Abstract

Preliminary studies suggest that a subgroup of septic patients with severe immune alterations is at high risk of death or nosocomial infection and therefore could benefit from adjunctive immune stimulating therapies. There is thus an urgent need for robust biomarkers usable in routine conditions evaluating rapidly evolving immune status in patients. Although functional testing remains a gold standard, its standardisation remains challenging. Therefore, surrogate markers such as monocyte HLA-DR expression, are being developed. Such biomarkers of immune functionality will enable a novel approach in the design of clinical trials evaluating immunostimulating therapies in sepsis at the right time and in the right patient.

Introduction

Sepsis has been called a hidden public disaster. In 2012, over 20 million patients world-wide are estimated to be afflicted by sepsis annually and recent epidemiological analyses showed that mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock is still elevated – around 30% both in Europe and USA [1]. Both pro and anti-inflammatory responses are initially induced in septic shock patients with the secondary occurrence of sepsis-induced immunosuppression [2]. Importantly, the intensity and duration of sepsis-induced immune alterations have been associated with increased risk of deleterious events in patients, while over 70% of total mortality after septic shock occurs in a delayed fashion (i.e., after the first 3 days). This constitutes the rational for the initiation of innovative clinical trials testing adjunctive immunostimulating drugs in sepsis [2].

However, as there is no clinical sign of immunosuppression, there is an urgent need for rapid, sensitive and specific biomarkers of the robustness of patients’ immune status. This ability to semi-quantitate patient immune status will contribute to the success of future immune targeted clinical trials based on the inclusion of appropriately stratified patients. The review will focus on recent advances in aspects of immunomonitoring in septic patients with the perspective of a use as stratification tools in immunostimulating clinical trials.

The concept of sepsis-induced immunosuppression

Several lines of clinical evidence suggest that septic patients who survive the initial few days of the disorder acquired various defects in immunity. This is mainly illustrated by their decreased capacity to overcome initial or secondary infectious challenges. Indeed, a recent post-mortem study showed that approximately 80% septic patients had unresolved septic foci at time of death [3]. Similarly, many pathogens responsible for nosocomial sepsis in intensive care unit [ICU] (Acinetobacter, Candida…) are weakly virulent opportunistic germs usually isolated from severely immunodepressed patients [4]. This is consistent with the high incidence in septic patients of reactivation of latent viruses (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus) that are normally held in abeyance by host immunity [5–7]. Finally, clinical studies showed a link between altered immune functions and patients’ susceptibility to secondary infections [8–11]. This phenomenon of ICU-acquired immune dysfunctions has been called compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis-induced immunosuppression, or cellular reprogramming [2,12].

Although not exhaustively described, pathophysiologic mechanisms at play have begun to be understood (Table 1). In particular, epigenetic regulation, energetic failure, central and endocrine regulations, increased apoptosis or endotoxin tolerance have been shown to be playing a role both in clinical observations and animal models of sepsis [13–16]. Such immune alterations affect both the innate and adaptive parts of the immune response, occur rapidly after patients’ admission, and are present both peripherally in circulating blood cells but also locally in organs [17]. They thus represent a very profound and systemic process. Importantly, a number of clinical observations showed that the intensity and duration of these sepsis-induced immune dysfunctions (evaluated by different approaches [18]) are associated with increased risk for deleterious outcomes (death or secondary ICU-acquired infections).

Table 1.

Sepsis-induced immune dysfunctions: pathophysiology at a glance

| Mechanisms | Features of sepsis-induced immune alterations |

|---|---|

| Endotoxin tolerance | ↓ pro-inflammatory ↑ anti-inflammatory cytokine production |

| ↓ Ag presentation capacity | |

| Apoptosis | ↓ cell number |

| Cell anergy | |

| Energetic failure | Cell anergy |

| Apoptosis | |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | |

| Anti-inflammatory mediators | ↓ activating co-receptor expressions |

| ↑ inhibitory co-receptor expressions | |

| Cell anergy | |

| Endotoxin tolerance | |

| Epigenetic regulation | ↓ pro-inflammatory gene expressions |

| Cellular reprogramming | |

| Central and endocrine Regulations | ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokine production |

Monitoring innate immune alterations in sepsis and related therapies

Innate immune cells represent the first line of defence after an infection and thus play a central role in the control of pathogens and initiation of adaptive immune responses. Animal models of sepsis and experimental studies in patients depicted altered innate immune cell functions [13]. However, except for monocytes, few studies identified a link between these alterations and clinical outcomes in patients. In particular, recent studies showed that, after sepsis, circulating neutrophils have altered functions such as impaired bacterial clearance, abnormal radical oxygen species production, and decreased recruitment to infected tissues [19,20]. Similarly, recent experimental studies proposed a role for late onset myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) in sepsis pathophysiology [21,22]. However, to date, no clinical studies showed a link between these parameters and clinical outcomes in patients. Regarding MDSC, it might be due to the complexity of their immunophenotyping and to the absence of any consensually accepted phenotype in humans. Interestingly, recent studies described NK cell functional alterations (reduced IFNγ secretion) and decreased cell number in sepsis [23–25]. However clinical studies formally identifying a link between these alterations and clinical outcomes are still lacking. Moreover, the transfer of such functional approaches (in vitro cytokine release [26,27] or granulomatous response [25]) in clinical practice remains very complex.

Dendritic cells (DC), the professional antigen presenting cells, are sentinels in tissues and play an important role in initiation and modulation of T cell responses. DCs in sepsis exhibited altered phenotype and functions with, in particular, a decreased expression of Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR (HLA-DR) and reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines upon stimulation by bacterial products [11,28]. Interestingly, in septic patients, the peripheral DC count is low and this decrease has been shown to be associated with worsened clinical outcomes in sepsis including death and nosocomial infections [11,29].

Besides the previously mentioned clinical studies, many studies have described altered monocyte phenotype and functions in sepsis [30–32]. In particular, decreased expression of HLA-DR (mHLA-DR) on circulating monocytes has been observed and is proposed as a surrogate marker of immune failure [33]. Increased circulating IL-10 production has been postulated to play a role in this process and studies showed the association between increased plasmatic IL-10 concentration and clinical outcomes such as nosocomial infections [34,35]. mHLA-DR downregulation has been shown to be predictive of complications in numerous clinical conditions (Table 2) and is applicable for clinical practice with standardized tests [36,37]. Importantly, studies show an association between the lack of recovery of mHLA-DR expression overtime and secondary infections in sepsis [9,10]. This finding highlights the importance of the timing of immunomonitoring in regard to the expected homeostatic response and the phase of sepsis. In other words, immune enhancing therapy needs to be applied during the immunosuppressive phase of the disorder as indicated by decreased mHLA-DR expression. Therapeutic protocols with GM-CSF, G-CSF and IFNγ have been conducted in sepsis with the aims to stimulate innate immune function, improve myelopoiesis and limit lymphocyte apoptosis. Small clinical studies in ICU patients with sepsis or trauma showed no effect to decrease mortality but there was a beneficial effect on illness severity and rate of pathogen clearance [38–42]. Interestingly, no study detected any adverse events. The lack of overall benefit on mortality in these pilot studies might be related to the failure to select patients based upon their respective immune status, e.g. using monocyte mHLA-DR expression. In those clinical studies in which mHLA-DR was measured, immune-adjuvant therapy lead to increased mHLA-DR expression [10,39,43]. Along with the recovery of mHLA-DR expression, stimulated whole blood TNFα release was restored in response to immunotherapy [39,42] thereby suggesting that mHLA-DR expression might be clinically useful as a biomarker for identifying patients who would be appropriate candidates for immunotherapy and to monitoring responsiveness to treatment.

Table 2.

Recent clinical studies evaluating mHLA-DR predictive value regarding outcome in injured patients.

| 1st author, Journal, Year |

Nbr of patients |

Pathology | Evaluation | Results | Other inflammatory parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monneret, Intensive Care Med, 2006 | 93 | septic shock | outcome | No association of initial mHLA-DR with outcome Low mHLA at day3-4 associated with poor outcome |

No |

| Venet, Crit Care Med, 2007 | 14 | severe burns | outcome and infection | Low HLA-DR associated with outcome and infection | Decreased plasma IL-6 and TNFα, but not IL-10 |

| Lukaszewicz, Crit Care Med, 2009 | 283 | ICU patients | outcome and infection | No association of initial mHLA-DR with outcome Variation of mHLA-DR over time associated with infection |

No |

| Berres, Liver Int, 2009 | 38 | decompensated liver cirrhosis | outcome | Association of initial low mHLA-DR with poor outcome mHLA-DR decreased (day0 to day 3) in NS |

Plasma IFNγ, ex vivo stimulated TNFα and IL-6 |

| Landelle, Intensive Care Med, 2010 | 209 | septic shock | outcome and infection | No association of initial mHLA-DR with outcome Day3-4 and day 9-11 mHLA-DR associated with infection |

No |

| Chéron, Crit Care, 2010 | 105 | trauma | Infection and sepsis | No association of initial mHLA-DR with outcome Low mHLA-DR at day3-4 associated with infection |

No |

| Wu, Crit Care, 2011 | 79 | severe sepsis | outcome | mHLA-DR associated with outcome | No |

| Wu, Crit Care, 2011 | 35 | severe sepsis | outcome | mHLA-DR increase associated with outcome | Stimulated IL-6 and IL-12 |

| Zhang, Eur J Neurol, 2011 | 53 | neurologic patients | infection | Day 2 mHLA-DR predictive for infection Persistent low mHLA-DR associated with outcome |

No |

| Lin, Blood, 2011 | 40 | B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma | outcome | High ratio of HLA-DR low monocytes is related to more aggressive disease | Low TNFα receptor II Decrease production of IFNγ and proliferation |

| Berry, Intensive Care Med, 2011 | 100 | cirrhosis | outcome | In 33 ICU patients, decrease in mHLA-DR associated with poor outcome | Ex vivo stimulated IL-10, IFNγ , TNFα |

| Gouel-Chéron, PLoS One, 2012 | 100 | trauma | Infection and sepsis | Variation of mHLA-DR over time associated with infection | Plasma IL-6 |

| Trimmel, Shock, 2012 | 413 | ICU patients | outcome | Minimal value of HLA-DR associated with outcome | No |

Only studies published in or after 2006 were considered.NS: non survivors, S: survivors, ICU: intensive care unit, mHLA-DR: monocyte Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR, IFN: interferon, IL: interleukin, TNF: tumor necrosis factor, LPS: lipopolysaccharide

Monitoring adaptive immune alterations in sepsis and related therapies

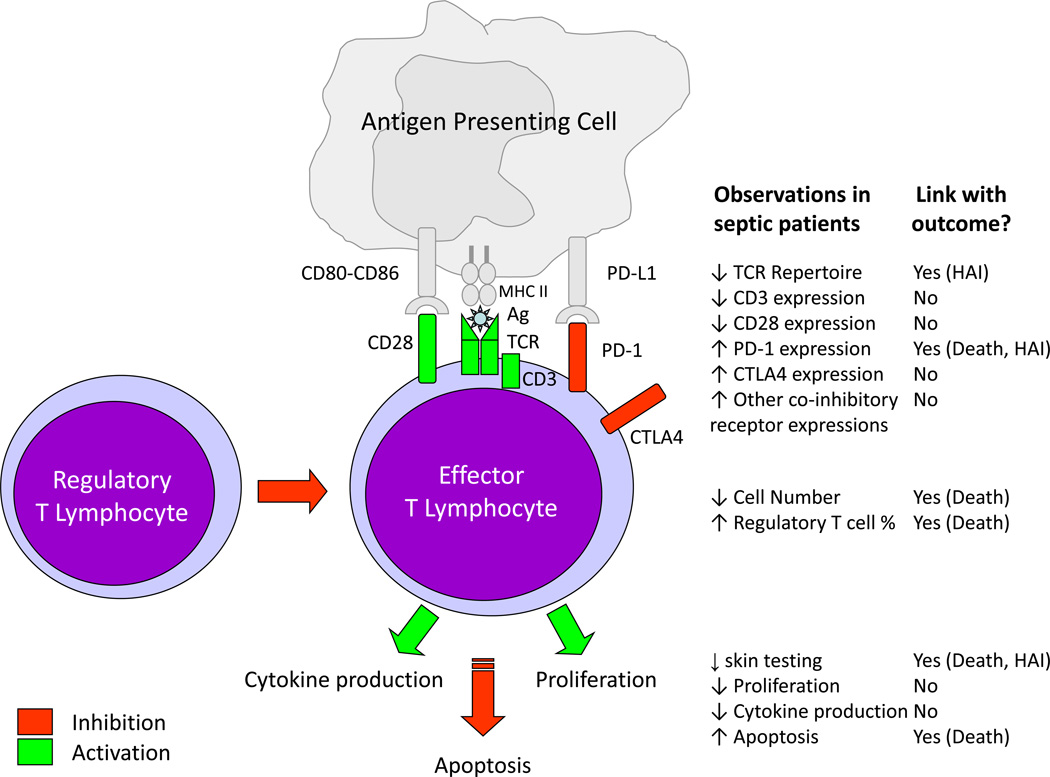

Since the seminal description of a loss of DTH response in surgical patients associated with increased risk of nosocomial infections more than 20 years ago, T lymphocyte anergy has been shown to be a hallmark of sepsis-induced immune dysfunctions [8,44]. Numerous aspects of this dysfunction have been described both in animal models of sepsis and in clinic (Figure 1). In particular, marked decreased cell number linked with increased apoptosis was repeatedly described in patients [45,46]. Functional alterations such as reduced ex vivo proliferation, decreased pro-inflammatory (IL-2, IFNγ, IL-17) and increased anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokine productions were observed [17,47,48]. Phenotypic alterations such as reduced co-activating receptor (CD28), increased co-inhibitory receptor (PD-1, CTLA4) expressions or decreased T cell receptor repertoire diversity [17,49–51] also represent characteristics of septic T lymphocytes. Finally, an increased percentage of circulating CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells has been repeatedly observed in septic patients [52]. In some studies, a link between the intensity and duration of these alterations and subsequent mortality/ nosocomial infections risk was observed [48,50,51].

Figure 1. T Lymphocyte alterations in sepsis and link with outcomes.

TCR: T Cell Receptor, Ag: Antigen, MHC II: Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II, PD-1: Programmed cell Death-1, PD-L1: Programmed cell death ligand 1, CTLA4: Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4, HAI: Hospital-Acquired Infection.

However, as opposed to mHLA-DR measurement, to date, no consensually defined marker of sepsis-induced lymphocyte alterations has emerged in the literature. So far, the best available test for assessment of lymphocyte functionality remains the measurement of proliferation in response to recall antigens or mitogen stimulations. However, limitations inherent to such measurement (tritiated thymidine uptake, several days-incubation time) preclude its use in large clinical studies. Other parameters of lymphocyte functionality such as expression of positive or negative co-inhibitory receptors, percentage of T regulatory cells, quantitation of lymphocyte ATP, etc. suffer from a lack of standardization and paucity of clinical studies in sepsis. Thus, there is no “gold standard” method for evaluating lymphocyte function that would enable investigators to link cell function with sepsis outcome. Therefore, a major effort is needed to develop robust biological tests of lymphocyte function that are suitable for routine clinical laboratory and which correlate with objective outcomes such as risk of nosocomial infection or sepsis survival.

Recognizing the pivotal role of lymphocytes (mainly CD4+ T cells) in orchestrating immune responses, one may expect that, by restoring their function, it might be possible to generate a positive global effect on the overall immune response, both mediated by lymphocytes and innate immune cells. Promising immunotherapeutic agents include recombinant human IL-7 (rhIL-7) and anti-programmed cell death-1 (anti-PD-1) antibody [2,53]. Inhibitory therapy of PD-1 is currently being examined in phase III clinical trials in oncology [54]. Preliminary results showed its efficacy in inducing durable tumor regression and prolonged stabilization of disease in patients with advanced cancers [55]. In sepsis, such therapy might be administered to patients after stratification based on PD-1 expression [50]. rhIL-7 is also currently being tested in phase I and II clinical trials in chronic viral infections, following chemotherapy and/or bone marrow transplantation, and in idiopathic CD4+ lymphopenia [56]. In murine models of polymicrobial sepsis, rhIL-7 restored DTH response, decreased sepsis-induced lymphocyte apoptosis, reversed sepsis-induced depression of IFN-γ production and improved survival [57,58]. We recently demonstrated rhIL-7’s ability to reverse sepsis-induced T cell alterations (decreased CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation, IFN-γ production, STAT5 phosphorylation and Bcl-2 induction) in septic shock patients ex vivo 47].

Conclusion

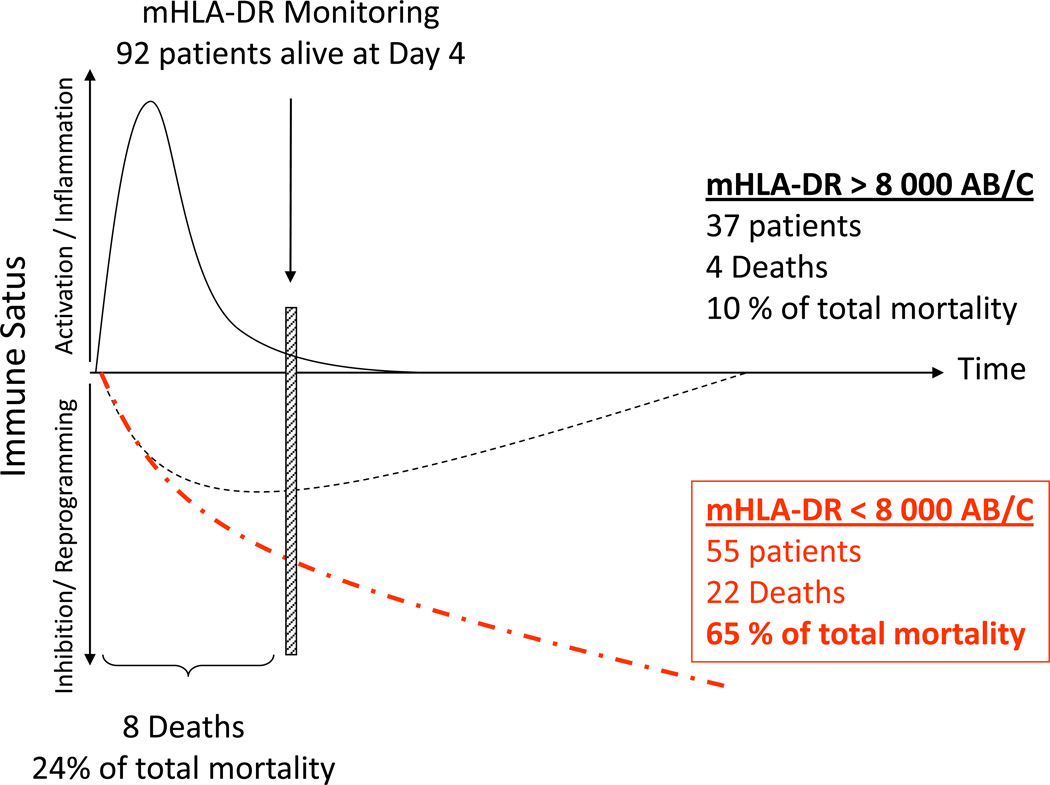

Immune monitoring after sepsis enables the identification of a subgroup of patients at high risk of death or nosocomial infection who could benefit the most from adjunctive immune stimulating therapies. It is estimated that over half of patients with sepsis develop immunosuppression and would benefit from therapies that boost immunity (Figure 2). The failure of many therapies in sepsis is likely related to the lack of stratification of patients based upon their particular immune functional status. Furthermore beyond variability in the immune response, septic syndromes also represent a heterogeneous group of diseases (different co-morbidities, types and sites of infections, initial severities, community-acquired or nosocomial infections). Therefore inclusion of such patients without prior biomarker-based stratification might have largely participated in the failure of previous clinical trials in the field [59]. Thus, if we want to partially decrease this heterogeneity, future clinical trials of immune-adjuvant therapies in sepsis must be based on patients’ stratification using immune status biomarkers that reflect both innate and adaptive immune function. Potential markers include some currently available measures such as mHLA-DR, absolute CD4+ T cell count, circulating IL-10, and regulatory T cells measurements. Among these, some are already currently available in routine labs (absolute CD4+ T cell count, plasmatic IL10 concentration). Others, such as regulatory T cell evaluation, should benefit from recent technical development before becoming available in routine practice (e.g. one-step intracellular FOXP3 staining). Monocyte HLA-DR expression, in contrary, has already been tested in inter-laboratory experiments and is ready for prime time [36,37]. A recent study by Meisel et al. used these principles of patient selection based upon immune status [39]. In a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 38 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock were treated with GM-CSF or placebo. Inclusions were restricted to patients presenting with sepsis-associated immunosuppression as defined by a decreased mHLA-DR (< 8,000 monoclonal antibodies bound per cell) for 2 consecutive days. Results showed that biomarker-guided GM-CSF therapy in sepsis was safe, effective in restoring monocytic immunocompetence cytokine production of TNF-α, and, most importantly, shorten the time of mechanical ventilation and hospital/intensive care unit stay. These very promising preliminary results should now be validated in a large multi-center clinical trial using similar biomarker-guided stratification. We strongly believe that such biomarker-guided strategy can be safely applied and will offer an exciting new approach to this highly lethal disease.

Figure 2. Septic shock patients stratification based on a biomarker: one virtual cohort based on real data.

Based on personal data, one hundred septic shock patients were included in a virtual clinical study and monitored at Day 1-2, Day 3-5 and Day 7-10 for Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR expression on circulating monocytes [9,32]. Results are expressed as number of anti-HLA-DR antibodies bound per monocytes (AB/C). Patients are stratified based on mHLA-DR measured at Day3-5 (mHLA-DR threshold = 8 000 AB/C [39]). Twenty-eight day mortality is 34% (i.e. n = 34 non-survivors in total). Only 8 deaths occur within the first 3 days. Ninety-eight patients are still alive at Day 4 and could be stratified. Decreased mHLA-DR is observed in 55 patients. In this subgroup, 22 deaths occur (i.e. 65% of total mortality). This virtual cohort based on real observations illustrates that a decreased mHLA-DR identifies a subgroup of septic shock patients at high risk of death or secondary infection. In this subpopulation, there is a strong rational for the initiation of innovative immune stimulating therapies.

Highlights.

Immunomonitoring identifies septic patients who could benefit from immunotherapy

Immune stratification should be considered in clinical trials design in sepsis

Functional tests remain a gold standard but surrogate markers are being identified

Robust biomarkers of immune status in sepsis need to be further developed

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments and Funding

GM and FV were supported by funds from the Hospices Civils de LYON.

R.S.H. was supported by the National Institutes of Health – GM44118 and GM 55194.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Levy MM, Artigas A, Phillips GS, Rhodes A, Beale R, Osborn T, Vincent JL, Townsend S, Lemeshow S, Dellinger RP. Outcomes of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in intensive care units in the USA and Europe: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:919–924. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:260–268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X. An up-to-date review on sepsis-induced immunosuppression.

- 3. Torgersen C, Moser P, Luckner G, Mayr V, Jochberger S, Hasibeder WR, Dunser MW. Macroscopic postmortem findings in 235 surgical intensive care patients with sepsis. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1841–1847. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318195e11d. This study describes the persistence of an infectious focus in patients that died of sepsis.

- 4.Landelle C, Lepape A, Francais A, Tognet E, Thizy H, Voirin N, Timsit JF, Monneret G, Vanhems P. Nosocomial infection after septic shock among intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:1054–1065. doi: 10.1086/591859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Limaye AP, Kirby KA, Rubenfeld GD, Leisenring WM, Bulger EM, Neff MJ, Gibran NS, Huang ML, Santo Hayes TK, Corey L, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in critically ill immunocompetent patients. JAMA. 2008;300:413–422. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiche L, Forel JM, Roch A, Guervilly C, Pauly V, Allardet-Servent J, Gainnier M, Zandotti C, Papazian L. Active cytomegalovirus infection is common in mechanically ventilated medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1850–1857. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819ffea6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luyt CE, Combes A, Deback C, Aubriot-Lorton MH, Nieszkowska A, Trouillet JL, Capron F, Agut H, Gibert C, Chastre J. Herpes simplex virus lung infection in patients undergoing prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:935–942. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200609-1322OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christou NV, Meakins JL, Gordon J, Yee J, Hassan-Zahraee M, Nohr CW, Shizgal HM, MacLean LD. The delayed hypersensitivity response and host resistance in surgical patients. 20 years later. Ann Surg. 1995;222:534–546. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199522240-00011. discussion 546-538. A meta-analysis of 20 years of studies investigating the link between lymphocyte anergy (loss of delayed-type hypersensitivity) in injured and post-surgical patients and mortality.

- 9. Landelle C, Lepape A, Voirin N, Tognet E, Venet F, Bohe J, Vanhems P, Monneret G. Low monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR is independently associated with nosocomial infections after septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1859–1866. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1962-x. The first clinical study including multivariate analysis and competitive risk approach establishing the link between reduced mHLA-DR and susceptibility to secondary infections in septic shock patients.

- 10.Lukaszewicz AC, Grienay M, Resche-Rigon M, Pirracchio R, Faivre V, Boval B, Payen D. Monocytic HLA-DR expression in intensive care patients: interest for prognosis and secondary infection prediction. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2746–2752. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab858a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimaldi D, Louis S, Pene F, Sirgo G, Rousseau C, Claessens YE, Vimeux L, Cariou A, Mira JP, Hosmalin A, et al. Profound and persistent decrease of circulating dendritic cells is associated with ICU-acquired infection in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1438–1446. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavaillon JM, Adrie C, Fitting C, Adib-Conquy M. Reprogramming of circulatory cells in sepsis and SIRS. J Endotoxin Res. 2005;11:311–320. doi: 10.1179/096805105X58733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Dou Y, Kunkel SL. Epigenetic regulation of immune cell functions during post-septic immunosuppression. Epigenetics. 2011;6:273–283. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.3.14017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opal SM. New perspectives on immunomodulatory therapy for bacteraemia and sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36S2:S70–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fullerton JN, Singer M. Organ failure in the ICU: cellular alterations. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 32:581–586. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1287866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD, 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594–2605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1829. This study showed for the first time that immunosuppression was present no only in peripheral blood cells but also locally in organs in patients that died of sepsis.

- 18.Monneret G, Venet F, Pachot A, Lepape A. Monitoring immune dysfunctions in the septic patient: a new skin for the old ceremony. Mol Med. 2008;14:64–78. doi: 10.2119/2007-00102.Monneret. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delano MJ, Thayer T, Gabrilovich S, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Winfield RD, Scumpia PO, Cuenca AG, Warner E, Wallet SM, Wallet MA, et al. Sepsis induces early alterations in innate immunity that impact mortality to secondary infection. J Immunol. 2011;186:195–202. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pillay J, Kamp VM, van Hoffen E, Visser T, Tak T, Lammers JW, Ulfman LH, Leenen LP, Pickkers P, Koenderman L. A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits T cell responses through Mac-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:327–336. doi: 10.1172/JCI57990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Derive M, Bouazza Y, Alauzet C, Gibot S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells control microbial sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1040–1049. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2574-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brudecki L, Ferguson DA, McCall CE, El Gazzar M. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells evolve during sepsis and can enhance or attenuate the systemic inflammatory response. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2026–2034. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00239-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Muller L, Klemm A, Durmus N, Weiss M, Suger-Wiedeck H, Schneider M, Hampl W, Mertens T. Cellular immunity and active human cytomegalovirus infection in patients with septic shock. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1288–1295. doi: 10.1086/522429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forel JM, Chiche L, Thomas G, Mancini J, Farnarier C, Cognet C, Guervilly C, Daumas A, Vely F, Xeridat F, et al. Phenotype and functions of natural killer cells in critically-ill septic patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deknuydt F, Roquilly A, Cinotti R, Altare F, Asehnoune K. An in vitro model of mycobacterial granuloma to investigate the immune response in brain-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:245–254. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182676052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berres ML, Schnyder B, Yagmur E, Inglis B, Stanzel S, Tischendorf JJ, Koch A, Winograd R, Trautwein C, Wasmuth HE. Longitudinal monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression is a prognostic marker in critically ill patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2009;29:536–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payen D, Faivre V, Lukaszewicz AC, Villa F, Goldberg P. Expression of monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR in relation with sepsis severity and plasma mediators. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:484–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poehlmann H, Schefold JC, Zuckermann-Becker H, Volk HD, Meisel C. Phenotype changes and impaired function of dendritic cell subsets in patients with sepsis: a prospective observational analysis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R119. doi: 10.1186/cc7969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guisset O, Dilhuydy MS, Thiebaut R, Lefevre J, Camou F, Sarrat A, Gabinski C, Moreau JF, Blanco P. Decrease in circulating dendritic cells predicts fatal outcome in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:148–152. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andre MC, Gille C, Glemser P, Woiterski J, Hsu HY, Spring B, Keppeler H, Kramer BW, Handgretinger R, Poets CF, et al. Bacterial reprogramming of PBMCs impairs monocyte phagocytosis and modulates adaptive T cell responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91:977–989. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0911474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faivre V, Lukaszewicz AC, Alves A, Charron D, Payen D, Haziot A. Human monocytes differentiate into dendritic cells subsets that induce anergic and regulatory T cells in sepsis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monneret G, Lepape A, Voirin N, Bohe J, Venet F, Debard AL, Thizy H, Bienvenu J, Gueyffier F, Vanhems P. Persisting low monocyte human leukocyte antigen-DR expression predicts mortality in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1175–1183. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolk K, Docke WD, von Baehr V, Volk HD, Sabat R. Impaired antigen presentation by human monocytes during endotoxin tolerance. Blood. 2000;96:218–223. This experimental study described in an ex vivo model the association between reduced mHLA-DR and functional alterations in monocytes.

- 34.van Dissel JT, van Langevelde P, Westendorp RG, Kwappenberg K, Frolich M. Anti-inflammatory cytokine profile and mortality in febrile patients. Lancet. 1998;351:950–953. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60606-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose WE, Eickhoff JC, Shukla SK, Pantrangi M, Rooijakkers S, Cosgrove SE, Nizet V, Sakoulas G. Elevated serum interleukin-10 at time of hospital admission is predictive of mortality in patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1604–1611. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demaret J, Walencik A, Jacob MC, Timsit JF, Venet F, Lepape A, Monneret G. Inter-laboratory assessment of flow cytometric monocyte HLA-DR expression in clinical samples. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Docke WD, Hoflich C, Davis KA, Rottgers K, Meisel C, Kiefer P, Weber SU, Hedwig-Geissing M, Kreuzfelder E, Tschentscher P, et al. Monitoring temporary immunodepression by flow cytometric measurement of monocytic HLA-DR expression: a multicenter standardized study. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2341–2347. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orozco H, Arch J, Medina-Franco H, Pantoja JP, Gonzalez QH, Vilatoba M, Hinojosa C, Vargas-Vorackova F, Sifuentes-Osornio J. Molgramostim (GM-CSF) associated with antibiotic treatment in nontraumatic abdominal sepsis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Surg. 2006;141:150–153. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meisel C, Schefold JC, Pschowski R, Baumann T, Hetzger K, Gregor J, Weber-Carstens S, Hasper D, Keh D, Zuckermann H, et al. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to reverse sepsis-associated immunosuppression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:640–648. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0363OC. Biomarker-guided (mHLA-DR) clinical trial testing immunoadjuvant therapy (GM-CSF) in sepsis.

- 40.Turina M, Dickinson A, Gardner S, Polk HC., Jr Monocyte HLA-DR and interferon-gamma treatment in severely injured patients--a critical reappraisal more than a decade later. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammad RA. Use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1238–1245. doi: 10.2146/ajhp090325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall MW, Knatz NL, Vetterly C, Tomarello S, Wewers MD, Volk HD, Carcillo JA. Immunoparalysis and nosocomial infection in children with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2088-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, Volk HD, Kox W. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–681. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacLean LD, Meakins JL, Taguchi K, Duignan JP, Dhillon KS, Gordon J. Host resistance in sepsis and trauma. Ann Surg. 1975;182:207–217. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197509000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venet F, Davin F, Guignant C, Larue A, Cazalis MA, Darbon R, Allombert C, Mougin B, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, et al. Early Assessment of Leukocyte Alterations at Diagnosis of Septic Shock. Shock. 2010;34:358–363. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181dc0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hotchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:813–822. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venet F, Foray AP, Villars-Mechin A, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Lepape A, Monneret G. IL-7 restores lymphocyte functions in septic patients. J Immunol. 2012;189:5073–5081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Veerdonk FL, Mouktaroudi M, Ramakers BP, Pistiki A, Pickkers P, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Deficient Candida-specific T-helper 17 response during sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1798–1802. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boomer JS, Shuherk-Shaffer J, Hotchkiss RS, Green JM. A prospective analysis of lymphocyte phenotype and function over the course of acute sepsis. Crit Care. 2012;16:R112. doi: 10.1186/cc11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guignant C, Lepape A, Huang X, Kherouf H, Denis L, Poitevin F, Malcus C, Cheron A, Allaouchiche B, Gueyffier F, et al. Programmed death-1 levels correlate with increased mortality, nosocomial infection and immune dysfunctions in septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R99. doi: 10.1186/cc10112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venet F, Filipe-Santos O, Lepape A, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Grives A, Plantier N, Pasqual N, Monneret G. Decreased T cell repertoire diversity in sepsis: a preliminary study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:111–119. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182657948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venet F, Chung CS, Monneret G, Huang X, Horner B, Garber M, Ayala A. Regulatory T cell populations in sepsis and trauma. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:523–535. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hotchkiss RS, Opal S. Immunotherapy for sepsis--a new approach against an ancient foe. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:87–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1004371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517–2519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1205943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lundstrom W, Fewkes NM, Mackall CL. IL-7 in human health and disease. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Unsinger J, Kazama H, McDonough JS, Griffith TS, Hotchkiss RS, Ferguson TA. Sepsis-induced apoptosis leads to active suppression of delayed-type hypersensitivity by CD8+ regulatory T cells through a TRAIL-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2010;184:6766–6772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unsinger J, Burnham CA, McDonough J, Morre M, Prakash PS, Caldwell CC, Dunne WM, Jr, Hotchkiss RS. Interleukin-7 ameliorates immune dysfunction and improves survival in a 2-hit model of fungal sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:606–616. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Annane D. Improving clinical trials in the critically ill: unique challenge--sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:S117–S128. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318192078b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]