Abstract

The emergence of functional neuronal connectivity in the developing cerebral cortex depends on neuronal migration. This process enables appropriate positioning of neurons and the emergence of neuronal identity so that the correct patterns of functional synaptic connectivity between the right types and numbers of neurons can emerge. Delineating the complexities of neuronal migration is critical to our understanding of normal cerebral cortical formation and neurodevelopmental disorders resulting from neuronal migration defects. For the most part, the integrated cell biological basis of the complex behavior of oriented neuronal migration within the developing mammalian cerebral cortex remains an enigma. This review aims to analyze the integrative mechanisms that enable neurons to sense environmental guidance cues and translate them into oriented patterns of migration toward defined areas of the cerebral cortex. We discuss how signals emanating from different domains of neurons get integrated to control distinct aspects of migratory behavior and how different types of cortical neurons coordinate their migratory activities within the developing cerebral cortex to produce functionally critical laminar organization.

Keywords: cerebral cortex, laminar organization, projection neurons, interneurons, radial migration, tangential migration

INTRODUCTION

Neuronal migration and the resultant placement of neurons enable the establishment of functional neuronal connectivity in the developing brain. The two major types of cortical neurons, glutamatergic excitatory projection (pyramidal) neurons and GABAergic inhibitory interneurons, arise from distinct sets of progenitor cells within the telencephalon and migrate over remarkably long distances to their unique areal and laminar locations in the developing neocortex. Correct positioning of newborn neurons within the six-layered neocortex ensures the emergence of proper identities and, thus, appropriate patterns of functional connectivity between the right types and numbers of neurons. Disruptions in neuronal migration result in a plethora of neurodevelopmental disorders, ranging from gross brain malformations such as lissencephaly to neurobehavioral disorders such as autism, underscoring the importance of this process in proper cortical development and function. Postnatally, neuronal migration continues to play an important role in the ongoing maintenance of neuronal circuitry in selective niches of the adult brain. Unraveling the complexities of neuronal migration is thus essential to our understanding of both normal cortical development and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Significant progress has been made toward defining many mechanisms underlying neuronal migration. However, we still do not fully understand how neurons integrate a multitude of signals to produce oriented and coordinated patterns of migration evident in the developing cerebral cortex. In this review, we analyze how neurons navigate from their sites of birth to their target positions within the cerebral cortex, and we focus on mechanisms that enable neurons to sense and integrate the diverse cellular signals necessary to produce distinct patterns of oriented migration toward defined cortical areas. We discuss how signals emanating from different cellular domains (e.g., cell soma, primary cilia, and growth cones) are integrated and how they control distinct aspects of neuronal migratory behavior. Furthermore, we address how different types of neurons (projection neurons and interneurons) coordinate their oriented migratory activities within the developing cerebral cortex to ultimately produce functional laminar organization.

MIGRATION OF PROJECTION NEURONS: RADIAL MIGRATION

Cortical projection neurons arise from undifferentiated neuroepithelial progenitor cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) and subventricular zone (SVZ) of the telencephalon (Ayala et al. 2007, Bystron et al. 2008, Götz & Huttner 2005, Higginbotham et al. 2011, Kriegstein et al. 2006). At the start of corticogenesis, radial glial progenitors (RGPs) in the VZ expand their population by dividing symmetrically to produce two daughter RGPs. As neurogenesis begins, the majority of RGPs in the VZ divide asymmetrically (Higginbotham et al. 2011; Noctor et al. 2001, 2004, 2008). Several modes of asymmetric cell division are recognized within the VZ: (a) neurogenic division (produces a self-renewing RGP and a daughter neuron), (b) asymmetric progenitor division [results in a self-renewing RGP and an intermediate progenitor (IP) cell that migrates into the SVZ], and (c) final gliogenic division (results in a neuron and a daughter cell that translocates away from the VZ to differentiate into astroglia) (Kriegstein et al. 2006; Noctor et al. 2004, 2008). In the SVZ, all of the IPs divide symmetrically to produce either two neurons (the majority of divisions) or two daughter IPs (Kriegstein et al. 2006; Martínez-Cerdeño et al. 2006; Noctor et al. 2004, 2007, 2008). In addition, a novel class of asymmetrically dividing radial glia–like progenitor cells, termed outer radial glial cells, has been identified recently in the outer SVZ region (Hansen et al. 2010, LaMonica et al. 2012, X. Wang et al. 2011). Neurogenesis subsides when the progenitor pool is depleted owing to both terminal IP divisions into neurons and terminal RGP divisions into glia (Ayala et al. 2007, Higginbotham et al. 2011, Noctor et al. 2004).

Newly born projection neurons, which constitute the majority of cortical neurons, reach their target locations within the developing cortex via radial migration (reviewed in Ayala et al. 2007, Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Marín et al. 2010) (Figure 1). The earliest-arriving neurons form the transient preplate (PP) and are followed by the neurons that form the cortical plate (CP). The CP neurons split the PP into the superficial marginal zone (MZ, or layer 1) and the subplate (SP), which is located below the newly forming cortical layer 6 (Ayala et al. 2007, Ghashghaei et al. 2007, Kwan et al. 2012, Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Marín et al. 2010). Successive waves of migrating neurons arrive to occupy progressively more superficial cortical layers in an inside-out fashion; in other words, neurons belonging to the deepest cortical layers are generated first and arrive at their destinations first, followed by neurons that will reside in the upper layers. However, recent data also suggest that at least a subset of RGPs is specified to generate only upper-layer neurons irrespective of niche and birthdate (Franco et al. 2012).

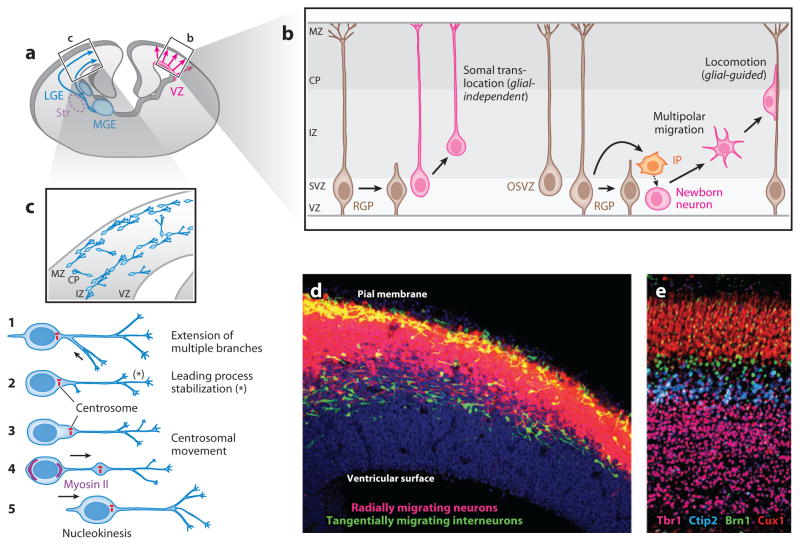

Figure 1.

Neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. (a) Projection neurons ( pink) and interneurons (blue) originate from distinct proliferative domains and migrate into the developing cerebral wall. (b) Projection neurons, generated from radial glial progenitors (RGPs, brown) or intermediate precursors (IPs, orange), migrate using either radial-glial-independent somal translocation or glial-guided locomotion. Newborn neurons undergo a multipolar transition phase prior to glial-guided radial migration. (c) Interneurons migrate in multiple streams into the pallium. They extend multiple leading branches ➀, followed by branch stabilization ➁, centrosomal movement ➂, ➃, and forward nucleokinesis ➄. (d ) Radially migrating neurons (magenta) and tangentially migrating interneurons ( green) in the E14.5 mouse cerebral wall. (e) Coordinated migration of these neurons during development leads to the laminar organization of neurons in the cerebral cortex. Neurons in different layers of postnatal day 0 cortex are labeled with antibodies to Ctip2 (blue, layer V), Cux1 (red, layers II–IV), Brn1 ( green, layers II–V), and Tbr1 (magenta, layer VI). Adapted from Higginbotham et al. (2012). Abbreviations: CP, cortical plate; IZ, intermediate zone; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence; MGE, medial ganglionic eminence; MZ, marginal zone; OSVZ, outer subventricular zone progenitor; Str, striatum; SVZ, subventricular zone; VZ, ventricular zone.

Radial migration occurs in two different modes: somal translocation and locomotion (Kriegstein & Noctor 2004, Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Nadarajah & Parnavelas 2002, Nadarajah et al. 2001) (Figure 1). The earliest neurons that form the PP use somal translocation, whereas most cortical neurons forming the CP employ locomotion.

Somal Translocation Versus Locomotion

Early-born cortical neurons possess a long, branched leading process attached to the pial surface (Miyata et al. 2001, Nadarajah et al. 2001). The leading process gets progressively shorter as the cell soma translocates upward (Nadarajah et al. 2001) (Figure 1). These somally translocating neurons move continuously, without significant pausing (Nadarajah et al. 2001). Importantly, this mode of migration does not depend on radial glial guides, but attachment of the leading process to the intact pial basement membrane is likely required (Hawthorne et al. 2010, Marín & Rubenstein 2003).

Neurons that migrate via locomotion are morphologically distinct from the translocating neurons. They possess short, unbranched leading and trailing processes that extend and retract rapidly, resulting in forward movements of the entire cell, interrupted by stationary phases (Ayala et al. 2007, Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Nadarajah et al. 2001). A fundamental feature of migration via locomotion is the involvement of radial glial cells, highly polarized cortical progenitor cells that not only serve as precursors to the majority of cortical neurons but also provide an instructive scaffold for neuronal migration (Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Marín et al. 2010, Noctor et al. 2001, Rakic 1972) (Figure 1). Polarized glial cells have a characteristic pear-shaped soma positioned in the VZ, a short apical process anchored at the ventricular surface, and a long basal process that extends through the cerebral wall toward the pial surface and is attached to the pial basal membrane (Ayala et al. 2007) (Figure 1). Radial glial processes function as guides that direct migrating neurons from their birthplace in the VZ to their final destination in the cerebral cortex. Radial glial scaffold is by no means static, because adjacent radial glial cells constantly probe each other and the neurons in contact with them (Yokota et al. 2010). This constant remodeling of the dynamic radial glial scaffold may restrict the dispersion and patterns of radial migration of isogenic cohorts of neurons and, thus, may affect columnar and laminar organization of the neocortex.

Neurons migrating by locomotion switch to somal translocation during the final stages of their migration, right after their leading process makes contact with the MZ (Nadarajah et al. 2001), which implies that these two modes of radial migration are not entirely neuronal-type specific. However, considering differences in the morphologies of locomoting and translocating cells, as well as differences in how they move (continuous translocation versus saltatory movement of locomoting neurons), the two modes of radial migration are likely mediated by different mechanisms (Franco et al. 2011, Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Nadarajah et al. 2001). Different effects of gene mutations that disrupt cortical development support this possibility. For example, mutations that affect glial-independent translocation result in unsplit PP, whereas mutations that affect glial-dependent locomotion result in the formation of normal PP but a failure to position late-born neurons properly (Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Nadarajah et al. 2001). Further, the two modes of radial migration may have evolved independently (Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Nadarajah et al. 2001) and reflect the differences in cortical organization complexity: Somal translocation is used when the cerebral wall is still thin and distances that neurons need to migrate are relatively short, whereas radial glia–dependent locomotion is required to guide migrating neurons along more convoluted (and longer) paths in complex cortices (Nadarajah & Parnavelas 2002).

Multipolar Phase of Radial Migration

Radial glia–guided neurons assume a characteristic bipolar morphology, with a long leading process oriented toward the pial surface and a shorter trailing process in the direction of the VZ. However, several studies have identified a distinct population of migrating cells within the lower intermediate zone (IZ) and SVZ: multipolar neurons that possess multiple thin processes that extend and retract in a dynamic but apparently random fashion (LoTurco & Bai 2006, Tabata & Nakajima 2003, Tabata et al. 2009). These multipolar neurons do not seem to require radial glia and move at a slower speed in the direction of the pial surface, occasionally reverting back to the ventricular surface and then reassuming pia-oriented migration (Tabata & Nakajima 2003, Tabata et al. 2009). Importantly, the multipolar stage is transient and is followed by a switch back to the bipolar morphology and locomotion-based mechanism of migration (Noctor et al. 2004, Tabata et al. 2009). Several recent studies have suggested that this transient stage is critical for the progressive emergence of different neuronal layer identities and proper cortical lamination ( Jossin & Cooper 2011, Miyoshi & Fishell 2012, Ohshima et al. 2007, Pacary et al. 2011).

MIGRATION OF INTERNEURONS: TANGENTIAL MIGRATION

The inhibitory interneurons of the cerebral cortex arise mainly from the medial and caudal ganglionic eminences (MGE and CGE) and the preoptic area (POA) within the ventral telencephalon, and they migrate tangentially (orthogonal to the radial glial scaffold) into the developing neocortex (Anderson et al. 1997, 2001; Batista-Brito & Fishell 2009; Faux et al. 2012; Gelman & Marín 2010; Gelman et al. 2009; Ghashghaei et al. 2007; Kriegstein & Noctor 2004; Lavdas et al. 1999; Marín & Rubenstein 2001; Miyoshi et al. 2010; Nery et al. 2002; Tan et al. 1998; Wichterle et al. 1999, 2001; Wonders & Anderson 2006; Yozu et al. 2005) (Figure 1). Similarly to projection neurons, interneurons contribute to the inside-out pattern of the neocortex lamination (Ang et al. 2003, Rakić et al. 2009, Valcanis & Tan 2003). However, correct laminar positioning of interneurons also depends on their place of origin; for example, CGE-derived interneurons preferentially migrate to the more superficial cortical layers, irrespective of their time of birth (Faux et al. 2012, Miyoshi & Fishell 2011, Miyoshi et al. 2010, Rymar & Sadikot 2007, Yozu et al. 2004).

Unlike projection neurons, cortical interneurons comprise a highly heterogeneous group of neurons with different molecular, morphological, and electrophysiological characteristics (Corbin & Butt 2011, DeFelipe et al. 2013, Faux et al. 2012, Gelman & Marín 2010, Rudy et al. 2011). Generation of interneuron diversity is controlled by a spatially and temporally regulated transcription factor matrix within the GEs (Butt et al. 2005, 2008; Faux et al. 2012; Kwan et al. 2012; Marín & Rubenstein 2003; Miyoshi et al. 2007; Wonders et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2004). Distinct interneuron subtypes exhibit different migration patterns and migratory dynamics (Marín & Rubenstein 2003, Yokota et al. 2007).

Migration of cortical interneurons involves oriented exit from the GE toward the cortex as well as migration within the cortex toward specific areal and laminar positions. Interneurons exiting from the GE avoid entering the striatum and migrate into the cortex through the MZ or SP or stream along the lower IZ/SVZ (Ang et al. 2003; Faux et al. 2012; Kriegstein & Noctor 2004; Lavdas et al. 1999; Marín & Rubenstein 2001, 2003; Marín et al. 2001; Métin et al. 2006) (Figure 1). Once in the cortex, several modes of migration are used by the interneurons. First, a significant number of interneurons undergo multidirectional tangential migration in multiple zones of the cortex (Ang et al. 2003; Tanaka et al. 2003, 2006; Yokota et al. 2007), during which interneurons migrate over long distances and in different directions. This mode of migration may help disperse interneurons across the neocortex to achieve proper laminar organization (Tanaka et al. 2006). Second, a subpopulation of interneurons exhibit ventricle-oriented migration (Nadarajah et al. 2002), during which interneurons within the IZ migrate first toward the ventricle before migrating radially to their position within the CP, possibly to obtain layer information for correct cortical positioning or to modulate proliferation of ventricular progenitors. Lastly, tangentially migrating streams of interneurons switch to radial migration as they move toward specific laminar locations within the CP (Faux et al. 2012, Nadarajah et al. 2002, Yokota et al. 2007).

Although it has been suggested that interneurons do not depend on radial glia for their migration (Marín & Rubenstein 2003) and may rely more on developing axons as substrates, recent evidence suggests that dynamic interactions between specific subtypes of interneurons and radial glial guides may influence the final trajectories of interneuron migration and, thus, their positioning in the developing cortex (Polleux et al. 2002, Poluch & Juliano 2007, Yokota et al. 2007). Once within the developing cortical layers, interactions with the excitatory projection neurons enable the final positioning of the interneurons (Lodato et al. 2011). In summary, the ventral germinal zone of origin of interneurons, interactions with developing axonal fibers and radial glial scaffold, and local interactions with projection neurons in the emerging CP influence the final areal and laminar positioning of interneurons.

CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF ORIENTED NEURONAL MIGRATION

Migrating cortical neurons in general follow three major steps as they navigate toward their target: (a) formation and extension of a leading process, (b) nucleokinesis, and (c) retraction of the trailing process (Marín et al. 2010) (Figure 1). Distinct types of neurons possess morphologically distinct leading processes (i.e., the single unbranched leading process of the radially migrating projection neurons, the multiple thin leading processes of multipolar neurons, and the constantly branching leading process of the tangentially migrating interneurons), but in all cases the leading process serves as a compass that directs oriented migration by responding to various chemotactic, chemoattractant, or chemorepellent gradients (Faux et al. 2012, Marín et al. 2010, Trivedi & Solecki 2011). The cell soma remains largely static while the leading process explores the environment. The dynamism of the leading process and its influence on directional migration is particularly prominent in the interneurons. In these neurons, the leading process branches continuously until a single branch is selected and oriented toward the direction of movement, and the rest of the branches retract (Faux et al. 2012, Marín et al. 2010, Trivedi & Solecki 2011). Signaling from the primary cilium in these neurons may help them sense orienting cues (Baudoin et al. 2012, Higginbotham et al. 2012) (see below). Stabilization of the selected leading process is followed by translocation of the centrosome and the Golgi complex toward the selected branch, followed by nuclear translocation and trailing-process retraction (Marín et al. 2010, Trivedi & Solecki 2011) (Figure 1). This process is repeated to facilitate directional movement of interneurons into the cerebral cortex. Trailing-process retraction is thought to push the nucleus forward by squeezing it at the rear, thus enabling nuclear translocation. The leading-process extension, nucleokinesis, and trailing-process retraction of the migrating neurons depend on integration of extrinsic cues and the resultant dynamic rearrangements of the cytoskeletal functions.

A coordinated network of signaling pathways emanating from different domains of the neurons (e.g., cell soma, growth cone, and primary cilium) controls cytoskeletal rearrangements that ultimately lead to oriented neuronal movement. However, the integration of the components of these networks in controlling oriented neuronal migration remains elusive. Nevertheless, glimpses into the common mechanisms that are used by these networks to regulate both radial and tangential migration, and into how different signaling pathways converge on the cytoskeleton to drive oriented neuronal migration, are beginning to emerge.

Leading-Process Activities, Secreted or Cell-Surface Guidance Cues, and Patterns of Cortical Neuronal Migration

Regulation of both the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton in the leading process of migrating neurons is important for their dynamics. Many aspects of the guidance cue–mediated leading-process extension are shared between neuronal migration and axon guidance. Growth cones, which are dilated ends of both axons and dendrites, are highly dynamic structures that constantly extend and retract membrane protrusions to probe the environment (Dent et al. 2011). Both the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton are involved in changing growth cone morphology in response to guidance cues, many of which have also been shown to regulate leading-process dynamics in migrating neurons (Dent et al. 2011, Marín et al. 2010).

Secreted guidance cues and patterns of neuronal migration

A large number of secreted molecules and their corresponding receptors regulate oriented neuronal migration (Table 1) (Figure 2). Semaphorins provide an illustrative model of how secreted cues can coordinately regulate distinct patterns of neuronal migration in the neocortex. Class 3 semaphorins, a class of chemorepellents originally identified as regulators of axon guidance, bind to their corresponding coreceptors, neuropilins and plexins (Ayala et al. 2007, Kolodkin & Tessier-Lavigne 2011, Manns et al. 2012, Raper 2000, Tamagnone & Comoglio 2004), and regulate cytoskeletal dynamics, mainly via Rho GTPases and their associated proteins. In axon guidance, semaphorin-mediated signaling leads to growth cone collapse via several mechanisms. The GTPase-activating domain of plexins promotes activation of the Rho GTPase Rac1, which in turn activates LIMK1, a kinase that phosphorylates and inactivates cofilin, an important regulator of actin dynamics. Semaphorin 3A/LIMK1-mediated inhibition of cofilin results in decreased actin turnover and decreased motility, leading to growth cone collapse (Aizawa et al. 2001, Endo et al. 2003, Liu & Strittmatter 2001, Pasterkamp 2012, Västrik et al. 1999, Zhou et al. 2008). Alternatively, semaphorin 4D/plexin-B1 signaling mediates growth cone collapse via activation of a GTPase RhoA in the growth cone, which results in increased actin contractility (Swiercz et al. 2002). Lastly, semaphorin-mediated signaling has also been shown to stimulate RapGAP (GTPase-activating protein) activity of full-length plexin (Wang et al. 2012), thus contributing to growth cone collapse. Additionally, semaphorin-mediated signaling regulates microtubule dynamics during growth come collapse via GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of CRMP2, leading to microtubule destabilization (Gu & Ihara 2000, Uchida et al. 2005, Zhou et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Genes regulating cortical neuronal migration

| Secreted and substrate-bound guidance cues | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Protein | Role | Tangential migration | Radial migration | Both | References |

| Bdnf | BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) | Stimulates tangential migration, transition from tangential to radial migration of medial ganglionic eminence (MGE)-derived interneurons | ✓ | Alcántara et al. 2006, Polleux et al. 2002 | ||

| Cxcl12 | CXCL12 (C-X-C motif ligand 12)/SDF-1 (stromal cell-derived factor-1) | Ligand of CXCR4 and CXCR7 receptors, attractive guidance cue for interneurons | ✓ | Stumm et al. 2003 | ||

| Efna5 | Ephrin A5 | Ephrin ligand, repulsive guidance cue | ✓ | Nomura et al. 2006, Villar-Cerviño et al. 2013 | ||

| Egf | EGF (epidermal growth factor) | EGFR ligand, attractive guidance cue | ✓ | Caric et al. 2001, Puehringer et al. 2013 | ||

| GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) | Inhibitory neurotransmitter that binds to GABA receptors, regulates tangential and radial migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Behar et al. 1996, Behar et al. 1998, Bolteus & Bordey 2004, Bortone & Polleux 2009, Cuzon et al. 2006, López-Bendito et al. 2003 | |

| Gdnf | GDNF (glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor) | GFRα-1 ligand, attractive guidance cue for interneurons | ✓ | Pozas & Ibáñez, 2005 | ||

| Glutamate | Excitatory neurotransmitter that binds to AMPA and NMDA receptors and regulates tangential and radial migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Behar et al. 1999, Bortone & Polleux 2009, Hirai et al. 1999, Jansson et al. 2013, Métin et al. 2000, Soria & Valdeolmillos 2002 | |

| Hgf | HGF/SF (hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor) | Motogenic activity for interneuron migration | ✓ | Powell et al. 2001 | ||

| NRG1 | Neuregulin 1 | ErbB4 ligand, substrate-bound and secreted guidance cue for interneuron migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Anton et al. 1997, Flames et al. 2004, Li et al. 2012 |

| NTF4 | NTF4 (neurotrophin-4) | Stimulation of tangential migration of MGE-derived cells | ✓ | Polleux et al. 2002 | ||

| Ntn1 | Netrin 1 | Secreted guidance cue Orientation of the migration of cortical neurons and promotion of the transition from multipolar to bipolar morphology |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ju et al. 2013, Stanco et al. 2009 |

| Reln | Reelin | Extracellular matrix (ECM) protein released by Cajal-Retzius cells, VLDLR/ApoER2 ligand, regulates terminal phase of neuronal migration and placement | ✓ | Franco et al. 2011, Jossin & Cooper 2011, Ogawa et al. 1995 | ||

| Sema3A, Sema3F | Semaphorin 3A/3F | Neuropilin ligand, repulsive guidance cue | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Chen et al. 2008, Marín et al. 2001 |

| Sema4D | Semaphorin 4D | Plexin B1 ligand, promotes tangential and radial migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hirschberg et al. 2010 |

| Serotonin | Neurotransmitter, decreases interneuron migration | ✓ | Riccio et al. 2009 | |||

| Shh | Sonic hedgehog | Binds to Patched 1 receptor, releasing inhibition of Smoothened receptor Transition from tangential to radial migration of MGE-derived interneurons |

✓ | Baudoin et al. 2012 | ||

| Slit | Slit | Robo ligand, repulsive guidance cue | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Andrews et al. 2008, Zheng et al. 2012 |

| Sparcl1 | SPARCL1 (secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteines-like 1) or SC1 | Antiadhesive ECM protein, terminates radial glia–based migration through its antiadhesive properties | ✓ | Gongidi et al. 2004 | ||

| Receptors and membrane-bound proteins | ||||||

| Cacna | Voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel or VSCC (voltage-sensitive calcium channel) | Frequency of spontaneous intracellular calcium transients initiated by L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channel (VSCC) activation is decreased upon GABAA receptor activation during interneuron migration | ✓ | Bortone & Polleux 2009, Cross-Disord. Group Psychiatr. Genomics Consort. 2013, Komuro & Kumada 2009, Zheng & Poo 2007 | ||

| Cxcr4, Cxcr7 | CXCR4, CXCR7 (CXC chemokine receptor) | Receptor of CXCL12 or SDF-1, expressed by tangentially migrating interneurons | ✓ | Sánchez-Alcañiz et al. 2011, Stumm et al. 2003, Y. Wang et al. 2011 | ||

| Dcc | DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer) | Corrects the orientation of radially migrating projection neurons | ✓ | Ju et al. 2013, Yee et al. 1999 | ||

| Drd1 | Dopamine D1 receptor | Promotes interneuron migration | ✓ | Crandall et al. 2007 | ||

| Drd2 | Dopamine D2 receptor | Inhibits interneuron migration | ✓ | Crandall et al. 2007 | ||

| Efnb1 | Ephrin B1 | Ephrin ligand | ✓ | Stuckmann et al. 2001, Villar-Cerviño et al. 2013 | ||

| Egfr | EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) | Receptor for EGF, promotes radial migration | ✓ | Caric et al. 2001 | ||

| ErbB4 | ErbB-4 (v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4) | NRG1 receptor | ✓ | Anton et al. 2004, Flames et al. 2004 | ||

| Gabra1, Gabbr1, Gabrr1 | GABAA, GABAB, and GABAC receptors | Receptors for GABA, regulate tangential and radial migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Behar et al. 1996, Behar et al. 1998, Bolteus & Bordey 2004, Bortone & Polleux 2009, Cuzon et al. 2006, López-Bendito et al. 2003 |

| Gfra1 | GFRα-1 (GDNF family coreceptor α1) | GPI-anchored receptor: GDNF receptor | ✓ | Pozas & Ibanez 2005 | ||

| Gpr56 | GPR56 | Adhesion G-protein-coupled adhesion receptors, regulation of basal lamina and glial endfeet–pial membrane interactions | ✓ | Li et al. 2008 | ||

| Gria1, 2, 3, 4 | AMPA (α-amino-3- hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionic acid) receptor | Receptor for glutamate, regulates radial and tangential migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Bortone & Polleux 2009, Jansson et al. 2013, Métin et al. 2000 |

| Grin1, Grin2a,b,d | NMDA (N-methyl D-aspartate) receptor | Receptor for glutamate, regulates radial and tangential migrations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Behar et al. 1999, Bortone & Polleux 2009, Hirai et al. 1999, Soria & Valdeolmillos 2002 |

| Itga3, Itga5, Itgb1, Itgav | Integrin receptors | Modulates glial-guided locomotion and interneuron migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Anton et al. 1999, Belvindrah et al. 2007, Graus-Porta et al. 2001, McCarty et al. 2005, Schmid et al. 2004, Sekine et al. 2012, Stanco et al. 2009 |

| Lrp8 (ApoER2) | LRP8, low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 8 (ApoER2, apolipoprotein E receptor 2) | Reelin receptor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | D’Arcangelo et al. 1999, Hiesberger et al. 1999, Howell et al. 1999, Trommsdorff et al. 1999 |

| Met | MET | Receptor for HGF/SF | ✓ | Powell et al. 2001 | ||

| Notch1 | Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1 | Role in Reln regulation of neuronal migration | ✓ | Hashimoto-Torii et al. 2008 | ||

| Nrp1, Nrp2 | Neuropilin 1/2 | Semaphorin receptor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Chen et al. 2008, Marín et al. 2001 |

| Ntrk2 | TrkB | Receptor of BDNF and NT4, promotes tangential migration | ✓ | Polleux et al. 2002 | ||

| Plxnb1 | Plexin | Semaphorin receptor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hirschberg et al. 2010 |

| Ptch1 | Patched 1 | Shh receptor, releases inhibition of Smoothened receptor upon Shh binding | ✓ | Baudoin et al. 2012, Ruat et al. 2012 | ||

| Robo | Robo | Slit receptor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Andrews et al. 2006, Marín et al. 2003, Zheng et al. 2012 |

| Rtn4 | Reticulon-4 (Nogo-A) | Myelin-associated protein, required for tangential migration | ✓ | Mingorance-Le Meur et al. 2007 | ||

| Slc6a4 | 5-HTR6 | Serotonin transporter, decreases interneuron migration | ✓ | Riccio et al. 2009 | ||

| Smo | Smo (Smoothened) | G-protein-coupled receptor, translocates to primary cilia, mediates Shh signaling | ✓ | Baudoin et al. 2012 | ||

| Vldlr | VLDLR (very low density lipoprotein receptor) | Reelin receptor | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | D’Arcangelo et al. 1999, Hiesberger et al. 1999, Howell et al. 1999, Trommsdorff et al. 1999 |

| Adhesion molecules | ||||||

| Astn1, Astn2 | ASTN1 and ASTN2, Astrotactin | Adhesion glycoprotein, ASTN2 complexes with ASTN1 to regulate ASTN1 membrane targeting, allowing glial-guided locomotion | ✓ | Wilson et al. 2010, Zheng et al. 1996 | ||

| Cdh2 | N-Cadherin | Cell-adhesion molecule, membrane levels decreased by Reelin/Rap pathway during migration of multipolar neurons | ✓ | Imai et al. 2006, Jossin & Cooper 2011, Shikanai et al. 2011 | ||

| Cntn2 (or TAG-1) | Contactin-2 | Neural cell–adhesion molecule expressed by cortical axons, supports migration of early-born MGE interneurons | ✓ | McManus et al. 2004 | ||

| Cntnap2 | Contactin associated protein–like 2 | Cell-adhesion molecule, member of the neurexin family, role in neuron-glia interactions | ✓ | Peñagarikano et al. 2011 | ||

| Dscam | DSCAM (Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule homolog) | Cell-adhesion molecule from Ig superfamily, axon guidance and branching Expression repressed by the transcription factor Dlx1/2 |

✓ | Chédotal & Rijli 2009, Cobos et al. 2007 | ||

| Gja1, Gjb2 | Connexins 43, 26 | Mediates dynamic adhesive interactions between migrating neurons and radial glia | ✓ | Elias et al. 2007, 2010; Fushiki et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2012 | ||

| Mdga1 | MDGA1 (MAM domain–containing glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor 1) | IgCAM anchored to the extracellular surface of the cell membrane by a GPI-linkage, controls migration of superficial layer cortical neurons | ✓ | Takeuchi & O’Leary 2006 | ||

| Ncam1 | NCAM (neural cell-adhesion molecule 1) | Neural cell-adhesion molecule from Ig superfamily | ✓ | Battista & Rutishauser 2010 | ||

| Transcription factors | ||||||

| Arx | Aristaless-related homeobox | Upregulated by Dlx1/2, required for tangential migration of GABAergic neurons, targets the expression of guidance cues (Semaphorin 6, Slit2) | ✓ | Colasante et al. 2008, Friocourt & Parnavelas 2011, Marcorelles et al. 2010 | ||

| Ascl1 (Mash1) | Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 | Induction of the GABAergic phenotype, activates Dlx1/2 expression | ✓ | Fode et al. 2000, Letinic et al. 2002, Parras et al. 2002, Poitras et al. 2007 | ||

| Dlx1, Dlx2 | Distal-less homeobox | Necessary for interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex | ✓ | Anderson et al. 1997 | ||

| Ebf3 | Early B-cell factor 3 | Downregulated by Arx, enriched in interneuron transcriptome, potential candidate for the regulation of interneuron migration | ✓ | Friocourt & Parnavelas 2011, Fulp et al. 2008 | ||

| Foxg1 | FoxG1, Forkhead box protein G1 | Required for tangential migration of multipolar cells (pyramidal precursors) and their migration to the cortical plate | ✓ | Miyoshi & Fishell 2012 | ||

| Foxp2 | Forkhead box P2 | Repression of Foxp2 by miRNAs promotes radial neuronal migration | ✓ | Clovis et al. 2012 | ||

| Gbx1 | Gastrulation brain homeobox 1 | Upregulated by Arx, required for cortical interneuron migration | ✓ | Colombo et al. 2007 | ||

| Gsh2 | Gsh2 | Involved in the determination of pallium/subpallium border | ✓ | Corbin et al. 2003 | ||

| Klf4 | Krüppel-like factor 4 | Regulation of multipolar-to-bipolar transition of radially migrating neurons | ✓ | Qin & Zhang 2012 | ||

| Lhx6 | LIM/homeobox protein 6 | Upregulated by Nk2x-1, required for the normal pattern of tangential migration of GABAergic interneurons and for their correct distribution in the cortical layers | ✓ | Liodis et al. 2007 | ||

| Lmo1 | LIM domain only 1 | Downregulated by Arx, enriched in interneuron transcriptome, potential candidate for the regulation of interneuron migration | ✓ | Friocourt & Parnavelas 2011, Fulp et al. 2008 | ||

| Neurog2 | Neurogenin 2 | Controls radial migration through the regulation of Rho GTPase Rnd2 | ✓ | Heng et al. 2008, Pacary et al. 2011 | ||

| Nkx2-1 | NK2 homeobox 1 | Represses the expression of neuropilin 2 (semaphorin 3A/3F receptor) | ✓ | Nobrega-Pereira et al. 2008 | ||

| Nr2f1 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 (COUP transcription factor 1) | Regulates the expression of the cortical migration regulator Rho GTPase 2 Rnd2, modulating late-born neuron migration | ✓ | Alfano et al. 2011 | ||

| Pou3f2 (BRN-2), Pou3f3 (BRN-1) | POU domain, class 3, transcription factor 2 (or 3) | Regulation of the expression of the p35 and p39 regulatory subunits of Cdk5 in migrating cortical neurons, control of the initiation of radial migration | ✓ | McEvilly et al. 2002, Sugitani et al. 2002 | ||

| Rest | Repressor element 1–silencing transcription factor | Transcriptional repressor, regulates radial migration via its downstream target Dcx | ✓ | Mandel et al. 2011 | ||

| Satb2 | Special AT-rich sequence binding protein 2 | Required for layer-dependent control of migration | ✓ | Alcamo et al. 2008, Britanova et al. 2008, J. Zhang et al. 2012 | ||

| Scrt1, 2 | Scratch 1 and 2 | Neural-specific zinc-finger transcription factor, regulates radial migration during (a) the onset of migration by downregulating E-cadherin expression and (b) the multipolar phase by modulating transcriptional activation of Neurog2 | ✓ | Itoh et al. 2013, Paul et al. 2012 | ||

| Shox2 | Short stature homeobox 2 | Downregulated by Arx, potential candidate for the regulation of interneuron migration | ✓ | Fulp et al. 2008 | ||

| Sox5 | Sex determining region Y-box 5 | Regulates migration of deep-layer neurons | ✓ | Kwan et al. 2008, Lai et al. 2008 | ||

| Srf | SRF (serum response factor) | Controls expression of actin-regulating protein gelsolin | ✓ | Alberti et al. 2005 | ||

| Tbr1 | T-box brain factor 1 | Required for cortical neuronal positioning | ✓ | Han et al. 2011, Hevner et al. 2001, McKenna et al. 2011 | ||

| Zeb2 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (or Sip1) | Essential for cortical interneuron guidance by decreasing levels of the repulsive receptor Unc5b | ✓ | van den Berghe et al. 2013 | ||

| miRNAs and miRNA machinery | ||||||

| Dicer1 | DICER | RNase III ribonuclease that cleaves double-stranded miRNA precursors to produce mature miRNAs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | McLoughlin et al. 2012 |

| Mir9-1 | miR-9 | miRNA, regulates expression of FoxG1, Foxp2, and stathmin | ✓ | Clovis et al. 2012, Delaloy et al. 2010, Shibata et al. 2008 | ||

| Mir124a-1 | miR-124 | miRNA, regulates expression of neuropilin-1 in the growth cone | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Baudet et al. 2012 |

| Mir132 | miR-132 | miRNA, regulates expression of Foxp2 | ✓ | Clovis et al. 2012 | ||

| Intracellular signal transduction machinery | ||||||

| Acta1, Actb | Actin α1, Actin β | Cytoskeletal component | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Govek et al. 2011 |

| Akt | Akt | Mediates Reelin signaling, acts downstream of Dab-1 | ✓ | Jossin & Goffinet 2007 | ||

| Apc | APC | Regulates radial glia cell polarity and thus glial-guided migration | ✓ | Yokota et al. 2009 | ||

| Arfgef2 | BIG2 | Interacts with Filamin A, promotes radial migration | ✓ | J. Zhang et al. 2012 | ||

| Arl13b | Arl13b | Promotes tangential migration, regulates cilia dynamics during migration and ciliary localization of signaling receptors | ✓ | Higginbotham et al. 2012 | ||

| Cdc42 | Cdc42 | Rho GTPase necessary for growth cone extension | ✓ | Cappello et al. 2006, Etienne-Manneville & Hall 2001 | ||

| Cdk5 | Cdk5, Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | Neuron-specific serine/threonine kinase, regulates actin and microtubule dynamics | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Chae et al. 1997, Gilmore et al. 1998, Ko et al. 2001, Kwon & Tsai 1998, Ohshima et al. 1996, Rakić et al. 2009 |

| Cdk5r1 | p35 | Regulatory subunit 1 of Cdk5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Gupta et al. 2003; Hammond 2004, Ko et al. 2001, Kwon & Tsai 1998, Rakić et al. 2009 |

| Cdk5r2 | p39 | Regulatory subunit 2 of Cdk5 | ✓ | Humbert et al. 2000, Ko et al. 2001 | ||

| Cdkn1b | p27(Kip1) | Microtubule-associated protein, promotes tangential migration | ✓ | Godin et al. 2012 | ||

| Clip1 | CLIP170 | Microtubule plus tip protein, candidate role in linking microtubules to actin during cell motility | ✓ | Kholmanskikh et al. 2006 | ||

| Crk | Crk (CT10 Regulator of Kinase) | Adaptor protein, part of Reelin-signaling pathway | ✓ | Assadi et al. 2003, Ballif et al. 2003, Chen et al. 2004, Huang et al. 2004 | ||

| Ctnnb1 | β-Catenin | Protein associated with cadherins and involved in Wnt signaling pathway | ✓ | Fu et al. 2006, Valenta et al. 2012 | ||

| Ctnnd1 | p120 Catenin | Transport of N-cadherin containing vesicles to the membrane surface | ✓ | Chauvet et al. 2003 | ||

| Cul5 | Cullin-5 | E3 ubiquitin ligase component, forms complex with SOCS leading to degradation of Dab-1 | ✓ | Feng et al. 2007 | ||

| Dab1 | Dab-1 (Disabled-1) | Adaptor protein mediating Reelin signaling | ✓ | Franco et al. 2011 | ||

| Dclk | Doublecortin-like kinase | Microtubule-associated protein related to doublecortin, stabilization of microtubules and necessary for nucleokinesis | ✓ | Deuel et al. 2006, Friocourt et al. 2007, Koizumi et al. 2006, Marín et al. 2010, Shu et al. 2006 | ||

| Dcx | Doublecortin | Microtubule-associated protein, stabilizes microtubules and regulates nucleokinesis | ✓ | Deuel et al. 2006, Friocourt et al. 2007, Gleeson et al. 1999, Koizumi et al. 2006, Marín et al. 2010, Shu et al. 2006, Tanaka et al. 2004 | ||

| Diap1 | mDia1, diaphanous homolog 1 (Drosophila) | Formin family, actin-polymerization factor | ✓ | Shinohara et al. 2012 | ||

| Disc1 | Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 | Localized at the centrosome Necessary for microtubule dynamics |

✓ | Ishizuka et al. 2011; Kamiya et al. 2006, 2008 | ||

| Dmd | Dystrophin | Protein linking the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex to the actin cytoskeleton Promotes radial migration |

✓ | Pawlisz & Feng 2011 | ||

| Dpysl2 | CRMP2 (Collapsin response mediator protein 2) | Microtubule-associated protein promoting microtubule polymerization | ✓ | Sun et al. 2010 | ||

| Dync1h1, Dync1i1, Dynll1 | Dynein | Microtubule molecular motor, couples nucleus–centrosome | ✓ | Niethammer et al. 2000, Sasaki et al. 2000 | ||

| Dyx1c1 | Dyslexia susceptibility 1 candidate 1 | Regulation of primary cilium morphology and signaling, required for radial migration | ✓ | Hoh et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2006 | ||

| Efhc1 | EF-hand domain (C terminal) containing 1 | Microtubule-associated protein, localizes to the centrosome and mitotic spindle, required for tangential and radial migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | De Nijs et al. 2012 |

| Ena/Vasp | Ena/VASP | Actin-nucleation factor | ✓ | Goh et al. 2002 | ||

| Ezh2 | Ezh2, Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase | Repression of Netrin1 by counteraction of Shh pathway, promoting tangential migration of mouse precerebellar neurons | ✓ | Di Meglio et al. 2013 | ||

| Filip1 | FILIP1, Filamin A interacting protein | Interacts with Filamin A, promotes radial migration | ✓ | Nagano et al. 2004, Sato & Nagano 2005 | ||

| Flna | FLNA, Filamin A | Actin-binding protein determining cell morphology during migration | ✓ | Nagano et al. 2004, Sato & Nagano 2005, J. Zhang et al. 2012 | ||

| Fyn | Fyn | Tyrosine kinase Activation of Dab-1 | ✓ | Arnaud et al. 2003, Bock & Herz 2003 | ||

| Gsn | Gelsolin | Actin-severing protein | ✓ | Alberti et al. 2005 | ||

| Ift88 | Intraflagellar transport protein homolog 88 | Member of the tetratrico peptide repeat family, part of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) machinery Necessary for primary cilia–dependent tangential migration |

✓ | Baudoin et al. 2012 | ||

| Iqgap1 | IQGAP1 | Calcium-sensitive GTPase scaffolding protein, links CLIP170 to cortical actin cytoskeleton through Lis1 regulation | ✓ | Kholmanskikh et al. 2006 | ||

| Katna1 | Katanin p60 | Microtubule-severing protein recruited by Ndel1, necessary for radial migration | ✓ | Toyo-Oka et al. 2005 | ||

| Kif11 | Kinesin family member 11, kinesin-5 | Microtubule molecular motor regulating transport of short microtubules in neuronal processes | ✓ | Falnikar et al. 2011 | ||

| Kif3A | Kinesin family protein 3A | Microtubule molecular motor, necessary for primary cilia–dependent tangential migration | ✓ | Baudoin et al. 2012 | ||

| Map2 | MAP2 | Microtubule-associated protein regulating microtubule stabilization, expression of Map2 is repressed by Dlx1/2 | ✓ | Cobos et al. 2007 | ||

| Mapt | Tau | Microtubule-associated protein regulating microtubule stabilization, important for the maintenance of the neuronal process | ✓ | Cobos et al. 2007, Colasante et al. 2008 | ||

| Mark2 | MARK2 (Mammalian Par-1 ortholog) | Necessary for multipolar-to-bipolar transition of migrating projection neurons | ✓ | Sapir et al. 2008 | ||

| Myh2 | Myosin II | Generates actin contractility, necessary for growth cone migration, nucleokinesis, and trailing-process retraction | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Bellion et al. 2005; Solecki et al. 2004, 2009 |

| Nap1 | NCK-associated protein 1 (NCKAP1 or NAP1) | Part of the WAVE complex that regulates lamellipodia formation necessary for neurite extension | ✓ | Yokota et al. 2007 | ||

| Ndel1 | NUDEL | Interacting partner of Lis1, required for nucleokinesis | ✓ | Niethammer et al. 2000, Sasaki et al. 2000 | ||

| Nova2 | Neuro-oncological ventral antigen 2 | RNA-binding protein Modulates neuronal migration by regulating the alternative splicing of Dab1 |

✓ | Yano et al. 2010 | ||

| Pafah1b1/Lis1 | Platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase 1b, regulatory subunit 1, LIS1 | Noncatalytic alpha subunit of the intracellular Ib isoform of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase Interacts with microtubules, dynein, doublecortin, Ndel1 Necessary for nucleokinesis and subsequent neuronal migration |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | des Portes et al. 1998, Pilz et al. 1999, Sapir et al. 1997 |

| Pak3 | PAK3 | Repressed by Dlx1/2, promotes neurite extension, potential role in interneuron migration termination | ✓ | Cobos et al. 2007 | ||

| Pard6a | Par-6 | Member of cell polarity pathway Role in establishing and/or maintaining the direction of neuronal locomotion |

✓ | Solecki et al. 2004 | ||

| Pik3r3 | Pi3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) | Mediation of Reelin signaling downstream of Dab-1 | ✓ | Jossin & Goffinet 2007 | ||

| Pomt1, Pomt2 | POMT1, POMT2 |

O-Mannosyltransferase, mediates biosynthesis of O-mannosylglycans Deletion leads to overmigration of neocortical neurons |

✓ | Hu et al. 2011 | ||

| Ptk2 | FAK (Focal adhesion kinase) | Tyrosine kinase, substrate of Cdk5, involved in microtubule organization and nucleokinesis of radial migrating neurons | ✓ | Xie et al. 2003 | ||

| Rab5, Rab7, Rab11 | Rab5, Rab7, Rab11 | Rab GTPases, regulate N-cadherin endocytic pathway | ✓ | Kawauchi et al. 2010 | ||

| Rac1 | Rac1 | Rho GTPase, promotes radial and tangential migration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Minobe et al. 2009 |

| Rap1a | Rap1 | Small GTPase involved in the Reelin signaling pathway, regulates multipolar-to-bipolar transition and radial glia–independent somal translocation | ✓ | Franco et al. 2011, Gao & Godbout 2013, Jossin & Cooper 2011 | ||

| Rhoa | RhoA | Rho GTPase necessary for actin remodeling | ✓ | Govek et al. 2011 | ||

| Rnd2,3 | Rho GTPase 2,3 | Atypical Rho GTPase inhibiting RhoA activity | ✓ | Heng et al. 2008, Pacary et al. 2011 | ||

| Slc12a5 | KCC2 | Potassium-chloride cotransporter Promotes termination of interneuron migration |

✓ | Bortone & Polleux 2009 | ||

| Socs1 | SOCS (Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling) | Complexes with Cul5 to facilitate Dab-1 degradation | ✓ | Feng et al. 2007 | ||

| Src | Src | Tyrosine kinase activating Dab-1 | ✓ | Arnaud et al. 2003, Bock & Herz 2003 | ||

| Stk11 | LKB1 (Liver Kinase B1) | Serine-threonine kinase, regulates multipolar-to-bipolar transition | ✓ | Asada et al. 2007, Bony et al. 2013 | ||

| Stmn2 | Stathmin-2 (SCG10) | Microtubule-polymerization regulator | ✓ | Westerlund et al. 2011 | ||

| Tuba1a, Tubb2b, Tuba8 | Tubulin α1 A, Tubulin β2B, Tubulin β8 | Tubulin isotypes, necessary for microtubule formation | ✓ | Abdolahhi et al. 2009, Poirier et al. 2007, Jaglin et al. 2009 | ||

| Wasf1 | WAVE (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein family, verprolin-homologous protein) | Actin-nucleation protein | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Tahirovic et al. 2010 |

Figure 2.

Molecular control of neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Radially and tangentially migrating neurons are shown in pink and blue, respectively. Molecules known to regulate radial, tangential, or both modes of neuronal migration are indicated in pink, blue, and purple, respectively. Molecules regulating the switch from tangential to radial mode of migration of interneurons are indicated in orange. Regulators of multipolar-to-radial transition of projection neurons are indicated in green. Abbreviations: AM, adhesion molecules; C, connexins; CP, cortical plate; IZ, intermediate zone; MZ, marginal zone; SVZ, subventricular zone; VZ, ventricular zone.

Similar signaling mechanisms may operate during semaphorin-regulated cytoskeletal rearrangements in leading processes of neurons during neuronal migration. Class 3 semaphorins expressed by the striatal cells repel tangentially migrating interneurons away from the striatum and channel them into distinct paths leading to the neocortex (Marín et al. 2001). Semaphorins expressed by the CP prevent some of the incoming interneurons from entering the CP and guide them into the migrating streams in the lower IZ (Ito et al. 2008, Tamamaki et al. 2003). However, semaphorins can also serve as chemoattractants for both migrating neurons and developing axons (Chauvet et al. 2007, Raper 2000). For example, a semaphorin 3A gradient produced by the cortical layers serves as a chemoattractant for the neuropilin-expressing layer-II/III projection neurons and promotes their radial migration (Chen et al. 2008). Thus, semaphorins appear to serve as either repellents or attractants to coordinate the migration of projection neurons and interneurons into the developing cerebral wall.

Slit proteins are another class of chemorepulsive guidance molecules secreted from the VZ and SVZ of the GE (Andrews et al. 2007, Marillat et al. 2002, Yuan et al. 1999). Binding of Slit proteins to their corresponding receptors of the Robo family, expressed by interneurons, repels interneurons from the GE, thus initiating their migration toward the neocortex (Hu 1999, Wu et al. 1999). However, the role of Slit in mediating this process was brought into question when tangential migration was found to be unaffected in Slit1−/−/Slit2−/− double-mutant mice (Marín et al. 2003), which suggests that different ligands may mediate Robo signaling. Later studies discovered an increase in interneuron proliferation in Robo−/− mice as well as an increase in the length of the leading process and branching in a Slit-dependent manner (Andrews et al. 2008), which suggests that Slit/Robo signaling is indeed important for establishing correct morphology of the interneuron population. Recent data also suggest that a new member of the Robo family, Robo4, regulates radial migration, partly by suppressing the repulsive activity of Slit (Zheng et al. 2012).

Slit/Robo signaling affects the cytoskeleton in several different ways, most of which converge on the actin cytoskeleton. Slit binding to Robo promotes interaction between Robo and a GAP protein, srGAP (Wong et al. 2001). srGAP inactivates Rho GTPase Cdc42, preventing it from activating an actin-nucleating factor, N-WASP, and thus abolishing actin polymerization associated with Arp2/3 protein activity (Wong et al. 2001). Alternatively, Slit binding may regulate actin polymerization by decreasing WASP and Arp2/3 expression (Ning et al. 2011). In addition, Robo has been shown to form a complex with Abl tyrosine kinase, β-catenin, and N-cadherin. Abl-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin leads to its dissociation from the complex and its translocation into the nucleus, resulting in disrupted cell adhesion (Rhee et al. 2007). This Slit/Robo-mediated down-regulation of the N-cadherin-dependent adhesion may regulate extension/retraction of neuronal processes during migration (Wong et al. 2012).

Another, well-studied example of a guidance cue necessary for oriented neuronal migration is neuregulin 1 (Nrg1) growth factor, which binds to the ErbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases (Falls 2003, Rico & Marín 2011). One of the ErbB receptors, ErbB4, is expressed mainly by interneurons in the developing brain (Flames et al. 2004, Yau et al. 2003). Nrg1/ErbB4 signaling controls the initial exit of the MGE-derived interneurons through the permissive lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE) corridor and toward the dorsal cortex (Flames et al. 2004). Importantly, this corridor is formed by cells expressing high levels of the membrane-bound Nrg1 (an Nrg1-CRD isoform that possesses an extracellular, cysteine-rich domain) throughout the LGE, together with inhibitory striatal cells that secrete semaphorins (Flames et al. 2004). Secreted forms of Nrg1 (Nrg1-Ig type-I and -II isoforms that possess an immunoglobulin-like domain) expressed by the neocortex then act as long-range chemoattractants to promote interneuron movement into the dorsal cortex.

ErbB tyrosine kinase receptors can influence cell migration by modulating cell-adhesive properties via integrins, receptors of the extracellular matrix molecules. Nrg1 modulation of integrin-dependent adhesion has been shown to trigger the PI3K/AKT-signaling pathway (Kanakry et al. 2007). Integrins can also regulate Rho GTPase activity, thus linking Nrg1 signaling to the actin cytoskeleton in migrating neurons (Sparrow et al. 2012).

Another guidance cue that regulates both radial and tangential neuronal migration is netrin1. Netrin1 can bind to three different receptors, DCC, DSCAM, and Unc5 (Lai Wing Sun et al. 2011), and can serve as either a repellent or an attractant, depending on the receptor binding (Marín & Rubenstein 2003). Recent evidence suggests that DCC is involved in establishing correct orientation of the radially migrating projection neurons ( Ju et al. 2013), which points to a role of netrin1-mediated signaling in radial migration. Netrin1 has also been shown to localize along the migratory routes of interneurons, where it interacts with the α3β1 integrin expressed by the migrating interneurons to promote tangential migration (Stanco et al. 2009). At the mechanistic level, netrin1-mediated signaling likely affects both the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton, at least in part via CDK5- and GSK3β-dependent phosphorylation of MAP1B (Ayala et al. 2007).

Lastly, several lines of evidence suggest that classic neurotransmitters glutamate and GABA serve as extracellular cues to regulate both radial and tangential neuronal migration (Behar et al. 1996, 1998, 1999; Bolteus & Bordey 2004; Bony et al. 2013; Cuzon et al. 2006; Hirai et al. 1999; Jansson et al. 2013; López-Bendito et al. 2003). For example, GABA- or glutamate-mediated de-polarization of tangentially migrating interneurons induces intracellular calcium transients that stimulate interneuron motility (Bortone & Polleux 2009). Conversely, interneuron hyperpolarization mediated by upregulation of a potassium/chloride exchanger, KCC2, negatively regulates the frequency of intracellular calcium transients and stops interneuron migration (Bortone & Polleux 2009). Further, glutamate NMDA receptor/N-type calcium channel–mediated calcium dynamics have been shown to regulate saltatory patterns of radial migration (Komuro & Rakic 1993, 1996, 1998). These data suggest that regulation of calcium dynamics by neurotransmitter receptors is a common mechanism for different patterns of neuronal migration (Behar et al. 1996, Bortone & Polleux 2009, Komuro & Kumada 2005, Kumada & Komuro 2004, Zheng & Poo 2007).

Extracellular matrix and cell-surface guidance cue–activated pathways as models for integration of molecular networks underlying neuronal migration

Reelin, a large extra-cellular glycoprotein secreted by Cajal-Retzius (CR) cells in the MZ, affects two aspects of radial neuronal migration: the ability of migrating neurons to split the PP and the ability of radial glia–guided neurons to migrate past older neurons to generate the inside-out pattern of cortical layering (D’Arcangelo et al. 1995, Leemhuis & Bock 2011, Marín et al. 2010, Ogawa et al. 1995, Stranahan et al. 2013). Reelin binds to two lipoprotein receptors expressed on the migrating neurons and radial glia: very low density lipoprotein receptor (VLDR) and apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2) (D’Arcangelo et al. 1999). Reelin binding induces phosphorylation of the adaptor protein disabled-1 (Dab1) by protein kinases Src and Fyn (Bock & Herz 2003; Hiesberger et al. 1999; Howell et al. 1999, 2000; Kuo et al. 2005).

Phosphorylated Dab1 acts as a hub for binding of various interacting proteins that activate several signaling networks that control neuronal migration and positioning (Gao & Godbout 2013). Reelin may affect radial neuronal migration through the Dab1-Crk/CrkL-C3G-Rap1-N-cadherin signaling pathway in at least three different ways. Binding of Reelin to its receptors promotes Dab1-Crk interaction and C3G phosphorylation, resulting in activation of a Ras-related GTPase, Rap1 (Gao & Godbout 2013). Inhibition of Rap1 in migrating multipolar neurons results in loss of neuronal ability to migrate in a CP-oriented manner in response to Reelin ( Jossin & Cooper 2011). This effect is due to an increase in the level of cell-surface N-cadherin by active Rap1 ( Jossin & Cooper 2011). Additionally, cell-surface levels of N-cadherin are regulated by Rab GTPases—members of the endocytosis machinery—thus linking endocytosis to Reelin-mediated neuronal migration (Kawauchi et al. 2010). Additionally, the effect of Rap1/N-cadherin was abolished when migrating neurons assumed bipolar morphology, which suggests that the Reelin-Rap1 pathway does not regulate radial glia–dependent locomotion (Franco et al. 2011, Jossin & Cooper 2011).

Another line of evidence established a role for the Reelin/Dab1/Rap1 pathway in radial glia–independent somal translocation of both early- and late-born neurons (Franco et al. 2011). Dab1-deficient and Rap1-inactivated neurons failed to orient and attach their leading processes to the MZ, resulting in neuronal migration defects. These defects were rescued by overexpression of cadherins, which suggests that the Reelin/Dab1/Rap1/cadherin pathway stabilizes leading processes of migrating neurons and regulates their attachment to the MZ (Franco et al. 2011). In this context, Sekine et al. (2012) recently showed that the Reelin-Crk/CrkL-Dab1-Rap1 signaling pathway regulates terminal translocation by activating integrin α5β1 in the leading processes of migrating neurons. This activation promotes neuronal adhesion to fibronectin present in the MZ, which signals an end to translocation in the migrating neurons.

At the cytoskeletal level, Reelin signaling modulates both microtubule and actin dynamics. Dab1 phosphorylation is coupled to the PI3K/Akt/GSK3β pathway (Gao & Godbout 2013, Marín et al. 2010): Reelin-induced serine phosphorylation of GSK3β results in GSK3β inactivation and, as a result, hypophosphorylation of a microtubule-stabilizing protein, tau. However, Reelin-mediated phosphorylation of GSK3β on specific tyrosine residues results in GSK3β activation and phosphorylation of another microtubule-associated protein, MAP1B, which also regulates microtubule stability (Marín et al. 2010). The Reelin-PI3K-Akt pathway can also regulate the actin cytoskeleton by activating LIMK1, a Ser/Thr kinase that phosphorylates an actin-depolymerizing protein, n-cofilin, thus blocking its function (Chai et al. 2009). Inactivation of n-cofilin in the leading processes of migrating neurons may affect the stability of the processes as well as their attachment to the MZ (Chai et al. 2009, Gao & Godbout 2013). Together, these data suggest that integration of Reelin signaling regulates a diverse set of molecular networks, ultimately leading to appropriate migration and placement of neurons in the cerebral cortex.

Ephrins, a class of membrane-anchored (A-type) and transmembrane (B-type) guidance molecules, bind to Eph receptor tyrosine kinases (Rodger et al. 2012). Both Ephs and ephrins can serve as receptors or ligands (Davy & Soriano 2005, Pasquale 2008), leading to different signaling outcomes, including repulsion, attraction, or changes in motility (Himanen et al. 2007, Pitulescu & Adams 2010, Poliakov et al. 2004, Rodger et al. 2012). In the developing brain, Eph-ephrin signaling has been shown to regulate different aspects of both radial and tangential neuronal migration. Ephrin-Eph interactions mediate contact repulsion and cortical distribution of the CR cells, which regulate migration of projection neurons via release of Reelin (Villar-Cerviño et al. 2013). Further, transmembrane ephrin Bs associate with the Reelin receptors, VLDR and ApoER2, and bind Reelin. Clustering of ephrin Bs on the membrane recruits Dab1 and promotes its phosphorylation (Sentürk et al. 2011), and Reelin was recently shown to induce EphB activation (Bouché et al. 2013), suggesting that cross talk between the Eph-ephrin and Reelin signaling pathways may play a role in controlling radial neuronal migration. Additionally, Torii et al. (2009) showed that ephrin A–mediated forward signaling regulates lateral dispersion of radially migrating neurons during the multipolar stage of their migration, thus ensuring proper intermixing of neuronal types within the developing cortical columns.

Ephrins and Ephs regulate tangential migration mostly via their class-A proteins. For example, both early- and late-born interneurons express EphA4 receptor. Ephrin A3 is expressed in the striatum and repulses the early-born EphA4-expressing interneurons, restricting them from entering the striatum (Rudolph et al. 2010). Ephrin A5 is expressed in the VZ of the GE and repels EphA4-expressing, late-born interneurons from entering the VZ on their way to the cortex (Rodger et al. 2012, Zimmer et al. 2008). Together, ephrin A3– and A5–mediated signaling pathways create ventral (along the MZ and SP) and dorsal (along the lower IZ/SVZ) corridors for interneuronal migration, respectively (Rodger et al. 2012). Additionally, bidirectional signaling by ephrin B3-EphA4 segregates migrating interneurons into two migratory streams: Ephrin B3–expressing POA interneurons repel MGE-derived interneurons from the stream that migrates through the MZ via forward signaling, whereas EphA4-expressing MGE interneurons repel POA interneurons from the stream that migrates through the SVZ via reverse signaling (Zimmer et al. 2011). Two of the semaphorin receptors, neuropilin 1 and neuropilin 2, are also differentially expressed between these two migratory streams; neuropilin 1 is expressed on the MGE-derived interneurons, and neuropilin 2 is expressed on the POA interneurons (Zimmer et al. 2010, 2011). Together, these data suggest that integration between ephrin and semaphorin signaling pathways may create exclusion zones for migrating interneurons and help form corridors for streams of interneurons migrating into the cerebral cortex.

During this process, ephrin signaling may activate Rho GTPases directly (Noren & Pasquale 2004) or via Src-family kinases (Kullander & Klein 2002, Zimmer et al. 2007), resulting in rearrangements of the actin cytoskeleton (Carter et al. 2002). Ephrins have also been implicated in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion via their physical or functional interaction with integrins (Davy & Soriano 2005) and the MAPK pathway (Poliakov et al. 2004). In summary, guidance cues for oriented neuronal migration represent a diverse class of secreted or substrate-bound molecules that act as either chemotactic, chemoattractant, or chemorepellent guides. Common signaling pathways triggered by the guidance molecules result in coordinated cytoskeletal rearrangements that enable oriented neuronal migration and, thus, proper lamination of the cerebral cortex.

Mechanisms of Nucleokinesis and Patterns of Neuronal Migration

Nucleokinesis relies on extensive and rapid cytoskeletal rearrangements involving both micro-tubules and actin. During nucleokinesis, the centrosome and its accompanying organelles move into the swelling formed by the base of the leading process, followed by translocation of the nucleus and cell body (Trivedi & Solecki 2011). The centrosome is linked to a cage-like micro-tubule structure surrounding the nucleus, which is essential for forward nuclear movement (Tsai & Gleeson 2005, Xie et al. 2003).

Nuclear translocation is powered by dynein and dynein regulatory factors, such as Lissencephaly 1 (Lis1). Lis1 protein localizes to the centrosome and interacts with dynein via Ndel1; Ndel1 is also required for anchoring of microtubules at the centrosome (Guo et al. 2006, Li et al. 2005, Smith et al. 2000). Thus, the Lis1-Ndel1-dynein complex regulates nucleokinesis by promoting centrosome-nucleus coupling. Furthermore, a microtubule-associated protein, doublecortin (DCX), and its related protein, DCLK, may play a similar role in nucleokinesis (Deuel et al. 2006, Gleeson et al. 1999, Koizumi et al. 2006, Marín et al. 2010, Shu et al. 2006, Tanaka et al. 2004). In addition, a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK5) is known to phosphorylate both Ndel1 and DCX, suggesting that it plays a crucial role in regulating the microtubule cytoskeleton during nucleokinesis (Marín et al. 2010).

Several lines of evidence suggest that mechanisms of nucleokinesis may be different between radially and tangentially migrating neurons (Trivedi & Solecki 2011). In interneurons, the nucleus is tethered to the centrosome by the microtubules, and movement of the centrosome, along with the Golgi complex, to the swelling at the base of the leading process creates a pulling force for the nuclear movement (Bellion et al. 2005). This nuclear movement is also supported by the actomyosin contractions at the rear of the cell that push the nucleus forward (Bellion et al. 2005). However, nuclear movement in subsets of radially migrating, glial-guided neurons, such as cerebellar granule neurons, does not depend on centrosome positioning and is powered by a specific subset of acetylated microtubules that are not associated with the centrosome (Umeshima et al. 2007). In these neurons, the nucleus moves ahead of the centrosome in a dynein-powered process driven by the leading-process actomyosin contraction that pulls the nucleus forward (Solecki et al. 2009). These differences in the mechanisms of nucleokinesis employed by radially and tangentially migrating neurons may in part reflect the interactions with different adhesion molecules and subsequent selective cytoskeletal rearrangements during radial and tangential migration (Trivedi & Solecki 2011). Further, adhesion mechanisms have been shown to regulate both nuclear translocation and leading-process dynamics during radial migration (Elias et al. 2007). Connexins 26 and 43, both of which are gap junction subunits, promote adhesions between radial glial fibers and radially migrating neurons (Elias et al. 2007); connexin 26–mediated adhesion promotes nuclear translocation, whereas connexin 43–mediated adhesion regulates the stability of the leading-process branching (Elias et al. 2007). Considering that both connexins and other adhesion molecules interact with different components of the cytoskeleton, differences in the adhesion mechanisms between radially and tangentially migrating neurons may explain different mechanisms of nuclear translocation and leading-process dynamics evident in these neurons.

Trailing-Process Dynamics During Neuronal Migration

Formation and retraction of the trailing process are characteristic features of both interneuron and projection neuron migration. During neuronal migration, radially migrating neurons trail an extensive proto-axon from the cell, whereas interneurons in general display only a minor trailing process (Trivedi & Solecki 2011). These differences in trailing-process morphology may underlie the differences in translocation mechanisms used by these two groups of neurons. In tangentially migrating neurons, retraction of the trailing process is thought to depend on myosin II–mediated contraction at the neuron’s rear (Bellion et al. 2005, Schaar & McConnell 2005, Trivedi & Solecki 2011). This myosin-based retraction of the trailing process is thought to impel the interneuron forward. However, in radially migrating neurons, the concentration of myosin II motor is highest in the leading process, where it promotes centrosome translocation (He et al. 2010, Solecki et al. 2009, Trivedi & Solecki 2011). These differences in actomyosin localization and function, as related to trailing-process retraction, further highlight the distinguishing cellular mechanisms between the radial and tangential modes of migration.

PRIMARY CILIUM AS A SIGNALING CENTER DURING NEURONAL MIGRATION

The primary cilium, a microtubule-based sensory organelle, is a critical regulator of several signaling pathways (Han & Alvarez-Buylla 2010, Lee & Gleeson 2011, Louvi & Grove 2011). Primary cilia, found on cortical progenitor cells and developing neurons, are important for cortical morphogenesis (Arellano et al. 2012, Besse et al. 2011, Breunig et al. 2008, Willaredt et al. 2008, Wilson et al. 2012). Disrupted primary cilia functions may be responsible for cognitive defects and brain malformations in human ciliopathies (Han & Alvarez-Buylla 2010, Hildebrandt et al. 2011).

Recent studies have shown that primary cilia are essential regulators of interneuronal migration (Baudoin et al. 2012, Higginbotham et al. 2012). Interneuron-specific deletion of the cilia-specific Arl13b, a small GTPase of the Arf/Arl family, results in disrupted tangential migration (Higginbotham et al. 2012). Arl13b mutant interneurons are defective in their ability to respond to gradients of guidance cues from the dorsal cortex and have altered cAMP and Erk signaling (Higginbotham et al. 2012). The finding that Arl13b-related cilia defects do not affect radial migration suggests that cilium-mediated signaling may play a vital role in neuronal migration that depends on gradients of extrinsic guidance cues, as opposed to the substrate-guided mechanisms used by radially migrating neurons. High concentrations of signaling receptors in the primary cilium may enable it to act as a sensor of shallow gradients during oriented interneuronal migration. Further, a study by Baudoin and colleagues suggested that cilia-mediated Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling promotes tangential-to-radial transition of migrating interneurons, thus facilitating interneuronal colonization of the CP (Baudoin et al. 2012, Corbit et al. 2005). Together, these studies suggest that primary cilium–mediated signaling is instrumental in interneuronal navigation.

Although the mechanism via which ciliary proteins such as Arl13b may affect the neuronal cytoskeleton during migration is still unclear, the Arl proteins have been described as emerging regulators of microtubule dynamics (Kahn et al. 2005, Zhou et al. 2006). In Caenorhabditis elegans arl-13 mutants, effects of cilia disruption could be rescued by changing the acetylation state of the microtubules (Li et al. 2010, Loktev et al. 2008). It is tempting to speculate that similar mechanisms operate in interneuron cilia upon Shh or other guidance cue binding and promote oriented interneuronal migration by influencing microtubule dynamics. Consistently, Shh signaling–regulated tangential migration is accompanied by changes in microtubule organization and Golgi complex morphology (the latter relies on the microtubule cytoskeleton) (Baudoin et al. 2012).

Both primary cilia and growth cones sense and respond to extrinsic guidance cues and transduce signals that result in cytoskeletal rearrangements and oriented neuronal migration. Although several signaling receptors are shared between cilia and growth cones (Higginbotham et al. 2012), whether signaling emanating from these receptors in primary cilia and growth cones regulates distinct aspects of neuronal migratory behavior is currently unknown. Primary cilium’s proximity to the centrosome and nucleus may make it ideally positioned to promote nucleokinesis and neuron movement in response to appropriate guidance cues.

TRANSCRIPTIONAL, POSTTRANSCRIPTIONAL, AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF NEURONAL MIGRATION

Emerging data suggest that neuronal migration, positioning, and acquisition of correct neuronal identity are regulated by cell type– and layer-specific transcriptional programs in the developing neocortex (Kwan et al. 2012). Distinct transcriptional factors control migration of early- and late-born neurons, but several common principles govern this regulation. For example, transcription factors that are expressed by both early- and late-born projection neurons regulate neuronal migration in a neuronal type–specific manner. Sox5, specifically expressed in projection neurons destined for the SP and neocortical layers 5 and 6 (Kwan et al. 2008, Lai et al. 2008), is responsible for the correct migration of the deep-layer neurons past earlier-born neurons, but it does not affect migration of the late-born neurons. POU3F2 and -3, related transcription factors expressed by the late-born neurons, exhibit cell type–specific regulation of projection neurons destined to form layers 2–5 of the developing neocortex (Kwan et al. 2012). However, early neuron transcription factor TBR1 and late neuron transcription factor Satb2 regulate neuronal migration in a layer-specific manner (Alcamo et al. 2008, Bedogni et al. 2010, Britanova et al. 2008, Kwan et al. 2012). The downstream mechanisms of this transcriptional regulation have not yet been explored fully, but it is intriguing that POU3 transcription factors exhibit their regulatory effect via Cdk5 and Dab1, suggesting that migration-dependent transcriptional programs modulate intracellular signaling pathways known to be essential for oriented neuronal migration.

Importantly, distinct transcription factors have been shown to regulate radial and tangential migration. For example, transcription factors Dlx1/2 regulate interneuronal migration and tangential-to-radial migratory switches by affecting leading-process dynamics: Leading processes of the Dlx1/2−/− interneurons are longer and exhibit decreased branching (Anderson et al. 1997, 1999; Chédotal & Rijli 2009; Cobos et al. 2007). Another interneuron-specific transcription factor, Arx, which acts downstream of Dlx (Cobos et al. 2005, Colasante et al. 2008), controls tangential migration through a similar mechanism (Colombo et al. 2007). Importantly, expression of guidance cues and their receptors appears to be regulated by Arx as well as by other interneuron-specific transcription factors (Chédotal & Rijli 2009, Friocourt & Parnavelas 2011). For example, semaphorin 6 and Slit2 have been identified as potential Arx targets (Friocourt & Parnavelas 2011), whereas expression of the semaphorin 3A/3F receptor neuropilin 2 is controlled by transcription factors Nkx2-1 (Nóbrega-Pereira et al. 2008) and Dlx (Le et al. 2007). Interneurons are also enriched in the transcription factor Sip1, which, as van den Berghe et al. (2013) recently described, controls acquisition of proper interneuron identity as well as tangential migration.

During radial migration, transcription factor KLF4 (Krüppel-like factor 4) regulates multipolar-to-bipolar transition by affecting both leading and trailing processes (Qin & Zhang 2012). Paul et al. (2012) showed that transcription factor Scratch2 regulates radial migration during the multipolar phase as well. Recently, Miyoshi & Fishell (2012) showed that temporally regulated expression of transcription factor FoxG1 is required for the exit of projection neurons from the multipolar stage, as well as their migration to the CP. Additionally, Mandel et al. (2011) showed that the transcriptional repressor REST regulates radial migration, at least in part via its downstream target, Dcx. Together, these data suggest that combinations of projection neuron– and interneuron-specific transcription factors and repressors trigger signaling programs to facilitate appropriate patterns of neuronal migration.

Although the current evidence for posttranscriptional regulation of neuronal migration is limited, several recent studies highlight the importance of this process in neuronal migration. miRNAs, a class of small, noncoding RNAs that exhibit imperfect complementarity to their target mRNAs, regulate a multitude of transcripts by either promoting mRNA degradation or affecting mRNA translation (Bartel 2009). Temporal and spatial patterns of miRNA expression are important for brain development (Gao 2010, Krichevsky et al. 2003, Miska et al. 2004). The miRNA biogenesis pathway involves the activity of Dicer, an RNase III ribonuclease that cleaves miRNA precursors to produce mature miRNA duplexes. McLoughlin et al. (2012) showed that depleting Dicer from the neuronal progenitor cells disrupts progenitor localization in the VZ and SVZ and results in defective radial migration and an increase in the CR cells, suggesting that miRNAs control neuronal migration, and production of the CR cells, specifically. Furthermore, miR-9, one of the brain-specific miRNAs, negatively regulates expression of FoxG1, a transcription factor that regulates production and differentiation of the CR cells (Shibata et al. 2008). Delaloy et al. (2010) showed that miR-9 also regulates migration of the human neuronal progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that miR-9 may be an important regulator of neuronal migration. Importantly, stathmin, a known regulator of microtubule dynamics and radial migration (Westerlund et al. 2011), was identified as a miR-9 target (Delaloy et al. 2010), suggesting that miRNAs may partly control cytoskeletal rearrangements in neurons during neuronal migration.

Several miRNAs are known to regulate guidance cue–mediated signaling (e.g., ephrin and semaphorin signaling) (Baudet et al. 2012, Gao 2010). miRNAs may therefore regulate neuronal migration indirectly by regulating signaling pathways that drive migration. For example, miR-124, the most abundant miRNA in the mouse brain (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2002), regulates semaphorin 3A–mediated signaling by controlling the expression of neuropilin 1 in the growth cone (Baudet et al. 2012). Moreover, reciprocal regulation of miRNAs by transcription factors and repressors, and vice versa, constitutes yet another layer of regulation that may control neuronal migration. For example, repression of transcription factor Foxp2 by miR-9 and miR-132 has been shown to promote radial neuronal migration (Clovis et al. 2012), and transcriptional repressor REST, which has been implicated in radial migration, suppresses expression of miR-124 (Conaco et al. 2006). Thus, characteristic cell type–specific expression of many miRNAs, as well as their ability to target multiple transcripts, makes them attractive candidates as regulators of neuronal migration.