Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the association between maximum daily atrial fibrillation (AF) burden and risk of ischaemic stroke.

Background

Cardiac implanted electronic devices (CIEDs) enhance detection of AF, providing a comprehensive measure of AF burden.

Design, setting, and patients

A pooled analysis of individual patient data from five prospective studies was performed. Patients without permanent AF, previously implanted with CIEDs, were included if they had at least 3 months of follow-up. A total of 10 016 patients (median age 70 years) met these criteria. The risk of ischaemic stroke associated with pre-specified cut-off points of AF burden (5 min, 1, 6, 12, and 23 h, respectively) was assessed.

Results

During a median follow-up of 24 months, 43% of 10 016 patients experienced at least 1 day with at least 5 min of AF burden and for them the median time to the maximum AF burden was 6 months (inter-quartile range: 1.3–14). A Cox regression analysis adjusted for the CHADS2 score and anticoagulants at baseline demonstrated that AF burden was an independent predictor of ischaemic stroke. Among the thresholds of AF burden that we evaluated, 1 h was associated with the highest hazard ratio (HR) for ischaemic stroke, i.e. 2.11 (95% CI: 1.22–3.64, P = 0.008).

Conclusions

Device-detected AF burden is associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke in a relatively unselected population of CIEDs patients. This finding may add to the basis for timely and clinically appropriate decision-making on anticoagulation treatment.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Anticoagulation, Implantable defibrillator, Pacemaker, Stroke

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF)-associated ischaemic stroke can be devastating and a major contributor to healthcare spending. Fortunately, it is largely preventable by anticoagulant therapy. Current guidelines recommend risk-based use of anticoagulant therapy in patients with AF. Such guidelines apply to patients with paroxysmal as well as persistent AF.1 However, among patients with paroxysmal AF, the frequency and length of episodes of AF are highly variable. Further, many episodes of AF are clinically ‘silent’, being detected incidentally through routine physical examinations, pre-operative assessments, diagnostic logs of implanted devices, or population surveys.2 Current guidelines do not specifically address anticoagulation use in cases of ‘silent’ AF. Indeed, in some cases, asymptomatic AF is revealed only after complications such as ischaemic stroke or congestive heart failure have occurred.3

The relationship between the duration and frequency of AF and stroke risk is uncertain and an area of active investigation. Moreover, the definition of a clinically useful measure that accurately reflects an individual risk from an intermittent and progressive disease is a challenge.4–10 Modern implanted devices such as defibrillators, pacemakers, or implantable loop recorders now allow precise, continuous long-term monitoring of heart rhythms, such as AF.2 Implanted devices with an atrial lead can measure the total time spent in AF each day, i.e. the daily atrial tachycardia/AF burden or ‘daily AF burden’.

We pooled data from three studies of patients with a broad spectrum of such devices to assess the association between the maximum daily AF burden and the risk of ischaemic stroke in order to provide a large patient population to be evaluated for this scope.

Methods

Patient population and study design

A pooled analysis of individual patient data from three large prospective observational studies was performed. Patients were eligible for the pooled database if they were implanted with a device capable of measuring atrial tachyarrhythmia, had at least 3 months of follow-up and device diagnostic data available, and did not have permanent AF. Among the 22 433 patients enrolled in the three studies, 10 016 (45%) patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Reasons for patients exclusions were a follow-up shorter than 3 months in 32%, incomplete diagnostic data coverage of the follow-up period in 32%, implant of a single-chamber device in 30%, and permanent AF in 6%. Overall, health status at 1-year follow-up was known for 8515 patients (85% of patients included in this analysis).

The current analysis included results from the TRENDS and PANORAMA studies and the Italian ClinicalService® Registry Project. TRENDS (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00279981) was a prospective, observational study designed to assess the relationship between device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmias and thrombo-embolic events with 3045 patients enrolled from 116 sites in USA, Canada, and Australia. PANORAMA (ClinicalTrials.gov.indentifier: NCT00382525) is a prospective, observational study designed to investigate the long-term operation and clinical outcomes of cardiac rhythm management devices. A total of 8522 patients were enrolled between January 2005 and July 2011, with the majority of the patients coming from emerging or developing economies. The Italian ClinicalService® Project (ClinicalTrials.gov.identifier: NCT01007474) is a national cardiovascular data repository and medical care project aimed at describing and improving the use of implantable cardiac devices in 150 Italian cardiology centres. Patient recruitment and follow-up is on-going with 10 866 patients included between January 2004 and July 2011.

PANORAMA and the Italian ClinicalService® Project are observational studies of clinical care where all treatment decisions (including device settings, use of concomitant therapies, and medication) are made by treating physicians. Clinical follow-ups and device interrogations were performed according to the routine practice of the participating centres.10 TRENDS was an observational cohort study with patient eligibility criteria and specified follow-up visits. TRENDS study patients had to have at least one stroke risk factor (including a history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥65 years, diabetes mellitus, or prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack); patients with replacement devices or long-standing permanent AF were excluded. TRENDS patients were followed with device interrogations every 3 months and clinic visits every 6 months for 2 years.7 Patients with a history of paroxysmal and persistent AF were kept in the analysis cohort to reflect the spectrum of patients encountered in daily routine practice and to explore in depth the association between device-detected AF and ischaemic stroke.

Data extraction

Data pooled across all three studies included the following baseline characteristics: gender, AF classification (paroxysmal/persistent), prior stroke, aspirin, antiplatelet and oral anticoagulation use, and CHADS2 scores [congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes, prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack (TIA)] which were calculated for all patients, with or without AF.11 Pooled data collected over the course of patient and device follow-up visits included the number of hours of AF burden detected each day and the occurrence of ischaemic stroke or TIA events. For the Italian ClinicalService® project and PANORAMA study, diagnosis of ischaemic stroke and TIA events were based on the judgement of the treating neurologist; without formal adjudication of medical records by an independent reviewer. In TRENDS, ischaemic stroke and TIA events were adjudicated through medical record review by a committee of three neurologists.

Device-detection of atrial fibrillation burden

Patients had been previously implanted with devices (Medtronic, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) capable of continuous AF detection and monitoring by means of atrial lead and rate detection algorithms. In TRENDS, the protocol specified that AF detection be programmed to nominal settings (atrial rate >175 b.p.m. lasting ≥20 s). In the ClinicalService and PANORAMA studies, nominal device settings were usually applied. The sensitivity and specificity of device detection of AF burden in Medtronic devices has been established in previous studies and has been shown to exceed 95% for both measures.12 The number of minutes of AF recorded in a day (i.e. daily AF burden) was used for analysis and in every patient the maximum daily AF burden experienced during the follow-up was analysed. To investigate the prognostic value of AF burden (i.e. maximum daily AF burden), a range of cut-off points were defined a priori as 5 min, 1, 6, 12, and 23 h. Cut-off points were based on previously reported thresholds (5 min, 6 and 23 h)4,7,8 with additional cut-off points added to have a more complete characterization of the consequences of AF burden. Patients with no AF burden or <5 min of AF burden were categorized as not having AF. A minimum threshold of 5 min of AF burden was previously found to carry clinical relevance4,6–8 and recently the ASSERT trial found that >6 min of AF were associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism.13 The analysis of AF burden continued through our sequence of thresholds to a threshold of 23 h where patients with at least 1 day with at least 23 h of AF burden detected were compared with patients who experienced 0 to 23 h of AF burden as their maximum daily AF burden.

Statistical methods

Data are reported as median and inter-quartile range (IQR) or as number and percentage, as appropriate. Person-years rates of ischaemic stroke and ischaemic stroke plus TIA were calculated for categories of AF burden. Analyses were restricted to patients with at least one follow-up visit and at least 3 months of continuous device monitoring. Multivariable modelling of ischaemic stroke risk was done using Cox regression models with time-dependent covariates.14 In the first analyses, AF burden was entered as a continuous time-dependent covariate. In this analysis, a patient's AF burden could increase but not decrease during the follow-up period. This assumption is clinically justified by the prevalent concept that AF carries a risk of ischaemic stroke independent on its reduction in frequency/duration or its potential disappearance for some time. The results are expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), which can be interpreted as the increase in risk for each additional hour of AF burden experienced. In the second analysis, we used separate Cox regression models where AF burden was entered as a dichotomized time-dependent covariate where the status of the time-dependent indicator variable changed at the moment the patient crossed the AF threshold value. Once a patient has crossed the AF threshold being evaluated they were considered exposed for the remainder of the follow-up period. For each cut-off, ischaemic stroke and TIA events were compared between patients with AF burden below that threshold and patients with AF at or above that threshold. This approach diminishes the relative increase in risk at higher thresholds but reflects the difference in event rates between those above and below the threshold. We adjusted for the CHADS2 stroke risk score and oral anticoagulation use at baseline; both adjusted and unadjusted results are reported. Additionally, we also adjusted for the CHADS2 score, oral anticoagulation use at baseline and study cohort. Patients were censored at the last day of device data available. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). No adjustments for multiplicity were made and a two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

At entry to the study, the median age was 70 years, and 31% were female. A history of prior stroke was present in 6% of the patients and 59% had a CHADS2 score of two or more. Additional baseline characteristics in the aggregate and by individual study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by study

| Total (n = 10 016) | PANORAMA (n = 3556) | TRENDS (n = 2553) | ClinicalService (n = 3907) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (IQR) | 70 (61, 76) | 69 (60, 76) | 73 (64, 79) | 68 (60, 74) |

| Male, n (%) | 6859 (69) | 2096 (59) | 1694 (66) | 3069 (79) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 2537 (25) | 896 (25) | 817 (32) | 824 (21) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5896 (59) | 2116 (60) | 1940 (76) | 1840 (47) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | ||||

| Paroxysmal | 1923 (19) | 784 (22) | 678 (27) | 461 (12) |

| Persistent | 478 (5) | 91 (3) | 48 (2) | 339 (9) |

| Oral anticoagulation, n (%) | 1822 (18) | 631 (18) | 526 (21) | 665 (17) |

| CHADS2 group, n (%) | ||||

| CHADS2 0–1 | 4133 (41) | 1684 (47) | 722 (28) | 1727 (44) |

| CHADS2 2–6 | 5883 (59) | 1872 (53) | 1831 (72) | 2180 (56) |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 589 (6) | 89 (3) | 345 (14) | 155 (4) |

| Device type | ||||

| PM | 4277 (43) | 2726 (77) | 1238 (49) | 313 (8) |

| ICD | 2004 (20) | 404 (11) | 822 (32) | 778 (20) |

| CRT | 3735 (37) | 426 (12) | 493 (19) | 2816 (72) |

IQR, inter-quartile range; PM, pacemaker; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Atrial fibrillation burden during the follow-up

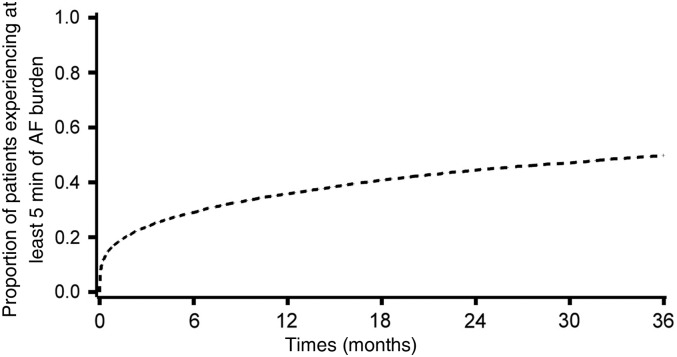

The median duration of follow-up was 24 months (IQR: 14–40 months). During the follow-up, 43% of patients experienced at least 1 day with at least 5 min of AF burden detected. Among these patients, the median time to the first day with at least 5 min of AF was 2 months (IQR: 0.2–9.5) (Figure 1). Within the first 3 months, 24% of patients experienced at least 1 day with 5 min of AF, 18% at least 1 h, 13% at least 6 h, 10% at least 12 h, and 6% experienced at least 1 day with at least 23 h of AF.

Figure 1.

Atrial fibrillation burden along with time during the follow-up. Kaplan–Meier curve of patients experiencing a first day with at least 5 min of atrial fibrillation burden, among all subjects (n = 10 016).

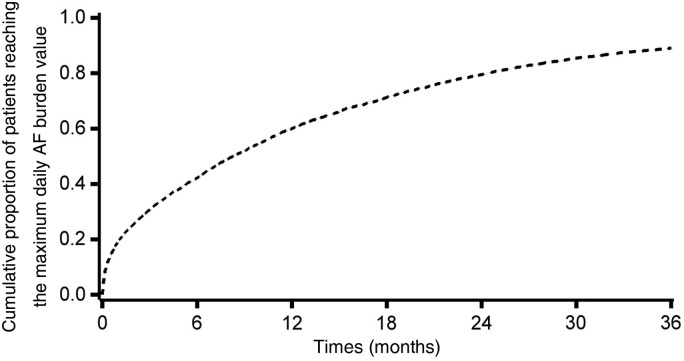

Among patients experiencing at least 1 day of AF burden during the follow-up, the median time to the maximum AF burden was 6 months (IQR: 1.3–14). Figure 2 shows the cumulative proportion over time of patients reaching the day with the maximum observed daily AF burden value during the follow-up. The characteristics of patients at baseline according to the maximum daily AF burden experienced during the follow-up are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion over time of patients reaching the day with the maximum observed daily atrial fibrillation burden value during the follow-up, among patients experiencing at least 1 day of atrial fibrillation burden (n = 4287).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by maximum atrial fibrillation burden experienced during the follow-up

| No AF burden to <5 min of AF burden | ≥5 min to <1 h of AF burden | ≥1 h to <6 h of AF burden | ≥6 h to <12 h of AF burden | ≥12 h to <23 h of AF burden | ≥23 h of AF burden | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 5729 | n = 932 | n = 814 | n = 465 | n = 520 | n = 1556 | ||

| Age, median years (IQR) | 69 (60, 76) | 66 (56, 75) | 71 (63, 78) | 71 (63, 78) | 70 (63, 76) | 72 (65, 77) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 3892 (68) | 624 (67) | 522 (64) | 309 (67) | 364 (70) | 1148 (74) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1515 (27) | 212 (23) | 193 (24) | 112 (24) | 126 (24) | 379 (24) | 0.118 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3414 (60) | 471 (51) | 455 (56) | 279 (60) | 330 (64) | 947 (61) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Paroxysmal | 678 (12) | 106 (11) | 204 (25) | 142 (31) | 215 (41) | 576 (37) | |

| Persistent | 104 (2) | 17 (2) | 25 (3) | 22 (5) | 31 (6) | 279 (18) | |

| Oral anticoagulation, n (%) | 778 (14) | 145 (16) | 130 (16) | 86 (19) | 135 (26) | 548 (35) | <0.001 |

| CHADS2 group, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||||

| CHADS2 0–1 | 2357 (41) | 467 (50) | 344 (42) | 185 (40) | 210 (40) | 570 (37) | |

| CHADS2 2–6 | 3372 (59) | 466 (50) | 470 (58) | 280 (60) | 310 (60) | 986 (64) | |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 320 (6) | 33 (4) | 49 (6) | 28 (6) | 32 (7) | 127 (8) | <0.001 |

Patients were classified according to maximum AF burden experienced prior to stroke. AF, atrial fibrillation; IQR, inter-quartile range.

Risk of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack events associated with atrial fibrillation burden during the follow-up

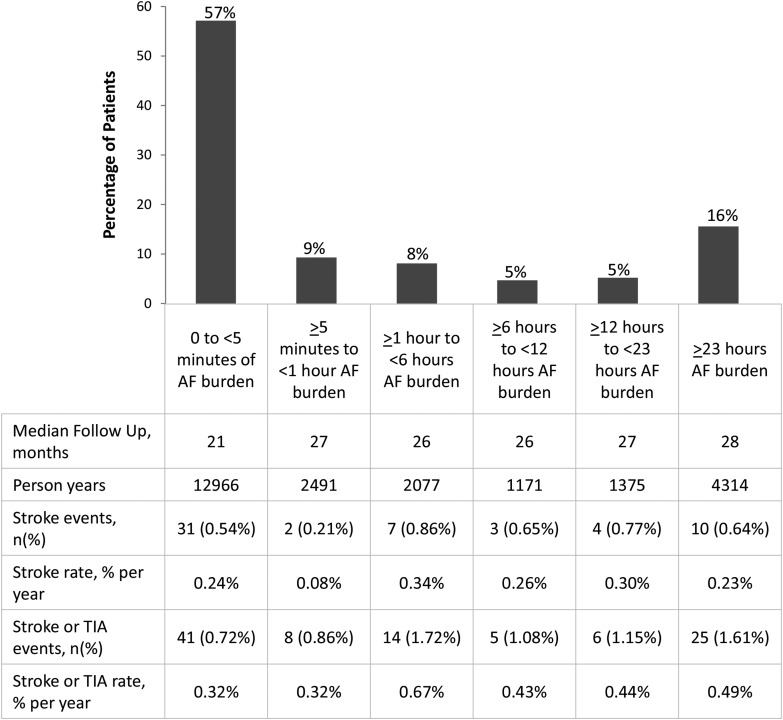

During the follow-up, 95 patients experienced an ischaemic stroke or TIA for an annualized rate of 0.39% per year; 57 events were ischaemic strokes (rate of 0.23% per year). Figure 3 shows the distribution of patients and the unadjusted event rates according to maximum AF burden.

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients according to maximum atrial fibrillation burden experienced during the follow-up. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack events and event rates are given in the table below the figure. Events were classified according to maximum atrial fibrillation burden experienced prior to event occurrence.

Increasing AF burden was significantly associated with increasing age and the CHADS2 score and presence of prior stroke (P < 0.001 for all, see Table 2). Among the observed ischaemic strokes, 26 (46%) had experienced at least 5 min of AF burden prior to the event. Of the 2401 patients with a reported history of AF at enrolment, 32% did not meet the 5 min AF burden threshold during the follow-up.

In Supplementary material online, Table S2 event rates (stroke and stroke + TIA) by study are shown. The rate of strokes or strokes + TIA was particularly low in the ClinicalService population, who compared with the other studies had a higher proportion of patients taking anticoagulants during the follow-up.

Risk of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack events associated with atrial fibrillation burden: continuous analysis

We sought to define the HR for ischaemic stroke at any given maximum AF burden. To this end, we modelled ischaemic stroke risk with AF burden entered as a continuous variable. After adjustment for the CHADS2 score and oral anticoagulation at baseline, there was a significant association between daily AF burden modelled as a continuous variable and ischaemic stroke events with an HR = 1.03 per h (95% CI: 1.00–1.05, P = 0.040). To calculate the HR for any given increase the following formula can be applied:

This result implies that the HR for a maximum AF burden of 6 h was 1.17 (95% CI: 1.01–1.36) and for 12 h the HR was 1.37 (95% CI: 1.01–1.85).

The results were similar for ischaemic stroke and TIA events with an expected HR, for a 6 h AF burden = 1.14 (95% CI: 1.02–1.28) and for a 12 h AF burden = 1.30 (95% CI: 1.03–1.65).

Risk of ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack events associated with atrial fibrillation burden: analysis by dichotomized cut-off thresholds of atrial fibrillation burden

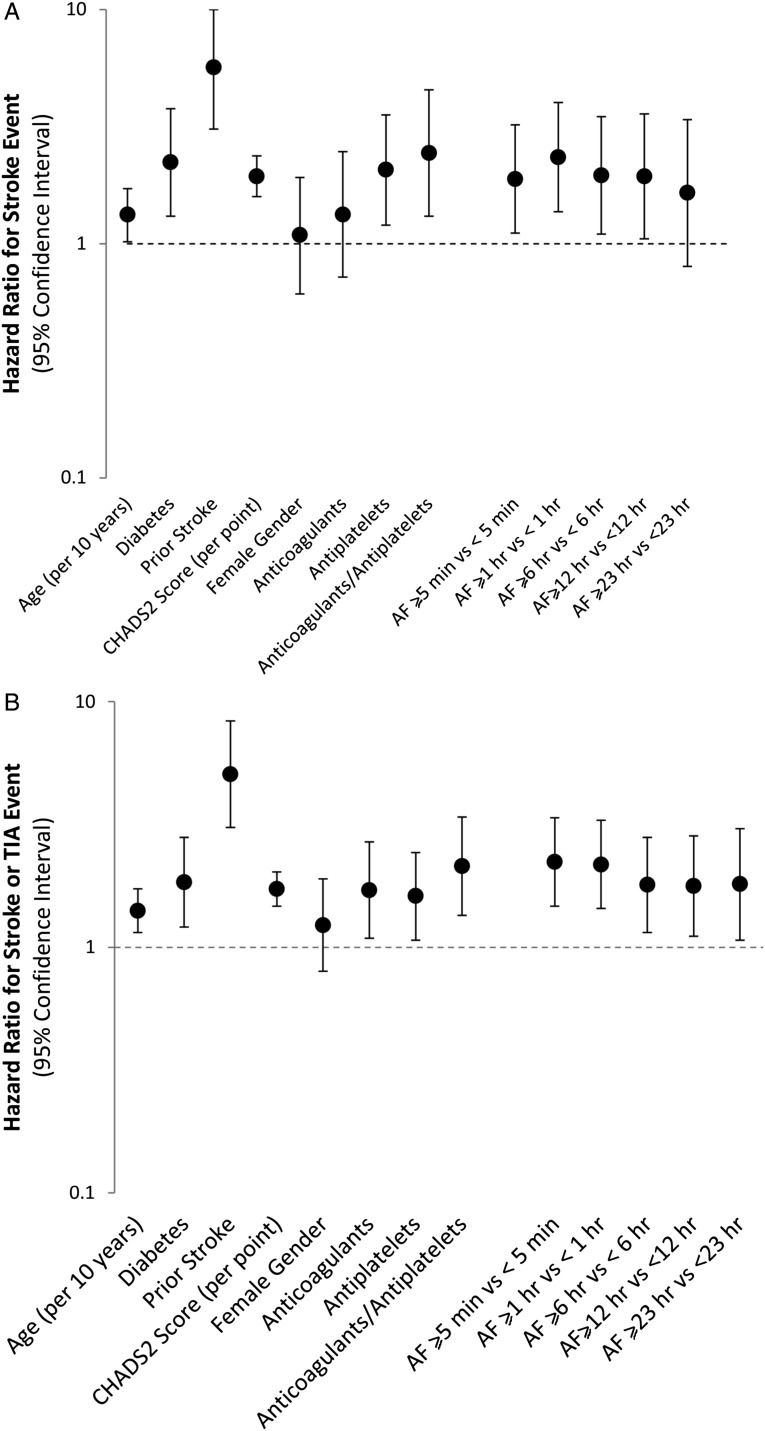

By means of a series of Cox regression models, we explored the association of pre-defined thresholds of AF burden and ischaemic stroke, controlling for the CHADS2 score and anticoagulation use at baseline. The ischaemic stroke HR point estimates were similar for all the thresholds examined, but the highest point estimate was observed for a threshold ≥1 h with an HR of 2.11 (95% CI: 1.22–3.64, P = 0.008). The threshold of ≥5 min was also statistically significantly associated with the occurrence of ischaemic stroke, HR = 1.76 (95% CI: 1.02–3.02, P = 0.041). Atrial fibrillation thresholds of ≥6, ≥12, and ≥23 h did not reach statistical significance: 6 h HR = 1.74 (95% CI: 0.96–3.41, P = 0.067), 12 h HR = 1.72 (95% CI: 0.92–3.22, P = 0.090), and 23 h HR = 1.44 (95% CI: 0.69–3.01, P = 0.332) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

The Forest plot of unadjusted hazard ratios for (A) stroke events and (B) stroke or transient ischaemic attack events. Dotted line indicates line of unity (HR = 1.0) with dots above the line showing increased risk of stroke or (stroke or TIA); bars represent 95% CIs.

Different thresholds of AF burden were also associated with the risk of the composite of ischaemic stroke and TIA. In detail, AF burden threshold ≥5 min had an HR = 2.04 (95% CI: 1.34–3.09, P < 0.001), ≥1 h had an HR = 1.90 (95% 1.25–2.90, P = 0.003), ≥6 h had an HR = 1.53 (95% CI: 0.97–2.41, P = 0.065), ≥12 h had an HR = 1.51 (95% 0.93–2.44, P < 0.092), and ≥23 h had an HR = 1.51 (0.88–2.56, P = 0.132) (Figure 4B).

To minimize the confounding factor of anticoagulation, we performed an additional analysis excluding patients on oral anticoagulation (OAC) at baseline, as well as excluding patients on OAC at baseline and adjusting for the CHADS2 score. The results of this analysis, performed on 8122 patients (Table 3), confirm an increased risk of stroke and stroke + TIA for a device-detected AF burden ≥1 h vs. a device-detected AF burden <1 h, with HR between 1.89 and 2.09.

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis performed on 8122 patients without oral anticoagulation at baseline, adjusted for the CHADS2 score

| Total | Events | HR for AF burden ≥1 h vs. <1 h (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | 8122 | 44 | 2.09 (1.10, 3.96) | 0.0239 |

| Stroke + TIA | 8122 | 69 | 2.05 (1.24, 3.39) | 0.0051 |

| Adjusting for CHADS2 score | ||||

| Stroke | 8122 | 44 | 1.90 (1.00, 3.61) | 0.0487 |

| Stroke + TIA | 8122 | 69 | 1.89 (1.14, 3.12) | 0.0135 |

TIA, transient ischaemic attack; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

When adjusting for study cohort, effect sizes remained similar (AF burden threshold ≥1 h for stroke had an HR = 1.88 (95% CI: 1.08–3.29, P = 0.026) and AF burden threshold ≥1 h for stroke or TIA had an HR = 1.60 (95% CI: 1.03–2.46, P = 0.034).

Discussion

Our pooled analysis shows that in relatively unselected population of patients with an arrhythmia detecting CIED in place, daily AF burden is associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke or TIA even after adjustment for oral anticoagulants use and CHADS2 score. These data add to the current evidence that measuring daily AF burden may have important clinical relevance13 and support the search for specific thresholds of AF burden associated with a substantial increase in the risk of ischaemic stroke.15 We found that for every additional hour increase in the daily maximum of AF burden the relative risk for stroke increases by ∼3%. A daily maximum of 6 h AF burden implies an increase in risk of stroke of 17% and a 12 h AF burden implies a 37% increase in risk. When we analysed AF burden as a dichotomized outcome, a threshold of ≥1 h gave the strongest results.

The ASSERT study analysed the risk associated with the occurrence of any AF in the first 3 months of observation and found that device-detected AF lasting only 6 min in duration was associated with a 2.5-fold increase in the risk of ischaemic stroke or systemic embolism over a follow-up of 2.5 years.13 Our study differs from ASSERT because our study population is less selected (only 29% were ASSERT-like, i.e. age >65, no previous AF and hypertensive). Our analysis offers a complementary approach as it was focused not only on the risk associated with AF detected in the first 3 months of observation, but considered AF occurring at any time during the follow-up. This approach may be clinically relevant since patients may develop or reach the maximum AF burden at varying time intervals during the observation period, with a median time to the maximum AF burden of 6 months (Figure 1). According to this finding, our study provides an analysis of the clinical implications of device-detected AF burden with a wider clinical perspective compared with ASSERT,13 where the focus was on the implications of AF burden detected in the first 3 months of observation.

With the advent of CIEDs that have improved arrhythmia detection algorithms and memory capabilities, as well as the advent of remote monitoring, there is frequent detection of episodes of AF of variable duration, usually silent in device clinics.2 The diagnostic accuracy of pacemaker and ICDs with an atrial lead is very high, with appropriate detection of 95% of AF episodes,12 while for implantable loop recorders, not included in this data set, the specificity is ∼85%.16 A recent editorial commenting on the clinical implications of device-detected AF according to ASSERT findings15 pointed out that there is need to identify precise thresholds of AF burden associated with clinically relevant increases in the risk of stroke. The assessment of AF burden thresholds associated with increasing risks of stroke is important and our study provides a contribution in the field.

Clinical decisions regarding the prescription of antithrombotic prophylaxis are based on risk stratification, frequently using the CHADS2 score and an assessment of the individual's bleeding risk, as well as patient preferences.17–19 Our continuous analysis helps to assess the additional impact of quantified AF burden on stroke risk in patients with AF. Moreover, quantified AF burden provided by implanted devices may be clinically important, since it has been observed that providing physicians with timely information on AF burden may result in an increased prescription of appropriate antithrombotic prophylaxis.20 Our dichotomized analysis shows that after adjustment for the CHADS2 score and oral anticoagulants use, device-detected AF burden is associated with an increased risk of stroke; of the several cut-points evaluated, the 1 h threshold appears to be the most robust with a doubling in the risk of stroke. Choice of a potential threshold of AF burden associated with an increased risk of stroke remains problematic. As a matter of fact, when increasing the duration of AF burden (i.e. to 12 or 23 h) the discriminatory capability is lost, probably because the risk is consistent also below the proposed threshold. The prognostic implications of AF burden <5 min are at present unknown for patients carrying a pacemaker or an implantable defibrillator.

We recognize that our study has limitations. There may be confounding factors associated with AF burden that we have not accounted for in our analyses, for example, the differences in follow-up timing between the three studies. In our study, the absolute event rate of ischaemic stroke was low, perhaps reflecting a general trend towards lower rates of ischaemic strokes in comparison with what predicted by CHADS2, a score validated >10 years ago in a group of patients with a mean age of 81 years derived from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation, with a high prevalence of heart failure.21 It is noteworthy that also in ASSERT,13 the actual risk of stroke in patients with device-detected AF was much lower than that expected by the CHADS2 score, possibly reflecting a general temporal trend towards a progressive reduction incidence of stroke in developed countries.22,23 Moreover, the low rate of ischaemic strokes observed even among patients experiencing sizable AF burdens may reflect the long periods of sinus rhythm experienced by our patients and better treatment of stroke risk factors. In addition, some degree of under-reporting of ischaemic stroke and TIA events cannot be ruled out with the study designs used and this has to be considered in the clinical interpretation of the rather low stroke rates.

Stroke risk can also be reduced by use of anticoagulants, whose implementation is more common in higher CHADS2 categories. We accounted for the use of anticoagulants in our multivariable models and also by excluding patients on anticoagulants in a secondary analysis. In these additional analyses, performed by excluding patients on anticoagulants at baseline, as well as by excluding patients on OAC at baseline and adjusting for the CHADS2 score, the significantly increased risk of stroke and stroke + TIA for a device-detected AF burden ≥1 h vs. a device-detected AF burden <1 h was confirmed, with HR between 1.89 and 2.09.

In summary, our results show that monitoring AF burden continuously (made possible by the information from an implanted device) may allow timely evaluation of the risk of ischaemic stroke faced by patients with AF. Its comprehensive nature avoids the problem of missed episodes of AF inherent in intermittent monitoring for detecting clinically silent AF. It is noteworthy that in our population of over 10 000 patients the day with the maximum AF duration occurred after a mean of 6 months of monitoring. On-going and future studies, also using remote transmission of data on AF burden, will allow more precise assessment of the ways to integrate information on specific levels of AF burden (i.e. ≥1 h) into clinical decision-making tailored to reduce stroke risk.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

The study was sponsored by Medtronic, who covered the expenses for one meeting among the main Investigators and for phone conferences on data interpretation and manuscript preparation. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Research & Technology Department Medtronic Bakken Research Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Conflict of interest: G.B. received speaker fees (small amount) from Medtronic Inc. T.V.G. has consulting (small): Medtronic and St Jude; Speakers bureau (small) : Medtronic, Inc., St Jude, and Boston Scientific. M.G.: Advisory Board Medtronic and Boston Scientific. M.S. receives research grant support from Medtronic, St Jude Medical, and Biotronik and honoraria from Medtronic and Bayer; has a speakers' bureau appointment with MSD, Medtronic, St Jude Medical, and AstraZeneca; and has an advisory board relationship with Boehringer Ingelheim. Prof. J.A.C. serves as advisor and speaker for Astra Zeneca, ChanRX, Gilead, Merck, Menarini, Otsuka, Sanofi, Servier, Xention, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi, Pfizer, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Medtronic, St Jude Medical, Actelion, GlaxoSmithKline, InfoBionic, Incarda, Johnson and Johnson, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Takeda. T.L. has received lecture fees Medtronic, Sanofi, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. M.S. has no conflict of interest. D.E.S. has received research grants from Daiichi Sankyo and Johnson and Johnson and has served as a consultant to Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Johnson and Johnson, Medtronic, Pfizer, and St Jude Medical. T.M.W.West and M.D.M. are employees of Medtronic, Inc. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and takes the responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Paul Ziegler, Andrea Grammatico and Stelios Tsintzos for their valuable contribution to the manuscript revision. Moreover, the authors are indebted with all the investigators from TRENDS, ClinicalService, and PANORAMA studies for their support to the whole project.

References

- 1.Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Van Gelder IC, Bax J, Hylek E, Kaab S, Schotten U, Wegscheider K, Boriani G, Brandes A, Ezekowitz M, Diener H, Haegeli L, Heidbuchel H, Lane D, Mont L, Willems S, Dorian P, Aunes-Jansson M, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borentain M, Breitenstein S, Brueckmann M, Cater N, Clemens A, Dobrev D, Dubner S, Edvardsson NG, Friberg L, Goette A, Gulizia M, Hatala R, Horwood J, Szumowski L, Kappenberger L, Kautzner J, Leute A, Lobban T, Meyer R, Millerhagen J, Morgan J, Muenzel F, Nabauer M, Baertels C, Oeff M, Paar D, Polifka J, Ravens U, Rosin L, Stegink W, Steinbeck G, Vardas P, Vincent A, Walter M, Breithardt G, Camm AJ. Comprehensive risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation: emerging diagnostic and therapeutic options—a report from the 3rd Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace. 2012;14:8–27. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Camm AJ, Corbucci G, Padeletti L. Usefulness of continuous electrocardiographic monitoring for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, Borowsky L, Pomernacki NK, Singer DE. Comparison of risk stratification schemes to predict thromboembolism in people with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:810–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glotzer TV, Hellkamp AS, Zimmerman J, Sweeney MO, Yee R, Marinchak R, Cook J, Paraschos A, Love J, Radoslovich G, Lee KL, Lamas GA. Atrial high rate episodes detected by pacemaker diagnostics predicts death and stroke. Circulation. 2003;107:1614–1619. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057981.70380.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capucci A, Santini M, Padeletti L, Gulizia M, Botto G, Boriani G, Ricci R, Favale S, Zolezzi F, Di Belardino N, Molon G, Drago F, Villani GQ, Mazzini E, Vimercati M, Grammatico A. Monitored atrial fibrillation duration predicts arterial embolic events in patients suffering from bradycardia and atrial fibrillation implanted with antitachycardia pacemakers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1913–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botto GL, Padeletti L, Santini M, Capucci A, Gulizia M, Zolezzi F, Favale S, Molon G, Ricci R, Biffi M, Russo G, Vimercati M, Corbucci G, Boriani G. Presence and duration of atrial fibrillation detected by continuous monitoring: crucial implications for the risk of thromboembolic events. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2008.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, Singer DE, Ezekowitz MD, Hilker C, Miller C, Qi D, Ziegler PD. The relationship between daily atrial tachyarrhythmia burden from implantable device diagnostics and stroke risk. The TRENDS Study. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009;2:474–480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.849638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boriani G, Botto GL, Padeletti L, Santini M, Capucci A, Gulizia M, Ricci R, Biffi M, De Santo T, Corbucci G, Lip GY. Improving stroke risk stratification using the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc risk scores in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation patients by continuous arrhythmia burden monitoring. Stroke. 2011;42:1768–1770. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.609297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Corbucci G, Artyomenko S, Turov A, Shirokova N, Karaskov A. Use of an implantable monitor to detect arrhythmia recurrences and select patients for early repeat catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a pilot study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:823–831. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.964809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santini M, Gasparini M, Landolina M, Lunati M, Proclemer A, Padeletti L, Catanzariti D, Molon G, Botto GL, La Rocca L, Grammatico A, Boriani G. Device-detected atrial tachyarrhythmias predict adverse outcome in real-world patients with implantable biventricular defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.08.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welles CC, Whooley MA, Na B, Ganz P, Schiller NB, Turakhia MP. The CHADS2 score predicts ischemic stroke in the absence of atrial fibrillation among subjects with coronary heart disease: Data from the Heart and Soul Study. Am Heart J. 2011;162:555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purerfellner H, Gillis AM, Holbrook R, Hettrick DA. Accuracy of atrial tachyarrhythmia detection in implantable devices with arrhythmia therapies. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27:983–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, Lau CP, Fain E, Yang S, Bailleul C, Morillo CA, Carlson M, Themeles E, Kaufman ES, Hohnloser SH. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:120–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS: A Practical Guide. 1st ed. Gary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamas G. How much atrial fibrillation is too much atrial fibrillation? N Engl J Med. 2012;366:178–180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1111948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hindricks G, Pokushalov E, Urban L, Taborsky M, Kuck KH, Lebedev D, Rieger G, Pürerfellner H. Performance of a new leadless implantable cardiac monitor in detecting and quantifying atrial fibrillation: results of the XPECT trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:141–147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.877852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lip GY. Stroke and bleeding risk assessment in atrial fibrillation: when, how, and why? Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1041–1049. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boriani G, Cervi E, Diemberger I, Martignani C, Biffi M. Clinical management of atrial fibrillation: need for a comprehensive patient-centered approach. Chest. 2011;140:843–845. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719–2747. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boriani G, Santini M, Lunati M, Gasparini M, Proclemer A, Landolina M, Padeletti L, Botto GL, Capucci A, Bianchi S, Biffi M, Ricci RP, Vimercati M, Grammatico A, Lip GY. Improving thromboprophylaxis using atrial fibrillation diagnostic capabilities in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: The Multicentre Italian ANGELS of AF Project. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:182–188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285:2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, Alwell K, Woo D, Flaherty ML, Khatri P, Adeoye O, Ferioli S, Broderick JP, Kissela BM. Stroke incidence is decreasing in whites but not in blacks: a population-based estimate of temporal trends in stroke incidence from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. Stroke. 2010;41:1326–1331. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wieberdink RG, Ikram MA, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Trends in stroke incidence rates and stroke risk factors in Rotterdam, the Netherlands from 1990 to 2008. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9673-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.