 | 0.381 | 0.917 | 0.019 |

| Medicare vs. third party | 1.282 | 0.987 | 1.667 | 0.063 |

| Baseline A1C % | 0.512 | 0.469 | 0.558 | <.0001 |

| Prior use of SUs (yes/no) | 0.486 | 0.367 | 0.643 | <.0001 |

| Prior use of biguanides (yes/no) | 0.936 | 0.735 | 1.193 | 0.595 |

| Prior use of TZDs (yes/no) | 0.463 | 0.348 | 0.617 | <.0001 |

| Prior use of other oral antidiabetic medication (yes/no)a | 0.346 | 0.144 | 0.832 | 0.018 |

| History of myocardial infarction (yes/no) | 0.773 | 0.283 | 2.112 | 0.616 |

| History of ischemic heart disease (yes/no) | 1.227 | 0.885 | 1.701 | 0.220 |

| History of congestive heart failure (yes/no) | 1.020 | 0.568 | 1.831 | 0.947 |

| History of peripheral vascular disease (yes/no) | 0.913 | 0.545 | 1.527 | 0.728 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease (yes/no) | 1.333 | 0.780 | 2.281 | 0.293 |

| History of diabetic retinopathy (yes/no) | 1.038 | 0.631 | 1.708 | 0.884 |

| History of macular edema (yes/no) | 0.641 | 0.198 | 2.076 | 0.459 |

| History of diabetic neuropathy (yes/no) | 1.008 | 0.688 | 1.476 | 0.969 |

| History of amputation and ulceration (yes/no) | 0.678 | 0.175 | 2.628 | 0.574 |

| History of renal disease (yes/no) | 0.700 | 0.429 | 1.141 | 0.153 |

| History of hypertension (yes/no) | 1.075 | 0.862 | 1.342 | 0.519 |

| History of dyslipidemia (yes/no) | 1.026 | 0.824 | 1.278 | 0.819 |

| History of depression (yes/no) | 0.693 | 0.417 | 1.151 | 0.157 |

| History of obesity (yes/no) | 1.213 | 0.808 | 1.821 | 0.352 |

| History of hypoglycemia (yes/no) | 0.598 | 0.204 | 1.752 | 0.349 |

| Post use of SUs (yes/no) | 0.705 | 0.536 | 0.927 | 0.012 |

| Post use of biguanides (yes/no) | 1.240 | 0.951 | 1.616 | 0.112 |

| Post use of TZDs (yes/no) | 1.972 | 1.436 | 2.708 | <.0001 |

| Post use of other oral antidiabetic medication (yes/no)a | 2.754 | 0.989 | 7.670 | 0.053 |

| Post use of metformin combo (yes/no) | 1.388 | 1.042 | 1.848 | 0.025 |

| Index out of pocket per 30 days’ supply (in $10) | 0.991 | 0.965 | 1.018 | 0.521 |

A1C glycated hemoglobin A1C, EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide, SD standard deviation, SU sulfonylureas, TZDS thiazolidinediones

aIncludes alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and antidiabetic amylin analog

The factors associated with total diabetes-related pharmacy costs over the 6-month post-index period were identified via a GLM model. After controlling for covariates such as age, gender, baseline A1C level, comorbidity history and concomitant medication use, diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient were lower for EXEN patients compared to LIRA patients (parameter estimate = −$203.1; P = 0.0002) (Table 6). As for the logistic regression model, plan type as well as certain pre- and post-index concomitant medications had a significant impact on the estimated total diabetes-related pharmacy costs in this GLM model.

Table 6.

Factors associated with total diabetes-related pharmacy costs over 6-month post-index period: generalized linear model

| Independent variables | Wald 95% confidence limits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter estimate | Standard error | Lower limit | Upper limit | P value | |

| EXEN vs. Lira | −203.2 | 53.7 | −308.5 | −97.8 | 0.0002 |

| Age (years) | −0.4 | 1.2 | −2.8 | 1.9 | 0.709 |

| Gender (male/female) | 38.8 | 24.0 | −8.2 | 85.9 | 0.106 |

| Health plan type | |||||

| Cash vs. third party | 71.0 | 146.4 | −215.8 | 357.9 | 0.627 |

| Medicaid vs. third party | 146.4 | 50.0 | 48.3 | 244.5 | 0.003 |

| Medicare vs. third party | 69.1 | 31.5 | 7.3 | 130.9 | 0.029 |

| Baseline A1C % | −2.1 | 8.4 | −18.6 | 14.5 | 0.806 |

| Prior use of oral antidiabetic agents (yes/no) | |||||

| Sulfonylureas | 29.1 | 34.4 | −38.3 | 96.4 | 0.398 |

| Biguanides | 26.0 | 28.9 | −30.7 | 82.8 | 0.368 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 138.2 | 34.7 | 70.2 | 206.1 | <0.0001 |

| Other oral antidiabetic medicationa | 281.2 | 97.7 | 89.7 | 472.7 | 0.004 |

| Medical history (yes/no) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 182.4 | 114.9 | −42.8 | 407.6 | 0.112 |

| Ischemic heart disease | −6.9 | 39.7 | −84.8 | 70.9 | 0.861 |

| Heart failure | 7.7 | 69.6 | −128.7 | 144.1 | 0.911 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | −16.3 | 62.6 | −139.1 | 106.5 | 0.794 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 33.9 | 65.2 | −93.9 | 161.7 | 0.603 |

| Diabetic retinopathy | −110.1 | 60.9 | −229.5 | 9.3 | 0.071 |

| Macular edema | 320.8 | 146.7 | 33.2 | 608.3 | 0.029 |

| Diabetic neuropathy | 3.8 | 45.6 | −85.6 | 93.2 | 0.934 |

| Amputation and ulceration | 114.5 | 156.3 | −191.9 | 420.9 | 0.464 |

| Renal disease | 105.4 | 58.4 | −9.1 | 219.8 | 0.071 |

| Hypertension | 3.3 | 26.8 | −49.2 | 55.7 | 0.903 |

| Dyslipidemia | −21.2 | 26.6 | −73.3 | 30.9 | 0.425 |

| Depression | −42.4 | 60.4 | −160.8 | 76.0 | 0.482 |

| Obesity | 46.2 | 48.6 | −49.0 | 141.4 | 0.342 |

| Hypoglycemia | −206.2 | 129.0 | −459.0 | 46.5 | 0.110 |

| Post use of oral antidiabetic agents (yes/no) | |||||

| Sulfonylureas | 101.6 | 33.8 | 35.3 | 167.9 | 0.003 |

| Biguanides | 213.5 | 31.7 | 151.5 | 275.6 | <0.0001 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 1025.3 | 37.7 | 951.4 | 1099.2 | <0.0001 |

| Other oral antidiabetic medicationa | 828.0 | 114.5 | 603.5 | 1052.4 | <0.0001 |

| Metformin combination | −154.2 | 34.7 | −222.2 | −86.2 | <0.0001 |

A1C glycated hemoglobin A1C, EXEN exenatide, LIRA liraglutide

aIncludes alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and antidiabetic amylin analog

Cost per Patient to Achieve A1C < 7%

The cost per patient to achieve A1C < 7% portrays a simplistic and transparent way of assessing the short-term cost-effectiveness of the treatment alternatives. The adjusted predicted diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient were higher for LIRA compared to EXEN (all values are mean ± standard deviation) ($2,002 ± $502 vs. $1,799 ± $502, P < 0.001); however, significantly more LIRA patients reached A1C < 7% as compared to EXEN (64.4% ± 22.4% vs. 53.6% ± 23.1%; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). In terms of cost per patient successfully achieving A1C < 7%, this translates into a lower cost of control for LIRA compared to EXEN ($3,108 ± $779 vs. $3,354 ± $936; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) < 7% goal attainment at 6-month follow-up. CI confidence interval, LIRA liraglutide, EXEN exenatide

Fig. 2.

Cost per successfully treated patient to glycated hemoglobin A1C (A1C) < 7% at 6-month follow-up

Discussion

This study is among the first to evaluate the real-world cost-effectiveness of treating patients to A1C < 7% with LIRA once daily and EXEN twice daily using a real-world administrative claims dataset. In this analysis, the adjusted predicted diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient were higher with LIRA than with EXEN ($2,002 vs. $1,799, P < 0.001). However, as a greater proportion of patients on LIRA reached A1C < 7% compared to patients on EXEN (64.4% vs. 53.6%, P < 0.05), total diabetes-related pharmacy costs per successfully treated patient were lower with LIRA than with EXEN ($3,108 vs. $3,354; P < 0.0001). In fact, the A1C reductions observed in this study are consistent with the findings reported in LEAD-6 [9].

Still, this retrospective study differs from clinical trials in that randomized clinical trials contain strict inclusion and exclusion criteria and pre-defined concomitant antidiabetic medication use. For example, this study included patients with baseline A1C < 7.0%, patients who would have been excluded from clinical trials of LIRA. Consequently, the mean A1C in this study was slightly lower (7.8%) than in LEAD-6 (8.2% with LIRA and 8.1% with EXEN). This difference likely explains, at least in part, the difference in the proportion of patients achieving A1C < 7.0% between this study and those reported in LEAD-6 [9]. In this study, 65% of patients on LIRA and 54% on EXEN achieved A1C < 7.0% (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). In LEAD-6, 54% on LIRA and 43% on EXEN achieved A1C < 7.0% (P = 0.0015).

A1C reductions were higher in DURATION-6, a randomized clinical trial (NCT01029886) that compared EXEN once weekly with LIRA once daily [10]. In this 26-week trial, A1C reductions were −1.48% with LIRA and −1.28% with EXEN once weekly (P = 0.02) with 60% and 53% achieving A1C < 7% with LIRA and EXEN once weekly, respectively (P = 0.0011). However, direct comparisons should be warranted due to the higher baseline A1C values in DURATION-6 (8.4% and 8.5% for LIRA and EXEN once weekly, respectively) compared to those in our study (7.8% for both LIRA and EXEN). Furthermore, the patients who were randomized to LIRA in DURATION-6 had a forced titration to LIRA 1.8 mg, whereas the drug dose was not ascertained for this analysis.

While the clinical superiority of LIRA compared to EXEN has been well documented in a clinical trial setting, our findings contextualize the relative efficacy of these agents with the per-patient costs associated with A1C goal achievement in clinical practice. Real-world evidence has become increasingly important as a decision-making tool for policymakers and health care providers as they struggle to control increasing health care costs and use cost-effective treatment options.

In the US, there is a shift towards more accountable patient care through the creation of voluntary accountable care organizations (ACOs) under the Affordable Care Act of 2010. These ACOs extend financial incentives to providers, including an advanced payment model, if they can reduce Medicare cost growth in particular service areas [12, 13]. Presumably, a metric such as cost per patient to A1C goal in diabetes care could be considered when evaluating provider performance under an ACO, making the findings of our study particularly relevant.

Studies that have examined the cost implications of improving glucose management have reported that the glycemic control costs are modest compared to total diabetes-related health expenditures [1, 14].

Other studies have evaluated the comparative costs and cost-effectiveness of glucose-lowering agents in T2DM, including the use of incretin therapies, both in the USA [15, 16] and in Europe [17, 18]. In the US retrospective cohort study by Pelletier and colleagues, patients receiving exenatide twice daily and liraglutide once daily had similar total 6-month follow-up (inpatient and outpatient) costs ($6,688 vs. $7,346) [15]. However, patients receiving exenatide had significantly lower mean pharmacy costs ($2,925 vs. $3,272, P < 0.001). Importantly, the study did not evaluate or relate these findings to outcomes in A1C or other indicators of glycemic control, such as microvascular complications or other outcomes associated with reductions in A1C.

In a retrospective chart audit of patients in the United Kingdom who received LIRA, EXEN, or a DPP-4 inhibitor (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, or vildagliptin), for a median of 48 weeks, significantly greater reductions in A1C (all P < 0.05) were seen with LIRA (−1.22%) than both EXEN (−0.71%), and the DPP-4 inhibitors (–0.66%) [17]. Estimated life-years gained per patient were 0.12 with LIRA, 0.08 with EXEN, and 0.07 with DPP-4 inhibitors, yielding a cost per quality-adjusted life year of £16,505, £16,648, and £20,661, respectively [17].

One recent report evaluated the short-term cost-effectiveness of LIRA vs. sitagliptin based on data from a randomized controlled trial of patients who failed to achieve A1C goals on metformin therapy [19, 20]. The simplistic and transparent short-term cost-effectiveness methodology applied in our real-world study of the cost of control follows the approach taken by Langer and colleagues in relating cost to treatment success [19].

Limitations

These results must be viewed with the typical limitations associated with studies based on administrative claims data. The correspondence between pharmacy submission of claims and patients’ receipt and consumption of the medication was assumed and not directly measured. However, prior work suggests that medication exposure can be accurately derived from pharmacy claims [21, 22]. The study also assumed that all information needed for cohort stratification was present and similar across the cohorts of interest.

Of note, this study excluded any patients that had evidence of insulin use in either the pre- or post-index periods and cohorts were limited to consist of patients being persistent on their index therapy for a 6-month post-index period. Insulin users were excluded to remove any of the potentially additive or synergistic glucose-lowering effects of such a combination regimen, thereby focusing exclusively on the ability of LIRA and EXEN to improve glycemic control.

Although the treatment effects of LIRA 1.2 mg vs. LIRA 1.8 mg were ascertained in clinical trials, delineating LIRA 1.2 mg from LIRA 1.8 mg is a challenge in a claims database study. Exclusively relying on the NDC codes or derived dosing calculations would not completely capture patient practice realities (i.e., dosing, titration), and assigning those who titrated at some point in the 6-month follow-up period made it difficult to assign them to one category or another, though it did reflect actual clinical practice. Additionally, we did not differentiate or stratify EXEN 5 or 10 μg and patients on either dose were included in our analysis.

Despite these limitations, this study has provided valuable information regarding the real-world cost-effectiveness of LIRA compared to EXEN in the US.

Conclusion

Because this study paired A1C outcomes in clinical practice with an examination of real-world costs, it offers a useful point of reference for future assessments of the true health care costs of helping patients with T2DM achieve their glycemic goals.

In this analysis, adjusted predicted diabetes-related pharmacy costs per patient were higher with LIRA than with EXEN over 6-month follow-up. However, because a significantly greater proportion of patients on LIRA achieved A1C goal <7% compared with patients on EXEN, diabetes-related pharmacy costs per successfully treated patient were ultimately lower with LIRA than with EXEN. These findings can assist clinicians and formulary staff in choosing the most cost-effective GLP-1 and incretin formulations in an effort to reduce health care costs and improve patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nicole Cooper of MedVal Scientific Information Services, LLC, for providing professional writing and editorial assistance. Funding to support the preparation of this manuscript was provided to MedVal by Novo Nordisk Inc. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ “Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: the GPP2 Guidelines” and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors’ “Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals”. Sponsorship and article processing charges for this study were funded by Novo Nordisk Inc. (NJ, USA).

Conflict of interest

Jon Bouchard is an employee and shareholder of Novo Nordisk with no further declarations of interest. Marjan Massoudi is an employee and shareholder of Novo Nordisk with no further declarations of interest. Jakob Langer is an employee and shareholder of Novo Nordisk with no further declarations of interest. Mitch DeKoven is an employee of IMS Health with no further declarations of interest. Won Chan Lee is an employee of IMS Health with no further declarations of interest. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodbard HW, Jellinger PS, Davidson JA, et al. Statement by an American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology consensus panel on type 2 diabetes mellitus: an algorithm for glycemic control. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:540–559. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shyangdan DS, Royle P, Clar C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide analogues for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD006423. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006423.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:84–90. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373:473–481. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nisal K, Kela R, Khunti K, Davies MJ. Comparison of efficacy between incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Med. 2012;10:152. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T, et al. Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26-week, randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6) Lancet. 2009;374:39–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6): a randomised, open-label study. Lancet. 2013;381:117–124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fakhoury WKH, Lereun C, Wright D. A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials assessing the efficacy and safety of incretin-based medications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Pharmacology. 2010;86:44–57. doi: 10.1159/000314690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Innovation models. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/index.html#views=models. Accessed October 9, 2012.

- 13.Goldsmith J. Accountable care organizations: the case for flexible partnerships between health plans and providers. Health Aff. 2011;30:32–40. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stolar MW, Hoogwerf BJ, Boyle PJ, Gorshow SM, Wales DO. Managing type 2 diabetes: going beyond glycemic control. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14:S2–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelletier EM, Pawaskar M, Smith PJ, Best JH, Chapman RH. Economic outcomes of exenatide versus liraglutide in type 2 diabetes patients in the United States: results from a retrospective claims database analysis. J Med Econ. 2012;15:1039–1050. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.688903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WC, Conner C, Hammer M. Results of a model analysis of the cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus exenatide added to metformin, glimepiride, or both for the treatment of type 2 diabetes in the United States. Clin Ther. 2010;32:1756–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans M, McEwan P, O’Shea R, George L. A retrospective, case-note survey of type 2 diabetes patients prescribed incretin-based therapies in clinical practice. Diabetes Therapy. 2013;4:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s13300-012-0015-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentine WJ, Palmer AJ, Lammert M, Langer J, Brandle M. Evaluating the long-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus exenatide BID in patients with type 2 diabetes who fail to improve with oral antidiabetic agents. Clin Ther. 2011;33:1698–1712. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langer J, Hunt B, Valentine WJ. Evaluating the short-term cost-effectiveness of liraglutide versus sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes failing metformin monotherapy in the United States. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19:237–246. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pratley R, Nauck M, Bailey T, et al. One year of liraglutide treatment offers sustained and more effective glycaemic control and weight reduction compared with sitagliptin, both in combination with metformin, in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:397–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DW, Anda RF, Felitti VJ. Self-reported information and pharmacy claims were comparable for lipid-lowering medication exposure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson K, Kenny RA, Peklar J, Bennett K. Agreement between patient interview data on prescription medication use and pharmacy records in those aged older than 50 years varied by therapeutic group and reporting of indicated health conditions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.