Abstract

The genus Berberis (Berberidaceae) includes about 500 species worldwide, some of which are widely cultivated in the north-eastern regions of Iran. This genus consists of spiny deciduous evergreen shrubs, characterized by yellow wood and flowers. The cultivation of seedless barberry in South Khorasan goes back to two hundred years ago. Medicinal properties for all parts of these plants have been reported, including: Antimicrobial, antiemetic, antipyretic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-arrhythmic, sedative, anti-cholinergic, cholagogic, anti-leishmaniasis, and anti-malaria. The main compounds found in various species of Berberis, are berberine and berbamine. Phytochemical analysis of various species of this genus revealed the presence of alkaloids, tannins, phenolic compounds, sterols and triterpenes. Although there are some review articles on Berberis vulgaris (as the most applied species), there is no review on the phytochemical and pharmacological activities of other well-known species of the genus Berberis. For this reason, the present review mainly focused on the diverse secondary metabolites of various species of this genus and the considerable pharmacological and biological activities together with a concise story of the botany and cultivation.

Keywords: Berberis, pharmacological effects, phytochemistry, zereshk

INTRODUCTION

The genus Berberis (Berberidaceae) includes about 500 species that commonly occur in most areas of central and southern Europe, the northeastern region of the United States and in South Asia including the northern area of Pakistan.[1,2] There are five species of this plant in Iran, two of them (B. orthobotrys and B. khorassanica) exclusively growing in the northern, eastern, and south eastern highlands of Iran (Alborz, Qaradagh in Azerbaijan, Mountains of Khorasan, Barez Mountain in Kerman).[3,4]

Berberis species, called “zereshk” in Persian language, are widely cultivated in Iran. The South-Khorasan province (especially around Birjand and Qaen) is the major field of cultivation for zereshk in the world.[5] Medicinal properties for all parts of these plants have been reported [Table 1], including tonic, antimicrobial, antiemetic, anti-pyretic, anti-pruritic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypotensive, anti-arrhythmic, sedative, anti-nociceptive, anti-cholinergic, cholagogic, and have been employed in cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, jaundice, dysentery, leishmaniasis, malaria, gall stones, hypertension, ischemic heart diseases (IHDS), cardiac arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies.[2,3,4,5,6] Also, barberry has been used to treat diarrhea, reduce fever, improve appetite, and relieve upset stomach.[7]

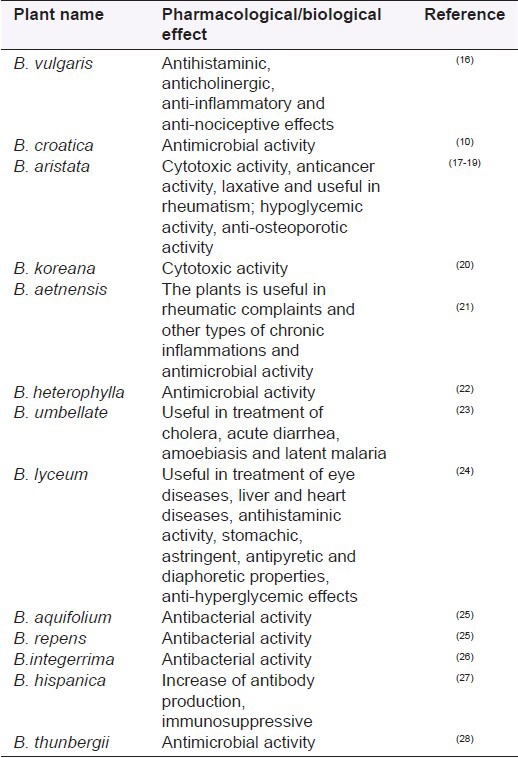

Table 1.

Pharmacological and biological activity of the various species of Berberis genus

Among the several species of this genus, Berberis vulgaris is well known and its fruits have been used in the preparation of a special dish with rice and also in Berberis juice.[8,9,10] Sometimes it has been used as a tea made from the bark of the plant.[7] Besides nutritional consumption, various parts of this plant including roots, bark, leaves and fruits have been employed in folk and traditional medicine for a long time in Iran.[7] The stem and root barks are used for their cathartic, diuretic, febrifuge, anti-bilious, and antiseptic properties. Also, the decoction of leaves is used as anti-scorbutic in dysentery, scurvy angina, and sore throat.[11] This article reviews mainly the phytochemical compounds of various species of Berberis together with the highlighted pharmacological and biological properties.

Plant characteristics

The Berberis genus consists of spiny deciduous evergreen shrubs, characterized by yellow wood and flowers,[9] dimorphic and long shoots together with the short ones (1-2 mm). The leaves on long shoots are not involved in photosynthesis but develop into three-spine thorns and finally short shoots with several leaves (1-10 cm long, simple, and either entire, or with spiny margins) involved in photosynthesis. Many deciduous species such as B. thunbergii and B. vulgaris indicate pink or red autumn color, while the leaves are brilliant white beneath in some Chinese evergreen species (B. candidula and B. verruculosa), and dark red to violet foliage is found in horticultural variants of B. thunbergii. On a single flower-head, the flowers are appears alone or in racemes. They are yellow or orange, 3-6 mm long, with both six sepals and petals (usually with similar color) in alternating whorls. The Berberis’ fruits are small berries (5-15 mm) which turn red or blue after ripening.[12,13]

In the lifecycle of Berberis, there are sexual and asexual reproduction processes which enable the plant to survive in harsh conditions. The distinctive yellow flowers of these plants appear in clusters and hang downwards from the stem. The reproductive organs of the flower are protected from rain by three inner concave sepals as well as six petals that completely enclose the stamens and anthers.[14]

The land under cultivation

Cultivation of zereshk in Iran is limited to the South-Khorasan province, especially around Birjand and Qaen. About 72% of the production is in Qaen and about 32% in Birjand. According to evidence the cultivation of seedless barberry in South-Khorasan goes back to two hundred years ago. The export of Berberis fruits is not considerable, because appropriate packaging is not available which affects the appearance and color of barberries. Besides this problem, barberry is not so familiar to people outside Iran.[15]

Pharmacological and biological effects

So far, many pharmacological and biological effects of various species of Berberis have been reported, some of which are summarized below in Table 1.

Phytochemistry

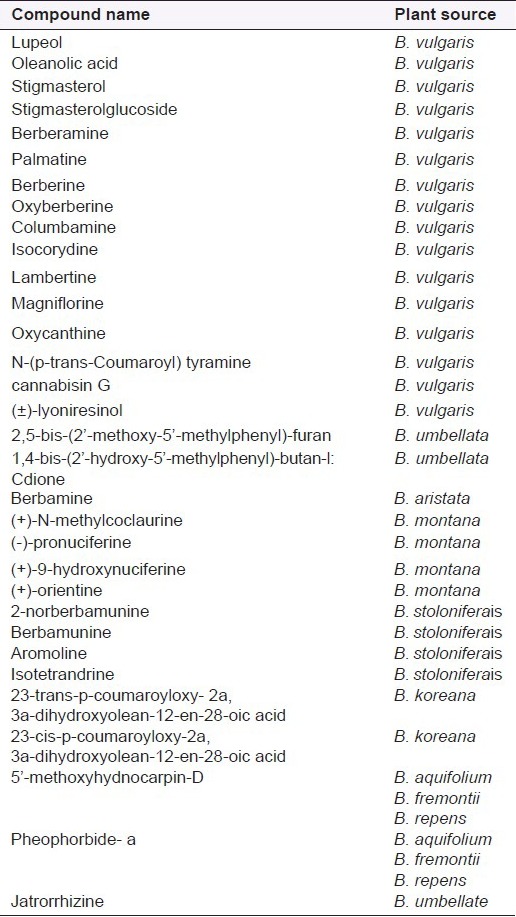

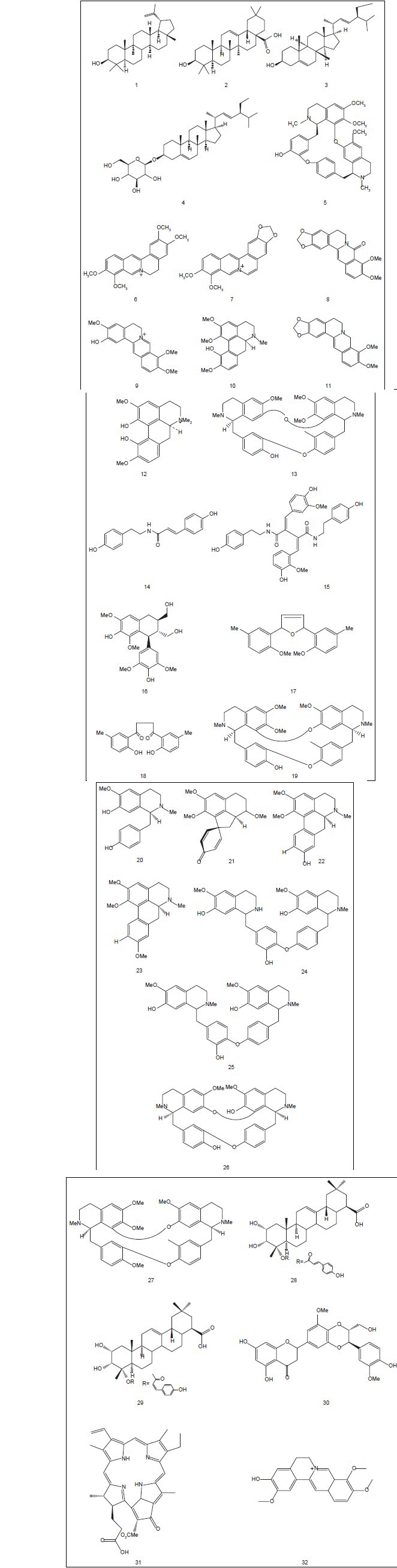

The main compounds, found in various species of Berberis, [Table 2] are berberine and berbamine [Figure 1]. Phytochemical analysis of the crude extract of B. vulgaris revealed the presence of alkaloids, tannins and phenolic compounds.[2] The triterpenes: lupeol (1), separated from its fruits, and oleanolic acid (2), isolated from ethanolic extract; the sterol: stigmasterol (3), obtained from hexane extract, and stigmasterol glucoside (4), from ethyl acetate extract; the alkaloids: berberamine (5), palmatine and (6) berberine (7), were reported for the first time from B. vulgaris.[11] Other important alkaloids: oxyberberine (8), columbamine (9), isocorydine (10), lambertine (11), magniflorine (12) and bisbenzlisoquinolines e.g., oxycanthine (13)[7] have been reported from this plant. Cytoprotective compounds including N-(p-trans-coumaroyl) tyramine (14), cannabisin G (15), and (±)-lyoniresinol (16)[29] have been isolated from ethyl acetate extract of B. vulgaris [Figure 1]. The compounds: 2,5-bis-(2’-methoxy-5’-methylphenyl)-furan (17) and 1,4-bis-(2’-hydroxy-5’-methylphenyl)-butan-l: cdione (18) were isolated and identified from the ethanolic extract of B. umbellate roots [Figure 1].[30,31,32,33,34] Chromatographic separation of the crude alkaloid fraction of B. chitria afforded a new aporphine (isoquinoline) alkaloid as an amorphous solid named: O-methylcorydine-N-oxide.[31] B. aristata contains also a valuable isoquinoline alkaloid berbamine (19).[17]

Table 2.

The main isolated compounds reported from different species of berberis. Structures of the compounds below are shown in Figure 1

Figure 1.

The structures of some phytochemical compounds isolated from various species of Berberis

B. montana contained four monomeric isoquinoline alkaloids: The benzyl isoquinoline (+)-N-methylcoclaurine (20), the proaporphine (-)-pronuciferine (21), and the aporphines (+)-9-hydroxynuciferine (22) and (+)-orientine (23), all of which were separated from methanol extract of this plant [Figure 1].[32] B. stolonifera is another species of Berberis which was investigated for biosynthetic pathway, and resulted in isolation of five bis-benzyl isoquinoline alkaloids from dried callus and suspension cultures as: 2-norberbamunine (24), berbamunine (25), and aromoline (26), berbamine (19) and isotetrandrine (27) [Figure 1].[33]

Several triterpenoids such as 23-trans-p-coumaroyloxy- 2a, 3a-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (28) and 23-cis-p-coumaroyloxy-2a, 3a-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (29) were isolated and structurally elucidated from B. korean [Figure 1].[20]

The active inhibitors 5’-methoxyhydnocarpin-D (30) and pheophorbide- a (31) have been isolated from the leaves of B. aquifolium, B. fremontii and B. repens respectively.[25] Furthermore, Jatrorrhizine (32) as aporotoberberine alkaloid has been separated from B. umbellate.[23] Tetrahydro isoquinoline alkaloids are another noteworthy alkaloid group reported from B. tinctoria.

CONCLUSION

Crocus sativus, Cuminum cyminum and Berberis vulgaris are important medicinal food plants growing widely in Iran and also cultivated for their nutritional purposes and economic significance.[35,36] “Zereshk” is a Persian common name for the genus Berberis that has been frequently consumed as a food additive and also traditionally as a remedy in Iran. In traditional and folklore medicine, it has been used for its many pharmacological and biological activities, which make it an effective remedy for various kinds of illnesses. The literature reviews revealed the presence of quinoline and isoquinoline alkaloids together with sterols and triterpenes. Bereberine and other similar alkaloids have been identified as the main responsible natural compounds for diverse medicinal properties.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors would like to say many thanks to Mrs. M. Kurepaz-Mahmoodabadi for her kind assistance in the preparation of this paper.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kafi M, balandary A. Mashhad: Language and Literature; 2002. Berberis production and processing. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rounsaville TJ, Ranney TG. Ploidy levels and genome sizes of Berberis L. and Mahonia nutt. species, hybrids, and cultivars. Hortscience. 2010;45:1029–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozaffarian V. Tehran: Farhang-e-Moaser; 2008. A dictionary of Iranian plant names. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berberies [homepage on the internet] [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 13]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berberis .

- 5.Kafi M, Balandri A. Iranian Research Organization for Science and Technology, Center of Khorasan; 1995. Effects of gibberellic acid and ethephon on fruit characteristics and ease of harvest seed less barberry. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolar D, Wimmerova L, Kadek R. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of Berberis vulgaris. Phytopharmacol. 2010;1:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomosaka H, Chin YW, Salim AA, Keller WJ, Chai H, Kinghorn AD. Antioxidant and cytoprotective compounds from Berberis vulgaris (Barberry) Phytother Res. 2008;22:979–81. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fatehi M, Saleh TM, Fatehi-Hassanabad Z, Farrokhfal K, Jafarzadeh M, Davodi S. A pharmacological study on Berberis vulgaris fruit extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamsa F, Ahmadiani A, Khosrokhavar R. Antihistaminic and anticholinergic activity of barberry fruit (Berberis vulgaris) in the guinea-pig ileum. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;64:161–6. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosalec I, Gregurek B, Kremer D, Zovko M, Sankovic K, Karlovic K. Croatian barberry (Berberis croatica Horvat): A new source of berberine-analysis and antimicrobial activity. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:145–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saied S, Begum S. Phytochemical studies of Berberis vulgaris. Chem Nat Compd. 2004;40:137–40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perveen A, Qaiser M. Pollen flora of Pakistan-LXV. Berberidaceae. Pak J Bot. 2010;42:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan M. Department of Plant Sciences Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad; 2010. Biological activity and phytochemical study of selected medicinal plants. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson PD, Leonard KJ, Miller JD, Laudon RJ, Sutton TB. Prevalence and distribution of common barberry, the alternate host of Puccinia graminis, in Minnesota. Plant Dis. 2005;89:159–63. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golmohammadi F, Motamed MK. A viewpoint toward farm management and importance of barberry in sustainable rural livelihood in desert regions in east of Iran. Afr J Plant Sci. 2012;6:213–21. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akbulut M, Çalisir S, Marakog˘lu T, Çoklar H. Some physicomechanical and nutritional properties of Berberry (Berberis Vulgaris L.) fruits. J Food Process Eng. 2009;32:497–511. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papiya MM, Saumya D, Sanjita D, Manas KD. Cytotoxic activity of methanolic extracts of Berberi saristata DC and Hemidesmus indicus R.Br. in MCF7 cell line. J Curr Pharm Res. 2010;1:12–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Upwar N, Patel R, Waseem N, Mahobia NK. Hypologycemic effect of methanolic extract of Berberis aristata DC stem on normal and streptozotocin induced diabetic rars. Int J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci. 2011;3:222–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yogesh HS, Chandrashekhar VM, Katti HR, Ganapaty S, Raghavendra HL, Gowda GK, et al. Anti-osteoporotic activity of aqueous-methanol extract of Berberis aristata in ovariectomized rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:334–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KH, Choi SU, Lee KR. Bioactivity-guided isolation of cytotoxic triterpenoids from the trunk of Berberis koreana. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:1944–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Musumeci R, Speciale A, Costanzo R, Annino A, Ragusa S, Rapisarda A, et al. Berberis aetnensis C. Presl. extracts: Antimicrobial properties and interaction with ciprofloxacin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;22:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iauk L, Costanzo R, Caccamo F, Rapisarda A, Musumeci R, Milazzo I, et al. Activity of Berberis aetnensis root extracts on candida strains. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:159–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sing R, Tiwari SS, Srivastava S, Ravat AK. Botanical and phytochemical studies on roots of Berberis umbellate Wall. ex G Don. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2012;3:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulfraz M, Arshad M, Nayyer N, Kanwal N, Nisar U. Investigation for bioactive compouns of Berberis lyceum royle and Justicia adhatoda L. Ethnobot Leaflets. 2004;1:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stermitz FR, Beeson TD, Mueller PJ, Hsiang J, Lewis K. Staphylococcus aureus MDR efflux pump inhibitors from a Berberis and a Mahonia (sensustrictu) species. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2001;29:793–8. doi: 10.1016/s0305-1978(01)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alimirzaee P, Gohari AR, Mirzaee S, Monsef- Esfahani HR, Amin Gh, Saeidnia S, et al. 1-methyl malate from Berberis integerrima fruits enhances the antibacterial activity of ampicillin against Staphylococcus aureus. Phytother Res. 2009;23:797–800. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Youbi AE, Ouahidi I, Aarab L. In vitro immunomodulation effects of the aqueous and protein extracts of Berberis hispanica Boiss and Reut. (Family Berberidaceae) J Med Plants Res. 2012;6:4239–46. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li A, Zhu Y, Li X, Tian X. Antimicrobial activity of four species of Berberidaceae. Fitoterapia. 2007;78:379–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomosaka H, Chin Y, Salim AA, Keller WJ, Chai H, Kinghorn AD. Antioxidant and cytoprotective compounds from Berberis vulgaris (Barberry) Phytother Res. 2008;22:979–81. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masood M, Tiwar KP. 2,5-Bis-(2’- Methoxy-5’- Methyl phenyl)-Furan, a rare type Of compound from Berberis umbellata. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:295–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussaini FA, Shoeb A. Isoquinoline derived alkaloids from Berberis chitria. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:633. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabezas NJ, Urzua AM, Niemeyer HM. Translocation of isoquinoline alkaloids to the hemiparasite, from its host, Berberis montana. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2009;37:225–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stadler R, Loeffler S, Cassels BK, Zenk MH. Bisbenzyl isoquinoline bioynthesis in Berberis stolonifera cell cultures. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:2557–65. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majumder P, Sucharitas S. 1,4-Bis-(2’- Hydroxy-5’- Methyl phenyl)-Butan-1,4-Dione- a biogenetically rare type of phenolic of Berberis coriaria. Phytochemistry. 1978;17:1439–40. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gohari AR, Saeidnia S. A review on phytochemistry of Cuminum cyminum seeds and its standards from field to market. Pharmacogn J. 2011;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gohari AR, Saeidnia S, Kourepaz Mahmoodabadi M. An overview on saffron, phytochemicals, and medicinal properties. Pharmacogn Rev. 2013;7:61–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.112850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]