Abstract

Context:

Palliative care in Thailand was not well developed in the past. Previous studies showed that the actual prescription of opioids was underutilized in palliative care by physicians compared with the estimated opioid need of patients. However, there were no studies regarding the regulation of opioids in Thailand.

Aims:

To provide an up-to-date overview of the role of multidisciplinary teams in the regulation of opioids in Thai government hospitals.

Settings and Design:

A questionnaire survey study was conducted from January to April 2012.

Materials and Methods:

The questionnaire was distributed to entire population of government hospitals in Thailand and all private hospitals in Bangkok. There were 975 hospitals, including 93 private hospitals in Bangkok and 882 government hospitals.

Statistical analysis used:

Results are presented as a frequency and percentage.

Results:

Special opioid prescription forms must be signed by doctors for all opioid prescriptions. Three-fourths of hospitals totally prohibited prescribing oral opioids by palliative care Advance Practice Nurses. Pharmacists were permitted to correct the technical errors on a prescription of oral morphine only after notifying the prescribing doctor in nearly 60% of hospitals. In terminal patients who could not go to the hospitals, caregivers were permitted to collect the opioids on behalf of patients in nearly 80% of hospitals.

Conclusion:

Our results illustrate that the regulation of opioids in government hospitals is mainly dependent on physician judgment. Patients can only receive oral morphine at a hospital pharmacy.

Keywords: Pain management, Palliative care, Regulation of opioids, Thailand

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care in Thailand was not well developed in the past. The development of palliative care in Thailand was classified as a localized hospice-palliative care provision without integration into the mainstream healthcare system.[1,2]

Opioids are essential medications for symptom management in palliative care. Previous studies showed that the actual prescription of opioids was underutilized in palliative care by physicians compared with the estimated opioid need of patients.[3,4,5,6] In detail, annual morphine consumption in Thailand gradually increased from 3 to 4 kg (33%) between 1984 and 1990.[3] In 1990, the estimated annual requirement was 15 kg of morphine, whereas the real medical morphine consumption was only 5 kg.[4] Pain and Policy Studies Group (PPSG) reported that morphine consumption in Thailand increased nearly 10 times in three decades. “However, Thailand morphine consumption per capita (0.7739 mg/capita) was still less than mean global morphine consumption (5.9847 mg/capita) and mean Asia morphine consumption (1.2517 mg/capita). Thailand's morphine consumption was ranged in 71 from 154 countries worldwide”.[5] Recently, an International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) report classified Thailand as an inadequate morphine consumption group.[6] Strict drug legislation and fear of drug diversion were claimed as contributing factors to this phenomenon.[4,7,8]

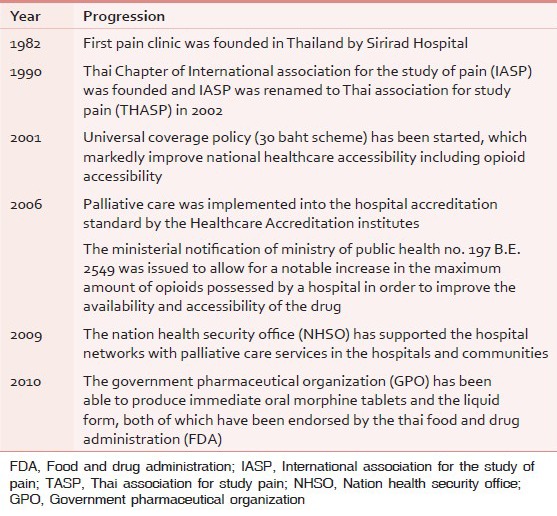

Palliative care in Thailand is now better supported by many organizations. In 2006, palliative care was implemented into the hospital accreditation standard by the Healthcare Accreditation institutes.[9,10] Meanwhile, the Ministerial Notification of Ministry of Public Health No. 197 B.E. 2549 was issued to allow for a notable increase in the maximum amount of opioids possessed by a hospital in order to improve the availability and accessibility of the drug.[11] In addition, the Thai Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Nation Health Security Office (NHSO), and the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO) have made great contributions to palliative care development in terms of opioid availability and price lowering. The NHSO has supported the hospital networks with palliative care services in the hospitals and communities since 2009, whereas the GPO has been able to produce immediate oral morphine tablets and the liquid form, both of which have been endorsed by the Thai FDA since 2010. Timeline of palliative care progression in Thailand is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of palliative care progression in Thailand

Despite a change in situation, pain has remained under-treated in the majority of cancer patients, even in the tertiary care services.[11,12] It is questionable if the regulation of opioids is still a barrier to pain management. There were no studies regarding the regulation of opioids in Thailand. This study aims to provide a current overview of the regulation of opioids, the role of multidisciplinary teams (MDT) and the dynamics between members of the MDT in the regulation of opioids in Thai government hospitals.

Study design

The questionnaire was developed by the research collaborative group of the Asia Pacific Hospice Network (APHN) and was translated into the Thai language; it included five sections: The hospital characteristics, palliative care services and personnel, availability of essential drugs, the regulation of opioids, and the need of a supporting system.

The data were collected from January to April 2012. The questionnaires were sent to the director of each hospital in the study population by post. The palliative care leaders in the hospitals were asked to respond to the survey voluntarily and send the data back either by post, fax, or online. The respondents’ names, telephone numbers, and email addresses were also requested, so the investigators could contact them directly for clarification or more information. There was no further contact for nonresponsive hospitals. The hospital's current status on January 1, 2012 has been used in this study.

In the regulation of opioids section, five questions were formulated from the routine steps of opioid accessibility in the Thai hospitals. They are described below. Each question has four choices available. The respondents can fill in addition comments if they wish. However, the in depth interview regarding to the regulation of opioids were not conducted.

Were doctors required to sign a special form every time they prescribed oral morphine?

Is the amount of oral morphine limited per one prescription?

Can caregivers receive oral morphine prescriptions on behalf of patients in cases where the patients are unable to go to hospital by themselves?

Is the prescription of oral morphine by Advance Practice Nurses (APN) permitted?

Are pharmacists permitted to correct technical errors (e.g., no address, misspelling, missing value, etc.) on a prescription of oral morphine?.

The questionnaire was distributed to entire population of government hospitals in Thailand and all private hospitals in Bangkok. There were 975 hospitals, including 93 private hospitals in Bangkok and 882 government hospitals. The government hospitals consisted of medical school hospitals, cancer centers, and hospitals under the Ministry of Health (community hospitals, general hospitals, and regional hospitals). Hospitals not under the Ministry of Health are classified as other hospitals.

Statistical analysis

SPSS for Windows was used for statistical analysis. Results are presented as a frequency and percentage. The addition comments were managed by Excel for Windows program. Thai language comments were translated to English by the first author.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at Prince of Songkla University.

RESULTS

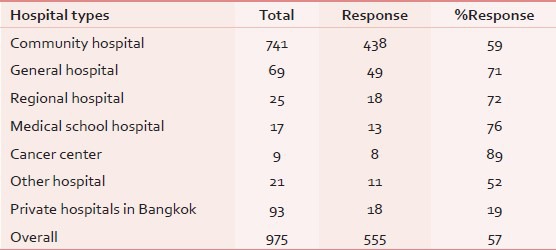

Five hundred thirty-seven government hospitals replied to the questionnaire for a response rate of 61%. Private hospitals were excluded from the analysis because of their low response rate of 19%. The questionnaire's response rates of the sample hospitals are demonstrated in Table 2. There are six types of hospitals, including 438 (81.6%) community hospitals (CH), 49 (9.1%) general hospitals (GH), 18 (3.4%) regional hospitals (RH), 8 (1.5%) cancer centers (CC), 13 (2.4%) medical school hospitals (MH), and 11 (2.0%) other hospitals (OH).

Table 2.

Questionnaire's response rates of the sample hospitals

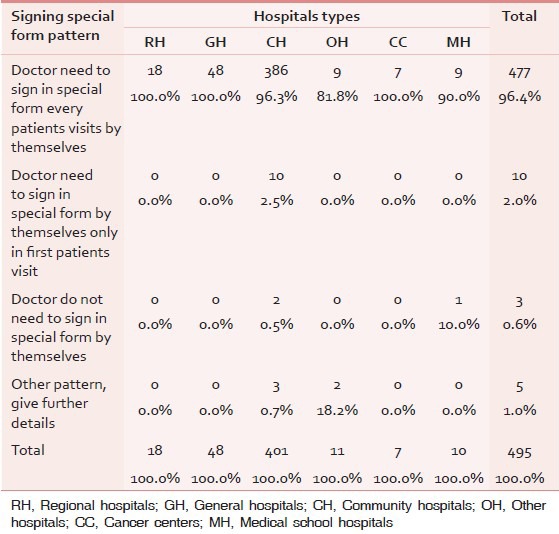

Were doctors required to sign a special form every time they prescribed oral morphine?

Nearly all of the hospitals need the doctors to sign a special form for every single patient visit (96.4%). However, some community hospitals used other patterns. Ten community hospitals permit doctors to sign only on the first visit, thereafter the nurses can prescribe under doctor supervision. Only two community hospitals and one medical school hospital do not require the doctor to sign a special form.

Additional comments from respondents mentioned that community hospitals did not have enough doctors, especially to work overtime; therefore the nurses were assigned to the first call. In cases where injectable morphine was prescribed, the used morphine ampoules were collected concomitant with the signed special form [Table 3].

Table 3.

Patterns of signing a special form in different types of hospitals

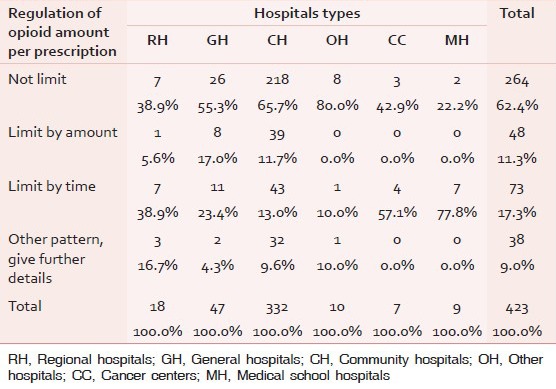

Is the amount of oral morphine limited per one prescription?

The regulation of opioid amount per prescription pattern is described in Table 4.

Table 4.

The patterns of prescribing opioids in different types of hospitals

The majority of hospitals have no specific regulation of opioid amount per prescription (62.4%).

The first pattern of prescribing opioid was the amount limit by follow up timeframe (17.3%). Fifty-seven hospitals limited amount of prescribing oral opioids for one month's supply of medication. The remainder limited amount of prescribing oral opioids for 2-3 months’ supply of medication.

Second pattern was the amount limit (11.3%). In cases of controlled release oral morphine, 21 hospitals restrict prescriptions to not more than 30 tablets. Ten hospitals limit prescriptions to not more than 20 tablets. For immediate release oral morphine, 11 hospitals limit the amount to 2-3 bottles of 60 ml per prescription (ranging from 1 to 10 bottle).

The other patterns of prescribing opioids were mentioned in various ways (9%). Twenty-four hospitals depend on doctors’ judgment. The rest of the patterns limit both amount and duration; limits are set on the amount prescribed by health insurance types and the amount of oral opioids in the pharmacy's stock. Only one hospital did not allow prescribing oral morphine for outpatients.

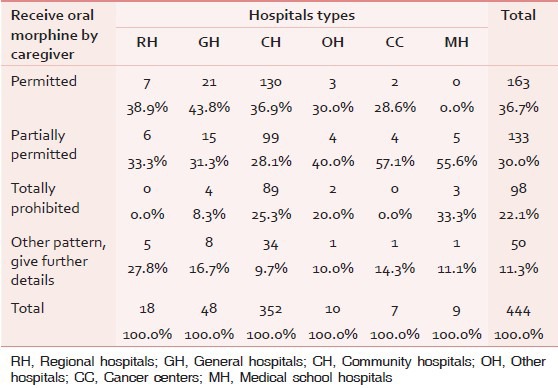

Can caregivers receive oral morphine prescriptions on behalf of patients in cases where the patients are unable to go to hospital by themselves?

From Table 5, many hospitals permit caregivers to receive oral opioids on behalf of patients (36.7%). In contrast, some hospitals totally prohibit the caregivers to receive oral opioids on behalf of patients (22.1%). No comments were added by the respondents.

Table 5.

The permission to receive opioids for caregivers on behalf of patients

Partially permitted pattern (30.0%) and other patterns (11.3%) are described in similar ways. The rationales of the permission to receive opioids for caregivers on behalf of patients in this issue were grouped into four criteria.

Patients’ aspect

Every hospital in this group mentioned two criteria

The evidence that the patients are at a palliative stage, for example, referral letters, medical records stating a diagnosis of terminal stage cancer

The reasons that make it difficult for patients to collect morphine by themselves were evaluated by physicians, nurses and pharmacists, for example, patient's physical status, rural patients.

Caregivers’ aspect

Twenty-two hospitals mentioned that caregivers should be previously recognized as formal caregivers by medical personnel, that is, doctors, nurses, or pharmacists. The evidence from patients, such as a patient's identification card, must be shown and caregivers need to sign an official form before obtaining the oral morphine.

System aspect

Thirty hospitals identified home visits by home care teams, primary care teams, and local networks as a key process of accountability.

Some hospitals identified a clear clinical pathway on this issue as mentioned below.

“First step is caregiver identification. The nurse check patients’ histories if they were palliative patients. Next step is to notify physicians to make decision if they prescribe opioids to caregiver on behalf of patients. Then, the pharmacists dispense oral opioids. Last, contact local health office to reevaluate and have a home visit”

Doctor aspect

Forty-seven hospitals mentioned that doctors justified which caregiver can obtain the opioids on behalf of palliative patients.

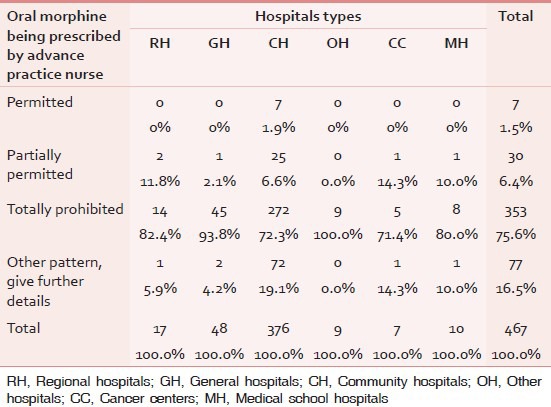

Is the prescription of oral morphine by Advance Practice Nurses permitted?

The permission to prescribe oral morphine by advance practice nurses were demonstarted in Table 6. The majority of hospitals totally prohibited prescribing oral opioids by APN (75.6%). Only seven community hospitals permitted nurses to prescribe oral morphine (1.5%). Five hospitals trained palliative care nurses, whereas two hospitals had no APN.

Table 6.

The permission to prescribe oral morphine by advance practice nurses

Partial permission was accountable for 6.4%. Twenty-five in thirty hospitals needed to notify doctors by telephone before prescribing morphine. The situations where nurses were allowed to prescribe oral morphine included emergency conditions, patients running out of their opioid stock before appointment time, and special clinics in which clinical practice guidelines are well established. A special form was required to be signed by a doctor within 24 hours. Another pattern (16.5%) was allowing nurses to prescribe the known cases of palliative care where the patient had already taken oral opioids.

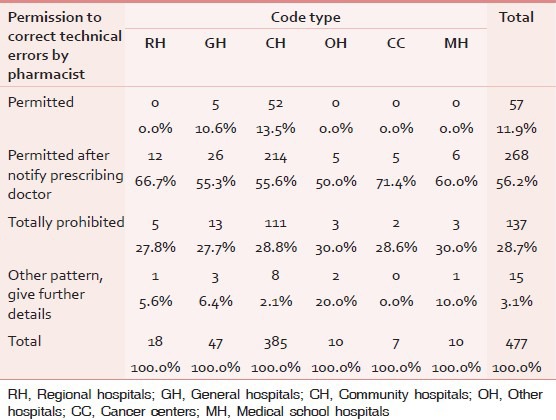

Are pharmacists permitted to correct technical errors (e.g., no address, misspelling, missing value, etc.) on a prescription of oral morphine?

The Table 7 showed the permission for pharmacists to correct technical errors on a prescription of oral morphine. Nearly 60% of hospitals permitted pharmacists to correct technical errors after notifying the prescribing doctor. More than one-fourth of hospitals totally prohibited pharmacists from correcting doctors’ prescriptions. Some hospitals (11.9%), mainly community hospitals, allowed pharmacists to correct technical errors without notifying the prescribing doctor. The remainder (3%) commented that there was no clear clinical practice guideline, counseling system, or pharmaceutical policy on opioids.

Table 7.

The permission for pharmacists to correct technical errors on a prescription of oral morphine

DISCUSSION

This first national survey provided current status of palliative care in Thailand. This study is one part of the survey that focused on opioid regulation and role of MDT on opioid regulation.

Opioid regulation

Four potential ways in which controlled substances regulations and policies can affect medical care are, including, (i) by placing restrictions on physician practice, (ii) by affecting patient access to opioids, (iii) by stigmatizing patients, and (iv) indirectly through physicians’ perceptions of regulations, resulting in modified medical practices.[13] From the result of this study, government hospitals in Thailand permit every physician to be able to prescribe oral morphine for patients with their own judgment without registration. In comparison, this finding showed more relaxed policy on regulation of opioids, which is benefit for opioids accessibility for eligible patients than some other countries. The East-European countries and a few West-European countries require outpatients receive a permit or be registered to be eligible to receive opioid prescriptions for the management of cancer pain.[14] Some European countries require physicians to receive a special authority/license to prescribe opioids.[14]

Developing countries tend to strictly limit the amount in the short interval and limited maximum dose of opioids prescription.[8] In Thailand, more than 60% of hospitals permitted the physicians to prescribed opioids amount by their own clinical judgments. The patterns of opioid prescriptions varied widely in Thailand. This finding implies an unclear rationale of opioid prescribing and dispensing in Thailand. Apart from unclear rationale, recent study regarding opioid availability in Thailand mentioned that overall oral morphine availability was less available than 51.0%.[15] This factor may also affect on the amount of prescribing and dispensing opioid.

For patients who could not go to the hospital, caregivers were permitted to obtain opioids on behalf of patients in nearly 80% of hospitals. There were no specific rules for opioids prescription in this condition. These hospitals set their own rationale to prescribe oral opioids in this group, that is, the palliative care patients who were approaching the terminal stage of their illnesses, or living in areas remote from hospitals. In these cases, caregivers should be previously recognized by medical personnel as formal caregivers. Evidence from patients, such as patients’ identification cards, must be shown and caregivers need to sign a form before obtaining the oral morphine. Some hospitals notified home care teams, primary care teams, and local networks to visit the patients’ homes in order to evaluate the patients and their family conditions.

Role of MDT in the regulation of opioids

The physicians are the key person who prescribed opioids. The physician shortage was demonstrated especially in community hospitals in this study.

The nurses were allowed to evaluate patients and prescribe morphine under doctors’ supervision, mainly by telephone. The nurses’ main roles were frontline screening and managing under physician supervision. The pharmacist played their roles as the last gatekeepers in prescribing opioids. Majority of hospitals permitted pharmacists to correct technical errors after notifying the prescribing doctor.

Knowledge of opioids usage among medical personnel is still problematic. Recent published article regarding the education status of palliative care and palliative care service availability showed that majority of medical personnel take palliative care less than one week of short duration of training.[16] This factor may cause underused of opioids by physicians. Reasons for this include excessive concern about opioid-induced respiratory depression, tolerance, and addiction, as well as the impact of controlled substances regulations. The negative impact of controlled substances regulations on patient care is not well understood.[13]

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study showed the steps of opioid accessibility in Thai hospitals. Physicians can prescribe oral morphine for patients with their own judgment without registration. For an opioids prescription, the doctor needs to sign the duplicate special form, which includes information about the physician, license numbers, patient details, type, and amount of medication. The majority of hospitals that totally prohibited prescribing oral opioids by APN was 75.6%.

Patients can only receive oral morphine at a hospital pharmacy. Nearly 60% of hospitals permitted pharmacists to correct technical errors after notifying the prescribing doctor. The amount of opioids per prescription was not regulated in more than 60% of hospitals. The rest limited the prescribing of opioids by amount (<30 tablets of continuous release oral morphine) or time (ranging from 1 to 3 months). For palliative care patients who could not go to the hospital due to poor physical status, caregivers were permitted to obtain opioids on behalf of patients in nearly 80% of hospitals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the Health Promotion Foundation and The Consortium of Thai Medical Schools that support Thai Medical Schools Palliative Care Network projects, including this survey. The authors would also like to thank all questionnaire respondents and Mr. Trevor Pearson for his English language advice.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wright M, Hamzah E, Phungrassami T, Bausa-Claudio A. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. Hospice and Palliative Care in Southeast Asia: A review of developments and challenges in Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; 2011. [Last accessed on 2012 Mar 11]. Mapping levels of palliative care development: A global update 2011. Available from: WWW.THEWPCA.ORG . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joranson DE. Availability of opioids for cancer Pain: Recent trends, assessment of system barriers, New World Health Organization guidelines and the risk of diversion. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:353–60. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90052-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaudakshetrin P. Thailand: Status of cancer pain and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8:434–6. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(93)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Pain and Policy Studies Group/WHO Collaborating Centre for Policy and Communications in Cancer Care; 2008. Pain and Policy Studies Group. Availability of Opioid Analgesics in the World and Asia, with a special focus on. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Genneva: United Nation; 2010. International Narcoitcs Control Board (INCB). Report of the International Narcotics Control Board on the Availability of Internationally Controlled Drugs: Ensuring Adequate Access for Medical and Scientific Purposes. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagaviroj K, Jaturapatporn D. Cancer pain–progress and ongoing issues in Thailand. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:361–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald D, Finley G. Governmental barriers to opioid availability in developing countries. J Pharmaceut Care Pain Symptom Control. 2001;9:5–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilmanat K, Phungrassami T, editors. Status of End of Life Care in Thailand. Proceeding of the 2006, Bridging the Gap: Transforming Knowledge into Action. Washington, USA: UICC World Cancer Congress; 2006. Jul 8-12, [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hospital and Healthcare Standard: 60th anniversary years Celebrations of His Majesty's Accession to the Throne; 2006. [Last accessed on 2012 Mar 11]. The Healthcare Accreditation institutes (Public Organization) Available from: www.ha.or.th/ha2010/upload/processBasic/htmlfiles/78-5583-0.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patcharapisarn N, Ketumarn P, Jirapramukpitak T. Pain control in cancer patients in tertiary care setting. Thammasat Med J. 2009;9:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vatanasapt P, Lertsinudom S, Sookprasert A, Phunmanee A, Pratheepawanit N, Wattanaudomrot S, et al. Prevalence and management of cancer pain in Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:1873–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weissman DE. Doctors, opioids, and the law: The effect of controlled substances regulations on cancer pain management. Semin Oncol. 1993;20:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherny NI, Baselga J, de Conno F, Radbruch L. Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Europe: A report from the ESMO/EAPC Opioid Policy Initiative. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:615–26. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thongkhamcharoen R, Phungrassami T, Atthakul N. Palliative care and essential drug availability: Thailand national survey 2012. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:546–50. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phungrassami T, Thongkhamcharoen R, Atthakul N. Palliative care personnel and services: A national survey in Thailand 2012. J Palliat Care. 2013;29:133–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]