Abstract

Hypercapnia, an elevation of the level of carbon dioxide (CO2) in blood and tissues, is a marker of poor prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other pulmonary disorders. We previously reported that hypercapnia inhibits the expression of TNF and IL-6 and phagocytosis in macrophages in vitro. In the present study, we determined the effects of normoxic hypercapnia (10% CO2, 21% O2, and 69% N2) on outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in BALB/c mice and on pulmonary neutrophil function. We found that the mortality of P. aeruginosa pneumonia was increased in 10% CO2–exposed compared with air-exposed mice. Hypercapnia increased pneumonia mortality similarly in mice with acute and chronic respiratory acidosis, indicating an effect unrelated to the degree of acidosis. Exposure to 10% CO2 increased the burden of P. aeruginosa in the lungs, spleen, and liver, but did not alter lung injury attributable to pneumonia. Hypercapnia did not reduce pulmonary neutrophil recruitment during infection, but alveolar neutrophils from 10% CO2–exposed mice phagocytosed fewer bacteria and produced less H2O2 than neutrophils from air-exposed mice. Secretion of IL-6 and TNF in the lungs of 10% CO2–exposed mice was decreased 7 hours, but not 15 hours, after the onset of pneumonia, indicating that hypercapnia inhibited the early cytokine response to infection. The increase in pneumonia mortality caused by elevated CO2 was reversible when hypercapnic mice were returned to breathing air before or immediately after infection. These results suggest that hypercapnia may increase the susceptibility to and/or worsen the outcome of lung infections in patients with severe lung disease.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, pulmonary infection, reactive oxygen species, phagocytosis, inflammation

Clinical Relevance

Because patients with hypercapnia and severe lung disease are at high risk for infections, our data suggest that hypercapnia may contribute to poor clinical outcomes in such individuals. Our findings also raise the possibility that the practice of “permissive” hypercapnia during the mechanical ventilation of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome may exert adverse effects on host defense. These results together may influence how we treat patients with severe lung disease, and may offer therapeutic options to decrease pulmonary infections in a subset of patients.

Hypercapnia occurs in patients with severe acute and chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), currently the third leading cause of death in the United States (1). Individuals with COPD and other chronic respiratory disorders are also at risk for the development of acute respiratory failure, which may be accompanied by acute or acute-on-chronic hypercapnia. In addition, patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and status asthmaticus may develop hypercapnia.

Hypercapnia has long been recognized as a marker of poor prognosis in patients with COPD, among whom pulmonary infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality (2–6). Hypercapnia is also an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia and in patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation (7–10). Moreover, hypercapnic patients with acute respiratory failure can develop ventilator-associated pneumonia, which prolongs intensive care unit and hospital stays, and carries a mortality rate of 33–50% (11). On the other hand, in some studies, hypercapnia accompanying low tidal volume mechanical ventilation (“permissive hypercapnia”) has been associated with reduced mortality in patients with ARDS (12, 13).

In animal models, hypercapnia has been shown to attenuate the acute lung injury induced by endotoxin, mechanical ventilation with high tidal volumes, and ischemia–reperfusion (14–16). By contrast, studies on the effects of hypercapnia during bacterial pulmonary infection in rats have produced highly variable results (17–21). In those reports, lung injury parameters and bacterial burden, as assessed in anesthetized and mechanically ventilated animals after intratracheal inoculation with Escherichia coli, were variously unaffected, worsened, or attenuated by hypercapnia. Notably, none of these studies assessed the impact of hypercapnia on survival, lung histology, markers of inflammation, or the evolution of infection in the absence of mechanical ventilation.

The association of hypercapnia with adverse outcomes in patients with lung disease and the adverse effects of hypercapnia on E. coli–induced lung injury in some rat studies suggested that hypercapnia may exert deleterious effects on host defense in the lung. Consistent with this hypothesis, we (22) and others (23, 24) have shown that elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) inhibits macrophage synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines TNF and IL-6, which play critical roles in host defense (25–27). We reported that hypercapnia suppressed LPS-induced TNF and IL-6 expression in a concentration-dependent, rapid, and reversible manner, independent of extracellular or intracellular acidosis by mouse and human macrophages in vitro (22). We also showed that elevated CO2 inhibited phagocytosis by macrophages (22).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of normoxic hypercapnia on antimicrobial host defense in vivo, using a model of pneumonia caused by the Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa in spontaneously breathing mice. We observed that hypercapnia worsened pneumonia mortality, increased the burden of P. aeruginosa in the lungs and other organs, decreased lung levels of IL-6 and TNF during the early phase of infection, and inhibited the phagocytosis of bacteria and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by lung neutrophils. These results indicate that hypercapnia suppresses the host immune mechanisms required for defense against bacterial pneumonia.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Six- to 10-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used for all pneumonia experiments. Experiments were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwestern University, and according to National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of rodents. For additional details, see the online supplement.

Murine CO2 Exposure

Mice were exposed to normoxic hypercapnia (10% CO2, 21% O2, and 69% N2) in a BioSpherix A environmental chamber (BioSpherix, Lacona, NY). O2 and CO2 concentrations in the chamber were maintained at the indicated levels using ProOx C21 O2 and CO2 controllers (BioSpherix). Age-matched mice, simultaneously maintained in air, served as controls in all experiments. For additional details, see the online supplement.

Arterial Blood Gases

Arterial blood gases (ABGs) were obtained from unanesthetized, restrained mice with surgically implanted carotid artery catheters. Mice were allowed to adapt for 1 to 2 days after shipping before being placed in the hypercapnia chamber and before any ABGs were drawn. Arterial blood was analyzed for pH, PaCO2, PaO2, and HCO3−, using a pHOx Plus Blood Gas Analyzer (Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA) that was calibrated daily.

Mouse Pneumonia Model

The nasal aspiration mouse model of acute pneumonia was used, as previously described (28) and as detailed further in the online supplement. Briefly, P. aeruginosa strain PA103 was grown to log phase and diluted to OD600 0.002 (1.0–1.8 × 106 CFU/ml). Mice pre-exposed to 10% CO2 before infection were removed from the hypercapnia chamber for bacterial inoculation, which was performed in air. Mice were lightly anesthetized, and then inoculated with 50 μl of bacterial suspension (5–9 × 104 CFU) via the nares.

After inoculation, mice were allowed to recover fully from anesthesia, and were then returned to the 10% CO2 exposure chamber or maintained in air, according to the protocol for each experiment. To assess survival, mice were monitored at least every 8 hours for 96 hours after infection. Any mouse exhibiting markers of severe illness, including ruffled fur, markedly decreased activity, and a decrease in respiratory rate to less than 70 breaths/minute, was killed and scored as dead (29).

Mice were killed 7 or 15 hours after inoculation (before pneumonia deaths in any experimental group) for the determination of cell counts in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), for the determination of bacterial CFUs in individual organs, or to obtain lungs for histologic examination. Additional details are provided in the online supplement.

Phagocytosis

The phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by alveolar neutrophils from infected mice was assessed as described previously (30), and as detailed further in the online supplement.

Statistical Methods

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed with Prism version 5 for Mac OSX (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Kaplan-Meier survival plots and the log-rank test were used to assess differences in survival between groups. The Mann-Whitney U test, an unpaired Student t test, or two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post hoc test were used, as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of Hypercapnia on Uninfected Mice

Before evaluating the impact of hypercapnia on murine pneumonia, we determined the effects of exposure to elevated CO2 on uninfected mice. Mice were exposed to normoxic hypercapnia (10% CO2, 21% O2, and 69% N2) or air for 2 weeks. In the absence of infection, exposure to 10% CO2 caused no obvious signs of distress and no overt changes in the animals’ appearance, in comparison with air-exposed control mice. Mice exposed to 10% CO2 gained weight during the 2-week exposure at a rate that was not significantly different from that of animals maintained in air (data not shown).

Because we were interested in the effects of hypercapnia on pulmonary infection, distinct from the effects of acidosis, we exposed mice to hypercapnia for up to 7 days to determine the time required to achieve renal compensation for respiratory acidosis. In these experiments, mice with preimplanted carotid artery catheters were used. Arterial blood was obtained from the animals using a restraint device without anesthesia to avoid depression of respiratory drive and alterations of PaCO2 and blood pH. Table 1 lists the ABG values for mice breathing air or 10% CO2 for 2 hours, 3 days, and 5 days. As shown, exposure to 10% CO2 caused the PaCO2 to more than double within 2 hours, and this increase was sustained without change at 3 days. At 2 hours, the increase in PaCO2 was accompanied by acute respiratory acidosis, with a decline in arterial pH to 7.15. Subsequently, after exposure to normoxic hypercapnia for 3 days, the arterial pH increased to 7.28 (the result of an increase in serum HCO3− to 38 mEq/L), reflecting renal compensation for the respiratory acidosis. The pH, PaCO2, and PaO2 values obtained after exposure to 10% CO2 for 5 days (Table 1) and 7 days (data not shown) were nearly identical to the values obtained at 3 days, indicating that exposure to hypercapnia for 3 days was sufficient to achieve maximal renal compensation. Also of importance, the PaO2 of mice exposed to hypercapnia was actually greater at all times than that of air-breathing animals (Table 1), indicating that in the absence of infection, exposure to 10% CO2 did not interfere with oxygenation.

TABLE 1.

ARTERIAL BLOOD GASES IN MICE BREATHING AIR OR 10% CO2 FOR VARIOUS TIMES

| Condition | pH | PaCO2 (mm Hg) | PaO2 (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air | 7.45 | 32 | 94 |

| 10% CO2, 2 h | 7.15 | 74 | 109 |

| 10% CO2, 3 d | 7.28 | 75 | 105 |

| 10% CO2, 5 d | 7.28 | 77 | 117 |

Hypercapnia Increases the Mortality of Pseudomonas Pneumonia

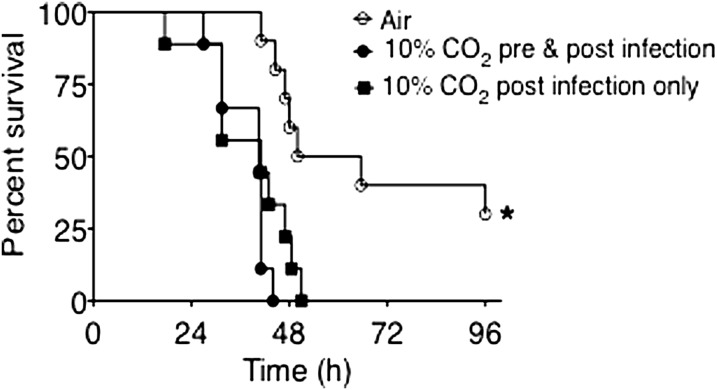

Having established the time required to achieve maximal renal compensation for respiratory acidosis in mice breathing 10% CO2, for our initial pneumonia experiments, we pre-exposed one group of mice to hypercapnia for 3 days before inoculation, to minimize the potential contribution of acidosis, as opposed to hypercapnia per se, on the outcomes of infection. We also assessed the impact of hypercapnia on pneumonia in a group exposed to 10% CO2 only after bacterial inoculation, such that infection would evolve at the lower pH associated with acute respiratory acidosis. As shown in Figure 1, air-exposed animals infected with P. aeruginosa experienced 50% mortality at 48 hours and 70% mortality at 96 hours. All mice surviving to 96 hours recovered from the infection. In contrast, both groups of mice exposed to 10% CO2 and infected with P. aeruginosa experienced 100% mortality by approximately 48 hours. The fact that mice with chronic respiratory acidosis, whose arterial pH before infection was approximately 7.28 (see Table 1), died at a rate similar to that of mice with acute respiratory acidosis and an arterial pH at the onset of infection of approximately 7.15 (Table 1), indicates that the degree of acidemia was not a key determinant of mortality in the hypercapnic animals.

Figure 1.

Elevated CO2 increases mortality from Pseudomonas pneumonia. BALB/c mice pre-exposed to normoxic hypercapnia (10% CO2, 21% O2, and 69% N2) or air for 3 days were infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7 × 104 CFU/mouse) at time zero, then maintained in hypercapnia or air, respectively, and monitored for survival for 96 hours (n = 10 mice per group; *P < 0.0005, air versus 10% CO2).

Because hypercapnia similarly increased and accelerated mortality, regardless of whether respiratory acidosis was acute or chronic, in all subsequent experiments mice were pre-exposed to 10% CO2 for 3 days before infection, to minimize the influence of acidemia on the results.

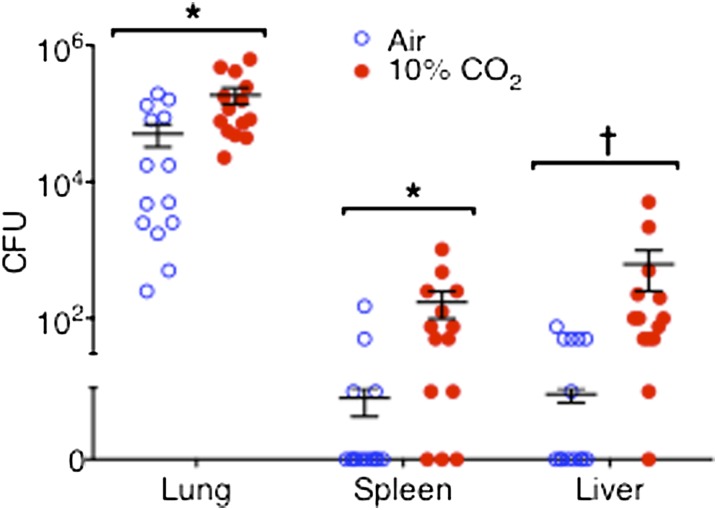

Hypercapnia Increases Bacterial Loads in the Lungs and Other Organs

Figure 2 illustrates the numbers of viable bacteria recovered from the lungs, spleens, and livers of air-exposed and 10% CO2–exposed mice, 15 hours after inoculation with P. aeruginosa. On average, the amount of viable P. aeruginosa recovered from the lungs of air-exposed animals was similar to the amount of bacteria in the initial inoculum, indicating a balance between bacterial proliferation and bacterial killing in the lungs during the first 15 hours of infection. By contrast, the number of viable bacteria recovered from the lungs of 10% CO2–exposed mice increased by 15 hours to a level fourfold greater than that in air-exposed animals. No viable P. aeruginosa were recovered from the spleens and livers of most air-exposed mice, and only low numbers of bacteria were recovered from the rest. On the other hand, significantly larger numbers of viable bacteria were recovered from the spleens and livers of the majority of 10% CO2–exposed mice. These data strongly suggest that hypercapnia impairs the host mechanisms needed to control P. aeruginosa growth in the lung and its dissemination to other organs. We also considered the possibility that hypercapnia may exert an independent effect on P. aeruginosa that would accelerate bacterial growth. To evaluate this, we determined the rate of growth for P. aeruginosa in broth equilibrated with 5% and 10% CO2, which yielded Pco2 in media closely approximating the PaCO2 of mice breathing air and 10% CO2, respectively (Table 1). Hypercapnia tended to slow the growth of P. aeruginosa in vitro, rather than increasing it (Figure E1 in the online supplement). Thus, the greater numbers of P. aeruginosa CFUs in the lungs and other organs of hypercapnic mice likely resulted from an effect of elevated CO2 on the host, rather than on the infecting bacteria.

Figure 2.

Hypercapnia increases P. aeruginosa burden in the lungs, spleen, and liver. BALB/c mice pre-exposed to normoxic hypercapnia or air for 3 days were infected with P. aeruginosa, and then maintained in hypercapnia or air, respectively. Animals were killed 15 hours after infection, and their lungs, spleens, and livers were processed for determination of bacterial CFU (n = 14 mice per group; *P < 0.008 and †P < 0.0007, air versus 10% CO2).

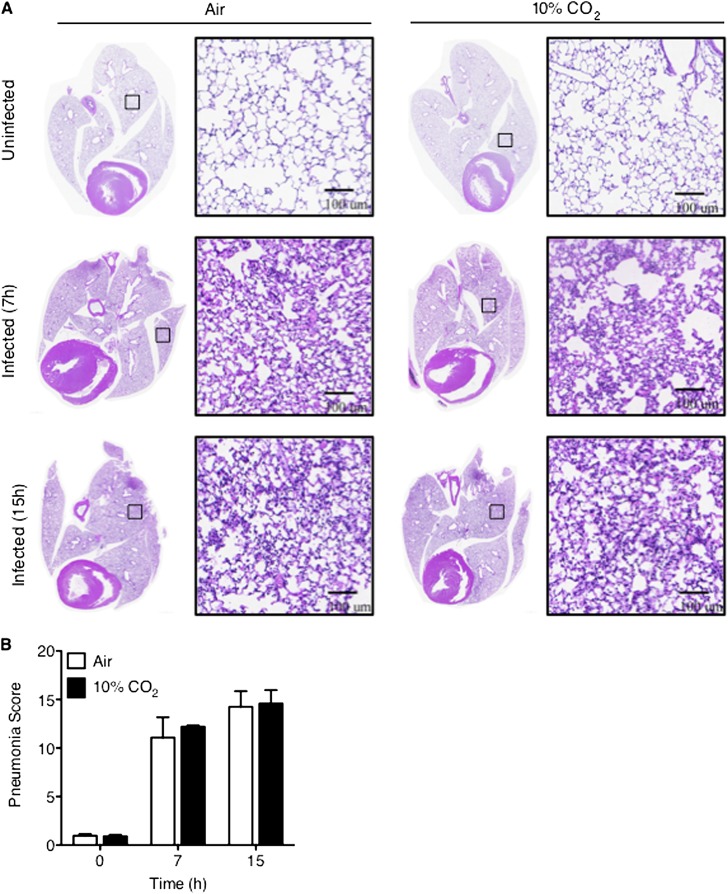

Hypercapnia Does Not Alter Histologic Lung Injury Associated with Pseudomonas Pneumonia

In the absence of infection, the lungs of mice exposed to 10% CO2 for 3 days were grossly normal when excised postmortem, and also appeared normal by light microscopy (Figure 3A, top). The absence of visible histologic abnormalities in the lungs correlated with the supranormal PaO2 observed in uninfected hypercapnic mice (Table 1). By contrast, the lungs of both air-exposed and 10% CO2–exposed mice inoculated intranasally with P. aeruginosa were grossly hemorrhagic at the time of killing, 7 and 15 hours after infection, without an obvious difference between the two groups (data not shown). Microscopically, interstitial and alveolar edema, hemorrhage, and the infiltration of inflammatory cells were evident in lungs from animals exposed to both air and 10% CO2 at 7 and 15 hours after infection (Figure 3A, middle and bottom). Using a validated system for scoring the histologic severity of pneumonia in rodents (31), we found no differences in the degree of lung inflammation and injury resulting from Pseudomonas infection in mice exposed to air or 10% CO2 at either time point (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Hypercapnia does not worsen the histologic lung injury associated with Pseudomonas pneumonia. BALB/c mice pre-exposed to normoxic hypercapnia or air for 3 days were infected with P. aeruginosa, and then maintained in hypercapnia or air, respectively. Seven and fifteen hours after infection, the mice were killed, and their lungs were excised, inflated, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and processed for histology. (A) Hematoxylin-and-eosin–stained lung sections were imaged and stitched into high-resolution digital montages, using the TissueGnostics System (TissueGnostics USA Ltd, Tarzana, CA) (original magnification, ×200). Boxes within low magnification whole-lung images indicate the area of lung shown at higher magnification immediately to the right. Images are representative of five animals per condition. (B) Total pneumonia scores before and 7 and 15 hours after infection, as determined according to Cimolai and colleagues (31) (n = 5).

Hypercapnia Impairs Lung Neutrophil Function in Pseudomonas Pneumonia

Given that neutrophils are critical for host defense in Pseudomonas pneumonia (30, 32–34), we determined the effects of hypercapnia on alveolar neutrophil recruitment after P. aeruginosa infection. Notably, in uninfected mice, exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days did not alter the number or profile of cells obtained from the lungs by BAL (Table 2), consistent with the absence of histologic inflammation observed under these conditions (Figure 3A, top). In air-exposed mice infected with P. aeruginosa, dramatic increases were evident in the numbers of inflammatory cells in BAL fluid, of which neutrophils comprised the vast majority at both 7 and 15 hours (Table 2). A similar increase in BAL neutrophils occurred in 10% CO2–exposed mice after infection, indicating that the failure to clear bacteria from the lungs and the increased mortality of Pseudomonas pneumonia caused by hypercapnia were not attributable to impaired recruitment of neutrophils.

TABLE 2.

DIFFERENTIAL BAL FLUID CELL COUNTS FROM UNINFECTED AND Pseudomonas aeruginosa–INFECTED MICE EXPOSED TO AIR OR 10% CO2

| Uninfected |

P. aeruginosa–Infected (7 h) |

P. aeruginosa–Infected (15 h) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air-Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 104 (%) | 10% CO2–Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 104 (%) | P | Air-Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 106 (%) | 10% CO2–Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 106 (%) | P | Air-Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 106 (%) | 10% CO2–Exposed (n = 5) Cells × 106 (%) | P | |

| Total | 14.0 ± 4.0 | 32.9 ± 12.0 | n.s. | 4.6 ± 2.6 | 13.1 ± 5.6 | n.s. | 26.4 ± 9.0 | 19.9 ± 3.1 | n.s. |

| PMNs | 0.7 ± 0.5 (4.0) | 0.3 ± 0.2 (0.8) | n.s. | 4.3 ± 2.5 (89.1) | 12.2 ± 5.3 (92.4) | n.s. | 25.3 ± 8.3 (96.3) | 19.0 ± 2.9 (95.3) | n.s. |

| Macro | 13.9 ± 3.0 (94.6) | 31.3 ± 1.1 (96.3) | n.s. | 0.3 ± 0.09 (9.7) | 0.2 ± 0.08 (2.7) | n.s. | 0.7 ± 0.4 (2.2) | 0.4 ± 0.4 (2.0) | n.s. |

| Lymph | 0.1 ± 0.03 (1.2) | 1.2 ± 0.7 (2.9) | n.s. | 0.009 ± 0.004 (0.4) | 0.5 ± 0.4 (3.3) | n.s. | 0.7 ± 0.4 (1.5) | 0.4 ± 0.09 (2.7) | n.s. |

| Eos | 0.0002 ± 0.0005 (0.2) | ND | n.s. | 0.01 ± 0.02 (0.8) | ND | n.s. | ND | ND | n.s. |

Definition of abbreviations: BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; Eos, eosinophils; Lymph, lymphocytes; Macro, macrophages; ND, not detected; n.s., not significant; PMNs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

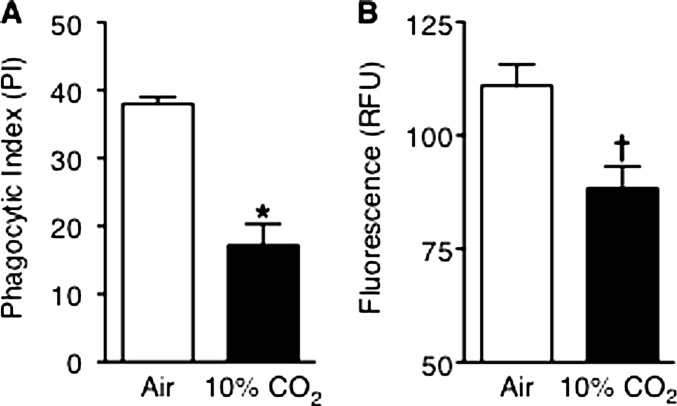

The similar numbers of neutrophils recruited to the lungs in 10% CO2–exposed and air-exposed mice at 15 hours suggested that leukocyte viability or function may have been impaired in hypercapnic mice with pneumonia. We thus performed flow cytometry on annexin V–stained BAL cells, which showed that in both air-exposed and 10% CO2–exposed mice, 98% of BAL neutrophils were viable, and only 2% were apoptotic or necrotic. We next assessed bacterial phagocytosis and H2O2 generation, key effector functions required for bacterial killing, in BAL neutrophils. Phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa in vivo, assessed microscopically in stained BAL cells, was significantly reduced in neutrophils from 10% CO2–exposed mice compared with air-exposed mice 15 hours after infection (Figure 4A). Likewise, when stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) ex vivo, BAL neutrophils from infected hypercapnic mice generated significantly less H2O2 than did neutrophils from air-exposed infected mice (Figure 4B). Similarly, during in vitro experiments, hypercapnia inhibited phagocytosis of E. coli BioParticles (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY; see Figure E2) and PMA-stimulated and opsonized zymosan–stimulated H2O2 production (Figure E3) by differentiated HL-60 cells.

Figure 4.

Hypercapnia impairs alveolar neutrophil function. BALB/c mice pre-exposed to normoxic hypercapnia or air for 3 days were infected with P. aeruginosa, and then maintained in hypercapnia or air, respectively. Animals were killed 15 hours after infection, and their lungs were lavaged. (A) BAL cells were cytocentrifuged and stained, and intracellular bacteria were counted in 200 neutrophils per animal (n = 7 mice per group; *P = 0.003, air versus 10% CO2). (B) Immediately after lavage, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) neutrophils were resuspended in Krebs Ringer's Phosphate Glucose (KRPG) buffer and stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (50 μM) for 5 minutes in 5% CO2/95% air at 37°C. H2O2 release was determined by the Amplex Red assay (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY) (n = 3 mice per group; †P = 0.03, air versus 10% CO2). RFU, relative fluorescence units.

Hypercapnia Reduces Early Expression of IL-6 and TNF in Pseudomonas Pneumonia

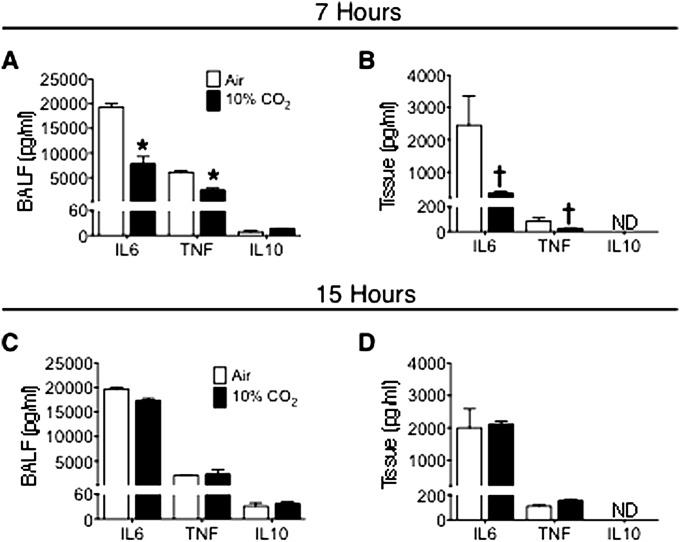

As noted, we previously reported that hypercapnia inhibited expression of IL-6 and TNF by human and mouse macrophages stimulated with LPS in vitro (22). Because IL-6 and TNF have been shown to enhance bacterial phagocytosis and ROS generation by neutrophils (25), we determined whether impaired lung neutrophil function in 10% CO2–exposed mice with Pseudomonas pneumonia was accompanied by reductions in IL-6 or TNF secretion in the lung. We found that BAL fluid and lung-tissue levels of IL-6 and TNF were reduced 7 hours after infection in mice exposed to 10% CO2, compared with air-exposed control mice (Figures 5A and 5B). On the other hand, 15 hours after infection, there was no longer any difference between IL-6 and TNF levels in BAL fluid or lung tissue from 10% CO2–exposed and air-exposed mice (Figures 5C and 5D). In contrast, BAL levels of the neutrophil chemoattractants chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1) and CXCL2, increased similarly 7 and 15 hours after infection in air-exposed and 10% CO2–exposed animals (Figure E4). The lack of difference in these chemokine levels between the two groups is consistent with the observation that hypercapnia exerted no effect on lung neutrophil influx after Pseudomonas infection (Table 2). Of note, the anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, which was expressed at much lower levels than IL-6, TNF, and the chemokines, was not decreased in BAL fluid or lung tissue of mice exposed to 10% CO2 at either 7 or 15 hours (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hypercapnia suppresses IL-6 and TNF levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) 7 hours after Pseudomonas infection. BALB/c mice pre-exposed to normoxic hypercapnia or air for 3 days were infected with P. aeruginosa, and then maintained in hypercapnia or air, respectively. Cytokine levels in BALF and lung-tissue homogenates obtained 7 hours (A and B) and 15 hours (C and D) after infection were determined using the Luminex Multianalyte assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Data represent the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples from each of two animals (*P < 0.0001 and †P < 0.01, air versus 10% CO2. ND, not detected.

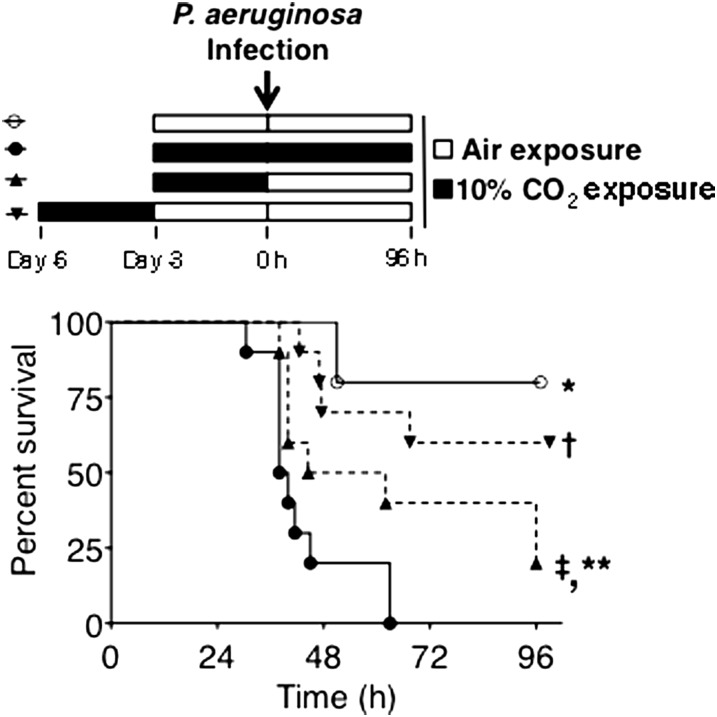

The Effect of Hypercapnia on Mortality Is Reversible

Along with our previous work demonstrating the reversibility of hypercapnia suppression of macrophage IL-6 expression (22), our observation that hypercapnia inhibited bacterial phagocytosis and H2O2 production by lung neutrophils without affecting cell viability suggested that the CO2-induced defects in neutrophil antimicrobial function might be reversible. This raised the possibility that the increase in pneumonia mortality caused by hypercapnia might also be reversible. To test this, we assessed the mortality of P. aeruginosa pneumonia in mice exposed to air only, or to 10% CO2, according to three different protocols: (1) exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days before and after inoculation; (2) exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days, and then infection, followed by exposure to air; and (3) exposure to 10% CO2, followed by exposure to air for 3 days, and then infection and continued exposure to air. As shown in Figure 6, the majority of mice exposed to air survived, whereas 100% of the mice exposed to 10% CO2 before and after inoculation died (similar to the results in Figure 1). On the other hand, pneumonia mortality was reduced to 80% in the group exposed to CO2 for 3 days until just before infection and then maintained in air, whereas pneumonia mortality decreased to 40% in the group exposed to CO2 for 3 days, followed by recovery in air before infection and continued air exposure. These results demonstrate that the hypercapnia-induced defect in host defense and the increase in pneumonia mortality are reversible when CO2-exposed mice are returned to breathing air before or at the onset of P. aeruginosa infection.

Figure 6.

The effect of hypercapnia on Pseudomonas pneumonia mortality is reversible. BALB/c mice were exposed to room air only and infected with P. aeruginosa ( ), or exposed to normoxic hypercapnia and infected with P. aeruginosa, involving exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days before and after inoculation (

), or exposed to normoxic hypercapnia and infected with P. aeruginosa, involving exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days before and after inoculation ( ); exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days, and then inoculation, followed by exposure to air (

); exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days, and then inoculation, followed by exposure to air ( ); or exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days, followed by exposure to air for 3 days, and then inoculation and further exposure to air (

); or exposure to 10% CO2 for 3 days, followed by exposure to air for 3 days, and then inoculation and further exposure to air ( ). Mice were monitored for survival for 96 hours after infection (n = 10 mice per group; *P < 0.0001,

). Mice were monitored for survival for 96 hours after infection (n = 10 mice per group; *P < 0.0001,  versus

versus  ; †P = 0.001,

; †P = 0.001,  versus

versus  ; ‡P = 0.007,

; ‡P = 0.007,  versus

versus  ; **P = 0.04,

; **P = 0.04,  versus

versus  .)

.)

Discussion

Hypercapnia is common in severe acute and chronic lung diseases. In observational clinical and epidemiologic studies, hypercapnia has been associated with increased mortality in COPD, cystic fibrosis, and community-acquired pneumonia (2, 7, 10). These reports do not make clear, however, whether patients with hypercapnia are at increased risk of death simply because they have advanced lung disease, or whether a causal link may exist between elevated CO2 and poor clinical outcomes. Our previous report that hypercapnia inhibited macrophage phagocytosis and the expression of cytokines TNF and IL-6 (22) suggested that hypercapnia may in fact reduce resistance to infection and thereby contribute to poor clinical outcomes.

We examined the effects of hypercapnia on host defense in vivo, using a well-established murine model of pneumonia caused by the gram-negative bacterium P. aeruginosa (28). P. aeruginosa is a leading cause of nosocomial pneumonia (35), and has emerged as an important cause of lung infections and mortality in patients with advanced COPD (36–38). In addition, P. aeruginosa is the most common cause of respiratory infection in adults with cystic fibrosis, and a common pathogen in other forms of bronchiectasis (39, 40).

To induce hypercapnia, we exposed mice to a normoxic hypercapnic gas mixture, consisting of 10% CO2, 21% O2, and 69%N2. Exposure to elevated CO2 at this level resulted in stable hypercapnia with a PaCO2 of approximately 75 mm Hg, that is, approximately twice the PaCO2 of air-breathing control mice (Table 1). This degree of hypercapnia is commonly encountered in patients with severe or exacerbated COPD (41), and is also seen in patients with acute respiratory failure (42). Interestingly, in the absence of infection, mice tolerated breathing 10% CO2 for at least 2 weeks, without obvious signs of ill health. Also of note, 10% CO2–exposed mice exhibited a higher PaO2 than air-breathing control mice at all times assessed (Table 1), ruling out hypoxia as a factor accounting for the altered response to infection in CO2-exposed mice.

Our study has led to the central finding that hypercapnia increased mortality in a clinically relevant model of acute pulmonary infection with Pseudomonas in spontaneously breathing mice. Moreover, mice exposed to elevated CO2 for 3 days, resulting in chronic respiratory acidosis with renal compensation (pH, ∼ 7.28), died of Pseudomonas pneumonia in a timeframe similar to that of mice with acute respiratory acidosis (pH, ∼ 7.15). Thus the degree of acidosis did not correlate with the rate at which hypercapnic mice died of P. aeruginosa infection, suggesting that elevated CO2 interferes with host defense by mechanisms that are not simply a function of low pH. This is consistent with our earlier in vitro finding that hypercapnia inhibited IL-6 expression, independently of both extracellular and intracellular acidosis (22).

Neutrophils play a critical role in killing many bacterial pathogens, including P. aeruginosa (32, 33). Hypercapnia did not prevent the recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs of P. aeruginosa–infected mice (Table 2). However, the recruited neutrophils in hypercapnic mice phagocytosed fewer bacteria (Figure 4A) and exhibited a reduced capacity for ROS generation (Figure 4B). The inhibition of these two key antimicrobial phagocyte functions is likely an important mechanism underlying the increased growth and dissemination of P. aeruginosa and death from pneumonia in hypercapnic mice. Interestingly, IL-6 and TNF levels were reduced in the BAL fluid and lung tissue of 10% CO2–exposed mice compared with air-exposed mice, 7 hours (but not 15 h) after P. aeruginosa infection (Figure 5), reminiscent of our previous report that hypercapnia inhibited the macrophage expression of IL-6 and TNF in vitro (22). Given that IL-6 and TNF are known to enhance defense against bacterial infections in vivo and increase phagocytosis and ROS generation by neutrophils in vitro (43, 44), these findings suggest that deficient IL-6 and TNF production may account for the impaired lung neutrophil function in P. aeruginosa–infected hypercapnic mice. The reduction of lung IL-6 and TNF levels in hypercapnic mice at 7 hours (but not 15 h) after infection could reflect defective host defense associated with the decrease in cytokines early after infection, followed by increased inflammatory mediator release attributable to uncontrolled infection at the later time point.

Although hypercapnia increased the mortality of Pseudomonas pneumonia, it did not worsen histologic lung inflammation or injury at either 7 or 15 hours after infection (Figure 3). The lack of difference in histologic lung inflammation between 10% CO2–exposed and air-exposed animals coincides with the finding that neutrophil counts in BAL fluid did not differ between the two groups (Table 2). These observations, in combination with the greater burden of bacteria in the livers and spleens of 10% CO2–exposed animals 15 hours after infection (Figure 2), suggest that hypercapnia may increase pneumonia mortality primarily by increasing bacterial dissemination as a consequence of defective lung neutrophil function, leading to uncontrolled systemic sepsis, rather than by worsening pneumonia-associated respiratory failure.

As already noted, another group has studied the impact of hypercapnia in a rat model of pulmonary infection with E. coli, finding alternately deleterious or beneficial effects using a variety of protocols in multiple reports (17–21). In all but one of these, the effects of hypercapnia were evaluated exclusively in anesthetized animals undergoing mechanical ventilation over a period of 4 to 6 hours. The exception is the 2008 study by O'Croinin and colleagues (18), in which rats were allowed to breathe spontaneously for 48 hours after infection, then anesthetized, mechanically ventilated, and killed, after which BAL was performed and lungs processed for assessment of lung injury. As in our study, O'Croinin and coworkers found that hypercapnia increased the burden of bacteria in the lungs and impaired neutrophil phagocytosis. However, in contrast to our findings, in their report exposure of rats to elevated CO2 increased pneumonia-associated histologic lung injury. This might reflect a difference between mice and rats, or an important difference in experimental protocol. Of note, in our study, after infection mice breathed spontaneously for the remainder of all experiments, while in the previous study, rats breathed spontaneously for 48 hours, then were mechanically ventilated prior to analysis of lung histology.

Our investigation differs from the aforementioned rat studies in a number of other important respects. First, whereas E. coli is an uncommon pneumonia pathogen in humans, we used a model of pneumonia with P. aeruginosa, an important cause of pulmonary infection in patients who commonly manifest hypercapnia, such as those with advanced COPD, cystic fibrosis, and other forms of chronic lung disease, and during prolonged acute respiratory failure. Second, although in several previous studies, BAL cell counts and cytokine levels were measured at the end of the protocol (always after a period of mechanical ventilation), we performed these assessments at more than one time, early and later during the evolution of pneumonia, in spontaneously breathing mice. This allowed us to identify reductions in lung IL-6 and TNF secretion in hypercapnic mice early (7 h), indicating an initially impaired host response, even though later in the course of infection (15 h), the levels of these cytokines were not different in hypercapnic and air-exposed mice. Third, whereas it was previously reported that exposure of rats to elevated CO2 reduced phagocytosis of latex beads by peripheral blood neutrophils ex vivo (18, 21), we showed in the mouse that hypercapnia impaired phagocytosis of pathogenic bacteria by lung neutrophils in vivo. Fourth, since in each of the earlier studies animals were subjected to mechanical ventilation, they did not allow for the effects of hypercapnia to be separated from possible ventilator-induced lung injury. On the other hand, we assessed the evolution and outcome of pneumonia in spontaneously breathing mice, without the confounding influence of mechanical ventilation. It could be argued that even spontaneously breathing mice exposed to 10% CO2 would exhibit higher than normal tidal volumes, and that this might be injurious to the lung. However, we believe this is unlikely, because in the absence of infection, exposure to hypercapnia for 3 days caused no histologic lung injury (Figure 3), no influx of inflammatory cells into the lungs (Table 2), and no increase in lung cytokines or chemokines (Figure E4 and data not shown), and because uninfected mice were able to live in 10% CO2 for up to 2 weeks with normal levels of activity and no apparent distress. Finally, because our protocol did not entail anesthesia, mechanical ventilation, and killing of the animals at the end of each experiment, we were able to demonstrate that hypercapnia increased the mortality from bacterial pneumonia (Figure 1), and that the adverse impact of hypercapnia on pneumonia survival was reversible (Figure 6), critical outcomes that no previous study has ever shown.

Remarkably, the immunosuppressive effects of hypercapnia are not limited to mammals. We recently reported that hypercapnia inhibited the expression of antimicrobial peptides in Drosophila melanogaster (45). Furthermore, as in murine P. aeruginosa pneumonia, hypercapnia increased the mortality of bacterial infections in Drosophila (45). The expression of antimicrobial peptides suppressed by hypercapnia in flies is regulated by the Toll and immune deficiency pathways, both analogous to the canonical mammalian NF-κB signaling pathway that regulates the expression of TNF, IL-6, and other innate immunity genes suppressed by hypercapnia in human and mouse macrophages (45). These findings suggest that hypercapnia down-regulates innate immune gene expression by an evolutionarily conserved mechanism, which, if true, offers the opportunity to use Drosophila as a model to elucidate the components of a novel pathway by which elevated CO2 triggers immunosuppression (46).

Because patients with hypercapnia and severe lung disease are at high risk for and often present with lung infections, our data suggest that hypercapnia may contribute to poor clinical outcomes in such individuals. Our findings also raise the possibility that “permissive” hypercapnia during the mechanical ventilation of patients with ARDS (47) may exert adverse effects on host defense. Clinical studies will be required to determine whether hypercapnia does indeed increase the risk or worsen the outcomes of infection in humans, and whether strategies to correct hypercapnia or interrupt CO2-induced signaling can improve innate immune function and resistance to infection in patients with advanced lung disease.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Gokhan Mutlu, Scott Budinger, and Paul Bryce for advice and reagents, and Ziyan Lu and Dr. Daniela Ulrich for technical assistance. Microscopy and image analyses were performed at the Northwestern University Cell Imaging Facility, and flow cytometry was performed at the Flow Cytometry Facility of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center (supported by National Institutes of Health grant P30 CA060553).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants T32 HL076139, F32 HL103012, and K01 HL108860 (K.L.G.), R01 HL072891 and a Veterans Affairs Merit Review (P.H.S.S.), R01 HL085534 (J.I.S.), and R01 AI075191 and R01 AI053674 (A.R.H.).

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0487OC on June 18, 2013

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Minino AM.Death in the United States, 2009. NCHS Data Brief2011641–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, Agusti AG. Mortality in COPD: role of comorbidities. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1245–1257. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00133805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan APR, Reddy LN, Rao MH, Sharma SK, Kamity R, Bollineni S. Clinical presentation and predictors of outcome in patients with severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring admission to the intensive care unit. BMC Pulm Med. 2006;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Budweiser S, Jorres RA, Riedl T, Heinemann F, Hitzl AP, Windisch W, Pfeifer M. Predictors of survival in COPD patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure receiving noninvasive home ventilation. Chest. 2007;131:1650–1658. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacIntyre N, Huang YC. Acute exacerbations and respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:530–535. doi: 10.1513/pats.200707-088ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slenter RH, Sprooten RT, Kotz D, Wesseling G, Wouters EF, Rohde GG. Predictors of 1-year mortality at hospital admission for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2013;85:15–26. doi: 10.1159/000342036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sin DD, Man SF, Marrie TJ. Arterial carbon dioxide tension on admission as a marker of in-hospital mortality in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laserna E, Sibila O, Aguilar PR, Mortensen EM, Anzueto A, Blanquer JM, Sanz F, Rello J, Marcos PJ, Velez MI, et al. Hypocapnia and hypercapnia are predictors for ICU admission and mortality in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2012;142:1193–1199. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belkin RA, Henig NR, Singer LG, Chaparro C, Rubenstein RC, Xie SX, Yee JY, Kotloff RM, Lipson DA, Bunin GR. Risk factors for death of patients with cystic fibrosis awaiting lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:659–666. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200410-1369OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheikh HS, Tiangco ND, Harrell C, Vender RL. Severe hypercapnia in critically ill adult cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Med Res. 2011;3:209–212. doi: 10.4021/jocmr612w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, Magaldi RB, Schettino GP, Lorenzi-Filho G, Kairalla RA, Deheinzelin D, Munoz C, Oliveira R, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:347–354. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kregenow DARG, Hudson LD, Swenson ER. Hypercapnic acidosis and mortality in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000194533.75481.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broccard AFHJ, Vannay C, Markert M, Sauty A, Feihl F, Schaller MD. Protective effects of hypercapnic acidosis on ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:802–806. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2007060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinclair SE, Kregenow DA, Lamm WJE, Starr IR, Chi EY, Hlastala MP. Hypercapnic acidosis is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:403–408. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200112-117OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laffey JGHD, Hopkins N, Hyvelin JM, Boylan JF, McLoughlin P. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;169:46–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-394OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Croinin DF, Hopkins NO, Moore MM, Boylan JF, McLoughlin P, Laffey JG. Hypercapnic acidosis does not modulate the severity of bacterial pneumonia–induced lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2606–2612. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186761.41090.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Croinin DF, Nichol AD, Hopkins N, Boylan J, O’Brien S, O’Connor C, Laffey JG, McLoughlin P. Sustained hypercapnic acidosis during pulmonary infection increases bacterial load and worsens lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2128–2135. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817d1b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni Chonghaile M, Higgins BD, Costello JF, Laffey JG. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates the severe acute bacterial pneumonia–induced lung injury by a neutrophil-independent mechanism. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3135–3144. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f0d13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chonghaile MN, Higgins BD, Costello J, Laffey JG. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates lung injury induced by established bacterial pneumonia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:837–848. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181895fb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nichol AD, O’Cronin DF, Howell K, Naughton F, O’Brien S, Boylan J, O’Connor C, O’Toole D, Laffey JG, McLoughlin P. Infection-induced lung injury is worsened after renal buffering of hypercapnic acidosis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2953–2961. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b028ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang N, Gates KL, Trejo H, Favoreto S, Schleimer RP, Sznajder JI, Beitel GJ, Sporn PHS. Elevated CO2 selectively inhibits interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor expression and decreases phagocytosis in the macrophage. FASEB J. 2010;24:2178–2190. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang CJ, Dong P, Hosszu EK, Doyle IR. Effect of CO2 on LPS-induced cytokine responses in rat alveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L96–L103. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummins EP, Oliver KM, Lenihan CR, Fitzpatrick SF, Bruning U, Scholz CC, Slattery C, Leonard MO, McLoughlin P, Taylor CT. NF-kappaB links CO2 sensing to innate immunity and inflammation in mammalian cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:4439–4445. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shirai R, Kadota J, Tomono K, Ogawa K, Iida K, Kawakami K, Kohno S. Protective effect of granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF) in a granulocytopenic mouse model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection through enhanced phagocytosis and killing by alveolar macrophages through priming tumour necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) production. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;109:73–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4211317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laichalk LKS, Strieter R, Danforth JM, Baile M, Standiford T. Tumor necrosis factor mediates lung antibacterial host defense in murine Klebsiella pneumonia. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5211–5218. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5211-5218.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones MR, Simms BT, Lupa MM, Kogan MS, Mizgerd JP. Lung NF-kappaB activation and neutrophil recruitment require IL-1 and TNF receptor signaling during pneumococcal pneumonia. J Immunol. 2005;175:7530–7535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comolli JC, Hauser AR, Waite L, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS, Engel JN. Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products PilT and PilU are required for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3625–3630. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3625-3630.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acred P, Hennessey TD, MacArthur-Clark JA, Merrikin DJ, Ryan DM, Smulders HC, Troke PF, Wilson RG, Straughan DW. Guidelines for the welfare of animals in rodent protection tests. Lab Anim. 1994;28:13–18. doi: 10.1258/002367794781065870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojielo CI, Cooke K, Mancuso P, Standiford TJ, Olkiewicz KM, Clouthier S, Corrion L, Ballinger MN, Toews GB, Paine R, III, et al. Defective phagocytosis and clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lung following bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 2003;171:4416–4424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cimolai N, Taylor GP, Mah D, Morrison BJ. Definition and application of a histopathological scoring scheme for an animal model of acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae pulmonary infection. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:465–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diaz MH, Shaver CM, King JD, Musunuri S, Kazzaz JA, Hauser AR. Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces localized immunosuppression during pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4414–4421. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00012-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh AY, Priebe GP, Ray C, Van Rooijen N, Pier GB. Inescapable need for neutrophils as mediators of cellular innate immunity to acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2009;77:5300–5310. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00501-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rello J, Diaz E, Rodriguez A. Etiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2005;26:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montero M, Dominguez M, Orozco-Levi M, Salvado M, Knobel H. Mortality of COPD patients infected with multi-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a case and control study. Infection. 2009;37:16–19. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molinos L, Clemente MG, Miranda B, Alvarez C, del Busto B, Cocina BR, Alvarez F, Gorostidi J, Orejas C. Community-acquired pneumonia in patients with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect. 2009;58:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Vidal C, Almagro P, Romani V, Rodriguez-Carballeira M, Cuchi E, Canales L, Blasco D, Heredia JL, Garau J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients hospitalised for COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:194–222. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.194-222.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maughan H, Cunningham KS, Wang PW, Zhang Y, Cypel M, Chaparro C, Tullis DE, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S, Liu M, Guttman DS, Hwang DM.Pulmonary bacterial communities in surgically resected noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis lungs are similar to those in cystic fibrosis. Pulm Med [online ahead of print] 8 Feb 2012; DOI:10.1155/2012/746358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Miller D, Fraser K, Murray I, Thain G, Currie GP. Predicting survival following non-invasive ventilation for hypercapnic exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:434–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perrin K, Wijesinghe M, Weatherall M, Beasley R. Assessing PaCO2 in acute respiratory disease: accuracy of a transcutaneous carbon dioxide device. Intern Med J. 2011;41:630–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cole N, Bao S, Stapleton F, Thakur A, Husband AJ, Beagley KW, Willcox MDP. Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis in IL-6–deficient mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2003;130:165–172. doi: 10.1159/000069006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stäger SMA, Zubairi S, Sanos SL, Kopf M, Kaye PM. Distinct roles for IL-6 and IL-12p40 in mediating protection against Leishmania donovani and the expansion of IL-10+ CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1764–1771. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helenius IT, Krupinski T, Turnbull DW, Gruenbaum Y, Silverman N, Johnson EA, Sporn PHS, Sznajder JI, Beitel GJ. Elevated CO2 suppresses specific Drosophila innate immune responses and resistance to bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18710–18715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905925106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vadasz I, Dada LA, Briva A, Helenius IT, Sharabi K, Welch LC, Kelly AM, Grzesik BA, Budinger GR, Liu J, et al. Evolutionary conserved role of c-Jun–N-terminal kinase in CO2-induced epithelial dysfunction. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuxen DV. Permissive hypercapnic ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:870–874. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.3.8087364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]