Abstract

Streptococcal pathogens have evolved to express exoglycosidases, one of which is BgaC β-galactosidase, to deglycosidate host surface glycolconjucates with exposure of the polysaccharide receptor for bacterial adherence. The paradigm BgaC protein is the bgaC product of Streptococcus, a bacterial surface-exposed β-galactosidase. Here we report the functional definition of the BgaC homologue from an epidemic Chinese strain 05ZYH33 of the zoonotic pathogen Streptococcus suis. Bioinformatics analyses revealed that S. suis BgaC shared the conserved active sites (W240, W243 and Y454). The recombinant BgaC protein of S. suis was purified to homogeneity. Enzymatic assays confirmed its activity of β-galactosidase. Also, the hydrolysis activity was found to be region-specific and sugar-specific for the Gal β-1,3-GlcNAc moiety of oligosaccharides. Flow cytometry analyses combined with immune electron microscopy demonstrated that S. suis BgaC is an atypical surface-anchored protein in that it lacks the “LPXTG” motif for typical surface proteins. Integrative evidence from cell lines and mice-based experiments showed that an inactivation of bgaC does not significantly impair the ability of neither adherence nor anti-phagocytosis, and consequently failed to attenuate bacterial virulence, which is somewhat similar to the scenario seen with S. pneumoniae. Therefore we concluded that S. suis BgaC is an atypical surface-exposed protein without the involvement of bacterial virulence.

Streptococcus suis serotype 2 (S. suis 2, SS2) is recognized as a serious swine pathogen that also frequently leads to the opportunistic human infections clinically featuring with meningitis, septicemia, arthritis, etc1,2,3. S. suis infections have been recorded in over 30 countries and/or regions, and claimed for no less than 850 human cases worldwide, some of which are lethal infections1,4. Of particular note, two big-scale endemics of human SS2 infections had ever occurred in China in 1998 and 2005, and a new disease form, streptococcal toxic shock-like syndrome (STSS) appeared in the SS2-infected patients5,6. Unfortunately, the molecular mechanism underlying STSS remains fragmentary or limited. Sporadic cases of human SS2 infections were also recorded in China1,7. In addition to the known virulence factors like capsule polysaccharide (CPS)8,9, suilysin10,11,12, muraminidase released-protein (MRP)13,14, etc., a collection of new virulence determinants have been elucidated that are grouped as follows15: 1) transcription factors (such as catabolite control protein A CcpA8,16, Rgg regulator17, zinc uptake regulator (Zur)18,19 and ferric uptake regulator (Fur)18); 2) the two component system (such as salK-salR20, virR-virS21, ciaR-ciaH22 and ihk-ihr23); 3) enzymes involved in central metabolisms (e.g., Glutamine synthetase (GlnA)24, enolase25, peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase (PgdA)26, sialic acid synthesis-associated enzymes NeuB27 & NeuC28 and Inosine 5-monophosphate dehydrogenase (Impdh)29); 4) quorum sensing system (LuxS30,31; 5) surface-exposed proteins (HP27232, SAO protein33,34,35, HP01978,36,37, etc.). It seemed likely that we have in part delineated the pathogenesis of S. suis infections.

Efficient adherence to host cells is critical for Streptococcal successful infections. In general, a collection of bacterial secreted and/or surface-anchored enzymes have been suggested to participate into this process38. In the case of S. pneumoniae, at least three types of exoglycosidases that included NanA (neuraminidase)39, BgaA & BgaC (β-galactosidase)38,40 and StrH (N-acetylglucosaminidase)39 are sequentially involved in the deglycosidation of host surface glycoconjugates for exposure of its preferred host oligosaccharide receptor39,40. Similar to the scenario observed with S. pneumoniae, the closely relative S. suis is also supposed to encounter a variety of glycoconjugates on the infected host cell surface (e.g., Mucin)38,41, and might evolve the similar strategy. However this hypothesis required further experimental validation.

β-galactosidase widespread in almost three domains of life, are a group of enzymes (EC3.2.1.23) with ability to catalyze the hydrolysis/release of the terminal non-reducing galactose from the oligosaccharides. The paradigm version of this family is E. coli lacZ product, which is a large/soluble polypeptide of 1024 amino acids/residues (~120 kDa) (http://www.ecogene.org/old/geneinfo.php?eg_id=EG10527) and required for lactose utilization. By contrast, S. pneumoniae BgaA is a typical surface-displayed β-galactosidase in that it is featuring “LPXTG” surface-anchoring motif. However, the other β-galactosidase BgaC of this organism might be atypical surface-associated protein without any known surface indicators/signals38. Very recently, structural study of BgaC pointed out its solution structure of a dimer and dissected its catalytic mechanism41.

As anticipated, the genomic analyses of S. suis 05ZYH33 strain discovered a bgaC homologue (SSU0449) (Fig. 1). Given its unique biological properties and important relevance of BgaC protein in the counterpart microorganism S. pneumoniae, we thereby employed integrative approaches (ranging from bioinformatics, biochemistry, bacterial genetics, infection/immunology to bacterial pathogenesis) to systemically investigate the S. suis BgaC protein.

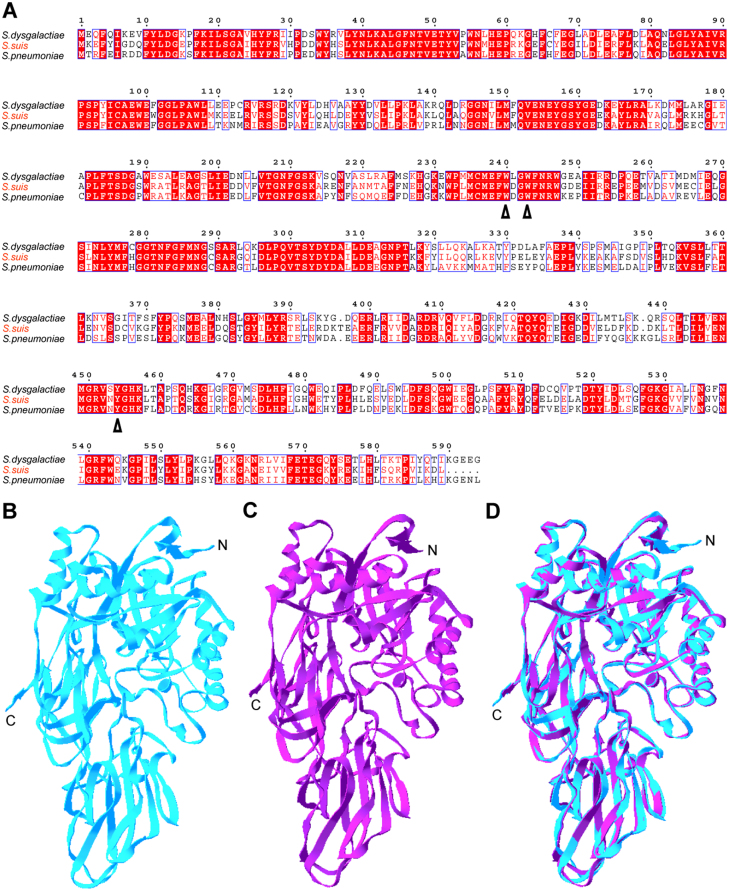

Figure 1. Bioinformatics analyses of the BgaC proteins.

(A). Multiple sequence alignments of BgaC homologues from three Streptococcus species. The amino acid sequences of three BgaC proteins used here are derived from S. pneumoniae (ABJ55509), S. suis 05ZYH33 (YP_001197815.1), and S. dysgalactiae (CCI62219.1), respectively. Identical residues are indicated with white letters on a red background, similar residues are red letters on white, varied residues are in black letters, and dots represent missing residues. Three residues that are critical for enzymatic activity (240W, 243W & 454Y) are highlighted with arrows. (B). Ribbon representation of the known structure of S. pneumoniae BgaC protein. (C). The modelled structure of S. suis BgaC homologue. (D). Structure superposition of S. suis BgaC with the counterpart of S. pneumoniae The structure of S. pneumoniae BgaC (PDB: 4E8D) is in blue, whereas that of S. suis BgaC is in purple. Designations: N, N-terminus; C, C-terminus.

Results

Discovery of a BgaC homologue from S. suis

The annotation for functional genome of S. suis 05ZYH33, an epidemic Chinese strain, assigned the 05SSU0449 locus as the putative bgaC whose protein product belongs to the β-galactosidase sub-clade of the glycosyl hydrolase family 35. Multiple sequence alignments of 05SSU0449-encoding product with the prototypical BgaC encoded by S. pneumoniae revealed 1) the overall similarity is 63%; 2) the N-terminus of BgaC protein is pretty conserved, whereas the C-terminus differs quite bit; 3) they shared the three identical residues for catalytic activity (240W, 243W & 454Y) (Fig. 1A). Of particular note, the modeled tertiary structure of S. suis BgaC (Fig. 1C) is almost identical to that of the paradigm member from S. pneumoniae (Fig. 1B) in that the perfect matched architectures are visualized through structural superposition (Fig. 1D). Also, S. suis bgaC has a pool of active transcripts revealed by our RT-PCR experiments (not shown). We therefore speculated that S. suis bgaC is a functional homologue (Fig. 1). This required further experimental validation.

S. suis BgaC has the activity of β-galactosidase

To gain preliminary glimpse of enzymatic/biochemical aspects, we prepared the recombinant form of the S. suis BgaC protein. The N-terminal 6XHis tagged BgaC was overexpressed in E. coli system and purified through nickel column-based affinity chromatography, and the purity was further judged by 12% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). As expected, the molecular weight of the acquired protein is about 63 kDa (Fig. 2A), which is in much consistency with the scenario seen with Western blot using anti-BgaC mouse sera. Of note, Maldi-Toff spectrometry-based determination proved the identity of the recombinant BgaC protein we obtained (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Purification, identification and enzymatic characterization of the recombinant BgaC protein.

(A). 12% SDS-PAGE profile of the purified BgaC protein of S. suis The expected protein is indicated with an arrow. “M” is the abbreviation for protein molecular weight. The numbers on left hand represent protein size (kDa). (B). Western blotting analyses for the recombinant BgaC protein. (C). Enzymatic parameters determined for the BgaC β-galactosidase. The protocol used to measure the activity of β-galactosidase is found in section of Materials and Methods. Designations: Km, Michaelis constant; Vm, The maximum rate; Kcat: a rate constant. (D). MS-based identification of the recombinant BgaC protein. The tryptic peptides identified to match the BgaC sequence are given in underlined type.

Subsequently, the recombinant BgaC protein was subjected to β-galactosidase assays with pNPG as the substrates. We found that the optimal temperature, optimal reaction time and optimal pH of this enzyme is 42°C, 30 min, and 5.5, respectively (not shown). Additionally, the optimal concentration for the substrate pNPG is 10 mM (not shown). On the basis of the above enzymatic reaction conditions we optimized, the S. suis BgaC was proved to obviously possess the activity of β-galactosidase with Km of 0.398 mM, Kcat of 5.63 × 102/s and Vm7.43 × 10−3 mM/min (Fig. 2C). It seemed likely that our structure-guided prediction in this case is correct (Fig. 1).

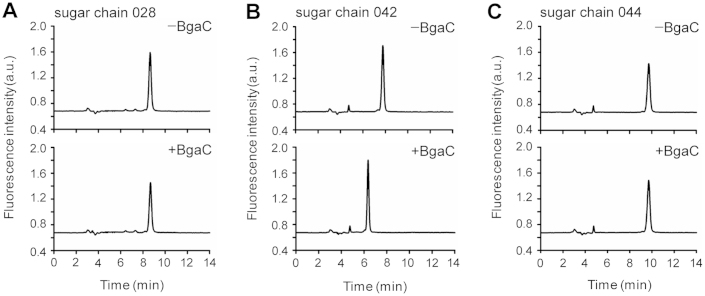

Linkage specificity of S. suis BgaC hydrolysis activity

To further elucidate the linkage specificity of S. suis BgaC-mediated hydrolysis activity, we compared three kinds of amino pyridine (PA)-tagged sugar chains as substrates used in our set-up hydrolysis reactions as Jeong et al. reported38 with little change. These sugar chains included 028 (asialo GM1-tetrasaccharide), 042 (lacto-N-tetraose) and 044 (lacto-N-fucopentaose II) (Table 2). Subsequently, HPLC was adopted to determine whether S. suis BgaC was able to liberate galactose moiety from the above tested substrates tested. Obviously, BgaC treatment failed to give any position-shift for the peaks of HPLC chromatogram of either PA-labeled sugar chain 028 (Fig. 3A) or PA-labeled sugar chain 044 (Fig. 3C). By contrast, elution time of the specific peak is changed for the PA-labeled sugar chain 042 upon the BgaC treatment; (Fig. 3B). It suggested that S. suis BgaC specifically cleaves Galβ1-3GlcNAc group containing sugar chain 042, while not hydrolyze group containing Gal β1–3 GalNAc sugar chain 028 and Gal β1–3 GlcNAc terminally modified sugar chain 044 (Table 2).

Table 1. Bacterial strains, plasmid, and cell lines used in this study.

| Strains, plasmids or cell lines | Characteristicsa | Refs or Origin |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | The cloning host | Promega |

| BL21 | The expression host | Promega |

| S. suis 2 | ||

| 05ZYH33 | An epidemic Chinese strain of S. suis 2 | 19,49,19,49 |

| ΔbgaC | 05ZYH33 with the inactivated bgaC gene, SpcR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSET2 | E. coli-S. suis shuttle vector, SpcR | 44 |

| pET28a | T7-driven expression vector, KanR | Promega |

| pMD18-T | Cloning vector, AmpR | Takara |

| pUC18 | Cloning vecter, AmpR | Takara |

| Cell lines | ||

| Raw 264.7 | Macrophage cell from mice | ATCC TIB-71 |

| Hep-2 | Larynx carcinoma epithelial cell | CCTCC GDC004 |

aSpcR, spectinomycin resistance; AmpR, ampicillin resistance; KanR, kanamycin resistance.

Table 2. Hydrolysis of terminal galactose of various sugar chains by BgaC.

| Sugar chain | Structure | Hydrolysisa |

|---|---|---|

| Lacto-N-tetraose (PA-sugar chain 042) | Gal β1–3 GlcNAc β1–3 Gal β1–4 Glc-PA | + |

| Asialo GM1-tetrasaccharide (PA-sugar chain 028) | Gal β1–3 GalNAc β1–4 Gal β1–4 Glc-PA | − |

| Lacto-N-fucopentaose II (PA-sugar chain 044) | Gal β1–3 GlcNAc β1–3 Gal β1–4 Glc-PA4\1 α Fuc | − |

a50 pmol of each substrate was incubated with 1.6 mU BgaC or in a 50 ul reaction mixture (1× PBS, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT) for 20 h at 30°C. Release of the terminal galactose from substrates was analyzed by HPLC. The sugar chains 028, 042 and 044 were purchased from Takara (Japan).

Figure 3. HPLC analyses for hydrolysis products of polysaccharides by S. suis BgaC enzyme.

(A). HPLC profile of PA-labeled sugar chain 028 with or without treatment of the recombinant S. suis BgaC protein. (B). HPLC test of PA-labeled sugar chain 042 following the S. suis BgaC protein-mediated hydrolysis. (C). HPLC assay for PA-labeled sugar chain 044 after the hydrolysis by the S. suis BgaC β-galactosisdase. Minus: without addition of the BgaC protein; plus: addition of the BgaC protein. Designations: a.u., arbitrary units.

S. suis BgaC is a surface-exposed protein

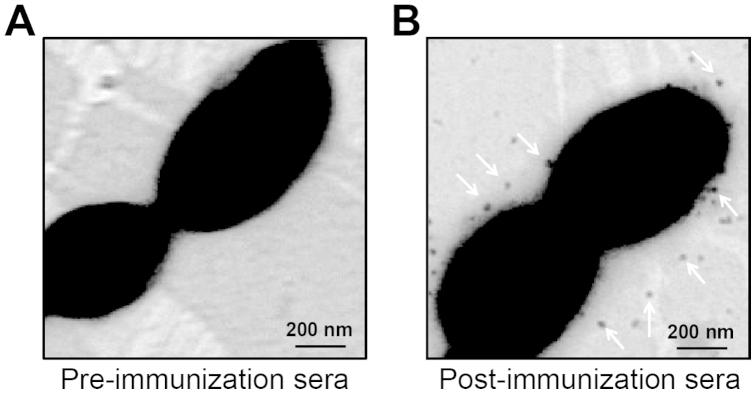

Two different approaches (one is the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, the other is immune electro-microscopy) were applied to assay the subcellular location of BgaC on S. suis (Fig. 4 & 5). FACS analyses suggested that the unlabeled SS2 is distributed normally (Fig. 4A) with a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) close to that of the labeled SS2 treated with mouse pre-immunization serum (Fig. 4B and 4C). However, the result in flow diagram is clear that the peaks shifted to the right upon treatment with the mouse anti-BgaC post-immunization serum (Fig. 4D). In fact, the MFI of bacteria treated with the mouse anti-BgaC post-immune serum was about 3-fold higher than the pre-immune mouse serum treated with a negative control group (Fig. 4E). In contrast to the negative control in which the pre-immunization sera were involved (Fig. 5A), immune-gold assays elucidated that BgaC protein particles are visualized on bacterial cell surface of S. suis with treatment of the post-immunization sera (Fig. 5B). Given that the above combined results are quite similar to our earlier observation with the surface-localized enolase25, we concluded that S. suis BgaC does act as a surface-anchored protein with the activity of β-galactosidase.

Figure 4. Surface localization of the S. suis BgaC protein.

(A). which suggests that the unlabeled bacteria can form a group suitable for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-base analyses. (B). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the unlabeled bacteria. (C). MFI of S. suis treated with mouse pre-immune sera. (D). MFI of S. suis treated with mouse anti-BgaC sera. (E). Contrasting MFI of S. suis treated with mouse anti-BgaC sera (Panel D) to that with treatment of pre-immune sera (Panel C). Statistical analyses were performed by using a Student t test. *P-value was <0.05.

Figure 5. Immune electron microscopy-based analyses of the BgaC protein.

The BgaC protein is visulized to display on bacterial cell surface of S. suis 2 using the post-immunization sera (Panel B), whereas not using the pre-immunization sera (Panel A).

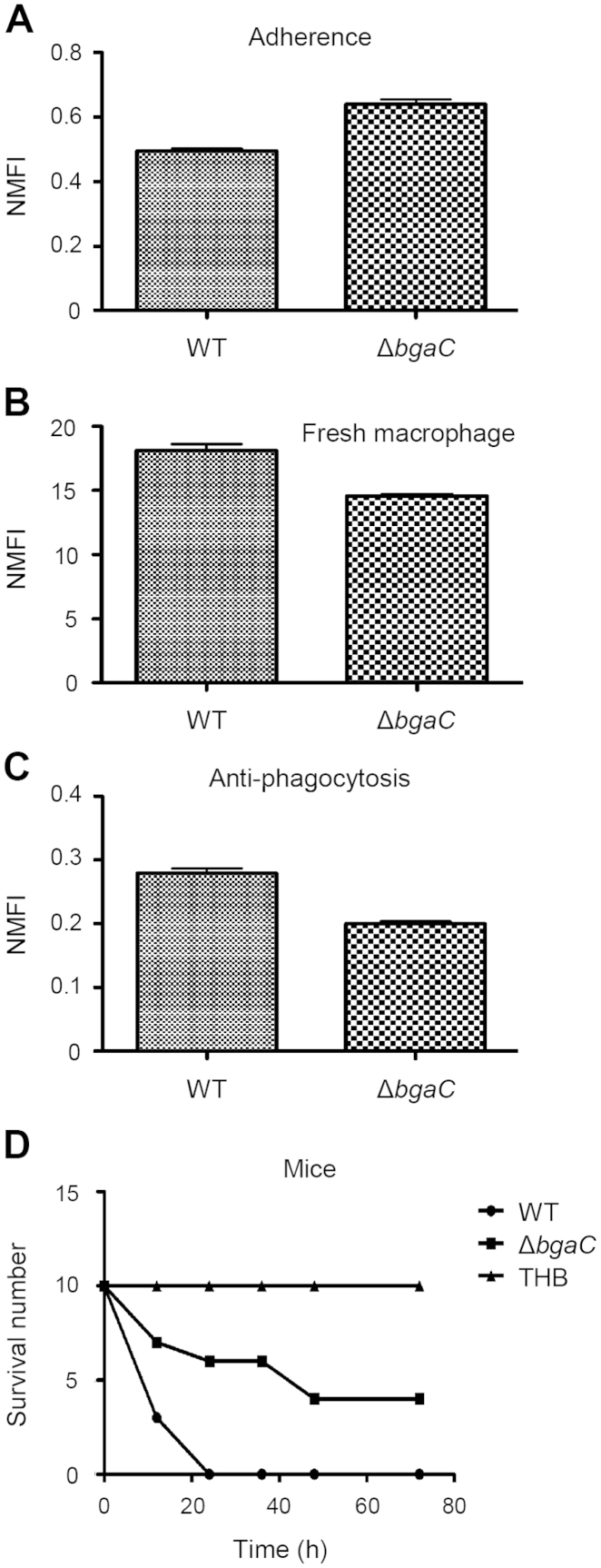

S. suis BgaC plays no detectable roles in bacterial pathogenesis

To probe possible roles of the bgaC gene in S. suis infection, we constructed the ΔbgaC mutant and compared its phenotype with that of the wild type strain 05ZYH33 (Fig. 6). The cell tests conducted here were based on both Hep-2 cell line (Fig. 6A) and RAW264.7 macrophage (Fig. 6C). No significant effect on bacterial adherence to Hep-2 cell line was observed between the ΔbgaC mutant and its parental strain 05ZYH33 (Fig. 6A). Similarly, the disruption of bgaC gene failed to exert obvious effects on ability of bacterial anti-phagocytosis (Fig. 6B and C).

Figure 6. No apparent role of S. suis BgaC in bacterial pathogenesis.

(A). Comparison of bacterial adherence capability of the ΔbgaC mutant with the wild type strain 05ZYH33. Hep-2 cells were applied here. Data shown here are means ± SD of intracellular bacteria/ml. (B). Evaluation of anti-phagocytosis ability of S. suis strains by fresh macrophages RAW264.7. (C). anti-phagocytosis of S. suis strains by RAW264.7 macrophages. Intracellular bacteria were recovered from cell lysates in 1 h post-infection. The results are expressed as means ± SD of recovered bacteria/ml. (D). Evaluation of role of S. suis BgaC in bacterial virulence using mice infection model. Statistical analyses were performed by using a Student t test. No statistically significant differences were considered.

Mice infection assays were further adopted to address the contribution of the bgaC gene to bacterial virulence (Fig. 6D). All the mice infected with the wild type strain 05ZYH33 were sick within 24 hours, most of which died (Fig. 6D). By contrast, mice of the negative control group inoculated with THB all survived (Fig. 6D). Most of mice infected with the ΔbgaC mutant died within two days. It seemed likely that no significant difference between WT and the ΔbgaC mutant in S. suis pathogenicity, which is consistent with scenarios observed in cell lines-based experiments (Fig. 6A–C). Thus we believed that S. suis BgaC has no roles in bacterial virulence, which is in agreement with that of S. pneumoniae38.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our findings might represent/provide the integrative evidence that the zoonotic pathogen S. suis is a second paradigm organism in which the bgaC gene encoded an atypical surface-exported protein with the essence of β-galactosidase38. Unlike another surface-displayed exoglycosidase BgaA39,40, it seemed likely that the BgaC exoglycosidase of both S. pneumoniae38 and S. suis (Fig. 5) does not significantly contribute to bacterial virulence. It remains possible that BgaC might augment the critical roles of other known three relevant surface exoglycosidases (NanA, BgaA & StrH) in Streptococcal infections39, but required extensive evidence. We also noted that the bgaC gene is widespread in almost 35 serotypes of S. suis pathogens (not shown), suggesting that it is very conserved exoglycosidase-encoding gene. The presence of BgaC-type β-galactosidase in Streptococcus species might be anticipated to reflect the consequence for long-term of Streptococcus with its host niche. The reason lied in that the physiological advantage that bacteria acquired is exploiting BgaC-mediated deglycosidation of host cell surface glycolconjucates to partialy facilitate exposing the polysaccharide receptor for efficient bacterial adherence38,39,40,41.

Given the fact that both the flow cytometry-based assay and the immune electron microscopy-aided visualization illustrated that S. suis BgaC is localized on bacterial surface (Fig. 4 and 5), although it lacks the typical “LPXTG” motif for classic surface proteins (Fig. 1), we thereby believed that S. suis BgaC acts as an atypical surface protein. In particular, the integrative evidence from cell lines and mice-based experiments clearly showed that the disruption of bgaC does not significantly exert any effect on the abilities of bacterial adherence and anti-phagocytosis, and consequently failed to attenuate bacterial virulence, which is somewhat similar to the scenario seen with S. pneumoniae.

Interestingly, HPLC-based analyses for hydrolysis products of oligosaccharides revealed clearly that S. suis BgaC exhibits the region-specific and sugar-specific hydrolysis activity for the Gal β-1,3-GlcNAc moiety of oligosaccharides (Table 2 and Fig. 3). This observation is much consistency with scenario seen with the paradigm BgaC of S. pneumoniae38. Apparently, it suggested the functional conservation/selectivity of BgaC protein from different microorganisms, and might point out its limited capability (not promiscuous) to deglycosidate host surface glycolcongugates, which is probably due to selection pressure during the process of host-pathogen co-evolution/interaction.

The future research directions regarding to the BgaC protein lied in the following three aspects: 1) given the fact that pneumococcal and S. suis BgaC protein are surface-displayed, we expect to extend our analyses to other Streptococcus species (e.g., S. dysgalactiae, Fig. 1A), which might delineate a common scenario for cell biology of BgaC protein; 2) we are planning to examine if it is a good antigen with potential to develop into a diagnostic antigen for laboratory/field detection for S. suis infection. We had ever obtained the similar success in the cases of SAO protein34 and enolase enzyme25; 3) to further our understanding of the catalysis mechanism/substrate specificity of BgaC, we are quite interested in resolving the crystal structures of BgaC alone and/or its complex with substrate by employing X-ray crystallography41.

In summary, BgaC protein as a new member is assigned to a family/list of surface proteins from the zoonotic pathogen S. suis. Similar to the scenario seen with its counterpart of S. pneumonia, it is not obviously involved in bacterial virulence.

Methods

Bacterial strains, cells and growth conditions

The bacterial strains, plasmids and cell lines used here are listed in Table 1.The S. suis 2 strains were maintained on both Todd-Hewitt broth (THB; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) agar and THB liquid media at 37°C. When required, 5% (vol/vol) sheep blood is supplemented. Escherichia coli DH5α and BL21 (DE3) separately served as the gene cloning host and the protein expression host, which were routinely kept in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth agar and/or liquid media or plated on LB agar at 37°C overnight. All the antibiotics were purchased from Sigma and were used as follows: Spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml for S. suis; Ampicillin, 100 μg/ml for E. coli and Kanamycin, 50 μg/ml for E. coli.

Two types of cell lines used here separately included the human laryngeal epithelial cell Hep-2 (CCTCC GDC004) and the mouse macrophagocyte Raw 264.7 (ATCC TIB-71, Rockville, MD, USA) (Table 1). As we earlier described27, they were cultivated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Roche),100 μg/ml gentamycin and 5 μg/ml penicillin G.

Expression and purification of BgaC protein

The recombinant plasmid pET28a-bgaC was transformed into BL21 (DE3) to produced 6XHis tagged BgaC protein. When the cell optical density at the wave-length of 600 nm (OD600) reached around 0.8, 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added for induction at 16°C overnight. The overexpressed BgaC protein was released by sonication and was purified through the nickel column. The purity was further verified by 12% SDS-PAGE.

Liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

The identity of the recombinant BgaC protein was directly confirmed using A Waters Q-Tof API-US Quad-ToF mass spectrometer linked to a Waters nano Acquity UPLC as we performed earlier42. The de-stained gel slice of interest was digested with 25 μl of Sequencing Grade Trypsin (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, 12.5 ng μl−1 in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate) and the resultant peptides were extracted with 50% acetonitrile containing 5% formic acids. The mass spectrometer was applied for data acquisition and Waters Protein Lynx Global Server 2.2.5, Mascot (Matrix Sciences) combined with BLAST against NCBI nr database were subjected for data analysis43.

Western blot

BgaC protein was also verified by Western blot. The protein samples were separated with 12% SDS-PAGE and thereafter transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Sera of anti-BgaC collected from different specific pathogen-free (SPF) mice were used as the primary antibody, the secondary antibody was a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Biosynthesis). The reacting bands were visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine(DAB).

β-galactosidase assays

The β-galactosidase activity of the purified BgaC enzyme (3 μg/reaction) was assayed in the phosphate reaction buffer (1× PBS, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl-β-galactopyranoside (pNPG), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DL-Dithiothreitol, pH 5.5) as Jae et al. reported38. The Reactions were stopped by adding 500 ul sodium carbonate solution (1 M), and the amount of p-nitrophenol (PNP) released was determined by measuring the optical absorbance at 410 nm.

Linkage specificity assays

To determine the linkage specificities of BgaC, enzyme activities were assayed with the sugar chains listed in Table 2. Each 50-pmol 2-pyridylamine(PA)-labeled glycan was reacted with 1.6 mU BgaC in a 50 ul reaction mixture (1 × PBS, 10 mM MgCl2,10 mM DTT) for 20 h at 30°C. Release of terminal galactose from specific sugar was detected by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Agilent 1100 series). After the reaction, protein was removed with Microcon YM-10 (Millipore) and the product was analyzed using an HPLC device connected to a model 1321A multi-fluorescence detector (Agilent) with an Athena NH2, 120A, column (4.6 by 250 mm; ANPEL, China). Product sugar chains were separated by an isocratic mobile phase (200 mM acetic acid-triethylamine [pH 7.3]-acetonitrile [35:65, vol/vol]) with a 1 ml/min flow rate38.

Flow cytometry (FCM)-based analyses

As we described earlier25 with minor changes, FCM was conducted to examine the sub-cellular localization of BgaC on S. suis cells. Briefly, the overnight cultures of S. suis 05ZYH33 were harvested by the centrifugation at 8000 g. Then the bacteria were washed with 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.4), adjusted to 108 CFU/ml, and incubated with mouse anti-BgaC sera or pre-immune sera for 1 h at 4°C. Finally, bacterial cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and examined using a flow cytometer, following the 1 h of incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Sigma).

Immune electron microscopy

Overnight culture of S. suis 05ZYH33 grown in THB media (~5 ml) was pelleted by spinning and re-suspended in 500 μl of PBS (pH 8.0). 20 μl of the bacterial suspension was placed on nickel-Formvar grids (EMCN, Beijing, China) and partially air-dried. The bacteria were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 10 min. After being blocked for 30 min with 10% normal donkey serum in dilution buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin) plus 1% Tween 20, pH 8.0), the grids were soaked in 50 ul of mouse anti-BgaC sera (or pre-immunization sera, in 25× dilution) for 1 h at room temperature (RT). After three rounds of washes with PBS-1% Tween 20, the grids were transferred to 50 μl of 15 nm gold-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Beijing Biosynthesis Biotechnology Co., Ltd) diluted 1/30 in dilution buffer, and incubated at RT for 1 h. Following five rounds of washes with PBS-1% Tween 20 plus one round of washing with distilled water, the bacterial samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and examined with an H7650 electron microscope (Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV.

Construction of the ΔbgaC mutant of S. suis

A spectinomycin resistance (SpcR) cassette was designed to disrupt into the bgaC gene of S. suis 2 strain 05ZYH33 via homologous recombination19. First, the SpcR cassette amplified from pSET244 was cloned into the pUC18 vector (Promega) to give the intermediate plasmid pUC18-Spc (Table 1), and then the two DNA fragments (LA and RA) flanking the bgaC gene were separately inserted into the pUC18-Spc vector, giving the knockout plasmid pUC::bgaC (Table 1). Second, the pUC::bgaC plasmid was electroporated into the competent cells of S. suis 05ZYH33 as we described before20 to acquire the transformants with Spectinomycin resistance. Finally, the multiplex-PCR technique combined with RT-PCR was utilized to screen confirm the candidate ΔbgaC mutant (Table 3), which was further verified by direct DNA sequencing analyses.

Table 3. Primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequences (5′--3′)a |

|---|---|

| LA1 | GAGCTCTCTTCGGCTTCGTTTCCTAGGC |

| LA2 | GGATCCGGATGGACACGAAAATAATGAA |

| RA1 | GTCGACTTTGGTTTCATGAATGGTTGCT |

| RA2 | GCATGC ATCAAACGACCATCAATACGCG |

| Spc1 | CCGGATCCGTTCGTGAATACAT |

| Spc2 | CGGTCGACGTTTTCTAAAATCTGA |

| Check1 | GTCCCCCTATATTTGTGCTGAGTG |

| Check2 | GAGTGGCCAATTCTTCTGATGTTC |

| Out1 | GCTAGAGCGGACCAGTTTCGT |

| Out2 | CATCGATAACCATGATACGACCG |

| bgaC-F1 | GGATCCCGGAGGAAGAAATGAAAG |

| bgaC-R1 | GGTCGACCAAGTCTTTTATAACGGG |

aThe underlined sequences are the restriction sites.

Cell assays for bacterial adherence and phagocytosis

The grown S. suis bacteria (WT & ΔbgaC) were processed as Hytönen and coworkers described45. The two different cell lines used here included Hep-2 (human laryngeal epithelial cell line) and murine macrophage Raw 264.7 cells27. Hep-2 cell line is used to evaluate bacterial adherence whereas the Raw264.7 cells are tested to address its ability of anti-phagocytosis. Cell cultivations-based analyses were conducted as we recently reported27.

Mice infections

BALB/c (4-week old, female) mice were challenged with S. suis strains (WT & ΔbgaC mutant) at a dose of 109 CFU per mouse. THB was used as a negative control. Totally, three groups were involved, each of which included 10 mice. Clinical syndromes of the infected mice were monitored for two weeks. Of particular note, deaths were recorded and moribund animals were humanely killed. All experiments on live vertebrates in this study were approved by Ethics Committee of Research Institute for Medicine of Nanjing Command and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations27,30.

Bioinformatics, structural and statistical analyses

The protein sequences of BgaC homologues of different organisms were derived from S. dysgalactiae, S. pneumoniae, and S. suis, respectively. The multiple alignments were conducted using ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html), and the resultant output was processed by program ESPript 2.2 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi)46,47,48. The structure of S. suis BgaC homologue was modelled through CPHmodels 3.0 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CPHmodels), and superimposed with the known structure of S. pneumoniae BgaC.

All assays were carried out in triplicate at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed by using a Student t test. Differences were considered statistically significant when the calculated P value was <0.05.

Author Contributions

Y.F., C.W., D.H. and F.Z. conceived and designed this project and experiments. D.H., F.Z., Y.F., H.Z., L.H., X.G., M.G., M.C. and F.Z. performed the experiments and contributed to the development of the figures and tables. Y.F., D.H., C.W., H.Z., J.Z., X.P. and J.T. analyzed the data. Y.F., C.W., H.Z. and D.H. wrote this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the start-up package of Zhejiang University (Youjun Feng), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31170124, 81371768, 81172794 and 31300119), National S&T Project for Infectious Diseases Control (grants 2013ZX10004-103, 2013ZX10004-203 and 2013ZX10004-218), Key Project of the Military Twelfth Five-Year Research Program of PLA (grants AWS11C001 and AWS11C009), Key Technology R&D Program of Jiangsu Province, China (grants BE2012609 and BE2013603). Dr. Feng is the recipient of “Young 1000 Talents” Award.

References

- Feng Y., Zhang H., Ma Y. & Gao G. F. Uncovering newly emerging variants of Streptococcus suis, an important zoonotic agent. Trends Microbiol 18, 124–31 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittipaldi N., Segura M., Grenier D. & Gottschalk M. Virulence factors involved in the pathogenesis of the infection caused by the swine pathogen and zoonotic agent Streptococcus suis. Future Microbiol 7, 259–79 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M., Segura M. & Xu J. Streptococcus suis infections in humans: the Chinese experience and the situation in North America. Anim Health Res Rev 8, 29–45 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Streptococcus suis in Omics-Era: Where Do We Stand? J Bacteriol Parasitol S2–001, (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tang J. et al. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS Med 3, e151 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. et al. Human Streptococcus suis outbreak, Sichuan, China. Emerg Infec Dis 12, 914 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Recurrence of human Streptococcus suis infections in 2007: three cases of meningitis and implications that heterogeneous S. suis 2 circulates in China. Zoonoses Public Health 56, 506–14 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A. et al. HP0197 contributes to CPS synthesis and the virulence of Streptococcus suis via CcpA. PLoS One 7, e50987 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. E. et al. Identification and characterization of the cps locus of Streptococcus suis serotype 2: the capsule protects against phagocytosis and is an important virulence factor. Infect Immun 67, 1750–6 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. et al. Crystal structure of cytotoxin protein suilysin from Streptococcus suis. Protein Cell 1, 96–105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun S., Perez-Casal J., Connor W. & Willson P. J. Role of suilysin in pathogenesis of Streptococcus suis capsular serotype 2. Microb Pathog 34, 27–37 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. G. et al. Generation and characterization of a defined mutant of Streptococcus suis lacking suilysin. Infect Immun 69, 2732–5 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthelot-Herault F., Morvan H., Keribin A. M., Gottschalk M. & Kobisch M. Production of muraminidase-released protein (MRP), extracellular factor (EF) and suilysin by field isolates of Streptococcus suis capsular types 2, 1/2, 9, 7 and 3 isolated from swine in France. Vet Res 31, 473–9 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats J. J., Plattner B. L., Stewart G. C. & Changappa M. M. Presence of the Streptococcus suis suilysin gene and expression of MRP and EF correlates with high virulence in Streptococcus suis type 2 isolates. Vet Microbiol 70, 201–11 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Zhang H., Cao M. & Wang C. Regulation of virulence in Streptococcus suis. J Bacteriol Parasitol 3, e108 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Willenborg J. et al. Role of glucose and CcpA in capsule expression and virulence of Streptococcus suis. Microbiology 157, 1823–33 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F. et al. Contribution of the Rgg transcription regulator to metabolism and virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Infect Immun 79, 1319–28 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda J. et al. The cation-uptake regulators AdcR and Fur are necessary for full virulence of Streptococcus suis. Vet Microbiol 144, 246–9 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Functional definition and global regulation of Zur, a zinc uptake regulator in a Streptococcus suis serotype 2 strain causing streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. J Bacteriol 190, 7567–78 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. et al. SalK/SalR, a two-component signal transduction system, is essential for full virulence of highly invasive Streptococcus suis serotype 2. PLoS One 3, e2080 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. et al. Identification and proteome analysis of the two-component VirR/VirS system in epidemic Streptococcus suis serotype 2. FEMS Microbiol Lett 333, 160–8 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. The two-component regulatory system CiaRH contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis 2. Vet Microbiol 148, 99–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. et al. The two-component system Ihk/Irr contributes to the virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 strain 05ZYH33 through alteration of the bacterial cell metabolism. Microbiology 158, 1852–66 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si Y. et al. Contribution of glutamine synthetase to the virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Vet Microbiol 139, 80–8 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Streptococcus suis enolase functions as a protective antigen displayed on the bacterial cell surface. J Infect Dis 200, 1583–1592 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fittipaldi N. et al. Significant contribution of the pgdA gene to the virulence of Streptococcus suis. Mol Microbiol 70, 1120–35 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Attenuation of Streptococcus suis virulence by the alteration of bacterial surface architecture. Sci Rep 2, 710; 10.1038/srep00710 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecours M. P. et al. Sialylation of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 is essential for capsule expression but is not responsible for the main capsular epitope. Microbes Infect 14, 941–50 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. H. et al. Identification and characterization of inosine 5-monophosphate dehydrogenase in Streptococcus suis type 2. Microb Pathog 47, 267–73 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M. et al. Functional definition of LuxS, an autoinducer-2 (AI-2) synthase and its role in full virulence of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. J Microbiol 49, 1000–11 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang W., Wu Z., Zhu X. & Lu C. Functional analysis of luxS in Streptococcus suis reveals a key role in biofilm formation and virulence. Vet Microbiol 152, 151–60 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandanici F. et al. A surface protein of Streptococcus suis serotype 2 identified by proteomics protects mice against infection. J Proteomics 73, 2365–9 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Identification of a surface protein of Streptococcus suis and evaluation of its immunogenic and protective capacity in pigs. Infect Immun 74, 305–12 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Existence and characterization of allelic variants of Sao, a newly identified surface protein from Streptococcus suis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 275, 80–8 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Immunization with recombinant Sao protein confers protection against Streptococcus suis infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14, 937–43 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z. Z. et al. Molecular mechanism by which surface antigen HP0197 mediates host cell attachment in the pathogenic bacteria Streptococcus suis. J Biol Chem 288, 956–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A. et al. Identification of a surface protective antigen, HP0197 of Streptococcus suis serotype 2. Vaccine 27, 5209–13 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J. K. et al. Characterization of the Streptococcus pneumoniae BgaC protein as a novel surface β-galactosidase with specific hydrolysis activity for the Galbeta1-3GlcNAc moiety of oligosaccharides. J Bacteriol 191, 3011–23 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalia A. B., Standish A. J. & Weiser J. N. Three surface exoglycosidases from Streptococcus pneumoniae, NanA, BgaA, and StrH, promote resistance to opsonophagocytic killing by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 78, 2108–16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limoli D. H., Sladek J. A., Fuller L. A., Singh A. K. & King S. J. BgaA acts as an adhesin to mediate attachment of some pneumococcal strains to human epithelial cells. Microbiology 157, 2369–81 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng W. et al. Structural insights into the substrate specificity of Streptococcus pneumoniae beta(1,3)-galactosidase BgaC. J Biol Chem 287, 22910–8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. & Cronan J. E. Complex binding of the FabR repressor of bacterial unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis to its cognate promoters. Mol Microbiol 80, 195–218 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. A Francisella virulence factor catalyses an essential reaction of biotin synthesis. Mol Microbiol 91, 300–14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamatsu D., Osaki M. & Sekizaki T. Construction and characterization of Streptococcus suis-Escherichia coli shuttle cloning vectors. Plasmid 45, 101–13 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hytönen J., Haataja S. & Finne J. Use of flow cytometry for the adhesion analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes mutant strains to epithelial cells: investigation of the possible role of surface pullulanase and cysteine protease, and the transcriptional regulator Rgg. BMC microbiology 6, 18 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Xu J., Zhang H., Chen Z. & Srinivas S. Brucella BioR regulator defines a complex regulatory mechanism for bacterial biotin metabolism. J Bacteriol 195, 3451–67 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. & Cronan J. E. A new member of the Escherichia coli fad regulon: transcriptional regulation of fadM (ybaW). J Bacteriol 191, 6320–8 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. & Cronan J. E. Overlapping repressor binding sites result in additive regulation of Escherichia coli FadH by FadR and ArcA. J Bacteriol 192, 4289–99 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. et al. A glimpse of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome from comparative genomics of S. suis 2 Chinese isolates. PLoS One 2, e315 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]