Abstract

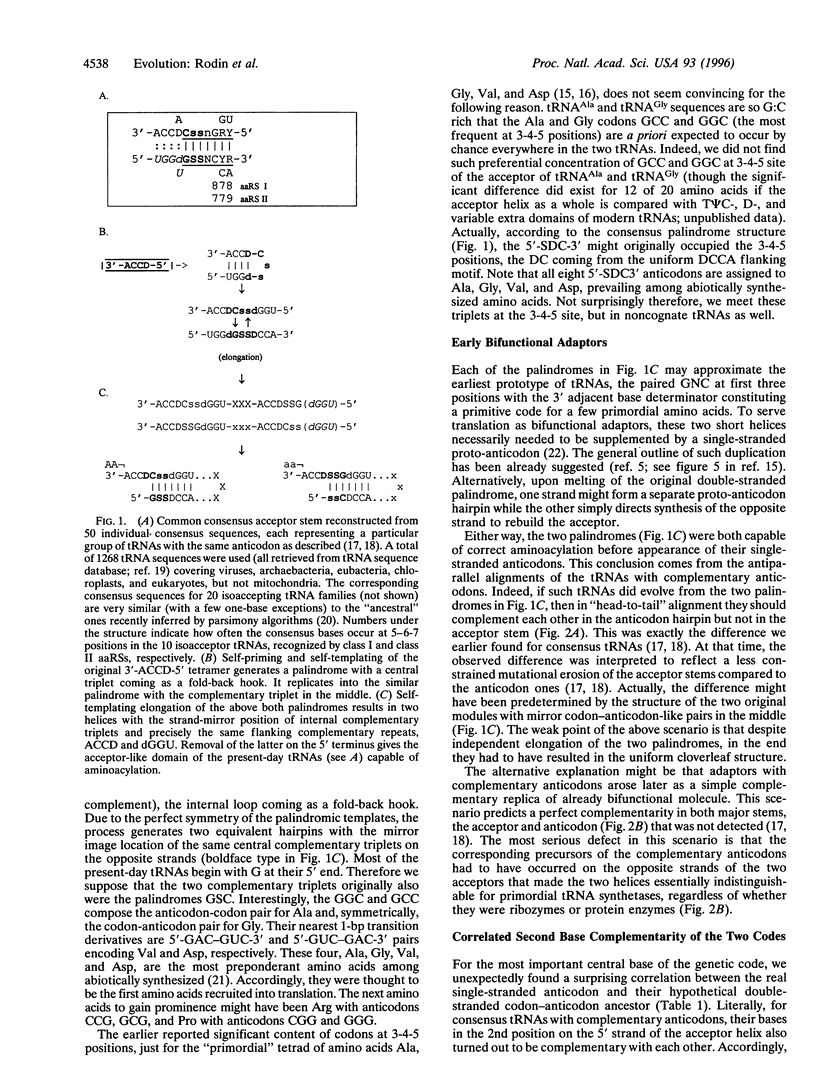

A total of 1268 available (excluding mitochondrial) tRNA sequences was used to reconstruct the common consensus image of their acceptor domains. Its structure appeared as a 11-bp-long double-stranded palindrome with complementary triplets in the center, each flanked by the 3'-ACCD and NGGU-5' motifs on each strand (D, base determinator). The palindrome readily extends up to the modern tRNA-like cloverleaf passing through an intermediate hairpin having in the center the single-stranded triplet, in supplement to its double-stranded precursor. The latter might represent an original anticodon-codon pair mapped at 1-2-3 positions of the present-day tRNA acceptors. This conclusion is supported by the striking correlation: in pairs of consensus tRNAs with complementary anticodons, their bases at the 2nd position of the acceptor stem were also complementary. Accordingly, inverse complementarity was also evident at the 71st position of the acceptor stem. With a single exception (tRNA(Phe)-tRNA(Glu) pair), the parallelism is especially impressive for the pairs of tRNAs recognized by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRS) from the opposite classes. The above complementarity still doubly presented at the key central position of real single-stranded anticodons and their hypothetical double-stranded precursors is consistent with our previous data pointing to the double-strand use of ancient RNAs in the origin of the main actors in translation- tRNAs with complementary anticodons and the two classes of aaRS.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bloch D. P., McArthur B., Mirrop S. tRNA-rRNA sequence homologies: evidence for an ancient modular format shared by tRNAs and rRNAs. Biosystems. 1985;17(3):209–225. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(85)90075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F. H. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968 Dec;38(3):367–379. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giulio M. The phylogeny of tRNAs seems to confirm the predictions of the coevolution theory of the origin of the genetic code. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 1995 Dec;25(6):549–564. doi: 10.1007/BF01582024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriani G., Cavarelli J., Martin F., Ador L., Rees B., Thierry J. C., Gangloff J., Moras D. The class II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their active site: evolutionary conservation of an ATP binding site. J Mol Evol. 1995 May;40(5):499–508. doi: 10.1007/BF00166618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriani G., Delarue M., Poch O., Gangloff J., Moras D. Partition of tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature. 1990 Sep 13;347(6289):203–206. doi: 10.1038/347203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q., Lambowitz A. M. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase binds specifically to the group I intron catalytic core. Genes Dev. 1992 Aug;6(8):1357–1372. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman H. Speculations on the origin of the genetic code. J Mol Evol. 1995 May;40(5):541–544. doi: 10.1007/BF00166623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfield J. J. Origin of the genetic code: a testable hypothesis based on tRNA structure, sequence, and kinetic proofreading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 Sep;75(9):4334–4338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y. M., Schimmel P. A simple structural feature is a major determinant of the identity of a transfer RNA. Nature. 1988 May 12;333(6169):140–145. doi: 10.1038/333140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerfeld I., Yarus M. An RNA pocket for an aliphatic hydrophobe. Nat Struct Biol. 1994 May;1(5):287–292. doi: 10.1038/nsb0594-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. L. Which organic compounds could have occurred on the prebiotic earth? Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:17–27. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr G., Caprara M. G., Guo Q., Lambowitz A. M. A tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase can function similarly to an RNA structure in the Tetrahymena ribozyme. Nature. 1994 Jul 14;370(6485):147–150. doi: 10.1038/370147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moras D. Structural and functional relationships between aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992 Apr;17(4):159–164. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller W., Janssen G. M. Statistical evidence for remnants of the primordial code in the acceptor stem of prokaryotic transfer RNA. J Mol Evol. 1992 Jun;34(6):471–477. doi: 10.1007/BF00160461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller W., Janssen G. M. Transfer RNAs for primordial amino acids contain remnants of a primitive code at position 3 to 5. Biochimie. 1990 May;72(5):361–368. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90033-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas H. B., Jr, McClain W. H. Searching tRNA sequences for relatedness to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase families. J Mol Evol. 1995 May;40(5):482–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00166616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normanly J., Abelson J. tRNA identity. Annu Rev Biochem. 1989;58:1029–1049. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.005121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okimoto R., Wolstenholme D. R. A set of tRNAs that lack either the T psi C arm or the dihydrouridine arm: towards a minimal tRNA adaptor. EMBO J. 1990 Oct;9(10):3405–3411. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa S., Jukes T. H. Codon reassignment (codon capture) in evolution. J Mol Evol. 1989 Apr;28(4):271–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin S. N., Ohno S. Two types of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases could be originally encoded by complementary strands of the same nucleic acid. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 1995 Dec;25(6):565–589. doi: 10.1007/BF01582025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin S., Ohno S., Rodin A. On concerted origin of transfer RNAs with complementary anticodons. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 1993 Dec;23(5-6):393–418. doi: 10.1007/BF01582088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin S., Ohno S., Rodin A. Transfer RNAs with complementary anticodons: could they reflect early evolution of discriminative genetic code adaptors? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 May 15;90(10):4723–4727. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff M., Krishnaswamy S., Boeglin M., Poterszman A., Mitschler A., Podjarny A., Rees B., Thierry J. C., Moras D. Class II aminoacyl transfer RNA synthetases: crystal structure of yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with tRNA(Asp). Science. 1991 Jun 21;252(5013):1682–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2047877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks M. E., Sampson J. R. Evolution of tRNA recognition systems and tRNA gene sequences. J Mol Evol. 1995 May;40(5):509–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00166619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel P., Giegé R., Moras D., Yokoyama S. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relationship to genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Oct 1;90(19):8763–8768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu M. Molecular basis for the genetic code. J Mol Evol. 1982;18(5):297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF01733895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S., Misch A., Sprinzl M. Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993 Jul 1;21(13):3011–3015. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel S. A., Cech T. R. Minor groove recognition of the conserved G.U pair at the Tetrahymena ribozyme reaction site. Science. 1995 Feb 3;267(5198):675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.7839142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szathmáry E. Coding coenzyme handles: a hypothesis for the origin of the genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Nov 1;90(21):9916–9920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.9916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szathmáry E., Zintzaras E. A statistical test of hypotheses on the organization and origin of the genetic code. J Mol Evol. 1992 Sep;35(3):185–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00178593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner A. M., Maizels N. tRNA-like structures tag the 3' ends of genomic RNA molecules for replication: implications for the origin of protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Nov;84(21):7383–7387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J. T. A co-evolution theory of the genetic code. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975 May;72(5):1909–1912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarus M. A specific amino acid binding site composed of RNA. Science. 1988 Jun 24;240(4860):1751–1758. doi: 10.1126/science.3381099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Duve C. Transfer RNAs: the second genetic code. Nature. 1988 May 12;333(6169):117–118. doi: 10.1038/333117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]