Summary

B cell antigen receptor (BCR) ligation leads to receptor desensitization wherein BCR remain competent to bind antigen and yet fail to transduce signals. Desensitized BCR exhibit a defect at the most proximal level of signal transduction, consistent with failed transmission of signals through the receptor complex. We report that antigen stimulation leads to dissociation or destabilization of the BCR reflected by inability to coimmunoprecipitate Ig-α/Ig-β with mIg. This destabilization is temporally correlated with desensitization recepand occurs in BCR containing mIgM and mIgD. Induction of BCR destabilization requires tyrosine kinase activation but is not induced by phosphatase inhibitors. BCR destabilization occurs at the cell surface and “dissociated” Ig-α/Ig-β complexes remain responsive to anti-Ig-β stimulation, suggesting that mIg-transducer uncoupling may mediate receptor desensitization.

Introduction

The B cell antigen receptor complex is composed of membrane immunoglobulin noncovalently associated with heterodimers of Ig-α and Ig-β. These signal-transducing subunits contain a conserved ITAM (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation) motif required for signal transduction (Cambier, 1995). Aggregation of the BCR by multivalent antigen initiates transphosphorylation of the Ig-α and Ig-β ITAM motifs and activation of receptor-associated kinases (for review see DeFranco, 1997; Kim et al., 1993; Kurosaki, 1997). Phosphorylated ITAMs recruit additional effectors such as Fyn, Shc, and Syk, and propagate signals leading to activation of downstream effectors such as PI3-K, PLC-γ, and members of the Ras/MAPK pathway. These signaling events are responsible for B cell proliferation and increased expression of activation markers such as MHC class II and CD86 that are required to prime the B cell for subsequent interactions with Th cells.

The B cell repertoire is finely tuned to contain maximal receptor diversity in the absence of autoreactivity. Autoreactive clones are eliminated by processes including clonal deletion by apoptosis or receptor editing, and anergy (Goodnow et al., 1988; Nemazee and Burki, 1989; Hartley et al., 1993; Rathmell et al., 1996; Hertz and Nemazee, 1997). In the latter case, autospecific cells persist but are unresponsive to antigen. The molecular mechanisms underlying B cell unresponsiveness have been studied in BCR transgenic mice and in several in vitro models of receptor desensitization (Cambier et al., 1988, 1990; Nemazee and Burki, 1989; Erikson et al., 1991; Okamoto et al., 1992; Gay et al., 1993; Brunswick et al., 1994; Vilen et al., 1997). Studies in the HEL/anti-HEL double transgenic mouse have shown that B cells tolerant to self antigen exhibit reduced cell surface expression of IgM, are no longer capable of antigen-induced CD86 expression, and are sensitive to Fas-mediated apoptosis (Goodnow et al., 1989; Ho et al., 1994; Rathmell et al., 1996). In a number of these models, receptor desensitization is characterized by the inability of antigen to elicit tyrosine phosphorylation or renewed Ca2+ mobilization despite the continued expression of antigen binding receptors. Recently, disruption of receptor proximal signaling events has been studied in desensitized B cells (Cooke et al., 1994; Vilen et al., 1997). Results from these studies reveal a lack of antigen-induced phosphorylation and activation of receptor-associated kinases such as Lyn, Blk, and Syk. Interestingly however, receptor-associated kinases could be activated by exposure to doubly phosphorylated ITAM peptides, suggesting that the failure of desensitized receptors to activate signaling pathways was not due to a defect intrinsic to the kinase but rather reflected a defect at the level of the receptor (Johnson et al., 1995). In this manuscript, we define a molecular event that may be responsible for maintaining the unresponsive phenotype of desensitized cells.

We show that upon binding of moderate-to low-affinity antigen, the Ig-α/Ig-β subunits of the BCR become destabilized or physically dissociated from mIg. This event requires specific activation of the BCR signaling cascade. Most interestingly, although desensitized cells fail to respond to receptor ligation, the Ig-α/Ig-β complex retains signaling function if aggregated, suggesting that transducer dissociation from mIg may mediate the unresponsive state.

Results

The Ig-α and Ig-β Signal-Transducing Subunits of the BCR Are Destabilized from IgM following Antigen Stimulation

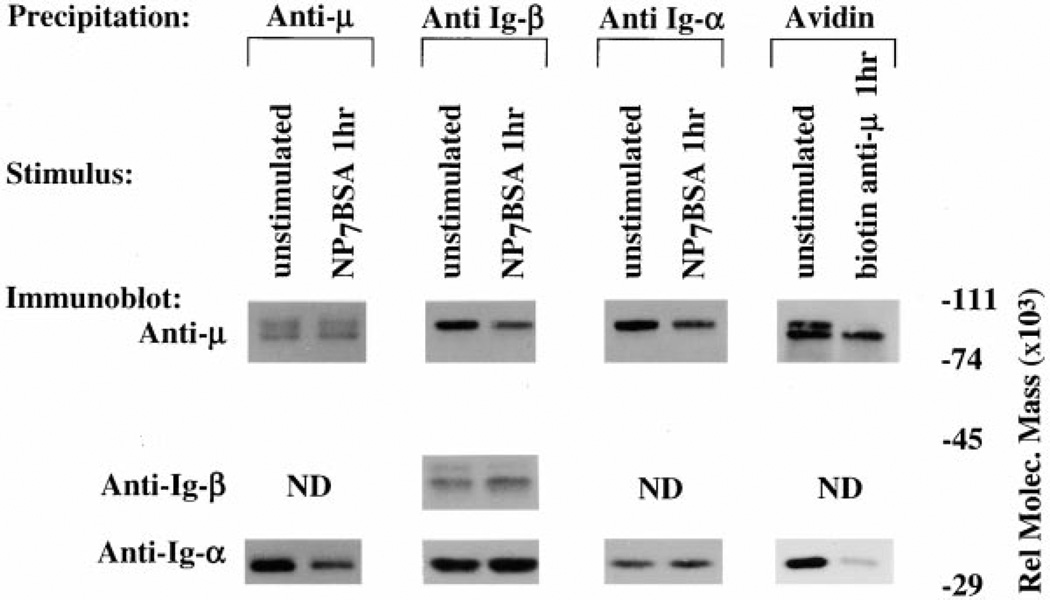

Previous studies of desensitized cells suggested that the defect in BCR signaling lies upstream of src-family kinase activation, possibly at the level of the receptor (Vilen et al., 1997). To address changes in BCR structure under conditions of receptor desensitization, we immunoprecipitated µ-heavy chain, Ig-α, or Ig-β from de-sensitized K46µ cell lysates and quantitated the coprecipitated BCR components. As shown in Figure 1, panel 1, IgM (µ-heavy chain) from cells stimulated for 1 hr with antigen (desensitized) coprecipitated with approximately 67% less (determined by densitometry) Ig-α compared to IgM from unstimulated cells. Similarly, Ig-β and Ig-α (Figure 1, panels 2 and 3) from cells stimulated for 1 hr coprecipitated with 50%–66%less IgM(µ-heavy inchain) than unstimulated cells. This loss of coprecipitable Ig-α was not simply due to movement of receptors to the cytoskeletal/detergent insoluble fractions as the levels of IgM (panel 1) or Ig-α/Ig-β (panels 2 and 3) remained constant. The failure of the transfected IgM receptor in the K46µ cells to rapidly downmodulate was not due to a defect in cytoskeletal association, as high-affinity antireceptor antibodies and prolonged incubation with antigen (>3 hr) caused receptor downmodulation (Figure 1, panel 4; data not shown). These results show that within 1 hr of BCR aggregation by moderate-affinity antigen (KD = 1.5 × 10−6 for NP binding B-1–8 and approximately 10−5 to 10−6 for H-2Kb binding 3–83), significantly less Ig-α/Ig-β dimer is associated with mIgM, suggesting a dissociation or destabilization of the BCR complex in antigen-desensitized cells (Lang et al., 1996; Dal Porto et al., 1998).

Figure 1. Comparative Analysis of mIg-Ig-α/Ig-β Association in K46µ Cells.

Cells were either unstimulated, stimulated for 1 hr with NP7BSA (500 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml), or stimulated for 1 hr with biotinylated b-7-6 (10 µg/5 × 106/ml). (Panel 1) Lanes 1 and 2 represent IgM and Ig-α immunoblots of anti-µ immunoprecipitates. (Panel 2) Lanes 3 and 4 represent IgM, Ig-β, and Ig-α immunoblots of anti-Ig-β immunoprecipitates. (Panel 3) Lanes 5 and 6 represent IgM and Ig-α immunoblots of Ig-α immunoprecipitates. (Panel 4) Lanes 7 and 8 represent IgM and Ig-α immunoblots of streptavidin immunoprecipitates. Biotinylated b-7–6 was prebound to unstimulated cells (10 µg/5 × 106 cells/ml) for 2 min at 4°C prior to lysis.

The Timing of BCR Destabilization Is Coincident with Receptor Desensitization

To establish the temporal relationship between BCR destabilization and receptor desensitization, we performed a time course analysis to determine the time required to desensitize and destabilize the BCR. As shown in Figure 2A, at time points earlier than 30min the tyrosine phosphorylation induced by the desensitizing antigen (25%receptor occupancy) had not decayed sufficiently to allow assessment of whether the receptors could respond to challenge (compare lane 4 to lane 2). However, by 30 min the basal tyrosine phosphorylation had declined significantly to see an antigen-induced response, yet these cells failed to respond to subsequent receptor engagement (100% receptor occupancy), reflecting the desensitization of the BCR at this time point.

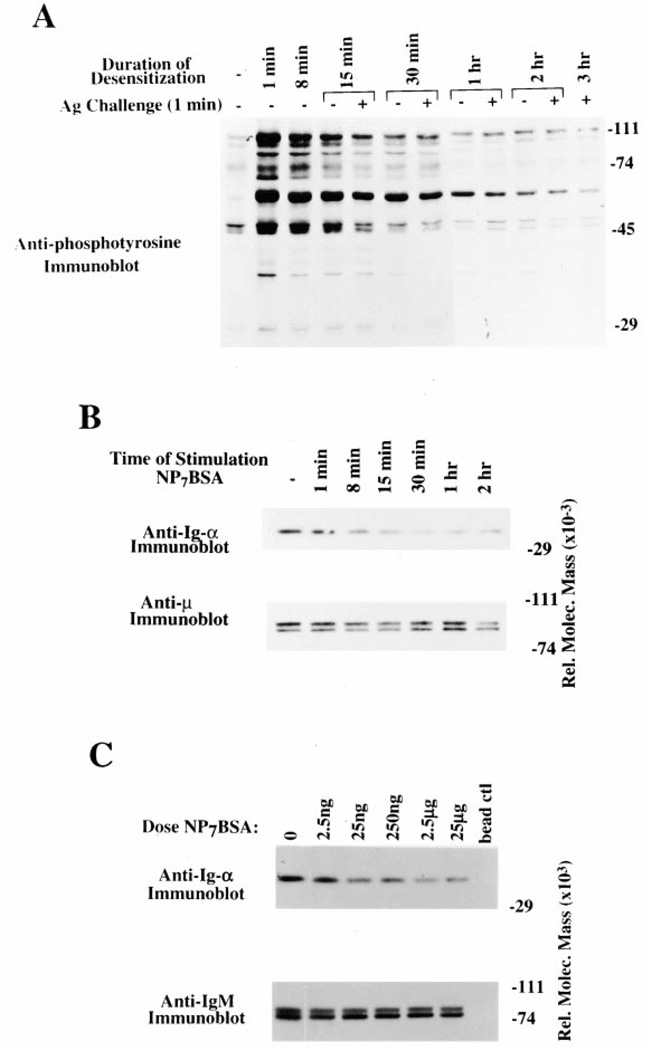

Figure 2. Time Course and Dose Response of BCR Desensitization and Destabilization.

(A) Anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblot of K46µ cells that were desensitized with a low dose of NP7BSA (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml) for 15 min (lane 5), 30 min (lane 7), 1 hr (lane 9), 2 hr (lane 11), and 3 hr (lane 12), and then challenged with high-dose NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml) for 1 min. Alternatively, control cells were stimulated with the desensitizing dose of NP7BSA (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml) for 1 min (lane 2), 8 min (lane 3), 15 min (lane 5), 30 min (lane 6), 1 hr (lane 8), and 2 hr (lane 10) to establish the baseline tyrosine phosphorylation prior to challenge.

(B) Anti-Ig-α and anti-µ immunoblots of anti-µ immunoprecipitates from unstimulated K46µ cells (lane 1), cells stimulated for 1 min (lane 2), 8 min (lane 3), 15 min (lane 4), 30 min (lane 5), 1 hr (lane 6), and 2 hr (lane 7) with 500 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml NP7BSA.

(C) Anti-Ig-α and anti-µ immunoblots of anti-µ immunoprecipitates from unstimulated K46µ cells (lane 1), cells stimulated for 1 hr with 2.5 ng/5 × 106/ml (lane 2), 25 ng/5 × 106/ml (lane 3), 250 ng/5 × 106/ml (lane 4), 2.5 µg/5 × 106/ml (lane 5), 25 µg/5 × 106/ml (lane 6), or lysates immunoprecipitated with blocked agarose beads (lane 7).

To determine the time required for destabilization of the BCR complex, we again performed a time course analysis. As shown in the top panel of Figure 2B, cells stimulated for 15 min exhibited a 50%loss of coprecipi-table Ig-α and at 30 min an 80% diminution. This did not reflect loss of detergent soluble cell surface receptor as the level of precipitable IgM remained relatively constant over the duration of the time course (Figure 2B, bottom panel).

To determine if destabilization of the BCR occurred in a dose-dependent fashion, we treated cells with increasing doses of NP7BSA. As shown in Figure 2C, a nondesensitizing nonsignal-inducing antigen dose (2.5 ng/5 × 106/ml) (Vilen et al., 1997) did not induce significant BCR destabilization. However, higher doses of antigen (25 ng–25 µg) induced similar levels of receptor destabilization. These data show that BCR destabilization is dose dependent, requiring only a low dose of antigen, and increasing antigen dose does not increase the level of receptor destabilization. In addition, both the timing and dose requirements of BCR destabilization appear coincident with receptor desensitization.

IgM- and IgD-Containing BCR Are Destabilized following Antigen Stimulation

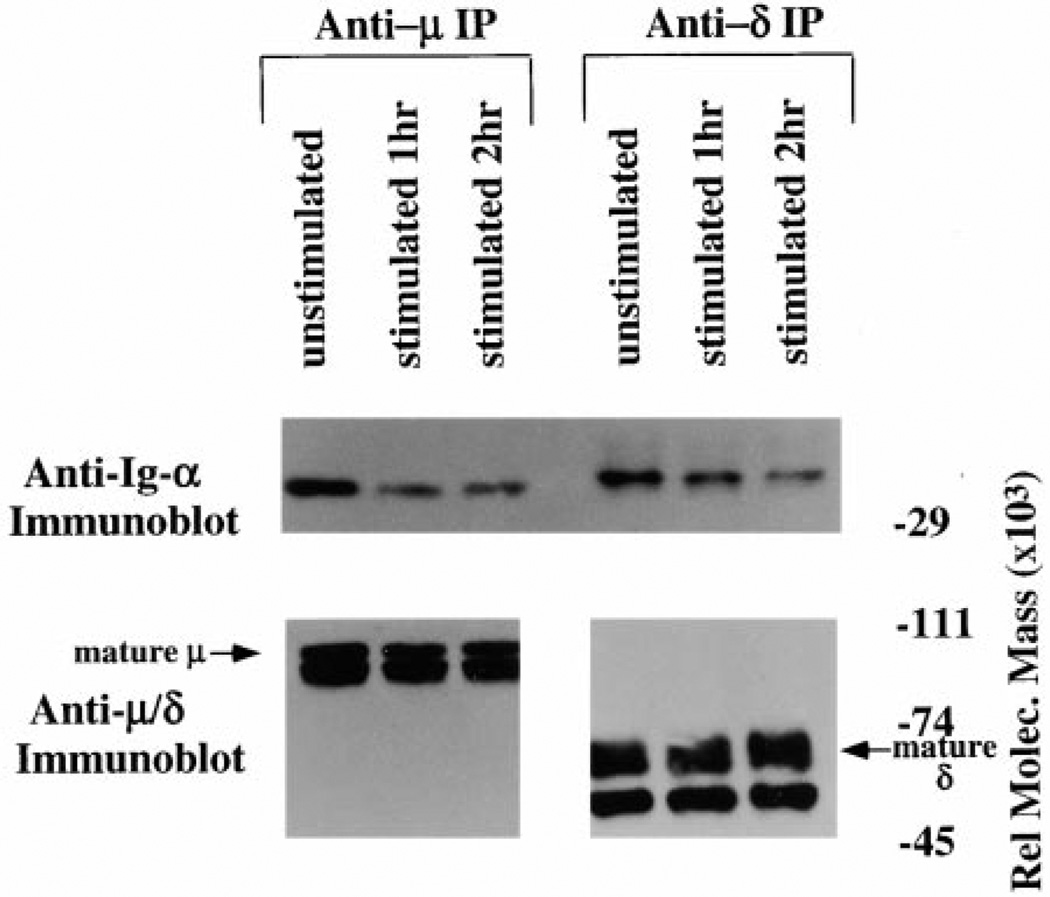

To address whether the destabilization of BCR occurs in both IgM- and IgD-containing receptors, resting splenic B cells from 3–83µδ transgenic mice were desensitized with antigen as previously described (Vilen et al., 1997). Serial immunoprecipitation with anti-µ and then anti-δ, followed by Ig-α immunoblotting, revealed that BCR containing both isotypes were destabilized following exposure to antigen for 1 (Figure 3A, lanes 2 and 5) or 2 hr (lanes 3 and 6). Again, this was not due to unequal immunoprecipitation of membrane immunoglobulin. These data demonstrate that antigen induces destabilization of the BCR complex in B lymphocytes and shows that both µ-and δ-containing receptors are subject to this effect.

Figure 3. mIg-Ig-α/Ig-β Destabilization Occurs in Both IgM- and IgD-Containing Receptors.

Anti-Ig-α, anti-µ, or anti-δ immunoblots of anti-µ or anti-δ immuno-precipitates. IgM and IgD receptors from 3–83µδ transgenic B cells were immunoprecipitated from unstimulated cells (lane 1 and lane 4), cells stimulated for 1 hr with 2 µg/3–83ag150Dex/5 × 106/ml (lane 2 and lane 5), or cells stimulated for 2 hr with 2 µg/3–83ag150Dex/ 5 × 106/ml (lanes 3 and 6).

BCR Destabilization Requires Receptor Aggregation and Protein-Tyrosine Kinase Activation

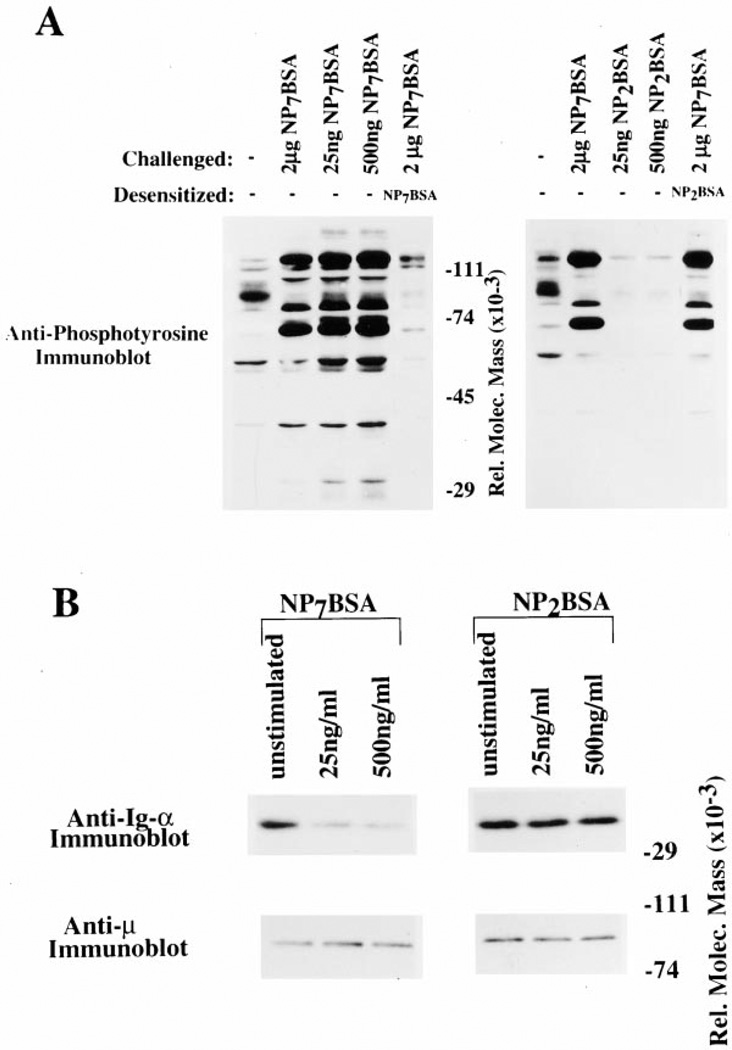

To further define the relationship between BCR destabilization and receptor desensitization, we tested whether low-valency antigen is capable of mediating these effects. As shown in Figure 4A, high- (NP7BSA) but not low (NP2BSA)-valency antigens induced receptor desensitization (lane 5 compared to lane 2 of each panel). As shown in Figure 4B, upper left, NP7BSA induced dissociation of Ig-α/Ig-β from mIgM at an antigen dose that induced receptor desensitization (25 ng/ml) and at a higher antigen dose (500 ng/ml). In contrast, NP2BSA did not induce tyrosine phosphorylation or receptor desensitization (Figure 4A) and was unable to induce BCR destabilization (Figure 4B, upper right). These results show that only antigens of sufficiently high valence to induce receptor desensitization also induce BCR destabilization.

Figure 4. Low Valency Antigens Do Not Induce Receptor Desensitization or BCR Destabilization.

(A) Anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblot of K46µ cells desensitized with NP7BSA (left panel, lane 5) or NP2BSA (right, lane 5). Unstimulated cells (lane 1 of each panel), cells stimulated with challenge dose of NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml; lane 2 of each panel), cells stimulated with desensitizing dose (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml; lane 3 left panel: NP7BSA, lane 3 right panel: NP2BSA), cells stimulated with 500 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml; lane 4 left panel: NP7BSA, lane 4 right panel: NP2BSA), and cells desensitized with 25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ ml NP7BSA for 2 hr and then challenged with 2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml NP7BSA (lane 5 of each panel).

(B) Anti Ig-α and anti-µ immunoblots of IgM immunoprecipitates from unstimulated cells (lane 1 of each panel) and cells stimulated with two doses of either NP7BSA or NP2BSA; 25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml (lane 2 of each panel), 500 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml (lane 3 of each panel).

Inhibition of Receptor-Mediated Syk and Lyn Activation Prevent BCR Destabilization

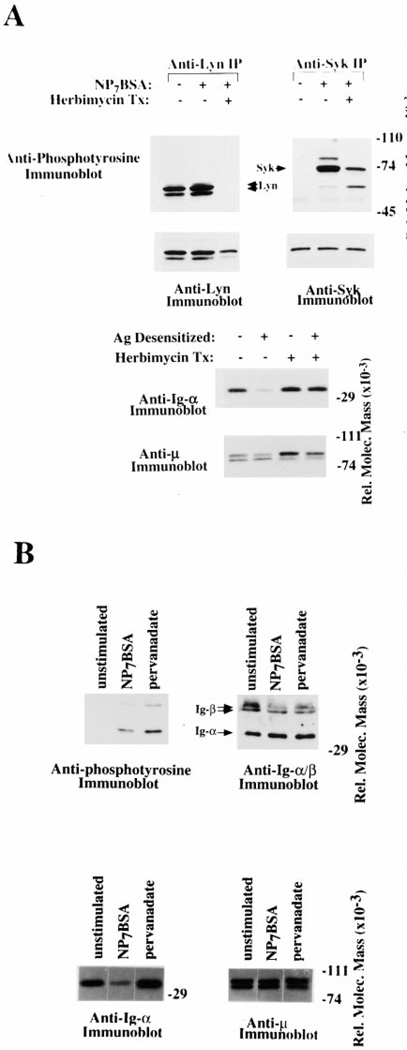

The above data suggest that receptor aggregation and/or activation of a specific protein tyrosine kinase cascade is responsible for the BCR destabilization. To address whether signal transduction is required for receptor destabilization, we inhibited the activation of protein tyrosine kinases, Lyn and Syk, with the pharmacological agent, herbimycin. As shown in Figure 5A, upper panels, antigen stimulation of cells in the absence of herbimycin led to tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk and Lyn (lanes 1 and 2 of each panel), while herbimycin treatment completely inhibited Lyn tyrosine phosphorylation (left panel, compare lane 2 to lane 3) and partially inhibited Syk phosphorylation (right panel, compare lane 2 to lane 3). To test the ability of antigen to induce BCR destabilization in the absence of Lyn activation, we analyzed immunoprecipitated BCR complexes from cells that had been herbimycin treated prior to antigen stimulation. The data in Figure 5A, lower panel, show that antigen does not induce receptor destabilization in herbimycin-treated cells. These results indicate that dissociation of Ig-α/Ig-β from mIg requires protein tyrosine kinase activation.

Figure 5. BCR Destabilization Requires Tyrosine Kinase Activation but Is Not Induced by Phosphate Inhibitors.

(A) Inhibition of Protein Tyrosine Kinases Prevents BCR Destabilization. (Upper panels) Anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblots of anti-Lyn (left panel) or anti-Syk (right panel) immunoprecipitates. K46µ cells were either untreated (lanes 1 and 2 of each panel) or herbimycin treated (lane 3 of each panel) and then stimulated with NP7BSA (500 memng/5 × 106 cells/ml) to assess BCR sensitivity. The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with anti-Lyn and anti-Syk, respectively, immuto assess protein levels.

(Lower panels) Anti-Ig-α and anti-µ immunoblots of IgM immuno-precipitates from unstimulated cells (lane 1), cells stimulated with antigen for 2 hr (lane 2), cells that were herbimycin treated but unstimulated (lane 3), and cells that were herbimycin treated and antigen stimulated for 2 hr (lane 4). The levels of µ-heavy chain from each immunoprecipitate are shown in the anti-µ immunoblot.

(B) Dissociation of the mIg from Ig-α/Ig-β requires a specific signal through the BCR. (Upper left panel) Anti-phosphotyrosine immunoblot of anti-Ig-α immunoprecipitation. Unstimulated cells (lane 1), cells treated with NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml) (lane 2), and cells treated with pervanadate (lane 3). (Upper right panel) The membrane was stripped then sequentially blotted for Ig-α and Ig-β. (Lower panel) Anti-Ig-α (left panel) and anti-µ (right panel) immunoblots of IgM immunoprecipitates. Unstimulated cells (lane 1), NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml) stimulated cells (lane 2), and pervanadate treated cells (lane 3).

BCR Destabilization Requires a Specific Signal through the BCR

To assess whether tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins was sufficient to induce uncoupling, cells were treated with pervanadate to induce tyrosine phosphorylation by inhibition of phosphatases. To assess the ability of pervanadate to induce phosphorylation of effectors involved in BCR signal transduction, we immunoprecipitated Ig-α/Ig-β to assess their phosphorylation state following pervanadate treatment. As shown in Figure 5B, upper panels, pervanadate treatment induced phosphorylation of Ig-α and Ig-β at levels comparable to antigen-treated cells. To determine if this alone was sufficient to induce uncoupling, we analyzed the amount of Ig-α/Ig-β in anti-µ immunoprecipitates. As shown in Figure 5B, lower panels, pervanadate-induced tyrosine phosphorylation did not result in destabilization of the BCR complex (lanes 2 and 3 compared to lane 1). We cannot rule out, however, that pervanadate treatment may not induce the same pattern of tyrosyl phosphorylation as antigen and therefore may be unable to promote receptor destabilization. These data show that the pervanadate-induced phosphorylation of Ig-α and Ig-β is not a sufficient “signal” to propagate destabilization of the BCR.

Antigen-Induced BCR Destabilization Occurs on the Cell Surface

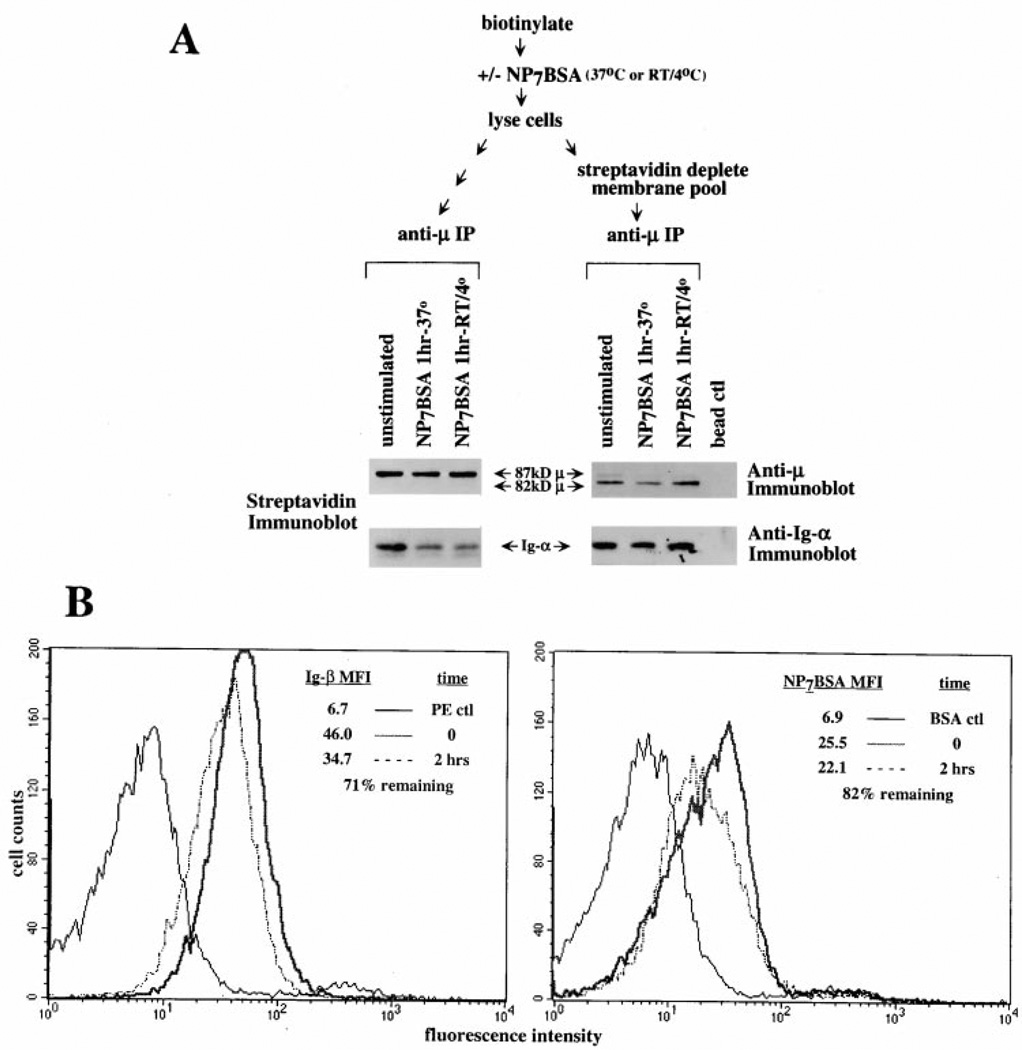

To ascertain whether receptor destabilization occurs on the cell surface, we utilized cell surface biotinylation to track the cell surface receptor pool. Cells were surface biotinylated and then stimulated with antigen to induce BCR destabilization (see schematic Figure 6A). Streptavidin immunoblotting of receptor immunoprecipitates revealed that indeed only the fully glycosylated (87 kDa) pool of µ-chain was biotinylated and that the level of receptors did not significantly decrease following antigen stimulation (1 hr) regardless of the temperature of incubation (Figure 6A, lanes 1–3). Most importantly, the levels of coprecipitated, biotin-tagged Ig-α decreased markedly following antigen stimulation indicating that the cell surface pool of BCR became destabilized. To assess whether the cytoplasmic receptor pool was also destabilized, we depleted the biotinylated surface pool by streptavidin immunoprecipitation and then immunoprecipitated remaining receptors with anti-µ (see schematic Figure 6A). Results show that only the partially glycosylated, 82 kDa cytoplasmic form of µ remained following streptavidin depletion and, furthermore, the amount of coprecipitated Ig-α did not change following antigen stimulation (Figure 6A, lanes 4–6). These data confirm that only the membrane pool of BCR was destabilized following receptor engagement.

Figure 6. BCR Destabilization Occurs on the Cell Surface.

(A) Only the membrane pool of BCRs are destabilized following antigen ligation. (upper) schematic representation of the experimental design. (lower left) streptavidin immunoblot of an anti-µ immunoprecipitate from biotinylated cells. Unstimulated cells (lane 1), 37°C stimulated cells (500 ng/5 × 106/ml; lane 2), and RT/4°C stimulated cells (500 ng/5 × 106/ml; 15 min at RT then 45 min at 4°C; lane 3). (lower right) anti-µ or anti-Ig-α immunoblot of biotin-depleted receptors. Unstimulated cells (lane 1), 37°C stimulated cells (500 ng/5 × 106/ml; lane 2), and RT/4°C stimulated cells (500 ng/5 × 106/ml; 15 min at RT then 45 min at 4°C; lane 3). (B) Desensitized cells maintain surface Ig-β and antigen binding BCR. Surface staining with anti-Ig-β (left panel) or NP7BSA (right panel) of antigen-desensitized cells. The solid black line represents staining of naive cells treated with phycoerythrin-streptavidin (left panel) or biotinylated BSA (right panel). The heavy line of each panel represents naive cells stained 10 min on ice with either Ig-β (left panel) or the challenge dose of NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml; right panel). The dotted line represents Ig-β staining (left panel) or NP7BSA staining (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml; right panel) of cells desensitized for 2 hr with NP7BSA (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml). Median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each population is indicated in the upper right of each panel.

To address whether the destabilized BCR components remained on the cell surface, we measured the levels of surface Ig-β and the antigen binding receptors by flow cytometric analysis. As shown in Figure 6B, antigen-treated cells retained approximately 71% of their surface Ig-β and 82% of antigen binding capability compared to untreated cells. Considered in view of the 80% reduction in mIg-αssociated-Ig-α/Ig-β, this indicates that destabilization of the BCR components must occur on the cell surface.

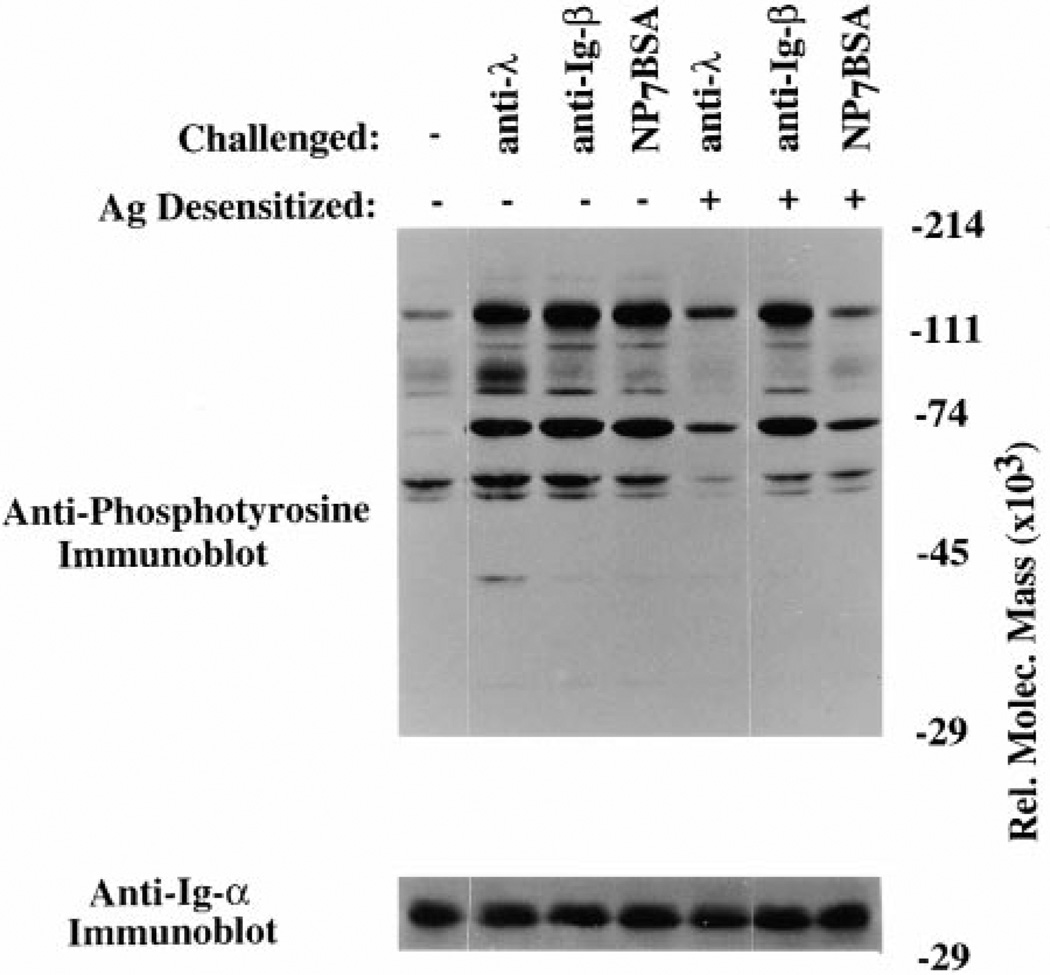

The Ig-α/Ig-β Dimers Remain Competent to Transduce Signals in Antigen-Desensitized Cells

Our previous findings showed that although neither receptors nor Lyn is tyrosine phosphorylated following challenge of desensitized cells, receptor-associated Lyn isolated from these cells can be activated by binding to doubly phosphorylated ITAM peptides (Vilen et al., 1997). This suggests that the effector molecules involved in BCR signaling are functional in desensitized cells but that an early step in receptor activation is defective. Taken together, findings suggest that desensitization reflects failed transduction of signals from mIg to Ig-α/Ig-β and hence to downstream effectors. If this is the case, Ig-α/Ig-β dimers on the surface of desensitized cells should remain competent to transduce signals. To test whether these Ig-α/Ig-β subunits remained competent to signal when aggregated, we determined whether the monoclonal anti-Ig-β antibody HM79 induces signal transduction in antigen-desensitized cells. As shown in Figure 7, K46µ cells desensitized with antigen remained responsive to anti-β challenge (lane 3 compared to lane 6) but were unresponsive to a high dose of antigen challenge (lane 4 compared to lane 7) or to anti-λ challenge (lane 2 compared to lane 5). These differences in tyrosine phosphorylation were not due to different amounts of protein whole cell lysate as evidenced by the Ig-α immunoblot. It is important to note that under the conditions used, cells retained cell surface levels of antigen binding mIg and Ig-β comparable to untreated cells. This result shows that although desensitized cells have destabilized surface BCR, the Ig-α/Ig-β signal-transducing subunits remained competent to signal. These results suggest that destabilization of the BCR complex may at least in part be responsible for the unresponsive state of desensitized receptors.

Figure 7. Desensitized Cells Remain Competent to Signal through Ig-β.

(Upper panel) Antiphosphotyrosine immunoblot of naive K46µ cells (lanes 1–4) or K46µ cells desensitized for 2 hr with NP7BSA (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml; lanes 5–7) that were challenged with either anti-λ (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml; lanes 2 and 5), anti-Ig-β (1 µg/5 × 106 excells/ 0.1 ml; lanes 3 and 6), or high dose of NP7BSA (2 µg/5 × 106 cells/0.1 ml; lanes 4 and 7). (Lower panel) Membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-Ig-α to reveal loading differences.

Discussion

The data presented show that receptor aggregation induces both desensitization and physical destabilization of the B cell antigen receptor. Destabilization was characterized by decreased association of Ig-α/Ig-β dimers with mIg. Both BCR destabilization and receptor desensitization occur within 15–30 min following receptor ligation and both require receptor aggregation and protein tyrosine kinase activation. The signal to destabilize the BCR is receptor specific, as enhancement of protein tyrosine phosphorylation by inhibition of phosphatases does not induce this event despite inducing quantitatively similar levels of effector phosphorylation compared to antigen. Furthermore, antigen-desensitized cells remain competent to signal through the transducer sub-unit(s), suggesting that desensitization is caused by failure to transmit signals to the Ig-α/Ig-β transducer complex following antigen binding to mIgM. These data suggest that receptor destabilization plays a role in mediating the unresponsiveness of antigen-desensitized and perhaps anergic B cells.

Physical dissociation of receptor/transducer complexes has been previously described in T cells. The T cell receptor-CD3 complex (TCR-CD3) is composed of IgTCR-α/β or γ/δ and the associated CD3 complex, composed of γ, δ, and ε, and dimers of the TCR-ζ family proteins (ζ and η). In response to anti-CD3 ligation, the TCR-α/β is modulated from the cell surface with no effect on surface expression of the CD3ε complex (Kishimoto et al., 1995). Similarly, CD3ζ was shown to exhibit a half-life distinct from that of the rest of the TCR subunits (Ono et al., 1995). These results reveal a physical dissociation of the TCR complex following receptor ligation and clearly demonstrate that components of multisubunit antigen receptors are capable of physiologic dissociation.

The data are consistent with previous studies showing that in receptor-desensitized cells downstream kinases can be activated pharmacologically and that the defect maintaining desensitized cells in the unresponsive state lies at the level of the receptor (Vilen et al., 1997). The data presented here show that stimulation of desensitized cells with anti-Ig-β results in signal transduction, suggesting that the unresponsiveness of desensitized receptors reflects failure to transmit signals from mIg to Ig-α/Ig-β dimers. It should be noted that we cannot exclude the possibility that another pool of surface Ig-TCR-α/b, that are not desensitized in trans by BCR ligation, contribute to signal transduction through Ig-β.

It is not clear whether all cell surface BCR are actually destabilized, and thus desensitized, or whether that proportion of mIg that continue to coprecipitate with Ig-α/Ig-β remain signal competent. If the latter is true, data suggest that when diluted in an excess (60%–80%) of destabilized receptors, these “competent” BCR cannot achieve the signal threshold. Although it remains to be formally proven that the density of the competent receptors on desensitized cells is sufficiently low to prevent renewed receptor aggregation and signaling, studies in T cells suggest that the absolute receptor number is critical in defining sensitivity to antigen. Reducing the T cell receptor surface density as little as 35% resulted in a disproportionate increase in the amount of antigen required to reach the activation threshold (Viola and Lanzavecchia, 1996). Measuring the effect of changes in the surface TCR density was achieved by ligand binding and subsequent receptor downmodulation, a process that required several days. In the BCR destabilization model, such a consequence can be achieved within 15–30 min, prior to receptor downmodulation. This early poststimulation effect provides a mechanism of rapidly reducing the numbers of functional BCR by inactivating most receptors by destabilization of the receptor complex.

The in vitro model of receptor desensitization used in this study is based on reports of desensitization of surface receptors with a dose of antigen that was titrated to give maximum Ca2+ mobilization and maximum inductive tyrosine phosphorylation. An antigen dose of 25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml occupies only 25% of the total cell surface receptors, allowing challenge of these cells by antigen ligation of the remaining receptors. Because the affinity of NP for this receptor is moderate (KD = 1.5 × 10−6), we do not know whether the unbound receptors have been bound by antigen that then dissociated. However, staining cells with biotinylated antigen following desensitization revealed that although they remained unresponsive, 70% of the original cell surface receptors remain competent to bind antigen upon challenge (Vilen et al., 1997). Therefore, the dependence of desensitization on receptor occupancy has been difficult to assess. The most direct interpretation of the data in Figures 2C and 4 suggest that the destabilization of the BCR requires ligation of only a small proportion of receptors, as a dose of antigen known to occupy 25% of receptors induces desensitization and destabilization. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that at low antigen doses, serial engagement of all receptors is necessary for the destabilization and desensitization described. Attempts to eliminate the serial receptor engagement caveat using higher affinity receptor/antigen systems (such as the anti-HEL transgenic mouse) have been in-conclusive due to rapid movement of receptor to the detergent insoluble fraction following aggregation (Figure 1, panel 4).

The failure to rapidly downmodulate receptors following antigen binding in both the K46µ lymphoma and the 3–83µδ splenic B cells (Figures 1 and 3) is consistent with our ability to immunoprecipitate equal amounts of mIgM from unstimulated and stimulated cells but is seemingly in contrast to previous observations that anti-receptor antibody ligation stimulates capping and endocytosis of receptors (Braun et al., 1982; Woda and McFadden, 1983; Woda and Woodin, 1984; Goroff et al., 1986; Albrecht and Noelle, 1988). Data described here indicate that this different behavior results from different affinity of antigen for its receptor. Earlier studies addressing attachment of mIgM to cytoskeletal consistently used antireceptor antibodies of high affinity. In our studies, movement of antigen-bound receptors to the detergent insoluble fraction, coincident with loss from the cell surface, was seen only after prolonged periods of moderate-affinity antigen binding (>3 hr) but rapidly following high-affinity antireceptor antibody binding to BCR (B. J. V. and J. C. C., unpublished data; Figure 1, panel 4). Affinity dependence of the response may explain the apparent inconsistency between our data and that published by Jugloff and Jongstra-Bilen (1997) that showed ligand-induced Ig-α translocation to the membrane skeleton as part of the BCR complex. It is unclear if the rate at which receptors move into membrane rafts is also a function of ligand affinity. It is noteworthy that studies to date have employed only high-affinity interactions (anti-TCR and DNP-IgE/FcεR1) to demonstrate ligand-induced receptor movement to rafts or detergent-resistant membrane domains (Field et al., 1997; Xavier et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 1998). Clearly, moderate-affinity antigens (NP-KD = 1.5 × 10−6 and 3–83 ag150Dex-KD = approximately 10−5 to 10−6) represent a situation more pertinent to the interaction of B cells with antigen during the primary immune response.

The mechanism of Ig-α/Ig-β dissociation from mIg remains undefined. Previous studies have shown that the association of Ig-α/Ig-β with mIg involves interactions between the transmembrane domain and extracellular spacer of mIg with undefined regions of Ig-α/Ig-β. Two polar regions have been identified within the transmembrane region of mIg that mediate retention of mIg in the endoplasmic reticulum in the absence of Ig-α/Ig-β association and stabilize the interaction with Ig-α/Ig-β (reviewed in Campbell et al., 1994; Pao et al., 1997). The rapidity of the induced destabilization of the BCR complex indicates that a posttranslational event must mediate the separation of the transducer subunits from mIg (Figure 2B). In addition, our finding that protein tyrosine kinase activation is required for receptor destabilization indicate that activation of a specific kinase lymphomay facilitate the event (Figures 4 and 5A). Mechanistically, this could involve modification of Ig-α/Ig-β or residues within the transmembrane domain of mIg. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that modification of some other cell surface molecule mediates receptor destabilization. It is unlikely that the operative modification involves tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor since no quantitative differences have been seen in antiphosphotyrosine immunoblots of BCR components following receptor desensitization (B. J. V. and J. C. C., unpublished data).

BCR destabilization may have important physiological functions in promoting a refractory period during T cell-B cell interactions and in maintaining the unresponsiveness of tolerant B cells. The binding of both self and foreign antigen to the BCR transmits an indistinguishable “first” signal, which by raising CD86 and MHC class II expression primes the B cell for a productive interaction with Th cells. Whether the B cell becomes anergic or, alternatively, undergoes proliferation and differentiation is dependent on a “second” signal from an antigen-specific Th cell. One function of BCR destabilization may be to provide a refractory period while the B cell upregulates costimulatory molecules required for appropriate T cell interaction. This increased expression is transient, lasting 18–48 hr forCD86 and MHC class II, and, interestingly, CD86 cannot be upregulated again by restimulation of anergic cells with antigen (Ho et al., 1994). This refractory period gives the cell a single opportunity to receive a second signal, thereby providing a checkpoint that may ensure that autoreactive clones are not expanded. Thus, cells that were stimulated by antigen (signal 1) but fail to receive T cell help (signal 2) remain unresponsive and are destined to die (Hartley et al., 1993). Thus, a second function of BCR destabilization may be to maintain autoreactive cells in an unresponsive state. Whether BCR destabilization is responsible for the long term unresponsiveness associated with anergy is unclear; however, such a mechanism would be consistent with the reported continuous need for antigen to maintain anergy (Goodnow et al., 1991; B. J. V. and J. C. C., unpublished data). The continuous presence of antigen may be required to destabilize newly synthesized receptors.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Isolation and Stimulation

The K46µ lymphoma cells, expressing mIgM specific for NP, were cultured as previously described (Kim et al., 1979; Reth et al., 1987; Hombach et al., 1990; Vilen et al., 1997). Cells were stimulated with doses of NP7BSA ranging from 25–500 ng/5 × 106/ml for 1–2 hr at 37°C. Under conditions of desensitization (25 ng/5 × 106/ml = 25% receptor occupancy), the majority of receptors remained available to bind the challenge dose of antigen (2 µg/5 × 106/0.1 ml NP7BSA) as previously characterized (Vilen et al., 1997). Alternatively, cells were stimulated with biotinylated anti-µ (b-7–6) at 10 µg/5 × 106/ml. To avidin immunoprecipitate unstimulated cells (Figure 1, lane 7), biotinylated b-7–6 was bound for 2 min at 4°C prior to cell lysis. For surface biotinylation experiments, cells were either stimulated at 37°C for 1 hr or at room temperature for 15 min followed by 4°C for 45 min to slow cell surface receptor loss.

Resting (ρ >1.066 or 1.070) B lymphocytes were isolated from spleens of 3–83µδ Ig transgenic mice (on B10.D2 background) as previously described (Cambier et al., 1988; Russell et al., 1991). These transgenic mice contain normal levels of splenic B lympho-cytes compared to non-transgenic B10.D2 mice. Resting 3–83 B cells express both IgM and IgD receptors specific for H-2Kk and respond to receptor crosslinking by Ca2+ mobilization and tyrosyl phosphorylation comparably to B10.D2-derived B cells. Stimulation of the 3–83µδ B lymphocytes was performed using an antigen mimetic peptide-dextran conjugate (3–83ag150Dex) at a dose of 2 µg/5 × 106/ml (Vilen et al., 1997). The Ag-mimetic sequence CAHDWRS GFGGFQHLCCGAAGA was defined by screening a phage display library using the 3–83 immunoglobulin (Sparks et al., 1995). The binding of the mimetic peptide to the 3–83 immunoglobulin was shown to be specific for the antigen combining site based on an ELISA assay using isotype matched immunoglobulin. In addition, an anti-idiotypic antibody specific for the 3–83 receptor (54.1) competed for peptide binding (Carbone and J. C. C., unpublished data).

Pervanadate Stimulation and Herbimycin Treatment

Cells were stimulated for 10 min at a final concentration of 30 µM sodium orthovanadate using freshly prepared solution of 10 µM sodium orthovanadate/30 µM hydrogen peroxide. Alternately, cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) were treated with 5 µM herbimycin (Calbiochem, LaJolla, CA) for 16 hr prior to desensitization.

Antibodies and Immunoprecipitation

The monoclonal antibodies b-7-6 (anti-µ), HM79 (anti-Ig-β), and L22.12.4 (anti-λ) were purified from culture supernatants (Koyama et al., 1997). The HB-δ6 (anti-δ) used for immunoprecipitation and the polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgD for immunoblotting were provided by Fred Finkleman. The rabbit polyclonal anti-Ig-α and anti- Ig-β were prepared against the cytoplasmic tails of the molecules (residues 160–220 of mouse Ig-α and residues 181–246 of mouse Ig-β). The rabbit polyclonal anti-Lyn and anti-Syk have been previously described (Vilen et al., 1997). Other primary antibodies for Western blotting include goat anti-µouse IgM-HRP (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and the anti-phos-photyrosine antibody Ab-2 (Oncogene Science, Manhasset, NY). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies include rat anti-µouse IgG1 (Biosource Intl., Camarillo, CA), protein A (Zymed, S. San Francisco, CA), rabbit anti-goat Ig (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and streptavidin (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Cell lysates from 15–25 × 106 cells were prepared in buffer containing 0.33% CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mM sodium o-vanadate, 1 mM PMSF, 0.4 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mg/ml each of aprotinin, leupeptin, and α1-antitrypsin. Lysates were held on ice for 10 min and then particulate material was removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. Antibodies used in immunoprecipitations were conjugated to CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B according to manufacturer’s instruction (Pharmacia Bio-tech, Uppsala, Sweden). The streptavidin immunoprecipitations were performed using streptavidin agarose (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Approximately 0.5–1 µg of precipitating antibody was incubated with 1 × 106 cell equivalents of cleared lysate for 30 min at 4°. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice with lysis buffer and then fractionated using 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Fractionated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using a semidry blotting apparatus following the conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA). Immunoreactive proteins were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence detection (ECL, NEN, Boston, MA).

Surface Biotinylation

Cells were washed three times with PBS and then resuspended at 10 × 106/ml in PBS containing 50 µg/ml sulfo-NHS-biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL). After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS containing 15 mM glycine, resuspended at 5 × 106/ml in IMDM containing 2% FCS, and then stimulated as described above.

Surface Staining

K46µ cells were untreated or treated with non-biotinylated NP7BSA for 2 hr at 37°C (25 ng/5 × 106 cells/ml) and then stained at 4°C in the presence of 0.2% azide with biotinylated anti-Ig-β (HM79) or biotinylated NP7BSA to determine the presence of surface Ig-β and antigen binding receptors, respectively. The samples were washed antiextensively with cold staining medium (balanced salt solution containing 2%calf serum and 0.2%azide) followed by secondary staining with phycoerythrin-conjugated avidin for 20 min. Analysis was performed on FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Joe Dal Porto for helpful discussion and critical reading of this manuscript and Kathy Burke for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by U. S. Public Health Service Grant AG13983. J. C. C. is an Ida and Cecil Green Professor of Cell Biology. B. J. V. is a Fellow of the Leukemia Society of America.

References

- Albrecht DL, Noelle RJ. Membrane Ig-cytoskeletal interactions. I. Flow cytofluorometric and biochemical analysis of membrane IgM-cytoskeletal interactions. J. Immunol. 1988;141:3915–3922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun J, Hochman PS, Unanue ER. Ligand-induced association of surface immunoglobulin with the detergent-insoluble cytoskeletal matrix of the B lymphocyte. J. Immunol. 1982;128:1198–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunswick M, June CH, Mond JJ. B lymphocyte immunoglobulin receptor desensitization is downstream of tyrosine kinase activation. Cell. Immunol. 1994;156:240–244. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier JC. New nomenclature for the Reth motif (or ARH1/TAM/ARAM/YXXL) Immunol. Today. 1995;16:110. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier J, Chen ZZ, Pasternak J, Ransom J, Sandoval V, Pickles H. Ligand-induced desensitization of B-cell membrane immunoglobulin-mediated Ca2+ mobilization and protein kinase C translocation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6493–6497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambier JC, Fisher CL, Pickles H, Morrison DC. Dual molecular mechanisms mediate ligand-induced membrane Ig desensitization. J. Immunol. 1990;145:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KS, Backstrom BT, Tiefenthaler G, Palmer E. CART: a conserved antigen receptor transmembrane motif. Semin. Immunol. 1994;6:393–410. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke MP, Heath AW, Shokat KM, Zeng Y, Finkelman FD, Linsley PS, Howard M, Goodnow CC. Immunoglobulin signal transduction guides the specificity of B cell-T cell interactions and is blocked in tolerant self-reactive B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:425–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFranco AL. The complexity of signaling pathways activated by the BCR. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:296–308. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson J, Radic MZ, Camper SA, Hardy RR, Carmack C, Weigert M. Expression of anti-DNA immunoglobulin transgenes in non-autoimmune mice. Nature (Lond.) 1991;349:331–334. doi: 10.1038/349331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field KA, Holowka D, Baird B. Compartmentalized activation of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor within membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:4276–4280. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay D, Saunders T, Camper S, Weigert M. Receptor editing: an approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:999–1008. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Adelstein S, Lavoie TB, Smith-Gill SJ, Brink RA, Pritchard-Briscoe H, Wotherspoon JS, Loblay RH, Raphael K, et al. Altered immunoglobulin expression and functional silencing of self-reactive B lymphocytes in transgenic mice. Nature (Lond.) 1988;334:676–682. doi: 10.1038/334676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow CC, Crosbie J, Jorgensen H, Brink RA, Basten A. Induction of self-tolerance in mature peripheral B lymphocytes. Nature (Lond.) 1989;342:385–391. doi: 10.1038/342385a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnow CC, Brink R, Adams E. Breakdown of self-tolerance in anergic B lymphocytes. Nature (Lond.) 1991;352:532–536. doi: 10.1038/352532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goroff DK, Stall A, Mond JJ, Finkelman FD. In vitro and in vivo B lymphocyte-activating properties of monoclonal anti-delta antibodies. I. Determinants of B lymphocyte-activating properties. J. Immunol. 1986;136:2382–2392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley SB, Cooke MP, Fulcher DA, Harris AW, Cory S, Basten A, Goodnow CC. Elimination of self-reactive B lymphocytes proceeds in two stages: arrested development and cell death. Cell. 1993;72:325–335. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz M, Nemazee D. BCR ligation induces receptor editing in IgM+IgD- bone marrow B cells in vitro. Immunity. 1997;6:429–436. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho WY, Cooke MP, Goodnow CC, Davis MM. Resting and anergic B cells are defective in CD28-dependent co-stimulation of naive CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1539–1549. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hombach J, Tsubata T, Leclercq L, Stappert H, Reth M. Molecular components of the B-cell antigen receptor complex of the IgM class. Nature (Lond.) 1990;343:760–762. doi: 10.1038/343760a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Pleiman CM, Pao L, Schneringer J, Hippen K, Cambier JC. Phosphorylated immunoreceptor signaling motifs (ITAMs) exhibit unique abilities to bind and activate Lyn and Syk tyrosine kinases. J. Immunol. 1995;155:4596–4603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jugloff LS, Jongstra-Bilen J. Cross-linking of the IgM receptor induces rapid translocation of IgM-associated Ig alpha, Lyn, and Syk tyrosine kinases to the membrane skeleton. J. Immunol. 1997;159:1096–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C, Merwin RM, Sachs DH, Asofsky R. Establishment and characterization of BALB/c lymphoma lines with B cell properties. J. Immunol. 1979;122:549–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KM, Alber G, Weiser P, Reth M. Signalling function of the B-cell antigen receptors. Immunol. Rev. 1993;132:125–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1993.tb00840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto H, Kubo RT, Yorifuji H, Nakayama T, Asano Y, Tada T. Physical dissociation of the TCR-CD3 complex accompanies receptor ligation. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:1997–2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama M, Ishihara K, Karasuyama H, Cordell JL, Iwamoto A, Nakamura T. CD79 alpha/CD79 beta heterodimers are expressed on pro-B cell surfaces without associated mu heavy chain. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:1767–1772. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T. Molecular mechanisms in B cell antigen receptor signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang J, Jackson M, Teyton L, Brunmark A, Kane K, Nemazee D. B cells are exquisitely sensitive to central tolerance and receptor editing induced by ultralow affinity, membrane-bound antigen. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:1685–1697. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemazee DA, Burki K. Clonal deletion of B lymphocytes in a transgenic mouse bearing anti-MHC class I antibody genes. Nature (Lond.) 1989;337:562–566. doi: 10.1038/337562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Murakami M, Shimizu A, Ozaki S, Tsubata T, Kumagai S, Honjo T. A transgenic model of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J. Exp. Med. 1992;175:71–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Ohno H, Saito T. Rapid turnover of the CD3 zeta chain independent of the TCR-CD3 complex in normal T cells. Immunity. 1995;2:639–644. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao L, Carbone AM, Cambier JC. Antigen receptor structure and signaling in B cells. In: Harnett MM, P RK, editors. Lymphocyte Signalling: Mechanisms, Subversion and Manipulation. Chicester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 1997. pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rathmell JC, Townsend SE, Xu JC, Flavell RA, Goodnow CC. Expansion or elimination of B cells in vivo: dual roles for CD40- and Fas (CD95)-ligands modulated by the B cell antigen receptor. Cell. 1996;87:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reth M, Petrac E, Wiese P, Lobel L, Alt FW. Activation of V kappa gene rearrangement in pre-B cells follows the expression of membrane-bound immunoglobulin heavy chains. EMBO. J. 1987;6:3299–3305. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DM, Dembic Z, Morahan G, Miller JF, Burki K, Nemazee D. Peripheral deletion of self-reactive B cells. Nature (Lond.) 1991;354:308–311. doi: 10.1038/354308a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks AB, Adey NB, Quilliam LA, Thorn JM, Kay BK. Screening phage-displayed random peptide libraries for SH3 ligands. Methods Enzymol. 1995;255:498–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)55052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilen BJ, Famiglietti SJ, Carbone AM, Kay BK, Cambier JC. B cell antigen receptor desensitization: disruption of receptor coupling to tyrosine kinase activation. J. Immunol. 1997;159:231–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola A, Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996;273:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woda BA, McFadden ML. Ligand-induced association of rat lymphocyte membrane proteins with the detergent-insoluble lymphocyte cytoskeletal matrix. J. Immunol. 1983;131:1917–1919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woda BA, Woodin MB. The interaction of lymphocyte membrane proteins with the lymphocyte cytoskeletal matrix. J. Immunol. 1984;133:2767–2772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Membrane compartmentation is required for efficient T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;8:723–732. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT palmitoylation: its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]